SPRING 2023

Publisher, Editor-in-Chief

Dylan Jones

Senior Editor, Designer

Nikki Forrester

Copy Editor

Amanda Larch

All the Other Things

Dylan Jones, Nikki Forrester

I’ve been listening to a lot of podcasts lately focused on the quintessential human concept of attention. Simply put, attention can be defined as notice being taken of someone or something. You might have heard that we’re deep in the throes of the attention economy: a financial system that views human attention as an essential commodity that can be monetized simply by getting you to spend more time on things that command your attention, like scrolling-based social media apps and streaming services.

But attention, at its core, goes much deeper than the economic system on which it is based. In an age where most of us have less attention to pay because we are incessantly paying more of it to more things for smaller periods of time, we, as a society, have forgotten how to focus. And I mean really focus. You know, turning off all those dinging distractions, buzzing bells, and whistling widgets to sit down and spend some serious time with something, anything, whether it be listening to a full album with your eyes closed, reading a book in silence, or just existing as a wild animal in a natural setting.

Which, naturally, brings us to this magazine you hold in your hands. As you make your way through this issue, I invite you to pay attention to it. Look critically at the photographs and the layout. Think about how the words look on the page; one of my favorite aspects of writing is the artful

intricacy of how certain words and phrases look in print as you sound them out in your mind. Take note of the white space on the page between those images and words— empty space, like those satisfying pauses between notes in a song, says just as much because it’s saying nothing. Notice how the light from where you’re sitting, whether it be natural light through a window or soft light from a lamp, illuminates and reflects off the page.

Next, consider going deeper and pay attention to what you’re paying attention to. How do you flip through the magazine the first time? What are you focusing on? Are you primarily looking at the photographs? Are you reading the titles or photo captions before reading the stories? This practice has taught me a lot about myself and how I interact with the world around me.

Nikki and I pour our creative efforts into making Highland Outdoors a truly unique experience—everything you see in these 52 glossy pages was done with intention, all the way down to the ad placements (and now I sound like an exec in the attention economy).

Suffice it to say, we love print as a medium for sharing West Virginia’s amazing outdoor stories, and we are thrilled to share another issue with you. Now that we’ve got another one under our belts, I have no attention left to pay to anything else, so I think I’ll go sit on a rock in the forest and stare at the trees. w

Suzanne Atkinson, Rick Burgess, Tom Cecil, AJ DeLauder, Nikki Forrester, Brian Gratwicke, Caleb Hills, Dylan Jones, Rue McKenrick, Malee Oot, Nathaniel Peck, Mick Posey, Patrick Shadle, Ann Szilagyi, Attila Szilagyi, Andrew Walker, Jun Yip, Jay Young

Get every issue of Highland Outdoors mailed straight to your door or buy a gift subscription for a friend. Sign up at highland-outdoors.com/store/

ADVERTISING

Request a media kit or send inquiries to info@highland-outdoors.com

SUBMISSIONS

Please send pitches and photos to dylan@highland-outdoors.com

EDITORIAL POLICY

Our editorial content is not influenced by advertisers.

Highland Outdoors is printed on ecofriendy paper and is a carbon-neutral business certifed by Aclymate. Please consider passing this issue along or recycling it when you’re done.

Outdoor activities are inherently risky. Highland Outdoors will not be held responsible for your decision to play outdoors.

COVER

A barred owl (Strix varia), photo by Nathaniel Peck.

Copyright © 2023 by Highland Outdoors. All rights reserved.

By Nikki Forrester

By Nikki Forrester

Hellbender lovers, rejoice! On January 1, the West Virginia Department of Natural Resources (DNR) launched a citizen science project asking residents and visitors to share their hellbender and mudpuppy sightings. The eastern hellbender (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis) and common mudpuppy (Necturus maculosus) are the only two fully aquatic salamanders in the Mountain State. They typically live in cool, clear streams that are well oxygenated, serving as indicators of stream quality. “Water quality is important not only for the wildlife, but also for every aspect of our community,” said Kevin Oxenrider, the amphibian and reptile program leader for the DNR.

Since the early 1990s, hellbender populations have declined by nearly 80% due to habitat loss, sedimentation, impoundments, dams, pollutants, and deforestation. Now, hellbenders are listed as a regional species of conservation need across the Northeast. In West Virginia, hellbenders have been found in larger streams in the western portion of the state, but far less is known about mudpuppies. “We haven’t been tracking their distribution very well,” Oxenrider said, adding that this citizen science project is the DNR’s first attempt to generate data on where mudpuppies are distributed, which

can help inform the conservation status of the species.

Citizen science projects bring professional scientists and members of the public together to collect data and gain new scientific insights about the natural world. At first, Oxenrider was skeptical that a citizen science project would work for documenting hellbenders and mudpuppies, since people don’t often come into contact with them. But after browsing through various fishing websites and social media groups, Oxenrider noticed quite a few people were posting about accidentally catching these species. “It quickly became apparent that they were catching those animals in places that we had no idea they existed,” he said.

Over the course of the two-year project, any member of the public can submit observations through a survey on the DNR website or the Survey123 mobile app. Oxenrider said they’re curious about any spotting of a hellbender or mudpuppy, not only those from fishing bycatch. The survey asks which species was observed or caught, location information, and a photo (if one is available) to help verify the observation. Mudpuppies have exposed gills, whereas hellbenders don’t, providing an easy feature for distinguishing the

two. For those without cell service, the app collects GPS location data and uploads the observation once service is acquired. “One thing that we try to stress to folks is that information is confidential. The only reason we collect contact information is in case we have any questions and we want to talk to you more about your observation,” he described.

People have already submitted 40 hellbender and mudpuppy observations since the program started in early 2023. Some of these observations are from several years ago. “That’s amazing information to have because that allows us to see historical distribution versus what’s happening now,” Oxenrider said.

Along with collecting better data about the distribution of hellbenders and mudpuppies in West Virginia, Oxenrider hopes the program will help raise awareness about these salamanders. “People think both species impact sport fish populations, that’s not true,” he said. These salamanders, which aren’t venomous, consume crayfish, invertebrates, worms, and occasionally a minnow. “They’re not causing problems for people.”

The hellbender and mudpuppy survey follows in the footsteps of two other citizen science projects led by Oxenrider. The first project, which is ongoing, tracks timber rattlesnakes and has resulted in 485 observations to date. The second was a box turtle project, which generated more than 8,000 observations. “West Virginia is now seen as having the largest box turtle database of any state. We have the public to thank for that,” he said.

Citizen science is a great way to get the public involved in science projects, said Oxenrider. “It allows the public to take some ownership over the scientific process and the conservation process of their natural resources. And I think it’s just fun.” w

To learn more, visit www.wvdnr.gov/ hellbender-mudpuppy-survey.

By Dylan Jones

By Dylan Jones

In January of 2023, the New River Alliance of Climbers (NRAC) introduced a scholarship honoring the life of Dr. Paul Nelson, a beloved Fayetteville community member, climber, and NRAC board member who passed away in July of 2021.

NRAC is a local climbing organization dedicated to preserving and promoting access to climbing areas in the New River Gorge region. NRAC president Matt Carpenter said the organization is proud to offer the scholarship to serve Nelson’s legacy. “The years I spent adventuring with Paul taught me so much about myself and the world, and I have an endless supply of fond memories and endearing stories to look back on thanks to Paul,” Carpenter said. “This scholarship will carry on his legacy by supporting the education of another young person who holds his same values.”

Beyond his notorious first ascents of harrowing climbing routes in the New River Gorge, Nelson was a musician, historian, educator, and consummate entertainer known for his wit and encyclopedic knowledge. Nelson was also a friend of Highland Outdoors who penned several articles about climbing over the years.

After talking with Paul’s wife Miranda Nelson, the NRAC board decided a scholarship was the ideal way to honor him and further his life’s work. “Since Paul was an educator and a musician and was committed to climbing, the best way to truly embody Paul’s spirit would be to help someone get an education and pursue their dreams,” said Carpenter.

The scholarship will be offered annually to a student who shares Nelson’s love for learning and conservation. Specifically, Carpenter said NRAC is searching for an undergraduate or graduate student who is a climber who regularly visits the New River Gorge. The selected scholar will be asked to create a project to promote stewardship of the New River Gorge region.

