Are We Growing in Our Understanding?

BY RALPH TATE

Of all the aspects of the COVID pandemic that have affected all of us, the one that concerns me the most has been the apparent truncation and termination of open exchanges of ideas and thoughts about the virus. I may be mistaken, but it seems to me that almost any discussion about COVID occurring between people who do not have the same perspective results in either elevated emotions as each side tries to defend their position while attacking the other or abruptly ends because they know that if it continues, that’s where it will end.

On a national and state level, we are told

Decision-Making in Challenging Times

In these challenging times it helps to have a process for decision-making to help you sift through issues and concerns and determine what are key pieces of information or criteria on which to focus. The Holistic Management® DecisionMaking process has helped numerous people determine how and when to invest in a business, how to handle the pandemic, or determine the right production and marketing practices. Read how long-time Holistic Management practitioner, Frank Fitzpatrick, has developed a new business and is working to address climate change.

In Practice

what “science” is and anything else is treated as “misinformation” and forcibly removed from social media sites. Any attempt to share alternative experiences is met with calls of radicalism or name-calling.

So, in the midst of this world that seems to become crazier every day, I think the tools that we have learned as Holistic Management Certified Educators actually enable us to see what is going on and, perhaps provide a saner approach to seeking understanding.

In learning Holistic Management, the first principle we learned was: Key Insight #1—Nature is complex. You cannot change just one aspect of nature. Any change will result in other changes occurring, although the changes may not occur immediately.

Any time we have introduced an herbicide, an insecticide or an antibiotic, it isn’t too long before we find nature starting to produce weeds, insects or bacteria that are resistant to the chemical. So chemical companies create more chemicals, resulting in more resistant plants, insects and bacteria and the cycle just keeps going, to the chagrin of the chemical companies. But we also know that it isn’t just the plants, insects or bacteria that are affected. It is other parts of the ecosystem as well. Entire biological systems are disrupted. Dung beetles disappear from pastures following cattle treated with fly tags. Monarch butterflies no longer reproduce because GMOs have changed the genetic makeup of milkweed plants. And on it goes.

Did it surprise us when we were told to isolate from each other for an extended period of time with a corresponding loss of jobs and social interaction, and we saw a significant increase in depression, obesity, domestic abuse, and suicides? They may have been unintended consequences, but we knew things would not stay the same.

A key concept we learned in decision-making was: When dealing with social or financial decisions, assume the decision you made was correct, but when dealing with biological systems, assume the decision you made may be wrong and look for the first possible indicator that nature

is not responding the way you anticipated.

In his book, Think Again, author Adam Grant illustrates these same principles in a little different way. He says we can act as a Preacher, a Prosecutor, a Politician or a Scientist. We act as a Preacher whenever we believe our sacred beliefs are in jeopardy and our response is to protect and promote our ideals. We act as a Prosecutor when we look for flaws in other people’s reasoning and then attack their position. When we seek to convince people of our position and win them over to our way of thinking, we are acting as a Politician. But the character Grant encourages us to emulate is that of a Scientist, who is constantly aware of the limits of his own understanding. He doubts what he knows and is curious about what he doesn’t know.

One of the examples Grant referenced in his book was Orville and Wilbur Wright and their efforts to develop an airplane. It was not uncommon for the brothers to have different ideas about how to solve a particular problem and become very vocal about their ideas, both becoming Preachers or Politicians in the defense of their own position. Typically, the following day, when they showed up to work, they had thought about the problem overnight and had become convinced that their brother’s approach was correct! They then realized that neither approach was correct, and, assuming the role of Scientists, were able to cooperatively arrive at a better alternative. They were able to do this repeatedly as they worked through the myriad of technical challenges until they prevailed, and on December 17, 1903, Orville Wright became the first man to fly in a heavier-than-air powered aircraft.

In my opinion, one of the major bottlenecks in communication today is understanding that science is never settled. There is no “final” answer. We don’t ever “arrive” at complete understanding. There is always something else to learn that we didn’t realize was connected or even existed. What we “knew” one hundred or two hundred years ago, many times is considered almost comical in its simplicity or its errancy. A somewhat humorous example of this

Healthy Land. Healthy Food. Healthy Lives.® a publication of Holistic Management International MARCH / APRIL 2022 NUMBER 202 WWW.HOLISTICMANAGEMENT.ORG

INSIDE THIS ISSUE

ON PAGE 2

CONTINUED

HMI’s mission is to envision and realize healthy, resilient lands and thriving communities by serving people in the practice of Holistic Decision Making & Management.

STAFF

Wayne Knight Interim Executive Director

Ann Adams Education Director

Carrie Stearns Director of Communications & Outreach

Stephanie Von Ancken Program Manager

Dana Bonham Program & Grants Manager

Oris Salazar Program Assistant

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Walter Lynn, Chair

Breanna Owens, Vice-Chair

Jim Shelton, Secretary

Delane Atcitty

Jonathan Cobb

Ariel Greenwood

Daniel Nuckols

Kelly Sidoryk

Casey Wade

Brian Wehlburg

HOLISTIC MANAGEMENT® IN PRACTICE

(ISSN: 1098-8157) is published six times a year by: Holistic Management International 2425 San Pedro Dr. NE, Ste A Albuquerque, NM 87110 505/842-5252, fax: 505/843-7900; email: hmi@holisticmanagement.org.; website: www.holisticmanagement.org

Copyright © 2022

Holistic Management® is a registered trademark of Holistic Management International

Are We Growing in Our Understanding?

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 1

is in 17th century England, a cure for baldness was a healthy application of chicken dung to the˛scalp!

We grow in our understanding of the world around us only when we ask questions, observe events that don’t make sense to our current understanding and seek answers. It isn’t about who is “right” or who is “wrong”. At some point, all of our current perceptions will prove false, only to be replaced by those with a little more insight. I encourage us to shift our attention from our current answers and pay more attention to the questions, probing to gain a better understanding of what we don’t know.

So, consider the following questions as simply a starting point:

• Do masks work? Some studies say yes, some say no. Why? Why are the results different? Who is paying for the studies?

• Is the COVID vaccine “safe and effective”? Politicians and pharmaceutical companies say yes (although ironically, they are protected from any medical liability). Others want more data and time to see what symptoms are manifested. Most vaccines take 5 to 7 years to be approved, and then only after extensive testing. The mRNA gene therapy protocol is extremely new. How concerned should we be with this one being developed and fielded in such a short period of time? How is nature likely to respond to the vaccine?

• Are there alternatives other than the vaccine to protect people from COVID, like hydroxychloroquine, ivermectin and others? Many epidemiologists say yes, they work. Politicians and pharmaceutical companies say they are dangerous and are causing adverse effects among those who have COVID or have been vaccinated. If that is true, what does that say about the effectiveness of the vaccine? Curiously,

if FDA were to acknowledge existing treatments are available for COVID, it would require them to terminate all current COVID Emergency Use Authorizations (EUAs).

• Ivermectin was developed by Merck Pharmaceutical and approved by FDA in 1996 to treat human diseases; River Blindness and Lymphatic Filariasis. In fact, the treatment proved so successful that the two doctors who discovered the drug were awarded the 2015 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine and now these diseases are on the verge of eradication. So after more than 25 years of successfully treating humans around the world and recognized as one of the “essential medicines” by the World Health Organization (WHO), why would Merck claim it to be toxic to humans at the same time they are petitioning for an EUA by the FDA for their new, more expensive antiviral medication?

• What should we do about the various strains of COVID? More vaccines? Boosters? Coronaviruses have as one of their characteristics the ability to mutate rapidly. Do we really think nature will not (continue) to develop a vaccine-resistant strain? Some of those exposed to the 1918 Spanish Flu epidemic were shown to maintain immunity for over 70 years. Is that true of COVID immunity as well?

• We know that different groups of people vary in their susceptibility to COVID. Those over 65 and those with obesity, diabetes, hypertension and pulmonary comorbidities are more susceptible and can have potentially more severe symptoms. What are the minimum necessary and sufficient actions we can take to provide adequate protection to these people without adversely affecting everyone else? Where in nature do we see that “one size fits all” approach?

