de Halve Maen

Journal of The Holland Society of New York

Vol. 95, No. 3 2022

100 Years

Journal of The Holland Society of New York

Vol. 95, No. 3 2022

100 Years

Adopted in 1887 as our official badge and received for the first time by members as a souvenir at the Annual Dinner in 1907, this beggar’s badge is unique and has been worn proudly for formal events by our members since.

Gold-filled with an orange ribbon

Now available for $190 including shipping

To order a medal, please email us at info@hollandsociety.org

1345 SIXTH AVENUE, NEW YORK, NY 10105

President Col. Adrian T. Bogart III

Vice President Secretary

Richard E. van Deusen

Sally Quackenbush Mason Treasurer Domine

David Nostrand Rev. Paul D. Lent

Advisory Council of Past Presidents

Kenneth L. Demarest Jr.

Robert Schenck

Peter Van Dyke

W. Wells Van Pelt Jr.

Walton Van Winkle III

William Van Winkle

Magazine of the Dutch Colonial Period in America

VOL. XCV Fall 2022

42 Editor’s Corner

Thomas Bogart

D. David Conklin

Eric E. DeLamarter

Jonathan Doucette

Sarah Lefferts Fosdick

Andrew A. Hendricks

John O. Delamater

Robert Gardiner Goelet

David M. Riker

Charles Zabriskie Jr.

Trustees

Trustees Emeriti

Abbie McMillen

Joseph Roosa

Andrew Terhune

Ethan Van Ness

Lisa Bloodgood Weeden

Laurie Bogart Wiles

David William Voorhees

Ferdinand L. Wyckoff Jr.

Stephen S. Wyckoff

Kent L. Stratt Rev. Everett Zabriskie

Burgher Guard Captains

Sarah Lefferts Fosdick and Ethan Van Ness

Vice Presidents

Connecticut-Westchester R. Dean Vanderwarker III

Dutchess and Ulster County

Florida

NUMBER 3

43 A Century of de Halve Maen: Celebrating One Hundred Years by David William Voorhees

47 The Albany Convention

Part 2: Who’s in Charge?

by Rudy VanVeghtenD. David Conklin

James S. Lansing

International Lt. Col. Robert W. Banta Jr. (Ret)

Jersey Shore

Long Island

Mid-West

New Amsterdam

New England

Niagara

Old Bergen-Central New Jersey

Old South

Pacific Northwest

Pacific Southwest (North)

Pacific Southwest (South)

Patroons

Stuart W. Van Winkle

Eric E. DeLamarter

Eric E. DeLamarter

Thomas Bogart

David S. Quackenbush

Gregory M. Outwater

Edwin Outwater III

Paul H. Davis

Robert E. Van Vranken

Potomac Christopher M. Cortright

Rocky Mountain

South River

Adrian T. Bogart IV

Walton Van Winkle III

Texas James J. Middaugh

Virginia and the Carolinas James R. Van Blarcom

United States Air Force

United States Army Col. Adrian T. Bogart III

United States Coast Guard Capt. Louis K. Bragaw Jr. (Ret)

United States Marines Lt. Col. Robert W. Banta Jr., USMC (Ret)

United States Navy LCDR James N. Vandenberg, CEC, USN

Editor David William Voorhees

The Holland Society of New York was organized in 1885 to collect and preserve information respecting the history and settlement of New Netherland by the Dutch, to perpetuate the memory, foster and promote the principles and virtues of the Dutch ancestors of its members, to maintain a library relating to the Dutch in America, and to prepare papers, essays, books, etc., in regard to the history and genealogy of the Dutch in America. The Society is principally organized of descendants of the residents of the Dutch colonies in the present-day United States prior to or during the year 1675. Inquiries respecting the several criteria for membership are invited.

De Halve Maen (ISSN 0017-6834) is published quarterly by The Holland Society. Subscriptions are $28.50 per year; international, $35.00. Back issues are available at $7.50 plus postage/handling or through PayPaltm

POSTMASTER: send all address changes to The Holland Society of New York, 1345 Sixth Ave., 33rd Floor, New York, NY 10105. Telephone: (212) 758-1675. Fax: (212) 758-2232.

E-mail: info@hollandsociety.org Website: www.hollandsociety.org

Production Manager

Sarah Bogart Cooney

Christopher Cortright

John Lansing

Editorial Committee

Peter Van Dyke, Chair

Copy Editor

Rudy VanVeghten

David M. Riker

Laurie Bogart Wiles

Copyright © 2022 The Holland Society of New York. All rights reserved.

Cover: first page of the inaugural issue of The Holland Society of New York’s newsletter de Halve Maen, October 1922.

THIS ISSUE OF de Halve Maen is being produced on the one-hundredth anniversary of the publication of the magazine’s first issue. That inaugural October 1922 de Halve Maen was a four-page newsletter printed on dark orange paper. Over the succeeding century the newsletter underwent numerous changes to become the journal it is today. In 1990 the Rev. Howard Hageman passed the torch of de Halve Maen’s rich legacy on to me. It was and is a daunting responsibility, but under the generous guidance of de Halve Maen Editorial Committee Chairs James E. Quackenbush and Peter Van Dyke and copyeditor Rudy VanVeghten I continued to refine the magazine as a vehicle for disseminating the Dutch colonial period in America.

Throughout my years as editor, I have published several articles devoted to this magazine’s history, most notably with the Winter 2001 issue, and reprinted articles from previous issues. In the first article in this issue, I look at the year de Halve Maen was inaugurated and at the men who created it. In doing so, I found that the motivations for creating a Society journal in 1922 were not far different from the challenges that face the Society today. Cultural change and financial upheaval colored the Holland Society’s milieu. What particularly impresses me, though, is the vision and determination of those men who established this journal, Arthur Van Brunt, Tunis Bergen, and Frederic Keator. They saw the role of the Holland Society of New York as much more important than just another fixture on the Manhattan social scene.

In this current issue’s second article, Rudy VanVeghten explores the rapidly evolving events in Albany during the summer and fall of 1689 in the wake of England’s Glorious Revolution. This article is the second of a series that first appeared in the Summer 2021 de Halve Maen. In the first installment, VanVeghten presented the formation of the socalled Albany Convention as an outgrowth of that community’s concerns over attacks from French Canada and their Indian allies. This segment examines how the Convention now competed with New York City’s rebel government for control of the provincial New York frontier.

According to VanVeghten, currents of displeasure had long simmered along New York’s seventeenth-century northern frontier settlements in politics, religion, and the local trade-based economy. “More powerful than these smoldering grumbles,” he writes, “was the glue of mutual fear that Canadian French and Indians were plotting Albany’s destruction—a fear that bonded everyone together in a common cause until the summer of 1689.” Jacob Leisler’s takeover of the provincial government in New York City in June 1689 caused Albany “to divert precious physical and emotional resources away from the Canadian threat to focus more on the escalating rebellion down in New York.”

Leisler’s efforts to extend his authority outside of New York City into the other counties of the province created resistance from Albany leaders. Fresh reports of Indian attacks and attempts by Onnagongue [Kennebec] Indians to enlist Iroquois support in a general war against colonial rule in late July 1689 created “simultaneous concern over Indian threats and possible Catholic sympathizers in their midst.”

What makes VanVeghten’s essay interesting is that he brings Anglo-Indian political alignments to the forefront of his discussion. Iroquoian and Algonquian nations are presented as active actors in events. Iroquois support for ongoing colonial military measures against attacks by Canadian-backed Algonquian tribes in New England such as the Onnagongue caused New England to seek reinforcement of their alliance with the Iroquois at the September 1689 conference in Albany. Although Iroquois leaders openly declined to declare war on all Eastern Indians, they did generally promise to continue following the Covenant Chain treaty with the New England colonies. With French and Indian attacks increasing in New England, VanVeghten suggests that the Leisler administration thwarted Albanian and New England efforts at a unified policy with the Indian nations. When Leisler’s government sent a troop of militia to take over the Albany government, matters escalated close to armed conflict. In the end, VanVeghten shows us it was Mohawk Indians who defused the threatened hostilities between Albanians and New Yorkers.

VanVeghten reveals current cultural shifts in historical thinking that demand recognition of the neglected contribution of groups once marginalized by the standard Eurocentric narrative. Seventeenth-century struggles were not only over trade but over larger transitions that were taking place in New Netherland and colonial New York as numerous peoples and cultures collided. In 1922 and 2022, cultural shifts caused by technology and massive immigration were transforming the world of the Holland Society of New York.

