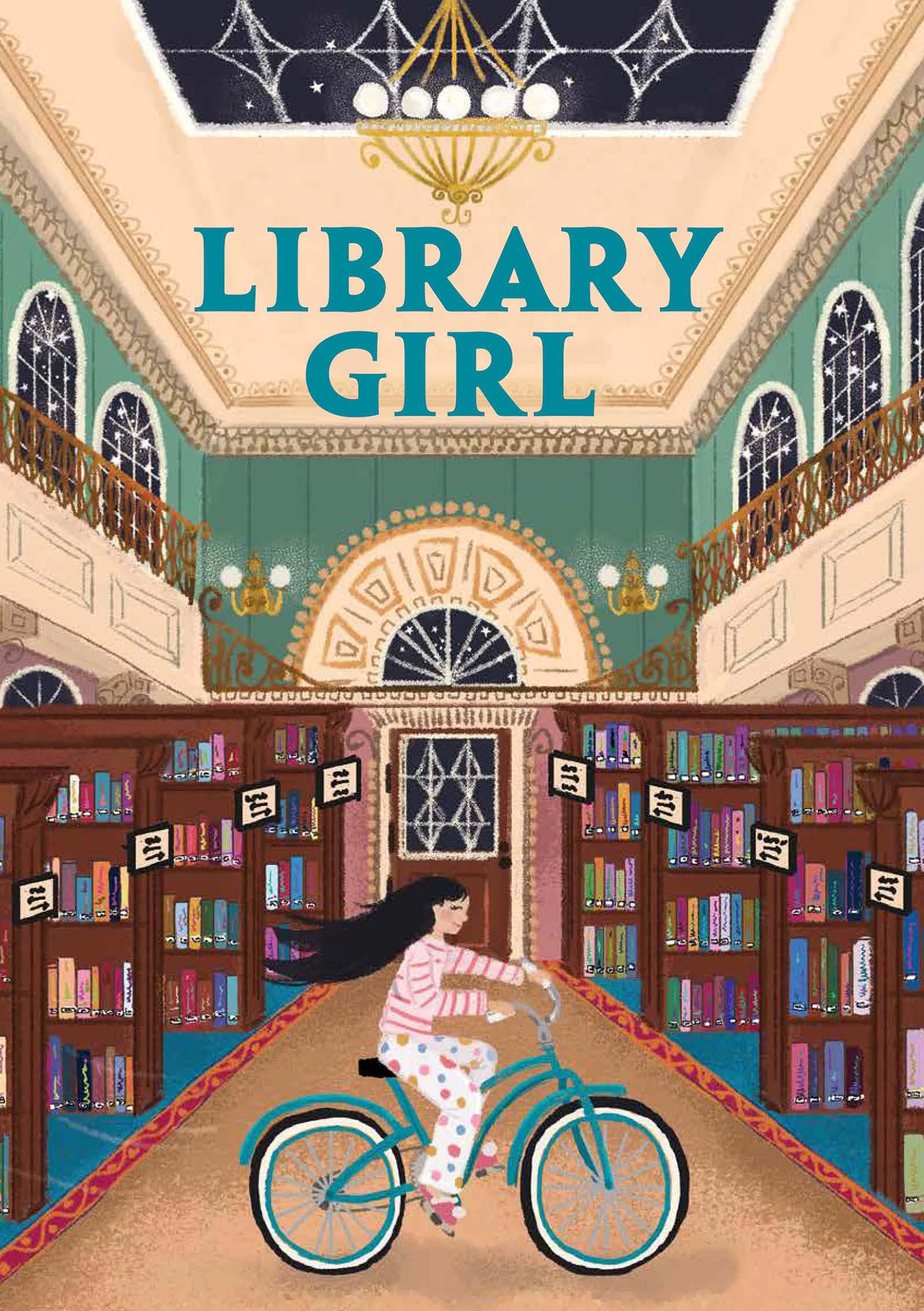

Library Girl

FOUND

It was a lovely crisp day in October. Doris, Taisha, Jeanne-Marie and Lucinda would never forget it. They all worked in the children’s department in the main branch of the Huffington Public Library, except Lucinda, who worked in reference. It was a lovely library, with cornices and balconies and scrollwork aplenty, in a lovely redbrick building in a lovely old downtown with Indiana’s first pedestrian open-air mall, built in 1894. Above the library was a charming small museum. It was free. The library sat on a city street corner across from a beautiful green park. The park was surrounded on three sides by enormous old Victorian mansions, all in gray clapboard and known as the Gray Ladies. From the floor-to - ceiling windows in the front of the library you could see into the middle of the park, where there was a duck pond so the ducks would have somewhere to go and toddlers would have somewhere to sail their toy boats. And in all four corners of the park were huge stone

fountains that people tossed pennies into to make wishes. And then once a month the pennies were collected and given to the humane society. Huffinton was full of such kindness and was just as picturesque as could be.

