8 minute read

This is Indian Land: Hot Springs National Park

B Y J E S S I C A M E H T A

The smallest National Park has a rich indigenous history. At "just" 5,550 acres, Hot Springs National Park could fit inside the uncontested largest national park, Wrangell-St. Elias National Park, almost 2,400 times over. Located in the county seat of Garland, Arkansas, and tucked next to the town of Hot Springs, the region first piqued the interest of non-Natives when it was declared the Hot Springs Reservation by a U.S. act of Congress on April 20, 1832. It was well before the idea of national parks existed, and the first time in the post-colonial county, the land was set aside expressly for preservation and recreation. Shortly after the congressional act, Hot Springs began to be developed as a "spa town" and became incorporated in 1851.

Advertisement

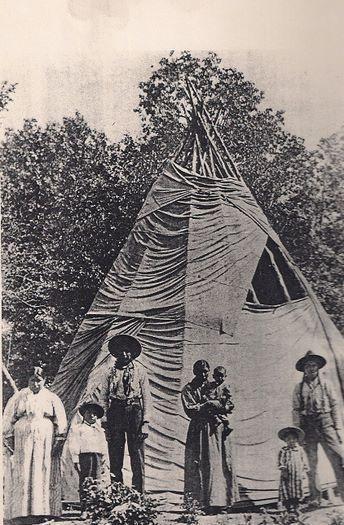

However, the seemingly idyllic embrace of the unique area has unsurprisingly played a long and critical role in the cultural, medicinal, spiritual, and utilitarian needs and practices of several Native American tribes. Based on the earliest known archaeological evidence, estimates say indigenous people were the original inhabitants of what is now called Hot Springs National Park for circa 8,000 years, with Native Americans calling the region home for about

3,000 years before colonization. Some scholars believe the Quapaw lineage is traced to the Pacha or perhaps the Casqui, which lived in Arkansas in the sixteenth century. A Quapaw oral story tells of the tribe's immigration from the Ohio River Valley, which aligns with the Hernando de Soto expedition.

Curiously, little archaeological evidence exists of tribes using the hot springs themselves, though that may be due to the springs' inherent tendency to wash away such clues. The hot springs are only present on one part of Hot Springs Mountain, the lower west slope, and there is much more indication of indigenous usage of the region in other parts of the mountain. Still, there is one documentation considered reliable by researchers that is dated in 1771, well before the federal government creates Hot Springs Reservation. According to Jean-Bernard Bossu, who stayed with the Quapaw Tribe, "The Akanças country is often visited by western Indians who come here to take baths. He called the water "high esteemed by native [sic] physicians who claim that they are so strengthening. "

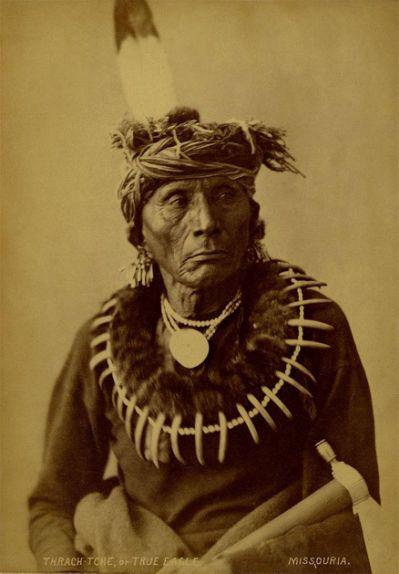

Bossu was born in France and made his way to the Midwest by way of New Orleans. Intrigued by the various Native American tribes, he sailed the Mississippi River from the land of the Natchez to "les Akanças" (Arkansas) territory—a tribe correctly and known initially as Quapaw. The Quapaw were known to regularly interact with the French throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The Quapaws' initial historical western accounts are recorded in 1673 when they met a group of French explorers. These explorers called the Quapaws les Akanças, or "People of the South Wind, " and quickly called the nearby river and countryside by the same name.

