OWEN SCHALK, LYNDA WILLIAMS, RAYYAN KAMAL

// winners of the biennial Emerging Writers Fiction Contest //

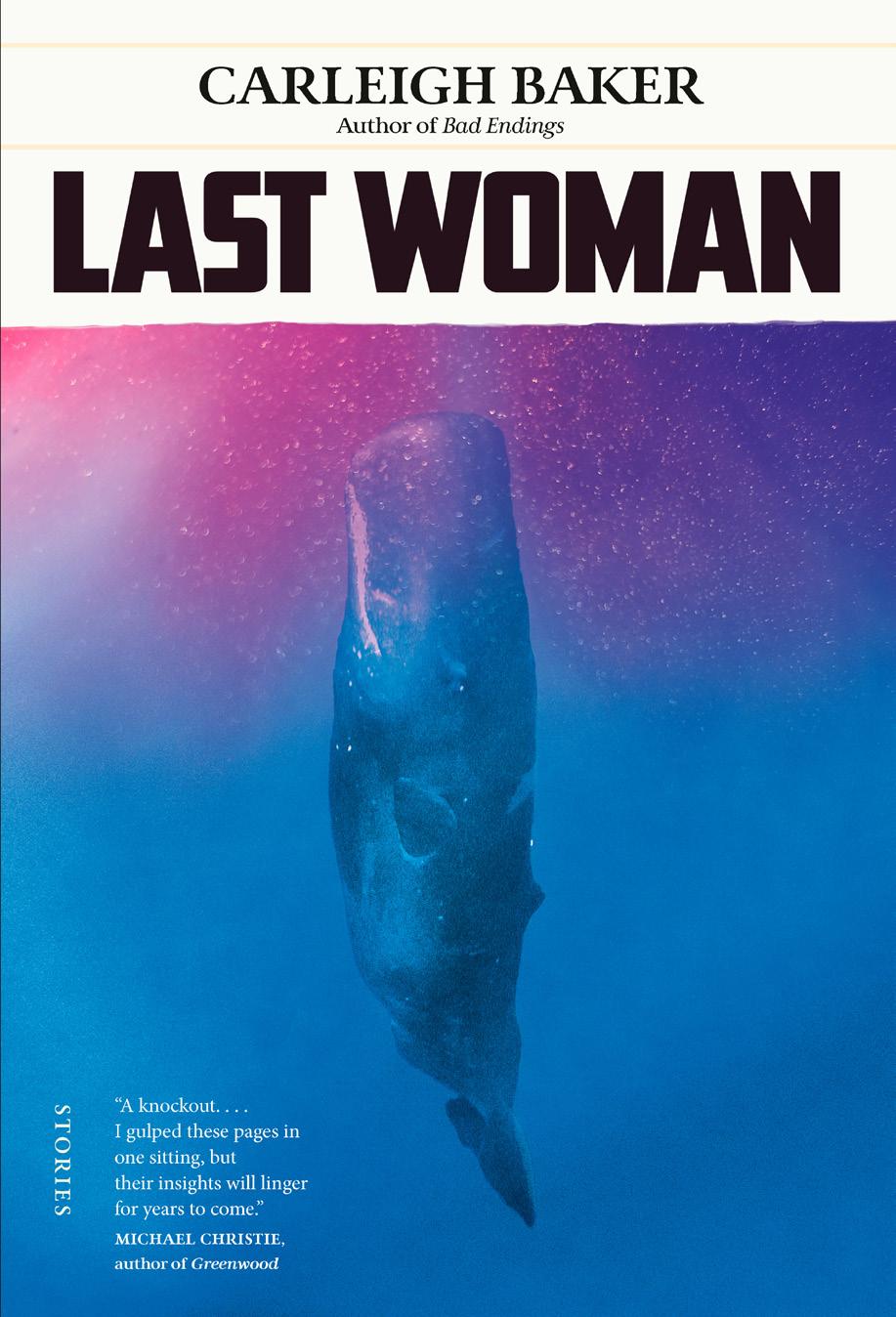

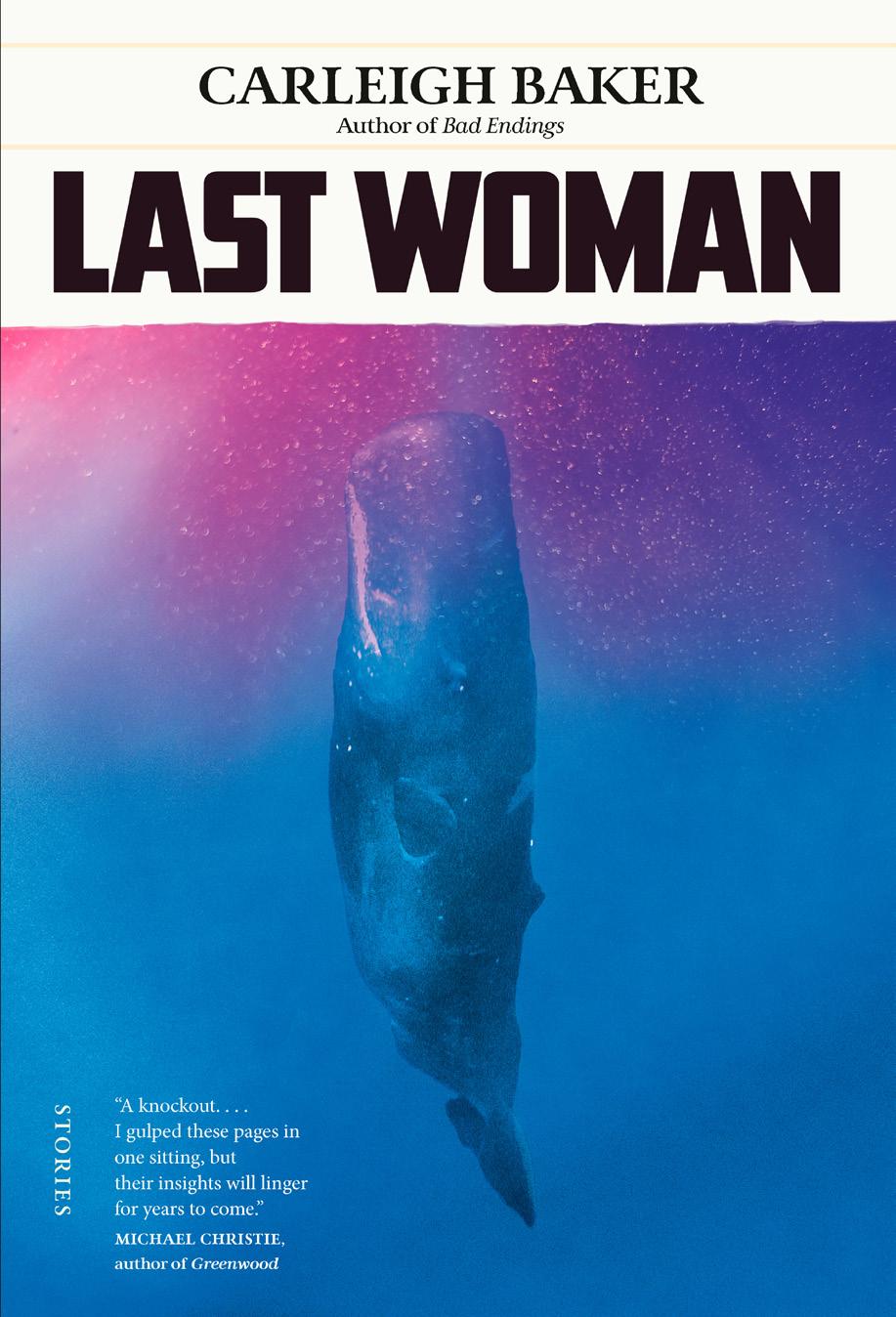

CARLEIGH BAKER // interview

ROB WINGER & VIVIAN LI // poetry

SHANE NEILSON & AGA MAKSIMOWSKA // creative nonfiction

