Segmented turning is the result of a combination of various techniques, and there are several methods for building or constructing an item to be finished by turning. A few basic steps are needed to produce simple designs, and multiple steps and techniques are needed for more complex projects. Segmented work requires great mechanical skills, precision, and the occasional creative adoption or construction of special tools and equipment.

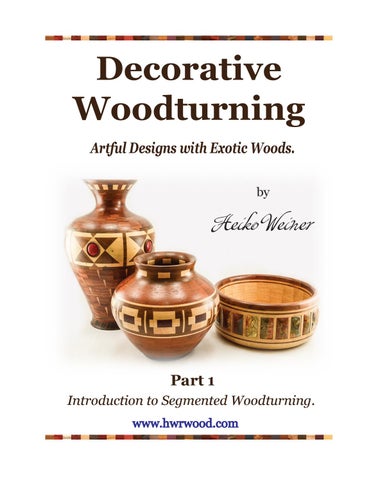

The basics of segmented woodturning are introduced in Part 1 of this series. This section includes a description of the basic terms and calculations, an introduction to common domestic and exotic hardwoods, and a description of synthetic materials. Properties and usages for adhesives and glues are discussed, and some guidance for the finishing steps is provided. The introduction also includes information on tools, equipment, and useful accessories. Finally, a chapter on tool safety, and recommendations for personal protective equipment is also included.