Hofstra University

Model United Nations Conference 2025

World Health Organization (WHO) Committee

Raven Bateman, Co-Chair

Matthew Friedman, Co-Chair

Dear Delegates,

Welcome to the World Health Organization! My name is Matthew Friedman, and I am incredibly excited to be one of your chairs at this conference. I grew up right here on Long Island and am now studying at Hofstra as a pre-medical studies major with a minor in biochemistry. I will begin working towards my MD at the Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra this coming fall.

Since the start of high school, Model UN has been part of my life making this my eighth year of MUN. I served as Secretary-General of last year’s HUMUNC, but I am pleased to retire back to the committee room this year. I have also been a delegate in every style of committee (GA, specialized, and crisis) and served as a Crisis Director (my favorite position so far). Within the club, I was elected Vice President for my second year and President for my third year.

In my free time, I love going for walks and reading. Two book recommendations for you all: The Emperor of all Maladies by Dr. Siddhartha Mukherjee and The Stormlight Archive by Brandon Sanderson. The first is a compelling biography of humanity’s centuries long struggle with cancer, and it is a must-read for anyone interested in medicine. The second, which is currently my favorite series, is an epic fantasy saga. I am actually running a D&D campaign set in its world which has been very fun. Oh, and finally? I am also a massive hockey fan, and Miracle is one of my favorite movies. Let’s go Islanders!

I am excited to read your position papers in the week leading up to the conference and to meet all of you in committee. It is my hope that we can create a debate atmosphere that is both fun and engaging, yet also informative. For those of you who are new to MUN or out of practice, don’t worry! There will be a MUN 101 session before the first committee session, and both Raven and I will be resources for you throughout the conference. If you have any questions about debate, you can ask us, and we will make sure you are following along. I am also happy to talk about college applications, the pre-med track, extracurriculars, (science) research, or your favorite fantasy epics during breaks in committee. If anyone has questions regarding research for our debate, you can also email me (cc hofstramodelun@gmail.com when you do) while preparing.

Warmly,

Matthew Friedman WHO Co-Chair mfriedman5@pride.hofstra.edu

Hello Delegates!

Welcome to HUMUNC and WHO! My name is Raven Bateman, Co-chair of this committee. I also serve as club secretary for Hofstra MUN. I am originally from California near San Francisco but am now a second year student here at Hofstra. I am pursuing a double major in biology and political science (and if I play my cards right, minors in chemistry, biochemistry, and global studies), as well as part of the direct entry BS/MS five-year program that Hofstra offers.

Although much of my high school experience was shaped by Covid, this is technically my sixth year doing MUN after doing it as much as I could through high school. I did GA all through high school and have participated in two crisis committees so far for Hofstra. For HUMUNC last year, I worked as back room staff for the Historical Crisis Committee, so this will be my first time chairing a committee — I am really looking forward to sharing this experience with all of you!

Outside of MUN, I am a lifelong dancer and love to bake in my free time. I have been a hula dancer (think Lilo and Stitch!) for nearly fifteen years and was competitive for about five of those years. While there is nowhere for me to dance competitively on the East Coast, I still dance hula whenever I am back in California. At Hofstra, I also dance with and choreograph for the non-audition team on campus. As for baking, my favorites to make are cookies and cupcakes so I can decorate them, but I have also dabbled in making larger cakes, breads, and other baked goods.

While I am newer to this than my Co-chair, I am super excited to learn along with you, starting with your position papers all the way through HUMUNC! I am looking forward to a fruitful and engaging debate on such important topics. Echoing what Matt wrote, we are both here for you throughout the weekend for everything MUN related and any questions you may have for either of us about college life and workload, favorite books, or anything else! You may also email either of us (as well as hofstramodelun@gmail.com) with any questions that come up before the conference itself.

I am looking forward to meeting all of you and having a wonderful time at HUMUNC!

Best,

Raven Bateman WHO Co-Chair rbateman1@pride.hofstra.edu

Introduction to the Committee

Founded in 1948, the World Health Organization (WHO) is an agency within the United Nations that has long worked to “champion health and a better future for all” by coordinating with 194 member states to respond to both continuing and emergent health issues. Within the WHO’s missions across the globe, collaboration can be found between groups ranging from “governments and civil society to international organizations, foundations, advocates, researchers and health workers”.1

The WHO’s efforts are guided by its Executive Board: a team of thirty-four delegates with public health qualifications. These scientists are elected to three-year terms and are responsible for designing an agenda for the World Health Assembly (they also provide a set of resolutions for the committee to consider, but we will not be following this protocol for the sake of our debate). With representatives from all 194 UN member states, the World Health Assembly is a forum for international dialogue that makes final decisions on WHO policies, manages the organization’s finances, and elects the Director-General to a five-year term. The DirectorGeneral, a position is currently held by Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, is the WHO’s “chief technical and administrative officer” and oversees its work.2

The COVID-19 pandemic brought the work of the WHO into the public spotlight, but it is working to improve global health through over 460 activities3 nearly 120 initiatives.4 From fostering climate resilient sanitation systems5 to combating microbial contamination of food,6 the World Health Organization has a broad jurisdiction that allows it to best champion health.

Topic 1: Healthcare for All

The WHO enshrines the “right to health” in its constitution, acknowledging this fundamental human right as one of its guiding principles. The right to health can best be defined as:

Every human being [able to obtain] to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health. Countries have a legal obligation to develop and implement legislation and policies that guarantee universal access to quality health services and address the root causes of health disparities, including poverty, stigma, and discrimination.7

In order to secure healthcare for all, the WHO must create a collaborative approach to global health that involves shared information, goals, operations, and more.8 We live in a globalized world where trade occurs over air and sea to connect distant regions. At the same time, many individuals are crossing local, national, and even international borders on a daily basis for travel, work, or to visit family. This means that pathogens traveling with them have the opportunity to pass between groups near and far, for disease knows no borders. No country exists in isolation, making collaboration between governments essential to containing public health threats. As such, it is up to the WHO to make sure members of the international community are prepared to address disease spread both inter-nationally and intra-nationally.