The Dutch have an expression, De tijd vliegt snel, gebruik hem wel (Time flies quickly, use it wisely). In order to survive, the Holland Society has learned to successfully adapt and transform while holding true to its mission “To collect and preserve information respecting the early history and settlement of the City and State of New York by the Dutch, and to discover, collect and preserve all still existing documents, etc., relating to their genealogy and history.”

David William Voorhees EditorWITHIN THE IMPOSING

granite-faced Renaissance-style walls of the University Club, Manhattan’s premier Fifth Avenue social club, a novel idea was presented to the Holland Society board of trustees and vice-presidents on May 4, 1922. Holland Society President Arthur Van Brunt rose to address this second joint gathering of trustees and newly formed vice-presidents seated around the massive conference table. He spoke firmly, recommending our Society publish an “informal bulletin” to be sent to all of the Society’s members to “keep them informed of matters of interest” and Society activities. Six months later, in early November 1922, the Society’s all-male membership began receiving in their mailboxes the first issue of a dark-orange-colored four-page leaflet named de Halve Maen. Society Secretary Frederic R. Keator and Tunis G. Bergen were instrumental in putting together the issue. On the issue’s second page, the editors wrote:

As a result of a suggestion made at the last joint meeting of the Trustees and Vice-Presidents, the Trustees have decided that the Society shall publish four times a year an informal bulletin in the form of a leaflet, to be sent to all of the members of the Society, which leaflet will keep them informed of matters of interest occurring in the activities of the Society. Hence, this first issue of De Halve Maen, a name dear to every American of Dutch descent, for, although the immortal Hudson was an Englishman, the flag under which he sailed—the horizontal tricolor of orange, white and blue—the ship and its crew were Dutch and we, in putting out into the unchartered seas which lie before this frail leaflet, can sail under the light of no more favorable planet or constellation than the silver rays of The Half Moon which guided those brave

mariners upon their way and brought them safely, not “to their desired haven,” but to a better one. We, therefore, bespeak for this craft a sympathetic reception and ask the indulgence of those upon the shores to whom it comes.

Appropriately, the newsletter’s lead article dealt with the increasingly deteriorating condition of the replica ship Half Moon, presented by the Kingdom of the Netherlands to the United States for the 1909 Hudson-Fulton Celebration. The ship was then moored at the mouth of Popolopen Creek on the west shore of the Hudson River just north of Bear Mountain in Orange County and had been shut off from access to the river by a railroad trestle. The editors called for this “valuable gift of the Government of the Netherlands [to] be placed where it can be seen by the largest number of people, either at a favorable spot along the New York City shore, or at Albany.”

The dismal condition of the replica ship Half Moon and the creation of a leaflet of the same name in 1922 were symptoms of broader transformations. Mass production of late nineteenth-century technological innovations was rapidly transforming middle-

and upper-class lifestyles following World War I. Automobiles and motion pictures had dramatically altered leisure habits by the dawn of the 1920s.

Record players and radios were now transforming home entertainment. Radio broadcasting in the New York metropolitan area began on September 30, 1921, when Westinghouse received authorization for WJZ, located in Newark, New Jersey. WOR began broadcasting from Manhattan on February 22, 1922. The rapid growth of radio listening is illustrated by United States President Warren G. Harding, who introduced the radio in the White House that February and made the first presidential radio address the following June.

Interest in sports also exploded, with baseball a universal national obsession. In May 1922 construction began on Yankee Stadium in the Bronx, with its first game played between the Boston Red Sox and the New York Yankees on April 18, 1923. Mass-media circulation in 1922, driven by advertising revenues, doubled that of twenty years earlier and was rapidly exploding with the introduction of such new periodicals as Reader’s Digest in 1922 and Time magazine the following year.

The Holland Society of New York’s social events seemed dated at the dawn of the Jazz Age. (The Society’s first newsletter reminded readers on page 2, “Its correct corporate name is: The Holland Society of New York .”) Moreover, the Society entered the 1920s in financial crisis due to bad investments a decade earlier. The situation worsened in 1920, when a sharp deflationary recession seriously hurt income. The treasurer reported at the 1920 Annual Meeting that the principal of the Society’s investments had a value of $10,450, with an annual income of $447.50; these numbers fell the following year to $8,987.45 investments with an income of $385.00. In 1920 it was predicted that the Society would soon be running an annual deficit of $2,500. Moreover, the membership was undergoing a small but steady decline.

The last thing the Society needed was a declining membership at this time. The subsequent dispute over how to reverse the trend brought to the fore the long-simmering feud between those who saw the Society as a social club and those who viewed its mission as a scholarly organization.

Prohibition in January 1920 ended the Society’s Annual Smoker, the reputtion of which had fallen so low that one member recalled it as having a “downgraded beer hall atmosphere.” In 1920 Arthur Van Brunt felt it was a needless expense.

Other members felt that money was being wasted on the Year Books and the Society’s scholarly publications and translations. An innovation occurred in 1920 when the trustees created the post of Domine (Society chaplain). At the April 6, 1920, Annual Meeting, Dr. Henry Van Dyke was elected to serve as the Society’s first Domine. But it was felt more was needed to be done to maintain a broader membership.

Meanwhile, other heritage organizations similar to the Holland Society had also appeared throughout the former New Netherland territory; organizations which some confused with Holland Society branches. For example, at the time of the planning for the 1924 Albany Tercentenary Celebration, several descendants of that city’s early settlers formed the hastily organized “Descendants of Early Dutch Settlers of Albany” to take part in those ceremonies. The organization reformed in 1924 as the “Dutch Settlers Society of Albany.”

The Holland Society of New York maintained cordial but firm relations with these organizations. When in 1923 the National Huguenot-Walloon Tercentenary Commission asked the Society trustees to participate in the celebration of the three-hundredth anniversary of the Walloons settling of New Netherland, the trustees accepted with the reservation that “this Society was not prepared to admit the contentions of the Commission as to the settlement of 1624 being the first permanent settlement, and reserved the right to state and urge its views that the Dutch had made permanent settlements on Manhattan before that date; that we, of course, know of the settlement of 1624 and would gladly cooperate in celebrating its important tercentenary with that reservation.”

Although Holland Society members residing outside of New York City had long organized informal local groups, it was not until 1921, during Arthur Van Brunt’s presidency, that formal steps to promote local Society chapters occurred. Van Brunt saw the promotion of these organizations as a way to help members far from Manhattan to maintain a sense of participation in the Society. To keep the newly formed branches informed of Holland Society events, Van Brunt proposed the members’ newsletter in May 1922.

The initial issues of de Halve Maen were small six-by-nine-inch, four-page orange leaflets prepared by Society Secretary Frederic Keator and History and Traditions Commitee chair Tunis Bergen. The

issue contained items on new members, a necrology, and Society events. While the state of the replica ship Half Moon was the lead article, the first issue’s main article began on page 3. This piece was a reprint of an article, “When the Seagull Came,” that appeared in the Sunday News of October 15, 1922. The Sunday News article declared that the three-hundredth anniversary of the settlement of Manhattan Island would occur on May 4, 1926, to honor when the ship Zeemieuw (Sea Gull), skippered by Adraen Joris, brought Pieter Minuit as “governor.”

Tunis Bergen took exception to the 1626 date and followed with a lengthy response. “Whether a date earlier than 1926 should not be selected as the proper date for such a celebration of the 300th Anniversary of the Settlement of Manhattan Island is a question on which there is some difference of opinion,” he wrote. Bergen argued that individual settlers had arrived since 1613 and they “were real settlers and men of enterprise and daring inspired by the appeals of Willem Usselinx in the Netherlands for a score of years or more to the people of Holland to go to America, not only for commerce and enterprise, but ‘to establish new Republics there,’ gain a ‘vantage ground against their enemies, the Spaniards, and civilize the natives.’ ” The January 1923

Chair of the Holland Society’s History and Traditions Committee, former Society President Tunis G. Bergen was instrumental in the early production of de Halve Maen.

issue of de Halve Maen then introduced a series of brief sketches on the leading personalities of New Netherland, “whose lives most of us know little and of whom, in any event, we need to be reminded.”

To elevate the tone of the Society’s dinners, Trustee Dr. Fenton Turck had originated the idea of presenting a medal to a distinguished person who would speak that evening on a cultural subject. At the Society Meeting on December 4, 1922, Augustus Thomas, executive chairman of the Producing Managers’ Association, spoke about the stage, and Carl E. Akerley, of the American Museum of Natural History, spoke of his experiences hunting gorillas in Africa. At the conclusion of the speeches, Dr. Turck presented to Thomas a gold medal for his contribution to American drama and to Akeley a medal for his contribution to science, exploration, and literature. These are the first gold medals presented to non-members of the Society.

