THE FEVER ISSUE 32 THE FEVER ISSUE FALL /WINTER 2023 ISSUE 32

SHOP THE APP OR HBX.COM

WORDS BY ZACH

SOKOL

Artificial intelligence anxiety, dopamine-driven feedback loops, doom scrolling, and other trappings of modern life are omnipresent to the point of banality. However, these characteristics have led to culture production feeling so fast, overwhelming, and cynical that it’s dizzying. We have whiplash from how artists and brands share their work, as well as “content nausea” from the unrelenting social platforms required to grow and maintain an audience.

The ways in which the technological zeitgeist influences the distribution and consumption of art and culture can inspire a feverish, contagious sensation. Side effects may include an emphasis on quantity over quality, pressure to be the loudest in the echo chamber, and the desire to mimic trends that have “worked,” rather than trying to experiment or do something novel. Our reality also pushes people to create and ingest at a feverish pace, even if it’s detrimental to the art itself. There’s a pressure to be frantic, almost hysterical, in our fandom or knowledge of a given subject or subculture, as well as an intractable itch to stand out. Simultaneously, there’s less time and resources available to achieve these goals in an authentic and nuanced way.

This creative malaise affects us all, but there are methods for developing artistic antibodies. For some, this means embracing the speed, chaos, and whirlwind of the present. For others, correctives take shape by inverting certain norms, such as rejecting release schedules, press opportunities, social media promotion, or even an online presence entirely. These iconoclasts may defy expectations through left-field collaborations, eschew the idea of “high” or “low” brow, and operate in a distinct way that’s counterintuitive to the status quo. These are folks who march to the beat of their own drum, and do things anachronistically or idiosyncratically.

In this issue, we’re spotlighting artists and creators who welcome the fever, as well as those who stand in opposition to it. While it may sometimes seem like there’s no escape from the harsher qualities of 2023, the emerging talent and established luminaries in the following pages underscore that things can be done differently. Their work and approach to artistry can serve as a panacea, an inspiration, and a path towards a more ebullient and downright interesting future.

EDITOR’S LETTER 6

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR

Kevin Wong

GUEST EDITOR

Zach Sokol

ART DIRECTOR

Vasun Pachisia

FEATURES EDITORS

Ross Dwyer, Shawn Ghassemitari

GRAPHIC DESIGNERS

Franny Fuller, Phuong Le

EDITORIAL OPERATIONS DIRECTOR

Marc Wong

EDITORIAL COORDINATORS

Samantha Su, Crystal Yu

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Amelia Abraham, Navi Ahluwalia, Kirsten Chen, Dylan Kelly, Joyce Li, Julius Oppenheimer, Jon Rafman, Noah Rubin, Taylor Sprinkle, Shyan Zakeri

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS

Kemka Ajoku, Dohyun Baek, Angel Delgado, Max Durante, Christian Filardo, Clare Gillen, Othello Grey, Kalil Justin, Abhishek Khedekar, Michael Kusumadjaja, Eddie Lee, Maya Margolina, Peter Martin, Corey Olsen, Freddie Randal, Justin Sariñana, Nayquan Shuler

CONTRIBUTING STYLISTS/MAKEUP ARTISTS

Nina Carelli, Ariane Kayla, Destroy Lonely, Joe Van Overbeek, Aidan Palermo, Nica Tan, Whitney Whitaker

CONTRIBUTING DESIGNERS

Ikhoor Studio, David Wise

SPECIAL THANKS

Yuki Abe, Courtni Asbury, Sasha Camacho, James Chae, Jacob Davey, Justin Goldberg, Joe Gonzalez, Alexander Ho, Gabriella Koppelman, Drew Millard, Alice Morby, Bentley Nwalupue, Orienteer (Nick, Duncan, Bradley, Kevin), Max Pearl, Elizabeth Renstrom, Elana Staroselsky, Maritza Yoes

FOUNDER

Kevin Ma

ADVERTISING

Huan Nguyen, USA

Steven Appleyard, EMEA

Tiff Shum, APAC

Advertise@Hypebeast.com

Hypebeast.com/advertise

CONTACT

Hypebeast Hong Kong Limited

40/F, Cable TV Tower

No.9 Hoi Shing Road

Tsuen Wan, New Territories

Hong Kong

+852 3563 9035

Magazine@Hypebeast.com

PRINTING

Asia One Printing

Limited In Hong Kong

All Rights Reserved

ISSN 977.230412500-0

13th Floor, Asia One Tower

8 Fung Yip Street

Chai Wan, Hong Kong

+852 2889 2320

Enquiry@Asiaone.com.hk

PUBLISHER

Hypebeast Hong Kong Limited

2023 April

© 2023 Hypebeast

Hypebeast® is a Registered Trademark of Hypebeast Hong Kong Limited

MASTHEAD

8

055

058— 143

146— 235 Citi Bike Boyz Emma Stern GANGBOX Shy’s Burgers Jack Daniels 20 28 36 44 52 Matthew Burgess Peter Sutherland Small Talk Studio Benny Andallo Paris Texas Karu Research Shade Play 58 70 82 94 106 120 132 Jun Takahashi Thug Club Jon Rafman Mowalola Metalwood Studio The McGloughlin Brothers Destroy Lonely 146 158 170 184 196 210 224

Ch. 1 020—

Ch. 2

Ch. 3

Ch. 4 238— 254 Sartorial Sculptures Step-by-Step: Image Making with AI Now Playing Running a Restaurant from Your Home 238 244 248 252

Timepieces by Audemars Piguet + 1017 ALYX 9SM

Matthew Williams has developed a singular design language through his work at 1017 ALYX 9SM and Givenchy. His visual philosophy embraces a style that’s both pared-back and intensely technical, with a knack for highlighting the most luxurious elements of his creations. This ethos is on full display across the 1017 ALYX 9SM x Audemars Piguet collection. The offering marks the Swiss watchmaker’s first collaboration with a fashion designer, and consists of four models—two Royal Oak watches and two Royal Oak Offshore editions—featuring details like a vertical satin-finished dial pattern and a subtle lack of subdial markings. Besides the four retail release watches, Williams and AP created a one-off model made of 18-carat yellow gold and stainless steel that was auctioned off during a launch event and raised $1M USD for the NGOs Kids in Motion and Right to Play.

FROM $73,500 USD AUDEMARSPIGUET.COM

IMAGES COURTESY OF AUDEMARS PIGUET

12

Sleeping Bag by Brain Dead + Nanga

Brain Dead is known for many collaborations, but perhaps its coziest joint product drop of the year was a sleeping bag release with acclaimed Japanese outerwear brand Nanga. Nanga was founded in 1941 by Akira Yokota, who aimed to “explore the unknown” through clothing designed to withstand the elements without compromising on style. The company is revered for producing lightweight puffer jackets, vests, and accessories, while Brain Dead is known for blending references to subcultures like rollerblading, art house cinema, and wrestling in its irreverent apparel and homeware goods.

