It’s more than seeing what others can’t—it’s having the audacity to bring that vision to life.

The nine changemakers featured in this issue didn’t just dream differently; they defied convention, rewrote rules, and transformed industries. From revolutionizing sustainable textiles to reimagining a more inclusive future for entertainment, each has left an indelible mark on their field. But perhaps more important, they’ve shown us what’s possible when creativity meets conviction.

Their stories are as diverse as they are inspiring. A landscape designer who turns urban wastelands into thriving ecosystems. A textile innovator who’s making fashion more sustainable, one fiber at a time. A toy designer who thinks way out of the box.

To capture their unconventional spirit, we commissioned faculty member Carlos Aponte, Illustration MFA ’21, BFA ’17, to create their portraits. His interpretations don’t just show us their faces—they reveal their essence as innovators and changemakers.

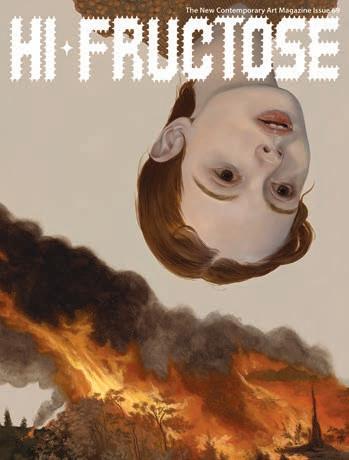

Our cover art, created by Daniel “Attaboy” Seifert, Toy Design ’96, embodies this spirit of boundless possibility. The image suspends us between falling and flying—much like the moment when a bold idea takes flight. Attaboy has also designed a whimsical traveling companion for this issue. Take Huebert with you, snap a photo wherever you find yourself, and share it on Instagram with #WheresHuebert. Selected photos will be featured in our online gallery at hue.fitnyc.edu.

While this issue celebrates many remarkable stories, we know there are countless more being written every day by our alumni. Because being a visionary isn’t about holding a particular title or achieving a specific milestone—it’s about approaching each challenge with curiosity, courage, and an unwavering belief that better is possible.

This text was drafted with the assistance of artificial intelligence.

. 24

FAcclaimed landscape

architect Kathryn

Gustafson, Fashion Design, creates innovative and beloved public spaces around the world

ind the soul of a place, and create a landscape that fits it perfectly. Be true to its history, culture, and natural environment in every element (composition and structure, stone, plants, water), so it seems to simply

belong there. And provide beauty and moments of surprise, bringing visitors back again and again to discover something new. That’s the philosophy of the renowned landscape architect Kathryn Gustafson. Inspired by art, she favors paths that disappear intriguingly around a bend; trees that frame a lovely view, as in a painting; and varied perspectives: up, down, near, far. When it all works, she says, the journey through a landscape is nothing less than sensual, emotional, even poetic. For 40 years, people have loved the public spaces she’s built all over the world.

In 1971, fresh out of FIT, Gustafson headed to Paris and worked as a fashion designer. She gave it up after six years (“too fast, too many collections, the ethics were terrible”) and spent a winter in a beach house in Seattle, taking stock. “We were all hippies, just hanging out,” she recalls. “Someone said she was going to do landscape architecture, and my head exploded. I’d never thought of it before, but I just knew. I’m so lucky I found this field. It fits me like a glove.” The switch wasn’t strange, she says: “Design is design. It comes from the same brain. Only the materials change.”

Also, of course, scale and time. If fashion is fleeting, urban landscapes are enduring. Gustafson’s work is literally set in stone. Leading teams of architects, landscape architects, engineers, and horticulturists, she designs and

builds large, sometimes massive public sites in cities around the world. Each landscape not only becomes a vibrant destination for many thousands, even millions,ofvisitors,but it also claims a place in the minds and lives of those who walk its paths in every season, meeting under its shady trees and taking in its views and changing light. Every detail of the visitor’s experience, even beyond conscious thought, is shaped by the landscape architect’s vision, skill, and, yes, art—from the curve of a fountain to the color of the stone.

As a founding partner of two firms, GP+B based in London and GGN in Seattle, from which she’s retired, Kathryn Gustafson has aninternationalportfolioofhigh-profile projects, from the Diana, Princess of Wales Memorial Fountain in London in 2004 to the National Museum of African American History and Culture site in Washington, D.C., completed in 2016. There are projects all over Europe, as well as in Hong Kong, Singapore, Seoul, Beirut. Budgets range from $2 million to $100 million. Her lifetime of achievements in the field was recognized in 2019 with the Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe Award, the highest honor the International Federation of Landscape Architects can bestow.

Since 2018 (with pauses for the pandemic and the Paris Olympics), she’s been restoring the site around the Eiffel Tower, one of

BY LINDA ANGRILLI

the world’s most iconic landscapes, attracting 10 million visitors a year. The project was awarded through a major international competition, which required designing six separate areas totaling more than 130 acres, with the tower at the center. Gustafson’s plan won a prestigious gold Global Future Design Award in 2024.

Because of age and heavy use, the historical areas needed restoration, and the visitor experience, marred by overcrowding and lack of services, needed improvement. Ecological sustainability, biodiversity, and accessibility were critical considerations. In addition to renovatingsoils,pathways,surfaces,and walls, Gustafson’s plan calls for a host of improvements, including new vantage points for viewing the tower itself; flexible spaces foreventslikeconcertsandexhibitions; and necessities like baggage check, dining

services, and restrooms, tucked discreetly among the trees.

It’s a complex, multilayered project that’s not only culturally and politically sensitive but hugely expensive. “It’s a pain,” Gustafson says. “And it has to be drop-dead gorgeous.”

The first phase, around the Fontaine de Varsovie in the Jardins du Trocadéro, was completed in March 2024. In this phase, the firm restored soils, lawns, and pathways; planted 26 cherry trees and 15,000 shrubs and perennials; and provided visitor services while controlling the flow of pedestrians— nice for tourists and necessary to avoid soil compaction.

Of the six areas designed for the competition, Gustafson thinks four will be built, because of costs and the byzantine politics surrounding a site that arouses such passion. “So far, I’ve been successful,” she says. “One of my worst critics saw it and said, ‘I didn’t know it could look like that!’”

in some ways, fashion prepared Gustafson for landscape architecture. Her easy chic and her no-nonsense confidence seem suited to either field. By the time she got her master’s at the École Nationale Supérieure de Paysage (ENSP) in Versailles, she had her FIT education and professional design experience. She’d been making clothes since she was 13. “I already had my style. To a project presentation at ENSP in the disco era, I wore a silver suit with a turquoise piece on it; I had made a model of a landscape in gray clay with a sparkly turquoise river. The teacher said, ‘It’s the same.’”

Gustafson says nobody taught her how to design, but FIT equipped her with the skills to build her own designs, like drawing and how to use different fabrics. She learned how knitting machines work, and she found art history compelling. “I absolutely loved FIT, doing patternmaking, draping, things like that. I learned technique,” she says.

A vivid memory: “I walk into the studio, and there’s this man, the most gorgeous thing I’d ever seen. He was Guatemalan, 6 feet tall, in leather hot pants, with thighs to die for. He used to dance on Broadway. He became my

best friend. He graduated before me and went to Paris and found us an apartment. As soon as I graduated, I got on a plane.”

She adored design but hated the industry. She left when the company where she worked copied a fabric rather than buy it from the makers. Landscape architecture suited her. Growing up in Yakima, Washington, she skied and rode horses and, with her four siblings, was expected to help in the family’s garden, where her father tended the trees and shrubs, and her mother the perennials and roses. Water was scarce, but the valley turned a vibrant green when irrigated for farming. “You were highly aware of the value of water,” she says. She often designs fountains and, lesson learned, uses precious resources with care, reusing materials when possible. She traces the undulating forms often seen in her work back to the mountains of her girlhood.

to create a successful public site , says Gustafson, landscape architects need to understand the total environment: natural, political, and cultural. “Working in different countries, whether it’s Korea, Japan, or Australia, how do you understand those sensibilities and make a place that fits? If you don’t, you’re just building a chain hotel that’s the same everywhere.”

She studies each site’s geography and history (“back to the Ice Age”), culture, and existing materials—native plants, local stone, textures, colors, the shapes in the composition. If it sounds like she’s talking about art, that’s because she is. “I chose to do landscape architecture as an art form,” Gustafson says. In a talk about her work, she told students she admires J.M.W. Turner’s paintings, where, in the distance, “[t]here’s always someplace to go. The sun or moon or light is an object of desire.” Her landscapes create a similar sense of moving toward a destination, a place beyond what’s visible.