During the Holland Society’s first half century the date of the annual banquet occurred in January. On January 18, 1923, the Society’s thirty-eighth banquet was held at the Hotel Astor on Broadway and 44th Street in Manhattan. About 237 members and guests, including representatives of other societies, attended. President Edward De Witt presided as toastmaster. While the new minister from the Netherlands, Jonkheer Dr. A.C.D. de Graeff, was not able to be present, Consul-General for the Netherlands Dr. D. H. Andreae was present and spoke. The other speakers were: William Elliot Griffis, author and lecturer, who spoke on “Holland”; Dixon Ryan Fox, professor of history at Columbia University, who spoke on “Old New York”; and Robert E. Dowling, life member of the New-York Historical Society and an authority on New York conditions, who spoke on “New York of Today.” Knight MacGregor, who performed at the December 4 meeting again sang accompanied by Miss Wallace.

The third issue of de Halve Maen appeared in April 1923. Its lead article was devoted to the Annual Meeting held on April 6, 1923, at which De Witt Van Buskirk was elected Society president. But three items in that issue are particularly noteworthy.

The first item was that at the conclusion of the business meeting Dr. Turck introduced Daniel Chester French, the distinguished American sculptor and, “after giving a brief narrative of the principal facts in his life, eulogized his work and achievements,” President Van Buskirk presented

to French the gold medal of the Society. A similar medal was also presented to Dr. William A. Murrill, curator of the New York Botanical Garden, a leading authority in the science of mycology. Murrill then addressed the gathering on the subject of “Fungi and Their Relation to Forestry in America,” illustrated by stereopticon pictures. Canadian-born Henri Pontbriand, one of the great tenors of the day, sang several solos to piano accompaniment.

The next item of interest was a statue of William the Silent that had been planned at the formation of the Holland Society in 1885 but had never been executed. In 1912 Tunis Bergen had gone to the Netherlands to procure a replica of the equestrian statue of William the Silent at the palace in The Hague or the civilian statue in the Plein at The Hague. The Royal family refused permission for a reproduction of their statue, and the decision was made to have the statue in the Plein reproduced. The cast was, however, lost during World War I. The newsletter announced that in January a power of attorney had been granted to Dr. W. Martin, professor of art at the University of Leiden and director of the Royal Art Galleries at The Hague, to contract with the Fonderie Nationale des Bronces in Brussels

for the “execution of the statue, according to terms substantially agreed upon.” It was anticipated that the statue would be completed shortly and thus a site for its placement commenced. The statue would find its home at Queens Campus of Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey, in 1928.

Of particular note in the April 1923 issue is Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s appeal to the Society members to “preserve the picture of old landmarks. Roosevelt, a newly installed Trustee in 1923, would continue as such until 1938, although he became governor of New York in 1929 and President of the United States in 1932. “The Holland Society has, in its long series of Year Books,” he wrote, “preserved for all time a chain of unique records, mostly those of churches, and relating to the early Dutch settlers in New York and New Jersey. Most of the old records have now been published either by this Society or by other agencies, such as the office of the State Historian and local historical societies.” Roosevelt continued:

There remains a work which I should personally be delighted to have The Holland Society undertake. Excellent monographs have been published on the old colonial homes in Massachusetts, Virginia, and other localities. No careful attempt has been made to preserve the likenesses of the many houses and other buildings of Dutch origin which still exist, especially in New York and New Jersey. I would, therefore, suggest that time is ripe for a collection of views of these Dutch buildings. By Dutch, I do not mean necessarily those buildings which were first erected while this was still a Dutch Colony—such a field would be altogether too limited. I mean, in addition, those buildings which were erected by the earlier Dutch settlers and under influences which were predominantly Dutch.

Roosevelt’s appeal met with success and his vision would be published in two volumes: Helen Wilkinson Reynolds, Dutch Houses in the Hudson Valley Before 1776 (1929), and Rosalie Fellows Bailey, Pre-Revolutionary Dutch Houses and Families in Northern New Jersey and Southern New York (1936). Roosevelt’s notes and edited manuscripts remained in the Holland Society archives.

The final issue of de Halve Maen’s first volume appeared in July 1923. The issue

concentrated on the vice-presidents and branches, and followed up on appeals to record New Netherland’s homes and graveyeards. Kiliaen Van Rensselaer was the leading New Netherland figure featured in that issue.

Thereafter, the newsletter continued to develop. The April 1924 issue carried an unusual and humorous warning for members to lookout for an old man,

who has personally visited several members and obtained money from them on the recital of his story that he is a native Hollander (which he probably is, because he has the appearance and accent of one) without money or work and in need of money to get to a distant city where he has friends. He usually says that his surname is the same as that of the person to whom he appeals, except that his own is the original Dutch spelling. He is tall, thick set, ruddy complexion, smooth shaven, white hair. He has lately been operating in New Jersey after duping New York members.

In 1928 the newsletter was expanded to an eight and a half-by-eleven-inch page format. During the next few years, the issues appeared sporadically, with no issues published in 1930 and 1931. In 1932 Wilfred Talman assumed de Halve Maen editorship and began the transformation of the newsletter into today’s journal. Talman gave a breezy tone to the description of Society events, injected historical fillers, and added woodcuts. When in July 1943 Walter Van Hoesen assumed editorship, de Halve Maen was totally revamped in a glossy format. It was not until 1956, however, when a resolution “designed to improve and expand de Halve Maen and other publications of the Society” was adopted, that historical articles by Society members began to appear with some regularity.

Richard Amerman’s assumption of the editorial helm in July 1958 began another transformation for de Halve Maen . “In this effort,” he wrote, “we cordially invite members everywhere to act as reporters and photographers.” The Society’s membership did not fill Amerman’s call for participation, and soon non-Society “guest writers” began to appear. One of the first was Arthur Peabody, a seventh-grade student at Albany Academy, whose award-winning essay on Domine Johannes Megapolensis was published in the July 1959 issue. By the 1960s essays by such scholars as Kenneth Scott,

When in July 1976 the Rev. Howard Hageman assumed de Halve Maen editorship, the journal truly acquired a scholarly cast. In January 1977 Hageman wrote: “The Editor’s drawer is so full of excellent material for future issues that he is embarrassed to predict just what will be appearing in the next issue.” The journal began to attract the attention of the leading scholars of New Netherland history. In the 1980s, the New Netherland Institute in Albany supplied de Halve Maen with many excellent articles from papers of the latest research presented at its Rensselaerswijck conferences.

In 2022, a century later, many of the challenges that faced the Holland Society of New York in 1922 remain. Discussions over whether the Society is meant to be a social club, a genealogical society, or a promoter of scholarly endeavors; what kind of membership should the Society consist of; and currently, what anniversary date (1623, 1624, 1626) will the Society use to celebrate New Amsterdam’s quatercentenary. During the past century, de Halve Maen has recorded for the public how the Holland Society of New York has successfully navigated these challenges and presented an ever-changing understanding of New Netherland and its contribution to modern America. The plan is for de Halve Maen to continue navigating these waters in the century to come.

York evolved rapidly during the early summer of 1689. Part 1 of this series (de Halve Maen 94:2 summer 2021) explored how the Albany Convention was formed as an outgrowth of the community’s long-standing concerns over attacks from French Canada and the Indian tribes with whom they allied. This segment will study how the Convention competed with the insurgent Jacob Leisler administration for control of New York’s provincial frontier and Albany’s key position as negotiators with their friendly trading partners—the Five Nations of the Iroquois.

New York Refugee. Not long after the Albany leaders’ first meeting of what became known as the Albany Convention in June 1689, a refugee fleeing from the escalating New York City rebellion arrived in Albany. Nicholas Bayard, Dominion councilor and militia officer, retreated up the Hudson on June 28 after he was charged with papism and treason by the rebels. Recalling the situation, Mayor Stephanus van Cortland later wrote about “Coll: Bayard narrowly escaping having two cutts in his hatt soe that he was forced to fly for Albany.”1 Bayard observed that unlike New York, Albany seemed “inclined to peace and quietnes.”2 His presence there, however, insured that tranquility would not last long. Albany would now have to divert precious physical and emotional resources away from the Canadian threat to focus more on the escalating rebellion down in New York.

Although more subtle in Albany than in New York City, there were currents of displeasure simmering under the surface

Rudy VanVeghten, copy editor of de Halve Maen, continues his series on the relationships between colonial Albany and Native Americans. This installment examines how these relationships spurred the formation of the so-called Albany Convention at the outbreak of Leisler’s Rebellion.