The partnership materialized in a tactical-yet-elegant sleeping bag with hues of olive and chartreuse adorning its single-quilted, wavy design. Made with 100% nylon padding, 80% duck down, and 20% duck feather, the product features a co-branded label on the compact carrying bag and is ideal for outdoor usage from early spring to late summer.

IMAGES COURTESY OF BRAIN DEAD

13 ISSUE NO. 32

$550 USD WEAREBRAINDEAD.COM

Pebble Match Strike by Houseplant

Houseplant’s Pebble Match Strike is the houseware equivalent of a Swiss Army Knife. The sleek and “incredibly sturdy” cast iron objet d’art is a match striker, match holder, and ashtray—a plumefriendly hybrid design that is equal parts refined and practical. Approximately the size of a grapefruit, but weighing nearly six pounds, the kindling container was crafted for durability and comes with a leather base that

will prevent ring marks or table scratches. The brand notes that strike marks are not only to be expected, but “add character to the piece.” (That said, any scuffs can easily be removed with a dab of olive oil). When both parts of the Pebble are stacked, they appear like a cairn, meaning the offering encourages consumers to bring a little taste of the natural world inside their own abode.

$95 USD HOUSEPLANT.COM

IMAGES COURTESY OF HOUSEPLANT

14

MYSLF Eau De Parfum by YSL Beauty

16

Designed to represent the vast nuances of modern masculinity, YSL Beauty’s new MYSLF fragrance presents a contrasted and multifaceted trail of various notes. Opening with an intensely fresh and vibrant scent of bergamot, a zesty orange blossom is revealed

at the heart, which evolves into a sensual and long-lasting woody accord. The bold fragrance arrives in two sizes—60 ml and 100 ml—along with a refill bottle, marking the brand’s first men’s fragrance to adopt the rechargeable model.

FROM $123 USD

YSLBEAUTYUS.COM

IMAGES COURTESY OF YSL BEAUTY 17 ISSUE NO. 32

CON FIGURA TION Chapter 1

CON FIGURA TION

19 ISSUE NO. 32

UNDOCKED AND UNHINGED

Following Jerome Peel on a high-intensity joyride from Chinatown to the Bronx to learn more about his eponymous label Peels and the movement known as Citi Bike Boyz.

WORDS BY ROSS DWYER PHOTOGRAPHY BY KALIL JUSTIN

20

CREDIT: ANGEL DELGADO 21 ISSUE NO. 32

Ding! It’s a blazing hot July afternoon in the Bronx, and Jerome Peel rings the bell on his 45-pound bright blue Citi Bike as he flies around the edge of a handball court, charges up the 45-degree-angle embankment that borders it, and sails through the air. Thwap! He slaps both tires on the wall above the embankment. Thud! He touches down with the grace of a figure skater after a brief, physics-defying wall cruise, vertical to the sizzling concrete below. Ding! He hits the bell on his Citi Bike once more, an exuberant acknowledgment of victory.

Tricks like these have brought Peel a unique brand of notoriety. He’s the founder of Citi Bike Boyz, an Instagram account-turnedlifestyle-brand dedicated to shredding the streets of New York on the huge, heavy, pay-per-ride commuter bikes that are about as far away from a modern BMX bike as you can imagine. Assuming that Peel grew up BMXing would be sensible but misinformed. In fact, he’s an avid skateboarder and a clothing designer who makes a wide array of Citi Bike Boyz merchandise while also running Peels, his own label known for customized workshirts and jumpsuits, plus collaborations with brands like Vans and X-girl.

The genesis of both Citi Bike Boyz and Peels can be traced to the founder’s love of skateboarding and the DIY mentality it imbued him with. “There were so many things I wanted to do on a skateboard, but I just couldn’t,” he says, sitting on the couch of his sixth-floor walkup apartment in Chinatown, clad in a Peels shirt that was originally made for Bill Murray (it’s quite a story), and speaking with our crew of slightly-winded videographers. (It’s worth mentioning that between the extreme physical exertion of repeatedly jumping Citi Bikes and having to walk twelve flights of stairs in total just to get the mail, Peel is in excellent shape.) “Because I come from a skate background and now have access to this bike, with its bigger wheels and the higher speeds it provides, I look at spots from more of a skater’s mindset than a traditional BMX perspective.”

Peel has spent plenty of time in flight at New York City’s most famous skate spots. His first-ever Citi Bike Boyz stunt was jumping the behemoth double stair set at the LES skatepark on Thanksgiving Day in 2017. “Nobody said anything, nobody yelled, nobody clapped,” he reminisces with a chuckle. “Everyone just looked at me like, ‘What the fuck is this guy doing?’” Since then, he’s hit everything from ledges on Roosevelt Island’s monuments to dirt jumps in Harlem, and, most recently, the famous 145th Street subway gap.

If you don’t know 145th Street by name, you likely know the underground subway station gap by sight. Nigel Sylvester hoisted his bike across it in a famous 2013 photo, and Tyshawn Jones kickflipped it for his Thrasher cover in 2022. Jumping a gap of that nature requires a matador’s level of fearlessness—if you mistime the jump when a train is pulling into the station, you’re a splat on its windshield. And if you come up short on your jump, you risk electrocution on the track’s “third rail,” not to mention the other misfortunes that could befall you from failing to clear the gaping maw between the safety of the platforms. On top of all of that, a rider or skater can’t jump it straight: they have to do so diagonally to build up speed before taking off.

Anyone who’s willing to jump the gap has to have a bit of Evil Knievel in them. Maybe unsurprisingly, Peel once hoodwinked a NY Fox News affiliate into believing he was related to the legendary stuntman. Peel thought through every inch of the jump before he tried it, from his above-ground practice tests to the exact spot where he took off. “I knew I had about 75 feet of runup, plus a turn,” he said of the trick. “I even took off from the exact spot Tyshawn did—I saw where he put Quikrete down to smooth the takeoff.”

23 ISSUE NO. 32

24

“I’LL BE RIDING AS LONG AS I POSSIBLY CAN, NO QUESTION.”

“As I was pedaling at the jump, I was like, ‘Oh, I got this,’” Peel continues, a bemused grin spreading over his face. “I could see the landing, so I felt good, but then when I took off I was like, ‘Holy fuck, this is so far.’ I pulled the bike up as much as I could, and held on for dear life. I’m glad I don’t believe in manifestation, because if I did I’d be dead—I thought I was gonna die and there would be a New York Post headline the next day saying, ‘This idiot got electrocuted and shit his pants trying to jump the subway tracks.’”

