NO SITTING BACK for Dunedin heritage advocate Lois Galer

Heritage New Zealand SPACE MISSION

A Futuro house that’s out of this world

BY HAMMER AND HAND

BY HAMMER AND HAND

Reviving the ancient craft of blacksmithing

PATTERNS IN NATURE

An artist’s legacy revealed

Your itinerary to history where it happened

Heritage New Zealand

Hōtoke / Winter 2024

Features

12 No sitting back

Lois Galer’s advocacy has helped save many of Dunedin’s heritage buildings – and she’d protect them all if she could

16 Children at heart

The bustle of inner-city life isn’t usually associated with children, but at Auckland’s Myers Park they occupy a special place

22 Space mission

The Futuro might look like a craft from outer space, but the prefabricated house has fans much closer to home

30 Patterns in nature

A previously unknown artwork by acclaimed artist Friedensreich Hundertwasser has been revealed in a Northland home

36 Brave new world

An Auckland couple moved to Ōamaru to restore a grand historic home – and their restoration efforts haven’t stopped there

40 A place in perpetuity

The trailblazing group that helped save a nationally significant Far North heritage site has now wound up, but its legacy continues

Explore the list

8 Colourful past

A modest alpine hut has played a proud part in New Zealand’s international tourism story

10 Face time

The University of Auckland’s Old Choral Hall has long sat at the crossroads of the city’s cultural and intellectual life

Journeys into the past

44 By hammer and hand

A meticulous restoration of the blacksmith’s shop at Lyttelton Harbour has breathed new life into the ancient craft of blacksmithing

48 Home for the holidays

Just as skiers flock to the alpine village of Cardrona in winter, one Auckland couple visits year-round for the love of a heritage cottage

Arrowtown

Chris Tse

Antrim House is a home again.

After being closed for a scheduled programme of exterior restoration, chimney strengthening and reroofing, Antrim House – our National Office – has been reawakened and staff welcomed back in.

With the hustle and bustle of office life breathed back into the grand Edwardian building, our doors are open and visitors are warmly invited once more.

Donations from our members and supporters enabled this important work to happen, and we extend our gratitude to everyone who contributed to this mahi.

Ngā mihi | Thank you!

We are very grateful to those supporters who have recently made donations towards our work. Whilst some are kindly acknowledged below, many more have chosen to give anonymously. All have given heritage a helping hand.

Helen and Gillian Hawke

Mr Philip Rundle

Mr Gordon and Mrs Rita Chesterman

Mr Stuart and Mrs Fiona Gray

Ms Helen Geary and Mr Murray Holdaway

Mr Ross and Mrs Rachel Macfarlane

Mr Andy and Mrs Sarah Bloomer

Mr Ric and Mrs Jill Dawick

Ms Esther Glass and Mr Ken Tunnicliffe

Mrs Vivien Ward

Mr David and Mrs Yvonne Mitchell

Alistair Aitken and Shona Smith

Ms Diane Imus

Mr Andrew and Mrs Amanda Nicoll

Dr Paul Drury and Dr Susan Rudge

Robert Fleming and Peter Dobbs

Mrs Gloria Jenkins

Mr Allan Guy

Mrs Helen Roper

Mr Shayne Elliott

Dr. Colin Patrick and Mr Bryan Gibbison

Mrs Maureen Hill

Mrs Maria Koelet

Mrs Lynley Dodd

Mr Jeff Downs

Ms Ceredwyn Jones and Lesley Abell

Mr William and Mrs Lorna Davies

Mrs Robyn Carline

Mr David Meldrum and Ms Susan Falconer

Mr Joe Hollander

Mr Alan and Mrs Deborah Shuker

The Antrim House tower showing off part of the new colour scheme

Heritage New Zealand

Issue 173 Hōtoke • Winter 2024

ISSN 1175-9615 (Print)

ISSN 2253-5330 (Online)

Cover image: Space Mission by Nicole Gourley

Editor Caitlin Sykes, Sugar Bag Publishing

Sub-editor

Trish Heketa, Sugar Bag Publishing

Art director

Amanda Trayes, Sugar Bag Publishing

Publisher

Heritage New Zealand magazine is published quarterly by Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga. The magazine had a circulation of 7561 as at 31 March 2024.

The views expressed in the articles are those of the contributors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga.

Advertising

For advertising enquiries, please contact the Manager Publishing.

Phone: (04) 470 8054

Email: information@heritage.org.nz

Subscriptions/Membership

Heritage New Zealand magazine is sent to all members of Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga. Call 0800 802 010 to find out more.

Tell us your views

At Heritage New Zealand magazine we enjoy feedback about any of the articles in this issue or heritage-related matters.

Email: The Editor at heritagenz@gmail.com

Post: The Editor, c/- Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga, PO Box 2629, Wellington 6140

Feature articles: Note that articles are usually commissioned, so please contact the Editor for guidance regarding a story proposal before proceeding. All manuscripts accepted for publication in Heritage New Zealand magazine are subject to editing at the discretion of the Editor and Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga.

Online: Subscription and advertising details can be found under the Resources section on the Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga website heritage.org.nz

Looking up

One of my first assignments for Heritage New Zealand magazine was writing about a heritage walk along Auckland’s iconic K’ Road.

As with every story I’ve written for the magazine since, I came away feeling personally richer for learning more about our history and surroundings, and the folk who are passionate about them.

But there was one bit of advice from the heritage walk’s guide, K’ Road historian Edward Bennett, that has particularly stuck with me since that day: “Always look up,” he said.

It’s so true. Raise your eyes above street level in so many neighbourhoods and the beauty and stories of the streetscapes will be revealed – the full facades of buildings, their varied uses, their names and founding dates.

Our heritage is all around us; a taonga hidden in plain sight. It’s in our landscapes, our communities, the places we love to visit – we just need to take the time to look up and more closely appreciate them. Looking out the windows of my own home, I can see a maunga that’s been home to centuries of settlement, and the steeple of a Category 2 church – but I didn’t really know much about either of these places until my work on this magazine opened my eyes to their significance.

After eight years, this is my last note as editor of Heritage New Zealand magazine, and I leave feeling proud of the small part I’ve played in drawing attention to the endlessly fascinating and varied heritage of Aotearoa.

Yes, our heritage encompasses grand former public buildings such as Auckland’s Old Choral Hall and lush domestic residences such as Casa Nova in Ōamaru, which both feature in this issue.

But it also encompasses far more modest sites – industrial buildings such as the smithy in Teddington on Banks

Peninsula, and recreational sites such as Waihohonu Hut, which played a part in the beginnings of our tourism industry –which you can also read about here.

And then there’s the downright quirky, such as the Area 51 Futuro House in Ōhoka – a 1970s spaceship-like domestic space recently listed as a Category 1 historic place. The prefabricated building has been lovingly restored by owner Nick McQuoid, who has made it the centrepiece of a quirky experience that others can embrace by renting a stay in his beloved Futuro.

Nick’s love of Futuros was ignited in childhood and has only burned stronger with time; he’s owned several over the years and has another on his property awaiting restoration. The buildings are incredibly rare – only 100 were ever made, and just 68 still exist – so the passion and advocacy of people like Nick are vital for their survival.

As is yours. It’s your love of heritage, and your advocacy for it in the form of your membership, that allows us to share such stories, helping to raise awareness of and appreciation for our heritage. Your willingness to ‘look up’ and see the heritage that’s all around us, telling the stories of who we are, is crucial to the preservation of our past.

Thanks for sharing the view.

Ngā mihi nui Caitlinmaunga: mountain taonga: treasure

Heritage New Zealand magazine is printed with mineral-oil-free, soy-based vegetable inks on Impress paper. This paper is Forestry Stewardship Council® (FSC®) certified, and manufactured from pulp from responsible sources under the ISO 14001 Environmental Management System. Please recycle.

LETTERS...

Regarding the article ‘Camping out’ in the Summer 2023 edition of your excellent publication, I wish to make a correction.

I am a grandson of Claude Brookes who, as you recognised, was the architect of Tui Glen, the first motor camp in New Zealand. Our parents, Colin and May Brookes, purchased the campground after Colin’s return from World War II and successfully ran and developed the campground until the early ’60s when they decided to sell.

They had hoped that perhaps my brother may have taken it over, but this was not an option for him. The Henderson Borough Council was keen to preserve it as a reserve. While my parents were also keen to see it preserved, the council vetoed any other option. The council set the price of £32,000 [$66,665], which they did not pay for a further three years. In 1964 the council assumed control and employed a manager (Ian Bold and family) who successfully managed it and developed it for another 20 years.

