11 minute read

This Little Paradise

By Josepha Richard

Advertisement

British Library (Add.Or.2127).

A study of aviaries offers an intriguing glimpse into cultural exchanges between 18th- and 19th-century China and the world.

In A Dissertation on Oriental Gardening published in 1773, Scottish-Swedish architect Sir William Chambers presented designs inspired by buildings he had seen in China, various examples of chinoiserie, and his own imagination. A prime example of an aviary built in the style promoted by Chambers could be found in Dropmore, Buckinghamshire in around 1830. This large building had side and front rooms enclosed by wire walls, topped by a dome-like centrepiece. Research has shown that the ceramic tiles used to decorate the aviary were directly imported from China. From the shape of these tiles, and the period, it seems certain that they came from the southern city of Canton (today Guangzhou). The Dropmore aviary provides us with a convenient comparison with aviaries built in China at the same period, and the tiles used invite us to retrace the origin of Sir William Chambers’s Chinese designs. Chambers visited China during a period known as the ‘Canton System’ (1757-1842), when Western trade was officially restricted to that city. Therefore, the Chineseinspired designs in his book must have come from gardens and residences in Canton.

The building of gardens in the city was thriving, thanks to the wealth generated by trade with the Western world and East Asian countries. The Hong merchants, the intermediaries that Western traders had to go through, were some of the most prolific garden builders and aviary owners. The Hong merchants were named for the buildings where their trade was conducted: the hong, more commonly referred to as ‘Factories’. These were built in a row along the riverfront of the Pearl River, and Western traders used them as warehouses, residences and offices. Westerners were allowed to visit a limited number of sites in the suburbs on the opposite side of the river, which included the plant nurseries in Fa-tee (Huadi), as well as a temple and the Hong merchants’ residences and gardens in Honam (Henan). Apart from a few streets around the Factories, visitors were kept from most of the city proper on the northern bank, and were forbidden to enter the city walls or to bring their wives to Canton.

The Canton System lasted until the Hong merchants’ monopoly was abolished at the end of the First Opium War (1839-1842) in the Treaty of Nanjing. Thanks to their frequent interactions, mutual respect and genuine friendship often flourished between Hong merchants and Western traders. The Chinese would organise ‘chopstick dinners’ in their homes to entertain foreign guests. In addition to offering banquets laden with Chinese and Western dishes and liquors and tours of their gardens, the Hong merchants engaged in casual exchanges of information. At the beginning of the 19th century, the head of Hong merchants Pan Khequa II notably provided Joseph Banks’s plant collectors with the moutan peony (Paeonia suffruticosa), as well as details about its cultivation.

We know about the Pan family thanks to American trader Bryant Tilden who was on especially friendly terms with them. In his papers, Tilden described the Pan residence in Honam, including the family’s collection of paintings, antiques and ancient books. These possessions reveal that Pan family members aspired to elevate themselves beyond their merchant social circles and to reach the highest status of scholars – equivalent to European gentry.

As part of this aspiration, they built and maintained beautiful gardens filled with a profusion of plants and animals. Tilden described Pan Khequa II’s passion for collecting birds and reptiles, and how they exchanged gifts with each other. Around 1818, Tilden wrote a long description of the fantastic aviary located within Pan Khequa II’s hong. At the time, such installations were an unusual sight for Western traders, who were often of a lower social status than their hosts:

“This little paradise is his private retreat wherein no person ever enters unless invited. […] The aviary is wired, and fronts forming [sic] the open side of it – on one end of his counting room retreat – separated only by the wire netting partition. […] A reservoir of water above the aviary and outside of it as well as out of sight, supplies a curiously contrived fountain, so made as to play over and stream down the sides of little hills and dashing among the rocks making miniature water falls […] until they empty into a small fish pond, the bottom of which is studded with pebbles of all colors. Here a great variety of singing birds come to drink perched at the banks while small fishes come to the surface & look at them, seemingly asking ‘Ayah! Don’t drink up all the water!’ […]. English friends have presented here many rare birds brought from India and elsewhere, and many others have been procured from the interior of China. Here they

