Winter 2014 Heritage

The war at home

6 On the home front

Families left behind when their menfolk marched off to war fought battles of their own

8 A matter of principle

The treatment of conscientious objectors was often just as barbaric as the war itself

14 Coming & going

Buildings were established to meet the needs of soldiers leaving to fight and returning to recover

20 A safe haven

With strict discipline and rigorous training, the army camp at Featherston turned civilians into soldiers

24 The business of war

Increased demand for goods to feed the war machine meant unprecedented profits for some of our home-grown industries

Remembering the war

30 Saddled up & digging for victory

Three unlikely and little-known fighting forces contributed their special skills to the war

32 Peace in our time

When the celebrations were over, communities built memorials that would be lasting reminders of victory and peace

38 Hill of memories

The upgrading of Wellington’s National War Memorial Park has uncovered tangible reminders of its military past

42 In return for service

Established to support those returning from war, the RSA clubs have lost none of their relevance

46 Lest we forget

Follow the trail around Auckland’s monuments, buildings and public spaces that pay tribute to the soldiers who left home and didn’t always come back

54 The forgotten men Remembered elsewhere, isn’t it time the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade was commemorated at home?

Columns

3 Editorial

4 About this issue

5 Your letters

52 Books

A selection of new books approaches the subject of war from several angles

Heritage

Issue 133 Winter 2014

ISSN 1175-9615 (Print)

ISSN 2253-5330 (Online)

Cover image: Red poppy (www.shutterstock.com)

Editor Bette Flagler, Sugar Bag Communications

Subeditor

Jane Turner, Sugar Bag Communications

Advertising Co-ordinator

Sonia Barrett

Design

Amanda Trayes, Sugar Bag Communications

Publisher

Heritage New Zealand

Heritage New Zealand magazine is published quarterly by Heritage New Zealand. The magazine has an ABC audited circulation of 13,102 as at 30 June 2013.

The views expressed in the articles are those of the contributors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Heritage New Zealand.

Advertising

For advertising enquiries please contact the Advertising Co-ordinator

Phone: (04) 494 8034

E-mail: advertising@historic.org.nz

Subscriptions/Membership

Heritage New Zealand magazine is sent to all members of Heritage New Zealand. Call 0800 802 010 to find out more.

Tell us your views

At Heritage New Zealand magazine we enjoy feedback about any of the articles in this issue or heritage-related matters.

E-mail: The Editor at heritagenz@gmail.com

Post: The Editor, c/- Heritage New Zealand National Office, PO Box 2629, Wellington 6140

Feature articles: Note that articles are usually commissioned, so please contact the Editor for guidance regarding a story proposal before proceeding. All manuscripts accepted for publication in Heritage New Zealand magazine are subject to editing at the discretion of the Editor and Heritage New Zealand.

Online: Subscription and advertising details can be found under the Publications section on the Heritage New Zealand website, www.heritage.org.nz Online subscriptions are available through Zinio, http://nz.zinio.com

The war effort

Two years ago we began talking about how Heritage New Zealand magazine would commemorate the centenary of World War I. We knew there would be dozens (maybe even hundreds) of books published about the war and that the Ministry for Culture and Heritage was setting up WW100 as New Zealand’s World War I centenary programme (visit it on www.ww100.govt.nz). We weren’t confident that a quarterly publication of only 56 pages could do it justice when individuals and organisations far more expert were doing such amazing work.

In an effort to stick to our knitting, we decided to focus on how the war over there affected life and place over here. We were also smart enough to know that the others knew much more than we did so we approached them for help. Thank you to everyone who assisted us with the stories and images that follow.

In particular, I’d like to extend deep gratitude to Jock Phillips, historian and editor at the Ministry for Culture and Heritage, who

served as our invaluable fact-checking eyes. He not only was available as a resource for writers but read all the copy and provided helpful corrections and suggestions. I’d also like to thank historians Imelda Bargas, Tim Shoebridge and Gavin McLean, also from the Ministry for Culture and Heritage, for their assistance.

I must send an equally huge bouquet to Glyn Harper, Professor of War Studies at Massey University. Glyn, who is an expert on World War I history and is part-way through the publication of at least a dozen books about the war, took time out of his busy schedule to make himself available to almost all of our writers. We are grateful to Glyn and apologetic for taking so much of his time. Massey’s James Watson, a Professor of History, was also instrumental in this publication. We hope you enjoy reading this commemorative issue.

Bette Flagler EditorSupporters of Heritage New Zealand

We thank all members for their commitment to our work and acknowledge the following Corporate Members:

Antigua Boatsheds

Aon New Zealand

Architectural Building Conservation

Holmes Consulting Group

JR Webb & Son (1932) Ltd

Maynard Marks Ltd

Prendos New Zealand Ltd

Resene Paints Ltd

Salmond Reed Architects

The Fletcher Trust

WT Partnership NZ Ltd

Thank you to all our members and supporters who have made donations to Heritage New Zealand recently, a large number of whom generously supported our appeal for Antrim House. Many of those individuals are gratefully acknowledged elsewhere in this magazine.

We would particularly like to thank the following people for their generosity;

David & Genevieve Becroft Foundation

Mr A & Mrs M Bloomer

Mrs E Leary-Taylor

Mr L R Smith

Without the support of the communities in which we operate and the funders that invest in those communities, we are severely restricted in the work we can achieve.

We are therefore appreciative of recent grants or funding from the following organisations:

Lion Foundation

Infinity Foundation

Pelorus Trust

If you are involved in a grant-making organisation and believe that there is scope to work together for the benefit and protection of New Zealand’s heritage, please get in touch with the Funding Development Manager (contact details below).

Leaving a gift in your will is one of the single best ways of supporting our work and making a lasting difference for the heritage of New Zealand. Please phone 0800 HERITAGE (0800 437482) to speak with Brendon Veale, Funding Development Manager, if you would like more information about how you can support our work in this way, or visit www.heritage.org.nz and go to the ‘Get Involved’ section of the website.

Heritage This Month – subscribe now

Keep up to date by subscribing to our free e-newsletter Heritage This Month. Contact membership@ heritage.org.nz and ask to be included on the e-mail list.

A reader’s letter

As a long-time (67 years) bach occupier on Rangitoto Island, I was interested in reading Yvonne van Dongen’s article (Issue 131). It certainly gave the island, an Auckland Iconic Destination (according to the Department of Conservation), welcome publicity. I was, however, disappointed by some of the errors in the text and felt that Yvonne could have consulted with locals. The lifetime leases she hinted at were in fact issued in 1956, not 1937. The swimming pool was built by inmates of Auckland Prison, not by the bach owners, and the “electric” lights were powered by a petrol generator, there being no electricity on the island, then and now.

But the writer’s greatest mistake was perpetuating a popular myth by implying that the community on the island is a thing of the past. Far from it. All the baches under family guardianship are used, most on a regular basis. The population is not as large as it was, but on a long weekend and over the summer holidays 20 to 30 people from the Rangitoto Wharf bach settlement (one of three on the island) get together for evening drinks after the last ferry has left for Auckland with its load of day visitors. The bach families still pursue the same activities as their predecessors: fishing, walking, chatting, beachcombing and boating.

In the same issue I noticed the article on the Cape Campbell lighthouse. This mentioned that the structure is one of only three striped lighthouses in New Zealand. Not true. The Rangitoto Island lighthouse in Auckland’s Hauraki Gulf has been striped since ages ago!

John Walsh, Vice Chair, Rangitoto Island Bach Community Association

JASPER BERLIN

Illustrator

London in the 1970s was awash with ludicrous fashion and mullets. Jasper Berlin had both. He worked in the oil industry which, while lucrative, was not the life for him. Drawing was what he was good at. A commission for a recruitment ad for the navy was his introduction to commercial illustration. Jasper found his way to New Zealand in 1987 and is one of our most in-demand editorial illustrators.

About the work he did for this issue (The business of war, page 24), Jasper says, “This explores the local economic landscape during this period. The illustrations reflect the bucolic nature of New Zealand’s home front, rather than the charnel house awaiting the troops in Europe.”