It was subsequent to the Bolds’ tenure that the campground, having now taken on permanent occupiers, deteriorated badly and, as the article says, closed in

2002 and became a reserve, which, for us, the Brookes family, was a happy outcome.

The correction that I wish to make is that in the early 1960s the campground was not struggling, and the council definitely did not bail my parents out, as your article stated, but rather the council left them with no option but to sell to the council at the price the council determined.

Alan Brookes (on behalf of the Brookes family) Motueka

Your article on the old Wellington Children’s Dental Clinic (Autumn 2024) brought back some unpleasant memories. I attended the establishment for a short while back in the mid-1940s but cannot remember it being called the ‘murder house’.

The technique used there at the time was that anything that looked like a cavity was drilled and filled. This meant that any kid who was unfortunate enough to have deeply furrowed teeth finished up with a mouth full of amalgam whether they needed it or not. (And no, it didn’t leak mercury.)

Even after all these years I still have two memories of the place. First is the

SOCIAL HERITAGE… with Paul Veart, Web and Digital Advisor, Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga

In his 1996 history Making Peoples: A History of the New Zealanders, James Belich describes late-19th-century Aotearoa as a land undergoing almost unimaginable change: “A booming, burgeoning neo-Britain, growing hysterically, tamed only historically.”

There are few better places to get a sense of this dynamic than Upper Hutt.

Once the site of immense forests, Upper Hutt was reduced to “tree stumps and barren hillsides” by the turn of the century, before re-emerging as a home for pasture, primary schools, industry and the armed forces (not to mention critically acclaimed pop music).

In the middle of all these changes was photographer Revelle Jackson. Revelle arrived in Upper Hutt in 1952 and in the following decades he photographed the radical changes taking place in his adopted home town.

Last year we included several of Revelle’s photos in a Facebook post on community halls, documenting venues

sadistic delight [the dentists] seemed to take in filling your mouth with cotton wool packers. These resembled a cigarette and were used to keep your cheeks and tongue away from their work. If there was a spare space in your mouth they jammed one in it. They would then tell you not to close your mouth and wander off somewhere, probably to have a smoke or something. You couldn’t have closed your mouth to save your life.

My second memory is of the supervising sister – I suppose that was who she was – who would appear from somewhere and lean all over you to check their work. Honestly, I think that woman’s breath would have stripped paint!

My mother, a retired nurse, took me away from the place and to her dentist, on account of the things she thought were unsatisfactory. I can recall the dentist looking into my mouth and making some very direct comments about the dental clinic, the people who ran it, the people in it, and the disasters in kids’ mouths he had had to repair as a result of their incompetence. By and large and overall, I suppose the place did a good enough job, but it certainly wasn’t all good.

George Newlands

including the Rose of Sharon Hall, Silverstream Social Club Hall, St John’s Church Hall, Federated Farmers (Women’s Division) Hall and Upper Hutt School Hall.

Revelle’s work highlights the fashion of the day, with sweeping haircuts, big collars, and floral shirts, ties and dresses, but look closer and you get a sense of what it might have been like to live in Upper Hutt at such a transformative time. There’s energy and anticipation in many of the photos, with people laughing and chatting. There are decorations, platters of food – and lots of beer.

Of course, the halls are also visible. While some were built for glamour, most were functional, robust spaces, designed to survive the rough and tumble of students and partygoers (as well as the occasional earthquake and flood).

Find out more about historic Upper Hutt by visiting uhcl.recollect.co.nz

MEMBER AND SUPPORTER UPDATE…

with Brendon Veale

It has been a long time coming, and it probably feels like an age for many of you since you donated towards our campaign, but I’m pleased to announce that our national office, Antrim House, in central Wellington, is open again.

We’ve been hard at work strengthening, reroofing, restoring and repainting this turn-of-thecentury grand dame, and completing this project wouldn’t have been possible without support.

I generally use this column to highlight a member (or members) who has made a specific contribution to heritage protection, but since so many of you donated to this project, including some transformational gifts, I’ve decided to give a ‘shout out’ to everyone.

Some of you will have had the opportunity to view Antrim House in its new livery during our recent members open day. For those who haven’t yet had this pleasure, if you are passing during our usual office hours, please do come in. You can have a look around, say hello and, most importantly, see where your donations have been put to work.

As Antrim House is primarily an office, and many of the rooms can’t be

Places we visit

included in a physical tour, in time we plan to offer digital information to allow virtual self-guided tours through the building and its surrounds, and share some of the stories associated with it.

So don’t be a stranger!

Brendon Veale Manager Supporter Development0800 HERITAGE (0800 802 010) bveale@heritage.org.nz

Ngā Taonga i tēnei marama, Heritage this month – subscribe now

Keep up to date with heritage happenings with our free e-newsletter Ngā Taonga i tēnei marama, Heritage this month. Visit heritage.org.nz to subscribe.

HERITAGE NEW ZEALAND POUHERE TAONGA DIRECTORY

National Office PO Box 2629, Wellington 6140 Antrim House 63 Boulcott Street Wellington 6011 (04) 472 4341 information@heritage.org.nz

Go to heritage.org.nz for details of offices and historic places around New Zealand that are cared for by Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga.

A river runs through it

A reminder of the life-sustaining waterway that once flowed through what is now downtown Auckland has surfaced in a new artwork

Called ‘Waimahara’, or ‘Memory of water’, the installation under the Mayoral Drive underpass references Te Waihorotiu, the stream that still flows under the concrete of the city.

Mana whenua artist Graham Tipene (Ngāti Whātua) has led a team of artists to produce the work, which incorporates sculpture, light and sound and is sited at the bottom of Myers Park.

“Instead of creating something that people can stand in front of and look at, I wanted to create a space that was intriguing, and an actual experience,” says Graham.

The sculptures and light and sound elements reference hīnaki and the movement of water to illustrate the

area’s heritage as a mahinga kai. Birdsong, captured by sound engineer Justyn Pilbrow on Tiritiri Matangi Island, also plays as part of the installation.

“There’s the ancient stream that used to flow down there to the Waitematā – to the Fort Street area where the original beach was – and we’ve tried to bring back the memory of those places and our responsibility to the environment.

“The work reminds us of the history of our city – that we’re actually a part of a continuum that started millions of years ago. And while we’re experiencing the most recent iteration of that space, let’s not forget the river that was there and the source of food that came from that river.”

hīnaki: eel traps mahinga kai: feeding ground, food-gathering place

manawa: heart mana whenua: those with tribal authority over land or territory waiata: song wairua: spirit

Visitors will be able to immerse themselves further in the work this year when an addition will allow the work literally to sing back to those who sing a waiata – specially composed by Tuirina Wehi, Moeahi Kerehoma and Tarumai i Whiti Kerehoma – as they travel through the space.

“We want people to arrive and be totally encapsulated by design and design thinking, and the sound, the light and the waiata that enters your manawa and travels down into your wairua. That’s the experience we want to create.”

To learn more about the Myers Park Historic Area, see our story on page 16.

House and garden

Based on a design by well-known architect James Chapman-Taylor in the Arts and Crafts style, the homestead at Tūpare in Taranaki sits within one of the country’s greatest gardens.

Russell Matthews and his wife Mary bought the hillside property overlooking the Waiwhakaiho River in 1932, and set about developing the house and garden of Tūpare over many years (the house alone took 12 years to complete).

Te Ara notes that Russell was inspired by England’s stately gardens when developing Tūpare, and as well

as being a prominent businessman (primarily in roading construction) he had a lifelong love of horticulture. A fellow of the Royal New Zealand Institute of Horticulture and a member of the New Zealand Rhododendron Association, he was also a founding member of the Pukeiti Rhododendron Trust and a driving force in developing this fellow landmark Taranaki garden.

Now owned by the community through the Taranaki Regional Council, Tūpare has the New Zealand Gardens Trust’s highest rating of six stars and is considered a garden of international significance.

