The hobarT and William SmiTh CollegeS and Union College ParTnerShiP for global edUCaTion

The hobarT and William SmiTh CollegeS and Union College ParTnerShiP for global edUCaTion

Aleph: a journal of global perspectives

a journal of global perspectives

15

The

15

Aleph The

the Aleph a journal of global perspectives

Volume XV, 2022

Making Chess Pieces, Transylvania, Romania [Rachel Meller]

Making Chess Pieces, Transylvania, Romania [Rachel Meller]

The Aleph: a journal of global perspectives

Volume XV, 2022

Thomas D’Agostino, Editor-in-Chief

Jennifer O’Neil, Artistic Director

McKayla Okoniewski, Assistant Editor

ISSN 1937-0474

Stories in The Aleph are set in Gentium, designed by Victor Gaultney and adopted by SIL International, an organization working to document thousands of dying ethnic languages, many of which are written in modified Latin scripts. Most digital fonts do not include these extended alphabets and therefore millions of people are shut out of the publishing community. Gentium is an attempt to meet this challenge. The name is Latin for belonging to the nations.

© 2022 Hobart and William Smith Colleges and Union College Partnership for Global Education

Thomas D’Agostino, Executive Director Trinity Hall, 3rd Floor Hobart and William Smith Colleges

Geneva, New York 14456 (315) 781-3307

Cover Photo Credits:

Front Cover: Aurora Borealis, Abisko, Sweden [Mike Goulart], Fu Tei Resident, Hong Kong [Jonah Salita]

Inside Front Cover: Mother & Son with Motorbike, Vietnam [Olivia Bennett]

Inside Back Cover: Pura Lempuyang Worshippers, Bali, Indonesia [Jonah Salita]

Back Cover: Dance in Front of San Pietro, Tuscania, Italy [Susie Register], Fans Celebrating a Goal, Brøndbyvester, Denmark [Joshua Wasserman]

ABOUT THE ALEPH

The first edition of The Aleph: a journal of perspectives was published in 2002 as part of the Partnership for Global Education initiative between Hobart and William Smith Colleges and Union College. Since its inception, the journal has served to reflect the wealth of international experience among students at our respective institutions, and we are pleased to have extended this opportunity to students across the New York Six Liberal Arts Consortium.

The journal takes its name from the 1945 short story “The Aleph” by Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges. In the story, the narrator (a writer) comes upon “a small iridescent sphere of almost unbearable brilliance” in which “without admixture or confusion, all the places of the world, seen from every angle, coexist.” Through this encounter with the mystical Aleph, he is able to see all things from all perspectives – yet he despairs of the daunting task of trying to convey the enormity of this experience to his readers.

Our students face much the same challenge when they return from abroad: after crossing borders and cultures, navigating societies different from their own in which they are exposed to new values and perspectives, how can they make sense of it all? How can they adequately convey the significance of the experience to this who did not share it?

The Aleph: a journal of perspectives was created to address this dilemma. It provides a space for reflection, analysis, and dialogue that benefits contributors and readers alike. The pieces, both written and visual, offer insight into what captivates, challenges, and inspires our students – and through these words and images we learn about the people and places they encounter, we see how they change along the way, and we are exposed to “all the places of the world, seen from every angle.”

Table of Contents

Crossings (p. 6)

I. A New Year in a New Place (Matt Simkowitz) II. Language isn’t the Only Way to Communicate (Matthew Fox) III. Following the Flow of the Forecast (Sami Foulk) IV. Panopticon (Jack McCarthy)

V. 701 Cumberland Street (Brooke Kelly) VI. Finding Home in Two Cultures (Emma Consoli)

From My Journal (p. 29)

I. Truths on the Tram (Marion Miller)

Moments (p. 42)

I. Bad Urach: A Week in the Mountains (Elizabeth Fajardo) II. Do You Regret It? (Margaret McKean) III. Bergen-Belsen Camp Reflection (Cynthia Kellett) IV. Ancestral Recall (Adrian Shin)

V. Ode to the BVG (Abbey Frederick)

Engagement (p. 78)

I. Local Coffee Shops in Berlin (Abbey Frederick) II. In Dialogue in Durban, South Africa (Carrie Baker) III. Una Carta (Kelsi Morasse)

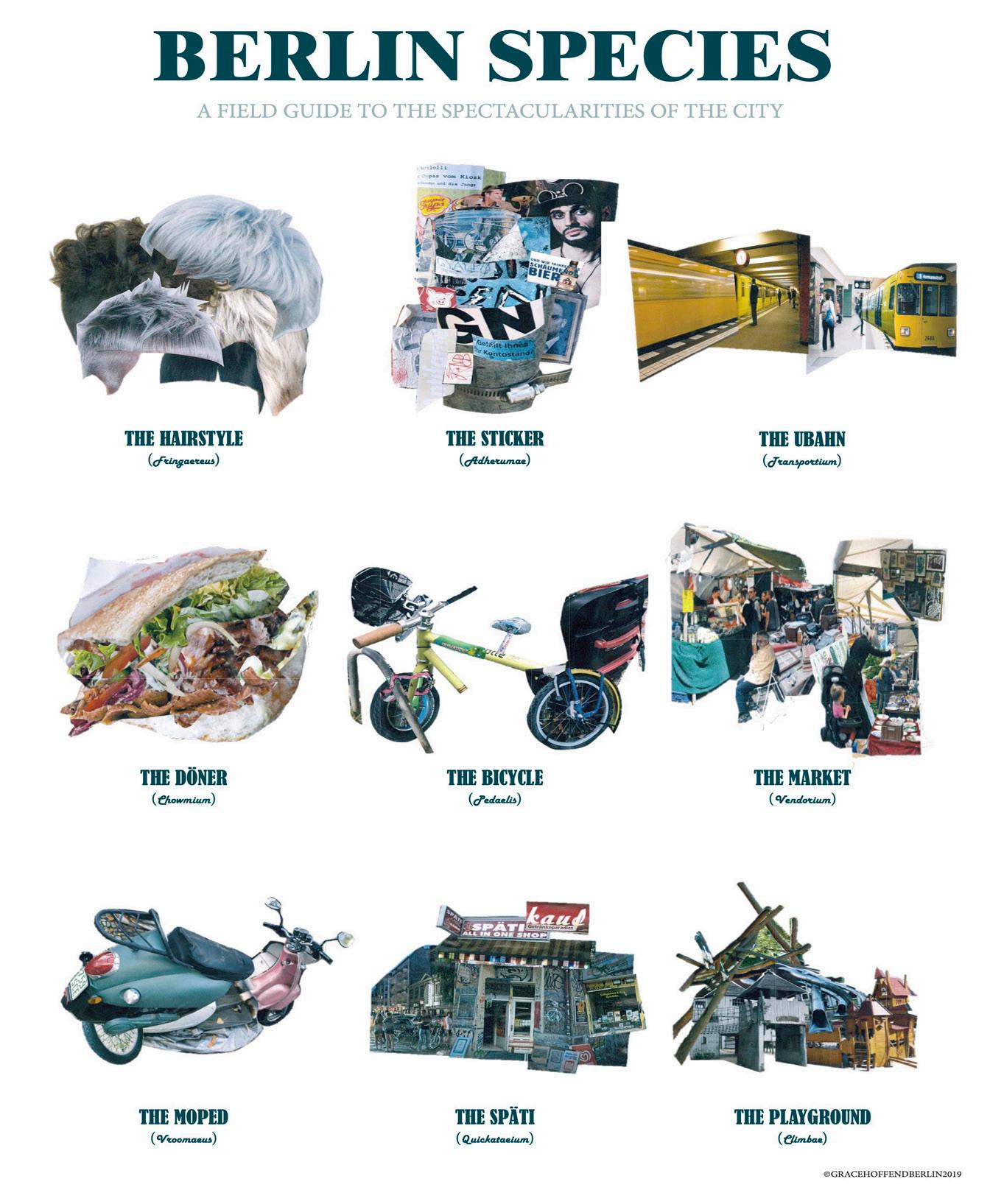

IV. Onsdagssneglen: a recipe for home (Sarah Walters) V. The Color Black is Vibrant in Berlin (Grace Hoffend) VI. An afternoon with a local Athenian (Barbara Kasomenakis)

Verse & Vision (p. 109)

I. Quays (Molly Englert) II. Left Her Home, Gained Her Sight (Davida Eyam-Ozung) III. LGB(t)Q in Berlin (Gianna Gonzalez)

Lessons (p. 114)

I. We Don’t Need a Taxi! (Elizabeth Anderson) II. Home is Where the Hygge is (Morgan Hamre) III. Walking on Ice (Alexandra Curtis) IV. The Window (Madeline Conroy) V. Within Jinja, Uganda (Lilly Bianchi) VI. Gentrifying Structures (Bramm Watkin) VII. Kleingärten (Ruby Williams)

Portraits (p. 145)

I. Superwoman (Aliya Brown) II. Bean Man and the Start of it All (Lauren Downes) III. Kurt Schwitters: significant scraps (Ruby Williams) IV. Sozi36 (Lauren Downes)

15

Baturi Temple, Bali, Indonesia [Alexa Puleio]

A New Year in a New Place: Experiencing My Own Culture in a Different Language

I am a Jew. Throughout my life, and especially as a college student, one of my strongest identifiers, both in my own eyes and the eyes of others, is my Jewish heritage and culture. My family shares a common narrative with many other North American Jews - my ancestors fled violence and persecution in Eastern Europe in the early 20th century, arrived in New York City, and within a single generation the legacy of the shtetl (a Yiddish word to describe the poor villages in which Jews were made to live under the Russian Empire) was mostly overwritten. My family became, more or less, a family of assimilated English-speaking Americans. Regardless, some of the religious and cultural practices remained strong in my family. Personally, I continue to celebrate the important Jewish holidays every year as my ancestors did, fast on Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement), attend occasional Shabbat services, and involve myself in Jewish life wherever and whenever I can.

Because of the nature of the lunar calendar (and Jewish tradition), most of the important Jewish holidays fall in the...fall! As a result, for me, the months of September and October tend to be filled with tradition, reflection, and celebration, as well as spending significant time with family. So, naturally, I was completely thrown off when the Jewish holidays arrived not only while I was experiencing the Southern Hemisphere spring, but also while I was more than 5,000 miles from my family in Argentina, a country where the Jewish community was very different from the one I knew well. On top of that, I had to observe the holidays not in English or Hebrew, but in Spanish! While I was lucky to be in a country with one of the largest observant Jewish populations outside of the United States and Israel,

6 The Aleph Crossings I

I was thoroughly confused and nervous to see how my cultural and religious practices would (literally) translate into the context of this completely unfamiliar culture. However, while I initially I thought my being in South America for the Jewish holidays would be an inconvenience, it actually ended up providing a brand new perspective for me, as well as an appreciation for the wide-reaching and persevering nature of my culture.

Specifically, it was the experience of celebrating Rosh Hashanah (lunar New Year) with my host family that truly showed me the ability of my people to congregate and practice our religion and culture in any environment. My host sister’s father (who is no longer married to my host mother, but is still close to my host family) is a practicing Jew, and comes from a long line of Polish and Russian Jews who emigrated to Argentina during the early to mid-20th century. His father, who was present at the celebration, was born in Poland and fled ethno-religious persecution with his parents at a very young age. It was a story not too different from my own family’s story. Throughout dinner, I helped them prepare vareniki, round challah, and manzana y miel (apples and honey). We said all the prayers my family and community says, albeit with a different kind of pronunciation pattern. We even ate the traditional foods that my family prepares, such as brisket, gefilte fish, and blintzes. The experience was surreal yet profoundly touching - my culture and my people were waiting for me wherever I went.

What resonated with me the most about that Rosh Hashanah dinner was the way in which all the different members of the family greeted each other. It was nearly the same as how my family greets each other--loudly, sarcastically, and with a somewhat deprecating but not overly cruel remark regarding one or the other party’s appearance. The only glaring difference was that instead of loud, sarcastic Brooklyn Jewish yelling, I was listening to purely loud, sarcastic porteño exclamations.

a journal of global perspectives 7

It was surreal to experience my own exuberant culture, performing the same religious rituals, in a different language. At the same time, it was profoundly comforting. As I sat in the backseat of my host family’s car after dinner, driving through the streets of Villa Crespo, I felt present and safe and happy in the moment. I knew that the rest of the semester would be similar to that night: full of love, acceptance, and happiness, both as a temporary member of my host family, and as a Jew in Argentina.

-Matt Simkowitz

Street Synagogue, Budapest, Hungary [Matthew Fox]

8 The Aleph

Dohany

Language isn’t the Only Way to Communicate

I studied in Freiburg, Germany in the Spring of 2018. During my break I went to Budapest and while there I visited the largest temple in Europe, the Dohany Street Synagogue.

Designed by Ludwig Förster, the temple was built between 1854 and 1859 and has a distinctive architectural style. I was in Budapest during Passover and after seeing this magnificent temple, unlike any other I have ever seen, I wanted to go inside. I found out there was a service the next day and I planned to attend, not really knowing what to expect.