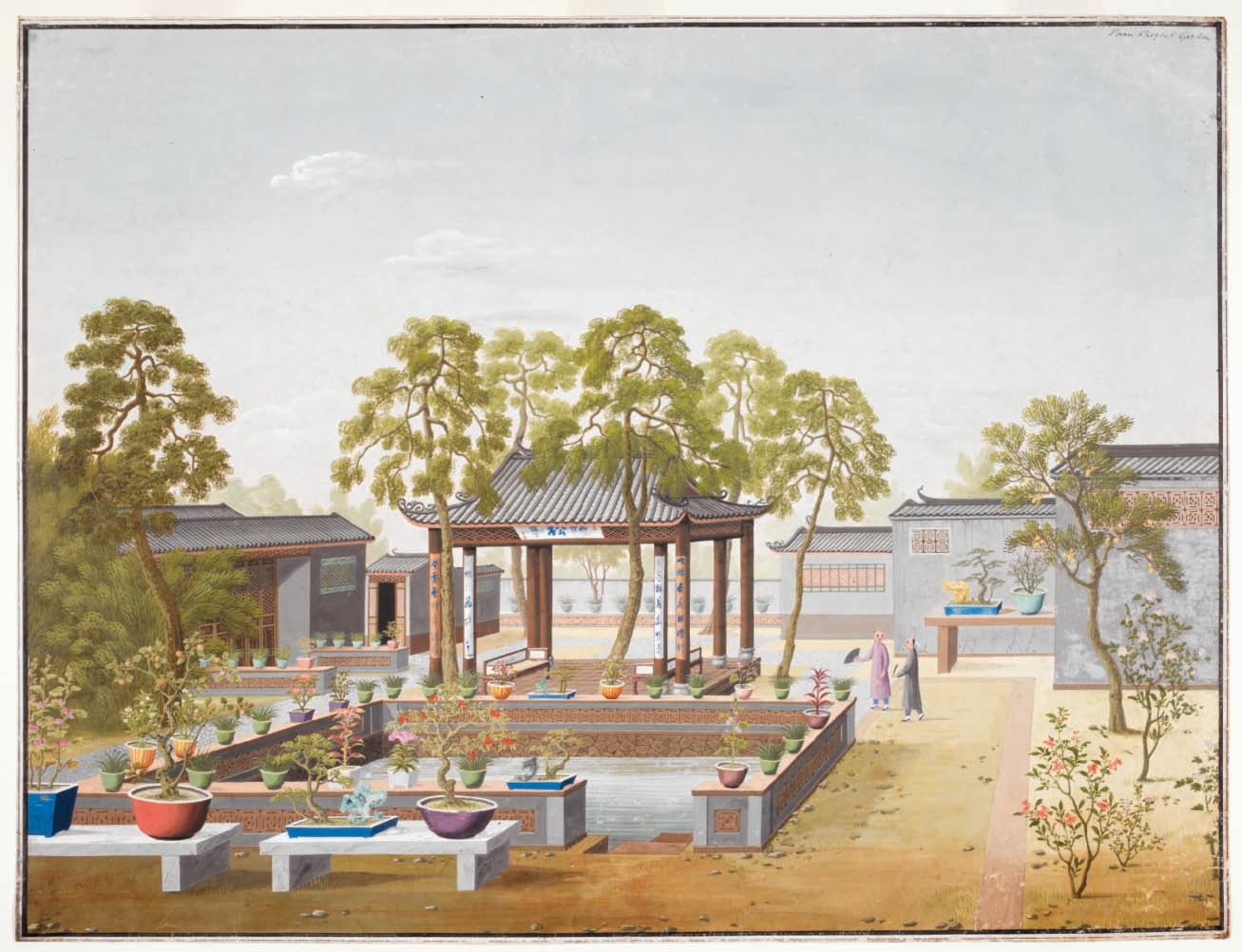

Opposite page: This drawing of a wealthy Chinese merchant’s garden was made by an unknown artist in Guangzhou around 1800-05.

