Weaving Water, Land, and People

BY ANN ADAMS

BY ANN ADAMS

I’ve been reading Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants by Robin Wall Kimmerer. If you haven’t started reading it, I highly recommend it. As the subtitle suggests, Kimmerer integrates Indigenous stories and culture with her knowledge as an environmental biologist, with her personal experience as a hunter/gather and mother. The result is a delightful and thought-provoking collection of essays that makes connections across so many disciplines it is mind boggling.

Of particular importance to me was her articulation of restorative reciprocity. It was

Root Cause

INSIDE THIS ISSUE

In Practice

a clear articulation of what we as holistic managers are attempting to do. While I have often used the term “symbiotic relationships,” the phrase “restorative reciprocity” seems an even more elegant way to define that relationship as one of reciprocity. This reciprocity is not merely a give and take, but an effort to create greater outcomes for all parties as “medicine for our broken relationship with earth.”

Kimmerer grounds her essays in the understanding that so many of her biology students come to her classes with the clear certainty that humans are bad for the planet. She suggests that such a broken relationship is not a given and has not always been the case. She notes: “As the land becomes impoverished, so too does the scope of [our] vision.” Thus, Braiding Sweetgrass is a book that helps us move past that impoverished vision and engage in whatever restorative reciprocity we are capable of doing as we listen more closely to what the water, land, plants, animals, and people are telling us.

It was with an expansive vision of our ability as humans to engage in restorative reciprocity that the organizing committee for the 2021 REGENERATE Conference decided on the theme for this year’s conference: Weaving Water, Land and People. The Quivira Coalition, the American Grassfed Association, and HMI will co-host this conference which will be both place-based and online to address the needs of our international audience and be responsive to COVID concerns. The conference will weave together field days, workshops, and plenaries—some of which can be attended in person.

Field days will take place in the month of September, while workshops will take place during October, with plenaries taking place the first week in November. Registration will go live in July but we’ll be sending update emails throughout the late spring.

Weaving is part art form and part survival. Every culture has some form of weaving that takes individual threads that become a

whole cloth, serving practical and, potentially, aesthetic purposes. When we as producers choose to engage in restorative reciprocity on the lands we manage, we are weaving those symbiotic relationships that result in more resilient landscapes, businesses, and communities.

We chose three elements for the theme: water, land, and people. Within the elements of water and land, we include all those beings that make up each of those ecosystems as well as the relationships between them. We separated out people to highlight how we, as a species with great power and the receiver of many gifts from nature, must consider our responsibility to use that power in a way that restores and builds reciprocity. At the very least, in our own enlightened self-interest, we must understand that as we impoverish our vision and our practices, we are destined to impoverish our families, businesses, and communities.

So, how can we more consistently come to our work with that concept of restorative reciprocity in the forefront of our mind? How do we share what has worked for us with others so they, too, can achieve the results of improved land health, profitability and sustainable businesses that can be passed to the next generation of producers, keeping working lands working, and developing communities that support this work because the work supports them?

These are the questions we will be exploring during the conference as we work to bring you a diverse group of producers who have learned or are learning how to weave water, land, and people in their production practices, marketing, and land stewardship. We hope you will join us as we all work to create a deeper understanding of what the world could look like if we lived “as if [our] children’s future matter, to take care of the land as if our lives, both material and spiritual, depended on it.”

To purchase Braiding Sweetgrass online, go to: https://milkweed.org/book/braidingsweetgrass.

Healthy Land. Healthy Food. Healthy Lives.® a publication of Holistic Management International JULY / AUGUST 2021 NUMBER 198 WWW.HOLISTICMANAGEMENT.ORG

One of HMI’s testing questions involves identifying the problem you are trying to solve and then determining the root cause of the problem to make sure you are addressing that cause in any decision you are making. Learn what HMI’s Interim Executive Director, Wayne Knight, has to say about the root cause of brush on page 2.

HMI’s mission is to envision and realize healthy, resilient lands and thriving communities by serving people in the practice of Holistic Decision Making & Management.

STAFF

Wayne Knight Interim Executive Director

Ann Adams Education Director

Kathryn Frisch Program Director

Carrie Stearns Director of Communications & Outreach

Stephanie Von Ancken Program Manager

Oris Salazar Program Assistant

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Walter Lynn, Chair

Jim Shelton, Vice-Chair

Breanna Owens, Secretary

Delane Atcitty

Gerardo Bezanilla

Jonathan Cobb

Ariel Greenwood

Colin Nott

Daniel Nuckols

Brad Schmidt

Kelly Sidoryk

Brian Wehlburg

HOLISTIC MANAGEMENT® IN PRACTICE

(ISSN: 1098-8157) is published six times a year by: Holistic Management International 2425 San Pedro Dr. NE, Ste A Albuquerque, NM 87110 505/842-5252, fax: 505/843-7900; email: hmi@holisticmanagement.org.; website: www.holisticmanagement.org

Copyright © 2021

Holistic Management® is a registered trademark of Holistic Management International

Digging Deeper into Root Cause

BY WAYNE KNIGHT

BY WAYNE KNIGHT

In Holistic Management, we aim to think holistically. We endeavor to simultaneously consider profitability, ecological health, and quality of life to create balance in our businesses and lives, now and into the future. We strive at improving the way we make decisions through clarity on short-term needs

Root Cause which asks: “If you are dealing with a problem, does this decision or action deal with the root cause of the problem?”

In our day-to-day lives, we often unwittingly deal with the symptoms of problems, rather than taking the time to discover and deal with the underlying causes. Investing the time in

Courtesy of Betsy Ross, CEO of Sustainable Growth Texas.

and long-term necessity by linking our decisions and actions to these balanced outcomes.

We use a set of testing questions to ensure that we are thinking holistically when we consider important decisions. Realizing that all parts of our lives are interconnected helps bring balance to our thoughts and decisions.

I’d like to dig deeper in the first question—

looking at the root cause could save us so much effort and money not to mention averting the frustration often associated with symptom treatment. An internet search reveals dozens of examples of how to effectively locate the root cause of a problem.

There are obvious examples like pain pills that relieve pain temporarily, while ignoring the

2 IN PRACTICE h July / August 2021 In Practice Healthy Land. Healthy Food. Healthy Lives. a publication of Hollistic Management International FEATURE STORIES Digging Deeper into Root Cause WAYNE KNIGHT 2 Grazing to Feed Soil Life Beyond Under-Utilization and Over-Utilization BETSY ROSS 3 Still Learning after 60 Years JOHN VARIAN 4 Sidonia Beef — Finding Balance on the Farm ANN ADAMS 6 Expense Allocations— Start with the Big Stuff WAYNE KNIGHT 8 LAND & LIVESTOCK C Lazy J Livestock— Improving Land Stewardship & Wildlife Habitat in Montana HEATHER SMITH THOMAS 9 Barney Creek Livestock — Transitioning a Montana Ranch to Regenerative Practices HEATHER SMITH THOMAS 13 Achieving 350% Net Revenue Increase with Beef Cattle — Alejandro Carrillo ANN ADAMS 17 NEWS & NETWORK From the Field / Board Chair 18 Reader’s Forum / Program Round Up 19 Certified Educators 21 Market Place 22 Development Corner 24

root cause—a fracture. Or, perhaps a dead battery may be the result of lights left on or the water level in the battery or a failed alternator because of a worn out fan belt. The root cause here is a routine maintenance failure.

Let’s consider the worldwide “invasive plant” problem. Invasive plant “control” budgets run into millions of dollars annually. Instead of dealing with the symptoms, invasive plants, shouldn’t we be looking for the root cause of the problem— why is brush invading areas where it was not a problem 30–50 years ago?

Before the advent of fences, land ownership, and human population growth, massive herds of wildlife “managed” the grassy plains of our planet. Concentrated in

May 1998

large herds to evade predators and moving to keep their rumens full of nutritious grass, they meandered in large herds.

What has changed since then to produce the explosion of woody plants that we see growing in these former grasslands? In many cases, it has been the result of both overgrazing and over rest that has created more bare ground and the opportunity for tap rooted plants to establish that starts the shift to woody species and weeds.

Key Concepts

• By spending time and effort on correcting the way we manage land and influence soils really does make an impact on the plants that grow there.

• By investing money on improving the underlying causes of invasive plant encroachment, not only can we improve our land and profitability, but the cause of the problem disappears.

• By treating the symptom, we are not investing in what we want, and the problem persists.

September 2019

Grazing to Feed Soil Life— Beyond Under-Utilization and Over-Utilization

An Interview with Betsy Ross, CEO of Sustainable Growth Texas

Q: Is all bare ground bacterially dominated?

A: I question whether all bare ground is bacterially dominated. It depends, of course. How did it come to be bare? What was there before it became bare? The answer, for me, is tied to ‘over- or under-grazed.’ And really, this is really the heart of ‘being a good grazer’ and is why HMI is so very important. It is also related to ‘if left alone, everything returns to a forest.’ The real issue is ‘has the bacteria had a chance to reach homeostasis? (Think of a person eating until all they want, but knowing they need to leave some room for the chocolate cake). Now they eat the cake (fungi). Then they are full and push back from the table, and are satisfied with that part of the meal. Now the fungi get a chance to reach homeostasis. The nourishment needs have been fully met and the bacteria and fungi have worked in tandem to allow the plant to function ecologically—not too much, not too little—not overgrazed, not undergrazed.