The next day, I arrived at the temple early and a security guard let me in and showed me where to go. I walked into the sanctuary, the main hall where people pray and where the Torah is kept, and I was immediately greeted by an older Hungarian man. He said some words to me in Hungarian and when I replied that I couldn’t speak Hungarian he smiled and continued to the front of the sanctuary. Eventually more people filed into the temple and as they came in, they went to pick up a prayer book from the front and then sat down. Some would smile at me and say something in Hungarian and I would smile back and say hi. Following the others, I went to pick up a prayer book and as I opened the cover I saw the book was more than 100 years old. I was shocked that the temple had such special prayer books like this for anyone to use.

As I took the prayer book and sat down, the service started. It was so surreal to hear familiar Hebrew words but with a different accent, something I was not expecting. I was sitting alone when the service started but people in the temple saw this and walked over to sit next to me. Here I was in a foreign temple, unable to talk to anyone in my own language, yet a whole community was coming to sit with

a journal of global perspectives 9

Crossings II

me. It was an unforgettable moment and one which really showed that language is not the only way in which people communicate.

Throughout the service I marveled at the magnificent surroundings. As I listened to the prayers, I joined in with the ones I recognized and read through the prayer book, thinking of the history associated with it and wondering how it had survived over 100 years. Although I was in this temple and didn’t know a single person, I felt that I had a connection to everyone through our shared prayers. As the service ended, the people returned their prayer books and several smiled at me once again. I returned the smile and realized that even though we could not understand each other with words, we understood each other with our expressions and emotions. I went to the temple not knowing what to expect and ended up feeling a sense of community which will stay with me forever.

-Matthew Fox

Remote Beach, Edinburgh, Scotland [Kaitlin Hunt]

Remote Beach, Edinburgh, Scotland [Kaitlin Hunt]

Following the Flow of the Forecast

Once again, I was packing my backpack and hopping on another train to Portugal - but this time with my sights set on Peniche. Although I was studying at the University of Seville in Spain, I had convinced two of my friends to come along with me for the weekend to witness the 2019 Rip Curl Pro surfing event that was being held in Peniche, Portugal, the 9th stop out of the 10 stop World Surf League Championship Tour. Just a month before, I had been watching online as my idols competed on the coast of France, and so when it dawned on me that I was going to be watching from the beach this time, I was euphoric.

After speaking Spanish every day back in Seville, I expected I would arrive in Portugal and be speaking in the universal language of English. That was not entirely the case. Little did I know, I would be making home in a hostel with a group of die-hard Brazilian fans who traveled to watch the event and catch some surf. I have been in love with the sport since I first started surfing seven years ago, but for many of the people staying at the hostel, surfing had been a part of their lives for as long as they could remember. Some of our Brazilian friends, such as Natalie, Richie, and Mo, were multilingual and our language of choice alternated between Spanish and English.

In the United States, there is a long-standing relationship between social class and language. English is certainly the accepted language and any other language is frowned upon, unless spoken by an elitist. Whereas in that hostel living room on Supertubos Beach, a variety of languages, including Portuguese, Spanish, English, and even German, were spoken with a real appreciation for diversity. Coming from a country that discriminates immensely based on cultural difference, I was enchanted by the atmosphere of a room

a journal of global perspectives 11 Crossings III

filled with a spirit for human connectedness. Three Americans were learning more and more about Brazilian, Portuguese, and even Japanese culture (there was a boy who traveled solo all the way from Japan just to watch the World Surf Tour event, as well as to score his own waves on the lay days). I believe my friends and I were the only group staying at the hostel - the rest of the people were traveling solo. Yet regardless of how people arrived, there was a common practice of respect and generosity, similar to a family dynamic.

Housemate at Surf Competition, Portugal [Sami Foulk] Surfboard on Bed, Portugal [Sami Foulk]

In addition to witnessing Brazilians cook up a storm in the kitchen or jam out for hours, I learned a thing or two about Brazilian hospitality. Going into the weekend, I assumed that my two friends and I would be watching the event alone. I could not have been more wrong. On the first morning of the competition, while everyone was buzzing around trying to cook, take a shower, and pack for the beach, we Americans were constantly included in the plans for the day.

A group of roughly ten of us ended up spending the entire Sunday at the beach watching the competition. If it wasn’t for our friends telling us various facts about the different Brazilian surfers, my attention would have been focused mainly on the American and Australian surfers that I had been following for years. I would have assumed that every Brazilian fan would generally support every Brazilian surfer, but I learned that the region a surfer is from plays a huge role in their fan base. However, it is safe to say that the Brazilians that showed up to Supertubos Beach that weekend (who comprised a large proportion of the crowd) all erupted with cheers and chants when Brazilian surfer Italo Ferreira clutched the first-place title. It appeared the entire crowd was synchronized in melody as they welcomed their winning idol to the beach.

Surfing is such a universal sport because of the welcoming and celebratory nature that the culture has established. A variety of languages, nationalities, ages, genders, and ways of living can be expressed through surfing in a manner that is unparalleled in many mainstream sports. The celebration of sports has always been something that has brought people together, and a mutual love for surfing brought me to befriend new people from an entirely different continent.

-Sami Foulk

a journal of global perspectives 13

14 The Aleph

Rice Fields, Vietnam [Olivia Bennett]

a journal of global perspectives 15

Panopticon

A Buddhist nun once told me, and I’m paraphrasing here, that we live in a world made of glass. That there is nothing we can do, no act so kind, no word so gentle, that will not crack or shatter this delicate place. That there is no way to avoid causing hurt. That if you think you are doing the right thing, then you are not thinking hard enough.

I have yet to find any reason not to believe her.

Have you heard the sound of the prayer wheels on the pier at Khecheopalri Lake? The sound of wood rolling against wood in the vast emptiness of that sacred, wish-fulfilling lake. The slow roll into a hollow crescendo. Like a storm. Like a distant storm in the vast and hollow expanse of my own country.

Have you heard the sound of wood rolling against wood in the empty corners of Bodh Gaya? That most sacred space in

Crossings IV

Sunset on Stadbroke Island, Australia [Amanda Bruha]

all the Buddhist world. Bodh Gaya, a place where religion runs thicker than water. Bodh Gaya, where the world unites to walk in endless circles. Take a walk from your hotel to the main temple. Close your eyes. Listen carefully. Do you hear the sound of wood rolling against wood? Is that the sound of the Khecheopalri prayer wheels? Has that sound drifted so far south?

Keep your eyes closed. You think you can just make out the sound. Like a distant storm in a hollow expanse.

Now open them. Look down.

Further down.

Look down at the beggar at your feet. Look at her legs, bent in ways legs should never be. Look down at the wooden platform she lies on. Look down at the wooden wheels that carry her to your feet.

Now look up and look away.

Listen to her cart roll, the wood of the wheels rolling against cart and ground. That terrible, rolling, rattling sound - empty and hollow and so, so vast.

Close your eyes. Listen carefully and transform the sound, make nectar from this poison. Shhh. That is the sound of prayer wheels on Khecheopalri Lake. The soft and rhythmic roll of sweet religion.

An old man once told me, and I’m quoting verbatim here, that the most important thing in life is to do the right thing. But I have sat at the edge of a lake while the sun set a thousand times and I have done many things. And not one of them was the right thing.

-Jack McCarthy

a journal of global perspectives 17

701 Cumberland Street

It was July 2nd, 2018, when I first spotted 701 Cumberland Street, tucked behind another student flat just off the main road. Having just arrived for the start of my semester abroad in Dunedin, New Zealand, I was eager but nervous as I walked down the path towards my new home. Growing up in Maine, I thought I was prepared for the adventurous, free-spirited way of life that made New Zealand so desirable. I had done my fair share of hiking and camping, and I have always loved the outdoors. I had learned to be in tune with my surroundings and to appreciate not only the view but the process of getting there. But what Maine had not prepared me for was the people who would make my semester abroad in New Zealand much more than just time spent in a new and unfamiliar place. My sense of belonging, I would come to realize, was rooted in 701 Cumberland Street.

The sounds of the busy, two-lane, one-way street were never muffled by the structure dividing us and flooded freely into our flat. Revving engines, squeaky breaks and blaring horns carried into my new home at all hours of the day and night. The aroma of fresh coffee merged with that of gasoline, stale alcohol and freshly baked bread. When the wind blew onshore, I could even smell the ocean, reminding me for a moment of home and summertime in Maine. There was a narrow pathway that ran along the side of our flat, connecting a university faculty parking lot to the street. With the university situated right across Cumberland, the path was used frequently. The window of my room opened directly over it, and I would grow to appreciate the voices of professors that woke me in the morning and drunk university students that lulled me to sleep at night.

Our flat was almost identical to the one separating it from the street, with gray cement exterior walls, green roof-

18 The Aleph Crossings V

ing and yellow window trim. To top it off, the two shared a fenced-in backyard and my bedroom window aligned perfectly with the one next door. The flats weren’t exactly what I had anticipated. There was no intricate lacework along the roof, no white pillars framing the door and no fence posts out front with our addresses, but they were quant in their own way.

There were five of us in total occupying 701 Cumberland: Jamie from California, Austin from Colorado, Hannah from Illinois, Lachie from Wellington, and then, of course, me. While four of us were from the United States, we had all attended different American universities and met for the first time upon arriving at 701. I would come to be closest with Jamie and Lachie, although collectively we constructed a family-like dynamic within the flat. After all, we shared a mutual love for the outdoors, good food and competitive beer pong. Looking back, it was the most ideal outcome for having been placed in university housing in a foreign country with four strangers.

Sitting Atop Lion Rock, Piha Beach, New Zealand [Madison McIntee]

Sitting Atop Lion Rock, Piha Beach, New Zealand [Madison McIntee]

Jamie and I became fast friends, bonding over rosé, trail runs, gossip, and the fact that we could actually fit into each other’s clothes. She stood at no more than five feet and three inches, with soft brown curls and deep brown eyes and a personality that was radiant. Hippy, preppy, and athletic all at once, she was the type of person who can fill a room with energy in a matter of seconds. Austin and Hannah were less outgoing, and loved to watch movies and stand-up comedy. Hannah was tall, with pin-straight strawberry blonde hair that fell just above her shoulders. She wore big, boxy glasses with thin frames, and spoke with just a tinge of a southern drawl. Also tall, Austin had short brown hair, plump, rosy cheeks and glasses that rested on a large, button nose. Both Austin and Hannah did hike, camp, and road trip just like the rest of us, but they proved to be a little less rugged and a little more content using the resources provided by the tourism industry.

Lachie was our Kiwi host, making him the only native New Zealander among us. He was tall and lean, with dark brown

Mount Brown Hut, Kokatahi, New Zealand [Brooke Kelly]

Mount Brown Hut, Kokatahi, New Zealand [Brooke Kelly]

hair and facial scruff. His glasses were always crooked and he had a smile that made you question whether he was just excited to see you or if he was up to something mischievous. At twenty-two, he was slightly older than the rest, and while home was technically on the North Island, Lachie had been occupying 701 for the past two semesters already. That meant that he had welcomed eight other international students before us, and it seemed pretty clear he had the basics of “hosting” all figured out. He gave us the simplified version of what we needed to know, and reminded us that although we had just arrived, the flat was now our home just as much as his. But for at least the first three weeks, I still felt like some kind of intruder, or a house guest who had overstayed their welcome.

I have always been one to rely heavily on routine. In preschool, my teacher started a seating rotation to help the class bond collectively. I cried every day for a week until they gave me a designated seat that I could return to each morning and depart from each afternoon. So naturally, even at age twenty, in a foreign country on the other side of the world, I fought to find a routine. This consisted, in part, of finding a practical time to wake up each morning in order to take a shower and get out of the flat before everyone else started roaming around. As much as I loved their company, the kitchen was barely big enough for two when we were drunk, let alone first thing in the morning. I decided on eight o’clock. Perfect, I thought. Except there was a problem: Lachie had also decided on eight o’clock. Every morning for the entire semester we fought for the first shower. It wasn’t a physical competition, or a verbal one. It was a silent battle of whose door opened mere seconds before the other. Damn it, I would think, hearing the creaking door hinge. Then I would start a twenty-minute timer, roll over, and go back to sleep. Sometimes, when I really couldn’t afford to wait, I would set my alarm for 7:57am, just enough time to be, quite literally, one step ahead of him. It happened even on Fridays, when most of the city’s

a journal of global perspectives 21

college-aged population was still passed out from the night before. While I got up to enjoy some “me time” over a latte, Lachie got up to go to class. Like many other Kiwi students at the university, Lachie was in the Health Science department, and understandably so.

Similar to America, professions in the Health Science field provide an avenue into high paying, reliable employment opportunities. However, the cost of higher education in New Zealand is much less expensive than in the US. It is also much less competitive; there is no cut-throat acceptance process, only University Entrance Requirements to ensure that students are academically prepared to begin the next level of education. Given the affordability of New Zealand universities and the quality of the education, it should have come as no surprise that Lachie and all of his friends were in Health Science. Affordable, quality education and the opportunity to enter almost any field? Of course, the most practical would be Health Sciences.

Sheep Gather Skittishly, Australia [Audrey Hunt]

Sheep Gather Skittishly, Australia [Audrey Hunt]

Although annual fees are much higher at St. Lawrence, my home university, students are still encouraged to follow their interests and passions, and not the associated paycheck. Until I came along, Lachie had never even met somebody who was studying English, but honestly, I couldn’t blame him.