The adult section of the library, which included both the stacks and periodicals, with its large reading chairs, was also entirely walled in floor-to-ceiling windows, so that the library was nice and light and bright. Inside, the books were kept in neat rows. The bookshelves themselves were made of real oak. The library had a woody, faintly musty old-booky smell that was most inviting. Even if you weren’t a reader, it was a fine place to hang out.

The particular morning this story begins, the one that the four librarians would never forget, Lucinda happened to be in the office of the children’s department because she had brought a big box of homemade donuts for the children’s librarians. She was trying to up her game baking-wise and often brought the children’s librarians baked goods. She had tried to bring them to the librarians in the adult department, but they were all on weird diets, macrobiotic and keto and DASH and such, as grown-ups often are. The children’s librarians, on the other hand, recognized a good cupcake when they saw

one and didn’t let it go to waste. In this way did Lucinda become tight friends with Doris, Taisha and JeanneMarie, even though usually they excluded anyone who didn’t reread Elizabeth Enright at least once a year.

The librarians had put on a pot of coffee and were having a cup each while savoring jelly, chocolate dip and salted caramel donuts.

“I really think these are the best,” said Taisha, waving around a salted caramel.

“Oh no, you can’t beat a good chocolate dip,” argued Doris.

“Mmmmm,” said Jeanne- Marie, on her second jelly donut and not wanting to waste words when she could be chewing.

It was at that moment that they heard it.

“What was that?” asked Lucinda, who was perhaps the most alert because she wasn’t having a donut, having had two for breakfast at home already.

The others had to stop chewing and concentrate.

“It sounds . . . ,” said Taisha, “like a baby’s cry.”

“Oh no,” said Doris. “It couldn’t be. The library doesn’t open for another hour.”

“Perhaps someone who works in the adult department brought their baby,” suggested Jeanne-Marie.

“Who in the adult department even has a baby?” asked Taisha.

“Well, there’s that new young man who is always putting books away in the wrong places,” said Lucinda, who, unlike the others, was in on the gossip from the adult department to a small degree. It was only to a small degree because the adult librarians knew she fraternized with the children’s librarians and they weren’t having it.

“Does he have a baby?” asked Doris.

“He might,” said Lucinda. “He often comes to work with what looks like spit-up on his collar.”

“It could be his own,” said Jeanne-Marie. “Spit-up, that is.”

“It could indeed,” said Lucinda.

“Or something else,” said Doris. “He could be a dribbler. Mr. Pennysworth was a dribbler.”

Mr. Pennysworth was Doris’s ex-husband. She referred to him by his last name to “put some distance between us name-wise,” as she had explained to the others the first seven hundred times she had done this.

The women resumed their eating, but they could not get the sound of the baby crying out of their ears.

Now it is time to give you the sad news that all four of these librarians had wanted to be mothers and for tragic

reasons were unable. When they heard a baby cry it was like knives to their hearts. So one by one they put down their donuts and looked sadly into space, thinking of what might have been.

“All right,” said Doris finally, after they had stood frozen in time for a bit, each mourning her individual loss. “Enough. Let’s go find it. Whosever baby it is, they aren’t doing much for it. Listen to that crying.”

“I think I have a teddy bear somewhere here in the office,” said Doris, looking around the room. “Ah yes, here.”

“That baby is too young for a teddy bear,” said Taisha, who had so many young relatives that she knew to the month how old a baby was just from the sound of their cry. “That cry is a newborn cry.”

“That cry is a hungry cry,” said Jeanne-Marie, who had no young relatives so this was just a guess.

“Whatever it is, we must find it and relieve its distress,” said Lucinda. “Bring the teddy bear, Doris, but don’t expect much.”

“It may provide some small comfort,” said Doris hopefully, and the four of them marched through the children’s department, preparing to storm the fortress of the adult stacks. But before they even got to the door of

the massive children’s room, they stopped. The crying, which had been before them, was now behind them.

“That baby is in here,” said Taisha in surprise and a little alarm.

“What is a baby doing in here?” asked Doris. “And who would even dare come in here? We aren’t open yet. And the adult librarians have no business coming in without our permission before we are even open.”

“Leaving babies sprinkled about,” agreed Taisha.

“The thing is,” said Lucinda, trying to keep them all on track, “the thing is to find the baby.”

Up and down the stacks the four women went, each taking a different row. And perhaps it is a good time to tell you what they looked like so you can tell them apart. Doris was short and plump. She looked like a saltshaker. I cannot even tell you why exactly, except that she had pleasing lines and porcelain skin. She always wore midi dresses, which made her look as if she came from a different era. If she’d been taller or thinner she would have looked more modern, but a short, stout woman in a midi dress gives off a vintage vibe. She had an old-fashioned perm as well, so that her slightly graying mousy brown hair also looked from an earlier era. No one wore their hair that way anymore. She had

started to do so ever since ditching Mr. Pennysworth. In her reading she had eclectic taste. Of course she loved children’s books, but she also loved cozy murder mysteries where no one took the murders too seriously and everyone could always be found at four o’clock having a good cup of tea and an iced bun. She didn’t know what an iced bun was, but it always sounded delicious.