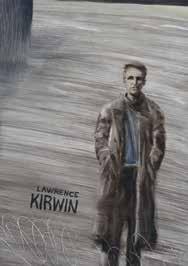

BOB KERR

Illustrator

Bob Kerr paints landscapes of conflict. He first read Archibald Baxter’s book We Will Not Cease in the Tokoroa High School library, describing Baxter’s and Mark Briggs’ experiences of Field Punishment No. 1 during World War I, and thought it must be a work of fiction – a New Zealand government wouldn’t torture its own citizens. He has painted a series about the police invasion of Maungapohatu in 1916 and another on the Waihi gold strike of 1913, and most recently has illustrated a children’s book, Best Mates, about three friends who go to Gallipoli. For this issue he provided the illustrations for A matter of principle, see page 8.

Heritage New Zealand Directory

Heritage New Zealand is the leading organisation for the care and protection of New Zealand’s historic places.

National Office

PO Box 2629, Wellington 6140

Antrim House, 63 Boulcott Street, Wellington 6011

Phone: (04) 472 4341

Fax: (04) 499 0669

E-mail: information@heritage.org.nz

Go to www.heritage.org.nz for details of offices and historic places around New Zealand which are cared for by Heritage New Zealand.

Local Authority Members

Auckland Council

Bay of Plenty Regional Council

Central Hawke’s Bay District Council

Dunedin City Council

Far North District Council

Gore District Council

Hamilton City Council

Hauraki District Council

Invercargill City Council

Manawatu District Council

Marlborough District Council

Masterton District Council

Matamata-Piako District Council

Nelson City Council

Porirua City Council

Rotorua District Council

Ruapehu District Council

Selwyn District Council

South Taranaki District Council

Tararua District Council

Tasman District Council

Thames-Coromandel District Council

Timaru District Council

Waipa District Council

Waitaki District Council

Wanganui District Council

Western Bay of Plenty District Council

Sergeant Eric Wanden, pictured with two friends, was 21 years old when he left for the war in the Dardanelles. He was soon hit by a bullet which damaged his lower jaw. He came back to New Zealand on the troopship Willochra, regained fitness and returned to Egypt where he was promoted to second lieutenant with the 10th Squadron, Canterbury Mounted Rifles.

Sergeant Charles Frederick Scrimgeour describes how Eric met his fate in Palestine: “On the 25th September (1918) we were at a redoubt just before Amman. When galloping into action I saw

him hit in the heart by a rifle bullet and killed instantaneously. He was buried that afternoon near the spot where he fell…”

Studio portraits of soldiers in uniform typically featured solemn faces. That is what makes this postcard of three who have swapped hats rare. The New Zealand officer Will (seated), a second lieutenant in the 1st Canterbury Regiment, is joined by an Englishman (right) from the Somerset Light Infantry (wearing Will’s lemon squeezer hat) and a Scotsman.

See more postcards at http://100nzww1postcards.blogspot. co.nz/

THANKS FOR YOUR SUPPORT

Over recent weeks our supporters have written to us about our change of name. “It’s about time” was a common theme from many, recognising that historic places are one part of a much wider range of our work. And thanks to those who asked for more information about why we’ve made this change.

While our name has changed, our focus on heritage remains at the heart of what we do – and at the heart of our beloved magazine too.

www.heritage.org.nz

On the HOME FRONT

Families left behind when their menfolk marched off to war fought battles of their own

WORDS: KATE HUNTER

In August 1914 Teddy Reynolds of Lower Hutt wrote to Lord Liverpool, Governor of New Zealand: “Dear Governor, Wold you let me come to the war. I am eight yers old. I am in the first standard I want to come to the war my father is going to the war and i wood like to go and fite for our country’ [sic]. Teddy’s father William had enlisted in August, which was unusual. It was much more common for children to farewell their brothers and uncles, and for parents to face their sons’ enlistments.

Railway worker Len Hart wrote to his father from camp, explaining his decision to join up: “I feel certain that you would

not be put out by it”. Samuel Hart replied: “Well Len, I feel proud of being your father. Good men like you are going to save the Empire.”

Len knew that his mother’s response might not be so positive, admitting “she would not perhaps be exactly pleased”.

In the end Caroline Hart must have resigned herself to the war’s pull because both of Len’s brothers, Harry and Adrian, enlisted as well and their sister Connie took advantage of new wartime work to become a typist.

The Great War changed the lives of families all over New Zealand. While it risks being a cliché, the notion that no family was untouched by it is perhaps

quite close to the truth. The war infused newspapers, workplaces, classrooms and Sunday sermons. Topicals – short news films – at the cinema preceded every feature film and patriotic fund-raising became the focus of almost every leisure activity.

Everyday, innocent pastimes became imbued with new meanings so that a game of rugby raised questions about the loyalty of every fit man on the field, and conducting a Lutheran church service in German was regarded as so dangerous the community changed to English within weeks of the war’s declaration. New Zealand may have been as far from the battlefields of Europe as it was possible to be, but the war was very real for New Zealanders.

The country was surprisingly militarised in 1914. Although there was no standing army, there was a pool of 25,000 reservist territorials created by the compulsory military training for boys and young men that had been enacted in 1909. Raising a volunteer force in the first months was not difficult and the main body of 8000 men embarked in October 1914.

The appearance in New Zealand newspapers six months later of the casualty lists from the Gallipoli campaign sobered the enthusiasts and confirmed the predictions of the war’s opponents. The return of the troopship Willochra in July 1915 was also a significant event because it carried the first of the eventually 40,000 wounded. Recruits and their families could no longer be innocent of what awaited them in the “European war”, and this was still eight months before the New Zealand Expeditionary Force was deployed on the Western Front.

However, men continued to volunteer, in waves rather than as a steady stream. Their motives were various; a sense of duty drove many, including the young parliamentarians William Downie Stewart and Thomas Seddon, who enlisted together in 1915 so as not to upset the balance in Parliament.

Personal conviction also motivated some men in the Labour movement who felt they could not oppose the introduction of conscription in August 1916 if they were not prepared to volunteer themselves. For many others, the army offered travel,

steady pay and allowances and generous pensions in the event of disability or death. Few workplaces offered such benefits and some industries, such as mining and forestry, were just as dangerous.

Communities all over the country threw themselves into the voluntary efforts to support “our boys”. Women and children learned to knit; even children could manage pyjama cords that were only seven stitches wide but a seemingly endless 150 centimetres long. Groups of women sewed in their lunch hours at work or in the evenings in homes and halls, and men’s sports teams rolled bandages and assembled packing crates.

School activities became strongly focused on fund-raising galas, bottle drives, knitting and sewing. School prize winners gave up their medals and books in favour of donating the money to soldiers’ funds, or the school boards decided for them –

decisions that still rankled many years later. Those who were children during the war recall the enormous fun of peace festivities and school fund-raising, but also the cancelling of birthday parties; New Zealand was “very Spartan”.

The enlistment, then conscription, of more than 100,000 men had serious consequences for a large number of families and the decision to enlist was often made around the kitchen table. Most rural and working-class families in the 1910s were reliant on the earnings and labour of all adult family members, with men commanding wages twice as high as women’s.

Leslie Adkin’s Horowhenua family decided that one of their sons needed to remain at home to help run the farm and Leslie, although the elder, was a more experienced farmer than the younger Gilbert.

It was clear from the appeals against conscription, heard by local military service boards from late 1916 onwards, that there

were many cases where a man’s enlistment would cause undue hardship to his family.

Ernest Napier’s argument against his call-up was that he contributed 32 shillings to the family each week which was far more than he would be able to allot from his weekly army pay of 35 shillings. The board was not satisfied with this appeal and granted Ernest exemption from service only when the most intimate details of his domestic situation became clear (and were subsequently published in the newspaper): his mother was an amputee and his father “suffered from such severe rheumatism that he was unable to dress himself”.

Few of these appeals were granted immediately; it was more common for the board to give a man a few months’ delay so he could put arrangements in place.

The absence of soldier relatives could put pressure on the women of farming families in particular.

Wairarapa girl Katarina Te Tau,

aged 15 at the outbreak of the war, recalled bitterly that she had “a hard working life because my elder brother... was enlisted into the war and my dad was growing wheat by the acre, acres and acres of it. I was the eldest one, so I had to give up school and help dad.”

