CATRIONA WRIGHT // interview

ANA RODRIGUEZ MACHADO & BLESSING O. NWODO // poetry

H FELIX CHAU BRADLEY & K.R. BYGGDIN // fiction

CARLA HARRIS & ADELLE PURDHAM // creative nonfiction

BRIGITTE ARCHAMBAULT // comic

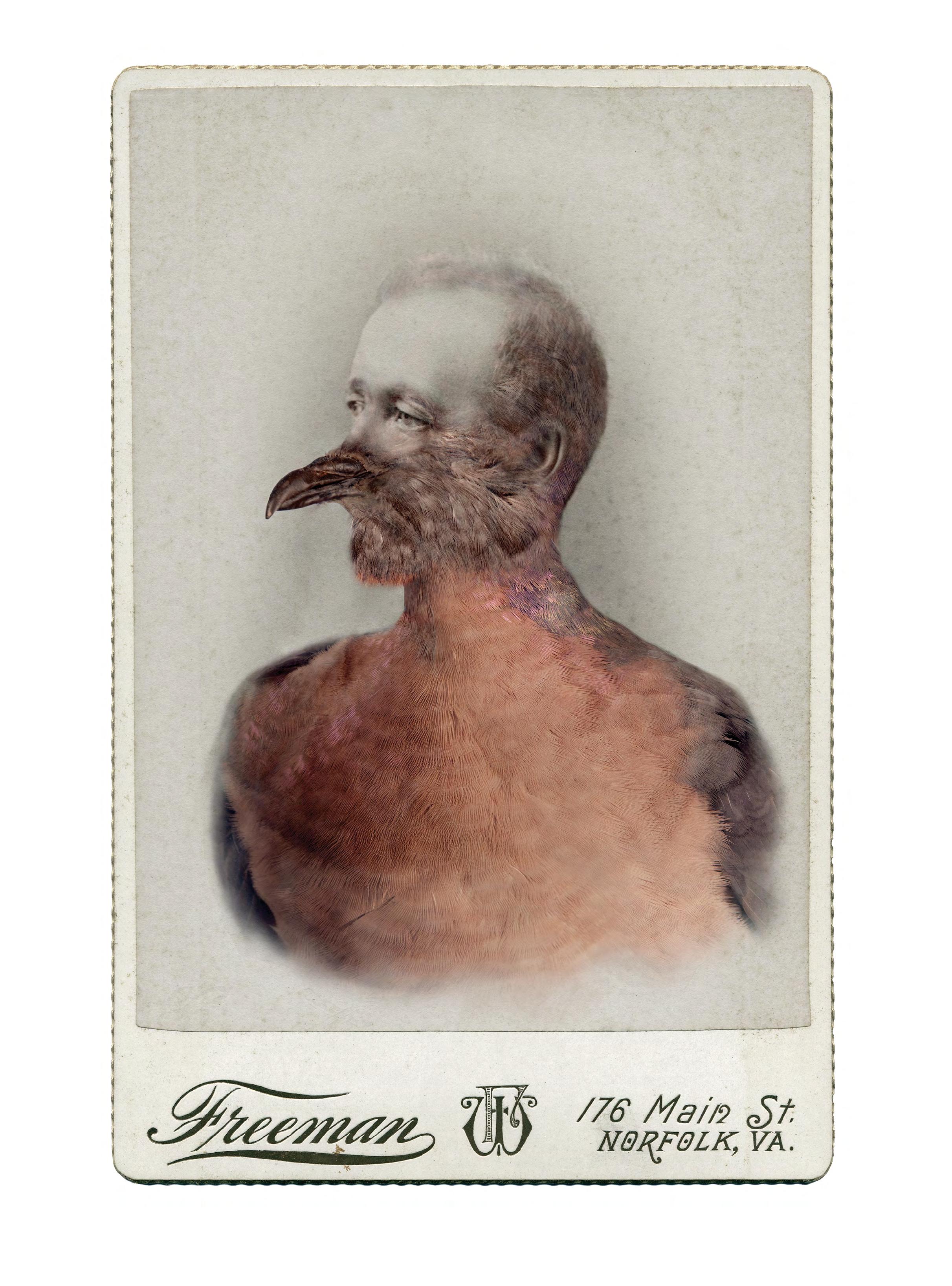

SARA ANGELUCCI // art

VOLUME 11 ISSUE 1 spring + summer 2023 $9.95

PROFESSIONAL WRITING AND COMMUNICATIONS

POSTGRADUATE CERTIFICATE

Featuring a third semester, industry-connected internship

CONTENTS

FROM THE EDITORS 3

// FICTION

SUE MURTAGH 4 Rescuing Spiderman

H FELIX CHAU BRADLEY 12 Second Appointment

MORGAN DICK 23 Autopilot Malfunction

K.R. BYGGDIN 33 Good Night, Reverend MICHELLE WINTERS 41 Happy Song

ERIC RAUSCH 51 Not Built to Last

// POETRY

ANA RODRIGUEZ MACHADO 9 [Three Poems]

BLESSING O. NWODO 20 [Three Poems]

MATTHEW ROONEY 32 [Two Poems]

SNEHA SUBRAMANIAN KANTA 43 Doetinchem

// ESSAYS

ALISON COLWELL 18 Fairy Tale Fathers

CARLA HARRIS 28 A Slowest Growing

ADELLE PURDHAM 44 Navel-Gazing, a Revolution & a Love Story: the Importance of the Self and Stories of the Marginalized