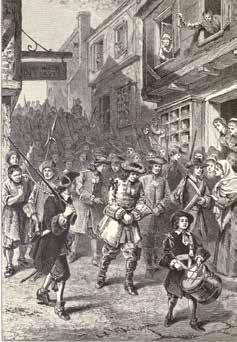

Pleading Their Case: Alfred Frederickse’s nineteenth-century etching depicts Dominion of New England Councilors Stephanus van Cortlandt, Nicholas Bayard, and Frederick Phillipse addressing New Yorkers during the days preceding Leisler’s Rebellion. Unable to convince the crowds of their authority, Bayard and Van Cortlandt eventually fled to Albany.

among a portion of the province’s frontier northern settlements that are evident in three key areas: politics, religion, and the local trade-based economy. Politically, the Dutch majority continued to hope for a return to the days before the English takeover of 1664, similar to the brief period of 1673–1674.3 In religion, there were disagreements between conservative Dutch Reformed Church adherents and those professing a more liberal version of Calvinism preached by Leiden-educated ministers like current Domine Godfrey Delius, as well as distrust of Lutherans, Anglicans, Anabaptists, and especially Quakers.4 Economically, there had been decades-old complaints by lower-level fur traders against the dominance of wealthier, more powerful figures such as the Schuylers, the Van Rensselaers, and Dirck Wessels ten Broeck.5

More powerful than these smoldering grumbles, however, was the glue of mutual fear that Canadian French and Indians were plotting Albany’s destruction—a fear that bonded everyone together in a common cause, at least up until Nicholas Bayard’s

arrival in the summer of 1689.

Sometime in mid-July 1689, Leisler began efforts to extend his authority outside of New York City into the other counties of the province, including Albany. From Bayard’s perspective, he did this “by sending messengers and letters to some of the military Officers and factious men, inducing them to follow their steps.”6 Albany’s civil and military officials found it

1 E.B. O’Callaghan and Berthold Fernow, trans. and eds., Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York, 15 vols. (Albany, 1856–1887), 3:608–609. [hereafter DRCHNY]. As with other communications from both pro- and anti-Leislerians, it is hard to separate fact from hyperbole and/or fiction.

2 Ibid., 604, 642.

3 A.J.F. Van Laer, Correspondence of Jeremias van Rensselaer (Albany, 1933), 460–61, 470.

4 The most notable instance of this was a 1676 dispute between Albany minister Nicholas van Rensselaer and visiting New York merchants Jacob Leisler and Jacob Milborne. E.T. Corwin, ed., Ecclesiastical Records of the State of New York, 7 vols. (Albany, 1901–1916), 1:689–92; E.B. O’Callaghan, The Documentary History of the State of New-York, 4 volumes (Albany, 1849), 3:895–97 [hereafter DHNY].

5 Charles T. Gehring, trans. and ed., Fort Orange Court Minutes 1652–1660 (Syracuse, 1990), 491, 501–502. 6 DRCHNY 3:598.

concerning that Leisler was a novice in the delicate art of negotiation with the Indians, and it was important that they—the Albany leaders whom the Indians trusted such as Pieter Schuyler, Dirck Wessels, Robert Livingston, etc.—maintain control until a legitimate new governor arrived in the province.7

Of particular concern to the Albany leaders were fresh reports of Indian attacks. A quartet of Onnagongue [Kennebec] Indians attempted in late July to enlist Iroquois support in a general war against colonial rule. “They understood the Christians intended to exterminate all the Indians,” the Onnagongues told the Iroquois, “and that it became therefore necessary for all Indians to unite against the Christians.” In reporting these proposals to their Albany trading partners, a delegation of Iroquois Mohawks added, “The Governor of Canada encourages them [the New England tribes] to wage war against the English and provided them with ammunition.”8

It was a combination of these worries, likely added to Bayard’s reports, that precipitated the Albany County leaders’ decision to reconvene on August 1, 1689. Following the trend of their first meeting a month earlier, the list of attendees demonstrates a broad range of inclusivity. Members included not only Mayor Peter Schuyler, Recorder Dirck Wessels, and four elected city aldermen, but also several who later aligned themselves with the Leisler faction, including Lieut. Jochim Staats, Sheriff Richard Pretty, and Gabriel Thomasse Stridles. There were over a dozen militia officers represented, including Capt. Marten Gerritsen van Bergen, Capt. Jan Bleeker, and Kiliaen van Rensselaer, captain of a horse company. Representatives traveled to the Convention meetings from Schenectady to the west and from Catskill to the south. In addition to seasoned politicians like cousins Peter and David Schuyler, there were political newcomers like twenty-two-year-old Jan Abeel, elected the previous year as an assistant alderman.

Led by Mayor Peter Schuyler, the Convention opened its August 1, 1689, meeting with a pledge “that all public affairs for the Preservation of there Majts Intrest in this Citty be managed by ye Mayr aldermen Justices of ye Peace Commission officers and assistants of this Citty and County, untill such time as orders shall come from there most Sacred Majts William & Mary.”9

One of the Convention’s first orders of business at this meeting, as with its previ-

First Cousins: French King Louis XIV’s father and English King James II’s mother were siblings, so when James was overthrown by his daughter Mary and son-in-law William, he sought refuge at his cousin’s court in France. Already concerned over a potential attack from French Canada, Albany residents only grew more fearful as word of William’s “Glorious Revolution” reached the American colonies. (Engraving by Nicolas Langlois, 1690).

ous meeting in June, involved the northern border. Scraps of information had filtered in from William’s escalating war against Louis XIV and the deposed James II’s Jacobite faction, augmented by rumors of Canadian probes into Lake Champlain. A quartet of traders in the Saratoga/Stillwater area aroused suspicions due to their French backgrounds. “It is therefore thought fit by ye magistrates of ye Citty of Albany Justices of ye Peace & militia officers of ye sd County who considering how dangerous such suspected p’sones are in this juncture of time yt ye sd antho Lespinard[,] John Van Loon[,] Renne Poupard [alias Lafleur,] and Villeroy be secured in his Majts fort at Albany till further order and till such time The Bussinesse can be further Inspected and Examined,” ordered the Albany Convention on August 5, 1689.10 Although these four fur traders were later found guiltless of conspiring with French invaders, the incident demonstrates the Albany citizenry’s simultaneous concern over Indian threats and possible Catholic sympathizers in their midst.

Leisler soon received word about the Saratoga traders as he continued to concentrate on fortifying the fort at Manhattan. Rather than seeing the situation in terms of a threat by Canadian French and Indians against Albany, he suspected a Jacobite plot in which these Frenchmen were conspiring with Albany’s leaders to defend their former allegiance to James II. “The place called Schorachtoge [Saratoga] belongs to the Magistrates there, who doe still Justice for their Maties King William & Queen Mary by the oath they have suorne to the late King James,” Leisler wrote to the governor

of Massachusetts on August 13. “It is the uttermost frontiers & there are six or seven families all or most rank french papists that have their relations at Canada & I suppose settled there for some bad designe & are lesser to be trusted there in this conjuncture of tyme than ever before.”11

Of more pressing concern than these traders to the Albany gathering were the intentions of the French Canadians and their allied Indian warriors. On August 5, four Natives from the Indian refugee village at Schaghticoke reported that “an army of French & Indians were Seen on ye Lake.” Albany dispatched Lieut. Robert Sanders with a militia contingent to “make Discovery,” but found nothing suspicious. Two days later, additional rumors heightened concerns, causing some residents to consider abandoning Albany, “by which means and bad Example of such Timorous and Cowardly People others will be Discouraged to stay and Defend there Majts Interest in this Frontier part of ye Province.” To stem this exodus, the Convention banned able-bodied residents from leaving.12

7 This view is expressed in a communication to Alderman Livinius van Schaik and Lt. Jochim Staats: “consider what a Conditio we would be with ye Indians if a Change of Magistrates and a Subversion of ye govnerment shhold at p’sent be made.” DHNY 2: 104.

8 DHNY 2:18–20. O’Callaghan equates the Onnagongues with the Eastern Abenaki tribe of Penobscots from present-day Maine. News of Indian attacks in Maine didn’t come until several weeks later.

9 DHNY 2:80.

10 Ibid., 82. Jan Van Loon was later involved in the Lutheran Church south of Albany and in the settling of the town of Loonenburg (present-day Athens) named for him. Villeroy was the nickname of trader Pierre de Garmeaux.