If we mess up this grazing function, we throw everything off. If we graze too soon time after time, the fungi run out of carbon and shut down and the bacteria bloom. If we wait too long to graze, the energy from the natural processes (probably photosynthesis processes) retire and there is no constant energy for everyone to be supplied. I think when you undergraze, even with lots of soil organic matter left, the whole system is on idle and takes huge amounts of energy (fuel) to start back up.

The prairie, to me, is the ideal action scene for ‘just right.’ I think the most important thing HMI can teach is how to be a good grazier. Really we could say, teach how to manage your soil biology to keep it alive and well fed.

There is also another piece of this puzzle. If potassium is excessive relative to the other major cations, you are going to have lots of woody weeds. And once again, the ‘over/under grazing’ triggers all sorts of biochemical processes.

When Sustainable Growth Texas heads to the country, we always note how is this land being grazed. And if it is too little or too much, we start looking for one of HMI’s Certified Educators to come help.

That’s my take on it. Not too much, not too little. You can’t eat just chocolate cake.

Number 198 h IN PRACTICE 3

CONTINUED ON PAGE 5

Still Learning after 60 Years

BY JACK VARIAN

My family and I have been cattle ranching in the Diabolo Mountain range of California located midway between Los Angeles and San Francisco and since 1961.

My wife and I married as I finished up my last year at Cal Poly college in 1958. We were both certain that owning land that we could raise a family on and make a living by raising cattle was our goal. With some help from my non-ranching parents I was able to buy a 2700 acre fixer upper ranch, meaning one that was long on brush, rock, fences on the ground, a house that needed

My nonchalance was gone in a heartbeat as I quickly said yes. Those 30 days were an eternity thinking that the sale might fall through when the buyer saw what my country club neighbors called my ranch “Pinch Gut Canyon.” They said it would starve a good man to death. But it didn’t fall out and with $150,000 in my pocket I was off to find our dream ranch.

With my very pregnant wife and our first child sleeping in the back of our station wagon in mid August we explored the high desert region of Northern Nevada, Eastern Oregon and Southern Idaho. Before we left, a friend told me, “If you find yourselves in Idaho take a look at a place called New Meadows.” So we made a point of getting out our Idaho road map as we had just crossed into Idaho. It was about lunch time the next day as we entered New Meadows and Zee

people from your neck of the woods. We may like you and we may not. Second, come here in January when there’s four feet of snow on the ground and you’re feeding hay for six months, unless you happen to have some low country to go to.

Zee and I thanked the gentleman for telling us about the dark side of paradise. Zee said, “We were both born and raised in California and that’s where are hearts and friends are. Why don’t we look where we know the lay of the land?”

We had hardly gotten unpacked when a friend called. “There’s a ranch for sale about 50 miles east of your old brush pile, but this one has more grass than brush.”

We drove what seemed like forever into the Diablo Mountains. Then as we crested the Parkfield Grade we both knew that we were looking at something very special. The realtor had told me, if you look to the east side of the Cholame Valley there are 8,000 acres of mountains that take up most of your view that is the ranch. It was “Love at first sight.”

After three hours bouncing around in the owner’s Jeep I was sure my wife was going to have our second child in the back of his Jeep. But Zee held off for long enough (three weeks) before our second daughter was born. So with my $150,000 dollars and a mortgage for $250,000 with Northwest Mutual Life we escrow.

In 2021 we will have lived here for 60 wonderful years. We are now a tribe of 20 counting husband, wives, children, grandchildren and one great grandchild. 2001 was a momentous year for the family when Zee and I placed a Conservation Easement over the entire ranch of 17,000 acres so that it could never be subdivided. It was our way of thanking this land for giving us a place to live where there has been a lot more love and laughter than gloom and doom over the years.

more than a “spring cleaning” and plenty of Black Tail Deer for $70,000. It was very short on our annual grasses, the predominant feed for cattle here in California.

After three years fixing what I could, I knew that this was not going to work. However, a fellow from Los Angeles was looking for a deer hunting ranch. His realtor approached me and said, “Folks in the area say your ranch for deer hunting is top notch!” I replied, trying to act nonchalant that I would entertain an offer.

A couple of days went by when the doorbell rang. There stood the realtor and buyer. The realtor offered $150,000 all cash, 30 day escrow.

had spied a little café on the Main Street where we hoped we might learn a little about this pretty little town, nestled on the edge of a beautiful meadow surrounded by mountains.

“Do you suppose this is the promised land?” I asked.

Her reply was “I could make a life here with you. It’s certainly more than I have ever dreamed of.”

We were about to leave when an old cowboy introduced himself. “I overheard your conversation and I would like to tell you a little about this country. First he said you’re from California and folks up here aren’t real fond of

We then deeded the ranch to our four children as one indivisible parcel so there would be no arguing over dividing the ranch into individual parcels that none alone would be sustainable. Economically our children wouldn’t be blindsided with onerous inheritance taxes. Zee and I are now tenants renting the grazing rights for our cattle. So what could possibly cause two people of sound mind and body to take such a risk?

Attendance at a Holistic Resource Management seminar and knowing our children was my answer. The year was 1991 and I was on shaky financial ground after experiencing low cattle prices of the 80s with 20% interest rates to start the decade down to 12% by the end of the 1980s had me running scared. However, the

4 IN PRACTICE h July / August 2021

Jack and John Varian riding the V6 Ranch.

seminar turned my fortunes around and sent me in a totally new direction. For the first time I was not just given the permission to think “outside the box” but for me it became a requirement.

The 1990s was a decade of reinventing how to operate our V6 Ranch. Many new ideas now crossed my mind on a regular basis. Once while watching a movie “City Slickers” I whispered to Zee, “We’ve got the horses and the ranch and when it’s necessary to move the cattle why not bring along some guests while we are camped out at Mustang Camp for three days?” For the last 27 years we have four cattle drives per year each with 20 guests. A non-guided hunting club has become our most profitable operation.

In 2000 we examined our hay making program on almost 1,000 acres of our best land. Putting this very erosive practice to the holistic test I found that it failed miserably on every front as I could buy hay cheaper than I could raise it. So as the last piece of hay making equipment exited the ranch, I had an older motor grader left. I took my cutting torch and sold it for scrap.

I came to the ranch, in my youth, full of vim and vigor. Now almost 60 years later the vim my priorities have changed. I now think of myself not as a Cattleman but as a Grass Man first who uses my cattle as a tool to convert grass into cash and improve the rangeland. I still have unanswered questions about my stewardship.

In 2000 I quit dry farming. Three years ago I took 100 acres out of what had been 1,000 acres of dry farming ground and planted it to pistachio trees in the name of diversity. Lastly, my son-in-law who is a cattle buyer also runs his own stocker operation. Two years ago he convinced me to buy all my stockers on video from ranches