// COMICS

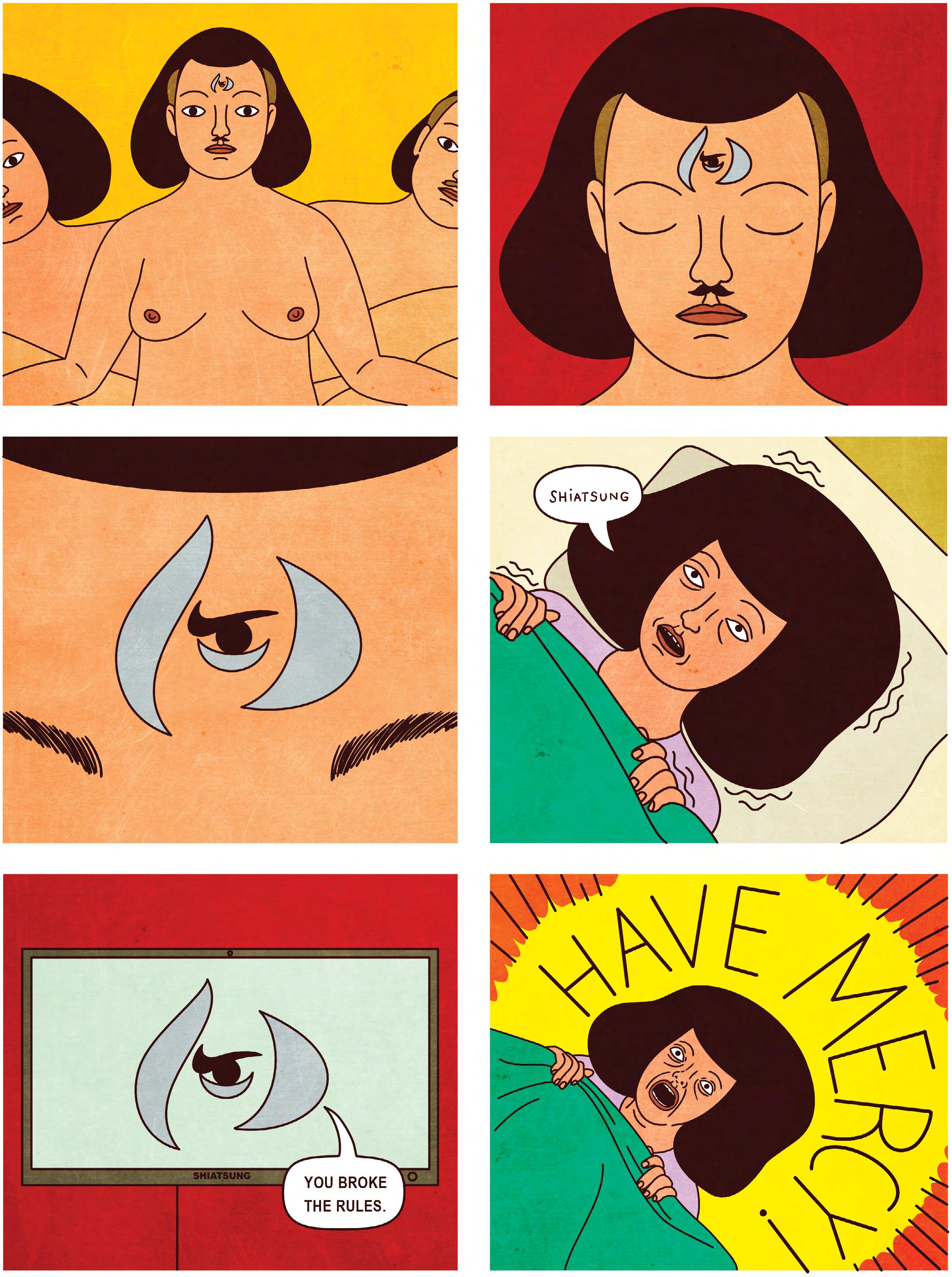

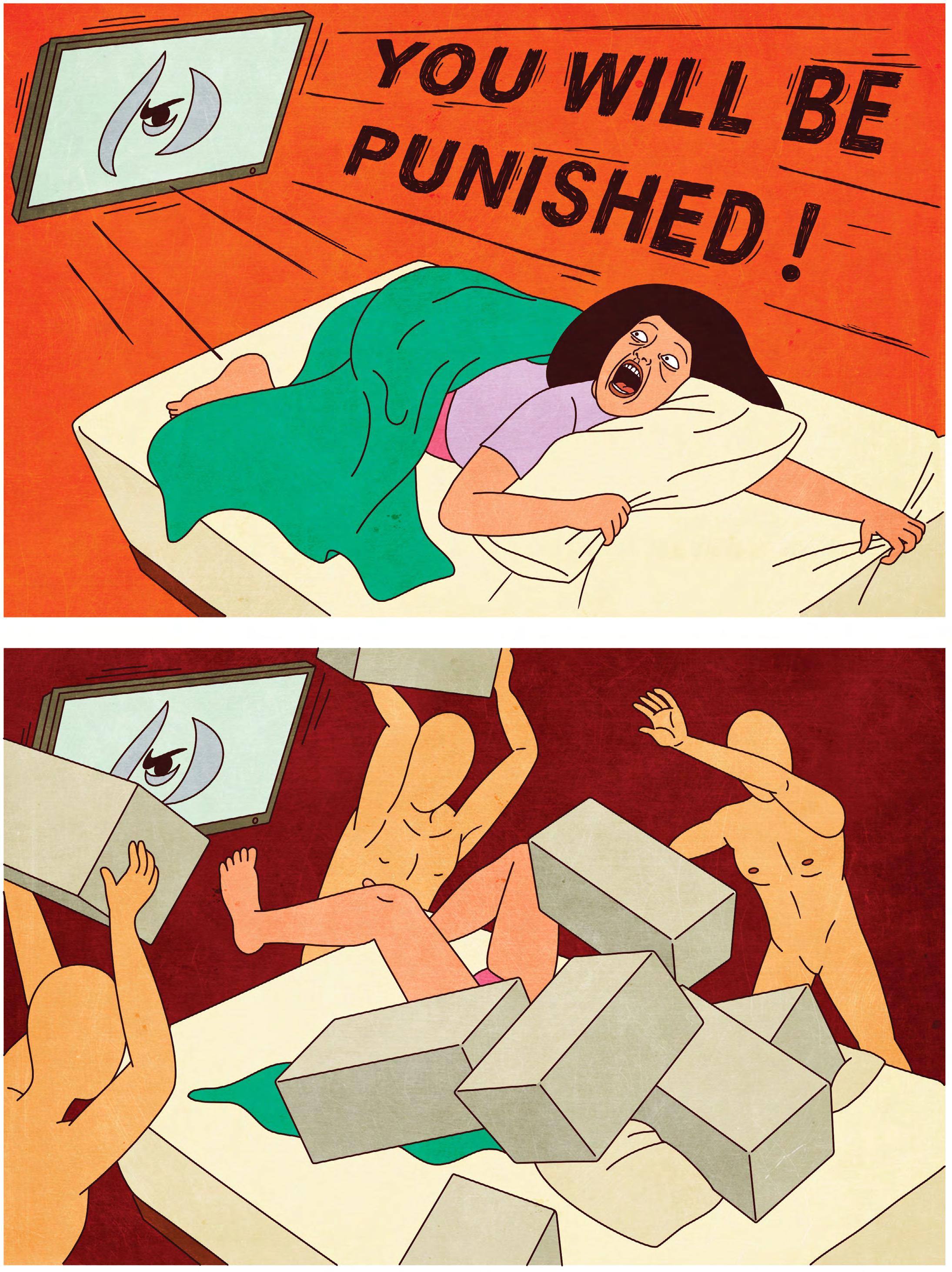

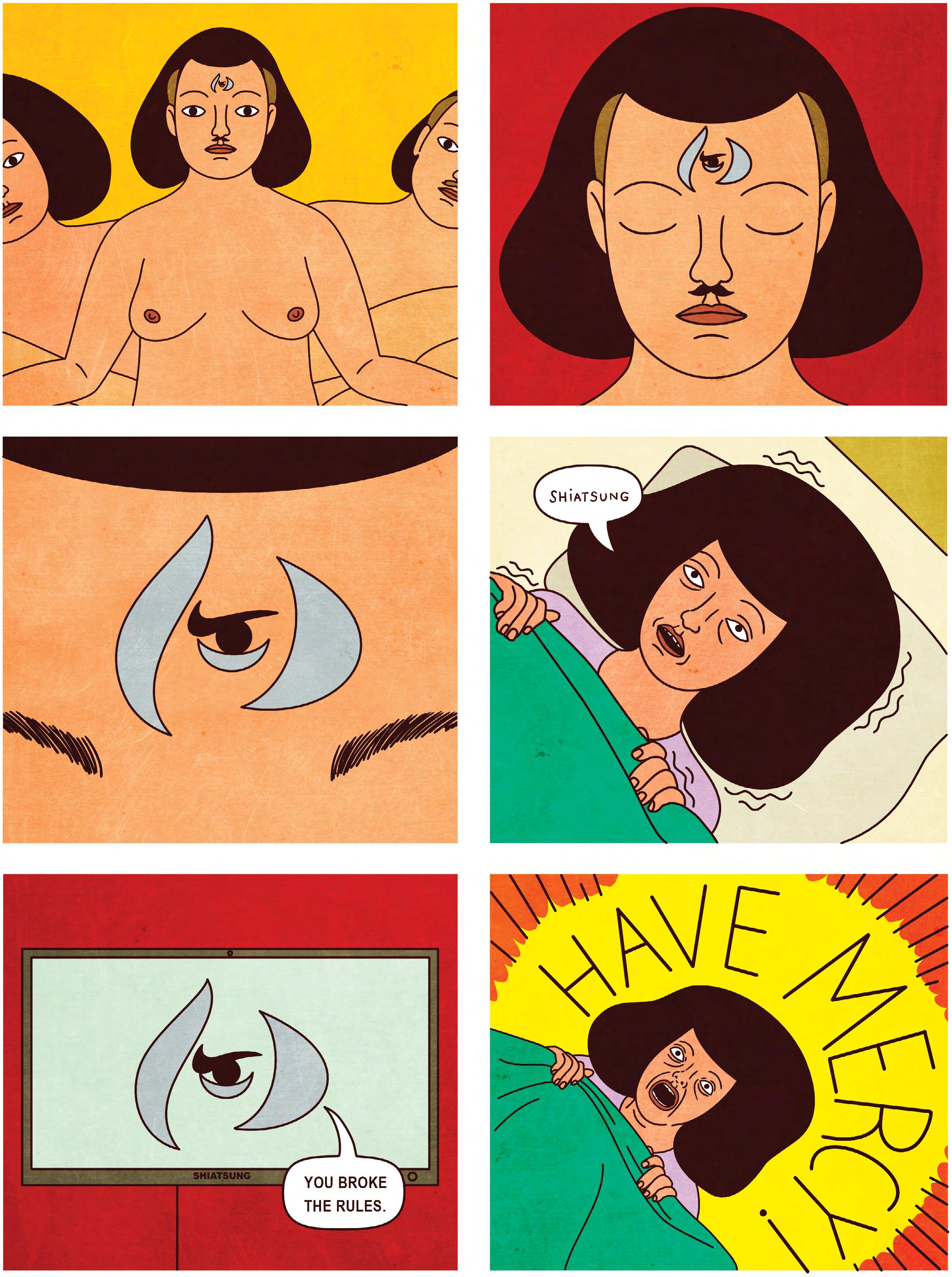

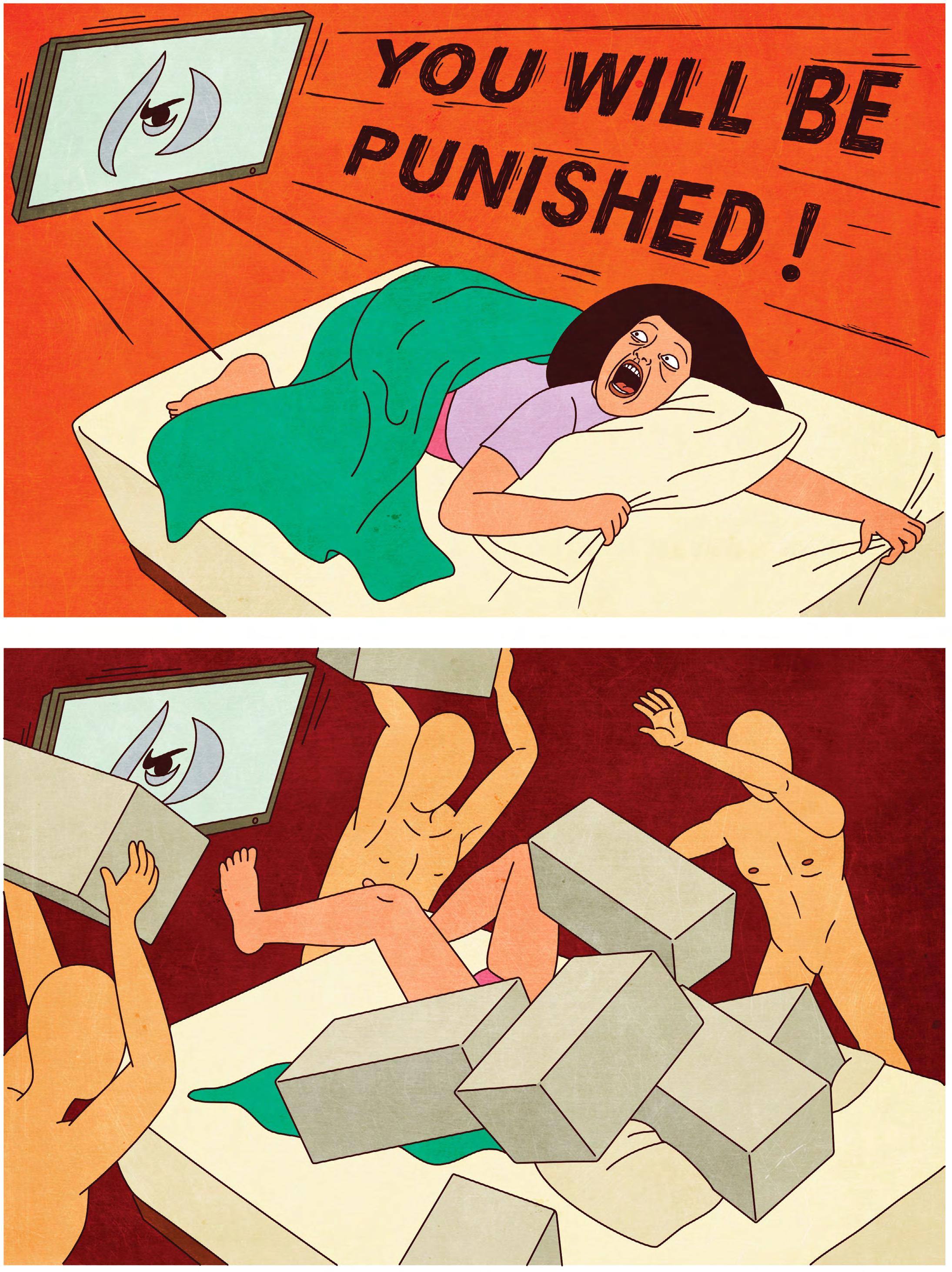

BRIGITTE ARCHAMBAULT 36 Excerpt from The Shiatsung Project

INTERVIEWS // REVIEWS

CATRIONA WRIGHT 56 [Interview]

REVIEWS 60 SON OF ELSEWHERE

NOMENCLATURE

IN THE BOWL OF MY EYE

FINGER TO FINGER

CONTRIBUTORS 65

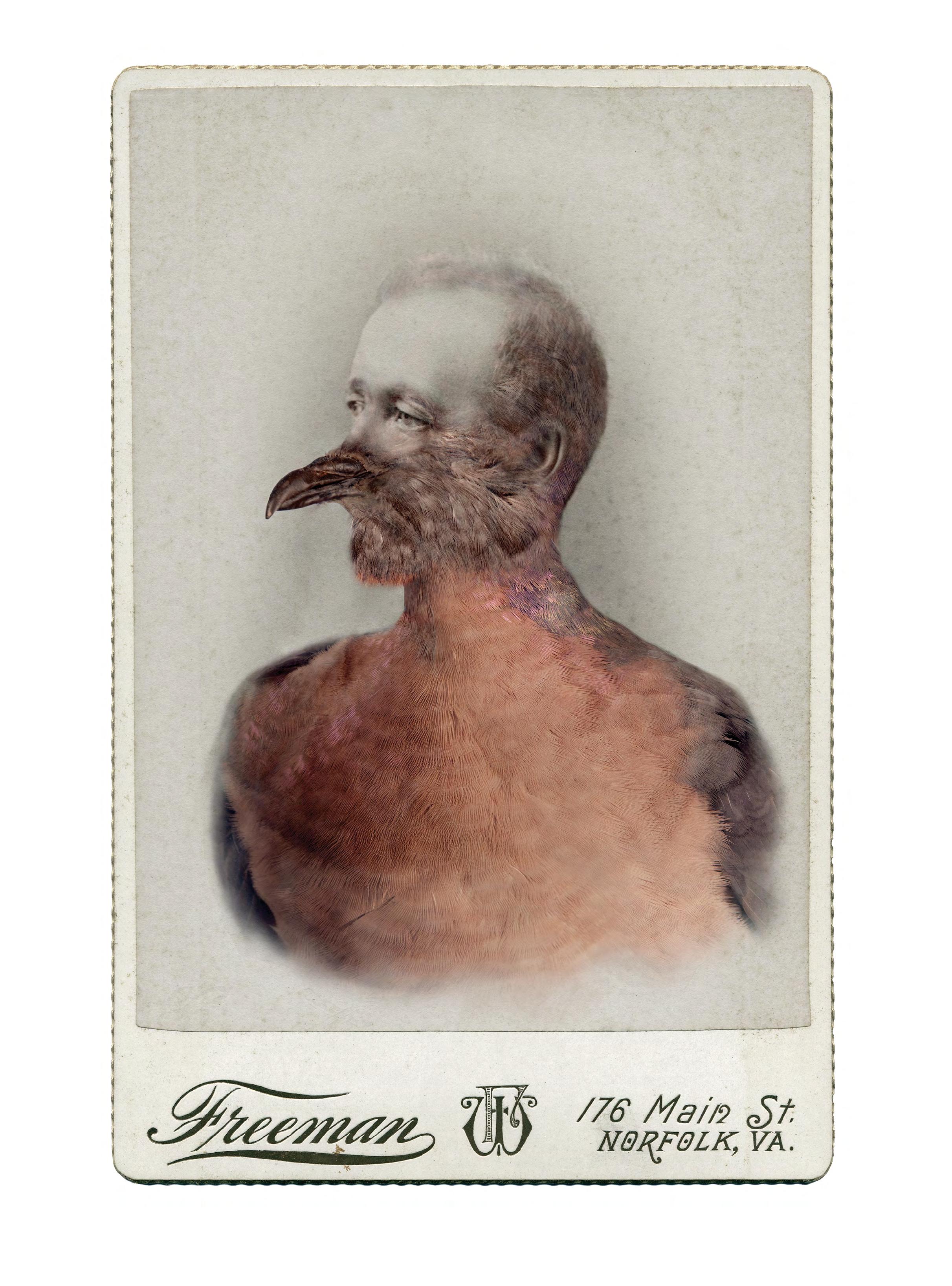

SARA ANGELUCCI 68 [Featured Artist]

VOLUME 11 ISSUE 1 spring + summer 2023

MASTHEAD

PUBLISHER

Patrice Esson

EDITORS

Eufemia Fantetti

D.D. Miller

FICTION EDITORS

Sarah Feldbloom

Kelly Harness

Matthew Harris

Alyson Renaldo

CREATIVE NONFICTION EDITOR

Leanne Milech

POETRY EDITOR

Meaghan Strimas

REVIEWS EDITOR

Angelo Muredda

ART/ILLUSTRATIONS EDITOR

Cole Swanson

COMICS EDITOR

Christian Leveille

COPY EDITORS

Tanya d’Anger

Andrew Drager

Claire Majors

Andy Scott

Suzanne Zelazo

DESIGNER

Kilby Smith-McGregor

PROOFREADER

Claire Majors

ADVISORY

Vera Beletzan

Senior Dean, Faculty of Liberal Arts & Sciences and Innovative Learning, Humber College

Bronwyn Drainie

Former Editor-in-Chief of the Literary Review of Canada ; author

Alison Jones Publisher, Quill & Quire

Joe Kertes

Dean Emeritus, Humber School of Creative and Performing Arts; author

Antanas Sileika Former Director, Humber School for Writers; author

Nathan Whitlock Program Coordinator, Creative Book Publishing Program; author

Humber Literary Review, Volume 11 Issue 1

Copyright © May 2023 Humber Literary Review

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without prior written permission.