Tate Museum © Anthony Raymond.

are, singing, hopping, & flying, most harmoniously together, & nothing but more room seems wanting to range in.” Pan Khequa II had obtained these birds through his contacts across China, and from his Western colleagues, who were eager to be in the good graces of powerful Hong merchants as a way to receive invitations to banquets that broke the monotony of their stay.

Tilden’s description of this aviary should, therefore, be understood in the context of its time. In Europe, many had read the fairy-tale like descriptions of China attributed to Marco Polo, and the laudatory comments left by Jesuits resident in Beijing. However keen they might have been to verify these descriptions first-hand, traders had to reconcile the exotic, orientalist vision of China prevalent in the West, with the result of their limited access to Canton and its surroundings.

Probably nowhere in Canton would chinoiserie and exotic descriptions correspond better with Chinese sites than in the Hong merchants’ residences and gardens. The latter became such a symbol of the Canton experience that local artists represented them in ‘export paintings’ for Western visitors to take away as souvenirs. An example is a painting made prior to 1805 of Pan Khequa II’s garden.

In the gardens of Canton’s wealthy élite, many animals could be found in pens, cages and moving freely within the confines of a courtyard. The first recorded gardens in Chinese history, around the Shang (1600-1046 BCE) and Zhou (1046-256 BCE) dynasties, were hunting parks containing many precious animals. The American historian Edward H. Shafer explained in The Vermilion Bird(1967) that the peacock and pheasant had been avian symbols of southern China since at least the Tang Dynasty (618-907). Apart from the wealthy Pan family, it is difficult to know who else could afford an aviary. Thanks to Tilden, we know

Beale died in Macao after some 50 years of residence. There, he had his own personal ‘paradise’ built in the garden of his mansion. Whenever Beale appears in contemporary texts, authors tend to mention his aviary, which shared at least two features with Pan Khequa II’s: the structure was made of wire and one side was linked to a room inside the house. The most detailed description of it is found in George Bennett’s Wanderings in New South Wales, Batavia, Pedir Coast, Sumatra, and China (1833). Bennett starts his description as follows: “The great object of attraction at Macao, […] is the splendid aviary and gardens of T. Beale, Esq.” and continues with details of its construction and contents, such as that the aviary was made of “lattice-work of fine wire and surmounted by a dome at the summit”.

The star of Beale’s aviary was without doubt a splendid bird of paradise, to which Bennett immediately gave Linnaeus’ name: Paradisaea apoda. By the 1830s when Bennett wrote his travel accounts, the Linnaean taxonomy was no longer a novelty, but had played a significant role in Western naturalists’ endeavours in China.

When Joseph Banks sent out botanists and plant collectors on behalf of the Royal Society, those naturalists used the Linnaean system to make sense of new and littleknown Chinese plants, and then bring them back to Britain. Beale’s bird of paradise was not a native of China, but came from Indonesia. Its presence demonstrates once again that Canton and Macao were at the crossroads of a global flow of trade in goods, including plants and animals.

Inside Beale’s aviary, the bird of paradise was secluded in its own private cage, so as to preserve its beauty. This practice can still be observed in one surviving example of a late 19th-century garden in the surroundings of Canton: the Yuyin Shanfang in Panyu. A peacock is kept in a stand-alone wooden birdcage in an important part of the scenery, in the main courtyard.

