13 • Spring 2023

The

Issue

BULLETIN

Issue 13 • Spring 2023 BULLETIN The

is the official bulletin of Heritage Malta published twice a year in Spring and Autumn

Editorial Team

Margaret Abdilla Cunningham, James Licari, Maria Micallef, Godwin Vella

Technical Review

Ruben Abela, Anthony Spagnol, Sharon Sultanta

Editorial Office

35, Heritage Malta Head Office (Ex Royal Naval Hospital)

Dawret Fra Giovanni Bichi

Il-Kalkara, KKR 1280

Malta

Technical Support

George Agius, Matthew Balzan, Fiona Vella

Photography & Design

Pierre Balzia

Images provided by authors are acknowledged accordingly.

Illustrations & Visuals Enhancement

Kimberly Azzopardi

Subscriptions

publications.heritagemalta@gov.mt

ISBN: 978-9918-619-31-3

Copyright

Produced by © 2023 HERITAGE MALTA PUBLISHING. All rights reserved in all countries. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the rightful owner of the material.

Material for submissions

We invite anyone who wishes to contribute to future TESSERÆ issues to send a 300-word abstract of the subject related to cultural heritage, with the final full article (max. 2500 words) to be submitted to publications.heritagemalta@gov.mt.

Acknowledgements

Heritage Malta Chairman, Board of Directors, CEO, COO and staff members in Conservation, Curatorial, ICT & Corporate Services, and Projects Divisions, all their respective Departments.

From the Museum Fototeka Għexierem road prior to modernisation

Remembering the Great Siege of Malta through paintings, arms and armour – Part II

Robert Cassar

Anthony Spiteri: the Custodian & the War

Janica Buhagiar

Il-Ballut ta’ Marsaxlokk and Its Ornithological Importance

James Aquilina

Painted in Colonial Mexico: A Set of Seventeen

Joanna Hili Micallef

Dear Tim: Tim Padfield’s Contribution to Conservation

David Frank Buġeja

When History meets Biology: Shipwrecks as Ecological Hotspots

Nick Coertze, Timothy Gambin, Maja Sausmekat

Innovating Traditions: Interview with Alda Bugeja

Fiona Vella

Heritage Malta’s Greening Initiatives

Ruben Abela

Untitled painting by Giorgio Preca: Challenges in Conservation

Rachel Vella

Conserving Earthenware Amphorae: Xlendi Shipwreck, Gozo

Joanne Dimech

Modern and Contemporary Works added to the National Collection

Katya Micallef

Education during World War II

Maria Micallef

Gypsoteca: Gypso-take-care! Preservation of Plaster Casts

James Licari

Curator’s Pick...

Sharon Sultana

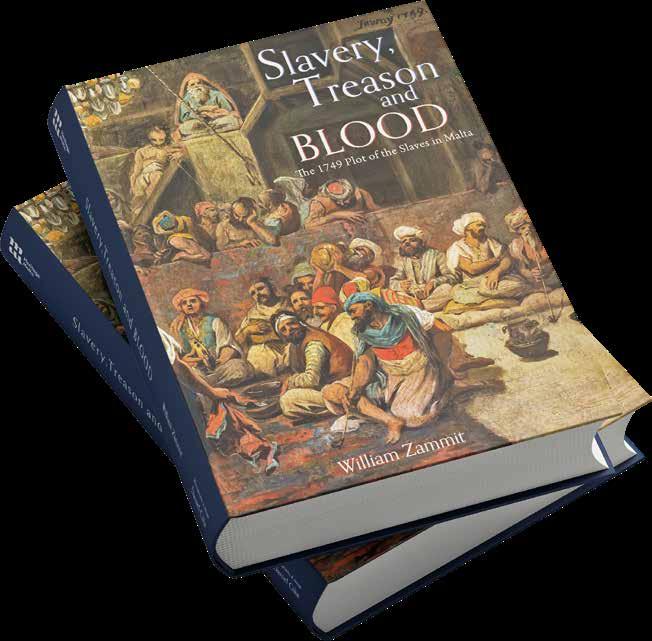

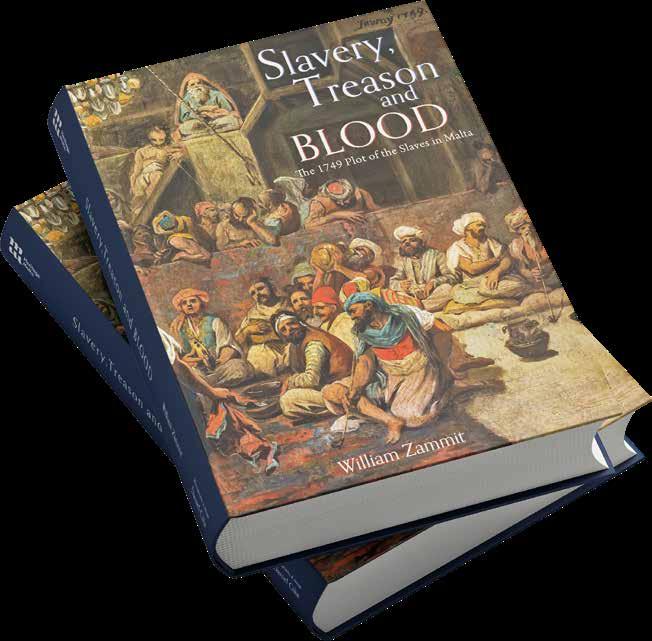

Fresh From the Press...

Heritage Malta Publishing

Fr Marius Zerafa and Frá John Edward Critien

Appreciation

The Contributors

2 Contents 4 12 20 30 40 46 54 62 68 76 84 88 94 100 102 106 110

“The history book on the shelf is always repeating itself”, says an ABBA classic.

Each spree of technological development and urban intensification, triggers a strikingly similar communal reaction, irrespective of the temporal or geographical milieu. A couple of centuries back, the then pristine environment of the Maltese Islands aroused great interest in Grand Tour enthusiasts. The numerous well-read and prosperous visitors, hailing from heavily urbanised contexts, were mesmerised by the unassuming existence of the local peasants, and expressed a unanimous wish for a less frenetic way of life.

Surely enough, an equally marked longing for a less taxing lifestyle is growing by the minute among the present inhabitants of Malta and Gozo. The rampant construction activity in each and every urban neighbourhood, the embracement of an increasingly sedentary routine, and the overcrowding of the few and restricted chillout locations across Malta and Gozo, invariably tipped the scales of collective wellbeing. In turn, exasperation is ballooning without any sign of restraint, whereas the need to unwind is becoming ever more critical. Recurrent overseas getaways are not an option to the greater portion of the population, but the Islands’ outstanding patrimony can prove to be a similarly effective safety valve.

Conscious of the prevailing state of affairs, Heritage Malta is striving to rescue from oblivion and open up for public enjoyment a multitude of sites. It is also crafting the immediate environs of select sites, including Ħaġar Qim, Mnajdra, Ġgantija, and Għar Dalam into heritage parks. Furthermore, the National Agency for museums, conservation and cultural heritage teamed up with esteemed local and Italian stakeholders to unlock the untapped potential of a number of Natura 2000 sites in Malta and Sicily. Labelled CORALLO, this Interreg project aims at promoting the largely-unknown and unique living and landscape assets of each site, while providing guidance on their responsible enjoyment.

Heritage Malta’s Underwater Cultural Heritage Unit is complementing this laudable initiative by valorising shipwrecks as ecological hotspots. This programme is amply illustrated in the second feature in this issue’s management (orange) section. An equally interesting feature, the third of a series, sheds light on the ornithological importance of the wetland at Il-Ballut ta’ Marsaxlokk. Sustainable management of landscape assets, and by default the enhancement of our standard of living, can take less momentous proportions as accentuated by the greening initiatives spearheaded by the Agency’s staff. Besides bringing to the fore the key importance of a sane environment for our own health, TESSERÆ 13 contains a well-balanced assortment of features, ranging from Early Modern weaponry to the innovation of cottage crafts and the care of plaster casts. Slowly but surely, TESSERÆ is building into a respectable and wide-ranging compendium of the Maltese Islands’ outstanding patrimony.

3

Remembering the Great Siege of Malta

through paintings, arms and armour

Part II

Robert Cassar

Part I of this article was published in Tesserae Autumn Issue 12, 2022, which focused on the historical aspect of the Great Siege of 1565, its commemoration as an historic event, and the detailed narrative of the wall paintings found in the Sala del Gran Consiglio inside the Grand Master’s Palace. In this second part of the article, the painted frieze depicting the highlights of the Great Siege is being studied and analyzed in view of the arms and armour represented, that were used throughout the Siege. The painted frieze, illustrating the most important turning point of the Maltese Islands, was and still is viewed as a monument to that glorious epic battle which

stood against a tenacious bulwark. Apart from the painted frieze, the event is still regarded by the proud local population as a unifying event imbued with nationalism, even though it all happened over four centuries ago.