Though Peel has a skater’s nonchalance and easygoing attitude, he’s deeply thoughtful about his future and his preferred methods of self-expression. He’s recovering from ACL surgery and pauses for a moment when asked if he thinks he’ll ever get to the point where the juice from jumping Citi Bikes isn’t worth the squeeze.

“I’ll be riding as long as I possibly can, no question,” he says. “But my mindset has changed. I used to be like the bike version of Jaws [pro skater Aaron Homoki], riding as fast and jumping as far as I possibly could. I’d get one shot at everything I did, and if I didn’t stick it, I’d be fucked. Now, I want to be more like [pro skater] Cyrus Bennett, doing real technical, smooth, and creative stuff…instead of risking my life.”

On the clothing front, Peel has adopted the same mindset. Associating his Peels brand with Citi Bike Boyz would give it an instant infusion of notoriety akin to clearing a gnarly gap. (After all, the BMX account has more than twice the Instagram following of the clothing line.) But he wants to keep the two endeavors as separate as possible. The brand’s founding was

both serendipitous and heartfelt. Jerome made the first Peels workshirt for his beloved father—who owns a painting business in Florida—then for his friends, who began demanding their own custom-embroidered shirts after seeing his early creations. A fun side project became a full-fledged business, with workwear produced by a hundred-year-old, family-owned factory in Mississippi and a small Peels team under Jerome, who still heads up the brand’s designs and operations.

Despite Peels’ success, Jerome is in no hurry to put the pedal all the way to the metal. “I’m proud of the meaning and the heart behind what I do with Peels, from the storytelling to the factories I work with,” he says. “It’s a slow-growing thing that I want to be around forever, whereas the Citi Bike Boyz merchandise is much more playful and satirical. They both have their purpose and their own lane.”

As our conversation winds down, Peel notes that he’s aware of the misconceptions around what he does on Citi Bikes, adding that one of the most common is that he’s (somehow) being “disrespectful.” “I’ve never destroyed a bike on purpose…I’ve even fixed Citi Bikes,” he says. “I love hopping on these bikes, showing how accessible they are, and showing that you don’t need to spend $4,000 on a [BMX] bike to get the job done, no matter if you’re riding around or trying to hit a jump.”

Does he have any professional relationship with Citi Bike corporate? Peel’s near-omnipresent grin grows even wider. “They know I exist. Let’s just say I’m an unofficial Citi Bike spokesperson.”

25 ISSUE NO. 32

“LET’S JUST SAY I’M AN UNOFFICIAL

CITI BIKE SPOKESPERSON.” 27

AGE THE

OFA vatar

PHOTOGRAPHY BY MICHAEL KUSUMADJAJA & NAYQUAN SHULER

PHOTOGRAPHY BY MICHAEL KUSUMADJAJA & NAYQUAN SHULER

28

WORDS BY ZACH SOKOL

Emma Stern has strong convictions about her cyber-fueled portraits. “It’s my universe. If you don’t like it, you can go make your own.”

Emma Stern has a balancing act down. The New Yorkbased artist—who specializes in straddling classical painting techniques and hyper-modern, URL-friendly subject matter—knows how to take the piss out of the art world and its trappings, including press interviews like this one, but is dead serious when it comes to the conceptual goals of her paintings.

“I think art should be fun,” she said in a 2022 Artforum interview, before explaining how she couldn’t live with herself if a recent solo show didn’t have at least one painting with a “sexy pirate babe” on a jet ski. The opening of that exhibition, titled Booty! (as in pirate’s booty— get your head out of the gutter!), included customized chocolate gelt piled on the floor in front of her large-scale canvases, as well as a pink stretch Hummer parked outside that matched the palette of the work.

The ironic flourishes might feel like shtick if they weren’t part of the very intentional world-building around Stern’s art. Her practice is an “extended self-portraiture project” where she first digitally renders “lava babies”—her name for the work’s recurring cyberdelic girls. Each

character represents an iteration of herself, which she then depicts in a virtual environment before proceeding to paint them in a style that would make Caravaggio or Balthus do a double take. She says “using traditional processes to articulate very contemporary subject matter” is one way her work aims to reclaim portrait painting, “the 500-year-old tradition of old dead white guys,” and inject it with a fresh, sometimes irreverent, femme perspective.

The iridescent, often ribald avatars may pose like a traditional Renaissance subject, or they might be standing next to a dragon while tipping a cowboy hat. The characters might be doing house chores or brandishing a weapon. Stern says each lava baby is a “crystallized representation of a certain facet of my personality, or some projection of myself,” whether that means a warrior avatar representing strength, or a sullen avatar with a broken leg suggesting vulnerability. “It’s a psychological minefield!”

And even if viewers find the work or how Stern describes it akin to an art canon troll, that’s not her problem: “It’s my universe. If you don’t like it, you can go make your own.”

29 ISSUE NO. 32

30

“I’VE PAINTED A LOT OF WARRIOR BABES, AND THEY TEND TO RESURFACE WHEN I’M FEELING PARTICULARLY STRONG AND WHEN I’M FEELING WEAK. IT’S A psychological minefield. ”

31 ISSUE NO. 32

WHO ARE YOUR FAVORITE ANIMATED CHARACTERS—WHETHER FROM TV, COMICS, THE INTERNET, BRAND LOGOS, OR ELSEWHERE?

I love Daria, who was a character on Beavis and Butt-Head before getting her own spinoff. She is the blueprint. I also love how she is literally “Beavis and Butthead for women.”

HAVE YOU EVER EXPERIENCED STENDHAL SYNDROME, AND IF SO, WHAT TRIGGERED IT?

Only once, and it was when I saw Fragonard’s “The Swing.” People love to hate on it, but the painting is so beautiful. I stan Rococo. The thing that really got me was the woman’s foot; the entire gesture is so perfect, and it rattled something inside me.

ARE THERE ANY SPECIFIC ARTISTS OR PUBLIC FIGURES WHOSE CAREER YOU FIND FOREVER INSPIRING? AND IF YOU COULD SPLIT AN EXHIBITION WITH ANY ARTIST, LIVING OR DEAD, WHO WOULD IT BE?

I would love to have a two-person exhibition with Balthus, though I can’t say I would model my career trajectory after his, given all the sex pest accusations and whatnot. Even so, it is hard to discount his contribution to the canon of painting, and his influence on me personally. I also think our work side-by-side could create a very interesting feedback loop.

DO YOU THINK OF YOUR ART PRACTICE IN TERMS OF “ERAS” OR “PERIODS”? AT ONE POINT YOU WERE PAINTING MORE BLACK-AND-WHITE WORKS BEFORE LEANING INTO VIBRANT COLORS.

