Cottonera

Three Cities behind Brothers-in-Arms

Three Cities behind Brothers-in-Arms

Text

Christian Formosa

Illustration & Design

Cherise Micallef

Walled Cities of the Maltese Islands Series Editors: Margaret Abdilla Cunningham, Vanessa Ciantar, Fiona Vella and Godwin Vella

Cottonera - Three Cities behind Brothers-in-Arms

Text: Christian Formosa

Illustrations and Design: Cherise Micallef

Printing: Print It Printing Services

ISBN: 978-9918-619-15-3

Produced by @2023 Heritage Malta Publishing. All rights reserved in all countries. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher and respective authors.

Acknowledgements:

Heritage Malta’s Board of Directors, CEO, COO, and staff members in the Conservation, Curatorial, ICT & Corporate Services, and Projects Divisions.

Kottonera Foundation

Cottonera - Three Cities behing Brothers-in-Arms is the second of a series of four publications on the walled cities of the Maltese Islands. The other titles are:

Valletta - my city, my story

Ċittadella - Echoes from a City in Ruins

Mdina - Medieval City with a Baroque Façade

Acommonpitfall in the interpretation of history is the projection of modern perceptions into the past. This is particularly true of Cottonera, which is often viewed as a cluster of unrelated townships. While acknowledging the fact that the imposing fortification lines constructed by the Order of St John partition Cottonera into clearly defined districts, it must be stressed that Birgu, Bormla and Isla are intrinsic and inseparable components of one reality. Their origin and flourishment are directly linked to Galleys’ Creek, the most capacious, sheltered and easily defendable creek in the Grand Harbour.

By default, the Three Cities – as Birgu, Bormla and Isla are collectively known – share the same story, and the importance of this story extends beyond the grand enceinte commissioned by Grand Master Nicholas Cotoner in 1670. It is key to a full appreciation of the island-state of Malta, in particular the past 500 years. Alongside Valletta, on the opposite flank of the Grand Harbour, the Three Cities acted as Malta’s gateway throughout the Order’s and British tenures. The arrival of the Order in 1530 metamorphosed Galleys’ Creek into a bustling maritime hub. Strong trade links with all major ports of the Mediterranean were forged, while hundreds of foreign craftsmen and businessmen mingled with the local folk. For well over four centuries, Cottonera proved to be Malta’s multicultural hotspot.

Trade inevitably triggers cultural influences. The main stylistic trends that prevailed in mainland Europe permeated the local scene in no time. More importantly, these took root in the Three Cities before infiltrating the rest of the Maltese Islands. Cottonera was, to this effect, the national incubator for innovation and knowledge, as confirmed by countless artists, academics, explorers, politicians and scientists emanating from its fold. Indeed, this book is much more than an overview of the history of the Three Cities. It brims with anecdotes of prominent personalities and unassuming folk alike who contributed in the moulding of our nation.

Hon. Glenn Bedingfield Chairman Kottonera Foundation

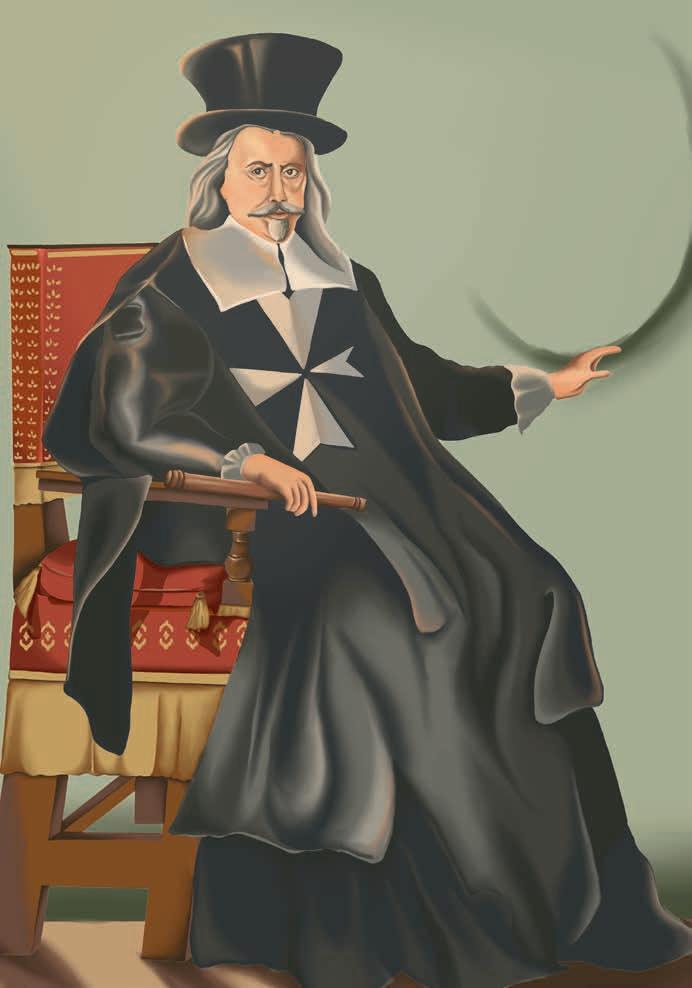

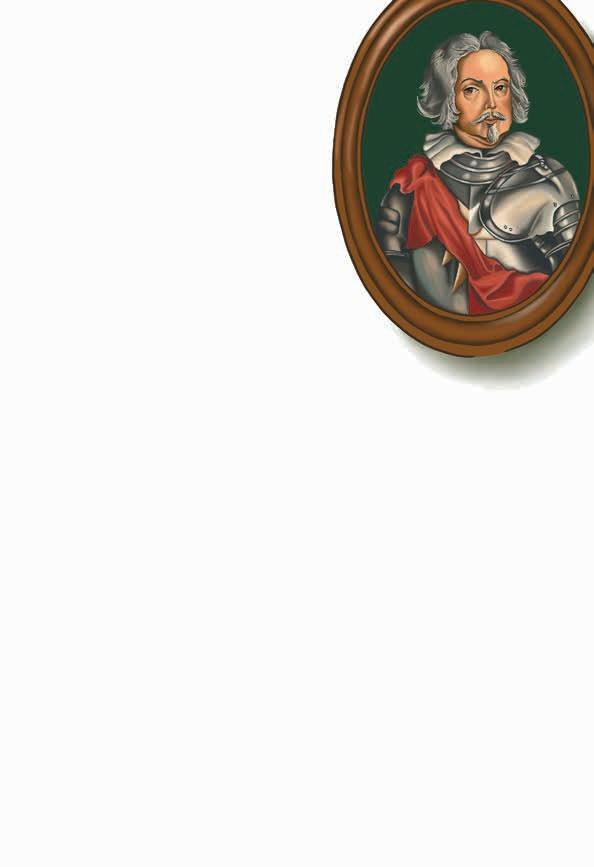

Portrait of Grand Master Nicolás Cotoner and inset of his brother Rafael Cotoner

Portrait of Grand Master Nicolás Cotoner and inset of his brother Rafael Cotoner

I am Fra Nicolás Cotoner y de Oleza. I will be accompanying you on a journey to the Three Cities, collectively known as Cottonera in honour of the most magnificent fortification I, myself, commissioned for the defence of the Maltese Islands. For 260 years, the islands became home for the Knights Hospitaller of the Order of St John. But, let me introduce myself first.

I was born at the beginning of the 17th century in the city of Palma, the capital of the Spanish island of Mallorca. I was one of six brothers. Marcos Antonio, was the leading man in Mallorca, my other brother Bernado was Bishop of Mallorca, and Francisco joined the Spanish Military Order of Santiago. My older brother Rafael, my youngest brother Miguel and I, joined the Order of St John, following the example of our paternal uncle, Nicola, after whom I was named. He was also a high-ranking member of the Order, as he was the Grand Prior of Catalonia.

Young Miguel was determined to follow in my footsteps, by fighting the infidels with his caravan1 on the galleys of the Order. However, his life was sadly cut short at the age of twenty, when he fell in battle. I had to honour his memory ad aeternum, so my brother Rafael and I commissioned a marble tombstone in the centre of the nave of the Conventual Church of St John.

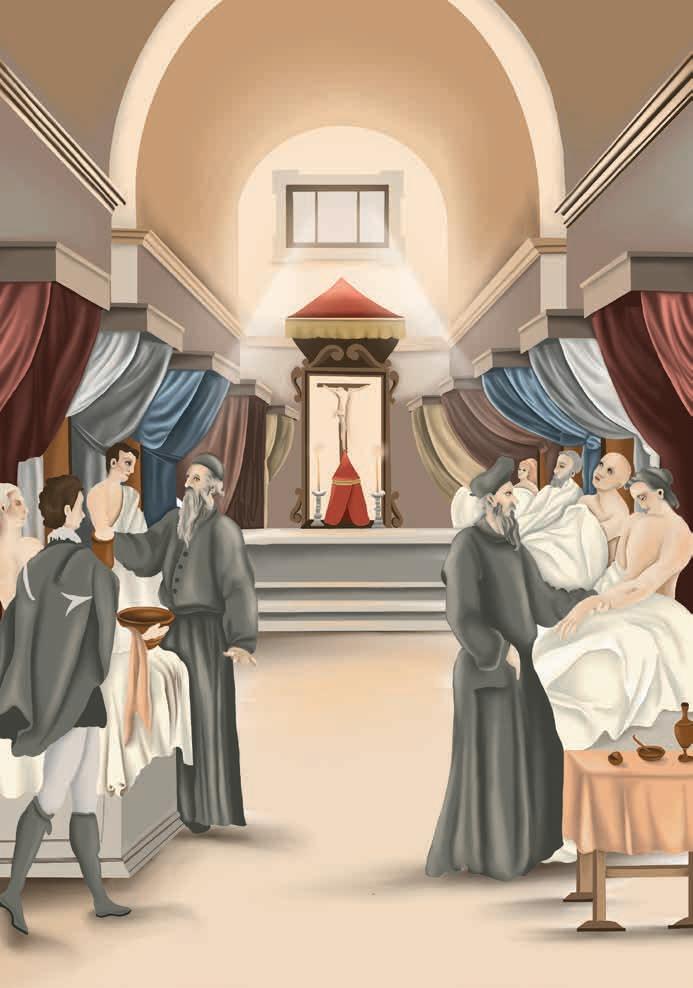

Rafael joined the Order at the tender age of seven, when Fra Alof Wignacourt was Grand Master. Eventually, Rafael served as Captain on the Galley San Lorenzo. Earning great merit along the years, he was appointed Bali of Negroponte and then Bali of Mallorca. A few years later, he was elected Grand Master of the Order, succeeding Fra Annet de Clemont. Rafael undertook the construction of the grand ward of the Sacra Infermeria in the new city of Valletta. This was the largest medical hall, not just in Malta but in the whole of Europe, built to fulfil the aim of our Order as Hospitallers.

