MEET THE JUDGES

I am honored to have a fantastic panel of judges joining me to help select the winning photographs. Each judge brings a unique perspective and set of skills to the panel, and all have had many photos—including cover shots—published in the mag throughout the years.

DYLAN JONES

Dylan Jones is co-publisher and editor-in-chief of Highland Outdoors and lives in Davis, WV. He sorta got tired of “living behind the lens” but has recently rediscovered his love for photography. However, he still ends up bringing only his crappy smartphone camera on all his hairbrained outdoor adventures, using the tired excuse that his nice camera is too heavy. Besides Highland Outdoors, he’s had his images published in the National Geographic Explorer’s Journal , Wonderful West Virginia , Harvest Hollow, Adventure Journal , Garden & Gun, and West Virginia ArtWorks. He’s exhibited images in the annual Cortland Acres Photography Exhibit and maintains a dusty gallery in the corner of Stumptown Ales in Davis—you should probably stop in and buy one!

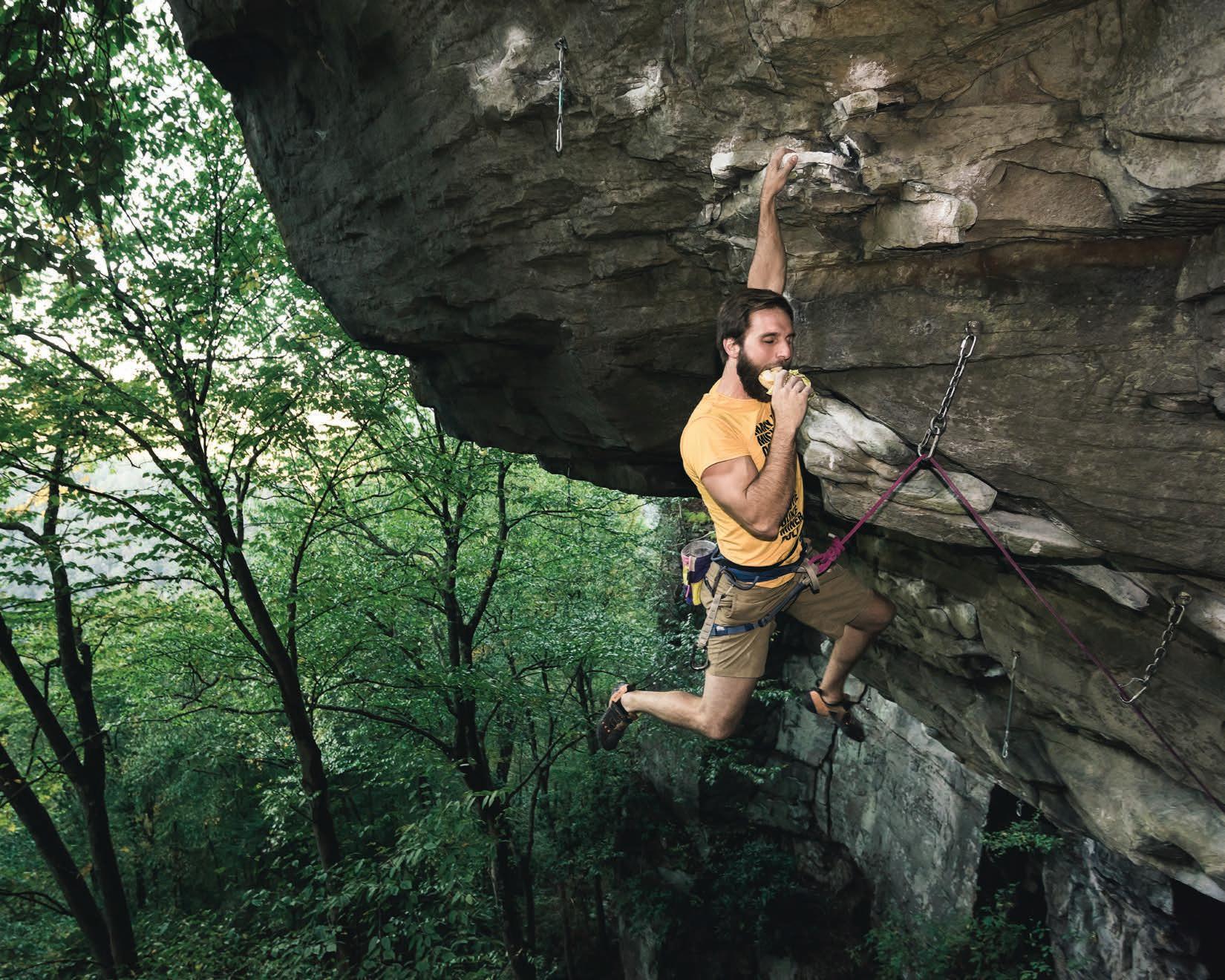

Karen Lane is a climber, designer, and photographer living in Fayetteville, WV. Originally an avid whitewater kayaker, Lane fell in love with climbing during her first trip to the New River Gorge and has never looked back. In fact, she had been dreaming of living in the gorge since age 13. Now that she’s here, Lane spends her time climbing and adventuring around the gorge, documenting these local experiences through photographs of climbing, river surfing, and the river’s stunning landscapes. Her creative documentation has caught the eye of outdoor brands such as RedBull, Black Diamond, and Mountain Hardwear. She’s been published in Highland Outdoors, Climbing Magazine, Clearline Zine, Summit Journal , Kayak Session Magazine, RedBull Illume, and RedBulletin .

JAY YOUNG

HANNAH SNYDER

Hannah Snyder is a part-time wedding and portrait photographer native to Tucker County. She’s the operations coordinator and social media manager for the West Virginia chapter of The Nature Conservancy (TNC), where she photographs TNC’s majestic preserves. Hannah developed an appreciation for photography at an early age alongside her father Andrew Snyder as he photographed Canaan Valley’s ski resort culture. While she always had a pointand-shoot camera in her hand growing up, Snyder didn’t start her professional photography journey until 2015. She still enjoys taking landscape photos around West Virginia and on road trips. Outside of TNC, Hannah’s work has been published in Highland Outdoors, WV Living, WV Executive, and Goldenseal .

Jay Young is a photographer and videographer who currently resides in Fayetteville, where he barely makes a living taking pictures of things. He originally moved to the New River Gorge in 2005 with his wife so they could be close to climbable rock, but now he’s too broken down for that and would rather run rivers, because all you really have to do for that is just sit in a boat. Young recently wrote an article for Highland Outdoors that was critically panned and universally booed. But he scored the cover shot for this issue, which is good, as he was just about ready to hang it all up. And just so there’s no misunderstanding, Jay Young loves his life, family, his community, and his job dearly. Any insinuation otherwise is another one of his pathetic attempts at sarcasm.

KAREN LANE

Courtesy of the judges

By Amanda Larch

Any steward of the land will say you can’t bring people to a river if it’s dirty. Over the decades, West Virginia’s waterways have had a rough go. Some streams were so polluted from industry that the water was deemed unsafe for wildlife and human-use. But thanks to tireless community efforts, many of the state’s rivers are hitting the spotlight once again—this time with news of clean water, renewed life, and a focus on recreation for all.

With 16 flatwater trails, the paddling, fishing, and floating opportunities are seemingly boundless in West Virginia. Local economies, communities, and riparian environments are flourishing along these aquatic corridors. Across the Mountain State, annual flatwater events like the Tour de Coal, Meet the Cheat, and the Guyandotte River Regatta continue to draw paddlers from far and wide.

Although significantly calmer than whitewater, flatwater paddling offers plenty of opportunities for aquatic adventure. These trails are just as crucial to the Mountain State’s burgeoning tourism sector as their rooty, rocky counterparts. And with an ever-expanding flatwater trail system courtesy of the West Virginia Flatwater Trails Commission (WVFTC), which was created by the state legislature in 2021 to promote and provide guidance for flatwater trails, they’re garnering increasing attention. Each region boasts its own water trails, many of which offer year-round paddling. And thanks to the WVFTC, it’s easier than ever for new ones to be established.