Digging Deeper into Root Cause

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 3

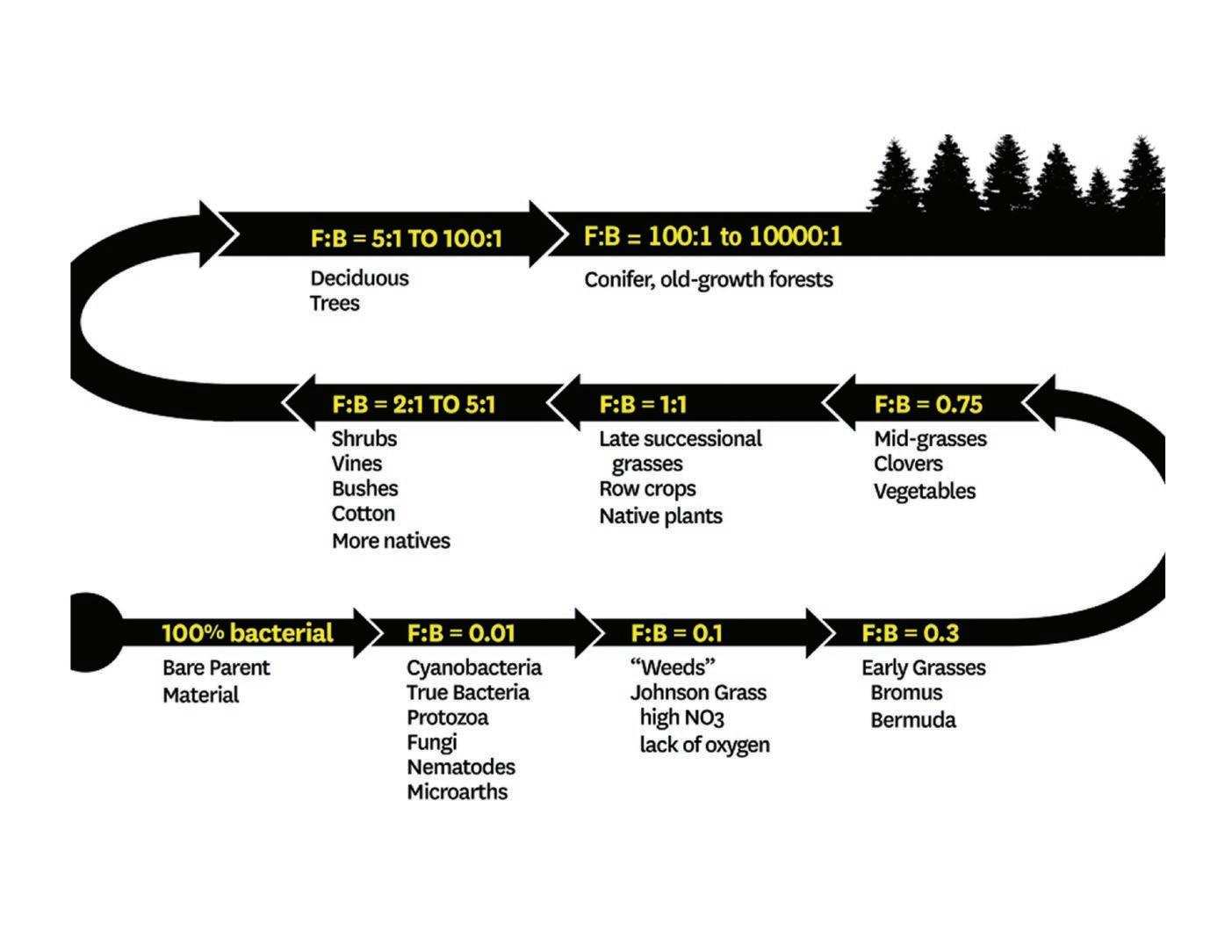

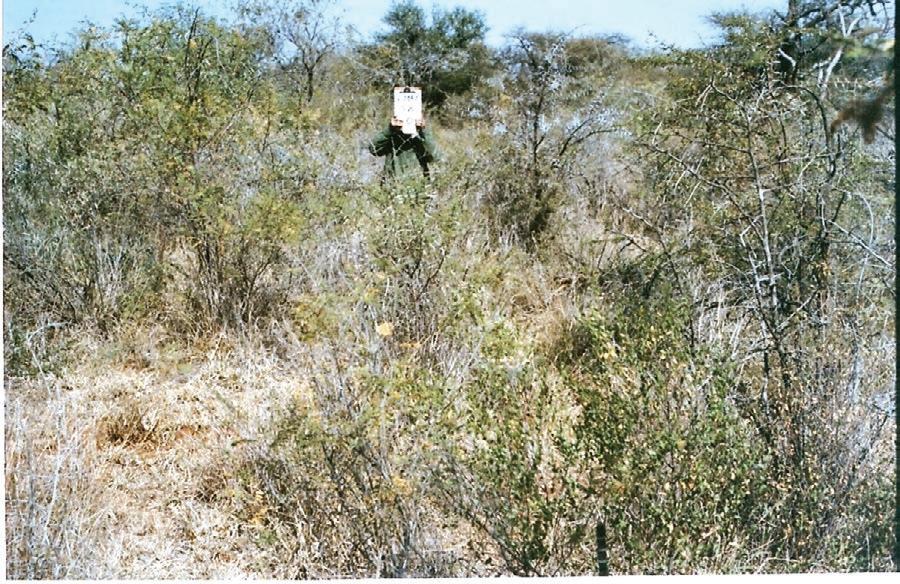

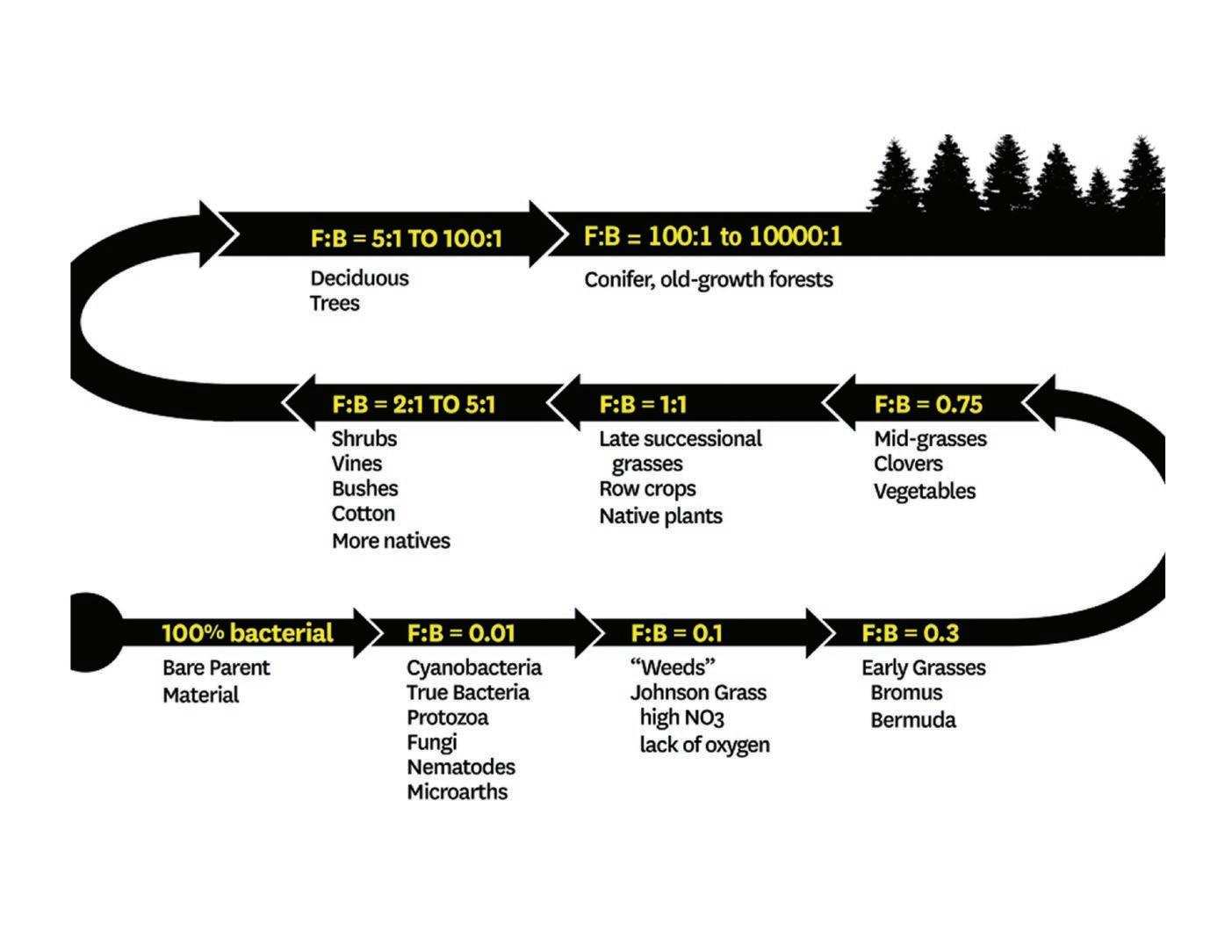

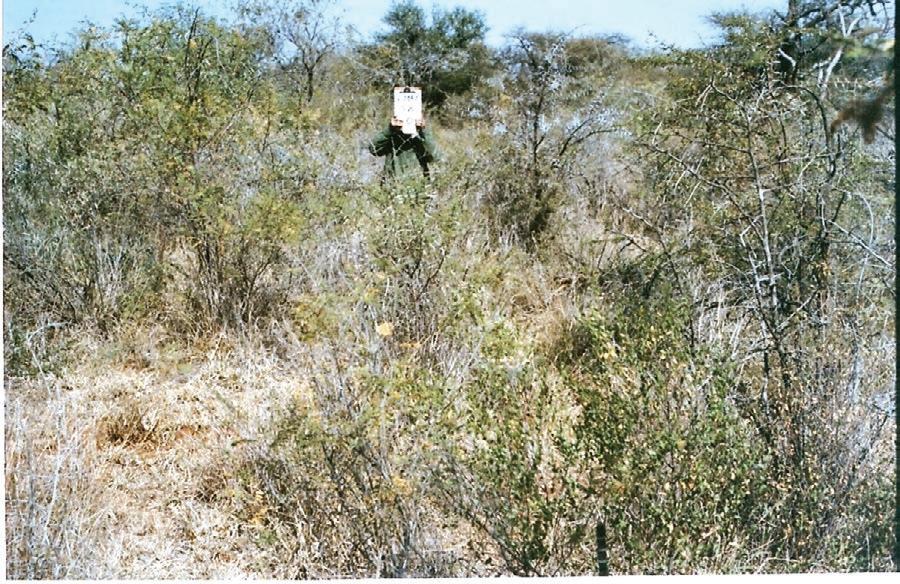

But, we also know that changes in soil microbiological balances will favor one plant type over another. Fungal dominated soils may favor the germination of woody plant species. Soils with relatively more bacteria may favor the germination and growth of lower-successional grasses and annuals. As you can see from the pictures on page three, with good management (in this case planned grazing), you can shift the successional process to reverse the movement toward woody species and actually change the environment in which they are growing, resulting in a reduction of woody plants and flourishing grass plants. In both pictures, planned grazing was the only tool used that resulted in the death of what was once flourishing brush.

in the high desert of Nevada, Eastern Oregon and Southern Idaho and stay away from the sale barns, and that means a lot less stress and less problems with pneumonia weaning some calves that don’t sell as well.