What might this entail? Figure 1 (below) shows a few possible scenarios for how international agencies can react to infectious disease spread. The figure illustrates how an office building in a major city might act as a hub for infection, allowing disease to spread from one town to another. A refugee camp might act as a hub in a similar manner since many people are concentrated there, but on a larger scale. Each example in the figure underscores opportunities for agencies to share information and responses to stop further spread when an outbreak occurs.

Figure 1: Infographic showing a selection of possible ways diseases can spread9

Health (In)Equity: Addressing Social Determinants

In addition to the availability of quality healthcare and personal lifestyle choices, socioeconomic factors are also significant to evaluate a population’s health outcomes. Referred to as “social determinants of health,” these factors broadly include education and income levels, housing, and food availability. The WHO defines these factors as “the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life.”10 How important are they? Whether globally or within a given country, those in better socioeconomic conditions obtain better health outcomes, on average. Dr. Bruce Link and Dr. Jo Phelan, two medical sociologists, first developed this Fundamental Cause Theory in 1995 to describe “a substantial causal role for social conditions as causes of illness.”11 In fact, the WHO estimates that the influence of social determinants is responsible for up to fifty-five percent of health outcomes.12

Breaking down populations by individual factors is another way to uncover significant health impacts. For example, one group of researchers in the United States found a ten-year chasm in life expectancy between those who completed a college degree and those who did not graduate high school (Figure 2). Furthermore, while a twenty-five year old female in the former group would be expected to live for another sixty-two years, a female of the same age in the latter group could only expect to live another fifty years on average.13

This pattern is not unique to the United States. One study that included over 600 people from seventy locations across the world concluded that each year of education led to a 1.9 percent reduction in mortality rate on average. The data revealed the same general pattern when

individual age categories were viewed — increased education levels had a consistently positive effect on mortality.14

Figure 2: Remaining life expectancy of twenty-five year old Americans by sex and education15

In another example examining access to healthy foods, researchers have found that living in a food desert (a place with low access to healthy food) had a significant effect on life expectancy, even when controlling for income. Individuals in low-income food deserts had a life expectancy of 75.5 years, but individuals in comparable income regions that were not food deserts had a life expectancy of 77.2 years. This pattern also held for high income regions. Those in high food access, high income regions were expected to live 80.2 years while those living in high income food deserts had a life expectancy of 79.4 years.16

If social determinants are not included in the creation of public health policies, it can foster unfair health outcomes. While some social determinants of health are at least partly outside

of an individual’s control, they impact health outcomes all the same, leading to disparities both within and between countries. Policy makers must remember these background factors, and healthcare guidelines should reflect the WHO’s declaration that “pursuing health equity means striving for the highest possible standard of health for all people and giving special attention to the needs of those at greatest risk of poor health, based on social conditions.”17

WHO at Refugee Camps: Protecting Our Most Vulnerable

According to the WHO, refugees and migrants “remain among the most vulnerable members of society”. Healthcare options are limited or absent during their travels, which can be arduous and further strain bodies. Reduced access to basic resources like food and clean water increases the potential strain and can leave them susceptible to waterborne diseases and contagious diseases, like measles. Treatment for chronic conditions that may already afflict them, as well as treatment for mental health disorders, may be delayed or out of reach for many refugees for varying lengths of time.18

Even if refugees stay healthy during their journey, they face other disadvantages. Xenophobia and restricted access to healthcare systems at their destinations might mean that refugees do not get healthcare that others receive. Poor health literacy of some refugees and medical resource shortages are other factors that can reduce refugees’ access to proper care.19

Refugee camps exist to help alleviate some humanitarian concerns of the estimated global refugee population of 6.6 million, as 4.5 million refugees (less than one out of every five refugees) currently live in camps organized by the United Nations. The remaining refugees live in “self-settled camps,” or more commonly, non-camp housing in urban locations. While managed camps provide important medical and humanitarian resources, they limit refugees’

autonomy and access to work compared to urban relocation.20 Managed camps frequently do not have sufficient energy supplies, enough food, or running water. Overcrowding further strains limited resources and fosters disease transmission. Many countries, like Kenya and Bangladesh, struggle to overcome these challenges while caring for refugees. Uganda is an example of one host country where resettlement programs provide a shining light, as refugees are provided with a chance to provide for themselves through supported agriculture.21

Resource Allocation: The Frontlines of Global Health Security

The UN’s Sustainable Development Goal 3 (more specifically, target 3.8) and the WHO’s UHC Billion plan, expanding the benefits of universal healthcare (UHC) to one billion more individuals, have begun to address unequal distribution of healthcare resources worldwide. Substantial progress was made during the period from 2000-2015, but this growth was slowed to a crawl since 2015 and was further hampered due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Data from 2021 reveals that over four billion people still do not have full access to “essential health services.”22

The WHO conducted a study assessing the coverage of infectious disease care across the world. This accounted for the quality, availability, and affordability of both treatment and care. Coverage was averaged between “the general and the most disadvantaged population” before being ranked on a unitless scale ranging from zero to one hundred. It was shown that Europe and the Western Pacific regions each had the highest level of access with matching average scores of eighty-two. Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean regions trailed behind with average scores of fifty-one and fifty-two, respectively. The national breakdown is summarized in

the map below (Figure 3), and exact national scores may be found on the WHO’s Global Health Observatory database.23

Part of the reason for this disparate access to care is a lack of healthcare providers in developing countries, for there is “no health[care] without a workforce”.25 For example, Europe and the Americas have the greatest physician density with 37.6 medical doctors per 10,000 people and 28.0 medical doctors per 10,000 people, respectively. Africa and Southeast Asia lag behind with 2.6 medical doctors per 10,000 people and 7.7 medical doctors per 10,000 people, respectively.26 Even accounting for nurses and midwives, who may take on a larger role in

healthcare in some nations, this pattern still holds (Figure 4).27 Regions with more healthcare providers align with regions experiencing greater access to infectious disease care.