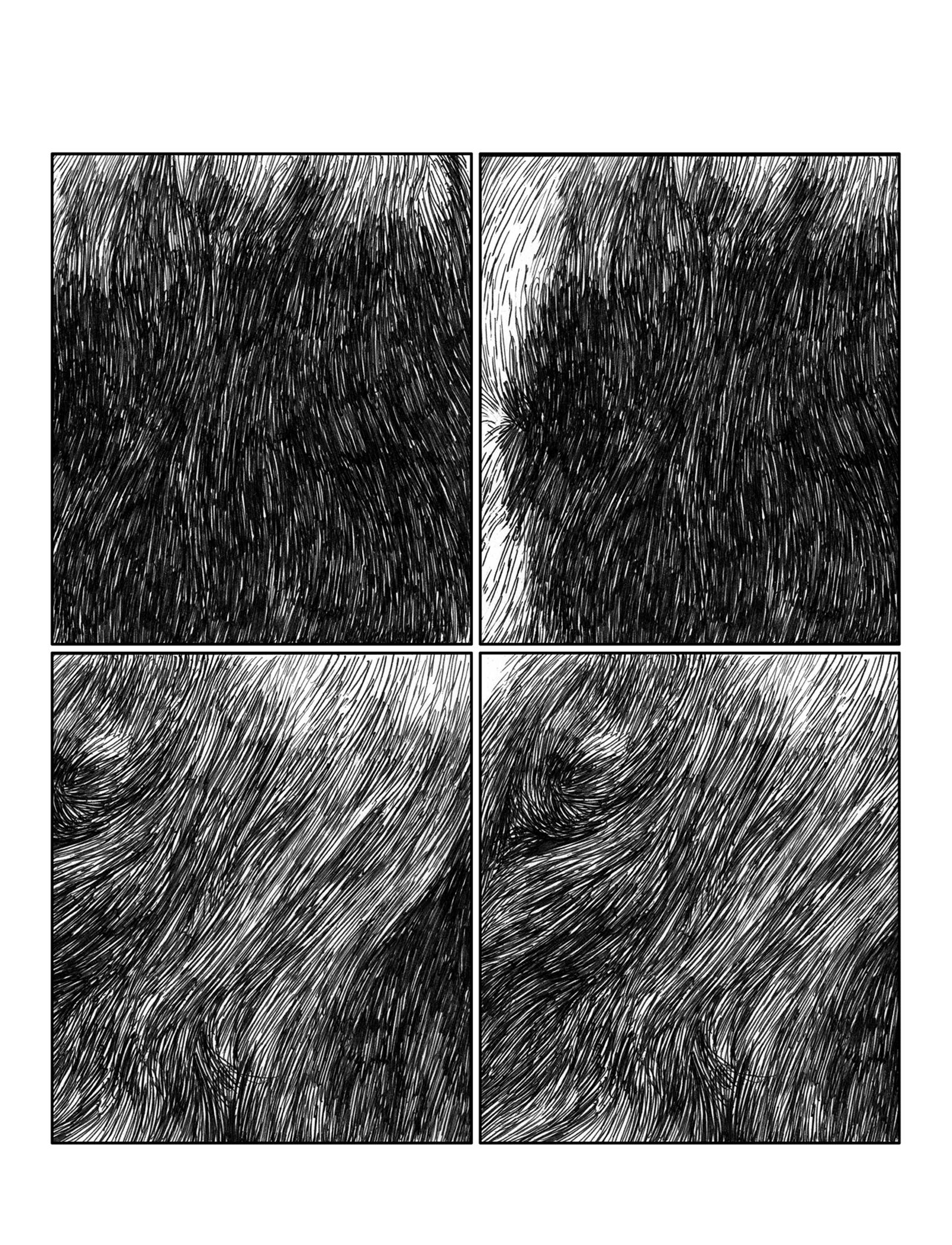

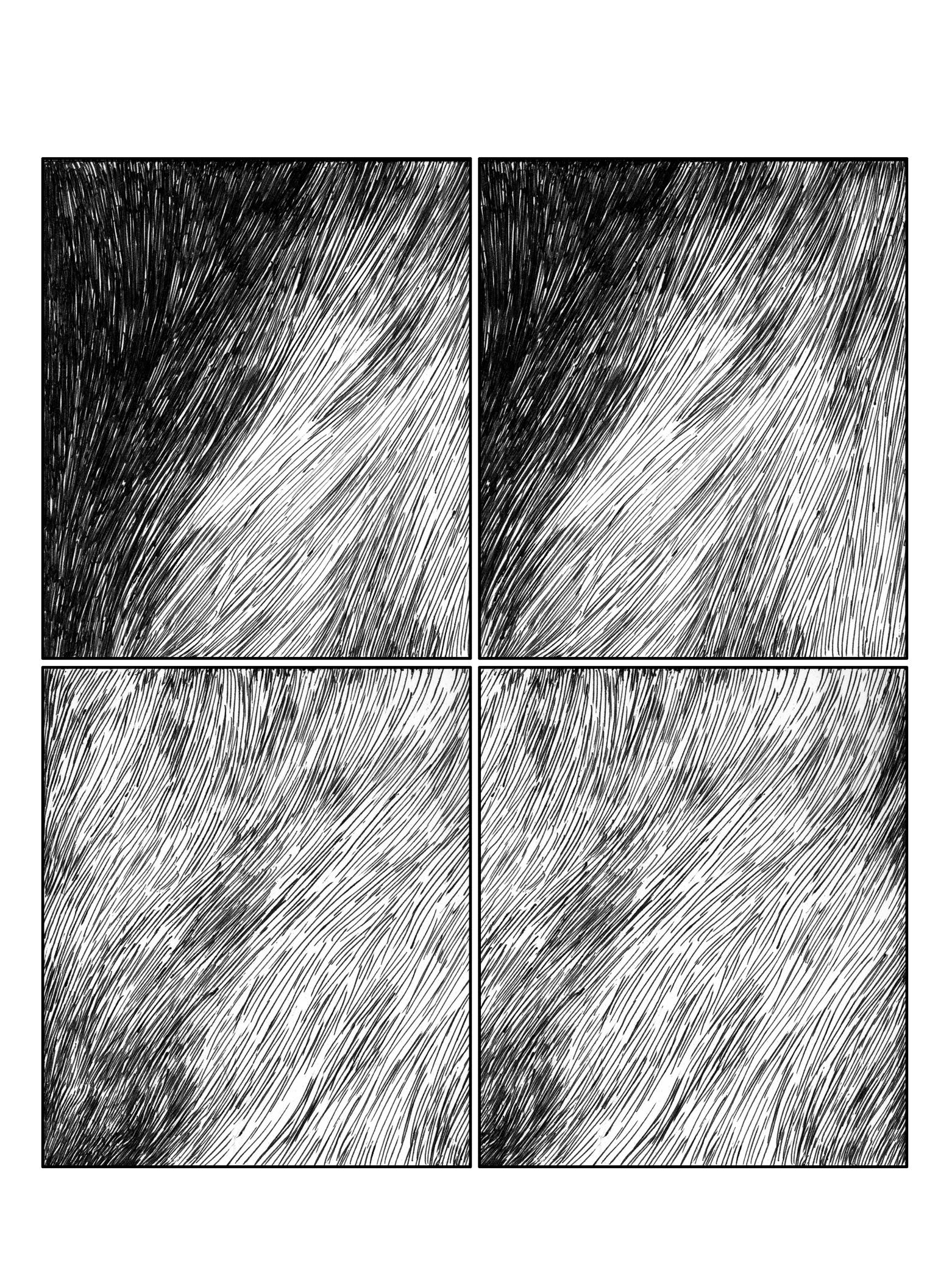

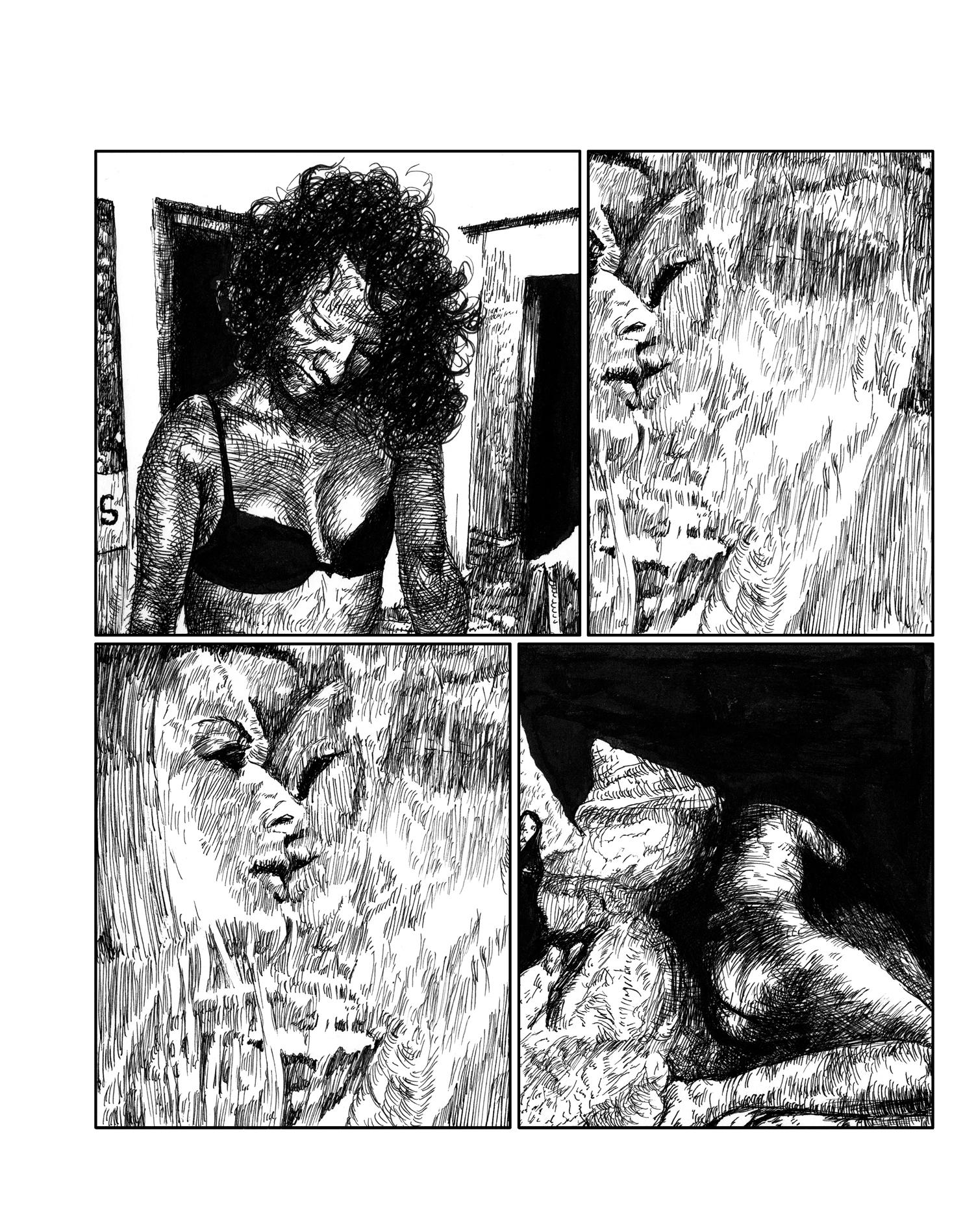

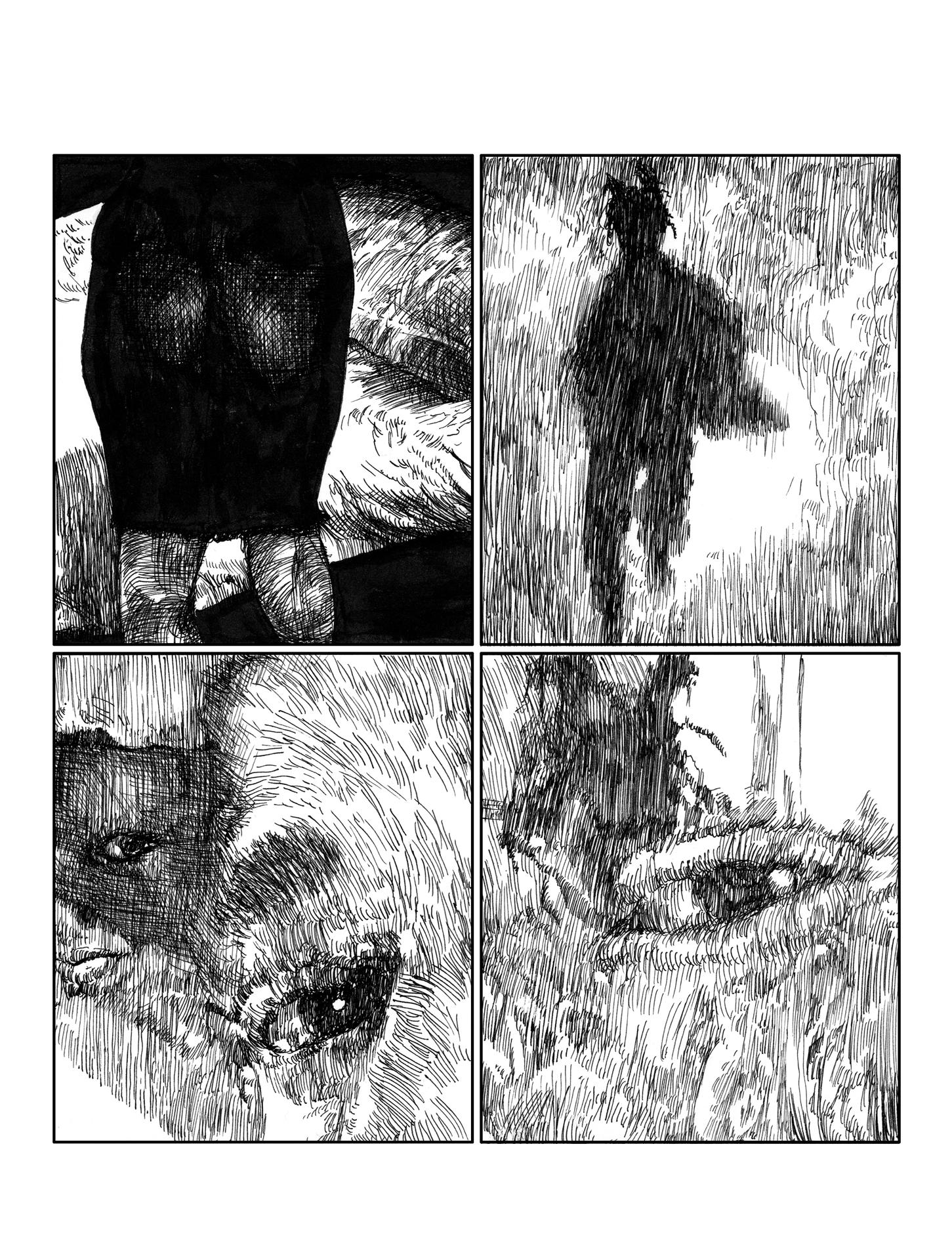

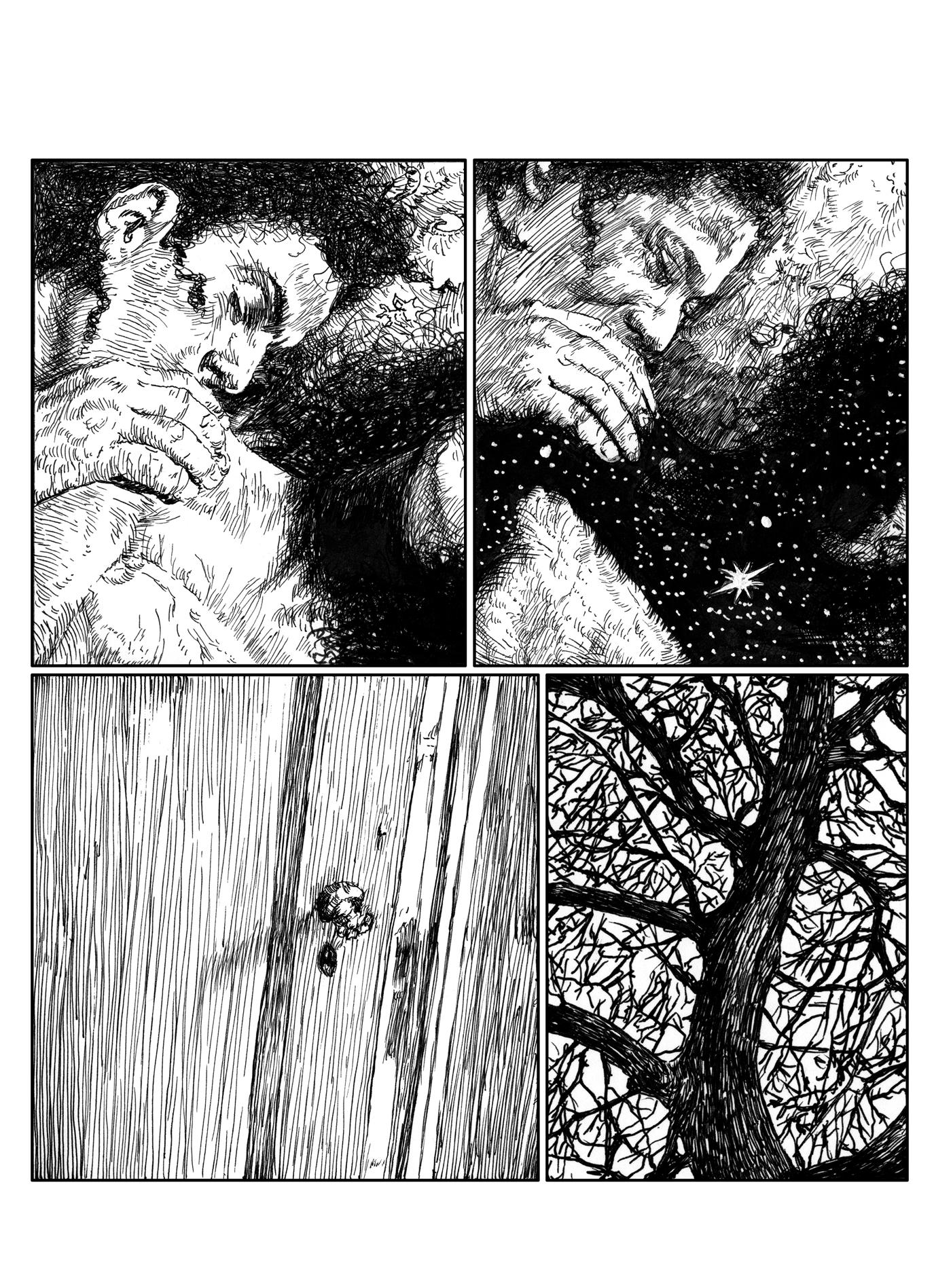

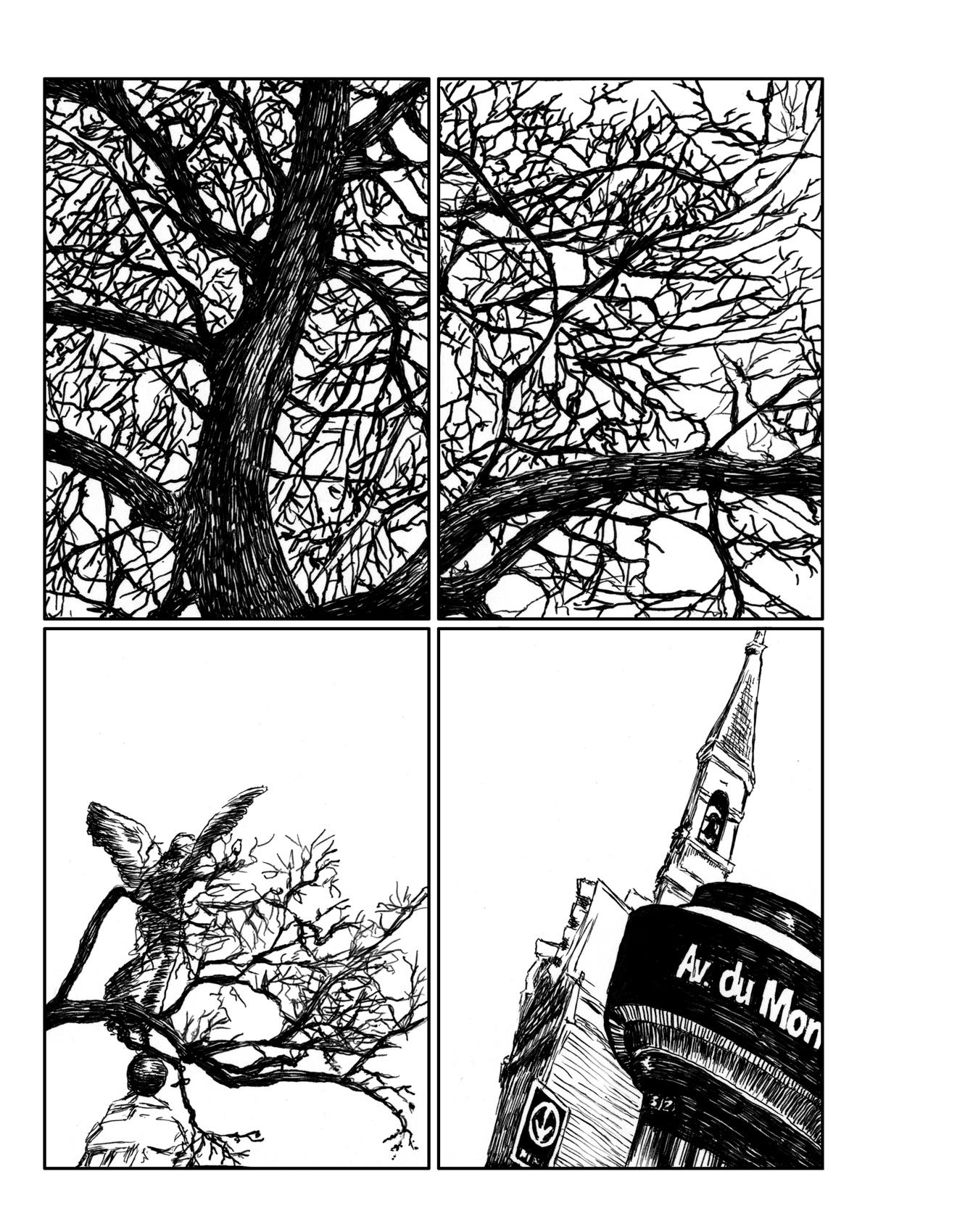

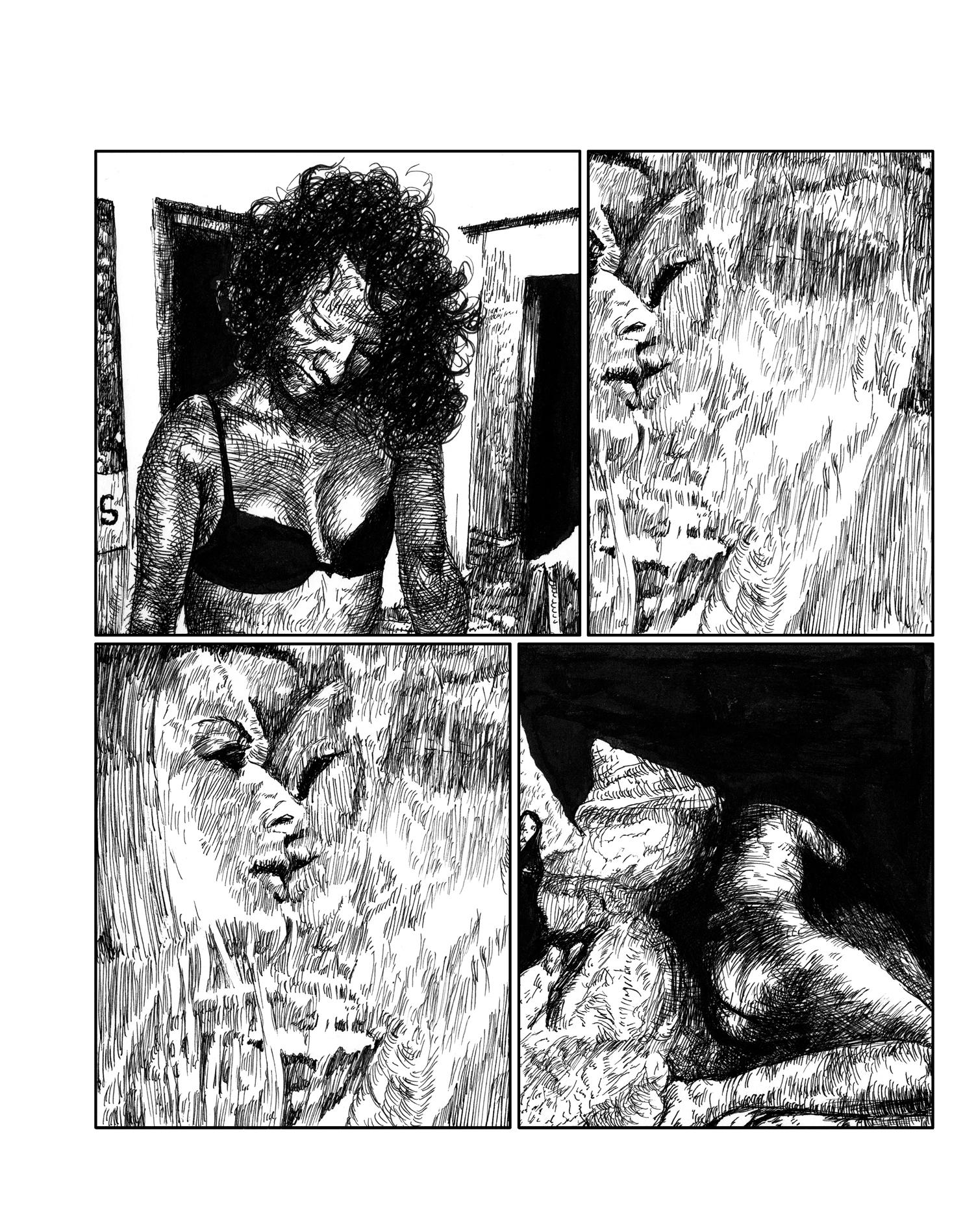