For many families, the absence of kin was not just temporary; by the end of the war 18,000 men were dead and thousands more died in the 1920s. The influenza endemic of November 1918 claimed 8600 lives, adding to the trauma of the war.

Featherston farmer Harry Whishaw twice survived being wounded at Gallipoli but was killed in action at Armentières in 1916. Harry’s brother Bernard and their sister Mabel also served. Bernard, the youngest child of the family, enlisted in November 1915 but died of disease in Cairo in October 1918. Mabel served with the New Zealand Army Nursing Service at Featherston Military Camp where she was the night sister for three years. She remained responsible for their ageing mother, Kate, which prevented her volunteering for overseas service. She died of influenza in November 1918.

The toll on the families of thousands of wounded and dead men, as well as on their communities, was immense and long lasting. Patriotic societies, which had raised funds to support soldiers’ dependants during the war, continued to assist them for decades afterwards with hospital costs, rent and children’s education.

William Reynolds, whom Teddy had so desperately wanted to follow to war, returned to New Zealand in September 1916, discharged as unfit for further service. He had contracted rheumatic fever in Egypt, which made his joints swell painfully. It also probably damaged his heart and perhaps accounted for his premature death in 1930. He was not the father Teddy had farewelled, and life for the whole family was altered forever.

Everyday, innocent pastimes became imbued with new meanings

PRINCIPLEA matter of

The treatment of those whose beliefs did not allow them to fight was often just as barbaric as the war itself

As Britain’s most loyal colony, young New Zealand was keen to show its support for the war effort. Such was the enthusiasm that by the end of the first week of the war 14,000 had enlisted. Yet from the start there were voices of dissent, voices that grew louder as the war dragged on and the casualty list climbed.

By 1916 volunteers were drying up and the Government made the difficult decision to impose conscription to maintain New Zealand’s supply of reinforcements. The Military Service Act 1916 initially imposed conscription on Pakeha only, but this was extended to Maori in June 1917. More than 30,000 conscripts had joined the New Zealand Expeditionary Force by the end of the war.

For those who objected to conscription, whether out of sheer self preservation or on principle, there was often a heavy price to pay. Conscientious objectors faced hostility from the community, imprisonment and, in some cases, state-sanctioned torture. By the end of the war a total of 2600 conscientious objectors had lost their civil rights, including being denied voting rights for 10 years. The majority of dissenters were imprisoned and then court martialled at Trentham Military Camp near Wellington and sentenced to jail terms of between 11 months and two years.

In King and Country Call: New Zealanders, Conscription and the Great War, Paul Baker says that “imprisoned objectors faced a carefully modulated plan of punishment, which did not and could not distinguish between the ‘genuine’ and the ‘defiant’. An initial short period of detention and then a month’s imprisonment were aimed at breaking the will of those of minimal resolve.” In addition, hundreds were sent overseas in non-combatant roles while, in one instance, a group of 14 was singled out for particularly harsh treatment.

In July 1917 Colonel HR Potter, the Trentham Camp Commander, decided to deal with overcrowding in the prison by sending 14 of the objectors held there to Britain aboard the troopship Waitemata. Among

those sent were Archibald Baxter (father of poet James K Baxter) and socialist objector Mark Briggs. What followed has been described by historian David Grant as “the most astonishing recorded instance of statesanctioned cruelty which New Zealanders have ever inflicted upon fellow New Zealanders”. Aboard the Waitemata, and once overseas, the men were subjected to abuse, starvation and beatings. In October 1917, the 10 who remained defiant were sent to Étaples in France and warned that they would be shot if they continued to refuse to submit. Several relented and agreed to become stretcher bearers, while three were sentenced to hard labour.

MAORI OBJECTION TO THE WAR

Heritage New Zealand Kaihautu Te Kenehi Teira says Maori had mixed views about World War I. Some supported the war effort and rushed to join up. Others opposed the war as they did not want to fight for the British Crown, which was seen to have done much harm to Maori communities in the 19th century.

“Many Maori from the Waikato region in particular were opposed to the call to fight for the British King. The Waikato Wars of the 1860s, in which their land had been confiscated, had left them questioning why they should now be expected to fight for the British.”

Kingitanga leader Te Puea Herangi stated that her grandfather, King Tawhiao, had forbidden Waikato to take up arms again when he made peace with the Crown in 1881. She maintained that Waikato had its own king and didn’t need to fight for the British king.

At Waahi pa in November 1916, Defence Minister James Allen made a direct appeal to Waikato Maori, saying: “If you fail now, you and your tribes can never rest in honour in the days to come”. When this appeal failed, Allen supported the extension of military conscription to Maori in June 1917 but

decided to apply it to the Waikato Maniapoto district only.

Te Puea offered refuge at Te Paina Pa (Mangatawhiri) for men who opposed conscription and a crowd greeted police when they arrived there on 13 July 1917. The police waded into the crowd and began arresting men they believed to be objectors, including King Te Rata’s 16-year-old brother, Te Rauangaanga. Each of the seven men selected had to be carried out of the meeting house.

During the seizure, police stepped over King Te Rata’s personal flag, which had been protectively laid before his brother. The incident caused great offence to those gathered, but Te Puea calmed the crowd before blessing those seized. She told the police to let the Government know she was afraid of no law or anything else “excepting the God of my ancestors”.

The prisoners were taken to the army training camp at Narrow Neck, Auckland. Many were subjected, like other objectors, to severe military punishments to break their resolve and, when this failed, some were sentenced to two years’ hard labour at Mount Eden prison.

Archibald Baxter, Lawrence Kirwin, Henry Patton and Mark Briggs were subjected to repeated sentences of Field Punishment No. 1, part of which included what was known as “the crucifixion”. This involved being tied to a post in the open, with their hands bound tightly behind their backs and their knees and feet bound. They were held in this position for up to four hours a day in all weathers.

Baxter and Briggs also spent time in the trenches but remained defiant to the end, and both were eventually discharged on medical grounds and returned to New Zealand. Men like these were subjected to the most extreme measures, but all of those imprisoned faced a tough, carefully regulated plan of punishment designed to break their resolve. Historian David Grant says that conditions in prisons around New Zealand for objectors were harsh, but no harsher than those for ordinary prisoners at that time. “Difficult” prisoners like Baxter were subjected to solitary confinement and work in the quarries that was back-breaking.

The Wellington region contains some of the most significant sites attached to conscientious objection, although most no longer exist. Before their transportation overseas, Baxter and Briggs spent various times at several locations in Wellington, including Trentham Military Camp, Alexandra Barracks (near Mount Cook Prison), Terrace Jail and Mount Cook Prison, where the two met for the first time. During the seven weeks Briggs spent in prison he also met future

LABOUR AND OPPOSITION TO CONSCRIPTION

The West Coast of the South Island, with its large Irish population and entrenched tradeunion tradition, was a stronghold for the anti-conscription movement. It is also recognised as the key location in the birth of the New Zealand Labour Party which was formed in 1916, just months before the introduction of conscription.

In terms of built heritage, it is hard to look past the Runanga Miners’ Hall (Category 1) for its symbolic attachment to conscientious objection. While the hall is a replacement (the original was built in 1908 and burned down in 1937), as Heritage New Zealand Heritage Advisor Robyn Burgess notes, the hall and its predecessor have a “strong and lasting connection” to some of the key figures in the rise of the Labour Party, of whom many were the most vocal opponents of conscription.

Several Labour leaders were arrested for sedition, including prominent Runanga unionist Bob Semple, who was later a cabinet minister in the first Labour Government. Patrick (Paddy) Webb, the MP for West Coast, lost his seat due to his anticonscription stance and went to jail but was re-elected while serving his sentence. He went on to become a minister in the first Labour Government.

For those who objected to conscription... there was often a heavy price to pay

Prime Minister Peter Fraser, imprisoned for speaking out against conscription.

In 1930 the Mount Cook Prison building was demolished to make way for a new National War Memorial and a National Art Gallery and Dominion Museum, which was completed in 1936 and is now part of Massey University’s Wellington campus.