11 Ibid., 22–23.

12 Ibid., 84.

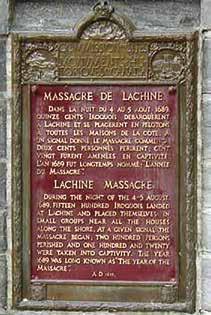

Within the next couple of weeks, residents were able to relax somewhat as word arrived of a major attack by the Iroquois on the Canadian village of Lachine on Mont Royal Island. “I have received news from Albany,” Jacob Leisler informed the Massachusetts Bay governor “that there is killed & taken by our Indianes of the french above 500.”13

Matters took on a more regional flavor in late August when a delegation from Massachusetts, Plymouth, and Connecticut colonies arrived in Albany in hopes of enlisting Iroquois support for ongoing military measures against Canadian-backed Algonquian tribes in New England, such as the Onnagongues. Desiring a formal conference, John Pynchon of Springfield, Mass., Jonathan Bull of Hartford, Conn., and the other delegates penned a dispatch to Arnout Cornelisse Viele, Albany’s envoy and interpreter among the Iroquois at Onondaga, to request the Five Nations each send representatives to Albany.14

Fears of Canadian aggression were again on the upswing in Albany following reports by Pynchon that a Canadian counterattack in present-day Maine had reversed the gains of the Iroquois’ sack of Lachine. Pynchon had been one of Gov. Edmund Andros’ councilors in the Dominion of New England. During the previous winter, Andros had pushed back French-supported aggression by Abenaki Indians in Maine, but Pynchon reported “That Pemmaquid was taken by ye Indians and french 45 people kild & Taken—also that there should be a ship be come to Quebek of ye french with news of wars Between Engld & France &

When residents of Albany and Schenectady heard about an Iroquois attack on the village of Lachine, near Montreal, they were reassured that their Native trading partners were still allies against a common French-Canadian enemy. Down in New York City, Jacob Leisler inflated the number of French casualties from that attack. Instead of 500 killed as he claimed, the number was closer to 200. (Image from Government of Canada “Parks Canada” website.)

therefore nothing can be Expected but yt ye french will doe all ye mischieffe they can to this governmt.”15

Apprehension grew further on September 1 when Harmen Jansen van Bommel reported the capture of a handful of French Indians on Lake Champlain “who were bound hither to doe mischieffe, and yt severall french were seen upon ye Lake.”16

Reinforcement Request. In times before William and Mary’s Glorious Revolution, Albany would receive assistance from the provincial New York governors to help defend against attacks from Canada. Now, the Albany Convention hoped for assistance from Leisler.

“Resolved Since there is such Eminent Danger Threatened by ye French of Canida and there Praying Indians to come into this

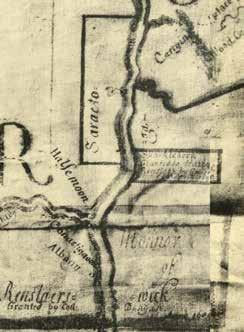

French Connection: Although this map indicates the old Saratoga patent was on the west side of the Hudson River, the actual patent included land on both sides. It was originally granted by New York governor Thomas Dongan, a Roman Catholic, in 1684 to Albany men including Peter Schuyler, Robert Livingston, Dirck Wessels ten Broeck, and others. (Map courtesy of the State Library of New York)

Subjects that there be Immediately An Express sent doune to Capt Leysler and ye Rest of ye Militia officers of ye City and County of New Yorke for assistance of one hundred men” along with gunpowder, ammunition, and financial support.17

This decision by the Convention demonstrates the diversity among its members. Colonel Bayard had fled Leisler’s regime back in the early summer, and his fellow former Dominion Councilman Stephanus van Cortland followed in mid-August.18 Their anti-Leislerian leanings were outweighed by the desperate need for support against Canadian aggression from any quarter possible. Any perceived threat from Jacob Leisler did not compare with the very real threat of attack from Louis XIV’s forces from Canada.

By September 12, Iroquois sachems summoned by the New Englanders had

13 DHNY 2:22; Allen W. Trelease, Indian Affairs in Colonial New York (Lincoln, Neb., 1997, reprint of 1960 Cornell University edition), 252. The Lachine massacre was in revenge of the 1687 French and Indian attack on Seneca territory by Governor Denonville.

14 Lawrence H. Leder, ed., The Livingston Indian Records 1666–1723 (Gettysburg, Pa., 1956), 147–48. Onondaga was the central tribe of the Iroquois confederacy where the Five Nations traditionally held their council fire.

15 DHNY 2:85. Pemaquid was an English outpost located near present-day Bristol, Maine.

16 Ibid., 87

17 Ibid., 88. Among the “Praying Indians” were some who had originated from the Mohawk castle at Caughnawaga, near present-day Fonda, NewYork. Converted to Catholicism by French Jesuit priests in the mid-1600s, they relocated in the 1670s to a new village south of Montreal, Canada.

18 DRCHNY 3:612. At some point, Van Cortlandt returned to New York City, where he was present at the Common Council meetings in October, shortly after which he again retreated up river to Albany. (Minutes of Common Council of the City of New York 1675–1776, 8 vols., 1:210.)

arrived for a conference at the Albany City Hall. Noting the general war between England and France on the European stage and between Canada and the English colonies in North America, the delegates reported that “the Easterne Indians being Instigated and Incoradged by the ffrench at Cannida who are yors and our mortall Enemies; have made Incurssion upon the Out borders of our grat Kings Goverment to the Eastward of Merimeck river & the places there adjasent.”19

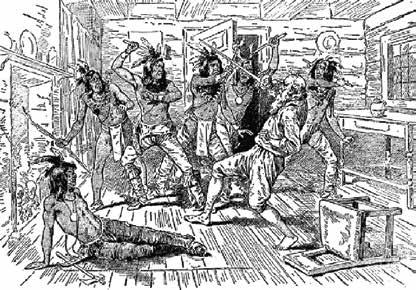

These attacks in present-day New Hampshire were in retaliation for underhanded actions by Major Richard Waldron of Cocheco (present-day Dover, New Hampshire) during King Philip’s War in 1676. Waldron had offered sanctuary to the neutral Penacook Indians as well as their guests from the Nashaway, Nipmuk, and other warring tribes. Once inside the village, the colonists broke Waldron’s promise by arresting any Natives who had fought against the English and either executed them or sold them into slavery.

This action had resulted in a split among the Penacook sachems, with the Christianized pacifist chief Wonalancet retreating with his followers to the north and west, and Wonalancet’s nephew Kancamagus leading revenge-minded warriors to align with Eastern Abenaki villages along the rivers of Maine. “Kancamagus and his Penacooks had come into league with the Ossipees, Pequawkets, Sacos, Androscoggins, and other eastern tribes,” explains

Concord, New Hampshire, historian James Otis Lyford. “The Penacook sachem was a leading spirit in this savage conglomeration.” After gathering at the old Penacook fort on the Merrimack River, they “made ready to wreak on Major Waldron, for alleged violation of faith and hospitality, the vengeance delayed for thirteen years, but not forgotten.” Waldron was killed in the June 28, 1689, attack on Cocheco, and Kancamagus fled into either Canada or Maine after the Massachusetts General Court declared him an outlaw.20

It was this and similar revenge attacks that led John Pynchon and the other New England delegates to seek reinforcement of the English alliance with the Iroquois at the September 1689 conference in Albany. “So long as ye French king and ye Jesuits have ye Command at Canida,” they advised the Iroquois, “You can never Expect to live in Peace it being there only Studdy nott only to Dukkoy and Treacherously murther your People butt to Send evill Emissaries amongst you as they did Lately from ye Eastward.”21

In a second session with the sachems on September 23, the New England delegation reminded the Iroquois that it had been King James, “being a Papist and a great Frinde of ye French,” who had blocked their efforts two years earlier to attack Canada in retaliation for Denonville’s 1687 attack on the Seneca nation.22

Although the Iroquois leaders openly

declined to declare war on all Eastern Indians, “they haveing Committed no acts of hostility upon them,” they did generally promise to continue following the Covenant Chain treaty with the New England colonies. In a separate private session, the sachems assured the colonists, “wee Esteem your Enemies ours, & we are DeSignd and Resolved to fall first on the Aurages or Penekook Indians, and then to fall on ye onnagongues & so our Enemies ye french.”23

Leder explains, “A war was then underway between New Englanders and the Eastern Indians. The latter, however, maintained friendly relations with the Skachkook Indians in New York and, it was suspected, with the Mohawks. This was the reason for the conference.”24

With French and Indian attacks increasing in New England, and with rumors of incursions down Lake Champlain and the Hudson River, The Albany Convention took several actions to bolster their defenses. On September 4, 1689, they resolved to build or renovate forts in the county’s various neighborhoods, including Saratoga, Half Moon, Papscanee Island, Bethlehem, and Kinderhook.25 They also ordered a head count of their several militia units.26 Military services required a flow of revenue “for ye maintaining and paying of [ ] men in this juncture of time for our Defence against ye french, since by the Present Revolutions we can expect no releef or assistance from our neighbors according to there letters sent hither.” As such, the Convention requested subscription donations, “oyrwise that it will be paid by a generall Tax out of ye whole County.” All told, the convention raised over 350£ through the subscription drive.27

LEISLER’S RESPONSE . These measures were all in addition to their request for support from the evolving Leisler government down in New York.

