Discover nature’s resilience this season

WETLAND HABITAT

The accidental rewilding success that transformed farmland into a thriving wildlife oasis

NATURE BASED SOLUTION

Evolution of the crucial Solent Waders & Brent Goose Strategy

Hampshire & Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust

Digital copies of Wild Life magazine are also available. If you would prefer to receive a digital copy, please email membership@hiwwt.org.uk and we will update your record.

Thank you to all our members who generously donated to the Trust’s New Forest Land Appeal. Your collective support has brought us closer to realising the vision of connecting habitats from Forest to Foreshore, with this crucial land purchase in the Lymington Valley

This land is believed to be the last stronghold for water voles in the lower valley and is frequented by otters. The Lymington River supports sea trout and North Atlantic eel, while white-tailed eagles, marsh harriers, and kingfishers are often seen at the water’s edge. We will now be able to extend the Lymington

Reedbeds Nature Reserve and establish a critical corridor to protect Hampshire’s wildlife. In the Spring 2025 edition of Wild Life, we hope to be able to report on the completed purchase and the Trust’s plans for long-term conservation of the site. We are also delighted to share some more fantastic news. The Trust has successfully secured a grant of £479,328 from The National Lottery Reaching Communities Fund, making them the primary funder of our Wilder Communities initiative. This funding will support our community engagement on the Isle of Wight, in Southampton, and throughout Hampshire over the next four years. Turn to page 18 to discover how our dynamic Team Wilder initiative is inspiring and empowering communities across our two counties.

In August, The Wildlife Trusts published a vision for the return of beavers to England and Wales which makes the case for bringing back this keystone species to rivers. As reported in the spring 2024 edition of Wild Life, the Trust’s work preparing a wild beaver release continues. After five years of dedicated study, research, and community engagement, the Trust sees beavers as a key natural solution to many challenges facing the

Registered charity number 201081. Company limited by guarantee and registered in England and Wales No. 676313. Website hiwwt.org.uk

● We manage 67 nature reserves.

● We are supported by over 29,000 members and friends, and 1,500 volunteers.

Hampshire & Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust is registered with the UK Fundraising Regulator. We aim to meet the highest standards in the way we fundraise.

Cover image Otter © Shutterstock

Isle of Wight rivers. We believe these remarkable animals will stimulate nature’s recovery, restore habitats, increase species abundance, and provide a range of ecosystem services that benefit both local communities and the wider island. Read more about The Wildlife Trusts’ vision here: www.hiwwt.org.uk/ new-vision-beavers

For loved ones who are also passionate about wildlife, a perfect Christmas gift could be a membership to the Trust which includes a pack to open for Christmas and a year of Wild Life magazines. Family members will also receive junior membership. For more information, visit www.hiwwt.org.uk/shop or contact our friendly membership team on 01489 774408.

Thank you to all our members for your continued support. Together, we are making a lasting difference for wildlife and wild spaces, and we are deeply grateful for all you do to help us in our mission.

Helen Skelton-Smith, Editor

Email: webmarketing@hiwwt.org.uk

You can change your contact preferences at any time by contacting Hampshire & Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust at:

Email membership@hiwwt.org.uk

Telephone 01489 774400

Address Beechcroft House, Vicarage Lane, Curdridge, Hampshire SO32 2DP

For more information on our privacy notice visit hiwwt.org.uk/privacy-notice

Please pass on or recycle this magazine once you’ve finished with it.

4 Your wild winter

The best of this season’s nature, including hibernating hedgehogs.

8 Reserves spotlight

Take a closer look at Fishlake Meadows Nature Reserve.

10 Wild news

A round-up of the latest Trust news, successes and updates.

18 Team Wilder

Discover how the Trust’s dynamic Team Wilder initiative is empowering communities to take action for nature.

22 Safeguarding the Solent

Find out how the Solent Waders & Brent Goose Strategy is tackling the growing challenges faced by the Solent’s wading birds.

16 A word from our CEO

A column from Debbie Tann MBE, Hampshire & Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust Chief Executive.

17 Photo club

Celebrating our two counties through our favourite staff photos.

26 Brilliant birds of prey

Discover six places to see raptors this winter.

28 Wildlife gardening

Eight fantastic fruit trees for gardens.

30 My wild life

Aggie Thompson, Nature-Based Solutions Officer, talks about leading the ecological and environmental monitoring programmes for the Trust’s rewilding projects.

The best of the season’s wildlife and where to enjoy it.

Hedgehogs are fascinating creatures known for their distinctive spines and nocturnal habits. As the weather cools in autumn, hedgehogs prepare for hibernation, a crucial survival strategy that helps them endure the cold winter months when food is scarce. Before entering hibernation, these small mammals engage in a feeding frenzy to build up fat reserves, which provide the energy needed to survive the winter without eating.

Typically, hedgehogs seek sheltered spots for hibernation, such as under piles of leaves, in dense shrubs, or in compost heaps. During this period, their metabolic rate significantly decreases, allowing them to conserve energy. Their body temperature drops, and they enter a state of torpor, which can last for several weeks or months, depending on the severity of the winter.

In spring, as temperatures rise and food becomes more abundant, hedgehogs emerge from hibernation. However, they face numerous challenges, including habitat loss, road traffic, and pesticides, which threaten their populations. By creating hedgehog-friendly environments, such as leaving garden waste piles and providing access to safe passageways, everyone can play a vital role in supporting these endearing creatures during their hibernation and beyond.

HELP HEDGEHOGS THIS WINTER

Avoid disturbing hibernation areas

Hedgehogs have a very slow metabolism during hibernation. Any disturbance may lead them to wake up and deplete their precious energy reserves that they cannot afford to lose.

Leave out fresh water in a shallow dish

Dehydration can be a serious risk for hedgehogs, especially if they wake up early from hibernation.

Avoid harmful chemicals in your garden, such as pesticides and slug pellets

The active ingredients can remain for several months. They harm hedgehogs and also reduce their natural food sources, like insects and slugs.

In October 2024, the British Hedgehog Preservation Society and the People’s Trust for Endangered Species launched the UK’s first national conservation strategy to halt the alarming decline of hedgehog populations. Hedgehog numbers have declined by up to 75% in rural areas since 2000. The strategy calls for urgent, coordinated efforts between conservationists, policy-makers, and the public to protect this beloved species.

Badgers are highly social animals that live in groups called clans, sharing extensive underground burrow systems known as setts. Their social structure facilitates foraging, grooming, and raising young together. During winter, when food sources can be scarce, their social structure becomes even more vital, as clan members rely on each other for foraging and warmth.

Badgers play a significant role in connecting wildlife corridors, especially during the winter months. Wildlife corridors are routes that allow animals to move safely between fragmented habitats, reducing the risks associated with habitat loss and human development. Badgers often use established routes and paths to navigate these corridors. In doing so, they not only help maintain connectivity between different habitats but also promote social interactions.

Coastal ecosystems are crucial for bird populations. They provide safe feeding grounds, breeding sites and resting areas. The rich feeding grounds of the Solent provide overwintering birds, including dark-bellied brent geese, with an abundance of food. These geese feed primarily on eelgrass and other coastal vegetation, which are abundant in the intertidal zones, making the Solent a crucial wintering habitat for them.

Brent geese are winter visitors to England, arriving between October and November, after an epic migration from their Arctic breeding grounds. Dark-bellied brent geese travel from the tundras of Siberia, while pale-bellied brent geese (which are less common in southern England) migrate from Arctic Canada and Greenland.

Dark-bellied brent geese are known for their striking black heads and necks, contrasting with their white chests and brown bodies. This coloration allows them to blend into their coastal environments,

providing camouflage against predators while they search for food. They are also characterised by their long legs and bills, which they use to probe the mud and sand for food.

They gather in large numbers (around 30,000) along the Solent’s coastal mudflats and saltmarshes, such as those found at Keyhaven Marshes and Farlington Marshes nature reserves.

Farlington is a haven for thousands of overwintering wildfowl and wading birds (including black tailed godwit, redshank, dunlin, grey plover and oystercatcher) due to its mix of saltmarsh, mudflats, and lagoons which provide an ideal safe wintering ground, and allows them to conserve energy before their long migrations come spring. Like many species of wildfowl and waders, brent geese are long lived and site faithful, returning to family groups each winter to the same site, behaviour which they pass on to their offspring.