Only members of religious groups that had, before the outbreak of war, declared military service “contrary to divine revelation” could be exempted from service. Many of these religious conscientious objectors were sent to Weraroa State Farm to work out their military service. Known then as Weraroa Experimental Farm, the site is now a Category 1 Historic Place. Heritage New Zealand Heritage Advisor Natasha Naus says its association with conscientious objection “provides an interesting moment in the military mobilisation of New Zealanders during World War I and the treatment of those who refused to fight”.

HOW TO MEMORIALISE THE “SHIRKERS”?

For much of the 20th century they were reviled as shirkers and cowards, unworthy of citizenship, so the fact that New Zealand has no formal memorial recognising them should come as no surprise.

Yet, as David Grant suggests, these dissenters – Baxter and Briggs in particular – showed personal characteristics “which most New Zealanders hold dear: humility, determination, idealism, strength of character, sacrifice”.

Since the anti-Vietnam movement of the 1960s and the anti-nuclear politics of the ’70s and ’80s, New Zealand’s national identity has become far less militaristic, allowing the perception of conscientious objectors to lighten considerably. We Will Not Cease, Archibald Baxter’s startling account of his treatment by the state, has been republished several times since 1968, creating a wide audience for a story few New Zealanders previously knew.

Minister for Arts, Culture and Heritage Chris Finlayson has expressed a desire to see some

kind of memorial at the National War Memorial in Wellington. As yet there is nothing official planned, but the possibility is in place.

The Archibald Baxter Memorial Trust has been set up to honour Baxter and other conscientious objectors, with plans for a memorial in his home town of Dunedin. The trust hopes it could be unveiled to mark the Passchendaele centenary in 2017 but first needs to raise up to $100,000.

David Grant, who is part of the trust, says the story of conscientious objectors needs to be more widely known and the site, possibly in the Dunedin Botanic Garden, would be a focus for reflection on the role of Baxter and others in rejecting warfare. “We’re trying to get that story recognised as part of the wider story of the First World War.” He says he would like to see more sites in New Zealand that are associated with conscientious objection given recognition, including the former home of Mark Briggs in Nikau Street in Palmerston North.

GOING COMING &

WORDS: SALLY BLUNDELL

“We’re under canvas,” wrote trainee soldier Charles Borlase in 1916. “The rain comes in like thru a sive [sic]. No matrace [sic] and cold as hell.” The Tauherenikau training camp in the Wairarapa, he concluded, “is a bugger of a camp”.

From 12 August 1914, when Britain accepted New Zealand’s offer of a voluntary expeditionary force, it was clear that the country’s provisional training camps, previously used for local territorial forces, could not meet demand. “There were no large permanent military camps,” says Glyn Harper, Professor of War Studies at Massey University. “And there didn’t have to be – there was no permanent force. Race tracks were often used. The First World War gave a huge impetus to establishing permanent camps and keeping them going after the war.” In keeping with the four districts established under the territorial scheme, mobilisation camps were set up in Auckland (Alexandra Park), Wellington (Awapuni Racecourse, near Palmerston North), Christchurch (Addington Park) and Dunedin (Tahuna Park).

While newly established camps in Trentham and Featherston provided most of the training for reinforcements, a number of smaller camps sprang up around the country. Featherston had satellite camps at Tauherenikau and Papawai. Trentham, following an outbreak of infectious diseases, established temporary overflow camps in Waikanae, Rangiotu and Maymorn (near Upper Hutt). The Medical Corps continued to train at Awapuni, trainees bedding down in the grandstand, while Maori and Pacific troops and Tunnelling Corps reinforcements were trained at the new Narrow Neck Camp (it also served as an internment camp for “enemy aliens”).

“Narrow Neck was a very busy camp during those war years and a really nice location overlooking the harbour,” says Glyn. “It was warm and had a much healthier climate than Trentham.” But conditions, particularly in the country’s canvas camps, could be rough. Land often had to be cleared before tents could be erected and lowlying camps such as Awapuni were prone to flooding.

In 1914 territorials at the Takapau Divisional Camp at the historic Oruawharo homestead in Hawke’s Bay, known as the birthplace of the distinctive lemonsqueezer hat, decided enough was enough. While officers lived “softly in the mansion”, trainees contended with meagre food rations, long hours and only one uniform each (this during a particularly rainy season). According to The Sydney Morning Herald, demonstrators “took up a menacing attitude, hooting, yelling and throwing occasional stones amongst the police”.

After the required six to 14 weeks of training, volunteers and, from November 1916, conscripted soldiers throughout the country left their camps to travel by train or boat to Wellington. For the 8454-strong New Zealand Expeditionary Force that left on 16 October 1914, says Glyn, public interest was strong. Crowds of bystanders lined the streets to farewell the troops, who were expected to be home by Christmas. “It was a big celebration, like sending off a rugby team rather than men going to war.”

From training camps to military hospitals, buildings were established to meet the needs of soldiers leaving to fight and returning to recover1 Featherston Military Camp hospital, circa 1914-1918. PHOTO: WAIRARAPA ARCHIVE 2 Pukeora Estate vineyard in morning mist.

By mid-1915, when hospital ships began bringing home soldiers wounded at Gallipoli, the farewells had become less celebratory. Thomas Seddon of the Ninth Reinforcements, son of Richard (King Dick) Seddon, described the “serious-faced” crowd that came to see them off at Wellington in January 1916. After Gallipoli, he wrote, these onlookers “now realised that no easy conquest awaited us”.

They were right. Of the 100,444 New Zealand soldiers who saw active service, 18,166 were killed. A further 41,300 returned ill or wounded. Specific wards set up in general hospitals in Auckland, Wellington and Christchurch (the Annexe, Victoria and Chalmers Wards respectively) were stretched beyond capacity. New military hospitals were established, often in former training camps such as Trentham, Featherston (where a “lock hospital” was established for soldiers with venereal disease) and Narrow Neck.

The country’s first new military hospital, the King George V Hospital in Rotorua, opened in 1916. Its large octagonal dormitories, lantern roofs and unglazed windows typified the prevailing belief in the importance of fresh air, sunshine and a calming rural outlook for patient recovery. The octagonal buildings were later recycled to become the Otaki Children’s Health

“It was a big celebration, like sending off a rugby team rather than men going to war”1 Takapau Divisional Camp, 1914. PHOTO: SUPPLIED BY ORUAWHARO HOMESTEAD 2 World War I troops on parade, Lambton Quay, Wellington. From the John Dickie (1869-1942) collection of postcards, prints and negatives.

Camp. Only one, the Heritage New Zealand Category 1-registered Otaki Children’s Health Camp Rotunda, now remains, a reminder of New Zealand’s first World War I military hospital and first permanent children’s health camp.

A number of small “war hospitals” were also established. Following the example of the 1903 Ranfurly War Veterans’ Home and Hospital in Auckland, the Montecillo War Veterans’ Home and Hospital opened in Dunedin and in 1921 the Rannerdale Veterans’ Hospital and Home opened in Christchurch.

Private homes were similarly opened up to this influx of sick and wounded men. In 1915 Dr Charles Izard offered his Upper Hutt house as a convalescent home for up to 30 “sick and wounded troopers coming from the front” (before that it had been used by trainee soldiers struck down with measles).

In Lowry Bay on Wellington Harbour the Taumaru Convalescent Home occupied two houses owned by lawyer, politician and, briefly, Prime Minister Sir Francis Bell. According to the Journal of the Nurses of New Zealand (1916), “those whose spirits have suffered by the horror of all they have seen and endured should forget it all in the calm peace and beauty around them”.

Those returning with respiratory problems and tuberculosis were often sent to more remote locations, so prolonging the periods before they could be returned to families and working life. Existing spas in Wakari, Pleasant Valley and Rotorua could not keep up with demand. In 1919 the Repatriation Department took over the Tauherenikau lease as a farm for tubercular servicemen, with training programmes in market gardening, poultry keeping and pig breeding.

A new military sanatorium (“Soldiers’ San”, later called the Upper Sanatorium) was built in 1920 on the

Cashmere hills in Christchurch above the King George V Coronation Hospital. On the Maniototo Plain in central Otago the Orangapai or Waipiata Sanatorium catered for up to 122 patients.