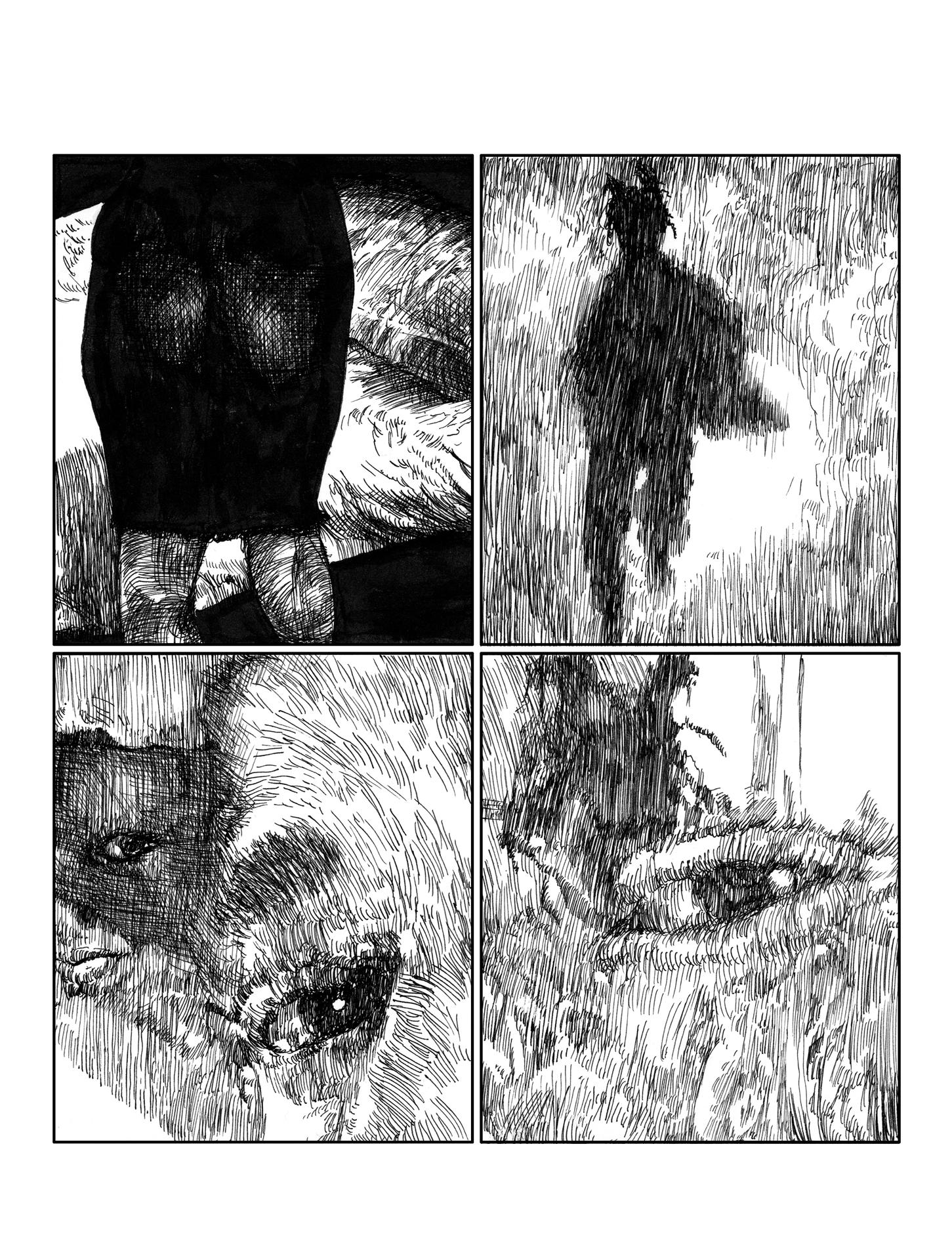

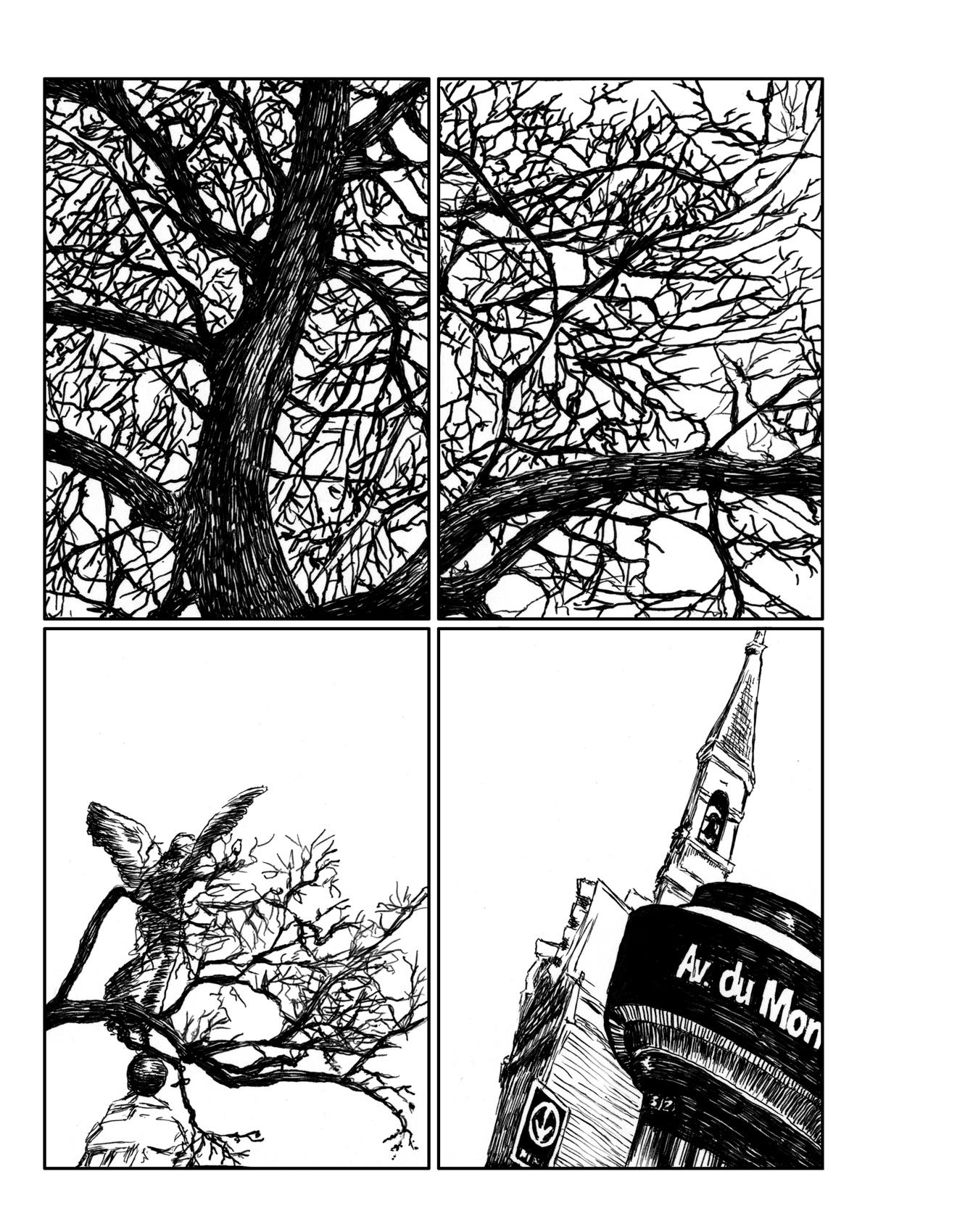

STANLEY WANY // comic

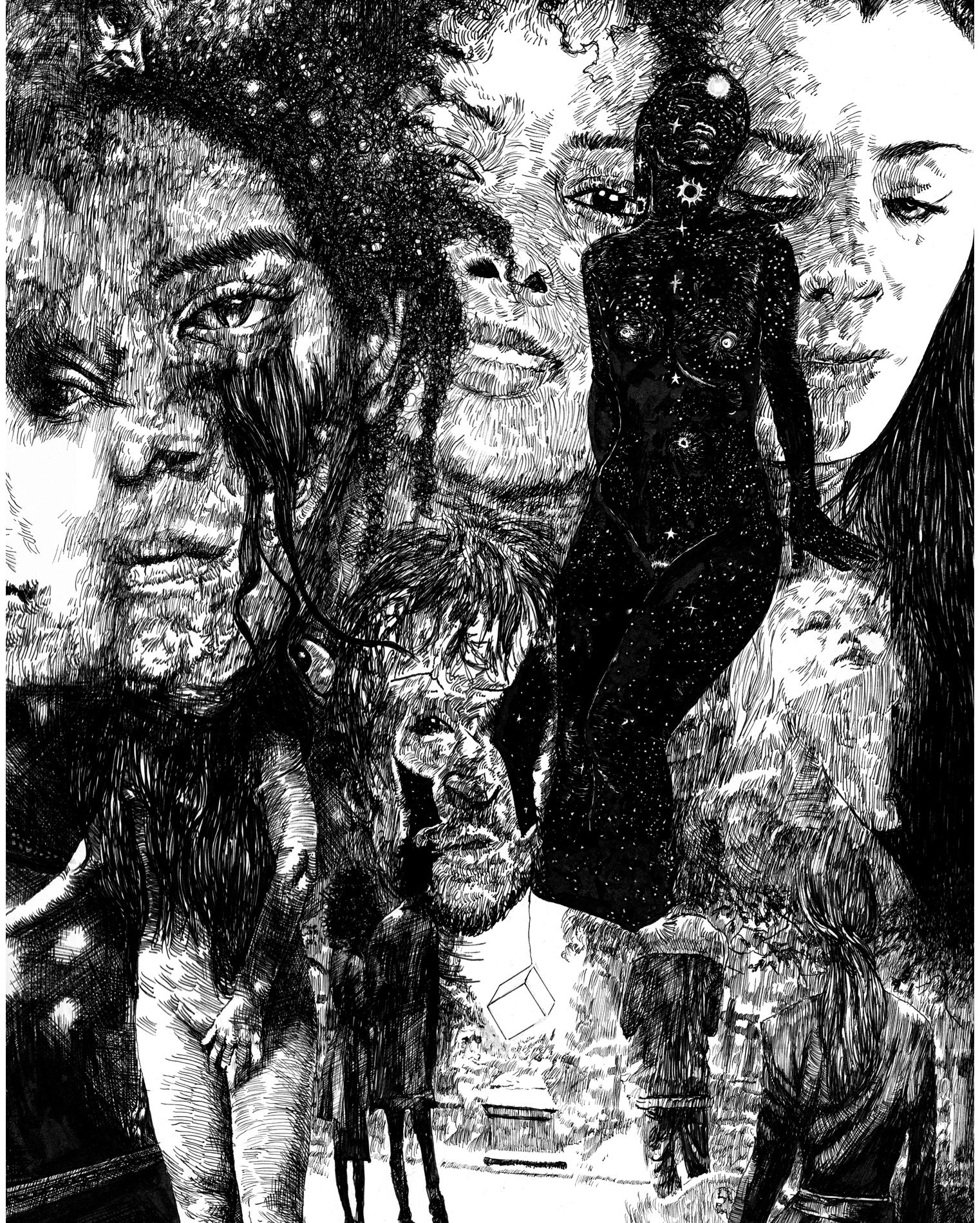

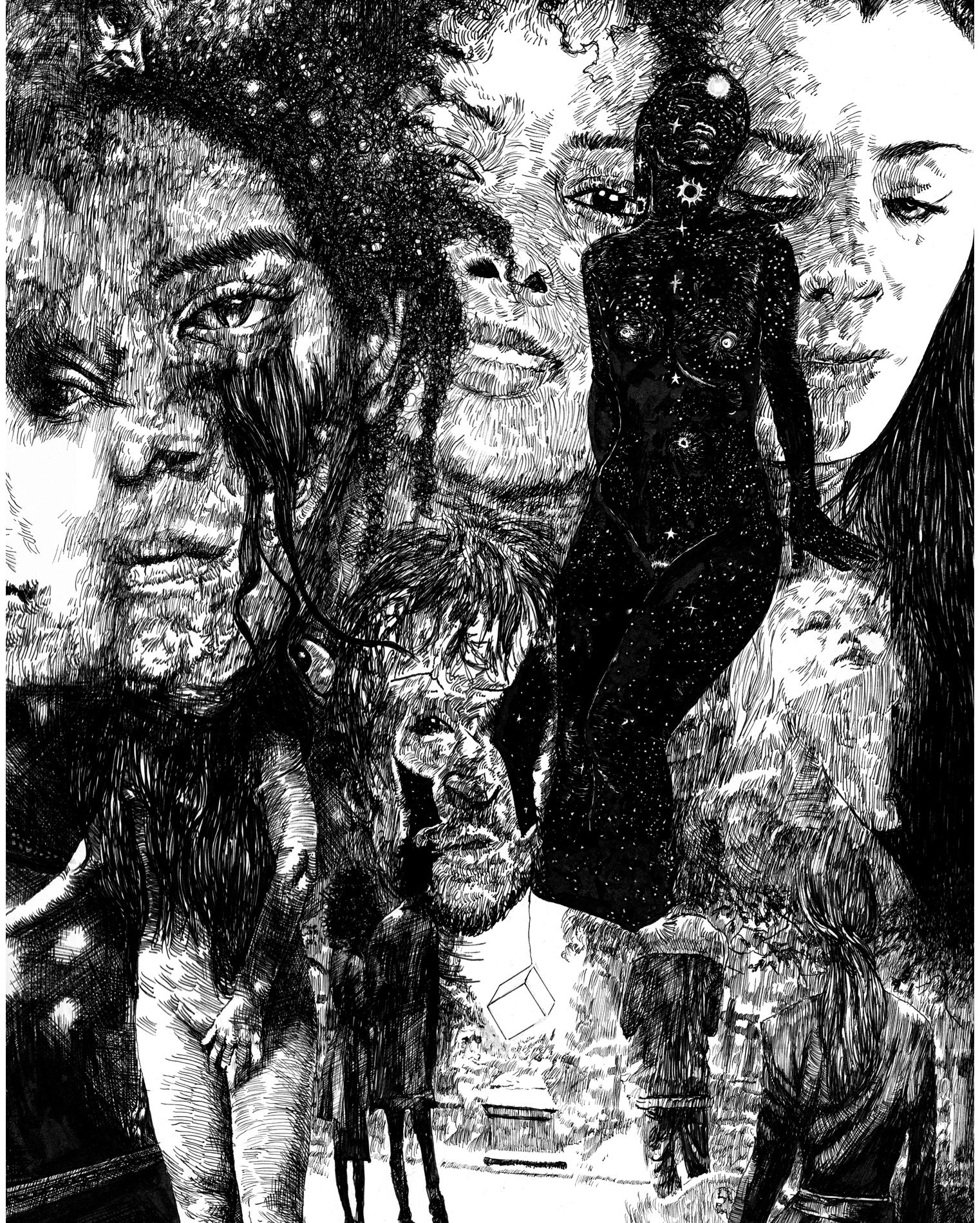

STEVEN BECKLY // art

spring

$9.95

VOLUME 12 ISSUE 1

+ summer 2024

Where creativity meets career.