The authenticity of Bossu's numerous reports and claims of his interactions with the Quapaws may be fodder for scholarly debate. Still, it is quite likely that his note of the tribe's strong connection to the hot springs is correct. However, his writing of western "Indians" leaves much room for interpretation and suggests the hot springs were used by more tribes than the Quapaws exclusively.

The History of the Quapaw Tribe

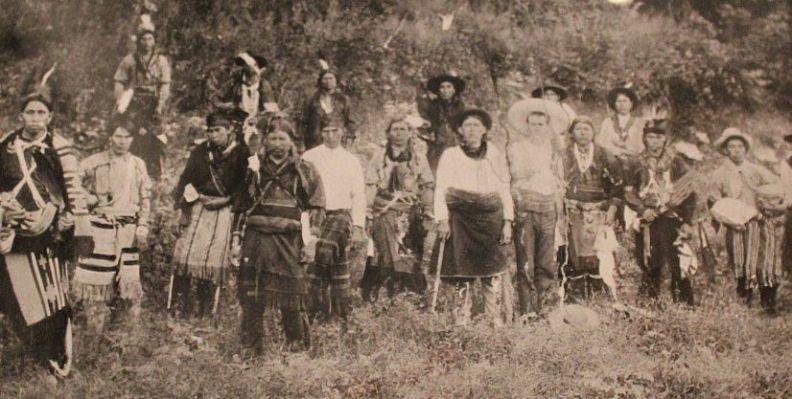

Quapaws are part of the Dhegiha Siouan language speakers (along with the Osage, Kansa, Ponca, and Omaha). In the seventeenth century, the tribe spread across four villages located along the Mississippi River. Today, three of these villages are located in what is now called Desha County. Quapaws further divided themselves into two moieties, or divisions, including Earth and Sky. They comprised of twenty-one clans. The four villages were home to longhouses that were homes to numerous families, all of which surrounded the central plaza. The council house, where meetings by the village chief and elders were held, was located near the plaza. The Quapaws were unique amongst other tribes in the area as a patrilineal culture, with ancestry traced strictly through the father's family. This culture meant that wives moved in with their husband's families, and traditionally, they could not marry within their own moiety.

However, the Quapaw did intermarry with the French, which furthered their allyship. The Quapaws are known to have fought alongside and otherwise supported the French during times of war, helping to defend the Mississippi River from the Chickasaw (who aligned with the British). France ultimately gave up the Louisiana colony—which included Arkansas—in 1762 to Spain. However, the Quapaw maintained their French ties while also extending their allyship to the newly-formed Spanish colonial government.

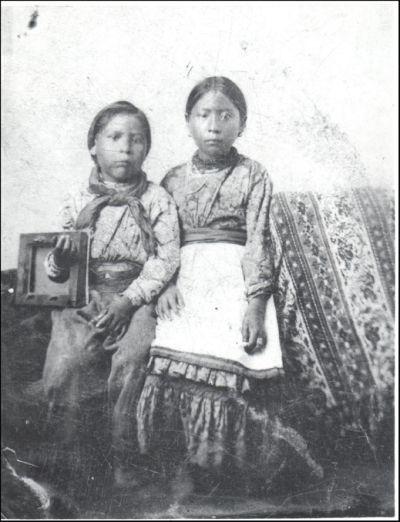

Like many Native American tribes, the Quapaw divided their labor between men and women. It was a traditional male hunter, female gatherer dynamic. The women farmed maize, sunflowers, beans, squash, and other vegetables and plants, while the men mostly hunted wild game, including bear, deer, and bison. The Quapaw hunting territory stretched from what is today called Little Rock to throughout the Grand Prairie. Novaculite (colloquially known today as "Arkansas Stone") was quarried in Quapaw territory and was a key raw material to create tools. There is a broad range of population estimates of the Quapaw tribe in the seventeenth and eighteenth century, ranging from 3,500 – 7,500. The 1698 smallpox epidemic drastically reduced the estimate to 800 –1,200, according to some scholars. Through the eighteenth century, further epidemics and raids from nearby tribes, particularly the Chickasaw, continued to reduce the Quapaw population and ultimately unified two of the four tribal villages. The two tribes did reach peace in the 1780s, which was a catalyst for the Quapaw welcoming the Chickasaw to their homeland, followed shortly by the Choctaw and Cherokee. Still, by the 1811 U.S. Census, there were twice as many white settlers as there were Quapaw in the area. It was a rush that was overwhelming to Native Americans in the region.