Figure 4: Map showing per capita ranges of healthcare providers by country28

Another factor affecting health outcomes is the availability of medications, which can be affected by the strength of pharmaceutical industries of individual countries. In 2024, pharmaceutical companies from the United States represented thirty-nine percent of this industry, globally, while European firms represented twenty-five percent of the industry led by Britain, France, and Germany. Chinese pharmaceuticals enterprises accounted for an additional sixteen percent of the industry, and Japanese firms represented three percent. The regions of Africa, Central America, and South America each account for only one percent of the global industry, potentially leaving communities at a disadvantage.29

While pharmaceutical companies are essential in researching, designing, testing, and releasing new medications, the issue of guarding intellectual property to protect their profit on

novel drugs can impact access to these drugs. Countries at the forefront of the pharmaceutical industry have used these laws to strengthen their companies, often at the expense of wider access to crucial medications by citizens in less fortunate nations. Plans to reframe the intellectual property landscape to foster cooperation through new funding sources, or pooling information on highly infectious diseases, have been opposed by the United States and European Union in order to protect their industries, but a wiser, post-COVID world may be able to make more progress on this front.30

Healthcare for all? A Reflection on Failures and Successes From the COVID-19 Pandemic

The emergence of a novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China in 2019 and its subsequent proliferation across the globe was a tragedy that outlined many of the themes described above. While this committee will not directly explore pandemic responses, COVID-19 serves as a prime case study for delegates to consider. Data from the World Health Organization indicates a total of nearly 7.1 million deaths from the virus as of December 2024, but these fatalities have not been evenly distributed across geography or social demographics.31

Across the world, the impact of social determinants has been clear. In lower-income countries like India and Mexico, as well as higher-income countries like France and Sweden, poorer citizens in their respective societies suffered a greater COVID-19 disease burden (a composite of infection, mortality, and morbidity) than wealthier citizens. Even in Santiago, Chile, the capital of “a high-income country with high income inequality, an in-depth study of COVID-19-attributed mortality showed mortality rates per 10,000 were three to four times higher” among those in lower-income levels than high-income earners.32

Predictably, medical professionals treating COVID-19 patients on the front lines also experienced significantly elevated infection rates.33 Physical distancing, a key strategy in reducing disease spread, may be harder to achieve for disadvantaged groups, and it may even deny individuals vital access to food and nutrition. For example:

School closures increase food insecurity for children living in poverty who participate in school lunch [programs]. Malnutrition causes substantial risk to both the physical and mental health of these children, including lowering immune response, which has the potential to increase the risk of infectious disease transmission.34

Regional and international disparities were also spotlit by the COVID-19 pandemic for refugees. For example, extreme overcrowding and poor sanitation make the WHO’s transmission reduction policies, including hand washing and social distancing, “almost impossible to implement or enforce in refugee camps.”35

Another key area where disparities are present is in vaccine access. By the end of May 2021, more than a third of central and Western Europeans had received a COVID vaccination. Approximately half of all Americans and Canadians had received a COVID vaccine. However, no African country where data was available showed more than five percent vaccination rate and countries in Southeast Asia did not record a vaccination rate for COVID above twenty percent. At this urgent, early stage of the response to COVID, “it was reported that [eighty percent] of the world’s vaccines have gone to high income countries leaving only 0.3 [percent] for low-income countries.”36

Figure 5: WEF map showing COVID-19 vaccination rate as of May 24, 202137

Bloc Positions

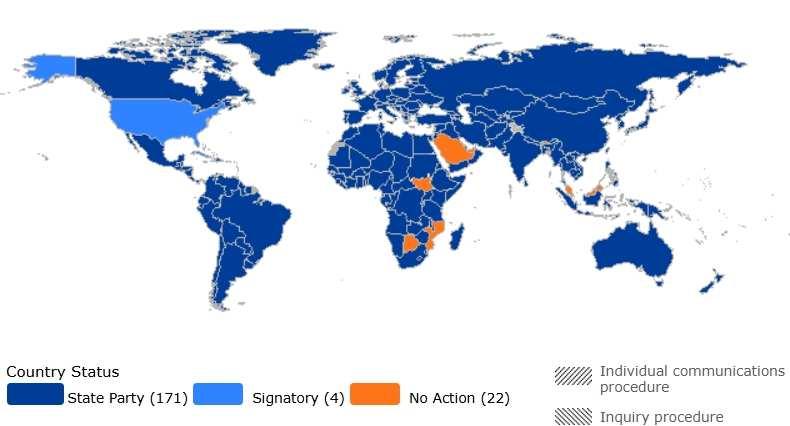

In addition to the WHO Charter, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) also enshrines health, both physical and mental, as a human right.38

There is wide acceptance of ICESCR, as UN Member States have ratified this treaty to become a state-party (fully bound by its content), with another four nations becoming signatories (with “an obligation to refrain, in good faith, from acts that would defeat the object and the purpose of the treaty”).39 While this topic revolves around a near universal goal, delegates will differ in regard to their nation’s preferred method of achieving this goal.

Figure 6: Ratification status of

As a general guideline, nations with a strong, developed healthcare system (like Canada, France, and Japan) will likely want to prioritize internal improvements to address social determinants, and those with less developed healthcare systems (like Angola and Bolivia) will want to recruit outside aid to bolster global health security. However, a myriad of other factors from culture to ideology may alter where a nation fits on this range. A good way to assess your country’s policy on the topic is to review what its own diplomats have said, any multilateral agreements it is a part of, and how it has historically voted on similar topics at the UN.

Guiding Questions

(1) What is the role of individual nations, and the WHO in providing healthcare for all?

(2) What guidelines and recommendations can be made to help nations counter healthcare inequity within their own borders? How can the international community help?

(3) How can the international community best protect refugee health? How can healthcare access in refugee camps be improved?

(4) What steps can be taken to improve access to healthcare resources across the world? Should the international community work to expand the number of providers? Revise intellectual property principles? If so, what steps should be taken?

(5) What lessons should the WHO take from the COVID-19 pandemic?