Troops, Armour and Artillery of the Order

The Knights of the Order of St John were also armed with artillery. In Fort St Elmo, there were 27 pieces of artillery that ranged from small cannons, possibly wrought iron swivel guns and very large harquebuses, or wall posts, also known as ‘moschetti di posta’

Left: A detail from the d’Aleccio wall paintings of the Great Siege at the Grand Master’s Palace

Above: An infantry soldier silhouette illustrating the scale of the hand and a half sword in the Palace Armoury Collection in comparison with a rapier and dagger from the same period

Left: A detail from the d’Aleccio wall paintings of the Great Siege at the Grand Master’s Palace

Above: An infantry soldier silhouette illustrating the scale of the hand and a half sword in the Palace Armoury Collection in comparison with a rapier and dagger from the same period

PICCOLO AL BORGO DI NOTTE A DI V DI

Right: ‘Bastard’ swords illustrated in an engraving of the Great Siege Cycle by Anton Francesco Lucini, ‘IL SOCCORSO

LVGLIO’

Fort St Angelo on the other hand, which was also equipped with artillery, is known to have had several ammunition stores that were laden with gunpowder. Some time prior to the Ottoman attack in 1565, the Duke of Florence had sent 200 barrels of gunpowder to be used in defence during the imminent attack.

The larger part of the troops making up the army of the Order was the land infantry. Apart from a pole arm and other accoutrements, each soldier was also armed with a sword. Most of them were specialised through intensive training in sword fighting, while others excelled

in the use of the pike or other types of polearms. The main type of sword that was used during this period bore long and wide blades. This type of sword is clearly represented in an engraving showing one of the wall painted scenes of the 1565 Siege by Matteo Perez d’Aleccio at the Throne Room in the Grand Master’s Palace. In the scene of the Battle for the Post of Castile, Spanish knights carry two examples known as the ‘bastarda’. At the Palace Armoury, two slightly smaller but similar examples survive and are known as the ‘hand-and-a-half-sword’.

Another sword that was commonly used during the 1565 Siege was the rapier. This very early type had limited hand-guard protection and had a wider blade than the rapiers that were used later on in the 17th and 18th centuries. An example of the Siege rapier survives at the Parish Church Museum of Birgu. This is said to have been the same sword that was used in battle by Grand Master Jean de Valette and which was placed at the foot of the altar dedicated to the Virgin of Damascus as an ex-voto in thanksgiving for the victory of the Siege.

Detail from the wall paintings depicting infantry in battle from the final epic battle of the Great Siege

Detail from the wall paintings depicting infantry in battle from the final epic battle of the Great Siege

this day at the Palace Armoury. The crossbow was regarded as important as the matchlock harquebus firearm. Its main potential was that its aim was more precise and accurate than the firearms of its time. It was an ideal backup weapon when at times gunpowder would not perform at its best. Such occasions included days with high humidity in the air, or during rainfall. The technology with gunpowder was not as yet refined and if wet, it did not ignite.

Another advantage of the crossbow was the fact that it was short and light in weight, and easily loaded and fired from atop high walls towards an enemy trying to climb up a fort’s ramparts. It also had a long range and the

With regards to body protection, the army of the Order had soldiers who wore steel armour that protected them against arrowheads and edge weapons but had very little defence against gunpowder propelled weapons. Some time prior to the beginning of the 1565 Siege, Grand Master de Valette had issued a decree where all knights of the Order living outside the islands were called to arms at the Convent (i.e. Malta) to defend the territory and Faith. They were also obliged to bring their own personal armour and weapons, since clearly there was a lack of arms.1

Apart from the steel armour, each knight was to wear a tabard, which was a sleeveless bib bearing the cross of religion in white against a red background. The intention for this was to encourage a sense of uniformity among the knights while also serving as a recognition factor for one’s own fighters during battle. The uniformity was also needed due to the fact that since knights came from various countries from all over Europe, they brought with them armour typical of their region, at times some that were also obsolete or outdated for its time.

7

Crossbow from the Great Siege period found at the Palace Armoury, Heritage Malta Collection

An early rapier used by Grand Master de Valette in battle, given to the Virgin Mary as an ex-voto in thanksgiving, found at the St Joseph Oratory Museum, Vittoriosa, photo courtesy: Daniel Cilia

Remembering the Great Siege of Malta through Paintings, Arms and Armour: Part II

An account by Cirni from the Siege, speaks of the diversity in the types of protection worn by the knights. These included corsaletti and corazze (metal armour), giacchi (brigandines)2 and maniche di maglia (mail shirts)3. The tabard uniform has been repeatedly represented in the wall painting scenes of the Great Siege by d’Aleccio at the Grand Master’s Palace in Valletta.

Personalised armour owned by a knight would have differed from those issued by the Order to its soldiers. This personalisation was achieved by a high degree of surface decoration to the metal plate. The amount and quality of decoration depended on the individual and his financial status in society. Most of the time, such armour was engraved, etched and gilt. At times, the beauty itself in these armours served more of a disadvantage to its bearer, since its bejewelled shine attracted attention to the knight above the rest of the soldiers, becoming an easy target, apart from announcing to the enemy his important and high ranking position witin the Order. This was the case of the nephew of Grand Master de Valette, Henri de Valette, who wore a highly decorated gilt armour which made him an immediate target and was killed as he stood out facing the enemy.

On the other hand, the half armour normally issued to the conscripted soldier was similar to the ones owned by the knights, although bare of any decorations except for some embossed scrolls in some particular cases. However, this was still as resistant and strong as those belonging to the knights. This type of armour

8

Detail from D’Aleccio’s wall paintings at the Grand Master’s Palace showing knights wearing tabards

Parts from a decorated armour with fine engraved detail, from the Great Siege period at the Palace Amoury Collection

issued still exists within the Palace Armoury collection in a large amount and such numbers give an indication of the even larger amounts that originally existed in the Order’s armouries. These date to the Great Siege period and had been specifically ordered to supply the troops of the Order of St John. The soldiers who wore these armours were normally around their mid-teens. Such can be immediately understood by looking at the size of these metal suits which show that their bearers were very small in stature, both in height and around the waist.

These soldiers, also referred to as the ‘foot infantry’, were armed with polearms such as the pike and the halberd. Some also carried a shield at times made of wood. These examples made of two layers of wood bent and carved were covered in textile and painted with the cross of religion or other heraldry. Apart from being lightweight and resistant to fired projectiles, such shields could be used as a weapon during one-to-one combats. Various examples still exist in the Palace Armoury collection and also feature in several scenes from the d’Aleccio wall paintings. Cavalry was also very important during the Siege, particularly during attacks outside fortifications on the Ottoman infantry parties. An example in Heritage Malta’s Armour Collection represents a typical cavalry soldier wearing armour that covered up to his thighs and knees, whilst being armed with a long polearm referred to as the ‘lance’.

The Ottomans’ superior artillery

A major element that presided throughout the 1565 Siege was the use of artillery from both sides. However, while the Ottomans made use of copper-alloy bronze guns that had been brought over to the island by means of their

9

Left: Two different pikes from the Great Siege era in the Armoury Collection at the Grand Master’s Palace

Right: Detail of an infantry soldier with the longer pike on the left in scale, from an engraving of the Great Siege Cycle by Anton Francesco Lucini, ‘IL SOCCORSO PICCOLO AL BORGO DI NOTTE A DI V DI LVGLIO’

A wooden battle shield covered in textile with the painted eight-pointed Cross of the Order from the Great Siege era from Heritage Malta Armoury Collection at the Grand Master’s Palace

naval power, the Knights of St John mostly made use of wrought iron hoop and stave construction guns, an archaic form for their time. Some must have been imported on the eve of the Siege itself, while most lay in fortresses, some of which could have even been brought over from Rhodes earlier on in the century. Such artillery would not have been as effective as that of their foe. Ottoman artillery consisted of various sizes with regards to the calibres of shot being fired. These varied from as large as half a metre in diameter, to a shot as small as a tennis ball, and were made of stone. They were brought over as ballast at sea, ready cut from Anatolian hard stone. On the other hand, the Order made use of much smaller calibres and their guns were found in strategic points on

forts and bastions. Apart from wrought iron guns, the Order also had a small number of bronze guns.4

The Ottomans carried their cannon to the ramparts of Fort St Elmo and Dragut’s point, now known as Tigné Point,5 set up for the attack against the fort. One scene from the wall paintings shows the death of Ottoman commander Turgut Reis better known as ‘Dragut’, who was accidently killed by friendly fire shelling towards Fort St Elmo. Two Ottoman Basilisk cannon used throughout the Siege, two of which are documented to have been brought to Malta, were extremely huge and heavy. These were locally referred to as ‘il Gran Basilisco Turco’. A similar example survives at Fort Nelson Portsmouth Artillery

10

Ottomans firing their cannon during the Great Siege, detail from D’Aleccio’s wall paintings at the Grand Master’s Palace

Part of an Order’s hoop and stave cannon surviving from the Great Siege era found at the Palace Armoury Collection illustrated as it had originally appeared

Museum. On the other hand, the Knights made use of the smaller wrought iron hoop and stave cannon, while the bastions would have been equipped with heavier bronze guns supported on wooden carriages.