The Sacra Infermeria was the envy of all Europe since it offered first-class care to all its patients.

Rafael also set about beautifying the Conventual Church under the direction of Mattia Preti. But life was unfair on him, for he did not live long enough to see the completion of this project.

Like my brother Rafael, in the beginning I also served as Captain on the galley San Lorenzo. Little did I know that a corsairing incursion in 1644 by this vessel would ultimately trigger a war on Candia in Crete, leading to the greatest defense project of the Order on the Maltese Islands. We were sailing under the command of Captain General Fra Gabriel de Chambres Boisbaudran, near Rhodes, when we discovered the largest Ottoman galleon we had ever seen. We were sure that it was loaded with riches, so we immediately attacked.

Unfortunately, during the fighting, Boisbaudran was killed, so I, as the senior captain, took command of the squadron. The enemy ship Gran Sultana was captured after seven long hours of hard combat, leaving 220 people dead out of the over 600 who were on board. Our losses, although not as much, were high too: 82 men, including 9 of my brethren, were killed and 170 wounded. After the battle, we surveyed the booty, which was among the richest to have ever been captured, with more than 200,000 scudi in goods, jewels, silver and gold objects. The galleon also happened to be carrying pilgrims who were on their way to Mecca, including two very important personages, the Sultan’s favourite of his harem, Zafira, and her son Osman. We treated them with the utmost

respect for their status (and of course for their value in ransom). Sailing in winter was always difficult, so on our way back, I decided that we should anchor in the neutral island of Crete, since at the time it was under Venetian rule, to take supplies on board for our return journey. This angered the Sultan, who declared war on Venice. It took us five months to return to Malta.

Following the demise of my brother Rafael in 1663, my brethren gave me the honour to be their Grand Master. I decided to continue the work which Rafael had commenced in the Conventual Church. Preti worked tirelessly to complete the embellishments. On the inside of the church façade, just above the main door, he painted an Allegory of the Triumph of the Order, immortalising my brother and me as the main characters in the painting.

Yet, the greatest project which I undertook was after I became Grand Master, when I built the Cottonera Lines, which I will tell you more about later on in our journey together. I also introduced windmills on the islands, benefiting greatly the local inhabitants since bread was their staple diet. The windmills were built according to the same structure used as in my native island of Mallorca, serving the islands for centuries after.

The closing years of my reign were marked by the great plague epidemic which claimed the lives of 11,300 people. The epidemic began in Valletta at the end of December 1675, spreading widely within a month. The Three Cities were not spared either and within a few months, the plague killed 1,885 people in Isla, 1,790 in Birgu and 1,320 in Bormla. Strict measures, together with divine intervention brought the plague to a halt.

The Sacra Infermeria

The Sacra Infermeria

Clearly, urban areas with high population densities were at a greater risk during such pandemics.

Even the medical profession suffered the plague’s deadly consequences, losing not only doctors but also 16 surgeons. This dire situation led me to take a very important measure, that is to establish a medical school for surgery and anatomy within the Sacra Infermeria in Valletta. Because of its importance, I financed the school at my own expense and, to ensure that it continued to flourish in the future, I sat up the Cotoner Foundation so that the school would enjoy further subsidies. I also worked diligently to ensure that the administration of the Sacra Infermeria was regulated, including the prohibition of smoking and the proper recording of the admission of the sick. Moreover, I made it a point that the infirmary treated patients regardless of their faith. Indeed, when a young English patient was denied treatment after he refused confession, since he was a Protestant, I personally ordered that he should be readmitted and the hospital management had to apologise.

All this turmoil took its toll on my physical health. Unfortunately, my last years were plagued by illness: gallbladder stones, gout and pulmonary afflictions, coupled with paralysis of my leg. I had to be carried in a sedan chair, though I can assure you that I remained sharp until the very end. I left this world to meet my Lord in 1680 at the age of 75.

I was buried next to my brother Rafael, in a splendid monumental baroque tomb designed by Domenico Guidi. I still lie there in the majestic Conventual Church of St John, which I had so ardently embellished, while my heart, like Rafael’s, is buried in our beloved city, Palma.

I think I have said enough about myself. Now, it is time to travel back through the long and colourful years of Maltese history, to see the Three Cities like you have never seen them before...

Our journey together begins a very long time ago, at a time when people had not yet ventured to the Maltese Islands. Look at the illustration, find where you are marked to stand and take a good look around. I bet you still cannot quite recognise the place where you stand. Look at the promontories and hills. Do they remind you of somewhere familiar? If you have not guessed the place yet, I will enlighten you, so that you can understand where we are.

Notice that we are in the middle of a valley surrounded on all sides by hills. What if I tell you that you are standing right in the middle of the Grand Harbour? Actually it should be the bottom of the sea, but there is no sea ... surprised?! The two promontories on the right-hand side are Birgu and Isla, while on the left-hand side, there is the Sceberras Peninsula which eventually will be transformed into the capital city of Valletta. Surely, you must be wondering where all the seawater has gone. This is because we are about 20,000 years in the past, at a time when the world experienced an Ice Age. In this period, a lot of water was trapped in the form of ice at the North and South Poles, leading to the lowering of the sea level in the Mediterranean. Although the Maltese Islands did not experience the Ice Age, meaning they were never covered in ice, but they did have a lot of rain, giving rise to the formation of rivers in already existing fault lines.

When the Ice Age was coming to an end and all the ice was melting, the seawater began to rise until it reached its present level. The seawater flooded these valleys and created the deep, sheltered Grand Harbour, while the smaller valleys on the sides became creeks. The hills between the valleys became peninsulas surrounded by water on three sides. However, I must tell you that in your lifetime, you are in danger of losing this landscape, as the sea level is rising higher and higher due to global warming.

With the advent of men on the islands, the high ground on which the town of Paola is located, overlooking the lower areas of Cottonera, became a hive

of activity as prehistoric people erected various megalithic structures and excavated tombs and cemeteries. There are several reasons why these people chose to live on higher ground, with the primary one being that it was safer, both from natural elements and against human attacks.

In time, people also recognised the potential of the Birgu promontory as a settlement site, since it occupies a commanding position above the Great Harbour, whereas its high ground towards Kalkara and the sloping terrain towards the Porto delle Galere, which you know as Dockyard Creek, offer protection from the gregale winds that tend to sweep over the port.

Ournext stop on this journey through time takes us to the year 870 AD which marks the Arab’s conquest of Malta. But first, let me give you a brief overview of what happened during this period.

By the turn of the 4th century, the Roman Empire which included most of present-day Europe, Asia and North Africa, had become too large to rule effectively. Hence, the Empire was divided in two: West and East. The West was governed by Rome, whereas the East was led by Costantinople (presentday Istanbul). Malta formed part of the Western Empire which eventually was defeated by a people from North Europe, commonly referred to as the Vandals.

In 535 AD, Malta was won over by the Eastern Roman Empire, which by then became known as the Byzantine Empire. The Byzantines regarded the islands as a peripheral land, a land of exile. With the rise of Islam, the fate of the Maltese Islands became linked to events in Sicily. Just a few months after the conquering of Sicily, Malta fell under the control of Dar al-Islam, shaping the islands’ history forever. As Dar al-Islam’s power extended from east to the west of the Mediterranean, the Maltese Islands experienced a period of relative tranquillity, except for the siege in mid-11th century, when the Byzantines attempted to reconquer the Maltese Islands. The Muslim masters asked their Maltese slaves to join them against the Byzantines so that they could repel the attack. Once the attack failed, peace reigned on the island for another few decades.

The Mediterranean was very unstable at the time. The Greeks attacked the eastern part of Sicily, while the Normans assaulted the southern part of the Italian peninsula. Once the southern peninsula was conquered, the Normans continued on to Sicily and finally Malta.

Now let us move to the next stage of our journey. At this time, the land around the Grand Harbour was very different to how you know it today. Close your

eyes and try to imagine this: the harbour with no buildings at all, except for a small tower that rises on the promontory of Birgu. This is the end of the 12th century, a time when the islands of Malta had been under Christian influence for the last century. Nevertheless, when they passed from under Norman hands to the Hohenstaufen, the inhabitants were still perceived as Saracen, except for those living around the tower. Everyday events on the islands were dictated by the ‘presence’ of a Genoese Count of Malta.

Let us now walk together to the innermost part of the Porto delle Galere, where you could find a sandy beach created by eroded material carried down by the springs of the surrounding land. This area was called Bur Mula (the Lord’s Meadow) because the spring water made lush vegetation grow which was excellent for grazing. That is why you now still call it Bormla. The oldest building near this area is a rock-hewn chapel near what is now called St Helen’s Gate. The origins of this chapel dedicated to Our Lady, go back to the Greek tradition of converting caves into small chapels. It is interesting to

note that at this time, the area around the tower was Christianised according to the Latin rite, while the slow Christianisation of the rest of the islands was more related to the Greek rite and saints.

In the 1240s, the small tower was enlarged to such an extent that it began to be called Castrum Maris (Castle by the Sea). Again, the turmoil over the southern half of Italy and Sicily led to the islands passing from the hands of the Hohenstaufen to the Angevins (French). At this time, the castle was manned by a total of about 150 Angevin soldiers under the command of a Castellan. The Castrum was a lonely beacon of defence in the harbour and this promontory became an increasingly important point of reference for the islands, as it was Malta’s gateway to the world. The administration of the country was firmly in foreign hands.