Creative Writing Online Program

Looking for personalized feedback on your manuscript? Our 28-week online studio program is customized to address the needs of your book-length project. Work from the comfort of home under the guidance of our exceptional faculty.

Program starts every September and Januaryapply now!

There is a story to be told here. humberschoolforwriters.ca

CONTENTS

FROM THE EDITORS 3

// FICTION

OWEN SCHALK 5 Speaking in Regrets

LYNDA WILLIAMS 17 Berman

RAYYAN KAMAL 29 A Son’s Confession

AMARA DHAL 32 Mark of the Soucouyant

GARRET DWYER JOYCE 44 Extra Gang

SCOTT JOHNSON 54 The Deadliners

// POETRY

ROB WINGER 9 [Three Poems]

SHAUNA ANDREWS 21 [Two Poems]

VIVIAN LI 34 [Two Poems]

AARON RABINOWITZ 48 [Three Poems]

// CREATIVE NONFICTION

AGA MAKSIMOWSKA 12 Monocultures: an Essay on Tender Is the Flesh and Single-Sex Education

SHANE NEILSON 24 Blurring the Borderline

LEA ARMATA 51 My Nonno

// COMICS

STANLEY WANY 36 excerpt from Helem

INTERVIEWS // REVIEWS

CARLEIGH BAKER 57 [Interview]

REVIEWS 64 TOWARD AN ANTI-RACIST POETICS THE KING OF TERRORS MY EFFIN’ LIFE ELEMENTARY PARTICLES

CONTRIBUTORS 70

STEVEN BECKLY 72 [Featured Artist]

VOLUME 12 ISSUE 1 spring + summer 2024

MASTHEAD

PUBLISHER

Patrice Esson

EDITORS

Eufemia Fantetti

D.D. Miller

FICTION EDITORS

Sarah Feldbloom

Kelly Harness

Matthew Harris

Alyson Renaldo

CREATIVE NONFICTION EDITOR

Leanne Milech

POETRY EDITOR

Meaghan Strimas

REVIEWS EDITOR

Angelo Muredda

ART/ILLUSTRATIONS EDITOR

Cole Swanson

COMICS EDITOR

Christian Leveille

COPY EDITORS

Eufemia Fantetti

Claire Majors

D.D. Miller

PROOFREADER

Claire Majors

DESIGNER

Kilby Smith-McGregor

ADVISORY

Vera Beletzan

Senior Dean, Faculty of Liberal Arts & Sciences and Innovative Learning, Humber College

Bronwyn Drainie

Former Editor-in-Chief of the Literary Review of Canada ; author

Alison Jones

Publisher, Quill & Quire

Joe Kertes

Dean Emeritus, Humber School of Creative and Performing Arts; author

Antanas Sileika

Former Director, Humber School for Writers; author

Nathan Whitlock

Program Coordinator, Creative Book Publishing Program; author

Humber Literary Review, Volume 12 Issue 1

Copyright © May 2024 Humber Literary Review

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without prior written permission.

All copyright for the material included in Humber Literary Review remains with the contributors, and any requests for permission to reprint their work should be referred to them.

Humber Literary Review

c/o The Department of English Humber College Institute of Technology and Advanced Learning 205 Humber College Blvd. Toronto, ON M9W 5L7 humberliteraryreview.com

Literary Magazine. ISSN 2292-7271

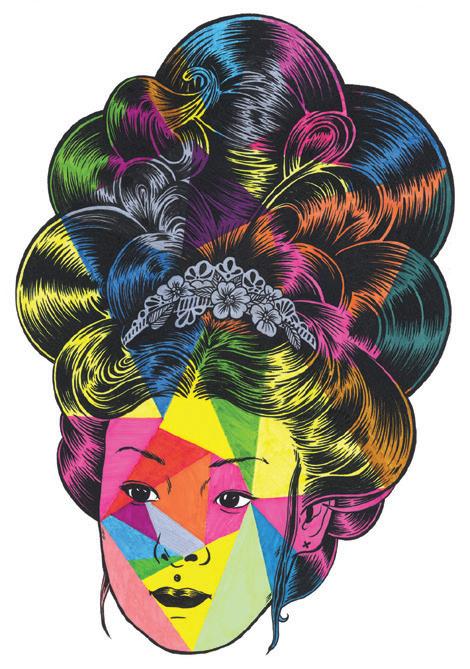

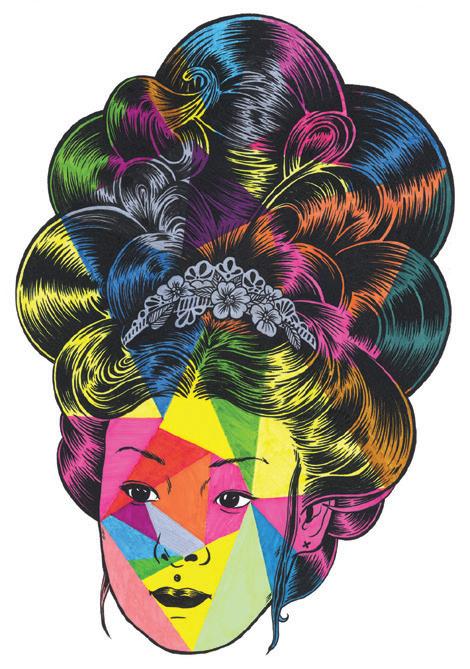

Layout and Design by Kilby Smith-McGregor Cover Image and Portfolio by Steven Beckly

Humber Literary Review is a product of the Humber College Institute of Technology and Advanced Learning’s Department of English

Printed and bound in Canada by Paper Sparrow Printing on FSC-certified paper

Opinions and statements in the publication attributed to named authors do not necessarily reflect the policy of the Humber College Institute of Technology and Advanced Learning or its Department of English.

FRONT COVER | STEVEN BECKLY AMMOPHILA, 2018 Image courtesy of the artist.

FROM THE EDITORS

SOMEHOW, IT’S BEEN TEN YEARS SINCE THE RELEASE OF THE FIRST ISSUE OF THE HUMBER LITERARY REVIEW On May 14, 2014, at the Gladstone Hotel in Toronto, this literary journal came into being. In her editor’s note, then editor-in-chief Wendy Phillips wrote, “In our pages you’ll discover an eclectic array of short fiction, poetry, essays, and reviews from a broad spectrum of talent.” She spoke about the hope to feature interviews with established writers and our unique goal of showcasing an artist in each issue. All of this still holds true. In that first issue, we featured both established and emerging writers: the late Priscila Uppal shared with us a brilliant short story; Jeff Latosik, whose debut poetry collection had just won the Trillium Award, published two poems; and that issue also featured an interview with the late writer and renowned Humber professor Wayson Choy. There were also poems, fiction, and essays from emerging writers, including poetry from Amber McMillan, who has since gone on to publish two books of poetry, a collection of short stories, and a celebrated memoir.

This template of featuring established writers alongside those just emerging has been one we’ve maintained over the past decade. We’ve been pleased to publish celebrated writers like Russell Smith, Karen Solie, Douglas Coupland, and Catherine Graham alongside writers just on the verge of breaking out like Billy-Ray Belcourt, Cherie Dimaline, Naben Ruthnum, and Souvankham Thammavongsa. In our pages, you’ve read interviews with some of the great writers of our time—like Emma Donoghue, Ann-Marie MacDonald,

Eden Robinson, Waubgeshig Rice, Patrick deWitt, and Casey Plett—and had the pleasure of gazing upon the artwork of Kent Monkman, Kim Dorland, Braxton Garneau, Howie Tsui, and Joan Butterfield. And this barely scratches the surface of the excellence in art and writing we’ve had the pleasure of featuring over the years, to say nothing of the range of comics by the likes of Mark Laliberte, Cole Pauls, and Kimberly Edgar.

It seems fitting then, that this anniversary issue happens to contain the winners and two honourable mentions of our biennial Emerging Writers Fiction contest, judged this year by Zalika Reid-Benta, who published a story with us in the immediate wake of her debut collection back in 2020. Of this year’s contest winner, “Speaking in Regrets” by Owen Schalk, Reid-Benta said, “‘Speaking in Regrets’ paints a haunting picture of loss, grief, and heartache, written with a wistful clarity that ensures this story will stay in your mind long after you have finished the last sentence.” These emerging literary luminaries share the pages with established writers like Rob Winger, Shane Neilson, and Carleigh Baker, who is profiled in celebration of her latest collection of short stories.

Returning to the editor’s note from that first issue, Phillips wrote that “our goal is to share our enthusiasm for work that provokes, excites, and entertains—writing that makes you want to read more.” That remains our goal today, and we hope that when you put this issue down, you’ll find that you’ve been provoked, excited, and most important of all, entertained. Thank you for ten years of reading and here’s to ten more.

Best wishes, The HLR Collective

issue 1 volume 1 spring + summer 2014 $6.95 Priscila uPPal // fiction // poetry Wayson c hoy k r sten m c rea // art

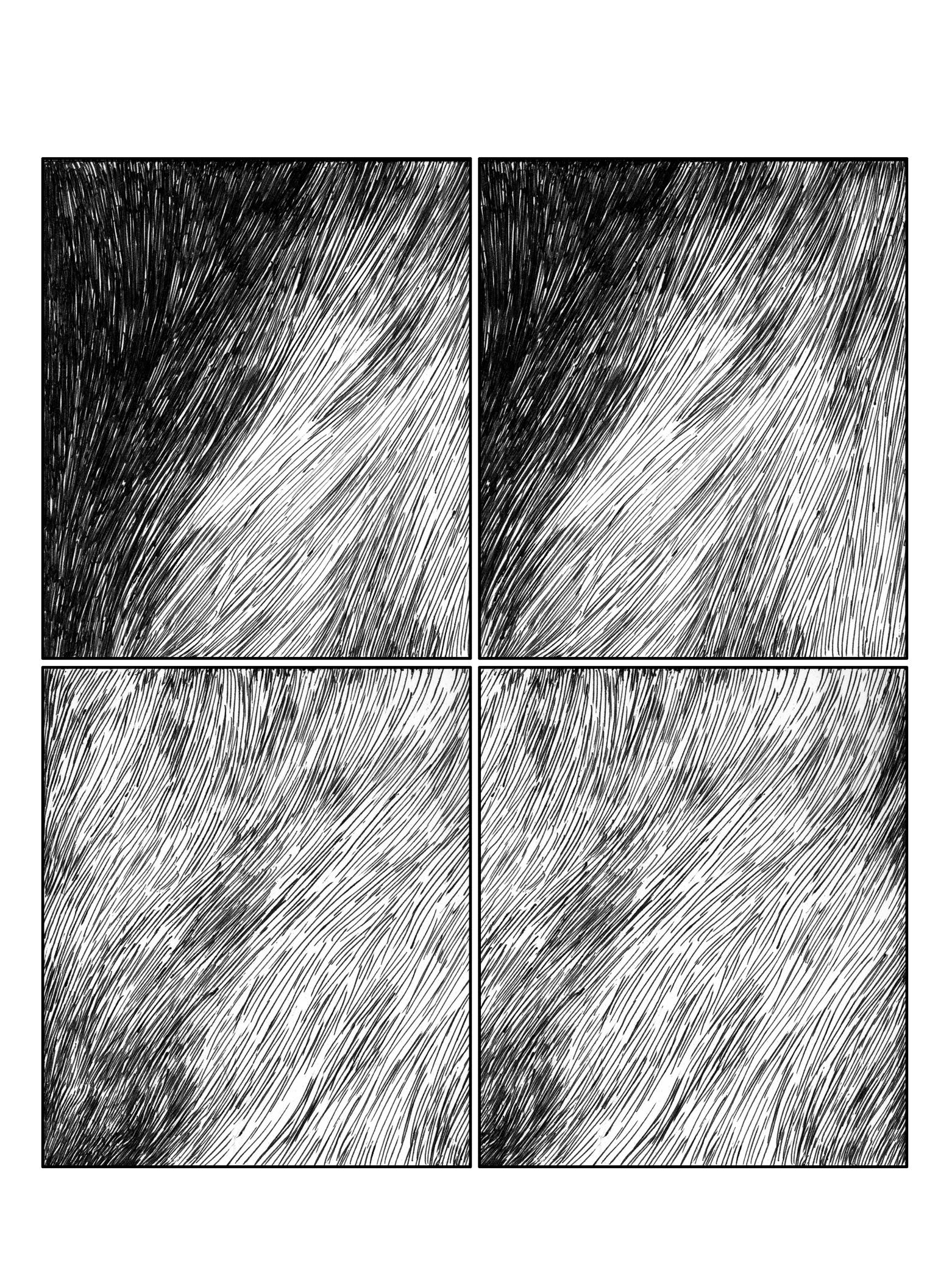

FLICKER, 2020 | STEVEN BECKLY

Image courtesy of the artist.

FLICKER, 2020 | STEVEN BECKLY

Image courtesy of the artist.

OWEN SCHALK

SPEAKING IN REGRETS

The first ghost came the night Dad burned the horses.

“They have to die,” he said, steam pushing through his cloth mask. “It’s the mammoth plague.”

The fire’s heat wormed through icy air. In the barn, the horses beat their hooves, squealed with terror. I pictured their eyes wide and shivering, flames tadpoling through the brown water of their irises. My gut churned. I could have saved them, I thought.

Mom had left a week earlier, but given Dad’s state of mind, you’d think she’d been gone for years. He gave up shaving. He stood at the window for hours holding a loaded shotgun. As soon as the radio spoke of a “zombie virus” released from a mammoth’s carcass in the thawing permafrost, he snapped. News reports said the virus wouldn’t reach Manitoba for months, but he was convinced it was already here, creeping through our horses and pigs and chickens, and that it would soon transfer to me or Grandma. “If one of you died,” he said, “I couldn’t live with myself.”

We were used to struggle by now. Soil erosion had ripped away our fields’ topsoil so nothing had grown for years. Annual droughts had depleted the aquifer under our house. We were forced to ration well water, every cup handled with the reverence of Christ’s blood. And the wildfires. When we stepped outside, we became scuba divers, geared up with goggles and cloth masks and toques to keep the ash out of our hair.

It was too much for Mom. “I have to go to Winnipeg,” she said. “My parents are scared. My sisters don’t know what to do. I need to be there for them.” Dad tried to talk her out of it. The situation in Winnipeg was terrible. We still had electricity in those days, so we had seen the news of ransacked storefronts and mile-long lines for gas. “I’m sorry, Mark,” she said, “but you’re lucky. Your mom’s here. My family’s two hours away.”

I had to make a choice: brave Winnipeg with Mom or stay on the farm with Dad. Even though I loved

Mom more, I picked Dad. It was safer here—predictable, at least. Who knew what Winnipeg had in store?

By then, Dad was close to breaking point. When she left, he shattered like a clay pigeon.

I had to make a choice: brave Winnipeg with Mom or stay on the farm with Dad.

I tried to talk him out of killing the horses. “We don’t have any bullets left,” I said. We’d used them up shooting the hundreds of bears who had migrated south fleeing the bush fires.