• Should the vaccine be mandatory for CONTINUED ON PAGE 20

2 IN PRACTICE h March / April 2022 In Practice Healthy Land. Healthy Food. Healthy Lives. a publication of Hollistic Management International FEATURE STORIES Holistic Decision-Making in Corona Times WIEBKE VOLKMANN 3 Making Room for Relationships— How Journeyperson is Helping Racing Heart Pace Itself BRIAN DEVORE 7 LAND & LIVESTOCK 5 Bar Beef— Cattle Hire Out to Restore the Land HEATHER SMITH THOMAS 9 Bar Cross Ranch— Exploring Production Possibilities on Wyoming Rangeland HEATHER SMITH THOMAS 12 NEWS & NETWORK Board Chair 19 Grapevine 20 Certified Educators 21 Market Place 22 Development Corner 24

Holistic DecisionMaking in Corona Times

BY WIEBKE VOLKMANN

In one of the many “personal growth” events I have participated in, I came to hear about the value of not knowing only where I am going, but also where I am coming from. And that has meant less the historical circumstances than the sponsoring thought, attitude and mood and psychological conditioning that influences my perception of where I am and what I envision. This has certainly been true in the time of the Coronavirus pandemic.

In 2018 I read my first book by Yuval Noah Harari, Sapiens. I have yet to pluck the courage to read Homo Deus, as the three threats to the survival of our species (nuclear war, climate change/ecological collapse and artificial intelligence together with biotechnology) described in Sapiens and 21 Lessons for the 21st Century already confronted me with a pretty scary outlook.

So I felt somehow prepared for COVID-19 as pandemics and the effect of mass influence of our biology via mere information and sound consumption were included in some of the possibilities that Harari describes. He also highlights what seems to distinguish homo sapiens from other existing and past species— that we are moved and guided not by biological and physical needs only, but by mental narratives, where immaterial concepts assume the status of “being real.”

The Power & Discomfort of Difference

Simultaneously with the news from Wuhan during the summer holiday (Southern hemisphere) of 2019/2020, my partner, Conrad, and I watched the wonderful presentations by Walter Jehne from Australia. We learnt that new scientific insight shows that it takes microbes that are produced in green leaves to serve as nucleus for water vapour to form drops so that clouds can form and rain can fall. At last my photovoltaic engineer partner understood what I had tried to explain so inadequately for over a decade—that photosynthesis has much to offer in counter-balancing global warming, not only the advances of technologies that help reduce carbon emissions. While our lack of academic training in these field does not always allow full grasp of the scientific concepts, we were highly attuned to the power of microbes and their mobility!

Many other authors and influential people

and experiences before this time have contributed to my awareness that the loss of biodiversity is what makes human and all life on earth so precarious. As I write this piece now, I am reminded of the long discussions we had with Allan Savory, Christine Jost and other colleagues around the fires in Dibangombe, Zimbabwe about the governments’ questionable strategies of dealing with the spread of the Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD). I learned that if ungulates enjoy healthy nutrition, their immune system can live with FMD and can keep it in check like any other infectious disease. These conversations like many other Holistic Management related concepts were

of where I came from and where I was when suddenly we received information and regulations to prevent catastrophic disaster.

The shock from the global shutdown also came at a time where my friends (a married couple, Simon and Ina) dealt with simultaneously going through chemotherapy and radiation for cancer treatment. While I knew that this would be another uncomfortable experience of integrating loss (of dreams, of a form of life, of companionship) I also sensed the potential of transformation to engage with them during this time.

accompanied by a sense of provocation, almost heresy. I remember the crazy combination of discomfort from “being different” and the excitement from “being different.”

Several experiences later in life brought me to that state where I felt that I had to lose my innocence in order to gain my inner sense of what it means to accept and participate in the full cycle of life. Michael Brown uses this word play in his book The Presence Process.

Living in a community where I have been and still am confronted with my colonialist heritage, I feel deeply grateful to have encountered opportunities and tools for “personal” integration. These focus not only on “external” social and political integration of “the other,” but also on inner integration, which let me face the exploiter, the perpetrator, the predator, the prey, the victim, the donor, and all those states in between which are not publicly acknowledged, but keenly felt in moods and private thoughts.

COVID & Inspiration Strike

What does all this have to do with experiencing COVID-19? It is an overview

Ina had started an urban farm on the outskirts of our capital city with the poor inhabitants of the informal settlements, all economic migrants from our Northern communal lands. Once a week she drove out there to coach the group in permaculture principles and brought support to implement these on the steep and stony grounds the municipality had provided. Besides precarious food security, these underserviced informal settlements had suffered from outbreaks of Hepatitis E, as there are no toilets and pre-paid water collection points only. Washing hands under running fresh water, rather than everyone sharing the same bowl of water over and over again was needed way before COVID-19 started.

When my brother sent me a picture of a “tippy tap” he had built for the staff of his compound on the coast of Kenya, I loved the simple design demonstrating powerful laws of physics (see the picture) and that it could be built from waste materials. Having just watched the very helpful videos by Dr Martin Wucher, a local dentist, farmer and lifelong student of microbiology, I had an idea of what a virus actually is and what determines its integrity and destruction and how many multiple and beneficial functions viruses perform in the environment and in my body. I knew that the “fatty layer” that forms the “skin” of the molecule can be broken up by the warmth generated by rubbing hands together and using soap to help break up the “fat.”

Inspired by a YouTube instruction of how to assemble a tippy tap, I built one for my own home, asking everyone to wash their hands

Number 202 h IN PRACTICE 3

CONTINUED ON PAGE 4

Wiebke (in back) working with communities on creating their own compost piles.

Holistic Decision-Making in Corona Times

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 3

before entering. Then, during our weekly Saturday meeting over coffee at the Farmer’s Market, I said to Ina, that I’d love to help bring this technology to the informal settlements. Could we possibly collaborate and use the team from farm Okukuna and the youth members of the Shack Dweller’s Federation to build tippy taps all over?

Ina promptly spoke to her donors. Their planned garden trainings could not take place because of lock-down regulations, but building tippy taps counted as essential service. The money for the trainings could be re-allocated and paid to the community members. The 2020 Tippy Tap Challenge was born. In these weeks, people, mostly women who lost all their income opportunity from selling food by the road side, earned money for each new tippy tap of which they sent in a photo and location pin.

To protect Ina from a possible infection of not only COVID, but a common cold or stomach bug, I could function as a go-between.

While everyone else went into isolation, and while I witnessed the scramble for hand sanitizers and masks everywhere I used the Holistic Decision-Making questions to assess an alternative plan of action:

Should I collect and source materials (mostly recycled waste) and distribute them in Katutura, showing groups of people how to build and use tippy taps that use small amount of water and ordinary soap and address the need for greater hygiene with limited resources? In the process I would be getting into contact with a lot of dirty materials, transporting them in my car (a Nissan Leaf), while knowing that I could carry pathogens to my partner who has preconditions that make him “vulnerable” (having had cancer and having had a very serious pneumonia the year before) and my friends being weak from cancer treatment.

Here are my responses to the questions. Please be warned that I add a lot of associated thoughts to express my attitude and understanding of complexity.

Root Cause/Cause and Effect

Clearly I would never have started building tippy taps had there not been a problem. Where was/is the root cause of the problem of C19 threatening lives? Our failing town planning and municipal service delivery? The uniform advice of a global entity for isolation, which results in separation, not considering location and context specific conditions and the collateral damage

of such strategies? The loss of biodiversity that makes one entity (one virus) so powerful? The lack of knowledge and awareness that prevents individuals to think for themselves and to adopt response-able and preventative behavior (such as hand hygiene to reduce infectious disease impact and to support biodiversity in our daily lives)? The fear of loss (of lives, of power, of certainty, of comfort, of hope)?