“Paul loved what he did as an educator, he loved contributing to and being an active member of the climbing community, and he loved entertaining with stories and music,” Carpenter said. “There’s still a huge hole in our community that’s been left from his passing. We’re happy to do anything we can to help pass on his legacy.” w

The City of Beckley is hedging its bet on outdoor recreation with Beckley Outdoors, a comprehensive economic plan that seeks to leverage the New River Gorge region’s burgeoning outdoor economy. The plan, which combines tourism development, a soft-surface trails plan, business and workforce development, and downtown revitalization into a single package, is the first of its kind in West Virginia.

Beckley is West Virginia’s ninth-largest city with a population of just over 17,000. According to Corey Lilly, director of outdoor economic development for the City of Beckley, the “holistic initiative” is Beckley’s first step in becoming the face of Southern West Virginia. “Beckley is the population hub of the region, so we’re looking to be the model outdoor city for West Virginia—not just as somewhere where you go and recreate, but as somewhere that you want to live.”

Beckley Outdoors consists of four pillars: conservation and stewardship, education and workforce training, economic development, and public health and wellness. The city recently approved a $300,000 budget for the initial one-year planning stage that will guide development of the comprehensive plan. “The outdoor economy is taking root around the region, but Beckley has been a little bit behind. This plan moves us to the forefront and creates a roadmap for the next 15 years of investments to ignite Beckley’s outdoor recreation economy,” Lilly said.

According to Beckley Mayor Rob Rappold, Beckley’s most unique asset is the Piney Creek Gorge, a rugged and scenic natural area within city limits that boasts waterfalls, hiking trails, and opportunities for rock climbing, whitewater paddling, and mountain biking. Rappold said the city is working closely with Marshall University on remediating impacted sections of the gorge via brownfields grants as well as with the West Virginia Land Trust, which owns 800 forested acres in the gorge. “The Piney Creek Gorge, which is in the city limits and has gone unnoticed until recently, has wonderful rock climbing and trail opportunities; it’s our centerpiece of the plan.”

Lilly said the first step is to implement recreation infrastructure. “If you don’t have outdoor infrastructure, you won’t have an outdoor economy,” Lilly said. Developing infrastructure within the city is also essential, he said. For example, he envisions people mountain biking downtown during their lunch breaks.

“People are taking outdoor activities into account when considering where they want to live, so we think that the outdoor economy action plan will become Beckley’s competitive advantage,” Rappold said. “We’re embracing the natural beauty we have and working hard to create a destination where people want to come and fall in love with it.” w

To learn more, visit beckleyoutdoors.com.

Iknow my home county pretty well. Or at least I thought I did. I’ve spent the majority of my 37 years living in Preston County; nearly two of those decades have been spent pedaling my mountain bike around the serpentine dirt roads and green valleys so quintessential to this heavenly slice of the Allegheny Plateau.

I can tell someone the quickest or the safest ways from Rowlesburg to Aurora. I’ve ridden, and sometimes bushwhacked, the seemingly forgotten Allegheny Trail from its northern terminus north of Bruceton Mills straight south for 70 miles through Preston County, the fourth-largest county in West Virginia, before reaching the higher elevations of Tucker County. I can close my eyes and describe what the ancient mountains look like when the sun sets from the crest of Evan’s Curve outside Terra Alta, and how descending the railtrail next to Decker’s Creek feels on a hot summer morning.

But as the years passed, my appreciation of Preston County’s rural splendor began to wear thin. I slowly forgot how captivating my native mountains could be. For starters, Preston County doesn’t get much press beyond the semi-famous Buckwheat Festival, a four-day extravaganza celebrating a crop largely grown in places other than Preston County (a great way to upset a local is to describe buckwheat cakes as pancakes). In the northern realm of the county, one can find Big Bear Lake and its ever-expanding network of outstanding trails, but media coverage rarely mentions that Big Bear exists entirely within Preston County. Take a look at news clippings about Wisp Ski Resort just over the border in Maryland, and you’ll see Garrett County mentioned countless times. The same goes for Tucker County and its plethora of outdoor offerings from ski resorts and hiking trails to breweries and music venues.

Preston County, however, remains as terra perdita—a lost land—overshadowed by its wealthier neighbors and largely absent from discussions about locations in West Virginia that have substantial outdoor recreation possibilities. Essentially, Preston County is mostly written off by visitors, a place more associated with quiet workaday Appalachian life than stunning vistas, a culture that’s more Walmart than R.E.I.

In my experience, many of us who grew up here or have lived here for a long period of time have become numb to the spectacular beauty and exceptional outdoor opportunities surrounding us. We’re like someone who’s been standing next to a fire on a cold night for too long: we no longer recognize the value of the warmth we’re receiving until we step away. Instead, we stay put, fixating on the economic and societal shortcomings of the county and begrudging the place we must call home.

Paradoxically, we’re simultaneously defensive of what we have to the point that we guard against outsiders—and even against our own—who propose any semblance of change. We embrace being forgotten because it means being left alone, and, until recently, I could count myself among the guilty.

What changed for me was breaking away from the familiar and recognizing there were still parts of the county I had never seen. There were still unexplored roads and adventures to be had. The possibility of which became clearer and clearer as I sat down to plan a bikepacking race that would traverse Preston County south to north along backroads I only vaguely knew.

Bikepacking is a mash-up of camping and long-distance biking, typically along gravel roads, doubletrack, or even mild singletrack. If you’ve ridden from Cumberland, MD, to Washington D.C. on the C&O Canal, you’ve likely been a bikepacker. In the old days—like way back in the 1990s —a cyclist might have said they were going “touring” by doing what bikepackers now do, albeit with slightly different bikes and gear-packing methods.

There are a few differences, though. Bikepackers, especially bikepacking racers, tend to focus on light, minimalist set-ups that allow them to ride as far and as fast as possible. Think bivy sacks, lightweight sleeping bags, and maybe one change of clothes for multiple days on the bike. If you enjoy hip and shoulder pain

and a lack of sleep, bikepack racing may be right for you.

But there’s so much more to bikepacking than gear and distance. The bikepacking scene is a tight-knit community of inclusive and encouraging folks who value pushing boundaries and immersing themselves in nature. I don’t quite yet know why bikepacking is so addictive when it’s such a painful sport, but indeed it is—enough for me to engage in the painstaking undertaking of planning my own race.