“Don’t need bullets,” he said, eyelids heavy, hair a rat’s nest. “Still have some gas left.”

On the night of the burning, Grandma was fast asleep. She’d been bedridden for two years. Dementia had eaten her brain, so she did nothing but speak to visions of Grandpa, dead a decade, and her little sister Doris, killed in a car crash at seventeen. The only time Grandma smiled was when Dad carried her to the barn to see the horses, to stroke their downy snouts and inhale the rooty aroma of their coats. Had she been awake to see the barn burning, she’d have lost whatever scrap of sense she had left.

The horses filled the night with snorts and squeals. I looked at Dad. In the darkness behind him, a sliver of blue light wriggled up from the ground. It opened into a glittering rectangle. I squinted. What the hell? The

OWEN SCHALK // 5

rectangle morphed into an oval. It grew appendages: two arms, two legs. Features surfaced: eyes, a nose, a mouth. Gleaming and blue, the ghost shone like water pierced by sunlight.

“Dad,” I said, disbelieving. “Grandpa’s back.”

Dad almost had a heart attack. He dropped to his knees and called, “Is that you?”

The spirit approached. His blue glow kissed our hands and faces, turning the smoke-choked farmyard into an aquarium tunnel. I had been a kid when lung cancer took Grandpa to his grave, but the old man looked just like I remembered him, apart from his aquatic shine: small eyes, wide ears, stubby nose nestled in a fat grey moustache.

Grandpa smiled lovingly. Then he spoke. His voice was as warm and sweet as it had been in life, but distorted, like he was talking into a tin can.

“I regret that I didn’t ask Suzie Hallward to dance in eighth grade,” he said.

We didn’t know what to say.

The old man looked at me, still grinning. “I regret that I didn’t buy Jack Hagen’s combine.”

Dad frowned. “Are you trying to tell us something?” He went to hold his father’s hand, but Grandpa was blue mist, ungraspable. “What do you want?”

Grandpa walked toward the house. As we watched him pass, he said, “I regret that I smoked a pack a day.”

We followed the ghost to the house, down the hall, into Grandma’s bedroom. She had little reaction to the sight of her dead husband. Just a nod and a smirk.

To say every country was wrestling with the fallout of environmental, economic, and social collapse would be understatement.

The last thing the world needed was ghosts. To say every country was wrestling with the fallout of environmental, economic, and social collapse would be understatement. They weren’t wrestling. They were fighting over a knife in the mud. In Canada, a mixture of wildfires and drought had put the country on the edge of famine—which, when paired with the toxic brew of viruses emanating from the melting Arctic, was driving the nation mad. City governments closed their borders to wildfire refugees, declaring they barely had enough resources to keep their current populations alive. Meanwhile, pipelines drained the last of the tar sands, while the RCMP arrested whoever still had the clarity of mind to protest.

Then, all at once, ghosts rose from the earth. Despite the constant stream of baffled scientists and paranormal experts on our TV screen, nobody could offer a rational explanation for why billions of spirits had arisen overnight, what they wanted, or why they thought the end of the world would be an appropriate time to make themselves known.

Likewise, there was no answer for why the ghosts spoke only of their regrets, from the most trivial (dropping a loonie down a manhole cover) to the most life-destroying (accidentally shooting their son with a crossbow). Regret was all the ghosts cared about. They had no questions for the living.

Social media still existed in those days. My feed consisted entirely of watery-blue ghosts saying “I regret this” and “I regret that” against backdrops of charred soil and smoky skylines. Part of me knew Facebook and Instagram wouldn’t last much longer, so I savoured those final days of mindless scrolling, the inexplicable warmth of cross-world connection. I learned the words for “I regret” in Spanish, French, German, Italian, Vietnamese, and more. I repeated them to myself as I lay in bed.

“Lamento.”

“Je regrette.”

“Ich bedauere.”

“Mi rincresce.”

“Toi hoi han.”

“I regret that I never renovated the kitchen,” Grandpa said.

Dad and I looked at each other. His jaw hung open. I’m sure mine did, too.

When my great-aunt Doris trickled up from the soil later that night, I was the first person she saw. She smiled at me and said, “I regret that I stole my sister’s sunglasses in tenth grade.” Then she looked at Dad. “I regret that I drove drunk.”

The night the ghosts appeared, Dad called Mom. In Winnipeg, the same thing had happened: ghosts rising through asphalt, sidewalks, bricks, linoleum tiles. Mom had already met both her deceased grandparents and her dead cousin. But the spirits were the least of her worries.

When I talked to her, she said, “It’s bad here. The looters, the gangs. We’re scared to leave the apartment. The ghosts are more annoying than anything else.”

OWEN SCHALK // 6

I grunted. I was distracted. “Listen, Dad’s losing it. He burned the horses. He wants you back here so bad.”

“I know, honey. Take care of him, okay?”

Take care of him? I thought. He’s supposed to take care of us

Days passed. A week. The ghosts didn’t leave. Grandpa and Doris strolled from room to room, stood over the burnt remains of the barn, intoning their regrets. When I wasn’t feeding Grandma, I hung out with the spirits. I had not yet lost my fascination. I listened to their tinny voices, studied the liquid ripple of their arms in motion, stood in their light to feel if it was hot or cold (it was neither). I wondered, why now? Why didn’t the spirits appear to us when we had the time and resources to analyze them? Perhaps the ghosts were like zombie viruses in the guts of mammoths, I thought, and as the global temperature climbed, pockets of frozen guilt melted and rose through the earth like steam. To tell us—what? How they wished they’d lived? Everyone wishes they’d lived differently. To use this moment to tell us that, when we living had much bigger concerns, struck me as somewhat selfish.

“Where did we go wrong?” I asked them. Doris said, “I regret that I didn’t curl my hair.”

“No, as a species. How could we let our civilization collapse like this?”

Grandpa smiled. “I regret that I didn’t ride horses with Hannah Graham.”

Dad lost interest in the ghosts. At first he was thrilled to see his dead father, but when he realized Grandpa wasn’t going to answer any of his questions about the afterlife, he went back to cleaning his shotgun or patrolling the barbed-wire fence.

I sat with Grandma, or the ghosts, or I looked at the family photos framed around the house. Mom and Dad’s wedding: Mom in a regal white dress with perfectly sculpted hair, Dad disheveled, a farm boy stuffed into an ill-fitting tuxedo. My first-grade picture, sandyhaired, missing teeth. My graduation photo, taken just five years ago, when we all pretended a solution was coming, a one-shot vaccine that would inoculate us against the end of the world.

Looking at the pictures, I wondered about my own regrets. I regretted that I didn’t spring for the limited-edition Cyberpunk 2077 Xbox. That I didn’t ask Sydney Fable out in high school. That I didn’t get to spend more time with Grandpa. Unexciting, I know, but when the ghosts came, I was twenty-four. I didn’t have a lifetime of mistakes to look back on.

On the twelfth day, we were used to ignoring the ghosts. Even I was sick of their self-absorbed ramblings, the endless stream of social media posts, the breathless news reports. It was driving us crazy. The next day, however, we received a distraction that made us forget all about the ghosts and the TV—though it was not a welcome one.

Mom died.

Dad had tried calling her all day. Since she left, they had talked three times each day, in the morning, noon, and evening. When she didn’t pick up, he assumed the worst. He paced the house, pulled at the tumbleweed of his hair. I heard Mom’s voice: look after him. I did my best to reassure him, but when her ghost dribbled up from the living room floor that night, dousing the walls with marine-blue light, there was nothing more to say.

“Linda,” Dad croaked. “No.” He covered his eyes. His lower lip convulsed. “W-What happened?”

When she didn’t pick up, he assumed the worst. He paced the house, pulled at the tumbleweed of his hair.

“I regret that I didn’t see Bowie in 1983.”

“Please,” Dad cried. “Not you, too.”

Mom looked at me, sweet brown eyes and a caramel smile. “I regret leaving.”

After two weeks, the ghosts disappeared. I saw it happen. In unison, Grandpa, Doris, and Mom looked at the floor, as though a bell had chimed, and drizzled between the grains of the carpet, sucking away the blue glow that had coated the walls for fourteen days. It happened everywhere on Earth at once.

I wondered, why two weeks? How had all the ghosts known to disappear after fourteen days? I didn’t know, and I never will. All I knew was that we were alone again—Me, Dad, and Grandma—and the world felt a little quieter. A little darker.

Dad was inconsolable over Mom’s death. He sat down in his chair in the living room and only rose to use the bathroom. I had to bring him food and water. After a few days, he began to speak in regrets.

“I regret that I didn’t go with her.”

OWEN SCHALK // 7

Creative Writing–Fiction, Creative Non-fiction, Poetry Correspondence Program

Looking for personalized feedback on your manuscript? Our 28-week online studio program is customized to address the needs of your booklength project. Work from the comfort of home under guidance of our exceptional faculty.

Program starts every September and Januaryapply now!

There is a story to be told here. humberschool

“I regret that I didn’t kiss her goodbye.”

“I regret that I didn’t die with her.”

The media was perplexed, but quickly moved on to the latest catastrophe, from the collapse of the Lockport Dam to the worst cyclone in Sri Lankan history, until the day the lights went out.

Inever thought I’d long for the days when Dad was burning horses, but I did. It was preferable to his sitting in his chair, watching TV news for the three hours per day we had electricity, the rest of the time staring at the black screen. When I asked him if he was hungry or thirsty, he answered with a regret.

I wondered how long I could endure being the only sane one in the house.

The responsibilities fell to me, of course. I had to prepare meals, I had to patrol and repair the fence, all while Dad sat in his chair, beard snaking down his chest. I was nervous about taking over his tasks, but I channelled my father on his best days, the stalwart man who kept the farm running as the earth boiled, as the land dried out, as the loan vultures circled our land. If he had found a way to carry on, so could I.

One afternoon, I noticed a section of wire fence trampled to the ground. Raiders? No, I decided. The fence hadn’t been cut. A branch had fallen over the barbs and an animal of some kind had climbed over. A bear? Maybe. I cocked the shotgun and went searching. There was a horse in the yard. Tall and black, a stallion by the looks of it. The animal was gorgeous. Its eyes shone like dark pearls. Even its hair found a way to glow through the smoke.

I went inside and told Dad. His eyes flashed, and for a second I thought he was about to share in my amazement. Then his face changed, and I figured he would reveal another regret. He didn’t. His expression fell and he turned to the empty TV screen.

I put a mask and goggles on Grandma and carried her outside. When she saw the horse, her body rumbled with laughter. “Oh, handsome,” she said. I carried her closer. Her pale, veiny hand trembled across its coat.

“On our first date,” she recounted, a glint of nostalgia in her voice, “Harold took us horse-riding.”

The stallion huffed, whirled its tail, and ran toward the trampled fence. As it sank into the smoke, I added a regret my list: I didn’t ride our horses one last time.

///

OWEN SCHALK // 8

forwriters.ca

ROB WINGER

THE LONG AND THE SHORT

The long and the short of it is that I don’t believe in the dusty space gods you’ve invented with outdated ex libris geography-book neckties, and I don’t believe in any neck-tied geographer who says they know for sure whatever they know for sure. I don’t believe in childhood teacups or grown-up tax breaks, in white teenaged punk, old-age bingo, or the kind of mid-life crisis that always ends up driving low-end automatic-only sports cars.

The long and the short of it is, in fact, that I most believe in this single kindergarten kid being scolded for going bonkers in gym class, who says he’s sorry but he just didn’t bring his walking legs today, or in the grinning dog chowing down her hundred discs of backyard rabbit poop, rolling greasy into marsh mud, then waiting with such utter admiration for me to bring secured within its plastic scoop these dried-out squares of kibble moulded by a factory in France.

Halfway across a main span, I can’t think too hard about dead or live loads or where the cantilever might have ended, about the plastic deformation possible in each latticed steel truss, how each suspender rope is only strong enough to hold us up when it ties itself to the main cables set atop each far-flung tower.

THREE POEMS

So the long and the short of the long and the short of it must be, then, that space-god neckties and running-legs retrievers won’t stop me from dreaming I’m teaching a class for which I’m unprepared, again, or you from thinking you’re naked in a wooden high school calculus exam, that my long-dead grandma or your long-gone father or another long-lost brother’s sister might return to us on the far subway platform or inside a pastel ICU room or maybe within the glinting heat of a winter greenhouse thick with germinating seeds; in those dreams, we know their messages will

absolutely solve, ad infinitum, every last necktie library geography, so we remember what they say with desperate urgent care, but just until the red alarm clocks we’ve prepared upon our white bedside tables announce, again, another morning’s finally made it.

ROB WINGER // 9

POLAR BEAR

If you should come face-to-face with one, back away (slowly at first), while peeling off your clothes one item at a time. The bears are very curious and they should stop, sniff, and perhaps play with each item as they come across it, leaving you free to run across the Arctic buck naked. Until they catch up with you, of course. Or you die of exposure. Either way—what an experience!

—“GET

NAKED, AND OTHER ADVICE TO FEND OFF A POLAR

BY PAULA FROELICH, NEW YORK POST, AUGUST 29, 2020

It wasn’t really a polar bear’s fur glistening through the gap in the dream’s staircase hammered closed as though it were a ladder leading to a still-sealed attic hatch. So this wasn’t the first episode of Lost. I got to the top of the wooden stairs, sleeping, saw its fur was dark, then carefully descended.

If approaching dawn or harnessing a dog, it’s a good idea, I’m told, to write what you know. But don’t harnesses signal that I pretty much know nothing? The trees, I might declare, are glorious. But each birch is rotting, too. We all need, um. Split your heart in two, et cetera, and, well. I’ve been married twenty years already and have never met a staircase polar bear for real. All the unsealed pine-high attic hatches are waterproofed with caulking.

Put a bell on your bike, they tell me, if you’re riding through these foothills; three cubs were spotted here just yesterday. And three blocks over, cherry-picker electricians have closed down the street to get an urban black bear down from some old Victorian’s weeping willow. So, I might as well forget that attic hatch. Step this way, the signs say, to find the zoo’s concrete underwater viewing station; down there, each huge drifting polar paw will press its claws, for us, right flat, full, against the porthole’s gleaming blue.

ROB WINGER // 10

BEAR ATTACK”

CONCRETE CREEP

I.

Not creep as in that old, eerie Radiohead hit, but concrete creep: the gradual, undetected ways our spines compress or discs slip while we hurtle rocks en route to the forest’s widest redwoods.

And not creep as in crêpe, as in pancakes or bright bunting, as in stopping short the office mail to stand atop its silver cart, declaring, just this once, the birthday cake might be for everyone.

Creep as in how the dirt keeps on getting under my fingernails, as in the forces slow-recorded in the sculpting of a river gorge, as in the wind’s play around cliffsides that turn each stone to the smoothest-ever suicide.

II.

In a prestressed concrete arch, concrete creep is “the continual contraction of the compressed material even when the compression load does not change.” So what we carry, we carry against our lungs, held within a locked-tight rib cage.

Out in the schoolyard, we remember, we parents, how our kids would climb the highest structures, if they could, steel and plastic, clouds and oak, then trust gravity to carry them all the way through an orange tube’s swoosh.

They’re right there, our kids, we might remember, decades gone, still emerging from the plastic chutes. Their mouths turn up the blueness of the air, the rustle of each blossom in the canopy above us, watching. This is their scent, back then. Their voices. And they’re gone, of course. Long gone.

We carry that compression, our children, still just kids, running from slide to stairs to start again, filled with grinning light, so possible, up as high as they can go.

Every single kid, the way they were, will disappear, creeping up our door frame pencil marks to pack away their Lego bricks. But they remain certain, too, those kids, for us, right here, against our lungs, compressed, still letting go the bar atop the plastic slide, still drifting down to earth as if their only future were the ground’s secure abutment.

ROB WINGER // 11

///

AGA MAKSIMOWSKA MONOCULTURES: AN ESSAY ON TENDER IS THE FLESH AND SINGLE-SEX EDUCATION

Walking home one late August afternoon from a new job, I cried so hard a young man offered help. I wasn’t mourning the loss of the old job, nor was I unhappy about the new one. Tender is how I felt when I left the institution where I started my teaching career, an all-boys private school that shaped much of what I thought and how I behaved, which is to say not tenderly at all.

