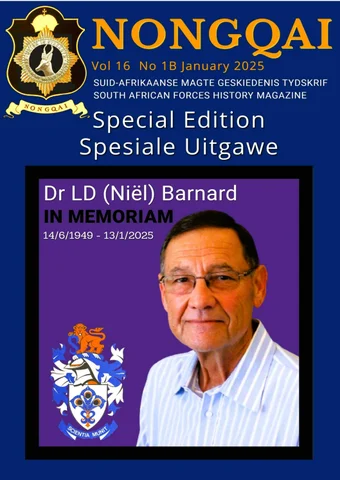

Dr LD Barnard

Dr LD Barnard was die laaste oorblywende direkteur-generaal van die voormalige RSA se veiligheids- en inligtingsgemeenskap. Al die hoofde van die voormalige SA Weermag en kommissarisse van die SA Polisie wat saam met hom op die staatsveiligheidsraad (SVR) gedien het, is nou oorlede. Slegs enkele voormalige adjunk-ministers wat op die SVR gedien het, is nog in die lewe. Maar mens kan sê dat op ‘n departementele vlak, daardie era nou finaal afgesluit word.

Nadat ek kritiek op dr Barnard in die media waargeneem het, het ek dr Willem Steenkamp, wat dr Barnard as lektor en as DG goed geken het, gevra om ‘n eerlike waardering en huldeblyk oor dr Barnard te skryf.

As lid van die sekretariaat van die staatsveiligheidsraad (SSVR) het ek dr Barnard ‘n paar keer ontmoet. Ek het hom opgesom as ‘n Christen met vaste beginsels. Hy het ook ‘n baie sterk persoonlikheid gehad. Hy het aan my erken dat hy nie veel ooghare vir sommige SAP-lede gehad nie! Ek sou nie onnodig met hom swaarde wou kruis nie!

Die redaksie het uit sy pad gegaan om ‘n gebalanseerde beeld van dr Barnard te skep wat die toets van kruisverhoor in enige hof sou deurstaan. Ook het ons geskryf in die konteks van on tyd!

Dr LD Barnard

Dr LD Barnard was the last remaining directorgeneral of the former RSA's security and intelligence community. All the heads of the former SADF and commissioners of the former SAP who served with him on the State Security Council (SSC) are now deceased. Only a few former deputy ministers who served on the SSC are still alive. But one can say that on a departmental level, that era is now finally coming to an end.

After observing criticism of Dr Barnard in the media, I asked Dr Willem Steenkamp, who knew Dr Barnard well as a lecturer and DG, to write an honest appreciation and tribute about Dr Barnard.

As a member of the Secretariat of the State Security Council (SSSC), I met Dr. Barnard a few times. I viewed him as a Christian with firm principles He admitted to me that he didn't like some SAP members! He also had a very strong personality. I would not want to cross swords with him unnecessarily!

The editors went out of their way to create a balanced image of Dr Barnard that would stand the test of cross-examination in any court. We also wrote in the context of our time!

Johan Mostert & Jan-Jan Joubert

Een van die grondleggers van die Suid-Afrikaanse demokrasie en moderne intelligensiedienste, Niël Barnard, is Maandagoggend in die ouderdom van 75 jaar oorlede. Jan-Jan Joubert en Johan Mostert neem bestek op van sy bydrae tot 'n onderhandelde skikking in 1994 in Suid-Afrika.

Foto: Niël Barnard was een van die eerste Westerse intelligensiehoofde wat na die val van die Berlynse Muur in 1989, direkte en uiters geheime skakelverhoudinge met die Komitét Gosudarstvennoy Bezopasnosti (KGB), aangeknoop het. (Foto verskaf)

Dr. Lukas Daniël Barnard was ’n onwaarskynlike held, want hy het graag ’n beeld van stugge konserwatisme en behoudendheid voorgehou. Dit was egter juis hierdie onbuigsaam-eerlike gedrongenheid deur logika en feite wat hom daartoe gebring het om as voorste hervormer die onderhandelings vir ’n vreedsame oorgang na grondwetlike demokrasie te laat begin.

Niël Barnard is op 14 Junie 1949 in Otjiwarongo in die hedendaagse Namibië gebore. Hy het as student aan die Vrystaatse Universiteit in Bloemfontein akademies uitgeblink en het professor geword in Politieke Wetenskap (destyds Staatsleer genoem).

Dis vandaar dat hy gevra is om op die jeugdige ouderdom van 31 jaar Direkteur-Generaal van die Nasionale Intelligensie te word.

By bestekopname van Barnard se bydrae tot en deur die intellignsieraamwerke was daar veral twee aspekte wat opval:

• Sy bydrae in die totstandbrenging van ‘n demokratiese Suid-Afrika en in die verband dien Mandela se inskripsie in die kopie van Long Walk to Freedom wat hy aan Barnard gegee het as ‘n bewysstuk: “Best wishes to one of those patriotic South Africans who strived tirelessly & without publicity to help lay the foundations of the new South Africa”.

• Sy insig en onvermoeide ywer om die Nasionale Intelligensiediens (NI) uit te bou tot ‘n ware nasionale intelligensiediens wat ‘n saakmakende rol gespeel het in kritieke besluitneming op nasionale vlak en internasionaal respek afgedwing het.

Volgens sy eie interpretasie was Barnard sterk konserwatief toe hy by NI aangekom het. Sy siening van die bedreiging wat Suid-Afrika in die gesig gestaar het, het grootliks gestrook met die algemeen gangbare opvatting in owerheidsgeledere. Hy was egter ‘n goeie luisteraar met ‘n oop gemoed.

In NI het hy kennis geneem van ‘n alternatiewe siening wat op daardie stadium nie openlik na buite uitgespreek is nie. Volgens hierdie siening was die kernoorsaak van die aanslag teen Suid-Afrika nie in die eerste plek die werk van kommuniste en kwaadwillige agitators nie, maar was die werklike oorsaak geleë in die beleid van apartheid. Die harde realiteit wat deur NI geskilder is, het hom oortuig dat dit ‘n geldige gevolgtrekking op grond van die feite was.

Dit was egter nie ‘n gewilde vertolking nie. Om hierdie boodskap tuis te bring, moes met groot omsigtigheid te werk gegaan word. NI kon as verraaier gebrandmerk word omdat dit vertolk kon word as kritiek op en selfs dislojaliteit teenoor die regering.

Barnard het egter in die stilligheid voortgegaan om die boodskap oor te dra dat politieke verandering onvermydelik is en dat die ANC reeds as so ‘n groot magsfaktor ontwikkel het, dat dit nie in ‘n toekomstige bedeling geïgnoreer kan word nie. Hy het hierdie boodskap onomwonde, maar diplomaties aan die aanvanklike Eerste Minister en latere President PW Botha persoonlik oorgedra.

Teen daardie stadium was Botha so tevrede met die kwaliteit van NI se intelligensie, dat hy geluister het en NI toegelaat het om kontak te maak met die ANC om meer van die organisasie se standpunte te wete te kom. Barnard was toe reeds vir ‘n geruime tyd in gesprek met Mandela in die gevangenis en een van sy uitdagings was om die delikate balans tussen Mandela en die uitgeweke ANC te handhaaf.

Hy moes aan die een kant poog om ‘n verstandhouding met Mandela te bewerkstellig en aan die ander kant sorg dra dat die uitgeweke ANC Mandela nie as uitverkoper beskou nie. Barnard het twee baie belangrike boeke van hoogstaande gehalte oor hierdie fase van die Suid-Afrikaanse geskiedenis geskryf.

Uitbouing van NI

Barnard het baie bygedra tot die ontwikkeling van NI tot een van die top intelligensiedienste in die wêreld. Hy het NI, soos sommige dit gestel het, op sy kop omgekeer.

Van al die bydraes wat hy gelewer het, is daar een wat uitstaan uitstaan en bepalend was vir NI se sukses: sy bevordering van ‘n etos van uitnemendheid, meriete, harde werk, opoffering en integriteit. Hy het dit nie net verkondig nie, maar ook self die voorbeeld gestel en daarmee die organisasie met hom saamgeneem.