Near Waipukurau the Pukeora (“hill of health”) Sanatorium built in 1918 was designed to make the most of the brisk air and 270-degree views. While many of the smaller buildings have gone, the veranda dormitories with their large, tilting windows are now home to the Pukeora vineyard and function centre owned by Max Annabel and Kate Norman, the high altitude and northfacing direction, once a prescription for tubercular patients, a winning combination for their Pukeora Estate (formerly San Hill) wine.

They came by train, then by foot – more than 1000 men from the upper South Island marching through fields of tobacco and raspberries in the Motueka Valley to a canvas town of regimented rows of bell tents in rural Tapawera, first as volunteers, then as territorials. As the Marlborough Express noted in 1914: “There will be hard work to do –nowadays we do not play at soldiering”.

“It was the end of the railway and there were no towns, no pubs. You could fire your cannon without anyone knowing,” says Maurice Taylor from the Tapawera Historical Society. While shells have become part of local folklore, there is no physical evidence of the infantry, mounted rifles, gunners, officers, medics and engineers who trained here.

Last year Maurice worked with the local school and historical society to recreate the regimental stag passant emblem of the former 12th and 13th Nelson-Marlborough-West Coast Regiment, originally picked out in whitewashed rocks on the hillside. With assistance from the New Zealand Army reserve, six tonnes of rock were carefully placed to a design mapped out by an eight-metre template to honour the men who trained there. “It was an important training ground and it’s an amazing piece of history.”

In many instances the men’s injuries defied orthodox medical treatment. Between 1916 and 1922 some 1500 soldiers returned with symptoms of battle fatigue, neurasthenia, combat hysteria or, as it was more commonly known, shell-shock. In England such symptoms were initially regarded as signs of weakness – some patients were shot as cowards – but increasingly they were recognised as serious but treatable reactions to the trauma of war.

Families and patriotic associations were adamant that these “broken heroes” should not carry the stigma associated with mental institutions. While the most serious cases were hospitalised, those suffering from “light mania” or “borderland” neurasthenia were placed in cottage annexes such as the country home of Plunket founder Truby King, then Medical Superintendent at Seacliff Mental Hospital at Puketeraki on the Otago coast.

In 1916 the Queen Mary Hospital for Sick and Wounded Soldiers, the first purpose-built institution to treat World War I veterans with psychological disorders, opened its doors to the bracing mountain air of Hanmer Springs. “It was the location,” says Heritage New Zealand Heritage Advisor Robyn Burgess.

“The idea was for people [soldiers] to come and be treated in a quiet alpine environment with fresh air and beautiful scenery.”

Built on the site of the former sanatorium (burned down on the eve of World War I) the Soldiers’ Block, now one of three Heritage New Zealand Category 1 heritage buildings on the 5.1-hectare site, was similarly designed to maximise access to clean air and sunshine, incorporating canvas blinds instead of glazed windows and a daily routine of rest, sport, gardening, physiotherapy, massage and vocational training. As at Rotorua, where treatments in the Bath House increased from 545 in December 1915 to 4000 in August 1918, veterans were encouraged to enjoy the therapeutic values of the thermal springs.

Unlike the often-ostracised tuberculosis patients, there seems to have been a groundswell of sympathy for these damaged veterans. On the East Coast, the stable at historic Puketiti Station bears the simple signature “Jock” scratched on a wall. According to family tradition, Jock was a shell-shocked soldier recently returned from the war. The Williams family gave him a room in the stable and work as an odd-job man. Jock’s surname was McKenzie, but nothing more is known about him.

Great War Stories

Ripapa (“mooring rock”) Island in Lyttelton Harbour, now administered by the Department of Conservation, is steeped in military history. In the mid-1880s, as the “Russian scare” gripped the country, Ripapa was selected as one of Lyttelton’s four coastal defences. The quarantine buildings came down and workers, including local prison labour, completed a submarine mining depot. Four large guns – two eight-inch rifled muzzle-loaders and two six-inch hydro-pneumatic disappearing guns – were installed and by 1895 the formidable-looking Fort Jervois, the colony’s most complete single fortress, was fully operational. The island was remilitarised in World War I.

Alongside the “Ripapa Island martyrs” – young conscientious objectors who staged a hunger strike in 1913 – incarcerated on the island was noted German navy raider Lieutenant Commander Count Graf Felix von Luckner. An exceptional seaman (he sank 14 Allied ships in 1917), he was also known as a considerate captor. His raids produced only one casualty and those who were taken captive by him unanimously spoke well of him. After escaping from Motuihe Island in the Hauraki Gulf, von Luckner was taken to Ripapa Island. Here, the story goes, he devised an escape plan but felt too much sympathy for his commanding officer to carry it out.

haven A SAFE

For all its strict discipline and rigorous training, for trainee soldiers the army camp at Featherston was a respite before the horrors of front-line fighting

WORDS BY: MATT PHILP • PHOTOGRAPHY: MIKE HEYDON & WAIRARAPA ARCHIVE

There were no speeches or waving of flags to mark the occupation of Featherston Military Camp. On the morning of 24 January 1916, reported The Evening Post, “the men simply went in”, arriving in dribs and drabs from nearby tented camps. Some 300 employees of the Public Works Department were still hammering away, and would be for weeks afterwards.

The lack of ceremony reflected both Featherston’s location, near a quiet rural service town at the foot of the Rimutaka Ranges, and the urgency of the times. The war by now was swallowing men in multitudes and New Zealand was required to ship reinforcements on a monthly basis. Featherston was where civilians were to be turned into soldiers; the photos and flag waving would wait.

Today there’s little left to indicate the scale of what occurred at Featherston (the camp was demolished after the war) but 60,000 men were trained there, roughly three-fifths of those who served in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force. “Military training was never so concentrated in our history as between 1916 and 1918 in the southern plains of the Wairarapa,” writes Neil Frances in Safe Haven, his 2012 history of the Featherston Military Camp during the Great War.

Neil, a Masterton-based amateur historian with a particular interest in military history, subtitled his book The Untold Story of New Zealand’s Largest Ever Military Camp. So why has Featherston’s role been forgotten? Early histories of New Zealand’s participation in the

Great War tended to focus on everything that happened from the moment of embarkation. Also, the public memory of Featherston is dominated by what happened after it was rebuilt as a prisoner-of-war camp when, on 25 February 1943, 31 captured Japanese were shot dead by guards and 17 more died later.

Featherston was conceived as a model camp, a response to issues that had plagued other training camps assembled hurriedly at the start of war. On the other side of the Rimutakas, Trentham had been temporarily evacuated in 1915 after an outbreak of meningitis. The new camp was designed to minimise the risk of contagion, with higher barracks, fewer men to each room and stove-warmed drying rooms; the hospital was to be rotunda-shaped to aid the circulation of air and included isolation wards.

Military thinking by now was aware that keeping armies fit was crucial to winning battles; in the South African War many more men had died from fever than from fighting. “There’s a much bigger story here from a medical point of view about the changes they incorporated to keep soldiers well,” says Neil. “The business of daily sick parades seems like a joke, but they were absolutely serious about it – they didn’t want any men soldiering on with infectious diseases.” (Mostly they were successful. When the 1918 influenza epidemic struck, however, Featherston fared as badly as any institution peopled by the most susceptible age group, with 164 fatalities.)

Suitable land was identified for the camp north of the Featherston-Greytown road in July 1915. Within days work had started on a rail siding and the pace didn’t relent for months. Together with the satellite canvas camps at Tauherenikau and Papawai, the camp-sites and training grounds covered 751 hectares of land, incorporated 90 or so barracks buildings, a hospital precinct, separate clubs for soldiers and officers, shops, a dining hall and religious institutions and could accommodate a total of 7500 men with stabling for 500 horses. In a province as sparsely populated as Wairarapa, it was akin to a new town arising almost overnight.