19 Livingston Records, 149–50.

20 James Otis Lyford, ed., and the Concord, N.H. City History Commission, History of Concord, New Hampshire (Concord, 1903), 82–84; C.E. Potter, History of Manchester, Formerly Derryfield, New Hampshire (Manchester, 1856), 96; Charles Edward Beals Jr., Passaconaway in the White Mountains (Boston, 1916), 77–101.

21 Livingston Records, 151.

22 Ibid., 148, 152, 155.

Cocheco Massacre: Abenakis attacked the settlers of Cocheco (Dover) New Hampshire on June 28, 1689, killing Major Richard Waldron in revenge for his mistreatment of Natives following King Philip’s War. New England colonies responded by sending delegates to Albany that September in hopes of enlisting an alliance with the Iroquois. (Wikimedia Commons)

23 Ibid., 158.

24 Ibid., 151n.

25 DHNY 2:88.

26 Ibid., 91.

27 Ibid., 93–96.

Leisler’s response was less than hoped. When express messenger Johannes Beekman returned to Albany, he reported Leisler had objected to his being a civilian, saying “yt he had nothing to doe wth y e Civill Power—he was a Souldier and would write to a Souldier.”28

As recorded in the Convention’s minutes: “Resolved since Capt Leysler and ye Military officers of ye Citty and County of N: Yorke have not been Pleased to Return y e Least answer to ye Convention upon there Letter and Resolve ye 4th Instant but sent a Letter to Capt wendel & Capt Bleeker signed by Leysler alone which is openly Read, ye Purport of which Cheefly tends to Desyre them to Induce the Common People to send Two men to assist them in there Committee.” Leisler did, however, provide Albany with some ordnance and powder.29

Recounting the episode, Prof. Allen Trelease notes the Convention “swallowed their pride” by requesting Leisler’s assistance, “but when he demanded their submission in return, the magistrates looked elsewhere.”30 That elsewhere was with the same neighboring New England provinces that had recently sent delegates to Albany seeking assurances from the Iroquois nations. The Convention on September 23 drafted requests for support from Connecticut and Massachusetts Bay. They also encouraged as much assistance as possible from the Mohawks, Esopus, and Schaghticoke Indians.31

It wasn’t until a month later, on October 24, that the Convention reported receiving answers. Boston declined to send any reinforcements, citing their own “p’sent Circumstances” and “ye great distance.” Connecticut was more encouraging. “Robert Treat Esqr Govr of Conetticut doth answer our Letter sent him by Capt Bull,” reports the Convention’s minutes. Treat and the Connecticut General Assembly offered “to send us about eighty souldiers with there officers as soon as they can effect it, and are endeavoring to Procure Capt Bull to be there Capt.” In an apparent reference to Leisler’s refusal to send troops, Gov. Treat and his legislature wrote that “they think strange thatt none of our oun neighboring Counties should Releave us.” Members of the Convention accepted Connecticut’s offer, but with a key provision: “Provided they be under Command and obey such orders and Instructions as they shall Receive from time to time from ye Convention of this Citty and County.”32

Down in New York City, Jacob Leisler had already heard of Connecticut’s offer to Albany. Connecticut had decided to recall the assistance they had offered to New York and re-appropriate it instead as part of their assistance to Albany. In a letter dated October 10, 1689, Secretary John Allyn informed Leisler that the Connecticut General Court had decided “to call in that ayd of ten souldiers or their pay, wch we hauv hitherto granted you for the secureing of the forte at Yorke.” Allyn explained “that we have been & are now at great charge and expences many wayes, by reason of the Indian war, & the necessity of Albany who dayly expect to be invaded by the French, to whome we purpos to send som reliefe.”33

Leisler didn’t take this very well. Connecticut’s offer to send troops to Albany, while withdrawing others from New York, “enraged Leisler,” writes David Lovejoy, “and commenced a bitter feud between his government and that colony’s which lasted for some time, in fact affected the course of events for the next few years.”34

Albany, controlled as Leisler saw it by a nest of liberal Cocceian Calvinists and Jacobites, quickly became in his mind a threat to his effort to preserve New York province for England’s new monarchs, even though both claimed to be working toward the same stated end. Leisler’s resentment comes out in a particularly pointed letter to Boston dated October 22, 1689, in which he singles out Albany resident and Convention recorder Dirck Wessels ten Broeck:

I perceive also your great & extraordinary charges & your uncomfortable warre with the Indians your enimies discourages me partly of the expectation the people of Albany have of some assistance of men for this winter being in Just fear for some attack & never in a worse posture of defence then now, their fort being in possession still of the old late King James souldiers, . . . I am informed your honor has received a par’lar letter from a vessel then broke [Wessel Tenbrook] of Albany of which I desire your honor for a copie, he is a persone who has formerly professed popery, & recanted a protestant & been employed by our late papist Governor dongan, for ambassador to Canada & understand not one word French, for which ambassador he has been well rewarded, by both parties being a mistery to many, he is recorder at Albany in noe quality for that office he has

occasioned fourty miles from Albany towards the french to build a fort upon his land where he has send 12 men to guard it, who must be a sacrifice if they come & the fort a nest to the enemies as penaquide was, our committee & military have voted 50 men to be sent up for assistance at Albany, as per enclosed appeares.35

Dirck Wessels owned a share of the Saratoga patent where the fort mentioned by Leisler was built. As ten Broeck family genealogist Emma Runk notes, Leisler was following his customary tactic of accusing political enemies of popery.36 It was Leisler’s similar political-religious accusations against New York Alderman Nicholas Bayard and Mayor Stephanus van Cortlandt that resulted in their flight from Manhattan upriver to Albany in July.

In order to underscore their loyalties, the Albany Convention on October 25, 1689, “Thought Convenient that all there Majts Justices of ye Peace & Commission officers doe take ye oath of allegiance to there Majes William and Mary king and Queen of England France & Ireland & Defenders of ye faith.” Dirck Wessels administered the oath to Mayor Peter Schuyler, following which Schuyler presided over the oathtaking by others. The Convention also resolved to administer the oath to “ye Inhabitants of ye Citty & County of Albany & souldiers of there Majts fort.”37

At the same meeting, the Convention “resolved yt Capt kilian Van Renselaer & Capt gert Teunise be deputed to goe to ye Govr and Councill of Connecticut and to Return our hearty Thanks for there kinde Letter of ye 15th Instant wherein they signify yt they will send about 80 men besides officers for our Releefe.”38 Gerrit Teunisse was quite familiar with the path to Connecticut from prior trading activities and his service as

28 Ibid., 92.

29 Ibid.

30 Trelease, 299.

31 DHNY 2:96–97.

32 Ibid., 98.

33 Ibid., 34.

34 David Lovejoy, The Glorious Revolution in America (New York, 1972), 313.

35 DHNY 2:38.

36 Emma ten Broeck Runk, The ten Broeck Genealogy (New York, 1897), 16.

37 DHNY 99–100. One of the over two dozen soldiers at the fort refused to take the oath.

38 Ibid., 99–100.

Gov. Andros’ delegate there during King Philip’s War over a decade earlier.