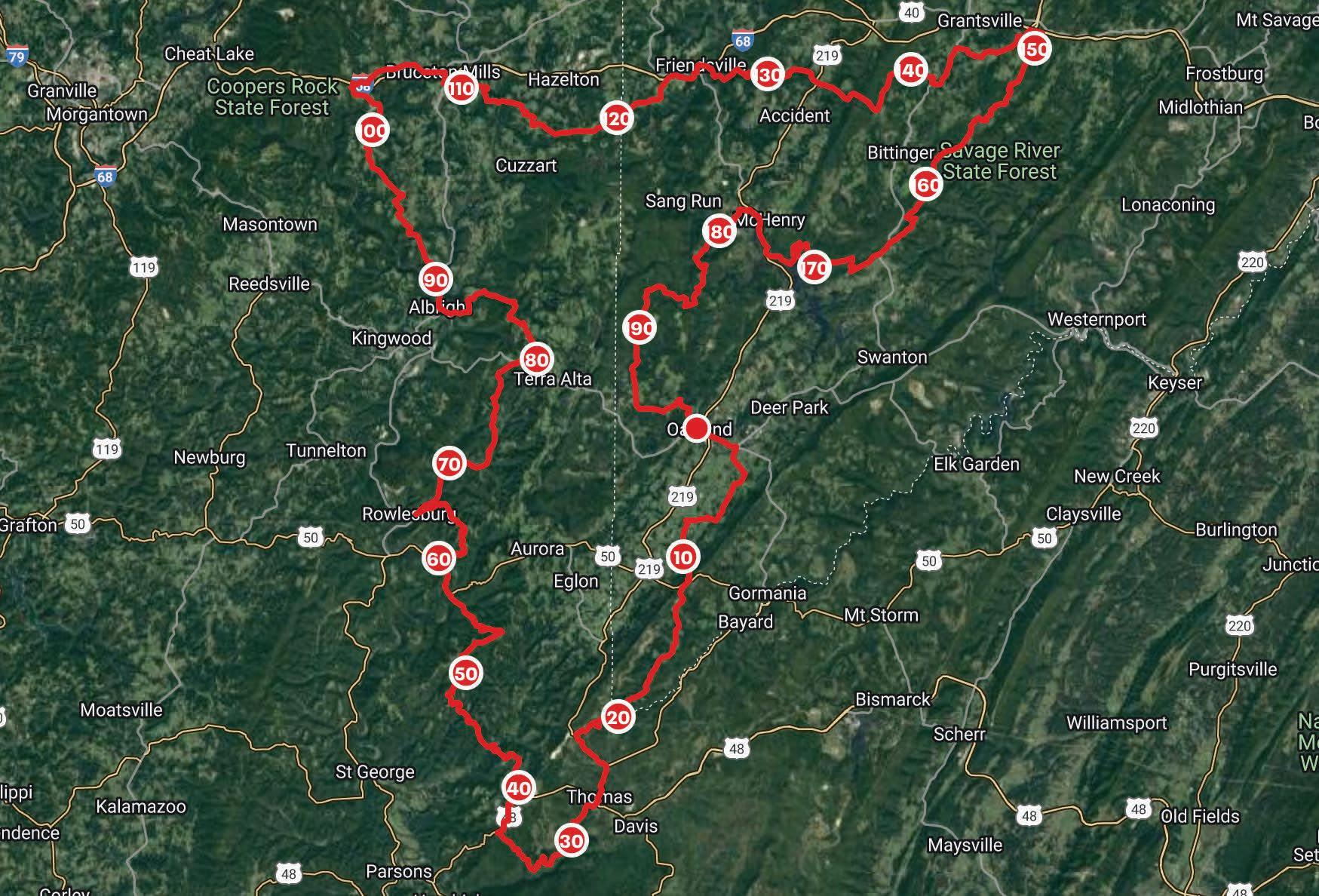

In December of 2021, I began scouting backroads on various maps and cycling apps. I pulled out my Allegheny Trail handbook and took notes as the snow fell. Hour by hour, turn by turn, the route took form as winter progressed. I picked a start date of mid-September to avoid the heat of the summer. I named the event The Snallygaster 200 in homage to the hardy German settlers of western Maryland and northeastern West Virginia who kept their children in line by conjuring up tales of Snallygasters—giant flying reptiles that lurked in the mountains.

The race would start and end at The Tiny Corner Bike Shop, the seasonal bike shop I own in Oakland, MD. My logo features a Tyrannosaurus rex atop a penny-farthing bicycle, and because Snallygasters are dinosaur-adjacent creatures, the name and imagery of the race seemed even more apropos.

From Oakland, the route would head south for a quick dip into Tucker County around Thomas before dropping off

Backbone Mountain to Leadmine and climbing back toward Stemple Ridge and Aurora, where I live. This would mark the route’s entrance into Preston County. We would then descend the long way down the chunky gravel of Snake Road and climb the merciless stairstep-style ascent up Mount Olivet Church Road to Lantz Ridge, leading to a 1,500-foot descent toward Rowlesburg, a small town on the banks of the Cheat River. From there, the route would head directly north up Salt Lick Road before detouring through the hamlet of Rodamer and climbing back up to Terra Alta. A notoriously rocky and rowdy descent colloquially known as Peddler’s Glory would drop racers back down on the Cheat in Albright. Beyond Albright, the route stitches together a patchwork of pavement and dirt roads to cross the Big Sandy River en route to Bruceton Mills. The route then makes a final turn east out of Preston County by way of Cuzzart toward Friendsville, MD, with a final north-to-south traverse of Garrett County, MD, to complete the loop. In total, the route would be 198 miles with over 22,000 feet of climbing, nearly half of which would take place on dirt roads.

As I dropped pin after pin on my online map and the red line of the route grew longer, a small worry in the back of my mind blossomed into a larger sense of dread. What if this route wasn’t good enough? What if my home land of Preston County wasn’t sufficiently spectacular for such an overwhelming investment of someone’s time and energy? Would racers

pedal away disgruntled? Why even showcase an area that no one seemed to care about in the first place? I ultimately decided that I couldn’t make a decision about the route’s worthiness until I scouted the roads myself.

In late February of 2022, an unusual streak of warm weather hit the area. I took a few days off from my winter job as a snowboard instructor and loaded my bikepacking bags to see if my creation was worth not only my time, but others’ time as well.

I started from my home in Aurora and churned up the long, burning climb to Lantz Ridge to meet the route. My GPS beeped happily as I joined the track I’d so painstakingly composed. I felt elated to be out adventuring this early in the year, but soon found the wow-factor just wasn’t there for me. I knew what I would see and it was, well, what I’d already seen countless times. The sense of dread weighed heavily as my emotional numbness to the scenery lingered. I wondered when—or if for that matter—it would eventually rescind.

Despite the mountainous terrain, this mental flatness continued past Terra Alta, through the jarring descent of Peddler’s Glory, and into the deep, cool valley surrounding Albright. However, once I started climbing Beech Run Road to leave the familiar cradle of the Cheat River behind, a new world appeared— one that carried the same name of Preston County, but suddenly free from any mental imprints I had transcribed over the years.

Each pedal stroke brought fresh miles and new surroundings. As the sun began to set and the North Star appeared above the horizon, I found myself staring across an unknown plain of pastoral farmland at a dusky silhouette of mountains that were not my own and yet very much were. Suddenly, almost painfully, I felt the beauty of that calm, winter moment. I wanted to cry for the sheer fact that I could still cry over a place that had been my home for so many years. I wanted to wrap my arms around this land that pulls me and pushes me and refuses to let my heart go quiet.

I kept pedaling for another four hours as darkness settled around me, making my way across the top of Pres-

ton and Garrett counties before finding an overgrown field near the start of the Meadow Mountain Trail, which marked the route’s final turn southward. From my hillside camp among faded grass and dormant briars, I could see the glare of white lights from the truck stops on Chestnut Ridge and headlights whipping across Interstate 68. Sitting there in the dark, removed from the bustle of society, I felt a bittersweet pang of detachment and loneliness. What I wished more than anything was to shout out my newfound appreciation to the people hurrying past, to shake them from their cars and say, “Look! Look at how magnificent this all is! Can you believe this is our home?”

But I knew that was impossible. Insight of the type I’d just experienced often comes with a proportional price tag of effort. I paid that price by riding nearly 100 miles of rough backroads and long climbs over the past 11 hours, and discovered immense value in that suffering. Many in Preston County, sadly, would be unlikely to undertake such an effort. Some might even laugh at the prospect of riding a bike for so long, and thus a gift of awareness like I’d been given would go unrealized. I finally settled my thoughts by remembering that I was sharing my joy by creating this route, and that by introducing other cyclists to the beauty of my home, I would shed light on a forgotten place and provide a pathway to appreciation for those who cared to see.

Thirty-six hours after I left Aurora, I completed the Snallygaster 200 route and arrived home covered in mud and sweat. A few early season daffodils were poking out of my mushy yard. I collapsed into a dusty wicker chair on my back porch as a breeze of lukewarm air spilled across my face. I felt awestruck, as if I’d just emerged from a dream. But this dream wasn’t one of far-off lands or towering, snow-capped crags. It was a dream of quiet, green mountains and dusty gravel roads, a place I once again felt proud to call my own. w

AJ DeLauder (they/them) is the owner of The Tiny Corner Bike Shop in Oakland, MD, and a visiting professor of English at Garrett College. They love long rides and putting far too much maple syrup on buckwheat cakes.

Dirty Double #1

Terra Alta, WV at Alpine Lake Resort // May 13

Gravel Ride Up Spruce Knob #2

Circleville, WV // July 6 - 9

Kate’s Mountain Challenge #3

White Sulphur Springs, WV // July 22

Lost River Classic #4

Mathias, WV // August 12

Rollin Coal #5

Shinnston, WV // September 23

proudly sponsored by..

www.wvgravelseries.com

Two penguins are paddling a canoe through a desert. The penguin in front turns to the penguin in back and says, “Wears your paddle.” The second penguin says, “Sure does.”

So goes the classic and cryptic joke that has resulted in a cultlike following among a disparate group of friends. While being able to read the grammatical clue to deciphering the riddlesque punchline makes it easy for you, dear reader, I highly recommend telling it to someone—the reflexive laugh you’ll immediately receive soon followed by a deeply puzzled look will be well worth your 10 seconds of effort.

“Wears your paddle” is not only the primary point of confusion in the aforementioned joke; it’s also a mantra that my wife Nikki and I have adopted as we’ve voluntarily undertaken a slew of low-water paddling expeditions over the years. And while we don’t have any deserts in which to paddle, we certainly have worn our paddles—and raft—down via incessant contact with various riparian substrates.

Most extreme sports require extraordinary environmental variables to be labeled as such. Low-water paddling, however, isn’t extreme. Rather, it’s X-stream (get it? because no water means it’s an ex-stream).