All copyright for the material included in Humber Literary Review remains with the contributors, and any requests for permission to reprint their work should be referred to them.

Humber Literary Review c/o The Department of English Humber College Institute of Technology and Advanced Learning

205 Humber College Blvd. Toronto, ON M9W 5L7 humberliteraryreview.com

Literary Magazine.

ISSN 2292-7271

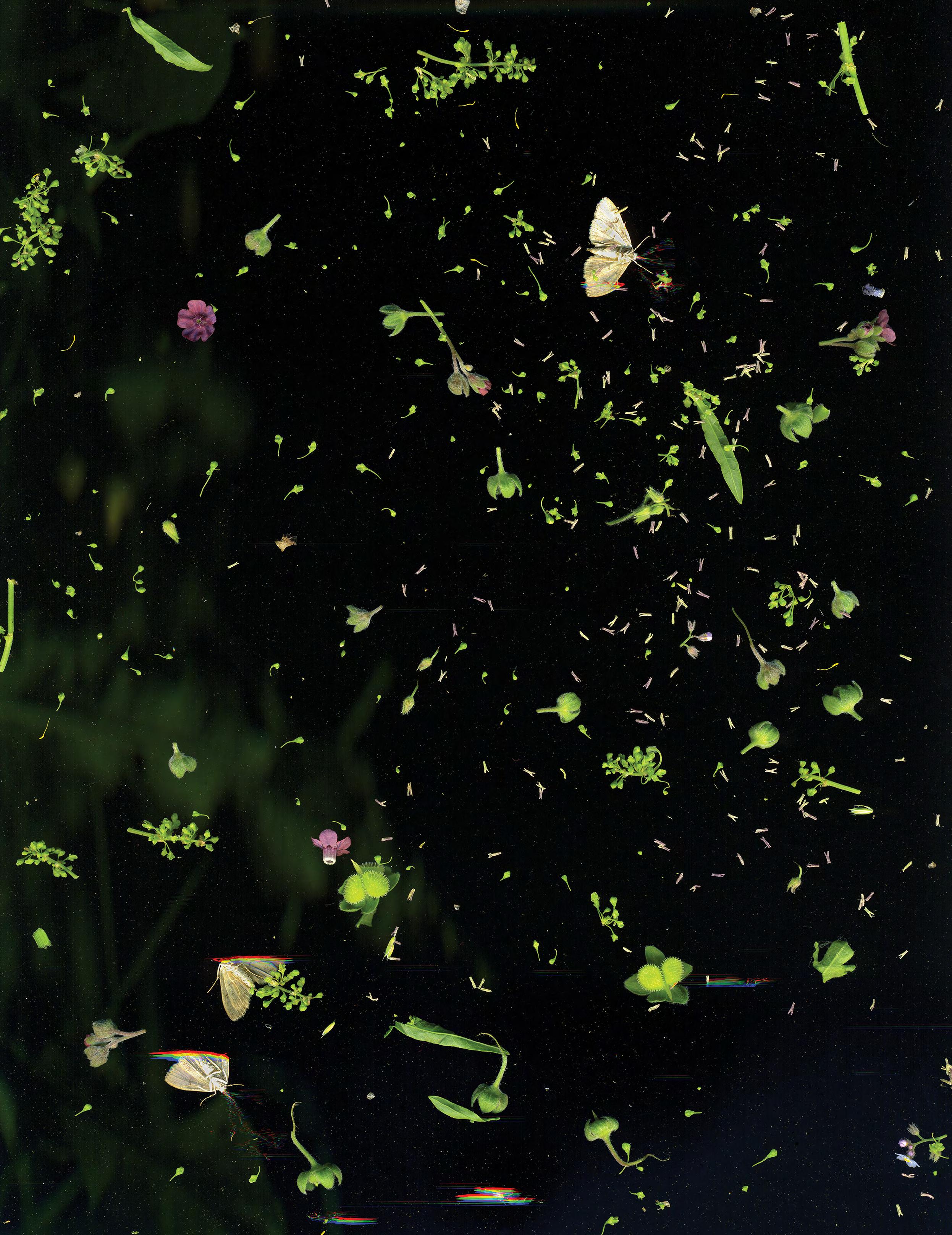

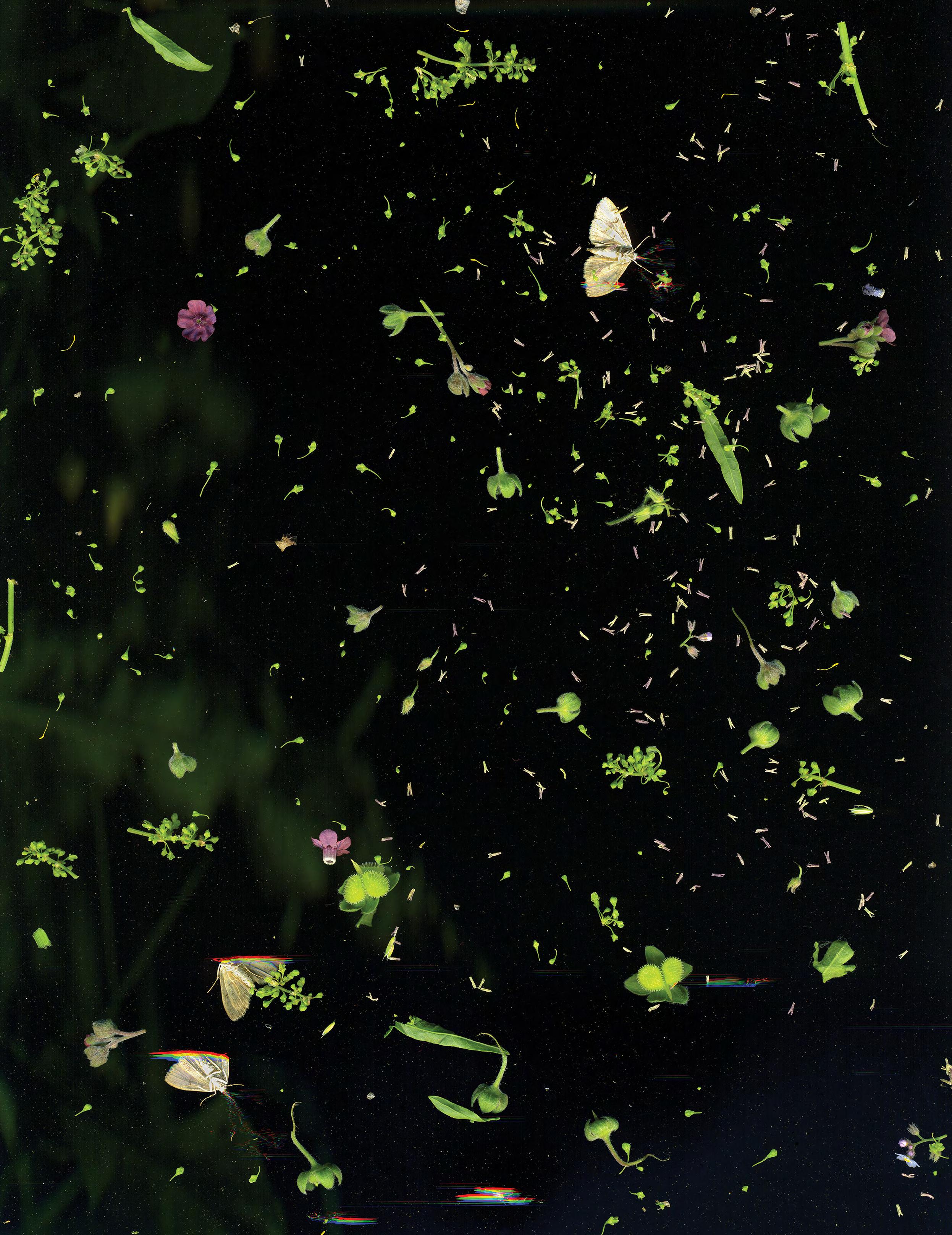

Layout and Design by Kilby Smith-McGregor Cover Image and Portfolio by Sara Angelucci

Humber Literary Review is a product of the Humber College Institute of Technology and Advanced Learning’s Department of English

Printed and bound in Canada by Paper Sparrow Printing on FSC-certified paper

Opinions and statements in the publication attributed to named authors do not necessarily reflect the policy of the Humber College Institute of Technology and Advanced Learning or its Department of English.

FRONT COVER | SARA ANGELUCCI NOCTURNAL BOTANICAL ONTARIO, (OCTOBER 14, MILKWEED #1), 34” x 47”, 2020 Image courtesy of the artist the Stephen Bulger Gallery.

FROM THE EDITORS

FATHERS FIGURE PROMINENTLY IN THIS ISSUE OF HUMBER LITERARY REVIEW. It’s always interesting to see what trends emerge in the work submitted and selected for each issue. Sometimes they are obvious, reflective of broader cultural issues. We’ve seen issues full of stories about immigration and displacement, for example, and another where—as we began to emerge from the pandemic—writers grappled with isolation and increasing seclusion. At other times, such as in this issue, there are thematic strands that one couldn’t possibly see coming.

Many of the pieces that deal with fathers grapple with the concept and expectation of fatherhood. This can be read most prominently in Alison Colwell’s creative nonfiction piece “Fairy Tale Fathers,” where she describes how her father did not respond to a quiet call for help:

He thought he was doing the right thing. But I wanted a father like Sleeping Beauty’s, a father who would burn the world to protect his daughter. Yet that’s not the kind of father I had. It’s not the kind of father most of the daughters in the stories had. Our fathers are human. Our fathers are imperfect. No woodcutter is going to storm into our lives, axe held high, ready to take out the wolf. We have to wield our own axes. We have to take charge of our own stories.

This specific concept of the imperfect father is reflected in some of the fiction in the issue as well. K.R. Byggdin’s “Good Night, Reverend” tells the story of a gender nonconforming child semi-estranged from their father, who is on his deathbed. In Eric Rausch’s “Not Built to Last,” a man asks his telepathic friend to sneak into his son’s thoughts in an attempt to try to influence the direction he’ll take in life to predictably disastrous results. And while not dealing directly with fathers, Cuban diaspora writer Ana Rodriguez

Machado’s poems do deal with parenthood and grandfathers (among other concerns).

Of course, this fatherhood theme is not the only thread you’ll find stringing the writing together in this issue. There are also a lot of pieces dealing with identity, specifically around gender and sexuality. Carla Harris’s beautiful and poetic piece of creative nonfiction “A Slowest Growing” navigates illness and queerness and does so by creating a hybrid form, blending confessional poetry and the personal memoir. Similar themes can be found in H Felix Chau Bradley’s short story “Second Appointment.”

Along with these thematic connections, there are many pieces that stand alone. For example, Morgan Dick’s “Autopilot Malfunction” is a story about a teen boy obsessed with studying videos and memorizing facts about 9/11, and Sue Murtagh’s “Rescuing Spiderman” employs an interesting use of shifting POV to tell a heartbreaking story about a mother’s grief. Adelle Purdham’s “Navel-Gazing” argues for the importance of creative nonfiction and other forms of personal writing that embrace the “I” as being essential in providing opportunities for marginalized voices.

The issue is also packed with fantastic poetry in varying forms by Matthew Rooney, Blessing O. Nwodo, and Sneha Subramanian Kanta and an excerpt from a wonderful graphic novel by Brigitte Archambault, and we have the privilege of featuring the beautiful artwork of Sara Angelucci.

Despite some of the challenging and heavy themes outlined here, even in the darkest moments, hope can be found in this issue. Returning to Carla Harris, their piece delves into some dark places but ends on a profoundly hopeful note, declaring that “I will celebrate love in the unforced way that it sprouts: organic in unexpected times and unfamiliar places.” A declaration and promise that all of us should take to heart.

Best wishes, The HLR Collective

RESCUING SPIDERMAN

It’s the first day of spring, but remnants of shrivelled, blackened snow litter the community pool parking lot. You’re here to try a swim. The so-called experts claim this will help you. To be precise, they say it should help but at first it might hurt; they promise it will not harm you.

