A PUBLICATION OF THE HISTORICAL NOVEL SOCIETY

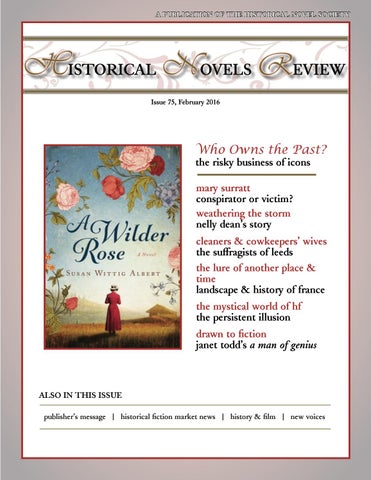

HISTORICAL NOVELS REVIEW Issue 75, February 2016

Who Owns the Past? the risky business of icons mary surratt conspirator or victim? weathering the storm nelly dean’s story cleaners & cowkeepers’ wives the suffragists of leeds the lure of another place & time landscape & history of france the mystical world of hf the persistent illusion drawn to fiction janet todd’s a man of genius

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE publisher’s message | historical fiction market news | history & film | new voices