Conclusion

Such knowledge of the Knight’s disadvantages concludes this two-part article with a feeling of pride and love for our country. For the Order of St John and the Maltese, the feast of the lifting of the Great Siege was extremely significant, not

Notes & References

1 Stephen. C. Spiteri, Armoury of the Knights, Malta, 2003, p. 57; “. . . armati di petti forti, di corsaletti, di morrioni, d’archibusi, di picche, d’alabarde e d’altre armi”.

2 A ‘brigandine’ is a form of body armour dating from the Middle Ages. It is a cloth garment, generally canvas or leather, lined with small oblong steel plates riveted to the fabric.

3 Stephen C. Spiteri, The Great Siege, Knights vs Turks MDLXV , Malta, 2005, p. 335.

The fatal wounding of Dragut, immortalised in a detail of D’Aleccio’s wall paintings at the Grand Master’s Palace

only owing to the Virgin’s Nativity falling on the 8th of September in the religious calendar, but also because the victory was considered a clear sign of Divine intervention, which was translated into an intense sense of national pride. The Maltese and the Order of the Knights of St John, from this point onwards, adopted their true legendary hero and mentor as seen in the figure of Grand Master Jean de Valette, whose strong character, resolution, leadership and Faith remained marked for posterity in the Maltese identity.

4 One extant example is a gun carrying the coat of arms of Grand Master L’Isle Adam that is on display at St John’s Gate Museum, Clarkenwell in London.

5 Tigné Point takes its name from an 18th-century fort built later (1793-1795??) by the Order of St John at the tip of the peninsula. It was commissioned by Grand Master Emmanuel de Rohan-Polduc and named after the Knight François René Jacob de Tigné, nephew of the equally distinguished military engineer René Jacob de Tigné who also served the Order with his military expertise.

11

Janica Buhagiar

Anthony Spiteri the Custodian & the War

Lina Cardona née Spiteri spent five years during World War II actually living in the ‘Roman Villa Museum’, as it was known then. Her account is unique, giving a rare glimpse of one of Heritage Malta’s earliest sites. Interesting information is garnered during a time when there were no written Museum Annual Reports (MAR), between the years of 1940-45.

Nowadays, the Museum interpretation is reaching for a bigger set of questions and perspectives. Beyond the MAR, the focus is not just on the objects themselves but on larger themes that the objects, and sites themselves evoke.

The Anthony Spiteri persona

The Domvs Romana remained active in its service to the public and instrumental to support the then Museum’s Department to conserve our heritage, but the site was also home to the Spiteri family, namely Mr Anthony Spiteri, who gave over twenty years of his life as Assistant Custodian and Official Guide.1

Anthony Spiteri was born in Valletta in 1902 and although he initially started working in the catering business at the Osbourne Hotel at South Street, his passion for history and study attained him a custodianship with Heritage Malta, then the Museums Department. As an Assistant Custodian and Official Guide, he oversaw the daily running of the sites, as well as selling tickets. Spiteri attended school in Valletta, but he was an autodidact throughout his life, focusing primarily on history, archaeology, and languages. As a linguaphile, Spiteri was fluent in seven languages2 and used them whenever he could during his tours to communicate his beloved

photographs and script images in this article are courtesy of Lina Cardona

Maltese history to the visitors. His daughter, Lina Cardona, fondly remembers her father studying late at night next to a kerosene lamp; his notes about historical sites, translated in many languages bear testament to his erudition.

A man of discipline, which is also reflected in his rigours of studying and family life, whichever historical site summoned him for his duty, Anthony took his family along with him. During the war, he was the custodian of the Rabat area, then comprising two sites: the St Paul’s Catacombs and the Domvs Romana, then known as the 'Roman Villa'. Although originally from Valletta, Lina’s family had moved to Floriana, and two years before the

13

Anthony Spiteri

Old

outbreak of WWII, the family moved from Floriana to Tarxien. It was from the latter town that the Spiteri family moved to Rabat in 1940, when Malta had instantly entered the war. Lina and her family had listened to Mussolini declare war on the radio a day prior to being officially announced in Malta. The following morning, her father left early for work, as he feared the public transport might be somewhat disrupted. He asked the then Director of Museums, Chev. H.P. Scicluna, that he needed to pick up his family to transfer them to Rabat. By three in the afternoon, Lina and her family had packed their belongings and headed to Rabat in a taxi, it would be five years later when they return to Tarxien.

Life at Rabat - the Museum residence

Prepared with his translated notes, Anthony was ready to head to the St Paul’s Catacombs and the Domvs Romana, the latter being their temporary residence. Anthony loved St Paul’s Catacombs, as did the young Lina. She remembers the kerosene cooking stove (spiritiera) at the ticket booth and enjoyed the site’s peach and prickly pear trees.

Yet war changed everybody’s prospects. Historic sites closed down, artefacts were damaged and underground sites, such as the catacombs, were used as air raid shelters. The Report on the Work of the Museum Department for 1946-47 by J.G. Baldacchino mentions that the Domvs Romana was “… closed to the public from September 1939 to April 1945 and its more important exhibits transferred to Saint Paul’s Catacombs and stored underground. The tessellated pavement

14

Anthony Spiteri: the Custodian & the War

Anthony Spiteri, fourth from Right in a

Anthony Spiteri’s personal notes in German about Għar Dalam Cave

of the impluvium was covered with soil and rubble to a depth of four feet as a protection against falling masonry.”3

On one particular occasion, Anthony happened to be inside St Paul’s Catacombs when enemy bombs dropped during an air raid. Parts of the catacomb gave way and Spiteri ended buried knee-deep in rubble. From that day on, he decided that his family would no longer shelter or sleep inside the catacombs. Instead, they took refuge from the bombing inside the shelter across the street from the Domvs Romana. He instructed a local carpenter to install bunk beds, where the parents slept at the bottom bunk and their four young daughters slept on top.

“The constant threat of aerial bombardment was part of daily life,” Lina admits, “nonetheless, Malta tried to regain a sense of normality.” Lina attended holy mass at Ta’ Duna chapel4 and continued her education at Rabat; not even

15

Anthony Spiteri, second from right with some unknown colleagues at the reception entrance of St Paul’s Catacombs

Anthony Spiteri’s personal notebook in French (Above) and in Italian (Below) about the St Paul’s Catacombs

air raids spared them from the English lessons which continued inside underground shelters. Across the Domvs Romana, Lina remembers that the farmers’ market gathered at the corner where the souvenir shop currently is. Further down, a Victory Kitchen stood instead of the restaurant, not far from St Margaret Cemetery, where refugees from Cottonera were temporarily housed. One cook from the Victory Kitchen, known as ‘Tal-beċċun’, became renowned for his baking and after the war he opened a confectionary shop at Lampuka Street in Tarxien. Lina also reminisced how “We accessed Mdina from Greek’s Gate, as it was closer to the Domvs. Some daily groceries could also be purchased from a small shop at the entrance of Mdina.”

The Spiteri family - recollections

Since the Domvs Romana became their home for the next five years, the Spiteri family became known through the byname ‘tal-Mużew’, which translates to ‘of the museum.’ Needless to say, Anthony was well-known in the area, as he was often sought after to write and read letters for the locals. Indeed, the Spiteri family were distinguished in many ways from the local Rabat population, since they were a family from Valletta who resided in a unique and comfortable living space, fitted with a telephone, a radio, and of course, they lived within the remains of a rich, aristocratic Roman townhouse. The family liked their life at Rabat and felt welcomed and accepted by the locals;

16

Above: Mosaics at the Domvs Romana and Right: The museum interpretation panel acknowledging Anthony Spiteri

so much so that it was with reluctance that they left for Tarxien after the war. “We had carried on with our life. I continued my schooling and used to stay at the Domvs – I had chores there,” Lina recalls, “And of course the mosaic! My father was adamant about this; he warned us never to step on the mosaic. Rest assured, we never did.”

Under the eyes of conservators and restorers, it would have been difficult for Lina and her sisters not to be caught misbehaving. The Domvs Romana was closed during WW II, and it became a restoration centre before reopening to the public in 1945. Cassar (2000) states that over the period of two and half years, there were over 3,000 air raid alerts with more than 14,000 tons of bombs dropped.5 War

revealed that many works of art and architecture were in a poor state. Between 1939-47 over four hundred paintings were restored, and between 1948-50 a further fifty-two paintings were restored. As witnessed by the young Lina, she remembers some of the restorers, such as Sir Temi Zammit’s son, Charles, and the sculptor, Antonio Sciortino, then the curator of the Malta Museum of Fine Arts. Even as a young child, Lina observed that although advanced in years, Sciortino, with his hallmark pencil moustache and fondness for hats, still looked like a professional and remained a dedicated curator.