Tūpare is open to visitors all day, every day. trc.govt.nz/ gardens/tupare

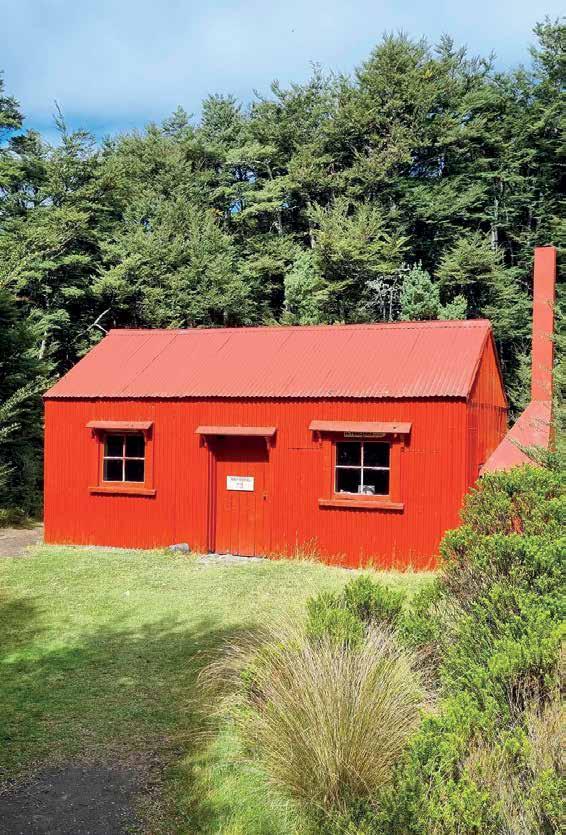

Colourful past

It’s hard to picture a recreational building that punches above its weight more convincingly than Waihohonu Hut in Tongariro National Park.

The club persuaded the Tongariro National Park Board (now the Tongariro Taupō Conservation Board) to not demolish it, despite the hut’s dilapidated state at the time, the cost of its upkeep and the fact that it had been replaced by a modern, 24-bed Department of Conservation (DOC) hut nearby.

Today, the two-room structure stands as New Zealand’s oldest existing mountain hut. It has a Category 1 listing, a DOC conservation plan and a committed volunteer base who tend to its care.

Of its heritage listing in 1993, DOC Senior Heritage Advisor Paul Mahoney says: “At the time, heritage protection was typically extended to much grander buildings like banks, mansions and churches. To get a vernacular building listed was a breakthrough.”

Located about three kilometres inland from the Desert Road between Tokaanu and Waiouru, Waihohonu Hut was originally the centerpiece of a campsite established to host British tourists exploring New Zealand on package tours.

Starting in Auckland, travellers would complete a month-long grand tour of the country, taking in Māori culture and geothermal activity at Rotorua and the Huka Falls in Taupō.

A modest alpine hut plays a part in New Zealand’s trailblazing international tourism story

Erected at the foot of Mount Ngāuruhoe in 1904, the six-bunk cabin celebrates its 120th birthday this year. Yet it’s only thanks to the foresight of the Rotorua Tramping and Skiing Club that it survived past the late 1980s.

They would then travel the length of Lake Taupō by steamboat to Tokaanu, where a stagecoach would take them into Tongariro National Park to overnight in view of the mountains at Waihohonu.

“It was the only stop with no hotel,” explains Paul. “In Rotorua, for example, tourists would stay at the Palace Hotel and relax at the magnificent bath house, also a Category 1 building of the same era and still in use today.

At the time, heritage protection was typically extended to much grander buildings like banks, mansions and churches. To get a vernacular building listed was a breakthrough”

“Really, Waihohonu Hut was ridiculously undersized for the task, which is why they’d typically erect dining and sleeping tents at the campsite too,” says Paul.

Pipiriki, a steamboat embarkation point on the Whanganui River, was another highlight on the grand tour, followed by Wellington, accessed by train.

By 1908, however, Waihohonu had been scratched off the North Island itinerary. New Zealand’s newly opened main trunk railway line suddenly made it possible to travel directly to the western flank of the national park and, over time, boosted visitor numbers enough to justify the construction of The Grand Chateau in 1929.

Throughout this period, says Paul, the tourism

office of the New Zealand Railways Department (later the Department of Tourist and Health Resorts) worked with British travel agency Thomas Cook & Son to promote New Zealand as a holiday destination through advertising and guidebooks.

The marketing trumpeted the wild scenic allure of Tongariro National Park – at the time, the country’s first national park and only the fourth in the world.

That New Zealand could claim such status had been made possible in 1887 when Ngāti Tūwharetoa and the Crown agreed jointly to protect the mountain region for future generations.

“New Zealand was the first country in the world to foster international tourism. For four years, Waihohonu Hut was

very much part of that effort as one of the country’s major strategic tourism assets.”

A timber-framed hut, measuring approximately seven by four metres in size, Waihohonu Hut has pit-sawn totara walls, tongue-andgroove flooring, corrugatediron cladding, pumice insulation and a red-painted exterior. Its separate bunk rooms – one for men and the other for women – reflect the Edwardian gender norms of the early 1900s.

But it was the hut’s proximity to three snowcapped volcanic peaks –Tongariro, Ngāuruhoe and Ruapehu – that prompted the founders of the Ruapehu Ski Club to adopt it as their base in 1914.

That year, the club held its inaugural meeting at Waihohonu Hut, likely discussing matters such as upcoming ski expeditions and the club’s mission to attract more visitors to the park.

Hikers were next to claim Waihohonu Hut as gender norms changed and tramping took off among the sexes throughout the 1920s.

LOCATION

Tongariro National Park is located in the central North Island.

Paul explains: “I remember a friend telling me his aunt, a keen tramper, would farewell her parents and leave the house in full dress, change into pants on the train, and then, upon arriving at the hut, would change into shorts to go hiking.”

Today, Waihohonu Hut is no longer available for overnight stays, although it is frequently visited by the thousands of trampers who stay annually at the modern DOC hut nearby.

Maintained by a volunteer group called Project Tongariro under an agreement with DOC, the historic cabin has a restored chimney, new drainage and some replacement iron cladding, and is regularly cleaned. Interpretation panels were installed for its centenary in 2004. Last spring it was repainted.

An easy 90-minute walk off the Desert Road, the trail to historic Waihohonu Hut is an ideal day walk year round, says Paul.

“To look at it, you might not initially associate that little red hut with the start of alpine tourism in New Zealand. But dig a little deeper and you’ll find it has a more colourful story than most.”

heritage.org.nz/listdetails/7098/Waihohonuhut

Face time

WORDS: CAITLIN SYKES

The University of Auckland’s Old Choral Hall has long sat at the crossroads of the city’s cultural and intellectual life

Sitting on a corner of one of the busiest intersections on the University of Auckland’s City Campus, Old Choral Hall is a landmark building familiar to students and staff, past and present. But it’s a landmark that for some time has been without its ‘face’.

Five years after it was built in 1872, the Category 1 historic place received the addition of a concrete portico to its neoclassical front, constituting what was then described as “a grand focal point”. However, in 1931, following the Napier earthquakes when such additions were identified as potentially dangerous, it was removed.

Now, as part of a substantial strengthening and restoration project due for completion mid-2025, the hall’s portico will be reinstated.

“The building was really missing its face, and this will give it back,” says Tristram Collett, Associate Director of Planning and Development, Property Services, at the University of Auckland.

“It sits at such a key junction for the whole city campus, so it will also give back some prominence to that corner and create a real presence again.”

The building certainly occupied a prominent position in the city in its early days, including serving as Auckland’s main public hall

before the current Auckland Town Hall opened in 1911. Built on the grounds of the former Government House by the Auckland Choral Society, it replaced two earlier halls that had burned down on the same site. It was designed by architect Edward Mahoney of Edward Mahoney and Sons, which he ran alongside his son and architectural partner Thomas Mahoney. The practice was responsible for many other prominent Auckland buildings, including St Patrick’s Cathedral and the former Auckland Customhouse.

Martin Jones, Senior Heritage Assessment Advisor at Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga, says the building was constructed at a time when Auckland was transitioning from being the seat of government (after the capital moved to Wellington in 1865) to a major commercial hub.

“The building itself reflects the transformation in that particular part of the city, which had been a government enclave prior to 1865, and was gradually shifting into an elite residential and cultural area, including for certain types of recreation and entertainment,” says Martin.

The building hosted the city’s grand receptions for its most important visitors. Among such events was a hākari for the Māori King Tāwhiao and other prominent rangatira in 1882, says Martin.

And while the grand hall, accommodating 1100 people, was built for the performance of great classical choral works, it was used for everything from political and religious gatherings to more popular entertainments, with up to 2000 people at times crowding inside its walls.