At the end of 1282, the Maltese Islands, with the exception of the Castrum, fell under the Aragonese crown as a result of the Sicilian Vespers.2 The King of Aragon was very generous in offering the Castellan and his men safe passage to the Angevin lands, but the offer was declined and although the islands were in Aragonese hands, the Castrum remained firmly in Angevin hands.

Let us venture further down the path of our journey to 8th July 1283. The Castrum witnessed one of the greatest naval battles ever fought in the Grand Harbour. This was when Roger of Lauria, the Sicilian admiral who commanded the

Battle of the Grand Harbour between the Aragonese and the Angevins

Battle of the Grand Harbour between the Aragonese and the Angevins

Aragonese fleet, attacked the Angevin fleet anchored just outside the Castrum. The battle began at sunrise and ended with sunset. The Angevins were soundly defeated with over 3,500 dead, including their commander Gulliermo Cornuto, and 860 prisoners. However, Lauria did not have the catapults and the siege equipment to storm the Castrum, so it remained under the Angevins. You need to remember that this was before the advent of gunpowder, so they had to rely on catapults to breach the high walls and on crossbows to wound the defenders. Eventually, the Castrum fell under the rule of the Aragonese, after two long years of battle.

The Castellan of the Castrum had jurisdiction over the castle and Birgu. The expenses for the maintenance of the castle were quite high, but justified by its defensive and strategic role for the islands. During this period, a difference emerged between the inhabitants of Mdina and those of the Castrum. The population of the Castrum consisted of royal officials, soldiers and merchants, whereas the inhabitants of Mdina were nobles who owned large tracts of land around Malta. The period was marked by constant quarrels between the administration of the Castrum and the leading families of Mdina, to the extent that the latter called the Viceroy in Sicily and accused the administration of the Castrum of being homini ignoranti oy sfrenati! (ignorant and inconsiderate). In reality, the Castrum’s officials kept the nobility in check and maintained a balance of power on the island. Until 1398, the Castrum functioned as a parish, since the appointment of the chaplain was a royal prerogative, and Birgu was at the same time a parish where the veneration of St Lawrence was subject to the local Curia.

Since the fate of the islands was linked to events in the Kingdom of Aragon, the death of King Martin II in 1410 brought the islands under the control of Ferdinand of Trastmara (1380-1416). With the death of King Ferdinand, the throne passed to his son Alfonso. The new king was involved in extensive wars which were an expensive affair. To finance them, in early 1421, he decided to pawn the Maltese Islands to one of his closest confidants, Don Gonsalvo Monroy, for the sum of 30,000 florins. Although this was a purely commercial transaction, to the Maltese, Monroy was nothing but a new feudal lord, for he was given sweeping and exclusive powers over taxation, civil and criminal jurisdiction, and the appointment of officials. In fact, Monroy acquired the islands with the intention of making a return on his investment. Yet his plans failed after a Moorish attack in 1423, which was also followed by a period of famine. In 1425, the Gozitans rebelled and the revolt

spread to Malta. In May 1427 Donna Costanza, Monroy’s wife, and their loyal servants had to seek safety within the Castrum. Chaos reigned on the islands and King Alfonso was ready to wage war against the rebels. The Maltese sent their representatives to find a reasonable agreement with the Viceroy in Sicily. With great difficulty, the Maltese managed to reach an agreement to pay 30,000 florins to Monroy in ransom for the islands. In the meantime, Donna Costanza retained control of the Castrum. The collection of the 20,000 florins required for the redemption was equally challenging, and finally Monroy pardoned the last remaining 10,000 florins on his deathbed in April 1429. He also decreed in his will that the 20,000 florins should be divided into two halves, one half for the islands and the other for King Alfonso. Still, there was no reason to rejoice, as in September 1429 the Maltese Islands were besieged by the Tunisian Moors taking over 3,500 people as slaves.

Another sad episode was the sack of Birgu in 1488. It was more obvious than ever that the frequency of raids was increasing as the situation around the Mediterranean became more volatile. The Castrum was reinforced with several round towers and its entrance was protected by a barbican wall armed with bombards and cannons. Ultimately, it served as a refuge for the inhabitants of the area during the frequent pirate attacks.

By mid-14th century, a small arsenal was operating in Birgu. The word ‘arsenal’ comes from ‘darsena’, which in turn comes from the Arabic word ‘daar senaa’. This might sound familiar to Maltese speakers, as in Maltese ‘dar is-sengħa’ which means ‘the house of crafts’. At that time, it was more about maintenance than actual shipbuilding. Towards the end of the 15th century, the arsenal had developed into a small shipbuilding facility. Around 1494, the arsenal was used to build a fusta3 for local corsairing activities on the Barbary coast. This enterprise was taken over by the local leading families, recorded through a signed deed before notary Giacomo Zabbara.

A dire situation reached the islands in 1523, just a few years before we, the Knights, arrived on the islands, when a plague-ridden galleon docked at Birgu. The Municipality of Mdina tried to contain the plague by burning the cargo and isolating the crew, but the plague spread through Birgu, so the only solution was to seal off Birgu until the plague subsided.

3. The fusta is a narrow, light and fast ship with shallow draft, powered by both oars and sails, similar to a galley. Launch of the fusta at the Birgu Arsenal

Launch of the fusta at the Birgu Arsenal

Followingthe Knights Hospitallers’ defeat against the Ottoman Empire in 1522, we had to leave Rhodes, the place that we had called home for more than 200 years. It was a hard and difficult time for us. The Order had to settle temporarily in Italy, until a suitable solution could be found. The Emperor was very generous when he offered us the Maltese archipelago and the Castle of Tripoli, on the periphery of his vast empire.

The news that the islands might be handed over to the Order spread like wildfire among the population. There were mixed feelings about this decision. Those who wielded power in some way were very disappointed at the idea of a new overlord residing on the island itself, as this would diminish any power they had. Contrastingly, there were others who were pleased to welcome the Order on the islands, particularly the seafarers or longshoremen as they knew that the Order’s fleet would be a boon for employment opportunities. Even those concerned for the protection of the islands were delighted, knowing that the Order would want to invest in the security of its new headquarters.

To investigate the islands, Grand Master L’Isle Adame appointed a Commission consisting of eight Knights, one from each langue of the Order. The Commissioners’ report was gloomy, emphasising the low quality of the soil and the inadequate defences of the islands. Their opinion of the Castrum was rather poor too, describing it as old, dilapidated and easily mined. Inside the castle there were 40 houses, wells and the Castellan’s house. The Commission also reported that the Castrum did not inspire fear and enemy raids were frequent on the islands. Given the aristocratic dominance in Europe and the ageing Grand Master L’Isle Adam, the Order had no choice but to accept the Maltese Islands, conveniently situated at a distance. However, to ensure our survival, Fra Diego Perez de Malfriere, one of our brethren from Portugal, visited the islands before the Grand Master with stonemasons, carpenters and blacksmiths, entrusted with the repairs of the existing fortifications. He even enlarged the Chapel of St Anne in the Castrum to better suit our needs.

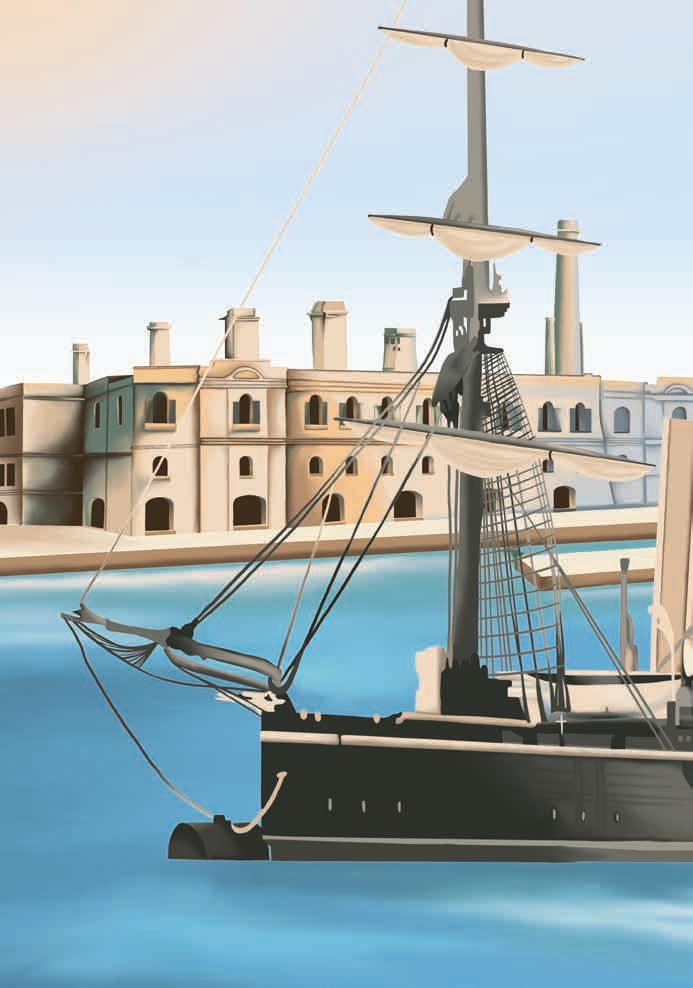

When the Order arrived on the islands on 26th October 1530, its fleet consisted of two large carracks, a number of galleys and transport ships. The inhabitants of Birgu flocked to the waterfront to witness the awe-inspiring scene unfolding before their eyes, with all the Knights, soldiers, sailors and the whole entourage disembarking. The Grand Master visited directly the Church of San Lorenzo a Mare, today known as St Lawrence’s Church. The first few weeks were rather hectic, as the sudden influx of people led to a shortage of accommodation, to say the least. This led to the first (and almost uninterrupted) building boom on the islands. The small village of sailors quickly became a bustling town. With the settlement of the Order in Birgu, the difference between the city and the hinterland became increasingly apparent. Birgu set out on the road to urbanisation and the development of a cosmopolitan society, a microcosm of the Mediterranean world, for the town had become home to people from all over the Mediterranean, including some 400 Rhodians who decided to follow the Order to the Maltese Islands. This community settled in Birgu and remained independent for a long time. The Italian language became the lingua franca4 for these people, unlike the inhabitants of the hinterland who spoke an Arabic dialect and hardly interacted with Birgu.