COAL’D WATER

Flowing through the historic town of St. Albans, the 88-mile Coal River Water Trail (CRWT) was the first official flatwater trail in

WEST VIRGINIA’S FLATWATER TRAILS ARE ON THE RISE

the state, according to WVFTC President Bill Currey. When the trail was established in the early 2000s, there was no precedent for statewide water trail certification. “We created [the water trail] ourselves and went to the state and asked that they certify us, so we’d be official, and they said we don’t have any laws to govern certification,” Currey recalls.

In a paddle stroke of luck, Jim Hudson, a member of the Coal River Group (CRG), which was initially formed to clean up the river, also happened to work for the state at the Department of Highways. Hudson drew on his experiences with the CRG to draft the rules for water trail accreditation and leveraged his connections in state government to get them in front of the legislature. “Water trails require a lot of infrastructure, and if they’re certified, they qualify for a whole lot of grant funding,” Currey says. “The CRG has led the way in securing grants.”

During this year’s legislative session, the WVFTC participated in Senate hearings in the hopes of securing more funds for flatwater trails throughout the state. “The hearing brought to light how important water trails are becoming to these areas,” says Currey.

Nowadays, the Tour de Coal, which has grown to become the nation’s largest flatwater kayak gathering, brings volunteers and visitors to St. Albans and focuses attention on the state’s growing water trail network.

Through meticulous tracking, Currey and his team determined the Coal River has more than 15,000 users each year, and the St. Albans region continues to welcome new businesses. As the CRWT expands into Lincoln County, more boat launches and cleanups will generate additional tourism for that portion of the river.

The CRG has created 20 boat launches over the years, and the WVFTC is working with the Department of Highways to establish a uniform boat launch sign. “We’re constantly raising funds to improve the water trail. We have so many out-of-state paddlers

coming in on a regular basis through the season that the use of vacation rentals has grown tremendously,” Currey says. “Economics come with hard work.”

A TUG IN THE RIGHT DIRECTION

The 60-mile Bloody Mingo Tug Fork River Water Trail, headquartered in Williamson, is bringing hundreds of people to the Mingo County area. John Burchett, treasurer of the Friends of the Tug Fork River (FOTF), also sits on the WVFTC.

FOTF initially formed as a Facebook group in 2016 for users to share fishing stories and get involved with river cleanup effort. As it grew, Burchett, who was also involved with other Williamson area nonprofits, was appointed to the WVFTC, and helped submit the water trail application for the Tug Fork.

Seeing what the CRG and other watershed organizations were doing to help clean up their rivers, FOTF became more involved in river restoration efforts. From there, the next step was to establish an official water trail. “It has been an abused river over the years,” Burchett says. “Thankfully the water is very good now, but we still have a long way to go to get the rest of the river cleaned up and we will continue to work on that. It’s a never-ending process.”

Over a span of five years, volunteers successfully recovered more than 13,300 tires from the river. Today, the Tug Fork supports a healthy smallmouth bass fishery, despite volunteers still removing tires from its waters. “We will continue our efforts to restore it to its former glory,” Burchett says.

Historic sites related to the legendary Hatfield-McCoy Feud line the riverbanks that users can access while floating, and the popular Hatfield-McCoy Trail System has bolstered economic development in Mingo County. Burchett, however, says the region’s growing tourism economy was missing something else for people to do while they visited. “We’re looking for the Tug Fork River to

Left: A canoeist enjoys a peaceful float beneath a sycamore grove along the Upper Cheat River Water Trail. Photo by Kent Mason / Friends of the Cheat. Right: The Tour de Coal, the largest flatwater kayak gathering in the country. Photo courtesy Coal River Group. Previous: A serene summer evening on the Tug Fork River. Photo by John Burchett.

be the second ride in our outdoor adventure amusement park,” he says. “We want people to come ride the trails and float the river. It adds another day or two to their stay.”

CHEATING THE SYSTEM

Volunteers are not only crucial to keeping the rivers and water trails clean, but also establishing them in the first place. The nearly 40-mile Upper Cheat River Water Trail (UCRWT) wouldn’t exist without the generosity of landowner cooperation, says Amanda Pitzer, executive director of the Friends of the Cheat (FOC).

The UCRWT was established 12 years ago, bolstering local support for FOC. Having seen how the CRWT had benefitted St. Albans, landowners approached FOC and encouraged others to support the trail, even when it involved offering some of their land for public access. “Imagine how generous someone is to take their little piece of river heaven and turn it into a parking lot,” Pitzer says.

With increased use on the water trail comes more eyes on the river, and Pitzer says they’ve seen less trash and litter on the Upper Cheat. Watchful volunteers are crucial at these sites throughout the season. In partnership with the fledgling Mountaineer Trail Network, volunteers will also install new signage and kiosks supplied with revised maps across the UCRWT’s nine river access points.

Pitzer says the Flood of 1985 resulted in the creation of natural

river access points that now serve as put-ins for the UCRWT. “In true [FOC] fashion, we took something that was largely a disaster, and were able to turn some of those impacted properties into assets,” she says. “That’s been really valuable, and the collaboration with the towns has been really great, too.”

Owen Mulkeen, FOC associate director, says the development of the water trail benefits tourism and locals alike. Additionally, partnering with the West Virginia Land Trust and West Virginia Rivers Coalition for events like the annual Meet the Cheat community paddles helps to get folks on the river while educating them about important issues.

“It’s a nice little ecosystem of outdoor recreation that feeds off tourism in Canaan Valley,” Mulkeen says. “As more people come to experience [the UCRWT] and we get more people interested in the Cheat, they’ll be more likely to protect it, enhance it, and be good stewards of it.”

The UCRWT is safe, family-friendly, and has a low barrier to entry for most folks. Thanks to groups like FOC and the Upper Cheat Water Trail Committee, those new to the river can learn how to paddle safely. Water trails are the new main streets, Pitzer says—accessible places for people of all ages and abilities to gather and make new friends. “It’s a beautiful thing,” she says. “I think every community should have a water trail.” w

Amanda Larch is copy editor of Highland Outdoors and looks forward to dipping her toes in some flatwater this summer.

Paddlers strike a pose in front of an impressive rock formation during the annual Meet the Cheat float trip. Photo by Kent Mason / Friends of the Cheat.

Words and photos by Victoria Weeks

Acrisp, clear afternoon in late September 2020 found me pedaling up the Blackwater Canyon from Hendricks to Douglas, West Virginia. I was not happy. My back hurt, my knees ached, and my feet were numb.

The nature of the rail-trail meant I was climbing a solid 3.5 percent grade without a single descent. Usually an attainable 21-mile round trip for tourists or new riders, but I was 63 miles into a 103-mile ride and wanted to finish by sunset. There was no time for breaks to take in the views or rest my back. I nicknamed that section the “Meat Grinder” that day. I could easily have asked myself, “Why am I doing this?” But I didn’t. I knew exactly why.

At some point in our lives, we all face moments of aimlessness and lack zest for life. A significant life change often triggers these moments, perhaps the children leaving home or losing a career-de-

fining job. Or, we may find ourselves stuck in a well-worn, comfortable rut that we know in our hearts will lead nowhere.

My life took a traumatic turn in January 2020 when I lost my husband of 13 years, Eric, to cancer. In the final years leading up to his passing, my focus was primarily on his care, an endurance feat of its own. Suddenly, without such a defined purpose—or my best friend—I was lost. I found comfort in the rut of our well-worn couch, surrounded by all his stuff.

Further trapped by the pandemic shutdowns, I found a way to pass the time like many others: I watched a lot of YouTube. I gravitated toward adventure stories, and I started to dream about solo bikepacking trips for the simplicity of the lifestyle. But once I factored in the loneliness, I lost interest. I had plenty of that already.

The Spark

Watching stories of others experiencing life, I realized, on some subconscious level, that I was watching magic unfold. Many of these athletes or adventurers had set lofty goals and were either achieving them or making every effort to do so.

