11 minute read

Politics and Pleasure

Politics and Pleasure By Mark Lutyens

Meeting the needs of visitors whilst respecting the site as a royal residence made the redesign of Hillsborough Castle’s grounds a fascinating challenge.

Advertisement

Hillsborough Castle may sound defensive –all turrets and curtain walls –but it is in fact a comfortable, mainly 18th-century, golden-stone Georgian mansion in the town of Hillsborough, County Down. At 15 miles (25km) or so due south from Belfast, it is relatively close to the capital but set in rolling farm land. The only royal palace in Ireland, Hillsborough is where the British royal family and

dignitaries stay when visiting the province, and where the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland is based. Many have loved it, not least Mo Mowlem, Secretary of State from 1997 to 1999, and the driving force behind the Good Friday Agreement. Mowlem’s ashes are scattered here. Hillsborough is living history.

The castle’s north and east fronts face the town’s central

square. It used to form two sides of the square in the middle of which is a pretty, cupola-topped court house but it is separated now by the Richhill Gates, a line of ornamental railings moved from nearby Richhill Castle in 1936. The other two fronts face the gardens and grounds to the south and west: 100 acres (about 40ha) of formal gardens, pleasure grounds and lakes, set within high walls.

Management of the property passed recently from the Northern Ireland Office to HRP (Historic Royal Palaces, the organisation that manages Hampton Court, the Tower of London, Kensington Palace, Whitehall Palace and the Dutch House at Kew) who are preparing to re-open it to the public in 2019. To that end, they have embarked on an extensive programme of restoration and improvement with a view to attracting 250,000 or more visitors a year.

In my role as a landscape architect, I have been advising on the garden works with the Irish designer and gardener Catherine FitzGerald from Glin Castle, Co.

Limerick. Balancing the need to cater for so many visitors and to provide yearround attractions for all age groups and abilities whilst respecting the existing fabric and spirit of place has not been easy. Added to which, as the castle will continue to be a royal residence and host official ceremonies, the security issues are formidable. In all, it has been a fascinating challenge. There are, in fact, two castles at Hillsborough –the present house and the old fort on the other side of the central square, complete with its own park (now also managed by HRP) – linked by a lime avenue. The fort was a Cromwellian stronghold built by the Hill family, West Country adventurers who prospered, becoming some of the largest landowners in Ireland. The new house was built by Wills Hill (1718-93), Whig politician, Secretary of State for the Colonies (1768-82) and 1st Marquess of Downshire, whose high-handed attitude towards Benjamin Franklin was partly responsible for the loss of America. Subsequent marquesses enlarged the house and developed the grounds. After Irish partition in 1925, the British government bought it as a residence for

the Governors General, and, after 1972, it became home to the Secretaries of State for Northern Ireland. Hillsborough Castle’s most recent claim to fame was as the site of the Peace Agreement of 2010.

The layout of the current gardens owes much to the history of its development. Layers of improvement and changing ownership over several hundred years – and very much continuing today – give it a rich texture.

Because the town has grown around it, Hillsborough has never achieved the single Brownian vision its creator might have wished for. In 1810, James Webb (a partner of the more famous landscape gardener William Emes) produced plans, but they seem never to have been implemented. However, the intention was clear, and to that end a major public road was moved and part of the town demolished and relocated outside the new garden walls. But there remains a strong east-west axis, the famous Yew Tree Walk that dominates the south front, and an incongruous Quaker cemetery not far from the house.

The formal gardens are, therefore, somewhat constrained but nevertheless manage to wrap around the house to create a series of rather grand spaces used for royal garden parties and other formal gatherings, including weddings and gun salutes. The smaller, more intimate, spaces soften the place and serve to remind one that this is still a house with a garden – and a home. These are the areas that Catherine FitzGerald and I have been working on for the last few years, mostly replanting but carrying out some structural works too, including removing the purple gravel on the South Terrace and replacing it with reclaimed Yorkstone paving, and creating a new pool and fountain in the Jubilee Parterre. A further ‘constraint’ – although this is what makes the Hillsborough grounds distinctive – is topographical. There is a substantial glen or valley running through the land, making it, in effect, a garden of two halves: on one side is the house and formal gardens; on the other is the Walled Garden. The two halves are divided by a deep ravine. In the glen is a river which, where the valley

Opposite page: A bird’s-eye view of Hillsborough Castle and gardens and their relationship to the town. (Historic Royal Palaces.) Left: The Jubilee Parterre used to be dominated by over-large Irish yews.

Left: New plantings on the South Terrace looking towards the south front of the house. Above: The William Byers 1788 plan of the estate upon which the restoration of the Walled Garden is based.

broadens, has been dammed to create a large lake. In its middle is an island or ‘crannog’ – one of those romantic island fortlets found throughout Scotland and Ireland. On it, are traces of a settlement which are thought to have been the medieval stronghold of the Magennis chiefs, one of the principal clans of County Down and ancestors perhaps of the late Martin McGuinness, recently Deputy First Minister. With its hard frosts and biting winds, this part of Northern Ireland can be cold, but the glen provides some protection, creating a microclimate in which acid-loving plants thrive. As a result, there are many fine old trees and the remains of a string of picturesque gardens and walks. In the coming years, the glen will be restored and improved. We have drawn up sketch plans and ideas based in part on a visual assessment of what is currently there. This includes landscape fragments (bridges, paths, rock features and landform) and the existing planting. We have also made a study of old maps and plans of the estate, which suggest the character of what there was but lack enough detail to allow us to effect a full restoration. This has, in many ways, been very liberating, both for us as designers and for our clients. HRP is primarily a conservation organisation. Its dilemma, as for all modern bodies in the heritage business, is how to provide access for the many without destroying the thing that makes it special: how do you accommodate 250,000 visitors in a garden designed for a single family and friends? In addition there are statutory requirements to provide disabled access to most areas (namely wheelchair paths and ramps), car parking, a ticket office, lavatories and, in Hillsborough’s case, high levels of security.