Less than a year after we settled on the island, a horrible tragedy occurred in the middle of Porto delle Galere. The old carrack Santa Maria was being used as a dormitory prison for children and female slaves, as well as a gunpowder magazine. A young boy decided to steal some gunpowder to play a wicked trick, when he accidentally set fire to the gunpowder on the carrack. The explosion flung the deck into the creek. There was a great commotion and fear that further explosions would cause extensive damage to the fleet, Fort St Angelo and Birgu. Meanwhile, the fire continued to rage and spread throughout the carrack. Quick action saved the situation when massive pieces of artillery were fired at the carrack to sink it in order to put out the fire. Eventually, the carrack sank along the shore of Isla near the Chapel of St Julian. The next day, L’Isle Adam ordered to search for and salvage any undamaged items. They managed to collect cannon, cannonballs and part of the treasure which was also stored on board.

The series of misfortunes continued with another tragedy on Easter Monday 1532, when the Church of San Lorenzo a Mare was destroyed by a fire caused by the Paschal Candle which was forgotten alight after the Sunday service. Among the items lost in the fire, there were church vestments donated by Grand Master D’Aubusson decades before, when the Order was still in Rhodes, and tapestries depicting the lives of St Catherine and St Mary Magdalene.

Isla as at the time of the Great Siege

Isla as at the time of the Great Siege

In the meantime, the Order began to dig a protective ditch, separating the Castrum from Birgu. This began to shape the city into the configuration you can still admire today. Fra Diego was entrusted with the construction of the Sacra Infermeria at Birgu – now used as the Monestary of Santa Scolastica – to fulfil the Order’s role as Hospitallers and the Castellania, the law courts. The next step was to build modest auberges for the different langues and to follow the tradition of Rhodes, that is for a whole area in the city to be reserved for the Order, known as Collachio.

The military engineer Antonio Ferramolino was brought to the islands to improve the defences. Birgu was surrounded by walls on the side facing the San Salvatore hill at Kalkara. The Castrum underwent a massive transformation and the De Homedes Bastion was built to protect the moat and the entrance. The limited space prevented Ferramolino from building a corresponding bastion on the opposite side. However, he did build the cavalier which provided the defenders with a raised gun platform and an excellent observation point spanning all the way to medieval Mdina. Work on the cavalier proceeded slowly and it was only finalised after seven years. These works ushered the medieval Castrum into the age of gunpowder. Unsurprisingly, the name ‘Castrum Maris’ was slowly abandoned in favour of a new name of Fort St Angelo, derived from the chapel dedicated to this saint, and by which you still know it today. Some minor works continued right until 1565, with a sea-level battery finished providentially in time for the onslaught of the Great Siege, which took place that year.

Grand Master L’Isle Adam built himself a second house on the sparsely built peninsula of San Giuliano, what you know today as Isla, opposite Birgu. The peninsula was named after the small chapel dedicated to San Giuliano, that stood and still stands to this day, although rebuilt in 1539, in the middle of the peninsula. Fra Juan de Homedes followed in the footsteps of his predecessor and built a villa with a garden. Unfortunately, both buildings later had to make way for residential development.

After the razzia of 1551, Fra Juan de Homedes began building a small fortress dedicated to St Michael on the peninsula of San Giuliano. Work on the walls began later, when the Grand Master was Fra Claude de La Sengle. To speed up the work, the material excavated for the moat was used to build the bastions. This was the basis for the new city, named Senglea, after the Grand Master himself. The walls were built on the side facing Corradino and it was through these walls that Birgu’s defences were strengthened.

On 23rd September 1555, a rare meteorological event caused havoc in Porto delle Galere when a tornado hit the islands, capsizing four galleys in the harbour and killing about 600 people. Our brethren and even Grand Master de La Sengle rushed to help in the rescue operations, for among those trapped were members of our Order. The rescuers could hear the trapped people trying to break open the hull to escape certain death. Among them was

Fort St Angelo just before the Great Siege of 1565

Fort St Angelo just before the Great Siege of 1565

Fra Mathurin d’Aux de Lescout, better known as Romegas. He was discovered after the rescuers heard a knock coming from the hull. After the wooden planks of the hull were prised open, it was Romegas’ small monkey which jumped out first, while its owner stood in shoulder-high water, thanks to an air pocket. As the sun rose higher in the sky, it became clear that unfortunately half of the dead were the slaves chained to the galley benches, unable to escape the ordeal.

When the Order settled in the city, an unsavoury business arose, namely prostitution. Shortly before the onslaught of 1565, Jean de Valette and the Council issued an order to deport both local and foreign prostitutes. Unfortunately, even some members of my Order maintained relations with prostitutes and concubines.

The aftermath of the tornado

The aftermath of the tornado

It was in the first days of spring 1565, when the Order’s spies received the news that the Turks were preparing to besiege the islands. This caused intense fear as the memory of the razzia of 1551 was still very fresh in everyone’s mind. One could sense the tension in every meeting of the Order’s Council. The older Knights were sure that the Ottomans’ aim was to finish what they had started with the Siege of Rhodes: the total destruction of the Order.

Grand Master Fra Jean de Valette was a veteran of sieges and battles. He knew he had to prepare the city as best he could without delay for the destined siege ahead. Arrangements included reinforcing the existing fortifications, preparing a great chain across the Porto delle Galere to close the entrance, and constructing a wooden palisade5 along the shoreline on the side of Isla.

In May, the Ottomans were sighted off the coast of the islands. De Valette had 6,100 men at his disposal, 4,000 of whom belonged to the local militia. There were also 500 men from Birgu and 300 from Bormla. When the dreaded Ottomans finally arrived, they landed at Marsaxlokk. The Council thought that Birgu would be their target, but fortunately for the Order and the rest of the islands, it turned out that they targeted Fort St Elmo first. The Order was thus able to further strengthen the fortifications of Isla and Birgu, while in the meantime provided logistical and medical support to Fort St Elmo.

On 21st May 1565, just three days after landing on the islands, the Ottomans set up camp on Santa Margherita Hill, opposite Birgu. This demonstrated their strength and they hoped to intimidate the Order and the locals. On 25th May, it became clear that the real target was Fort St Elmo. The wise De Valette had all the women, children and old men who had taken refuge in the fort evacuated, and supported the defenders by sending 100 Knights. On the 27th May, the Ottomans began bombarding the fort. Captain Miranda, a Spanish soldier who eventually died at Fort St Elmo, reported that the longer the fort held out, the greater the islands’ chance of surviving the attack. De Valette sent more soldiers to assist the defenders while the wounded were

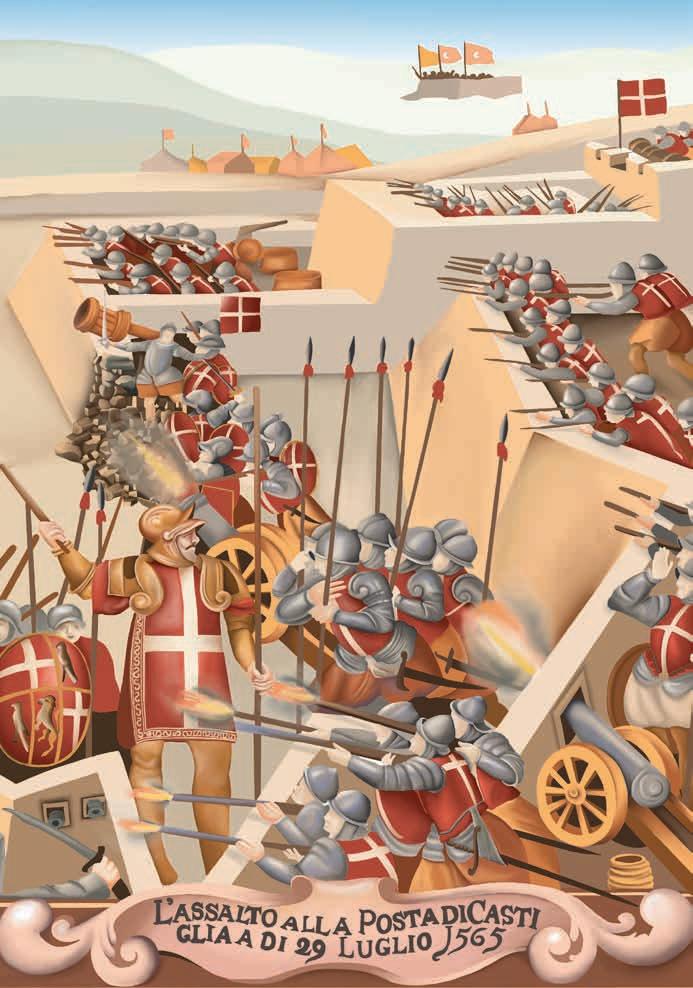

5. A palisade is a fence of wooden stakes, in this case fixed into the seabed, for defence.taken back to Birgu. With great effort, the Order continued to supply Fort St Elmo with reinforcements, ammunition and provisions. On 19th June, things took a turn for the worse as tragedy struck at Fort St Angelo, when a powder mill exploded and eight men lost their lives. The next day, the Turks erected a battery to prevent further reinforcements from reaching Fort St Elmo. On 23rd June, the defenders of Fort St Elmo were completely overwhelmed. More than 1,500 men died defending the fort. This meant that the enemy’s next objective would be Birgu and Isla. And sure enough, on 27th June, the post of Sanoguera at the far end of the Isla peninsula was bombed.