Lucinda looked like a raven. She had black hair that came past her shoulders, which, unlike many middle-aged women, suited her. Her nose was long and a bit bent under but not in a scary witch way. More in an interesting woman way. She might have been hired to tell fortunes, she had that kind of look, which was coupled with knowing eyes and a general air of command. She wore midi dresses, too, but they were always of lovely flowing fabric and she wore them with clunky heeled pumps. They did not make her look like a saltshaker. She looked wildly romantic but refined. And knowledgeable, as a reference librarian must be. She liked fiction by women writers and tidy short stories. She liked good nonfiction where the writers kept themselves out of the telling. She had read an entire encyclopedia series up to and including the letter Z. When you asked her a question she rarely had to look it up.

Taisha had a complexion so soft and smooth it was like a bar of triple-milled soap but the color of twilight. Doris envied it and asked her what creams she used. Doris was a great lover of skin creams. She had thirty- seven jars of night cream alone. But Taisha said you had to be born with such skin, you could not acquire it. She had a lovely froth of black hair around her head like moss. She had a beautiful face and eyes that went right to the point. She usually wore dangling earrings from exotic trips she had taken. She alone of the four of them could pull off such earrings. She wore pants to work mostly, although sometimes a dress or skirt. Whatever she wore looked perfect, and yet she wore it as if she didn’t really care, and her eyes carried the slightly wild look of those who have an appreciation and recognition of the absurd. She read all kinds of things. She loved children’s books best and had read almost every one in the children’s library. But her specialty was picture books. She did the library displays because she had the most artistic flair, and she did the story time because the thing she loved most was reading books aloud to children. She would have read them aloud to adults if they’d let her. She felt reading to others was a lost art. To be able to do so was a gift. That was why they called

talent a gift. Not because it was given to you but because it was something you were able to give to others.

Jeanne-Marie was thin and spiky and very Frenchlooking, as was only natural as she was French. Her face was all angles, cheekbones and nose and thin lips as if she’d been made out of twigs. She looked worried all the time even when she wasn’t, as if her face didn’t know how to do anything else. Everything about her said French, from her well- cut, well- chosen clothes to her flawless makeup and jewelry. Only her hair wouldn’t behave in a neat orderly fashion. It stuck out in sharp spikes around her head so that she resembled a medieval mace. Her eyes were dreamy because under her French no -nonsense crispness beat the heart of a romantic. She had read the entire fantasy section of the library and also all the romance novels. She was always waiting for something wonderful to happen to her. Just like it did in books.

All around the children’s department the four women went, until Taisha gave a gasp.

“Have you spotted it?” asked Lucinda. She said “it” because they didn’t know yet if “it” was a boy or a girl.

“I see a baby,” said Taisha. “In a bassinet on a shelf.”

“That is probably the one,” said Jeanne-Marie.

“It is almost certainly the one,” said Doris.

“Of course it’s the one,” said Lucinda. “For God’s sake, pick it up.”

So Taisha did and the baby immediately stopped crying.

“Awwwwww,” said all the women at once.

“What’s going on in here?” asked a handsome, tall man in a suit standing in the doorway suddenly.

All four women’s heads, which had been craned in Taisha’s direction, turned immediately to spy Mr. Fellows. The head of the whole library.

“Nothing!” said Lucinda and Jeanne-Marie and Doris as they crowded around Taisha, blocking Mr. Fellows’ view of the baby and the bassinet.

Forever after, none of them could tell you why they had done this.

But that was the beginning.

WHAT TO DO?

When Mr. Fellows had gone, the four ladies retired to the inner back office. There were two offices the three children’s librarians shared. There was the outer office, where others might seek them, and then there was the inner office, which was inside the larger outer office, where they might not. It was this private office where they took the baby.

The four of them stood around the bassinet staring down and cooing at the baby as if she were some witches’ brew and they the witches, for which only Lucinda really looked the part.

“Well . . . ,” said Doris eventually. “We must give her back.” (It had been determined that “it” was a her.)

“Must we?” asked Taisha. “Someone was very careless about leaving her.”

“It isn’t a question of must we or must we not,” Lucinda reminded them. “After all, someone somehow clearly got into the library, deposited the baby for a

moment on an empty place on the bookshelf and is going to return for her.”

“Well, it was still careless. Careless people should not be allowed to keep their babies,” said Jeanne-Marie, who of the four of them was the one most recently to give up the dream of having a child of her own. She clearly hadn’t entirely given it up. She wanted this one.

“ Jeanne-Marie,” said Doris warningly.

“Yes, I know,” said Jeanne-Marie. “But we are all thinking the same thing, aren’t we? We are all thinking that we want to keep this baby.”

“We will keep this baby,” said Lucinda, which so surprised the other three that they stared at her open-mouthed for a moment. “We will keep her until her mother—”

“Or father,” interrupted Taisha.

“Or father,” amended Lucinda.