Toe Barnard in 1980 as Direkteur-Generaal diens by NI aanvaar, was die organisasie steeds in ‘n verouderde paradigma vasgevang. Die insameling van inligting (spioenasie) en teenspioenasie het voorrang geniet. Die derde been van intelligensie, naamlik vertolking, was die weeskind.

Dit is een van Barnard se groot verdienstes dat hy vertolking tot sy reg laat kom het. Daardeur is insigte ontwikkel wat hom in staat gestel het om die ware feite van die bedreiging tot op die hoogste vlak onder aandag te bring. Een van die insigte wat deur die navorsers (vertolkers) ontwikkel is, was die volgende:

Om die dringendheid van die veiligheidsituasie te illustreer, het die navorsers ‘n prent van ‘n driebeenpot waaronder ‘n vuurtjie brand met pap wat begin oorkook, aan die Staatsveiligheidsraad vertoon. Die boodskap was, dit gaan nie help om langer pogings aan te wend om met geweld die pot se deksel te probeer vasdruk om te voorkom dat dit oorkook nie. Die vuur is besig om groter te word en daar is nie voldoende vermoë om die deksel styf toe te bly hou sodat die pot nie oorkook nie. Die enigste oplossing is om die vuur te verwyder.

Dit was NI se bydrae om aan die regering te sê, dit gaan nie help om die manifestasie van die aanslag aan te spreek nie, die grondoorsaak moet verwyder word. Van die ministers wat teenwoordig was, het hierdie beeld daarna gereeld opgehaal. Onder Barnard se leiding is die navorsingskomponent uitgebou tot een van die voorste sosiaal-wetenskaplike instellings in die land.

Om die bestuur van die organisasie meer doeltreffend te maak, het Barnard drastiese veranderinge aan die bestuurstyl van die organisasie aangebring. Daarmee het hy verseker dat hy elke dag op hoogte bly van wat in die organisasie gebeur. Wat die bestuurslede in die besonder waardeer het, was sy vermoë om sterk leiding te gee en sy bereidwilligheid om besluite te neem. In die

bestuursvergaderings het navorsers groter as ooit tevore tot hulle reg gekom, wat ook die insamelaars gebaat het.

Hy het ook ‘n aktiewe belangstelling in opleiding in die algemeen gehad en opdrag gegee dat die opleidingsafdeling en die biblioteek drasties uitgebou word. Op sy aandrang is daar ‘n uiters moderne opleidingsfasiliteit buite Pretoria opgerig.

Hoewel hy nie onnodig ingemeng het in die werksaamhede van die hoofdirektorate nie, het hy nogtans sterk oorhoofse leiding en motivering gegee. Hy was aktief in sommige van die inisiatiewe van die insamelaars en het saam met hulle goeie verhoudinge met talle lande opgebou. Ook wat tegniese insameling betref, het hy ‘n sterk ondersteunende rol gespeel.

Nadat die demokratiese bedeling sy beslag gekry het, is Barnard in 1994 aangestel as eerste Direkteur-Generaal van die Wes-Kaap. Hier het hy die streng fokus op korrekte navolging van regulasies en die klem op skoon regering gevestig wat vandag nog die provinsie kenmerk en onderskei – ’n bydrae tot uitnemendheid wat voortleef en waarvoor hy meer erkenning verdien.

Niël Barnard was vertroueling van staatsmanne en spioene, maar hy was eerstens gesinsman –eggenoot vir sy vrou Engela, pa vir hul drie seuns waarvan hy een voortydig moes begrawe, en oupa vir sy vyf kleinkinders. Hy was hartstogtelik lief vir Afrikaans, waarin hy ’n woordkunstenaar was. En as hy jou verby gelaat het by daardie stugge beeld waaragter hy sy ware lewe gelei het, was hy ’n vriend duisend, ’n braaier en wynkenner vir die boeke, ’n sprankelende verteller, emosioneel toegewy aan sy familie, geneig om sy eie foute in te sien en daaroor te lag, ’n raadsman en min kere gelukkiger as wanneer hy voluit kon lostrek teen diegene in die media wat hy as woke beskou het.

Suid-Afrika verloor een van sy groot seuns wat, soos ’n ander wat in Bloemfontein vorming ondervind het, deur die digter gehuldig kan word:

“Maak hom ’n graf op die grond wat sy liefde gewy en geseën het; dis skoon vir ’n held om te rus aan die voete van wie hy beween het.” *

Dr. L.D. (NIËL) BARNARD: AN APPRECIATION (June 14, 1949 – January 13, 2025)

Dr. Willem Steenkamp

(Vir ‘n verkorte Afrikaanse weergawe hiervan, sien asb. die volgende artikel)

1. MUCH HAS BEEN WRITTEN ABOUT NIëL BARNARD – BOTH FOR AND AGAINST...

Tall trees catch the most wind...

The late Dr Niël Barnard was one such tree, due to the position he was placed in at a very young age by PW Botha as DG of the National Intelligence Service (NIS).

It is not surprising that, upon his passing, one would read varied comments – some of which pay tribute to his undeniable contribution to national security and in kicking off the negotiation process. Others, however, still scourged him, mainly ad hominem for his pre-history and aspects of his

personality and style. Those so inclined dismiss his alleged contributions as mere flights of egotistical imagination, or manifestations of an intelligence service that seriously exceeded its mandate.

It is also not surprising that the tributes come from the side of those close to him, especially within the National Intelligence Service. The flogging, on the other hand, came mostly from those who served in other components of the bureaucracy of that period, being often officials who had crossed swords with him in the many inter-agency battles of those years. Or from people from the then left of the political spectrum who felt that their rights had been violated by Barnard and/or the security services.

What value can I hope to add to this polemic, and: why me?

Perhaps Nongqai 's editor asked me to write this appreciation on the logical assumption that – in addition to the conflicting opinions of the deceased's friends and his enemies respectively – a political-scientific analysis of Niël Barnard and his NIS team's impact on the change of course that South Africa experienced in the run-up to the political transformation of the early nineties, may be of value to readers.

An emotionally neutral analysis, written by someone who indeed knew him personally, and who also knows the professional milieu in which he operated (from both the practical and academic side), but who in addition served in other capacities such as ambassador, which allowed for a broader perspective. Someone who was neither an intimate friend of the deceased, nor an ideological or bureaucratic "enemy" of his...

I knew Niël Barnard well, both as a Political Science lecturer and as DG of the NIS. Stretching from our Kovsie days in Bloemfontein during the early seventies, when he was my junior lecturer in Political Science. Through his appointment as DG of NIS and his first handful of years as head of the service. (Thus, after I had been a student of his, I had joined the Bureau for State Security and stayed on through its changing iterations of the (short-lived) Department of National Security and subsequently, the NIS – all in order to complete my compulsory national service and Public Service Commission bursary obligations. In the NIS, I held positions (as I will show) where I could observe Barnard first hand.

Upon completing my aforementioned obligations I said goodbye to the NIS, to subsequently obtain admission as a lawyer, and then joined the diplomatic service. This winding path has given me the

advantage of now being able to look back on Barnard’s contributions from the necessary distance, and from different career angles.

Academically speaking, my doctorate in Political Science with its specific focus on the role and function of intelligence within the political system, as well as my (parallel) training as lawyer, equip and oblige me to assess the extent to which the actions that the NIS in the end chose to execute (and which undoubtedly impacted political decision-making) can normatively be seen as having been within the scope of its statutory mandate, and functionally appropriate for an intelligence service to have chosen to embark upon

My broader institutional experience and thus wider perspective came first from my family connection to the Security Branch of the Police (my father at one stage headed it). As mentioned, also my own later life as a diplomat (which included being head of the diplomatic academy, and then the New South Africa's first ambassador to once-hostile Black Africa). Thus, I can assess Barnard and his NIS team's contribution during the critical late eighties and early nineties without having been limited to just one institution's silo vision.