Topic 2: Catching the Red Queen

Inconspicuously beginning with one contaminated petri dish in September 1928, the advent of antibiotics has revolutionized medicine.41 First used in 1942 to treat a bacterial infection following a miscarriage, penicillin has quickly become one of the most consequential drugs in modern medicine.42 Although there is some evidence of antimicrobial treatments being used as far back as the 4th Century CE, the discovery of penicillin and other associated drugs — and the resulting mass production — has culminated in a drastic reduction in global illness mortality.43 Building on Paul Ehrlich’s pioneering of large-scale systematic testing procedures and the dogged persistence of Alexander Fleming, scientists have discovered a number of new antibiotics in the decades since penicillin first entered medical conversations.

Figure 7: Antibiotic discovery dates, basic information, and examples.44

Discovered the earliest, the β-lactam (pronounced “beta-lactam”) class of antibiotics are the most prescribed antibiotic globally, accounting for sixty-five percent of the total antibiotic market in 2013.45 Of this class of drugs, three penicillins, carbapenems, and cephalosporins — have received particular interest in a global study of global antibiotics between 2000 and 2018.46 Penicillins have been described as the “cornerstone” of antimicrobial treatments despite their declining viability as a permanent solution.47 The subsequent syntheses of what are known as second, third, and fourth generation penicillins each tackle this decline in their own way.

Carbapenems, though more widely used now, were discovered much later and were initially difficult to use because of their unproductive interactions with water (which makes up approximately sixty percent of the human body). However, today carbapenems are “typically reserved as an antibiotic of last resort” because their later discovery has left them less susceptible to resistance than other β-lactam antibiotics.48

Cephalosporins have recently emerged as one step further than even carbapenems, with five generations, each with different characteristics that enable them to target specific bacteria species, like those that cause pneumonia or meningitis, more effectively49. Specifically, βlactams attack targeted bacterium by preventing them from building a cell wall, impacting the structural integrity of the bacterial cell and causing it to lyse (explode) and die.50

The last of the four most studied antibiotics are fluoroquinolones, a sub-class containing several more specific antibiotics that are used to treat several bacterial infections including bronchitis, pneumonia, sinusitis, urinary tract infections, typhoid fever, and anthrax. Unlike the β-lactam class, fluoroquinolones target an enzyme class within bacterial cells called Type II DNA topoisomerases, or DNA gyrases. Hampering the function of DNA gyrases makes the bacteria

cell unable to copy its DNA for the next generation of cells or transcribe it into RNA to carry out any cellular functions. Although there have been some issues in the past with adverse side effects of fluoroquinolones, in general, the direct effects on human cells have been low because humans do not have DNA gyrases in their cells.51

Antibiotic Usage Worldwide

The use of antibiotics varies widely from country to country, with the discrepancy between high, middle, and low income countries and regions. In general, higher income countries like those in Western Europe had much higher levels of antibiotic usage than in lower income countries, like those in Sub-Saharan Africa. As of 2018, both Sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia posted average percentages of antibiotic usage (forty-two percent and fifty-one percent, respectively) that were not only comparatively lower than those of high income countries but also showed notable variation within the regions and with countries themselves. Each of these regions continued to track with global trends over the eighteen year study, but their consumption relative to each other is not radically different than it was at the turn of the century.52

In general, antibiotic consumption has increased by forty-six percent since the beginning of a study in 2000, one of the largest drivers of the blossoming issue of antibiotic resistance.53 In high-income countries, the problem originates with lofty amounts of annual antibiotic consumption. In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), particularly in Southeast Asia unlicensed antibiotics make their way into households. Each of these regional examples of antibiotic consumption are contributing to the phenomenon of antibiotic resistance, with faulty or unnecessary prescriptions of antibiotics.54

Figure 8: Change in antibiotic usage in populated areas of LMICs, 2000-201855

Globally, the world consumes 14.3 defined daily doses (DDD) of antibiotics per 1,000 people each day, as of 2018, a significant increase from 9.8 DDD in 2000.56 Of the six super regions separated in the study, the regions of Southeast Asia/SouthAsia/Oceania (9.0 DDD), Latin America/Caribbean (11.6 DDD), and Sub-Saharan Africa (11.8 DDD) had consumption rates lower than the global average, primarily a result of a higher concentration of LMICs in these regions. Notably, even high-income countries (which were additionally separated from the regional averages) in the Latin America/Caribbean region had only 14.2 DDD, still below the world average. All of the other high-income regions, as well as the super regions of Central Europe/Eastern Europe/Central Asia (16.5 DDD), North Africa/Middle East (23.6 DDD), and South Asia (15.5 DDD), posted averages well above the global average.57

Antimicrobial Resistance

As of 2009, drug-resistant bacteria were blamed for more than 88,000 deaths annually, just within the United States and EU.58 The World Health Organization states that antimicrobial resistance, or AMR, “occurs when bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites no longer respond to antimicrobial medicines,” thus becoming “difficult or impossible to treat.”59 When this happens, antibiotics previously used to reduce infections by killing bacteria are degraded by the bacteria they target, rendering them ineffective in managing disease.

Bacterial resistance to antibiotics can arise in several different ways, the most notable being genetic mutation and horizontal gene transfer (HGT). Genetic mutations, also known as chromosomal mutations, refer to the specific and spontaneous change in the bacterial genome that can result in antibiotics losing their effectiveness on a specific cell.60 While this drives much of antibiotic resistance, chromosomal mutations are relatively rare. Horizontal gene transfer, on

the other hand, is a feature of bacteria that allows them to “share genetic components with other bacteria,” spreading the beneficial genes coding for antibiotic resistance. HGT occurs through three main methods: transformation (incorporation of “naked DNA”), transduction (phagocytosis, or where the cell engulfs bacteriophages containing foreign DNA), and conjugation (direct transfer between two cells).61 Aligned with Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection, bacteria living in an environment where antibiotics are present will survive and reproduce more when they are resistant to the antibiotic than when they are not, propagating the beneficial gene giving them that resistance.