LOCATION

Auckland city lies between two large harbours in the north of the North Island.

“There's a fabulous account of a group called the Lottie Magnet Troupe, which played there in 1873. It involved Lottie appearing on a single trapeze to ‘The Descent of Mercury’, which I assume was a song that she was singing. They said it was ‘a most exciting scene, but [one] which she performed with alarming alacrity’.”

One of the most prominent people associated with the building was Kate Edger, the first woman in the British Empire to receive a BA from a university. Kate’s graduation ceremony was held in the building in 1877, and Martin says her family’s connections to it run deeper.

Her father, Samuel Edger, who was a non-denominational pastor noted for his progressive social views and was himself an influential figure in the development of intellectual life in Auckland, often gave lectures at the hall and served as vicepresident of the Auckland Choral Society (now Auckland Choral).

The hall has been central to the development of the university, hosting the inaugural ceremony of its predecessor institution the University College of Auckland in 1883, and used for teaching from 1888.

After the building was purchased by the university shortly before World War I, two substantial Edwardian Baroque wings were added to the hall – in 1919 and 1925 – to accommodate the science department. These wings linked the building to other well-known architects, including the Chicagotrained Roy Lippincott, who designed the 1925 extension as well as the university’s Old Arts Building (with its iconic clock tower), which was built the following year.

Internal modifications have been made in the decades since to accommodate the various needs of the university, and addressing these is part of the major project now underway on the building.

Old Choral Hall will become the administrative heart for the Faculty of Education and Social Work following the closure of its Epsom campus, housing its dean and many of its staff and postgraduate students, says Tristram.

The restoration, he says, has involved paring back many of the modifications made to the building over the years to reveal the building’s fabric, and ensuring any subsequent additions are made in a thoughtful way.

A major change has involved creating a central spine through the building to make navigating through it much more intuitive than when it housed a rabbit warren of rooms. A lift is being installed to improve

accessibility, and the rear entrance to the building, which actually accounts for most of its pedestrian access, will be more clearly articulated.

And while the reinstatement of the portico will return the ‘face’ to the hall, it will provide much more than face value; the structure is being used as a key element to strengthen the building.

Robin Byron, Senior Heritage Conservation Architect at Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga, has provided input to the project and is particularly pleased to see the reinstatement of the portico – the absence of which, he says, has left the building’s entrance “a bit naked”.

“The reconstruction of the portico is a real coup for heritage in a way because it will restore some of the building’s dignity and will be a really important feature of the front of the building. And by making it purposeful, it has provided a real justification for doing that.”

heritage.org.nz/listdetails/4474/oldchoralhall %2cuniversityofauckland

WORDS: ANNA DUNLOP / IMAGERY: MIKE HEYDON

No backsitting

Lois Galer’s advocacy has helped save many of Dunedin’s heritage buildings – and she’d protect them all, she says, if she could

“Ican’t remember a time when I wasn’t fascinated by Dunedin’s old buildings,” says Lois Galer. “Even as a child, I had a fascination for them. I loved returning to Dunedin by train after the school holidays and taking off my shoes and socks to feel the magnificent mosaic floor tiles of Dunedin Railway Station under my feet.”

Alongside the Category 1 station, other favourite places from her childhood were the Stock Exchange Building (demolished in 1969) – “I could gaze up at its facade for hours” – and Larnach Castle (also a Category 1 building) –“a favourite spot for a picnic”.

Born and bred in Dunedin, Lois has been a staunch supporter of the city and its historic buildings for decades, and her advocacy started long before she was made Regional Officer Otago Southland in 1985 for the New Zealand Historic Places Trust (HPT, now Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga).

Before she became the trust’s first regional officer in New Zealand, Lois worked for more than a decade as a journalist for the Otago Daily Times, where, among other things, she wrote a weekly column called ‘Houses and homes’ about Dunedin’s historic buildings.

The popularity of the column led to the publication of three books, and a second, later column on city buildings, ‘Bricks and mortar’, resulted in a fourth.

“Research facilities were spartan in the 1970s and ’80s,” recalls Lois. “I’d spend my lunch breaks sifting through records in the Lands and Deeds Department or under the stairs in the Municipal Chambers, going through moth-eaten rates books looking for names and dates that could provide clues to a building’s history.”

As it happens, the Municipal Chambers – an ornate, Category 1 historic place designed by prolific Dunedin architect RA Lawson, which looms majestically over the Octagon in the central city –is one of the many Dunedin buildings that Lois’s advocacy has helped to save. And it’s probably the advocacy project of which she’s most proud.

“I’ve been fighting for that building since the 1960s when I found out the clock tower was to be pulled down,” she says. (Unfortunately, the clock tower was removed in 1963 and replaced with a truncated

metal cap, known locally as ‘the meat safe’.)

Plans to demolish the entire building were considered by Dunedin City Council into the early 1980s, leading Lois and pioneering fashion model Pamela Farry to lobby the council and launch a petition. The duo received a lot of public support, most notably from art historian Peter Entwistle, then curator of the Dunedin Public Art Gallery.

“It got very close,” says Lois, “but we put up a huge battle and eventually the council’s decision was overturned.”

The building, including its clock tower, was restored and the interiors were modernised. It reopened in 1989 as Dunedin’s first official visitor centre and is now part of a complex of civic buildings that house a cinema and concert hall, as well as the town hall and public library.

Lois has also advocated for several other important Dunedin buildings, including Olveston Historic Home and Otago Girls’ High School (both Category 1 historic places). The latter was deemed unsafe in 1986 and, with strengthening considered too expensive, there were plans to tear it down and rebuild it.

“It was the first girls’ secondary school in New Zealand [it’s also believed to have been the first in the Southern Hemisphere] and has had several famous people attend it, so it’s important historically, as well as architecturally,” says Lois.

“I went into battle and got involved with the [then] Old Girls’ Association, which was opposed to the demolition.”

Lois and members of the association sat in on school board meetings, where they “would eyeball the chairman”, and eventually their perseverance paid off:

“I was extremely dedicated to my work, and it was important,” says Lois. “If HPT hadn’t been so involved in the regions, I’m sure many of our historic buildings would have been lost. Dunedin could have looked very different today.”

“I’d spend my lunch breaks … going through moth-eaten rates books looking for names and dates that could provide clues to a building’s history”

the decision was made to strengthen the school using a cheaper, modern method devised by prominent structural engineer Lou Robinson.

The fight for Otago Girls’ High School occurred during Lois’s first year as HPT’s Regional Officer Otago Southland, a job she held for a decade. The role involved researching historic places and advocating for their registration, monitoring restoration work, maintaining trust-owned properties, and public education – writing press releases, preparing lectures and designing heritage walk maps.

Sarah Gallagher, Area Manager Otago Southland for Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga, agrees. “Our heritage list wouldn’t be what it is without the influence of Lois and the work she and others undertook in those early years of HPT. Through her advocacy, the city has retained several buildings that otherwise might have been demolished.”

It was her travels in the HPT role that took Lois

to Ophir for the centenary celebrations of the Ophir Post Office, a Category 1 historic place (see ‘Mum’s the word’, Issue 141, Winter 2016). Lois and her husband Bill, a ship captain, fell in love with the tiny Central Otago goldmining town, and they bought Elm Cottage – also known as Jenkins’ Cottage, named for the original owner Robert Jenkins – in 1990. It served as their crib for five years before the couple quit their jobs and moved there permanently, making the Category 2 historic place home for the next two decades.

The miner’s cottage had a D classification when the couple bought it, which under

the old HPT system meant ‘to be recorded’.

“It dates back to around 1870,” says Lois. “The toilet was still in an outhouse across the yard. It’s fair to say it needed a lot of work.”

Lois and Bill spent several years carefully extending and restoring the two-bedroom Baltic pine cottage using techniques Lois had picked up in her years working with conservation architects at HPT (see sidebar). The couple also bought the shearers’ quarters at the rear of the building and, following talk of a new cycleway passing near Ophir (now the Central Otago Rail Trail), turned them into a backpackers’ lodge.

In 2017 Lois and Bill moved back to Dunedin and in 2022, spurred on by her children, Lois self-published her memoir, aptly named A Memoir… But I Digress.

“My daughters were always telling me to ‘write it all down’,” says Lois. “I’d been taking notes for years, but I got serious about writing it during the pandemic; initially it was just for the family, but they encouraged me to publish it.”