Lachie wasn’t uptight - if anything he was the opposite. Which is why, I admit, it made me laugh to picture him taking even the most basic of medical exams. He was, after all, the type of person who forgot his dinner in the microwave and left homemade bread burning in the oven.

“Ah f*** me,” he would say in his thick New Zealand accent, running down to the kitchen. But after pulling the tray from the oven, he would tear the bread in two and eat it anyway.

“That’s three times this week, Lachie!” Jamie would say in thorough amusement and major concern. She gave us both that wide-eyed, sassy but expecting look of hers, and as she laughed, the gap between her front teeth would be revealed.

“No way, I swear!” Lachie would argue, but the smirk smeared across his face told us otherwise. Along with burning bread, Lachie also loved to ask questions and drink vodka mixed with “lemonade” – which, in America, we would call seltzer water – the topic of one (among many) humorous debates that took place within our flat. Debates that could never be won because they were not a matter of fact against fiction, but a matter of mere cultural difference.

I remember asking Lachie one day a complex question about Māori heritage, hoping for an equally complex explanation. Māori is the native culture and language of New Zealand and I had to enroll in an Introduction to

a journal of global perspectives 23

Māori Society course as part of our program. Lachie gave me a solid educated guess in response before clarifying something I had naively overlooked. “Just because I’m Kiwi doesn’t mean I’m Māori,” he told me. “I took Māori Society a couple of years ago, just like you.” And although he knew much more about the native New Zealand culture than me, he certainly didn’t know everything. “If I asked you about the American Indians,” he added, “how much could you tell me?”

“Close to nothing, honestly,” I admit. “I never thought about it in that way.”

He wasn’t being sassy - he was merely putting in perspective the absurdity of my question since only about 15% of the New Zealand population identify as Māori.

Because of his laid-back nature, it came as no surprise that Lachie was anything but a stickler when it came to rules. However, up on the bulletin board by the kitchen door, among fire safety pamphlets and the no smoking signs put up by the university, we had a color-coded chore wheel and each week we shifted clockwise one color. Lachie didn’t care that no one cleaned the bathroom or vacuumed the stairs –neither did he. But if you were on trash and recycling, you better be sure that all glass was cleaned out and put in the blue bin outside the front door, all paper and plastics went into the large gray bin with the yellow lid sitting out by the wooden gate, and you better drag them out to the curbside every Sunday night on alternating weeks. But it made sense Lachie was adamant that we recycle - all of New Zealand was doing so, too.

Lachie knew the recycling pick-up schedule like the back of his hand. “Today’s blue,” he would say, slinging his bag over his shoulder on the way to the library. “Whoever is on trash and recycling this week, don’t forget.” Walking to class on

24 The Aleph

Monday mornings, I would laugh, the entire street lined with overflowing bins, liquor and beer bottles spilling onto the sidewalk.

And so it went. In some ways, I had been right. Growing up in Maine had prepared me well for the free-spirited, spur-of-the-moment, adventurous nature of life in New Zealand. But it was 701 Cumberland Street that became my new home and the foundation of my sense of belonging in this foreign country. It was a bed to rest my head, a room to store my stuff, and a family of five to share stories, memories, and a few – or a few too many – drinks with on Wednesday nights. And that was enough.

Windsurfer at Takapuna Beach, New Zealand [Grace Stribling-Hough]

-Brooke Kelly

Windsurfer at Takapuna Beach, New Zealand [Grace Stribling-Hough]

-Brooke Kelly

Finding Home in Two Cultures

I am Italian-American. It is an identity that I have been proud of all my life. My dark features and my last name give it away pretty quickly, as does my incessant chatter about family traditions, constant research on Italy for school projects, and perpetual griping for “good Italian food.” Choosing to study abroad in Rome, therefore, was a no-brainer. I would get to live in the country which has guided my selfperception, curated my holiday menus, defined my religion, and, essentially, shaped my life from afar. Also, it didn’t hurt that Rome is one of the most historically significant cities in the world and that Italy is a Mecca of food, wine, art, and culture.

Living in “the motherland” has always been a dream, but being here now I am struck by how much I feel like an outsider. Yes, I am a novice Italian speaker which does drive a wedge between me and the locals. But while I was ItalianAmerican in the US, here I am American-Italian. This might only be a slight change in the linguistics, but it is a significant change in my identity, leaving me suspended between my ancestral and contemporary homelands. I am neither fully American nor fully Italian, and while my actions in the US flag me as the grandchild of immigrants, my actions in Italy scream American.

It is, honestly, disorienting and I feel as though I’ve lost myself in some ways. At home I was always able to reach back to my Italian roots and re-center, but here I am constantly grappling with wanting to immerse myself while secretly praying for familiarity. I do my best to avoid “touristy” places, looking for menus and websites which only offer versions in Italian, but I become overwhelmed when I try to read and most of the words are lost on me. I am quietly relieved when there is English to fall back on.

26 The Aleph Crossings VI

I’m positive that this is not a unique experience, and that others studying abroad feel this same type of panic and disorientation, but mine is magnified by a kind of guilt. I have put my Italian heritage on display for the past 20 years, yet I can’t speak the language. I have eaten many of the dishes, yet I struggle to identify them. My face may look Italian, but as soon as I open my mouth my true identity is learned. My heart bleeds for Italy but my body is squarely American. I am a foreigner.

It is disheartening to see my identity challenged in the harsh winter of culture shock. I am not one who typically cowers in the face of struggle, but it is difficult not to feel defeated when the culture I know best looks at me as though I am an “other.” While I do love being here, my apparent confidence is a façade. I feel the need to keep up an illusion of comfort and ease when around my peers, because my deepest fear is to be written off as an American tourist. I want to be more than that. I am more than that.

Colosseum, Rome, Italy [Danielle LaBare]

Colosseum, Rome, Italy [Danielle LaBare]

I see the light, though. Spring is coming slowly but surely as I become more comfortable with each passing day. With each stranger that recognizes my face in theirs, with each flowing conversation, I grow into my Roman self. It’s showing, too. I’ve started to get questions on the bus from nonRoman Italians asking me for directions, as if this were my city. I’ve caught strange looks from waiters and taxi drivers when I turn to my peers and start speaking English after conversing with them in Italian. I’ve been asked by shop owners and postal workers where I’m from and they’re shocked when I say the US. These are small victories for me.

I know that in my short time here I cannot become indistinguishable from those who are born and raised on this soil, but I am starting to fit, to blend, and it makes my heart soar. It is validation that I do belong – reassurance that I can be both Italian and American, not one before the other. I am finding my footing again, and with it, the confidence to grow. I am American and Italian, raised by both cultures, and I am from here. Cheers to la dolce vita.

-Emma Consoli

Sunrise over Manarola, Cinque Terre, Italy [Jenna Bredvik]

-Emma Consoli

Sunrise over Manarola, Cinque Terre, Italy [Jenna Bredvik]

Truths on the Tram

SEPT 12

The sun peeks out from behind the perpetual, hazy smog that is Prague on this Monday morning. I clutch my neatly scribbled directions in one hand and my study abroad welcome packet in the other as I frantically rush down the narrow street from my house to the tram stop. After arriving in Prague the night before, I have an uneasy gut from little sleep and unfamiliar food. I am surprised that my host parents expect me to navigate my way from my home in the suburbs to school eight kilometers away. The school is in the center of Prague, which I will only now be seeing in daylight for the first time. As I examine the instructions that I found on the kitchen table of an empty house earlier this morning, I don’t yet realize how second nature this route will become. Get on at Nadrazi Modrani, ride nine stops and get off at Vyton. As I near the Nadrazi Modrani tram station, I see a tram pulling away and my heart races, how could I have missed it!? But little do I know, Tram 17 comes every five minutes, and I am just early for my scheduled ride.

I must look like a newbie. I realize that I am the only one dressed in shorts on this brisk fall day, waiting for the tram with directions in hand and a frantic look on my face. The next tram pulls up within a few moments, its bright red body somehow shimmering despite the lack of sun. The tram sits on tracks like a railway train, but unlike a train it also has cables attaching the body to an overhead line. As I step on and am surrounded by a white noise created by the electric whir of the tram, I realize that my tentative, quiet nature fits right into the tram atmosphere. Although it is packed with commuters going to work, their briefcases on laps, books in hand, my stop is early enough along that

a journal of global perspectives 29 From My Journal I

there are open seats. I slide into a red plastic seat and as we take off, so does my relationship with the tram.

SEPT 20

School is out for the day and all the American students rush down the hill from the building that used to be a monastery, now our school, to catch their respective trams as quickly as possible. Nobody, Czech or American, likes to wait for a tram. I file onto an overly packed one, because nobody tells anyone when it’s probably too full for them to get on. Everyone has places to go and the mild discomfort of having someone’s elbow in your gut is better than waiting. I stand with Maggie, Maddie, and Sally, three quicklymade friends from my first week. I recognize many of the passengers who fill up the tram because most are fellow abroad students. As I look around I make eye contact with a boy from my Architecture class. He smiles. I grin and look away. Despite the fact that we have only been here for a couple weeks, we already know not to sit in the few open seats as they are reserved for the elderly. The Czech people respect their elders.

My friends and I are on a mission to explore the castle gardens at the end of the tramline. The stop where we get on is a segway for many people as one can either take the same tram continuing along the river towards the castle (as we will), another that crosses the river towards Zbrovská, or one that goes inland towards town. Behind me I can make out the top of the Basilica of St. Peter and St. Paul which sits a couple hundred feet up, next to my school building. To my left lies the river which accompanies Tram 17 from my house all the way to the castle. I can see over the river by way of the Charles Bridge that leads to Zborovská, where many student apartments are, as well as the mall with the fancy gym. If I lean to the left and put my cheek up to the window I can just make out Prague Castle in the distance, perched on top of the city, spires standing tall,

30 The Aleph

guarding over Prague like a hawk over its nest. I take it all in for the few moments while the tram is stopped at the station. As we start to move again, I see my favorite coffee shop speed by to the right and then the road that leads into the city through the old renaissance apartments. As I admire the view and chat with my new friends, packed like sardines in this tight space, a thought occurs to me about how easy it would be for someone’s hand to sneak into my cross-body bag or unzip my backpack. What a disruption of space that would be, in a peaceful place where even though the passengers are shoulder to shoulder we are in our own bubbles. I remember how my friend’s phone had been pickpocketed on the tram in the first week. And I am not about to get my phone stolen, hundreds of photos already filling up the storage from only a few weeks in Prague, and many to come. Not today. Not any day. I warn my friends and we make a mental note to keep our bags close at all times from there on out.

OCT 1

It is 4pm on a Monday and I am sitting in my Czech class. Today we are learning how to pronounce the Czech ř (pronounced like “rzj”), a sound that does not occur in any other language. The class (primarily female American students), in an attempt to stall and change the subject, begins interrogating our young teacher on her personal life. She is surprisingly eager to tell us about her American fiancé she is going to visit in a week. “Awwww, how did you guys meet!?” several students cry out, surely imagining their own potential “abroad bae” relationship in the months to come. Our teacher explains how the two of them met on a tram one day when she was speaking English with a visiting friend. A man walked up to them and said, “Hi. I heard you two speaking English, I haven’t heard my language in so long, where are you from?” And that’s how the romance began. They hit it off and went out to dinner that night. But these things don’t just happen, right? I’m starting to think

a journal of global perspectives 31

maybe there’s something magical about the tram. Until this point I’d only thought of the tram as a mode of transportation, but maybe there is something more.

OCT 20

There are times when I zone out to the buzz of the tram, and today is one of them. I let my pupils flicker across the wide, fall-colored branches of the linden trees and go in and out of focus. They remind me of home, although they are only a dull version of the vibrant red maple trees that create the famous Vermont fall view. But just as the thought comes, it leaves, as the trees come and go from view. The tram is a form of meditation I don’t realize I am participating in. My mind is blank. I just sit. I can’t be the only one in this state, because the tram is so quiet. The general vibe is similar to what I imagine a yoga retreat would be like, a moving meditation lounge. There is no eye contact. Everyone is in their own space even when crammed together, and it is as if we are all alone. Just a person in a tram. It may very well be a reflection of the distrust that was planted in the minds of so many only a generation ago. I think back to a Czech history lesson when we learned about the Communist era. It was a time when the regime employed secret police to “out” any illegal behavior. A time when a friend, a neighbor, or even a brother could be untrustworthy. Perhaps this historic distrust and unease explains the lack of eye contact that has turned into peaceful contemplation on the tram.

OCT 26

It’s 5 pm on a Thursday. Plopping down across from two strangers, I let out a sigh of relief that there are enough open seats for me to relax, exhausted after walking around the city all day. Oh, whoops, they clearly aren’t strangers to each other, I think as their lips begin to touch, catching me offguard. Although I’ve been here for a couple months already,

32 The Aleph

I am still in shock every time I am confronted by PDA in my quiet peaceful place. How can people be so private and distant with strangers, yet show such public, deep affection in view of everyone? The couple looks to be in their late forties, much too old for PDA in my opinion. As they get closer to one another, what started as a playful kiss turns into a full-on makeout session, five feet in front of me. I feel so uncomfortable, as her hand grazes up his leg and he grabs her face. Am I jealous of their intense love? Honestly, yes. But that’s not what makes this so awkward to be a part of, as somehow, I feel like a background character in their love story. I think about the boy I met the other day in my Architecture class, and dream about a day when we could be the couple in the tram, unable to keep our hands off each other. But realistically, I wouldn’t be as bold as that couple, having grown up in a modest family, a modest American society. But, as I will

View of Český Krumlov, Czech Republic [Jenna Bredvik]

View of Český Krumlov, Czech Republic [Jenna Bredvik]

learn, this activity is as normal to Czechs as refraining from eye contact. Although I feel as though I am becoming more accustomed to Czech culture, these differences make me uncomfortable. But the couple is in their own bubble, just as I am, finding a private space and moment on the tram, among so much city chaos. So, I look away and enter my peaceful state once again.