Her devotion to art, especially sculpture, can be seen in her method of beginning each project by modeling her design in clay. This lets her understand how it works in a way virtual representation does not. It’s then

The city of Paris is planning for a future of resilience, increased biodiversity, and reduced pollution, all requirements for the design competition to restore and renovate the historical site around the Eiffel Tower. For their winning entry, chosen from 42 submissions, GP+B proposed a unifying axis of greenery with the tower at its center, connecting the area’s key historical sites, including the Palais de Chaillot, the Champ de Mars, and the École Militaire. The area is now closed to traffic except for emergency vehicles and buses, so the plan turns the traffic circle at the Place du Trocadéro and the Iéna Bridge over the Seine into green spaces for pedestrians. New views of the Eiffel Tower are created, along with spaces for pleasure and contemplation. Phase 1, the renovation around the Varsovie Fountain, was completed in 2024.

rendered in plaster and digitized in 3D, and the dimensions are enlarged to the scale of the site. The limestone, granite, or marble (for walls, paving, fountains, and more) is then cut with computerized machines. This might be done in India, Italy, or China, but for sustainability, she prefers it to be quarried and cut as near to the site as possible, to keep shipping distances to a minimum.

For Gustafson, landscape architecture is about creating a journey of discovery. “It’s a walking art. As the architect, you figure out how people move through that experience

something new,” she says. “I’m not interested in repeating something that’s been done, either by myself or somebody else.”

An innovative feature she did in 2000 for the American Museum of Natural History in New York was a courtyard covered in a quarterinch sheet of water with jets that kids can splash in. “It made so much sense, but it had never been done before. Now it’s everywhere in the world.” (A bonus in New York: At night, the Hayden Planetarium is reflected in the water.)

Once built, public sites require maintenance, which is beyond the architect’s control. If a donor doesn’t provide a big endowment for upkeep, Gustafson says, “it’s a crapshoot.” Budgets, politics, and changing priorities can get in the way. Her solution: “Build a place so loved that people protect it. They say, ‘This is my neighborhood, my park, my life.’ They pressure the city or form associations that maintain it. A huge goal of my work is to make a landscape that grabs people, holds them.”

so they’re constantly discovering. One of the main ways you do that is by changing what their eye sees by moving them up or around through space. You also take advantage of seasonality—the extraordinary changes in light, colors, textures, and temperature. It’s the same place, but the experience, the activities, become different.

“Then there’s the technical part: How do you build it, make sure the plants grow, use the right resources? People don’t appreciate how complicated it is.”

Though her work has a certain signature—“a basic simplicity, pretty stripped down and minimal, not too many different materials. Very sculptural and compositional” —it’s never the same. “I always try to do

One such beloved place is the polished black wall outside the National Museum of African American History and Culture. It’s gleaming and smooth, evoking the water that Africans were forced to cross when they were brought to America; the rounded edge is almost muscular, like a shoulder, honoring the labor of the enslaved people who built much of Washington’s infrastructure. “It’s got a lot of symbolism,” Gustafson says. But it’s also practical. “It takes the sun; it warms up. Food trucks are there, and everybody sits on it. It’s become the place where people meet in D.C. Who would have guessed?”

Another memory: “I was in Jamaica, and a young woman, maybe 18, asked what I did. When I said landscape architect, she asked what I’d done. I mentioned the museum. She looked at me and said, ‘Did you do the black wall?’ I said yes.” Gustafson smiles. “The black wall.” ■

2006

This early but defining project for GP+B developed a former gasworks outside Amsterdam into a park and recreation area, providing large public event spaces as well as intimate natural landscaped areas with native plantings. It’s considered a model of brownfield reclamation, transforming an abandoned industrial site into a vibrant gathering place for surrounding communities.

“Many of the principles of sustainability that we use today were established then,” Gustafson says.

The project was comprehensive, involving historical restoration of buildings, innovative soil and water

WASHINGTON, D.C., 2016

Designing the site around the iconic museum created by David Adjaye and Phil Freelon had deep significance for Gustafson. First, there was the symbolic presence of the museum amid so many monumental institutions of American history, civic life, and culture—the Washington Monument, the White House, the National Mall with its string of distinguished museums. “The museum is about diversity and joy,” she says. “As an architect, you want to respect the historical area,

reclamation measures, and engagement of many stakeholders to ensure that city and community needs were met. The site now features a cultural center for the arts in an ecologically sustainable environment.

Redevelopment of this brownfield site was complicated by the discovery of huge amounts of toxic material, including cyanide and asbestos. Netherlands law prohibits moving pollution to another place, so Gustafson’s team had to find ways to deal with it safely on site, adding five years to a five-year project. They built up berms—raised areas in which the pollution could be contained—and covered them

with clean soil for plants to grow without exposing horticulturists to the contaminants. The berms also provided a sound barrier for the noisy rail line that remained on the site.

During the planning stage, Gustafson and GP+B partner Neil Porter worked nightly from Seattle with engineers in London to calculate the amount of soil needed and to incorporate it into the design. “It was truly an engineering/landscape design collaboration that really made a difference in treating the pollution,” she says.

and you want it to seem like your site has always been part of it.”

There were also practical matters. Constitution Avenue, where the museum is located, floods every year, so Gustafson’s team built entrances high above flood level so art can be moved in and out without getting wet.

Security was a huge concern. “You’re trying to make an open, welcoming space, but you need anti-bomb walls all around that trucks can’t get through. We built stepped walls covered with plantings so you can’t see them, but I can tell

you, it’s totally bulletproof.”

She wanted to incorporate the idea of crossing water, an experience of all Africans coming to America. When her water feature fell to the budget ax, she instead designed a glass-smooth black wall, 5 meters wide and 300 meters long, that evokes water.

wild wild

think like a toy designer,” says Daniel Seifert, known professionally as Attaboy. “I try to maximize the fun.” His boundary-demolishing oeuvre encompasses games, books, art toys, cartoons, fine art,

and an influential magazine. Fun is the common thread, he says. “The act of play is crucial to the way I operate.”

Attaboy’s annual Game of Shrooms began with a prompt he circulated on social media in 2019. Each year on a different day, artists worldwidemake—andhide—smallworks of art for an interactive Easter-egg hunt that lasts 24 hours. Players hail from Hong Kong, India,Russia,theU.S.,and many other countries. In 2017, Attaboy launched Vampires vs. Unicorns. Funded by a Kickstartercampaign,thisboard game requires players to throw cards, introducing an element of randomness that defies skill and strategy. “The harder you try, the worse you do,” he says.

His Upcycled Garden art installation features fungi made ofrepurposedmaterialslike old pizza boxes and newspapers, all painted riotous DayGlo colors. Dreamed up in the gloom of the pandemic and designed to biodegrade, the modular, evermutating piece has toured throughout the U.S. This year, it sprouted up at the Richmond Art Gallery in Richmond, California, where Attaboy lives with his spouse, Annie Owens.

Perhaps his best-known project is the quarterly art magazine Hi-Fructose. Co-founded in 2005 with Owens, the publication has global distribution and over 2 million followers on Instagram. It’s a showcase for artists both storied (Shepard Fairey, John Waters) and offbeat (the late trailblazing Japanese painter Yui Sakamoto). In 2019, the mag’s editors branched out into book publishing with the handsome volume Hi-Fructose: New Contemporary Fashion, a review of cutting-edge garments.

“For me, the future is now. So I’m going to fill it with wide-eyed curiosity, open-minded possibilities, friends, silliness, and empathy, squeezing juice from a raisin if I have to; because old age isn’t guaranteed.”

ATTABOY

“He’s a born visionary,” says Judy Ellis, retired chair and founder of the Toy Design program. When he was a student, she says, “Daniel’s ideas stood out for their whimsy and brilliance,blendingstorytelling, art, and play in ways that defied convention. His ability to leap fearlessly into the unknown and inspire others to do the same has made him a pioneer in fostering joy and creativity worldwide.”

After graduation, Attaboy worked in the Milton Bradley and OddzOn subsidiaries of Hasbro for four years, designing toys like Fishin’ Around and Jump Rope Rock and redesigning classic games like Cootie and Don’t

BY ALEX JOSEPH

Spill the Beans. But he felt constrained by the toy industry and soon pivoted to making collectible art toys. Axtrx, a 4-inch-tall green vinyl monster, came with a set of interchangeable mouths for different moods.