The memoir spans Lois’s childhood in Dunedin, her overseas travels with Bill, her work with HPT and the couple’s time in Ophir. Her passion for the country’s heritage buildings – Dunedin’s in particular – is evident throughout; it’s a passion that earned her a Queen’s Service Medal in 2003.

Not one to sit back, even in retirement, Lois is currently a trustee of the Dunedin Heritage Light Rail Trust, which is pushing to reinstate the cable car that once served Mornington via High Street (the other main routes served Roslyn and Kaikorai Valley).

If the campaign is successful, Dunedin will become only the second

RESTORING ELM COTTAGE

When Lois and Bill bought Elm Cottage, it was “a hotchpotch of additions; part Baltic pine, part rammed earth, part stone”. It had originally consisted of a wooden living section, with a stone and mudbrick kitchen (and that outhouse bathroom). The couple updated the kitchen, then added a living/dining area, bathroom and conservatory in 1997, using schist and timber to match the original building. Lois was determined to preserve the character of the cottage, and one of her first acts was to reinstate the kitchen’s coal range. “It had a disgusting destructor [firebox for waste disposal] with an open hotwater tank beside it,” she says.

city in the world (after San Francisco) to have the grip cable car system. “Think of what that would do for Dunedin’s tourism industry,” says Lois.

Despite her worldwide travels and foray into Central Otago, Lois has always been drawn back to Dunedin.

“It’s just home,” she says. “I see Dunedin as the heritage city of New Zealand and if I could, I’d protect it all.”

“I found a Shacklock Orion No. 1 at a Dunedin demolition yard and had it restored. I also found a timber surround and mantelpiece at a second-hand shop, had the paint stripped off, and oiled it to bring out the grain of the timber.”

The couple removed the Pinex on the roof to reveal a tongue-andgroove ceiling and managed to find genuine linoleum for the kitchen floor.

“I tried to match the original colours of the cottage,” says Lois. “I did paint scrapings and discovered a dark red on the windowsills. I also removed the paint from the mantlepieces and restored those.”

Lois details the extensive restoration of Elm Cottage in her book Time to Smell the Roses: A New Life in Ophir n

WORDS: CAITLIN SYKES / IMAGERY: MARCEL TROMP

Children at heart

The bustle of inner-city life isn’t usually associated with children, but at Auckland’s Myers Park they occupy a special place

In the story of Sleeping Beauty, a girl slumbers in her tower for 100 years, and so it has been for Myers Kindergarten – although children have been sleeping there for a little longer.

Opened in 1916, the iconic Arts and Crafts building in Auckland’s CBD has served continuously as a kindergarten and, as the city has crowded in and thrust ever higher around it, the building’s purpose has remained the same.

As has much of the space. While only a small proportion of the centre’s children actually require

daytime sleeps, those who do still sleep in the original sleeping room, says the centre’s manager, Ankita Sharma. The kindergarten retains its layout of a large, central, circular room that branches out into several small ‘classrooms’ and opens at its north-facing front with high, wide doors onto an outdoor play area.

Licensed for 50 children, it’s technically a fullday early learning centre (under the auspices of the Auckland Kindergarten Association, or AKA, which runs Myers Kindergarten; ‘kindergartens’ follow a shorter-day model) and serves a diverse

Myers Kindergarten sits within the Myers Park Historic Area.

Myers Kindergarten sits within the Myers Park Historic Area.

community of families – from new arrivals to the city, to children of university students and those living or working in the city.

When Heritage New Zealand magazine visits, the large space is filled with children listening to stories, crafting playdough, building with blocks and zooming on trikes.

“Everything was designed for children, and it very much still works as a kindergarten today,” says Ankita, pointing to the building’s curved interior walls, which remove any sharp edges.

In its more than 100-year history, upgrades have been made to the Category 2 historic place. During the kindergarten’s centenary, in 2016, the outdoor play area was significantly upgraded, encompassing water play and a mud kitchen, and a central fale and small whare were added. The large public playground in Myers Park was also updated that year. “Our key point of difference is this natural outdoor space,” says Ankita. “That’s something unusual in the CBD.”

Work was also undertaken on the building during the Covid lockdowns when the centre was closed, and at the time of writing an electrical upgrade was underway, with new heating and cooling systems being installed. Its upstairs space, today used by AKA for teacher training and archive storage, was also being renovated.

Both Myers Kindergarten and the park in which it sits were built with funds gifted by former Auckland

“Everything was designed for children, and it very much still works as a kindergarten today”

mayor Arthur Myers. An AKA publication produced for the kindergarten’s centenary, 100 Years Young: Celebrating a Century at Myers Kindergarten, notes that Myers’ gifts were made during a period of reform in child welfare and education.

The vision for the park – which opened in January 1915 and involved transforming the workingclass housing area in the Grey Street Gully into an expansive green space with a playground and wading pool – was “to represent the modern ideals of childhood and education – together a symbol of progress”.

Myers was a prominent member of Auckland’s Jewish community, which strongly supported kindergarten education and at the time made it a philanthropic priority. Myers’ American sister-inlaw, Martha Myers, was another proponent of the movement and one of the founders of AKA in 1908.

Myers Kindergarten opened in November 1916 and was AKA’s second purpose-built facility. Designed

to foster the principles of the kindergarten movement, its large, north-facing doors opened directly onto the park as a way for children to gain what were seen as the health benefits of open-air environments. Its green-and-white interior colour scheme and the mirroring of the building’s exterior texture in the park’s pathways were also designed to connect the kindergarten’s children to their wider natural environment.

The building’s upstairs space was initially used as a school for special needs children, and later for hearing-impaired children, as well as for AKA teacher training. When the kindergarten was closed during the 1918 influenza pandemic, AKA offered the building for use as a children’s hospital.

Last year heritage research was undertaken on Myers Kindergarten and the Myers Park Historic Area – which incorporates Myers Kindergarten, a commercial terrace of shops, the Theosophical Society Hall and part of Myers Park and the Queen Street road reserve – as part of an ongoing programme to update the New Zealand Heritage List/Rārangi Kōrero.

The research noted that the kindergarten and its wider surroundings were particularly connected with the histories of children, women and broader working-class communities – and these histories pre-dated the founding of Auckland city.

“If you think of taniwha as protecting people … they’re safeguarding what’s most precious, and that is your legacy...”

Makere Rika-Heke, Director Kaiwhakahaere

Tautiaki Wāhi Taonga at Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga, says the area has strong connections, for some iwi, to the taniwha Horotiu – kaitiaki of Te Waihorotiu, or Waihorotiu Stream, which still runs beneath the central city.

Kaitiaki protect, care for and nurture – but we often forget they themselves are mirrors of those they care for and therefore require manaaki, says Makere. The gully that became Myers Park was a taniwha nursery and sanctuary zone. In ancient times female hāwini and kaimahi in a nearby kāinga cared for the needs of Horotiu and other taniwha that frequented the marshy areas bordering the stream.

“If you think of taniwha as protecting people and resources, they’re protecting the fundamentals of life – protecting whakapapa, and therefore the future. They’re safeguarding what’s most precious, and that is your legacy as carried by your children and their descendants,” says Makere.

While the natural landscape has today almost been entirely subsumed by the city’s growth, this heritage is increasingly referenced in the built environment. An art installation called Waimahara, created by a team led by mana whenua artist Graham Tipene, was unveiled under the Mayoral Drive underpass at the bottom of Myers Park at the end of last year.

1. Constructed in 2016 on the site of the original Myers Park paddling pool, a splash pad in the park preserves the heritage features and concrete of the original pool.

2. A recent project, including the installation of Waimahara, has transformed the northern end of the park to better connect it to Aotea Square and make it a more welcoming space.

Melding light and audio effects, it’s themed around remembering water – literally surfacing the heritage of Te Waihorotiu, which still runs beneath.

And less officially, says Makere, taniwha are evident in the work of graffiti artists in the area. This keeps alive the traditions of signposting through symbols, she says, and reinvigorates the memory of taniwha narratives in a contemporary way.

Alexandra Foster, Heritage Assessment Advisor at Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga, carried out the upgrade research on both the kindergarten and the historic area and says it was a rare opportunity to shine a light on places associated with the history of women and children.

“It’s not just the kindergarten; it’s also the other buildings that form part of the historic area it was designed around that have strong links to women and to women’s work, which reflects why the kindergarten’s there,” says Alexandra.