Farlington is also home to a wide variety

of wildlife including small mammals, reptiles, invertebrates, amphibians, plus saltmarsh and coastal plants. This rich biodiversity helps maintain the site’s ecological balance. Wading birds are also essential as they help control insect populations and contribute to nutrient cycling.

The arrival of brent geese not only signals the changing seasons but also highlights the need to protect their fragile habitats, which face threats from climate change, habitat loss, and pollution. As human activities increasingly impact these habitats, the importance of conserving these ecosystems has never been greater.

Conservation efforts, such as the establishment of protected areas and sustainable management practices, are crucial for safeguarding these beautiful birds and their environments. Turn to page 22 to discover more about the Trust’s conservation work for brent geese and wading birds.

Known for its distinctive, haunting screech, the barn owl is often active at night and can be heard hunting for small mammals like voles and mice.

Otters have scent glands that produce a strong musky odour, known as sprain. They use this smell to mark their territory, especially near water bodies where they live.

These resourceful animals are nature’s master opportunists, effortlessly adapting to various environmentsfrom bustling urban landscapes to serene countryside.

Urban and rural foxes exhibit distinct behaviours and adaptations shaped by their environments. Urban foxes tend to be more social and bolder, often scavenging for food in city bins, skips and gardens, while rural foxes rely on hunting small mammals and birds in open fields and woodlands.

Urban foxes have adapted to human presence, frequently foraging during the day to avoid nighttime traffic, whereas rural foxes are primarily nocturnal. Additionally, urban foxes may have smaller territories due to the dense environment, while rural foxes roam larger areas. However, both types of foxes share a common ability to thrive in diverse habitats.

Foxes are opportunistic feeders, often scavenging for food, which can include small mammals, birds, and even carrion. As temperatures drop and food becomes scarce, these clever and resourceful animals depend increasingly on their keen senses and hunting skills. They also adapt their behaviour to the cold season

by caching their food for later, ensuring they have sufficient provisions to last throughout the winter months.

Urban areas provide excellent opportunities to see these clever animals, as they scavenge in gardens, parks, and near bins for food. In rural settings, foxes can be observed in fields, hedgerows, and woodlands, often hunting for small mammals beneath the snow. Look for them at dawn or dusk when they are most active. However, in winter they may adjust their activity patterns to forage during warmer parts of the day, too.

During the colder months, foxes utilise remarkable adaptations that help them thrive in harsh conditions. Their thick, bushy fur grows even thicker in winter, which provides fantastic insulation against the cold, while their bushy tails serve as both a blanket to keep warm and a tool for balance during swift movements.

Socially, while foxes are generally solitary animals, they can form small family groups during this time to help raise their young and share resources, making them fascinating survivors in the winter landscape.

Shrews do not hibernate. However, they do shrink in size (including their liver, brain, and skull), which helps conserve energy.

Great tit

Great tits adapt their winter diet by foraging for high-energy foods like seeds, nuts, and berries. They also search for dormant insects and cache food – hiding seeds and nuts in various locations, to retrieve later when food becomes scarce.

Common seals are skilled divers, foraging for fish and crustaceans in our chilly waters. Their keen eyesight and sensitive whiskers help them locate prey even in murky conditions. Watch them resting and warming up in the sun near Farlington Marshes Nature Reserve.

Located north of Romsey, Fishlake Meadows Nature Reserve spans 60 hectares and includes a mosaic of fen, reedbed, wildflower meadow, chalk stream, open water and scrub, which provide a sanctuary for a diverse range of wildlife.

The reserve is particularly renowned for its rich birdlife, including bitterns, kingfishers and marsh harriers, while its waters are home to otters, dragonflies, and various amphibians.

From agriculture to abundance Sometimes unintended consequences can yield the most amazing conditions for wildlife to thrive. Nature has an incredible ability to bounce back when given the space and time. In less than 20 years, Fishlake Meadows took fate into its own hands, and while people were contemplating the future for the land, it did something remarkable. From a previously drained, intensively

managed series of agricultural fields on the doorstep to Romsey town, it is today one of the best accidental rewilding sites to visit. Few people would realise that this rich wetland site hadn’t always been so. This area of floodplain on Romsey’s northern boundary and bordered by housing and industrial development provides the most impressive natural gateway into a town closely associated with the River Test. It could be argued that the complex series of lakes, ponds, river, reedbeds, willow scrub and wet grassland is a glimpse of how the Test Valley could have looked many centuries ago before land drainage, milling, navigation and agricultural expansion

reshaped the valley.

The sensory experience of visiting Fishlake Meadows is almost unrivalled. Visually, the reserve provides a glimpse of something different at every turn, whether watching the flow of water and various fish species in the former barge canal or looking across floodplain habitats from the raised tow path. The Trust likes to think that a healthy environment is one that you can hear. The diversity and abundance of birdlife throughout the year does not disappoint; from the dawn chorus during the nesting season, to the cacophony of wintering birds coming into roost.

During autumn and winter, the number of wetland birds using the lakes and adjoining vegetation to roost and feed will increase in their thousands, particularly gulls and wildfowl. As the cold increases, birds will seek Fishlake’s sanctuary from further afield. Ducks such as widgeon will have travelled from Scandinavia or further. Great-white egret are now a common sight, while previously rare cattle egrets are now more frequent. By January, the haunting, booming call of the bittern can be heard. Once one of the UK’s rarest wetland birds, this secretive member of the heron family stealthily hunts for fish

Above: Strategically placed viewpoints o er excellent positions for birdwatching: enjoy unobstructed views of a diverse array of birds gracefully gliding across the tranquil waters.

on the reed edges. Their booming call is a sign that a male bird is seeking a mate to nest within the undisturbed reedbeds.

Surprisingly, one of the greatest winter spectacles are starling murmurations. In recent years, this swirling, shape-shifting display of birds coming into roost has numbered in the tens of thousands of birds and drawn visitors from across the county.

The Cetti’s warbler, typically known for being elusive and difficult to spot, is surprisingly more visible on site. Famous for its sudden bursts of loud song, this small bird can surprise visitors with its powerful voice, especially when it’s perched nearby. This summer, lucky observers were fortunate to witness its remarkable mating display, which includes a unique wing-waving behaviour – a striking performance that highlights the bird’s vibrant energy during courtship. These displays offer a rare and exciting glimpse into the secretive life of this usually shy species.

Birds of prey do not disappoint. Marsh harrier is now a regular visitor throughout the year, while osprey can be seen from early spring through to autumn fishing in the larger southern lake. Platforms have been installed in an attempt to encourage them to nest before their winter migration to west Africa. Throughout the summer, peregrine and hobby can be regularly seen hunting above the open water and reedbeds.

The nature reserve is managed in partnership with the landowner Test Valley Borough Council (TVBC). Both the Trust and TVBC led several years of determined effort to secure this special place as a nature reserve in 2017. The strength of local support from residents and visitors empowered the two organisations to ensure the reserve’s safeguard. Importantly, with extensive, but controlled access, people have become used to a local environment richer in wildlife and sounds.

With huge demands on land for development and other uses, there are incredible opportunities that come from safeguarding or creating places such as Fishlake Meadows. Fishlake has proven that local people want it, while adaptation to climate change, especially flooding, needs nature to be a solution. The partnership between the Trust and TVBC has proven that the planning system can be an important mechanism for nature’s recovery. However, the power of local support ensures that decision makers are listening.

On the ground, the reserve team and dedicated volunteers continue with a busy programme of habitat management, such as scrub coppicing and grazing.

Scrub coppicing is conducted during the winter to maintain a balanced mix of habitats. For example, willow scrub (areas dominated by young willow trees and which grows in dense clusters in moist environments) would otherwise dominate. In the summer, volunteers work to remove orange balsam, an invasive non-native species, to prevent its spread and dominance. A heartfelt thank you goes out to all the volunteers at Fishlake Meadows – work parties, wardens, surveyors, and many others – whose time and effort are vital to the reserve’s success.

Unpredictable weather results in challenging ground conditions, leading to an ongoing review of access and viewing needs. This year’s biggest challenge has been the unusually wet weather, which caused significant damage to the paths and restricted access to the viewing screens, making wellies a necessity for visitors.

The Trust has aspirations to improve opportunities to view wildlife and create a more immersive experience within the wetland. As we’ve seen with the

Location: Cupernham Lane, Romsey, Hampshire, SO51 7AB

OS Maps grid reference: SU 357 221

Parking: Visitor car park is open 8am-6pm and is located at the end of the first left turning after entering Oxlease Meadows. Alternatively, park in Romsey town.