NOV 1

The halfway point is coming along quickly and by now I’ve sunken into my routine. The tram doesn’t surprise me like it used to; I’ve fallen out of the honeymoon phase and am now comfortable with the tram. I wait for Tram 17 at Nadrazi Modrani. It takes me the nine stops to school, where I depart. However, this afternoon, the stench of dirt, old beer, and sweat greets me as I take an open seat in a surprisingly uncrowded area of the tram. Then I realize why it is so vacant. In front of me stands a man who hasn’t seen a shower in months. His hair covers most of his face, scruffy like a scouring pad, only his blue eyes visible. He stands by the door, maybe aware of the ripe smell protruding from underneath his layers of jackets. He is one of the large number of homeless people who live in Prague. They are rarely seen on the tram due to the cost, although I can see this man has done this ride before as he is on the lookout for ticket checking patrols who might catch him. As I examine him and his belongings, I wonder what his life is like. Here I am, studying abroad in a foreign country that I think of as a castle-infested fairyland. The same place that has done this man dirty. What is in his bags? Does he even have family? The questions circulate but no words leave my lips. People don’t talk on the tram, they judge.

NOV 3

As I sit on the tram, “Sink” by Noah Kahan plays through my headphones, reminding me of home. I went to high

34 The Aleph

school with Noah and now he is a famous folk-pop artist with millions of listeners. I guess what I’m doing is kinda cool too, traveling through Europe, but what am I going to do with my life? Memories come flooding in like water through a broken dam. His acoustic guitar fills my mind as I worry about things I have to do. Get my classes situated, figure out where I’m living, call my family. Figure out my career path. Make money. But then the sunlight hits my face as the tram speeds out from under a bridge, and I’m brought back to real life. Tram life.

NOV 15

Friday evening rolls around and I find myself on the tram once again, on my way to meet up with the girls for a night out. The normal silence is disrupted by the sudden presence of loud voices as two women bustle in, wrapped in scarves and mittens on this brisk early winter evening. They must be foreigners, I think, as I self-proclaim myself

View from Old Town Bridge Tower, Prague, Czech Republic [Rachel Yackel]

View from Old Town Bridge Tower, Prague, Czech Republic [Rachel Yackel]

a local with two months spent in Prague under my belt. As I’m bombarded by their speech, I realize that for once it is a language I recognize. I have seen this duo before on my tram ride, two girls in their late twenties, one with flowing black hair, and the other with light red. I turn the volume down on my “chill tram” playlist and tune into their conversation. As I listen to their accents I assume they are both from Europe, maybe one from France and one from Spain, with English as their shared language.

They are speaking about boys, relationships, all relatable to my 20-year-old college self. The black-haired girl is telling the other one about how to interpret men’s actions and words, a notion more complex to me than my freshmanyear calculus class. “It is important to take risks, because then you aren’t left wondering. And if the risk doesn’t give you the result you’d hoped for, it is also important to move on. Things happen for a reason.”

What they are saying resonates with me. I had left behind all of my past relationships, ready to begin fresh when I arrived in Prague for my semester abroad. I started seeing the cute American boy I met in Architecture class a few weeks back. We are at the stage in the relationship where we know we like each other, but haven’t decided how serious we want to let the relationship get, considering the time constraint of study abroad. The word “risk” lingers in my mind. I am taking a big risk, emotionally, deciding to see a boy abroad, knowing that the next semester he would be going to Australia and I would head back to school in New York.

As I near my stop, Narodni Divadlo, where I will meet my girls and Uber to the bar across town, I consider leaning over the seat and telling them how much their conversation has helped me. But we are in Prague, and even though they are foreign, two months abroad has taught me that I must stick to the culturally expected actions of the Czech Republic. As I exit at Narodni Divadlo, the city is cast in

36 The Aleph

darkness, but street lamps and talkative groups keep the streets awake.

My friends and I Uber to Lucerna, a bar all the American students go to on Fridays. A few hours and a couple glasses of wine later, my friends and I tram home. “Do you want to get food, oh my gosh can I post this cute pic of us from tonight!? The boy texted me!” Non-connecting sentences flood out of our excited mouths into the otherwise silent tram. This time we are the loud foreigners. I pause and realize I am no local in this situation, just a loud American tourist, and I may never be able to change my cultural habits.

At 2am we arrive back at Vytón, where we met up at the beginning of the night. I say goodbye to my friends and as they walk to their dorm I run to catch the tram that comes only every thirty minutes after midnight. I find myself thinking about how the night would be different had things gone differently with the boy. I laid my feelings on the table tonight. As we sat in a booth at the bar I told him I liked him. He got scared at the slightest sound of commitment and bluntly told me that after this semester he wouldn’t see me again. Why do guys have such a problem with the idea of commitment?

Sitting on the tram, I play the conversation over and over in my head. I slump down and pull my jacket over my crop top, not wanting to draw any unwanted attention. But I catch someone looking at me. No, staring at me through the window reflection. Her eyes are tired, red, with her nightout makeup barely holding on. One hand clutches her purse to her lap, and the other holds her jean jacket closed over a floral crop top. Is she Czech? American? Where is this girl from? A tear rolls down her cheek. Why is she alone on the tram at this hour? Why am I? There aren’t many people filling the seats at this time, but I feel safe knowing she is here. Then I feel the tear hit my own chest and realize I am alone.

a journal of global perspectives 37

Sweat drips down my sleeve as I run to catch the approaching tram. I don’t have time to wait five minutes for the next one, because I am already late for school. I barely make it, stepping on and grabbing a seat, my breath heavy. Prague in the snow is a sight to see. It brings the fairytale to life, turning the city into a snow globe that I get to witness from behind the glass of the tram window. A reverse snow globe?

The tops of the renaissance and gothic buildings lining the road are dusted with a light, soft snow. People prance around the city, a new-found energy in their step. As we slow for each of the normal stops I examine the people waiting for the tram. I love people-watching. The waiting people move into the tram as soon as the doors open, getting to the warmth as fast as possible. Dressed in light coats, they must not have been expecting the sudden snowfall that has surprised us all. A group of moms enter the tram, fretting over their cold babies. It must be the time

DEC 1

Vltava River, Prague, Czech Republic [Marion Miller]

of day for the afternoon stroll that mothers yearn for. As the tram pulls away I catch a man out of the corner of my eye. Wait, is that man outside dead? He’s on his back. His gut surrounding him like a puddle. He is limp. He looks blue. Is it from the cold or is he dead? What is happening? People approach him. I hope they will stop to help him because I sure can’t. Or should I get off at the next stop and be part of the drama? No, I’ll just look in the newspaper tomorrow and see if there is news about a dead man. I’m restless as questions fill my mind and I feel guilty about not helping. But as I learn, when you’re on the tram there are some things that you need to let pass by, and hope everything turns out ok. As the tram keeps going, I hear an ambulance in the distance. In the tram, I am separated from the snowglobe that is Prague - I can’t penetrate the windows and jump into a scene that I am not a part of. So I sit, watch, and wonder.

DEC 10

A text pops up on my phone as I near the third stop before home. “We are so excited to have you home! Bingo is all bathed and groomed.” My mother’s voice echoes in my ears and makes me uneasy; while I can’t wait to see my fluffy dog, I am also filled with a sense of dread that my time in Prague is coming to a close. This texts forces me into the future, a space I have not been in for so long. I have gotten comfortable in the present, and this is a rude awakening. How can I only have a few days left? I have been so absorbed by this thought that, until now, I don’t realize this is my last tram ride. I have spent much of my time with the tram over the past four months, and have learned a lot looking through its windows. The tram had become a home, a safe space from which to view Prague. Suddenly, a ray of sunlight hits my face and I blink my eyes. In this moment I am brought back to the present, where I am alone, sitting on the tram.

-Marion Miller

a journal of global perspectives 39

Darjeeling Himalayan Railway, India [Brandon Harding]

Darjeeling Himalayan Railway, India [Brandon Harding]

Bad Urach: A Week in the Mountains

My first month in Tübingen, September, was spent mostly acclimating to my new life in a new city, country, and continent. I did this by enrolling in a Deutsch Kompakt Kurs (German intensive language course) through the University of Tübingen. I have made, through this course, many new friends, and I have seen a lot of nearby German cities, such as Stuttgart, Konstanz, Meersburg, and Bad Urach. I also have seen a lot of castles.

The most memorable trip that we went on as a group was our week-long excursion to Bad Urach. Bad Urach is a city about 35km (about 20 miles) southeast of Tübingen, in the Schwäbische Alb (Swabian Alps). We stayed in a hostel in the mountains about a kilometer walk from the historic center of Bad Urach. Once we arrived, we were only allowed to speak German to each other in and outside of class. In addition, we did a theater project where we wrote and performed a skit at the end of the week. In the mornings, after my morning coffee on a balcony overlooking the mountains, we would go to class, and in the afternoons, after my midday coffee on a balcony overlooking the mountains, we would have activities. One day we climbed a mountain to see the castle ruins and a waterfall. Another, we went on a scavenger hunt in the city interviewing residents. But my favorite afternoon adventure of all was the trip to the Residenzschloss.

Historically the seat of the Counts of Württemberg-Urach, the Residenzschloss was constructed in the early 15th century and modelled on the Altes Schloss in Stuttgart. The County of Württemberg, originally one county, was separated in 1442 by the Treaty of Nürtingen into the County of Württemberg-Stuttgart and the County of WürttembergUrach. The two counties were reunited in 1482 through the Treaty of Müsingen, and with the seat of the Count of Württemberg moving back to Stuttgart the Residenzschloss

42 The Aleph

Moments I

became a hunting lodge of the Dukes of Württemberg. The Residenzschloss is known historically and architecturally for its Goldener Saal (Golden Hall), which is a good representation of Renaissance architecture. It is one of the few remaining German renaissance halls, and by and large the best example of the style in Germany. The Goldener Saal is covered in palm tree iconography, the symbol of Count (later Duke) Eberhard I of Württemberg, and was originally constructed for his wedding to the daughter of Ludovico III, the Marquis of Mantua. The Residenzschloss has a wonderful collection of royal sleds that I wholeheartedly recommend seeing, and once it gets a little warmer I plan on returning to Bad Urach to visit the thermal baths, which I have been told are a sight to see.

That week, my week in Bad Urach, was most definitely one of the best weeks of September. And as I sit in Tübingen with winter quickly arriving, I miss sitting on that balcony, with the sun rising early and setting late, coffee in hand.

-Elizabeth Fajardo

Mount Snowdon Summit, Wales [Meredith Fennell]

Mount Snowdon Summit, Wales [Meredith Fennell]

Do You Regret It?

Standing outside in the cold, misty rain I asked the guide, “do you regret it?”

After learning about the Troubles from a book and my lecturers, it seemed simple to explain - it was a decades-long political conflict with religious undertones between the Unionists and Nationalists. Yet it can be hard to understand because the people involved seem so similar - they’re from the same place, speak the same language, and worship the same God - yet the violent conflict endured for decades. But reading about the Troubles did not prepare me for what I experienced one morning in Belfast.

The day started as a typical city tour, but slowing to a stop on Shankill Road I quickly learned it was so much more. Our guides were political prisoners during the Troubles.

Touring Shankill Road with our Unionist guide, it didn’t seem possible that the slight, soft-spoken man in front of us was once a political prisoner capable of violence. This quickly changed as he spoke of his role in the conflictweapons smuggling, bombings, and murdering upwards of 30 people. So, as the tour ended he asked us if we had any questions. Nervously, I asked, “Do you regret it? Do you regret your part in the Troubles?”

Without hesitation he replied, “Yes…I genuinely regret my actions, but ask your Nationalist guide the same question and he will say no.”

Leaving our Unionist guide, we turned the corner of Shankill Road, drove 400 meters, just beyond the Peace Wall, and into the Falls Road neighborhood. Here, we met our Nationalist guide. As he described the history of the area and his involvement in the conflict, it was clear that he harbored anger.

44 The Aleph

Moments II

Seeing his resentment, I couldn’t get our other guide’s words out of my head, so I asked… “Do you regret it?”

After a moment he replied, “No. And I would do it all again.”

Each guides’ words stuck with me as the sky cleared into a rare sunny day outside my bus window. Emerald fields glistened, and I wondered how such a beautiful place harbored such a troubled past. But for some, the conflict had never ended.

A conflict is more than what is contained in the pages of a book - it is complicated and difficult to recover from: healing takes time.

And all of this became clear to me after asking a simple question.