The Grand Master ordered the destruction of the buildings in Bormla and for all the woodwork to be brought back to Birgu to reuse the scarce timber. On 30th June, the good news finally arrived that the much anticipated albeit small relief force had landed on the island. On 3rd July, under cover of darkness, these brave men managed to reach Kalkara and cross over to Birgu unnoticed on boats, just in time, since three days later the Ottomans began shelling Fort St Michael in Isla with heavy guns. Meanwhile, the dreaded Ottomans were bringing boats overland from Marsamxett to Marsa. De Valette suspected what the Ottomans were up to, so he closed Galley Creek using the great chain. In the meantime, the Turks built a battery on Salvatore Hill at Kalkara, surrounding Birgu even more. Our shrewd Grand Master ordered the further reinforcement of the palisade at French Creek. The Ottomans continued to bombard both Isla and Birgu incessantly, day and night, before launching a

physical attack. Thankfully, an important decision was taken by the Order to build a pontoon with boats to allow the transfer of troops between the two fortified cities.

On 15th July, 100 enemy boats were assembled at Marsa, with about 3,000 Ottomans to attack Isla and Birgu from different directions. A group of 10 boats tried to attack the chain that closed the Porto Delle Galere, but to their detriment, they had not noticed the Battery of de Guiral partially hidden at sea-level. When our guns fired, they blasted the enemy to death. By the end of the day, over 4,000 Ottomans had fallen, whereas our losses were about 200 men. The following days were critical as the Ottomans stormed the walls of Isla and Birgu. They began to build a bridge over the span of the ditch close to Fort St Michael. The brave defenders tried their best to destroy it. They failed with their first attempt, but succeeded with their second the following day. After this failure, the Ottomans turned their attention to Birgu to bombard the post of Castile facing Kalkara.

De Valette’s strategy was based on providing enough men on the bastions, while keeping reserve soldiers in the square of Birgu. During the onslaught, men were sent into battle as needed. The bridge of boats between Isla and Birgu provided the all important access between the two cities. Between 22nd and 26th July, the Ottomans continued bombarding both Isla and Birgu. Piali Pasha, the Admiral of the Turkish Fleet, eventually concentrated fire on the post of Castile, so that he could send his soldiers to storm the walls, but they faced a stout defence and had to retreat.

On 7th August, the Ottomans attacked again Birgu and Isla simultaneously with thousands of troops, hoping to get through a breach and split the reserve forces. The situation was becoming desperate for us and Jean de Valette tried to defend the post of Castile. A turning point took place when the cavalry from Mdina attacked the Ottoman camp at Marsa. The Ottomans mistook this attack for the arrival of another relief force and stopped their assault.

During the following days, the battles continued, but the fighting spirit of the Ottomans was breaking down as every attack was neutralised by the defenders. By mid-August, military supplies were running extremely low and discontent was spreading. Nevertheless, the Ottomans continued to attack Birgu and Isla, while the post of Castile was overrun. The 70-yearold Jean de Valette valiantly fought with sword in hand together with his soldiers. His presence was like that of a thousand men, but this meant

Opposite: Grand Master Jean de Valette leading the troops during the assault on the Post of Castile

that Fort St Michael in Isla had to resist on its own force unaided. By the evening, the Ottomans retreated. Fortune favoured the Order when the Tramontana wind brought rain, so all firearms were made redundant. This frustrated the Ottomans even more because the rain rendered even their bows useless, while de Valette’s men could still use their more powerful crossbows.

So the Ottomans changed their strategy. They built a manta6 but the Knights, sensing their approach, prepared hidden cannon, ready to fire at the right moment. A few days later, the Ottomans tried to attack the walls once more with a moveable tower, but again, the Knights using the same guns, blew the enemy’s tower to smithereens.

The Turkish assault tower

The Turkish assault tower

Although the attacks continued, news of a relief force meant that the Ottomans had to lift the siege. On 6th September, the Ottomans fired their cannon for the last time. This time, the target was not the fortification walls but the houses. Two days later, the relief force landed in Mellieħa. The Ottomans withdrew from the islands to the sound of church bells peeling as a sign of victory.

Once the siege ended, a complex situation developed. On the one hand, the harbour, Birgu, Bormla and Isla had all suffered considerable damages. On the other hand, the Order’s Council took a very important decision: to found a new and better fortified city on the Sceberras peninsula. However, although a priority, this enormous task required lengthy works. So, while the new city fortress was launched, renovation works of damaged fortifications were also undertaken as the fear of another siege was believed to be imminent.

Withthe Great Siege done and dusted, let us now explore other Cottonera events. I must admit there is so much to discuss, yet so little time!

Following the Great Siege, ordinary life on the islands started to take shape. The Office of the Roman Inquisition was established in 1561, as part of the counter reforms against Protestantism. So the first Inquisitor on the Maltese Islands was the Bishop himself, Mons Domenico Cubelles (1561-66), a former chaplain of our Order, with the episcopal palace becoming a courtroom. After his death, the Office was handed over to his successor, Fra Martin Royas (157277), who however, was at odds with the Grand Master Fra Jean de la Cassière (1502-1581). Pope Gregory XIII (1502-1585) had to intervene because of the constant squabbles between them. He solved the problem once and for all by appointing an apostolic delegate to take on the role of inquisitor, or so he hoped, entrusting the task to Mons Pietro Dusina (1574-75).

On Dusina’s arrival, the old Castellania of Birgu was placed at his disposal. The building served as his residence, court and prison. Although Dusina’s tenure was short, he left a lasting impression with his apostolic tour of the islands and report on the state of local churches and clergy. The Vatican Commission gave the inquisitors absolute power to take action against anyone who broke

the Catholic faith. I deeply regret that even some of my brethren indulged in forbidden activities, including sorcery, violations of abstinence, heresy and blasphemy ... just to name a few.

The inquisitor’s sentences ranged from silence to public condemnation. No one was above the law and even prominent citizens were brought before the inquisitor. For example, Notary Giuseppe de Guevera, first before Royas and later before Dusina, was accused of heresy, of keeping a concubine and frequenting prostitutes. He was found guilty and was thus obliged to wear a yellow habit with a red cross, spend three years in prison and pay a fine of 50 scudi. Then there was Fra Fabrizio Lascari, a Provençal knight, accused of heresy and possession of forbidden books. He was sentenced to abjure in public – that is to renounce past transgressions publicly – to fast every Friday, to recite the seven Psalms weekly, to confess, and to receive Holy Communion monthly for a year. Another case was that of Fra Giovanni Batta Maurizzi, a galley captain who gave refuge to three Greeks persecuted by the Inquisition. Maurizzi was also sentenced a hefty fine of 500 scudi.

Over the next 200 years, the Palace of the Inquisitors was modified, enlarged and embellished to meet the needs of the residing inquisitors. It is a building full of contrasts: the elegant, symmetrical façade contrasts with the labyrinthine layout of the interior.

As the population of Isla grew, a new church was built and the town was bestowed the title of parish, dedicated to Our Lady of Victories in memory of the Great Siege victory. The construction of the new church was entrusted to Vittorio Cassar, Gerolamo’s son. In 1586, the inhabitants of Bormla, not wanting to be outdone by their neighbours, obtained full religious autonomy from Birgu, as they faced a problem with the gates of Birgu being closed at night.

Finally, I would like to tell you about the oldest parish in Birgu, that of San Lorenzo a Mare. Its origins date back to the Middle Ages. The locals claim that it was founded by Count Roger himself when he conquered the islands. I will not dispute this claim, but I can confirm that the devotion for San Lorenzo was strengthened when the islands passed into the hands of the Aragonese, from where the Saint is known to have originated. After the arrival of the Order on the island, we used the church as a Conventual Church, until the one dedicated to St John the Baptist in Valletta was completed. Just at the end of my reign, a local architect was commissioned to design a new church for Birgu. This magnificent church replaced the older one. The outstanding façade was further embellished when a bell tower was built later on in the early 18th century, while another bell tower was added on the right side in the 20th century to give symmetry to the façade.

After repairs were carried out at the end of the Great Siege, Fort St Angelo remained unchanged for more than a century. In 1689, Don Carlos de Grunenberg, a Spanish military engineer, offered to personally finance the works to be carried out to strengthen the fort and provide better protection for the Grand Habour. The Order’s Council could not refuse such a generous offer and so Fort St Angelo was given its present appearance.

The 18th century began with the disastrous loss of two galleys. I followed the event with great sadness, for it marked the beginning of the decline of a long tradition. Grand Master Fra Ramon Perellos asked the Pope for permission to raise a squadron of ships of the line or vessels. These warships were heavily armed and could sail even in winter. Since the local boatbuilders did not have the knowledge to build this new type of fighting vessel, the first two were commissioned from Toulon, France. Perellos encouraged French master craftsmen to work on the islands. Their legacy survived by teaching the local boatbuilders, acquiring the technical and mathematical knowledge, as well as the language. New workshops and warehouses were built along the Bormla waterfront in the inner part of Porto delle Galere to serve the new vessels.

The streets of these cities provide us with colourful narratives, including stories of saints and sinners. I remember one of the stories very well because it happened during my reign in 1665. A gang of robbers targeted people in Isla and Birgu. One of the victims shot one of the gang members at close range, but missed, earning the reputation that the gang consisted of ghouls.

The year 1718 was marked by a prolonged drought. So Bishop Joaquin Canaves issued a decree for a penitential pilgrimage with the statue of the Bambina7 from the Sanctuary of Tal-Ħlas in Qormi to Our Lady of Victories in Isla. All the confraternities of the island had to take part in this votive procession held on 10th April. Miraculously, on their way back, it began to rain heavily.

Another interesting story is that of Giorgio Carli, a 17-year-old sailor who had a habit of visiting Margharita Virau’s brothel in Strada dei Francesi in Isla. To make matters worse, Giorgio spent his father’s money in the brothel and rather than keeping a low profile, he got into trouble with one of the officers of the law and with prostitutes.

Earlier, I already mentioned the 1675 plague which hit the island. I can assure you that it left indelible marks on everyone, especially us Hospitallers, as it risked wiping us all out. The quarantine regulations were taken extremely seriously and anyone caught breaking them was severely punished. In the port of Isla, it was taken a step further, whosoever broke any of the rules was executed. The culprits were given an opportunity to confess their sins, then receive Holy Communion and finally, they were hung from the gallows.