While corporate workers dominate the city today, the kindergarten was constructed to serve a less affluent community of artisans, tradespeople and inner-city dwellers in need. Alexandra’s research revealed that during the interwar period many of the tenancies in the historic area’s terrace of shops on Queen Street were held by women running textile businesses.

Women undertaking teacher training at the kindergarten building would also often stay at the adjacent YWCA hostel (since demolished) – including Alexandra’s own grandmother.

“I knew she’d trained as a kindergarten teacher, but when I mentioned it [my research] to my mum, she said, ‘You know, that’s where Granny learnt to be a

kindergarten teacher, and there were stories about her mother visiting her while she was living at the YWCA’. So it was nice when I was working on the research to imagine that this was where she’d learnt to look after children.”

The research noted that Myers Park also had significance to inner-city communities beyond those for whom it was designed, including sex workers and the homeless.

In My Body, My Business – a book based on a series of oral history interviews carried out by Caren Wilton with 11 current and former sex workers – trans woman Shareda describes first meeting trans women prostitutes while walking through Myers Park as a young teenager in the 1970s. They took her for coffee and, struck by their beauty, she joined the “heaps of girls working in Myers Park”.

“So when I got a chance to go into town, that’s where I used to go, up to Myers Park and make me some money,” she recalls in the book. “I wasn’t nervous – I was excited. It was like a whole new world – I’ve got a nice outfit on, everything’s moving so fast.”

The space has also been the site of student protests and counterculture events, such as Jumping Sundays, which began at Myers Park in the late 1960s before moving to Albert Park.

The kindergarten itself is incredibly diverse; at times up to 31 different nationalities have been represented in the roll.

Toni Nealie, General Manager of Strategy, Governance and Advocacy at AKA, says the kindergarten is very much a part of the wider community that occupies the space. After pick-up time, parents and children will often play in the public park: “It’s a well-loved playground; there are always families here,” she says.

While AKA staff haven’t been housed in the kindergarten building for some years, they have always occupied adjacent commercial buildings. Their current site on Greys Avenue gives them a bird’s-eye view of the children at play in the kindy, as well as the wider park, which Toni says keeps them connected to the central-city community and their purpose within it.

“Keeping our tamariki in mind is crucial – they are our future,” she says. “The legacy of the kindergarten movement has education at its heart, and we never let that go; the idea that every child should have access to good-quality education, it makes a huge difference.”

hāwini: attendants

kaimahi: helpers, assistants

kāinga: village, settlement

kaitiaki: guardian

manaaki: care

mana whenua: those with tribal authority over land or territory

tamariki: children

taniwha: shapeshifter, guardian

whakapapa: genealogy

SPACE MISSION

The Futuro might look like a craft from outer space, but the far-out prefabricated house has its fans much closer to home

What began as a childhood fascination has become something of a life-changing mission for Futuro fan Nick McQuoid.

As a youngster, Nick loved it when his dad took him and his siblings past the Futuro in Christchurch, and as he grew up he wanted to know more about the unique and eye-catching design of these round, prefabricated and habitable ‘flying saucers’.

“I just loved the design as a child,” he says. “I would pester Dad to do a daily drive past ‘the UFO’. I think I drove him crazy!”

Now a new generation of kids are driven past Nick’s Ōhoka property, Area 51, with their own imaginations running wild. Not only is Area 51 home to the UFO-like structure, but the whole site has been developed to tell the story of aliens landing in Ōhoka. From an enormous ‘meteor’ that landed just inside the front gates to the light displays around the pool area, this place is the real deal for outer-space enthusiasts looking for encounters of the third kind.

Nick is considered the New Zealand aficionado of the Futuro, having owned several of the houses over the years. He is part of a wider, but still niche, group of global Futuro owners and his latest mission has been to restore his North Canterbury Futuro so that he can share his love with others.

The history of the Futuro is bittersweet. While Finnish architect the late Matti Suuronen thought he had invented the house of the future, the materials used in its construction soon led to the downfall of his new and innovative housing movement.

In 1968 Suuronen first came up with the idea of a prefabricated accommodation pod, designed to be used as a portable ski hut. While Suuronen hadn’t planned the design around any particular interest in UFOs, the eight-metre-wide and four-metre-high structure was designed with structural integrity and transportability in mind. It was just a quirky coincidence that it also resembled something extraterrestrial, giving it a unique, other-worldly appeal.

“I just loved the design as a child,” he says. “I would pester Dad to do a daily drive past ‘the UFO house’. I think I drove him crazy!”

Built of fibreglass and easily dismantled into separate panels, the Futuro boasted a large, open-plan living area and kitchen, two sleeping areas and a bathroom. It had all the markings of success and went into worldwide production soon after its inception.

By the early 1970s the Futuro was being built in New Zealand by Futuro Homes (NZ), with one showhome at the Christchurch factory on Wainoni Road, where they were produced, while two more were constructed to stand at the entrance gates of the 1974 Commonwealth Games, held at Queen Elizabeth II Park in the garden city.

One was set up as a fully furnished showhome, while the other was bright yellow and used by the Bank of New Zealand, the Games’ major sponsor. A white Futuro was also set up at the Addington Showgrounds in late 1974.

1. Nick McQuoid is considered the New Zealand afficionado of the Futuro.

2. An extensive collection of retro memorabilia can be found throughout the property.

3. The landscaped pool area is yet another attraction for guests staying in the Futuro.

4. From humble beginnings, the Area 51 Futuro has made its mark in Ōhoka.

5. The property is a haven for generations of kids… of all ages.

“The technology was experimental and innovative for its time, which gives it architectural significance – and with only 100 ever made, they are extremely collectable and desirable”

The business began to take off, with orders coming in that fuelled hopes of the operation being expanded to the North Island.

Alas, almost as soon as the craze began, global oil prices skyrocketed – a result of the 1973 oil crisis that saw crude oil prices more than triple – and the fibreglassreinforced plastic shell became far too costly to produce. The houses were shelved as being prohibitively expensive to make, with the New Zealand tally only reaching 12 (four of which Nick has owned at some point), and only about 100 were ever produced worldwide.

“I think the basis for heritage status is that it just represents such huge technological advances from back in the 1960s and ’70s”

Just a handful of Futuros remain in various parts of New Zealand today: six in Canterbury, one each in Otago and Tasman, and two near Auckland. Nick has a second one already at the back of his property –the yellow, former Bank of New Zealand one used at the Commonwealth Games – and he has plans to renovate and refurbish it in the coming year. Another he sold to the owner of the Museum of Old and New Art (MONA) in Tasmania a few years ago.

The Area 51 Futuro, which now takes pride of place on Nick’s Ōhoka property, has seen a fair bit of action, having formerly been used as a high-country station for researchers monitoring water conditions, a dog-food storage facility, and lastly a whitebait and fishing hut in South Westland.

In 2018 Nick purchased it from there and transported it painstakingly to North Canterbury, where it began its restoration journey in a large, empty paddock.

“That’s when the fun began and things spiralled out of control,” Nick jokes.

“A lot of blood, sweat and tears have gone into this project, but it’s all totally been worth it to hear the feedback from visitors now.”

Many of those tears, Nick recalls, came at 2am one night in 2021 during a ferocious storm, when part of the roof blew off.

“If I hadn’t been here, the whole inside would have been destroyed by that one event. I had to sit up on the top [of the structure] holding it down for hours, crying in the rain and wind. We had done so much work and I was so desperate to keep it dry.”

Much as Nick would be happy to live in his Futuro permanently, albeit with a slightly more subdued décor than its vivid purple and orange ’70s fitout, he has much more fun showcasing it to the general public, who can stay overnight to experience it for themselves.

He felt compelled to restore and refurbish it to reflect Suuronen’s original vision for Futuro houses, complete with genuine ’70s soft furnishings and accessories (like the arcade games and Mr Potato Head), because there are now only 68 left in the world.

1. Garish in today’s world, the colour scheme provides a fabulous glimpse into a bygone era.

2. Nick sourced materials from around the world to create a genuine retro vibe.

3. It’s small and compact but has all the facilities.

4. The sleeping areas are akin to boat cabins and have original ’60s curtain fabric.

5. The Area 51 Futuro reflects Matti Suuronen’s original vision, complete with an abundance of cushions.

“I just thought that, with such a limited number of them left, it really had to be worth preserving and making it exactly how it would have been in the ’60s and ’70s.