-Margaret McKean

Hungry Crows in Parking Lot, Ireland [Margaret McKean]

Bergen-Belsen Camp Reflection

It was a cold, snowy day in late January when a few friends and I decided to travel to Bergen-Belsen for the day. Although I had heard about the camp in classes before, I had a personal connection to it after “The March: Bearing Witness to Hope” trip in 2016. Sally Wasserman, a Holocaust survivor who traveled with us, had been a refugee in the Displaced Persons camp there after the war. Although this is about the third or fourth Holocaust memorial I have seen during my time abroad, I thought it would be fascinating to go, especially after seeing the Anne Frank House over the holidays (Anne and her sister Margot were prisoners in the camp).

When we arrived, we walked through the museum filled with the entire timeline of the camp. What I had not realized was that it was used as a Soviet Prisoner of War camp before the Nazis turned part of it into a concentration camp. The museum included hundreds of testimonies from survivors and former POWs, including footage of stories being told, along with artifacts ranging from gas cans to glasses to prisoner uniforms. The museum was set up very well, and even in a rush to get through, it still took us almost 2 ½ hours to get through it.

We then went outside into the snow to walk around the grounds of the camp. Unfortunately, there are no remains of the camp, as it was destroyed soon after it was liberated in an attempt to prevent the spread of typhus and other diseases. The only original landscapes left from the camp are the mass graves scattered across the property. The perimeter of each grave was marked with a stone wall and an engravement reading “Here rests XXX people”, with a date and year. Although there were many small ones, the large ones with 1,000+ people buried in them were the ones that

46 The Aleph Moments III

Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, Berlin, Germany [Jordan Raivel]

really got to me. As we tried to move on, we came across a few memorials towards the end of the camp, including the Jewish Memorial and the Margot and Anne Frank grave. After spending about 4 hours at the camp, it was time to head back to Bremen and reflect on what we had seen.

Although Bergen-Belsen was different than most of the camps I had seen on my trip in 2016, it was similar to Treblinka in that there was nothing left to see other than the mass graves and memorials that were put up years after the camp was liberated. What I appreciated the most about the visit, though, was the museum and the fact that you had to imagine a lot about what the site was like. The museum did an amazing job of detailing the entire history of the camp, from its days as a Soviet POW camp to an extermination camp to a Displaced Persons camp. After reading about this history and seeing the artifacts from the camp, I was able to picture a lot of what the site looked like before, during, and after WWII. I could see where all of the major buildings stood along with where people lived and worked. The fact that you had to imagine what was there made the impact that much greater, as you’re taking information and processing it differently than you would by seeing it all directly in front of you.

When you have to picture everything on your own you are forced to think about the vile conditions and gross mistreatment the prisoners face rather than hearing about it on a tour through a preserved camp. That is the most significant impact of Bergen-Belsen and I hope to get back there again to spend more time on the grounds of the former camp.

-Cynthia Kellett

48 The Aleph

Ancestral Recall

I had finally found it. I found it tucked away along a side street, three blocks from the metro, up a narrow staircase, and down a short hallway. The adjacent buildings advertised karaoke bars and beauty salons, and countless restaurants filled with reveling office workers, celebrating the end of the week around tables of simmering barbecued meat and bottles of soju. The store I was looking for would not have been out of place in the United States, with shelves lined with board games sporting colorful cardboard cases, and glass display cabinets densely lined with collectible cards. Were I in the US, such a setting might be incredibly familiar to me. Even as it were, in South Korea the environment felt remarkably similar. As I was admiring the cards in their protective display, I heard the attendant at the counter behind me call me over in heavily accented English, “Hey, can I help you?”

Moments IV

Sidewalk Gathering, Vietnam [Tolulope Arasanyn]

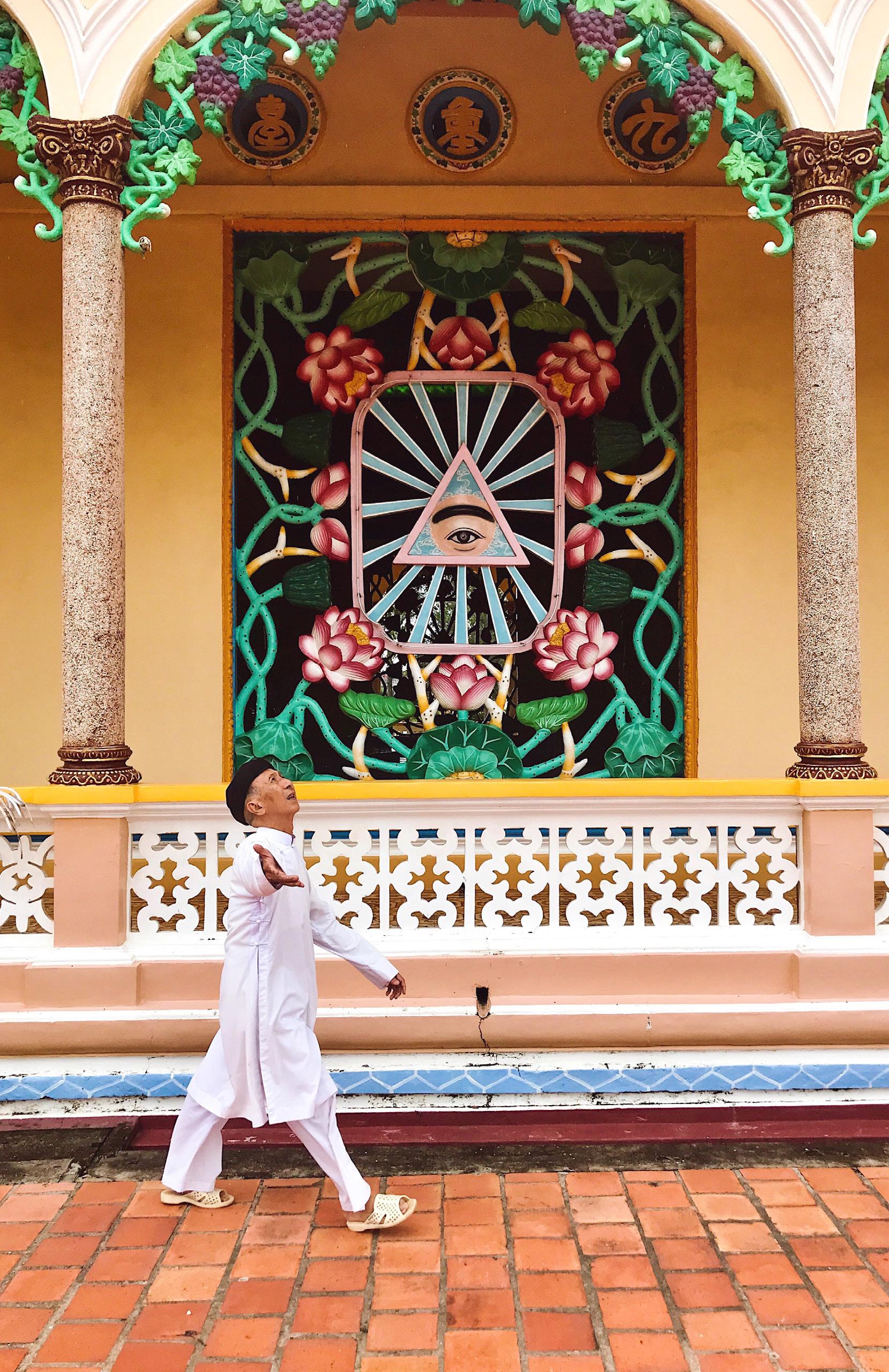

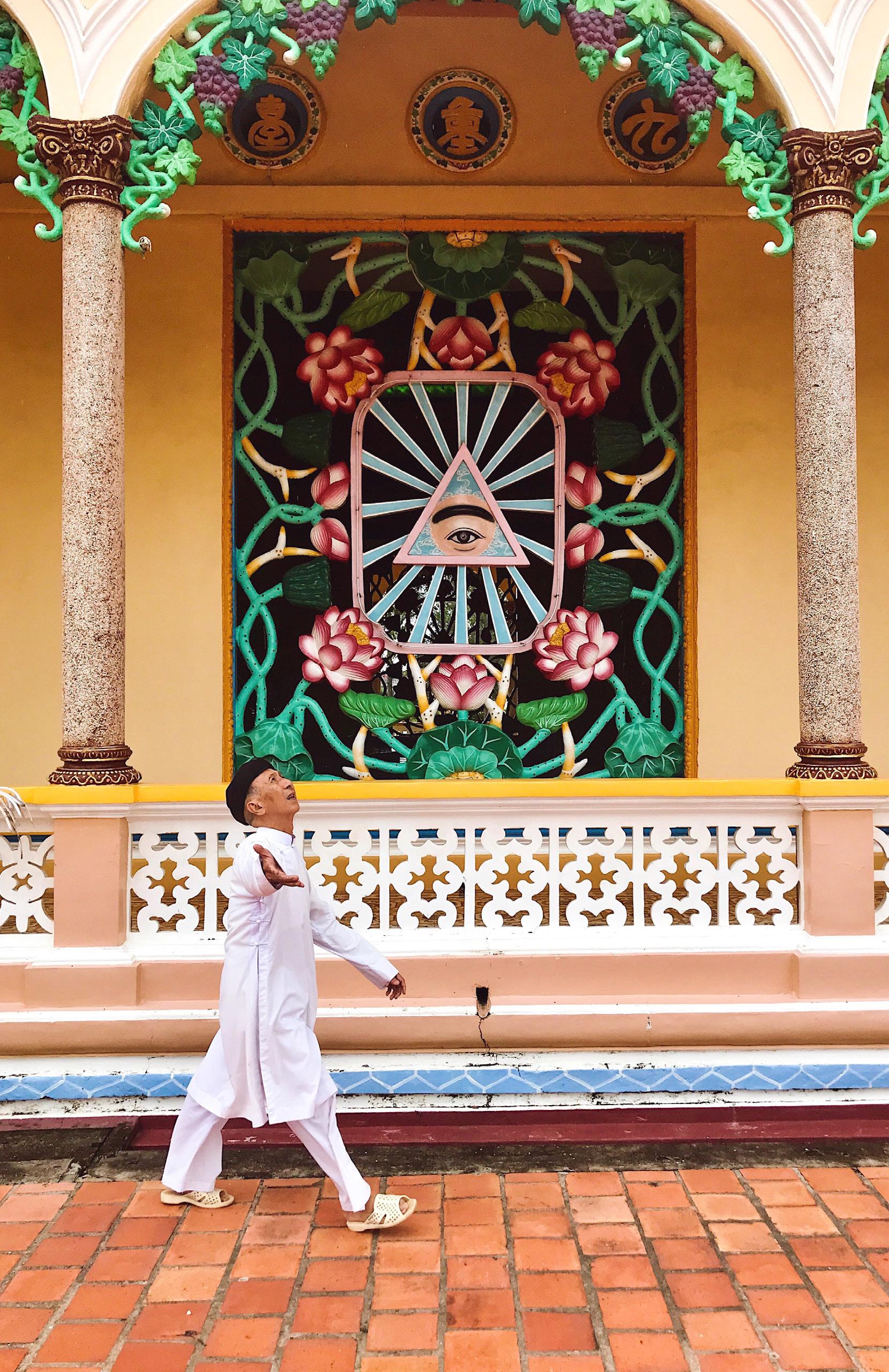

The Eye of Providence, Vietnam [Kristina Worts]

Less than a month prior, I was packing my bags in my parents’ apartment in New York City. Apart from the usual accoutrements of clothes, gifts for the people I would meet during my time abroad, and supplies for the coming semester, a few items in particular would serve as my gateway into a side of Korean culture that many might not be familiar with. In the US, millions of players gather together in game stores and around kitchen tables to play the card game Magic: The Gathering.

First released in 1993 and inspired by the fantasy tropes of Tolkien and C.S. Lewis, players assume the role of powerful wizards known as “Planeswalkers.” Players express their wizardly abilities through cards that allow them to summon fearsome beasts and call upon the power of lightning and fire, all of which is depicted on the cards themselves with detailed artwork. For many, myself included, Magic is more than a simple hobby; it is an outlet for people who might consider themselves to be introverted, as the game’s unique social aspects allow people to connect and push their social boundaries. For others, Magic serves as an outlet for competition for people who do not enjoy traditional sports. My point here is that Magic is an important part of many people’s lives, and as the game spread outside of the US, it brought those same things to people across the world. As I sat in my parents’ apartment, packing my bags in preparation for my semester abroad in Seoul, South Korea, I made sure to leave space for my own Magic deck.

Fast forward to September, back at the game store in Seoul that I had just walked into, and I couldn’t help but feel an intense sense of trepidation. Despite my Korean heritage, I had never learned a single word of Korean before coming to this country, and I was one of only a few people in my immediate family to have gone to Asia at all. Though I found Seoul to be an incredibly accommodating city for speakers of English, I was daunted by the prospect of trying to play a game using game pieces that were written in a language

a journal of global perspectives 51

I could barely comprehend. I was afraid that I would screw up, that I could be accused of cheating, even if by mistake. I didn’t know how people would react to having an Englishspeaking American sitting across the table, an outsider wholly unfamiliar with their language and customs.

