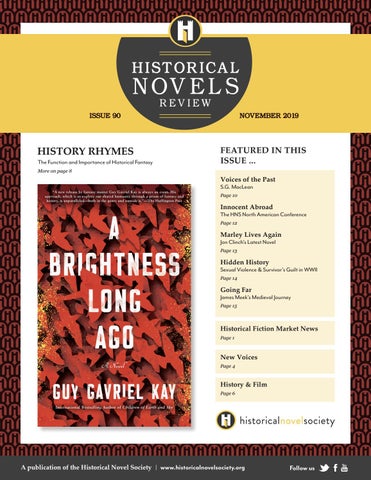

H I S T O R IC A L

NOV EL S REVIEW

ISSUE 90

HISTORY RHYMES

The Function and Importance of Historical Fantasy More on page 8

NOVEMBER 2019

FEATURED IN THIS ISSUE ... Voices of the Past S.G. MacLean Page 10

Innocent Abroad The HNS North American Conference Page 12

Marley Lives Again Jon Clinch's Latest Novel Page 13

Hidden History Sexual Violence & Survivor's Guilt in WWII Page 14

Going Far James Meek's Medieval Journey Page 15

Historical Fiction Market News Page 1

New Voices Page 4

History & Film Page 6

A publication of the Historical Novel Society | www.historicalnovelsociety.org

Follow us