And yet, even though I was a woman, I fancied myself one of the boys. A respected colleague told me early in my career, “You’re an alpha without being a bitch.” I was flattered, albeit uncomfortable. Here was approval from one of the big dogs, a well-liked veteran. Bitches taught at the school, but left prematurely, tails between their legs. I was an alpha: tall, deep-voiced, decisive, and sarcastic. I succeeded at teaching boys.

In the summer of 2022, when I left after eighteen years, something cracked. I felt wild and disoriented, exhausted and used up, like I had escaped captivity. Sure, I had also escaped the pandemic, but there was more to it. I was free. The boys’ school had consumed me and left me bare. I developed debilitating vertigo, which, after some investigation, turned out not to be a brain tumor or Ménière’s disease, but my body’s stress response to the change. A dam had cracked. It had been a stable, well-paying job with attractive perks: great benefits, small classes, generous colleagues, and international travel opportunities, yet it was toxic, taxing, and terrible for me.

At the new, gender-inclusive school to which I walked or commuted via subway—not by car, which I permanently parked—I suddenly had time to read. I was teary and brittle, unsure of how to behave in a more nurturing environment. I no longer had to be

loud and brash; in fact, I couldn’t be. People’s feelings got hurt. Personality traits that lay dormant for years were now in demand: patience, gentleness, kindness. It was then that I read Agustina Bazterrica’s novel Tender Is the Flesh and my healing began.

“This is your self-help book,” my partner marvelled. “A dystopia about cannibalism?”

“Isn’t single-sex private education a cannibalistic dystopia?” I joked.

No book in recent years moved me like Tender Is the Flesh did. In Spanish, the original language of the book’s 2017 publication, the title is Cadáver Exquisito, or Exquisite Corpse, a reference to the surrealist parlour game made famous by André Breton and Frida Kahlo. Translated by Canadian Sarah Moses in 2020 and released into the English-speaking world during the pandemic, Tender Is the Flesh, which won Argentina’s 2017 Premio Clarin de Novela prize, is about access and excess, about language and how it’s manipulated, which is perhaps why it spoke so powerfully to me, an immigrant ESL kid who taught wealthy boys English. “You’re the English teacher,” said one parent incredulously. “Those poor boys,” she said, exhaling dramatically as she looked me up and down. “Having to suffer through class with you around.”

Tender Is the Flesh is the story of Marcos, a slaughterhouse manager who recently lost a child and whose marriage broke up as a result. He is estranged from his sister and cares for a father with dementia. Marcos is an automaton, a skilled “stunner” responsible for the first strike in the killing of humans, or head, as they’re referred to in cattle terms. Marcos is also a teacher, instructing new recruits on how to initiate killing

AGA MAKSIMOWSKA // 12

so that the head don’t become spooked or nervous, thereby ruining the meat by making it tougher, less tender. Marcos observes that “teaching to kill is worse than killing.”

Marcos perpetuates the very system he criticizes, a system of state-sanctioned cannibalism, a population control mechanism that’s a response to a mysterious virus that wipes out all animals in this near future, a future that’s entirely plausible and possible. He observes that the slaughter of humans for consumption can be normalized only with automation, a process which is concealed with euphemisms. “There are words that cover up the world,” Marcos says. “Synonyms … the choice of one over the other speaks to a distinct view of the world.”

I spent my career teaching in a school that claimed to be a boys’ school “by intention.” I marvelled at that statement. As times began changing, some of the faculty advocated for referring to our charges as “students” instead of “boys,” but various stakeholders protested: they were ardent about “boys.” Much time, energy, and resources were spent studying, talking about, and disseminating information about how boys learn, what they need, how they develop character. Little was spent scrutinizing the fact that the whole exercise was antithetical to how education actually works or to the violence that’s intrinsic to the creation of a “boy.”

We do violence to ourselves to maintain power, to stay alpha, to be as male as possible. A former student who’s now in university recently emailed me and wrote, “I’ve noticed the horrified expressions on my friends’ faces when I tell them I went to a private boys’ school.” He’s having to do a lot of unlearning now. Those outside the system think it’s unbelievable, yet those invested in it hang on to it because humans love to be special, need to have something exquisite, different, rare. What’s stranger is that this archaic system with deep roots in religion shows no signs of going away. No matter how many gender task forces single-sex schools establish, it won’t change the fact there is a surge in interest in singlesex education. Why? Bazterrica has an answer: fear. Tender Is the Flesh is not a manifesto to convert readers to vegetarianism. In a country where, in Bazterrica’s words, “meat is religion,” special meat replaces animal flesh and is reserved for those wealthy enough to procure it. The rest of the dwindling population scavenges or feeds on flesh of prisoners or the very sick and old, certainly not special meat. Bazterrica’s message in her novel is that capitalism is cannibalism, and the fear of not getting enough, of missing out, of being left out, is what motivates humans to behave more and more despicably.

Bazterrica, who is a fixture in the Buenos Aires literary community, was a poet and short story writer first. In university, she studied art history. In high school, she and the other girls in her classes were taught exclusively by nuns, who ensured compliance in their pupils through control and terror. “Education is inherently violent,” Bazterrica wrote. “And plenty of women perpetuate patriarchy. You don’t have to be a woman to be a feminist.”

Bazterrica researched factory farming in great detail for nearly a year in preparation for Tender Is the Flesh. Monoculture may not work in the long run, but it’s terribly efficient and productive in the short term. It yields maximization, eases management, provides opportunity to exploit technologies and specialization, and produces higher revenues. It is a system that’s in complete service to capitalism, where profit is king and everything else is secondary. This brutal, violent novel could be an instruction manual for monoculture factory farming. “Nothing in the book is made up,” Bazterrica told me. “We already do all those horrible things to animals. I just made them happen to humans.”

In the ’90s, I attended and graduated from a large, public high school with a functioning auto body shop, an arts program, a smoking section out front, and murals everywhere. In the early 2000s, I was hired by a private school for boys where the annual tuition was more than my mother’s salary as an ESL teacher at one of the city’s several immigrant education cen-

A respected colleague told me early in my career, “You’re an alpha without being a bitch.” I was flattered, albeit uncomfortable.

tres. Students drove to school while I took transit, and instead of giving me feedback on my teaching, posted comments about the size of my ass on a website. In no time, sexual comments about me appeared with such frequency that my partner took to moderating the site and flagging them before I could read them. When I complained to a school administrator about being sexualized in that way, he shrugged, and later published an op-ed in a trade magazine about online platforms

AGA MAKSIMOWSKA // 13

giving students agency and expanding their voice. The insinuation was that I was complaining about compliments. Boys will be boys; they were off-gassing. I was popular, after all, and I enjoyed the popularity. Most kids liked my classes. I received nice Christmas gifts. But the male gaze at work made me feel captive. I felt like I provided an illusion of social change while, in actuality, changing nothing except parts of myself to fit in, becoming colder, more aloof, more violent.

I became estranged from my sister during my tenure at the school, a relationship that ended in part due to my overdeveloped aggression, a way of being I attribute to the climate of toxic masculinity I experienced at work. I was very good at classroom management and used my size and sarcasm to dominate. I was unapologetic for having zero patience and plenty of bravado. I was the same with my family. Other female teachers were made to complete classroom management workshops, while I attended a Master Teacher conference in year ten.

“You condone what you tolerate,” said a wise friend to me once.

I felt like I provided an illusion of social change while, in actuality, changing nothing except parts of myself to fit in, becoming colder ... more violent.

I could condone a lot, but not the near constant homophobia that a boys’ school breeds. The jokes, putdowns, and slurs were too much. I live a privileged, heteronormative life of a cis-woman who’s married to a cis-man, but there’s more dimension to my sexuality than I’ve discussed at work or in my writing. At school, I was known as a fervent supporter of gay rights, so when yet another student privately came out to me, a colleague and I decided to put rainbow stickers on classroom doors. We saw no harm, only an opening for discussion. We organized youth-led workshops on inclusive neutral language and educated on creating safe spaces. In no time, I was hauled into an administrator’s office. I was twenty-nine then. I was reprimanded until I sobbed, asking profusely for forgiveness. “Next time,” the administrator warned, “ask for permission. That is not how things are done here.”

Those words struck me. That is not how things are done here. I had to submit to the system, all of its rules—spoken and unspoken—norms, traditions, and expectations. A system works hard to protect itself, like any organism, adaptable yet resistant to change.

Tender Is the Flesh is a nose-to-tail narrative that creates a framework to justify a moral pass. The mysterious virus-infected animals and birds are a threat to humanity. The only way to ensure humans get enough protein in their diets is to eat special meat. Slavery is illegal and punishable by death; slaves provide labour, not food, whereas cannibalism is not only legal but encouraged. No vegetarians or vegans in this world. Some families even keep head in their homes, carving out pieces for dinner while the head is still alive, the meat freshest and most tender. The contradictions and paradoxes, which are the building blocks of dystopia (“Freedom is Slavery,” etc.), are what make Tender Is the Flesh entirely engrossing and infuriating.

At the boys’ school, we talked of diversity and inclusion while excluding much of the population. We focused on character education while ignoring reprehensible behaviour and condoning violence. We celebrated leadership and innovation while making very little structural change. Every few years, a scandal made the news about some boys’ school, something terrible and depraved. We held staff meetings. We were outraged. There was commentary and calls for change, but the news cycle marched on and the pillars of tradition and excellence remained firmly in place. The locker room sexual assault at St. Michael’s College in Toronto or Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s yearbook comment at Georgetown Prep are not altogether different from what happens at all boys’ schools, but boys’ schools haven’t been cancelled.

When I turned thirty, an administrator suggested I get married and have kids so as to be less restless, less flaky, more tethered. My low-grade activism was getting annoying to those tasked with managing me. Parents grumbled about the feminist agenda in my classes. As women age, the childless ones become dangerous, deviant, distracting. It’s time for our makeover from sex object to mom. This is when the bitches quit, but since I was an alpha, I got married, had kids, and stayed for another decade.

Bazterrica plays a lot with sex and sexuality in Tender Is the Flesh. She wrote the novel as commentary on the insatiable nature of capitalism, to make a statement about how we’re essentially devouring each

AGA MAKSIMOWSKA // 14

other in this exhausting race for more and more and more. But unlike me, Bazterrica is not apologetic about her feminist agenda. Women figure prominently in the novel as heroes, villains, victims, and everything in between. One is Marcos’s social-climbing abhorrent sister; another is a cold, unfeeling butcher. A Mengelelike aging scientist experiments on the silent head whose vocal cords have been removed so they can’t protest. The last, and probably most important to the narrative, is a female head that’s gifted to Marcos by a wealthy breeder.

Marcos calls the gift Jasmine because of her strong, intoxicating smell, which reminds him of the flowering plant. From that moment on, she’s no longer cattle, but a kept woman. Marcos observes that “her beauty is useless. She won’t taste any better because she’s beautiful.” Her wildness and naturalness are a contrast to the sterile and clean slaughterhouse, and in the strange relationship between keeper and the kept, Bazterrica creates a great deal of tension that propels the action of the novel forward. A profound sense of discomfort follows the reader whenever we encounter Jasmine and Marcos; questions swirl in our heads. We walk a fine line between rape, captivity, slavery. Marcos pushes the boundaries of what’s permitted in the system he inhabits. He has sex with Jasmine, yet the only real affection and intimacy in the novel happens between Marcos and a pack of wild puppies in an abandoned zoo. Bazterrica is clear here that the loss of animal life has profound implications to human life, and tenderness is not only defined by sex. In the end, Marcos uses Jasmine to heal himself of his grief, and in the process, betrays the reader. We follow him through the narrative as an antihero critical of everyone and everything, but he profoundly disappoints us at the end. All he cares about is his grief, the wounds he wears. He’s as selfish as we all are, a product of our capitalist values.

The most striking character in the novel is the butcher, Spanel. A real alpha. Bazterrica based Spanel on a 2005 photograph called “Carnicera” by Argentinian photographer Marcos López. A dominatrix type whose “intensity makes [Marcos] uneasy,” Spanel is Marcos’s lightning rod. Without her, he would lose his mind, like his father lost his when the animals died. Spanel has an assistant whose gaze is that of a dog, one of unconditional loyalty. She keeps men in her shop like she keeps the meat. She dislikes smiles because they show a person’s skeleton. She smokes and drinks so she will taste bitter when her turn comes to be sold for meat. She threatens to try one of Marcos’s ribs. The

two of them have conversations that are prohibited, which makes them deviants. Marcos needs Spanel to stay sane in an insane world, yet “there is something about her he’d like to break.”

Jasmine and Spanel are foils for each other. Marcos is turned on by Jasmine, only to lock her in his barn, drive to Spanel’s shop, and have ravenous, violent sex with the butcher, intercourse so full of rage that he finally breaks Spanel and makes her scream. She produces a single brutal, dark cry. The reader wonders whether Marcos rapes Spanel. Her assistant wants to save her, but the door is locked, so he can’t. The climax of the novel is literally a climax; Spanel orgasms amid a blood-spattered cold room, her consent delayed for the reader’s discomfort, mingling with questions about our own purpose, desires, and plan.

Aprivate school, like every other capitalist enterprise, is violent, insatiable, always adding new initiatives, increasing competition, elevating the stakes, improving the marketing, adding accolades: on and on it goes. It’s utterly exhausting. After reading Bazterrica’s novel and transitioning into a less segregated work environment, I wondered: “When do we ever apply our creativity to accomplishing less, to doing less, to reducing, paring down, as opposed to always striving for more? Where do we employ our

When do we ever apply our creativity to accomplishing less, to doing less, to reducing, paring down, as opposed to always striving for more?

best and brightest, use our talent, innovation, and education in the name of restraint, constraint, moderation, lack? How can we do less harm?” I am not sure. I have no answers, only questions. I suppose that’s what the next eighteen years in education will be about: unlearning, undoing, recalibrating, rebuilding my lost relationship with my sister, and teaching my own children in a more tender way.

///

AGA MAKSIMOWSKA // 15

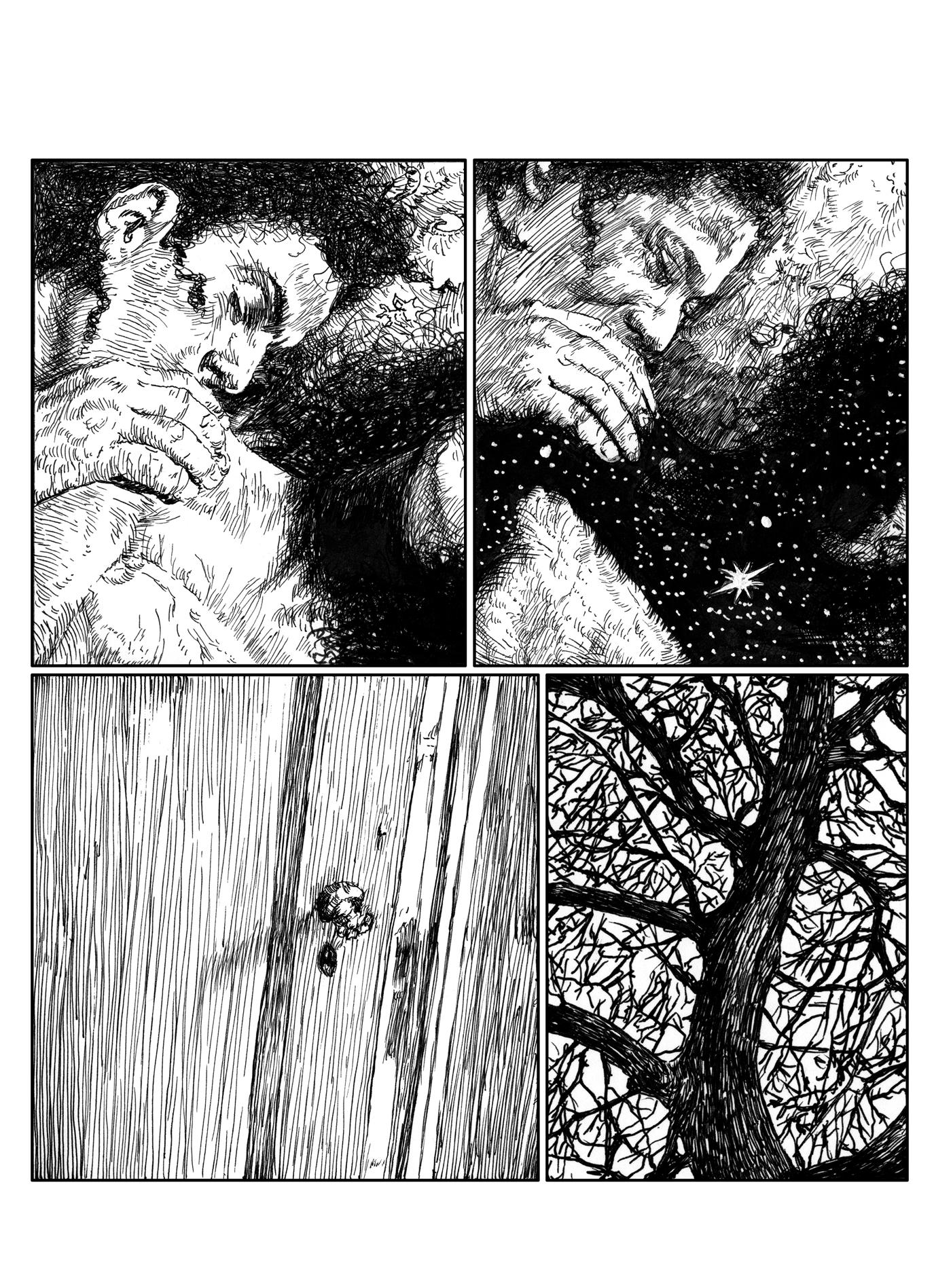

HEADS UP (INSTALLATION VIEW), VINYL PRINTS AND GLAZED CERAMICS, 2023 | STEVEN BECKLY Image courtesy of the artist.