So here you are—you try to please—wearing the royal blue Speedo with the tummy ruching that you bought because it seemed correct to begin with a new bathing suit. You’ve chosen to launch your (supposedly) healing habit at the mid-morning lane swim. At this time of day, the pool is quiet, just a handful of lumpy people muddling through the strokes, fumbling through chemically treated water that could irritate sensitive skin.

There are three others in the pool. Everyone stays in their own roped-off lane. The only vacant lane is in the middle. You’d prefer to stick to the outer edges but this is your only option, so you carefully bend down to remove your flip-flops and sit on the edge of the pool. The water feels cool on your legs. You fixate on the circling red hand of the analog pace clock they keep on the deck—it measures time in seconds only—before you lower your torso into the water. What was cool on the legs feels harsh on your arms and chest. You can smell the chlorine.

You have a hard time finding your rhythm. Your front crawl seems off, your breathing laboured. You attempt breaststroke, hands together as if in prayer and arms in a V as you glide, but that doesn’t work either, so you revert to the front crawl. Your goggles are tight—too tight—but at least they don’t leak. They allow you to see the pool bottom and the walls at the ends of your lane.

Your face in the water, a Band-Aid on the pool floor drifts into sight. Spiderman’s red-masked face stares, fixating on you with blank white eyes. He is large enough to cover a gravel-battered knee after a six-year-old races straight into trouble. Some kids are

unusually accident prone. You had one of those and you went through many boxes of superhero Band-Aids. You assumed Josh would turn out fine because you put in the work. You weren’t a “jellyfish parent” or a “brick-wall parent”; you and your husband learned to “talk so kids would listen and listen so kids would talk.” Smug you and your smug friends slurped up everything those parenting manuals dished out.

What suckers.

You make it to the end of the lane, turn around and push off the wall to swim back. You don’t know how long you can keep this up, even though you used to easily handle fifty lengths four times a week.

On the way back, the Band-Aid is in the same spot, but Spiderman has flipped. Now a bloody rectangle floating like a cartoon ghost between the painted lines of your lane. You swim over him.

You can’t remember if they advised you to focus on being in your body or to be a mechanical doll. You pick doll, mechanical swimming doll, because you don’t see any other way to continue, and you must continue.

But the Band-Aid lingers. Instead of drifting out of sight, it somersaults beneath you on the pool floor. As your strokes create ripples, the Band-Aid turns, plastic side up, then bloody side up. Crimson mask alternates with a brownish stain centred between strips of adhesive. This breaks your doll concentration.

You imagine the bandage loosened and fell off the little boy’s knee during family swim and no one noticed, or maybe they pretended not to notice so they wouldn’t have to deal with it. With every length of front crawl, every time you swim over it, your chest tightens. You could switch to backstroke so you don’t have to look, but you choose not to.

The pressure in your diaphragm builds. You came here to relax all you wanted to do was relax they promised this would be good for you relax mechanical doll.

That Band-Aid has to go.

SUE MURTAGH // 4 SUE MURTAGH

So you stop to alert a lifeguard. There are two guards on duty: one appears to be in his late teens, the other in his early twenties. Look at them—they move through the world in adult bodies with adult freedoms—but they’re still burdened with the frontal lobes and impulse control of teenagers. They have zero concept of the permanent consequences of their actions.

The older one is tall, dark-haired, and bearded. The brooding type. He looks familiar, but you can’t place him. The younger one is scrawny, skin raw with acne. In another time and place, your heart would break for him.

You pick the skinny one. You tell him about the Band-Aid. How gross it is, where it is. At first, it seems he will help. He asks you to point out the exact location, so you do head-up breaststroke, you stop and wave, gesturing that the spot aligns with an orange caution cone on the side of the pool. You want to make it easy for them to collect this debris. He nods and you continue your swim, expecting he’ll need you to get out of the way when he or the other guy cleans up. The skinny lifeguard approaches the bearded one. They confer; they part. You do a bit of breaststroke. You want to be reasonable, give them the benefit of the doubt, but you can’t wait.

“The Band-Aid,” you say to the skinny one when you finish that lap.

He tells you the long pole with the little net on the end—the skimmer—won’t reach that far.

“So we’d have to drain the whole thing,” he says. That’s just the stupidest thing you’ve ever heard. Ridiculous. He’s lying to you, lying.

You say so. What kind of people are they hiring these days? You say this too, which prompts him to wave over the other guard.

“If he can tear himself away from his phone,” you say. When your son Josh patrolled this deck, it was different. He’d be in that water in a minute. Jump in. Jump right in without thinking.

The bearded guard arrives to impart his wisdom.

“So the net won’t reach,” he says.

“I’ll do it,” you offer, to shame them, and they’re too lazy to even shrug.

You do your best head-up crawl back to Spiderman. Before you dive you look back to the pool’s edge where the young men still stand. Bearded One wears a smug smile, while Ravaged Face bears no expression other than stupidity. You, a taxpayer, are paying these useless specimens to watch you dive for someone else’s garbage. They’ll probably laugh about you at break time. It turns your stomach. You know you look like some entitled hag, but you don’t care.

The Band-Aid hasn’t moved, but reaching it is difficult. On the first try, Spiderman eludes your clumsy

hand. You pop to the surface to see the guards still gawking. Claustrophobia circles; panic will smother you. But you try again. You channel the mechanical doll. Long, slow inhale, long, slow exhale before you dive. You move deliberately; you don’t grab. You see the hairy kicking legs of an old man two lanes over.

This time you succeed. You spread your fingers like a net to block off escape routes and close your fist around the plastic. Spiderman caught in the palm of your hand.

Your task is complete. This moment should feel good, but the used bandage seems inconsequential. You swim over to the edge of the deck. It isn’t easy to swim with one clenched fist. You dump the Band-Aid on the pool deck. The younger lifeguard reaches over to collect it. You notice he now wears a blue plastic glove to protect his precious hand. The other guard just walks away.

That’s it. No one thanks you, of course. No one cares. And then you realize who the bearded lifeguard is. He was three feet shorter when you met him. You’re sure you know this kid. He’s one of the four Sams who were in Josh’s class. There were always multiple Sams— in hockey, in basketball, in the school band. For years, all you did was hand out granola bars and juice boxes to Sams. Even then, this one stood out as whiny and sullen. He was invited to birthday parties when the thing to do was to include the whole class, but he was never one of the guys Josh had over after school or on weekends. Not a friend.

A current of adrenaline races from your feet to your heart. Your pulse pounds. There’s sudden, excruciating heat on your damp skin, and yet again you can’t catch your breath. You raise your body out of the pool. Now you are on the deck. You approach the wall. Hanging horizontally is that scoop they claimed wouldn’t work, that they refused to even try. It looks like a giant butterfly net.

You tear the scoop from the wall, throw it like a spear and watch it fly into the water. It lands well into the deep end of the pool, which is roped off because people aren’t allowed to swim there at this time of day.

The aluminium pole bounces gently, silently, and then floats. Not satisfying.

You spy plastic bins of the pool noodles they use for aquafit class. The green, pink, and orange noodles are insubstantial weapons, inadequate, but they’re all you have. You launch your missiles one by one. Airy foam, they land lightly on the surface of the water and barely make a ripple.

So you try a lifejacket. You grab one from the metal box on the pool deck that looks like an open-topped cage. You hold the jacket over your head and throw

SUE MURTAGH // 5

so hard and fast your triceps feel like they’ll snap like twigs. Fluorescent yellow flies twenty feet and lands daintily, with minimal impact, the straps splayed on the water surface. What you need is a deep, hard splash, a thud, a rogue wave, a tsunami. Instead, brightly coloured buoyancy cheerfully decorates the deep end, insulting you. A pool party with a missing birthday boy.

The lifeguards finally notice and come after you. Women your age are invisible until they make trouble.

“Is there enough crap in there now to get your arses into the water?” you say.

“That’s disrespectful. Not appropriate,” the guard who must be Sam says.

“Whoop-de-fucking-do.”

In the old days, you never used this language. You were the endlessly patient mom with the constant smile, handing out melting ice-cream cake and disappointing Dollarama goody bags. Where did that get you? Nowhere.

You notice the scoop pole is no longer completely afloat. It tilts at 45 degrees and may yet sink to the bottom.

“You little fucker, I know who you are,” you say to that little shit Sam, and still he does not recognize you.

The lifeguards radio me to help them deal with another breakdown on the pool deck. These clowns can’t handle anything by themselves. For this, I get an extra $2.58 an hour, a cubbyhole office behind the front desk and a hand-me-down name tag with no name on it that says Daytime Rec Supervisor. Yesterday, it was a middle-aged perv with greasy hair who hung around on the pool deck, playing with his phone. He needed the Wi-Fi, he said. The guards claimed he plunked his butt on a bench and stared at the junior swim team. Mega-creepy. I told the guy that the library has great signal strength.

Just down the hall. Off you go, buddy. Today, I hear the problem before I see it. A woman’s voice, angry: “Why the fuck are you here? You’re useless.” Good question. I sometimes ask myself that.

“Why?” the woman shrieks, straining her voice to the breaking point.

I know her as soon as I hit the deck. It’s Josh’s mom. I’ve only met her once and I was one of hundreds streaming past the family that day, but it’s her. Screaming, poking at Cory “why you,” sticking a finger in Sam’s face, “and why you.” Coat hanger shoulders under a layer of pale, wet skin, and her blue swimsuit is too big. Spiky, salt-and-pepper hair sticks up from the black goggles wrapped around the bones of her skull. I call her by her name, “Mrs. LeBlanc.” She freezes, then wobbles like someone about to faint.

I don’t feel too steady myself, but I offer my hand: “I’m Sarah. I worked with Josh.” I doubt this sinks in, but an instinct for politeness draws her hand to mine like muscle memory. Her palm is damp and cold; I hold on tight and lead her away from those gaping idiots.

We walk across the pool deck to the sauna with an Out of Order sign, and I open the door. She’s transitioned from yelling to dazed and comes along passively, as if this is not super weird. I close the sauna door, and we sit on the lower bench.

“And let’s take off those goggles,” I say. “You’ll feel better.”

Again, she does what I ask. The goggles leave deep purple indentations around her eyes, as if someone punched her twice. Maybe she doesn’t know that it’s suction that keeps goggles from leaking, not death-grip tightness. Or maybe she just doesn’t care anymore.

I take her hand again and rest two fingers on her wrist to check her pulse. Her heart is racing. I ask if she has tightness in her chest, pain in her arms. Yes, she has pain in her chest every day, all day.

“Do I know you? Do you know me?”

I tell her again that I worked with Josh, how we took our certification course together, that we were weekend morning shift partners. Buddies. We took breaks here in the sauna, which was broken most of the time because the maintenance guy was and still is a tool. Her bruised eyes show a flicker of life and interest as I talk about her son. When someone tells you a new story when there can be no more new stories, it’s a gift.

“We’d hide out. He always made me laugh,” I say, and that’s mostly true, the exception being at the end, the last few months, when he’d come to work still half-wasted from the night before. She doesn’t need to know that.

Then she unreels a tale about a filthy Band-Aid. I nod at the right times. It’s not the moment to break the news that there’s always crap on the bottom and, sorry, that’s just the way it is.

Her words come slowly, as if she struggles to construct a story from long ago, details fuzzy. And then she just stops mid-sentence and slumps, chest collapsing onto her thighs. I realize that my fingers are still on her wrist and that her pulse has slowed.

I’m tempted to tell her about my brother, but don’t. There’s a fine line between empathy and saying “I know just how you feel” when that isn’t possible. It always pisses me right off when someone jumps into their own shitty tale. Shut up for a few minutes and let me have my own story. This isn’t the Pain Olympics.

So I say, “Mollescum contagiosm.”

SUE MURTAGH // 6

Mollescum contagiosm. During our first shift together, Josh told me that he came to a birthday party here when he was seven or eight. A week later, he broke out in the grossest bumps. Red, round, and shiny— they covered his arms and chest, he said. He had to smear on smelly cream for almost a year, and every few weeks the doctor burned off new growths as they erupted. Kids at school made fun of him.

The next time I heard the story, at a work party with a proper audience, he played it for laughs. “Bumps from the top of my head to the crack of my ass,” he said, and we all roared.

“He never complained, oh but I was so angry,” his mother tells me. In her version, some kid came to the pool with the virus, and it was her son—only her boy—who caught it. Josh was in the same pool doing the same things that everyone else was doing, but he was the only one who got nabbed. It was a one-in-amillion thing.

“It wasn’t fair,” she says.

I tell her she’s not wrong. “None of this is fair.”

In a fair world, we’d sit quietly together now, in peace.

But this is the real world, and the wooden box we’re hiding out in isn’t soundproof. A muted but still crappy Coldplay song drifts in as the warm-up for aquafit begins out on the pool deck.