All these thoughts and more rushed through my head as I handed over my entrance fee to the store clerk who had waved me over. As I had a few minutes to wait before the evening’s event started, I wandered over to the game tables and watched a group of four Korean players engaged in what seemed to be a rather intense game of 4-way Magic. From their expressions, and the rounds of raucous laughter that would periodically erupt, it was not hard see that these players were engaging in some friendly banter. Although I could not understand their words, as I looked over the game board I could read the story of the game through the cards. Many of the cards were written in Korean, but I recognized the distinctive artwork of the cards and I found that I could easily follow the action. I was snapped out of my reverie by the store attendant calling me and a group of 7 other players to one of the large tables.

Magic has evolved in many ways over the years and the way one group of friends plays the game can be radically different from the way a different group plays. Such differences are often known as “formats,” which are rulesets that determine what cards can be played and how a deck is constructed. What I had signed up for was Draft, a format where players construct their deck of 40 cards in a somewhat random fashion. Groups of cards are passed from player to player, and one must try to select the best cards to add to their deck. I had known going into the draft that the cards were in Korean, but I had my trusty smartphone handy to help me keep the names of cards straight. As the draft concluded, and I was given an opponent selected at random to play against. I would be lying if I didn’t say I was greatly relieved when he said hello to me in English. Despite his struggles to

52 The Aleph

communicate in English, and my total lack of understanding of Korean, I quickly found that we had another medium by which to talk: the language of Magic. Magic players have come up with an expansive codex of jargon and shorthand phrases - many of which, I was pleasantly surprised to find

a journal of global perspectives 53

When Two Worlds Collide, Yangon, Myanmar [Patrick Tavares Ruivo Muscari]

out, were also known by my Korean-speaking opponents. Because of this, our game was able to run smoothly, and by the end of game three of our best-of-three series, a small crowd of other players had gathered around to watch us duke it out. And an exciting game it was, with both of us constantly exchanging blows, unable to find any edge. Finally, it came down to the wire: I had exactly one card in my deck that could pull out the win for me, and my opponent was guaranteed to win the very next turn. I went to draw my card…and it was not the one I needed. Releasing a breath held through sheer tension, I offered my opponent the conciliatory handshake, as the spectators around us let out a collective gasp of excitement.

Ultimately, as I look back on this experience, and on my experience in South Korea, I feel like I learned something very important about language. Languages like English and Korean are all well and good, but some ideas, like the rules and intricacies of games, enable whole new methods of communication on their own. Brazilians can travel to Germany and end up playing the exact same version of soccer, despite sharing no common language. Someone like me can travel to the heart of South Korea, connect and build relationships with people through a shared passion, using the medium of a children’s card game. As I look back on my time abroad, I can’t help but feel grateful to the game of Magic, silly as it may be. Without it, I doubt I would have been able to leave my social comfort zone and get myself to interact with native Koreans. Having that shared commonality, across thousands of miles of ocean, provided endless possibilities and the chance to have profound and meaningful experiences that I can take with me wherever I end up in the future.

-Adrian Shin

54 The Aleph

Gunung

Machu Picchu and Huayna Picchu Mountain, Peru [Alexandra Bilodeau]

Kawi Sebatu Temple, Bali, Indonesia [Mekayla Montgomery]

Machu Picchu and Huayna Picchu Mountain, Peru [Alexandra Bilodeau]

Kawi Sebatu Temple, Bali, Indonesia [Mekayla Montgomery]

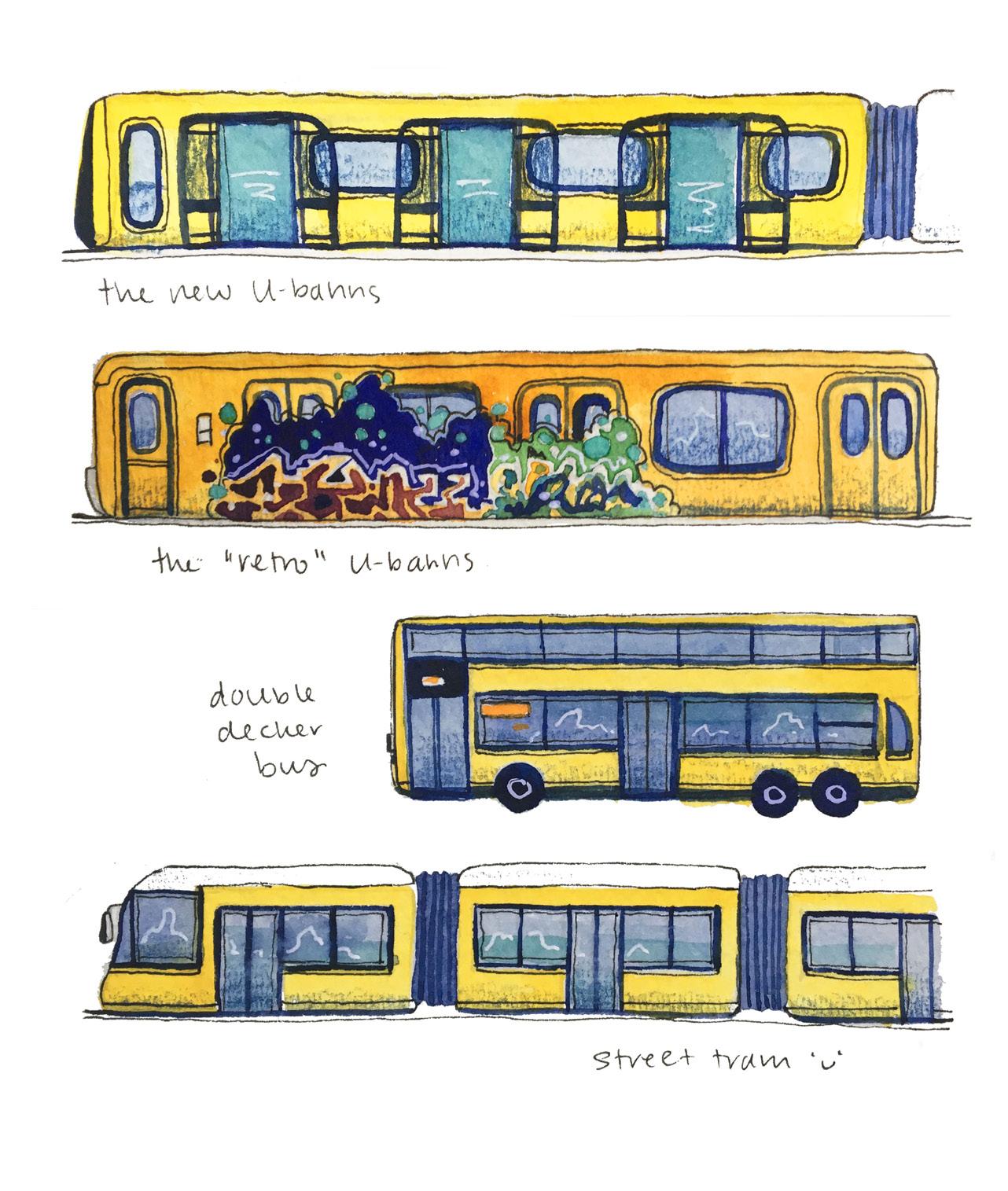

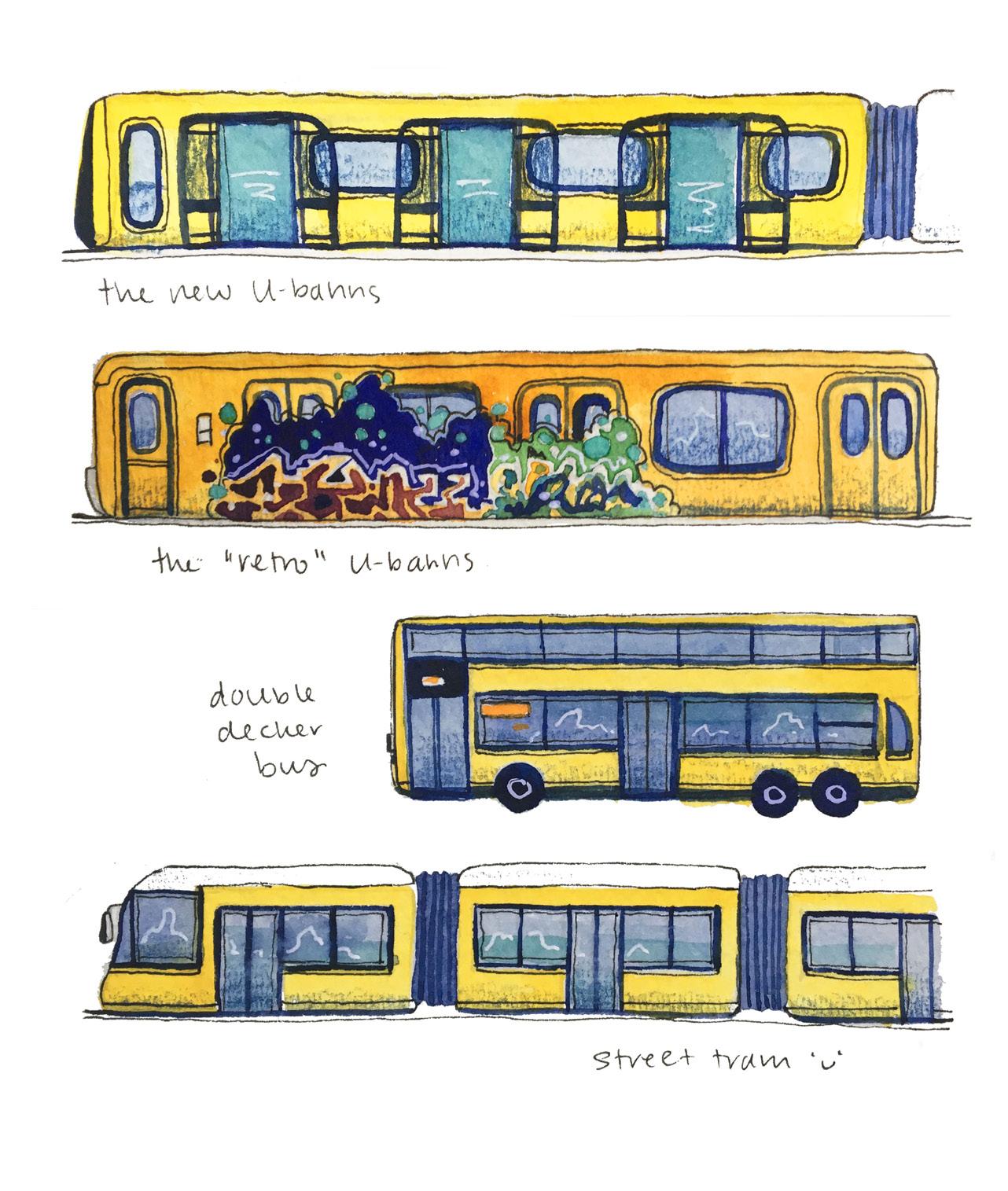

Ode to the BVG

On the U-Bahn this morning, smooshed in a crowd of shifting commuters and getting my toes run over as a woman tried to make room for her baby carriage in the alreadypacked train car, I was suddenly overwhelmed by the feeling that the BVG really does love me.

The official slogan of the Berlin Verkehrsbetreib (BVG) is weil wir dich lieben, or “because we love you.” Their advertisements are 4-minute long music videos in which people use public transportation to escape ridiculously unfortunate situations. The ads are hilarious, but they also convey an important truth: in Berlin, public transportation is pervasive and accessible.

I remember on my first night out in Berlin, I turned off my phone and later found myself locked out by my new SIM card when I powered it back on, without the code needed to access cellular data. My heart skipped a beat as I realized that I was across the city from home and couldn’t remember how to get back.

But the BVG took care of me. In the bright station at Alexanderplatz, I connected my phone to the WIFI with which every single tram, U-Bahn, S-Bahn, and bus stop is equipped. A quick search on the BVG app and a few screenshots later, and I had all the information I needed to get home safely.

The BVG works. It is designed to get as many people where they want to go as safely and as expediently as possible, part of the marketing of the city that aims to make public transit attractive. The evidence that it succeeds? Everyone uses it. At 7am businesspeople on their way to work sit next to people who just left the club. A Berlin U-Bahn car is a microcosm of the vibrancy of the city’s people.

56 The Aleph

Moments V

My sketches (p. 59) illustrate the fact that the BVG vehicles are not just useful, they are iconic. The yellow paint makes them recognizable, which only contributes to how successfully they are marketed to Berliners and visitors.