Most of the paintings damaged during the war which were transferred to the Domvs Romana were small or medium-sized, but Lina remembers one of the large format paintings:

17

the altarpiece of Our Lady of Liesse and the Three Knights from Our Lady of Liesse Church in Valletta, which measured 75 inches by 121 inches6 as the church was badly damaged by the German bombing in 1942. The altarpiece, depicting Our Lady of Liesse with Child is an 18th-century oil painting by Enrico Arnaud, which Lina remembers being restored at the Domvs Romana. It was a lengthy process, she recalls, where the tears were filled with woven fabric, and starch with flour were used instead of glue, as it was sparse. Many paintings were relined and the altarpiece7 was stripped of its old relining canvas to be cleaned of the old glue, mended, and re-used again for the relining of the same painting. “It was a painstaking work, and some of the restorers used to stop often for breaks,” Lina recollects, “but the moment they saw Sciortino coming their way, they used to scurry back to their work!”

Lina also remembers her father mentioning and working with Captain Olof Frederick Gollcher, a shipping magnate, perhaps best known as the owner of Palazzo Falson and a scrupulous collector of historical objects. Palazzo Falson was not only his home but also a setting for his works of art and antique collection. Although Lina never met Gollcher himself, she does remember that her father was often invited to Gollcher’s soirées, as Spiteri’s catering background and historic knowledge were an ideal blend for Gollcher’s social gatherings.

Her fondest memory of the Gollcher family is, however, that of Olof’s wife, Vincenza. “My sister, Margaret, was very young at the time and she was left at the Domvs unattended, as my mother and father were managing a large tour at the museum.” Little Margaret found a box of

matches and unwittingly set a small doll on fire, which happened to be placed in the wardrobe. It was the Cottonera refugees, temporarily residing across the street, who first came to her aide as the wardrobe, along with all the clothing, burnt to ashes. When Vincenza Gollcher heard of the incident, she donated clothes to the Spiteri family, “I remember a particular Air Force blue coat and sheer, georgette dresses with white flowers.” recalls Lina, “We were very grateful for her kindness.”

Besides the locals, the Spiteri family encountered British troops and their families stationed on the island. “It was they who usually requested a tour,” Lina explains, “Of course, my father was always happy to oblige and from the Domvs, they walked towards St Paul’s Catacombs even if the museums were at the time closed to the public.”8 Although they usually had no problems with the military, on one occasion Lina recalls a frightful incident. It was late at night when they were woken by loud thumping at the Domvs Romana doors. She recalls how “Someone was kicking at the doors, yelling rude expletives as they rapped on the windows, wanting to break inside.”

Terrified, they phoned the police who swiftly arrived on site. The police found some young soldiers, clearly inebriated, who for some reason decided to break inside the Domvs Romana. “The police were aggressive with them,” Lina continues, “in fact, my mother, Carmela, who was the one who had phoned the police, begged them to stop harassing the soldiers.”

Ironically, the ending of the war was bittersweet for the Spiteri family, as after the war in 1945, they were asked to leave the Domvs as it was once again reopening for the general public. The family returned to Tarxien, where Anthony

18

Anthony Spiteri: the Custodian & the War

resumed his work as a custodian and guide at Tarxien Temples, until he retired in 1962. Yet, his tour guiding was not over, as he often took Lina’s children to his beloved temples where he encouraged them to play and roam about. “And then, he would bring them home covered in dirt,” Lina recollected, “Imagine my dismay! But he would tell me, they were just having a bit of fun. After all, we used to do the same at the Domvs. My father wanted to share history with everyone.”

Conclusion

Anthony Spiteri loved his career, which is evident in how he had perused it with determination and turned it into his lifelong study. Thankfully, his dedication was acknowledged. After his retirement, the Museums Department had requested that he would continue to work with them. Sadly though, it was short-lived. On 5 October 1966, at 4.00 pm, Anthony Spiteri left the National Museum of Archaeology after a day’s work. Carrying his usual load of books, he slipped at Melita Street and tragically slammed his head against a wall. He was found concussed by a judicial clerk, who immediately recognised him and rushed to the National Museum urging them to telephone the ambulance. Twelve hours later, he was declared dead; he was 64 years old.

Anthony Spiteri’s legacy did not end there, his life and work are commemorated in one of the interpretations at the Domvs Romana, along with the stories from Ancient Rome, curators and conservators who had animated the archaeological site. As a museum, the Domvs Romana emphasises categories and historical periods, but its interpretation also

focuses on human experiences. As exemplified by Anthony Spiteri’s story, the Domvs Romana explores the long and complex history of the Domvs’ human relationship with the world beyond its gates, although the museum may still be regarded as just one institution, among many, receptive to this kind of investigation.

Notes and References

1 C. Zammit, ‘Report of the Working of the Museum Department for the year 1964’, “The only other change in the complement of the Museum occurred at the end of August with the retirement of the service of Mr A. Spiteri after over twenty years as Assistant Custodian and Official Guide. The vacancy was filled by public competition and Mr F. Borg was engaged in the same capacity as from September 1.”, printed at the Department of Information, Malta, 1963, pp.2.

2 Languages included: English, German, Maltese, Italian, Latin, French and Arabic.

3 Annual Report of the Work of the Museum Department for 1946-47, by J.G. Baldacchino.

4 Built in 1658 Ta’ Duna Chapel in Rabat is dedicated to St Mary and the Seven Gifts of the Holy Spirit. ‘Ta’ Duna’ is the Maltese dialect for ‘ta’ doni’, i.e. ‘of the gifts’.

5 Cassar Charles, A Concise History of Malta, 2000, p.225, and Zarb-Dimech Anthony, Taking cover: a history of air-raid shelters: Malta, 1940-1943, 2001, p.7.

6 National Museum of Fine Arts Archives, ‘List of pictures restored at the Rabat Museum 1 June 1942’

7 Anthony Spagnol, The conservation of the Artistic patrimony in Malta during WWII, 2009, Heritage Malta, pp.34-5.

8 From the beginning of April to 31 March 1946 and from the beginning of April to March 1947, Domvs Romana amounted to 1698 and 1476 visitors respectively, while St Paul’s Catacombs amounted to 3706 and 1567 visitors respectively, Annual Report of the Work of the Museum Department for 1946-47.

19

James Aquilina

Il-Ballut ta’ Marsaxlokk and Its Ornithological Importance

An Interim Report June 2017 – June 2018

Part 3 is a continuation of Part 1 review published in TESSERÆ Issue 6 of Spring 2018 and Part 2 published in TESSERÆ Issue 9 of Autumn 2019 with the same titles. The first and the second articles focused on the ornithological importance of the wetland of Il-Ballut Ta’ Marsaxlokk located on the south-eastern coast of the Maltese Islands (coordinates 35.838868, 14.548871). Wetlands in Malta deserve more attention as this habitat is scarce on the Maltese archipelago and offers migrating birds a much-needed rest on their way to warmer climates or breeding grounds. Part 3 continues on the 2017-2018 records uncovering further the wide variety of species visiting this particular wetland with the added interest of first-time recorded species.

Position and avifauna of Il-Ballut ta’ Marsaxlokk wetland

The geographical position of Il-Ballut ta’ Marsaxlokk lures a different number of migratory birds during autumn and spring migration. As of 17 June 2018, around sixty-seven species were

recorded on site and in the nearby area, five of which breed on the Maltese Islands

Summer Sightings 2017

In summer 2017, few migratory birds have been sighted. From 26 June until end of August, birds of sedentary nature had been recorded in the wetland.

Migratory birds were noted during the last week of August when an occurrence of three Barn Swallows and one Yellow Wagtail were recorded. Three additional Yellow Wagtails were also recorded by the end of summer. On 3 September, thirty-five European Bee-Eaters were sighted in the nearby areas of tas-Silġ. Five Bee-Eaters from the flock flew over the wetland, albeit at a high altitude, while a Barn Swallow was also recorded.

Swallows were recorded in the subsequent weeks during the month of September.1 They were also sighted during the first week of October. On 17 September, three Grey Herons flew in the direction of Tas-Silġ and Delimara.