Getting around: Disabled access is limited. Paths are wide but flooding does occur during heavy rain spells. Dogs: Please keep dogs under effective control and keep to the designated rights of way. Dogs are not allowed on the path which leads to the viewing screens in the centre of the reserve.

• Listen for the distinctive ‘squealing piglet’ call of the water rail. This elusive bird is often heard before it’s seen.

• Watch out for otters swimming gracefully through the water or foraging along the wetland edges.

• Observe the dead trees. Adding a unique character to the landscape, they stand as silent sentinels amid the vibrant wetland ecosystem.

appearance of osprey and bittern, Fishlake can allow the rare to become more abundant and visible to all. As beavers continue to recover to their historic range across England, it’s easy to envisage these ecosystem engineers very much at home and kick starting more natural processes. Adapting to a changing climate and supporting nature’s recovery will require bold thinking and making Fishlake Meadows ‘bigger, better and more joined-up’. Perhaps the planning system can continue to unlock Fishlake’s potential further.

This summer, the first oystercatcher chick was ringed at Farlington Marshes Nature Reserve, marking a significant milestone.

Anyone can help monitor bird populations by joining the Breeding Bird Survey, coordinated in Hampshire by the Hampshire Ornithological Society. After signing up with the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO), participants are allocated a 1km survey square. The survey involves a recce visit and two visits during the breeding season, which runs from April to June. Participants count all the birds that are seen or heard while walking two 1km lines across the square and record any nest counts for colonial nesting birds.

During the summer, bird ringing was conducted at Farlington Marshes Nature Reserve, where uniquely coded rings were placed on birds to monitor their movements and gather data on their populations.

After a very successful breeding season, 54 lapwings, 12 avocets, 9 redshanks, and 31 black-headed gulls were ringed. Additionally, at least three oystercatcher chicks were observed, and a ringed plover was spotted nesting, highlighting the reserve’s role as a critical

breeding ground for these species.

Bird ringing allows for effective tracking of their movements, behaviour, and survival rates. This monitoring provides valuable insights into changes in populations, migration patterns, and breeding success, ultimately improving knowledge of their ecology and supporting targeted conservation strategies across coastal habitats and ecosystems.

It helps track migratory species like lapwings, avocets, and redshanks to understand their routes and challenges during long journeys. Colonial nesters, such as gulls and terns, are monitored to estimate population sizes and breeding success. Studying resident birds also aids in identifying changes in behaviour and population dynamics over time.

An avocet chick, which was born and ringed in 2021 at Farlington Marshes, has provided valuable insights into

the species’ movement and breeding patterns. The bird was recorded at Farlington in the summer of 2022, and was next spotted 15 miles west at Titchfield Haven National Nature Reserve in 2023. In 2024, it moved back east and was found breeding at Snow Hill, West Wittering, in Chichester Harbour. This journey highlights the adaptability of these birds, the importance of having interconnected wetland habitats along the south coast, and the vital role of tracking individual birds to inform conservation.

■ The avocet has made a remarkable recovery in the UK a er facing near extinction as a breeding species in the early 20th century. Thanks to conservation efforts, including habitat protection and management, their population has rebounded to an estimated 1,500 to 2,000 breeding pairs, primarily along the eastern and southern coasts.

■ Avocets, particularly those breeding in northern and eastern Europe, migrate to southern Europe or North Africa in winter. However, avocets in milder coastal areas like southern England may remain close to their breeding grounds year-round.

The Trust has welcomed the announcement of the cancellation of the Solent CO2 Pipeline Project. ExxonMobil, the company behind the proposals, confirmed the decision after local residents, environmental groups and campaigners had voiced serious concerns during the public consultation. The project would have seen the construction of a pipeline to capture and transport carbon dioxide emissions from the Fawley Manufacturing Complex for storage under the seabed in the English Channel – with the three proposed pipeline routes posing a threat to highly protected and designated sites in the New Forest and on the Isle of Wight. Debbie Tann MBE, CEO of Hampshire

& Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust, said: “This is great news for the New Forest and Isle of Wight, and huge credit should go to the Trust members, local residents, groups and campaigners who stood up to defend nature in our two counties.

“We had raised major concerns about the lack of critical ecological data in the consultation, which made it impossible to provide valid feedback or to be able to ensure crucial habitats would not be damaged beyond repair. We understand that carbon capture technology may be required to decarbonise hard-to-reach sectors, but this must never be used as an excuse to prolong and expand fossil fuel use, and it should never come at the expense of nature.

“Whilst we’re relieved to see the scrapping of the Solent scheme, it’s concerning to see the announcement of major government investment in similar carbon capture and storage (CCS) schemes elsewhere, especially when there’s no equivalent investment in restoring nature, which is so urgently needed.

“Healthy ecosystems are not just vital for biodiversity – they are also a key tool in combating the climate crisis. The Trust will always remain committed to safeguarding the local environment and ensuring that any future developments do not come at the cost of wildlife and wild places.”

Since 2020, the Trust has led a high-profile campaign, in partnership with RSPB, against Portsmouth City Council’s proposal to build a 3,500-home superpeninsula at Tipner West.

Previously, the Council was forced to re-think its plans after 24,000 people signed a joint petition, and a record 9,000 objections to the previous Draft Local Plan, were submitted.

Whilst the Council have moved away

from the original ‘super-peninsula’, current proposals still include reclaiming land from Portsmouth Harbour’s legally protected intertidal and coastal habitats, which are vital feeding grounds and provide high-tide roosts for wading birds.

In September 2024, the Trust published a formal response to the Portsmouth Draft Local Plan Pre-Submission consultation, which includes strong objections to the content of strategic site allocation policy regarding Tipner West

and Horsea Island East. In addition, 6,000 people also responded to tell the Council that their plans for development crosses a red line.

The plan attempts to justify an exception to environmental protection laws, which the Trust argued would set a dangerous precedent for future developments. The Trust recommends a series of amendments to the Plan to boost the ambition of key policies and ensure the target to protect 30% of land and sea for nature by 2030 is achieved. These policy recommendations include increasing buffer zones surrounding watercourses and urban greening factor scores. In addition, the Trust supports Biodiversity Net Gain targets that go beyond the minimum 10%, to reach 15% or 20%. Adopting these policies will be essential for ensuring the plan delivers development that truly helps nature recover.

The Trust continues to challenge the Council to protect nature while fulfilling development goals.

The Trust owns about 320 acres along the Eastern Yar floodplain on the Isle of Wight, which consists of wet grasslands, fen and wet woodland. A large portion of the grassland has suffered biodiversity loss due to drainage which has allowed scrub encroachment and loss of species dependent on ephemeral or seasonal waterlogging.

The main river channel is disconnected from the floodplain due to historic dredging. As a result, during peak flow events in-channel water struggles to spread laterally onto surrounding land which would be the natural floodplain, and instead is forced to travel at high velocity in the main channel which can cause flash flooding at pinch points such as culverts underneath road bridges.

Funded by Natural England’s Countryside Stewardship scheme and working with Wessex Rivers Trust and the Environment Agency, the Trust has developed a capital works plan to re-naturalise the floodplain to improve degraded and damaged wetland habitats

Left: Alverstone Mead Nature Reserve functioning as a floodplain following restoration works.

and promote biodiversity.

Two key areas of restoration work have now taken place: removal of scrub and trees on the SSSI to restore fen habitats at Lower Knighton Moor, and re-profiling of watercourses at Newchurch Moors, moving downstream through Alverstone Mead and onto Sandown Meadows to re-profile sections of the main river channel and surrounding land to create and restore wetland habitats.

In its natural state, a floodplain system is a dynamic landscape, and water is abundant in the landscape in multiple channels, pools and sometimes large areas of water. This dynamism and wetness provide diversity and structure for a vast array of flora and fauna and the Trust looks forward to bringing back to this landscape.

The Solent Seascape Project, the UK’s first seascape-scale marine restoration initiative, has gained international recognition as an official United Nations (UN) Ocean Decade Action. The project joins other global UN-endorsed initiatives which bridge gaps in ocean science and foster sustainable connections to the sea.

The project is a collaborative longterm initiative, which works collectively with local communities, to restore and reconnect multiple habitats - salt marshes, seagrass beds, oyster reefs and seabird sites - across the Solent’s seascape.