She starts to talk again, tells me that a few days ago she went into Josh’s old room to rummage. Her husband warned that there was nothing new in there since the last time, but she was restless.

“I had no idea what I was looking for,” she says.

In Josh’s top dresser drawer, shoved under the flannel pyjama pants she gave him that last Christmas, tag still on, there was a stack of swim instructor material.

“Certificates, swim badges, blank lesson plans. My husband was right. Nothing new.”

Now I can’t help myself, and I tell Josh’s mother about my younger brother. I don’t insult her with the “I understand” line. I just tell her what happened. I’m not looking at her face anymore; I’m looking down at my fingers on her wrist, relieved that her heart rate hasn’t sped up again.

“He wouldn’t have taken it if he’d known what it really was.”

She doesn’t speak, just sighs: an intake of breath so prolonged it must be deliberate, and then an eternal exhale.

I finish by saying, “Nowadays, I write in a journal; sometimes I go to a group.”

I don’t tell her that on the dark, shitty days when I’m furious and want to hurt someone I choose to hurt myself, that I call in sick and close the drapes and

drink Mike’s Hard Lemonade and binge Netflix all day in dirty sweatpants. I don’t tell her that I have nightmares about the night the cops came to my own mom’s door. Or that now I keep Naloxone in my car and at my apartment, that I double-check our pool supply at every shift.

Instead, I blurt, “Bring it all in, and I’ll take care of it.”

“What?”

“I’ll take those swim badges and stuff off your hands.”

She nods, and then asks if she can go to the change room now, that she just wants to go home. I tell her she’s allowed back in the pool whenever she’s ready, that I’ll talk to the guards. Maybe next time will be better.

“I see myself do these things. I yelled at some girl on the bike trail the other day because her stupid German shepherd wasn’t leashed. ‘Oh, he’s well trained. He’s friendly,’ she said, and that just set me off.”

I get up and she follows. “Don’t forget to bring me that box.”

The goggle marks around her eyes are fading. “Yes. Someone should use it. Otherwise, such a waste,” she says.

The truth is that if she does part with all of Josh’s leftover lifeguard crap, it will end up in the garbage. They chucked out the old learn-to-swim program last winter and brought in a new one. I might store the carton in the swim office for a few days, but ultimately its fate is the dumpster out back.

But at least Mrs. LeBlanc won’t have to look at it anymore.

I lead her to the change room. “On we go,” she says, and her tone has the forced cheer of a weary Girl Guide leader heading out on a hike, as she pushes through the door on her own.

On my lunch break I go outside. The pool, my office, all of it is suffocating. The pervy pool guy is sitting on the next bench, hunched over his phone, hood pulled up over a grimy ball cap. The Wi-Fi signal is strong out here. It floats out to the metal chairs and wooden benches where people with no Wi-Fi at home arrive before the library doors open and stay after the doors close, even in cold weather when the garden is nothing but rocks and dead leaves. My logical brain knows he has as much right to be here as anyone else, but today he makes me angry, makes me feel he’s taking up a space reserved for others.

SUE MURTAGH // 7

///

ANA RODRIGUEZ MACHADO // 8

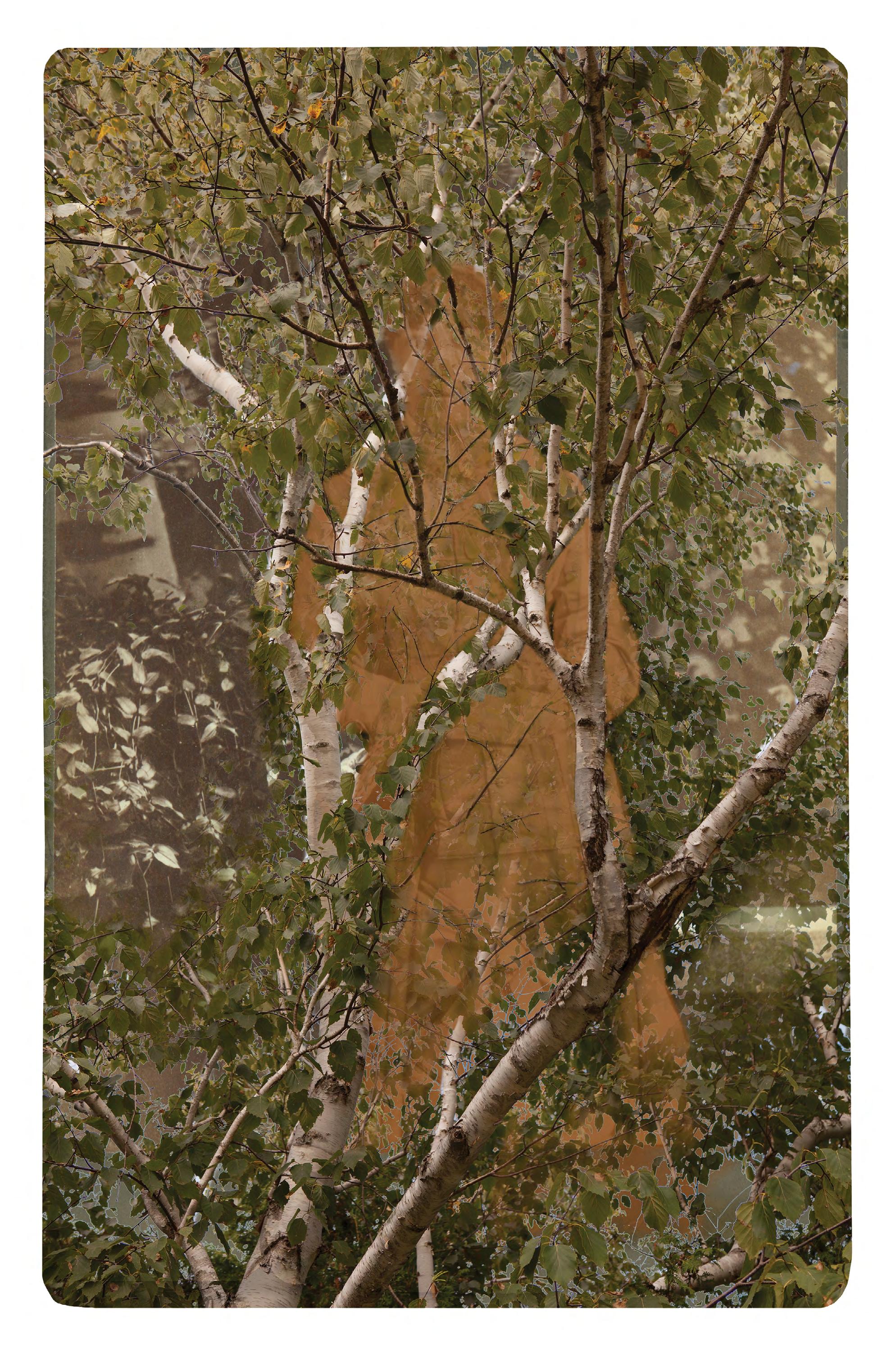

ARBORETUM, (MAN/WOMAN/PINES), 31” x 44”, 2016 | SARA ANGELUCCI

Image courtesy of the artist the Stephen Bulger Gallery.

ANA RODRIGUEZ MACHADO THREE POEMS

THERE ARE TREES HERE

AFTER JAMAAL MAY

tell them there are trees here. when they cannot hide their surprise that you are smiling tell them again: there are trees here. when they pat the top of your head and smirk, like they can’t bear to reveal to you the fact of your despair, tell them again. there have been trees here stretching down for thousands of years before That Man tried to burn everything green and there will be trees long after he turns from ground to dust. there are trees here and children digging under them. there are llorones and date palms and arecas scratching old skin with long fingers. there are games of trompo and suiza and dominó. there is sugarcane and burnt coffee and old ladies yelling at young ladies yelling at dogs. tell them there are men who will tell you they love you again and again till the next jeva shows up. there are mothers sewing new dresses from old dresses from curtains from manteles. when they pierce you with their unbelieving stares, tell them again.

you are not talking about hunger or big words that end in –ismo, you are talking about your mother and her mother, and what it’s like to feed a man inside your house and what it’s like to weep at the death of your father and, no, again, you are not talking about death from starvation or shame, you are remembering a man who ate everything he wanted from life before life ate him. and, no, you’re not trying to get into politics or free mojitos and, no, you do not know when the oldest brother will die and what will happen when the Americans arrive. keep trying to tell them. repeat it again. between buildings dripping with age and abandoned construction projects, behind propaganda billboards and faces of big bearded men making promises we will all die to keep. they are growing as we speak, digging their roots deep beneath the crocodile at the bottom of Caribbean Sea and I know you are tired but know you must keep telling them tell them again, again, again so they don’t forget.

ANA RODRIGUEZ MACHADO // 9

MY MOTHER IS A PROSE POEM

My mother is lucky like she got everyone out, not in time but enough to make a fire last the month, my mother is strong like she laughs while her stomach turns to ashes and what makes her go crazy is we let the bananas go bad, my mother is clean like the floors look like no one’s ever lived here and she’s happy we won’t have to hide the dust under our tongues, my mother is mad like she hugs us without reaching the ceiling and no man is ever gonna change anything, my mother is music like she’s a violin staccato and no one can catch her like a fox gone too far into wood, my mother is sorry like she laughed at her son’s good intentions, let her daughter drill holes in her skin, and no one forgave anyone, my mother is mine like she gave away hearts she picked up on the street so her children could see something other than this, my mother is

ANA RODRIGUEZ MACHADO // 10

A DIME OF GUTS

My grandfather used to say un real de tripas was something that never ended A story from a neighbour when your boots met in the stairwell Or a republic Un real es diez centavos in the old colony’s dime They called it un real de plata fuerte Dime of silver strong No mi abuelo called it un real de tripas tripas being a pig’s intestines A dime’s worth of guts thick silver unbreaking More guts than anyone ever needed The way a story never ends when you want it to The way a man’s beard can grow and grow My grandfather was not a dime or a peceta’s worth of guts His guts did kill him though or was it the republic We spill guts trust guts stuff guts with silver unravel guts like yarn When something follows something for so long it reels stacks of dimes and lifetimes of pesos in shirt pockets

The old colony did stop sending them eventually Just like someone’s guts eventually end in light if you lay them out flat

ANA RODRIGUEZ MACHADO // 11

///

H FELIX CHAU BRADLEY

SECOND APPOINTMENT

The appointment is quick and painless, so unexpectedly simple that I forget to rejoice when it’s over. Seated obediently at station G, luxuriating in the air conditioning, I look away from my arm for a moment, glancing around the echoing auditorium to see if I recognize anyone. Anyone’s upper face at least. Not to chat or even to say hi, just out of sheer curiosity, a sort of rubbernecking instinct that I have rarely been able to exercise for the past seventeen months. Maybe a glimpse of a new couple that has formed in the muffled stretch of time since anyone has run into anyone. Some gossip to bring back home to Hari.

Hari seems sick of me lately. They have burrowed into themselves. I keep catching them folded up uncomfortably on pieces of furniture, squinting at their phone. I don’t see anyone of note. When I turn back to show the nurse I’m paying attention, I realize that she is already completing the swift gesture and throwing the used needle into the receptacle, nodding at me.

“Good job,” she says.

“That was fast,” I say, or something similarly meaningless. “Been here long?” I ask her.

“Since 7:00 a.m.,” she says.

“Oh yeah, long shift,” I say, and I try to think of what I can say next to keep seeming friendly and grateful, but she’s already indicating the relaxation area where everyone has to wait for fifteen minutes before we can go back outside into the blaring sunlight.

At minute twelve, there’s a shout from behind me. I crane my neck around. A teen boy has fallen from his chair to the ground. We all gasp, or maybe I just imagine a collective response because I can’t fully see anyone’s face. A woman, his mother I assume, yells for a nurse. Two nurses are at the boy’s side in seconds, having materialized a wheelchair from a nearby nook, and he’s revived and being wheeled away with a water bottle by minute thirteen. “Did this happen to you last time?” one of the nurses is asking him. “No,” the boy

says. “Never happened to me before.” He seems lucid, calm. It was just a momentary collapse. Everyone relaxes back into their chairs once he is out of sight, behind some plastic sheeting. The digital clock blinks 16:35. I pick up my bag and sling it over my shoulder. My arm doesn’t even hurt. I push through the swinging doors into the muggy afternoon and bike home, squinting into the sun.