For me it was and is a combination of all of these. Besides offering technical and material assistance our action would contribute to education and awareness about microbiology (my own and that of those I was working with). I also saw the action focusing on what everyone could and can influence, rather than focusing on the worry and fear about the “invisible enemy,” the things we could not understand and influence. This could strengthen the psychological confidence, resilience, and creative response which is so important for a good immune response. The reasons why we used a lot of refuse and repurposed materials was to encourage our partners to improvise, rather than giving them standard materials from a hardware supplier.

Vision

The description of my holistic context includes: “A diverse, vibrant community of living organisms, humans and others; people who are critical thinkers, confident, self-determined, response-able citizens who enjoy good health, livelihoods and peaceful connections. People in my community know how their lifestyle choices contribute to all of this. People appreciate innovation and relevant education and development programs. Infrastructure and natural resource management is guided by principles of regeneration.”

I would bring material means to the people, but I would also have conversations and would demonstrate through my own practices and choices some ways of supporting my immune system, always remembering my privileged situation, but also establishing the common ground which made or makes our choices similar, if not equal. I shared my knowledge and experience with nutrition, the value of movement, especially joyful movement, of being out in the sun, of breathing deeply. Most of all I encouraged open conversations about fear. These conversations revealed all kinds of unexpected comparisons, raising awareness for imagined and for real fears. It also revealed what people appreciated about this down time.

Although I envisaged it, I didn’t formulate the following results in advance. The connections that emerged through the Tippy Tap Challenge

later led to me facilitating a Holistic Management based training of the Farm Okukuna community, where there was further opportunity to reflect on what was/is really important to everyone individually and collectively and what strategies were/are open to them to realize these values. The trust that Ina and the Okukuna group developed in me allowed us to develop greater ecological and economic literacy and greater agency for people who mostly experience themselves as either resigned victims of circumstances or dutiful but unquestioning followers in a patriarchal system.

Weak Link—Biological

My understanding of microbiology let me think that this one molecule could only get to be so dangerous because the “natural enemies” were weakened and conditions favourable for the one virus. Also, by learning more from the clinical experiences of diverse doctors treating C19 patients in remote and non-governmental hospitals and practices, I learnt that reducing the virus load in symptomatic patients was critical, while asymptomatic carriers were not leading to the spread of the virus as much as was claimed by officials.

With trepidation I wondered how Windhoek’s water treatment system was affected by the rampant use of non-specific sanitizers while we at the time had such few positive cases. (Windhoek has the biggest water reclamation plant on the Southern Hemisphere where sewage water is turned into drinking water mostly through microbial digestors.)

Using ordinary water and soap for washing hands frequently would reduce the favourable conditions for human infection, without compromising the microbial diversity and interaction that can help to keep pathogenic viral spread in check.

Weak Link—Social

There were and are people among my acquaintances who considered the tippy tap and ordinary soap not “strong” enough to deal with the immense danger at hand. Others again found my mingling with many people reckless or selfish or not being in solidarity with the fate (restriction) that everyone else dutifully adhered to, declaring my own “essential service” status in order to move about, rather than getting an official permission.

Fear and shame and the need to belong with a group are strong forces. I now consider myself fortunate that I met the dark side of these forces long before COVID-19 and that I found ways of integrating them along with the wonderfully broad range of emotions that create social

4 IN PRACTICE h March / April 2022

connections and boundaries.

I remind myself again and again that I have a choice of letting my actions come from fear— or from trust and love. There are times when they don’t come from trust and love, but from a crazy mix of fear, curiosity, wonder, desire, and many other drivers. The important thing for me is to remain aware of all these motivational dynamics and to be authentic. While our Holistic Management training has taught us that this question is about establishing necessary support and compassion for an action, I now find it equally important that we consider the courage to bear the disapproval of people rather than trying to explain to them why I am doing what I am doing and how when they are not really open to this. To lose friends, to lose respect, to lose trust, to lose stability all these things now sometimes seem to be asked from us if we want to be authentic and conscious.

So I asked my sick friends and Conrad how they felt about me being a potential carrier, putting us all at risk of infection. They all responded by asking to be sensible (i.e. washing my own hands and body after coming back from my outings) and when we came together for our Saturday breakfast, sitting out on the veranda in front of Simon and Ina’s house, not hugging and touching anymore, but sharing a table and laughing without masks hiding our faces. We enjoyed good food and celebrated life and companionship, critical and courageous conversation and sensual pleasures as much and as long as we could.

What the social weak link test does for me is to regularly check in with my partner and other “significant others” even if I don’t need to “test a specific action.” I do this to see how they change, to let them experience my current state so that together we may remain alert enough to recognize new opportunities for transformation and consciousness.

For me the global social weak link is that the generalized C19 response, distributed by political governments and capitalistic networks did not sufficiently consider the specific climatic, geographical, demographical, economic, cultural and other aspects of context. In Namibia we soon felt the collateral damage to existential survival.

I don’t only speak of material breakdown (tourism being such an important income and job creation sector), but also of the

psychological confusion and polarization. Suicide has for long been rampant in Namibia. Countless (countless, because those figures seem not important enough to be researched compared to the daily C19 statistics) babies were conceived into highly insecure households or even worse homeless situations, because the public clinics ran out of condoms and birth control pills due to lack of foreign currency, C19 measures, and due to enforced idleness and cramped living conditions without public meeting

the context of COVID-19 did not squash my capacity for rage and courage. Rather than expressing that rage as disapproval with the status quo, I try to channel the energy into joyous determination and creative projects that generate what I want, rather than fighting what I do not want—such as co-facilitating learning events for organic compost making and agriculture, linking these with nutrition education and tasting opportunities, improvising illustrative learning aids and more.

From the natural and unnatural deaths in my family before COVID-19 I have come to experience compassion as the willingness to witness suffering. This can be very very challenging, especially when guilt creeps in when I am not suffering myself. Being with all the emotions and states that another is going through without being able to or consciously not trying to change what they are going through comes from a deep trust that our awareness can grow deeper and wider from pain and discomfort.

Weak Link—Financial

The economic effect of my action with the Tippy Tap Challenge was only partly planned and tested. Prior to COVID-19 I had very few professional engagements, given the fact that Namibia didn’t qualify as a low-income country anymore since it was classified as middle-income. Most of my professional work had been with marginalized and resource poor people, financed by foreign donors. I was and am in the privileged position that I have rental income from property and that my partner contributes to household expenses.

of these policies, I am reminded of a panel discussion with Rianne Eisler, famous for her passionate work for partnership. The panel discussed appropriate responses to the #Me Too movement. In her closing remarks Eisler said what is now asked from us is courage and that the word courage comes from the Latin word cor—meaning heart. As far as I recall Eisler said the second part of the word rage is equally important: providing the energy needed to speak for and from the heart.

For me, my concern for social cohesion in

The Tippy Tap Challenge I initiated as a pro-bono action, not expecting that it would result in a new client and opening up lucrative and satisfying paid work. In a way I could not foresee but which I felt instinctively it addressed my marketing weak link.

For me this experience confirmed that abundance flows from the combination of joyful determination and humility to accept things as they are rather than worrying about potential failure.

Money and Energy—Source and Use

Besides the real joy of gliding silently through CONTINUED ON PAGE 6

Number 202 h IN PRACTICE 5

Wiebke’s home Tippy Tap in use.

Holistic Decision-Making in Corona Times

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 5

the quiet streets of our capital in the middle of the week with my electric car, I know I would not have easily taken on this project did I have to go with my “other” petrol guzzling car. Yes, the electric car stank from all those used yogurt, milk, soap and water containers, but I relished the fact that this gift I had received a year earlier from my partner served so many good purposes. The fact that we were using recycled materials, rather than buying new containers and metal bars as the other Tippy Tap Projects implemented in the informal settlements, spoke to my understanding of re-using the energy invested in the manufacture of goods. It also set an example that people could build a tippy tap without having to wait for money from outside. We used donor money that otherwise could not be spent on urban food production. The payments to the community members contributed to only temporary food security. However, the action introduced me to the planning process and the training scope at the urban farm. When I was asked to design a capacity building curriculum for 2021 I insisted that record keeping and holistic financial planning on a household level must be taught to make the “beneficiaries” more self-reliant in the long run. Later in 2021 I lost Okukuna as a client again, but the work I was able to do there opened another door, this time even bigger and more in line with my values.