“Or very careless babysitter,” said Jeanne-Marie.

“Or whoever is in charge of her returns. Now, is there a bottle in this bassinet? Baby may well be hungry,” said Lucinda.

There was none, so Lucinda suggested that Doris go to the nearest drugstore and buy a bottle and some baby formula and diapers.

“And a rattle,” said Doris.

“Oh, I’ve so many things like that at home still,” said Taisha.

The others did too but no one was admitting to anyone else that they had sadly gathered all the paraphernalia for having a baby and then when the baby had not transpired, instead of giving the baby things away, had kept them carefully packed in pretty boxes under their beds. Or in the case of Lucinda, who had the largest apartment, in a closet especially chosen for this.

“Yes, but no sense dragging it out, Taisha,” said Lucinda, who just naturally fell into the take- charge role. “I’m sure the mother will be along any moment. We will give the baby a bottle. And perhaps change her diaper. And that will be quite enough to do for this baby. Don’t you, any of you, dare get attached.”

So they all tried to stare meanly at the baby for a moment or two to break their already-forming attachment. Doris ran out for some diapers and formula and a bottle. When Mr. Fellows caught her escaping out the front door, she told him she was double-parked.

All day the three children’s librarians took turns feeding the baby in the inner office, where except for the baby’s occasional cries no one would ever have guessed

they had a baby on board. Jeanne-Marie was put in charge of keeping an eye on the shelf where they’d found the baby in case her owner were to try to sneak in to take the baby back. But usually no one went anywhere near those shelves. They housed the old defunct children’s geography books that no one wanted to read and that they hadn’t enough of to fill up the whole shelf.

By the end of the day when the library closed and all chance of someone returning for the baby expired, the four librarians had a new problem. They convened once again in the inner office to discuss it.

“Well, we shall simply have to call the police,” said Lucinda. “There’s no other way.”

“There are other ways,” said Taisha. “One in particular appeals.”

“Oh dear,” said Doris. “I was thinking the same.”

“You mean keep her,” said Taisha, tilting her head so the baby could see her dangling earrings. She became a sort of mini baby mobile. The baby stretched her little arms up toward the earrings. “Oh, look at her, reaching for my earrings! Are you Mummy’s oozy doozy smartest little baby in the whole wide world? We must keep her.”

“Just for tonight,” said Lucinda. “I will allow it just for tonight. And you’re not her mummy.”

“Yet,” said Doris.

“If you are, we are all equally her mamans,” said Jeanne-Marie. “Or equally not her mamans, for that matter.”

“Yet,” said Doris.

“And we are not taking this baby out of the library,” Lucinda continued. “If we neglect to call the police to tell them about the baby and one of us takes her home, that will be kidnapping. If we simply care for her here, well, after all, that is just being a good Samaritan and it’s the owner at fault for leaving her here. We can only be accused of caring for what the owner left behind.”

“Who will stay with her?” asked Taisha.

“I will,” said Lucinda. “I shall sleep on the floor. I am quite used to it from all my camping trips. I shall be quite comfortable if someone will just go back to my apartment and bring me my sleeping bag, nightgown and toothbrush. And whatever baby things from the baby closet seem appropriate.”

“Bonne idée!” said Jeanne-Marie, and she left to fetch it all and then on return helped Lucinda and baby settle for the night. She wanted to stay too, but Lucinda pointed out that Jeanne-Marie didn’t have a sleeping bag and this was patently so, so she went home.

The next day they all came back to the library with

yet more baby things from their own supplies. After that they kept the inner office door closed.

The baby’s owner never returned.

This presented some problems but none of them insurmountable. The four librarians chipped in and bought a daybed for the inner office. That was for whoever was staying with the baby that night. They all took turns. Mr. Fellows seemed to poke his head into the children’s room a great deal more often than was usual, saying, “Everything all right, ladies?”

As if he could smell a stolen baby, as Jeanne-Marie put it.

“Do you think he knows?” hissed Doris once when he had left.

“No,” said Taisha. “If he knew he would do something about it.”

“Are you sure everything is all right?” asked Mr. Fellows, poking his head in once again.

“It’s just fine, Mr. Fellows. If you would please leave us alone to do our work,” said Lucinda. It amazed her that Mr. Fellows never bothered to wonder why his reference librarian was so often in the children’s department.

When two weeks had passed, despite their best intentions and theatrical mean looks, all four librarians were soundly in love with the baby.

“We must name her,” said Lucinda.

“And give her a saint’s name as well,” said JeanneMarie, because everyone in her family had one.

All four women’s minds went sadly for a moment to the names they had listed in their heads for their own future babies once upon a time, and all women knew they could not use those names.

“Never mind that,” said Lucinda, who, when everyone had teared up, seemed to understand what they’d all been thinking. “This is a child of the library. We must give her a literary name.”

That set all minds on different happier tracks.

“Louisa?” suggested Doris, who liked the work of Louisa May Alcott. “Just to kick things off. I don’t really like the name.”