Furthermore, since I became co-editor of Nongqai, the South African Forces history magazine, much unpublished information about once-hidden decisions and shenanigans have come to my eyes and ears, first-hand from reliable eyewitnesses. This has also contributed greatly to providing perspective and understanding regarding the whys and wherefores of what really happened during those turbulent years. Especially within the often dysfunctional and through-out, deeply-divided security and intelligence bureaucracy...

That said, if someone had told me fifty years ago there in Bloemfontein that I would one day write an obituary for Niël Barnard, I would probably have just laughed in amazement.

At the time on the Kovsie campus, the two of us certainly didn't see eye to eye ideologically. And with our respective personalities, we weren't exactly born to ever be close friends on a personal level...

Niël, about four years older than me, was a junior lecturer in Political Science in Bloemfontein when I was a third-year Law student who took Political Science as an extra major With me being not exactly tongue-tied (I had won the national debating competition for Afrikaans high schools in my matric year), my classmates often incited me to get under Barnard's skin, whenever his lectures became a bit too academically tedious. Through hours of often fiery class debates with him about the current affairs of that time, I came to know his outlook at that point as politically severely “verkramp” conservative (and he probably perceived me as an outspoken left-wing rebel).

Great was Barnard's surprise when, a few years later (upon his arrival at the Intelligence Service, as the designated future DG) he found me, the "left-wing" student rebel, there – and to crown it all, then in charge of the South-West Africa analytical desks! (One of my most effective teaser tactics in those varsity debates with him – Barnard being a born and sworn Southwester – was to argue then already that SWA was a millstone around the RSA's neck that needed to be gotten rid of as soon as possible!).

In the several years that I subsequently served under Barnard at the NIS, I was able to observe him as a leader, in very challenging times. Times that were future-defining, seen from the national security angle. Times made extra challenging by the political context of a dogmatic head of government (PW Botha) who did not tolerate dissent. Plus, by our then security bureaucracy's often heated and sly internal politics and tendency to turf protection, operating in silos, and plain personal jealousies.

Thus, Barnard was thrust into a leadership position of a particularly high degree of difficulty and responsibility, which he had to master at a very young age at short notice.

My aim here is not to simply chronologically list Niël Barnard's professional successes as NIS-DG. It has already been sufficiently pointed out by competent NIS members (who had been by his side throughout Barnard's intelligence career), that the Service under him was professionally respected internationally, among peer agencies

However, some of the more glowing tributes to him as head of department have gone too far, in my opinion. Especially as regards how he supposedly totally transformed the Service, as if the leadership and entities that had gone before had had little merit.

In my book it is unnecessary to, in effect, denigrate those who had gone before in order to highlight Barnard’s undeniable merits – especially if doing so does violence to the facts.

As a few examples of this exaggeration (which I highlight here not to disregard Barnard's undoubted contributions to the continued development of the Service, but for the sake of balancing the record) is the claim that he was the first intelligence head to have done justice to the analytical component of the Service. That he, allegedly, had completely transformed the Service in this regard

Barnard indisputably had built substantially and very well on the foundation laid by his predecessors. However, it was General Hendrik van den Bergh who, with the creation of the then Bureau,

established South Africa's first contingent of professional intelligence analysts as an integral part of it. Unlike in the SAP and SADF, where policemen or soldiers were temporarily assigned to doing analysis, at the Bureau we were expert economists, ethnographers, political scientists, or from other such professions, recruited from outside specifically for focused careers as professional intelligence analysts.

The fact is, those of us who were there at the time – through the triple-jump transition from the Bureau to the (short-lived) Department of National Security and then to the National Intelligence Service – know very well that it was still the same team, still in their same offices, charged with the same tasks.

In essence, just with new labels...

And, as I will show, that corps of analysts' fundamental professional ethos and also their foundational view regarding what the true nature of the national security threat was (and what government would be best advised to do about it) did not change in any way, with the transition from Van den Bergh’s Bureau to the NIS under Barnard.

What is true is that Barnard (with his conspicuous intellect and his willingness to listen and learn), mastered not only his leadership task, but also the intelligence picture remarkably quickly. With that intelligence picture, in particular, leading thereto that he underwent a total turnaround in his understanding of South Africa’s challenges and the appropriate political solutions (he himself openly admitted this fundamental change of heart, replacing his erstwhile “verkrampte” views, in his autobiography about his time as a spy boss).

Much to Barnard’s credit, he had the intellectual integrity to admit that his initial assumptions and political views were untenable. This he realised from the moment that he could measure his former views against the realities that the true intelligence picture so clearly showed.

So, in terms of the fundamental intelligence analysis of the true nature of the South African dilemma of the time, it was not a case of Barnard transforming the outlook of his inherited team of Bureau analysts. In fact, it was that old Bureau team of eminent experts such as Cor Bekker and Mike Louw (who continued to lead the Service's analytical component) that completely transformed Barnard's own thinking.

In terms of outward "trimmings" it is true that Barnard's time was marked by innovative and very substantive expansion of the Service's capabilities, products and facilities.

However, it is also true that he took over at a time when, with the dawn of the computer age, intelligence services around the world were experiencing a profound revolution in their profession. Not in ethos or outlook, but in terms of the outwardly visible manifestations of their work.

Within the space of a few years, which just happened to coincide with Barnard heading up the NIS, most services around the world took advantage of computerization and especially the new horizons it opened up, particularly as regards the production and especially the visual presentation of their analytical intelligence reports destined for the eyes of the political decision-makers, .

Again, in South Africa's case, it was Van den Bergh's Bureau that had spearheaded this new technology and that had laid the foundation for the expansion that would come to fruition under Barnard – to the extent that the NIS was internationally recognised by other services as a world leader in the application of the new technology to intelligence. I remember very well how the then head of technology of the West German BND had, during a course I took with them in Munich, half apologetically started his lecture with the statement that he did not actually understand why he should address us NIS guys (and not the other way round), because we were then internationally among the recognized leaders in the field of utilization of computing capabilities in an intelligence context...

One of the most significant applications of the new technology which came to full fruition shortly after Barnard's takeover, was a new system of daily production and distribution of analytical intelligence products (the NIFS - National Intelligence Flashes and Sketches). Of this, Barnard was rightly proud. However, the NIFS was undeniably merely the logical completion of a project that had already been conceptualised in pilot form under Van den Bergh and tested at division level in the Bureau/DNS, subsequently then to be established (with the arrival of sufficient computer terminals) throughout the “new” Service's Research (or Analysis) branch.

I know this first-hand, because I myself was central to this process, as regards it conceptualization and initiation (still under the BfSS/DNS), and then the systematic implementation and expansion of this new reporting system under the auspices of the NIS With my interest in computers, it was I who had first conceived and introduced the system of producing daily analytical reports within my then division (the Bureau/DNS’s old analytical Division “K” that dealt with constitutionally related issues such as those associated with Coloured and Indian politics, plus the Homelands, and of course SWA/Namibia.

Equally, under Van den Bergh already, emphasis was placed on the scientific analysis and interpretation of raw information on the basis of social-scientific and economic theory (that, after all, was why he had specifically recruited analysts with the necessary academic training). Barnard's

great merit was how remarkably fast he learned, and how enthusiastically and managerially brilliant he had actively built upon the foundations of what he had inherited.

To claim that Barnard had “restored” the integrity and ethos of the Service (insinuating that what had preceded the NIS was something apparently horrifying?) is also an overstatement. Moreover, averring same is an unnecessary insult to the integrity and honour of all who served in the Bureau at the time (and subsequently continued to form the vast majority of the “new” Service's corps).

The Afrikaner politics of the era must be remembered here, because the PW Botha camp's needs and concerns provided the context for such higher claims. This was the time of (and just after) the palace revolution against Prime Minister Vorster, Drs Connie Mulder / Eschel Rhoodie and General Van den Bergh.

A coup that was instigated to put PW Botha and his militaristic circle in power.

During and after this "bloodless coup" underhand tactics were used that today would be called "fake news" and "lawfare". Especially in the form of the so-called Information "scandal" and the thoroughly manipulated, always politically self-serving Erasmus Commission.