“Igot it!” I announce to Hari as I walk in the door. I waggle my arm at them, letting the fat ripple peacefully, like a sail. They used to appreciate this sort of thing about me. They used to praise me from head to toe until I blushed and squirmed out of their arms. Now, they barely look up from their screen. Their long body is folded up, like a bunch of tent poles, in a plastic garden chair that we salvaged from the sidewalk last year; a pile of dirty plates and glasses languishes beside them on the floor, within reach of their left arm. The apartment is thick with jasmine incense. The incense sticks smell alluring to me, until they’re lit. Then, they ignite an unshakable nausea. Hari knows this, but neglects to alter their behaviour. Incense is the only thing that calms them, they sometimes remark when looking at me. As if I’ve challenged them in that moment when in fact we may have had a disagreement the night before about something totally unrelated. Holding my punctured arm gingerly, I prop up one of our ancient windowpanes with a plank of wood. I fumble for the cord of our tiny metal fan and plug it into the socket behind the overloaded bookshelf. “Maybe you should move your appointment up. I saw all these people get through in the drop-in line. Then we’d be on the same schedule.”

“Nah,” says Hari, thumbs flicking, then tapping furiously. Are they playing a game or messaging someone?

“Why not?”

H FELIX CHAU BRADLEY // 12

///

NOCTURNAL BOTANICAL ONTARIO, (AUGUST 15, CARDINAL FLOWER, MINT, JOE-PYE WEED), 34” x 47”, 2022 | SARA ANGELUCCI

Image courtesy of the artist the Stephen Bulger Gallery.

NOCTURNAL BOTANICAL ONTARIO, (AUGUST 15, CARDINAL FLOWER, MINT, JOE-PYE WEED), 34” x 47”, 2022 | SARA ANGELUCCI

Image courtesy of the artist the Stephen Bulger Gallery.

Hari shrugs. They can’t be bothered, I think, irritated, even though not being on the same schedule means more and more negotiations about where each of us is going and who we are seeing outside of our household. The mutual sense of purpose that felt so natural in the early months has become laboured. I can’t pinpoint when it began, but now Hari orders take-out most nights without telling me and eats it in whichever room I’m not in. Sometimes even in the bathroom, which I find weird. Also, the measure of weird has morphed and bulged over the past year or so, and I don’t have it in me to say anything when I find globs of harissa under my feet in the shower. When they aren’t ordering takeout, they don’t seem to eat anything at all.

“Can we try to eat dinner together a few times a week?” I had asked them when it had first started.

“I just want to do my own thing for a bit.” They looked up from their phone, their thick brows knitted together. “We’ve been doing every single thing together for, like, two years.”

“It hasn’t been two years,” I protested. “Not yet.”

“I just need some space to myself,” Hari said, their expression softening a little. They gave me a half-smile. “I’m researching stuff. I need to concentrate.”

Since then, I’ve tried to remember that Hari wanting space isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Maybe some extra space to think will be good for both of us. Relationships have to ebb and flow. Like the seasons, the tides.

droning above. I knew that Hari had lived with several other partners before me, and that every single one of these cohabitations had ended badly. But maybe they were right. Maybe what had been missing in those other partnerships had been an abundance of quality time. There was no need to be paranoid: Hari positively beamed every time they looked at me. They got me excited about trying new recipes; they filled our bathtub with essential oils and rose petals for me. They introduced me to sex toys I’d never even heard of before, made my pleasure into a special project. This was love, I had thought. It was a little frightening how quickly it had come about, and sometimes I worried that I barely knew Hari at all, but with the world daily becoming more unrecognizable and more terrible, surely I could allow myself a little joy, even though I knew better than to say this to any of my friends who had been forced to hole up alone.

Technically, we do spend all our time together, but it never feels like we connect anymore. At the beginning, every day had been an ebullient adventure despite the worsening global crisis. Hari had been the one to suggest that they move in, even though we’d only been dating for two months—their belief in our romance was infectious back then. They had been so sure about us, so sure that the crisis and its attendant regulations were a “blessing in disguise” for our relationship. “Now, we’ll really have time to fall in love with each other,” they’d said, as we spooned in my creaky double bed, listening to the strange silence outside, the lack of traffic, the lack of airplanes

Now, in an attempt to prove to Hari that I can do things on my own, I’ve started growing vegetables on our cramped back balcony. My friend Milo helped me lug sacks of soil and compost up the fire escape. I spend my time defending the spindly plants from the hot summer wind, the random hail storms, and the increasingly hungry back-alley vermin. A muscular grey squirrel watches me daily from its perch on a half-dead maple that grows out of the neighbour’s backyard. At night, it makes numerous holes in the soil, and when I dig around, I find strange treasures: a length of red yard, a metal button, hunks of mouldy bread, three green twistties. Never anything that could actually be dug up in winter to eat. “What are you doing?” I shout to it. “This isn’t the way to survive.” I make embarrassingly small salads for myself: three leaves of bumpy dark green kale, three barely ripe cherry tomatoes, a handful of arugula that looks to have been chewed by small jaws, five chives, and some nasturtium flowers. “They’re edible,” I say to Hari. “Look!” Like I’m a magician at a children’s party, I wave my hands in front of my face and then pop the soft orange petals into my mouth, closing my eyes. When I open them, Hari is looking at their screen, frowning.

“What’s wrong?” I ask.

“Nothing. I’m just doing research.”

“Research about what?”

“About the current situation,” Hari looks at me ominously. The current situation is indeed ominous, but there’s something about the glint in their phonedazzled eyes that disturbs me. “You really shouldn’t have gone to that appointment the other day; we don’t know the risks. Something bad could happen to you.”

“What are you talking about? You’re still going to yours, aren’t you? You already got the first one. What’s the big deal now?”

H FELIX CHAU BRADLEY // 14

Now, in an attempt to prove to Hari that I can do things on my own, I’ve started growing vegetables on our cramped back balcony.

“I’ve set it aside until I know more,” they say. They peer at the tiny salad. “Did you use any pesticides when you grew all this?”

“Have you talked to any of your friends lately?” I know they haven’t. In response, they turn over on the couch so that their broad back and tangled overgrown mullet is all I can see. I suspect that they’ve been getting into arguments with everyone they know. I’ve scrolled past heated discussions in various queer Facebook groups, and on Twitter, but haven’t wanted to look any closer. If I don’t read their new beliefs, they won’t take shape in the real world, I tell myself. Whatever they were saying to people online, I thought, isn’t any of my business. I can’t face the thought of being even more alone than I already am.

everywhere, multiplying daily. I’m trying to avoid using any chemical sprays, for fear of Hari’s reaction.

“Maybe your role-plays are your new way of communicating.”

“Maybe,” I start clipping away at infested leaves. But I can never remember what we say during those hours. The whole thing with role-plays, I think, is that you aren’t meant to remember them afterwards. If you knew you’d remember them, then you’d never be able to go through with any of them. I notice that something has dug up all my radishes, their plump pink forms gnawed at. Something or someone. Much as I hate losing my tiny crops, I begin to find something comforting about the physical evidence of visitation. Does the squirrel love me? I start to wonder. Does Hari?

ari and I still have sex,” I find myself declaring to Milo, who is aware of the increasing distance between us. We engage in increasingly obtuse role-plays, which come on suddenly, like weather, and recede just as quickly. “I’m a city bus that’s running seven minutes late and you’re the driver,” Hari might declare, rounding the corner into the living room. “I’m a contested parking ticket and you’re the clerk at the municipal court,” I might decide, slinging myself down the hallway to where they’re searching for something in the hall closet. “I’m a cockroach-infested slumlord property and you’re a corrupt building inspector.” “You’re an increasingly dangerous pothole and I’m a fed-up suburban commuter.” Then we’re shucking off our clothes, licking each other’s fingers and teeth, strapping on various apparatuses, knocking against walls and doorframes, slapping against the top of the stove, the side of the dryer. Anywhere but the bed. The bed is for sleeping and stewing, we decided long ago. We barely touch in bed. The timing of the sex has nothing to do with whether anyone comes or whether the narrative of the particular role-play reaches its conclusive arc. The end might be signalled by the buzz of the doorbell in a neighbouring apartment. The yowling of the tabby tom in the alley. The juddering finish of the rinse cycle. As one, we know when it’s done. With a gesture, we begin to pack away the dicks, we walk silently to the bathroom to ward off UTIs with urination, we rinse off the harnesses in the sink. And then, we separate, back to our various personal corners of the apartment.

Milo assures me that this is a healthy sign, the continued sexual action. “Still, we never speak to each other anymore,” I say, picking crunchy aphids off of a sun-fried pepper plant. Their tiny green bodies are

I keep my mind hooked to deadlines. If we get through this month, it’ll be fine. If we get through this week without all the plants dying, it’ll be fine. But also, I find myself unable to imagine anything beyond the next month or two. I have a writing grant that’s meant to last me until the end of the year. Hari is on government assistance, also until the end of the year—like everyone, or at least everyone we know. What happens after the end of the year? A massive hole, which I feel almost eager to disappear into.

A few days after my appointment, I notice a swelling pain in my crotch. I’m on a call with my granting agent, trying to explain why I haven’t been able to write anything, when the throbbing discomfort becomes so insistent that I have to bow out and lie in bed for the rest of the hour. Later that day, in the midst of an elaborate role-play about an unidentified life form and a paranormal investigator, Hari, face buried between my legs, raises their head to tell me that the whole area is inflamed. “Yes, I can feel it,” I tell them, but I’m impatient—the urgency of what they’ve been doing to me is primary. “Don’t stop!” I order, even though I’m the investigator and thus playing the more passive role to their probing alien. They shrug and go back to tonguing me. This time, thanks to the expertly judged insertion of a vibrating butt plug, I do come.

Part of me hopes that the new swelling is my genitals clueing into the signals from my brain, taking on the work of transformation without me having to go on hormones. Milo, who’s been on T for several years, rolls their eyes at this. Their attitude towards hormones is matter-of-fact: if you think you want to try them, just get on them and see. Quit blathering on about the undefinable and tragic mysteries of your identity and how your body will never match your soul, how you are doomed to a life of being misunderstood and dissociated.

“You’re still miserable and dissociated,” I rib them, deliberately mishearing the first word.

H FELIX CHAU BRADLEY // 15

///

“H

Creative Writing–Fiction, Creative Non-fiction, Poetry Correspondence Program

Looking for personalized feedback on your manuscript? Our 28-week online studio program is customized to address the needs of your booklength project. Work from the comfort of home under guidance of our exceptional faculty.

Program starts every September and Januaryapply now!

There is a story to be told here.

humberschool forwriters.ca

“Yeah, but that’s in response to the world we live in, not to the inherent dissonance of my physical and metaphysical forms.”

Can I blame them? They’ve heard me whine about my gender uncertainty every day for the past year and a half, at least. But Milo is aggressively and athletically single and never sleeps with the same person twice, which I sometimes envy, especially lately, but which also means that it’s hard to trust their long-term monogamous relationship advice. They talk about my relationship with Hari as if it’s some sort of necessary financial investment—something that we both need to do, sacrifices notwithstanding, in order to be in a good position later in life. Milo has a large inheritance and therefore does not need to worry about this sort of thing, they say, frowning slightly in sympathy towards my predicament. “Acknowledging their privilege” is their new thing. Sometimes it is unclear whether we are talking about the stock market or romantic love or something else entirely.

Hari, meanwhile, is aggressively against going on hormones. “Just for me,” they say, when they argue with Milo about it. “I just don’t want to put foreign content into my body without knowing the full effects.” Milo argues that there are plenty of studies and that it’s not like T shots are some kind of unresearched new experiment. Hari doesn’t back down. “I just don’t like the idea, and you should be wary as well,” they say placidly, which gets Milo even more agitated. I usually leave them to fight it out. I can’t decide anything with the two of them constantly at it.

“Do you want me to have a look at your junk?” Milo asks me. They trained as a midwife for some time before losing interest, so I suppose they do have some sort of expertise about genital appearances.

Lying on the couch with my legs open, my back sweat dampening the velour, I let Milo prod me until I’m obliged to shout that they’re being too forceful. “If you weren’t so averse to mirrors,” they say, trailing off. They know that I find all angles of my body horrifying to behold. We’ve known each other since we were teens and have seen each other naked, fucked up, passed out—and worse—so many times that I trust them more than I would a mirror, anyway.

“It’s definitely swollen,” they say. “But not in the way you’re hoping for. More on the side—I think you have a cyst on your outer labia, kind of a big one, actually.” They say “labia” in a half-whisper, as if I might be damaged by hearing it. “Whatever you do, don’t try to lance it. It will become much more swollen and painful, probably, and you’re going to need to take about five hot baths a day, which will eventually result in the whole thing popping and draining.”

H FELIX

// 16

CHAU BRADLEY

I groan. I hate baths. And it’s 35 degrees out. “What am I, a hotpot lobster?” I say. “You learned this in midwifery school?”

“No, I used to get them all the time,” Milo says. “They were psychosomatic manifestations of my trauma bond with my mom.”

“Oh.”

“But after we went to family therapy together— remember?—I never got one again!”

“So you’re saying that the baths don’t actually work, that I have to address my deep-rooted inner pain or something? My mommy issues?”