Simply put, low-water paddling is the act of paddling a craft down a river currently possessing an abnormally low amount of water. As a river’s flow, often measured as a real-time metric in cubic feet per second (CFS), drops, the substrate—the material constituting the riverbed—becomes closer to the water surface, eventually becoming completely exposed.

In other words, as the bottom drops out, a waterway becomes exponentially less navigable. A hypothetical river might offer a clean ride over a range of several thousand CFS, but at a certain point, a drop of just a few hundred CFS can result in a drastically different paddling experience. At 1,000 CFS in this hypothetical river, you’ve got your optimal flow for a fun run. Let’s say it drops down to 500 CFS. You’ll still get a good trip, but might bump a few rocks here and there, only having to exit the boat once in a shallow riffle to pull it a few feet to deeper water. But if our imaginary river drops to 400 CFS, you’ll be bopping off countless boulders and have to hop out of the boat at least 10 times to drag it through the entire length of the gravel bars that form the shallow riffles between deep pools.

You’ll scuff your rubberized raft or scrape your canoe over a variety of submerged and exposed textures, often wearing down the material and leaving paint marks on pointy rocks. You’ll bang your paddle around in the riffles and ding the blade as you leverage it between boulders like a fulcrum on which to spin the raft when you invariably get hung up on a stealth rock. You’re going to beat the shit out of your gear and shorten its lifespan. But as we say, sometimes it’s either low paddling or no paddling.

Most reasonable folks who engage in year-round paddling in West Virginia have a quiver of aquatic crafts to suit variable conditions. Nikki and I, however, own only one boat: a limegreen cataraft that we affectionately call The Booger. At 12 feet long, six feet wide, and robust enough to carry four people, The Booger is not necessarily what you’d call a nimble craft. However, it’s incredibly capable of crushing class V rapids on the Gauley and is ideal for hauling gear on overnight outings.

The beloved Booger, geared up for an X-stream adventure. Here she is in “Cadillac Mode,” featuring plush seats rigged onto the pontoons for the most luxurious of paddling experiences.

Given the exponentially decreasing amount of floating you can do as the flow drops, assessing one’s ability—and tolerance—to run a section at the lowest-possible level can involve some intense calculus. To be frank, there’s no actual limit to how low you can run a river. Theoretically, you could get geared up in neoprene and a PFD, grab a paddle in one hand, and simply drag your rig with the other across a bone-dry riverbed. Is it technically paddling? No, not really. But does it qualify as low-water paddling? I’d argue that it at least merits spirited (bourbon is my preference) debate.

Every year in April, we embark on an annual pilgrimage to float the Smoke Hole Canyon—a ruggedly spectacular wonderland where the South Branch Potomac River cuts a deep gorge through Pendleton and Grant counties. Because the South Branch Potomac flows through the rain shadow of the Allegheny Front and to the east of North Fork Mountain—the driest single ridgeline in the entire Appalachian Mountain range—it is a low-flow rio that typically offers a brief window of reliable levels for paddling in early spring.

American Whitewater, the go-to source for river levels and paddling beta across the country, lists the Smoke Hole Canyon as having a minimum recommended level of 2.5 feet on the United States Geologic Survey (USGS) gauge at Franklin, meaning that anything lower is likely to be scrapey (or bony in boater speak).

In May 2020, the first year we paddled the Smoke Hole, the river was steady at a juicy level of 3.3 feet.

The Booger floated over the substrate at a steady click, requiring a few paddle strokes here and there to keep the boat tracking straight in the current. The class III Landslide Rapid was easily navigable from a technical standpoint—none of the large rocks that create the rapid were exposed—and the only challenge came in avoiding a large hole in the middle of a frothy pour-over.

In late April 2021, the South Branch Potomac was at 2.4 feet—just a smidge below the recommended level. But given our newfound love for this world-class stretch of river, we decided to test the waters and see just how low we could go. We found that The Booger, despite its hulking size, was somehow nimble enough to navigate the maze of bump rocks that cause problems once the gauge drops below 2.5 feet. Landslide, with several of its large boulders exposed, was more technical but still a breeze for our crew. The trip involved a few drag-aboats, but nothing too horrendous. We decided that we would definitely run the Smoke Hole at 2.4 feet again, American Whitewater’s suggestion be damned!

Last year, as the annual trip approached, our building anticipation was offset by waning excitement as the river level was low with no rain in the forecast. The day of the float, the USGS gauge was at a paltry 2.17 feet and dropping. We were faced with two options: stay home and endure the inevitable FOMO of wishing we were out in one of our favorite places, or go endure the inevitable torture of dragging our boat down a considerable percentage of the Smoke Hole Canyon’s 16+ river miles. The choice was obvious: go and endure!

Nikki and I loaded up The Booger with all the hefty

comforts necessary for a luxurious overnight trip—a dry bag with spare clothes, tent, and sleeping gear; a dry box filled with a two-burner stove and fuel, an iron skillet, French press, and many other camp kitchen accoutrement; a collapsible table on which to place said gear; two camp chairs; a backgammon board; and a cooler filled to the brim with you-guess-what. As Nikki and I hoisted The Booger and waddled it to the put-in, we exchanged nervous glances. The sage advice of my friend Owen rattled in my skull: If the rio is low, you can still go. Leave the luxury items at home and go ultralight backpacking-style.

The first rapid, usually a fun train of small-but-splashy waves, looked like a trickly riffle that would undoubtedly be a bony, bumpy ride—if we even made it through to begin with. Naturally, with our boat sitting low and heavy in the water, we hit the first visible rock and stopped completely. We sat there and sighed as our wise friends who run the Smoke Hole in canoes sent the riffle clean with maybe a few scrapes. We huffed and got out of The Booger, grabbing the webbing tied along the pontoons’ length and started yanking it along the rounded river rocks. In case you didn’t know, rubber is sticky and doesn’t like to slide along anything with ease. The canoeists drifted ahead, getting smaller and smaller as we reached the end of the riffle, defeated at the thought of 15.8 more miles of hell.

Fortunately, big, deep pools punctuate the benign rapids and riffles of the South Branch Potomac, providing easy passage and rest between bouts of taking The Booger for a walk. We munched snacks and sipped adult beverages in the flatwater, gazing up at the towering limestone cliffs as members of our crew cast lines from their canoes. All was well on the Smoke Hole.

Right before one particularly spectacular bend in the canyon, the river splits into two parallel channels and drops in elevation over a 100-yard-long boulder garden, offering paddlers a choice. We eyed up the options; the right channel appeared to have less water and more pointy rocks to contend with. Knowing we’d probably end up walking either way, we decided to test our luck on the left channel.

Navigating an extended rocky riffle requires intense substrate scrutiny for choosing an optimal micro-line. When you enter a combat situation like that, a clean line is no longer an option. You’d best strap your seatbelt on and put that tray table in the upright position, cause it’s about to get turbulent. The fine line between success and failure boils down to possessing supreme boat awareness. You must be able to immediately identify which rocks you can straddle between the pontoons and which rocks you can successfully bump to set you up for the next hit. Because once you get off-line, there’s no recovering. Beyond your water-reading ability, advanced maneuvers are often required. You might have to intentionally snag a tube on a rock, bounce up and down on the tubes to induce temporary buoyancy, and take the requisite paddle strokes to throw a full 360-degree spin before breaking free—anything to avoid getting out of the boat.

Into the cascading riffle we went, utilizing every low-water paddling skill in the toolbox. We maintained laser-focus as we bopped down the fork, relying on our fine-tuned rapport to operate as a team without saying much. Each successive rock bump and spin move inched us closer to the big pool below—we started to think we might actually have a chance. Left here! Backstroke there!

Watch out for that rock! Hit this one! Lift yer ass up to unweight the pontoon! As we scraped off the final rock and entered the eddy of the big pool at the bottom of the slide, we whooped and hollered as if we had just successfully survived a class V rapid on the Upper Gauley, despite a near-zero chance of death.

Miles later, still very much at the back of the pack, we approached the Landslide rapid. I stood up in the floor of the boat to get a look and gulped as a jumbled maze of jagged boulders lay in place of what, in previous years, had been a river-wide rapid. There was but one navigable path through the jumble, and it barely looked wide enough for The Booger. Over the incessant white noise of the whitewater, I shouted commands at Nikki to take a backstroke, rudder, and paddle hard forward as I echoed the sequence of paddle strokes. We slotted into the drop perfectly and immediately heard the familiar squeaky, smudgy sound of rubber on rock as we wedged between two boulders. We sat there for a moment before the surge of water behind The Booger—now serving as a cork for a majority of the river—popped us out into the swirling pool below. Thrilled that we made it through without having to exit the boat amid the biggest rapid, we tapped paddle blades before eddying out and mooring The Booger to a tree at our riverside campsite.