I inherently understood the purpose of goal-setting. Goals help us pick a direction and set us on a specific path. A particular target provides more focus and direction than a generic desire. Preparing for a genuinely challenging goal fosters perseverance, and achieving it promotes self-confidence and growth. A goal race was my ticket, even though I didn’t know it then.

Somewhere between van life and bikepacking videos, I ran into videos about the Leadville Trail 100 Mountain Bike Race (LT100) in Leadville, Colorado. The LT100 boasts 105 miles of high-altitude, off-road racing, averaging 115 feet-per-mile of climbing. Topping out at an elevation of 12,516 feet, I knew this race had the power to inspire me to action.

Eric and I had watched the 2010 film “Race Across the Sky” a few years earlier. But now, as I took in the race’s epic climbs, gnarly descents, and staggering altitude, I started to feel something… something besides sadness. There was a spark. It didn’t take long to ignite a flicker of hope, something I hadn’t felt in months. I could do that race. I didn’t know how, but I knew I should at least try.

My First 100 Miles

I had never ridden anything near 100 miles off-road or on. I had prepared for a marathon in the past and understood the basics of endurance training. After what I’d just been through with my husband, I had solid faith in my capacity to adapt and endure. I didn’t want to waste that strength.

And so it began. I decided to ride 100 miles on Eric’s birthday weekend in September 2020. I remember announcing this to two of my riding buddies one spring afternoon as we set up for a ride in Blackwater Falls State Park: “I’m gonna ride 100 miles this year!” Neither one told me I was crazy. They supported me by joining me on my long-distance gravel rides, as did many others, and coming up with incredible routes around West Virginia.

start and finish at my home just outside Davis. At 6 a.m., joined by four ladies, I rolled out onto Canaan Loop Road in the dark. Descending Forest Road 244 in the chill morning air was better than a cup of coffee. I was awake! After a short time on Route 72, we turned onto River Road along the Dry Fork of the Cheat. My plan involved being there for sunrise, and here we were. Settling in at a steady pace alongside the river on which Eric and I had run so many kayaking trips, I felt an overwhelming sense of peace.

Returning along the river and eventually joining the Allegheny Highlands Trail, we reached the first planned stop about 30 miles in. My friends Ed and Stro were running SAG (short for support and gear), so we topped off our water and snacks and checked over the bikes. Some riders left while new ones joined. My friend Charlie stayed on, and little did I know that she planned to ride the whole route. We headed through Parsons and onto Government Road, a lovely stretch of gravel along the Shavers Fork of the Cheat. I felt strong as we pedaled out and back along the river. Retracing our steps through Parsons, we headed toward the start of the Blackwater Canyon Trail and the Meat Grinder.

Peaks and Valleys

Any long-distance, human-powered trip traverses many peaks and valleys, regardless of the terrain’s elevation profile. Sometimes, the mind, body, and spirit are in sync, and the effort comes easily. But this ride up the Meat Grinder did not! Nothing was in sync. Thanks to a poor bike fit, my body was firing off all sorts of pain notifications. My mind started to wander into boredom, and my spirit was sinking like a rock. This was not a difficult climb, but I was more than halfway through the day, and the relentless grade was taking its toll. How could I do another 40 miles if I felt like this now? The climbing had only just begun.

Climbing—that’s what I was here for. If I was going to race the LT100, I had better get used to it. Leadville’s infamous Columbine climb starts at mile 45 and climbs 3,150 feet over seven miles—an average grade of almost nine percent. The high point and

Above: A training ride through Canaan Valley, looking positively tame compared to the ragged edges of Colorado’s Sawatch Range, home to the LT100.

Right: Eric and I soaked in the sun and the dust on our many trips to Moab, Utah.

In the early days, my training consisted mainly of tacking on mileage. Almost every weekend, my friends would devise a gravel route that upped the ante from the previous weekend’s ride. I learned so much on these rides, including what and what not to eat, how too much water made for too many stops, and how a new chamois could make all the difference in the world.

As September approached, I spent hours on RideWithGPS devising a local 100-mile route. I wanted to

turnaround of the race is well above treeline at 12,516 feet elevation. This stretch of rail-trail I was riding wasn’t even a quarter as challenging. Knowing that didn’t make the climb seem any easier, or the pain dissipate, but it buoyed my spirit just enough. I was doing this for a specific purpose. This 100-mile ride may have been the culmination of my training for 2020, but it was only the beginning of my training for Leadville.

We eventually passed the plunging roar of Douglas Falls on the North Fork of the Blackwater and topped out onto a gravel road heading toward Thomas. I yearned for a coffee and pastry from Tip Top, but there was no time. My support crew was waiting with the next round of supplies at mile 76: Blackwater Bikes in Davis. I was hungry and tired by this point and spent too much time wandering around, snacking on pretzels, and sitting down. I look back now and realize I was highly under-fueled during the ride. I hadn’t yet heard the adage: “Leadville is an eating contest disguised as a bike race.” Most long-distance events are. I simply didn’t know how much I should’ve been eating.

The Home Stretch

It was 3:30 p.m., and I had another 30 miles to reach my home atop Canaan Mountain. I was exhausted. Endurance efforts of this type are typically considered a solo endeavor. But our group that ascended the Blackwater Canyon had grown. Knowing my friends were up ahead gave me much-needed mental and emotional sustenance.

Above: Canaan Loop Road was not only a part of my first 100-mile route, but it has become my backyard training camp for

We climbed up A-Frame Road on the eastern rim of Canaan Valley and took a break at the platform with a spectacular overlook of the Canaan Valley National Wildlife Refuge. It dawned on me that I had to cross the sprawling valley

and climb up to the top of the far ridge. I didn’t know if I had it in me. My friend Chrissy, a yoga teacher, encouraged me to stretch my back and legs using the railing for “legs up the wall” pose. As I lay on the deck, looking at the clouds overhead, I could feel all the used-up and tired energy draining from my lower body and getting restored with freshly oxygenated blood. The feeling came back to my feet.

We caught golden hour as we traversed Canaan Valley on the Middle Valley Trail. We joined up with the Blackwater View Trail, a few miles of freshly built singletrack by Appalachian Dirt. As we popped out onto the Beall Tract parking lot, I realized my rear tire was extremely low. I should’ve stopped to add air, but we still had four miles and a steep climb to go. I knew if I got off the bike, I wouldn’t get back on.

Shortly after, we crossed the coveted 100-mile mark. My friend Dan whooped, hollered, and congratulated me: “100 miles, you did it!” He was right, but I was still three miles from home, so I couldn’t relax just yet. I did, at least, crack a smile.

Pulling into my driveway, which was packed with friends already celebrating my arrival by the bonfire, was surreal. My body was trashed. I was so tired that I couldn’t find the energy to be excited. But as I sat down, legs still buzzing, I took it all in. I did it. I rode 100 miles—103.4 miles, to be exact. I proved I could spend all day on a bike. I had much to learn, but Leadville suddenly became possible.

I soon realized this mission had grown larger than me and my two wheels. I was not the only one heavily invested in my success— my friends, family, and crew were, too. As my first attempt at the LT100 approached in 2023, I began sharing my journey online, and the circle expanded to include those who heard my story and were inspired.

Truthfully, I’m not some genetically gifted rider, nor do I have any particular background that makes this mission easy for me. I’m also no spring chicken. But I’ve learned that a challenging goal met with dedication, consistency, and a good training plan can transform us into something much more powerful than we can imagine. My magic number was 100 miles. What’s yours? w

Victoria Weeks is a media professional who lives in Davis, WV. She is the author of The Victory Lap, a blog that chronicles her endurance training and racing—follow her journey at www.victoriaweeks.com.

My pup and travel buddy, Hazel, follows my wheel with gusto on mountain bike rides through the forests surrounding Davis, West Virginia.

Leadville.

The Enduro Race will be held on National Forest System lands.