There’s even more to Attaboy (the more you learn about him, the more his gung-ho nickname makes sense): He’s created cartoons for Cartoon Network, devised funky ice cream flavors for Disney cruise ships, and developed toy prizes for the Chuck E. Cheese pizza chain. In 2013, talk show host WendyWilliamsspottedhishomemade pilot for a TV show that never aired, They Actually Made That, in which Attaboy deconstructs a Mommy-to-Be Doll—a Barbieesque pregnant doll with a spring-loaded baby in her tummy. Williams aired the clip on her show; it now has over 3 million views on YouTube. For a wildly original thinker like Attaboy, creativity has no set goal. “I love people who do things for the sake of doing them,” he says. ■

A Hi-Fructose sampling. In 2009, Seifert and Owens created a tagline for the mag’s can’t-quitepin-it-down scope, the seemingly redundant “New Contemporary” art. Since then, the phrase has started appearing in artist bios and gallery descriptions.

TWith their revolutionary seaweedbased biosynthetic, Keel Labs is poised to transform the textile ecosystem

Aleks Gosiewski ’17 and Tessa Callaghan ’16 have undergone a sea change since winning the inaugural Biodesign

Challenge

in 2016. At the time, their student

project, a yarn derived from seaweed, won the international competition, which envisions the future of biotechnology. Now, less than a decade later, Gosiewski and Callaghan sit at the helm of Keel Labs, a growing sustainable materials start-up headquartered in the heart of North Carolina’s Research Triangle. It is here that the seaweed-based fiber they prototyped back at FIT gets spun into spools of Kelsun yarn. Keel Labs wet-spins Kelsun from a solution made of seaweed extract, water, and a proprietary blend of a few other non-toxic natural ingredients. It is hard to fathom that this seaweed slurry can morph into cream-colored fluff, but such is the wonder of biotechnology. Cottony-soft and eco-friendly, Kelsun debuted on the world stage in 2023, when Stella McCartney featured it in runway pieces during Paris Fashion Week. More recently, it has been used in apparel by the brand Outerknown and the designer Mr. Bailey, as well as in a second Stella McCartney collection. “This is no longer just a concept,” Gosiewski says. “This is something people are actually able to purchase and experience.”

AftertheBiodesignChallengewin— achieved with the help of faculty advisors Theanne Schiros, associate professor of Science, and Asta Skocir, professor of Fashion Design—the student team formed a business named AlgiKnit, raised enough money to hire scientists, and set up a lab in Brooklyn. Those advancements allowed them to push the tech forward and start producingconsistentfiber at the lab scale. In 2022, the business rebranded as Keel Labs, relocated to Morrisville, NorthCarolina,andbegan the work of scaling up the production of Kelsun. They are now closing in on their goal of producing at commercial scale. “When we started, we were measuring our fiber in grams. Now we’re measuring in tons,” Gosiewski says.

As brandsseek to lessentheirplanetary harm, they urgently need eco-friendly replacementsforthepollutingmaterials they use in their products. With Kelsun, the textile industry has a viable new alternative that is low-impact, sustainable, and—most important—easy for mainstream manufacturers to adopt. Many novel, next-gen materials

BY KIM MASIBAY

remain niche products because they require newproductionequipmentandfacilities, Gosiewskiexplains,butKelsunwasengineered to fit into the existing supply and manufacturing systems. Mills need no special technology to use it. “From the outset, we have been intentional about using the existing infrastructure,”shesays,explainingthat Kelsun is a “drop-in replacement” for widely usednon-sustainablematerials:Simply remove the spools of toxic fibers from the machinery. Swap in Kelsun.

Keel Labs is gradually scaling up their manufacturing capacity, so it will be a while before we see Kelsun in the mass market, but longterm, Gosiewski envisions even the industry’s largest brands using it. “Getting them on your side. Working with them. It’s the only way of tipping the scale.” ■

A shift toward human curation and sensibility over just looking at technological advancements and algorithms.”

AAmiyra Perkins, Textile/Surface Design ’10, forecasts for

miyra Perkins can predict the future. As a trend forecaster, she can divine or at least guess with surprising precision what we will be wearing, driving, eating, buying, and thinking months, even years, in advance.

“My sweet spot is about two to five years out,” she says. “Certified futurists can forecast nearly a decade out, but they tend to work in social policy, government.” She doesn’t have enough patience for that. “I need to be in something that I can actually impact a little faster.”

Perkins’ insights do have a rapid impact. She is a senior lead of creative strategy at Pinterest, an online platform where users share and look for images that will inspire them, from food and travel photography to outfit ideas and home decor. She uses her knack for knowing what people will want to help brands create ads that will stand out amid the platform’s sea of aspirational pictures, and she helped develop an annual report of the next big trends called Pinterest Predicts.

Perkins works with some unlikely clients (banks, technology companies, fast-food restaurants), and she finds ingenious, surprising ways for them to promote their services.

For example, in 2023, her team noticed a spate of Pinterest users searching for “deep conversationstarters”and“questionsfor couples to reconnect”—suggesting a desire to “break down walls and form stronger connections,” Perkins says. She sensed this yearning would grow, and Pinterest Predicts named Big Talk one of its top trends of 2024. Then the

team worked with McDonald’s to launch the new Grandma McFlurry, so when people searched anything related to relationships and communication on Pinterest, an ad appeared in their grid featuring an older and a younger woman on a bench enjoying the caramel-drenched ice cream treat. Viewers could then click to book a calendar date with their grandmother to chat over McFlurries.

“We actually had to stop running the ad because they ran out of McFlurries,” Perkins says. It probably helped that “people get hungry when they scroll,” she adds.

Perkins’ work is not mere trendspotting. She observes human behavior and makes leaps—based on what people are wearing, discussing,consuming,andthinking—to imagine where it may be headed in the future. “It’s forecasting: What’s coming, what’s next, why,” she explains. “It’s about being imaginative and willing to have conversations with people who are different from you. It’s about exploring the human psyche.”

Perkins began analyzing human behavior as a textile designer at brands like Gap and Victoria’s Secret. “Color and print tell you a lot about where we’re going,” she says. For example, when customers began turning away from prints after the financial crisis of 2008, she predicted that it wouldn’t take long for

BY RAQUEL LANERI

them to embrace uniform dressing—which happened in 2014. Similarly, a flurry of fall and winter pastels in 2013 clued her in to an upcoming industry-wide embrace of seasonless dressing as a result of climate change. At these brands, Perkins began working on collections 18 to 24 months before their launch; eventually, she found she liked concepting more than actually designing.

In 2014, she began working as a trend consultant for forecaster WGSN, where she learned how to figure out whether “something was going to be a thing or not.”

One trick is the 3-3-3 approach: The trend should be happening in three industries, in three distinct locations, and as a response to three different macro drivers (which can be economic, political, cultural, or environmental).

Recently, Perkins has been tracking the riseoftraditionalism.Shefirstclocked itcirca2017,whenprairiedressesand cottagecore had a moment, and certain subcultures that fetishized slow living—baking sourdough bread, canning, foraging, knitting—began flourishing on the internet. But while most observers saw this shift as a cute aesthetic trend, Perkins sensed something more serious, even sinister. The fact that independent women were flocking to the kitchenandtoward“wholesome”activities was a sign that modern life had gotten too crazy, and when things get crazy, people desire simpler times. “But oftentimes that meant that women were oppressed,” Perkins says. Cut to the rise of “trad wives,” the “manosphere,” and the anti-woke brigade all calling for a return to traditional gender roles, a rollback of diversity, equity, and inclusion programs, and more right-wing politics. “These are all connected,” Perkins says. And she saw it coming. ■

nahita Mekanik believes everyone is an artist. Mekanik is the head of scent design for ScenTronix, a start-up perfumery she launched with artist-technologist Frederik Duerinck. The pair dreamed

up a machine that uses artificial intelligence (AI) to design unique scents tailored for each of their customers—who can then tweak their formulas or imagine entirely new ones.

“The philosophy is that everyone is a creator,” Mekanik says. “We wanted to invite people into this medium of scent, which is not really accessible, and to experience that feeling of making something—which is really powerful.”

Mekanik herself stumbled into scent. Born in Iran, she studied translation in France and worked in retail before landing a job in the U.S. as a project coordinator at the Swiss fragrance company Firmenich. She had a knack for it. “The funny thing is, you’re doing translation work,” she says of interpreting abstract concepts into perfumes.