Milo looks at me. “Well,” they give me a careful pat on the thigh. “Maybe try the baths first.”

writing office, which they have announced is now their bedroom. They can’t risk breathing in my “vaccine shedding” at night, they say. Afterward, I run the hottest bath I can coax out of the old lead pipes and submerge my lower half in it, shouting in pain. The pain is something tangible, and it has a purpose.

Inevitably, my cyst curtails Hari’s and my sexual activity. It’s too painful. I try fucking them instead, summoning my topping energy, but even being turned on without being touched causes a riotous throbbing that goes far beyond fun and into the unbearable. I start to panic. If we can’t have sex, what are we even doing together? As it turns out, this is the least of our worries.

“Maybe it was your second shot,” Hari says, as we lie side by side, the fan rippling hot air across our stomachs.

“Maybe what was?”

“Your mystery swelling.” They aren’t looking at me. My brain flips over. I think about the online arguments, the articles I’ve glimpsed them reading on their phone. “What Doctors Don’t Want You to Know.”

“You’re kidding, right? It’s a cyst, Milo said so. It has nothing to do with—”

“Well, I’m really worried about you—about us. I’m reading a lot of stuff out there, personal anecdotes, things the authorities don’t tell us. You’re sitting around trying to write a navel-gazing memoir and ignoring the actual news.”

“It’s autofiction,” I protest, “and I read plenty of news.” My voice comes out whiny, makes me sound defensive when I want to be confident, an authority on the truth. “The news you’re reading isn’t news—it’s conspiracy theory bullshit, the kind we used to make fun of together, remember? Flat-earthers? We even did a role-play. Come on! You’re not into that stuff for real, are you?”

“If you don’t respect my bodily autonomy, this situation is untenable for me,” Hari says. I start to laugh before realizing that they are in earnest.

For the next week, I take five punitively scalding baths a day. This helps me to stay off my phone, which is blowing up with the increasingly incoherent messages that Hari sends me from the other room, about the dangerous toxins I’ve put in my body, how these may have rubbed off on them, how I violated their trust by bringing foreign substances into our home. They send me paragraphs of text about how I was never trustworthy to begin with, how our entire relationship is founded on lies, and how I obviously don’t love them since I am “putting their survival in jeopardy” by not respecting their needs. “You are selfish to your core,” they write. “You never wanted to make space for me in your life. And now that you’re tired of me, you want me to get sick and die.” When I read this paragraph, a nauseous chill rises from my chest, up my neck and into my face. How can they possibly say I don’t love them, that I’m trying to get rid of them, when they are the one who’s been abandoning me, day after day, for months?

Hari lugs piles of clothing and a random assortment of items that they have decided are theirs into my

Shivering with indignant hurt and despair, I lower myself into the water. Should I have loved Hari differently? Is there something I should have done, a different way I should have been, that could have stopped this from happening? Should I have given them more space, or less? I let the water boil my skin bright red. I let the steam mix with the terrible humidity of the city until my forehead is bathed in sweat and my mind can’t hold a single thought. Not a worry about Hari, not a stab of hurt at their accusations, not a fear about what’s to come. I lie there, breath shallow, head empty, prodding my crotch every so often, waiting for the moment when the thing that is wrong with me will pop and drain away.

H FELIX CHAU BRADLEY // 17

///

///

///

“If you don’t respect my bodily autonomy, this situation is untenable for me,” Hari says. I start to laugh before realizing that they are in earnest.

FAIRY TALE FATHERS

We have notions about fathers, ideas about who they are and the role they fill in our lives. Fathers are caring. Fathers are supportive. Fathers are loving. They are the bedrock from which we can grow and become all we have the potential to be. It’s all nonsense. I don’t know where we get these ideas. Fathers in fairy tales, as in real life, don’t always embody these ideals.

Cinderella’s father is so enamoured by his new wife and his new family that he allows his daughter to be treated as a servant in her own home. He ignores the fact she sleeps in the kitchen, is covered in ash, and has become less of a person. He never objects. He never tries to protect her. In fact, in older versions of the story, when the prince comes searching for his bride, it is Cinderella’s father who sends the prince away, telling him she’s deformed, before he destroys any evidence that connects her to the ball. Fathers do not always have their daughters’ best interests at heart.

the night. It was still early, but I could tell by David’s breathing that he was awake and already angry. He’d been livid for the entire two days I’d let my dad stay with us. I pretended to be asleep. I hoped David would just leave for work.

Perhaps he could tell from my breathing that I was lying to him?

Probably he never considered me at all.

His foot smashed into my back. Pain exploded up and down my spine. I cried out, then buried my face in my pillow, muffling my sobs and the shame of my marriage, letting the hiss of his angry words flow over me.

“Selfish bitch,” he said. “Stupid whore.” He stood up. “Worthless.” He closed the door.

I listened as he showered. Left for work. And only when he was gone did I hobble out of the bedroom, unable to stand properly, my back in spasm.

I didn’t have to tell my dad the truth.

I’d had plenty of practice making up excuses. Slipping in the bathtub was my go-to. But after three years of marriage, I’d finally realized that unless I figured out how to end it, I might not survive. So, instead of pretending, I told my dad what life was like for me. I told him about the rages, the abuse, David’s cycle of tears and apologies and pain. My dad listened. He was sympathetic. He was not surprised. He talked about my karmic contract, what past-life connections with David I’d carried into this life to resolve. We talked with detachment about how I might best extricate myself.

It’s February 1992, and I am twenty-one years old when I cram the suitcase into the back of my little silver Toyota Tercel and drive my dad to the Greyhound bus station. We’re early, so we go to the cafe across the street and order tea. I wrap my hands around the mug, absorbing its warmth, too rattled to drink.

Yesterday I told my dad the truth.

I’d been lying in bed, clinging to the edge, trying to take up the smallest possible amount of space, careful not to accidentally touch David while he slept during

And, a day later, I am sitting across from him in the coffee shop, bitter taste of cheap tea in my mouth, my hands gripped tightly around my cooling mug.

“I’m scared,” I say.

My dad reaches across the table and takes my hand in his.

“Remember,” he says. “We are never given more in our lives than we can cope with.” I know he believes this. I believed it then, too. I thought there was some kind of grand plan, some divine force keeping tally that would turn my life around when it got to be too much.

ALISON COLWELL // 18 ALISON COLWELL CONTENT WARNING:

violence

partner

I listened as he showered. Left for work. And only when he was gone did I hobble out of the bedroom, unable to stand properly, my back in spasm.

It’s time. He stands up. Wheels his suitcase across the street, and I trail behind. He boards the bus to head up island and back to my sister, and I stand on the tarmac and wave. Diesel exhaust billows as the engine roars and the bus pulls away, joins the stream of cars, all moving away from me. I stay there, rooted to the grey cement, until I lose sight of the bus. My father is gone for another year. There would be no help. No rescue. I am still married, still scared, and still unsure if I am going to make it out.

In “East of the Sun, West of the Moon,” an earlier version of the “Beauty and the Beast” fairy tale, the father agrees to trade his youngest daughter for wealth. When the Beast approaches her directly, she refuses to go with him.

“Give me a week,” says the father. And he spends the week convincing her to do the right thing. He wears her down. Eventually she agrees, and the father earns enough money off his youngest daughter to keep him and his other children comfortable for the rest of their lives. And she must live knowing that her life has a finite value. Her life is only worth so much.

Adecade has passed since that day at the bus station. But I still worry at the memory of that day, the same way my tongue returns to my broken tooth, exploring the shape, the sharp edge, over and over again.

I live on a different island now. With a new partner. I made it out. I built a different life. My dad still visits on his yearly vacation. On this day, we are hiking through the forest. The broadleaf maples fracture sunlight onto my skin, and my dog darts in and out of the salal bushes hunting squirrels. Ravens chortle in the high branches above us.

And hurt still eddies beneath my calm exterior. I want to cry: “How could you have left me with him?” But I’m a good daughter. So instead, I ask: “Do you remember that day when I was still with David and trying to figure out how to get away, and I told you what was happening, and you listened and you held my hand and then you boarded the bus and you left? I can’t stop thinking about that day. How could you leave me with him?”

“It was your choice,” he explains after a long pause. I glance at him quickly. He’s frowning, concentrating on getting his words right. I look away. “You were married. You’d been married for three years. It was what you wanted.”

“But that day I wanted to get out. I was asking you for help.”

“You didn’t though. Not exactly. And I thought you needed to figure it out for yourself. You wouldn’t have learned anything if I had just sorted it out for you.”

“But I might’ve died. Did you think about that?”

“Yes. It was hard. But you’d chosen to marry David because you had a lesson to learn. Maybe it was a lesson you could only learn if you died? I hoped you wouldn’t die. But it was more important that you do what you were meant to do. I prayed for you though.”

His New-Age answer infuriates me. I kick a stick off the trail. Stride faster, putting distance between us. Maybe I was meant to learn how to ask for help? Maybe I was meant to learn what being cared for felt like? Had I really not been clear about what I needed? The soft, wet scent of rainforest holds me, the scent of rot and decay and rich life. Breathe. Swallow my anger. I got out on my own, I remind myself. I didn’t need help. But that doesn’t stop the wanting, though, the desire to be considered worthy of saving.

When the thirteenth fairy curses Sleeping Beauty, her father acts. He orders all the spinning wheels in the castle to be burnt in an attempt to protect her. And when that fails and the curse comes to pass, he asks a fairy to enchant his entire castle, putting everyone to sleep so she is not alone. His grief is huge. In “Sleeping Beauty,” the father does everything he can to protect his daughter. Ultimately, he fails. But there is joy in the fact that he tried.

Fifteen years further on and I have my own kids. Being a parent opened a deep well of terror and love inside my heart. I can be ferocious if I think someone is hurting my child. Like a dog circling a worn blanket, trying to find the right spot to settle, I’m still trying to find the place I can rest with the choice my father made, find a way to forgive him for not being the dad I desperately wanted. I have to let it go. My kids need a grandfather. Forgiveness is tricky. It’s something we do for ourselves rather than others. I need to let go of the hurt I feel when I remember how he boarded that bus and left me. Let go of the anger that he didn’t take me with him. I need to forgive myself for not knowing better when I got married. I need to forgive myself for not getting out sooner. I’m flawed too. Each day I try to do my best as a parent. But I mess up. I make mistakes. He thought he was doing the right thing. But I wanted a father like Sleeping Beauty’s, a father who would burn the world to protect his daughter. Yet that’s not the kind of father I had. It’s not the kind of father most of the daughters in the stories had. Our fathers are human. Our fathers are imperfect. No woodcutter is going to storm into our lives, axe held high, ready to take out the wolf. We have to wield our own axes. We have to take charge of our own stories.

ALISON COLWELL // 19

///

THREE POEMS

FOR ONCE

For once,

All the clocks ceased to tick

The buses refused to come to the station

The subway shut down indefinitely

Tracks shrugged off their trains

Babies opened their mouths but tears eluded them

Planes dropped like dead flies from the sky

Cars shrieked to a stop on asphalt

Drivers got out and walked into the confused ocean

Tenants leapt from apartment windows

The sun closed heavy lids on its eye

The moon abandoned the night Stars denied their shine Wind collapsed into nothing For once,

The scream of your pain stopped the world As one, the universe looked upon your pain And was blinded

BLESSING O. NWODO // 20 BLESSING O. NWODO

SWALLOWING THE HEART’S KNOT

The word baby refuses to form on my lips. If it was a single word like babe, I think I might manage to let it out. No, babe evokes my girlfriends or a baby in swaddling clothes. It’s easy to say, I tell myself. It’s just bay-bee, like bay—the sea’s inlet—and bee—a buzzing insect. Combine it, baybee—a buzzing insect by the sea’s inlet. I can say baby when passion is reduced to the sensation of blood pumping in my veins. I can say baby because I don’t have to put it through the thought checkpoints in my mind, I just let it slip out, baby.

But when my phone rings amidst the thousand eyes of the public, the endearment shrinks, this stifling of emotion increases, the words are in my stomach as the name flashes on my screen, I pick it up and the word is in my chest beating along with my heart, I say hello in a dispassionate voice so no one knows that someone special is calling, someone whose tongue has been in my mouth, we finish the conversation, and baby travels to my mouth, debating with my teeth and tongue to form the words that my mind has already said over and over again, baby is out of my mouth in a whisper when the call ends and can no longer be heard.

ANI RISING

There is a woman on fire presiding in the place where even time and gravity daren’t exist Everywhere

Her feet tread

Is set ablaze

And She is bringing that raging furious damnation upon the heads of men pretending to be gods deciding who lives or dies ///

BLESSING O. NWODO // 21

NOCTURNAL BOTANICAL ONTARIO, (JUNE 18, MOTH ASSORTMENT OF SEEDS, FLOWERS, LEAVES), 34” x 47”, 2020 | SARA ANGELUCCI

Image courtesy of the artist the Stephen Bulger Gallery.