BY GENE KISTLER

CAPTAIN’S LOG: 6 A.M., FRIDAY, MAY 17. I GET UP SLOWLY AS MY BONES AND MUSCLES COMPLAIN LOUDLY UNTIL STRONG, HOT COFFEE CONVINCES THEM THAT EVERYTHING IS OK.

At 7:30 a.m., I drive across US Route 19 to the Burnwood Campground on the rim of the New River Gorge. These are hallowed grounds where many glorious times have been enjoyed over the years by rock climbers from around the world. I park and wander into a slow-moving crowd of climbers-turned-volunteers, some from as far away as Toronto, who are gathered here today to get dirty and sweaty. They’re still waking up; I hear the cross-chatter of quiet conversations as they sit drinking coffee while assembling simple breakfasts and lunches. It’s day seven of (Not) Work Week (NWW), our annual eight-day volunteer shindig where we do a whole lot of hard work that isn’t really work after all… or is it?

As the caffeine kicks in, some folks start examining the free items on the registration table and fill out tickets for the evening raffle. Who doesn’t love a raffle? Today’s prizes are a 70-meter rope and a set of quickdraws—tools of the trade for climbing the New River Gorge’s legendary cliffs. Above the table hangs a banner with the letters NRAC, short for New River Alliance of Climbers—our local advocacy group responsible for making climbing safe and sustainable in the gorge. Underneath the logo is the phrase “Be Informed—Get Involved—Stay Connected.” I feel so connected here today. I look around as more folks rise. I recognize almost every sleepy face, some returning every year to (not) work with us. The coffee keeps flowing; the conversations follow suit, growing louder and louder. Laughter starts popping through the chatter. Another day is winding up and the familiar, clear energy of NWW is coalescing once again.

At the center of this frenetic swirl is Brittany Chaber, my organizational partner for this annual “work” party, the calm eye in the middle of the storm. Every morning, Brittany arrives early at Burnwood and sets the positive vibe for the day. She is ultra-organized. She lays out the breakfast and lunch fixins and staffs the registration table, greeting sleepy climbers and registering new arrivals.

Left: The man, the myth, the legend, the author: Gene Kistler. Photo by Jay Young. Right top: Volunteers use a “come along” winch to move massive rocks. Photo by Karen Lane. Right bottom: (Not) workers slide a 400-lb paver stone down a slide. Photo by Jay Young. Previous: Volunteers form a rock brigade to shore up rock climbing access on Summersville Lake. Photo by Jay Young.

There are rolled up T-shirts for each volunteer, the fruits of her labor that starts in the winter.

Over the years, Brittany has developed a proven formula: she raises around $4,000 every year from eastern climbing gyms to pay for NWW shirts and feed 200 volunteers for eight days. She works with outdoor brands to collect excellent raffle prizes. She sets up the online registration, sends out the recruitment fliers to schools and gyms, and writes the press releases—all of this as a volunteer. “In 2015, I attended the first NWW. Nine years later, I’m still trying to figure out what makes it so special,” Chaber says. “I love welcoming new people and seeing the volunteers who continue to return year after year. We’re so lucky to have the opportunity to give back in such a way that makes us feel that we belong.”

It’s now 8:30 a.m. and the morning mist rising out of the ancient gorge has finally burned off. A few morning announcements are made and now it’s time to go to (not) work. However, this morning is different—everyone is getting geared up and going rock climbing, because the work is done!

We had an ambitious scope of work slated for our eight-day NWW. But with around 30 volunteers a day, we completed the massive list of trail work and site improvements in just six days. This year’s accomplishments resulted in transformational improvements at the Whippoorwill and Summersville crags at Summersville Lake, including the installation of split rail fencing to protect the hillside from further erosion, creation of a revegetation plan, construction of stairs, clearing of brush, and improvements to existing trail tread. We also did some brush clearing and major rock work on the North Bridge Trail. Looking back on our accomplishments, we’re all a bit mystified. I hear the familiar clinking of carabiners accompany the chatter. The excitement is palpable. It feels like summer camp. As I watch folks gather their kits and depart Burnwood for the crags, I stop and reflect on the decades. How did I get here?

We moved to Fayetteville in 1991. Back then, Fayetteville wasn’t the vibrant town it is today. Only a few of us climbers had made the tough decision to uproot and move here. We had to figure out how to make it all work. But as we developed more climbing routes, a steadily growing number of climbers from the surrounding states and beyond continued showing up every weekend. By the late 90s, folks were climbing thousands of routes on the towering cliffs rimming the New, Meadow, and Gauley river gorges, and hanging above the turquoise waters of Summersville Lake.

Top: Craig Reger, all smiles and hardly working. Photo by Karen Lane. Bottom left: Volunteers use rock bars to put boulders in place to create new trail tread.

Photo by Karen Lane. Bottom right: Volunteers loading timbers on a USACE boat to be shipped for shore work on Summersville Lake. Photo by Jay Young.

All of our world-class climbing takes place on public lands. The three river gorges are managed by the National Park System (NPS), and every national park in the country that had rock climbing at that time was tasked with developing and enforcing a climbing management plan. Summersville Lake is owned and operated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), which manages the dam and lake that just happens to be surrounded by awesome cliffs. At the same time, the Access Fund, a national climbing advocacy nonprofit, was encouraging climbing communities across the country to organize and develop relationships with land managers. In 1997, we gathered to form NRAC as local climbing advocacy took root around the country. We approached the NPS and USACE as one and hoped that, in time, we could all work together.

Before the days of NRAC, there was Rick “Rico” Thompson. Rico planted the volunteer seed. He was part of a Pittsburgh posse of funhogs that explored and climbed all over this place. In the 80s, the bases of the cliffs lining the New River Gorge were littered with a century’s worth of trash piled below any place folks had cliff-top access. Climbers hiked by it routinely to the point where seeing it became normal. But Rico saw things differently and began organizing climber cleanups by word of mouth (this was long before the days of email). For the first time, different groups of climbers started coalescing to haul tons of garbage from the depths. That was the beginning of the rock-solid climbing community that we have today, built on discovering how much fun it was to hang out, shoot the breeze, make this place better, get a (not) work out, and entertain the local TV news reporters. That seed Rico planted in the eighties still grows and bears fruit some 30 years later.

But by the time we established NRAC, everyone was tired of hauling garbage. Luckily, most of the garbage was gone.

Our broader goal was to make climbing sustainable and that meant mitigating climbers’ impacts. A climbing trail plan was needed. We won a grant from the Access Fund that brought in trail building expert Jim Angel. He struck the trail work spark that still burns today.

Trail building and maintenance was way more fun than hauling garbage. We began to organize trail days, which expanded into trail weekends. Over the next fifteen years, we established proper trails in the New River Gorge and Summersville Lake. We worked hand-in-hand with the NPS and USACE. The community volunteer framework proved resilient and the grassroots grew. From 2003 to 2013, we held an annual, wildly successful climbing celebration called the New River Rendezvous. We continued to pound the volunteer drum.

But such work is never finished. We needed something new to grow our capacity, to spend more time together, to build on our sense of accomplishment. I learned about the Yosemite Facelift, which is two whole weeks of volunteer stewardship deep in the crucible of American rock climbing. We realized that the weekend paradigm no longer satisfied the urge—we wanted more. Let’s do a week, we said. No, make it eight days! Let’s make sure that we take our time, have fun, and not get hurt. We formulated the equation to serve as the foundation: work + fun = (not) work! Let’s raise money to feed everyone, provide free camping, and treat volunteers like celebrities. The workday would be from 9 to 3, then you go climbing, and then you end the day with dinner at Burnwood, a local restaurant, or someone’s house. The broader community response was huge. Businesses in and around Fayetteville loved it. The first NWW was held in 2015, and it’s been a resounding success ever since.

Looking back on a decade of NWW, we realized that this year was the ninth rendition (of course, there was no NWW held in 2020). And we’ve been wondering why do people keep coming back for more? I think the answer to that burning question is best addressed by third-year NWW alumna Ashlei Selden. “To sum it up, this kind of thing is what humans crave, even if they don’t know that it’s what they need,” she says. “It’s in our blood. It’s the gift our ancestors gave us—the gift of being able to find rhythm in problem-solving with kindred minds, working the land with our hands, feeling that sweet sun on our skin. The key ingredients to life are as old as time: community and connection to the ground you stand upon.”