In 2016, she met Duerinck, who was part of a Dutch collective of artists doing multisensory installations and experiences. The two collaborated on a machine that emitted smells based on music someone would perform in real time. (If the music was mysterious and dark, for example, the AI in the machine would choose a scent that matched that vibe.) Duerinck built the machine, and Mekanik worked on the scent palette it would draw from to conjure its perfumes. “The experience transformed me,” she recalls. “It reignited my long-rooted desire to get into a more artistic expression.”

Two years later, the duo launched ScenTronix. They now have more than a dozen machines all over the world, including in their lab in Copenhagen, the Museum of the Future in Dubai, and The Fragrance Shop in London. They also take machines to events like festivals, parties, and corporate retreats.

This is how a ScenTronix machine works: A customer fills out a survey—either online or in person—with questions about their personality, their aspirations, and their style. It’s more a poetic, artistic exercise than a scientific one. “We don’t ask people, ‘What scent do you wear?’” Mekanik says. “That would have made it too easy.” The results are analyzed by AI to produce three different fragrances, pulling from a palette of 54 building-block scents: from sandalwood to apple, tuberose to “rice and milk.” For $50, the customer receives three 5-milliliter bottles of their custom fragrances along with their formulas, which they can later access and tinker with through their online account, and with the help of a consultant such as Mekanik.

So far 180,000 people have tried the service, and Mekanik says that the company has a 90% to 95% success rate. “Most people like at least one of the scents they’re given,” she says. Beyond giving people the ability to create their own personal fragrance, the process encourages expression and connection.

BY RAQUEL LANERI

“One of my favorite moments was a couple of summers ago, on Mother’s Day. We had a family come into our store in the Netherlands—a father, two kids, and their mother— and they were doing the questionnaire all together,” Mekanik says. “They were saying her answers out loud, and it was such a beautiful, bonding moment.”

Another time, in New York City, a man did the questionnaire and then fell silent when he took a sniff of one of the results that came out of the machine, Mekanik recalls: “I didn’t know if he hated it, but then he said that it reminded him of his father who had passed away six months earlier.”

“That’s the incredible thing about scent,” she says. “It connects you to time, space, all of that—you never know where it’s going to take you.” ■

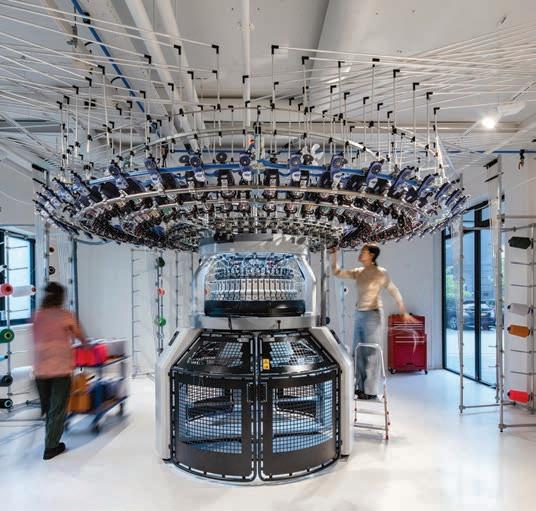

AAlum Borre Akkersdijk created a sustainable way for emerging brands to produce their lines

decade into his career as a buzzy designer of intricate, futuristic 3D knits, Borre Akkersdijk began to wonder: Did the world really need another fashion brand?

The FIT alum had launched his Amsterdam-based clothing line ByBorre specifically to spotlight the groundbreaking textiles he’d been creating since he was a student. The brand’s growing success, including collaborations with Adidas andJapaneseouterwearspecialist Descente, was secondary to Akkersdijk’s main mission: digitizing textile design.

He first developed his signature squishy knits in 2008 using a reprogrammed circular knitting machine meant for making mattresses, an ingenious hack that eventually earned him a 2012 Dutch Design Award.

Over time, the scope of Akkersdijk’s innovative work with textiles evolved to include the supply chain from which they emerged. Building his brand, he sourced ethically made yarns and fibers and sought responsible production partners. He also prioritized fit-to-purpose design to reduce waste from excess sampling and overproduction.

In 2020, a lightbulb went off.

we realized that we can change the industry with the textiles we make.”

The clarity of the answer provided a new mission for the company—and for Akkersdijk himself.

“At the moment, we’re a textile company with a digital tool. I think in the future we’ll be a textile platform where we are a bridge between architects and brands and creators, where creators can design and sell and propose their own textiles.”

BORRE AKKERSDIJK

“We said, ‘What is the core of our business?’” Akkersdijk says. “Is it clothing? Or is it actually our supply chain and our textiles? And then

Thesedays,ByBorre’sseasonal collections are gone, replaced by a digital design tool that allowscreatorsacross industries direct access to the textilesthemselves.Akkersdijk’strademarktechniques remainintactbut are now available to everyone, from designers at legendary surf brand RipCurlandDutchsneaker company Neutra (both recent clients) to curious Hue readers.

“We are really making the medium of knitting and textile-making accessible to the world,” he says.

Akkersdijk’s goal is not only to reimagine responsible textile production for ByBorre clients, but also to spark an industry-wide conversation about sustainability that inspires other companies to follow suit.

Thedesigntool’ssoftwareguidescreators through ByBorre’s curated yarn library (including a durable polyester made in Italy from upcycled plastic bottles) and helps them tailor the textile to a product’s end use,

BY LIZ LEYDEN

whether as cycling gear for Rapha or interior fabrics for Social Hub hotels. And, in a repudiation of the often murky origins of fabric, each design comes with a “passport” that tracks the route of its raw materials through the supply chain and assesses the environmental impact of production.

Designing digitally lets creators experiment on-screen to achieve their exact vision—“What you see is what you get,” Akkersdijk says— and eliminates the need for excess sampling. To further reduce waste, ByBorre accepts production orders for as little as 50 meters.

“I think every bit of fiber or raw material that you create just to throw away is too valuable,” Akkersdijk says, adding, “Overproduction is a crime. That sounds radical, but think of where we are heading, of how valuable resources are becoming.”

Akkersdijk’s quest to create the textile production method of the future is gaining traction; the company has hosted recent workshops to demonstrate the design tool and discuss its transparent supply chain not only for fashion brands, but also for architecture firms and for automakers like BMW and Rivian.

“The new system needs to be more accurate, more responsible, more efficient in all the steps so we only produce what we use,” he says. “For me, the future is building that new system.” ■

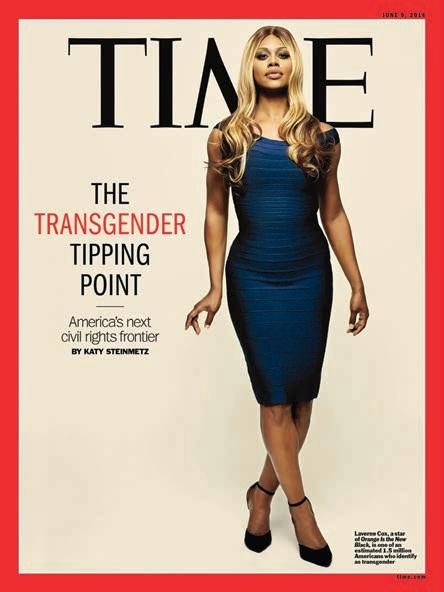

LWith

her dual passions as an actress and activist, Laverne Cox, Fashion Merchandising Management, fights for transgender visibility and empowerment

ike millions of other viewers worldwide, I first encountered Laverne Cox in her unforgettable portrayal of Sophia Burset in the Netflix prison drama Orange Is the New Black , in 2013. Cox’s raw,

nuanced performance commanded the small screen and rocketed her to stardom.

She became the first openly transgender actress to be nominated for a Primetime acting Emmy.

The FIT alum is remarkable not just as an actress but also in how effectively she uses her platform to fight for human rights. On social media and in TV interviews, she advocates for protections for LGBTQ+ people, especially for trans women of color, who are disproportionately discriminated against in housing, health care, employment, and education—and who are more likely to be murdered than any other group. For this work, she has been honored by the Transgender Law Center, the Forum for Equality, The New School, and Harvard.

This spring, Amazon Prime Video is debuting her comedy Clean Slate, which she is executive producing alongside the late Norman Lear’s Act III Productions. Lear was known for creating All in the Family and The Jeffersons, classic ’70s sitcoms that incorporated contemporary social issues.