Now I’m into my second year of Mike video buying for me only good high desert steers weighing 550 to 650 that have been weaned 30 days, and have had the two shot series for pneumonia prevention and where they were born and delivered from the same ranch. Delivery is mid-October to mid-December. They arrive after a 12 to 18-hour haul and usually in the middle of the night. I unload them into a bull strong pen with hay bunks full of grain hay, which is the only hay that they will receive while here on the ranch. They are allowed to rest that day and the next morning, first thing, we process them.

One shot I find to be advantageous is Enforce that gives a boost to the immune system. They are then driven about a mile to a pasture of about 400 acres in size and after watching them for any sign of sickness for a few days they get turned out to the mountain pastures were they will stay until the following June. There they will find plenty of dry annual grass that’s a bit better than straw but with 28% protein tubs available they do quite well while they await the start of a new grass season, which starts the first of November and ends the fifteenth day of June. This is the opposite of the rest of the USA.

I expect my 1,000 head of stockers to gain 300 pounds. Except for a few bad eyes I have had not one sick or dead in two years. For me that’s unheard of as I usually figure 1 to 2% death loss as acceptable and doctoring 3 to 5% as acceptable.

I am a firm believer now that feeding hay is a loser but I do need my cattle to spend most days gaining weight without feeding hay. Here comes the question. I have been using a commercial nitrogen fertilizer on my ex farming ground that after 80 years of dry farming is absent of most of its nitrogen. The results have been dazzling to say the least. An increase in production of three or four times and a quick green up with the first rain, so my cattle now get a mouth full of grass a month to two months earlier than not using fertilizer. I read the Stockman Grass Farmer with a little jealousy for the things that you can do perennial pastures. How to restore them to their former productivity without the need for any fertilizer that comes in a bag?

I end by answering my own question. I don’t want to run out of years before my soil runs out of nitrogen. To the purest of our holistic community, I think they would call this, a hold your nose sacrifice, where my footprint is still much too big, but I’ve heard no answer as how to fix it. But I believe, what I’m doing sure helps pay the bills and no hay is needed. Hopefully there’s some reader of the Stockman Grass Farmer out there who might have a different solution for me to ponder.

John Varian can be reached at Jovv6ranch@gmail.com

Reprinted from The Stockman Grass Farmer Magazine. Call 800-748-9808 or email sgfsample@aol.com to receive a free Sample Edition.

Share your response to Jack with us as well so we can print your answer.

Email: anna@holisticmanagement.org.

So what is the root cause of invasive plant growth? Does treating the invasive plants using chemicals or mechanical means effectively deal with the root cause of the problem? We know the answer! Again and again, after posttreatment we see more seedlings germinating than before the treatment was done. The root cause has not been dealt with!

An improved approach should be to discover the human management that needs to change in order to recreate the soil conditions that originally produced thriving, diverse grasslands. My personal experience is that changing the management will alter the soil condition enough that the problem plant is no longer a problem. It dies and is not replaced by more woody plants.

Instead, perennial grasses flourish.

The photos on page three show the same spot 21 years apart. There is brush in both photos. The first photo shows thorny young trees and lots of grey old material on the ground—under-utilization. The second photo shows much better grass utilization and dying brush. Note the color difference of the grass between the photos. The yellow or gold color in the second photo shows better nutrition— indicating a healthy mineral cycle. The only tool used was Holistic Planned Grazing—simply using animal density and timing of exposure to animals improved soil conditions. Fire and chemicals were not applied.

Number 198 h IN PRACTICE 5

Sidonia Beef— Finding Balance on the Farm

BY ANN ADAMS

Sam White is the sixth generation to farm Sidonia Hills, a 2,000-acre farm north of Kyneton, in Victoria, Australia. He and his wife, Miranda, are busy developing Sidonia Beef as a paddock to plate business that supplies the local customers, restaurants, and butchers with grassfed beef while managing the family farm. While Sam runs Black Angus cattle on 1,500 acres, Sam’s father, Frank, runs 350 sheep on 400 acres.

Sam’s journey as a grassfed farmer began in earnest in 2005 when he made a commitment to farming, returning full-time in 2009. He and his father also began farming organically in 2005, but in 2015 he took a Holistic Management course with HMI Certified Educator Brian Wehlburg that changed his life.

The Regenerative Journey

While Sam has always loved the farm, it was only in the last 15 years that he became engaged in the management of it. During that time, various family members have been involved, but Sam and Miranda have now stepped into the full management of the beef operation.

“In 1921, my grandparents bought this place,” says Sam. “I’ve always loved the farm since I was a little kid. We grew up in the town

The office job/city life wasn’t for me at all. I knew I was a country person.

“Everybody else (including five siblings) has gone off farm and have other jobs. They don’t make day to day decisions, but they have input. They are interested and supportive, but I need to make the decisions. I’ve used our management group to help me with decision-making. My sister was doing the marketing for a while, but she’s gone over to another job, so my wife and I bought the business.

“We live on the farm and lease the land from my dad. We were leasing the cattle from him before. He’s also supportive but isn’t involved in the daily activities. When we were trying to figure out how to make the transition my dad and I came up with a figure for the value of the cattle. We decided I would lease the cows from my father, but all the offspring were mine. We just negotiated the rates by looking up lease rates in the dairy industry which ended up being $50/cow/year. We also pay anything that needs to happen with the cattle like vet bills. We take care of it all. If an animal doesn’t look quite right, it’s sold and the income goes to my dad. The land lease was negotiated the same way as we looked at similar rates and did a family rate that was a bit under the going rate. My dad is in his 80s and lives on the farm so it’s worked out for everyone.

management with the sheep. Right now I have only cattle on my leased land. My dad has some acreage around his house where the sheep are

with Dad and my brothers. I did part-time work in Melbourne for a while, but in 2009 I became full-time on the farm as Dad needed more help.

“The succession planning started 15 years ago between all of us kids. We all know where the succession is going. Everyone’s got a piece of land in the future, but I can lease it or share the farm. One of my brothers is particularly interested in sheep so we may possibly do multi-species grazing. We currently run 350 merino sheep and we are working on plan to integrate the cattle in the grazing

run and he is in charge of the sheep. Over the years he’s seen some of the benefits of the long recovery I’ve given the land with my grazing so he’s taken that on board and the grazing is improving with the sheep.

A New Chapter

When asked how the Holistic Management training they received from HMI Certified Educator Brian Wehlburg has influenced him, Sam says, “It literally changed our lives. He introduced to me a way of farming and a new way of thinking. The way he delivers his course and teaches is just inspiring. We took the 8-day training in 2015 in Victoria after I came across the Inside Outside website. My aha moment was the realization I was running so many mobs on our farms and just realized how complex I was making it, and yet how simple it could be if we managed one herd. With that our farm would have more paddocks and more recovery time. I was very much on the grazing side of the course, but then I learned about the financial and social parts and realized it’s about everything. I did a diploma in organic agriculture in 2009 and I started down the organic path so I was already looking down the alternative path. In the 2015 Holistic Management course I met new people. We have a support group going now thanks to Brian and Gill Sanbrook. It’s been going since 2015 with a core group of 12 participants. I’ve also done the course a couple of times as a refresher.”

“I had heard about Holistic Management in 2013. One of the local couple had an Open Gate day on their farm and I got to see the results on their farm. I also did a course with Colin Seis in 2012 looking a pasture cropping. Colin said

6 IN PRACTICE h July / August 2021

The Whites continue to grow their direct market for their animals.

Holistic Management training session with HMI Certified Educator Brian Wehlburg.

this land was not really cropping country so it was not a good idea to try the pasture cropping here. I also went to Graeme Hand’s course, he was talking about when to tell that a plant had recovered and when it’s ready to be grazed as well as how to make sure you have good litter.

“With Brian I first learned about grazing planning and how to do the full planning. I’ve continued to do that. I used to do the full moving of the wires every day. I put 10 mobs into one mob of 500 animals. I just opened the gate and they’d move through. In 2016–2018 I was running 500 cattle of all different ages from different mobs. It was really a learning curve to run such a big mob. I had to figure out how to manage animal husbandry and how to get an excited mob moving through a small gate. Basically I would sneak down and open the gate and then drive through the mob on my bike and dribble them through. I found the bike was a pretty powerful tool. They learned that was their wake up call and that they were going to be moved. If I didn’t want them in a certain area, I would just take them to another area. I was really inspired by Temple Grandin as I watched her videos.

While Sam has run as much as 500 cattle in one mob, the average number he runs is

that infrastructure development is increased productivity with next to no input costs. Our profits are much better than they ever were. Now we can fence water points to allow more grass to grow and provide longer recovery, so we can potentially double the herd. We’ve been able to increase stock density by doing some temporary fencing at certain times of the year.