Practically all of the aspersions then cast on the old Bureau and Van den Bergh (with Barnard subsequently being held up as a saving transformer and restorer of integrity) actually stemmed from the Botha regime's political need to destroy the image of their predecessors, rather than being based on empirical facts. However, that wheel would turn... (For more on the Palace Revolution, you can read this article: "QUIET COUP D'ETAT" AGAINST PM JOHN VORSTER - Nongqai BLOG )

An example of the ethos that Barnard did continue to cultivate and which he rightly presented in his autobiography as characteristic of the steadfast approach of the Service's analysts, is that we were always bound to convey to political decision-makers what they needed to hear, and not what they wanted to hear – something we did without hesitation.

The example that Barnard presented in his autobiography of such unwavering standing by the facts was that of a young analyst who did not succumb during an altercation with the then AdministratorGeneral of SWA, the formidable Dr. Gerrit Viljoen.

I noticed that my fellow former ambassador, Dr Riaan Eksteen, stated in his sharp personally critical review of Barnard's book that in his opinion this story is so highly unlikely that it could hardly be true. In his view, it rather serves as evidence of the "self-serving exaggeration" of which he accused Barnard.

Again, I can personally attest that this incident did indeed happen and that it was by no means exaggerated in the book. I was that analyst, at the time at the head of the SWA analytical desks. In that particular case, I was my department's (DNS) representative on a high-level interdepartmental fact-finding mission to Windhoek, sent there by the cabinet. Other members were Niel van Heerden, who represented Foreign Affairs, and senior officers of the Armed Forces and Security Branch. Viljoen was so dismayed by the analysis I had presented of what actually was going on in the border war, that he immediately phoned my then head of department, Alex van Wyk, to personally complain about how "precocious" I was, due to me having stood so firmly by our analysis – one that did not serve Viljoen's (and the SADF's) political narrative.

Upon my return from Windhoek I was immediately called in, on the carpet in front of Van Wyk, Cor Bekker and Niël Barnard. They in no way condemned me but in fact encouraged me to "keep up the good work, but to please try to not make people so angry unnecessarily...".

The only "error" in the account of this incident in Barnard's book is therefore regarding chronology – this had happened still under the banner of the DNS iteration of the Service, with Van Wyk as DG. Barnard was already present that morning, because of him then doing his six month “apprenticeship” consisting of preparatory orientation with a view to the eventual takeover of the later NIS iteration, which then still lay several months into the future.

This chronological context is important, not in support of Koedoe Eksteen's doubts about the veracity of the story, but in support of my position that the ethos of incorruptible analysis was not newly introduced by Barnard, but was already integral in the Bureau/DNS days. For more details on this incident, please click on the following link: NONGQAI SERIES THE MEN SPEAK Dr Willem Steenkamp Part 2 - Nongqai BLOG

The essence of the Bureau/DNS/NIS's threat analysis regarding South Africa itself was always that the country was essentially confronted with a political dilemma, and that a political issue cannot be solved militarily.

If you don't put out the fire under the porridge pot, then sooner or later you won't be able to keep the lid on it – it's going to boil over.

This fundamental insight was ultimately crucial in bringing the De Klerk government back to the negotiation-based strategy of Premier John Vorster. However, it would be laying claim to too much, if it were to be suggested that exclusively the NIS/Barnard had at the time held this (correct) insight. This position was also strongly articulated, for example, in an early February 1987 Security Branch memorandum to Cabinet, in which my late father had made it unequivocally clear that the "blue line"

would not be able to last forever. He therefore repeatedly advised that it was appropriate to start negotiating for a political settlement without delay, doing so while the government could still engage from a position of relative strength.

What my father and Barnard also wholeheartedly agreed on was that we had to stop looking for a communist behind every bush. Non-White resistance, for one thing, could not be fully, nor even primarily, attributed to Soviet incitement. It was essentially Black nationalism, in its essence no different from the Afrikaner's own resistance to domination, my father wrote...

It should be mentioned here that my father as head of the Security Branch held Barnard in high professional esteem. He also knew Barnard much better, in the work context, than some of the other peers who headed other components of the security/intel community knew him. This was because, whereas the others knew Barnard only in the interdepartmental context, my father had been seconded to the top management of the NIS for some length of time as then the permanent SAPSB liaison with the Service, before he became commander of the SAP-SB. Thus, his office was there inside the NIS head office in the Concilium building. As a member of the NIS top management, he sat in on everything, including having been part of the NIS team at the crucial meeting held early in Barnard’s reign at Admiralty House in Simon’s Town to settle between the different services their different jurisdictions (where Barnard in fact saved the NIS, which Military Intelligence – and some in the Police, such as Johan Coetzee – had wished to effectively see disappear).

My father thus not only knew Barnard in the inter-departmental context (as between heads of services) but, had earlier also been able to observe and assess him in his day-to-day leadership, within the context of the NIS as such.

In addition to the correct threat analysis arrived at by the NIS and SAP-SB members like my father, the Department of Foreign Affairs obviously also had had complete clarity throughout that seeking a negotiated political solution would be the only workable strategy

Although I’m writing here from a “within the intel-community” perspective, it is very important to stress that the experts at the Department of Constitutional Development had also held this same view from early on, leading for example to their input to the so-called “Skrik vir Niks” (fear nothing) report of recommendations for fundamental change that had emanated from the non-security state departments around 1987 – which expert advice PW and the “total onslaught” brigade again roundly ignored. (I have it on good authority from within the then Secretariat of the State Security Council, that they as a matter of course had always sought inputs on constitutional matters not from Constitutional Development, but from the NIS).

The political scientist Prof Fanie Cloete, who at that time had been centrally involved at Constitutional Development with the formulation of that input (which had been signed off by21 senior representatives of different civilian departments) is on record describing its gist thus: “The report concluded that the only way to avoid a revolutionary bloodbath in South Africa, was to implement a blitzkrieg of immediate strategic reforms. These reforms included the temporary suspension of parliament, the unbanning of black liberation movements, the release of political prisoners, and an interim GNU representing all South African citizens to draft a new constitution based on a number of non-negotiable principles providing for racially fully integrated democratic legislative and executive political power-sharing among all South Africans at all levels of government.”

Soon after Barnard eventually took over as DG of the “new” NIS, and thanks his keen interest in implementing a daily reporting system throughout the analytical branch, I was promoted to help head the new division N.11 – the central redaction and coordination component for the entire analytical production of the Service, charged initially with rolling out the new system and subsequently with managing the daily intelligence flow.

This division fell directly under the Chief Director who headed the analytical branch (called “Navorsing” or research in Afrikaans, hence his alpha-numerical designation as N.1). N.11 thus served as a kind of staff officer component to him, in which capacity I also performed duty as secretary to the interdepartmental coordinating intelligence committee (commonly called the “KIK”, in accordance with its Afrikaans acronym) which was managed by the NIS

Since it was N.11 that edited the input received from the analytical divisions and from it compiled the first draft of the daily NIFS report for consideration by the “Sanhedrin” (top management) at their early morning sessions, where we had to capture and formulate any changes decided upon, I regularly sat in on those meetings.

Furthermore, Barnard knew of course from our university days that my other field of study (parallel to Political Science) had been Law. Since the Service did not have its own legal advisory component when he took over, he therefore started tasking me with preparing legal opinions for him whenever needed.

In the N.11 context as editor, as KIK secretary and as “legal advisor”, I thus had frequent direct contact with Barnard (in other words, not in the typical indirect manner, with a number of hierarchical levels between us, that was the case when I had headed the SWA/Namibia desks).

All of these roles at N.11 had provided me with an ideal perch from which to observe him at problemsolving (such as when a legal problem had surfaced). As I will come back to later when discussing

Barnard’s contribution regarding strategy, it also allowed me first-hand insight into issues that would later become key. Such as: when to release Mr Mandela (reviewed within the KIK context) or, how best to try and manage what we knew had been for many decades already a deep rift within the ANC (between the moderate non-racialists and the Africanists – with the latter bent on a “National Democratic Revolution”, if necessary to be achieved in two steps, as had happened in Tsarist Russia).