The Trust plays a crucial role in restoring seagrass meadows, whilst engaging local communities and stakeholders in the process. These efforts form part of a broader collaboration to create a more resilient and healthier marine environment, which also fosters a deeper connection between people and nature.

This ambitious restoration work is an integral part of a broader mission to create a thriving seascape, which aligns with the UN’s vision for a healthier, more resilient ocean.

The Trust’s Seagrass Volunteers have been awarded the 2024 Marsh Volunteer Award for Marine Conservation. Hosted by The Wildlife Trust, the award celebrates the volunteers’ exceptional contributions to seagrass restoration and marine biodiversity. This year’s recognition is especially meaningful, as it marks the first time an entire group of marine volunteers has been nominated and won.

The Trust has launched a new Business Pledge, which leading companies, corporate members and partners from across the region have signed up to.

The initiative underscores the Trust’s collective commitment to supporting environmentally conscious business and sustainable growth, together with achieving national goals for nature recovery.

Developed in collaboration with key partner businesses, the Business Pledge is a critical statement of support, outlining the necessary actions to foster sustainable growth and protect our natural environment. It aims not only to support the alignment of business partners with the Trust’s mission, but also to encourage supportive action from the new government and local decisionmakers. This engagement is crucial, for creating a policy environment that fully supports and empowers businesses committed to doing the right thing, as well as delivering on the considerable economic opportunities directly connected to restoring our natural environment.

● Businesses interested in joining can contact Luke Maundrell, Fundraising Development Manager. Luke.Maundrell@hiwwt.org.uk

Anew study has discovered an alarming level of microplastic fragments, 2,147 items kg⁻¹ d.w. sediment (average value), were found to be prevalent throughout the intertidal mudflat sediments within the Medina Estuary on the Isle of Wight. Microplastics are particles which measure less than five millimetres, and exist in an array of shapes and forms.

Report author Liberty Turrell, a Hampshire & Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust Volunteer and University of Manchester first-class graduate, collected mudflat sediment from 16 sample sites during low tides for her undergraduate dissertation. Analysis of the mud sediment under

laboratory conditions discovered three different microplastic shapes: fibres, fragments and beads. Microfibres were present in all 16 sites.

Microfibres pose a significant threat to wildlife as they can bundle together and form clumps that block feeding pathways in the gastrointestinal tract. This can disrupt digestion and potentially lead to death.

Microplastics cause pollution by entering natural ecosystems from a variety of sources, including wastewater discharge from Combined Sewer Overflows (CSOs). The study also reveals that wastewater discharge from two CSOs with high annual spill rates (Dodnor Lane and Fairlee) are likely responsible for the high level of fibres in the Medina Estuary.

Professor Jamie Woodward at The University of Manchester believes that addressing sewage spills is crucial to ensure the health and safety of our ecosystems: “The pollution of rivers and coastal waters has become routine because of inadequate investment in

infrastructure. Effective treatment can remove up to 95% of the microplastic load in wastewater.”

The measurement ‘2,147 items kg⁻¹ d.w. sediment’ means that, on average, there are 2,147 microplastic particles per kilogram of dried sediment (where ‘dry weight’ ensures only the sediment’s weight is counted, excluding water) found across the sampled estuary area.

The Trust is asking all boat users to participate in a survey to gather valuable insights on mooring and anchoring practices in the Solent’s seagrass meadows. The results will help inform conservation efforts aimed at protecting these endangered habitats. The survey only takes a few minutes to complete and is available online at www.hiwwt. org.uk/solent-boating-survey

Participants will also have the chance to win exciting prizes: l A guided shore walk with a marine biologist for up to eight people l A year’s free Trust membership l £20 voucher for FatFace Foundation Store

The Trust has launched an exciting new partnership with local housing association, Abri, to enhance the natural environment and green spaces of the Mansbridge estate in Southampton. This first-of-its-kind collaboration unites the Trust’s expertise with a housing association to create a greener, wilder future for a local community.

Key goals include showcasing and championing the environment, visibly enhancing the estate’s green spaces, and increasing awareness of the natural environment. The Trust also aims to encourage and inspire Abri employees, customers, and suppliers to take action for wildlife, ultimately contributing to the creation of a Wilder Mansbridge. Turn to page 18 to find out more about the Trust’s work with communities across Hampshire and the Isle of Wight.

Left: Jill Doubleday, Wilder Communities Officer (Southampton) with Helen Chan, an Abri customer who volunteers at the Mansbridge community allotment.

Author and storyteller, Amanda Kane-Smith at the prize giving event.

With their vibrant beauty and incredible wildlife, our chalk streams have inspired the written word for centuries – just think of such classics as The Wind in the Willows or Watership Down. This year, we continued this rich literary tradition through our Tales from the Riverbank project.

In June, our river-themed literature festival featured talks by several acclaimed

authors: Tom Moorhouse, Lisa Schneidau, Matt Gaw and Amy-Jane Beer. Local creativity was also nurtured through nature writing workshops for children and adults, which included guided walks along our beautiful chalk streams.

In October, we celebrated the winners of our children’s poetry competition with a special prizegiving event. Congratulations

to all our brilliant chalk stream poets. These poems have been transformed into a new chalk steam poetry anthology (above) which can be viewed, along with the full list of the 16 young winners, here: www.hiwwt.org.uk/tales/poetry

The Atlantic salmon is one of our most famous chalk stream species. Beloved by anglers and renowned in folklore, this fish is a key part of our chalk stream ecosystems – in fact, the salmon in these globally rare rivers are genetically distinct from the wider UK population. Unfortunately, we could soon be facing a future without this iconic species. In recent years, salmon numbers on the Rivers Test and Itchen have fallen so low that the population is no longer considered sustainable. We are now working with other organisations, including the Environment Agency, to tackle some of the issues behind this decline.

The Itchen Salmon Delivery Plan aims to support the health and reproduction of salmon in the River Itchen. Improving water quality, enhancing spawning habitats, removing barriers, and creating undisturbed sanctuaries could all be crucial to saving this species.

Water vole

In happier news for nature’s recovery, water voles have returned to riverbanks in Overton and Alresford. Once a common sight on our chalk streams, their numbers have plummeted due to pressures like habitat loss and bank erosion. These small mammals need a thick fringe of marginal vegetation, where they can snack on plant stems while hidden from predators.

Surveys along the Flashetts and Arle Valley Trail footpaths showed no signs of the water voles that once lived there. But

after we restored the riverbank habitats, these charming animals are once again calling them home. Recent surveys have identified droppings, feeding remains, and nesting areas – all signs that the voles have what they need to thrive.

To learn more, visit hiwwt.org.uk/winterbournes

With 2025 just around the corner, we will soon be reflecting on the midway point of our Wilder 2030 strategy, reviewing progress and considering how best to respond to the challenges ahead. When we launched our plan in 2020, we called for many more people to join us in our fight for nature’s recovery, we set ambitious goals to restore, rewild and rejuvenate more land and sea for wildlife, and we embarked upon new ventures like utilising nature-based solutions to create more opportunities for nature. In the first four years, we have seen incredible progress.

Thousands of people have stepped forward to join Team Wilder and we’ve seen a wave of greening projects making our towns, cities, villages and gardens wilder. Thousands of voices have joined our campaigns to halt damaging developments or call for positive policies, hundreds of hectares of privately owned land have been brought forward for restoration, and amazing new nature recovery partnerships have formed, including in the marine environment. The Trust has acquired over 400 hectares of new land for nature in the past four years with more in the pipeline, and we are confident we will meet our target of 1,000 hectares of new acquisitions by 2030 as set out in our strategy.

I must say a huge thank you to the many, many members who contributed so generously to our recent New Forest land appeal. With your support, we far exceeded our fundraising target, and this has meant we will be able to acquire even more land to link our existing sites; creating bigger, better, more joined up wildlife corridors and nature recovery networks. We hope to be able to share exciting news on our newest land acquisitions and how they fit into our vision for nature’s recovery in the spring edition of Wild Life

However, our success in bending the curve of biodiversity loss will be impacted by government policy, and with a renewed emphasis on growth and development we will need to work hard to make the case for nature’s role in underpinning the economy. There is more and more evidence setting out the real risks to our

economy if we continue to destroy the natural world and so we need to call for stronger rules to ensure that every sector, industry, business and activity puts back more than it takes from nature.