Cox plays Desiree, the estranged child of a car wash owner, played by comedian George Wallace. After 23 years away, she returns home as a proud trans woman. The show— and all of Cox’s work—is a far cry from past depictions of trans people as sex workers,

serial killers, or punchlines. “It really is a wholesome family show,” she says.

Cox recently spoke with me from her fashion archive room, a studio apartment she rented across the hall from her New York City residence, where she stores her impressive collection of mostly Thierry Mugler, whom she reveres as an artist and a master of structure and tailoring.

As soon as our conversation began, I felt at ease in her calm and centered presence. We talked about her acting and activism, her love of fashion, and her time as a student at FIT. I could have listened to her for hours.

Hue: What excites you about Clean Slate?

Cox: The show is like a big warm hug. It’s about a father’s unconditional love for his daughter. Desiree is from Mobile, Alabama, as am I. She went to New York, found herself, transitioned, and is now back to reunite with her dad and work out some of her issues around picking unavailable men. She’s a therapy girl like me. The opening scene of the pilot is a session on FaceTime with my character’s therapist.

I’ve produced a number of things, but this is the first time I’ve produced anything that’s scripted that I get to act in. It’s been a dream of mine for 15, maybe 20 years. We started working on it eight years ago.

BY JONATHAN VATNER

Eight years?

We pitched it to everybody: HBO, Netflix, Showtime. After a couple of years, I was like, “Oh, they’re not buying trans shows right now.” It was an industry thing. At that moment, they were using trans people in supporting roles or in non-trans roles. I had given up on it. But we finally landed at Amazon Prime with the great Norman Lear on board as our co-executive producer. I grew up with Norman Lear shows. They were my life. So it was really magical to get to work with him and the legendary George Wallace.

Why do you think it’s been so hard to sell trans shows?

We’ve always been a hard sell. There was a period of several years where there was way more representation in scripted TV and film and more presence of trans people on social media. And then something shifted. I think there’s been a backlash against trans visibility.

I’m not a network executive, so I can’t say what’s in their minds. Ultimately, corporations are corporations, and it’s about money for them. But I remember one pitch for Clean Slate: The executives were literally moved to tears. And they said no. The fact that it’s airing feels like a miracle.

I think we really need humanized representation of trans people right now. In the political landscape over the past few years, the strategy for the right wing has been to dehumanize trans people to such a degree that you can take away our rights. It’s been devastating for me to witness.

As we’re talking, I’ve been thinking that it must be impossible for an actress who’s trans to just be an artist. Like, you kind of have to be an activist as well, right?

There are trans actors who don’t lean into activism at all. I’ve known Jamie Clayton for 20 years—we were in acting class together— and she was very specific when she had her breakthrough on Sense8 that she was an actress first and didn’t want to be political. And that’s beautiful. Not everybody is an activist. Not everybody should be.

When did you know you would be an activist?

When I was 6 years old, my mother gave me and my brother a Black history book that had little photos and brief biographies of famous

African Americans who have changed history. Obviously Martin Luther King is in there and W.E.B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington, but also artists like Katherine Dunham, Marian Anderson, and Leontyne Price, who was my favorite.

In the photo, she was wearing this turban and she had high cheekbones and beautiful full lips like mine. I would lie in bed and stare at this photo of her. And I remember imagining as a 6-year-old, wouldn’t it be amazing if I could do something with my life that would make things better for people who came after me?

I was in my 40s when I booked Orange Is the New Black. Well before that, I would go up

to Albany for Equality and Justice Day every year and talk to state legislators to get the Gender Expression Non-Discrimination Act passed. It took 17 years. I was writing pieces for the Huffington Post about trans people and gender. I hosted the Transgender Legal Defense and Education Fund benefit. And I did several media appearances to try to educate folks on trans stuff.

When Orange happened, I was like, this could be over in a second. And so I had a sense of urgency when I got a platform, an international platform, to talk about the serious issues facing the trans community. I soon realized I needed to balance that with taking care of my

“I remember imagining as a 6-year-old, wouldn’t it be amazing if I could do something with my life that would make things better for people who came after me?”

mental health. A lot of my work now is trying to stay abreast of new policies while holding space for my own trauma as a trans person seeing rights being taken away or violence committed against us.

What brought you to FIT?

I graduated from Marymount Manhattan College in 1996 with a dance degree. I acted a lot in college. In 1998, I started my medical transition. There weren’t trans people who were actors at that time. I loved fashion and knew trans women working in the fashion business, so I went to FIT to study

merchandising. I only stayed three semesters, but I learned a lot. So many things about fabric and fashion history and merchandising.

“Healthcare for everyone, a living wage for everyone, everyone being accepted for who they are. A world where people are free— and we don’t destroy the planet in the process.”

I think I read as trans to some people, and I didn’t to others. It never was an issue. But one day at FIT, the coach of the men’s basketball team saw me and was like, “Oh my God, you’re so tall. Have you thought about joining the basketball team?” And I’m like, “Sweetie, I’m not the one.” I think about that a lot. FIT was awesome. But I realized after three semesters that I didn’t really want to be working in fashion merchan-

COX

dising. I left FIT and really started taking acting seriously. I started believing that it would be possible for me to have a mainstream acting career.

Tell me about your fashion collection. I collect Mugler mainly, but I also have some Comme des Garçons, some Dior by Galliano, some [Alexander] McQueen, and a Pierre Cardin dress from 1969. I mean, the history! But I also enjoy my collection as art. I love the amazing tailoring and structure. That’s what really gets me excited. I’ve spent too much money on these pieces—like, way too much money. I’ve definitely had to set some limits. It’s excessive and kind of insane, this collecting. But it brings me so much joy. ■

large indoor tree shares the office President Joyce F. Brown has occupied for nearly 27 years. The Princess, as she affectionately calls it, dwarfs its pot, spreading out as it grows in every direction.

It’s a houseplant with a big personality.

“When I go, she goes,” Dr. Brown says wistfully at the start of her final Hue interview before she steps down from her position at the end of the 2024–25 academic year. She is not certain the Princess will tolerate the move. “Or we’ll see. We’re in talks.”

Dr. Brown seems particularly introspective as she contemplates what it will mean to depart this institution after so many years. She has had the longest tenure of any FIT president, much less the college’s first woman and African American at the helm.

She has overseen an extraordinary evolution. Since her arrival in 1998, FIT has debuted 33 more degree and credit certificate programs and added dozens of academic minors. She created the Center for Innovation at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, where faculty can pursue research, and the on-campus DTech Lab, which helps industry partners tackle innovative projects while providing real-world learning opportunities for students.

In 2020, she established the Social Justice Center at FIT with the goal of increasing BIPOC representation in the creative industries. And this year, a magnificent new academic building opens its doors on 28th Street, with 26 smart, energy-efficient classrooms, a state-of-the-art knitting lab, and a soaring atrium. All of this has come thanks to

her foresight, persistence, and commitment to consesus-building.

In this interview, Dr. Brown discusses her presidency, legacy, and hope for the future.

Hue: What accomplishment are you most proud of?

President Brown: As an institution, as a community, we’re having a different conversation than we were 27 years ago. We’re talking about being cutting edge and interdisciplinary. There’s a different dynamism that runs through the conversation and through the community that has changed the focus at FIT. I think it’s driven by a lot of new faculty with different experiences, a different mindset, and different intellectual curiosity, with access to resources like DTech and release time to do research. I like to think I can take some credit for these changes. And of course I’m proud of the building, because somehow it became my life’s work.

When did you first realize you wanted to create the new building?

When I was hired, the student dining room was on the sixth floor of a building with one elevator. It was a disaster. We put in the dining room on the ground level with a Starbucks and expanded the student dining experience, but at some point, it became clear to me that

BY JONATHAN VATNER

we really did need a new building. The National Endowment for the Arts held a competition, and SHoP Architects won with their design— which is really gorgeous, I have to say.

And then we began the fight. When we started, we needed $148 million. By the time we finished, we needed $189 million. I mean, what’s a few million dollars between friends, right? Unexpectedly, we were able to get half of the money from the state. The Bloomberg administration decided we had to raise the remaining funds for ourselves. We ultimately got the balance from the de Blasio administration. It took years. I was determined to do it.

And I am very proud of the new building.

Our students deserve an environment that encourages innovation and experimentation and a commitment to do their best. I think it’s going to make a tremendous difference.

The Social Justice Center at FIT is reaching its fifth anniversary. What progress have you seen, and what challenges still need to be addressed?