In autumn, European Bee-Eaters reach the Maltese shores in late August and beginning of September

Right: Aerial view of the wetland of Il-Ballut ta’ Marsaxlokk

Left: Blue throat, photographed at Il-Ballut ta' Marsaxlokk wetland

Right: Aerial view of the wetland of Il-Ballut ta’ Marsaxlokk

Left: Blue throat, photographed at Il-Ballut ta' Marsaxlokk wetland

21

Il-Ballut ta’ Marsaxlokk and Its Ornithological Importance

Species Month Of Occurence December 2014 - June 2018

Wood Warbler - Phylloscopus sibilatrix

Little Stint - Calidris minuta

European Bee-Eater - Merops apiaster

European Pied Flycatcher - Ficedula hypoleuca

European Turtle-Dove - Streptopelia turtur

Sterna sandvicensis

Zitting Cisticola - Cisticola juncidis

Eurasian Chaffinch - Fringilla coelebs

Common Chiffchaff - Phylloscopus collybita

Sardinian Warbler - Sylvia melanocephala

European Robin - Erithacus rubecula

Stonechat - Saxicola rubicola

Common Whitethroat - Sylvia communis

Black Redstart - Phoenicurus ochruros

Spanish Sparrow - Passer hispaniolensis

White Wagtail - Motacilla alba

Meadow Pipit - Anthus pratensis

Western Marsh-Harrier - Circus aeruginosus

Black-Winged Stilt - Himantopus himantopus

Reed Bunting - Emberiza schoeniclus

Yellow Wagtail - Motacilla flava

Northern House-Martin - Delichon urbicum P/M

Barn Swallow - Hirundo rustica P/M

Spotted Flycatcher - Muscicapa striata P/M

22

STATUS Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec

R*

P/M

P/M

Great Cormorant - Phalacrocorax carbo

Sand Martin - Riparia riparia

Wood Sandpiper - Tringa glareola

P/M

P/M

P/M

P/M

P/M

R

P/M

R

P/M OR R* Woodchat

P/M Whinchat

P/M Song

philomelos P/M Common Starling - Sturnus vulgaris R* Yellow-Legged Gull - Larus michahellis R Black-Headed Gull -

R* Mediterranean Gull - Larus melanocephalus R* Caspian Gull - Larus cachinnans R* Sandwich Tern -

R*

Cetti’s Warbler - Cettia cetti

Common Swift - Apus apus

Mallard - Anas platyrhynchos

Common Sandpiper - Actitis hypoleucos

Shrike - Lanius senator

- Saxicola rubetra

Thrush - Turdus

Larus ridibundus

R

P/M

R*

R

R*

R*

P/M

R*

R

R*

R*

P/M

P/M

P/M

P/M

Species Month Of Occurence December 2014 - June 2018

Icterine Warbler - Hippolais icterina

Common Kestrel - Falco tinnunculus

Common Kingfisher - Alcedo atthis

Grey Wagtail - Motacilla cinerea

Eurasian Skylark - Alauda arvensis

Common Snipe - Gallinago gallinago

Sedge Warbler - Acrocephalus schoenobaenus

Little Egret - Egretta garzetta

Spotted Redshank - Tringa erythropus

Dunlin - Calidris alpina

Rail - Rallus aquaticus

Great Crested Grebe - Podiceps

Bird sightings during autumn migration

(25 September – 17 December 2017)

Vagrant Bird

The Brown Shrike was recorded for the first time in the Maltese Islands in the marshland of Marsaxlokk. Primarily it was sighted on

2 November 2017.2 On Saturday 4 November 2018, Shrike was recorded again along with other wintering birds. It has been sighted perching in the tamarisk trees adjacent to the courtyard of the Hunter’s Tower feeding on insects.3 On 19 November it was noted again.

This bird is considered as a vagrant bird to Europe as Brown Shrikes are familiar with the

23

STATUS Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec

P/M

P/M

OR R*

P/M OR R*

R*

R*

P/M

P/M

P/M

P/M

P/M

P/M OR R*

cristatus R* Blackcap - Sylvia atricapilla R* Gadwall - Anas strepera P/M Black-Necked Grebe - Podiceps nigricollis R* Subalpine Warbler - Sylvia cantillans P/M Eastern Bonelli’s Warbler - Phylloscopus orientalis P/M Slender-Billed Gull - Larus genei P/M OR R* Squacco Heron - Ardeola ralloides P/M Grey Heron - Ardea cinerea P/M European Honey-Buzzard - Pernis apivorus P/M Willow Warbler - Phylloscopus trochilus P/M Garganey - Anas querquedula P/M Red-Throated Pipit - Anthus cervinus P/M Tree Pipit - Anthus trivialis P/M Brown Shrike - Lanius cristatus P/M Eurasian Linnet - Carduelis cannabina P/M Pigeon - Columba livia R

P/M

Passage Migrant R*

Migratory & Winter Resident

Water

R = Resident

=

=

Asian continent. Its breeding grounds are mainly found in Myanmar and South China. In June, part of the population starts to migrate to central, southwest and southern plains of Myanmar.4

From mid-October 2017 onwards, the number of migratory birds followed the normal orthodox pattern. Sightings of Meadow Pipits, Robins, White Wagtails, Stonechat, Common

Starlings, Black Headed Gulls and Chiffchaffs were usually recorded in the area of il-Ballut ta’ Marsaxlokk.

A pair of Yellow Wagtails was recorded late in September. In the beginning of October an adult Willow Warbler was sighted in a tamarisk tree.5 In autumn, Willow Warblers which reach the Maltese shores in mid-August, continue to be sighted until October.6 During the same birding session, a Sedge Warbler was feeding close to one of the pools filled with brackish water.7

Mid-October brought an influx of new Robins, both in the wetland and its surroundings. Three or four Robins were always recorded in the wetland. However, during the month of December, fewer Robins were noted. By the end of October, a pair of Stonechats and one Black Redstart were also sighted. Two Black Redstarts were noted on 19 November. Chiffchaffs seem to have arrived late in the wetland. In fact, they were sighted in the third week of November 2017. In the preceding year, Chiffchaffs were initially sighted on the fourth week of October. Common Chiffchaffs arrive in good numbers in Malta.

Two new species were noted in autumn migration. One Tree Pipit and a Red Throated Pipit had been recorded on 22 October. Red Throated Pipits are more common in spring rather than autumn, but a small number of Red Throated Pipits winter in Malta. In the meantime, a Linnet was observed perching on a tree. Late in October, beginning of November, an occurrence of a Song Thrush along with three Skylarks were also noted.

As observed in previous years, two to three White Wagtails were recorded, while an average of one or two Meadow Pipits were sighted. Exceptionally, five Pipits were counted on

24

Il-Ballut ta’ Marsaxlokk and Its Ornithological Importance

The sighting of a Brown Shrike is considered one of the most important sightings. Courtesy: on site photo by Claude Busuttil

Willow Warblers normally feed on small insects and spiders

10 November and a week later. A good number of White Wagtails roost in the ficus trees of the Great Siege Square in Valletta. It is estimated that over fourteen thousand White Wagtails roost in the capital city alone.8

Common Starlings appeared in the area of Marsaxlokk in mid-October. Since then, sightings of Starlings were sighted approximately on a weekly basis. The biggest two flocks of around forty to fifty Starlings were observed in the first two weeks of December.

Between late September and late December, three different gull species have been recorded. The Mediterranean Gull was the most commonly sighted gull although its main sightings were mainly limited to the third week of November. A flock of fifty Mediterranean Gulls were recorded on 19 November. Further Mediterranean Gulls were listed during the first two weeks of December. Good counts of Black Headed Gulls were also recorded on site. Compared to the Mediterranean Gulls, the number of Black Headed Gull sightings was comparatively lower.

During the same period under review, five Yellow Legged Gulls were observed flying in close proximity to the wetland. The majority of Yellow Legged Gulls tend to stay either floating in the middle of the port or foraging closer to the port of Marsaxlokk, particularly in autumn and winter. Barn Swallows were recorded in the first two consecutive weeks of October. Four Swallows were mainly observed during the first week of October, whereas another Swallow was sighted the following week.

Sightings of birds of prey were mostly encountered during the last week of September and second week of October. On 25 September two Honey Buzzards were seen heading out

25

The Black Redstart is one of the wintering birds normally sighted in the reserve

Common Starlings are quite frequent during autumn and winter

Good numbers of Black Headed Gulls winter in the port of Marsaxlokk, along with Yellow Legged Gulls

from Delimara towards Birżebbuġa. Another Buzzard passed over the wetland at dawn. Two Common Kestrels were sighted over Delimara and an additional Kestrel flew out over the marshland. On 5 October, four Marsh Harriers were recorded,9 while four unidentified birds of prey were sighted during the first week of October.

On 11 October 2017, a Garganey Duck sought temporary refuge inside the wetland. At dusk, it took off from the main lagoon.10

On 25 September, a Common Sandpiper and a Wood Sandpiper were simultaneously

feeding together. Occurrences of Wood Sandpipers are less frequent compared to Common Sandpipers. Sightings of Common Sandpipers were fairly scattered until the end of November.

The usual local sedentary birds have also been recorded throughout autumn. Sardinian Warblers and Spanish Sparrows were regularly recorded in the wetland. The latter remains the most overlooked bird. Zitting Cisticolas were recorded until the end of October.

Winter Sightings 2018 (24 December 2017 –18 March 2018)

The usual wintering bird species continued to be recorded throughout the winter season. Black Redstarts seem to have left the wetland by the beginning of January. Stonechats were normally sighted until 11 February. During the same period, sightings of Common Starlings were lastly recorded by mid-February. Chiffchaffs and Robins left the wetland in the beginning of March 2018. White Wagtails were recorded for the last time on 11 March, while Meadow Pipits were finally logged until the beginning of spring.11 The habitual sedentary birds have also been recorded in the wetland.12 Interesting to note is that one of the Spanish Sparrows was recorded carrying nest material as early as mid-February.