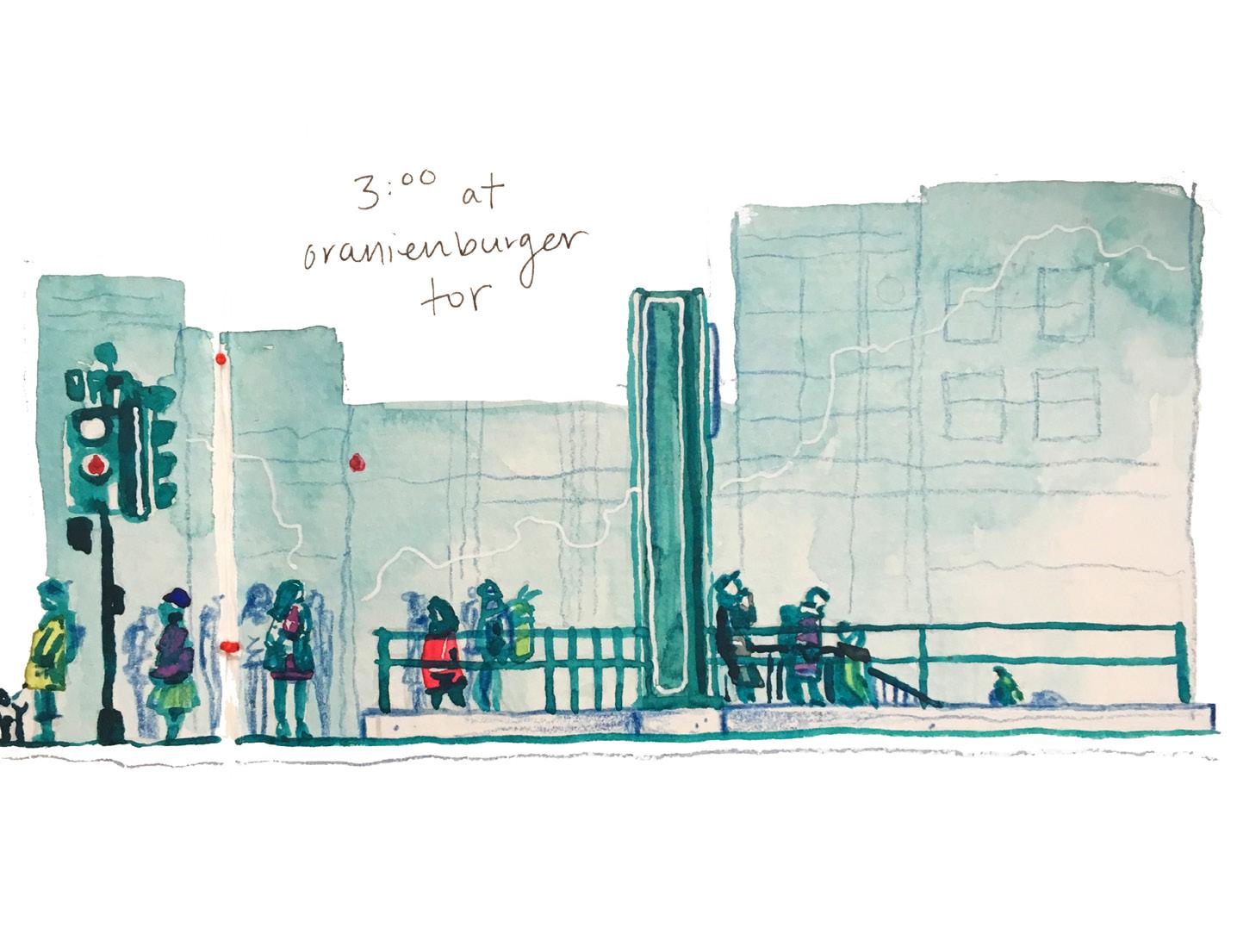

In addition, using the BVG is intuitive; exit a train and cast your glance in a 180-degree arc around the platform. You will see a sign above the access point for every connection that is possible from where you stand: S-lines are green, U-lines are blue, the tram is red, the buses are purple. The symbolism is systematic, and you will be directed up staircases, around bends, over bridges, across roads, and along tunnels to your connection without having to think at all. Passengers are sorted into streams as easily as water is diverted into pipes. Since the first night when I was lost in Alexanderplatz, the system has grown intuitive to me and I can usually make my way anywhere in the city without even pulling out my phone.

Sunset Over the Liberty Bridge, Budapest, Hungary [Katie Consoli]

Sunset Over the Liberty Bridge, Budapest, Hungary [Katie Consoli]

All these accessible and convenient features enable the BVG to limit sprawl (want to go for a hike? Take the S-Bahn towards Wannsee, and use the same ticket to get on a bus which will literally drive you into the woods with trails, fishing spots, and an island accessible by ferry inhabited by the descendants of Frederick William III’s peafowl). The city is more walkable, safer for pedestrians and bikers, less noisy, and less cluttered by automobiles, which in turn improves the embodied sustainability of a dense and less car-dependent city.

Meanwhile in suburbia, you have to sit for at least 15 minutes in your car by yourself in order to get anywhere. There is nothing that alienates you more from other members of humanity like sitting in traffic on the way to the dentist channel surfing the radio and glaring at the guy in front of you who’s texting when the light turns green.

By contrast, there is something tender about sitting among an ever-refreshing cohort of strangers wherever you go. Sometimes, a train car is bubbling with a blend of voices, and every once in a while, I’ll get on a crowded car that is totally, uncannily silent. Fifty strangers stand shoulder-toshoulder, shuffling, swaying; everyone is elsewhere.

To be one passenger on one of hundreds of trains in one of so many cities, crossing thousands of paths every moment, my own bustle tangling with the bustles of innumerable others - it makes me feel small in a wonderful way. I am one of many, connected to my fellow travelers no matter how drastically we may differ in minute and specific ways. We are equal, the way every bird in the flock rises from the field in a single dark mass, the flapping of so many wings sounding as one great rush. Therein lies the power of a good transit system.

-Abbey Frederick

58 The Aleph

Ladies on Motorcycle, Vietnam [Tolulope Arasanyn]

Ban Gioc Falls, Vietnam [Amanda Breed]

Women Sewing, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam [Alyssa Capuano] Babushka, Russia [Alexandra Curtis]

Lighthouse at the Easternmost Point in Mainland Australia [Morgan Ross] Santa Maria in Portico Church, Lazio, Italy [Shannon Smith]

Lighthouse at the Easternmost Point in Mainland Australia [Morgan Ross] Santa Maria in Portico Church, Lazio, Italy [Shannon Smith]

A Self-Made Entrepreneur, Sikkim, India [Elise Donovan] Street Artists, Rome, Italy [Eileen Lent]

Proud Local in Cam Thanh Fishing Village, Vietnam [Ali Turner]

Mount Cook, New Zealand [Brooke Kelly]

Mount Cook, New Zealand [Brooke Kelly]

Woman with Water Buffalo, Vietnam [Olivia Bennett]

The Iconic Ace Cafe, London, England [John Schenk]

Women shelling argan tree shells, Morocco [Samantha Buckenmaier]

Women shelling argan tree shells, Morocco [Samantha Buckenmaier]

A Ceiling of Umbrellas, Irleand [Lindsay Lesniak]

Gorée Island, Senegal [Djeneba Ballo]

Alleyway in Stari Grad, Croatia [Chad Kilvert]

Alleyway in Stari Grad, Croatia [Chad Kilvert]

Rue Monsieur, Paris, France [Jenna Bredvik]

At Ease, Copenhagen, Denmark [Brian Helms]

Prague Castle at Sunset, Czech Republic [Tanner Poisson] Farmer in Angkor Wat, Cambodia [Jonah Salita]

Transporting Bananas, Vietnam [Aubrey Johnson]

Colorful Fruit, Italy [Tai-Ling Bey]

Student Planting Trees, Senegal [Djeneba Ballo]

Student Planting Trees, Senegal [Djeneba Ballo]

Parliament Building, Budapest, Hungary [Brianna Hurysz]

Canal Traffic, Venice, Italy [Tai-Ling Bey]

Sunset in Stockholm, Sweden [Bjørn Antell] Women Working, Ghana [Maya Weber]

Neist Point Lighthouse, Isle of Skye, Scotland [Peggy Wagner]

Overlooking the Roman Forum, Rome, Italy [Emma Consoli]

On Horseback, Argentina [Emma Honey] Lake Bled, Slovenia [Nicholas Stone]