“Well, we’re not calling this baby by any name that one of us doesn’t like,” said Lucinda.

“Jane?” said Taisha, who was a big fan of Jane Austen.

“Too plain,” said Jeanne-Marie. “What about Madeline, as in . . .”

And all four librarians recited the wonderful opening lines of Madeline.

“No, we could never call her by name without remembering those immortal lines. We would recite them to

her constantly. She would grow bored. Disaster. How about Maxine, like Max from Where the Wild Things Are but feminized?” asked Taisha.

“Heavens no,” said Lucinda.

“Too unrecognizable as a book name?” asked Taisha.

“No, I simply don’t like it,” said Lucinda. “It sounds like a gum- snapping gangster’s moll. We can do better than that for little Esmeralda.”

“Esmeralda?” said Doris.

“Oh!” said Lucinda, blushing in embarrassment. “That is simply what I’ve been calling her in my head all this time.”

“Esmeralda,” said Taisha slowly, as if trying it out on her tongue.

“Where is there an Esmeralda in literature?” asked Jeanne-Marie. “I can’t think of one.”

“There is probably one somewhere,” said Doris. “There are a lot of books in the world. There is sure to be an Esmeralda in one of them. You know—I like it.”

“We could call her Esmé for short. Like ‘For Esmé—with Love and Squalor’ by Salinger,” said Taisha.

“Or not,” said Lucinda.

“Or Essie,” said Doris. “I believe in The Hunchback of Notre Dame there is an Esmeralda. Not that it matters.”

“And Esmeralda is the saint of nuptials, I believe,” said Jeanne-Marie. “So two in one. Essie for short. But what will her last name be?”

“Well, she won’t need one for a while,” said Lucinda. “We are sure to be found out before long, and then we will probably all go to jail despite the fact that we never kidnapped her. And then the whole question of her name will be moot.”

“Yes, we will probably be found out and all go to jail, but it will be worth it,” said Doris, whose turn it was to hold and nuzzle Essie.

But the amazing thing was that not only did they not go to jail, but Essie continued to grow up at the library and nobody found out at all.

ESSIE’S BABYDOM DISAPPEARS AND HER CHILDHOOD BEGINS

Well, no one thought this little deception would go on as long as it did. At first, the inner office was used by both Essie and whichever librarian was sleeping over. The librarians put a small fridge in there, a microwave, and a dresser. No one was allowed in the inner office anymore. However, eventually when Essie got older, the women put a daybed for themselves in the outer office too so that Essie could have her own room and a little privacy. They bought toys for her and created a toy corner in the library, and even though all the children could play with these toys, Essie knew they were really her own.

There were some glitches on the way, of course. The bathroom was one. Lucinda bought a large tin washtub, which they moved from the inner office to the children’s

librarian’s bathroom right off their office after the library closed so that Essie could have sponge baths. It wasn’t a great solution, it was messy, but at least Essie didn’t have to be bathed in a public bathroom with all those shared germs, or “yuck,” as Taisha put it.

One day Mr. Fellows, who, the librarians said to each other, still oddly considered the library offices in the children’s section part of the library and not the women’s second home, crept into the outer office. The inner office door was open and he could see in quite clearly.

“OH!” he said. “You’ve put, um, a daybed in the, uh, outer office!”

The four librarians, who were sitting together drinking coffee and eating Lucinda’s homemade molasses cookies, looked at him inquiringly. They considered themselves more than a match for the shy but devastatingly handsome Mr. Fellows.

Essie was off in a corner of the library playing with her toys, thankfully.

Lucinda just nodded at him with dignity. Her nod said, Why wouldn’t we have a daybed in the outer office?

“Some people might find that unusual?” Mr. Fellows pressed. “What would you tell them you used it for?”

“Naps,” said Taisha. “It has been proven in studies

that productivity improves ninety- six percent when the worker has an afternoon nap.”

“Fine,” said Mr. Fellows. “But I also see one in the inner office?”

“Sometimes one likes to nap here, sometimes there,” said Lucinda. “What business is it of anyone’s, anyway?”

“Oh! A small refrigerator? Some might question that . . . ,” said Mr. Fellows as his eyes slowly swept the room.

“Why? Do you not like your drinks cold?” asked Taisha.

“But why a microwave? Do you really need hot snacks? Suppose someone were to complain about all the electricity being paid for by taxpayers to keep you in hot food and cold drinks?” asked Mr. Fellows.

“I would tell them to speak to our union,” said Jeanne-Marie. “Mon dieu, are we to live like barn animals?”

“I do not think a small microwave really uses that much electricity,” said Doris, “but if you insist we will pay for it ourselves.”

“Well,” said Mr. Fellows, blowing air out of his mouth in one big puff— something he did when totally lost for words—“we have no requisition forms for such a thing. If you need a kitchen, there is always the small one in the event room.”

“I thought librarians weren’t supposed to use that,” said Taisha. “That it is for event users only.”

“I will, ahem, approve of its use for just the four of you. If you keep it to yourselves. Because you, ahem, seem to have so many studies to support your, ahem, needs. And ahem, a scary union.”