We’ve been able to create an opportunity for some creative young people, who might not have otherwise been exposed to the industry, to come here and study. What I have not been able to achieve, which was the other important prong, was to have the industries themselves create pathways for real progress, to diversify their ranks, to create the opportunity in their executive suite that ultimately was going to reflect the diversity of their consumer base.

And now there’s a pejorative overlay to the dialogue about DEI. So while I’m very appreciative of the companies that are working with us to create those pathways, I can’t say I’ve seen the changes I would like to.

You encourage a synthesis between technical skills and the liberal arts. Do you continue to see that balancedapproachbenefitingstudents as they go into the industry?

I have always believed in the value of the liberal arts. Early on, we held a symposium with the industry titans from Ralph Lauren and from Bergdorf Goodman and Macy’s. They talked about what they were looking for in hiring. One of them asked applicants, “What are you reading now?” To me, that was very significant. The people who are employing these young folks are asking them, “How do you make decisions? How do you problem-solve? What are you thinking about?”

tage. We have to not be nervous about it. I don’t think the students are.

What advice would you give to your successor?

It gave me a kind of permission to emphasize the liberal arts at FIT. Now we have minors in the liberal arts, and the students love them. And the whole notion of the Writing and Speaking Studio is very exciting. It makes people think in a different way when they need to articulate their point of view.

What do you see as the next frontier for higher education?

Everything changed after 2020. The isolation, the readjustment of habits, how people dress, how people get information and are entertained. Every aspect of life was affected. So I think the next frontier for education really has to recognize this difference in the landscape.

How do you think AI is going to a ect the educational experience in the future?

I’m old enough to remember when everyone was scared of the internet. It was going to take over everyone’s jobs. It was going to be this invading force. And now we all walk around with these little appendages that connect us to the internet, and we think we can’t live without it.

In a similar way, people are very nervous about AI. But it is a tool. It’s not a force in and of itself. We need to figure out how to put our arms around this thing and use it to our advan-

The important thing is to be open and listen. You have to dedicate months to really listening and understanding what’s important to the community.

I always say that any idea that’s just my idea is dead in the water. You have to be willing to act on what the community wants, even if you end up honing it a bit. We started out in strategic planning with a lot of ideas that people didn’t agree with. So we ended up spending a whole extra year on drilling down and understanding what our constituent groups wanted the strategic plan to look like. It was time well spent.

We revisit the plan every five years and ask ourselves, Do we change our direction? Do we expand our initiatives? Do we say, “OK, that seemed like a good idea then, but this is a better direction?” Again, you need to be flexible and open while having a sense of how to position the institution so that our students can be the next leaders of these industries.

What’s next for you?

I really feel like I could stay and continue doing this. But completing the new building felt like the end of a chapter. And the college will benefit from new leadership, someone with new visions and different capabilities.

I think my skill set is working with people and figuring out how to collaborate and create a complex environment that is productive on a lot of different levels. So we’ll see. I don’t intend to ride off into the sunset. ■

The portraits and related symbols in this issue by illustrator Carlos Aponte, MFA ’21, BFA ’17, are perfect representations of his style: Elegant. Bold. Graphic. But they’re far from his only style. This particular drawing technique, Aponte says, owes something to the original poster for the Broadway show Evita (1979), which made an impression when the native-born Puerto Rican first came to New York City. He has drawn for The New Yorker, The Wall Street Journal, and Google, among others, and he teaches Illustration at the college. Aponte’s most authentic artist self can perhaps be found in the children’s books he’s illustrated, which feature a luscious color palette, sinuous line work, and more than a whi of his lefty political sensibility. “I tend to speak to things that need to be corrected,” he says. “My work is always in your face.” Across the Bay (Penguin, 2019), won the New York Public Library’s Pura Belpré Award, given to a Latino writer and illustrator whose work best portrays the Latino cultural experience. Preciosa (Penguin), which follows a Boricua boy after a devastating hurricane, will be published in May. Whether Aponte is sketching something in a notebook or rendering a highly polished image for a corporation, every subject is enshrined in his radiant creativity. “I tell my students that nothing is boring,” he says. “Every object you see has a character. Even a cup full of pens.” Alex Joseph

and Marketing for the Fashion Industries ’25, created this glimpse into FIT student style

THE LOOKS ON THE FOLLOWING SPREAD were styled and photographed by student Drew Cwiek. He cast all the models—“It’s very friendship-based,” he says of his selection process—dressed them using a mix of their clothes and pieces he thrifted or sewed, photographed them with his iPhone 12 Pro Max and a Canon EOS M50, and laid out the spread for Hue

Taken together, the photos are a peek at the state of fashion at FIT: ’90s-throwback, preppy, eclectic, and layered.

Cwiek also designs the relaxed fit, vintage-inspired, gender-fluid clothing label byDrewCwiek and produces it overseas. Cwiek says the designs are a portal into his state of mind, which recently has been a nostalgic imagining of summer camp.

Together with a friend who goes to Borough of Manhattan Community College and two more in Russia and Germany, Cwiek co-founded a production and design company called WFTV (no, it’s not a TV station—it stands for Work for the Void). WFTV is a collaborative of friends who provide an array of services—including apparel development, website building, e-commerce management, and more—for emerging fashion brands. The company also showcases their styling and design work in a self-published journal, sold in bookstores and magazine shops in New York, South Carolina, Western Europe, and Japan.

In the spirit of community, WFTV teaches the services they offer their clients. Cwiek says, “The company ethos is helping other people out and saying, ‘Oh yeah, you can do this, too.’” —Jonathan Vatner

“One of my favorite pieces is my denim trench coat, which I found thrifting in California.”

AVA FROST FASHION BUSINESS MANAGEMENT ’25

“One of my favorite pieces that Drew styled from my closet is the blazer because it shows how my style has matured.”

CORINNE COLLADO ADVERTISING AND MARKETING COMMUNICATIONS ’25

“My style showcases themes of nostalgia, playfulness, and garment manipulation.”

DREW CWIEK*

INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND MARKETING ’25

*Cwiek designed the pants he is wearing and Mendoza’s jacket.

“I enjoy experimenting with different pieces and vibes, letting my mood guide my fashion choices each day.”

TYLER STRAKER

ADVERTISING AND MARKETING COMMUNICATIONS ’28

“I think of myself as a representation of many generations of clothes that end up being a baggy, bright personal style.”

VICTOR MENDOZA FINE ARTS ’28

“This outfit embodies a rugged, workwear-inspired aesthetic with elements of utilitarian fashion.”

LORENZO McCOY FASHION DESIGN ’25

“My style is punk-inspired with a whimsical edge.”

HANNAH BAUTISTA FASHION BUSINESS MANAGEMENT ’25

“How something is produced and who produced it are more important to me than the look. My mom knit the fingerless gloves I am wearing out of undyed wool and silk yarn.”

ELIAS DOLTON-THORNTON FASHION BUSINESS MANAGEMENT ’25

“Friends or strangers comment how I look like I am right out of a ’90s movie or 2000s Abercrombie catalog.”

LUCAS NEALON INTERIOR DESIGN ’25

“My vintage rawhide leather biker jacket was made in 1987 by a German leather shop. I have had this pair of APC jeans for three years and have been making sure that they keep fading properly.”

ETHAN CHARALAMBIDES PRODUCTION MANAGEMENT ’25

“I’m especially drawn to vintage pieces I’ve found in my mom’s, nonna’s, and aunts’ closets. It’s all about layering personal stories.”

BELLA GARCIA ADVERTISING AND MARKETING COMMUNICATIONS ’25

Find more looks— and behind-the-scenes shots— at hue.fitnyc.edu.

Covry eyewear’s Southern California boutique elevates the shopping experience

BY WINNIE McCROY

Reminiscent of a Japanese garden, the interior of Covry eyewear in Costa Mesa, California, is lush with greenery and features rough-hewn stone counters, warm wood, and organic curves. Co-founder Florence Shin wanted Covry’s first brick-and-mortar location to evoke the sheltered cove that inspired their moniker.

“People say it feels like a spa,” explains Shin, International Trade and Marketing ’13. Covry has found a strong market in this SoCal town since opening in 2023—cultivated via empowering in-store events, including yoga and sound baths, panels with local merchants, and morning walks in neighboring Newport Bay Nature Preserve, where “our community can come and grow together.”