I think of it as very spectral. I don’t delineate, as in, “OK, now I’m switching colors and I’m gonna do this for six months and then switch again.” It’s much more organic than that. It’s all a very gradient evolution—slow changes over time that are generally not premeditated. It also has a lot to do with my fluency and confidence in the software I use, because the more adept I am with my tools, the more complex and dynamic the paintings ultimately become.

I’VE ALWAYS FOUND IT INTERESTING THAT YOU USE MODERN TECHNOLOGICAL TOOLS TO DRAFT YOUR WORK, BUT THE ACTUAL PAINTING PROCESS SEEMS TO EMBRACE TRADITIONAL TECHNIQUES AND IS MORE IN THE LINEAGE OF CLASSICAL FIGURATIVE PAINTING. WHAT’S IT LIKE STRADDLING THE LINE BETWEEN DIGITAL AND PHYSICAL PROCESSES?

Using traditional processes to articulate very contemporary subject matter is one of the most exciting and challenging facets of making work this way. My loyalty to oil-on-canvas as a medium is an emotional thing. But stepping outside of that, I feel it also allows this work to exist within the context of the history of painting, and of portraiture specifically, and that recontextualizing creates new meaning for these images, which would be seen very differently if they were, for example, on a computer or phone screen.

It’s not that I enjoy one process more than the other; it’s more complicated than that. I’ve been painting for 17 years, but I feel

like I just learned how to use a computer properly. Painting is, and always will be, my first love, but I rarely find it challenging by itself these days. So adding in the digital workflow keeps me very much on my toes and constantly learning.

HOW IS YOUR ONLINE AUDIENCE DIFFERENT FROM YOUR IRL AUDIENCE?

Different tax brackets.

WHAT’S THE MOST SURPRISING OR MEMORABLE REACTION SOMEONE’S HAD TO SEEING YOUR WORK?

Getting accused of being a pedophile in the Artforum comments section was pretty memorable.

32

33 ISSUE NO. 32

“EACH PAINTING IS AN ITERATION OF MYSELF, SOME crystalized REPRESENTATION OF A CERTAIN FACET OF my personality. ”

VFX BY NICA TAN

VFX BY NICA TAN

YOU EMPLOY RECURRING CHARACTERS THROUGHOUT YOUR PRACTICE. HAVE YOU BUILT ANY MYTHOLOGIES AROUND THEM, EVEN IF JUST IN YOUR HEAD? WHAT MAKES A CHARACTER RICH ENOUGH TO BECOME A RECURRING STAPLE IN YOUR PRACTICE?

I have long referred to this body of work as an “extended self-portraiture project.” By that, I mean that they are my avatars, and an avatar by definition is always a self-portrait, no matter how indirectly or subconsciously. Each one is an iteration of myself, some crystallized representation of a certain facet of my personality, or some projection of myself that is perhaps a defense mechanism. It is true that many of these characters/avatars are recurring. When a character reappears, it’s because something within me is connecting. For example, I’ve painted a lot of warrior babes, and they tend to resurface when I’m feeling particularly strong and when I’m feeling weak. It’s a psychological minefield!

YOU’VE WRITTEN ABOUT THE “INHERENT DRAG ELEMENT TO AVATARS,” WITH THE EXHIBITION BOOTY! BEING YOUR PIRATE DRAG PERIOD. WHAT OTHER ARCHETYPES DO YOU WANT TO EXPLORE THROUGH THIS DRAG LENS?

For my upcoming show opening this September at Almine Rech in London, the work is entirely based on a fictional all-girl rock band called Penny & The Dimes. While perhaps my social media persona comes across as performative (I refer to my online persona as a long-form performance piece), I actually have awful stage fright and hate being in front of a live audience. So creating a rock band, developing each member, and creating a little universe for them has allowed me to live out my rock star fantasy, without having to experience any of the corporeal stage fright that comes along with being a famous musician. That’s what I mean by “drag”—my use of the term has little to do with gender identity, and more to do with creating an “alt,” a proxy upon which to offload your desires, a vessel that is unlimited.

HOW DO YOU KEEP YOURSELF ENTERTAINED WHILE IN THE STUDIO CHIPPING AWAY AT YOUR WORK—PODCASTS? MUSIC? WHAT GETS YOU INTO THE FLOW STATE?

These days I’m listening to a lot of nonfiction audiobooks. When I’m preparing for an exhibition, I do long days in the studio, and can wind up consuming around eight hours of audio content in a day. The long-form format and cadence of audiobooks helps the time pass in a way that music does not for me. Plus, I like to learn while I paint, and I think stimulating the part of my brain that takes in new information helps me physically paint better. Right now, I’m listening to a book called The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations by Christopher Lasch.

HOW DID YOU ORIGINALLY CONNECT WITH BILL POWERS AND HALF GALLERY? HAS HE GIVEN YOU ANY MEMORABLE ADVICE?

I used to watch Bill when he was a judge on that Bravo reality show Work of Art: Search for the Next Great Artist, and spent the next decade manifesting a chance encounter with him, which ultimately did happen. The best advice he ever gave me was, “The best revenge is a life well lived.”

IF YOU COULD EXHIBIT YOUR WORK ANYWHERE IN THE WORLD —EVEN A FANTASTICAL PLACE—WHERE WOULD YOU PICK?

Funny, I was just talking to someone the other day about how I would love to do a show inside one of those underground billionaire bunkers in New Zealand.

35 ISSUE NO. 32

ARTWORK IMAGES COURTESY OF EMMA STERN AND HALF GALLERY

36

FEELING OF FLIGHT

WORDS BY SHAWN GHASSEMITARI PHOTOGRAPHY BY OTHELLO GREY

A conversation with Moya Garrison-Msingwana AKA “GANGBOX” on character-building through fashion.

“How much can you discern about someone if you only see the shit they like?” asks Moya Garrison-Msingwana. Known to many by his alias, GANGBOX, the CanadianTanzanian artist is best known for his fashion-forward illustrations that conflate the nostalgia of early Japanese animations with sartorial subcultures—from gorpcore and streetwear, to billowing samurai kimonos and Euro tracksuits. “If you obfuscate the main signifiers we use to understand one another, there’s a lot of room to experiment.”

Garrison-Msingwana’s early interest in manga and anime sparked a desire to incessantly redraw his favorite scenes. Nowadays, despite being commissioned by the likes of adidas, LOEWE, Stüssy, and The North Face, he still carries the same childlike curiosity as he continues to expand his practice through sculptures, collage, and fine art paintings, while simultaneously probing the visual trappings, iconographies, and fashion styles associated with his subject matter.