“Yes, it is scary,” said Jeanne-Marie. “Beware, mon petit homme.”

“But what about the dresser?” asked Mr. Fellows, seizing upon something he was sure they would have no reasonable explanation for. But he was wrong.

“It has been proven that workers who have a change of socks available to them have eighty-two percent greater efficiency,” said Taisha.

“Where are you getting these studies?” asked Mr. Fellows.

The other three turned their heads to Lucinda. She was the reference librarian.

“Mr. Fellows,” she said importantly, “if you do not keep yourself up -to - date, do not expect us to do it for you. That is not our job.”

And she strode out and back to her reference desk. Mr. Fellows watched her go longingly. He knew by now that he was a little in love with her. He tried to squelch

this. He knew she was above his pay grade. She was so wonderful and he was so ordinary, although devastatingly handsome. You couldn’t declare yourself to someone you knew to be so superior to yourself. He didn’t know that thinking your beloved was so very much more wonderful than anyone on earth, including yourself, was the very definition of being in love. And that if no one declared themselves because they thought themselves inferior, the human race would die out by midnight. He thought the situation hopeless. And every year it grew a bit worse. “Nathan,” he said to himself after his encounters with Lucinda, when his hands shook and his hair stood on end for hours, “you must stop this and content yourself with TV dinners and many streaming channels.”

If the librarians had suspected that Mr. Fellows had these deep feelings for Lucinda, they might have tried to use it to their advantage. Their great fear was that Mr. Fellows would find out about Essie and call the police. So every time he made a foray into the children’s section they held their breath.

Of course, it wasn’t only Lucinda who had the odd man falling in love with her. As Essie got older, Jeanne-Marie found herself with a series of boyfriends. So did Doris. So did Taisha. But their secret baby posed

a definite impediment to romance, which tended to end about the time the boyfriend started asking why they were never available every fourth night and why they stayed overnight at the library.

“Overtime,” Jeanne-Marie said to her current beau. It did not go down well.

Still, despite everything, Essie’s true situation remained undetected, and by the time she was eleven, everyone had simply gotten used to her hanging out at the library. It was as accompli a fait as ever you could hope to see. Among the patrons she was commonly known as the library girl.

The librarians couldn’t send Essie to school. That would involve too many complications, as well as having to make up a last name for her. Something they had put off for so long it didn’t look as if it would ever get done. They asked her if she would like to choose one of their last names. They were Soprano (Lucinda), Roberts (Taisha), Hempleback (Doris), and Tremblay ( Jeanne-Marie). Essie was sorely tempted by Hempleback, although she didn’t tell them. You have to admit, Esmeralda Hempleback is a splendid name. But she loved them all equally so she just told them she couldn’t possibly choose.

Essie No Last Name was as happy as a child could be.

She was extravagantly loved by four mothers. She had miles of books to read and was read to at an early age. She had many books to explore daily, and she had four sensible mothers who didn’t ascribe to the nonsensical notion that there were any special books for any special people by race, creed, religion or age, but instead believed that anyone could and should read everything, that all stories were good stories so long as they were true to the teller. And that you should never try to pretend that the things that had happened in the past hadn’t, or that the way people believed or thought or felt hadn’t happened. Because what good was a story if it was censored and untrue? Stories were for sharing the infinite ways there were to be human. It wasn’t up to one group to decide how another should have felt or acted. It was important only to understand they did and try to understand that. And therefore enlarge your own scope of understanding. Only the storyteller can relate his or her own truth, and everyone else should keep their sticky little fingers off it. All four of Essie’s mothers were sensible enough to know that the only way books let you into the hearts of people is by letting you into their imperfect human hearts as they actually are, not as you, the reader, might wish them to be.

Because Essie had such wise mothers who understood

these very basic tenets, by the age of eleven she had had a splendid education. She loved reading because it let her explore freely and unfettered the whole universe. Or as much as had been put into print and was housed in the Huffington Public Library main branch. Her plan was to read every book there. Just for a start.

“And then what?” asked Lucinda when Essie had announced her reading intention.

“Find a new library,” said Essie. “With books I haven’t yet read.”

“I think you will find all libraries carry pretty much the same selection,” said Doris, who couldn’t stand the idea of Essie moving on to another library. Or anywhere at all.

“Oh yes, but some libraries are bigger. This isn’t a very big town. Huffington’s population is only fifty- seven thousand,” said Essie.

Fifty-seven thousand and one, thought Lucinda, because at least one baby had gone unrecorded.

“A big city probably has a really big library. Perhaps I will move to New York when I get older. I would like to see a really big city library.”

This brought up another painful subject.

Essie had been happy living at the library. It was the

only life she knew! The library was right downtown in Huffington. In the adult section with the floor-to-ceiling windows there were dozens of big comfy chairs. She could sit and watch all manner of people go by. She got to meet all manner of people in the library. But she spent very little time out of the library. Now that Essie was eleven, Taisha began to worry that Essie wasn’t seeing enough of the world.