Wairarapa archaeologist Christine Barnett was engaged by Heritage New Zealand to write a report on Featherston as part of its becoming covenanted. Walking over the site of the World War I camp you can see evidence of the road, she says, along with foundations and drainage channels. There’s an atmosphere, too, less haunting than captivating. “It’s a lovely piece of engineering from an industrial archaeological point of view. It was very well planned and executed and you can feel that when you’re there on site, that it was ship-shape and military fashion.”

Neil Frances is struck by the sheer scale of the Featherston build. “In late 1915, when New Zealand’s population was only one million, you had 1000 men on that building site at Featherston. If you compare that to today, it’s like having 5000 men on a single project and of course it was pretty much all built by hand.” He is also impressed – perhaps nonplussed, more accurately – at the pains the army took to beautify the surroundings, including planting flower beds, lawns and shrubs. “It makes an interesting contrast to the very pragmatic business of getting men ready to go overseas to kill Germans and Turks.”

Featherston was where civilians were to be turned into soldiers

Featherston’s main role in that project was field training for infantry, mounted rifles and artillery. The men didn’t arrive as totally raw material. While New Zealand’s professional army numbered barely 300 at the outbreak of war, Kiwi men aged 18 to 25 had been required to train with the Territorial Army. Before arriving at Featherston, they had also done some basic training at Trentham in such fundamentals as kit, marching and shooting. In the new camp, their schooling was advanced with rifle drills and bayonet fighting, shooting courses, night training, trench digging and hand-to-hand combat, all based on British Army standards. Physical fitness was emphasised.

“Not all were fit young farm boys,” remarks Neil. “They were drawn from all walks of life, from lawyers, drapers and shop assistants through to hardy bushmen. The goal was to get all of them to the same level of fitness and obedience and acceptance of military routines. The training was repetitive, but the feeling I got was that most just got on with it.”

The camp itself was a tightly managed operation, headed by a commandant, Lieutenant Colonel Noel Adams, who’d been a land agent before the war. Standing orders for Featherston were British Army standard and ran to hundreds of pages, covering almost every aspect of life imaginable right down to the requirement for every man to have a toothbrush. Even so, it was a far less hierarchical and rigid regime than they would find during final training in Britain.

Featherston was a dry camp and Wairarapa publicans were under instructions that soldiers on leave could drink only on the premises. Naturally there were incidents, generally involving booze, but fewer than you might imagine and relations with the surrounding community were generally harmonious. “Certainly from a commercial point of view the shopkeepers of Wairarapa weren’t unhappy about the presence of the camp. Men on weekend leave would hire taxis to go into Featherston or up to Greytown and a leave train went up to Masterton once a week, where there was usually a dance put on for the men. They were encouraged to behave themselves and generally they did.”

And after 16 weeks of training, off they sailed to war. In the waking nightmare of a trench in France, they must have longed for the sweet ennui of marching drill at Featherston, their safe haven.

TRENTHAM

If Featherston was a safe haven, Trentham was anything but. Its problems arose partly from the ad hoc nature of its establishment. When New Zealand entered the war in August 1914 there were no permanent camp facilities and training took place in locations such as race courses. Sited in the Hutt Valley, Trentham developed into a permanent camp “almost by accident”, according to Neil Frances, who adds in his book that “the unsuitability of the land and the speed of growth did not favour the early life of the camp”. From the start there were health problems, with 180 cases of measles and 126 of ’flu, colds or sore throats recorded for May 1915. In July, with 7500 men squeezed into Trentham, an outbreak of cerebrospinal meningitis caused the hasty evacuation of the camp; even so, 19 men died that month of various diseases. The response was immediate: the camp was surveyed for roading and drainage and a limit of 5000 men established. But even as improvements continued at Trentham, the army had embarked on building a new and improved camp on the other side of the

THE BUSINESS OF

Gallipoli, the Western Front, the misery of life in the trenches… such are the words and images that conjure up the horror stories many of us know of World War I. But there is, notes Gavin McLean, a senior historian at the Ministry for Culture and Heritage, another side to that story. “That’s the economic one. Many people and many businesses actually had a very good war. It was not, for all, unrelieved gloom.”

Maintaining the flow of goods on which Britain depended was a major part of New Zealand’s war effort, and shipping firms, woollen and textile mills and the primary industries were among those sectors of our economy that were called on to ramp up activity and production on the home front.

In his recent paper The Impact of the Great War on the New Zealand Economy , economist Brian Easton writes that while there would have been much attention given to the individual events that

made up the Great War in the following four years, less was likely to have been made of their long-term impacts, particularly on the economy. “In contrast, it is my contention that the war experience fundamentally affected the way we governed New Zealand,” he writes.

So how did our economy actually fare in this period? Brian’s interpretation of the data available suggests that while the economy grew in the Liberal boom to 1908, it was followed by a long period of stagnation in terms of per capita GDP, which came to an end 27 years later as the economy emerged from the Great Depression. “There is little evidence of a boom in production during the Great War (in contrast to the boom of the Second World War), probably because of the withdrawal from the labour force of overseas service personnel. Given that there was not a drop in production (as far as we can tell), productivity must have risen,” he notes.

Increased demand for goods to feed the war machine meant unprecedented profits for some of our home-grown industries

It is clear that certain industries and specific businesses did well during World War I and Gavin talks about the three Fs when describing the sectors that did best: fibre, food and fuel. Wool was one of our major exports at the time and was an industry vital to supplying the war effort. Demand took off strongly due to the need to clothe not just our own troops but those of the rest of the Empire.

Based on the solid reputation it had gained during the South African War, the Kaiapoi Woollen Mill (a Category 2 Historic Place) was able to secure contracts to supply cloth for uniforms and blankets, giving it a steady income during World War I, according to a local history of the mill recorded by

Waimakariri Libraries. As a sign of support, the mill also paid partial wages to its employees on military service. In fact, demand was so strong in the sector that shift work was introduced for the first time at some mills; orders for khaki-coloured fabric stretched to the limit the capacity of Lane Walker Rudkin’s Ashburton mill, where machines ran 24 hours a day.

Among the sites included on Auckland’s First World War Heritage Trail (see story on page 46) is Onehunga’s Jellicoe Park, where particular mention is made of the Onehunga Woollen Mills (another Category 2 Historic Place) on Neilson Street. In 1917 the mill received a government order worth £95,341

“Many people and many businesses actually had a very good war. It was not, for all, unrelieved gloom”

PROCESSING POWER

Meat processing was an important industry for New Zealand’s war effort, with 10 new freezing works built during that time. The industry was also significant for the suburb of Otahuhu in Auckland, where prominent meat-processing businesses of the time included plants such as the Auckland Freezing Company, the Westfield Freezing Company and R&W Hellaby Ltd (Shortland Freezing Company). Bell Avenue in Otahuhu is one of the sites being recognised for its economic significance on the Auckland First World War Heritage Trail, which includes a note that Prime Minister William Massey opened the Westfield plant on 29 May 1916. The works closed in 1989.

to produce khaki material, according to notes from the trail, which also mention that the mill was the site of experiments conducted in 1916 by Professor Worley of Auckland University to create a waterproofing process. The findings of his research were later employed by the military to apply waterproofing to uniforms, tents and other materials.

The farming sector was another major contributor to the war effort, as maintaining the flow of food to Britain was seen as being of critical importance. In 1915 Britain and New Zealand negotiated a bulkpurchase agreement whereby Britain agreed to take most of New Zealand’s surplus exportable produce – dairy products, meat and wool – at fixed prices. For farmers, used to the uncertain ebb and flow of commodity prices, this was a period of guaranteed relative prosperity.

Sending offshore what was produced, however, was another matter. Shipping was a major issue, due to capacity being diverted directly to the war effort and suppliers such as Argentina being closer to the United Kingdom. To accommodate this scarcity of shipping, says James Watson, Associate Professor of History at Massey University, there was a significant development of freezing works and refrigerated capacity in New Zealand during World War I.

In fact, he notes that New Zealand ended the war with vast quantities of meat in cold storage, bringing with it a collapse in prices. Some farmers who had bought land at high prices or sold their land on mortgage during the prosperous war and immediatepost-war years later found themselves in financial trouble with unsustainably large debts or holding mortgages that mortgagors could no longer service.