After college, Shin and high school pal Athina Wang reconnected in NYC’s Garment District. Both had grown up wearing glasses but could never find a pair that fit comfortably. Working in fashion, they saw everything from belts to rings in a wide range of sizes. Why not eyewear?

“Our faces are so unique and beautiful, but there was one standard fit for glasses. We thought there was something we could do about that,” Shin says.

Both women have low nose bridges and high cheekbones, causing most eyewear to slide down and rest on their cheeks. They identified three areas to improve upon. First, they added longer nose pads, so frames would sit higher on their nose. Next, they straightened the frames so they wouldn’t dig into their cheeks. Finally, they narrowed the bridge to fit snugly. They dubbed the result Elevated Fit. It was ideal for not only Asian faces, but also for anyone with a smaller nose, high cheeks, and long lashes.

Eyewear is a highly technical product, involving many steps to create a single pair. Working with a team of 40 skilled artisans, Covry makes frames precisely molded, cut, polished, lasered, and assembled in limited-run batches.

“There’s no one-size-fits-all for faces, but with every new style, we do several iterations to test out the fit,” says Shin.

They began by selling sunglasses online. Now Covry features 60 styles of sunglasses and eyeglasses at accessible price points, starting at $105. The website offers an online fit quiz to narrow down recommendations, plus a virtual try-on tool. And because fit is crucial, Covry mails five frames for each order, which helps customers feel confident in their purchase.

“The real goal is to offer a more humanized interaction,” says Shin. To that end, the duo created The Blue Room, an area of the store where shoppers can get complimentary style consultations. That proved to be eye-opening for both customers and Covry’s founders.

“A lot of people didn’t even realize their frames weren’t fitting because they’re used to just pushing their glasses back up their noses every few minutes,” Shin says. “Getting people to try on our glasses was that magical ‘aha’ moment of, ‘This is how glasses are supposed to fit.’ We get letters from people saying they’ve never had frames fit so well, that they finally feel seen through our eyeglasses.”

Q:

Your capstone project revisits a troubling exhibit at the St. Louis World’s Fair of 1904. What happened there, and what is your capstone about?

A:Exhibitions and exhibition designers shape the way we see the world. I grew up in the Philippines and worked for the tourist and creative industries on behalf of the government there. My capstone project, an exhibition that explores the deeply problematic Philippine exhibit at the 1904 World’s Fair, is a proposal for the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian. (This venue allows us to explore parallel experiences between Native Americans and Filipinos during American territorial expansion, adding a crucial historical perspective to both narratives.) At the fair, Filipino people were displayed to illustrate socalled “stages of civilization,” and portrayed as savages in contrast with Americans. The exhibit was used to justify U.S. colonial rule in the Philippines. The fair also marked the centennial of the Louisiana Purchase, which displaced Native Americans,

contributing to colonial narratives.

In my project, I aim to engage viewers not only with the darker aspects of this history but also with the beauty of Filipino culture. If your material is too di cult, people disengage, so I want to include a number of object-based interactions, particularly Filipino crafts. Human beings are naturally makers, so highlighting handmade works provides insight and reminds the audience of the makers’ humanity. Through lighting, music, and graphics, I seek to evoke a sense of wonder while encouraging reflection on the lasting impact of colonial exhibitions. The 1904 fair also signaled the beginning of Filipino migration to the U.S., and my capstone will highlight this important, though often overlooked, history. My goal is to create a space where visitors can meaningfully engage with these events while appreciating the cultural richness of the Filipino people.

Michael Ferraro, executive director of the DTech Lab and creative director of the Innovation Center at FIT

In the DTech Lab, teams of students, supervised by faculty, execute projects in branding, strategy, and design to assist companies facing a wide range of challenges. We explored artificial intelligence (AI) with IBM and Tommy Hilfiger, designed an upcycled line for Uniqlo, and redesigned Girl Scout uniforms.

This academic year, we worked with Faryl Robin, a large footwear brand that primarily does private-label production for Nordstrom, Target, and other big retailers. Now, they want to launch their own direct-toconsumer brand. They have made one or two other attempts but didn’t get the kind of traction they would like. The founder and CEO, Faryl Robin Gilston, Accessories Design ’89, Marketing: Fashion and Related Industries ’88, came to us to develop a complete brand identity from the ground up to help articulate her vision and make her line thrive in the marketplace. Gilston wanted to defy convention, redefine expectations, and ignite positive change—really strong value statements. Advertising and Digital Design (A&DD) students Caitlin Yackley and Mateo Gonzalez worked with Footwear and Accessories Design (F&AD) students Andrew Kaefer and Yosely Felix. Adjunct Instructors Diane DePaolis, A&DD, and Kira Goodey, F&AD, guided them.

Burberry plaid and the flower symbols associated with Louis Vuitton.

The students then presented their research into the competitive landscape to the Faryl Robin team, along with three possible directions for the brand and accompanying shoe designs for each, created by the F&AD students.

The winning brand identity is called FRTHR, a modular and sustainable shoe concept that redefines travel footwear. It fills a gap in the market for a non-sneaker shoe that simplifies packing. In addition, there are a limited number of sustainable footwear brands, even fewer that are suitable for professional situations.

The brand purpose helps women “put their best foot forward.” This is not just a glib expression; it drills down deep into Gilston’s values.

The F&AD students designed a perfect shoe for travel that could also be used for work, incorporating sustainable elements like detachable soles (to make the shoe more recyclable) and innovative materials like wovens and pleats (to provide greater comfort and flexibility at a lighter weight). They included a broad range of sizes and widths because there’s a great unmet need there. The A&DD students created brand guidelines and extensive applications of the logo, including secondary graphics and fun animations.

First, the A&DD students researched in FIT’s Gladys Marcus Library, which has extensive resources that gave the students insight into market trends and opportunities. Then they went into the field, to Neiman Marcus and Nordstrom and online at Zappos, and studied 1,400 footwear brands. They grouped the logos by type: wordmarks and letterforms, shapes, and symbols. They also looked at secondary graphics that are brand-defining, like

The work was absolutely astounding. When the students were presenting, the client was like, “Holy Christmas, this is amazing!”

—As told to Jonathan Vatner

By Colleen Hill, Fashion and Textile

All curators have favorite objects— those that spark admiration because of their spectacular appearance, fascinating provenance, or historical significance. A table painstakingly covered in feathers, by milliner-turnedphotographer Bill Cunningham, embodies all of these criteria.

The Museum at FIT acquired the table from the photographer Frederick Eberstadt. Early in my career, I received a call from Mr. Eberstadt, asking if MFIT would be interested in

a donation of his late wife’s clothing. Isabel Eberstadt, a journalist and author, was also a socialite known for her cuttingedge fashion sense. With impeccable pronunciation, Mr. Eberstadt enumerated clothing by designers such as André Courrèges, Madame Grès, and Yves Saint Laurent.

In 2007, MFIT enthusiastically received numerous pieces from Isabel’s wardrobe, many

from the 1960s—a particularly daring period in her sartorial history. A large, elaborately feathered Adolfo headpiece from circa 1962 highlights her audaciousness. “I guess I don’t mind being laughed at,” she admitted to The New York Times in 1964.

When picking up the clothing from Mr. Eberstadt’s home, my colleagues admired the Cunningham table—an 18thcentury style piece with cabriole legs onto which varying shades of pheasant feathers were glued, completely disguising its original surface. Several years later, Eberstadt offered it to MFIT, explaining that it had been a gift from Cunningham to his wife. Although the table was a departure from the museum’s fashion-focused mission, it was too captivating to refuse. Cunningham often used feathers creatively in his hat making, and this table is a unique extension of that practice. Its date of creation is unknown, but Cunningham was acquainted with the Eberstadts as early as 1963, when he described Isabel as “the most beautifully exotic woman in America” in Women’s Wear Daily.

by feathers. I hope that this table—with its connection to two remarkable tastemakers—

will pique visitors’ curiosity as much as it has my own.

Ten years after its acquisition, I prominently featured the table in Fashioning Wonder: A Cabinet of Curiosities. This MFIT exhibition, on view until April 20, offers a contemporary adaptation of cabinets of curiosities—proto-museums that centered on rare, beautiful, and extraordinary objects. Like Cunningham, early collectors were fascinated

Sebastien Courty, Textile/Surface Design ’15, portrays culture through fiber art

Formally exquisite and culturally specific, Sebastien Courty’s works sometimes double as forms of diplomacy. His most renowned commissions include artworks for the U.S. consulate in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, through the U.S. Department of State’s Art in Embassies program as well as a portrait series for UN Women, a United Nations entity dedicated to women’s empowerment. His conceptual weaving and

thread-based drawings have also been a part of Art Basel Miami Beach, Art Basel Paris, and Frieze Los Angeles.