How Do I feel About this Action?

I started off having a big “checkmark” in my heart and it was still so, after having gone through the question catalogue. I realized there were risks and I determined that the earliest indicator I would watch would be the moment to moment responses of all the people I would come into contact with. If they expressed discomfort or objection, or if I myself would feel unsafe, I would reconsider.

I was also influenced by an online presentation by a Nordic European psychologist I watched. He spoke of modern society’s addiction to safety and security and how the insurance industry is testament to this. Through his profession he has been in close proximity to despair and anxiety for most of his life. He has started to question if one of the root causes for rising mental health problems was not the widely sanctioned and encouraged aversion to risk and the subtle spread of fear. I, too, question that.

Early Warning Signal

I resolved to be vigilant and watch out for all messages and to integrate this feedback for future action and decisions. I found that in my interactions with the people in the coming months, there were plenty opportunities to rejoice, to laugh, to play, to realize freedom, to celebrate our natural authentic way of being and not only the “normalized behavior”. We embodied this realization by meeting physically, trusting our common sense, all the while being considerate and cognizant of the fact that our common sense did not and does not know exactly the nature and extent of this pandemic and what it wants from us as individuals and as community.

Closing Reflection

What I celebrated at the close of 2021 is the fact that I found new playmates, that I can design creative learning and practice activities that combine rational understanding, bodily sensing and compassionate insight – all to build capacity for complexity and awareness of systemic dynamics.

I witness how these activities speak to intellectually highly trained and articulate people as well as to people who have only rudimentary formal education. I let myself be surprised by the fact that I was asked to submit proposals by staff from an international development agency who I had come to avoid for their “tick box” programs. I listen to my partner’s gloomy reports of what further information he found about the worldwide threats to democratic values and self-responsibility. I also listen to online presentations by highly acclaimed scientists to build my capacity to understand the basics of biochemistry and microbiology, as well as political psychology. The increasing number of scientists who come from a systems paradigm and who courageously face the reductionist establishment fills me with gratitude and wonder that I am alive now.

Corona afforded me to linger at the farmer’s market and chat to a local retired professor of Sustainable Agriculture, Dr. Ibo Zimmermann. Through him I got to know the work of Walter Jehne, Garry Gillespie and then of Dr. Zach Bush who all link the deterioration of human immune systems to agricultural practices and how we treat the environment. These scientists speak as human beings, recognizing the psychosomatic effect on biological functions.

Hearing a practicing doctor who also conducts and collaborates in clinical research speak of the mass extinction event we are now in and that as a species we may be lucky to have another 70 years can be unsettling.

But when I hear and see the work of the foundation he established for regenerative farming (Farmer’s Footprint) and when I hear him sharing the excitement that lies in evolution coming up with yet other forms of intelligent existence, a kind of growing on my compost heap of being homo sapiens, I find courage to face the uncertainties.

With my interpretation of holistic decisionmaking, the creative work with soil, plants, animals, and other living organisms is a lot more relevant and effective in creating mutually beneficial connection and healing than deciding to get vaccinated or day to day wearing of protective gear against a virus which proves difficult to be controlled and even managed and this virus causing relatively few people to fall ill, compared to other medical conditions.

Considering the bigger context in which I live, I feel that after the political independence from South Africa we in Namibia have had to enter composting. Old structures and habits and orders needed to break down. Composting is never a beautiful business. The transformation happens in the dark. Form is lost in the process of decomposition and nobody knows yet, what will grow in and from this nutritious mess. The compost heap has assumed a mythic importance for me—helping me to accept death and dying, accept uncertainties, accept insecurity, accept change and also disappointment as a way of getting to know the real. In German, disappointment is called Enttaeuschung, meaning the fake is removed.

I am willing to make mistakes and learn from these mistakes. In the process my body shows me what the consequences of inviting biodiversity can be—through a fungal infection in the ear and under a fingernail. It demands discipline to maintain hygiene, and I approach it with curiosity, rather than fear. It requires being willing to embody my knowing with all the potential risks. If I compare these with the little talked about personal and public health risks that come with industrial agriculture, they seem manageable.

I am reminded of a saying Allan Savory used when teaching us what goes into formulating and being invested in a holistic goal: Are you willing to die for this? At the time I rebelled against this statement. I wanted it to be Are you willing to live for this? Yesterday, during a year-end reflection, my friend Tossie offered this view: “If what you are willing to die for is the same as what you are willing to live for (and not “just” survive), then you are in integrity.” For me, nurturing the awareness for this integrity forms the foundation of physical and mental health.

CONTINUED ON PAGE 19

6 IN PRACTICE h March / April 2022

Making Room for Relationships— How Journeyperson is Helping Racing Heart Pace Itself

BY BRIAN DEVORE Land Stewardship Project landstewardshipproject.org

Reprinted by permission.

Pack-shed or people? That’s the question Les Macare and Els Dobrick are grappling with on a dank day in mid-March as they brave a biting wind to inspect the garden plots, cover crops, and outbuildings on Racing Heart Farm in western Wisconsin. With the exception of some onions sprouting in one of the hoop houses, little sign of the coming spring is in sight, but the vegetable farmers need to decide soon how they will approach the 2021 growing season. Like many Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) operations, COVID-19 launched Racing Heart on a bit of a roller coaster ride in 2020. Demand for shares exploded as the pandemic fueled concerns about the food system and people were spending more time at home, cooking.

“We had a hard time saying ‘no’ last year. We capped it at 100 members and then opened it up again when we were hearing everybody’s CSA was filling up,” recalls Macare. “And also we heard that one of our farmers’ markets was going totally online.”

As a result, the CSA portion of Macare and Dobrick’s farm more than doubled from 70 to 200 shares in one year. The vegetables produced for those shares were shifted away from what they had been selling through two farmers’ markets they serviced on a weekly basis, so they didn’t have to cultivate more land to meet the requirements of the expanded CSA enterprise. But there was one downside to the CSA-centric shift: preparing more share boxes means more time in the packing shed and less time with customers.

“We like the efficiency of the CSA but we also get a lot from the farmers’ market — it’s exhilarating, it’s fun, we get to have face-to-face interaction with the people who are seeing the vegetables right in front of them and oohing and ahhing,” says Macare.

Would 2021 be another mega-CSA year, or would they shrink back that portion of the enterprise to provide more face time at farmers’ markets? Fortunately, Dobrick and Macare feel equipped to make such decisions thanks

to the training they received through the Land Stewardship Project’s Journeyperson Course. Through that experience, they learned that when making farming decisions, it’s not just about dollars and cents, productivity, and efficiency— it’s also about meeting the needs of every aspect of the farm in a holistic way, from the health of the soil to the quality-of-life of the farmers themselves.

That training has given them the tools to regularly “check in” and assess whether the decisions they are making contribute to the overall success of the farm or are leading them down unfruitful side roads.

“We can actually take a particular piece out if it’s not working for us and that’s okay,” says Dobrick. “We don’t have to just get so focused on one enterprise or spreading ourselves too thin, or focusing on something that isn’t working out.”

From Sand to Soil

The couple has been thinking a lot about how to stay true to their values since launching a small vegetable operation in Minnesota on a half-acre of rented land in 2014. They concede that first foray into farming together was a flop agronomically—it was on extremely sandy soil with a pH level only a pickle maker could love. But it helped them realize they liked farming and that they could work together raising food.

Neither Dobrick nor Macare grew up on a farm, although they both have grandparents with farming backgrounds. Macare, 38, grew up in Connecticut and has worked on vegetable operations on both the East and West Coast. Dobrick, 45, grew up in Minneapolis, lived in Seattle for a dozen years, and came to farming through an interest in native plants and small-scale gardening.