In mid-February, a Caspian Gull was noted crossing over the area between Tas-Silġ and Il-Ballut ta’ Marsaxlokk. In Malta it is considered as a rarity, however it is becoming a regular visitor in central Mediterranean and in the coastal regions of Northwest Europe.13 During the same period under review, five different

Garganey Duck flying over Il-Ballut ta’ Marsaxlokk

26

Left: Female Spanish Sparrow and Right: Female partial leucistic Spanish Sparrow

gull species were recorded. The largest sighting of Black Headed Gulls was recorded in midJanuary when a flock passed over the wetland. During the same period, a small number of Mediterranean Gulls were recorded on site.

Slender Billed Gulls were noted on two separate days. One of the gulls had been observed close to the wetland embankment, while the second one was spotted together with a small group of Black Headed Gulls. Two Sandwich Terns were recorded in the beginning and in late January. An occurrence of a Common Kestrel was noted in early January, while similar sightings were noted in January and February 2016. On a cloudy day in the beginning of March, one Grey Heron crossed over the wetland heading in the direction towards Tas-Silġ. In very late winter, one unidentified wader and a Barn Swallow were recorded.

Spring Sightings 2018 (25 March 2018 –17 June 2018)

Nineteen different migratory species have been recorded during spring migration. Eighteen of the species recorded have been sighted in previous years, but one of the species has never been recorded before. From a total of nineteen species, five of the birds recorded belong to the wader species, another two birds belong to the sea birds’ family, and one belongs to the birds of prey. Yellow Wagtails were among the first migratory species that visited the wetland in spring. They had been recorded over five consecutive weeks, the last sighting being on the third week of April 2018. Tree Pipits were counted in the beginning and mid-April.

Grey Herons common in spring and autumn, tend to be sighted in flocks during stormy weather

Spotted Flycatchers are briefly sighted in spring before continuing their migration to their breeding grounds in Europe

Influxes of Common Whitethroats are normally recorded in spring

Grey Herons common in spring and autumn, tend to be sighted in flocks during stormy weather

Spotted Flycatchers are briefly sighted in spring before continuing their migration to their breeding grounds in Europe

Influxes of Common Whitethroats are normally recorded in spring

On 14 April 2018, two Turtle Doves flew over the area of Tas-Silġ. During spring migration, Turtle Doves migrate over the Maltese archipelago between mid-April until the first week of May. Very often they arrive during the night, while others reach the Maltese shores during the following days.14

Between the third week of April and the first two weeks of May, further migratory species were recorded. On 22 April, a Whinchat and a Common Whitethroat were observed in the wetland of Marsaxlokk. A Spotted Flycatcher was also recorded in the first week of May. The ornithological list added a new specie with the sighting of an Icterine Warbler inside the wetland, feeding on insects adjacent to the tamarisk trees. Another one was sighted again in the same spot a week later.

The Black Winged Stilt was the first wader bird recorded in the spring migration, observed flying over the marshland. During the period under review, Common Sandpipers were recorded over a number of different days, with the first sighting recorded in late April. The highest count of five Common Sandpipers was registered on 29 April 2018. They were also recorded in singles until mid-May. One Wood

Sandpiper was recorded during the spring migration. A Grey Heron and an unidentified Plover were spotted in the last week of April, while a lone sighting of a Little Egret was recorded on 13 May.

Between 25 March 2018 and 17 June 2018, Yellow Legged Gulls were sighted almost weekly. In mid-April, a first year Slender Billed Gull appeared swimming close to the eroded part of the embankment. At the beginning of spring, the first Barn Swallow was recorded late in March, while the first Swift was noted in early April. Barn Swallows continued to be recorded until mid-May. The highest count of Hirundines was logged in the beginning of April. Swifts were observed until late June, reaching their peak on 10 June 2018. A Marsh Harrier was recorded in early spring and another two were sighted in the last week of April.

Between late March and late April, Zitting Cisticolas were spotted in singles. A pair of Zitting Cisticola had always been spotted from early May onwards. An average of three Sardinian Warblers had always been counted. On 25 May a leucistic Spanish Sparrow alighted on the shrubby glasswort vegetation.

28

Left: Icterine Warblers can replenish their fat reserves by feeding on insects, worms, and invertebrates and Right: Tree Pipits are migratory birds mostly common during Spirng migration

Conclusion

Throughout the last four years, three important aspects emerged. First, in ornithological terms, the marshland is a good refuge point for a different number of migratory birds, as they can rest and find food before continuing their perilous journey from Europe to Africa and vice versa. It is interesting indeed that the number of bird species expanded further after June 2018. Secondly, the place is important for wintering birds that usually migrate to milder temperatures to avoid freezing climates of the north. And thirdly, such a small wetland may also be a good ornithological place in terms of vagrant, rare and scarce birds as well.

Certainly, the present state of the wetland is not enticing. The public perception remains negative towards it as its current state is

Notes and References

1 10 September – 3 barn swallows and 17 September 2017 – 13 Barn Swallows.

2 Brown shrike was spotted by Benny Scerri.

3 Handbook of Birds of the World, Vol. 13, p.778. del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A. & Christie, D.A. eds. (2008) Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

4 Ibid., pg.778.

5 Identification Guide to European Species, p.217, Lars Svensson, Willow Warbler had yellow predominantly distinct streaks which suggest it is an adult bird.

Left: Common Swifts have mainly been registered in spring, but they have also been recorded in mid-summer and Right: The Blackcap is one of the migratory birds that occasionally winters in the area

degraded and inundated with human disturbances. More emphasis on the importance of this wetland is needed to raise awareness among environmentalist enthusiasts and the general public, which will ultimately lead to change the perception towards this tiny gem in the southern region of Malta.

Lastly, the salt marsh is deteriorating rapidly due to strong sea currents. Unless authorities act swiftly to protect it, the wetland will be lost forever, submerged under rising sea levels, and with it another valuable ecosystem and a habitat for the ever-declining bird species!

NB: All photos in this article were taken by the author except for the Brown Shrike photo as acknowledged. These pictures were taken in the wetland of Il-Ballut ta’ Marsaxlokk or other sites in Malta. Special thanks go to Mr Edward Bonavia (Secretary of Malta Rarities and Records Committee) and Mr John J. Borg (Heritage Malta Senior Curator of the National Museum of Natural History).

6 L-Agħsafar, pg.155, Joe Sultana & Charles Gauci.

7 Birdwatching done between 17:30 – 18:30.

8 ‘White wagtail roost count January 2019’, Birdlife Malta., p.3., Denis Cachia.

9 Birdwatching done between 17:30 – 18:30.

10 Birdwatching done between 17:30 – 18:30.

11 Meadow Pipits were recorded until 25 March 2018.

12 Spanish Sparrows, Sardinian Warblers and Zitting Cisticolas.

13 Collins Bird Guide, p.188, Lars Svensson.

14 L-Agħsafar, pg.132, Joe Sultana & Charles Gauci.

29

Hili Micallef

Painted in Colonial Mexico A Set of Seventeen

Joanna

Joanna

The history of Mexico covers a period of more than three millennia. First populated more than 13,000 years ago, the territory had a complex indigenous civilization before being conquered by the Spaniards in the 16th century. With the Spaniards absorbing the native people into Spain’s vast colonial empire, Mexico’s long-established Mesoamerican civilization became fused with the European culture.1

During the 16th century, European artists immigrated to Mexico to decorate newly established churches and complete artistic commissions. By the 17th century, a new generation of artists born in the Americas began to dominate the scene. Painters developed their own pictorial styles that reflected the changing cultural climate. The 18th century led to a period of artistic grandeur as local schools of painting were consolidated, new iconographies were invented, and artists began to group themselves into academies (Katzew, 2017, 16). Mexican artists still followed what was happening in Europe. The works of leading Italian and French painters, among others, became known to them through engravings (prints), copies and written accounts. Hispanic artists copied prints accurately or took specific figures which they used in new contexts, altering their meaning and interpretation (Mues Orts, 2017: 63-67). In Spanish colonial art, copying was not considered as lesser art, but more as ‘The Art of Two Artists’ (Katzew, 2017: 89-96).

One of the great Mexican painters of the second half of the 18th century was Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz (1713-1772). A mestizo, according to the system of racial classification of the time - that is having a Spanish and a

native American parent - born in 1713 in San Miguel de Allende (Guanajuato). At the age of sixteen, he moved from his native hometown to Mexico City, and apprenticed with Jose de Ibarra (1685-1756), the most important artist of his generation (Katzew, 2017: 264).

Morlete Ruiz was a director of a group of Mexican artists, who in the 1750s worked together to elevate the painting profession and receive royal support for an academy they established (Katzew, 2017: 89). Being part of the academy gave Morlete Ruiz a place among the Spanish elite in Mexico. Both the Viceroy Carlos Francisco De Croix, Marquis of Croix (1699-1786) and Viceroy Antonio Maria de Bucareli y Ursúa (1717-1779) commissioned work from him.