This “privileged observational perch” at N.11 lasted till my request for a transfer to the Service’s clandestine collection component was eventually approved (which I had requested in order to expand my professional experience). At that time, a proper Office of Legal Counsel was established.

Of course, in my new, highly compartmentalised covert capacity I had no further contact with Barnard, nor could I ever set foot again in the Concilium Head Office complex

In fact, my next (and only) direct physical presence at any of the more or less “open” facilities of the Service was during the transition to democracy, when – then as ambassador – I was asked to present a lecture to the joint intelligence transition team (at the Intelligence Academy on the Rietfontein “Farm”) regarding the role and function of intelligence withing the political system – as per the theme of my doctoral dissertation.

The real value of Barnard's contribution to achieving a peaceful transition (and his contribution was indeed great, especially in getting the process officially kicked off) went far beyond his achievements in managing and expanding the Service as such.

With the broader institutional perspective that my own later life has offered me, I would like to shed some light on the key role that Barnard (and the Service) played in the late eighties in averting a potential bloodbath in South Africa. Referring here to the fact that it was the NIS that, for the first time, had established a concrete – albeit secret – liaison channel with the external ANC and actually met with them at senior official level. In this way the NIS reversed the one-time PW Botha ban on any contact with the external ANC This was a laudable and crucially important breakthrough. Even if the NIS did it – as I will point out – by way of presenting the FW de Klerk government with a fait accompli for which the NIS had “obtained approval” through a slight of hand (but which does raise normative questions about whether it ever behoves any intelligence service to effectively force vital policy decisions by deed, rather than purely by means of the analytical intelligence product they convey to those elected to take government decisions).

Be that as it may, it indeed resulted in a breakthrough in terms of government strategy that ministers Chris Heunis and Pik Botha had not been able to achieve...

Undeniably, it was that first official meeting in Switzerland in 1989, between the NIS's Mike Louw and Maritz Spaarwater on the one hand, and Thabo Mbeki and Jacob Zuma on the other, that got the negotiation process going (an initiative that had potentially held quite some risk for Barnard and the Service).

Thankfully, as history records President De Klerk did get on board with it, so that negotiation once again became the official government policy. This had cut the knot of PW's ban on any official conversation with the ANC (which had previously cost officers such as Cloete and Jordaan of Constitutional Development their security clearances and thus their careers in government service).

Against this brief introductory background sketch, my goal will now be to help contextualize Barnard's contribution on a strategic level – rather than just documenting his managerial accomplishments.

Barnard's job description as DG of the NIS obviously encompassed much more than just management. It is fundamental to that position that Barnard and his analysts (headed by Mike Louw – whom Barnard was wise enough to listen to) had to inform and advise the top political decisionmakers on threats to national security as well as strategic options for dealing with the those threats.

The Service's undeniable contribution, therefore, was in the strategic field, fundamentally changing government policy and strategy. Away from the "total onslaught" strategy of preparing for war, back to negotiating for a political settlement.

This result was possible because Barnard and his team understood the true nature of the real threats and were able to conceptualize the optimal counterstrategies – as said, not that they alone had come to those conclusions, but they had the necessary credible standing to allow their voice eventually to be heard Even though such analysis during those years had run directly counter to the then still Apartheid-inspired political policy of PW Botha and also to the prevailing strategy propagated by the "total assault" brigade in the SADF.

PW Botha did not know the young Niël Barnard personally when he appointed him as DG of the NIS. Niël's doctoral dissertation (in which he had made the case for a South African nuclear deterrence capability) naturally had fitted in with the Defence Force's world view. PW Botha, who before was constantly at loggerheads with the then Bureau and Lang Hendrik van die Bergh, was, in my opinion, mostly motivated in his nomination of Barnard by an objective of "I'm going to make you Bureau bastards understand your irrelevance". This he did by way of appointing such a young outsider over the heads of the "old hands" of the then Bureau, as DG of the newly re-titled National

Intelligence Service. Barnard being someone whom he felt would respect the primacy that PW wished to accord the SADF.

Because Barnard was parachuted in by PW as NIS-DG, therefore making him entirely dependent upon PW's good will (since he had not worked his way up through the ranks), it is undeniably the case that Barnard could very easily have chosen – like the many other yes-men with whom PW surrounded himself – to just keep “going with the flow” within that "total onslaught" brigade's perception of reality. Especially since their outlook had admittedly embodied his own initial views.

The fact that Niël Barnard – after seeing and quickly beginning to understand the real intelligence picture – had had the intellectual honesty to realise that his initial beliefs were wrong, speaks volumes for his integrity and sharp insight. He realized that, proverbially, the emperor (in terms of policy and strategy) was without clothes. Many could see it at the time, but few were willing to admit it, and still fewer were willing to take the necessary action to set things right before it could quite possibly have become too late...

What was it that had so deeply divided the security and intelligence community at the time? Essentially, it was a battle around the nature of the threat faced and, consequently, about the best strategic options.

Coming since the days of John Vorster, it had in essence been a dispute about choosing between shooting or settling (which may appear to be an over-simplification, but which is nevertheless aptly descriptive, as I will show).

The men with the big guns had wanted to retain political power at all costs – in final analysis, with military force. They saw as inevitable a coming armed conflict over who would hold political power and thus own the country, so that (in their view) the highest priority had to be to prepare the entire state and society for total warfare against such a total onslaught. They were not blind to the need for there to be at least the semblance of political change, but the real power had to be retained at all cost

Their strategy, then, was to try to dictate incremental change from above, following the (later discredited) model of the American political scientist, Samuel Huntington.

This culminated, for example, in the disastrous enforcement of the tricameral parliament, which PW had refused to negotiate with the non-White majority in advance, against the explicit advice of his own intelligence community as conveyed to him by the Secretariat of the State Security Council (which had correctly predicted that imposing it was only going to inflame political resistance even higher).

Those in favour of seeking a settlement, on the other hand, realized that the very attempt to try and keep control over political power would bring about the white minority's downfall. It was recognized that it was precisely this unwillingness to recognize majority rights (and ipso facto to relinquish real power) that caused the fire under the porridge pot to burn higher and higher, both domestically and from abroad.

Rather than continuing to fight to the bitter end for the preservation of total power, the side wishing to settle believed that the offer of an orderly, peaceful transfer of political power should be used as a carrot to ensure that the constitutional model under which such power would be exercised in future, would be based on Western democratic and capitalist values.

The danger, in their view, was not so much who would acquire power, but rather: in terms of what type of constitutional dispensation it would be exercised. Certainly, the revolutionary imposition of a Marxist People's Republic (as then still advocated by the ANC/SACP alliance) had to be averted at all costs. However, doing everything to avoid a People’s Republic was not necessarily synonymous with the whites striving to retain all power to the exclusion of non-Whites' rights.

Evidently, the quid pro quo of exchanging the power then held by the whites as colonial heritage, by swapping that for an acceptable state model based on Western values, could only be put into play and legitimately concluded by way of truly free and inclusive negotiations leading to a settlement based upon sufficient consensus

In the media and in academia, as well as in political discourse in general, this debate within the security and intelligence establishment about “shoot” or “settle” as strategic options did not really figure – in the public arena there was discussion about things like being “verlig” or “verkramp” (literally, enlightened or cramped, broadly meaning leaning somewhat liberal or towards very conservative). Also, about what types of constitutional models would theoretically be best, or about which Apartheid measures were petty and could be abolished.

Within the intelligence community, on the other hand, it was precisely this conflict over strategy –whether to prepare for inevitable shooting in order to maintain power, or rather to prepare well and in timely manner for an inevitable eventual settling, that was the primary dividing factor, already from the late sixties onwards.

It was also the configuration of the intelligence community as such that, since the establishment of the Bureau in 1969 (under Van den Bergh's leadership, as official Security Advisor to the Prime Minister), that had caused conflict. Van den Bergh had been seriously at odds with PW and the military leadership. Essentially because the latter believed that they and their input on strategy did

not carry the weight they thought it deserved within this new configuration (this, in addition to the intense interpersonal feuds between PW and Lang Hendrik).