Figure 9: Three methods of horizontal gene transfer (HGT)62

As a result, the increase in antibiotic consumption worldwide has led to a correlated increase in antibiotic resistance. β-lactam antibiotics (including penicillin) are the most

commonly used antibiotic to treat human infections globally, and bacteria with the expression of β-lactamase as a resistance mechanism are becoming increasingly prevalent.63 β-lactamase is an enzyme that breaks down the β-lactam ring, the “the structural skeleton of any β-lactam antibiotic.”64 With their core structure broken down before it can affect the bacteria, β-lactam drugs lose their effectiveness. A concerning marker of this effect is indicated by the world’s increased reliance on carbapenems and cephalosporins, which have in the past been reserved only for those bacteria resistant to traditional antibiotics.65

Another specific example of this correlation between antibiotic use and resistance is present in a study conducted on several bacteria, including Staphylococcus pneumoniae, in the early 2000s. The study compiled its findings using a Spearman correlation, a representation of the “strength and direction of association between two ranked variables.”66 The study reported a Spearman correlation of 0.84 and 0.68 when considering S. pneumoniae with penicillin cephalosporins, respectively.67 Even twenty-five years ago, this indicated a high correlation between the increased use of antibiotics to target specific bacteria and the resulting increase in bacterial resistance to that antibiotic.68

Development of New Antimicrobials

With the extreme pace that the world is witnessing the growth of antibiotic resistance, finding timely solutions is imperative. Faced with a lack of new antibiotic discoveries in recent decades, scientists have turned to four main approaches to combating antibiotic resistance: antibiotic modification, combination therapy, targeted antibiotic delivery, and the use of antibiotic potentiators.69

Antibiotic modification mainly consists of two types of changes. Chemical modification involves an alteration of the structure of antibiotic itself, which for β-lactams means a change in the structure of any groups adjacent to the β-lactam ring itself. Bioconjugation, or the process of joining two different molecules together, involves the addition of new side chains to the existing β-lactam ring.70

Combination therapy, as the name suggests, involves a dual drug regimen, the two antibiotics having different biological targets in the bacteria that allow them to work together to “achieve synergistic bacterial killing.”71 β-lactams are commonly combined with a second class of antibiotics, aminoglycosides, that inhibit the translation of proteins in the bacteria while the βlactams continue to target binding in the cell wall. In addition, antibiotics have been combined with what are known as anti-virulence compounds, which “target the pathogen’s virulence pathways rather than pathways for its survival.”72 Virulence describes how sick a pathogen makes its host, so the addition of an anti-virulence drug to an antibiotic can serve to lower the mortality rate of an infection even if some resistance is present.

Targeted antibiotic delivery increases both the amount of antibiotic as well as the stability of that antibiotic once it is in the body. Increasing the amount of antibiotic present for a greater period of time drastically reduces the ability of any bacteria to survive the onslaught, therefore preventing the bacteria from developing resistance in the first place. Using different biologicallybased molecules as transports for the antibiotics, these enhanced delivery mechanisms “protect the antibiotic from enzymatic degradation…and also activate host immunity at the site of infection thereby enhancing pathogen killing.”73

Antibiotic potentiators are drugs that themselves do not exhibit antibiotic properties but restore or enhance the efficacy of other compounds that do exhibit antibiotic properties. When

using antibiotic potentiators, however, it is important to ensure that the potentiators maintain the same stability as the antibiotic without being toxic to the host or targeting human cells.74

75

While less common, novel antibiotics, or newly identified chemical compounds with antibacterial properties, are still being discovered today. but this is not the most reliable way to develop new drugs. Instead, researchers can now predict the structures of potential drugs using artificial intelligence. One such tool, called AlphaFold, allows researchers to predict the shape of

proteins, the main target of antibiotics, with great detail.76 When applied to bacterial proteins, the resulting structures provide researchers with enough information to probe for inhibitor binding spots and design new antibiotics.77 As with the development of any new drug, there is pressure to find an immediate solution for antibiotic resistance, but this is by no means a permanent solution, as these new antibiotics are not immune to resistance either.

Viral Evolution: A Whole Different Ball Game

There is an intense debate about whether viruses should be considered alive, since these infectious microbes lack the ability to replicate on their own but instead hijack the replication machinery of the cells they infect, usually killing the cell in the process and impacting the health of multicellular organisms. 78 Under the current Baltimore Classification System, there are seven classes of viruses, differentiated by the type of genetic material they have and the different processes they use to reproduce.79

Though both can function as infectious pathogens to humans, viruses and bacteria differ in several important ways. Most importantly, viruses are not cells and therefore do not respond to antibiotics. As previously discussed, most antibiotics target the cell membrane of bacterial cells, which they cannot do for viruses (which do not have a cell membrane). Moreover, attempts to use antibiotics to treat viral infections further contributes to antibiotic resistance because of unnecessary and improper use.81 Instead of responsive antibiotics, preventative vaccines are used to combat the incidence of viral infections. Like antibiotics, there are several different types of vaccines, generally categorized into traditional vaccines and mRNA vaccines. Traditional vaccines take several forms as well, but their method of prevention is the same: activate the body’s immune response so that the body is pre-prepared to fight an infection should it encounter that specific virus again.82

There are four general types of traditional vaccines: inactivated, live-attenuated, subunit/ recombinant/polysaccharide/conjugate, and toxoid. Inactivated vaccines introduce an inactive version of the virus and tend to require several doses over a lifetime to maintain the immunity it provides. Live-attenuated vaccines use a weakened version of the virus, which elicits a much greater immune response that can last a lifetime, but also must be kept cold in storage and transit and can pose a more significant risk to individuals who are immunocompromised.

Subunit/recombinant/polysaccharide/conjugate vaccines use only a section of the virus causing the disease, and while these are much safer for immunocompromised individuals, this type of vaccine can also require booster shots. Toxoid vaccines, instead of introducing any part of the virus itself, uses a toxin that it produces, training the immune system to target that harmful toxin instead of the virus itself.83

Messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines simply provide immune cells with instructions to recognize and attack the targeted virus. The body develops an immune response to the newly coded proteins, since no portion of the virus is introduced, making them much safer and much more efficient than any of the traditional vaccines.84

Figure 12: Comparison of traditional and mRNA vaccines.85

Unfortunately, much like bacteria, viruses can also evolve resistance. Viruses have large populations, short generations, and an extraordinary mutation rate that “allow viruses to rapidly evolve and adapt to the host environment.”86 Although mRNA vaccines are more susceptible to a decrease in effectiveness as a result of viral evolution, the broader and faster ability to alter or create entirely new mRNA vaccines allows humans to keep up with such rapid changes.