31

Viceroy Carlos Francisco De Croix, Marquis of Croix (1699, Lille, France – 1786, Valencia, Spain), by Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz, 1766, Museo Nacional de Historia, Mexico City

The Malta connection

Carlos Francisco De Croix was a Spanish General and Viceroy of Mexico between 1766 and 1771. He turned over his office to Antonio María de Bucareli y Ursúa in September 1771 and returned to Spain. Fra Antonio María de

Bucareli y Ursúa, was a Spanish military officer, Governor of Cuba, and Viceroy of Mexico between 1771 and 1779. He was also Knight of Justice of the Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of St John.

In Bucareli y Ursúa’s probate inventory of 1779, a set of seventeen paintings showing ports of France and two paintings showing scenes from Mexico, complete with gilded frames, all [valued at] 1,600 pesos, were listed among his belongings. This inventory most likely corresponds to a collection of paintings attributed to Morlete Ruiz which are found in Malta. It is plausible that after Bucareli y Ursua’s death, the Order inherited these paintings which were shipped across the Atlantic to the Order’s headquarters, that is Malta, were they have remained ever since.

This set of seventeen paintings, depicted between 1769 and 1772, is located between San Anton Palace in Attard and Verdala Palace in Buskett, limits of Siġġiewi. All the paintings are of similar size, approximately 152.5 by 99cm, and they all have similar gilded decorative frames, suggesting they were meant as a set. Twelve of the paintings show ports of France based on engravings after paintings by Claude Joseph Vernet (1714-1789). Another three show scenes of Florence based on engravings after drawings by Giuseppe Zocchi (circa 17111767). The last two paintings are original paintings of Mexico City.

It is unlikely that Bucareli y Ursúa commissioned these paintings. The paintings date from 1769, that is before Bucareli y Ursúa arrived in Mexico. Morlete Ruiz must have started painting the set earlier and completed it after Bucareli y Ursúa’s arrival. It is possible that these paintings were intended for a European

32

Above: Deuxième vue de Toulon: vue du la ville et de la rade, by Joseph Vernet (1714-1789), 1756, oil on canvas, 165 x 263cm Musée de Louvre, Paris

Below: Deuxième vue de Toulon: vue du la ville et de la rade, engraving by Charles Nicolas Cochine the Younger (1715-90) and Jacques Philippe Le Bas (1707-83), 1762, after the painting by Vernet, École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts (ENSBA), Paris

market. In the 18th century, artists in New Spain often inscribed the mention of Mexico as the place of origin on works bound for Europe, as a sign of pride in their artistic tradition. Whatever the circumstances, Bucareli y Ursúa must have acquired this set of paintings, as is attested in his probate inventory. Katzew suggests the possibility that Bucareli y Ursúa asked Morlete Ruiz to add the last view, Mexico City’s Plaza del Volador, which he completed in 1772, the year of his death. (Katzew, 2017: 92).

depicting ports of France. These paintings were commissioned for King Louis XV by Abel-François Poisson (1727-1781), Marquis of Marigny, director general of the King’s buildings. The paintings were intended to document and promote French commerce and naval services. In his superbly executed paintings, Vernet emphasized the country’s economic prosperity by featuring the ports as the locus of trade, regional and social diversity, and marine proficiency.

Ports of France

Between 1754 and 1765 the French artist Vernet produced a series of fifteen paintings

With the goal of making the paintings more broadly known across France and internationally, the Marquis of Marigny asked Charles Nicolas Cochine and Jacques Philippe Le Bas, to create a series of prints after them. Between 1758 and 1767, Cochin and Le Bas

33

View of the Town and Port of Toulon, by Juan Patrice Morlete Ruiz (1713-1772), San Anton Presidential Palace, Malta

worked directly from the paintings, employing a mirror to render the images in the correct orientation and capture the rich details.

Morlete Ruiz painted a very accurate representation of Vernet’s paintings. However, the colours differ from Vernet’s paintings.This demonstrates that Morlete Ruiz based his painting on the prints and not the original paintings. Also, to note is the inscription in the lower part of Morlete Ruiz’s paintings. It translates in Spanish almost verbatim the inscriptions in the Cochin and Le Bas etchings, stating the location of the port being depicted and that the paintings are copies based on paintings by Claude Joseph Vernet. It also indicates that they were produced in Mexico by Morlete Ruiz from a print and the manufacturing date.

What is noteworthy is that Morlete Ruiz had access to the prints barely two years after they were completed. Perhaps Marquis of Croix, of whom Morlete Ruiz created a portrait for the viceregal palace, who was of French origin, brought with him to Mexico a suite of the freshly minted prints after Vernet’s set (Katzew, 2017: 91). By the time Marquis of Croix arrived in Mexico, only twelve prints were issued, therefore, it seems logical to conclude that Morlete Ruiz’s collection in Malta is complete.

Scenes of Florence

While he was painting the ports of France, Morlete Ruiz also produced at least three paintings showing vedute (views) of Florence,

34

Painted in Colonial Mexico: A Set of Seventeen

View of the Church and Plaza of Santa Croce with the Festa del Calcio, by Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz, 1770, San Anton Presidential Palace, Malta

modeled after compositions by the Italian artist Giuseppe Zocchi. As stated in an inscription, in the lower part of these paintings, they were painted in Mexico based on lithograph prints.

Zocchi was an Italian painter and printmaker, active in Florence, and best known for his vedute of the city. Zocchi’s patron, the Marchese Andrea Gerini (a Florentine aristocrat and art collector), commissioned him to record all the famous Florentine landmarks, which he did in a series of drawings, now in New York’s Pierpont Morgan Library. Zocchi finished the project by the end of 1741, when his compositions were sent off to the best engravers throughout Italy. Zocchi ably produced representations of landscape and architecture as well as important Florentine

events, with considerable attention to detail, which makes the series a precious document of 18th-century Florence.

Morlete Ruiz followed the etchings after Zocchi rather closely, same as in the ports of France, with the inscription in the lower part of the paintings translating in Spanish almost accurately the Italian inscriptions on the prints, with the addition that they were painted in Mexico by Morlete Ruiz and the manufacturing date.

Two of the Florentine vedute show Piazzas enlivened by major Florentine events. One shows the Piazza and Basilica di Santa Croce and portrays two main events, Carnival and the Festa del Calcio.2 The origins of carnival in Florence date back to the 15th century.

35

View of the Church and Plaza of Santa Maria Novella with the Festa della Corsa de’Cocchi, by Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz, 1770, San Anton Presidential Palace, Malta

During carnival people would wear masks and gather in Piazza Santa Croce (which is still one of the main spots of Florence’s Carnival). The painting provides vivid evidence of 18thcentury carnival masks and costumes, some of them quite intriguing. The Festa del Calcio is a traditional football game dating back to the 15th century, a brutal mix of football, rugby and wrestling. It became very popular, especially during Carnival, attracting huge crowds. Gradually the Festa del Calcio became obsolete, the last known match was played in January 1739 in Piazza Santa Croce (Vandeville, 2014, Bresford, 2015). Interestingly Zocchi’s drawing shows the Festa del Calcio in 1738, that is a year before it was discontinued. It is not until the 1930s that it became popular once again,

renamed Calcio Storico Fiorentino and fought in medieval costumes in Piazza Santa Croce in June ever since.

The other shows the Piazza and Basilica di Santa Maria Novella with the Festa della Corsa de’ Cocchi. The Corsa de’ Cocchi, also known as Palio dei Cocchi, was a race with horsedrawn carriages similar to Roman chariots. The Corsa de’ Cocchi was set up in the 16th century, the carriages (or cocchi) revolved around two marble obelisks, still present in the piazza to date. The palio was held on 23 June, the eve of the feast of St John the Baptist, patron saint of Florence, a day before the annual final of the Festa del Calcio, until the mid-1800s.

Painted in Colonial Mexico: A Set of Seventeen

36

View of Plaza Mayor of Mexico City, by Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz, 1770, San Anton Presidential Palace, Malta

Mexican Plazas

Until 1769, Morlete Ruiz painted mostly portraits and secular paintings (Retana Márquez, 1996: 116-117). The ports of France and Florentine vedute introduced him to a new style of genre paintings. Consequently, he produced the two original paintings View of Plaza Mayor of Mexico City, dated 1770, and View of Plaza del Volador of Mexico City, dated 1772. These Mexican plazas, with their receding perspective, piazzas surrounded by buildings and human activities, to a certain extent, follow Zocchi’s vedute. However, they are seen from a higher vantage point, they show a bird’s-eye view of the respective plazas.

Hamman explains that during the

18th century, there was an increased production of city views of Mexico City (Hamman, 2015: 31). These city views were typically rendered as birds’-eye view and combined two disciplines: art and cartography – the practice of drawing maps (Hamman, 2015: 32-33). This dual quality of both map and landscape can be seen in Morlete Ruiz’s paintings, showing that he was also abreast of his local traditions. The buildings in the respective plazas are numbered. At the bottom of each painting there is a legend, identifying all the important buildings with reference to the numbers on the paintings. Moreover, these paintings are not just city views but also combine human activity. The plazas are populated with figures that represent social diversity, with depictions

37

View of Plaza del Volador of Mexico City, by Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz, 1772, San Anton Presidential Palace, Malta

of both the social elite and ordinary people. Public spaces providing lucid information on 18th-century Mexican portrait of society; this is where all castes and social classes mix.