“We are looking at animal days per acre, but we are monitoring daily on how the best plant in the paddock is performing. I monitor for when the cattle have taken the bite out of that plant and I know it’s enough. Then I take them out if they have taken more

were running less than we had been but the land recovered most of 2019. We put the cattle back on in November 2019 after six months of recovery. We had been leaving reserves and

to 60 over a three-year period. They also developed some gravity-fed water infrastructure with more to do. “We’ve been able to pay for the infrastructure development on the part we own through the profit we’ve earned through our sales,” says Sam. “The results of

With improved grazing and kelp and apple cider vinegar supplements (but no free choice supplements),the Whites are seeing their steers put on 1–2 pounds of gain a day with 100% breeding rates with their cows.

paddock one to three days. Our recovery periods are 120 days in the non-growing season and down to 40–60 days during the growing season, depending on how well the season is going. Our paddock sizes range from 10–180 acres with an average of 25–30 acres.

“In 2019 we had no rain from January through May. Our average rain is 630 mm (25 inches), but in 2019 we only had 300 mm (12 inches) with a dry winter and rains beginning in May. We made the tough decision to sell 90% of the cattle because we were running out of feed. The grazing plan got me through that decision. It was the best thing for us. We sold our calves and we used that to buy a new herd of cattle. In 2020 we

litter and we saw how quickly the land recovered, especially compared to neighbors. They were feeding through the winter and spring and they had to feed 3-4 months more before they got their production going. So we were able to buy and agist cattle from November through the end of March. We had grass when most of Australia didn’t have grass. We bought 50 cows/calves and 75 steers plus we ran 80 cows for contract.” It was through their holistic grazing that they could run any animals at all without input and have hopes of building back up to their average numbers of animals soon.

Sam monitors progress on the land in a variety of ways. “In 2015 we did some monitoring with Brian,” says Sam. “We had a fair percentage of bare ground, approximately 50% bare ground between perennial plant. So I focused my grazing on those areas and now we only have 20% bare ground and we have more diversity. A lot of original native plants have come back and we’ve sown some perennial plants. A lot of the annuals we had are now gone like capeweed and stork’s bill geranium. Now we have more wallaby grass, kangaroo grass, red native grass, and microlaena, which is like Lucerne. Gill Sanbrook said, ‘If you see that come back you are doing something right.’

Number 198 h IN PRACTICE 7

CONTINUED ON PAGE 8

Part of the White’s succession plan was to have Sam lease his father’s cattle with the understanding that all calves would be Sam’s.

“I don’t do formal soil testing as I am a visual person. I look around and get feedback from my observations. The animals are looking healthy and happy. I look at their behavior, temperament, and coats. In 2005 we had some vet bills and then we turned off the tap to all chemicals for the animals and the farm. I got into Pat Colby’s mineral supplements. We drench with cod liver oil, and give kelp and apple cider vinegar. We struggled at first as we got our grazing right. The cattle did go backwards at first for a generation as we had more illness and death and a drop in animal performance. They didn’t have the immunity and we saw in the drop in weight gains and non-calvers.

“Then things started to improve. We are not doing any free choice supplement and we are putting on .5–1 kg/day (1–2 pounds/day) on the steers as well as getting 100% with our breeding. We continue to improve the herd genetics with each purchase. The cows had needed to be sold because they were getting old so we got some Te Mania genetics. They produce good calves and have good temperaments. They are Angus with a mid-size frame, and a finish weight around 330 kg (728 pounds).

Sam also monitors the land’s ability to stay in place despite the sudden storms that can happen. “We used to have a lot of topsoil

Expense Allocations— Start with the Big Stuff

BY WAYNE KNIGHT

For any business keeping costs low is a critical management function. For an agricultural business, this is especially important. At HMI, we recommend analyzing costs based on a reallocation of your expenses list.

Consider dividing your costs into the following categories because not all expenses are equal:

• Top Priority Investments (also known as wealth-generating expenses)

• Inescapable expenses (liabilities, contractual agreements, taxes, etc)

• Maintenance expenses

This cost allocation assumes you are clear on which enterprise contributes to covering most of the overheads of your business. It

erosion,” says Sam. “We can have storms that are two inches in an hour. Before, when we had the sheep hanging out on the top of the hills and then the rains would come, the soil would run down the hill and knock down the fences. Now, when we have those rain events, the soil doesn’t move because it’s covered. We had Brian and the management group come out to those hills and they couldn’t believe how much grass there was and that we had 100% ground cover.”

The Whites are currently working to get more of their beef in the local market. Like many producers they were inundated with interest in their product because of COVID. The demand for their product doubled and the local slaughterhouse that is just 15 minutes down the road could accommodate them. They currently are selling 100 beeves a year with about 20% going to the local market. Once their cattle are processed, they dry age the beef for a minimum of 14 days.

“We have a growing marketing list for our grassfed beef,” says Sam. “We do events like Lost Trade Fairs where there are 20,000 people. We cook burgers as a lunch option and then promote our seasonal beef boxes. We do a couple of those events each year and spread our message on our farming.”

Sam says the greatest challenge in this style of farming is to determine the appropriate balance among the people, plants, and animals.

“I try to get that right balance between growing

enough grass and getting production from the animals without taking too much from the farm,” says Sam. “For example, we have bentgrass that is difficult to manage and is a headache. It’s an introduced, perennial, sod grass that has no nutrient value for stock and doesn’t allow any other plant to grow near it. We had high density stocking on it to tear it, but we can’t totally get rid of it. We have been able to knock it back with high intensity grazing then long recovery. Usually a forb species will come to take its place then over a two-year period we will get some perennial grass. If you come back too soon or stay too long, then you change the dynamic and switch the land back to bentgrass.”

But, Sam is learning how the land responds and what the animals need. With improved infrastructure comes improved grazing and improved ecosystem function, increased biodiversity, land productivity and resilience, and profitability from a low-input system. While there will be droughts, fires, and other challenges, the system that Sam has created has helped him weather these challenges and participate in a successful farm transfer.

“Our holistic context says we want to increase biodiversity,” says Sam. “We want good functioning soil, healthy animals, and kids and family to enjoy the farm. We are the artists painting the picture and the land is our product and we improve it for the future. Holistic Management is a tool to get you there.”

also assumes you have considered risk in enterprise selection.

Wealth-generating expenses are those that will add to your ability to generate wealth (profit in monetary or land health terms). These include investments in things like water infrastructure to achieve your grazing and herd expansion goals or a hoop house for season extension.

Inescapable expenses are the expenses you are legally or morally obligated to pay.

Maintenance expenses are those expenses that maintain your production level where they are. These expenses are anything that doesn’t fall into the first two categories of top priority investment or inescapable. Hay expenses might be a way to reduce risk, a way to maintain the production of your animals, and an expensive habit. Or it could be a way to improve soil fertility if fed out in the field as bale grazing. Being clear about what the expense is for and if it is really needed will help you free up money for investing in expenses that will address an operation-wide logjam or a weak

link within a key enterprise that can take your farm or ranch to the next level.

Are there maintenance expenses you can simply eliminate from the budget through improved management practices?

Look hard at maintenance expenses. Don’t cut these if that will lead to a drop in profitability. Are they really maintenance expenses? In an animal-based operation, this may include genetics expenses, feed expenses, or forage growing expenses. Holistic Management’s Financial Weak Link test and Comparing Options tests would be very useful in helping you decide where these expenses fit in your current production situation.

When allocating time to spend on cost reduction and category allocation, spend the most time on the big-ticket items. Spend the most time where you will get the most return on your time. Don’t sweat the small stuff—the insignificant expenses in the budget. By spending more time on the biggest expense items you will be getting the biggest bang for your buck.

8 Land & Livestock h July / August 2021

Sidonia Beef CONTINUED FROM PAGE 7

& LIVESTOCK

C Lazy J Livestock— Improving Land Stewardship & Wildlife Habitat in Montana

BY HEATHER SMITH THOMAS

BY HEATHER SMITH THOMAS

Craig and Conni French own C Lazy J Livestock near Malta, Montana, and were the 2020 recipients of the Montana Leopold Conservation Award for their conservation efforts. They have been ranching together since 1991, starting out on a ranch that was homesteaded by Craig’s great grandfather in 1910.

“We met in college, at Bozeman, Montana and after we got married we worked at a private guest ranch just outside Yellowstone Park for a couple years, and started a family,” Conni says. “Then Craig’s parents were expanding their ranch and wondered if we’d like to come back to the ranch, and we were excited about that opportunity. We worked with his mom and dad for 25 years.

“Then we were able to purchase a place of our own—a ranch on the northern border of his parents’ place that came up for sale. So we just added our property into the management plan of the whole ranch and we ran our cattle in common.”

Then, about three years ago Craig’s parents started doing estate planning and other family members decided they wanted to come back and try their hand at ranching. “We decided this was the opportunity to do our own thing and pursue some of our own ideas. It’s not always easy, in a family situation, because a person always has to compromise and it can be challenging. Making the decision to go our own way gave us a little more freedom,” Conni says.

“We thought we’d let them follow their dreams and we would follow our dreams and it’s been a wonderful thing. It was one of the hardest decisions we’ve ever made in our lives, but one of the best.”