After the first year on the “sand farm,” they rented land for two more seasons on another piece of ground in the Twin Cities area. Through that experience, they gained more confidence in how to raise vegetables on a larger scale for a combination of farmers’ markets and CSA customers. But the couple felt they still lacked

the business acumen needed to make farming a full-time career.

“We had no idea how to do the finances and just having some structure sounded really nice,” says Dobrick.

In 2015, they enrolled in LSP’s Journeyperson Course to get grounded in nutsand-bolts financial management. The year-long Journeyperson Course is designed to support people who have several years of managing a farm under their belt, and are working to take their operation to the next level. It provides advanced farm business planning, a matched savings account, and a mentorship, as well as guidance on balancing farm, family, and personal needs.

In a sense, Journeyperson is a good “postgraduate” step for people who take LSP’s Farm Beginnings course. However, like some other Journeyperson participants, Dobrick and Macare are actually not Farm Beginnings grads.

They found Journeyperson’s focus on Holistic Management particularly useful. Holistic Management, which was developed four decades ago by Allan Savory, focuses on “big picture” decision-making and goal setting processes. Savory’s expertise is in the area of

livestock grazing, but over the years Holistic Management has helped farmers of all types, as well as other entrepreneurs and natural resource professionals, achieve a “triple bottom line” of sustainable economic, environmental, and social benefits. In a Holistic Management system, a farmer’s quality of life is put on the same level as the health of the soil or the operation’s economic viability. Holistic Management relies on a process of constantly monitoring whether a certain decision on the farm is helping meet

Number 202 h IN PRACTICE 7 CONTINUED ON PAGE 8

Els Dobrick and Les Macare.

Making Room for Relationships

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 7

long-term overall goals, or is just an off-ramp toward something that in the end may undermine a farmer’s values and needs.

For Macare, who studied “non-violent communication” some years ago, Holistic Management was a bit of a homecoming. Founded by Marshall Rosenberg, non-violent communication is based on the idea that every person has the same basic set of human needs, and every action that we take in life is an attempt to meet one of those universal needs.

“Basically, Holistic Management is nonviolent communication for your farm,” says Macare. “When you think about holistic goals, you’re really talking about your needs, your values. Conflict only arises when we’re trying to meet those needs or values with a specific strategy.”

To reduce that conflict, one needs to keep in mind not only their own needs, but the needs of who they are farming with, as well as neighbors and the wider community, say Macare and Dobrick, adding that when they started farming together their romantic partnership was new. That meant having a framework for talking about bigger personal/farm business visions and goals was even more critical.

“Farming is very much a lifestyle, so having language to talk about that within a structure that we’re trying to create together is key,” says Macare. “It isn’t just about our relationship with the land, it’s also about how we interact together.”

A Useful Delay

Such relationships became even more real

to the couple in 2017 when they purchased 36 acres of a former dairy farm in Wisconsin’s Dunn County. The farm is an hour-and-a-half from the Twin Cities and 25 miles from Menomonie, Wis., providing good access to markets. However, Dobrick and Macare ended up with more land than they need for their garden plots. They grow about 1.5 acres of vegetables—the rest is pasture and woods. The farm was sold to them by landowners who had listed it in LSP’s Seeking Farmers-Seeking Land Clearinghouse because they were looking for someone who would use it as a farm and a home, rather than just bulldoze the house and outbuildings and make it another corn-soybean field. Thus, the sellers were patient as Dobrick and Macare went through the eight-month application process of getting a USDA Farm Service Agency (FSA) Beginning Farmer Loan. Beginning farmers often express frustration over the lengthy FSA loan process, but Macare and Dobrick say the delay actually helped them become convinced they were ready to be landowners.

“After the second season of renting, I was ready to have our own place to invest in,” says Dobrick.

And the loan application process gave them a chance to put the Holistic Management financial plan they had developed through Journeyperson to good use.

“We could just hand over the spreadsheet to our loan officer and it made sense to her, it wasn’t just my chicken scratch note-keeping,” says Macare.

Having organized financials has also paid off since they moved onto the land and applied for other grants to help with developing infrastructure. In the past few years, they’ve received another FSA loan along with a private grant through the Lakewinds Organic Field Fund to help build a pack-shed. Macare and Dobrick also successfully applied for USDA Environmental Quality Incentives Program support to erect a second hoop house in addition to the one that was already present on the farm.

“It seems like every year we have occasion to organize and submit our finances to somebody,” Macare says.

In general, the news that those spreadsheets are relaying is good. Through expansion of markets and putting aside money on a regular basis (something they got accustomed to through Journeyperson’s matched savings account program), Dobrick and Macare are at a place where they aren’t relying on off-farm income to get by. This has provided them the ability to take a longer view of what they, and the land, need.

All Ears

As the farmers walk the land on that March day, they point out areas where they want to establish more pollinator and other natural habitat. They also describe the no-till production system they are establishing as a way to build soil health and shield the land from the extreme weather that’s become more common as a result of climate change. With a combination of hay mulch, cover crops, broadforking, and utilizing landscape fabric to deny weeds access to sunlight, they’ve been able to avoid intense disturbance of the soil without using chemicalbased weed control.

Long term plans include possibly using the rest of the farm as an incubator for other beginning farmers. They are currently letting a neighbor hay their extra open land, and there are possibilities for other enterprises. Dobrick and Macare feel that when they were launching their own farming operation, they benefited from having access to land through low-cost rental arrangements—now they’d like to pay it forward. After all, because of the topography and soil type present on the farm, they don’t see themselves raising vegetables on much more than the few acres that already make up the garden plots—that leaves a lot of real estate for other enterprises.

“It hasn’t been revealed to us yet what exactly we’re going to do,” says Dobrick. “We’re in the listening phase.”

They are also getting a chance to listen to other farmers in the region who are dealing with similar challenges and opportunities. Macare and Dobrick get together regularly with a group of other producers from a six-county area who direct-market what they raise. The group communicates via an e-mail listserv and holds “mini-conferences” every-other-year or so—the last one drew 50 to 60 people.

“It’s been really valuable to connect with other folks in this region,” says Dobrick. “I didn’t really know what we were getting into when we

8 IN PRACTICE h March / April 2022

Racing Heart Farm’s fields and hoophouses that grow vegetables for their 120-person CSA.

19

CONTINUED ON PAGE

& LIVESTOCK

5 Bar Beef— Cattle Hire Out to Restore the Land

BY HEATHER SMITH THOMAS

BY HEATHER SMITH THOMAS

Frank Fitzpatrick grew up at Silverado Canyon, California and went to college at Cal Poly at San Luis Obispo, graduating in 1971 with degrees in Animal Science and Ag Business. “While I was there, Newt Wright and I were exchanging ideas,” say Frank. “He grew up in Sandpoint Idaho and I met him when I was 14, before I went to college. He graduated two years ahead of me, and went to Idaho. He turned out to be my cattle partner. He and his neighbor imported the first Limousin and Simmental cattle in Idaho.

“I did my senior project on those two breeds. Then I started studying Jan Bonsma’s work and how to evaluate, measure and select cattle for functional traits. I followed him around the country and listened to what he had to say. I’ve had cattle since I was in high school, in FFA. I liked to rope, and ride; I love cows and I get along well with horses. I was bouncing around the country and meeting cattle people.”

It is those interests that has kept Frank firmly in the ranching and community and he continues to learn and adapt to the changing conditions of the ranching industry.

Adapting to Market Demand

Frank’s interest in cattle genetics led him to purchase some Barzona cattle. “A friend of ours went out of the Barzona business and several of us bought his Barzona cows. I bought seven Barzona cows in 1979 and hauled them to Oreana, Idaho to start my cattle business with these partners. We ranched there in Idaho for about five years, on the Snake River.