The next morning, I woke with a pounding headache from the night’s revelry and stumbled down to the cobbled shore to dip my face in the cold water. The Booger, which most definitely had not moved on its own volition, was significantly more beached than when we first parked it. My heart dropped, but not nearly as much as the river had overnight.

But the inevitable trials and tribulations would have to wait— we were still enjoying the high vibes of river camp and had a hearty meal to enjoy. Our friend Geo cheffed up his classic Smoke Hole breakfast of freshly harvested ramps, morels, and trout. We brewed pot after pot of coffee, sure to make heavy use of the heavy kitchen gear. Some things, like a riverside breakfast with your favorite people, can only be accomplished via arduous effort. Another one of Owen’s aphorisms drifted through my blissed-out brain: To suffer now means greatness later. Lounging in the sun under the neon-green sycamore leaves, I thought about how we sat in the calming eye of the storm between bouts of suffering.

As we broke down camp and secured our gear in The Booger, anxiety crept back in as the second bout of suffering was about to begin. We knew we had about 11 miles of paddling—and boat dragging—between us and the take-out in Petersburg. By now, you can guess how the remainder of the trip went: blissful periods of floating through pools punctuated by fuming bouts of taking our fully loaded boat for an aquatic hike. After one particularly long schlep, we made the executive decision that, to reduce weight, we had to drink and eat everything left in the cooler.

The highpoint of the day was our famous charcuterie lunch, an annual tradition that is presented and enjoyed at the confluence where the North Fork of the South Branch of the Potomac River (affectionately referred to as the NoFoSoBraPotomo) joins the South Branch proper. As each member of the flotilla added delicacies like cured meats, smoked oysters, and fine cheeses to the spread, the sense of camaraderie that comes standard with group outings grew with the smorgasbord. We joked that the only reason we go and do these hair-brained adventures is to enjoy classy meals in pristine locales.

Once the NoFoSoBraPotomo adds its crystalline waters to the South Branch, the river swells in size, meaning that the tortuous part of the journey was (mostly) over. While we still bumped and scraped along several shallow riffles, the experience was closer to a traditional rafting trip. As we pulled up to the take-out and broke down The Booger, we experienced a familiar emotional paradox, simultaneously elated that the hard work was done but deflated that another glorious journey down the Smoke Hole had come to an end.

When we got home, I checked the USGS gauge records to see just how low the South Branch Potomac had fallen. By the time we took off, the river had dropped to 1.9 feet, smashing our previous low record and setting an absolute minimum level at which we would most definitely, positively, never, ever run it again… or would we? w

Dylan Jones is publisher of Highland Outdoors and would like to publicly apologize to our beloved Booger for all the aquatic abuse we’ve put her through.

It’s a calm spring evening in the Allegheny Mountains. With close to 40 pounds of camera gear in my backpack, I’m awkwardly weaving through the dense understory of a deciduous forest, closely following a small path beaten down by wildlife. I’m on the trail of one of the most iconic animals in the east, the black bear (Ursus americanus). Frequent piles of seed-filled scat along the path tell me I’m looking in the right place.

Just ahead, the game trail leads through a small, mossy patch—a perfect spot to set up my camera trap. I unload my gear and start the hours-long process of setting up my system.

Camera trapping is the art of leaving stationary digital cameras outdoors to capture high-quality images of nocturnal or elusive animals in their natural habitat. A camera trapping kit usually includes a digital camera, a motion detector, and several off-camera flashes. When an animal walks past the motion detector, a signal is instantly sent to the camera and flashes, telling them to wake up and take a picture.

When choosing a composition, I try my best to imagine where the animal I’m hoping to photograph—in this case, the bear—might be walking, resting, or feeding. I decide to point the camera perpendicular to the trail and set up the off-camera flashes—these will illuminate the picture if the bear, or anything else, strolls by at night.

After setting the motion detector up and taking some test shots, it’s time for me to leave the scene. Now the waiting game begins. I’ll return in a week to change the camera batteries and check the memory card to see if I captured any worthy shots.

While I love spending time outdoors to capture handheld images of my favorite animals, some creatures—no matter how good of a tracker you are—are nearly impossible to find and photograph in person. In those cases, camera trapping allows me to capture extremely high-resolution photos of animals—often engaged in candid behaviors—that we are unlikely to see with our own eyes.

Although camera trapping might seem lazy to some, a lot of painstaking work goes into getting the perfect image. Simply setting up the camera at a random location in the woods and hoping an animal walks by usually results in failure. Having extensive animal tracking knowledge—such as being able to identify footprints and scat they leave behind, or being able to pattern their movements so you know where they’ll be—is extremely useful for camera trapping, as it helps you find signs like animal trails, scent posts, carcasses, and dens.

But even after finding an ideal spot, it can still take months or even years of fine-tuning the process before capturing that dream photo. Oftentimes, the motion sensor picks up on the wind and takes a thousand photos in a single day, draining the camera’s battery. Or maybe a curious bear comes by, knocking the camera over as it sniffs around. Alternatively, flashes can malfunction and misfire, resulting in a dark image even though the motion sensor and camera successfully did their jobs. Beyond the technical difficulties, animals can smell your musky human scent on the camera and often won’t approach it. Speaking of scents, a camera trap by a carcass might result in thousands of images of scavenging birds that quickly fill the memory cards and drain the batteries. These are but a few hardships that camera trappers face, but the hard work—and frustration—is worth it when you check your camera and find your dream photo on the screen.

One of the most captivating animals in the Central Appalachians is the fisher (Pekania pennanti ), a large,

carnivorous member of the mustelid family. I’ve made it my life’s work to photograph them, and they appear frequently as subjects in my camera trap work. But they sure don’t make it easy to get good images of them. Most of my winter days are spent following their tracks for miles through the most rugged parts of our snowy forests, hoping their trails will lead me to a carcass on which they’ll return time and time again to feed, or to a scent post on which they frequently urinate and defecate to communicate with each other.

I’ll never forget the first time I got a photograph of a fisher on my camera trap. As soon as I saw the image, I sat on the ground crying with excitement for a few minutes while frantically texting everyone I knew. Looking back after several years of tracking and photographing fishers, the image is objectively pretty bad, but I’ll forever cherish that feeling of all my hard work paying off. For me, there’s nothing more rewarding than a successful fisher photo.

Over the years, I’ve been fortunate to document a lot of rarely seen wildlife and interesting behavior on my camera trap. One time, I was setting up a camera pointed at a mossy log near a trail in a dense rhododendron thicket in hopes that something would stroll by and hop on the log. When I checked the trap a few weeks later, I was quite surprised to find that a bear had visited the log just an hour after I had finished setting up the camera.

More recently, I was setting up by a deer carcass, hoping that a fisher would come in. For several weeks, nothing but an opossum (Didelphis virginiana) stopped by. I was changing the batteries weekly and was very close to moving the camera when I noticed a new visitor, my beloved fisher. Based on the small size, I could tell this fisher was a female, and much to my surprise, she had shown up at the same time as the opossum and tried to fight it off the carcass. While her attempt did not

Clockwise from top left: A red-tailed hawk swoops down for a treat; raccoons (Procyon lotor) feast on a carcass; a porcupine (Erethizon dorsatum) trods across snow; an opossum (Didelphis virginiana) caught in the act; a fisher (Pekania pennanti ) says cheeeeeeese; a nosy black bear (Ursus americanus) walks the plank.

Previous: A black bear searching for snacks.

work, she did come back a few hours later when the opossum had left and was able to dine in peace.

One of my all-time favorite experiences was finding and photographing a porcupine (Erethizon dorsatum) den deep in the backcountry. I found a small cave and noticed lots of porcupine scat at the entrance. I set up a trail cam and came back a month later, finding that it had filmed hundreds of videos of porcupines, so I knew I had to install a proper camera trap to capture a high-quality image. But I didn’t want to set up right beside the den and stress them out, so I waited until it snowed and followed their tracks a few hundred yards from the den to set up along one of their common trails. Over the next few weeks, I was lucky enough to capture several images of them traversing their trails at night, likely along the way to feed on their preferred tree bark.