Ultimately, we are all volunteers. That’s how we roll here at NRAC. Together, we’ve learned how communities grow, gain fiber, and get strong—much like a rope. We’ve had so much fun (not) working. We’ve formed unbreakable bonds over our collective admiration for this amazing place and the privilege to climb these gorges. w

Gene Kistler is a shaker, doer, and maker of subversive positive change who lives in Fayetteville on the rim of the New River Gorge. Karen Lane

By Dylan Jones

I’ve never been much of a history buff. Any time I pass a historical roadside marker or a friend sends a history podcast, I think I should really check that out, but never end up doing so. It’s not that I don’t find history interesting, or important for that matter, it’s just that life is short and there are other things I’d rather do. But on a recent trip to Harpers Ferry to hike West Virginia’s portion of the Appalachian National Scenic Trail (AT), I found myself at the confluence of several rich histories: the geologic tale of two mighty rivers, the calamitous story of our nation’s past, and the collective legacy of tens of thousands of AT hikers who’ve gathered in this famous town. Suddenly, I found myself reading those very markers I had long ignored.

I’ve lived in West Virginia for most of my life but had never been to Harpers Ferry despite knowing a good bit about it. I had seen photos of the classic view of town from an overlook high above the Potomac River. I knew that at just 247 feet above sea level, it’s the lowest point in the Mountain State. I knew the story of John Brown’s 1859 raid on the federal armory that was a major catalyst for the Civil War. I knew that the Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC), the nonprofit organization that oversees conservation of the entire AT, maintains its headquarters there.

But I had no idea just how big the Shenandoah and Potomac rivers are there, how steep the mountainsides are that plunge to their rocky banks. I had no idea that the historical center of Harp -

ers Ferry is a National Park, operated as such like a living history class with staffed exhibits and walking tours.

I also had no idea that the official path of the AT actually passes right through the heart of town, that every year thousands of hikers traverse the same cobbled streets on which Brown’s abolitionist rebellion sought to end slavery.

Running 2,190 miles from its southern terminus on Springer Mountain in Georgia to its northern terminus on Mount Katahdin in Maine, the AT is the world’s longest footpath. Interestingly, West Virginia only has about four miles of the AT fully within its borders (nearly 20 miles of the trail run along the WV-VA border, but they aren’t considered fully within either state), meaning that the Mountain State is home to just 0.1% of the trail. Despite having the smallest share of mileage out of the 14 states through which the

AT passes, Harpers Ferry is a major stop for thru-hikers— those who hike the entirety of the AT in a single go.

Considered the “psychological half-way point” of the AT (the actual halfway point sits atop South Mountain, in Pennsylvania’s Michaux State Forest), reaching Harpers Ferry is a milestone for those traveling north or south. “When I crossed into West Virginia, which I was very much looking forward to, I remember thinking Yes! Home, sweet home! ” says Alex Snyder, a Davis resident who thru-hiked the AT in 2009. “I was so psyched. I thought if I’ve gone this far, I can do it all. That was a big moment.”

After six months of “putting one foot in the front of the other,” Snyder serendipitously reached the summit of Mount Katahdin on his 23rd birthday. Soon after, Snyder decided he wanted to become an outdoor educator. “The AT was one of those moments where

my life was on a certain trajectory, and then everything pivoted. I could see right then that my life had been changed,” he says. He and his wife Libbey Holewski now run Appalachian Expeditions, an outdoor education camp based in Davis.

No AT thru-hike is complete without a visit to the ATC visitor center, a welcoming respite where hikers can check in, get their photos added to a registry—Snyder says one could dig up his mugshot in the archives—restock on supplies, and even sneak in some computer time. The ATC offers a common space to share in the type of camaraderie that can only be found among those who undertake this monumental effort.

Originally founded in 1925 as the Appalachian Trail Conference, the ATC was housed in Washington, DC, where it shared office space with the Potomac Appalachian Trail Club (PATC). The PATC is one of 31 AT clubs that are now managed by the ATC and are responsible for daily operations like trail and shelter maintenance. Following the 1968 passage of the National Trail System Act, the ATC moved its headquarters to Harpers Ferry in 1972. “The ATC figured there would be more interest in the Appalachian Trail and that they would need permanent staff to respond to the increase,” says David Tarasevich. A proud thru-hiker, Tarasevich now cheerfully assists hikers as the ATC visitor services representative in Harpers Ferry.

According to the ATC’s hiker registry, over 20,000 hikers have completed a thru-hike since record keeping began in 1936. Tarasevich says that around 3,000 people embark on a thru-hike every year; only about a quarter of them make it.

As with any outdoor community, there’s a lexicon of terms and abbreviations associated with the AT. The majority of thru-hikers head north (NoBo); more intrepid souls start in Maine and head south (SoBo). And not all AT alumni are thru-hikers—section-hikers complete the AT in chunks over multiple outings, while flip-floppers start at a given location, reach either terminus, than return to that location and head the other way. Given the coveted position of half-way point, Harpers Ferry is the most popular—and most logical—locus of origin for flip-floppers.

My wife Nikki and I decided it would be an entertaining endeavor to take our inaugural pilgrimage to Harpers Ferry and hike the entirety of West Virginia’s share of the AT. I hopped on the trustworthy internet and did my own research, which showed just 2.5 miles of the AT being within WV’s borders. Piece of cake! We’d be able to enjoy a slow morning and easily dispatch the mileage via a quick afternoon jaunt before swinging into the ATC visitor center. The plan was simple: we’d knock out the crossing over the Potomac into Maryland, then head back into Harpers Ferry and trend south until we hit the Virginia border, then retrace our steps back to Harpers Ferry, staying on the AT the entire time.

Nikki and I consider ourselves seasoned outdoorsfolk. We’ve done plenty of adventures that require a high level of preparation, route-finding ability, and technical skill. But today, we find ourselves quite underprepared. We only brought one backpack, which is loaded with my camera gear, and forgot to bring a water

bottle or food for the trail. In triage mode, we buy two 12-oz bottles of water and some granola bars from a coffee shop and figure we’d be good to go. It’s only a total of five miles, right?

Off we go, headed for Maryland. West Virginia ends as soon as you dip your toes in the Potomac—the state of Maryland owns the entirety of the Potomac River along the border. But we figure we aren’t truly in Maryland until we cross the Bollman Bridge, which was built in 1894 and still serves as an active crossing for the B&O Railroad, and set foot on terra firma in the Terrapin State.

We look up as an osprey spreads its wings and soars above the rocky promontory onto which Harpers Ferry is built. I imagine what this landscape must look like from a thousand feet in the air. How many pivotal moments have been observed by birds looking down on our ever-unfolding human dramas?

We cross back into town and start the climb up steep steps, passing a steepled cathedral under renovation. As soon as we get off the sidewalk and onto the dirt, I notice the first white trail blaze—the official marker of the AT. I immediately feel a flood of adrenaline upon realizing that I am walking on what is arguably the most famous footpath in the world. Knowing that tens of thousands of people altered their lives to have a shot at walking its length—and, like Snyder, undoubtedly had theirs altered by doing so—connects me to countless footsteps, regardless of how far we plan to walk today. It’s funny how a simple white paint stroke can stir the soul.

We’re happy to escape the heat of the sun and enter the “green tunnel”—the term endearingly (and sometimes not) used by thru-hikers to describe most of the AT experience. Don’t let the photographs of hikers in open balds in the Smokies or atop rocky peaks in New England fool you: the overwhelming bulk of the AT’s mileage crawls by under the thick canopy of Appalachian forest with nary a view in sight.