“I was home for the winter in 1982 and Pete Jamison called me on the phone and told me there was a guy from South Africa giving a talk in Buelton, Califonia and said I should come listen to him. I drove up there, and met Allan Savory while he still had black hair and was still young. I bought his book and read it about eight times.

“I’ve always used Allan Savory’s principles but the piece of ground I’m on now I’ve only been allowed to use holistically planned grazing for about the past four years. When it dries up, I feed the cattle every day, so I have a pretty good handle on the grass situation.” However, currently Frank has had to supplement feed his 600 head due to the drought.

“I have used 13 dedicated holistic programs in the last 40 years and all of them failed for the same reason; the people who owned the ground were trying to do it on a fiscal basis, and we are trying to change plant succession which is in an ecological time frame. People get tired of waiting for you to make progress,” Frank says.

For many years he and his family raised Barzona bulls for commercial

cattlemen in range country, but the Angus breed became popular and he quit selling bulls about 20 years ago. Instead, he started taking his cattle to packing houses, processing them, and selling them direct to consumers. “I found out they were worth more money that way than selling them as bulls,” Frank says.

Frank also sold meat through farmers’ markets since 2002 until COVID shut things down. Within two weeks the grocery store shelves were empty of meat and he couldn’t keep up with the orders coming in over the phone. “COVID was the best thing that ever happened to my business. I am just a small operation, and I sold 156 whole carcasses and halves last year and butchered another 63 head to package and sell in pieces,” he says.

He only raises and sells intact animals; all the meat he sells is from a bull or a cow. “We don’t castrate, vaccinate, dehorn, deworm or wean. The cows wean their own calves,” says Frank.

His Barzona cattle fend for themselves and can be a little bit on the wild side. His method of gentling them is to rope them when they are calves, tie them down and hold them down until they relax and their

Number 202 h Land & Livestock 9

CONTINUED ON PAGE 10

Frank Fitzpatrick

adrenaline level drops—a little bit like imprinting a foal so they no longer fear people but trust and respect people.

Grazing for Dollars

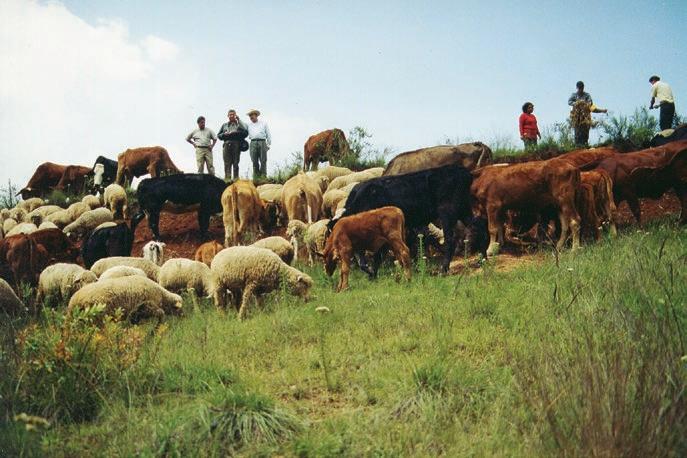

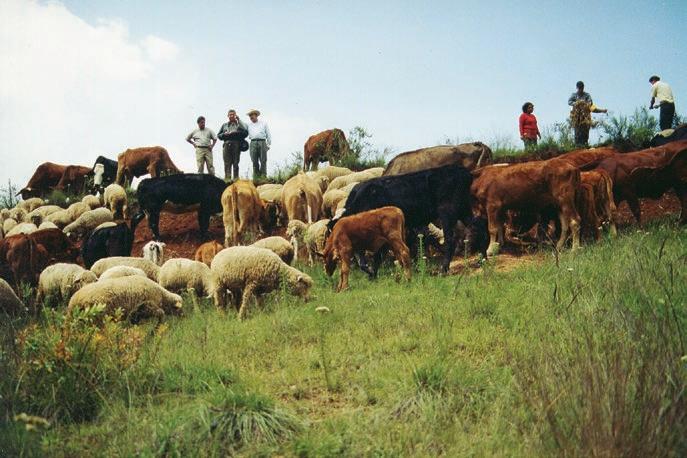

Frank has done planned intensive grazing for many years to improve the soil and pastures on his ranch, and now has people paying him to graze certain areas that need to regenerate the soil, get rid of invasive plants, reduce fire risk and restore native plant populations. “This is really exciting, to get paid by people to mow their weeds!”

Timing is important. The cattle eat non-native annual plants as they are beginning to sprout and grow—and trample the thick layer of old, dry mustard plants. The hoof action exposes the sprouting native grasses to sunlight and moisture so they can grow and take over the areas that were invaded by non-native plants. The non-native annual plants generally sprout first and crowd out the sparse native plants that were damaged by fire or earlier overgrazing. By grazing the annual plants early, then giving the area a rest, the native perennials have more chance to grow and restore the local ecosystem.

The pilot project involves a small portion of the TCA’s 2,000 acres of preserved open spaces that are spread across 17 sites in Orange County, and will show what grazing can do to restore the land. The cattle wear GPS collars that are programmed to facilitate an invisible (virtual) fence that keeps them in the area they need to be—without needing a real fence. If the cattle get near the invisible border, they’re warned with a beeping sound from the collar. If they step beyond that boundary, they receive a zap—like from an electric fence. Once they are trained to the virtual fence, they respect the invisible boundary and don’t venture across it when they hear the warning beep. The virtual fence can be moved where needed, to effectively move the cattle. “This makes planned grazing doable in any kind of terrain and in large areas,” says Frank.

“It’s only about 80% effective, however (some animals walk through the virtual boundary) but much better than any electric fence ever built. It would be impossible to move electric fences every day, in large pastures.” And wildlife would tear them down.

The University of California, Davis became involved with a project that uses his cattle to restore degraded land. “This is a big deal in California right now,” he says. Currently his cattle are part of a pilot project with the Transportation Corridor Agencies to show the good job that cattle can do.

Many people think cattle are bad for the land. “They hate cows because they’ve been fed a bill of goods that they are harmful,” Frank says, due to damage done from overgrazing in the past, on many of Orange County’s rolling hills. Fitzpatrick points out that the overgrazing and environmental degradation was due to human decisions. It’s not the cow; it’s the how. Properly managed, grazing is the best thing that can happen to keep the land healthy or restore degraded landscapes, mimicking nature. Native plant communities evolved with grazing. Herds of grazing animals moving over the land was what stimulated the plants, spread their seeds and fertilized them.

Frank’s small herd of Barzona bulls has been hired by the TCA to graze 23 acres next to Live Oak Canyon Road—a piece of land that the transportation agency is tasked with preserving as open space. This project will show how cattle can be used in a beneficial way. By moving the cattle around (with a high number in a small area for a short time), they help regenerate the soil and native plant communities. They eat plants that shouldn’t be there (reducing fire danger), and the soil benefits from the nutrients left by the cattle urinating and defecating. A period of rest before being grazed again enables the native plants to thrive.

“The only way planned grazing really works is if you are putting anywhere from 300,000 to a million pounds of animals on one acre of land. You need a lot of impact for a short time. Putting about 800 cows (or bulls) on that one acre, it is cheaper to herd them than to use fences. The virtual fence makes herding easier,” he explains.

Fitzpatrick

The pilot program is expected to last three years and Fitzpatrick is being paid $11,500 annually to graze his cattle on that piece three times each year. The TCA’s goal is to mitigate wildfire risk and help bring back some of the native riparian grasses and coastal sage scrub that support the threatened coastal California gnatcatcher and the endangered

10 Land & Livestock h March / April 2022

supplements the cattle with extra protein and supplies water and salt.

5 Bar Beef CONTINUED FROM PAGE 9

Frank’s Barzona bulls do well on sparse feed and he sells them as grassfed beef.

Frank’s ranch is on eastern edge of Orange County next to 13 million people.

Riverside fairy shrimp. TCA biologists will monitor the sites and collect data to use in planning restoration of some of their other conservation lands in the county.