Indeed, Gavin describes shipping as the most crucial business for New Zealand during World War I and central to that was the Union Steam Ship Company, started in Dunedin in 1875 by James Mills. “The Union Steam Ship Company was our first multinational company,” Gavin explains. “It had a fleet of about 70 ships at the outbreak of World War I which was as many as the next five largest Australian shipping companies put together. That

capacity enabled a huge amount of work to be done and goods to be transported; through that we were able to supply hospital ships, freighters and, of course, troopships.”

Gavin describes the profits the company made during World War I as “almost obscene”, with the firm reaping more than a 100 percent return on capital at the peak of the war. “All of the Empire shipping companies were making more money than they knew what to do with,” he says. “And they were all desperate to hide it, which led to a series of takeovers. That’s really why P&O took over the Union Steam Ship Company in 1917. You saw a massive consolidation of British shipping companies during the war, partly to hide profits.”

While fuel, specifically coal production, played a vital role in the war effort, Gavin notes that by

“A lot of businesses found themselves struggling with skilled workers being called up”

TEA TIME

One New Zealand company to see a boom in its business during World War I was the Bell Tea & Coffee Company, and for a somewhat unexpected reason. During wartime, the Government announced a special postage concession rate for care parcels being sent to our boys serving overseas. To be eligible for the special rate, the parcels had to be within certain dimensions and those dimensions related directly to the size of Bell’s onepound tea tin. The company’s History of Bell recounts the resulting effects on the business: “A windfall to the company, sales boomed to the point of becoming out of control”. The phenomenon also soon became an issue on the front lines, where it was claimed the presence of the New Zealand Division could be detected by the proliferation of Bell tins left scattered on the ground.

the second half of the war coal was in short supply. Increased requirements from shipping and rampedup factory production along with strike activity, mainly on the West Coast, meant that by late 1917 episodic shortages of coal were becoming serious.

Labour shortages were another characteristic of New Zealand’s wartime economy and in his paper Brian notes that more than a fifth of the labour force would not have been available for civilian production during World War I. “A lot of businesses found themselves struggling with skilled workers being called up,” says James, “and although they could appeal, very often they found themselves in difficulty.” Slaughtermen in freezing works, waterfront workers and coal miners were among the occupations more likely to gain exemptions.

Inevitably, however, some decisions regarding exemptions proved contentious, such as the case of Robert Laidlaw. When he was called up for military service in 1918 he applied for exemption on the basis that his thriving mail-order business, Laidlaw Leeds (which later merged with the Farmers’ Union Trading Company) could not operate without him, putting his employees and investors in jeopardy. He was effectively excused by the Military Service Board after it granted an indefinite adjournment of his case, leading to criticism that it showed favouritism to the wealthy.

SADDLED UP DIGGING FOR VICTORY

WORDS: MATT PHILP • PHOTOGRAPHY: NATIONAL ARMY MUSEUM, NEW ZEALAND

War is hell, but it also makes room for the strange and the improbable. New Zealand’s war effort included a trio of unlikely and little-reported fighting forces whose stories never quite fitted the conventional narrative of the Great War. The New Zealand Cyclist Corps, the New Zealand Camel Corps and the New Zealand Engineers Tunnelling

Company operated on the margins of history, but their exploits were as vital as any to securing victory.

The cyclists

When the New Zealand Cyclist Company was formed in March 1916, its personnel were volunteers from among the Mounted Rifles Brigade reinforcements training at

Featherston Military Camp. They signed up as horsemen but rode to war on bicycles under a badge of a winged front wheel and handlebars.

After a brief foray into Egypt, the company arrived in Marseille, where it was reconstituted as the 2nd Anzac Cyclist Battalion, made up of two-thirds New Zealanders and one-third Australians.

Their duties for the next two years were varied. They laid a lot of cable – 90 kilometres of trenching, in fact, excavated to a depth of at least two metres. As the official regimental history notes, with the average number of wires laid being 50 pairs, the total length of wire works out at about 9012 kilometres. They handled traffic control, felled trees and repaired trenches. And, when required, they held the front line.

Cycling in the dead of night to White Gates, they had to don masks after encountering enemy gas. “On reaching our rendezvous everything was dead still, not a gun had been heard for an hour or so, when suddenly a huge 12in gun in the rear was fired, at which signal 19 mines along the whole army front were exploded; thus at 3.10, zero hour, the Battle of Messines was heralded.”

Messines in June 1917 was a key moment in the cyclists’ war. Working under intense shelling, they prepared an 1800-metre track from the reserve line through

Three unlikely and little-known fighting forces contributed their special skills to the war

No Man’s Land and abandoned German trenches for the mounted troops to follow. Several died and many more were injured; seven members of the battalion received decorations. At other battles they participated in offensives or filled the gaps defending the line.

In the regimental history’s account of Messines there is a line that sums up the cyclists’ war: “Our part, though not spectacular, was important, in fact just as important as any other”.

The New Zealand camel companies

It’s hard to envisage a lesspredictable wartime scenario for a New Zealand lad than riding a camel in the Egyptian desert. But such was the fate of about 400 Kiwis who signed up as reinforcements for the Mounted Rifles Brigade, only to find themselves part of the Imperial Camel Corps Brigade at the El Mazaar oasis in the Sinai in late 1916.

Mostly these cameliers were used for long-range desert patrol work and protecting the railway, pipelines and other strategic assets that sustained the Egyptian Expeditionary Force. Their first taste of action at the Battle of Magdhaba in December 1916 came soon after arrival in Egypt.

When the Palestine Campaign escalated, so too did the cameliers’ role in the fighting. A New Zealand company fought alongside the Auckland and Canterbury Mounted Rifles Regiments at the battle for Hill 3039, a strategic landmark overlooking the city of Amman where British forces were attempting to breach the Turkish defences. After capturing and then bravely defending the heights they were forced to retreat, losing three of six officers in battle.

Photographs held by the Alexander Turnbull Library show camels of the two New Zealand companies equipped with stretchers known as cacolets, described as “a contrivance lashed to a camel’s back which carried a man on each side; the rolling motion… exacts the full penalty of pain from the unfortunate occupant”. Another shot shows men from the No, 15 New Zealand Company wandering among corpses of camels killed by a Turkish air raid at Sheikh Nuran.

“Although we often cursed them, when they were to be taken away from us we found we had become attached to our ugly, ungainly mounts,” wrote an Imperial Camel Corps trooper. Even so, when in June 1918 the Kiwi cameliers were redeployed

as mounted rifles, you imagine they must have been grateful to be back on horses.

The tunnellers

They waged war from beneath the trenches, using picks and shovels rather than rifles. The tunnellers of the New Zealand Engineers Tunnelling Company numbered fewer than 1000, arriving at the Western Front between 1916 and 1917. Many had some background in mining but the unit included others such as bushmen, labourers, quarry workers and engineers with tunnelling know-how and applicable practical skills.

Training consisted of basic infantry drills, learning how to fire a rifle and use a bayonet, but these men were in Europe to dig, not to shoot, and their mission was by its nature about keeping out of sight.

In his history of the New Zealand Engineers Tunnelling Company, Anthony Byledbal of the University of Artois in Arras describes the underground war as a fight where guile was the main asset. “The enemies had to play a mortal chess game. They tried to be more clever, forseeing the movements and attacks of the opponent with a bugging device: the geophone. The work of the

tunneller demanded calmness, efficiency and silence.”

It began for the New Zealanders in trenches near Arras, where they were assigned an area known as J Sector. Working day and night in eight-hour shifts, they attacked the chalk layer typical of the region. Later they were tasked by British High Command with finding old quarries under Arras, a prelude to the innovative Arras offensive in which the Allies attempted to break through German lines by launching part of their offensive from underground. By the time of the attack, the network of tunnels had grown large enough to conceal 24,000 troops and the bulk of the digging was done by the New Zealanders.

1 The 15th Company Imperial Camel Corps was made up entirely of New Zealand troopers.

2 Constant digging was required. Tunnellers of the New Zealand Engineers Tunnelling Company built strong defensive positions on the battlefield.

3 In 1916 and 1918 Prime Minister William Massey and his coalition deputy Sir Joseph Ward made extended visits to the Western Front. Here they inspect the New Zealand Cyclist Battalion.