As we move through the green tunnel along the bench cut of a steep slope, we pass Jefferson Rock: an outcropping featuring a precariously balanced chunk of shale on which Thomas Jefferson stood during his inaugural 1783 visit to Harpers Ferry. In his 1785 essay “Notes on the State of Virginia,” he penned a classically verbose description of the landscape:

“The passage of the Patowmac through the Blue Ridge is perhaps one of the most stupendous scenes in Nature… On your right comes up the Shenandoah, having ranged along the foot of the mountain a hundred miles to seek a vent. On your left approaches the Patowmac in quest of a passage also. In the moment of their junction they rush together against the mountain, rend it asunder and pass off to the sea… This scene is worth a voyage across the Atlantic.”

What’s left of the loose shale pile where Jefferson once stood is now supported by several sandstone columns erected in the late 1850s, but the view is just as stunning. I wonder what Jefferson would think of the scene now that several railroad and vehicular bridges crisscross the confluence of these great mountain rivers as they make their way toward the nation’s capital.

Clockwise from left: A towering tulip poplar rises through the green tunnel of the Appalachian Trail. The Shenandoah River drops over a series of rocky ledges before its confluence with the Potomac at Harpers Ferry. A pair of thru-hikers saunter through Harpers Ferry National Historical Park—the psychological halfway point of the Appalachian Trail. Previous: Jefferson Rock, an impressive viewpoint from which Thomas Jefferson declared, “It is worth a voyage across the Atlantic.”

Bottom left: An eastern cottonwood sends its offspring into the blue

Right: The AT drops nearly 1,000 feet from Loudoun Heights down to Harpers Ferry, testing even the best thruhikers’ knees.

Jefferson Rock is one of the first vestiges of the historical park passed by northbound AT hikers before they descend the concrete steps into Harpers Ferry. After pondering a hypothetical Jefferson’s thoughts about the impacts of modern infrastructure on the natural scenery, I switch gears and ponder how many AT thru-hikers stop here to do the same. If I was 1,000 miles into a hike and ready for a hot meal, shower, and a bed, would I take the time to drop my backpack and consider the significance of this spot, or would I simply pass by yet another historical marker and continue the relentless shuffle of my feet in pursuit of caloric happiness?

A steep drop down the hillside leads us to the John Hancock Hall Memorial Bridge, named after the industrialist who invented the concept of interchangeable parts in manufacturing. Here, AT hikers hop onto a sidewalk and cross the Shenandoah River. I stop to snap a photo while traffic whizzes by at speeds of 50 miles per hour. The view is breathtaking, but the vibe isn’t exactly pleasant—this would

have to be quite a shock after spending who knows how many days in the woods.

Onward. Once across the Shenandoah, a set of steps leads us under the bridge deck, and then it’s back into the green tunnel, but this time on quite an incline. Here, the AT ascends nearly 800 feet in just a mile, producing quite a burn for all but the most fit hikers. But as the sound of rushing traffic drops away, the magic of the Appalachian forest returns. Thick hummocks of moss grow on seeps emanating from clefts in the mountainside. Gnarled roots double as steps, offering a variety of options for those going up or down the sharp switchbacks. A grove of giant tulip poplars dwarfs any other hikers you might pass on the trail. We pass an aging section hiker who tells me that he completed his inaugural thru-hike “many moons ago.”

Up and up we go, climbing nearly 1,000 feet above the Shenandoah. Atop the ridgeline, the AT parallels the WV-VA border, getting torturously close for

Top left: David Tarasevich (left) and Melanie Spencer (right) at the ATC headquaters in Harpers Ferry.

abyss.

what feels like at least a mile. I swear we should be close, at least according to my GPS app. We’re over four miles into our hike and almost out of water—turns out the internet lied about the length of the AT in West Virginia. We stop for a sad lunch of granola bars and nothing else. Seated on a damp rock, soaked in sweat, and craving some salt, we ask ourselves: how the hell did we mess this up?

We expect there to be a sign denoting the state border crossing, but I see nothing down the trail. I stop and question if we should start heading back. But Nikki runs ahead, eyes simultaneously looking down at her GPS app and the trail as her feet dance across the rocky path. “Welp, this is it,” she shouts from a hundred yards ahead. The crossing into Virginia is just a nondescript spot in the green tunnel. The only thing you could consider a landmark is a large chestnut oak with dappled sunlight highlighting its deeply furrowed bark. Although a bit anticlimactic, we had reached our goal. Now it’s time to head back, and with haste, as we have but a few ounces of water left for the four-mile return trip. We discuss the arbitrary nature of state boundaries as we descend the mountainside, happy we don’t have heavy backpacks adding additional stress to our tired knees.

As we cross back over the Shenandoah, we stop again to take it all in. Looking straight down, we notice a Merganser parent guiding three adorable ducklings down the chutes and riffles created by the seemingly endless bedrock ledges. We sound like sportsball commentators as we analyze the ducklings’ surprising ability to ride the currents, catch micro-eddies, and regroup before the next frothy drop in the river. The Shenandoah is incredibly wide—orders of magnitude beyond the narrow mountain streams where we live high up in Tucker County. I consider how dangerous it would have been to ford the river on horseback during the Civil War, or how screwed you’d be if you tried to cross it as a backpacker.

West Virginia Highlands Conservancy in protecting the crown jewel of West Virginia by joining the Dolly Sods Wilderness Stewards.

Once back on shore, we see the tell-all white blaze directing us back up the steep hillside and into the green tunnel. Stained with salt from sweat, out of water, and with my dogs barking, I notice another sign that directs traffic and tourists downhill to a street that runs the length of the old C&O Canal and into Harpers Ferry. Shaded by giant eastern cottonwoods and flat, it’s an easy decision, despite feeling like we’re bailing a bit on our original plan to walk the AT the entire time.

As we stroll in the shade, a cool breeze renders my sweat useful for once, and what looks like snow swirls around us in the 85-degree air. The flowering cottonwoods are covered in catkins, releasing their wind-pollinated seeds in huge puffs that look like a sea of stars against the deep, blue sky.

My feet are happy, but my mind swirls like a cloud of cottonwood seeds back to Jefferson Rock. I had been looking forward to attaining the view on the return trip after getting some miles under the belt, perhaps better able to ponder what a thru-hiker might experience when reaching this impressive stance above the Shenandoah. I suppose I won’t have an answer to that question until we go and thru-hike the Appalachian Trail. w

Dylan Jones is publisher of Highland Outdoors and is hereby making a vow to maybe, someday, walk some, or all, if not most, of the AT.