Vaccine Misinformation

Especially prevalent during the COVID-19 pandemic, but starting as early as the 1990s, misinformation about vaccines and their safety have impacted public reception and participation in vaccination campaigns. Although one of his suggestions about the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine had already been discredited by scientists, Andrew Wakefield falsely claimed to show that the vaccine caused autism in children, setting off a mass rejection of not only the MMR vaccine, but vaccines in general.87 Correlated or not, 2018 saw “gaps in vaccination coverage” that caused endemic measles to begin reemerging in places previously considered free of the disease.88

Fast forward to 2020 and COVID-19, the World Health Organization was forced to declare not only a pandemic but an “infodemic” of misinformation specifically related to the vaccines. Researchers identified three main themes, including “medical misinformation, vaccine development, and conspiracies.”89 Another study found that vaccine misinformation existed in many countries around the world in all different regions. In addition, a nearly one-third of participants believed that the mRNA vaccines would cause a permanent change in their genome, and only a slightly smaller percentage believed a false claim that was specific to their country.90

Along with addressing the issues of viral evolution worldwide, it is also extremely important to acknowledge the additional factors hampering the progress of global medicine. The WHO has run several vaccination campaigns in the past, but the success of these campaigns has depended on public opinion surrounding vaccines just as much as the organization of the campaign itself.

Global Inequity in Medicine

Although the WHO and various non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have committed to improving equal access to medicine worldwide, there is still a long way to go. Goal

Three of the United Nations’ seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is to “ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages,” once again indicating an obligation of all countries to move toward equal access to critical healthcare.91

However, in terms of both antibiotics and vaccines, the difference between high- and low-income countries is clear. Studies have concluded that “around 2 billion people globally have no access to essential medicines, particularly in” LMICs.92 With regard to antibiotic usage in particular, the regions of Sub-Saharan Africa and East Asia/Southeast Asia/Oceania had the lowest rates of antibiotic consumption, while North Africa/Middle East had the highest rates of consumption. In addition, high-income countries in each region showed marked increases in antibiotic usage compared to their super-region estimates.

It is clear that high-income countries have more access to these necessary drugs than the LMICs. But what is also concerning is the aforementioned potential overuse of antibiotics in those countries without strict regulations, many of which are also LMICs. With continual overuse comes a rapid increase in antibiotic resistance, which can return countries to high death rates without quick access to advancing medical technology.

Furthermore, vaccine rollout, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, again highlighted these global inequities. In July 2021, eighty-five percent of administered vaccines had gone to individuals in higher-income countries.93 At the same time, over seventy-five percent had been administered in just ten countries. The WHO also notes that twenty-five million children were not up-to-date on critical vaccines in 2021, a number that rose from approximately

nineteen million in 2019.94 Healthcare is a human right for all people, so it is critical that these disparities are addressed.

Bloc Positions

Antibiotic resistance, viral evolution, and the spread of pathogens of all kinds are issues that affect all countries. While the effects of such issues may be seen more in some places than in others based on factors like income and regulation, the need for a coordinated global medicine movement is as important for one country as it is the next.

That being said, it is inevitable that these factors will impact the ways in which different countries go about tackling the problem within their own borders. Although profits generated by domestic pharmaceutical companies are beneficial to national economies, countries pioneering antibiotic research and the development of vaccines need to understand that there must be a balance between internal economics and external health. On the other hand, countries with low access to critical healthcare must not only prioritize access to these medicines, but specifically, responsible access.

While this committee will not directly assess the global COVID-19 response, looking into your country’s healthcare resources and how they were deployed following the coronavirus outbreak may give some insight into your country’s healthcare response priorities.

Guiding Questions

(1) What can the WHO do to help the medical field slow the pace of microbial evolution?

(2) Should antibiotic/antiviral use be limited to protect efficacy, and if so, how can the population be kept healthy?

(3) How can the WHO support the development of new treatments? Should there be a focus on the discovery of novel compounds, alterations to existing antibiotics/antivirals, or development of combination regimens?

(4) In an era of growing vaccine-denialism, how can the WHO improve the public’s confidence in this vital public health tool?

Endnotes

1 World Health Organization. (2024). About WHO. https://www.who.int/about

2 World Health Organization. (2024). Governance. https://www.who.int/about/governance

3 World Health Organization. (2024). Activities. https://www.who.int/activities

4 World Health Organization. (2024). Initiatives. https://www.who.int/initiatives

5 World Health Organization. (2024). Boosting climate-resilient water, sanitation and hygiene services. https://www.who.int/activities/boosting-climate-resilient-water--sanitation-and-hygiene-services

6 World Health Organization. (2024). Assessing microbiological risks in food. https://www.who.int/activities/assessing-microbiological-risks-in-food

7 World Health Organization. (2023, December 1). Human rights. https://www.who.int/news-room/factsheets/detail/human-rights-and-health

8 World Health Organization. (2020). Stronger collaboration, better health: 2020 progress report on the global action plan for healthy lives and well-being for all. World Health Organization. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/334122 License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO

9 Ibid.

10 World Health Organization, 2024. Social Determinants of Health. https://www.who.int/healthtopics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1

11 Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. (1995). Social Conditions As Fundamental Causes of Disease. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 80–94. https://doi.org/10.2307/2626958

12 World Health Organization. (2024). Social Determinants of Health. https://www.who.int/healthtopics/social-determinants-of-health

13 Hummer, R. A., & Hernandez, E. M. (2013). The effect of educational attainment on adult mortality in the United States. Population bulletin, 68(1), 1. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4435622/

14 Balaj, M., Henson, C. A., Aronsson, A., Aravkin, A., Beck, K., Degail, C., ... & Gakidou, E. (2024). Effects of education on adult mortality: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpub/article/piis2468-2667(23)00306-7/fulltext.

