A PUBLICATION OF THE HISTORICAL NOVEL SOCIETY

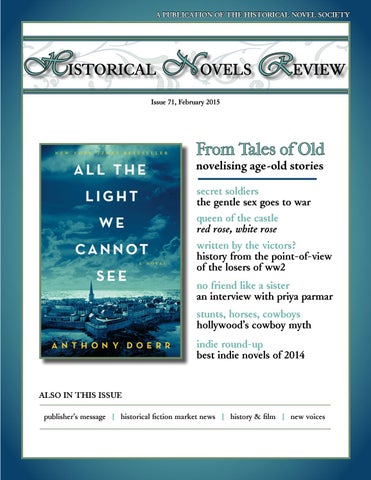

HISTORICAL NOVELS REVIEW Issue 71, February 2015

From Tales of Old novelising age-old stories

secret soldiers the gentle sex goes to war queen of the castle red rose, white rose written by the victors? history from the point-of-view of the losers of ww2 no friend like a sister an interview with priya parmar stunts, horses, cowboys hollywood’s cowboy myth indie round-up best indie novels of 2014 ALSO IN THIS ISSUE publisher’s message | historical fiction market news | history & film | new voices