A Land Stewardship Education

When Craig and Conni were thinking about how they wanted to manage their place, they thought that their son Tyler would like to eventually ranch with them. He is an Air Force pilot and was deployed to

Afghanistan. “While he was there he had a revelation, and realized he really would rather be ranching because that’s where his heart is,” says Conni. “He had some free time now and then, and asked us to gather some good books on ranching and land stewardship and send them to him. So we started asking around, to find some books for him.”

They had several neighbors who recommended books, and one of those books was Allan Savory’s book on Holistic Management. “We sent the books to Tyler in Afghanistan and he read them and got fired up—and sent them back to us and insisted we read them, too. He pushed us and that’s what we needed,” Conni says.

They had also attended a one-day NRCS grazing workshop that had been held in their area. “Craig and I attended, and this was a lightbulb moment for us, listening to that speaker,” says Conni. “We realized that we had not been doing the best we could do, for our land, and knew that we could improve.” She and Craig had always considered themselves good land stewards, but now realized that their ranch’s future was tied to healthy soils and grass. This introduction to Holistic Management called into question some of their long-held, traditional ways of thinking.

“We’ve learned more now and can adopt some of these ideas that were earlier not as widespread,” says Conn. “This got us started and we realized we needed more education.

“At that time we were still ranching with Craig’s parents and running the yearling herd on the main ranch,” says Conni. “We started using electric fence and trying to intensify grazing management, and had some nice success. This motivated us even farther.” This allowed more recovery time for perennial vegetation to flourish in this semi-arid environment of short prairie grass, resulting in better forage and wildlife habitat.

When the time came for them to make the decision to leave Craig’s parents’ ranch and start out on their own, they had the courage and confidence to do it because of the continuing education they had engaged in. “We also feel that it was a God thing,” says Conni. “We realized there were certain things that we needed, that had to happen, for us to be able to make it on our own, and uncannily it all fell into place, like it was meant to be.

“This also gave us confidence that we were on the right road, and thinking there was a reason for this—that maybe we were meant to do it

Number 198 h Land & Livestock 9

CONTINUED ON PAGE 10

Craig and Conni French

Photo Credit: Isaac Miller

C Lazy J Livestock

so we could help other people; maybe we could set an example for other people to have the courage to try this road, and that maybe this is how we are supposed to take care of this land.”

Working with Nature

When Craig and Conni started ranching with his parents, they bought cattle from them, and some cattle from neighbors—some older, short-term cows—and built their herd slowly. When they moved to their own place they started more intensive grazing management and brought those cows along. They didn’t make a huge shift in calving date, but gradually backed it off to later calving.

They quit pouring the cattle with chemicals, and monitored the cows closely. There have been some fall out of the program because they didn’t adapt to the change but most of them have done fairly well.

The cow herd is basically Black Angus, but Conni and Craig started buying bulls from folks who are raising grass-based cattle, trying to work toward a more efficient herd. “We’ve been doing that for many years, even before we started doing what we are doing now,” says Conni. “We wanted to work toward a smaller animal that does better on grass, and have always been a proponent of letting Nature do the genetic selection. We calve our cattle out on range pastures; we’ve done that for many years.”

For replacement heifer selection, at first they sorted off and sold the smallest ones, but now they keep all their heifer calves and let them sort themselves. The ones that do fine are the ones they keep. “We don’t worry about what they look like, as long as they do the job they are meant to do,” says Conni.

For grazing management, the Frenches try to graze one-third, leave one-third, and trample one-third, and keep the cattle moving frequently— especially the yearlings. “They usually don’t spend more than three days in any one paddock, particularly during the peak of the growing season, and we prefer to move them every day,” Conni says. “Life sometimes gets in the way, however, and we have things to do and don’t always get that accomplished. A person has to be flexible, but we do the best we can and realize we are just scratching the surface and have much more to learn, and know that we can get better at this. There are so many folks out there doing inspiring things, and we’d like to get to that point someday.”

A Commitment to Conservation

While the Frenches may think there is much more they could be doing, their management practices have resulted in improved wildlife habitat. For example, they have replaced some of the permanent fence with temporary electric fence to reduce conflicts with wildlife. In addition, they use targeted grazing of non-native grasses to improve habitat for grassland birds and sage grouse.

Also, with assistance from the NRCS’s Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP), they moved livestock water tanks and windbreaks away from Beaver Creek, a stream that flows through three miles of the ranch. The return of willow trees along the creek is a sign their efforts are paying off.

Craig and Conni collaborate with federal and state agencies, non-profit groups, and other ranchers to achieve conservation goals. A few years ago they began a voluntary 30-year conservation lease with Montana’s

Fish, Wildlife, and Parks to ensure that their ranch’s native grassland and sagebrush will remain uncultivated and undeveloped. They also work with the Nature Conservancy, and agreed to sustain and improve habitat for four species of imperiled grassland birds and sage-grouse, and have their numbers surveyed, as part of the CCAA (Candidate Conservation Agreement with Assurances) program, administered by the Nature Conservancy in Phillips County.

They also work with Ranchers Stewardship Alliance (RSA), which is a community conservation group. As long-time members of this rancher-led conservation group that helps educate folks within and outside the ranch community, they share their experience with Holistic Management, cell grazing and other innovative conservation practices.

“We formed a conservation committee and have folks on that committee from NFWF (National Fish and Wildlife Foundation) partners program, Ducks Unlimited, Fish, Wildlife and Parks, BLM (Bureau of Land Management), NRCS, National Wildlife Federation, WWF (World Wildlife Fund), TNC (The Nature Conservancy), etc.,” says Conni. “Many different groups sit down at the table together and go over the projects that some of the other members of the conservation committee have brought to the table; we look at maps, budgets, etc.”

Many of the biologists in the area, and folks working for the partners’ program and the NRCS have contacts with landowners. “They come up with projects the landowners want to work on, to improve their grazing and maybe need some fences or waterlines or wells—or some reseeding,” explains Conni. “It might be folks from the NRCS, NFWF, BLM or Fish Wildlife and Parks who identify the landowners’ needs and bring these proposed projects to the table, or they’ll see a need from the conservation side, and approach the landowners.

“Right now they are working on some big game migration corridors, for instance, and talk with landowners to see if they can modify the fences or help them do that. It might be a reseeding project, water development, or fencing. Our conservation committee looks at the projects and ranks them, and tries to fund them. Then all these organizations that have various conservation programs look at those projects to see if they might be able to participate.”

Fish and Wildlife might have some money that would buy water tanks to help with a certain project, or supply some funding. The BLM representative might say they could help with some fencing modification for big game movements and could supply some money for that. It’s a great partnership and team effort.

“It’s gratifying to see all these people—and a lot of them young people—coming together and working together, leaving their egos at the door (nobody has to be the leader of a certain project)” says Conni. “We have accomplished a lot and have brought over a million dollars into this area to help landowners with infrastructure and seeding to improve their grazing and practice conservation at the same time. This has been an exciting thing to be a part of. We are also very interested in making sure

10 Land & Livestock h July / August 2021

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 9

The yearling herd enjoying the improved forage on the French Ranch.

Photo Credit: Isaac Miller

that good conservation and land stewardship is practiced, as well.

“Through this RSA we were able to put in some permanent electric fence on some expired CRP ground on our ranch (an old crested wheat seeding) and some pipeline and water tanks to help intensify our grazing. Off that permanent electric fence we can run temporary electric fence to strip graze (dividing the pastures into smaller pieces) to really intensify the grazing.”

A Yearling Herd

The Frenches have also experimented with creating a larger yearling herd through collaborating with their neighbors. “We were able to bring in extra yearlings and do some custom grazing this summer, with some yearling heifers,” says Conni. “We got this idea from a program called a grass bank, at the Matador Ranch west of us, owned by the Nature Conservancy. They bring cattle from different ranches and run them all together in larger herds (three separate herds). This creates more animal impact where they want it. A person can do things with a larger herd that you can’t do with just a few cattle, when managing grassland.

“What we are trying to do is not exactly the same, but this is where we got our inspiration to bring in more yearlings to custom graze. Having the larger herd created more animal impact and got some of that old crested wheat knocked down. We don’t want to eradicate it, but are hoping to get more plant diversity and healthier crested wheat plants themselves, since it is a very old and decadent stand that needs to be refreshed.

“Bringing in more yearlings was fun; we sourced them from neighbors who each keep a few yearling heifers. There might be a herd of 30 on one ranch and 75 on another, and 40 on another place, etc. Being able to put them all together as one herd made it easier to use that herd as a tool to manage the resource.

“We actually took the yearlings off our property and onto other properties, as well—to places where people needed more animal impact for a while. One neighbor was having a hard time making his cattle use one end of his pasture, so we took our yearlings in there and they did a nice job of knocking down some of that old grass and refreshing his pasture. That was a great project and we are hoping to continue doing that next year, to help other ranchers in our community.”

Craig and Conni have also used this yearling herd to improve old hay meadows. “We run on a combination of BLM, state land and private ground,” explains Conni. “Beaver Creek is one of the main drainages in our area and it goes through three miles of our place. There are many hay meadows along the creek, but we’ve quit haying and now just graze our hay meadows. That has been an amazing change. With our hay meadows being along the creek, much of the creek bank never got grazed much. We sometimes turned the cattle in there in the winter but couldn’t do that very often because the creek was dangerous for the cattle that time of year, but we got some use out of it.