Storytelling is at the heart of GANGBOX’s practice, as he first builds each character by writing down ideas in bullet points. He then translates these thoughts into vibrant acrylic paint—conveying references ranging from anime and utility vests, to textile patterns inspired by his father’s East African roots.

Most of GANGBOX’s illustrated characters are featureless in appearance, a device he employs to investigate the human figure while exploring how both personal and shared histories are attached to the clothing we wear. “On a daily basis, we rely on body language and facial expressions to read one another,” says the artist. “I think it’s really fun to play with these types of signifiers we use.”

We caught up with Garrison-Msingwana to understand the processes that underpin his practice, discuss the ties between visuals and community, and highlight his future goals, including a potential animated feature.

37 ISSUE NO. 32

ANIME HAS BEEN A THREAD THROUGHOUT YOUR LIFE, BOTH IN TERMS OF YOUR INSPIRATIONS AND YOUR OWN WORK. CAN YOU TALK ABOUT THE EARLY INFLUENCES THAT SHAPED YOUR ART?

When I was growing up, there was this place in Toronto called Queen Video that my parents would always take me to. Their anime section had everything, from Totoro to the R-rated, insane titles. I wasn’t allowed to engage with any of them, but I always loved looking at the covers and artwork because they were so drastically different from everything else in the store. My parents eventually realized that Studio Ghibli was OK for kids, so I got into that and realized how magical their films are.

I was largely introduced to anime through the “high art” stuff, instead of a common route into the genre like Dragon Ball Z. My best friend’s dad had a huge anime DVD collection, so we would watch Ghost in the Shell and Neon Genesis Evangelion when I was 12. I may have been a little too young, but that transformed my perspective on what animation could be.

WERE YOU ALWAYS DRAWING?

I’m an only child, so once I got hooked on drawing, it was how I’d keep busy and stave off boredom. For a long time, it was a hobby that I showed some talent in. My parents would take me to galleries where I’d life draw, and I had a couple of professional artists as mentors who showed me the tricks of the trade. However, I only started taking it seriously when I had to decide what to do for university.

HOW WOULD YOU DEFINE YOUR PRACTICE? DOES YOUR CULTURAL BACKGROUND—WITH A FATHER FROM TANZANIA AND A MOTHER FROM THE US/CANADA—SEEP INTO YOUR WORK?

I was exposed to the Western approach to art really young, as I grew up in Canada. But going to Tanzania and realizing how much other cultures live and breathe art and design— for example, it’s way more integrated into the clothes they wear—helped me realize that there’s a natural approach to both, with a different, more colorful sensibility than you’ll see in North America. However, I didn’t really get into representing the motifs, patterns, and colors of East African cultures in my work until I was 23.

HOW DID YOU DEVELOP THE GANGBOX ALIAS?

It happened accidentally. I had a group of friends who called themselves CHE GANG and another group that called themselves FRIED BOX, so I fused the two names into one. Since then, I’ve realized it has an actual meaning, which is like a construction toolbox.

The idea of a gang is so romanticized, especially when you grow up loving hip-hop like I did, but it’s such a fraught concept and word. My work is about humanizing and normalizing Black people. The idea of a GANGBOX is almost like a toy box for gangsters—something that’s really fun, light-hearted, and imaginative, but still has that edge to it.

GROUPS, GANGS, OR COMMUNITIES ALWAYS HAVE PART OF THEIR IDENTITY, SUCH AS THE FASHION OR COLORS THEY WEAR, ROOTED IN GEOGRAPHY AND PLACE. EVERYONE SEEKS THAT FEELING OF COMMUNITY AND IDENTITY, AS WELL AS WAYS TO VISUALLY REPRESENT THOSE THINGS. Yeah, it’s a way of belonging. The different ways people try to belong is definitely something that I explore. Even by resisting belonging, you fit into a new category. You always belong somewhere.

38

39 ISSUE NO. 32

“EVEN BY RESISTING BELONGING, YOU FIT INTO A NEW CATEGORY. YOU ALWAYS BELONG SOMEWHERE.”

40

41 ISSUE NO. 32

42

DO YOU WRITE STORY NOTES AROUND THE CHARACTERS IN YOUR WORK, OR DO YOU LET EVERYTHING SPEAK FOR ITSELF?

Both. I write a lot of fragmented notes that are almost like bullet points for myself, as well as the first associations that come to mind. I was taught that making those associations is the best way to start. If I’m given X, Y, and Z, how can I then come up with visual signifiers that incorporate that? Or physical positions of the character that imply these certain feelings?

I think I’ve gotten pretty good at that over the years, because I constantly watch cultural things bloom and die off. Then, I just draw whatever images pop up into my head, or create the visual version of the words I wrote.

MANY TIMES, YOUR FIGURES ARE VEILED. CAN YOU ELABORATE ON THE CONCEPTUAL REASONS BEHIND THIS?

On a daily basis, we rely on body language and facial expressions to read one another. I think it’s really fun to play with these types of signifiers we use to belong. How much can you discern about someone if you only see the shit they like? You’re playing I Spy with their projected identity if you do…But if you obfuscate the main signifiers we use to understand one another, there’s a lot of room to experiment.

CAN YOU DISCUSS YOUR PROCESS BEHIND CREATING AN ARTWORK FROM START TO FINISH?

I had a teacher in school who I really didn’t get along with, but he did give me some valuable advice: “Living is really important.”

Even if you’re working super hard on something or have a deadline, make sure you have time to go on a walk or clear your mind and experience things. I often find myself taking big breaks between working on projects now, because it gives me more time to genuinely think about who I am and what I’m contributing to this world. Then I can come back to making artwork with a little more clarity.

I start off that way, just thinking and existing. Then I sketch a lot and will loosely place down ideas or shapes that I think are special or could have meaning. If it’s something that I’m making for myself, I don’t really know what it means until it’s done. I might do a color study if I’m feeling particularly organized, which is rarely the case. Then I just paint, sometimes with Procreate on the iPad to mess around with things, but I prefer to sketch analog and paint with acrylics.

SOCIAL MEDIA HAS RAPIDLY ACCELERATED OUR THIRST FOR CONTENT. HOW DO YOU INTERACT WITH THIS FEVERISH PACE IN YOUR OWN PRACTICE?

I don’t try to keep up. The pace I’m comfortable with is the pace I make the best work at. I don’t think I owe it to anybody to make artwork just because I want to keep up my Instagram followers or because I need money. There are enough people out there who are aware that great things take time and energy. You can’t force or fabricate that, and spreading yourself thin is not a good solution. It can pay off to just do things your way. Like-minded people will connect with what you do, no matter what.