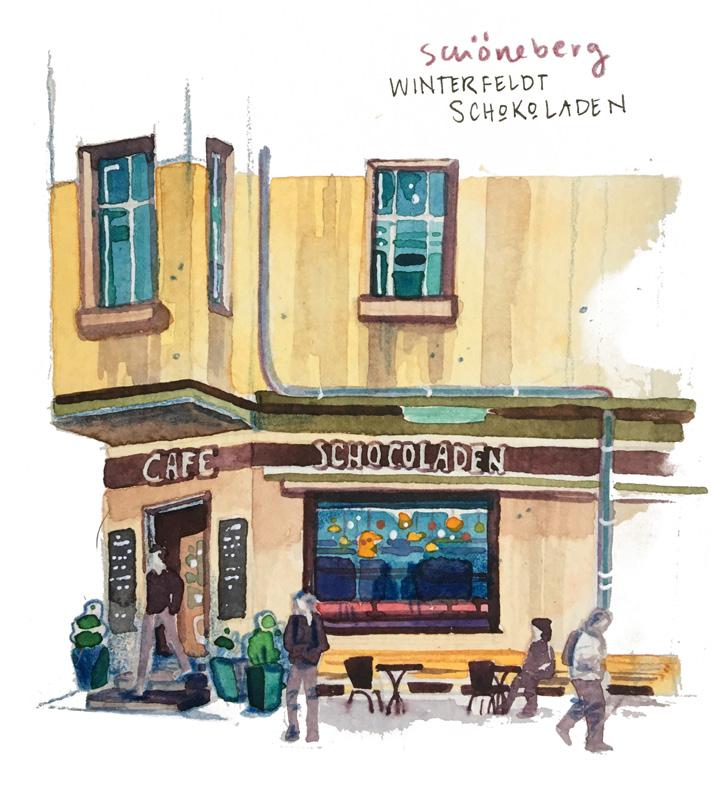

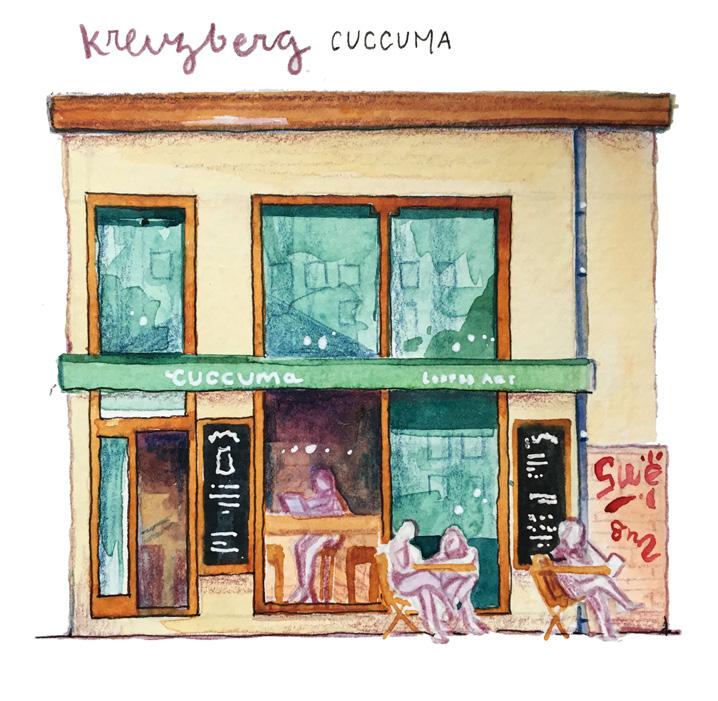

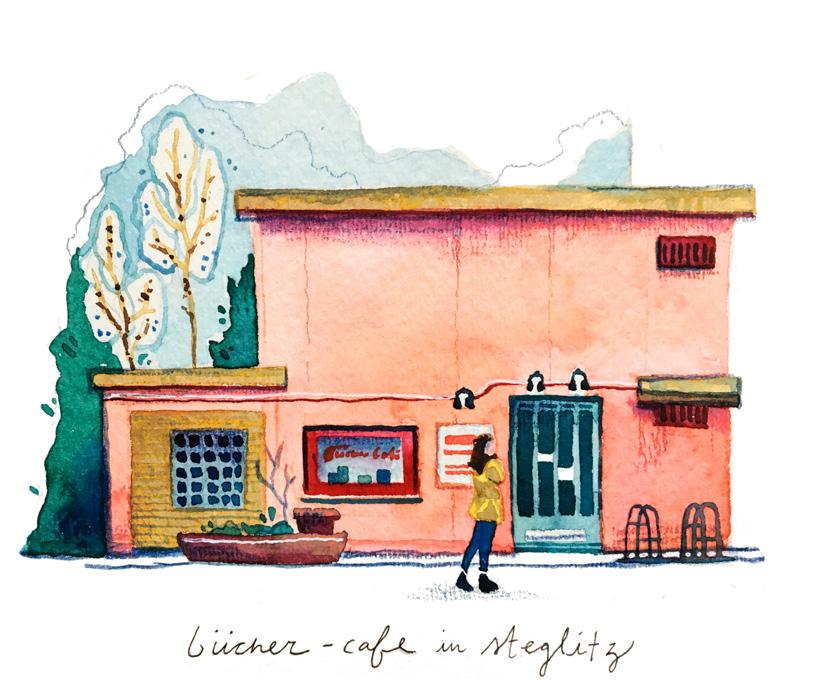

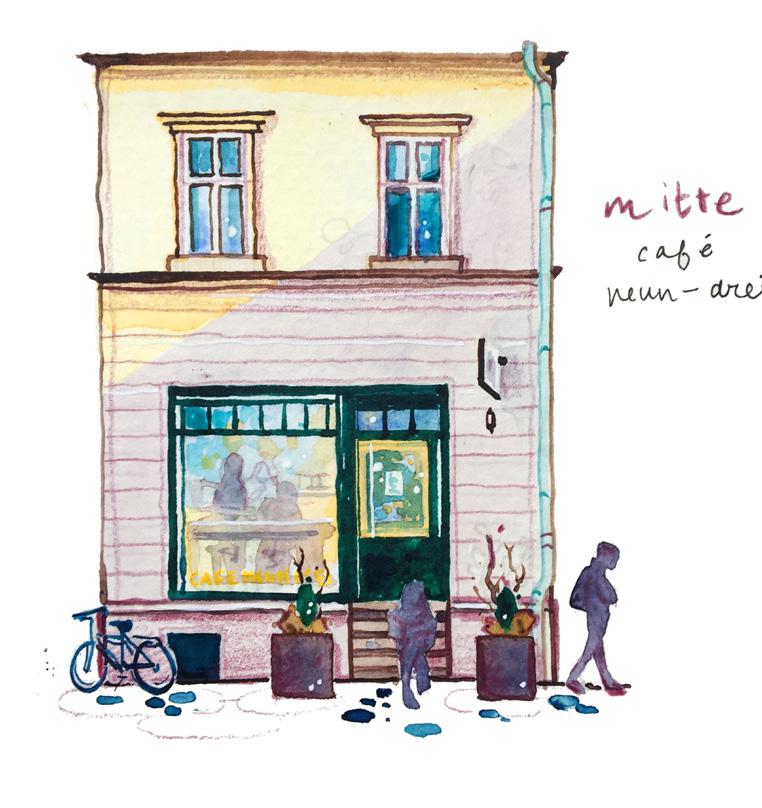

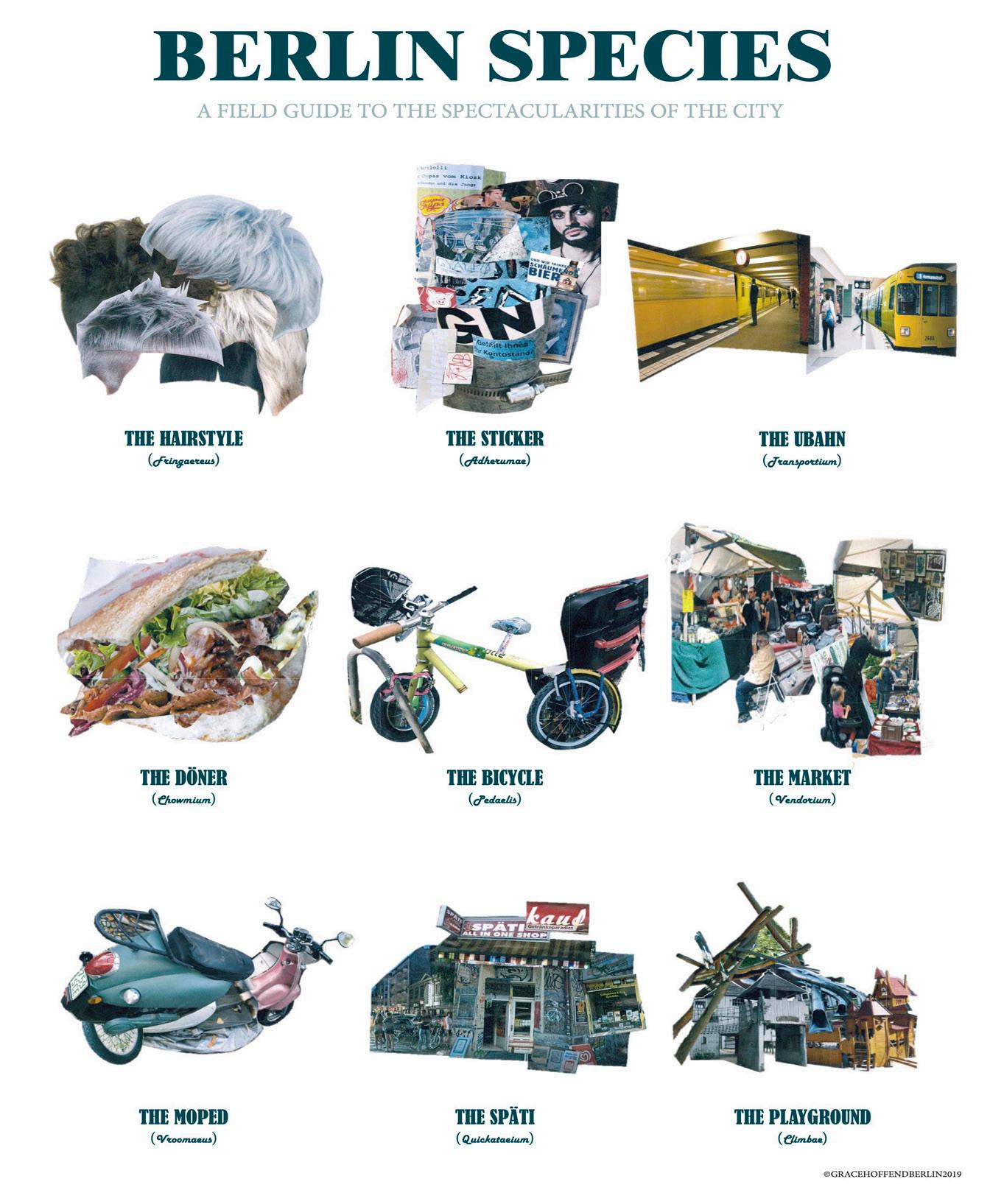

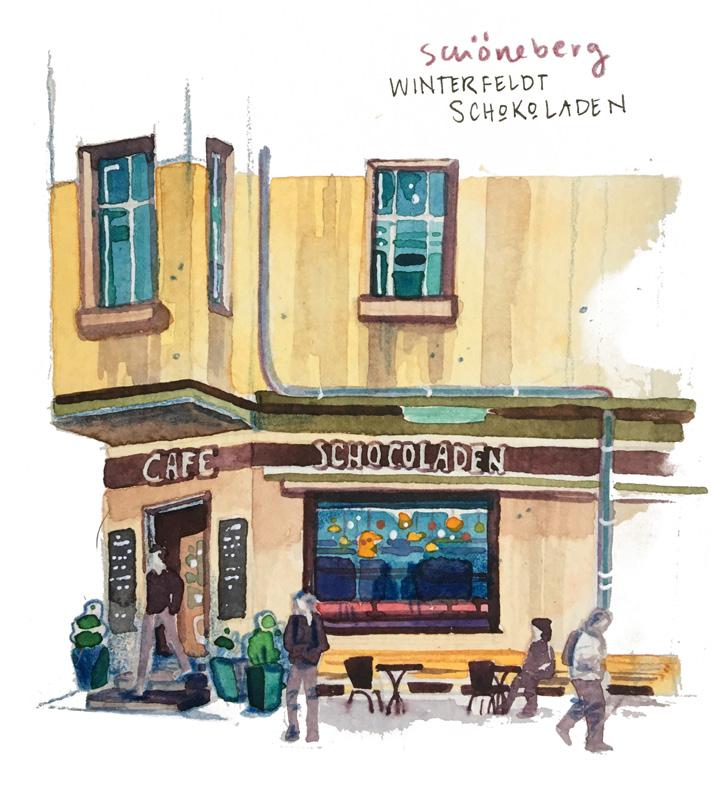

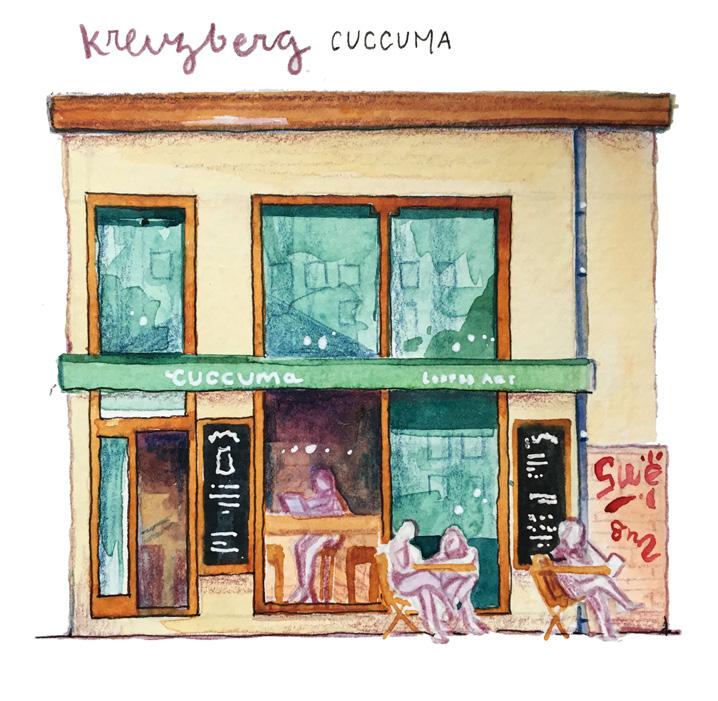

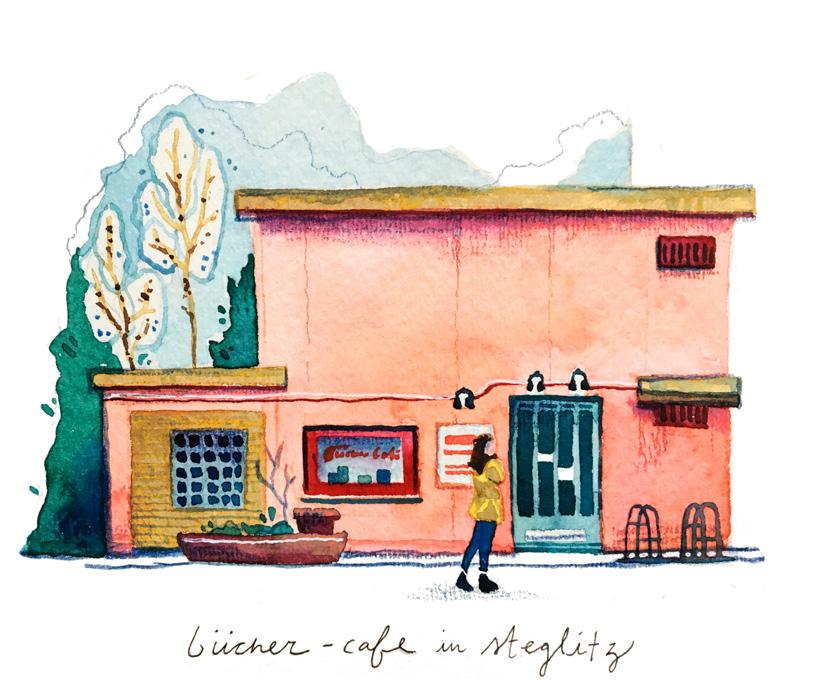

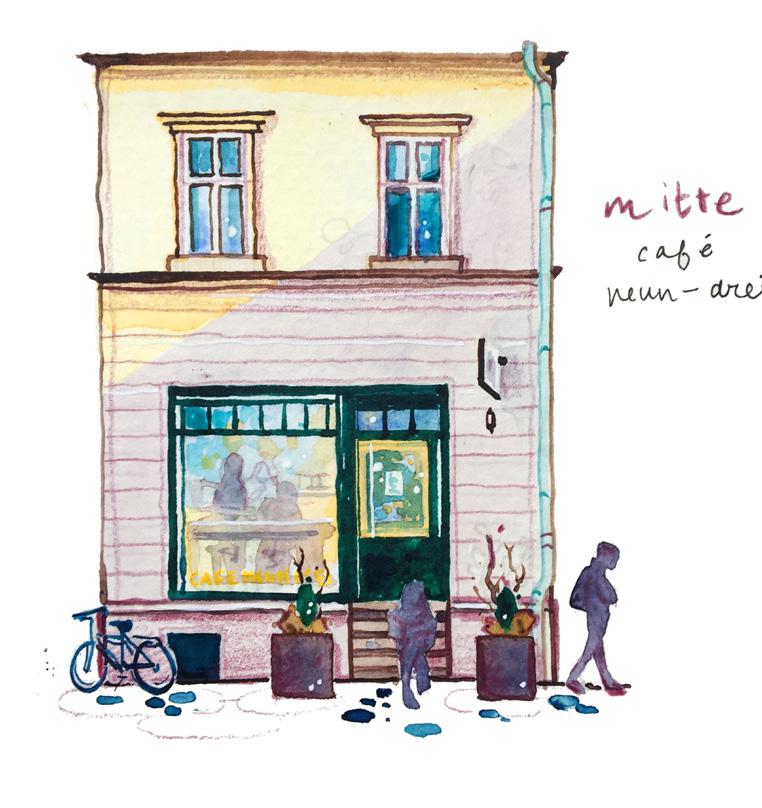

Local Coffee Shops & Neighborhood Character in Berlin

One of my favorite urban sketching subjects is the storefront elevation; drawing a storefront is a great way to represent the liveliness of an urban scene and its inhabitants while also capturing architectural style.

After a few months in Berlin, I’ve begun to get a sense of the distinctions of each of the city’s neighborhoods. There are stereotypes associated with each neighborhood (like Schöneberg has a large population of queer people or Prenzlauer Berg is where all the families live), but the “character” of each area is more complex than can be simplified by

Engagement I

a journal of global perspectives 79