Courty refers to the 9.5-by1.5-foot pieces in his Art in Embassies installation, titled Saudi Unity, as “Totems.” The 13 vertically wall-mounted panels were created using a mix of beads, aluminum and copper wire, silk, rhinestone chains, and other materials that reference the people, colors, textiles, and natural resources of the 13 regions of Saudi Arabia. Courty’s first exhibition of Totems took place in 2018 in the south of France during the annual Design Parade Hyères festival and included pieces representing Kenya, Peru, New Zealand, Tanzania, Ivory Coast, and China. For Courty, the Totems are an invitation

to learn about a country or city that may be unfamiliar. “The artwork becomes a physical DNA sequence of the country itself,” he says.

While in conversation with a collector about his Tanzania Totem, Courty realized the potential of his work to open up complex conversations about global trade, natural resources, and sustainability. The luxurious artwork—woven with tobacco leaves, tanzanite stones, and gold, which make up 98% of the country’s exports—belied the collector’s experience of the country’s widespread poverty.

“I explained that all the gold mines in the country are not owned by Tanzanians, so the wealth of the country does not stay in the country. She was fascinated by the conversation,” Courty says. “My intention

is to invite viewers to engage with the Totems, and through their own interpretation, learn about a place, get curious, and be inspired to travel and discover more about our world.” —Diana McClure

Kristen Keenan, Fashion Design ’04, creates paint and upholstery for specialedition Ford vehicles

Kristen Keenan loves what she calls the “Willy Wonka” aspects of her job: “The things going on behind the curtain that you would never imagine.” A colors and materials designer at Ford Motor Co., Keenan grins as she describes “ingress/egress,” a test simulating long-term wear on a vehicle’s upholstery. “A robot gets in and out over and over. It’s literally a robot butt.”

Keenan is part of a team that creates special editions and special trim models of Ford’s vehicles: new takes on familiar mainstays like the Mustang, Maverick, and Bronco. Her job is to give them eye-catching new looks, ranging from the paint and trim on a vehicle’s body to the fabric and stitching on its seats. “We design for a niche customer and we get to push the boundaries.”

The 2025 Ford Maverick Lobo is a low-slung pickup truck with enhanced performance for

Continued on next page

driving on streets. Some of the model’s biggest enthusiasts are involved in autocross, a sport in which drivers maneuver through a course marked by traffic cones. Keenan’s inspiration for The Maverick Lobo’s bold styling came from an unexpected place: an outdoor basketball court in NYC. Drawn to the court’s lime-green and electricblue colors, she snapped a picture for reference. Back in Dearborn, Michigan, Keenan, who has previous experience as a shoe materials designer at Nike, created splatterpaint-inspired upholstery and vividly contrasting green-and-blue stitching on the seats and steering wheel, for a street-style feel.

The 2025 Bronco Free Wheeling was “developed to appeal to younger customers,” according to Ford’s communications department, “who appreciate Bronco’s heritage,” but also want a fun, contemporary design. A special edition that retails for a few thousand dollars more than the base trim model (starting price

the Free Wheeling reimagines a popular sunset-inspired design theme that dates back to the ’70s. Its red, orange, and yellow gradient stripes stand out sharply against the SUV’s black paint.

The biggest challenge, Keenan says, was color-matching.

“The stripes in the ’70s were reflective, and we wanted to keep that effect for the modern version.” This meant incorporating tiny glass beads into the paint. Because the added ingredient affected the way the eye perceives the color, further adjustments were necessary. The upholstery for the seats required a lot of tweaking too. Keenan designed a black fabric with red, orange, and yellow threads interwoven to create an ombre effect. “It took well over a year to color match because it was difficult to keep the saturation of the colors once it was woven in. When you see all the black, your eyes just dull the color down. So that was a real labor of love, a technical and design labor of love.”—Nora Maynard

People might look at my work and say, ‘What’s interesting about a bunch of broken bits?’” says Jacob Coley, vice president and director of antiquities at Hindman Auctions in Chicago. “I see that as a challenge, not a hindrance.”

$32,395 vs. $29,795),

Coley puts together two major sales a year, primarily of antiquities—art from the ancient Near East, Rome, Greece, and Egypt—and some pre-Columbian and ethnographic materials (like tools that show how past civilizations lived). These precious fragments may underwhelm the layperson, but to Coley, they’re beautiful and fascinating.

valuating and substantiating provenance of each item. He relies on a network of scholars and curators cultivated during his time at FIT and in his previous roles at the famed London gallery Colnaghi, Sotheby’s, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art (in its Greek and Roman Art Department). Auction catalogs are not known for innovation, but Coley’s experience in the museum and gallery worlds inspires him. His catalog for Hindman’s Cabinet of Curiosities sale in 2022 used the objects to tell a sweeping story. “I put together a timeline from the creation of our universe to man’s exploration of it—using antiquities and ethnographic and natural history— beginning with a meteorite from the solar system’s birth and ending with a manual from the lunar lander that put man on the moon,” he says.

Hindman is an upper-middlemarket auction house, with 2024 sales of $80 million to thousands of collectors around the world, but Coley says it operates as if it were a high-end blue chip house. Therefore, he and his team are fastidious in

In 2023, Coley got to work on the career-defining sale of the Ernest Brummer collection. Brummer was a turn-of-the20th-century art dealer who amassed one of the largest collections of medieval art and antiquities in America. In a full-circle moment from that sale, The Met, Coley’s former employer, purchased a bronze Greek cauldron that now sits on display in its Greek and Roman galleries. —Scarlett Harris

4KINSHIP blends sustainable fashion and Indigenous artistry.

Oded Oslander, Direct and Interactive Marketing ’02, Fashion Merchandising Management ’00, procures sustainable materials for Patagonia

When Oded Oslander started as raw materials manager at Patagonia in April 2022, global shortages and slowdowns brought about by the pandemic were still causing massive headaches. The elastic waistbands needed for one particular pant were not available, and any delays in production threatened to cut into the bottom line. Oslander, who had worked in sourcing for Jones New York, Nine West, and Anne Klein, asked the supplier to recommend a similar material. But his supervisor said no to the substitution. Patagonia only buys fabrics that meet the company’s rigorous social, environmental, and quality standards. Better to delay the product than to sacrifice these important values.

“At that moment, it clicked for me,” Oslander says. “I understood there was more than the bottom line.”

A separate team at Patagonia works with factories and mills to develop innovative sustainable materials like NetPlus, a plastic recycled from old fishing nets that might otherwise entangle marine life, and Yulex, a natural rubber substitute for petroleum-

based neoprene. Oslander’s team of five handles the logistics of procuring those materials in the correct quantities at the right time. He works with each mill to reserve the material and agree on a price, manages the shipment to the factory, and ensures that all deadlines are met. A few times a year, he visits suppliers, mostly in Asia, to handle more complex discussions.

“We have a long-lasting relationship with our suppliers,” he says. “They understand our goals and help us to meet them.”

Jonathan Vatner

Amy Denet Deal, Fashion Design, amplifies the work of Indigenous artisans

Growing up in Indiana, Amy Denet Deal designed her own clothes but never saw fashion as a career. “When I got into FIT, it felt like winning the lottery,” she recalls. Her acceptance set her on a journey from New York City to the corporate fashion world and, eventually, back to Navajo Nation, where she now channels her creative talents into empowering others.

Denet Deal’s early career was defined by innovation. Working as a senior designer and design director with brands like Puma International and Reebok in the ’80s and ’90s, she explored

advances in textile science. Her experiences in Europe sharpened her skills, preparing her to design not only products but also meaningful solutions.

In 2019, she returned to New Mexico—and to her roots. “Moving back meant decolonizing my mindset and embracing Indigenous values in life and business,” she explains. This shift became the foundation for 4KINSHIP, her sustainable brand that blends cultural heritage with contemporary fashion. Through beautifully crafted products, she celebrates the ingenuity and resilience of Indigenous artisans.

During the pandemic, Denet Deal raised $1 million for Navajo Nation, providing vital supplies like PPE. “It was about using my platform to support my tribe,” she says. As she explained to The Cut, she successfully raised funds to build a skatepark, with backing from celebrities like Tony Hawk and Jewel. Last summer, she provided 5,000 skateboards

to local Diné children.