“It’s such a small world she lives in,” said Taisha. “Is that what we want for her?”

“It isn’t small at all,” argued Jeanne-Marie. “The whole world is here in these books.”

“Yes, dear, but she needs some firsthand experience,” insisted Taisha.

“I don’t see why,” said Jeanne-Marie. “How much experience does any eleven-year-old have? I grew up in the woods of Orléans and only knew my family and a few owls.”

“I don’t want her to feel like a prisoner,” said Taisha. “We did not adopt her to keep her prisoner. Or as a pet,” she added after consideration.

“Taisha is right,” said Lucinda. “Other children her age get allowances and get to ride their bikes around the block, at least.”

“We should get her a bike,” said Taisha.

“Oh, I’d be worried about her riding a bike here. Right downtown,” said Doris. “All the traffic.”

“There’s the pedestrian mall just around the corner. Four blocks of shops on either side of the street, no traffic. And across from the library is the big park with many safe walkways. Both places excellent for bike riding,” said Lucinda.

“Oh dear,” said Doris. “I just don’t like it. Suppose she falls into a fountain and drowns?”

“Have a napoleon,” said Lucinda, who still brought them all baked goods but by now had graduated to French pastries. Even Jeanne-Marie, who didn’t like to think anyone but the French could make them, had to admit that Lucinda’s were pretty good.

Doris ate a napoleon, but it did little to allay her fears.

Still, Lucinda bought Essie a bicycle and the four of them took turns when the library was closed, teaching her to ride the bike in the big library foyer and around the adult stacks. When she’d gotten quite good at it, even scaring Doris with a few wheelies, they allowed her to take the bike out when she liked. It was kept chained and locked in the bike rack in the small library parking lot. Doris always stood at the window when Essie was in the park and watched her. Taisha and Jeanne-Marie were

both known to follow her stealthily, hiding in doorways when she rode to the mall.

Then one day they had to let Essie expand her world even further. This was because of Oscar Steinberg. He was one of Essie’s favorites. Essie knew all the regular library- goers at least by sight and she exchanged pleasantries with quite a few, but of all the regular patrons, Oscar was the only one who came every single day. He lived in the library almost as much as she did. He liked to sit in the chairs by the wall of windows on the side of the library that faced the busy downtown street. There, in a big soft comfy chair, protected from the elements, he could watch people go by on the sidewalk outside. He could watch the cars. He could see across the street to the mostly boring offices, but also to The Chocolate Shop with its soda fountain that had existed in that spot for a hundred years. There you could witness young men and women having first dates. Old people with all the time in the world savoring a new flavor of ice cream. Mothers looking harried with babies and children attached to them, taking time out for a rainbow sherbet cone.

In this area of comfy chairs and windows there were also lots of library- owned newspapers hung up on special rods. This was something that fascinated Essie,

the practice of hanging newspapers by their folds over rods as if they were drying laundry. Oscar would select one, usually the Huffington Gazette, take it to his favorite chair, settle himself and promptly fall asleep. One day he awoke to find Essie staring at him.

“Old-man-watching, are you?” he asked her.

“What?” she asked, startled, not catching his drift.

“You know, like bird-watching,” he said.

Essie thought this was very funny and sat down next to him. She was just at the part of her social education where Taisha was teaching her to make small talk pleasantly. She found this difficult sometimes, not knowing exactly what to say, but Taisha had explained to her that difficult or not, she must keep up her end of a conversation no matter what and at dinner parties she must always contribute her fair share. “If you’re sitting at table with eight people for two hours, you must contribute fifteen minutes of solid conversation,” Taisha had said.

“Two hours divided by eight equals eight fifteen-minute time slots. One of them is your responsibility.” This was math and social etiquette mixed together.

“Like what?” asked Essie. “What do I say?”

“Well, that is so often the problem. You have to gauge your audience. In some crowds entertaining

anecdotes will do. In others, you must comment knowledgeably on the news of the day. And with yet another group you might trade recipes. It’s never one size fits all. Test the waters.”

Essie was thinking of this as she stared at Oscar. She could detect nothing in particular in the waters she was testing that would help her start a conversation with him, so finally in defeat she said, “How do you do? I am Essie and I am sitting in a chair.” It was the only thing that came to her.

Oscar thought this as funny as she thought his old-man-watching comment. They cracked each other up. Immediately they knew they would be friends. She tried to visit him every day. It was her habit to wait until he’d been sleeping for an hour in his chair, then sit down next to him and stare at him until he woke up. He always said the same thing, “Old-man-watching, are you?” And she always replied, “No, I am Essie and I am sitting in a chair,” as if such code words began the meeting of the Oscar and Essie Society or The Oscar and Essie Comedy Hour, and the conversation moved on from there.

One of the things they liked to do was look out the window and comment about the people strolling past.

“My, my, aren’t we busy and important?” Oscar

would comment on some man in a trench coat and briefcase briskly racing off to his office.