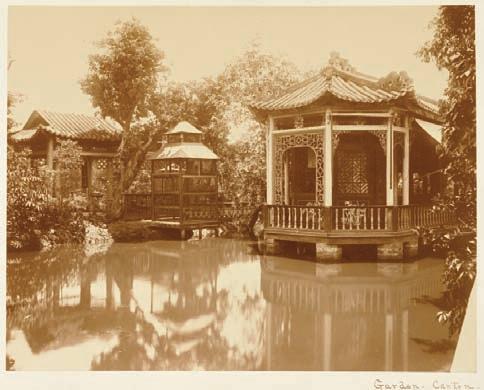

Two examples of stand-alone aviaries could be found in 19th-century Canton after the end of the Canton System. In an early photograph attributed to British photographer John Thomson, a small aviary occupies a prominent spot in an unnamed garden. The aviary appears similar to Beale’s except for its smaller size and is made with lattices of fine wires and topped by a domed roof.

The second example appears in a daguerreotype made by French customs inspector, Jules Itier, in the 1840s. Part of a diplomatic mission, Itier spent time in the home of one of the Chinese representatives: Pan Shicheng (also known as Pan Tsen Chen, and Puntinqua), a cousin of Pan Khequa II, owned arguably the largest and most famous garden in Canton. His Studio of the Immortals from the Seas and the Mountains (Haishan xianguan) was made up of a series of waterscapes connected by corridors and elegant pavilions. that in 1819 the Dutch Factory contained a monkey and several birds, most of which were imported from Dutch colonies. The only other recorded example of an aviary in the region before the Opium Wars was in nearby Macao. Since restrictions to their movements were quite severe, Westerners were usually in China to pursue a specific professional goal, be it trading in tea, serving as missionaries or collecting plants. Outside the trade season, most traders returned home or retired to Macao where their families could reside. Thus, Macao became a home from home for some long-term residents who yearned for the comforts of a permanent residence. The homes of individuals such as British trader and naturalist Thomas Beale (c1775-1841), became a source of interest for other Western visitors.

Arriving in China in 1792 when he was 17 years old, Above: A peacock cage in Yuyin Shanfang, Panyu, Guangzhou. Below: ‘Garden, Canton’ by John Thomson is an albumen silver print made around 1866. Josepha Richard. Getty Open Content Program.

Canadian Centre for Architecture.

Above: Pan Tsen Chen’s house and aviary, 1844 (detail). This early daguerreotype by Jules Itier has been modified to make it more legible and reversed to show the correct orientation.

Above right: ‘View of a two-storey building in a garden, Canton (now Guangzhou), China’ (detail). An anonymous albumen silver print, made between 1862 and 1879. Note the aviary on the far left.

Itier’s views of the garden are scarcely legible, but one of them reveals a large stand-alone wire aviary with a square base and a dome-like pinnacle standing in water near the summer house. The aviary’s important location in the garden is confirmed by later views, such as a watercolour by George R. West and an anonymous photograph held by the Canadian Centre for Architecture.

It is uncertain whether the aviary in Pan Shicheng’s garden was typically Chinese, or whether it was based on examples built by Western traders. Some 19th-century Western observers boldly asserted that Chinese gardens of the period were modified for the pleasure of their foreign visitors, but we should treat such statements with caution. After all, the Hong merchants were in a powerful position until the end of the Canton System and, after the Opium Wars, the local population was understandably wary of foreigners. It was perhaps not desirable for Chinese garden owners to imitate an antagonist’s architectural style.

In fact, imitation seems to have gone the other way. In late 18th-century Britain, many gardens were adorned with ‘Chinese’ elements, such as the aviary at Dropmore, which combined two design elements found in Canton at the time: wire panels and a dome.

Aviaries and their contents offer an alluring reflection of the intricacies of exchange between China and the world in the 18th and 19th centuries. Although the interest in chinoiserie faded in the West after the Opium Wars, the display of bird cages in gardens is still part of everyday life in southern China.

Dr Josepha Richard (University of Bristol) is an art historian specialising in the art of Chinese gardens, with a specific interest in studying SinoWestern interactions under the Qing dynasty (1644-1911).