“Everyone wants to just give me little bitty pieces of ground to see if this works, to eliminate fire danger, knock the brush and standing forbs down and eat the grass. It grows back prettier and nicer and people like it, but we really need much larger areas (like 6,000 to 7,000 acres) to move a larger bunch of cattle around on, and then people could actually see beneficial changes in plant communities and succession toward native perennial grass species in California,” says Frank.

The Savory Institute came out to monitor his ranch in 2021. “I have more variety and density of perennial grasses on this ranch than any other ranch that they looked at this year in California. Even though I am winning the battle, I feel like I’m not doing a very good job—because I don’t have big enough pieces to get enough cattle on to do it properly,” he says.

Solving Pollution Problems with Cattle

Many cities, including Irvine, have serious problems with weeds because the perennial grasses in areas of open ground have been destroyed. Weed control relies mainly on toxic chemicals. “Kim Konte lives in an Irvine neighborhood on the north end close to our old ranch. People there had kids that got sick and one is dying of brain cancer. Her kids were getting headaches from the contamination. She started a group called Nontoxic Irvine. She lobbied the city to discontinue use of glycophosphates (such as Roundup) in the city. Other people wanted to be involved and soon this movement included other cities, and they created some ‘nontoxic neighborhoods’ on city-controlled properties,” says Frank.

“About three years ago when Kim started this, a friend of mine introduced me to her and I told her this was a wonderful project but all she’s doing is putting a bandaid on a symptom and not addressing the real problem. Banning the chemicals is great but you haven’t healed the ground and it simply propagates weeds. Instead, we need to use systems that heal the soil and return the grasslands back to their natural state. She didn’t like what I said and spent about six months bad-mouthing me and then finally she realized that I was right.

“The city of Irvine was mad at her because they’d passed a law that you couldn’t use these chemicals and also passed a law that you can’t have any weeds in the city, and the cost of weed abatement had gone up exponentially. They’d been using a crew of eight guys to control weeds and now had 40 guys plus volunteers mowing and pulling weeds. It became a major problem. So now she’s working on some kind of natural amendment that will kill weeds and I told her that all she is doing is smearing the grease around and not cleaning it up, not fixing the problem.

“To do it right, people need to holistically manage the land and put fertility back in the soil and grow sustainable grass instead of weeds, and then let my cows eat it—which sounds a little self-centered. If you

talk to people about all the degradation going on in the world, very few of them understand what the real problems are. The main problem with our environment is cities, concrete and asphalt—and monocrop farming— because these things shut off the water cycle. We need to grow more grass!

“Another program I have going right now is in the city of Irvine—to graze 170 acres in the Great Park in downtown Irvine. This Park is part of the old El Toro Marine Base. In 2002, the Department of Defense sold the land to private interests to be developed into a park.”

Barzona Cattle

This breed was developed in the mountains and deserts of Yavapai County, Arizona, starting with some crossbred cattle owned by the Bard family. They wanted to develop a breed that could adapt to their rugged, rocky region with extreme temperatures, sparse rainfall, and sparse feed.

The Barzona is a medium-size beef animal— actual mature size varying somewhat with the environment. These cattle may be horned or polled. Barzona are red, but the color may vary from dark to light red, with occasional white on the underline or switch.

About 100 acres of this 170 acres in the park is now going to be deeded back to the Department of Defense and the Veterans Administration and they are building a veteran’s cemetery there. “It will be developed over a 20-year period,” says Frank. “So my plan was to start in one corner with the cemetery and holistically graze the rest of it. Then as they need more space for plots, just keep moving the fence. Within 20 years we can do a lot of good there, and probably convince someone that continuing to have a nice grassy field wouldn’t be a bad idea, for this city-owned piece.

Barzonas have a high degree of herd instinct (traveling and grazing together as a group) and are curious and intelligent. Females usually breed as yearlings to calve at two. With light birth weight, streamlined calves, they tend to calve easily without assistance and breed back year after year even under stressful conditions. Barzona bulls are hardy and vigorous, with high libido. They tend to reach puberty early and are useful throughout a long productive life. The breed does well in rough country and produces excellent beef under marginal conditions.

“I am trying to get them to pay for the fence and water. The biggest problem is that for many years Jet-A (a type of aviation fuel—extremely refined kerosene) was dumped there, since 1941, and now there’s a big pool of Jet-A about 10 feet under the ground.”

Previously, before the site could be developed for civilian use, the Department of the Navy (which oversees both Navy and Marine Corps) was required to clean up the contaminated soil. Some of the

CONTINUED ON PAGE 18

Number 202 h Land & Livestock 11

Frank’s Barzona cattle at work on Live Oak Canyon Road project.

Bar Cross Ranch— Exploring Production Possibilities on Wyoming Rangeland

BY HEATHER SMITH THOMAS

BY HEATHER SMITH THOMAS

The Bar Cross Ranch near Cora, Wyoming (a little town southeast of Jackson Hole) was historically two ranches--the Willow Creek Ranch and the Bar Cross Ranch, and is now owned by the Speath family and managed by Katie Scarbrough.

“Before the current ownership, the Bar Cross ranch was owned by the Blatt family. Before that, the Bar Cross was owned by John Perry Barlow, lead singer for the Grateful Dead. He was raised here on that ranch,” she says.

can determine which new practices can pencil out in both the short- and long-term to make a difference on the land in this harsh climate.

Transitioning Production Practices

The operation for many years was typical to the area, putting up hay in summer while the cattle were on the range, and grazing the hayfield aftermath in the fall. “The cows spent time on the uplands in the spring and then went on up to the forest permit in the summer. They came back to the foothills to graze again in the fall, with the grass freshened up by fall moisture, and then the cows were fed hay in the winter,” she says.

“We’ve tried to change that around, and today there’s not a cow on the place anymore; it’s all yearlings, and just here for summer grazing. We run yearlings for two reasons; one, we can get the density and impact we want to have on the land, and it’s easier to do that—and move them around as one group—than with cows and calves. Two, this country is not ideal for raising cattle, due to winter costs and having to feed hay for so many months—especially this winter, with hay prices so high,” Katie explains.

This is the second year the ranch has been running yearlings exclusively. “We’d gone through an awkward transition period in which we tried to run a certain number of cows and fill in with yearlings but then realized that if we were running multiple herds we were not achieving what we want to achieve,” says Katie. “The yearlings can be used (more effectively than cow-calf pairs) as a tool but are also the economic engine that drives this ranch. We are land stewards and the cattle are a tool, but they are also our main focus because they are our main enterprise. We need to be able to pay for what we want to do.”

the late 1920s, Jenkins had 15,000 acres and 2,500 head of cattle in the Upper Green River Valley.

John Perry’s mother, Miriam, and her husband, Norman Barlow were married in 1929 and moved a year later to the family’s Bar Cross Ranch to run it. Miriam and Norman had only one child, John Perry. He took over the ranching operations for the Bar Cross Ranch in Cora when his father suffered a stroke, and helped run the family ranch with his mother after Norman’s death in 1972. John Perry hosted the Grateful Dead band members at the Bar Cross in the 1970s and 1980s and was a songwriter for the group. In 1988, he sold the Bar Cross Ranch.

“The Speath family has owned the ranch for about four years,” says Katie. “Currently, both ranches are together with a combination of the forest permits on those ranches. We also obtained another Forest permit so we run cattle on about 25,000 acres of forest—directly north of the ranch and contiguous with the ranch,” Katie says.

With new ownership has come a strong interest in improving the range conditions and Katie has been tasked with bringing together a team that

This arid environment is challenging, grazing at high altitudes in dry conditions with sagebrush and bunch grasses. It’s a bit easier grazing the lower elevations on the meadows and brush ground. “Our current model is high-density frequent moves for the cattle, moving them every 8 to 12 hours in the meadows and not putting up any hay. We graze those meadows in the spring, which gives the brush ground a good chance for the grass to get started. We have the cattle spend the summer on the brush ground and then finish the fall grazing with a last pass through the meadows—more slowly but with heavier density. The cattle do a lot better on the meadows late in the season,” she says.