“You hardly ever see feathers in hats anymore,” Essie would say as a woman strutted by in her Sunday best.

“You hardly ever see hats anymore,” said Oscar.

“Touché,” said Essie.

Oscar and Essie particularly liked to see what people bought at The Chocolate Shop. People came out carrying the most enticing-looking bundles with big pink-and-white-striped ribbons. Others came out carrying ice cream cones and malted milks to go. Or bags of candy.

Oscar and Essie always said the same thing when someone came out carrying a vanilla cone. “What a loser.”

When there weren’t too many people standing in front of The Chocolate Shop’s window, Essie and Oscar could spy on the people sitting on stools at its soda fountain. One day while they were watching this Essie said, “I wonder what they are drinking. Those tall red and green and yellow things with straws.”

“Boy, you have good eyes. Oy, would I kill for eyes like yours. They’re phosphates,” said Oscar. “Surely you have had one of their phosphates?”

Essie shook her head. “I don’t even know what that is. And I’ve never been to The Chocolate Shop.”

“They take some flavored syrup— cherry, lime or orange— and some seltzer water and spritz it in and you get a very bubbly, very gassy-making if you’re an old man like me, sweet drink. You should try one. Or an ice cream. The Chocolate Shop has forty flavors of ice cream. Forty! Some horrible.” Then Oscar reached into his pocket and got out five dollars. “Here, go ahead and skip over there and have something. I think I am going to take a nap.”

“I’m not supposed to take money from people,” said Essie.

“Not even from a friend?” said Oscar.

“Well,” said Essie, considering. “I know you’re a friend but my mothers don’t.”

“Your mothers? Plural?” said Oscar.

“I meant my mother,” said Essie. This was the first mistake of this sort she had made, and it made her blood run cold. She was never to speak of her situation. Not to anyone. For any reason.

“Oh well, suit yourself,” said Oscar, pocketing the dollars again. He wasn’t miffed. He had lived long enough to know that the world was full of all kinds of people and a lot of them were different from you and had different perspectives and rules and if you went around taking everything

personally you were going to live a life of misery. And he also knew that the world was not the innocent, carefree place he imagined it had been when he was young, when it was okay to take money from friends. The world had moved on from such gentle customs. Actually, the world had never been the innocent, carefree place he imagined it had, but if it gave him comfort to think it so, who was anyone to argue? Plus, he was really tired again. “I’m going back to sleep. When you get old, Essie, you find yourself slipping into sleep more and more, as if you’re practicing for death.” And within minutes he was snoring.

When Essie told her mothers about this, they had a meeting.

“That Oscar is right. She should be able to go across the street for a phosphate. And she shouldn’t have to rely on library patrons to pay for it. She shouldn’t have to stare at other children drinking phosphates. She should be able to get one herself,” said Taisha.

“Well, we can’t take her,” said Lucinda firmly. “If we take charge of her outside the library, we are crossing a line. We may not be kidnapping, but it may be seen that way by some officious person or officer of the law.”

“She’s only going across the street,” said Taisha. “One of us could stand at the window and watch her.”

“I wish Oscar wouldn’t say such morbid things to her,” said Doris. “Practicing for death indeed!”

“It’s perfectly fine,” said Jeanne-Marie. “The French, they look death in the eye and say, Straighten up! North Americans are far too afraid of death. You live until you die. Point final! It’s a fact.”

“It’s not a fact you want to dwell on at eleven years of age,” said Lucinda.

“Can we get back to the point?” said Taisha.

And so they settled on five dollars a week phosphate money.

“And speaking of giving her money, let us think down the line,” said Doris. “What are we going to do about her money situation? We can’t take her to open a savings account. She has no last name. We can’t put ourselves down as her guardians. I don’t like how this is all going. Maybe it is time to apply for legal guardianship.”

“How can we do that without explaining we have kept her prisoner in the library for the last eleven years? We will all go to jail,” said Taisha. “And as much as I don’t want to go to jail, I’m even more worried about what would happen to Essie if we did.”

So they told Essie that she would have to go to The Chocolate Shop alone but she could go. Taisha showed

her how to use money. Lucinda admonished her to always count her change. Doris told her one of them would keep an eye on her from the library window.

Essie was delighted. She took her five dollars and went over, climbed on a stool as she had seen so many do before her and had a cherry phosphate. She bought a two foot long licorice whip and brought it home to eat while reading The Witch Family. She decided this would be her Saturday-afternoon ritual from then on. She seldom varied it. Sometimes she had a caramel ice cream instead. But not often. When she told Oscar about all her Chocolate Shop treats, he said, “Bully for you. Look at this ad. They’re doing King Lear at the Huffington Theatre. That’ll be a gong show. Have you read any Shakespeare yet?”

“No,” said Essie, “but they have a kids’ version of the plays in the children’s library.”

“By kids’ version, what do they mean?” asked Oscar.

“Shorter, I think,” said Essie. “With pictures.”

“Dreck! Don’t bother,” said Oscar. “Hold out for the good stuff.”