“Now that we’ve quit haying, we have more plant diversity, which has

helped the grazing and our cattle numbers. It has been really good for the grass. One of the first times we brought extra yearlings in, we wanted to have them graze our old hay meadows early. We watched closely and made sure the grass was at a 3 to 3 ½ leaf stage and then turned the yearlings in; we went through the grass quickly with those cattle and just took the top third and moved them out. We were able to get some irrigation water on those meadows and then come back later in the summer (in July) with cow-calf pairs. Some of the smooth brome plants that were just little 3 to 3 ½ leaf plants when we grazed them the first time were amazing when we came back 45 to 60 days later. Those plants had 12 leaves on them. It was amazing!

“We are seeing healthier plants and we took photos in August 2020 when we turned our cowcalf pairs into some of the hay meadows that we’d gone over quickly with the yearlings earlier. Our region was pretty dry in 2020 and had a major grasshopper problem. I have photos of when we turned the cattle into those hay meadows and it is green and lush and hard to walk through because there is so much grass. I thought, this is what intensive grazing management can do!

“In talking to some other folks, they were saying that the healthier green plants, with a higher sugar level, are avoided by grasshoppers. The grasshoppers have a harder time digesting the sugars, according to those folks. So this is something we want to look into more fully. If we can do a better job of managing our grasses, maybe we can protect our grasslands from these insect predators that can decimate these grasslands during a drought. Some people were saying the grasshoppers were eating their pastures, and we were pleasantly surprised to see that ours were healthy.”

Riparian Restoration

Conni and Craig have also tried to protect and improve the riparian areas along Beaver Creek. The cattle are watered in tanks, using a solar pump to pump water up out of the creek, to try to keep the cattle off the riparian areas as much as possible. “But another thing we found, when pasturing cattle here along the creek for short periods of time, was that this grazing was actually beneficial,” says Conni. “Those areas also need

CONTINUED ON PAGE 12

Number 198 h Land & Livestock 11

Photo Credit: Isaac Miller

To protect the riparian area along Beaver Creek, the Frenches use a solar pump to pump water into stock tanks away from the edge of the creek.

Photo Credit: Isaac Miller

C Lazy J Livestock

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 11

grazed, and the cattle find places where they can get down the bank to water in the creek.”

Beaver Creek and many of the other creeks in this area have steep banks, where the water has eroded the fragile soils, making a cut bank. “But the cattle have found places to get down, and have created trails that break down the bank and make it less steep,” Conni explains. “Where the cattle are in there only for a short time and then leave, we are seeing those trails they’ve created down to the creek fill in with weeds and marsh grasses. The cattle have actually helped create an area for the bank to heal and have vegetation holding the soil again, and now the wildlife are using those trails also as access points, to get in and out of the creek for water. We have an increase in predator bugs like dragonflies, and we have more dung beetles. It has a snowball effect, when you help the environment in one area it improves other facets and everything starts to recover.”

Sharing Knowledge & Experience

In the near future, Craig and Conni plan to use 320 acres of recently purchased farmland as a demonstration site for the soil health benefits of cover crops. Healthier soil and more species diversity also improves wildlife habitat and there is a lot more wildlife diversity on their entire ranch now, including more game animals. Hunters are allowed access to their ranch’s thriving wildlife populations through enrollment in the state’s Block Management program.

“We hunted for many years ourselves, and our kids did,” explains Conni. “We don’t hunt anymore, but I grew up hunting in western Montana with my family. We came to eastern Montana to hunt, on occasion, and I remember what a great thing it was for my family and for me.”

Allowing hunters to come to the ranch has been interesting for the Frenches, meeting people from all over the U.S. and from other countries. “They talk about the lack of hunting opportunities in other countries and we realize we don’t ever want to see hunting become just a rich man’s sport in our country, so we are as open as we possibly can—providing opportunity for people to come here and hunt,” says Conni.

“We feel we are incredibly blessed, to be able to live here and do what we do, and this is a way of sharing this with other people. This is part of the responsibility of our blessings—to share them.

“Agriculture gets a lot of bad press and if people never get out on a ranch, they have no way to really know what it is like. If we can bring people onto the ranch, whether through hunting, kayaking, bird-watching, etc. and open our doors so people can see what we are doing, then they have more actual knowledge and won’t believe every bad article they read in the press about agriculture.”

Craig notes that in caring for the land for many species, they have also improved their ability to be profitable in production agriculture. “Our

twist on what we think land stewardship should be provides the habitat for many species,” says Craig. “The different management of ranch land across the country provides a mosaic of different habitats, due to the many management styles. This is beneficial for wildlife, to not have just one type of universal management method. With a focus on food and fiber production (to benefit people), this is how we get to stay in business and do this, but we are in a unique occupation where we can take care of the land and grow food and fiber for a growing human population as well.

“We shouldn’t dumb it down; there is a lot to it. You can take the science approach, the observational approach, or a ‘this is how we’ve always done it’ approach, but personally I think the people who take the latter approach eventually fall behind because they are not adapting. As different information becomes available, such as high-intensity short-duration grazing, we need to pay attention. “We are catering our management to our strengths and we are just one adjective away from being sheep herders. We are cow herders. We enjoy the cattle, the frequent movements, and the land stewardship in general. This is what gets us up in the morning, eager for a new day—and not the dollars involved. That’s what keeps us up at night (worrying about the financial aspect)! The joy every morning is in the job we are doing with our cattle and the land.”

Craig and Conni also understand the importance of passing on a land ethic to the next generation, and want to make sure that their ranch will stay productive into the future. They have engaged their three children in ranch planning. They also recognize that even if their kids don’t take over the ranch, they would like to pass on a ranch operation that is sustainable, both environmentally and economically.

The Frenches are pleased that they have partner organizations that feel a connection to their ranch, and their Leopold Award is an indicator of those connections. “The folks who asked us to apply volunteered to fill out the application forms, so that made it easy for us to agree to,” says Craig. “The thing that warms our heart is the fact that they felt like they were a part of our place and knowledgeable enough to go ahead and fill it out for us. We had benefited from their education, in whatever field they are in—whether it was BLM, NRCS, Fish, Wildlife and Parks, etc.—and filtered it to how we think it applies to what we are doing. These folks wanted us to put our name in the hat and offered to write things up for us.

“We plan to continue our open door policy and hope to be able to help other people along the way. The really neat thing about the Leopold Award is that it gives us an opportunity to connect with other people and maybe help them if they are interested in some of these things--if they think it will fit their management to go this direction. The Award is a good way to help spread the word. It’s not that we have it all figured out (we are just trying to do the best job we can, with what we have—and keep trying to improve because we know we still have a long way to go), but we might be able to inspire someone to go ahead with some changes on their own place.”

12 Land & Livestock h July / August 2021

Craig French moving the yearling herd.

Photo Credit: Isaac Miller

Barney Creek Livestock— Transitioning a Montana Ranch to Regenerative Practices

BY HEATHER SMITH THOMAS

BY HEATHER SMITH THOMAS

Set in the beautiful Paradise Valley near Livingston, Montana, Barney Creek Livestock is a family operation devoted to regenerative agriculture. Pete and Meagan Lannan have been practicing Holistic Management for over six years and feel that it’s the only way they have been able to remain in agriculture. Their ranch was runner-up in 2020 for the Montana Aldo Leopold Award.

This ranch has been in the family since 1900, when Pete’s great grandparents, Rueben and Mary Ellen Forney, purchased it from the estate of Barney Maguire, who homesteaded the place in 1867. Three generations currently live on the ranch.

Pete’s parents, Larry and Cathy, the third generation, grew the ranch to what it is today, after Larry bought it from his own parents back in the late 1950s. Pete and Meagan, the fourth generation, currently operate the ranch as they raise the fifth generation with a passion for regenerative agriculture—daughter Maloi, 14, and son Liam, 12.

“When my dad took over the ranch, it was the era of modernization,” Pete says. “My dad built up the cattle herd and some nice pasture and did a little bit of everything. He always had a job on the side, as well. I’m the youngest of five children in the family, and when I was about nine years old my parents started a small dairy.

“We operated the dairy until I was 18 years old, and since I was the youngest and the last to leave home, I think that’s part of the reason why it ended when I was 18 and went to college. The labor was leaving, and that’s when my dad went back into beef cows.”

Making the Transition

But, Pete was always interested in the ranch. “I would leave home, but always came back, and helped my dad. About 20 years ago Dad had his first hip replacement and then my mom convinced him that he needed to sell all the cows. He did some other jobs and he and my mom put up a lot of hay and I helped out when I could. I worked for the Forest Service from the time I got out of high school and started on the trail crew, then ended up fighting fire. I was gone a lot (on fires around the nation) for about six months every summer, so I wasn’t able to help very much on the ranch,” he says.