While I mostly pursue handheld photography, camera trapping is one of the only ways I’ve found to capture candid images of natural animal behavior, completely free of the ever-encroaching influence of humans. This unique form of photography has allowed me to experience wildlife in a way otherwise not possible. I hope that sharing these rare images of otherwise elusive animals can inspire us all to work together to promote their conservation. w

Nathaniel Peck is an avid nature photographer focusing on the landscapes, wildlife, and caves of the Allegheny Highlands.

BY DYLAN JONES

BY DYLAN JONES

At high noon on a beautiful fall day last year, Joel Brady pulled himself atop the narrow fin of Seneca Rocks after an hour-plus battle on the rock. He looked around at the stunning valley surrounding the Mountain State’s iconic pinnacle and became overwhelmed with emotion.

Brady had just completed the first free ascent of the Green Wall—a blank and vertical cliff on Seneca’s South Summit aptly named for the neon-colored crustose lichen that creates striking patches contrasting the white quartzite face. After nearly 100 attempts, Brady finally found his way up the great wall without error. In doing so, he etched his name into proverbial stone by establishing Seneca’s newest and hardest climbing route.

Although Brady’s ability to free-climb the Green Wall clean (meaning without falling or weighting his rope) took around six months, the story of the route was years in the making. In the mid-twenty-tens, Andrew Leich, a rock climber and route developer based in Morgantown, was regularly visiting Seneca to scale its legendary cliffs. Leich would often wrap up his day with a cool-down lap on Green Wall (5.7), a moderate traditional climbing route (meaning the climber places temporary gear in cracks and seams in the rock for protection) that ascends a system of cracks and corners to the right of the actual Green Wall. “I kept looking over at how incredible the face is and started noticing little shadows and features that looked like holds,” Leich says.

Leich, always on the lookout for a challenge, had his friend take a photo of him standing on a ledge atop the Green Wall. They zoomed in on the image to hunt for potential holds in the interest of finding a route up what many climbers had cast off as an impossibly blank face.

It should be noted that the Green Wall has technically been climbed before, first ascended by Harrison Shull in the 1990s as an aid route named A Whiter Shade of Pale. Aid climbing is an increasingly passé style where gear is placed into the rock and pulled on to ascend a wall, meaning that the aid practitioner isn’t always climbing the rock itself.

But Leich envisioned free-climbing the Green Wall, meaning the climber places gear for safety purposes but only gains upward progress by using the natural holds in the rock. To do so, he would need to enlist a dedicated partner. Leich invited Brady—the two have been ticking off hard climbing projects together for seven years—to analyze the photo of the Green Wall. The pair knew it would be a classic climbing challenge, filled with uncertainty, drama, and, hopefully, success. “I knew it would be a huge undertaking, but because Andrew and I work so well together, I had a sense it would be achievable and enjoyable,” Brady says.

Brady, a 42-year-old religious studies professor at the University of Pittsburgh, is low-key famous for several things: his celebrated collegiate course on vampires, his appearance in 2015 as a contestant on American Ninja Warrior, and his first ascents of exceedingly hard sport climbing (meaning permanent bolts are drilled into the wall to serve as protection points) routes in the New River Gorge region. But there was one catch: Brady, a 30-year climbing veteran, had never been to the traditional climbing mecca of Seneca Rocks. “For me, Seneca was aways the place I would go whenever I couldn’t do hardcore climbing anymore,” Brady says. “It was an outlandish idea to go where I’d never climbed before and immediately attempt the hardest route.”

Before the climbing could commence, the team had to decide how to equip the route. In rock climbing, ethics matter—especially at a traditional climbing destination like Seneca, where old-school dogma often views placing bolts in the rock as heresy. Let the record state that there are a handful of sport climbs at Seneca, but hardcore traditionalists tend to scoff at adding new bolts.

Leich and Brady could stay true to the Seneca ethic and go ground-up, meaning climbing the route in an exploratory manner with no knowledge of where they might find protection points. This is a method often used in traditional climbing because the questing climber is likely—although not guaranteed—to encounter weaknesses in the rock in which to place protection. But the Green Wall is extremely blank and offers virtually no placements for trad gear, meaning a ground-up attempt would likely result in horror.

In February of 2022, Brady and Leich took the pilgrimage to Seneca to begin their work. They made the call to rappel down beside each other to get a hands-on look at the imposing wall, finding more holds than expected. “It just absolutely blew our minds as we found each section could go,” Leich says. “A large portion of the Green Wall is of high quartzite content that features perfect lines of sharp, little crimp holds.”

Their initial inspection of the route found some rusty rivets and copperheads—aging remnants of Shull’s original aid gear bashed into the rock. While working the route, Brady weighted one of the copperheads, which immediately exploded out of the rock. “After thirty years exposed to the elements, it was total junk,” he says.

With Shull’s gear out of the question and only one marginal traditional gear placement, there were no options left but to bolt. “The only real placement was a blind reach with a super-small piece that most certainly wouldn’t hold you in a fall, and you’d

have to climb 5.14 moves to even get to it,” Leich says. “It would have been certain death.”

The team wanted to equip the line while making sure it aligned with the bold Seneca ethic. They consulted several Seneca regulars, including longtime local Tom Cecil, a prolific first ascentionist and owner of Seneca Rocks Mountain Guides. Cecil agreed that bolts would need to be placed to make the route safe enough not just for them, but also for any future climbers who might want to test their mettle and live to tell the tale.

Knowing it was too dangerous to place the bolts while climbing on lead from the ground, they decided to rap-bolt the line, meaning rappelling from the top of the cliff and placing bolts in the wall while hanging safely in their harnesses. If placing even one bolt at a traditional climbing crag is heresy to the orthodox trad climber, rap-bolting a sport route is total blasphemy—an unforgivable sin that might result in the bolts being removed.

But even with Cecil’s blessing, the team wanted to avoid confrontation while placing bolts, hoping instead that the route would speak for itself once it had been completed.

They placed just seven bolts over the 90-foot length of the Green Wall’s blank face to a set of existing anchors on the ledge above the hardest portion of climbing. After the ledge, they opted to leave the final 35 feet of climbing as is, meaning any suitors would have to bring a few pieces of trad gear to safely gain the summit following the bolted portion of the show. “To me, that just captures the spirit of the Seneca ethic. We didn’t indiscriminately just start slapping bolts into the route, we thought very carefully about it,” Brady said.

With the route safely equipped, it was time to piece together the sequence of moves required to reach the top. In climbing, this process is called projecting, an arduous undertaking that often requires months—or even years—to unlock routes of the hardest difficulty levels. Brady and Leich are no strangers to projecting; both have completed first ascents in the 5.14 and 5.13 range, respectively.

Climbing at this level requires extreme precision and efficient movement to conserve energy. Through projecting a route, one can get to a point where the moves feel secure, offering a greater chance of success. “Imagine a rubber band running from the tips of your fingers all the way down through your body to the tips of your toes; you have to keep that rubber band tight to stay on the wall. If you have any inefficiencies along the way, the rubber band goes slack and you fall,” says Brady.

The hardest series of moves in a route is called the crux. The crux can be just a single move, or it can be a cryptic sequence of movements that must be perfectly linked together. Brady described one portion of the crux in detail:

“You start with both hands above your head, in opposition to each other on thin, slippery edges in the rock that can fit just an eighth of a fingertip. At this point, it’s critical to move your right foot about eight inches to the right to a very glassy foothold that’s barely discernable. You have to focus on engaging your shoulders and back just right in order to take enough weight off of your foot to move it. At first, I was trying to just move my foot and kept falling. But I discovered that if I planted my knee against the wall, I could use it as a fulcrum that allowed me to maintain just enough body tension to carefully swing my foot to the bad foothold. There are about five individual movements that go into moving one foot

eight inches, and that move is just one of the 11 technical moves in this crux sequence. I fell on every single one of those moves as I was trying to work through it.

As the project dragged into summer, the duo adapted their schedule to avoid peak heat and humidity. Brady and Leich found they could productively climb from 8 p.m. to 1 a.m., or from 6 a.m. to 11 a.m., when the sun would crest Seneca’s fin and beat down on the west-facing walls. “The extremely friction-dependent moves become impossible when sweating in the sun,” Brady says.

The climbing itself was hard enough, but Brady, a father of four, says balancing family time and work with his goal of completing the project presented an additional challenge. Brady says his wife and extended family were incredibly supportive. “You have to figure out how to make up for that time away and be intentional about devoting time to your family when you are there,” he says. “Sometimes I’d be lying in bed at 10 at night, unable to fall asleep. On a whim, I’d be like I’ve got to go to Seneca . You can only do that so much.”