By Nikki Forrester

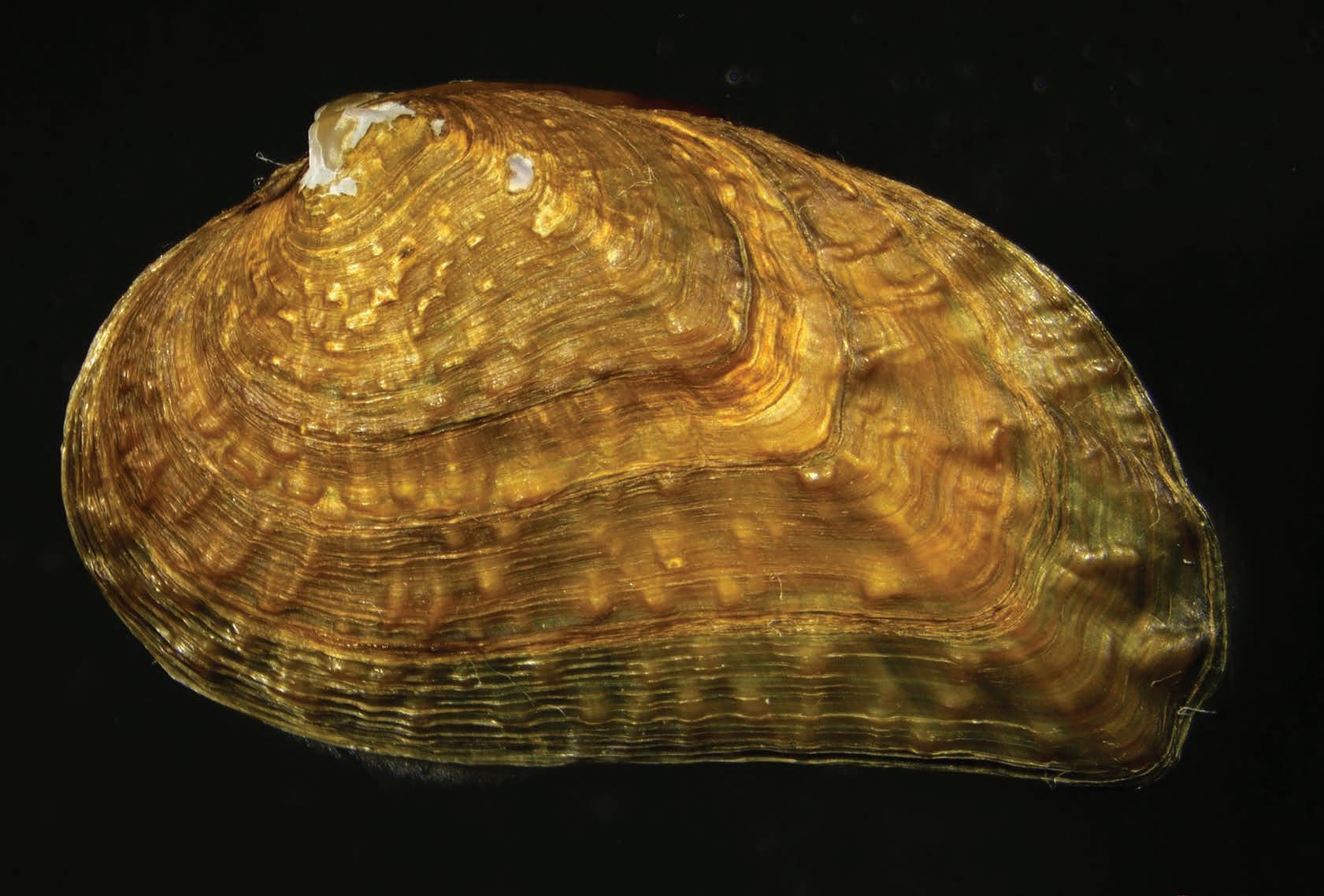

The first thing you notice when you walk into the White Sulphur Springs National Fish Hatchery is the smell. There’s a salty, manky aroma that makes you feel as though you’re standing on the marshy banks of a bayou. Which is odd, because the fish hatchery doesn’t specialize in saltwater species. Instead, it’s home to hundreds of thousands of freshwater mussels.

In some ways, the smell harkens back to the time when freshwater mussels first came to be. Scientists hypothesize that roughly 245 million years ago, these eyeless, brainless creatures transitioned from marine environments to the freshwater rivers and streams where they can be found today. But making the leap from the ocean to the river presented some unique challenges, namely the unidirectional flow of water downstream. “They had to evolve a relationship with another animal to be able to get their babies to at least stay where they are, if not go upstream, or they would never be able to get a toehold in the developing freshwater world,” says Gerry Dinkins, curator of the malacology collection at the University of Tennessee’s McClung Museum. Malacology is the study of mollusks, a group of animals that includes mussels, clams, snails, slugs, and octopods.

Today, almost all freshwater mussel species rely on fish to disperse their progeny upriver. Female mussels have evolved a stunning array of tactics to increase the odds of their larvae, or glochidia, attaching to a fish. “In Tennessee, there are 140 species and they do it in 140 different ways,” Dinkins says. Some species release their glochidia directly into the water, others cast theirs in broad, gooey nets, and a few package theirs into tempting lures that resemble worms, insects, or small fish. The lures often have sheer membranes, lateral lines, fake fins, and eye spots to mimic fish that occur in the same stream. Mantle lures are closely attached to the mussel, whereas super-conglutinates are fed out into the water on a 6- to 8-foot-long string that the female mussel wiggles around like a lure. “She’s basically fishing for a host,” says Dinkins.

Once a fish bites onto the lure, the glochidia explode inside the fish’s mouth and clamp down their two shell halves to attach to the fish’s gills. Some glochidia even have small teeth or hooks to ensure they stick to the fish as it moves upstream. The glochidia, which don’t harm the fish, develop for several days to several months before dropping off the fish and establishing themselves in a new habitat. “They’re using the fish as a taxi service,” says Kevin Eliason, a wildlife biologist at the West Virginia Division of Natural Resources (DNR). “Wherever they land is where they’ll live.”

STUCK IN THE MUCK

North America is home to the greatest diversity of freshwater mussels in the world—roughly 310 of the 900 known freshwater mussel species can be found here. They differ in just about every trait imaginable. They can be as small as your pinky fingernail or as large as your head. Their lifespans can range from just two years to 150 years or more. Their shells can be smooth or bumpy, flat or inflated, dull or iridescent. And the names can tickle you pink (one of the many stunning colors inside freshwater mussel shells). In West Virginia alone, there’s the little spectaclecase, mapleleaf, elephantear, sheepnose, and purple wartyback.

But these days, it’s difficult for freshwater mussels to find suitable habitats. Over the past century, overharvesting, pollution, damming, and other environmental impacts have led to drastic declines in once-abundant freshwater mussel populations. According to the Center for Biological Diversity, freshwater mussels are the most endangered group of organ-

isms in the United States—30 freshwater mussel species have gone extinct, and 70% of the existing species are considered vulnerable, threatened, or endangered.

Freshwater mussels have been an important part of human culture for at least 10,000 years. Native Americans used them for food, tools, and ornaments. But the first major threat to freshwater mussels began in the early 1890s, when John Boepple, a German button maker, stumbled upon a bed of freshwater mussels in an Illinois stream. Button factories popped up along the Mississippi and Ohio rivers, and workers gathered millions of mussels and punched holes in their shells to create buttons. According to the Freshwater Mollusk Conservation Society, production peaked in 1916, when 40 million buttons were produced for consumers in America and Europe in a single year. The industry ended in the 1940s, but by that point, many of the mussel beds were completely depleted and forever changed.

Today, the major threats to freshwater mussels are logging, pollution, sedimentation, dams, and invasive species. One of the few, if only, traits all freshwater mussel species share is being filter-feeding bivalves that burrow into the bottoms of clean, flowing streams and rivers. Rarely do they move more than a few meters throughout their lives. “For an animal that creates a really hard rock shell to protect themselves, they’re fragile. They can’t avoid disturbances for long periods of time,” says Dinkins.

When dams are constructed, sediment builds up in the clean substrates that mussels prefer and restricts the movement of their host fish, preventing the mussels from reproducing. “That’s one of the big issues we’re having now,” says Eliason. “They’re functionally extinct even though the mussels are still there.”

LENDING NATURE A HAND

Hence the drive to propagate thousands of freshwater mussels at the White Sulphur Springs National Fish Hatchery. The hatchery currently works with nine species of freshwater mussels, including two endangered freshwater mussel species—the clubshell and northern riffleshell. Their goal is to not just preserve the diversity of freshwater mussels in the region, but to boost population sizes and reintroduce species that have gone locally extinct.

Previous: A fat mucket mussel, one of the nine species being propagated at the White Sulphur Springs National Fish Hatchery. Photo by John Moore / Andrew Phipps USFWS.

Right: A pocketbook mussel displaying a lure that looks just like a fish. Photo by John Moore / Andrew Phipps, USFWS.

On the day I visited, I had a chance to witness the earliest stages of freshwater mussel production. The process begins in the infestation room, where biologists bring pregnant freshwater mussels into the lab and extract the glochidia. “We get hundreds of thousands of little larvae or more,” says Andrew Phipps, a mussel biologist at White Sulphur Springs National Fish Hatchery. Then Phipps introduces the glochidia to host fish in five-gallon buckets. He gently grabbed a fish from one of the buckets and revealed the tiniest specks of mussel glochidia in its gills. “The reason we don’t do it in a natural way is because we want to maximize production. There’s a lot of waste in the river,” Phipps describes.