LYNDA WILLIAMS BERMAN

To be clear, I don’t understand what Heraclitus meant about opposites. I still need to read that shit.

—ERIN

That summer I read Natasha twenty times trying to figure out how it worked so I could evoke a similar response through a narrative told from her perspective. The problem was that I had both more and less power than she did. Basically, I had more in common with Berman and I was too stupid to know it. At least that’s how I read it now, when I look back on those pages, brimming with feminist defiance and misunderstanding of the agency Natasha actually had.

I was living on the top floor of a four-storey walk-up in a bedroom that was technically a closet. A walk-in just large enough to accommodate a twin bed and the three cardboard boxes that contained all my personal effects. My roommate, Amber, had a lot of sex and I didn’t have a door to shut, so I spent every spare minute at the library, quietly defacing a hardcover edition of Natasha with copious marginalia, a dull HB2 pencil my weapon of choice.

At the time my friends were decorating their walls with Nickelback posters, meanwhile I had a massive cork board with annotated index cards of the story’s arc.

“Isn’t this what serial killers do?” Amber said, squinting at the inverted question mark.

“I’m writing about one of those, too.”

“No shit. It’s $27.38 for the phone bill.”

“Didn’t we just pay it?”

“It comes every month.”

I was pretty sure the utilities came every time she needed extra cash for E, but I was only paying $150 for the closet, so I had no complaints.

Unlike Amber, I didn’t have a lot of boyfriends. J.Lo and Beyoncé had confidently led us out of heroin chic, but taking up space was the least of my problems.

It was my mouth that got me into trouble. My uncle had nicknamed me Bumble Bee for the invective I’d been spouting since I could speak. I’d made up my mind in middle school that if having a boyfriend meant pretending to know less than I did, then I’d rather listen to my whole class call me a lesbian at recess. I could ring my own bell, even with guys that’s mostly how I finished, and really, if Betty Friedan had devoted more time to masturbation, it would be an entirely different feminist landscape. Can you imagine what the world would be like if men hadn’t benefited so directly from the sexual revolution?

Right there. That’s the kind of question that caused problems. You’re not supposed to ask that when a man is undressing you. But seriously, this dude tried to impress me by unhooking my bra with one hand. Make me come before you do. Maybe do it twice. That ’s impressive.

So I was single and having all the orgasms my partnered friends whined they weren’t getting, and I was utterly immersed in my schoolwork. I wanted to pursue graduate studies, and I was using the summer to get a head start on my capstone project. Beyond an MFA, I had a five-year plan. I was going to give Alice Munro a run for her money, and I was going to do it before I turned thirty.

“Y

ou can’t do that.”

The voice startled me. It was Saturday, the library had barely opened and I was sure I was alone, leaning against the pillar, marking up the dialogue between Berman and Rufus. I looked up at the speaker. He was about my age, tall and good looking, despite the bleached hair and dark goatee. He was wearing a white-and-blue pearl-snap shirt that I instantly wanted to borrow—I knew it would look better on me since I had tits to fill out the pockets—and by the colour of his

LYNDA WILLIAMS // 17

face, I could tell he’d clocked that I was wearing my Spray Lake Sawmills T-shirt without a bra. I tucked my pencil into the book to mark the page.

“You work here or something?”

“No, but—”

“Then you can’t tell me what to do.”

He folded his arms over his chest. “What if everyone did that?”

He understood the categorical imperative. Good for him.

“How would you like to read a book covered in someone else’s crap?”

“It’s not crap.”

“You didn’t answer the question.”

“Not everyone is so poor they can’t afford their own copy of Natasha.”

“So you think you’re special?”

“I know it.” I gave him a little shove to signal the end of our conversation, but he didn’t leave. “Have you even read it?”

“Of course. Would I care this much if I hadn’t?”

“I don’t know. You seem pretty intense.”

A librarian finally poked her head through the stacks to shush us.

“Come on.” He took the book from my hands and tossed it on a shelf.

I’m not sure why I followed him. Some combination of pheromones and a desire to steal the shirt? Probably because I thought it would make a good story. While Amber collected notches on her bed post, I was busy collecting strange experiences I hoped to weave into fiction. My young life had been uneventful in a way that troubled me as an aspiring troubled artist. How would I write without memories that tortured me? I wasn’t the first young woman to underestimate her imagination.

He took me to a diner on Spadina. He must have been a regular because nobody came to take our order, but someone showed up with two plates of scrambled eggs minutes after we sat down.

He told me that he’d seen me marking up the book before and that he’d read my notes. He knew I miss-shelved it on purpose so others wouldn’t find it.

“Why are you so obsessed with Bezmozgis? Are you Jewish?” He tightened the cap on the salt shaker and sprinkled a little into his palm.

“No, and not Bezmozgis. Just the story.”

“Why?”

“It’s a fucked-up piece.”

“If you think the story is effed up, what does that say about the person who can’t stop reading it?”

I drove my fork into the eggs. “Doesn’t it make you angry?”

“No. It’s moving.”

“Have you ever considered that we’re empathizing with the wrong person? Berman almost makes you forget she’s being exploited.”

“She initiates everything.”

“She’s fourteen. She was groomed.”

“Don’t you think she knew her currency?”

“Is the power even hers if it’s contingent upon the desire of men?”

He shrugged. “Too bad you weren’t in my English class last semester. The discussion would have been a lot more interesting.”

I pushed away my plate and reached for some crumpled bills in the pocket of my cut-offs. Whatever story I thought I was chasing wasn’t unfolding at this two-top.

He waved me off. “It’s on me.”

“I’m not in the habit of letting men pay for my food.”

“Then you’ll be happy to know it was on the house. I work in the kitchen.”

The next time I saw him at the library he gifted me his copy of Natasha

“Don’t read into it. I usually sell my textbooks, but the novels don’t bring much.”

I quit going to the library and took my work to a coffee shop because I thought it would be weird to see him again. A week into my new routine I was rereading “Tapka,” the first story in the collection, when I discovered a passage underlined in blue ink. In the margin it read: “I stopped here, when I understood what would happen to the dog.” I flipped through the rest of the book searching for more blue ink. There wasn’t much. In the white space on the final page of “An Animal to the Memory,” he had scrawled: “Write the story only you can tell.”

I shoved the book in my bag and walked to the diner where I took a seat on a vinyl stool at the counter and drank three cups of coffee while I waited for him to come out of the kitchen.

“I missed you at the library.”

I held up the book. “Some asshole gave me his copy.”

“Some asshole?”

“You never said your name.”

“Brandon.”

I tried it out. It had a boy band vibe I didn’t like. “Nah. You’re a Berman.”

“What does that make you? Natasha?”

“Christ, I hope not. Pretty sure she’s my roommate. You should meet her. We’re having a party for her birthday.”

LYNDA WILLIAMS // 18

The party was being held at a loft in Yorkville. It was hosted by one of Amber’s wealthier conquests, so there was champagne and the coke was inhaled off marble countertops. I was pretty sure it was going to end in some type of orgy. Berman was the only thing that made attending this type of event tolerable. If nothing else, he made intelligent conversation.

Amber was bounced from knee to knee like a baby, flaunting her red dress without underwear with a carelessness that made me question whether I was actually a sex-positive feminist.

I caught him staring. “You want to fuck her?”

He didn’t answer.

“It’s okay. Most men do.”

He frowned. “Want to?”

“No, fuck her. You can say the word.”

“I don’t have to. You say it enough for both of us.”

For a second, I thought he was going to kiss me. Instead, someone backed into him and he spilled his Grasshopper on my shirt.

“Jesus, Erin. Do you ever wear a bra?”

“In service of the patriarchy?”

“No, like a public service.”

He set his empty glass on the ledge and surprised me by handing over the pearl snap he wore over his T-shirt.

“You know you’re never getting this back.”

He draped an arm over my shoulders. “We’ll see about that.”

Not unless you take it off me

A few shots and a few hours later, he did.

I brought him back to the closet and when he turned on the light, he discovered how I slept. The bed was unmade and at the bottom there was an arrangement of books, legal pads, index cards, highlighters, and pens. He cleared the mattress by giving the sheet one swift yank.

In the morning, I resumed my work while he slept. When I looked up from my legal pad, he was watching me.

“So why do you keep reading this story?”

“It’s for my senior thesis. It’s creative. I’m rewriting the narrative from her perspective.”

He reached for the pad, but I swatted his hand away.

“How far along are you?”

“So far it’s mostly research. I’m trying to emulate the voice and form—the opening paragraph with the short declarative sentences, the deadpan dialogue, and that final arresting image.”

“But if it’s her story, shouldn’t the voice be different?”

“Sure. That will come through in the content. I’m just talking about the form.”

He nodded but didn’t seem convinced. I half expected him to say that form is content when he asked, “What’s it called?”

I sighed. “Berman.”

“Yeah?”

“Berman. That’s the title.”

His face broke into a grin. “So it’s about me?”

“Fuck off. It’s a coincidence. I promise.”

“Sure, sure,” he said, sliding off my underwear.

I’d spent the previous summer planting trees and fending off mosquitoes in Northern BC, so my primary goal that year was air-conditioning, and I found it as a file clerk for Kirkpatrick and Associates. It meant wearing a bra and stockings under my professional garb, and next to having sex, Berman liked nothing better than watching me get dressed as I complained about the oppressive significance of each item before putting it on. It was backwards porn and no sooner than I zipped my skirt he’d be driving me into the wall and pushing the fabric over my hips. Nothing says professional like showing up for work with tousled hair and toting your underwear in your purse.

There wasn’t much. In the white space on the final page of “An Animal to the Memory,” he had scrawled: “Write the story only you can tell.”

We fell into a routine. I brought my work to the diner and he brought his books to my bed. The only source of contention in our relationship was a spiral bound notebook devoted to my thesis. I wouldn’t let him read it. I’d copied the full story twice to pick up its rhythm and cadence. One day I left the closet to grab orange juice and returned to find he’d helped himself.

“That’s mine,” I said snatching it.

“Is it?”

Was Judas so casual?

“You can only go so far imitating another writer’s work. At some point you have to find your own voice.”

“I’m learning.”

“Learning or hiding?” He took the book from my hands, speaking more softly. “It’s not a prayer. You don’t have to recite it.”

LYNDA WILLIAMS // 19

I reached for the notebook, but he held it above my head.

“So that’s it. You’re jealous. You think I should be giving you head instead of practicing my craft?”

“Your craft? Pickling your brains in the holy water of David Bezmozgis isn’t practice. It’s procrastination. You could have written an entire book in the time you’ve spent on some dumb story about another writer’s character. You think you’re such a feminist, but all you’ve done since I met you is try to replicate some famous dude’s work.”

I almost interrupted to remind him Bezmozgis is Jewish, so the holy water wasn’t apt, but I didn’t get the chance. He shoved the notebook into my hands and left. But not without telling me I was a dick envier and the absolute worst.

He called twice afterward to apologize. I deleted the messages, and I was more annoyed than surprised when I ran into him a week later, leaving our apartment with his jeans half-zipped.

“How was it?”

He winced, as if I was the one hurting him. “Fuck off, Erin.”

It impressed me a little how he said the actual word. And when I think of Berman now, I like to believe I changed something in him, even if it was just a tiny aspect of his vocabulary. So what if I wasn’t his Natasha with my fingerprints on everything he went on to achieve? Berman didn’t alter the course of my life either. There was no murder. No new identity. I didn’t change schools, or clothes, or cities. I did change my sheets and my thesis—it became a critique of the portrayal of women in Bezmozgis’s work—and I graduated with honours. So maybe I do owe Berman something, but one final blow job behind the stacks at the library and a pitcher of draft would cover it. I have my own body of work now, full of Natashas and Bermans sparking off each other and living inside the minds of people I’ve never met. The characters you’re reading about don’t exist. Or maybe one summer they fucked a lot inside a closet to give you this.

SHANE NEILSON // 20

TheAmpersandReview.ca Reading for pleasure. Writing for everyone. ISSUE NO .6 OUT NOW! SUBSCRIPTIONS & BUNDLES AVAILABLE ONLINE INSIDE ANNICK MACASKILL • MEGHAN KEMP-GEE • LISA WHITTINGTON-HILL • MICHELLE BERRY MIEKE DE VRIES WHITNEY FRENCH SHANE NEILSON ADAM WILSON MATTHEW GWATHMEY SOPHIE JIN MARK TRUSCOTT CATHERINE OWEN KELSEY GILCHRIST SENKA STANKOVIC No. 6 Ampersand Review THE OF WRITING & PUBLISHING a conversation with CANISIA LUBRIN GETTING TO THE HEART OF THE THING

///

SHAUNA ANDREWS

TWO POEMS

THESE THINGS THAT HAPPEN NEVER HAPPENED AT ALL

tough bones, translucent teeth, pale with thin hair, greasy slight skin, just like me

when she was thirteen she thinks she maybe kissed a boy and when she did he held onto her face firm but soft and it thrilled her she could taste the pot smoke in his mouth and smell the urine rising from the back alley stoop they stood on she felt so small as he backed her into the corner he eclipsed her she could no longer see the light of the fairground when he pressed into her she felt his cold fingertips graze her bare abdomen as he slipped the hole of her jeans loose from its button it was then she broke away from his lips looked down gently took hold of his wrists and pushed him back it was then he began to laugh first softly then madly called her a slut and walked off shaking his head and she was left alone in the dark

in my dreams he was tall, and moved his arms wide skinny but strong clothes baggy and hanging from his wiry frame

he had experience a crackling voice *whiny, but not high pitched

|assertive, maybe to me anyways I believed him, believed in him|

we would traipse down the street and I’d feel safe, even at night only because he let me

and even though his fingers were long his body was warm, still a boy, crooked lips cloud-like complexion

and even now he exists somewhere in limbo waterbed waving leaving cricks in the necks oh yes, of even us young ones

SHAUNA ANDREWS // 21

TO KNOW THEM

I.

In high school my best friend had an older brother.

His name was_____and he died after she and I stopped being friends (we drifted apart. You know how it is).

When I heard_____passed away, on his couch at 31 lips blue, gauzy white foam escaping his mouth (I know this because they said in the newspaper) I felt sick.