Brady estimates he made upwards of 100 attempts on the route over a span of 25 individual days from March to October 2022, often spending two hours hanging in his harness while trying to decipher the sequence of moves required to delicately dance his way up the blank wall.

On the morning of October 15, 2022, Brady met up with Matt O’Brien, one of several local Seneca climbers who had been filling in as belayer when Leich was unable to make the trip. In perfect conditions, Brady, as he had done nearly 100 times before, entered the crux sequence.

“He let out some grunts and threw up his right hand, and I saw

his body slowly peel away from the wall,” O’Brien says. “I saw this huge loop of slack in the rope and Joel was waving his limbs in the air as he came down in a giant fall.”

Fortunately for Brady, O’Brien is an expert belayer and provided him with a soft, safe catch. “It was one of the smoothest falls I’ve ever had,” Brady says. “When I got lowered back to the start of the route, Matt was shaking his head with this wide-eyed look.”

Now that Brady had safely taken his largest fall—nearly 40 feet—near the end of the crux section, he was able to shift his full attention to the moves. Brady asked O’Brien for the two pieces of trad gear required to reach the summit, signaling his mental preparedness for completing the route. “That was the first time he had asked me for those pieces; I really think he believed he was going to make it,” O’Brien says.

But this time, as Brady approached the crux, he spotted a section of rock above it. “I looked at that spot and told myself that I wanted to be above the crux, looking down at where I currently was,” he says.

Up he went, performing the sequence of moves he had rehearsed so many times before. Everything felt right, including the move to the bad foothold. “He’s usually always grunting, but this time, he was silently floating up the rock effortlessly, like he was weightless in the gentle breeze,” says O’Brien.

Suddenly, Brady was above the crux, looking down at the spot where he had made his affirmation just moments prior. But with difficult climbing ahead, he wasn’t ready to celebrate just yet. “I got stressed because there was still some fairly tenuous climbing that was getting in my head a little bit,” he says. “I took a deep breath and thought, This is it. This is the one where you’re doing it. Just enjoy the moment.”

He let out a celebratory shout as he gained a ledge just big enough to lie down on, resting for nearly 20 minutes before ascending the final 35 feet of traditional climbing.

After over an hour on the rock, Brady pulled himself atop the South Peak of Seneca Rocks and broke down into tears. His thoughts immediately shifted to his close friend Michael Brown, a lifelong climber who had passed away the day before following a battle with cancer.

The week before Brown died, his wife invited Brady to visit after Brown was moved to his childhood home on hospice care. Brown told Brady a story about his favorite pig that found its way into his neighborhood when he was a kid. “I leaned back, thinking Is he really talking about pigs on his deathbed? ” says Brady. “Then he grabbed me and looked around with this gleam in his eyes. I leaned in and he quietly said, ‘There’s magic in the hills.’ Shortly after that, we prayed together and he fell asleep.”

As Brady was processing all the emotional events of the past week, he knew what he would call the newly minted climb. In honor of Michael Brown, and in part paying homage to the epic wall he had just ascended, he named the route Green Magic in the Hills.

After rappelling back down to meet O’Brien at the start of the route, the two embraced. “It was an emotional tidal wave,” says O’Brien. “We looked at the line, at this beautiful day we were having, and just soaked it in. Joel was especially appreciative of the people in his life that allow him to do this kind of stuff. It was a heavy moment that was a long time in the making.”

Brady bestowed Green Magic in the Hills a difficulty rating of 5.14b, adding the first 5.14 climb to Seneca’s storied climbing history. Previously, the hardest route at Seneca was Flyin’ Lion (5.13d), a steep and harrowing sport route first climbed by Matt Fanning in 2019.

Leich says he’s proud of Brady but is sad he wasn’t there for Brady’s historic ascent. He will continue working toward his first ascent of Green Magic in the Hills this year. “I’m really excited to have contributed to it,” Leich says. “I think it’s gonna build quite a reputation as a nails-hard classic because it’s not gonna go down easy for anybody.”

Before they started the project, Brady and Leich agreed that they would call the route a team ascent, regardless of who finished it first. “This is ultimately a joint partner project,” Brady says. “I don’t care how long it takes Andrew to do it. We did this thing together.” w

Dylan Jones is a has-been climber who is currently training for his ascent of Green Magic in the Hills. But first, he needs to build a time machine to go back to his twenties.

OFFERING FLEXIBLE FINANCING AND SMALL BUSINESS SUPPORT THROUGHOUT THE MON FOREST REGION

GROW YOUR BUSINESS WITH woodlandswv.org

By Andrew R. Walker

By Andrew R. Walker

Editor’s Note: This is the first in a series about the outdoor recreation economy and its role in shaping the social, cultural, and physical landscapes in West Virginia. This story will introduce the outdoor recreation economy through the eyes of someone who was drawn to and is supported by the wealth of outdoor opportunities in the Mountain State. Now, he’s in a position to help shape the future through his role as the executive director of the Mountaineer Trail Network Recreation Authority.

In August of 2002, I packed up everything I owned into my first car, quit my lucrative high school job as a grill cook at the local ice cream shop, and shoved off from my comfortable hometown in Massachusetts to move to West Virginia. It was an ambitious first step given that I had no job lined up, no place to live, and had yet to find out if I would be accepted to West Virginia University in the fall. I arrived in Morgantown to a humid jungle filled with dense green mountains, friendly people, and new-to-me Appalachian culture.

Growing up in the mountains of New England, I was an avid backpacker, snowboarder, paddler, and runner before moving to West Virginia. Knowing I needed a job to support myself through school, it was important to find a job I’d enjoy. After some youthful persistence, I eventually landed an entry-level position as a sales associate at Pathfinder of West Virginia, Morgantown’s local gear shop. Although I was extremely green and didn’t know much about sales or how to link people with the right outdoor equipment, the staff was willing to show me the ropes.

In the coming weeks and months, I would sign off on my first rental apartment, get accepted to West Virginia University, and buy my first mountain bike so I could join my new coworkers and friends on group rides. Those first few years were spent immersing myself in the mountains, rivers, and culture of West Virginia: long road bike rides with little-to-no sleep on the weekends, after-work trips to local ski resorts, and late-night excursions with the outdoor community that welcomed me with open arms.

Although I didn’t know it at the time, there was a hidden actor that was supporting me as I entered this next phase of my life. It paid my bills, introduced me to new friends, took me on adventures, and kept me healthy in both mind and body. That actor was the outdoor recreation economy, and my path to where I am today would not be the same without it.

During COVID-19, millions ventured outside when indoor activities were sidelined, resulting in West Virginia’s outdoor resources being pushed to the limit. Public lands were flooded with new visitors, local housing was bought up by out-of-state residents, and an influx of new organizations centered around outdoor recreation sprouted to meet the development needs for this burgeoning market.

With all this new activity, the possibility for West Virginia’s residents and longtime local organizations to be conflicted regarding the best course of action has become painstak-

ingly evident. While outdoor recreation can provide an economic boost for local communities, it can also cause negative impacts by degrading natural areas and stressing the local housing markets. As we grow our outdoor recreation economy in West Virginia, it’s important that we empower residents and local organizations to improve the health and wealth of the communities they represent. But before we get too far into the woods, we must define the outdoor recreation economy, which includes a wide variety of sectors in its net.

I like to define outdoor recreation broadly as any activity taking place in a natural environment. People with different identities, cultures, backgrounds, and social networks often choose to live in or visit West Virginia because of the wealth

of adventure opportunities here. These recreationists often organize themselves into social clubs, community advocacy groups, and educational and environmental non-profits to support and expand outdoor access.

Outdoor recreation directly impacts our local, state, and regional economies via consumer activity across myriad businesses, like companies that manufacture outdoor gear, apparel, and accessories. Local retailers sell these goods, often offering advice and support to their customers. Outfitters supply rental equipment, and guide services lead participants on adventure trips. The outdoor recreation economy also supports service industry businesses, like gas stations, restaurants, breweries, coffee shops, and art galleries, that offer amenities and entertainment

for both residents and tourists in outdoor destinations.

Lodging, such as motels, rental homes, RV campgrounds, and wilderness tent sites, is vital for folks visiting from far away. Not only do these businesses ebb and flow with the seasons, but so too do the local convention and visitors bureaus that often see operational funding come directly from hotel and motel taxes.