“Loads of people [with Futuros] have gone a bit more modern; they have changed things to suit them, but I really wanted to focus on taking it back to how it would have looked back then. That’s definitely what’s been so special about it.”

Nick sourced materials from all over the place – from Belgium and Germany to eBay and Trade Me – and the house even boasts an original yellow plastic seat by pioneering German industrial designer Luigi Colani.

“I did take a big risk – the seat alone is worth $7000 – but I wanted everything to be authentic. I really want people to experience the real deal.”

Nick’s Futuro can be rented for the night, along with the rest of the retro-themed property, and is permanently busy with tourists from all over the world. Perhaps unsurprisingly, it was crowned Airbnb NZ Best Unique Stay in 2022.

This year marks 50 years since the Futuro’s public exposure at the gates of the Commonwealth Games, so it is fitting that in February it gained heritage status as a Category 1 historic place.

“Someone from Heritage New Zealand [Pouhere Taonga] came to stay, and we just got chatting,” Nick explains. “I asked her if this was something that would be considered heritage and she

went away to find out, and that’s where the whole thing started. I think the basis for heritage status is that it represents such huge technological advances from back in the 1960s and ’70s.”

Robyn Burgess, Senior Heritage Assessment Advisor for Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga, says the inclusion of the Area 51 Futuro House in the New Zealand Heritage List/Rārangi Kōrero as a Category 1 historic place was significant for a number of reasons – not least of which was the overwhelming public support. The vast majority of the close to 100 submissions on the listing proposal were in favour of it, she says.

“The Area 51 Futuro house tells the story of a particular period in the 1970s, when New Zealand followed the international trend of the manufacture and marketing of an innovative and quirky relocatable housing alternative.

“The technology was experimental and innovative for its time, which gives it architectural significance – and with only 100 ever made, they are extremely collectable and desirable.”

Robyn says the Futuro house also has a great deal of cultural significance, reflected in its dedicated social media followers, who are keen to reminisce about this niche housing moment in time.

“From the outset, Futuros were designed for people to spend time together, and now, as rare and unusual structures from a limited time period, they continue to bring people together to experience and celebrate them,” she says.

IMAGE: SAMUEL EVANS

WORDS AND IMAGE: JILL MITCHELL-LARRIVEE

A celestial story

Located on the rugged West Coast, with panoramic views of Fox Glacier, Te Kopikopiko o te Waka is a free Tohu Whenua site where you can discover the te ao Māori creation story of Te Wai Pounamu/the South Island. Te Kopikopiko o te Waka was co-designed with mana whenua from Ngāti Mahaki ki Makaawhio and uses sculpture to give an

immersive and interactive experience for all visitors. The waka feature represents the whakapapa of mana whenua and the overarching story of the site.

I took this photo on my first visit to Te Kopikopiko o te Waka and it was quite incredible – I have a passion for Māori heritage and am lucky that my work takes me to places where I can

immerse myself in it and experience the stories. When I arrived, the clouds were hiding the glacier completely; after a while they parted to reveal the perfect view and soon after that they closed again.

The dynamic environment really reinforces that you are somewhere very special.

Technical data

• Camera: Sony ILCE-6000

• Lens: 16–50mm

• ISO: 100

• Aperture: f/9

• Exposure: 1/100

mana whenua: those with tribal authority over land or territory te ao Māori: the Māori world view whakapapa: genealogy

Patterns in nature

WORDS: JOHN O’HARE / IMAGERY: JESS BURGES

A chance encounter has revealed a previously unknown artwork by internationally acclaimed artist Friedensreich Hundertwasser in a Northland home

It was the sheer irregularity of the patterns that caught Jack Kemp’s eye; a series of asymmetrical shapes and forms – some coloured, many left blank – that adorned the verandah ceiling.

Jack had been asked to price a waterblasting job for Anthea and Justin Poihipi at their bush-enclosed home near Waipiro Bay in the Bay of Islands. Curiosity piqued, he learned that the patterns were the work of internationally renowned artist Friedensreich Regentag Dunkelbunt Hundertwasser.

“It was hard to believe,” says Jack, “but as I looked closely at the interacting shapes, the Hundertwasser influence was very clear.

“The presence of a small building close by with bottles for windows connected all the dots.”

Hundertwasser was on Jack’s mind at the time. An artist and sculptor himself, he is also a volunteer with the Northland office of Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga. He was aware of the research by Bill Edwards, Area Manager Northland, into the Hundertwasser Public Toilets in Kawakawa with a view to listing them as a Category 1 historic place.

Jack’s ‘discovery’ couldn’t have been more timely.

Bill Edwards followed up, contacting Anthea and Justin to arrange for the features to be recorded in detail

– although he got more than he bargained for. As well as measuring and photographing the artwork and studio, he met Thomas Scicli-Lauterbach, the original owner and builder of the house and studio, and co-creator of the artwork on the ceiling.

To Bill’s astonishment, Thomas produced photos of Hundertwasser himself working on the ceiling almost 40 years earlier, and recounted how the artwork came to be.

It is somewhat ironic that thanks, indirectly, can go to Ronald Reagan for Anthea and Justin’s artwork.

Concerned by Reagan’s ‘nuclear umbrella’ over Europe and the proliferation of nuclear weaponry there, Thomas and his wife Beate sought a different life far from the chill of the Cold War. They visited Australia in the early 1980s, then found themselves in New Zealand.

“I had finished six years of study in Nuremberg, graduating with a Master of Fine Arts,” says Thomas.

“My trade, however, was in stone engineering. My family ran a commercial stone company, although I didn’t want to follow in my father’s footsteps. We liked New Zealand – and Immigration said that with my skills we could move here tomorrow.”

After a year in Auckland, Thomas and Beate travelled the country, ending up in the Bay of Islands where they “fell in love with this corner of the land”.

“The idea was to reflect the fine lines of nature while bringing in a bit of colour – a bit of fun – though he didn’t want it to be completely coloured like a Hundertwasser artwork”

Alongside the area’s natural beauty, it was a friendship with Rāwhiti kaumatua Kara Hepi that provided confirmation.

“Kara said, ‘Thomas, if you want to come to New Zealand, you are welcome.’ That touched our hearts and as a result we started looking for land here,” he says.

The relationship influenced Thomas’s philosophy both on art and on life itself.

“Coming under the authority of our kaumatua meant that we began our life here with a spiritual connection,” he says.

Thomas and Beate started building their house, initially living in a tent alongside a goat and a fish tank.

“An octagonal house appealed to us, so we had the plans drawn up,” recalls Thomas.

“We started putting up the poles and people were very curious,” says Beate. “They wondered whether we were building a big roundabout!”

A feature of their home was a covered verandah overlooking Waipiro Bay. Its characteristically Kiwi fibrolite ceiling would soon become a blank canvas for one of the world’s most influential 20th-century artists.

Both Thomas and Beate had heard of Friedensreich Hundertwasser as an artist before they moved to New Zealand. Beate had owned an art gallery in Nuremberg and expected Hundertwasser to be a little arrogant because of the high prices of his prints.

Nevertheless, Thomas wanted to meet Hundertwasser as he lived close by. It was 1986 or 1987.

“I gave him a call. He was very friendly and invited us to visit him. The next day we met him for the first time at his Kaurinui Valley home,” recalls Thomas.

The instant connection grew, with Fredrick – as Hundertwasser was known to his friends – becoming a frequent visitor to the Lauterbachs’ house. And not just Fredrick.

“The first time Fredrick came here was with his then girlfriend. They both had a good time and headed home in the evening. We went to bed upstairs, and to my surprise the next morning we found them curled up on some sheepskins we had in the lounge.

“Fredrick’s Lada had broken down close by and they had hitched a ride back to our place, crept in and made themselves at home.”

1. Hundertwasser meets fibrolite –artistic expression on the ceiling of a Kiwi verandah.

2. The fine lines of nature captured by Hundertwasser and Thomas Scicli-Lauterbach.

3. ‘Bringing nature in’ –Hundertwasser al fresco overlooking the beautiful Waipiro Bay.

kaumatua: elder

It was on one of Hundertwasser’s visits that the verandah artwork was created.

“One day I told Fredrick I needed to get some paint in Kawakawa, which was like our city at the time. He asked, ‘What kind of paint?’ I said, ‘Some white or grey paint for the verandah’,” says Thomas.