DO YOU HAVE OTHER GOALS WITH YOUR ARTWORK BESIDES EXPRESSING YOUR CULTURAL INFLUENCES?

Yeah, there are overarching themes and things I spend time thinking about regardless, like identity. I think about a lot of the gray areas in life and the nuances that exist in places. I also like to explore maximalism. We’re all processing a ton of information all the time, and translating that into my work is important because I think it reflects the time we live in. I also want to comment on political ideals and bigger issues that we are facing as humanity with my art.

DO YOU WANT TO DABBLE IN FULL ANIMATIONS IN THE FUTURE FOR, SAY, AN ANIME? WHAT WOULD A DREAM PROJECT BE?

Definitely. I’ve done quite a variety of work over my career and I plan on working on writing and illustrating my own manga that will hopefully, in an ideal world, include having my characters voiced and animated.

43 ISSUE NO. 32

STILL SIZZLIN’

WORDS BY ZACH SOKOL

PHOTOGRAPHY BY JUSTIN SARIÑANA

WORDS BY ZACH SOKOL

PHOTOGRAPHY BY JUSTIN SARIÑANA

44

SHYAN ZAKERI IS THE GO-TO “BURGER GUY” FOR POP-UPS IN DOWNTOWN NEW YORK. BUT AFTER THREE YEARS OF SLINGING DOUBLE-STACKS OUTSIDE, HE’S ASKING HIMSELF WHAT COMES NEXT BEYOND TWO BUNS.

Shyan Zakeri knows he’s “the burger guy,” but he’s getting a little burnt out on buns.

Over the last few years, the 27-year-old behind food pop-up project Shy’s Burgers has become the go-to grill maestro for any New York menswear brand or shop throwing a party. He’s lugged a flat-top grill to events hosted by Drake’s, Noah, MR PORTER, Drug Store, Colbo, and Mohawk in LA, as well as commandeered the kitchen for one-nightonly takeovers at buzzing eateries like Foster Sundry, Doubles, Gem, Babs, and the newly-revamped Triple Decker Diner.

45 ISSUE NO. 32

Despite having almost no formal food training, Zakeri is known for crafting an elevated take on fast food burgers (he eschews the style of inch-thick slabs of ground sirloin found at places like The Odeon). His thin, greasy, double-stacked patties get gobbled up instantly, often selling out hours before a pop-up ends. There’s rarely any promotion for Shy’s Burgers events, and Zakeri notes that, until recently, he hadn’t posted a food pic on Instagram in nearly a year. However, the word-of-mouth approach hasn’t prevented a massive line from forming anywhere he’s holding an offset spatula.

46

“THERE’S THE DESIRE TO HAVE SOMETHING THAT’S YOURS. YOU WANT TO MAKE A MARK.”

47 ISSUE NO. 32

In late 2022, he told an interviewer he’d cooked at least 10,000 burgers since starting Shy’s during the last leg of the pandemic—and that number has probably doubled since. The operation started with Zakeri and his friends cooking out of their apartment kitchen, lowering plates of food (with a mini beer to boot) in a bucket out the window to customers waiting on the street. After grilling at a barbecue thrown by the podcast Throwing Fits, he started getting tapped by various clothing brands to serve food at their own parties, often becoming the main attraction. While it can be trying for small businesses to make a name for themselves at the beginning, Shy’s Burgers never had that problem. “Nah, not for me,” Zakeri says with an assured chuckle. “It was cracking from the start, immediately successful.” Regardless of his comfortable position as a munchies magnet and lowkey bellwether for clothing boutiques and restaurants on the rise, the self-taught chef is hungry for the next course in his culinary journey.

“I don’t want to be the fucking guy who’s cooking burgers outside for the rest of my life. I’m just bored of it,” he explains over a beer near his apartment in Bed-Stuy. “I started Shy’s over two years ago, and if I don’t have a next step by the end of the year, I’ll probably not do this anymore. I want to level up.”

Zakeri is well aware of the hurdles and headaches that will arise if his brand makes the leap to something bigger, like, say, opening a brick-and-mortar restaurant, but it’s something he actively thinks about nonetheless. “New York City is probably the most hostile city in the US for small businesses, particularly restaurants and bars. While doing a pop-up skirts a lot of that red tape, there’s a reason people cook in restaurants,” he explains, noting the financial instability and health code violations that come with a makeshift—and often plein air food enterprise.

As a way to dip his toes in the industrial-grade deep fryer without signing a lease, Shy’s Burgers has increasingly focused on restaurant takeovers instead of outdoor cookouts. (He also does private gigs to help pay the bills.) During an event in early August at Foster Sundry in Bushwick—his longtime meat purveyor—Zakeri had about ten items on the menu, including tahini crunch beans with peanut chili chutney, a double tomato salad, and wagyu bologna sandwiches topped with “addictive cabbage,” as well his original double patty (“The #1”).

He describes his new offerings as “food I want to eat—just really simple stuff, but interesting.” Zakeri points to restaurants like Superiority Burger, Bernie’s, Scarr’s, and Cafe Mutton in Hudson as inspiration points, alongside his friends who run the Vietnamese pop-up Ha’s Đặc Biệt. The sentiment is reminiscent of the Anthony Bourdain line from Kitchen Confidential: when chefs leave the restaurant, all they want to eat is unfussy but masterfully-executed home cooking.

Zakeri views this kind of comfort food as a “niche that you don’t currently see in New York,” largely due to how TikTok has influenced dining and spurred a movement of menus that favor spectacle over substance. He says social media has “fucked this city up in so many ways. Restaurants have become washed and there’s a less critical consumer because of it.” Shy’s Burgers, however, is diametrically opposed to culinary bells and whistles, with the founder again emphasizing, “I don’t make food for Instagram.”

Zakeri notes that the one-off guest takeovers are trial-anderror “proofs of concept,” qualifying that the menu at Foster Sundry was “a little all over the place…we’re clearly figuring out the throughline as we go.” He also admits it can be frustrating to be “beholden to other business’s waitstaff, systems, and

48

49 ISSUE NO. 32

“THE BURGERS ARE AN EXTENSION OF ME AND I’M INTRINSICALLY TIED TO THEM, WHICH IS AN INTERESTING IDEA TO GRAPPLE WITH.”

50

structures.” Still, he’s more “satisfied and content” now that he’s cooking at proper restaurants with functional bathrooms and appliances. There’s also the gratification of being able to pay his friends to help, in addition to having the resources to execute menu ideas he’s had lingering “in the back of my head for two years.” The pop-up and takeover model can’t last forever, though, and Zakeri wants to build something more enduring.