One day later, the Convention drafted a letter to Connecticut, in which they spelled out orders “yt Capt. Renselaer and Capt. Gert Teunise be Commissionated to goe thither and Return our Thanks and accept of ye 80 men & Endeuor to have them hither with all speed, who are to submit themselves to ye ordrs & directions of ye Convention.”39

Tension was clearly rising between Leisler’s regime and Albany during the fall of 1689, and the presence of New York fugitives Stephanus van Cortlandt and Nicholas Bayard there certainly served to inflame this anxiety. Judging from the many long diatribes penned by Bayard, he most likely fed his Albany hosts with a distorted account of the ongoing rebellion in New York. While everyone waited for an official new governor to arrive, he wrote, “several threatenings where made by the sd Leyseler & his crue forceably to fetch the sd Collonel [i.e. himself] wth severall of the Chief Magestrates & officers from Albany, and by sending of severall of his Creatures and seditious letters made all pressures & endeavors to desquiet and unhinge all mannor of Governmt in that County of Albany and in the county of Ulster, insinuating and intising the ignorant and meane people of those Counties to the like sedition and rebellion against the established authority.”40

Another complication facing the Albany Convention was handling the loyalty of their own members. This was particularly delicate in the case of Lieut. Jochim Staats, son of long-time colonist Major Abraham Staats. Jochim and his brother Samuel were in the process of negotiating with Kiliaen van Rensselaer for the purchase of some Rensselaerswijck farms. Samuel had moved to New York City and later became a member of Leisler’s council.41

Minutes of the Albany Convention for October 28 for the first time address suspicions that Jochim’s loyalties were shifting. Jochim had been among those delegated to deliver communications between Albany and Leisler, and his fellow burghers apparently had received information that had them concerned. It was no time, they thought, to swap in a new untested administration:

The Convention writt a letter to alderman [Livinus van] Schayk and Lieft Staets putting them in minde of what they had writt yesterday Concerning ye Reports of Leyslers Intentions to

send up armed men to overthrow ye government of this Citty, and that they would endeavor to prevent it as they loved ye Peace of this Citty, and withall Informed them that we hear by a Prisoner come from Canida yt ye Indian Prisoners were come from france with ye govr of Mont Royal and yt ye govr of Canida and diverse officers went to france, & therefore consider in what a Condition we would be with ye Indians if a Change of Magistrates and a Subversion of ye government should at p’sent be made.42

These concerns received further discussion on November 4, 1689, with fears voiced over Leisler’s intent “to send up a Compe of armed men to make themselfs master of there Majts Fort of Albany and of ye Citty turn ye government of this Citty upside doune & Disturbe ye Peace and Tranquility of there Majts King William & queen Marys Leige People.” Delegate van Schaik reported that he “thought himself obliged” to deliver the Convention’s communication. Lieut. Staats, however, was conflicted. “Jochim Staets Replyed [to van Schaik while still in New York] he knew not what to doe, They would have him Capt of yt Company that went up to Albany which was to Lye in ye fort.” Following the loyalty oaths secured from the soldiers at Fort Albany, the Convention had named Capt. Sharpe as the fort’s commanding officer. Staets informed van Schaik that Leisler “would have Sharpe out, & if I will not accept of itt, they will putt in Churchill, methinks it is better that I accept of itt then that such a Vagabond as Churchill should have ye Command.”43

Van Schaik reported that after he delivered the Convention’s message to Leisler, “Jacob Milborne Replyed with Consent of ye oyr Persons Conveined yt time that he would goe up to Albany & see the fort there better Secured.” The alderman added that he believed Leisler was “fully Resolved to Send up men hither to Disturbe the People of Albany,” adding that he overheard Leisler using his oft-used tactic of calling Capt. Sharpe and his troops “Papists all.”

Reaffirming their solidarity to their own interim government, the Albany Convention resolved “to acquaint the Burgers and Inhabitants of this Citty by the assistants of their Respective wards how yt we have Received Information from N: Yorke that there is a Compe of men comeing from thence, who Intend to Turn ye governmt of this citty

upside doune, make themselfs master of ye Fort and Citty, and in no manner to be obedient to any orders and Commands as they should Receive from time to time from ye Persons now in authority in this Citty and County.” Convention members were especially concerned that this would undermine the delicate relationship with their Iroquois trading partners, resulting in the Five Nations defecting to the French in Canada.44 In one of his inflamatory writings dated November 13, 1689, Col. Nicholas Bayard, who returned to New York from Albany in late October, reported on Leisler’s northern bid: “Some few days after the Coll’s returne from Albany, a party of about 60 armed men under the Command of Jacob Milborn, were sent up to Albany by the sd Leyseler and his associates under a faire pretence of assisting that County agst any incursions from Canida, but as it afterwards appeared only contrived for to unhinge all manner of Governmnt there, and to inthrall that County.” Instead of offering reinforcement, Bayard said, “sd Jacob Milborn at his

39 Ibid., 102.

40 DRCHNY 3:645.

41 DHNY 2:45.

42 Ibid., 104.

43 Ibid., 2:106–107. Lieut. William Churchill (or Churcher) was a local New York militia officer loyal to Leisler.

44 Ibid., 108.

Requesting Reinforcements: When the Albany Convention requested defensive assistance from Jacob Leisler, the New York rebellion leader responded that he would send up an armed contingent, not to provide reinforcements, but to take control of the city and its fort at the top of Jonkers (State) Street. (Wikimedia Commons)

arrivall at Albany endeavored imediately to raise all the people into a Rebellion against the authority, whoose Commissions, he declared, where utterly void & of no effect, since they were graunted under that unlawfull King James (altho’ the sd authority had newly sworne faith & allegiance to their now Mayties King Wm and Queen Mary).”45

Bayard also included in his “Narrative of Occurrences” a copy of Milborne’s notice to Hudson Valley inhabitants. Claiming that the popular vote from the New York City area gave them governance authority throughout the province, including Albany County, Milborne proclaimed, “These are to desire and warne all the Inhabitants of Kinderhoek and places adjacent that they do forthwith repair themselves to the Citty of Albany for to receive their rights and Priviledges & Liberties in such a manner as if ye Raigne of King James ye second had never bene nor any of his arbitrary Commissions, nor what his Governrs have done had never past.”46

Albany’s main objection to the rumored motives of Milborne and his troops was doubting their “Intent to assist us as neighbors, and to obey the Convention, and not to turn ye government of ye Citty upside doune.”47 Redoubling their effort to gain popular support for their efforts, the Convention “Conveined in ye Citty hall by Bell Ringing” all the “Burgers and Inhabitants” in earshot to decide how to handle the predicament. Following a presentation of the Convention’s concerns, the gathered populace “agreed and Consented to ye sd Articles, acknowledging ye members of ye Convention for their Lawfull Magistracy in their Respective and Places.” Forty of the “ye Inhabitants Principall men of ye Toune” signed the resolution supporting the Convention.48

Three days later, the Convention took steps to reinforce their fort both physically with repairs and administratively by assigning Mayor Peter Schuyler to take command of the king’s troops there, with assistance from Lieut. Sharpe.

With threats looming from the north, the Albany Convention had sought assistance from three separate bodies politick: Massachusetts Bay, Connecticut, and New York City. As we have seen, Massachusetts offered moral support but no manpower. Connecticut proffered eighty soldiers plus officers and accepted terms that they would follow the orders of the Convention. Capts. Kiliaen van Rensselaer and Gerrit Teunisse Van Vechten had not yet returned from their

Civic and Military Leader: Pieter Schuyler was not only Albany’s first mayor, serving during the Leisler Rebellion period, he was also the city’s top military officer. When Leisler threatened to dispatch troops to take over the Albany fort, Schuyler took up residence there to block the attempt. (This sketch from Wikimedia Commons is adapted from Nehemiah Partridge’s early eighteenth-century painting.)

mission to thank the governor and General Court at Hartford and escort the reinforcements back to Albany. In contrast, Albany’s request to Leisler, although originally rejected, resulted in him leveraging the appeal to bring Albany under his control.

November 9, 1689. As it turned out, Leisler’s troops under Jacob Milborne arrived before Connecticut’s. Convention minutes reveal that a fleet of three ships anchored in the Hudson alongside Albany on November 9, 1689, setting in motion a long day of political posturing. A delegation from the Convention boarded the ships and asked Milborne and Jochim Staats their business. Milborne asked “if the fort was open for his men to march in that night.” He was told no; the fort was under the command of Major Schuyler.

Milborne, however, was invited into the city, and he took advantage of the opportunity to plead his case with the populace. According to the Convention minutes, Milborne in his oration told the people “That now it was in powr to free themselfs from yt Yoke of arbitrary Power and Government under which they had Lyen so long in ye Reign of yt Illegall king James, who was a Papist, Declareing all Illegall whatever was done & past in his time, yea the Charter of this Citty was null & void Since it was graunted by a Popish kings governour.”49

Assuming the mantel as Convention spokesman while Schuyler maintained his post at the fort, Recorder Dirck Wessels ten Broeck responded to Milborne’s oration that the Convention’s government was by no means “arbitrary.” Quite the contrary, he said, “God had Delivered them from that yoke by there Majesties now upon ye throne, to whom we had taken ye oath of allegiance, for we acted not in king James’s name but in king William & queen Marys

& were there Subjects.”50

As with Kinderhook, Milborne also made efforts to enlist residents of Schenectady to support Leisler’s government, sending them a similar proclamation. To which Schenectady resident Adam Vrooman answered bluntly, “The Indians lie in divers squads in and around this place and should we all repair to Albany great disquiet would arise among the Savages to the general ruin of this Country.”51