The first pass through the meadows, the grass is lush and green, growing rapidly; the plants are high in water content and protein, and not enough fiber. The cattle eat a lot (not enough fiber fill) and it goes through them too fast (loose feces). “But they like that soft lush feed, and when they go to the brush they are not as happy because they prefer the soft, easy-to-eat salad-bar type diet. When we put them in the brush ground they don’t want to be there!”

It takes some adjustment. “We are still trying to figure out how best to manage this, especially on the brush ground with native grasses. It is so dry here in the summers, at this altitude. Even by the end of June and

12 Land & Livestock h March / April 2022

Katie Scarbrough.

Team Photo (left to right): Katie Scarbrough, Brody Brown, Jason Spaeth, Mac McCormick, Delta McCormick.

early July, everything is drying out in this arid environment. This is truly high desert. I tell people that where I live is like a combination of New Mexico and Colorado (high country, but very dry),” Katie says.

“We are really struggling to make rotational grazing work in the uplands, using one herd at high density. With 2,000 head, you might move through a 1,000-acre pasture in three days. That’s how sparse the feed is. You don’t want to stay any longer with that many cattle or you would damage the plant communities. You don’t want to hit it too hard, especially these bunch grasses,” she explains.

“In the spring we let that grass get a good start and produce some biomass, then bite it off—a little bit after seed set, but hopefully before it gets too dry. We do get some fall freshening most years with a little fall

Focus on the People Part

Katie notes they try to implement all three legs of Holistic Management three-legged stool (social, environment, and economic). “One thing that I feel is not stressed enough is the balance,” says Katie. “Sometimes it’s actually bad to try to do the very best thing for your land, striving hard for regeneration. In doing that, you may sacrifice other things. You might think you should go out there and move those cattle every three hours, but if you did that, would you have any employees that would want to do it? Here, there’s not a tree on the place, the wind blows almost constantly, and the sagebrush is abundant. To move the cattle that often in these conditions is not socially sustainable!

“This is one thing we struggle with. We are also seasonal; our employees are here from May until November and only one or two of us are fulltime through winter. How do I motivate a new employee and get the most from that person? Are we doing our best for the landscape, the people and our pocketbook? I think sometimes the environmental leg of the stool gets stressed so much that we are too willing to sacrifice too much financially and socially, and that doesn’t work either.

“You can’t do it if you can’t pay for it, or do the work, and if you are subsidizing that work, it’s not real; why are you out there to begin with? This is part of the struggle in dealing with the vastness of these big landscapes—how to economically manage them and realistically assess this socially. If you ask someone to go check the steers, it might take them half a day to get to where those steers are and find them.

rain, so hopefully it grows a little more biomass, and then the snow comes through and lays it down. But it is so dry by the time we go in there in late June/early July that we are really having trouble getting the litter to break down. There are plant carcasses from the previous year, manure that’s years old; nothing is breaking down to help the soil.

“Someone once tried to tell me that it’s not brittle here because it snows once a year, but they need to come see it in July! So I am struggling to determine the best way to graze this, and wonder if I maybe should start coming into these pastures in the spring and then increase the rest-rotation. Right now I have 20% rest-rotation and maybe I should increase it to 25% and if a pasture gets grazed early in the spring it gets the next year off, and if it gets grazed in the summer it can be grazed by the next fall, etc.”

Sometimes these things must be figured out with trial and error, keeping in mind that every year might be a little different in terms of weather and moisture. It can be a moving target. “It’s especially challenging in our brittle environment, because it takes so long to see any positive changes and even the smallest mistake can cause catastrophic changes; it takes longer to recover,” Katie explains. Some bunch grasses almost do best if you leave them alone during the growing season and graze them in the fall/winter after they are mature and have gone to seed (when they are not set back by grazing), trampling the seeds into the soil, but it all depends on the individual situation. If there’s deep snow you won’t be able to graze it!

“Our forest permits are managed a little more traditionally. We are looking at options, to try to consolidate herds and not use season-long stocking. We are trying to work with the Forest Service to get some joint monitoring in place, in conjunction with our Conservation District and Game and Fish to create a baseline and then hopefully do a 3-year trial. We might be able to combine some herds, with the two permits,” she says.

The Forest Service’s operating instructions are not very flexible, however, which can be a huge problem. “And unfortunately for us, the rangers are stretched so thin that they don’t have enough time to be out on the landscape, let alone having these kinds of conversations, to provide ranchers with what they need, to be successful. The Forest Service

CONTINUED ON PAGE 14

Number 202 h Land & Livestock 13

Brody Brown and Delta McCormick moving cattle.

Foreman, Mac McCormick, riding the range.

Bar Cross Ranch

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 13

becomes simply an enforcer (range police) rather than innovative to do what’s best for the land,” says Katie.

“We are blessed in Sublette County, however, in terms of agencies working together. The project we are trying to do with the Conservation Districts, Forest Service, Game and Fish is a common occurrence in this county, where I will be working with three to four agencies on one project. This is wonderful. I’ve never been anywhere else that this has been the case; the various agencies normally argue and can’t get on the same page. So I have really been hoping that we can get something going on this, and effect some positive changes.

“All of these things have to be socially sustainable. We know they can pay, in terms of combining herds, etc. But moving one herd of yearlings within 20,000 acres in the forest may be challenging! It will be interesting to see what we can accomplish, and I am hopeful.

“So we are trying to work on some different projects like that. And on the ranch, doing what we are doing is so different that we are trying to work with several agencies and have a monitoring plan and data collection plan, starting with a baseline and where we want to move it to when these practices have been implemented. Anyone who wants to can come out and see what we are doing is welcome—whether they have questions or are just curious because they think we are crazy; they are all welcome.”

Consensus Building

Consensus Building is part of the social aspect of Holistic Management, sharing ideas. Some folks might think something won’t work, but then see that it might. “I think I’ve learned more, being on other peoples’ places and seeing what they do, than anything else I’ve ever done,” says Katie.

Jeff Goebel, an HMI Certified Educator has done some work with Katie on the ranch. “He calls his work consensus building. He helps us all work together,” says Katie.

“When I arrived at the ranch, the foreman had been here a long time, doing a very traditional ranch operation. It’s hard when ownership changes, new people are hired, and employees who have been there much longer than the current ownership don’t see eye to eye. This is very difficult, and also difficult from my position as ranch manager. I was ranch raised and I understand all the social dynamics. I understand the old guys with the opinions and I respect them immensely because a person can always learn things from them, too. I know some of my ideas may seem

outlandish, and I run them by my foreman and ask him how much he disagrees with them. Can we try it? Or tweak it? I tell him I am going to do it, but I want his opinion and input and I ask how he would do it, or what am I missing?

“All of these people are necessary components, to make it work. We need someone who knows the ranch intimately because they have been here so long—knows the seasonality, knows the changes.” He’s seen the variations over the years, the extreme weather events, and can create points of comparison.

“He has seen those, and knows how it affects the land, and how it affected the things that happened that year and in years afterward. He is so knowledgeable. At the end of the day, all that matters to our foreman is this ranch. That is what is in his heart. Everything he does is because he loves this place,” Katie says.

“It’s interesting, because the new owner also loves this place. He has a great passion for this ranch, yet these two people have vastly differing opinions on what is best for the ranch. Yet the root of it all is that they both love it. This is what’s so great about Jeff’s help. He does such a great job, and that makes my job easier. The owner, at the end of the day, is who sets the expectations regarding the return on his investment, and what he wants this place to do. My job is to take those goals and make them happen, and implement the system to make them happen.

“So in order to work with my foreman, who has been here forever, I tell him the goals and say that I think we can all agree to these goals; we all want this place to make money, we all want to do what’s best for the land, so how can we make this happen? I think Jeff does a really good job of helping get everyone on the same page because he filters a lot of the emotion out and gets everything out in the open.” Then everyone can more readily look at it impartially and maybe see some of the other peoples’ thoughts.