Each year more than half of Americans spend time and money in public lands like national parks and forests, state recreation areas, private resorts, and municipal parks. According to its 2017 study on the outdoor recreation economy, the Outdoor Industry Association (OIA) reported that Americans spent upwards of $887 billion

on outdoor recreation, leading to roughly 7.6 million jobs and over $65 million in federal income tax revenue.

These numbers are only the tip of the iceberg regarding what outdoor recreation can do on a local level in rural communities. In its 2017 report, the OIA found that the outdoor recreation sector was the fourth largest economic driver in the United States, showing greater revenues than pharmaceuticals, gasoline and fuel, and education.

As West Virginia moves further into a transition economy where fossil fuels and other extractive industries are no longer the dominant economic drivers they once were, the outdoor recreation economy has shown promise to help rebuild communities that have been negatively impacted by the industrial decline. For instance, the outdoor recreation economy can enhance job growth, state and local education, protection of wild lands, and improvements to local and state infrastructure.

Outdoor recreation assets can also incentivize larger outdoor companies to move to West Virginia, promoting high-paying jobs, competitive work environments, and additional revenues to communities in need. According to OIA’s 2017 report, spending in the snow sports and hunting sectors alone led to over 850,000 US jobs—more than Apple, Microsoft, and all mineral extraction industries combined.

The environmental aspect of the outdoor recreation economy has become more prominent as communities in West Virginia look to promote healthy activities while also protecting the land. But the uptick in visitors is causing concern about environmental degradation, prompting a rise in new organizations looking to share the load with existing organizations that have long been working to protect and conserve the state’s wild places.

In 2021, I received my master’s in public administration from West Virginia University. Historically, West Virginia has seen an exodus of intellectual capital leaving the state, and it has been rewarding to stay and utilize my education, experiences, and relationships to work directly on causes I feel so passionately about.

In October of 2022, I was hired as the first executive director of the fledgling Mountaineer Trail Network Recreation Authority (MTNRA), a multi-county organization focusing on identifying, enhancing, and promoting outdoor recreation opportunities as economic drivers for local communities. In many ways, this position feels like a culmination of the relationships and professional opportunities I’ve been so fortunate to build over the past two decades.

As executive director, I feel a heavy responsibility to administer our network and build the relationships needed to move the MTNRA—and with it, the outdoor recreation economy—forward in West Virginia. For our work to be sustainable, conversations with local communities will be essential.

We must address the need for infrastructure development within these outdoor recreation communities. In recent years, overcrowding and housing shortages—often unintended consequences of tourism-related growth—have arrived in areas like Fayetteville and Canaan Valley, leaving many locals and seasonal workers without a place to live. For many, the purchase of afford-

able housing options by out-of-state residents to use as second homes or additional revenue sources has left communities struggling to shore up housing inventory. We must find creative options, such as the construction of subsidized affordable housing or local short-term rental ordinances, that welcome new residents while encouraging locals to remain.

With the recent influx of visitors and residents, the need for improved roads, wastewater treatment facilities, broadband access, education funding, and emergency services can all be seen as pinchpoints. West Virginia will do well if its communities and organizations work together to solve these problems. It’s paramount to promote a culture of shared growth within these communities. We must understand that no one organization knows all the solutions and that collaboration offers the best chance of reaching intended outcomes. With this collaborative mindset, the MTNRA and organizations like it can help steward progress in West Virginia.

2022 was the twenty-year mark of being a West Virginia resident, and I’m proud

to say that I have now lived in West Virginia longer than I did in Massachusetts. After two decades of working in the outdoor recreation economy, I can say with certainty that it has provided me with more opportunities than I could ever have dreamed of. I want to expand these opportunities for every citizen that wants to stay in or move to West Virginia. And with every new business that opens and every new trail that is built, the opportunities for work and community expand.

We have already seen what is possible when businesses and people rally around outdoor recreation with places like Snowshoe in Pocahontas County, Canaan Valley in Tucker County, and Fayetteville in the New River Gorge region. These communities recognized their outdoor recreation assets and attracted people and resources to create opportunities for growth and quality of life for residents. The ability to improve and promote more of what this state has to offer is just around the corner, and we have never had more development organizations tasked with that challenge than we do at this moment.

But we must be thoughtful as we move into this next phase of economic development. Outdoor recreation includes a

wide array of user groups sharing relatively small tracts of land. Relationships and common bonds must be created and reinforced between those groups to foster shared use of these common spaces. We would do well to acknowledge that outdoor recreation comes in many different forms.

As it often does, the arrival of an opportunity raises new questions. How will we work together to make sure that these resources are shared and that the goals of past and current community members are considered? How will we tackle the need for infrastructure development, affordable housing, and environmental stewardship? These issues need to be addressed to holistically improve our rural communities. West Virginia presented me with an opportunity, and my life has been forever changed by answering the call of this state’s outdoor recreation economy. My hope is that we can collaboratively move West Virginia forward by answering this new call together. w

May 26 - 28

ArtSpring

Showcasing the Arts

Tucker County, WV

Sep 29Oct. 1

ARTober FEST

Timberline Mountain

January 12 Local Music

Showcase

Purple Fiddle, Thomas

In the summer of 2019, Rue McKenrick set off on an epic hike. His plan was simple: walk a counterclockwise lap around the continental United States. His mission, however, was a bit more complex: map a 14,000-mile route, dubbed the American Perimeter Trail (APT), that would become the country’s newest long-distance trail. With everything he’d need packed efficiently on his back, McKenrick headed south from his home in Bend, Oregon. “When I left, I had $400, a dream, and gear older than me,” McKenrick said.

A longtime trail advocate, McKenrick has worked for a handful of non-profits, including the Appalachian Mountain Club, Outward Bound, and the Appalachian Trail Conservancy, which is headquartered in Harpers Ferry where the Appalachian Trail runs just four miles through West Virginia.

These days, McKenrick considers himself a professional backpacker. Now in his early forties, McKenrick’s hiking resume is quite impressive. He’s completed America’s so-called Triple Crown of Hiking—a trio of long-distance

routes that includes the 2,190-mile Appalachian Trail, the 3,100-mile Continental Divide Trail, and the 2,650-mile Pacific Crest Trail.

He hopes the APT, which links portions of these iconic routes to some of the country’s lesser-known footpaths, will be added to the roster of National Scenic Trails. “I love backpacking; I love the recreation aspect. But the base of our mission is actually a conservation effort to create this corridor that goes around the United States,” McKenrick said.

The inaugural mapping trip took McKenrick a little more than three years to complete, but not all that time was spent hiking. He was forced to suspend his trek a handful of times, driven off the trail by perilous weather, medical emergencies, and unimaginable personal tragedies, including the sudden loss of his brother, Michael, in spring 2021. When McKenrick finally completed his loop around the country last October, he’d racked up nearly 25 months of continuous hiking and traversed 22 states. Most of that time, he was hiking alone. “It’s just you out there

by yourself; this was definitely a solitary trip,” he said.

McKenrick’s isolation was, in part, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic that began to unfold about eight months into his journey. In spring 2020, while trekking across the lower south toward the western edge of the Appalachian Mountains, statewide closures paralyzed travel and changed the trajectory of his route.

In the midst of the uncertainty wrought by the pandemic, trail organizations—including the Appalachian Trail Conservancy and the Pacific Crest Trail Association—were advising backpackers to postpone their trips. “It looked it was over,” McKenrick said.

But instead of quitting, he devised a strategy that would minimize human encounters by avoiding towns and relying on mail for resupplies instead. “I would see a postmaster every one or two weeks, and that was it,” he said.

As he approached the Southern Appalachians, McKenrick made another pivotal choice—he would cross the elongated mountain range into West Virginia to

avoid a significant portion of the Appalachian Trail, meaning trail communities and creature comforts would be scarce.

In May of 2020, almost a year into his trip, McKenrick walked into the Mountain State along the western flank of Peters Mountain, a windblown ridgeline that helps funnel more than a dozen species of migrating raptors southward every fall. On the crest of Peters Mountain, he bid farewell to the Appalachian Trail and began his journey on the Allegheny Trail—a rarely-traveled 330-mile path that traverses the Alleghenies all the way to the Pennsylvania border.

Trekking north, he entered the southern edge of the Monongahela National Forest near Neola. He walked through ceaseless rains along the cave-riddled shale barrens of the Greenbrier Valley, skirted a 13,000-acre National Radio Quiet Zone near Green Bank, and meandered through one of the state’s remaining stands of old-growth red spruce atop Shavers Mountain. After following the Cheat River northward, he finally reached the Allegheny Trail’s northern terminus near the town of Bruceton Mills.