Recent new rules like Biodiversity Net Gain and nutrient-neutrality are designed to do just that for the development sector, adding to various other mitigation strategies already in place. One of the longest standing is the Solent Waders and Brent Goose Strategy (initiated by the Trust over 20 years ago) which helps to safeguard critical habitat for endangered coastal bird species in an increasingly busy area of the south coast. You can read more about this on page 22. Other sectors like the water industry and intensive agriculture have more heavy lifting to do.

It is vital that, as a Trust, we continue to be a strong voice for nature, pushing for better policies alongside the direct delivery work we do. And it is important

to recognise our local role as making a significant contribution to the global picture as well. In September, I had the privilege of being part of The Wildlife Trusts delegation to the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) Regional Forum in Bruges. The IUCN is the largest and most influential union in the world dedicated to nature’s recovery, with thousands of experts, scientists, NGOs and Government bodies as its members, and a direct line to influencing major international agreements like the Global Biodiversity Framework. You can read about international conservation policy and why it is important that we play a role in influencing it here: www. wildlifetrusts.org/news/new-reportshows-how-uk-can-reverse-natureloss-and-lead-world-stage

Thank you for your ongoing support.

Debbie Tann MBE, Chief Executive Debbie Tann MBE

Taken by Tom Hilder, Reserves Officer (Hook).

A slow worm enjoying a freshly cleared section of open heath on Hook Common North.

Taken by Lizzie Laybourne, Nature-Based Solutions Officer

This summer, 54 lapwing chicks were ringed at Farlington Marshes Nature Reserve. Find out more about the Trusts’ ongoing bird conservation efforts on page 10

Taken by

Hazel Makepeace, Facilities & Administration Assistant (Isle of Wight).

A scarce bordered straw moth at Wilder Little Duxmore. This immigrant species favours coastal regions with wildflower-rich grasslands, and its infrequent sightings make it a notable find.

Taken by Graham Dennis, Reserves Officer (Pamber Forest).

A striking carpet moth captured at Pamber Forest Nature Reserve, showcasing its unusual red-green colouration.

Taken by Pete Whitlock, Assistant Reserves Officer (Blashford Lakes).

A rare Cortinarius saturninus found in wet ground under salix (moist soil that often accumulates beneath willow trees) at Blashford Lakes Nature Reserve.

WORDS DAWN O’MALLEY Senior Engagement Manager

Dawn has been a dedicated member of the Trust’s Education and Engagement team for over a decade. With a strong background in adult training and Forest School education, she passionately inspires people to connect with nature. Dawn advocates for the inclusion of nature in schools, organisations, and businesses to foster more nature-connected communities.

In a time where the natural world faces unprecedented challenges, the Trust is setting a bold and inspiring goal: to mobilise one in four people to take action for nature. This ambitious vision is being brought to life through the dynamic Team Wilder programme, a community-driven initiative that empowers individuals to make tangible contributions to their local environment.

Team Wilder is more than just a programme; it is a call to arms for individuals, families, and communities to engage in meaningful activities that support biodiversity and promote environmental health. Since its launch in 2021 the programme has seen

remarkable successes. From local wildlife conservation projects to widespread educational campaigns that have increased awareness and participation in nature-friendly practices, the programme is creating ripples of positive change across our region.

Central to Team Wilder’s approach is the belief that everyone has a role to play in protecting and enhancing nature. By fostering a sense of shared responsibility and providing the tools and knowledge needed to make a difference, the Trust is cultivating a powerful movement of nature champions. Whether it’s planting wildflower meadows, participating in beach clean-ups, or simply making wildlife-friendly choices at home, every action counts and contributes to the larger goal. These efforts have not only improved local ecosystems but have also strengthened the bonds within communities, fostering a collective sense of responsibility and pride in their natural surroundings.

Looking to the future, the Trust’s vision is clear: by inspiring one in four people to actively take part in conservation efforts, we can create a tipping point where positive environmental actions become the norm rather than the exception. Upcoming plans for Team Wilder include expanding educational programmes in schools, increasing support for local conservation groups, and launching new initiatives that make it easier for people to participate in environmental stewardship schemes. The Trust envisions a future where one in four individuals are actively engaged in nature conservation, creating a resilient and vibrant natural environment for generations to come.

Wilder Portsmouth marked the beginning of the Team Wilder initiative, with seed funding from The Southern Co-op, setting a powerful example now adopted by Wildlife Trusts across the country.

“It was Team Wilder that introduced us to the fact we could actually adopt these gardens.”

Lyn Cox, Victoria Road Gardeners

This pioneering project showcased the immense potential of community-driven conservation, empowering local groups to take the lead in nurturing and sustaining their own green spaces.

Supported by the Trust, residents of Portsmouth came together to restore habitats, plant native species, and create wildlife-friendly environments. The success of this initiative demonstrated that when communities are given the tools and knowledge, they can drive significant positive change in their local ecosystems.

Wilder Portsmouth’s achievements have inspired a national movement, boosted by funding from The National Lottery’s Heritage Fund to deliver the Nextdoor Nature project across Portsmouth, the Isle of Wight and Southampton, proving that grassroots conservation efforts can have a profound and lasting impact on biodiversity and community wellbeing. The legacy of Wilder Portsmouth continues to grow, as more organisations such as councils embrace the model of community-led environmental stewardship.

The Wilder Wight Communities Project, co-funded by The Southern Co-op, is

supporting people to make the Isle of Wight wilder and more nature-friendly.

One project supported by Wilder Wight is Artswork Young Cultural Changemakers Programme at St Mary’s Hospital. The young people developed a garden at the Children’s Ward with ideas like raised beds, a modular green wall, animal habitats, seating, and a willow structure. We made butterfly, bird, and bug boxes at their summer celebration event.

In Ventnor, a community orchard featuring local apple varieties like Nettlestone Pippin and Bembridge Beauty is being set

up with project support. A consultation at Lowtherville Community Centre brought in great ideas from residents, like adding herb gardens, beehives, and wildlife ponds. Whilst over on the northeastern coast in Seaview, the Sophie Watson’s Garden Volunteers are running a wildlife survey to improve their communal greenspace.

Below: Young people from the Artswork Young Cultural Changemakers Programme transformed a neglected outside space into a welcoming garden at the Children’s Ward at St Mary’s Hospital on the Isle of Wight

Across the Island, the Trust has been supporting and linking existing groups that are already making a positive impact in their communities, encouraging them to incorporate nature into their initiatives. It is important to continue to promote the benefits of nature, particularly to health and wellbeing alongside the importance of local key species, as this can contribute greatly to a sense of, and connection to, a place.

It has been wonderful collaborating with a diverse range of people and organisations from local allotments, cemeteries, libraries, youth, church and community groups, and charities. By working together, existing areas have been improved plus new spaces for both local nature and residents have been created for all to enjoy.

The Wilder Southampton project, in partnership with Southampton City Council, has been encouraging communities across the city to improve areas for wildlife.

The community organising approach involves listening to people, getting to know them and their neighbourhoods in order to empower them to take action that works. A major success story is Freemantle, where the ripple effect has been most apparent. Habitats have

been created in this area to form wildlife corridors across a previously inhospitable residential area. These have included tree planting in Freshfield Park and growing pollinator flowers at the community centre.

Additionally, the project showcases innovative approaches to urban greening, such as co-creating a wilder garden on an industrial estate with the charity Jamie’s Computers. A place for staff to relax as well as a home for wildlife, this project showcases the potential for commercial areas to contribute to urban biodiversity and people’s wellbeing.

Nature needs bigger, better and more joined up spaces across neighbourhoods to support wildlife in these areas and help nature thrive. The Greening Campaign is providing support to 20 communities across Hampshire and the Isle of Wight to adapt to climate change. There are five pillars as part of the programme: waste, energy, health, cycle of the seed and space for nature.

The Trust’s Wilder Neighbourhoods Officer is the lead, supporting communities to make space for nature. Mapping walks are taking place across communities to identify areas which can be improved or created to support nature. The programme also supports individual households to plant pollinator friendly plants and introduce other wildlife friendly features to provide food, water and shelter to connect habitats and support wildlife using the neighbourhoods. And it doesn’t stop there. Thanks to generous donors, this work reaches beyond and has enabled multiple visits to support other communities on how to create more green space, give wildlife friendly gardening talks, and create new habitat to support nature in their areas.