One of the popular characteristics of Cottonera was, and still is, the Holy Easter celebrations with processions on Good Friday. Birgu even retained its Spanish influence through the statues which are not only made of wood or papier-mâché, but also richly dressed in velvet and silk, embroidered in gold, as can still be seen in Spanish countries as well. Easter celebrations reach their peak when the statues of the Risen Christ are carried through the cities and in some instances even run with the statues which, as you know, is also still done to this day.

The last decades of the 18th century were marked by the decline and decay of the once fearsome Order. The situation in 1798 was dramatic. My once glorious Order was but a ghost of its former self. Some of my brethren even conspired against their brethren. On 6th June 1798, French frigates entered the harbour for fresh water and supplies. Just three days later, the French Armada was sighted off the islands.

The reigning Grand Master Fra Ferdinand von Hompesch was a diplomat but sadly not a warrior. The defence of the Cottonera was entrusted to some of his most trusted brethren. De Gournau, a major in the Grand Master’s bodyguard, was assigned with the security of Fort St Angelo, Charles de Gandrecourt with

7. The Basilica of Isla is dedicated to the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary a.k.a Maria Bambina.Birgu, Anniable de Subiras as captain-general of the galleys of Bormla and Bali Suffren de St Tropez with Isla. Bali Toussaint de la Tour du Pin manned the defence of the Cottonera Lines with the help of the militia and soldiers, as well as sailors of the navy. Yet, the situation was critical. Bali de la Tour du Pin did his utmost to transport gunpowder from the stores in Cottonera to Valletta, in preparation for the onslaught.

The Maltese became very suspicious of the French Knights. They mistakenly believed that most of them were supporters of the French Republic. The situation developed dramatically and some angry locals turned on some of my brethren, such as Valin who fell under a rain of blows, and Perier was thrown down from the bastions. At Isla, Bali de Suffren was on the verge of desertion, ending with just a handful of men who remained with him. He eventually abandoned his post and went to Valletta to report on the situation. It is with great mortification that I must once again state that the fighting strength of the Order was completely dead. Hompesch had no choice under these circumstances but to seek for a truce. The Order surrendered the islands after 268 years. The Order’s surrender was called a convention. At noon on 12th June 1798, Cottonera was handed over to the French Republican soldiers.

This brought about a number of changes for the people of the islands. The French organised the government into municipalities with Cottonera falling under one unit, the Eastern Municipality whose president was the famous Maltese shipbuilder, Giuseppe Maurin. Other leading citizens joined the new government. On 10th August, François Roux, the Secretary of the Eastern Municipality, gave a speech in the main square of Birgu, where the Tree of Liberty was erected. This became a regular event on various anniversaries. However, at the same time, discontent was spreading through the towns. Writings were put up on the door of a shop near the Discalced Carmelites’ Church in Bormla with a list of men who were being considered as traitors. Francesco Pisani, a chemist from Isla and Dr Adriano Bezzina were accused of conspiring against the French government. During the criminal proceedings, a list of names emerged that included even members of the Eastern Municipality. Although they were eventually found not guilty, they still spent some time in prison.

News that the country was rebelling against the French

Tree of Liberty

Tree of Liberty

masters spread like wildfire. On 21st September 1798, a unit of 700 French soldiers from Cottonera attacked a Maltese post at Corradino, but when reinforcements arrived, they rushed back behind the safety of the Cottonera walls. They also discovered that the Maltese were stepping up their blockade efforts. In the first days of October, the French attempted to storm Żabbar, but when they ventured into the village, they were soundly beaten by the villagers who used the narrow, winding streets and buildings to their advantage. In December, the Maltese bombed Cottonera. People abandoned their homes and took refuge in churches and convents. Faced with this situation, General Vaubois allowed the citizens to leave the cities.

Matters became more and more desperate when a cannonball from Tarxien hit the Church of St Philip Neri and terrified everyone who had sought refuge within. The regular bombardment caused damage to houses in Cottonera. One of the tragedies in Isla concerned the death of Michele Caruana who had left his home to live in the monastery of St Philip. His house was hit by a cannonball and he rushed inside to fetch something, when the balustrade crumbled down and part of the masonry fell onto him. Injured, he managed to crawl back into the oratory where he died. British support for the insurgents caused further concerns in the cities as they set off firebombs causing more panic. When a group of men were caught conspiring against the French in Valletta, the situation turned critical. The French became increasingly ruthless and when a sword was found in the household of someone named Francesco Pisani, he was summarily executed.

Tensions were high, especially when the French asked to enter the Monastery of Santa Margherita. Their request was accepted by the bishop to avoid compromising the situation further. The Discalced Carmelites had to cede part of their convent to the French. All attempts by the French garrison outside the walls of Cottonera failed, and when the situation came to a head, the Oratorians of St Philip were even expelled from their building to make room for French soldiers. However, with some lobbying (and a sum of money) they managed to secure the convent.

By the summer of 1800, it was obvious that the end of the French rule was imminent. The blockade was finally taking its toll on the French. Food and water were depleted and disease was spreading. Vaubois had no choice but to surrender to the British. The Maltese were excluded from the negotiations for fear of retaliation and the locals were not allowed to re-enter the cities of Cottonera and Valletta until the French had left the islands. Nevertheless, the remaining inhabitants of Cottonera were allowed to leave their homes to meet their relatives outside the walls. This closed another chapter, ushering in a new one.

Here,I would like to take a moment to discuss some of the changes the cities’ fortification went through over time. The hill of Santa Margherita in Bormla was used by the Ottomans during the Great Siege to shell both Isla and Birgu. This highlighted the inherent weakness of the Birgu and Isla land fronts. However, this issue faded into the background, as the focus turned to the completion of the new city of Valletta. But as soon as these works were finished, attention turned back to the Cottonera area. The first proposal came from architect Pietro Paolo Floriani, but the Order was not convinced and sought a new design. Eventually, military engineer Fra Vincenzo Maculano da Firenzuola (1578-1667) was chosen to design the walls. He was a colourful character and had trained as a mason before joining the Dominican Order. When he was appointed inquisitor, he was required to investigate Galileo Galilei8 (1564-1643), a renowned Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer. The papacy had entrusted Vincenzo Maculano with a major programme to strengthen the defence of Rome. This made him the perfect candidate with knowledgable experience for this extensive project. On 30th December 1638, Grand Master Fra Giovanni Paola Lascaris laid the foundation stone for a defensive line around the hill of Santa Margherita. However, work progressed so slowly that by the time I was elected Grand Master, only the central bastions were finished, with no curtain walls connecting them to the land fronts. So I was tasked to ensure their completion, naming them after the saint who had been patron of the hill.

As you have seen throughout the history so far, corsairing was widespread in the Mediterranean, especially on enemy vessels. Thus, when we captured the Gran Sultana in 1645, the Ottomans launched a massive attack on the island of Crete, the last standing territory in Venetian hands at the time. This opened the theatre for the Cretan war (1645-1669). By

1648, the only remaining fortress on the island in Venetian hands was the city of Candia. Venice managed to hold the city thanks to its naval power. However, the tides of war turned against them when a Venetian military engineer defected to the Ottomans, and the French vice-flagship was lost. We did our best to help the Venetians, but our limited resources, could not turn the fortunes of war. On 27th September 1669, the inevitable happened when Venice surrendered to the Ottomans. This caused a panic on the island of Malta as the memories of the Great Siege were still seared in everyone’s minds. I was sure that if the Ottomans attacked, they would want to finish what they failed to do in 1565.

Antonio Maurizio Valperga (c.1605-1688) was the engineer commissioned to design the Cottonera Lines. Although, Firenzuola’s Santa Margherita Lines, were far from ready, I diverted all resources to work on the Cottonera Lines. Valperga proposed a 9km-long line of bastions surrounding the hills of Santa Margherita and San Salvatore, connecting the extreme ends of the walls of Birgu and Isla.

Such a project required a huge amount of money which had to be levied through taxes. Not everyone understood the need or urgency of this important project for our security, causing me innumerable problems. Apart from the inhabitants, even the clergy did not want to pay the taxes to raise the necessary funds. They tried to involve His Holiness to avoid paying them. Even the Inquisitor became involved in the matter. Another problem arose from the expropriation of the land for the project. Domenico Bonnici, a man whose mission in life was to fight us, claimed that his expropriated garden was valued at 15,000 scudi, which my officials had valued at 6,000 scudi. He even dared to ask the Inquisitor to intervene. But the diplomatic Inquisitor eventually realised that Bonnici was a troublemaker.

When I passed away, regretfully, the construction of these walls consumed a huge sum of money, so my successor Gregorio Carafa halted the works, only to be resumed in the 18th century, when another invasion threatened again the islands. However, these walls became the bond that linked the Three Cities together, forever forged with their name, Cottonera Lines, after me!

View of the fortifications of the Three Cities Margherita Lines (Inner) Cottonera Lines (Outer)

ISLA LAND FRONT

ISLA

FRENCH CREEK

PORTO DELLE GALERE (GALLEY CREEK)

FORT ST ANGELO

CORRADINO HEIGHTS

VALPERGA BASTION

View of the fortifications of the Three Cities Margherita Lines (Inner) Cottonera Lines (Outer)

ISLA LAND FRONT

ISLA

FRENCH CREEK

PORTO DELLE GALERE (GALLEY CREEK)

FORT ST ANGELO

CORRADINO HEIGHTS

VALPERGA BASTION

KALKARA CREEK

BIRGU

BIRGU LAND FRONT

FIRENZUOLA BASTION

BORMLA

BIEB IS-SULTAN

After the cities’ walls, let us now explore the gates. I will show you four of these gates which still survive today: the Couvre Porte of Birgu, St Anne’s Gate of Isla, St Helen’s Gate of Bormla and the Porta Della Maria Vergine Delle Grazie (a.k.a Notre Dame Gate or Bieb is-Sultan) of the Cottonera Lines. In addition, there are other gates and a sallyport which lead into the cities.

Birgu, originally, had four gates. Porta Marina, was destroyed in an explosion in 1806, but the other three gates still exist and are nowadays part of an intricate complex leading to Birgu. The first gate is the Advanced Gate also known as the Porte D’Aragon and is located on the west side of the counterguard. The second is Couvre Porte, which leads to the inner part of St John’s Bastion, and finally the third, Gate of Provence which stands on the inner flank of the bastion. This arrangement made it extremely difficult for the enemy to attack the main city gate, which was normally considered the weakest part of any fortifications.