I pictured_____back then head shaved eyelashes long under a hooded gaze teenage body tall and soft and draped in oversized cotton kind to me, but sad, always sad. Eyes sad. Shoulders sad.

When I saw my old friend at a bar a few months later I told her over the blaring music that I was sorry to hear about_____. She said, it’s okay (but I don’t believe her).

II.

My co-worker’s boyfriend died this year.

He’d been laying there for hours when she found him (it happened sometime in the night).

I’d served_____a burger and a beer once or twice but I didn’t know him. I knew her.

She didn’t know he was using. He was 32.

III.

_____was my mom’s cousin I liked him even though his presence was alarming. Not because he was loud or unusual or bold (although he was all of those things) but because he always needed a wash. And a haircut.

Wore torn shoes. Was missing a finger.

_____died alone in a motel room in another province a couple years ago. He was old but not old enough to die. 56 isn’t old enough to die.

_____left behind our family and a son with FAS whose mom is also dead, but when we talk about we try to laugh because _____has a legacy so full of good stories because he was funny. And dodgy. And fearless. And loved.

SHAUNA ANDREWS // 22

This week my partner’s nephew,_____ died. The two of them were close in age and grew up like brothers.

The drugs stopped his heart at 33 (he would have been 34 at the end of the month).

Everyone thought_____was getting better— his whole family (it’s a big family) and his friends.

My partner is angry and sad and I am sad for everyone.

When my niece’s mother died her mom was 35. My niece was 16. It was 2018.

_____had a tall frame that was found early in the morning on the kitchen floor. She spent four days in a coma before they said, “you have to let her go.”

_____loved art and her daughter but didn’t know how to do it anymore.

The machines made her look like she was breathing even though she had left a long time ago. No matter

that we expected death to arrive in this form to take her.

Real life is different.

Seeing_____laying still you could finally grasp her youth her olive skin her open sores her chipped nail paint.

SHAUNA ANDREWS // 23

IV.

V.

SHANE NEILSON

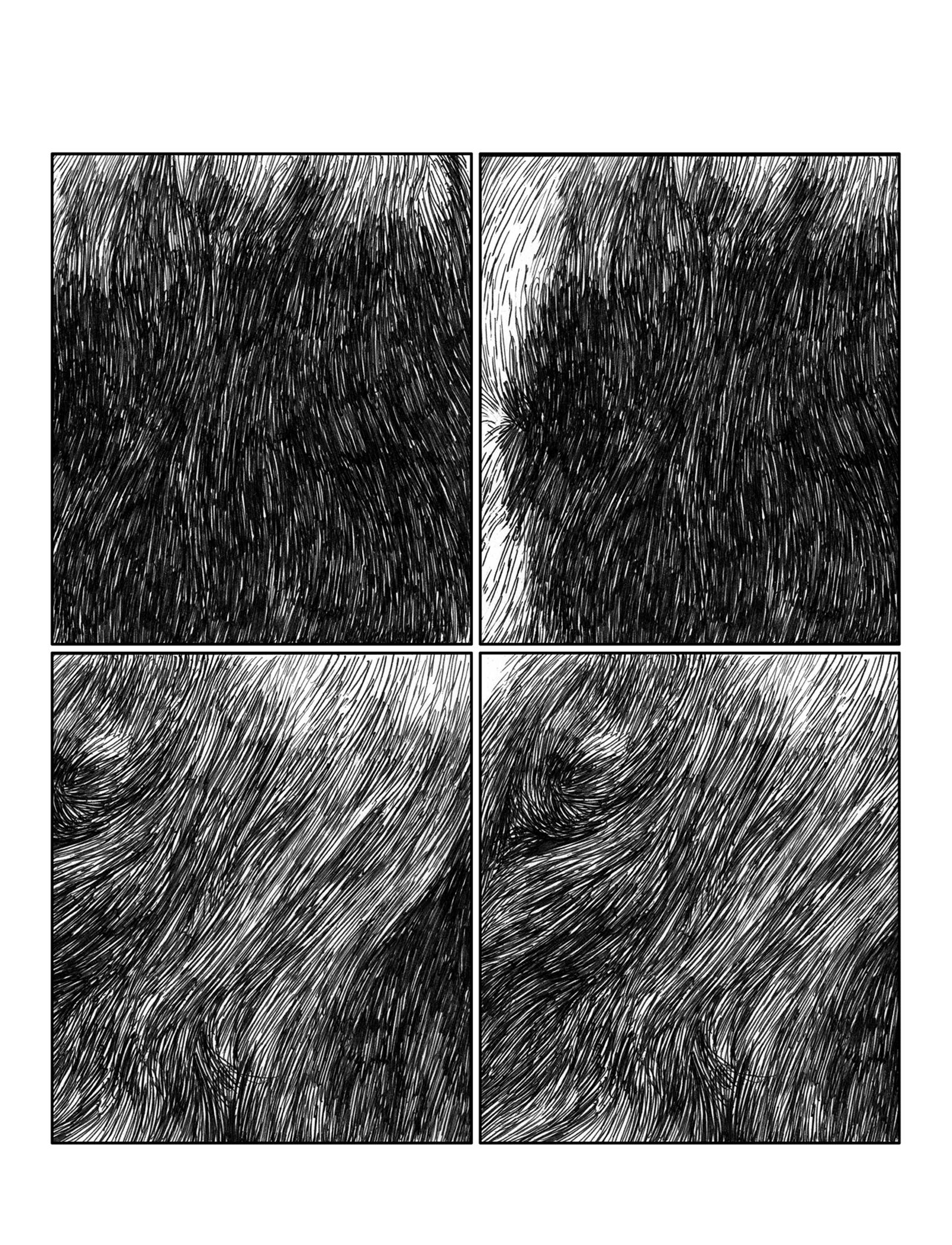

ROADSIDE ATTRACTION, 2020 | STEVEN BECKLY

Image courtesy of the artist.

ROADSIDE ATTRACTION, 2020 | STEVEN BECKLY

Image courtesy of the artist.

In the Nova Scotia Hospital, I am named bad

even though I want to die, want to jump from a height, and, just a week later, will do exactly that. The psychiatric staff consider me merely parasuicidal and write in the chart zestfully of my charged interactions with staff, my disdainful attitude and small resistances, concluding in each of their notes:

Cluster B.

This lyric essay is not a critique of the professional opinions diagnosing a personality disorder, nor is it a celebration of the supposed disorder itself as it was/is applied to me, for I have a number of concerns about its name, history, and the reception of that diagnosis in medical culture, not to mention its applicability in my own case—a physician. Instead, this essay is an attempt to understand how we describe people who are suffering and how we might care for them better.

I have no memory of being on the ground. I am told later by my wife that circumstances would have been slightly different, say, having hit the pavement a little to the left, where a pole of metal rose. But my wife pulled me back by my belt, and then my arms. Had she not, perhaps I would have gotten my wish.

Do I sound like an embittered member of the psychiatric survivor movement? I hope not, because the overlap between borderline personality disorder (or BPD, existing in the proverbial Cluster B of the DSMV, short form for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition) and bipolar disorder is significant, making accurate diagnosis very difficult. Not only do 15 percent of borderline personality disorder patients get rediagnosed later as having bipolar disorder, but the expression of symptoms when unwell can be remarkably similar. Think of the staff at the Nova Scotia Hospital encountering two fractionally different shades of red. Say, candy and rose. Some take one look at rose, and, based on their own sweet tooth, they write down

candy

in the chart. Then they see candy all day, every day, because they have decided:

candy.

I try to throw myself through the glass of the eighth floor of a different hospital.

The key component of bipolar disorder is periods of highs and lows of affect that are outside the norms of variability. The key component of borderline personality disorder is an unstable mood. They share mood instability as their pathognomonic symptom. A patient can have both. I have routinely encountered patients whom I have suspected had borderline personality disorder, yet there was a tinge, a nag, that there was another underlying factor for their presentation. I have also frequently seen patients with bipolar disorder who do less well on medication, whom I suspect (based on taking a careful history of their childhood) of having concurrent borderline personality disorder.

An orderly from the emergency department pulls me back from a concrete rampart where I would have fallen over forty feet.

The problem at the bottom is twofold. First, the similarities and borderblurs between these two diagnoses; second, the fact that both diagnoses are more likely to occur if a child has a traumatic upbringing. Children who face adverse events develop a certain stance to the world, an oppositional and reactive one, often because they were never heard or soothed during their development. What normies might call

drama

in the dysregulated acquaintance is not the acquaintance’s perpetual dress rehearsal for life, a simulated scene the sufferer casts themselves (and everyone around them) in.

Drama is, for some severely traumatized people, the only way to get through the day because the minor excitements of the present, no matter how self-created, pull the self away from the real pain of the past.

SHANE NEILSON // 25

From 2004–2006, I unmake the makings of my Cluster B status, the judgement of self, I agree, is bad—

because I am bad,

I am repulsive, no one can love me—by meeting with Dr. J once a week for an hour or two, depending on his availability and the progress made in the moment. Rumpled, with tousled hair and a huge paunch, always wearing a blue dress shirt that could use one more button done up on the neck, the doctor provides simple medicine: he listens. I talk. Like most bad

people, I have few others in my life who will listen, and those who do quickly become overwhelmed. Negativity builds into a whirlwind, throwing everyone out of proximity. When I complete a sentence or two in his office in the Homewood, he laughs and says, Really? He means, Why are you looking upon this so negatively? Why are you being so hard on yourself? Maybe what happened was just a step along the way, a lesson. Of course, I resist, thinking, No way. I’m bad.

You’re wrong. What’s true is that I am bad.

To the layperson, the term “borderline” connotes a tendency to tip into psychosis, given the right conditions. Just push a borderline a bit too hard, and they’ll behave crazy.

As it happens, this impression has both a substantiating historical basis as well as contemporary, real-world validation. In terms of history, the name was coined by Adolph Stern, an American psychoanalyst, who in 1938 built on Freud’s conception of both “neurosis” and “psychosis” to synthesize a condition felt to be on the border between both. From the beginning, the diagnosis—quite different than the one that evolved to the present day—was felt to be rooted in a traumatic childhood. Stern hypothesized that “it is not that these patients are exposed to specific

experiences, sexual or otherwise, which are in themselves of a necessarily traumatic nature, but that their environment is […] so traumatic that when they are exposed to such experiences they react to them as if they were traumatic.” In a very perceptive moment, Stern identified poor parental attachment and modelling in both mothers and fathers as a contributor to the development of BPD. In a very real way, the disorder is characterized by neglect, intermittent to absent attention, a severely critical and shaming parenting style, and serial rejections of the child. Today, a more complex formulation reigns: a genetic predisposition (in twin studies, BPD is highly heritable) in conjunction with a traumatic environment (including the aforementioned parenting deficiencies) is thought to create the condition. Since Stern, the diagnosis has undergone many reconceptions. Initially, these revisions concerned the element of psychosis, and the thinking was that BPD was somehow a relative of schizophrenia. As more time passed, the diagnosis was refined in terms of behavioural description, and the core traits of what we know as the diagnosis today were described. Of particular interest is the fact that the most significant recent change to the diagnosis in the DSM-IV in 1994 involved the addition of the following criteria: the presence of transient, stressrelated paranoid ideation or severe dissociative symptoms In this way, history closes a loop and the border blurs once again between neurosis and psychosis. The preservation of the name to the present day is an accident of history, a name echoing forward to the present even though it contains little (but not quite zero) descriptive usage. A better name is “emotion regulation disorder” because it accurately conveys the central symptom of the condition and is less pathologizing. Surely everyone can be a little emotional; what is unusual about going to the bar and getting hammered after being informed one’s wife wants a divorce? That one’s partner has just died in a car crash? Everyone seems susceptible under that kind of signalling rhetoric. Whereas people on the

borderline are scary, just a hairsbreadth away from pulling a trigger.

Dr. J doesn’t adopt a posture of certainty. Rather, he models openness. I start to question not only how I am bad, but if I am bad

SHANE NEILSON // 26

at all. If I utter such doubts aloud—like, I wonder if I just did the best I could, under the circumstances?—he smiles and says, It’s possible, isn’t it?

The story of Dr. Marsha Linehan, the creator of Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT), is quite well known in psychiatric circles. The short version is this: Linehan often received acute psychiatric care when in distress with BPD, including electroconvulsive therapy and carceral care. Her many negative encounters with physicians—invalidating, pathologizing, and harmful—spurred her to become a clinical psychologist to study the condition and develop a therapy for what was felt, at that point, to be an untreatable condition.

Once, when an exchange is particularly charged, when his gently arch and skeptical attitude isn’t enough to dampen my affect, Dr. J says, Imagine you have a friend who is going through the same thing as you—exactly the same. He had the same childhood. He has the same mental illness. He’s on the same kind of medication. He has a wife and a child, and he’s not working either, because he’s so unwell. What would you say to him if he were in your situation? Me: I don’t know. I never know what to do. Dr. J: Okay. Let’s start at the beginning. What’s his name? Me: I don’t know. I don’t have any good friends. Dr. J: Make one up. You choose. Feeling disdainful of the idea of imagining a friend who never was, and who would never be, I say, Ernesto! Laughing, he says, Okay. What do you say to Ernesto? He’s really hurting. Words come to me because for some reason I naturally care for this imaginary being, just like I care for all beings other than myself. Why should they suffer? Why should anyone suffer? Why must it be that they are in pain? Surely something could help them, a word, an action? I say, Ernesto, I know that it’s hard now but it … will get better? I speak uncertainly, speculatively. That’s not bad, he says.

My most symptomatic BPD patients despise emergency departments. The reason is simple. Healthcare workers in such places are negatively predisposed to chronic mental problems that require intensive, long-term assistance. They tend to be disgusted by self-harm burns and lacerations. They feel like the parasuicidal waste their time, or worse: one study found that 89 percent of psychiatric nurses described BPD patients as manipulative.

Perhaps the most dear injury comes not with outrageous disdain or criticism, but with the all-toocommon endemic invalidation: BPD patients do not feel they are being heard or believed when they seek care. Once again, reenacting the processes of childhood, authority figures neglect, ignore, and minimize those who appear before them. History is always closing its own loop on the person with BPD, the past and present as one.

Each week, Dr. J parents me. How many bad

people are lucky enough to get this kind of care?Essentialized, Dialectical Behaviour Therapy is a kind of self-parenting program. Consider, if you will, the signal moment Linehan personally identifies as the genesis of her idea for DBT. She is in a small Catholic church in Chicago, kneeling on a tussock, and these are her words: “looking up at the cross … the whole place became gold—and suddenly I felt something coming toward me … It was this shimmering experience, and I just ran back to my room and said, ‘I love myself.’ It was the first time I remembered talking to myself in the first person. I felt transformed.” I hasten to add that Linehan didn’t come to God here; instead, the church enabled her to conceive of herself as worthy of love. At long last, Linehan realized she needed to approach herself with compassion.

Similar kinds of childhoods create similar kinds of futures. What we needed, way back when, was parenting. And truth be told, what we need now is the same.

Until relatively recently, Linehan attended psychiatric conferences as speaker and workshop leader, where—and I love this—she would be quite testy with psychiatrists.

Am I truly bad?

Or do I get mixed manic, the kind of high that wants to destroy everything in its path: relationships, a career, finances—all love. I try to respond to myself like a parent would, since I have to parent myself now—in a

SHANE NEILSON // 27

way, I’ve always had to. I say, “Things were really difficult, but you did a lot of work and now you know to be kind to yourself. What would you say to Ernesto?” I respond to myself, “There, there, Ernesto. Everything will be okay.”

The risk of suicidality in borderline personality disorder is 43.7 percent. The risk of suicidality in bipolar disorder is 30 percent. Suicidality risk in comorbid borderline personality disorder and bipolar disorder is 44.7 percent. Seventy-five percent of BPD patients attempt suicide in their life. Ten percent actually complete the act. Almost 20 percent of bipolar patients die by suicide.

Everything will be okay.

Appearing regularly in the psych-nurse notes is an expressed worry about the possibility of violence. Several caregivers speculate whether I have ever struck my wife or daughter. I express no willingness to harm anyone. I am merely sad, but the esteemed caregivers feel a need to confirm that I am not harming my family. A record of an interview with my wife verifies that I am not harming her.