At its core, Team Wilder’s mission is about empowerment. By providing the tools, knowledge, and opportunities needed to make a difference, the Trust is building a robust network of nature champions. These efforts are paving the way for a sustainable future where nature and people thrive in harmony. As Team Wilder continues to grow, its impact on local communities and the environment will undoubtedly leave a lasting legacy.

Grow pollinator plants – plant a variety that bloom in spring, summer and autumn.

Create a pond – large or small, it all helps. Don’t forget access routes for wildlife.

Create corridors – plant shrubs, trees, and hedgerows to provide shelter and protection for wildlife travelling through or inhabiting your garden.

Get composting – helps recycle waste and provides amazing habitats for a wide variety of species. And you get free fertiliser!

Encourage hedgehogs – talk to your neighbours to join up habitats and create hedgehog corridors.

Leave some mess – don’t tidy everything up in autumn. Leave fallen leaves and plants to provide shelter for hibernation.

Leave sticks and dead wood –piles are great for beetles and other invertebrates.

Give nature a home – put up bird and bat boxes, bug hotels and hedgehog homes to provide additional space for nature in your garden.

To join this journey and become part of a movement that is turning the tide for nature, one action at a time, visit www.hiwwt.org.uk/team-wilder

The Trust would like to give special thanks to the wonderful funders and partners whose support has made the important work of our communities team possible. Thank you to Trust supporters Robert and Sue Falconer, The Southern Co-op, Southampton City Council, Basingstoke and Deane Borough Council, The National Lottery’s Heritage Fund and Community Fund, The Greening Campaign, and Abri.

Thomas works on coastal bird mitigation projects in the Solent, including Bird Aware Solent and the Solent Waders & Brent Goose Strategy. Drawing on his expertise gained from working with the Trust’s Ecology team, Thomas is committed to finding balanced solutions that benefit both the region’s wildlife and its communities.

When in flight, dark-bellied brent geese communicate with each other through a series of honks, coordinating their movements and maintaining group cohesion.

The Brent Goose Strategy, one of the first strategic mitigation initiatives of its kind, was born in 2002. Over two decades later, the expanded Solent Waders & Brent Goose Strategy remains a vital tool for conservationists, developers and local planning authorities looking to conserve these species in the Solent, an internationally important area for overwintering birds.

This innovative project ensures that nondesignated sites used by coastal birds are identified within a network and considered throughout the planning process. This year, the strategy is receiving a fresh coat of paint and is being updated to help guide its implementation through to the end of the decade.

The Solent is a tremendously important area, nationally and internationally, for overwintering birds. It is very highly designated, with three Special Protection Areas (SPAs) having features relating to wading birds or brent geese. However, despite this, many of the key sites that support these populations in fact lie outside of the boundaries of the SPAs. For example, brent geese frequently make use of inland areas such as cereal fields and amenity grassland, especially at high tide. This behaviour was first observed in the 20th Century following declines in eelgrass, which is the brent geese’s preferred food.

The strategy was first conceived near the turn of the millennium and has only grown in scope since. The first iteration was born out of the need to identify and conserve the areas used by brent geese in a network of connected sites. Several flagship Trust nature reserves belong to this network including Farlington Marshes, and Lymington and Keyhaven Marshes.

In 2010, the strategy expanded geographically to encompass the entire Hampshire coast and the north of the Isle of Wight, while also extending its focus to include overwintering wading birds. In this update, a huge survey effort took place, over the course of three years, to improve the accuracy of the network. The Trust took on a leading role in coordinating the survey effort alongside collating data gathered by partners including the Hampshire Ornithological Society, Coastal Partners, and Hampshire Biodiversity Information Centre. A movement study was also undertaken to explore how sites within the network relate to one another.

The Solent Waders & Brent Goose Strategy has been a collaborative partnership since its inception. It encompasses many of the conservation organisations operating in the Solent, including the Trust, the RSPB, and Chichester Harbour Conservancy, along with statutory bodies like Natural England, and all the Solent’s local planning authorities. The Trust has always played a pivotal role: taking the lead in website development, coordinating surveys, and administering the network of sites.

The strategy was developed in response to a clear need for a strategic solution to ensure (and meet a legal requirement) that development would not negatively impact protected areas, specifically the Solent SPAs. It focuses on safeguarding the feeding and roosting areas of brent geese and wading birds.

As one of the earliest examples of a nature-based solution, the strategy addresses a societal challenge of balancing housebuilding in the Solent area with the needs of wildlife by protecting and sustainably managing

ecosystems and habitats. This is achieved by identifying and securing mitigation for sites critical for overwintering birds.

A Steering Group guides the strategy. Composed of members from many of the partner organisations, it regularly meets to discuss issues relevant to the network. This group plays a key role in ensuring that mitigation is effective and of high quality, as well as mediating between developers, local interest groups, and local planning authorities.

When the network is affected by a development, there is a requirement for mitigation. This mitigation may take the form of on-site strategies, such as scheduling construction work to avoid disrupting birds when they are likely to be using the site. It may also include physical measures, such as the installation of

The barnacle goose, an occasional Solent visitor and a relative of brent geese, derives its name from the ancient belief that they, along with brent geese, emerged fully formed from barnacles. It also gave rise to the brent goose’s scientific name Branta bernicla.

screens or fences. However, when onsite mitigation is not possible, off-site solutions are required.

Off-site mitigation measures can range from small habitat enhancements, like the creation of scrapes that will attract more birds to a site, to the wholesale acquisition and restoration of new sites. These mitigation sites are managed in perpetuity for overwintering birds and contribute to the Trust’s Wilder 2030 strategy and Wilder Land & Sea initiative, which aims to protect and manage 30% of land and sea positively for nature by 2030.

The most recent update aims to tackle the growing challenges which the Solent’s overwintering birds will face in the coming years. Having identified the most important sites in the Solent, the priority now is to ensure that the integrity of these interlinked sites is maintained. However, with the government prioritising housebuilding, the likelihood of network sites being targeted for development will increase, placing additional recreational pressure on the remaining sites. Additionally, the looming threat of climate change puts several sites at risk from coastal squeeze and rising sea levels.

New housing developments around the Solent will lead to even more people visiting the coast for leisure, with the potential to cause more disturbance to birds. Bird Aware Solent (which is funded by contributions from developers building homes within 5.6km of the SPAs) works to minimise the recreational impacts that come with this increased local housing development. It aims to mitigate the effects of human activities (such as dog walking, cycling and water sports) which can disrupt vulnerable bird species.

To achieve this, Bird Aware Solent engages in public education and outreach, encouraging responsible behaviour among coastal visitors to help protect the birds and their habitats. Through raising awareness and promoting sustainable coastal use, the initiative ensures that the growing population around the Solent coexists with its vital birdlife, reducing disturbances and safeguarding critical habitats.

Left: During the winter months, 10% of the global population of dark-bellied brent geese (approximately 50,000 to 60,000) migrate to southern England. As the flagship species of the strategy, they find refuge in the Solent and surrounding coastal areas. The species has experienced large declines in the last century due to the loss of seagrass meadows, so it is essential to protect and conserve their feeding areas.

The new and updated strategy focuses on delivering rapid, well evidenced, and, most importantly, effective mitigation solutions to impacts on the network. To achieve this, an accessible, interactive

map is now available online, allowing the public to explore key sites. Additionally, species records are collected digitally to ensure that classifications remain up-to-date, and the site classification system itself has been refined for greater accuracy.

The coming years will be crucial for wildlife. This network of sites will likely come under more pressure than ever before. However, with a strong evidence base and a proven system, this crucial project can help protect these species and secure more land in recovery for nature.

Below: The largest of our wading birds, the curlew is a sight to behold with its long, down-curved bill. The curlews that visit us during winter may be different individuals to our struggling breeding populations, but maintaining their access to feeding and roosting areas remains critical to halting this species’ decline.

During the winter months, majestic birds of prey migrate to southern England in search of more favourable conditions for survival, such as milder weather and abundant food sources. These winter migrants take advantage of the favourable conditions to sustain their energy levels throughout the colder months before returning to their breeding grounds in the spring.

Many raptors, such as hen harriers, peregrine falcons, and merlins, flock to Hampshire and the Isle of Wight in winter, attracted by the diverse habitats - heathlands, woodlands, and coastal areasthat provide ideal hunting grounds where prey like small mammals and birds remain abundant.