“What is Shy’s beyond two buns?” he asked in an Instagram post over the summer. “The burgers are an extension of me and I’m intrinsically tied to them, which is an interesting idea to grapple with,” he explains later, especially as he’s not a trained

chef who can easily slide into a gig at an established restaurant or secure the capital to open his own. In a telling moment, Zakeri posted a response to a meme roasting the omnipresence of smash burgers sold at brand activations throughout the city. “Give me a place for me and my friends to cook normal food inside [regularly], and I can end this once and for all,” he wrote.

As we finish our beers, Zakeri underscores these future aims: “There’s the desire to have something that’s yours. You want to make a mark.” When the next iteration of Shy’s Burgers, whatever it may be, manifests, you can bet there will be a line on opening night.

51 ISSUE NO. 32

THE CRAFTING

the archives of Jack Daniel’s

Apple Classic Remix collection.

Exploring

Tennessee

WORDS BY FELSON SAJONAS PHOTOGRAPHY BY MICHAEL KUSUMADJAJA

52

A CLASSIC OF

Independent brands and designers craft with quality in mind. Slower manufacturing means well-made products for mindful people—which in turn fosters meaningful connections amongst considerate communities, the antithesis of modern-day mainstream fashion’s “here today, gone tomorrow” mindset. Giant companies move at a feverish pace, increasing unneeded supply to meet non-existent demand. In the process, these brands are doing more harm than good to our environment (and our moral fabric) in the quest for global dominance. To give the small brands and artisans a leg up in their pursuit, Jack Daniel’s Tennessee Apple Classic Remix program fully supports arts and culture, championing independent creators by providing them with the funds and tools necessary to succeed in one of the world’s most competitive industries.

From 2021 to 2023, Ouigi Theodore of Brooklyn Circus, Sheila Rashid and Justin Mensinger (founders of their eponymous labels), Corianna and Brianna Dotson of Coco and Breezy, Nigeria Ealey of TIER, and designer Kristopher Kites were chosen to craft collections inspired by Jack Daniel’s Tennessee Honey and Tennessee Apple whiskeys. 100% of the sales from their designs, which are now up to $100,000 USD, were matched by Jack Daniel’s and shared amongst program winners in 2023. By looking through the Classic Remix Collection archives, you’re given a sense of how these designers’ slow, thoughtful approach is more important than ever. Their creations not only represent the future of responsible design, but serve as a blueprint of how creative communities can give back to younger generations in need of such opportunities.

In 2021, Chicago-based designer Sheila Rashid and Brooklyn-based designer Ouigi Theodore of Brooklyn Circus were tapped by Jack Daniel’s to create bespoke apparel for the Classic Remix Capsule Collection. Inspired by the uniforms of Jack Daniel’s distillery workers, Rashid’s overalls were cut from resilient fabric and designed with a honeycomb pattern plus branded embroidery at the back. The unisex design perfectly echoed Rashid’s style, which blurs the norms of gender identity. Theodore’s varsity jacket, on the other hand, embodies his trade as a tailor. The limited edition piece, which sold out instantly at launch, reflects the careful craftsmanship for which Brooklyn Circus is known with its premium fabrics, patches, and embroidery—all representing timelessness and purposeful design.

53 ISSUE NO. 32

PLEASE DRINK RESPONSIBLY.

WHISKEY SPECIALTY, 35% ALC. BY VOL. (70 PROOF.) JACK DANIEL DISTILLERY, LYNCHBURG, TENNESSEE.

PLEASE DRINK RESPONSIBLY.

WHISKEY SPECIALTY, 35% ALC. BY VOL. (70 PROOF.) JACK DANIEL DISTILLERY, LYNCHBURG, TENNESSEE.

54

JACK DANIEL’S TENNESSEE APPLE IS A REGISTERED TRADEMARK. @2023 JACK DANIEL’S

Corianna and Brianna Dotson of Coco and Breezy were joined by Justin Mensinger for Jack Daniel’s Classic Remix initiative in 2022. “When someone wears a piece created by me, I want them to know the time and love that was put in the product,” Mensinger said of his vision. As an artist and clothing designer, Mensinger pieces together discarded fabrics or unwanted apparel for his creations. It’s a time-consuming process, but his works have garnered praise and admiration in the world of DIY fashion. For his Jack Daniel’s Classic Remix design, the LA-based creative produced a bucket hat and hoodie in his signature patchwork style. Afro-Latina identical twin sisters Corianna and Brianna Dotson founded their eyewear company Coco and Breezy in 2009. It took time for Coco and Breezy to master the art of crafting sunglasses, and according to them, it took an even longer time to raise the capital to launch their brand. Timing is key to any independent pursuit and Coco and Breezy learned that no matter how long it takes, taking action is what leads to realizing any entrepreneurial dream. In partnership with Jack Daniels, Coco and Breezy modified their “Cornell” model sunglasses to reflect the look of the Tennessee Apple whiskey bottle, from the gold trims to mimic the whiskey inside, to the green temples made to reflect the bottle’s label.

Jack Daniel’s most recent Classic Remix initiative involved Kristopher Kites and Nigeria Ealey. Through his meticulous eye

for detail, Kites created a chunky Cuban link-style chain in a hand-sculpted lucite material, along with the use of 3D printers and self-made compounds. The resulting product has an iridescent green and honey-colored hue, finished with a fastening system showcasing Jack Daniel’s branding. “I’m always learning and conceptualizing with my hands,” Kites explained. “Every piece starts by hand, and once I know what I’m going for, then things start to trickle down on the manufacturing side.”

As for Ealey, the TIER creative director created unisex monochromatic jackets and a set of joggers in a green and honey colorway. As one of the founding members of the Art Never Dies Foundation and Artrepreneur Festival, Ealey and his partners look to provide “up-and-coming talents in the arts with resources, funding, and programming” to help them overcome the hurdles that often impede emerging and established creatives in the space.

Jack Daniel’s started their Tennessee Apple Classic Remix program in 2021 to provide grants to the next generation of streetwear designers. The initiative continues to this day as a way to highlight the brand’s commitment to arts and culture, fostering a creative community that supports the spirit of independent design.

55 ISSUE NO. 32

ACCE LERA TION Chapter 2

ACCE LERA TION

57 ISSUE NO. 32

WORDS BY ZACH SOKOL

WORDS BY ZACH SOKOL

58

PHOTOGRAPHY BY COREY OLSEN

Artist Matthew Burgess has established himself as “the custom chain-stitch guy,” but there’s more than meets the eye in his psychedelic embroideries-on-canvas.

59 ISSUE NO. 32

Matthew Burgess isn’t a household name in the art world quite yet, but the 27-year-old has the type of cult audience that can pinpoint one of his canvases from a group show or Instagram’s Explore Page without hesitation. “My work is instantly recognizable to people who are aware of what I do,” he’ll tell you.