PEACE in our time

New Zealand and the Allies celebrated the armistice on 11 November 1918 and then waited, along with the rest of the world, until 28 June 1919 for official peace with the signing of the Treaty of Versailles.

Planning global celebrations then wasn’t as easy as it is now; there was no Twitter to inspire a major street party. Even so, New

WORDS: BETTE FLAGLER

Zealand joined the Empire and celebrated a day of thanksgiving on 6 July. Then most New Zealand communities held three days of peace celebrations over a long weekend: Saturday 19 July was soldiers’ day, Sunday was a day of thanksgiving and Monday was children’s day. But after the parties were over communities wanted something

that lasted. They contemplated memorials. As Chris Maclean and Jock Phillips write in their 1990 book The Sorrow and The Pride, the motives for memorials were twofold: to remember and honour the dead and to demonstrate pride in the bravery of our soldiers by acknowledging their contribution to allied victory.

Some communities, like the handful we look at here, chose to erect peace memorials. Say “peace memorial” in 2014 and thoughts of pacifism might come to mind. But almost 100 years ago the idea of a peace memorial was not an anti-war sentiment but a symbolic commemoration of peace and victory.

When the celebrations were over, communities set to work to build memorials that would be lasting reminders of victory and peace

Peace Oak, Papakura

Some communities opted to plant trees as memorials to peace and to recognise the end of the war.

Imelda Bargas, Senior Historian at the Ministry for Culture and Heritage, says that pohutukawa and oak were the most popular varieties and that trees not only offered long-lasting memorials but required no fund-raising and could be planted at the July celebrations.

Some of the oaks, like this one that grew from an acorn planted in Papakura on 19 July 1919, are still enjoyed today but others haven’t survived or their identities have been lost. That’s been a particular problem, Imelda says, for those planted at schools; many schools have relocated in the past 100 years and the trees that weren’t identified might just be blended into the landscape now. This one in Papakura bucks that trend; it started life in the Papakura School grounds, now Papakura’s Central Park.

Probably the most famous peace trees are in Fairlie in Canterbury. Five hundred oaks were planted along what became Fairlie Peace Avenue to commemorate the signing of the peace treaty and the end of the war.

But peace trees weren’t planted only in public places. Garden centres ran advertisements encouraging people to “plant your own peace tree”. Imelda suspects there are many peace trees in private gardens but she hasn’t been able to identify any. If you have one in your garden, please let her know: imelda.bargas@mch.govt.nz

PHOTOS: AMANDA TRAYES

Hawera Memorial Arch

It took five years from the first public meeting of the Hawera Peace Memorial Committee to plan a memorial (on 24 March 1919) to its opening by Prime Minister William Massey on 29 March 1924. In the meantime three oak trees, planted at the conclusion of the peace celebrations in May 1919, marked the site.

Most memorials were built with donated funds and, with very few exceptions, local memorial committees were responsible for fund-raising. This was the case for the Hawera arch, which cost a whopping £2542.

Built mainly of Oamaru stone and Takaka marble, the arch lists the names of the 132 soldiers who were lost in World War I. In the late 1940s the names of the 75 lost in World War II were added. The arch was registered as a Category 2 Historic Place in October 1993.

Ophir Peace Memorial Hall

On 10 September 1923, 18 Ophir residents gathered at the library to discuss building a town hall. They all agreed that they wanted one and all agreed to name it the Ophir Peace Memorial Hall.

That day they organised fundraising and scheduled a social and dance for 7 November. More fund-raising dances and concerts were held and the official opening of the hall on 26 May 1926 was –what else – another dance.

The hall has remained an important part of community life in this small Central Otago town. Resident Lois Galer says that over time the hall was called the War Memorial Hall but, when the residents repainted it, its original name was restored.

In its gold-rush heyday, Ophir was home to more than 1000 residents; today there are just 40 full-timers but they still use the Ophir Peace Memorial Hall, which is included in Heritage New Zealand’s registered historic area, for social functions, book swaps, weddings and dances.

Le Bons Bay Peace Memorial Library

There was strong resistance to utilitarian memorials and a national debate promoting non-utilitarian, artistic memorials was played out during 1919. Even though the Government encouraged non-utilitarian memorials, eventually seven libraries were built to observe the end of the war. This one in Banks Peninsula includes a dedication to Peace Day, 19 July 1919, above its front door.

A Category 2 Historic Place, the Peace Memorial Library is on the only road through the small settlement of Le Bons Bay, giving it, as the Heritage New Zealand registration report says, prominence and considerable streetscape significance. The simple structure – a single room and entry porch – displays two rolls of honour inside.

Phased out of library service in 1992, the building is currently an archive information centre run by community members.

Mauku Victory Hall

Victory halls and monuments were popular in Britain and some New Zealand towns used the word “victory” to name their halls and other installations. This one is in Mauku, about 45 minutes south of Auckland.

The idea for a community hall, says Tony Bellhouse, the current booking officer, was put forward at a community meeting in 1914. Fund-raising through a shareholding agreement took place in 1919, followed by construction and the opening on 7 June 1922 by Governor-General Lord Jellicoe.

Tony says the hall is available for hire (but not for 21sts – they’re too hard on the old girl) and even though it is now owned by the Auckland Council it is a real community place. Locals take turns at being secretary, booking officer and so forth. It all sort of stays in the family and Tony should know – his father was on the committee for 30 years.

Kowai County Council Peace Memorial

A Category 2 Historic Place, the former Kowai County Council building in Rangiora is now home to the Kowai Archives Society.

Planning for the building began in 1918 when a proposal by County Chairman GA McLean for a new office building for the administration of the county that would “commemorate what the boys from the county had done in the Great War” was accepted. Two thousand pounds were raised through a government loan under the Local Bodies Act and plans for the building were submitted in March 1919. Construction was delayed when tenders exceeded the available funds; a third tender round in 1922 resulted in a contract within the budget. The building was opened on 5 October 1923.

The Peace Memorial served as the council chambers until the council (which had by then merged with Amberley) merged with Waipara County to create Hurunui County and moved to Amberley in 1977.

The building sustained moderate damage in the Canterbury earthquakes of 2010 and 2011, mainly to the front façade. Terry Green, a Kowai Archives Society member, says there have been quite a few inspections and the repair costs are being assessed. In the meantime, members of the society work out of the undamaged back of the building. Appropriately, they are currently recording the stories and photographs of the local soldiers who fought in World War I.

SEASON 2014

BEETHOVEN

The Symphonies

Pietari Inkinen conductor

Four Days. Nine Symphonies. Once in a lifetime.

June

WELLINGTON AUCKLAND

MAHLER 9

Edo de Waart conductor

If any music could break your heart it would be this.

August

WELLINGTON CHRISTCHURCH HAMILTON AUCKLAND

IN THE HALL OF THE MOUNTAIN KING

Benjamin Northey conductor

November WELLINGTON BLENHEIM INVERCARGILL DUNEDIN OAMARU CHRISTCHURCH

HILL OF memories

On 25 April next year, in the half-light of dawn, it’s probable that someone in Wellington’s Anzac Day crowd will inadvertently drop something, leaving behind an allimportant clue to the historic occasion. Perhaps a button will work loose from a regimental uniform and fall unnoticed to the ground. Possibly a medal will become unpinned and settle somewhere, hidden for a time under the soil of the capital’s newly upgraded National War Memorial Park.

If this were to happen, it wouldn’t be unusual. For the past 150 years, the detritus of military life has accumulated on and around the park’s site on Mount Cook, leaving valuable insights into how and why this low-lying hill overlooking the city has been used.

As recently as last spring, archaeologists working on the memorial park upgrade discovered a British soldier’s button dating back to the 1860s. The 2.5-centimetrewide tunic button is among the earliest evidence of military occupation at Mount Cook, Wellington’s first and the country’s longest-lived military base.

Lead archaeologist Richard Shakles, whose team discovered the artefact, says the button’s markings clearly date it to the period between 1809 and 1876 and show that it belonged to an imperial soldier serving in the 14th (Buckinghamshire) Regiment of Foot.