The present gate of Isla was built at the beginning of the 18th century, when the bastion that housed the wooden sheer crane, called Maċina, was rebuilt to mast and unmast vessels. The Main Gate was located between the Maċina and Fort St Michael. Unlike the other gates, this one is rather unimposing and less decorated.

Brigu landfront featuring the Couvre Porte complex with the three gates illustrated in colour coding: first gate is the Porte d’Aragon, the middle gate is Couvre Porte and the last one is the Gate of Provence.

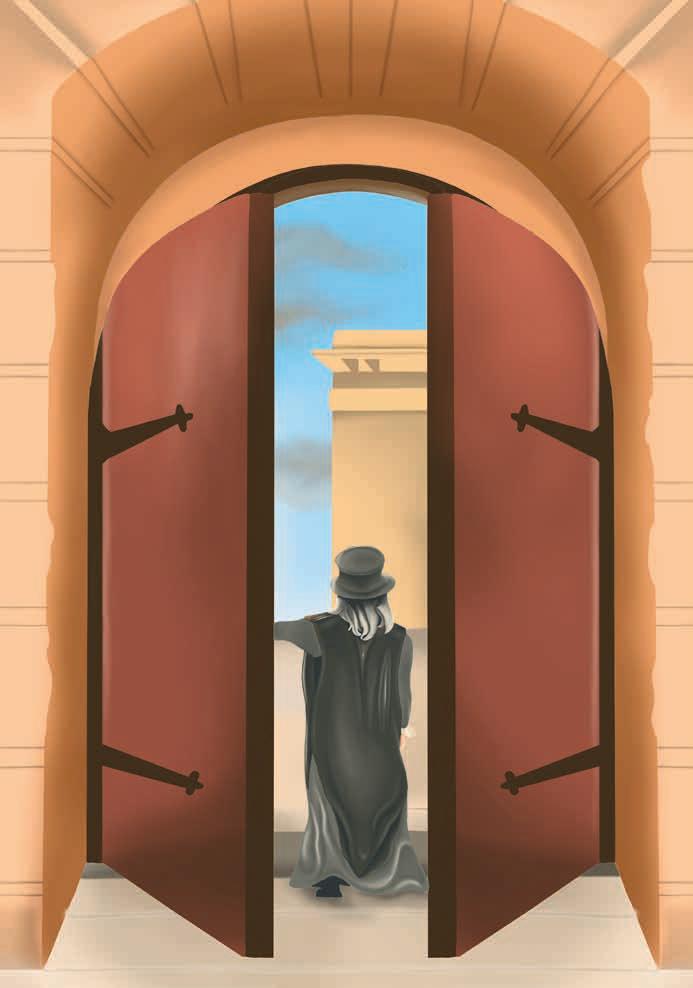

Opposite: Santa Maria Delle Grazie Gate popularly known as ‘Bieb is-Sultan’

Opposite: Santa Maria Delle Grazie Gate popularly known as ‘Bieb is-Sultan’

The monumental gate of Bormla was designed by Charles François de Mondion (1681-1733). It is known by two names: Porta di Sant’Elena or Porta dei Mortari. I must admit that it is a majestic gate, a worthy portal leading into the city. An inscription on it says its story; that the lines were designed by Cardinal Firenzuola, started by Grand Master Lascaris but then interrupted to build the Cottonera Lines, continued by Grand Masters Perellos and Zondadari, and finally completed by Grand Master De Vilhena in 1736 ... although unbelievably a century later! I had the pleasure of meeting all these personalities in my lifetime when they joined the Order.

However, the most important gate of the Cottonera Lines faces the nearest village, Żabbar. It is known as Porta della Maria Vergine delle Grazie, named after Our Lady at Grace’s Sanctuary of the village Parish Church. It is located on the highest point of the Cottonera Lines, thus offering an impressive view of the east coast of Malta. Originally, the gate was protected by a moat and a tenaille8 so that the enemy could not attack it directly. The gate itself is massive, impressively decorated, if I may say so, with Corinthian pilasters, has a trophy of arms and a bronze bust of myself in the centre. This gave the gate its other name of ‘Bieb is-Sultan’, meaning the King’s Gate. The inscription on the gate is an elegy to me, with a note to remind the people of my efforts to make the islands safer for years to come. Years later, I learned that someone had spread a rumour that my bust showed the location of a hidden treasure...all false!

Nowwe move to another chapter of the Maltese history, that of the new British masters who were not sure whether to keep the islands at first. But as the situation in Europe was quite unstable, so Malta remained under British control. As war raged in Europe, the islands became an important British logistical base, leading to a most devestating tragedy that occurred in Malta in peacetime: the Polversita Explosion of 1806. It was a hot summer’s day and as a spirit I was enjoying wandering unnoticed through the bustling streets of Bormla. Trade was in full swing and while war continued on the continent, the islands served as a strategic trading and military base. The British forces were preparing artillery shells to be shipped to Sicily. The disastrous explosion occurred when a bombardier used a metal chisel to remove the fuses from the shells, causing 40,000 pounds of gunpowder to explode. Apart from British and Maltese soldiers, over 200 civilians were killed and another 100 were injured by falling debris. Houses, shops and parts of the fortifications were destroyed. The area was nicknamed ‘L-Imġarrafa’ meaning wrecked.

A few years after this explosion, the dreaded plague reached the Maltese Islands again. The Three Cities were not particularly badly affected: Birgu recorded 33 deaths, Bormla 12 and Isla none. The inhabitants of Isla promptly coined the following rhyme:

Tal-Belt l-irvinati, Tal-Birgu l-impestati

Ta’ Bormla l-attakkati u Tal-Isla illiberati

This translates to: the inhabitants of Valletta were ruined, those of Birgu plagued, of Bormla attacked, while those of Isla were freed (meaning unscathed by the ravages of the disease). The people of Isla who had been spared the plague, erected a statue of Our Lady in the main street of their town. They also promised to hold a

The statue erected in Isla after the city was spared from the plague of 1813perpetual annual procession with the statue of the Bambina on 8th September, a tradition still held dearly to these days.

As I breeze through the history of these Three Cities, one particular year stands out: 1837. A year to remember for a series of events that occurred within a few months. It all began with the execution of Private Thomas McSweeney, an Irish Catholic serving on HMS Rodney His tragic ordeal started when his Protestant superior reported that McSweeney was offdeck9. During the argument, McSweeney lost his temper and pushed his superior, who fell to the main deck of the ship, hit his head and died a few days later. Although this incident took place in Barcelona, McSweeney was court-martialled on the Maltese Islands, being the headquarters of the Mediterranean Fleet. The court martial took place on HMS Revenge, which was anchored in the Grand Harbour. Even though no witnesses accused McSweeney and he showed remorse, he was still found guilty and was sentenced to death by hanging. The sentence was to be carried out on the ship he served, the HMS Rodney, which was ordered to sail to Malta. The ship arrived on 5th June 1837, dropping anchor in the middle of the Grand Harbour. Royal Navy ships anchored in the vicinity were manoeuvred around the HMS Rodney. Early in the morning, McSweeney was transferred to his ship by HMS Ceylon. Large crowds gathered at the city walls of the three towns to witness the execution. At six o’clock, McSweeney was hanged by the yardarm and was left hanging for half an hour, until he was taken to the Salvator Chapel at Bighi, Kalkara. He was then buried in the Vittoriosa cemetery since he was a Catholic. Legend has it that his spirit still lingers at his well-kept grave, but I have never met him so far.

Just a few days after the execution, a cholera epidemic broke-out on the islands. The British Governor at the time, Lieutentant-General Sir Henry Bouverie (18361843), instructed the Bishop that the Convent of St Philip Neri in Isla was to serve as a hospital. This meant that the sacred objects and furnishings had to be removed. On 5th July, the government also ordered the evacuation of the church to convert it into a hospital as well. This outraged locals who refused to leave the church. Some hotheads stormed the church tower and rang the bells. Eventually, a member of the Order of Oratorians managed to convince the people to leave and close the church. In the afternoon, the police surrounded the church and the Principal Intendent of the Police instructed the Oratorians that the church had been taken over on the orders of the Bishop and not the Governor ... pff ... an outright lie in my opinion! So the church was stripped of all its furnishings and used as a hospital until early September, admitting 685 patients, of whom 350 died, 329 recovered and 6 were transferred to the Sacra Infermeria in Valletta.

Just when the cholera epidemic was being contained, a sacrilegious crime took place. Someone secretely entered the Church of St Theresa in Bormla after nightfall and stole a chalice. A few days later, some boys playing in the ditch under the first gate of the Couvre Porte in Birgu, found the chalice hidden in a rock crevice. The Order of the Discalced Carmelites built a tiny chapel on this site in reparation. The perpetrator was caught in no time and sentenced to life in prison for his crime. Even today, the area is known as ‘Fejn sabu s-Sinjur’ meaning the place where they found the Lord.

It was a sad day in the history of Birgu when the galley arsenal was demolished. Even sadder when I remember all the galleys of the Order launched out of there. Over 400 years of history were erased to make way for a new building which included a clock tower, rivalling the one in the town’s main square. The building was a Naval Bakery to supply bread and biscuits to the Mediterranean Fleet. In its heyday, the bakery produced 17,500 rotoli of bread and biscuits a day, equivalent to 14,000 kilos. We could have used a bakery like that during my time!

William Scamp (1801-1872), the same architect responsible for the Naval Bakery, was also in charge of a project that forever marked the inner part of the Porto delle Galere. The area was known to the locals as ‘Is-Suq’ because of the marketplace there. However, the Admiralty needed the place as the best location for a new type of dock – the dry dock – ideal for the new iron monstrosity vessels which were then being built to replace the wooden ships that had been around since the dawn of mankind. On 28th June 1844, the foundation stone was laid with great pomp. A cofferdam9 was driven into the rock to keep the seawater out of the harbour basin until completion. After four years of hard work, the dock was completed. The first Royal Navy ship to be refitted in the new dock was HMS Antelope. In addition to the mast for the sails, it also had strange paddles on the side to assist propulsion. The age of sails was slowly coming to an end and was being replaced by the age of steam. The harbour basin

transformed Bormla from a town of fishermen, boatmen and craftsmen into an industrial place, ushering in a new era. While the people around the islands were mainly engaged in agriculture, those of the Cottenera area worked in the shipyard and the naval forces.