There is still today a perception that Vorster and Van den Bergh had doggedly wanted to cling to Apartheid. This persists, despite all the evidence of what they did with regard to, for example, putting SWA/Namibia on the road to a negotiated non-racial dispensation. At Nongqai , we received evidence from impeccable sources that Vorster had already during his reign stated privately, in confidential conversation, that Apartheid could not work.

Looking at how Vorster, Van den Bergh and the Foreign Affairs team of Minister Hilgard Muller and Dr Brand Fourie (as ably supplemented by the efforts of the erstwhile Information Department – Drs Connie Mulder and Eschel Rhoodie) had approached the SWA/Namibia and Rhodesia conundrums is revealing as regards the strategy which they had in mind for resolving South Africa’s own situation

What I experienced first-hand when I headed up the BfSS/DNS analytical desks on SWA/Namibia during the latter part of Vorster’s reign, was that Vorster and his team had understood the defining importance of process over fixating about policy positions. They understood that no policies unilaterally dictated by any side would be accepted as legitimate. The only policy positions that would be internally and internationally acceptable, would be those born out of and shaped by the give and take of an inclusive, legitimate negotiation process. The fact that Southern Africa was at a crossroad and that it was imperative that peaceful settlements be reached, was publicly very clearly articulated by Vorster already on 23 October 1974, when he unequivocally stated that the alternative to peaceful settlement would be “too ghastly to contemplate”.

“Apartheid” could thus be no more than an initial bargaining position (simply because of being the then pre-existing reality, as thus the historical point of departure). Neither Apartheid, nor any clever permutation of “power sharing”, qualified voting rights, or for that matter Marxist People’s Republic could be put forward during such a process of negotiations by any one side as an immutable goal. Nor could peace be assured by attempting, top-down, to manage by force a series of incremental changes (leading to what, and when?). To be credible and acceptable, the chasm between endless conflict and peaceful co-existence had to be leapt in one jump.

Legitimacy and acceptance of the final outcome would be assured not so much by the WHAT of the constitution (throughout history, there hasn’t been one single “correct” answer as to what a perfect constitution should contain, applicable to all places and all times). So that the exact form that the eventual constitution would or should take, could not be precisely predicted, nor imposed, at the outset of the process.

It was thus the process of negotiation itself that would produce the final form. What was essential, was therefore to prepare your side as best as possible for participating effectively in the negotiation process. To hold as strong a hand of cards as possible. Not having given anything away, gratuitously, beforehand. Focusing on seizing the initiative, on having allies, and crucially on being seen as credible and trustworthy Achieving such respect and acceptance by not trying to dominate and unilaterally impose your will – whilst all the time ensuring also that your side is subliminally perceived and understood by the others to be a key party whose fundamental interests and strengths had to be very much taken into account by them.

In other words, Vorster and his team understood that there was no point in first trying to reform Apartheid, or to try to incrementally enforce change from the top down, in a manner determined by them alone. They understood that they would, first and foremost, need to accept negotiations as the only legitimate way forward, and then trust in the strength of the cards they could muster and in their own negotiating ability, all the while doing their utmost to prepare the ground as favourably as possible and well in advance, thereby to strengthen their hand as much as possible.

Which isprecisely the strategythey had implemented in SWA/Namibia, ablyassisted by the superbly competent Dirk Mudge and the allies he could quickly muster. The Vorster team furthermore understood that international legitimacy would in large part also be bestowed by acceptance on the part of the African states, hence the emphasis on détente and on building relations with them.

If peaceful transitions could be achieved in Rhodesia and in SWA/Namibia, it would have as very important consequence that it could provide a road map for South Africa itself and help incline white South Africans to accept the previously unthinkable, based on proven success… Even though I know from own experience that the military had mostly held illusional expectations that the “moderates” would win in those territories, I know equally well that that had not been the clearlyexpressed assessment of the non-military component of the intelligence community – of people like my father and myself (based on simple ethno-demographic reality); it is therefore in my experience not correct to assume that the acceptance of the need to negotiate non-racial constitutional dispensations was actually driven by fond though unrealistic expectations that doing so would somehow lead to whites being able to retain disproportionate power or privilege.

Vorster’s strategy of negotiation rather than confrontation which dated from the late sixties had showed early promise, at least till PW Botha’s disastrous foray into Angola in 1975 and the subsequent worsening of South Africa’s own internal situation What was nevertheless significant regarding white politics in the subcontinent was that the SWA/Namibia experience (as embodied in the Turnhalle process), did in fact demonstrate clearly that a conservative white populace could be convinced to put their trust in a non-racial constitutional dispensation – as more than nine out of ten

white Southwesters in fact did, when they voted in the referendum held amongst them to approve of the Turnhalle constitution. This fundamental acceptance by otherwise conservative, mostly rural Afrikaners in SWA that a non-racial dispensation was both inevitable and necessary, I actually saw illustrated not only by that referendum’s results, but by a very thorough scientific opinion survey conducted beforehand among SWA whites in which I had been intimately involved This in-depth testing of opinion showed that there were no illusions nor false expectations – just the commonsense realism for which common folk are not often enough given credit.

It is sad history that Vorster’s initiatives regarding SWA/Namibia in the end came to naught, when PW Botha took over and slammed on the brakes (as one general told me late one night in the Kalahari Sands hotel in Windhoek: war over who would own South Africa was inevitable, and the SADF needed battle space to “bleed in” our troops and give them combat experience – which the SWA/Angola arena conveniently provided…).

Fact remains that Vorster clearly had understood the inevitability of resolving Southern Africa’s conflicts through negotiations, from which non-racial constitutions would equally inevitably result (as demonstrated in the case of Zimbabwe and later fully confirmed in Namibia by the late eighties, when even PW had to succumb to this reality – only, after ten wasted years, and then with far fewer cards in hand). Of equal importance was Vorster’s understanding that the emphasis should be on the negotiation process (and properly preparing for that) rather than focusing intra-governmental debate on developing all kinds of policy positions (i.e., constitutional models) to be incrementally imposed from above – because the latter approach was akin to re-arranging the deck chairs on the Titanic, instead of realising that the ship was irredeemably doomed and an entirely new vessel urgently needed to be found…

The same necessity to trust in negotiation proved to be true of South Africa itself, as eventually understood by FW de Klerk and his team – again, unfortunately, a lost decade later and without time for the careful building of alliances that had marked Vorster’s thorough preparation for SWA/Namibia.

As regards General van den Bergh and his understanding of the fatal flaws in Apartheid, he himself had also made it clear in his unpublished autobiography that he was well aware of these. One such fundamental defect was that, in his view, “Separate Development” offered no logical solution with regard to civil rights for the so-called Coloureds and Indians, and that the tricameral parliament would neither work nor gain acceptance

The main defect of Apartheid that he identified, however, was that the policy did not provide for what Van den Bergh saw as the country's greatest single challenge. Which he understood to centre around South Africa's most important demographic, economic and geographical reality – namely,

that the vast bulk of the country's most economically significant surface area was in fact "shared territory", inhabited and worked upon by all population groups, inextricably intermingled (in this regard, he had concurred with prince Mangosuthu Buthelezi’s position).

That is why, for example, Van den Bergh had us, his analysts, investigate the possibilities of a unitary state model organised on consociative principles.

Under Vorster's team, it was axiomatic that strategy should be focused on preparing well and timeously for holding the best hand of cards possible when inevitably the parties had to sit down at a future negotiating table. Therefore, Vorster and his team took the initiative with regard to such preparation (such as through seeking détente with Black Africa) so that negotiations would not ultimately be forced upon a South Africa unprepared for it... On this score, the Bureau, Foreign Affairs, Department of Information and quite a few in the Police (such as my father) all had agreed.