“Then five years ago my dad called me, and I was in West Yellowstone fighting fire. He asked if I wanted the ranch to keep going and said that he was going to lease it to someone else unless I could figure out a way to make it work. This got me to thinking pretty hard, since I still had to work for the Forest Service for another six years or so before I could retire. I started reading a lot of different things and stumbled across the concept of grazing year round and not farming.”

Pete knew he wouldn’t be able to put up hay and continue his Forest Service job and it would not be economical to have anyone else put up the hay. “Looking at the cost of equipment, etc. I had to find another way to keep the ranch going. I started reading about Allan Savory and what he was doing, and read books by Joel Salatin. I watched some YouTube videos late at night after work and got ahold of some of Gabe Brown’s information and thought it was pretty amazing. I read Jim Gerrish’s book Kick the Hay Habit and a bunch of other books about grazing,” he says.

“My interest in Holistic Management and rotational grazing started out as a purely economic need; I didn’t want to have to prop the ranch up with my outside job; I wanted to have that job for our family’s living and I also wanted the ranch to be profitable on its own.” His venture into Holistic Management and regenerative agriculture started out as being frugal and not having the time to do a lot of farming. It was a matter of necessity.

“I realized I could probably hire someone to move cows frequently and it would be simpler (and less risky) than hiring someone to run machinery. Moving cattle still takes some skill, but not the type of skill required to operate a $150,000 tractor and baler. It’s a little different skill set.

“I brought this idea back to my dad and he didn’t think it was a very good idea; it didn’t make any sense to him. So that first year I told him I could just put some cows on a small section and hire a high school student to move cows around the ranch, just to try it. That young man spent a couple hours a day irrigating and moving cows. We did that for one year and it worked out pretty well”.

It worked well enough that his dad thought it might work on more of the ranch so they turned most of the hay meadows into pasture. Pete started dividing those meadows into big pastures, using high tensile wire fence.

“I had started strip grazing those meadows the winter before and got the hang of using poly wire. I did some research on how to do it because a lot of our ground is under pivot and irrigated, which made it nice to manage. I started figuring out how to set things up to rotationally graze it, with temporary fence, and went from there.

Number 198 h Land & Livestock 13

ON PAGE 14

CONTINUED

Pete, Liam, Megan, and Maloi Lannan.

Barney Creek Livestock

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 13

“One of the things we talked about was input costs and why we did certain things such as deworming our cows. It was very expensive for what we were getting from it. We started reading about that and then got into the topic of dung beetles and focusing on soil health—and eliminating inputs that kill things.

“I didn’t want to spend a couple thousand dollars here and a couple thousand dollars there and started wondering what the consequences might be if we didn’t. The other thing we had to deal with was the fact that I can’t be here in February and March calving, so had to figure out when I could be here—or if I can’t be here, when would be a good time to calve. Luckily we have a neighbor who had been calving in May for about 15 years.”

It happened that Pete was gone one March for training, and Meagan had to get a cow in and pull a calf. It was late in the evening and snowing after she came home from work—in a dress and heels. She got the cow in and called the neighbor. “He and his wife came and helped pull the calf. They got to talking with Meagan about calving, and afterward he and I got to talking and I asked him how long he’d been calving in May and what he thought about that. He told me he’d never go back to doing it any other way.”

That’s the year Pete decided to start calving later. “I just held the bulls out until after mid-July and then turned them in. In the mean time I heard about some other people in our area who were calving in May and I called them. One was Roger Indreland. I am a pretty shy person but I just called him up, out of the blue, and this was pretty hard for me to do. I called him after work one day and talked to him for two or three hours. One of the things I asked was how he transitioned into calving later (starting end of April/early May). He did it incrementally over four or five years but said he wished he’d done it all at once. The cows that fell out of the production system would have fallen out in just one year instead of over the course of four or five years. I was glad to hear that, because that’s what I did.

“Now we were addressing the economics, the environment and the part that is most challenging—the human, social side of it. Meagan is an outstanding, outgoing person; she finds friends and resources and people to talk to. She found some folks that have been good support for us, and

Creating a Team

Pete and Meagan make a great team as they have similar values and interests. Meagan grew up in northwestern Montana—in the little logging town of Thompson Falls--but she and Pete didn’t meet in Montana. “My dad was a logger, a cowboy and a rancher,” says Meagan. “My mom was a librarian and didn’t like ranching very much. She did 4-H with all of us kids but hated how the cows took so much of our time. I loved it, however, and went everywhere with my dad on the back of his horse until I finally got a horse of my own—and I just loved ranching.

“I grew up, graduated and did many things, then ended up in Nevada on a hot shot fire crew in Carson City. I really thought that was where I would stay—maybe in Elko or Reno. I was a wildfire apprentice and met a gal through the apprenticeship program who worked for Pete on his fire crew. For two years I kept hearing about Pete; it was Pete this and Pete that, so I began to wonder, ‘who is this guy and what is his deal?’ because all his employees kept talking about him.

“I became friends with that gal through the Wildland Fire Apprenticeship Academy and she was marrying a college roommate of Pete’s who was also Pete’s good friend. I was on this hotshot crew when she asked me to be in the wedding, which was going to be in Big Sky, Montana. I thought that would be nice—to get to go back to Montana— and was pretty sure we’d be done with fire season by then. But we got a call the day before I was to leave to go to the wedding, to go out on a fire. I’d had a lot of hours of overtime by then and by October I was really ready to hang up my boots. So I made a big deal about having to be in this wedding. My superintendent told me to quit worrying about it and just get in the truck, and promised me he would get me off that fire.

“My dog and I got in my truck and drove straight through from Carson City to Big Sky. I’d been around all these Elko cowboys who really knew how to dance, and grew up dancing with my dad who was an amazing dancer, so I loved to dance. At the reception, in walks this tall handsome guy in a big cowboy hat, with a big ol’ mustache and I wondered who he was. Then I saw him dance and I thought, ‘Oh man! I am going to dance with this guy all night!’ It was Pete, and that was pretty much all it took. I moved to Livingston, Montana and have been here ever since. So that’s how we met—at a wedding—and it got me back to Montana!”

14 Land & Livestock h July / August 2021

we just had to figure out our own part in this.”

The Lannans use temporary fencing to divide up the pivots for grazing (post graze on right and pre-graze on left).

Improved grazing has led to increased productivity, soil health, and diversity of forage at Barney Creek Livestock.

Working on Genetics

Pete says their cattle enterprise is just a small operation. “In 2011 my dad was diagnosed with cancer and by that time had sold all the cows. In the middle of all that, he decided that we should get some cows again. It wasn’t at the peak of the market, but certainly not the cheapest time to buy cows. We got some contacts and found a few cows and got back into the cow business during that time he was fighting the cancer and trying to get better. He’s done well with it, but it was challenging.

“Of course we bought the wrong kind of cows. They were the kind we had before—1,300 pound cows that calved in February, and all black. Since we started down this path we’ve been focused on different types of enterprises, but as far as our cow-calf operation goes, we found a seedstock producer who is focused on efficiency, smaller-framed cows, good leg structure, etc. We have such a small herd we probably shouldn’t even keep our own replacements but I can’t help myself,” Pete says.

“So we’ve been focusing on buying bulls that sire heifers with those qualities— smaller framed animal, more efficient on grass, etc. We live in a part of the country where cattle can do pretty well for most of the year on grass but sometimes we get a lot of snow. I’d like to be able to only feed for 30 days or less; those are the kind of cows I want.

“It’s partly just me being stubborn, and pushing them pretty hard. We are now to a place where our average cow size is 1,200 pounds or under. I am excited about our replacement heifers this year and looking forward to watching them calve next year and keeping calves from them. We have a mix of red and black Angus.”

Pete and Meagan both love the red Angus. “They seem to do very well and haven’t had as many of the good traits bred out of them. If we had our choice we’d run all red cows and buy some red bulls—if we were just selling grass-fed beef direct to consumers. As it is right now, however, we market some of our calves through traditional means and everyone wants black calves. So we buy black bulls, since you always get black calves from them. We have found some good niche producers, like the Indrelands, who produce that kind of bull, so this works.

“Since we started doing this, we’ve been leasing a few places, and some of them are more conducive to daily moves while on other places we don’t move the cattle as often due to lack of infrastructure. It’s fun to watch those cows. Even when you move them only every few days, it’s interesting to watch them and see how they act.

“Several of our leases have a lot of good forage and also a lot of weeds. The cows will eat knapweed and thistles and they work as a herd. Even when you don’t confine them so closely (and don’t move them often) like we do down here at home where we push them harder to work as a herd, they have that behavior built into them now.”

Learning & Sharing Knowledge

Meagan says the other piece of the equation regarding Holistic Management is education. “I hung up my fire boots for good, had two kids and stayed home as long as I could for them. The time came when I needed to get back into the workforce. I ended up with a job at the Department of Labor and Industry (DLI) doing Work Force Development. This position puts you in an education mode because you are trying to bridge career and education to upskill or help someone shift to a different career. Working with DLI, I did workshops and training/ education. I traveled across the state and worked with business and industry connecting skills and education with their needs. I did a lot with job shadows, internships, and apprenticeships with high school students exploring careers and the workforce. I was also learning a lot about what we do here on the ranch and realized that most people really don’t know what ranchers do or the way Pete and I do things, which is different.