Watching these majestic birds of prey hunt or glide effortlessly overhead is not only aweinspiring but also provides a great opportunity to learn about them and their important role in the

balance of ecosystems.

However, while birdwatching is a great way to enjoy wildlife, it’s crucial to be mindful of how we observe these birds of prey. Winter is a challenging time for them, as food sources are often scarcer, and the cold can take a toll on their energy levels. It’s essential not to feed birds of prey as this can disrupt their natural behaviours and make them dependent on humanprovided food. Approaching too closely or disturbing their habitats can stress these birds, potentially affecting their ability to hunt and survive. Avoid loud noises or sudden movements, as birds of prey are easily spooked and may abandon a hunt. Using binoculars or long-lens cameras helps maintain a respectful distance, and staying on designated paths ensures minimal disruption to their natural behaviours. By watching responsibly, we can ensure these magnificent birds thrive for generations to come.

Noar Hill provides an ideal environment for sparrowhawks due to its diverse mosaic of habitats. Sparrowhawks, which are small but powerful birds of prey, thrive in areas where they can easily hunt small birds and find cover. Noar Hill’s combination of ancient chalk grassland, scrub, and woodland edges creates a perfect hunting ground for them.

The dense shrubs and small trees that dot the reserve allow this agile hunter to ambush their prey, typically small songbirds, which are abundant in this habitat. The woodland edges offer shelter and nesting spots, while the open grasslands give them space to swoop down on their targets. This varied landscape supports a healthy population of birds and other small animals, ensuring a steady food supply for sparrowhawks throughout the year. The reserve’s peaceful setting also reduces human disturbance, giving these birds of prey the space they need to hunt and nest successfully. Where: GU34 3LW

The merlin is the UK’s smallest falcon, but it makes up for its size with speed and agility. They pursue small birds in highspeed chases. Their low, fast flight close to the ground makes them tricky to spot, but their thrilling hunting behaviour is well worth the effort for keen birdwatchers.

These small, agile falcons are often seen during the winter months when they migrate south to coastal regions, including the Solent, to hunt for small birds in the open landscapes. Merlins have been spotted around the coastal marshes and heathlands surrounding Lymington & Keyhaven Marshes Nature Reserve.

The mix of saltmarsh, mudflats, and coastal grasslands in this area provides ideal hunting grounds for merlins, as it attracts large numbers of overwintering birds, particularly waders, which are their primary prey. The relatively open terrain also makes it easier to spot them, as they fly low over the ground in pursuit of their prey. While merlins are not common and can be elusive, Lymington and its surrounding area offer one of the prime locations in Hampshire for a possible sighting during the winter months.

Where: SO41 8AJ

Near Southampton, Testwood Lakes is an excellent reserve for birdwatching, particularly in winter. The open water and surrounding fields attract a wide variety of migratory birds, and in turn birds of prey, including buzzards and red kites.

Once on the brink of extinction, red kites have experienced a remarkable resurgence since their reintroduction, with more than 300 individuals regularly spotted throughout Hampshire. Their distinctive forked tails and graceful flight make them easy to identify, and they can often be seen gliding effortlessly in search of food. The success of the red kite’s recovery is a conservation triumph.

Where: SO40 3YD

Arreton Down Nature Reserve on the Isle of Wight is a fantastic spot for observing birds of prey, especially thanks to its open chalk grassland habitat. Buzzards are frequently seen soaring over the reserve, using the updrafts created by the rolling hills to spot prey below. Kestrels are a common sight, often hovering in place before swooping down on small mammals hiding in the grass. The downland’s rich biodiversity supports a healthy ecosystem, making it a prime hunting ground for these raptors. In winter, the reserve becomes even more appealing to raptors, including barn owls, as food sources remain accessible.

Where: PO30 3AA

This coastal reserve is a fantastic location to observe a variety of wintering birds of prey, including peregrine falcons, merlins, hen harriers, and short-eared owls. The peregrine falcon - the fastest bird in the world - is a common sight during the winter months. These powerful hunters can be seen perching on tall structures or swooping down with incredible speed to catch the waders that frequent the marshes. Their dramatic hunting stoops make them a highlight for visitors, offering unforgettable views against the backdrop of the open wetlands and the Solent. The marshes’ abundant birdlife provides a steady food supply for peregrines, making it one of the best reserves to spot them in action.

Merlins fly low over the open grasslands

and saltmarshes, hunting small birds with remarkable speed and agility. Hen harriers, with their graceful flight and distinctive ‘sky-dancing’ displays, can be seen quartering the marshes in search of prey. Meanwhile, short-eared owls are often spotted gliding low over the marshes at dusk, hunting for voles and small mammals.

Where: PO6 1UN

Blashford Lakes, with its diverse mix of lakes, reedbeds, and woodland habitats, is an important haven for birds of prey, particularly during winter. This rich environment attracts large numbers of wildfowl, which in turn draw a variety of raptors, including red kites, sparrowhawks, kestrels, hobbys, buzzards, marsh harriers, and occasionally even white-tailed eagles. The combination of abundant prey and varied habitats makes Blashford Lakes a prime location for observing the fascinating hunting behaviours of these birds of prey.

Among the notable visitors is the elusive goshawk. These powerful raptors are known for their agility and strength, often using their stealth to surprise prey in dense cover. Their striking appearance, with broad wings and a long tail, allows them to manoeuvre effectively through the woodlands as they hunt.

Where: BH24 3PJ

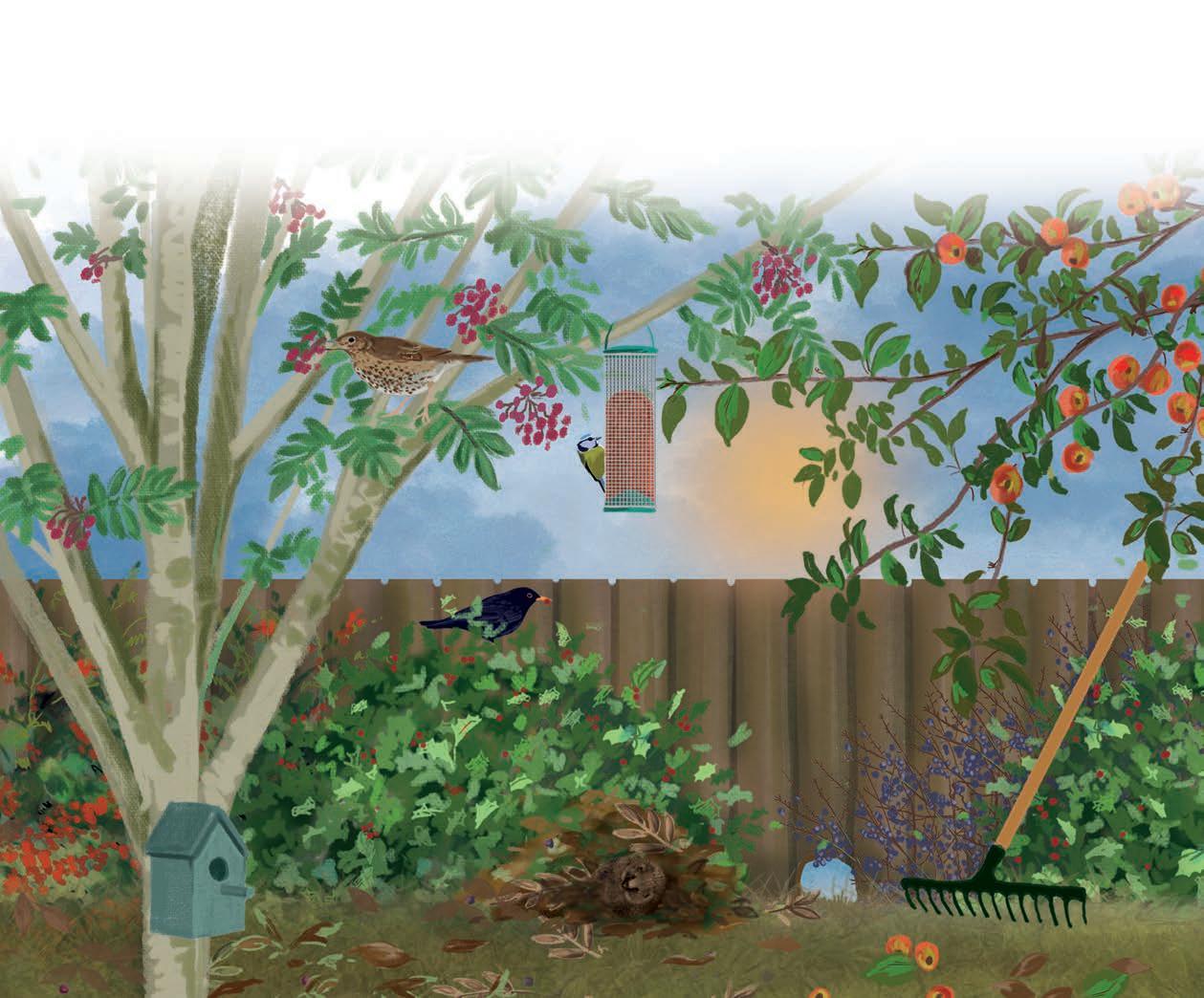

Ecology, conservation and wildlife gardening teacher, Paul Ritchie, shares his most loved garden fruit trees that offer a bounty of flowers, berries and fruits. These eight trees will boost wildlife in any garden, while offering treats for your winter kitchen store.