Morlete Ruiz first painted Plaza Mayor, Mexico City’s main plaza, now the Plaza de la Constitución, also known as the Zócalo. This location has been a gathering place for Mexicans since the Aztec times. The site for many Mexican ceremonies such as the swearing of viceroys, royal proclamations, military parades, Independence ceremonies and religious events. In the distant background, Morlete Ruiz’s shows the distinct profile of the Iztaccihuatl dormant volcano, with its snowy peak. A topographical feature that allows the viewers to situate themselves in relation to Mexico’s regional environ. In the center, there is the Viceregal Palace and to the left the Cathedral. Today Plaza Mayor is still bordered by these important buildings of the colonial era. Since this plaza seated the Viceroyalty of New Spain and the Archbishopric of Mexico, it was the center of political and religious institutions, but it was also the center of Mexico’s economic activity and the residence of social elites in colonial Mexico.

A Viceregal procession, with men on horseback and horse-drawn carriages, is proceeding from the Viceregal Palace towards the Cathedral, establishing a powerful visual connection between State and Church. The Crown Battalion stands guard in the middle, while ordinary people go about their everyday life. To the right, soldiers guard the Parián, an enclosed marketplace, its presence signals the importance of the plaza as a major commercial hub.3 Morlete Ruiz does not show the Baratillo (open market) de la Plaza Mayor, often seen

in contemporary paintings of this plaza. Makeshift stalls overrun the plaza over much of the 17th and 18th century. In 1760, the open market was described as extremely disordered and there were several attempts to reform marketplaces throughout Mexico City and to clear Plaza Mayor (Exbalin 2015, 12) (Douglas 2013, 17). While it is possible that Morlete Ruiz painted Plaza Mayor when it was temporarily cleared, it is also plausible that he chose to omit the Baratillo to represent a more orderly view of the city.

Two years later, Morlete Ruiz painted another important square in colonial Mexico, Plaza del Volador, a square located southeast of Plaza Mayor. The Viceregal Palace, whose façade is in Plaza Mayor, had an exterior side in the former Plaza del Volador. The space once occupied by the Plaza del Volador is currently occupied by the Supreme Court of Justice. During the Colonial period, the square had many uses, it was the center of key public ceremonies, hosting a range of festivities, such as bull fighting, and the ritual ceremony of the Voladores (rite of flying), to which the plaza owes its name. But when it was not being used for such events, the square became a big flea market. It was known as a place where people from all racial and social backgrounds commingled, and where all sorts of crimes occurred. The composition, however, shows an orderly market with an abundance of fruits and vegetables. In the very forefront of the painting there is the Real Acquia (Royal Canal), the waterway which supplied daily needs to the center of the city. The waterway is jam-packed with canoes loaded with fruit and vegetables. Today, instead of the Royal Canal there is Corregidora Street. Depicted to the left,

Painted in Colonial Mexico: A Set of Seventeen 38

there is the Royal and Pontifical University, of which today only the street that bears its name remains.

Both the plaza Mayor and the plaza del Volador represent idealized views of Mexico City, systematized, peaceful and prolific. Katzew explains that “by depicting New Spain in its best light, the works convey a particular message about life in viceroyalty to their intended European audience, fulfilling a propagandistic function akin to that of Vernet’s set” (Katzew, 2017: 96).

This research was carried out during the conservation restoration treatment of this set of seventeen paintings, unique to Malta, in collaboration with LACMA (Los Angeles County Museum of Art). The conservation work was undertaken by Heritage Malta over a span of four years.

Notes and References

1 Mexico was part of the Spanish Empire between 1521 and 1821.

2 In Morlete Ruiz’s painting, one can see the original brick façade of the Basilica di Santa Croce before the 1860s neo-Gothic marble façade by Jewish architect Niccolo Matas.

3 Built between 1695 and 1700, the Parián, was used as a set of shops to warehouse and sell products brought by galleons from Europe and Asia.

Bibliography

BRESFORD, C. 2015. Calcio Storico Fiorentino, Available at: https://gentlemanultra.com/2015/10/12/calcio-storicofiorentino/[accessed on 24 October 2018]

CONTINI, R. Giuseppe Zocchi, Available at: https://www. museothyssen.org/en/collection/artists/zocchi-giuseppe

[accessed on 24 October 2018]

CORDERO, S., La Suprema Corte de Justicia, su Transito y su Destino, Cap. 11 La Plaza del Volador, Available at: https:// archivos.juridicas.unam.mx/www/bjv/libros/2/931/7.pdf

[(accessed on 13 September 2018]

CRUZ LARA, A. 2014. ‘De Sevilla al Museo Regional de Guadalajara: Atribución, valoración y restauración de una serie pictórica franciscana’, a PhD dissertation submitted to the Universidad Nacional Autónoms de México

DOUGLAS, R., ‘4. The Marvelous and the Abominable the

Intersection of Formal and Informal Economies in Eighteenth-Century Mexico City’, Diacronie Studi di Storia Contemporanea, N. 13 | 1|2013 Contrabbandieri, pirati e frontier

EXBALIN, A. 2015, ‘The urban order in Mexico. Actors, regulations and police reforms (1692-1794)’, Nuevo Mundo

GONZALBO, P. E. et al, 2008, ‘Nueva Historia Minima de Mexico Ilustrada’, Primera edición, Mexico

HAMMAN, A. C. 2015, ‘Eyeing Alameda Park: Topographies of Culture, Class, and Cleanliness in Bourbon Mexico City, 1700 – 1800’, a dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the School of Art, The University of Arizona

KATZEW, I. 2004. Casta Paintings: Image of Race in EighteenthCentury Mexico, New Haven: Yale University Press

KATZEW, I. 2009. New Acquisitions in Spanish Colonial Art, Unframed, Los Angeles County Museum of Art blog. Available at: http://unframed.lacma.org/2009/03/17/ french-harbors-painted-in-new-spain [accessed on 6 June 2017]

KATZEW, I. 2011. New Acquisition: Three Casta Paintings by Juan Patricio Morlete’, Unframed, Los Angeles County Museum of Art blog. Available at: https://lacma.wordpress. com/2011/04/21/new-acquisition-three-casta-paintingsby-juan-patricio-morlete-ruiz/ [accessed on 6 June 2017]

KATZEW, I. 2013. Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz: Conservation of Ports of France, Los Angeles County Museum of Art video, Available at: http://www.lacma.org/video/juan-patriciomorlete-ruiz-conservation-ports-france [accessed on 10 August 2015]

KATZEW, I. 2014. ‘Valiant Styles: New Spain Paintings 1700-85’, Painting in Latin America, 1550-1820, Luisa Elena Alcalá and Jonathan Brown, New Haven: Yale University Press

KATZEW, I. 2017. Painted in Mexico 1700-1790: Pinxit Mexici, DelMonico Books.Prestel Munich, London, New York

MUES ORTS, P. 2017, ‘Illustrious Painting and Modern Brushes, Tradition and innovation in New Spain’, in Painted in Mexico 1700-1790: Pinxit Mexici, DelMonico Books/ Prestel Munich, London, New York

RAMOS, J. O. 2013, ‘Los mercados de la Plaza Mayor en la Ciudad de México’, Centro de Estudios mexicanos y Centroamericanos, Mexico

RETANA MÁRQUEZ, Ó. R. 1996. Las pinturas de Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz en Malta, Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, Vol. 17, 68: 113-125. México: Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas

SANCHIZ, J. 2013. El grupo familiar de Juan Gil Patricio Morlete Ruiz, pintor novohispano, Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, Vol. 35, 103: 199-230. México: Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas

STANISLAI, S. Il Calcio Storico Fiorentino, Available at: https:// www.nikonschool.it/life/calcio-fiorentino.php [accessed on 24 October 2018]

TROUG, A.R. 2015. Giuseppe Zocchi (near Florence 1711/71767 Florence), Florence, a view of the Arno from the Porta San Niccolò, Available at: https://alaintruong2014. wordpress.com/tag/giuseppe-zocchi/ [accessed on 24 October 2018]

VANDEVILLE, E., 2014. Calcio Storico, Football’s Brutal Ancestor, Available at: http://www.italianinsider.it/?q=node/2025 [accessed on 24 October 2018]

39

David Frank Buġeja

Tim Padfield’s Contribution to Conservation

Everything started from a website that proved to be a turning point in my professional and personal life. When I was reading for my master’s degree course in 2003, I was lectured by Bent Eshøj, former Head of Master Education and Research Lab at the School of Conservation in Copenhagen, Denmark. Upon noting my growing interest in museum microclimates and on how to protect paintings from unstable relative humidity, Bent strongly advised me to visit the following hyperlink: www.conservationphysics.org.1