For almost half a century, the inhabitants of Cottonera welcomed a massive ship of the line, HMS Hibernia, to the Porto delle Galere. This ship’s association with the islands started at the beginning of the century, when the HMS Hibernia became the flagship of the Mediterranean Fleet at the end of the Napoleonic Wars. In 1855, she became the flagship of the Royal Navy’s base in Malta and remained so until 1902. The locals quickly forged the expression “qisek l-arbanja”, a corruption of the name meaning “you look like the Hibernia”, usually used to insult someone as being ‘big’ and cumbersome.

The exigencies of military and naval forces were to continue shaping my beloved cities. The Santa Margherita Lines were transformed into a veritable fortress called Fort Verdala. This fort was connected to the Cottonera Lines by the St Clement’s Retrenchment, thus dividing the Cottonera into two sides. In my humble opinion, the military value of these installations was questionable in that they were mainly used as barracks and later as prison camps for foreign soldiers.

Yet, I admire that the British took the health of their garrison very seriously and to cater for the regiments stationed in the Cottonera district, a hospital was set up in the old armoury in Birgu. As space was limited, some houses were also rented for the purpose. Around 1870, it became clear that a new hospital was needed. The site chosen was near the Santa Maria Delle Grazie Gate, far from the main residential areas. As a Hospitaller, I was very interested in this development. I was impressed with the airy sickrooms and the veranda that offered protection from the sun and rain, while the air could still circulate freely.

However, work in the shipyard depended on the requirements of the Admiralty. So when the Mediterranean Fleet was away, most of the dockyard workers became unemployed, which was a far cry from our times when those employed at the Arsenal always had regular work. When the situation became critical, the Admiralty decided to build a warship in the newly built Dock No. 3. The aim of this project was to fully utilise the workforce while the Mediterranean Fleet was away. This warship was different from the ships I had served on in my youth. It was an ironclad sloop, built with an iron keel, frames, stem and sternposts, with wooden planking. It was powered by a steam engine, but it still had three

9. Cofferdam: A watertight enclosure which has been pumped dry of seawater to allow the construction and repair of ships.masts for the sails. It was built at a time when the steam engine was replacing the use of sails. Work began in 1883, but progressed slowly as labourers worked on its construction only when the Mediterranean Fleet was away. The warship was launched in 1888 and named HMS Melita in honour of the islands. Its launch was attended by a member of the British Royal family, Princess Victoria Melita, who incidentally was born in the Palace of San Antonio built by one of my predecessors, Fra Antoine de Paule. The warship served in the Royal Navy for over 50 years, but the most interesting story I observed about this ship was not its participation in battle, but the invention of a tiny contraption. The second-in-command of HMS Melita, Lieutenant Edward Inglefield, invented clips for attaching signalling flags. The first prototypes of these clips were made by Maltese craftsmen in the Malta Dockyard. By 1895, Inglefield clips had become standard equipment for the British Royal Navy and remain so to this day.

As the warships grew in size, new docks and facilities were built at the French Creek. This development also involved the demolishing of Porta Haynduili, the name derived from the area called Għajn Dwieli, and Valperga Bastion. Instead of the magnificent gate designed by architect Mederico Blondel des Croisettes (1628-1698), a dark tunnel under St Paul’s Bastion became the main entrance to these magnificent towns.

Events on the islands were linked to those in Europe and beyond, and when the Great War broke out, the dockyard became the island’s largest employer. Men were employed to service the behemoths of the Royal Navy, but once hostilities were over, many men were made redundant, causing great discontent among the population. When the words ‘Culhat Al Belt’, meaning all to the City (Valletta), were written on the walls of the dockyard, it was a sign that major discontent had spread. I grieved when a youth from Vittoriosa died in the British fire during the riots.

And finally, the last nail in the coffin that marked the end of the age of sails came in 1927, when the balomba sounded to announce the removal of the iron sheer at the Maċina in Isla. Many people flocked to witness this unique event. The work began with the removal of the rear support, followed by the removal of the bolts at the ends of the hinges. The frame plunged into the sea, breaking and causing a wave that splashed the close bystanders, as if in revenge to its demise.

Theechoes of the Great War were still reverberating when frightening rumours of a new conflict spread throughout Europe. As the tides of a second war drew nearer, the islands slowly prepared for the onslaught. The shipyard immediately issued a memorandum to form the Dockyard Defence Battery. Over 5,000 workers joined this battery so that the men could take turns between manning the guns, as well as working in the dockyard. The gun posts manned by these workers were located overlooking the dockyard, spanning Floriana, Valletta, Marsa, Corradino and Bormla.

Great sorrow came over me as events unfolded in June 1940. Summer was approaching when sirens broke the peaceful morning and within minutes, the sounds of explosions blasted everywhere. I looked up to the sky and saw shadows of large flying contraptions dropping bombs indiscriminately on civilian installations.

As the sirens sounded, I realised that the war in Europe had finally reached the islands. The first bombing raids changed the face of the Three Cities. It was heartbreaking to watch! The once vibrant life in the cities had come to a standstill. The senseless destruction of the beautiful cities I remember, followed. Churches, chapels, palaces and houses, none were spared. The cities turned into ghost towns as people left the cities in droves.

The beginning of 1941 was rather peaceful in comparison, but it was the calm before the storm. On 9th January, an enormous ship approaching the islands was attacked incessantly, and even as it limped into the harbour on 10th January. As the ship was headed for the French Creek, I could make out its name: HMS Illustrious. It was as long as five galleys and as wide as another five galleys. After entering the docks, the dockyard workers laboured tirelessly to repair the ship, when on 16th January HMS Illustrious once more became the target during air raids. A rain of bombs fell on my three beloved cities, burying hundreds of people under the rubble. The greatest tragedy occurred when St Lawrence Church was hit and 35 people

who had sought shelter in the crypt were killed, buried under the debris. Only a few days later, another attack obliterated the Basilica of Our Lady of Victory and destroyed the Annunciation Church of the Dominican Order in Birgu. During this attack, three men from the Dockyard Defence Battery, Lieutenant Angle, Sergeant Apap and Bombardier Balzan, were awarded the Military Medal for their bravery in manning the guns under adverse conditions. The battery was disbanded in 1941 and the men had the option to join the Royal Malta Artillery or return to work in the dockyard.

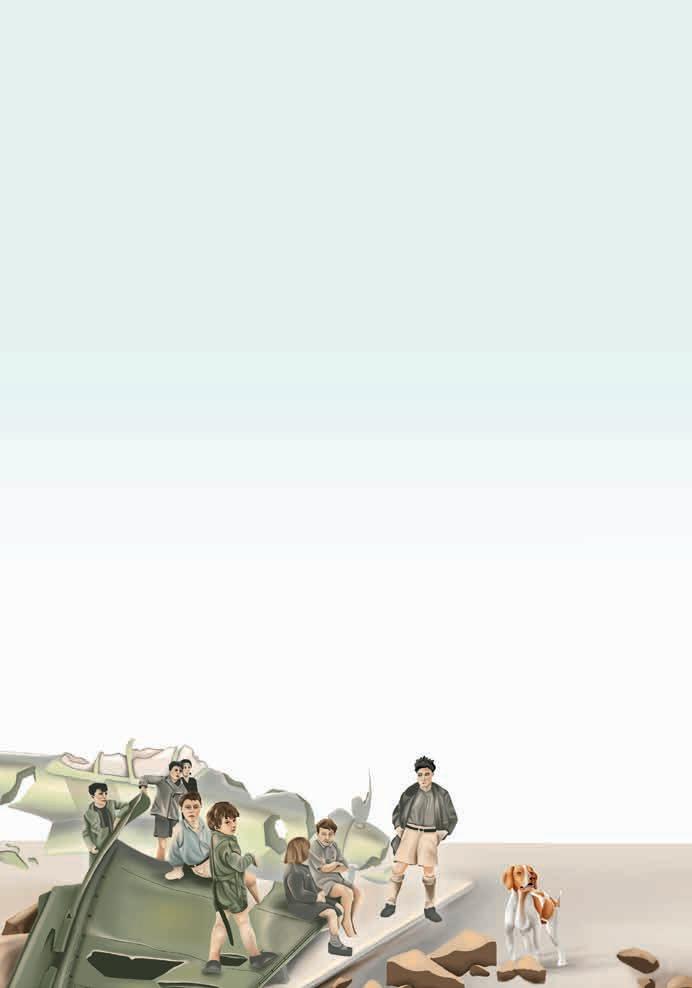

Attack after attack destroyed the façades of the magnificent cities we had built and some areas were completely razed to the ground. I had never seen such destruction before, executed is such a short time! The bombing continued in 1942, when rumours spread that the course of the war would change, but the hunger pangs of the civilians were felt in all Three Cities. Sometimes, a hint of a smile crept onto my lips when children dared to play among the rubble and wreckage of downed enemy planes.

In July 1943, the darkest hours ended for the islands when the defenders became attackers and the Allies invaded Sicily. The situation improved dramatically and air raids decreased significantly. On 8th September, the feast of Our Lady of Victory, it was decided to bring back the Bambina for the annual procession. During the procession, the Archpriest of Isla received the news that the Italians had signed the armistice. What joy spread throughout the streets! This was the most beautiful news to reach the islands after three years of bombardment. Slowly, normality returned, and at the end of July 1944, the statue of St Lawrence was also brought back from Mdina where it had been taken to safety in the first days of the war. In the meantime, the parish church was repaired to celebrate the feast in the first days of August. Finally, a few months later, the statue of the Immaculate Conception was brought back from Birkirkara to Bormla to end this dark chapter and usher in a new one for the devasted Three Cities.