“Fredrick said, ‘No, no, no’ – then got up and started drawing on the ceiling with his pencil, which he always carried with him. He said that ‘nature always has fine lines’, and that ‘you have to bring nature in’.

“He started drawing his lines, and that’s how the artwork began.”

Faced with about 15 square metres of ceiling, Thomas agreed to finish the artwork after Hundertwasser had completed the first three panels. Hundertwasser, however, would provide direction.

“Fredrick said, ‘Yes, that’s good; that’s how it should be. Not too much colour – leave it open – nature is like that.’ The idea was to reflect the fine lines of nature while bringing in a bit of colour – a bit of fun – though he didn’t want it to be completely coloured like a Hundertwasser artwork,” says Thomas.

“Fredrick gave birth to the idea, though in the end I completed it with his approval.”

Thomas was later inspired to build the studio –though Hundertwasser had some notes on that too.

“Fredrick encouraged me to use bottles for natural light,” says Thomas.

On completion, Hundertwasser, who believed that straight lines in architecture were something akin to the devil’s work, told Thomas he thought the arrangement of the bottles was too straight. But in the end he liked it and often rested on Thomas’s studio couch.

Hundertwasser was less positive about the chimney flue in their house, however. Perfectly perpendicular –just too straight! In vain he requested that Thomas put a bit of a kink in it – but even with that request, there was a reason for Hundertwasser’s apparent eccentricity.

“Fredrick’s chimney had a bend in it where condensation and soot accumulated. Fredrick added PVA glue to this residue and used it as ink for his correspondence,” says Thomas.

“The ink smelt like hell!”

Thomas remembers Hundertwasser appearing on German TV as early as the 1970s, sharing his philosophy about the need to care for the environment in order for humans to survive. It was a universal vision born out of incredible hardship.

“We’re the guardians of this artwork and we really want to do the right thing in terms of preserving it”

The child of a Catholic father and a Jewish mother, Hundertwasser survived Nazi Germany – the only one in his family to do so. His mother devised a plan as brilliant as it was terrifying: Fredrick would hide his Jewish identity by joining the Hitler Youth movement.

On a trip they once took to Vienna together, Thomas remembers, Hundertwasser pointed to a canal and talked about the dead bodies he saw floating there as a child.

In the post-war years, Hundertwasser wandered the globe – often on the cheap – with his reputation as an artist of note growing with every decade. In time, he found himself in New Zealand.

“Fredrick and I had common interests in art and conservation. He was also the closest friend I ever had, and a father figure,” says Thomas.

“When our oldest child David died in a tragic boating accident, it was Fredrick who offered for him to be buried on his land at Kaurinui. He was incredibly kind.”

Kawakawa became their hometown through good times and bad. Janet’s Hair Salon provided the necessary grooming – though Hundertwasser insisted on cutting his own hair, with perhaps predictable results, given his objection to straight lines.

Similarly, the Bonanza Takeaway Bar provided a place to meet. With some irony, the Bonanza was compared to a Viennese cafe – though any humour was offset by a strong sense of affection for the instant coffee, fried food and fun times it provided.

“We loved the place for what it was,” says Thomas.

“Fredrick could be himself in Kawakawa. Nobody knew he was a famous artist; they just saw a nice, weird old man. I remember one day, though, a German visitor recognised him and literally chased him across a field. Hundertwasser hated that kind of invasion.”

It was with genuine excitement that Hundertwasser announced to Thomas and Beate that he had been asked to design a public toilet for Kawakawa.

“Fredrick had designed a church, apartments and public buildings around the world, and he was genuinely thrilled to be asked to design the public toilets,” he says.

Beate goes further.

“The Kawakawa toilets are probably the most authentic Hundertwasser building in the world, because Fredrick was closely involved in their construction, being on site almost every day,” she says.

“In other projects, Fredrick would not have had the same hands-on involvement.”

Since opening in 2000, the toilets have put both Kawakawa and the Hundertwasser name on the map. Last year the complex entered the New Zealand Heritage List/Rārangi Kōrero as a Category 1 historic place.

Anthea and Justin have since developed a fresh appreciation for the artwork and studio they ‘inherited’ when they bought their house three years ago. Although they knew of the Hundertwasser connection, they hadn’t fully grasped its significance.

“I feel privileged, first and foremost. The longer we’re here, the more we appreciate them,” says Justin.

1. The artist’s studio – note the outside stone slab table beneath the lamp, which Hundertwasser used for his art.

2. Glass bottles diffuse light in the artist’s studio to beautiful effect.

3. Portrait of the artist creating the verandah ceiling artwork.

4. The barbecue, complete with tile mosaic.

Bill Edwards echoes the heritage significance of the artwork and studio.

“Both demonstrate the artistic process used by Hundertwasser, giving us insights into the way he worked,” he says.

“They are rare nationally, as we had direct input from Hundertwasser himself, who died in 2000. Both need to be conserved for future generations.”

Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga is providing conservation advice to Anthea and Justin to ensure that this previously little-known part of Hundertwasser’s legacy, located in a beautiful part of the artist’s beloved Northland, lives on.

“We’re the guardians of this artwork,” says Anthea, “and we really want to do the right thing in terms of preserving it.”

BRAVEnew world

Katrina McLarin and Brenda Laverick sold up in Auckland to transform a grand historic home in Ōamaru. Now they’ve been bitten by the heritage restoration bug

WORDS: ANNA DUNLOP / IMAGERY: MIKE HEYDON

“Iknew from the instant we walked through the gates,” says Katrina McLarin. “It was dilapidated, the guttering was hanging off, the grounds were horribly overgrown –but I turned to the estate agent and said, ‘Where’s the contract?’ I could see by her face that she thought I was absolutely nuts.”

Katrina is recalling the moment at the beginning of 2019 when she and her wife Brenda Laverick decided to buy Casa Nova. The couple have since transformed the 19th-century neo-Georgian mansion in Ōamaru into a high-end boutique bed and breakfast and a tapas-style restaurant – and it has now been designated a Category 1 historic place.

The couple, who at that time owned Poco Loco restaurant in Pukekohe, had just finished a biking holiday in the South Island and were driving to Christchurch to fly home. As they reached the brow of a hill on the approach to Ōamaru, Brenda looked out to the Pacific Ocean and mused that she could live there.

“We’d had our Pukekohe restaurant for a long time and were looking for something different,” says Katrina. “We weren’t quite sure what that was, but we knew we wanted a change.”

A phone call to an estate agent allowed them to view two properties that day, and while neither of them panned out, two days later – after the couple had flown back to Auckland – they found Casa Nova online. “We flew straight back down,” says Katrina.

Within three months Katrina and Brenda had bought the five-bedroom mansion and relocated their lives to the South Island to take on the mammoth restoration of one of Ōamaru’s most significant domestic buildings.

“We hadn’t set out looking for a restoration project,” says Katrina. “We didn’t actually understand the full history of the house when we bought it.”

Casa Nova was built in 1861 by Englishman Mark Noble and was the first residence in Ōamaru to be constructed from the now-famous limestone, which is believed to have been sourced from quarries near Totara Estate and Kakanui, and cut by hand.

Its construction predated any of the town’s churches, schools and other public buildings (the Category 2 Star and Garter Stables was the first, built of Ōamaru stone in 1861), meaning Casa Nova would have been a distinctive landmark in the settlement.

The two-storey house was designed by architects Thomas Glass and Michael Grenfell, and its grand style – two gables topped with finials, with a recessed entranceway between and large angled bay windows – is thought to have been inspired by Danet Hall in Leicestershire where Noble was raised (and which, coincidentally, was demolished in the same year that Casa Nova was built).

The size and formality of Casa Nova reflect the wealth of early European settlers such as Noble, who was a successful run holder.

Casa Nova translates from Italian as ‘new house’ –fitting for a new building in a new colonial settlement

“From my perspective, if it had stood there for more than 150 years then it was probably worth salvaging”

– and the origin of the house’s name can be found in Noble’s sad past, about which Katrina and Brenda discovered more last year.

The couple received an email from an engineer in Malaga, Spain, who had been researching the Noble family. He sent photos of the Noble Hospital in Malaga, built by Mark Noble’s sisters in memory of their father Dr Joseph Noble, who had died in the city. The engineer also revealed that after Mark Noble died in Malta in 1868, aged 34, he was buried in Bagni di Lucca in Tuscany, next to his young wife

who had died there 14 years earlier, aged just 20. “It was quite an amazing email to get out of the blue,” says Katrina.