As luck would have it, part of the estate lies adjacent to the A1, the main Belfast to Dublin road. This is currently being turned into a large car park with a new sliproad off the main highway. Close to it will be the visitor centre – ticket office, café, loos, shop and a small children’s play area – all of it housed within the lower part of an old walled garden. This is being restored and will be the chief access point to the main gardens and castle.

The Walled Garden, which opens again in 2019, will be one of the principal attractions. The original four walls remain, but the 5-acre enclosure (about 2ha) is otherwise more or less empty, grassed over and grazed occasionally by sheep. In its Edwardian heyday it was busy and industrious, with glass houses, hot houses, a kitchen garden, herbaceous borders and wall-trained fruit trees, a few of which still survive. The hot houses were some of the earliest in Ireland, producing grapes, pineapples, melons and other exotics. We

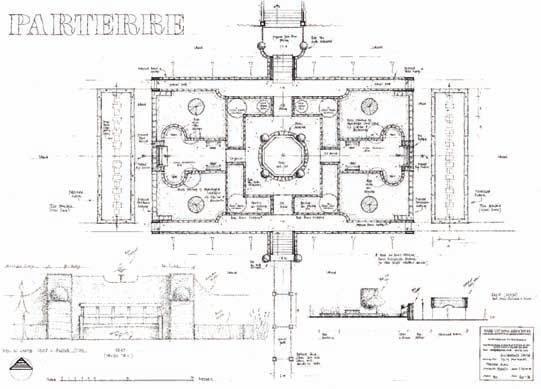

Above: The master plan for the new Jubilee Parterre. Below: A view of the Jubilee Parterre taken from the house showing the new pool and plantings. All images courtesy of Lutyens Fitzgerald except where indicated.

will, however, be recreating the layout shown in the Byers map from 1788, albeit with a few adjustments to cater for modern demands.

William Byers was a surveyor who was commissioned to make a map of the town, the castle and its grounds (known as the Great Park), and the new house (now Hillsborough Castle) and the land around it (known as the Small Park). It is an interesting document because it plots the moment when the family’s focus was shifting from the old house to the new; from the discomforts of the fort to the elegance and greater domesticity of a Georgian house.

Originally, the entire area seems to have been cultivated but, for the time being, we plan to restore only the lower half. The upper half will become an orchard planted with Irish apple varieties chosen partly for the poetry of their names – Munster Tulip, Lady Fingers of Offaly, Irish Peach, Ross Nonpareil, Ballyfatten, Kilkenny Permain. Grafting material is being collected from all over Ireland and propagated.

The current focus is on the infrastructure works (the car park and visitor centre) and restoration of the Walled Garden. However, there are two further ‘projects’ slowly being developed in parallel. The first is the making of the so-called Lost Garden in the upper part of the glen – a boggy, heavily wooded wilderness with steep sides. Along the length of the little winding river is a series of

dilapidated sluices and cascades. Old maps show that there may have been quite extensive gardens here, and a single lofty Trachycarpus fortunei, Chusan palm, suggests the type of planting that there might once have been.

Using these maps and some degree of imagination, we have designed new gardens with a distinctly exotic feel. We hope the plants with big, bold leaves and outlandish flowers, tall bamboos and mossy paths will appeal not only to serious plantsmen but to children, too, firing their imaginations and kindling a spark of curiosity. The predominant theme is the Southern Hemisphere, and a large part of the planting will consist of material collected from the Southern Hemisphere gardens at Grey Abbey on nearby Strangford Lough and grown on by Neil Porteous, head gardener at the famous Mount Stewart gardens in County Down. The cascades will be restored, paths made and bridges built. For the more adventurous, there will be a crannog or two and a warren of boardwalks to explore in the swamp.

The second project relates directly to children’s play: not the formal kind provided by modern playgrounds, but wild, unstructured play that reconnects youngsters with nature and the world of make-believe.

We have been working with Tim Gill of Rethinking Childhood (rethinkingchildhood.com), who has made a number of recommendations for the grounds at Hillsborough Castle, in particular for the remoter corners of the estate where the trees are thicker and wild things lurk. The great charm of Tim’s approach is that it is so simple and so unexpectedly obvious. In an age of increasing selfawareness and risk aversion, he encourages children to forget

themselves and play using ‘found’ things, such as fallen branches and other natural materials. HRP, to their great credit, whilst an organisation that is necessarily risk averse, has been promoting Tim’s work across all its properties wherever possible.

To conclude, Hillsborough Castle, which has known good times and bad, will shortly rise again bigger and better than before. And, as the visitor income starts to come in, it will, we hope, continue rising.

Mark Lutyens is a landscape architect and garden designer based in London and West Somerset. He is the great, great Left: The sketch shows our idea for a crannog: a children’s feature for one of the swamp areas. Above: Our designs had to bear in mind Hillsborough’s royal and official function.

nephew of Sir Edwin Lutyens and a keen supporter of The Lutyens Trust, the charity that protects and conserves his work. (See http://www.lutyenstrust.org.uk.)

The author wishes to thank Catherine FitzGerald whose sensitivity to the spirit of a place is unparalleled. Many thanks to Terence Reeves-Smyth, whose ‘Occasional Paper’ No. 1 (2015) for the Northern Ireland Heritage Gardens Trust, ‘Hillsborough Castle Demesne’ has been invaluable not only for this piece but for our work at Hillsborough more generally; and to Dr Christopher Warleigh-Lack, HRP curator at Hillsborough, for many of the illustrations.

Left: Attractive new plantings and paving replaced the original purple-gravelled sweep.