NOCTURNAL BOTANICAL ONTARIO, (JUNE 18, MOTH ASSORTMENT OF SEEDS, FLOWERS, LEAVES), 34” x 47”, 2020 | SARA ANGELUCCI

Image courtesy of the artist the Stephen Bulger Gallery.

MORGAN DICK

CONTENT WARNING: plane crashes, 9/11, violence, and war

AUTOPILOT MALFUNCTION

At 0:03, the camera zooms on a man standing in the middle of a city sidewalk. At 0:04, he lifts his baseball cap and glances overhead. The camera swivels upward, following an airplane across the blue sky—it really is so, so blue—and toward the shimmering bulk of a nearby office tower. Fire blooms from the side of the building. The camera shakes. The person holding it cries out.

The video doesn’t show it, but many lives have just ended. Hundreds, probably. Max can’t help but go back a few frames in search of the tiny people in the pixels. He doesn’t find them, but he knows they’re there.

A news montage rolls from 0:24 to 1:22. Grey plumes on black-and-white vertical stripes. A single helicopter at the edge of the frame. Was this purely an accident, one anchor asks, or could this have been an intentional act? The second plane hits at 1:45. For some reason, Max still expects it to burst out the other side in one piece.

In the next shot, people lean from broken windows on the upper floors. Small and smudgy figures flail their arms and wave the white flags they’ve improvised from what appear to be tablecloths and dress shirts.

“Dude. Come on or we’ll be late.”

Max glances up from his phone.

Danny stands at attention, backpack on, chest strap buckled, as if his destination were a mountaintop and not third period phys-ed. “You know what Weiss is like.”

The school cafeteria has emptied, the tables scattered with debris: half-crushed cans of Monster, twisted candy wrappers, plastic trays spattered with ketchup and mayonnaise.

Max returns to his phone. He has a little more time.

Danny finds Max’s backpack on the floor and starts packing his stuff for him. Max, it should be noted, did not ask him to do this.

“Why do you watch that shit anyway?”

“You stream stuff from Ukraine,” Max says. The guys in their grade all live for those videos—the volleys of gunfire, the women screaming, the bodies lying facedown in dirt. Or they trawl Reddit for clips of people accidentally dismembering themselves with fireworks. But somehow Max is the depraved one?

“Your shit is creepier,” Danny says.

“Why?” Max makes a point of never listening to the 911 calls, though there are dozens of them on YouTube. He does read the transcripts sometimes.

“I don’t know.” Danny pulls Max to his feet. Easy to forget he’s got some muscle under all that dough. “But it definitely is.”

By the time they get their gym kit on and make it out on the field, the rest of the class has already split into teams.

Mr. Weiss greets them with a grin, clipboard under one arm: a menacing posture. “Tuttle! Cruz! I was starting to think you were dead.”

“We’re sorry, Mr. Weiss,” Danny sputters. The short run from the change room has left him breathless. Max doesn’t organize his friends into tiers because to do so would be highly douchey. But if he were to mentally stratify his friendships, Danny would fit somewhere along the second or third rung. He isn’t particularly funny or even fun. When they met in Science 10 last year, Max hadn’t looked at Danny and thought, That kid’s cool, I want to hang out with him Max hadn’t thought anything at all.

Weiss points to the far end of the field, a plain of gummy brown turf. “Laps.”

Danny’s eyebrows soar. “But Mr. W—”

“Laps.”

The other kids snicker.

Max searches the crowd for Cayden Smithwick, a top-tier friend he’s known since kindergarten. Cayden won’t return his gaze. None of them will.

MORGAN DICK // 23

“I don’t know why I wait for you all the time,” Danny says as he’s jogging away.

of the North Tower, how patrons could see the whole Manhattan skyline while they ate, how the restaurant lost seventy-two employees that day, not counting the security guard or the six contractors who were there working on the new wine cellar.

“Don’t be pissed,” Max says.

Danny reaches into the plastic jug of steaming vinegar water and pulls out another handful of forks to polish.

Max tries again: “It was one class.”

Danny scrubs each fork with a folded coffee filter until the tines gleam, then chucks them all in the grey bin on the counter.

They’ve been huddling in the boggy warmth of the restaurant kitchen since their shift started twenty minutes ago, two busboys in matching red polo shirts. A whole rack of cutlery later, Danny still has not uttered a word. It’s slightly overkill.

In the back, one of the line cooks calls, “Service, please.”

Danny tosses his coffee filter aside and goes to collect the food from the window.

He has a good life, Danny—a normal life. A life completely undefined by random tragedies like autopilot malfunction and control system failure. Danny’s mom doesn’t lie in bed crying all day. Danny’s dad doesn’t sit around crushing beers all night. Danny’s sister isn’t—Danny’s sister isn’t—

Max sunders the thought, queues up a video, and props his phone against the cutlery rack so he can watch and polish at the same time.

A few seconds later, his boss presses through the swinging door and booms, “Maximus Decimus Meridius! How art thou?”

Max scrambles to hide his phone. Maybe Evgeni didn’t see it yet?

“It’s okay, man,” Evgeni says with a laugh. “Polishing is boring, I get it.” He retrieves a porcelain teapot from the shelf overhead and starts filling it with hot water from the spout on the coffee machine. “What are you watching?”

“Windows on the World,” Max says.

“Never heard of it.”

Evgeni has always struck Max as vaguely damaged. Something about the big silver rings he wears on his thumbs and the fuzzy grey tattoos that poke out from under his sleeves. He might, Max thinks, actually understand.

Max replaces his phone and hits the play button. “It was a restaurant at the top of the World Trade Center.”

“Oh. Weird.”

Before Max can help himself, he’s telling Evgeni everything—how Windows took up the top two floors

“Cantor Fitzgerald lost 658,” Max adds, for context. Water overflows from Evgeni’s teapot, gliding down the sides and over his knuckles. “Shit!” He thunks it down and shakes out his hand, wincing. “658 what?”

“Employees. Of the company.” Does Max have to spell it out for him? “Big investment firm, Floors 101 to 105, no survivors.”

Evgeni presses his lips into a thin line. His eyebrows draw down and together, as if a seam has tightened at the centre of his face. It is the look of a person thinking very carefully.

“You know a plane isn’t gonna crash into our restaurant, right?”

Max seizes another handful of cutlery from the jug. His nose stings from the tang of vinegar in the air. “I’m not stupid.”

“I mean, it makes sense that you would find that stuff …” Evgeni’s eyes flicker back to the phone, to the digitized camcorder footage of restaurant-goers in suits, servers in white jackets, high windows, a dusky horizon, “… interesting. Given what happened, I mean.”

Interesting isn’t the half of it. But Max can’t find the right words. “Everyone remembers where they were that day.”

“Except you. You weren’t born yet.”

Danny breezes through the swinging door with an armful of dirty plates and begins scraping mashed potatoes and green beans into the giant garbage bin beside the dish pit.

“I’ve been meaning to ask, kid,” Evgeni says. “How’s your family doing?”

“They’re fine.” A speck on this one fork won’t come off no matter how hard Max rubs it. Must be dried food or something.

“You know you didn’t have to come straight back to work, right? Like, I would’ve held your job for you.”

Max throws aside his coffee filter and attacks the speck with a thumbnail instead.

“Four months isn’t a long time, you know, when it comes to grief.”

The bit of dried food wedges up under Max’s nail with a tiny dart of pain.

Evgeni won’t stop talking, his voice a murmur and a jet engine: “I can’t imagine how you must—”

“Max, can you show me the new place where the saltshakers go?” Danny. He shores up before them with arms akimbo, another of his Boy Scout poses.

MORGAN DICK // 24

///

“The saltshakers?” Max says.

“Debbie found a new spot for them, didn’t she?”

“Oh. Yeah.” Max adds the fork to the cutlery bin and rubs his hands on his pants. “Yeah, I’ll show you.”

Evgeni glances between the boys, licking the fronts of his teeth. “All right. I’ll let you kids get to work.” He slides the teapot onto a plate beside a packet of orange pekoe and disappears into the dining room.

There’s something funny about the way Danny looks at Max.

“The saltshakers go next to—”

“I know where they go.” Danny shakes his head. “Obviously, I know where they go.”

Max still isn’t quite sure what his problem is.

“We got a recommendation for a therapist, a really good one.” Whatever Mom sees in his face, it leads her to lick her lips and add, “For you.”

Heat pools in Max’s chest. This is too much— Mom’s bedhead, Dad’s beer stench. Their raging hypocrisy. “Why me?”

“To process everything you’re feeling.”

“But why do I have to process it? Neither of you are.”

“I’ve started going for walks,” Mom says, which is hilarious.

“You walk to the end of the driveway, light a cigarette, and walk back.”

Dad catches a burp in his fist. At least he isn’t bullshitting.

“We need to take care of you,” Mom says. “You’re all … you’re all we …”

The next night, a knock arrives on Max’s door while he sits in bed in his boxers chomping down the last of his dinner waffles.

“Yeah?” he says.

The door creaks open, and there they stand, shoulderto-shoulder, faces shabby and grey, eyes at once puffy and hollowed out. Exactly like last time.

Max sits up straight. The dinner plate slides off his knees and scatters crumbs all over the bedspread, but what does that matter? “What’s happened?”

“Nothing, nothing. We only want to talk.” Mom sinks onto the edge of the mattress.

Dad lingers in the doorway, expressionless, hands thrust deep in the pockets of his jeans. Hard to believe these are the same people Max used to catch twostepping to Keith Urban in the kitchen, all smiles and sloppy kisses.

Mom smooths her skirt flat over her lap. The fabric is so full of wine and coffee stains it almost looks like that’s the design. “We’re worried about you.”

Max doesn’t buy it. His parents don’t have the emotional real estate to worry about him. These days, they don’t think of him at all.

“We’ve heard from a couple of your teachers lately.”

“About?” Max’s grades are fine. Max’s everything is fine.

“The videos you’ve been watching,” Mom says.

Max crushes a corner of waffle in his fist. “It’s … it’s history.”

“Your boss called us, too,” Mom says.

Max imagines Evgeni’s panicked voice on the phone. He knows which stairwells were blocked and how many people were trapped above the impact zones. He knows exactly how many firefighters died. That’s right— the exact number. I fact-checked him.

Max eyes the wall behind his dresser. If you blasted through the layers of paint and wood and fibreglass, you’d find Lib’s room back there, her bed half-made,

her closet teeming with the leather pants and weird leotards she spent zillions of dollars on. Everything exactly as she left it that day in January when she boarded a faulty Boeing bound for an exchange program in Switzerland.

“Why 9/11?”

This is the first thing Dad has said to Max in days. Weeks, maybe.

“Why 9/11,” Max repeats, to buy time. “Why 9/11 …”

Because that day was a threshold between two realities? he thinks. Because everything had changed, yes, but it had only just changed. For those few hours between 8:00 and 11:00 a.m., the old world was still near enough to see, to smell, to wave at.

Max shrugs. “The geopolitical consequences.”

He can tell from the way their mouths bunch and twist that this answer doesn’t satisfy them.

“She wouldn’t have felt any pain.” Mom says this all the time—to cousins, to neighbours, to herself in the mirror when she thinks no one’s looking.

MORGAN DICK // 25

///

He has a good life, Danny—a normal life. A life completely undefined by random tragedies like autopilot malfunction and control system failure.

Dad coughs.

Max rises from bed, finds some pants on the floor. “She would’ve been afraid.”

Dad coughs again.

“The appointment is at four o’clock next Tuesday,” Mom says. “Max? Did you hear me? Max, where are you going?”

He doesn’t know. Somewhere. Anywhere. “To meet a friend.”

“It’s a school night,” Mom says, blah blah blah, something, something. Max is past listening.

“I talk about basketball all the time, Max.”

Filling with an urge to get rid of the ball, Max squares up his feet, bends his knees, and takes a jump shot. The ball dings off the rim and goes clattering into a row of garbage bins between Danny’s house and the next.

Neither boy retrieves it.

“You’re too far away,” Danny says.

“I was trying for a three-pointer.” Everything has started fuzzing together—the hoop, the house. Max rubs his eyes. He must be tired.

“No—like … you. You’re far away. Lost in your head all the time.”

He isn’t sure where he’s headed until Danny comes into view. It’s a strange sight, Danny out on the driveway all alone, dribbling a basketball back and forth between his legs. Not that he isn’t tall enough. Danny’s always been more of a D & D kid is the thing.

“Hey,” Max calls.

Danny doesn’t look surprised to see him. “Hey.”

“Since when do you shoot hoops?”

Danny tucks the ball under one arm and scratches his nape the way he always does when mildly embarrassed. “I don’t know.”

“What do you mean, you don’t know?”

“I might try out for the junior team.”

“For real?”

“Haven’t decided.”