15 Ibid: Hummer & Hernandez.

16 Massey, J., Wiese, D., McCullough, M. L., Jemal, A., & Islami, F. (2023). The Association Between Census Tract Healthy Food Accessibility and Life Expectancy in the United States. Journal of Urban Health, 100(3), 572-576. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s11524-023-00742-x.pdf.

17 World Health Organization. (2024). Social Determinants of Health. https://www.who.int/healthtopics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_3.

18 World Health Organization. (2022, May 2). Refugee and migrant health. https://www.who.int/newsroom/fact-sheets/detail/refugee-and-migrant-health

19 Ibid

20 USA for UNHCR. (2021, April 6). Refugee Camps Explained. https://www.unrefugees.org/news/refugee-camps-explained/

21 Malteser International. (2024). Refugee camps: challenges and assistance on site. https://www.malteserinternational.org/en/current-issues/refugees-and-displacement/refugee-camps.html

22 World health statistics 2024: monitoring health for the SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240094703; World Health Organization. (2023, October 5). Universal Health Coverage (UHC). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/universal-healthcoverage-(uhc)

23 World Health Organization. (2022). UHC Service Coverage sub-index on infectious diseases. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/uhc-sci-components-infectiousdiseases

24 Ibid.

25 World Health Organization. (2014, November 8). A universal truth: No health without a workforce. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/hrh_universal_truth

26 World Health Organization. (2024). Medical doctors (per 10 000 population). The Global Health Observatory. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/medical-doctors-(per10-000-population).

27 Crisp, N., & Chen, L. (2014). Global supply of health professionals. New England Journal of Medicine, 370(10), 950-957. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMra1111610.

28 Ibid.

29 Citeline Clinical. (2024). Pharma R&D Annual Review 2024 Infographic. https://www.citeline.com//media/citeline/resources/pdf/infographic_pharma-rd-2024.pdf.

30 Ding, J. (2020, May 17). Rethinking pharmaceutical IP in a post-pandemic world. Harvard International Review. https://hir.harvard.edu/rethinking-pharmaceutical-ip-in-a-post-pandemic-world/.

31 World Health Organization. (2024c). WHO COVID-19 dashboard. https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/deaths.

32 COVID-19 and the social determinants of health and health equity: evidence brief. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240038387 License: CC BYNC-SA 3.0 IGO

33 COVID-19 and the social determinants of health and health equity: evidence brief. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240038387. License: CC BYNC-SA 3.0 IGO

34 Abrams, E. M., & Szefler, S. J. (2020). COVID-19 and the impact of social determinants of health. The Lancet. Respiratory medicine, 8(7), 659–661. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30234-4

35 Saifee, J., Franco-Paredes, C., & Lowenstein, S. R. (2021). Refugee Health During COVID-19 and Future Pandemics. Current tropical medicine reports, 8(3), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40475-02100245-2

36 World Economic Forum. (2021, June 29). Accelerating vaccine rollouts to reach everyone. Health and Healthcare Systems. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/06/how-to-accelerate-vaccine-rollouts-toreach-everyone/

37 Ibid.

38 Bhabha, J. (2016, December). Half a century of a right to health?. United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/chronicle/article/half-century-right-health

39 United Nations. (n.d.). United Nations Treaty Collection. https://treaties.un.org/pages/overview.aspx?path=overview%2Fglossary%2Fpage1_en.xml.

40 UNHCR Office of the High Commissioner. (2023, February 21). International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Status of Ratification Interactive Dashboard. https://indicators.ohchr.org/

41 Markel, Howard, Dr. "The Real Story Behind Penicillin." PBS News, 27 Sept. 2013. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/health/the-real-story-behind-the-worlds-first-antibiotic

42 Yale Medicine Magazine. "Fulton, Penicillin and Chance." Yale School of Medicine, 2000. https://medicine.yale.edu/news/yale-medicine-magazine/article/fulton-penicillin-and-chance/

43 Aminov, Rustam I. "A Brief History of the Antibiotic Era: Lessons Learned and Challenges for the Future." Frontiers in Microbiology, 2010.

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/microbiology/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2010.00134/full

44 Brunning, A. (2014, September 8). A Brief Overview of Classes of Antibiotics. Compound Chem. https://www.compoundchem.com/2014/09/08/antibiotics/

45 Thakuria B, Lahon K. The Beta Lactam Antibiotics as an Empirical Therapy in a Developing Country: An Update on Their Current Status and Recommendations to Counter the Resistance against Them. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013 Jun;7(6):1207-14. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/5239.3052. Epub 2013 Jun 1. PMID: 23905143; PMCID: PMC3708238. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3708238/

46 Browne AJ, Chipeta MG, Haines-Woodhouse G, Kumaran EPA, Hamadani BHK, Zaraa S, Henry NJ, Deshpande A, Reiner RC Jr, Day NPJ, Lopez AD, Dunachie S, Moore CE, Stergachis A, Hay SI, Dolecek C. Global antibiotic consumption and usage in humans, 2000-18: a spatial modelling study. Lancet Planet Health. 2021 Dec;5(12):e893-e904. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00280-1. Epub 2021 Nov 12. PMID: 34774223; PMCID: PMC8654683. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanplh/article/PIIS25425196(21)00280-1/fulltext.

47 Yip DW, Gerriets V. Penicillin. [Updated 2024 Feb 20]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554560/.

48 Armstrong T, Fenn SJ, Hardie KR. JMM Profile: Carbapenems: a broad-spectrum antibiotic. J Med Microbiol. 2021 Dec;70(12):001462. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.001462. PMID: 34889726; PMCID: PMC8744278. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34889726/.

49 Bui T, Patel P, Preuss CV. Cephalosporins. [Updated 2024 Feb 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551517/.

50 Ibid: Armstrong T, et al.

51 LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012-. Fluoroquinolones. [Updated 2020 Mar 10]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547840/.

52 Ibid: Browne AJ, et al

53 University of Oxford. (2021, November 16) "Global Antibiotic Consumption Rates Increased by 46 Percent Since 2000.". https://www.ox.ac.uk/news/2021-11-16-global-antibiotic-consumption-ratesincreased-46-percent-2000.