Ceding of Land

The Quapaw actively traded with other tribes and their white neighbors, the latter of which was growing at increasingly high rates. Corn and horses were especially commonly traded. As the white population grew at breakneck speed, the Quapaw land became more and more desirable. Since the so-called "settlers" arrived, the Quapaw did not catch the United States' eye as they did for the French and Spanish—but when the U.S. united the river banks via the Louisiana Purchase, it left the Quapaw in a non-strategic position. An 1818 treaty segregated the Quapaw to a one-million-acre reservation that ran from the Ouachita rivers to Arkansas. In this treaty, the Quapaw gave up thirty million acres to the west and south of Arkansas. In return, they received $4,000 in products and a yearly payment of an additional $1,000 in such goods. This agreement was deemed not good enough for the "settlers" who still wanted the Quapaw land remaining along the Arkansas River. After six years of intense pressure, the Treaty of 1824 was signed—which ceded much of the new reservation back to the U.S. The Quapaw were given some land on the Red River and Caddo Parish in Louisiana, $4,000 in goods and $2,000 per year in additional goods, but only for the next eleven years. The treaty was highly specific, even allowing some reserved land on the Arkansas River for eleven "mixed blood" families. This was likely due to the extensive intermarriage between the Quapaw and French in decades past.

Disaster Ahead

In keeping with the new treaty, the Quapaw headed to Caddo in 1826 but were met with non-stop disaster. A flood destroyed their crops, and 60 Quapaws starved to death. Many consider intentional confusion of the treaties' bureaucracy that gnawed away at the tribe's confidence in the U.S. government and its agents. Six months after the move, the tribe split, and one-quarter returned to the Arkansas River, led by Sarasin, a Quapaw leader, leaving principal Heckaton behind. The U.S. government begrudgingly gave 25 percent of the annual goods to Sarasin in Arkansas but did not allow the funds to be used to buy any land. This was a means of trying to force Sarasin back to Caddo. Most refused to go back and instead became squatters in what is now called Pine Bluff in Jefferson County. They became hired hands, hunting and picking cotton for numerous white families. Committed to returning home in full force, the tribe leveraged their annuity and convinced Governor George Izard to purchase agricultural tools and fund schooling for ten tribal children. By the end of the decade, every Quapaw came home to Arkansas. This did not go over well with the U.S. government. By 1832, the tribe was told that only Sarasin would be allowed to stay. One year later, the Quapaw were in dire conditions, many finding refuge in nearby swamps. This led to the Treaty of 1833, which delegated 96,000 acres to the tribe. Many did not make the move to the new reservation, which further split up the tribe.

Quapaws Today

Today's Quapaw Nation is in northeastern Oklahoma. They were recognized by the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act as one of the historic tribes from eastern Arkansas and are today consulted with on all Native American centric archaeological sites based in Arkansas. The reclamation of Quapaw land is slow but blossoming. In 2014, Quapaw Nation bought 160 acres close to Little Rock Port Authority, where hundreds of Native American graves are said to be located. This site is less than 60 miles from what today is called Hot Springs National Park. The Quapaws requested Federal Trust status from the Bureau of Indian Affairs in 2014, which was ultimately granted—but not before some non-Native Americans involved claimed that the real reason for the application was to build a casino. Pulaski County filed a request to deny the Quapaw application in 2015. However, in early 2019, the Quapaw Nation application was approved. The Quapaw remain one of the primary Native American tribes associated with what is now dubbed Hot Springs National Park. They maintain that the park holds a beloved cultural significance and regularly visit Bathhouse Row today. Built in 1922, the bathhouse was named Quapaw. Still, many consider that strictly for promotional reasons and not as a genuine homage to the park that spans what is traditionally Quapaw territory.