Fruit trees are fantastic for wildlife and a great way of making space for nature in gardens. Wild fruit trees offer homes for numerous insects at all stages of their lives, nesting birds and small mammals such as bats. Vitally, they also provide year-round food: blossom is nectar for wild bees emerging from hibernation, leaves and the fruit feed moth caterpillars.

Fruit trees in blossom are beautiful but they have a broader benefit for the natural environment and for people too. They improve soil quality, filter the air and slow water run-off which reduces flooding, as well as providing shade in hot weather and lessening noise pollution. I plant native hedgerows to provide wind breaks and shelter for wildlife such as hedgehogs and house sparrows.

You do not need a big garden to grow fruit trees and some smaller varieties will grow happily in pots.

When I am choosing the right tree for the right place, I always consider:

• Height: The mature size should be appropriate for the available space. Especially important if there are buildings, telephone cables or powerlines nearby.

• Shape: The average dimensions of the tree’s canopy spread will affect shading and space so slender trees such as rowan are ideal for smaller gardens.

• Soil: Check the label when buying a tree for its hardiness to drought and preference of soil type to match with your garden e.g. clay, chalky, sandy or loam soils.

I suggest buying trees as bare-root whips to plant in winter, but po ed trees can be planted all year in square holes. Remember that fruit trees can be pruned to suit your own garden and needs.

Paul Ritchie is a biologist, passionate about trees, outdoor learning and connecting people with nature. He has worked for City of London Open Spaces, Surrey Wildlife Trust and now teaches at Royal Botanic Gardens Kew and RHS Garden Wisley.

Rowan (Sorbus aucuparia) or ‘Lady of the Mountains’ produces large clusters of scarlet berries loved by redwing and fieldfare and used as a sugar substitute for diabetics.

Hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna) or ‘Mayflower’ supports hundreds of different insects, and its berries can be used to make ketchup, chutney, jam and beverages.

Crab apple (Malus sylvestris) has small apples loved by hedgehogs, mice, voles, fox and deer and, if cooked, as jelly, chutney, cordial or brewed as cider, is enjoyed by humans too.

Elder (Sambucus nigra) we use the clusters of creamy flowers and black berries to brew cordials, champagne and wine, whilst the berries are loved by thrushes and blackbirds.

For more information and advice on planting fruit trees in your garden, visit www.mycoronationgarden.org

Holly (Ilex aquifolium) has evergreen leaves that are slow to break down, so hedgehogs, small mammals, toads and slow worm hibernate in the leaf li er under the tree.

Wild cherry (Prunus avium) has fruit suitable for making jams, puddings, chutneys, soups, vinegar, cordials, wine and beer.

Blackthorn (Prunus spinosa) is culturally linked with Hallowe’en and, like many wild fruits, sloe berries have medicinal uses as well as being used to flavour gin.

Wild plum (Prunus insititia) or bullace grows in hedgerows and, whilst smaller and less sweet than domestic plums, it can be stewed to make fruit preserves.

“I love being able to watch the fields change so rapidly, not just year on year, but season by season.”

Aggie Thompson, Nature-Based Solutions Officer, leads on the ecological and environmental monitoring programmes for the Trust’s rewilding projects. Here, Aggie talks about monitoring bioindicator species, identifying ecological changes, and managing the Hampshire and Isle of Wight Rewilding Network.

I grew up in Norfolk as part of a family with a love for being outdoors and being in nature. I was lucky enough to visit some beautiful places and see some incredible wildlife, including grey seals at Horsey Gap and swallowtail butterflies at How Hill. We also had many family holidays to the Isle of Wight, so it’s strange how things have come full circle and it’s now somewhere I frequently visit for work.

I’ve always had a love of wildlife and being outdoors, and so the path towards working in conservation seemed a fairly natural route. I’ve always been hugely driven to make the world a better place, and I feel like I’m now able to do my part working towards tackling the ecological and climate crises we are facing.

I first came to Hampshire to study Zoology at the University of Southampton in 2012. After graduating, I started an internship with Southampton City Council which included looking into the effect of artificial lighting systems on bat activity on Southampton Common. After this, I completed my Masters of Research in Wildlife Conservation, which involved an eight-month research project examining the effects of different landscape-scale influences on bats. Other interesting projects I’ve worked on include studying the presence of biological markets in spider monkey social groups in Mexico, and post-release monitoring techniques of extinct-in-thewild species using terrestrial gastropods as a model.

I joined the Trust in 2019, shortly before the launch of our Wilder 2030 Strategy. I have held a few roles within the Trust’s Ecology team, starting as a Trainee Ecologist. In my current role, I focus on rewilding and lead on the ecological and environmental monitoring programmes for our own rewilding sites, Wilder Little Duxmore and Wilder Nunwell, which were acquired between 2020 and 2022. Together, they constitute over 180 hectares of land which has now been reclaimed for nature.

Working on these sites is so rewarding I love being able to watch the fields change so rapidly, not just year on year, but season by season. There is always

something new to see whenever I visit, and it’s incredible to watch the land transforming from uniform arable fields to dynamic landscapes.

I enjoy the data analysis part of the job, assessing the datasets we collect each year to help us understand how the rewilding sites are changing and how we can best support their regeneration.

I also run the Hampshire and Isle of Wight Rewilding Network, a dedicated network for rewilding and regeneration of land for wildlife. The aim is to connect local rewilders and raise the standard of rewilding through shared learning, and to achieve positive results for nature.

I have recently contributed to Rewilding Britain’s Ecological Monitoring Framework which is due to be published soon. It was a rewarding experience to be able to contribute my knowledge and expertise to this important work, which will ultimately increase the quality of rewilding data being collected across the country.

Carrying a quadrat for grasshopper and cricket surveys at Wilder Nunwell.

I will always have a soft spot for bats, they are such charismatic mammals and are often misunderstood. Much of my work with bats has involved using them as landscape indicators, through using acoustic recordings of their calls to measure activity levels and species diversity. These measures assist our understanding of how well a landscape is connected by woodland and hedgerows, and the presence of different bat species also helps to draw implications about what features are present in a landscape.

I am proud to have achieved three different protected species licences These allow me to survey for great crested newts, dormice and bats – all of which are vulnerable to disturbance and habitat change. They are important to monitor and improve habitats, both on our reserves and for projects through our ecological consultancy, Arcadian Ecology and Consulting Ltd.

I feel so fortunate to be able to spend time in beautiful places and to survey so many different, incredible species. One of my favourite places to be is at our rewilding sites, which whilst relatively early on in their progression from arable farmland to natural habitat, provide me with a sense of hope and excitement for their futures.

Standing at the top of West Down, the southernmost point of Wilder Nunwell, provides far-reaching views to the north and to the northern boundary of the reserve, some 2.5km away. You can really see the potential of what the site is going to become with landscape-scale restoration: providing connectivity in the landscape for wildlife. The image of a thriving landscape comprising woodland, scrub, wildflower meadows, wetland, and so much more is an exciting prospect.

I am hugely fortunate to be part of such a fantastic team who are incredibly knowledgeable, passionate and supportive. We also have a great culture of knowledge sharing, and I love working with new colleagues, placement students and volunteers to train them in new survey methods and share my enthusiasm for the fantastic work we do.