On the other hand, there were many in the forces, especially in the Army under Magnus Malan, who saw the strategy of preparing for negotiations (as embodied in Vorster's détente initiative and the process of encouraging Rhodesia and SWA/Namibia to move to majority rule by way of negotiation) as a sell-out. This group’s political leader was the ambitious, abrasively self-centred PW Botha.

The PW Botha/Magnus Malan contingent's approach of trying instead to dictate incremental cosmetic change top-down, and to rely on physical force in South Africa’s relations within the region, had led to many conflicts already under Vorster and especially with Van den Bergh – internal conflicts within government that were brought to a head by the overthrow of the Caetano regime in Portugal in 1974 and the independence of the one-time Portuguese colonies.

Few people realize how fierce this internal struggle was, and what significant consequences it would have. PW, as defence minister, followed his own head, launching operations on his own authority. Vorster and Van den Bergh, for example, were only able to stop our forces at the last minute at Komatipoort, when PW had ordered them to enter Mozambique to take over the radio station to support a planned coup in Lourenço Marques by right-wing Portuguese settlers there.

Another example was PW's support for Zambian rebels who wanted to overthrow Kenneth Kaunda – this, while KK was a key interlocutor for Vorster in his détente initiative.

Eventually, PW's wayward military decisions under (but not approved by) Vorster, taken without due consultation nor authorization, culminated in him transforming what had only been authorized as no more than rendering training assistance to UNITA, into a full-scale conventional advance by South African troops in own uniform and armour on Luanda, to try and take it over (Ops Savannah). A

strategic catastrophe that resulted in massive deployment of Cubans into our region, but – more importantly – that sank Vorster's détente.

In strategic-psychological terms, the consequence that we at NIS had most feared (and then saw come true before our eyes) was that when Operation Savannah inevitably failed, it would puncture our balloon of invincibility. In the perceptions of South Africa's non-White population and the rest of Africa, from the moment that they saw the SADF obliged to abandon their Savannah incursion, White South Africa was no longer invincible. The insistence on the transfer of power inevitably began to flare higher soon after, as illustrated by the outbreak and rapid spread of the Soweto riots from June 1976 onwards.

The "total onslaught" men may have thought that they had won the battle against the "settle" faction when Vorster was brought down in the palace revolution instigated through the Information "scandal", when in 1978 PW Botha was elected as Prime Minister bya narrow margin, helped across the line by Pik Botha.

An octopus-type control mechanism to keep the entire bureaucracy in line was soon introduced, in the form of the National Security Management System or NVBS by its Afrikaans acronym (created by decree, outside of the provisions of the Act on Security Intelligence and the State Security Council). The SADF was firmly ensconced in the chair.

Nevertheless, Foreign Affairs for example continued with their negotiation initiatives and was able to obtain cabinet approval for the Nkomati Treaty. However, Prime Minister PW Botha told the SADF that they need not bother with this Accord, to the great detriment of our international credibility. The Defence Forces' wilful ignoring of the Nkomati Treaty led, among other things, to serious headbutting between Niël Barnard and Constand Viljoen as head of the SADF, with Barnard lashing out at Viljoen in a call to him over the SADF's flouting of what was a Cabinet decision (the one that had authorised the treaty – at that time, the Cabinet was still the highest executive authority under the then constitution, which PW then immediately wanted to change).

It must be said at this point that Barnard (his nickname behind his back among other department heads was: Billy the Kid) was not a beloved personality outside of the NIS

Stiff and regarded by many as condescendingly intellectually superior, he made more enemies than friends in the bureaucracy. Because the NIS's field of responsibility encompassed reporting on everything that affects national security – including what might go wrong in other departments' areas – the typical bureaucratic trend of everyone wishing to crow from atop their own dung heap didn't work in his favour either...

Be that as it may, back now to PW Botha and his autocratic management style and the battle between the “shoot” and “settle” camps. It is an open question to me, to what extent PW's stubborn insistence, against advice, to force through the constitutional changes of 1983 (which included the gimmick of the tricameral parliament) was in fact more motivated by the other leg of those changes – being, to abolish the cabinet system of joint authority and make him executive president, with extraordinarily broad powers centralized in his person...

Continuing his disapproval of negotiation, PW immediately had begun to undo the hard preparatory work of his predecessor in SWA/Namibia (with the establishment of Turnhalle process and the creation of the non-racial DTA alliance). The last major decision of the previous cabinet, namely, to accept UN Security Council Resolution 435, was put on hold and PW began to put pressure on Dirk Mudge and the DTA to revert to a more ethnocentric ("Apartheid") vision, which eventually culminated in a total rift between him and Mudge.

Pressure on the South African government to start negotiations began to ramp up seriously by the middle of the decade, both domestically and internationally.

Another catastrophe came quickly enough, in 1985, with PW's "Rubicon" speech.

A week before the date set for the speech, the cabinet had met for a brainstorming session at the old Observatory (part of Military Intelligence's training facilities at the time). I’ve had sight of the recently unearthed entire verbatim transcript of that meeting. Contrary to what people like Pik Botha had later pretended, fundamental political change and a consensus text for PW’s speech (from which PW then supposedly had deviated in delivery) were NOT agreed upon during that brainstorming session.

In fact, Pik was uncharacteristically quiet all the time.

Chris Heunis, then in charge of constitutional planning, was the only cabinet minister who at all had tried to advocate that the circumstances (Chase Manhattan bank had just caused the Rand to stagger with the refusal of further loans) necessitated a new direction to be announced, but his circumspect pleas were not accepted by PW.

It was evident that PW Botha would deliver his own speech. However, those who had wanted to, could present draft inputs to him. The Departments of Constitutional Development (Heunis) and Foreign Affairs (Pik Botha) did indeed prepare separate such drafts. PW didn't even want to invite Heunis into the Groote Schuur residence – snapping at him from the porch that Heunis could forget about him (PW) delivering that "Prog" speech (i.e., favouring negotiations) that the experts at constitutional planning had drafted

Pik Botha, however, had evidently hoped that he could paint PW into a corner by pushing ahead and widely promoting the draft prepared by Foreign Affairs, overseas and in the media – as if that was what PW was set to announce. It contained the “crossing the Rubicon” analogy and was touted by Pik in Vienna and elsewhere as heralding a brave new direction.

However, the only portion of that draft which PW eventually used in his own speech, was the Rubicon phrase... His focus was not on announcing any fundamental change in policy, but instead on making it abundantly clear to the world that he would not allow himself to be prescribed to. Given what Pik has been foreshadowing in Vienna and elsewhere, this message from PW was obviously experienced exceedingly negatively, both domestically and abroad.

I'm referring to this incident, not to re-hash the past, but to point out how fierce the battle was between either negotiating or rather sticking to “shoot” and – if necessary – to eventually "go down hard-arsed" (“hardegat ondergaan” as per PW’s own words to Barnard, which Masada-like outcome increasingly appeared to PW to be our only remaining option).

PW Botha would not tolerate discussions with the external ANC/SACP alliance, and the consequences for any official who violated this edict were severe (as Cloete and Jordaan of Constitutional Development found out, when Jordaan went on one of the "African safaris" to meet with the external ANC).

Pik Botha would soon once again try to paint PW into a corner about entering into negotiations. During the visit of the Commonwealth's Eminent Persons Group (EPG) in 1986, Pik prepared for them a text of points on which he told the EPG that the SA cabinet would be willing to agree, with a view to starting negotiations – if only the EPG would agree with him to use his text as their statement about the way forward. The EPG then in good faith released Pik's text as their own. PW's response to this consisted of an Air Force officer phoning up Niel van Heerden at Foreign Affairs with the news that the bombers were already in the air to attack the capitals of the Frontline states... Of course, the EPG immediately packed up and left, convinced that the PW Botha government was not amenable at all to negotiations, and even stricter international measures soon followed.

Not to dwell too much on how PW saw fit to browbeat Margaret Thatcher’s Foreign Secretary, as well as Ronald Reagan’s ambassador…

As can be seen, even during the late eighties the "shooting" faction remained unwilling to give in to those who could see that settle was the only viable way forward. However, the balance of power within government began to change when the conflict in southern Angola began to go badly wrong

militarily, with a costly stalemate at Cuito Cuanavale and Castro then opening a second front north of Ovamboland. Advanced Cuban MIGs started flying through our airspace. (Barnard is alleged to have, in later years, privately mentioned to a confidant that those MIGs had in fact even flown above the Union Buildings).