Learning of this development, the Albany Convention became further convinced that Milborne’s (and Leisler’s) purpose was less an offer of military assistance and more a political power grab that did nothing to help them withstand potential attacks from Canada. “It is Plainly Evident ye sd Milborne Designs ye Subversion of ye governmt.”52 Albany’s distrust was further reinforced when they obtained a copy of a document, drafted in New York on November 2 prior to Milborne’s departure, designed to further entice Schenectady to Leisler’s side. This letter drafted by Leisler deputy Hendrick Cuyler promised to break Albany’s traditional monopoly on the beaver pelt trade and share that priviledge with residents of the farming community on the Mohawk

45 DRCHNY 3:646.

46 Ibid.

47 DHNY 2:109.

48 Ibid., 110–111.

49 Ibid., 114.

50 Ibid.

51 Ibid., 117.

52 Ibid.

river. “We have this day resolved that you shall have no less Priviliges than those of Albany in Trading and Bolting,” he wrote. “We therefore request that you will exhibit all Dilligence in repairing together to Albany to welcome said Milborne.”53

As the events of November 9, 1689, finally quieted down, Milborne and the Albany Convention had seemingly reached an impasse. In a timely coincidence, Albany’s delegates to the east arrived back that night or early the next day and broke the stalemate, at least temporarily. “Kiliaen van Renselaer Esqr Justice of ye Peace and Capt. gerrit Teunise who were sent by ye Convention to ye Collony of Conetticut concerning y e men which that Collony by ye joynt Concurrence of ye Collony of Massachusetts had Promised to send hither for our assistance being Returned brings a letter from ye govr and Councill there, how that they are Resolved to Raise 80 men wth there officers forthwith, that they may be upon there march hither upon munday ye 18th of novembr.”54

The two Convention delegates had negotiated final details of the arrangement with the Connecticut government. They agreed to provide the troops with “ammonition[,] meet[,] Drink and Lodgeing Sufficient” as well as to pay the officers a daily stipend. They also promised to provide medical services “If any of sd officer or Souldiers should be visited with Sicknesse or wounde.” They agreed to supply a canoe for crossing the Westenhook (Housatonic) River, and finally to keep the soldiers’ weapons in good repair. Convention members ratified the agreement with no recorded discussion or dissent, possibly due to its juxtaposition with Milborne’s attempt to take control of Albany and its fort.55

In addition to reporting on the Connecticut agreement, the two emissaries also gave a report of attitudes among a community south of Albany. “The Said Mr Renselaer & Capt Teunise Report that when they come by kinderhook [they] founde ye People Very much Inclined to mutiny who were Prepareing themselfs to come hither by Reason of a Letter which they had Received of Jacob Milborne to come up to albany in all Speed to Receive Priviledges and Libertyes, so yt they had much adoe to stop them[,] however some Came.”56

November 10, 1689. With the Connecticut report in hand, the Albany Convention, again chaired by Recorder Dirck Wessels, reconvened on Sunday,

November 10, 1689, to continue discussions with Jacob Milborne. After Milborne advised the Convention they should pay the New York soldiers for expenses incurred, “the Recordr Replyed that that was Repugnant to there Resolution.” When the Convention challenged Milborne’s presumed authority to take control of Albany’s fort, he showed them a letter signed by over two dozen members of Leisler’s New York government. “The Recordr told him that Such a Commission graunted by a Company of Private men was of no force here, and that he had no Power to doe or order any affaires in albany, but if he could shew a Commission from his Mats king william our Leige Lord, then they were willing to obey it.”57

Hoping his letters to Schenectady, Kinderhook, and other outlying towns had helped his cause, Milborne once again took his arguments to the people at large. “The Sd Milborne went on and made a long oration to ye Common People which were got together in ye Citty hall.” Claiming that the 1686 City Charter, granted by Governor Thomas Dongan, was suspect as part of King James’ popish government, Milborne suggested “that there ought to be a new Election of Magistrates &c and many oyr things to Stirr up ye Common People.”58

Another selling point made by Milborne was that “many Patents of houses and lands” approved by governors appointed by the Catholic James might now be revoked by administrations appointed by Protestant William and Mary. As many of the Albany Convention members were owners or partners in various land grants, it is easy to see how Milborne’s arguments succeeded to some degree in stirring up the poorer, working-class inhabitants against them. “The anti-Leislerians defamed the middling Dutch farmer with economic and class epithets,” points out Firth Haring Fabend, “because he represented a threat to what they most wanted to defend, and what they feared, in the end indefensible: their accustomed access to privilege.”59

An unnamed spokesperson for the Convention, likely Recorder Dirck Wessels again, responded in the public forum that not only were Albany’s civic leaders chosen by “a free Election,” but Milborne’s motives had now become quite clear. “Sd Milborne by his Smooth tongue & Pretended Commissions did aim nothing else but to Raise mutiny and Sedition amongst ye People.”60

Convention minutes naturally present these events from their own perspective, but

it is clear that sentiments among the populace were mixed. According to minutes from November 11, “The Convention sent messengers thrice to ye People Convened att ye Citty hall to Disperse themselfs and goe home, they nevertheless went on and choose ye sd Jochim Staets to be Capt of yt come from N: Yorke by syneing there names to near a hundred Persones, most youthes, and them that were no freeholders which sd Place ye sd Jochim Staets did accept contrare to ye order of ye Convention of which he was a member.”61

Milborne was successful in inciting a significant level of distrust against the Convention. “Yea ye People were so Rageing and mutinous that some of ye Convention being in y e Citty hall, were forced to withdraw themselfs being threatened and menaced that they were in danger of their life.”62 Among those siding with Milborne were Pieter Bogardus, Harmon Gansevoort, and Gabriel Thommase Stridles.63

Further emboldened by his success with the “Common People,” Milborne on November 12, increased his pressure on the Convention to relinquish the fort to him and Jochim Staats. But the Convention membership held firm. They would accept assistance from the New York contingent only if “they should be under ye Command of the Convention,” the same condition they placed on Connecticut’s offer of troops. Eight Convention members accepted the challenge of negotiating terms based on this condition. Included in the eight were Mayor Pieter Schuyler and Kiliaen van Rensselaer.64

Milborne and the eight Convention members continued dickering over terms of an agreement over the next couple of days, and both sides focused efforts on convincing the populace of their respective arguments. At one point, Dirck Wessels accused Milborne of bad faith bargaining—agreeing at one

53 Ibid., 118.

54 Ibid., 119.

55 Ibid.

56 Ibid.

57 Ibid., 120–121.

58 Ibid., 121.

59 Firth Haring Fabend, “The Pro-Leislerian Dutch Farmers in New York: A ‘Mad Rabble,’ or ‘Gentlement Standing Up for Their Rights’?, in de Halve Maen (March 1990), 9.

60 DHNY 2:121.

61 Ibid., 122.

62 Ibid., 123.

63 Ibid., 132.

64 Ibid., 124–25.

meeting to certain terms but reneging on his agreement when it came time to put his signature on it.65

Milborne Backs Down . Matters escalated close to armed conflict on November 15 when Milborne marched his troops to the gates of the fort demanding Commander Pieter Schuyler surrender it. Schuyler answered “Thatt he kept ye Same for there Majes king william & queen mary, & Commanded them away in there Majes name with his Seditious Company.” Milborne responded by ordering his troops “to Load there gunns with Bullets.”66

In the end, it was the Mohawk Indians who defused the threatened hostilities. They sent word to Milborne that “they were in a firm Covenant chain” with the Albany leadership. The Mohawks announced they would open fire on Millborne’s troops if they advanced further, because “ye People of N: Yorke came in a hostile manner to disturbe their Brethren in ye fort which was for our and there defence.”67 Milborne “at the head of his Compe in ye Presence of a great many Burgers” had no choice but to capitulate. He turned his troops around, “Marched doune ye towne and Dismissed his men.”68

“One of the reasons for Albany’s stubbornness in the face of Leisler’s determination to bring it into line was a fear of what the change might mean to the delicate balance of relations with the Iroquois,” explains Lovejoy. “That the Mohawks appreciated Albany’s tenuous position was evident in their silent threat to Milborne, who was forced to retreat and not very proudly.”69 Milborne certainly failed to comprehend all the dynamics at play. Among these was the Mohawk tribe’s respect for Edmund Andros from his earliest days as governor of New York. Instead of looking down at the Indians as ignorant heathens, he had recognized them as allies and important trade partners, whether Iroquois or Algonquian. In return, the Mohawks gave him a particularly high honor bestowing on him the name Corlaer after the late Arent van Corlaer, the leading peltry trader of an earlier generation.

Mohawk chieftains recognized in Andros someone who would continue the partnership forged by van Corlear and others many years earlier. They were thus completely comfortable with his return as governor of the entire Dominion of New England. When he met with them in September 1688, the