After the glochidia fall off the fish, Phipps moves them to water troughs filled with food. Then, when the juvenile mussels grow large enough, they are tagged with a unique number and moved outside into floating baskets lined with sand. The day I visited, there were roughly 7,000 pistolgrip mussels in an array of baskets, burrowing into the sand and feeding on algae, phytoplankton, and suspended particles in the water. The pond was dotted with old Christmas trees (to create minnow habitat and stabilize the pH) and surrounded by a tall fence to deter otters, raccoons, and other animals eager to feed on the young mussels. By late summer, the pistolgrip mussels will be released into an Ohio River drainage in Pennsylvania. “If we can make it to August with all of them, it’ll be the biggest release of that species that’s ever been done,” says Phipps.

INTO THE DEEP

After freshwater mussels are released into the wild, scientists continually monitor them, as well as the existing mussel populations, to keep track of survival and reproduction. West Virginia is currently home to 65 freshwater mussel species, the vast majority of which occur in the Ohio River Basin that drains from the western slope of the Appalachian Mountains. Ten of these species are currently

Left: A row of floating baskets in a pond at the White Sulphur Springs National Fish Hatchery. Each basket contains about 200 pistolgrip mussels. Next, clockwise from top left: Andrew Phipps pulls a host fish out of a five-gallon bucket; white specks of fat mucket mussel offspring were visible on its gills. A handful of young pistolgrip mussels. An array of tanks, each containing a different species of host fish, including sculpins, darters, and bass. Once the juvenile mussels grow large enough, they each get tagged with a unique number. A petri dish filled with juvenile mussels; researchers keep tabs on the number of mussels and inspect their guts to determine what the they like to eat.

All photos by Dylan Jones.

listed as endangered, and another six have been extirpated, meaning they’ve gone extinct within the state’s borders.

“We have 35 long-term monitoring sites across the state that are surveyed every five to seven years so we can keep track of how the community is shifting,” says Eliason. But monitoring mussels in the wild is no easy feat. As filter-feeding bivalves, freshwater mussels take in water and expel excrement through two apertures. These apertures are often the only parts of mussels visible in the stream; the rest of their shells are concealed beneath the substrate.

But perhaps the biggest challenge with mussel surveys is the lack of visibility. “Most of the time you can’t see anything,” says Nicole Sadecky, a native of Ravenswood, West Virginia, who is now a scientist at the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Before joining the EPA, Sadecky spent seven years monitoring mussels for the WV DNR in the Kanawha, Ohio, Monongahela, and Elk rivers, as well as all their major tributaries.

Although divers have lights, they rarely work, she says. “It’s like when you’re driving in a snowstorm. The light just reflects right back in your face.” Over the years, Sadecky has navigated numerous unexpected encounters on these mussel missions, including getting caught in several large trees underwater. “I remember one time diving around Blennerhasset Island when a passenger ferry and a barge went by me at the same time. The current was so swift that I had to use screwdrivers to dig into the substrate so I wouldn’t get swept away,” she recalls. “But that’s what I loved most about doing surveys. Anytime you jumped off the boat, you had no idea what would happen next.”

Because surveyors can rarely see underwater, they have to feel their way along river beds to find freshwater mussels, which, unlike rocks, tend to dig into the substrate when they’re touched. The divers carefully remove the mussels and bring them to the

surface to identify the species and collect measurements. Then they return the mussels to the water, making sure to insert them properly into the river bed.

Freshwater mussel density and species diversity can vary drastically across sites and streams. Sadecky’s favorite place to dive was Kanawha Falls. “I just feel like everywhere you look, there are mussels,” she says. Dinkins, who has also spent an immense amount of time diving in West Virginia’s waters, has a particular fondness for the Elk. “It’s hard to find that abundance and diversity of mussels in many places anymore,” he says. “Certain reaches of the Elk seem to tell me that’s how all our rivers used to look.”

And thanks to studies conducted by malacologist Arnold Ortmann in the early 1900s, scientists know which freshwater mussel species historically did and did not occur in West Virginia. These studies not only provide researchers with valuable information on population trends, but also help guide their restoration efforts.

Over the past decade, scientists have come together to reintroduce several freshwater mussel species that were extirpated from the state. From 2012 to 2014, a bounty of northern riffleshell mussels were released into the Elk, Kanawha, and Ohio rivers. The rayed bean mussel was reintroduced into the Elk River in 2012, and the purple catspaw mussel was reintroduced into the Ohio River in 2017. Continuous monitoring of these populations revealed that the mussels are indeed surviving, but scientists are still hoping to observe natural reproduction. “The true measure of success would be to have them become self-sufficient and increase their numbers naturally,” says Eliason.

Arguably the biggest focus of the WV DNR’s freshwater mussel restoration efforts has been Dunkard Creek, a tributary of the Monongahela River that flows through the northern part of the state. In September 2009, Dunkard Creek suffered from a toxic

A pile of fat mucket mussels are ready to be reintroduced to wild waters. Photo by John Moore / Andrew Phipps USFWS.

algal bloom resulting from high water salinity, most likely due to a mine discharge site on the creek. “100 percent mortality of freshwater mussels occurred in the stream, losing the last significant mussel population in the entire Monongahela Watershed,” wrote Janet Clayton, a retired WV DNR malacologist, in “The Freshwater Mussels of West Virginia.”

Since 2012, researchers have undertaken massive efforts to restore freshwater mussels in Dunkard Creek. To date, they’ve reintroduced 17 species, including the pistolgrip, fat mucket, Wabash pigtoe, paper pondshell, and pink heelsplitter. “In total, more than 10,000 mussels have been reintroduced into Dunkard Creek. While reproduction has been limited, we have begun to see natively reproduced animals for the first time in the past two years, which is really great to see,” says Eliason.

CAN YA EAT ‘EM?

Merely a century ago, billions of freshwater mussels coated the bottoms of the Mississippi and Ohio river watersheds, quietly yet powerfully shaping our aquatic ecosystems. Mussels stabilize substrate and serve as a food source for river otters, muskrats, raccoons, and other animals. They also play a key role in cleaning our waters by removing pollutants and recycling nutrients. A single mussel can filter up to 15 gallons of water every single day, an astonishing ability that has earned them the nickname “the liver of the river.”

While walking around the fish hatchery, I asked Phipps what he wishes people knew about freshwater mussels. “I always wanted to get a T-shirt that says, ‘Can ya eat ‘em?’” That’s the number one question a mussel biologist gets asked,” he says. (I guess technically you can, but given their long lifespans and supreme ability to accumulate pollutants, you probably wouldn’t want to.) But what he and the other people I talked to for this story want most is for people to just know they exist.

I think part of our nature is to view other animals through a human lens. We find value in knowing that other animals give us food, fresh air, or clean water. We are drawn to familiar features like large eyes, fluffy fur, and round faces. And that sense of connection has been pivotal for garnering public support to save endangered species like pandas, polar bears, and elephants. But I also like to think it’s part of our nature as humans to have an insatiable curiosity and a limitless capacity to learn about creatures that aren’t like us at all. We’ve climbed to the tops of mountains, traversed expansive deserts, and explored the depths of the ocean to discover organisms that have traits we could never in our wildest dreams imagine.

On the surface, freshwater mussels seem about as different from humans as they could possibly be. They don’t have eyes or legs or brains. They don’t move and they’re not cuddly. But the more I learn about them, the more I feel a sense of awe and appreciation for their unique way of being. While I’ll likely never see a healthy freshwater mussel in the wild, I find comfort in knowing that they’re there—these amazing aliens that live just beneath the surface of our West Virginia waters. w

Nikki Forrester is co-publisher of Highland Outdoors. She developed a soft spot for hard-shelled bivalves while writing this story. To all my fellow mollusk lovers, can I get a shell yeah!

Professional Engineers, Hydrologists & Geologists

Restoring & Protecting West Virginia’s Water for Future Generations Est. 2010

greenrivers net 304-704-4283