A Citizen Force contingent of 140,000 men was called up. The Army's first battle plan was to go in even deeper and "clear" south-west Angola of Cubans, including the port of Namibe (Ops Excite/Faction, part of Ops Hilti). However, this fell through when the Air Force and Logistics made it unequivocally clear that they would not be able to help make such a plan work. Accordingly, as an alternative (if the Cubans did indeed invade SWA), a new battle plan was then prepared in terms of which the Cubans would be allowed to enter as far as south of Etosha, with a "killing ground" to be prepared for them in the northern agricultural districts. (Ops Prone/Pact, part of Ops Handbag).

Full-scale war, then, from the back foot...

Fortunately, Foreign Affairs was able to report that the Cubans simultaneously had reached out to begin negotiations. Also, the NIS had a high-level source in the direct line of command between Havana and Luanda, who confirmed that Castro's deployment of his second front was just bluffing, in order to try to force South Africa to the negotiating table. The USSR had by that time also fundamentally changed their stance about Southern Africa (more about which later) favouring negotiation over continued war. And so, belatedly, the UN Security Council's Resolution 435 was dusted off again and finally implemented (as Vorster already had known to be inevitable). Now however, because of the “lost decade” under PW, with much weaker cards in hand for the negotiations...

CIVIL SOCIETY INCREASINGLY AGITATED FOR NEGOTIATIONS:

Within South Africa itself, the growing insistence on negotiating coming from within business ranks, academic circles, the media and the government’s own constitutional planning experts began to pick up more and more speed, but PW still continued to enforce his dictate within the bureaucracy and assert his influence within the Cape Afrikaans press against any such contact – just look at Rapport's then headline of "DOM DOKTORE VAN DAKAR", (Dumb Doctors of Dakar) referring to those leading academics who went to meet the external ANC in Senegal.

This disorganised situation with all kinds of missions that began to reach out to the external ANC from civilian circles, had worried Barnard. It wasn't because he was opposed in principle to making contact and negotiating. After all, he himself was already in talks with Nelson Mandela (then still in custody), and the NIS had established links with the KGB in previous years. His concern was that uncoordinated efforts could do more harm than good.

Some of Barnard’s detractors from within former government circles criticise him for having supposedly accepted the need for Nelson Mandela’s release only very late. Furthermore, for then allegedly being over-awed by Mandela (even at one point tying Mandela’s shoelaces) and for prematurely accepting that Mandela would be the next president. Without Barnard sufficiently realising that the ANC saw the CODESA process merely as phase one of their “National Democratic Revolution” (the phase of getting rid of the former white regime) and that they would persist in seeking to implement their anti-capitalist, anti-democratic NDR soon after gaining power.

These criticisms stem, I believe, from those that made them not having had full knowledge of, nor complete comprehension for, the intelligence picture that the NIS had known to actually pertain with regard to these matters (which is not a counter-critique, since it was understandable under those circumstances that very few were then let in on these secrets – most of the cabinet, for example, did not know).

I can attest that there was firstly no lack of clarity at all within the NIS about the extra-ordinary personal qualities of Mr Mandela as master politician, as far back as the early eighties already. I remember vividly being secretary to a KIK meeting, convened specifically about how to advise the PW Botha government regarding the issue of Mr Mandela’s detention. Invited to this meeting was the senior psychologist of the Correctional Services, who had been pertinently tasked with observing and assessing Mr Mandela on a continuous basis – which he had done for a considerable length of time and great acuity. This gentleman was very clear: once released, Mr Mandela, with his exceptional charisma and intellect, would run rings around the then crop of white cabinet ministers and would utterly dominate the South African political scene.

One of the Army generals present asked (somewhat disbelievingly) whether the psychologist reckoned that Mr Mandela would run rings around the likes of Dr. Gerrit Viljoen as well? (Viljoen, former Broederbond chair, SWA/Namibia administrator-general and then minister of national education, was regarded as the top Afrikaner intellectual of his time).

The answer of the psychologist was an adamant “Yes!”.

Barnard and the NIS therefore knew two things with total clarity: It would be a disaster for South Africa if Mandela should die in prison, but secondly, that it will be even more of a disaster if he should have been released at the wrong moment. As much as Mandela needed to be thoroughly prepared for his release (to which Barnard himself would later assiduously attend) it was absolutely necessary that the context into which he would be released, be prepared and be conducive to a positive outcome

There would probably be only one chance to do it right (in terms of thereby achieving the desired result of putting the country on the path to peace) because otherwise, his release held the potential for a sharp increase in confrontation.

It needs to be understood that Mandela could under no circumstances be released as merely a token part of top-down incremental change. Firstly, because Mandela himself would not accept conditional release, or being used in a publicity stunt. Secondly, because, if he was released outside of a pre-agreed framework of definitive negotiations for a new non-racial constitution, then confrontation was sure to follow. Especially if released whilst the authoritarian “groot krokodil” was still at the helm and sticking to his guns, literally and figuratively, that there will be no negotiations for a transfer of power to the non-white majority (just think back and imagine PW and Mandela squaring off in public!) That would inevitably have led to serious political confrontation at the highest level, which would assuredly have spread lower down, and abroad. With the PW Botha government most probably not being able to handle Mandela as political adversary…

Mr Mandela could, therefore, only safely be released once (and only if) the white government had beforehand been convinced to accept the need for, and had publicly committed itself to fully inclusive, unconditional negotiations for a new non-racial constitution based on one person, one vote

As much as the NIS and Barnard understood this, it was also understood that it would be absolutely essential – also from the viewpoint of white interests – for Mr Mandela to indeed be released. Not as a publicity stunt to curry favour, but because Mr Mandela was the essential persuader needed to ensure that the moderates within the ANC around the likes of Thabo Mbeki, would overcome the hitherto dominant radical Lusaka faction under the likes of Jacob Zuma and Chris Hani.

The NIS obviously knew very well about the decades-old cleft that had existed within the ANC (and which finally came very publicly to the fore in the run-up to the 2024 elections, with Jacob Zuma and his MK party breaking away). We all knew, back then, with total clarity that there were those within the ANC who would indeed see any negotiations as just phase one of their revolution, allowing them to be rid of the white regime, whereupon they could then in typical Marxist-Leninist fashion focus on instigating a second revolution (the NDR) to thereby impose their ideological ideals. About this risk, there had been no misunderstandings whatsoever. The key intelligence question, though, was which faction within the ANC would prevail if the lure of political power was on the table, offered in exchange for constitutional guarantees for minorities and for property rights

The logically necessary sequence of events, from an intelligence perspective, was therefore to firstly obtain certainty about Mr Mandela’s likely future moderate stance (as Barnard was busy doing, in his many prison meetings with him). Then, secondly, to ascertain whether the external ANC was

indeed open to participating in the negotiation of a new constitution. Thirdly, in parallel and doing so through the NIS’s penetration of the ANC’s communications and decision-making circles (by means of the likes of the hugely significant and very successful Operation Cruiser), to ascertain which faction would likely prevail, if Mr Mandela should be freed and then would cast his considerable weight on the side of the moderates. And fourthly, that the environment into which Mr Mandela is released be conducive to peace, through the white government having publicly and unequivocally accepted the imperative need for inclusive negotiations to arrive at a non-racial new constitutional dispensation.

British businessmen with large investments in South Africa in the latter half of the eighties had begun to work on facilitating negotiations (doing so in secret consultation with the Thatcher government) Their focus was on fostering confidential dialogue between Afrikaner leaders and the external ANC This is when the NIS stepped in to create its own channel for future direct contact with the ANC's external wing, specifically with Thabo Mbeki. Because Barnard and his team were not inclined to see “volk” and nation "go down hard arsed" in imitation of PW Botha and his "total onslaught" brigade's Masada fixation...