54 Ibid: Browne, AJ (2021).

55 Ibid.

56 Ibid: University of Oxford (2021).

57 Ibid: Browne, AJ (2021).

58 Aminov, Rustam I. "A Brief History of the Antibiotic Era: Lessons Learned and Challenges for the Future." Frontiers in Microbiology, 2010. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/microbiology/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2010.00134/full

59 "Antimicrobial Resistance." World Health Organization, 21 Nov. 2023. https://www.who.int/newsroom/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance

60 National Research Council (US) Committee to Study the Human Health Effects of Subtherapeutic Antibiotic Use in Animal Feeds. The Effects on Human Health of Subtherapeutic Use of Antimicrobials in Animal Feeds. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 1980. Appendix C, Genetics of Antimicrobial Resistance. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK216503/

61 Habboush Y, Guzman N. Antibiotic Resistance. [Updated 2023 Jun 20]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513277/

62 Noori, Fahad & Latif, Muhammad & Hamdani, Syed & Babar, Mustafeez. (2024). Bacteriophage Therapy in GIT Infections – A Clinical Review. NUST Journal of Natural Sciences. 9. 1-17. 10.53992/njns.v9i2.163.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/382981597_Bacteriophage_Therapy_in_GIT_Infections_A_Clinical_Review

63 Yip DW, Gerriets V. Penicillin. [Updated 2024 Feb 20]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554560/

64 Thakuria B, Lahon K. The Beta Lactam Antibiotics as an Empirical Therapy in a Developing Country: An Update on Their Current Status and Recommendations to Counter the Resistance against Them. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013 Jun;7(6):1207-14. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/5239.3052. Epub 2013 Jun 1. PMID: 23905143; PMCID: PMC3708238. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3708238/

65 "Antimicrobial Resistance." World Health Organization, 21 Nov. 2023. https://www.who.int/newsroom/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance.

66 "Spearman's Rank-Order Correlation." Laerd Statistics, https://statistics.laerd.com/statisticalguides/spearmans-rank-order-correlation-statistical-guide.php Accessed 14 Nov. 2024.

67 Goossens, H., Ferech, M., Vander Stichele, R., & Elseviers, M. (2005). Outpatient antibiotic use in Europe and association with resistance: a cross-national database study. The Lancet, 365(9459), 579-587. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140673605179070

68 Ibid

69 Narendrakumar Lekshmi , Chakraborty Medha , Kumari Shashi , Paul Deepjyoti , Das Bhabatosh. "βLactam potentiators to re-sensitize resistant pathogens: Discovery, development, clinical use and the way forward." Frontiers in Microbiology, 2023. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/microbiology/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2022.1092556.

70 Ibid.

71 Ibid.

72 Ibid.

73 Ibid.

74 Ibid.

75 Ibid

76 Ruth Nussinov, Mingzhen Zhang, Yonglan Liu, Hyunbum Jang, AlphaFold, allosteric, and orthosteric drug discovery: Ways forward, Drug Discovery Today, Volume 28, Issue 6, 2023, 103551, ISSN 13596446, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2023.103551

77 Lefurgy, S. T. (2007). Complementation strategies applied to drug discovery and enzymology (Order No. 3285113). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I. (304859633). Retrieved from https://ezproxy.hofstra.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertationstheses/complementation-strategies-applied-drug-discovery/docview/304859633/se-2

78 Segre, J. (2024, November 15). Virus. Genome.gov https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/Virus

79 Louten J. (2016). Virus Structure and Classification. Essential Human Virology, 19–

29. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-800947-5.00002-8

80 Dutta, J., Goswami, S., & Mitra, A. (2020). COVID-19 and Emerging Environmental Trends: A Way Forward (1st ed.). CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003108887

81 Kern, C. (2023, May 10). Antibiotics: Not always the answer. Mayo Clinic Health System. https://www.mayoclinichealthsystem.org/hometown-health/speaking-of-health/3-reasons-whyyou-did-not-receive-antibiotics-from-your-provider

82 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, August 10). Explaining how vaccines work. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/basics/explaining-how-vaccines-work.html

83 US Department of Health and Human Services. (2022, December 22). Vaccine Basics. Immunization. https://www.hhs.gov/immunization/basics/types/index.html

84 Ibid.

85 Vanderbilt University Medical Center. (2020, November 16). How does a mRNA vaccine compare to a traditional vaccine?. Institute for Infection, Immunology and

Inflammation. https://www.vumc.org/viiii/infographics/how-does-mrna-vaccine-compare-traditionalvaccine

86 Stern, A., & Andino, R. (2016). Viral Evolution: It Is All About Mutations. Viral Pathogenesis, 233–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-800964-2.00017-3

87 Davidson M. (2017). Vaccination as a cause of autism-myths and controversies. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 19(4), 403–407. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2017.19.4/mdavidson

88 World Health Organization. (n.d.). A brief history of vaccination. Newsroom. https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/history-of-vaccination/a-brief-history-ofvaccination

89 Skafle, I., Nordahl-Hansen, A., Quintana, D. S., Wynn, R., & Gabarron, E. (2022). Misinformation About COVID-19 Vaccines on Social Media: Rapid Review. Journal of medical Internet research, 24(8), e37367. https://doi.org/10.2196/37367

90 Porter, E., Velez, Y., & Wood, T. J. (2023). Correcting COVID-19 vaccine misinformation in 10 countries. Royal Society open science, 10(3), 221097. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.221097

91 United Nations. (n.d.). Goal 3. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal3.

92 Chattu, V. K., Singh, B., Pattanshetty, S., & Reddy, S. (2023). Access to medicines through global health diplomacy. Health promotion perspectives, 13(1), 40–46. https://doi.org/10.34172/hpp.2023.05

93 World Health Organization. (n.d.). A brief history of vaccination. Newsroom. https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/history-of-vaccination/a-brief-history-ofvaccination.

94 United Nations. (n.d.). Goal 3. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal3.