Once you’re indoctrinated to Burgess’ pupildilating, large-scale embroideries on canvas, the same familiarity will likely be branded into your frontal lobes, too. His art practice revolves around sampling vibrant (and typically psychedelic) animation and pop culture detritus— such as stills from Alice in Wonderland, Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, Natural Born Killers, or Aeon Flux—and incorporating traditional cross-stitching methods alongside oil paint

60

in a way where the line blurs between the two techniques.

The melding of the two processes has an effect on the viewer that’s akin to picking up a can of soda that you think is empty, but is actually full—a positive and undeniably trippy version of experiencing the Uncanny Valley. In one unnamed 68” x 54” canvas, the Disney iteration of Alice is pictured in a field of daisies. The flowers in the foreground, as well as parts of her clothing, are embroidered, while the flora in the background is painted. From a distance, it’s hard to tell where the thread ends and the oil begins, and Burgess says, “playing with that relationship is the foundation of the art I’m trying to create.”

61 ISSUE NO. 32

It’s a slow and time-consuming process to make these works, but Burgess’ signature approach has won him notable fans and collectors, including Metro Boomin (who bought his very first painting) and Brian Procell (who has a canvas on display in his Lower East Side showroom). And though his interests have shifted away from fashion, he made waves earlier in his career by designing custom merch for both Drake and Lil Uzi Vert —projects that bolstered his reputation and led to him pursuing art full-time.

By spotlighting single frames from classic animation, Burgess’s art encourages us to consider the craft and detail that goes into the thousands of animation cels that are woven together to make an entire movie. Or to appreciate the design of the blotter art pictured on the acid tab you might put on your tongue. His methodology, and the idiosyncratic sensation it inspires, forces viewers to slow down and really digest imagery that we’re familiar with to the point where it feels new again.

62

63 ISSUE NO. 32

YOU’VE SAID THAT YOUR MOM AND GRANDMOTHER HAVE A RELATIONSHIP WITH CROSS-STITCH AND EMBROIDERY. WHAT TECHNIQUES DID THEY DIRECTLY PASS ON TO YOU AND HOW HAS IT INFLUENCED YOUR ART PRACTICE?

Embroidery and knitting were a recurring aspect during my childhood. My grandmother knitted as a hobby. She would give my whole family—eight to nine of us—sweaters, socks, hats, and blankets every year for Christmas. These sweaters had beautiful winter imagery, like snowflakes and sleds. She won best knitter at the state fair many times, and being gifted these items every year was a blessing; they were made with love.

My mother took inspiration from her, and learned how to cross-stitch embroider. Cross-stitching is a method of embroidery where each stitch is hand-sewn in an “x” pattern, hence the name. It often incorporates folky American imagery: barn animals, flowers, colonial houses, trees, family heritage, etc. The works my mother would make are everywhere throughout my house. Growing up, they were unimportant to me and looked very bland. However, it was a hobby that she loved, and I had the opportunity to observe how long it took to make these things. I’ve watched my mother spend multiple years on a single piece. Crossstitch embroidery takes forever, and when you make a mistake, you have to spend days retracing your steps.

When I first dabbled with making clothes, I made some cross-stitch box logos. I knew immediately it was too time consuming to incorporate this technique into making clothes, so I found a sewing machine on Craigslist, taught myself how to use it, and learned how to make applique patches.

WHEN YOU MOVED TO NEW YORK IN 2016, YOU BEGAN WORKING AT KNICKERBOCKER FACTORY IN RIDGEWOOD, MAKING MASS-PRODUCED HATS. WHAT DID YOU LEARN FROM THIS JOB AND HOW DID IT FURTHER YOUR CAREER?

Working at Knickerbocker was life-changing. I was at a crossroads in my life and knew that I had to take sewing seriously, or not do it at all. Knickerbocker was a place I had found through my friend Phil. In this space, there was a small group of people that sewed all day, making hats and various other items. I wanted to work there so bad. I had court one day in NYC after getting a ticket for drinking in public, so I took the train from Connecticut, where I’m from, and ended up messaging someone there, asking if I could come visit. I told the people there my story and they offered me an internship for three months.

At Knickerbocker, I was surrounded by like-minded people who showed me the way. The first week, I met Kelley Hice, an artist, who essentially became my best friend and mentor for life. Kelley was, and still is, my biggest inspiration. These people taught me everything—how to use, maintain, and fine-tune multiple types of machines, as well as all the skill aspects that are involved with manufacturing clothes. I learned how to make baseball caps, and that's when I really learned how to sew. It’s also where I eventually taught myself how to chain-stitch on a machine that just collected dust in the factory space.

WITHIN A COUPLE YEARS, YOU WERE MAKING MERCH FOR DRAKE AND LIL UZI VERT. HOW DID THOSE COLLABORATIONS COME ABOUT?

This was a time in my career when I was going in on custom apparel and finding fun ways to advance my craft as an embroidery artist. Once the winter season came around, I was embroidering all these “niche,” “pop culture,” and “vintage core” graphics onto sweaters and jackets, establishing myself as the custom chain-stitch embroidery guy. At the time, I was also making these large, grayscale, embroidered portraits on Levi’s jackets, specifically portraits of Princess Diana and Cliff Burton. Drake’s stylist asked for a handful of custom portraits on hoodies, as well as some one-off merch for the release of his Scorpion album. Andrew Barnes, one of my mentor figures, painted artwork concepts for the album, and it was my job to embroider them onto sweaters and jackets. I ended up making many sweaters for Drake and his team. I found myself having to think about custom sweaters all the time just to make a living. It became my primary means of making money—tapping into these niche, graphical references, and sharing them on social media.

WHAT ABOUT LIL UZI VERT? WERE THESE COLLABORATIONS A WAY TO BUILD YOUR PROFILE AS YOU TRANSITIONED MORE FORMALLY INTO THE FINE ART GAME?

I'm a big fan of Lil Uzi Vert. I remember the day he released his single “Futsal Shuffle.” I was on a lunch break, and I had the song playing on my phone. I

64

looked down at the single artwork, an enigmatic anime style portrait of Uzi, and I was like, “Oh, too easy.” That evening, I finished embroidering the art onto the sweater and shared it online. The internet freaked, and the next day Uzi and his team reached out to me to acquire it, as well as extend an offer to design some merchandise for Eternal Atake

Receiving that kind of recognition is something I never expected when I first moved to the city; it was almost too surreal. However, I lost interest in fashion and working on clothes. People are only willing to spend so much on a sweater. I found myself consistently disappointed in the people and the market of the fashion world. It was a valuable step in my career that I’m very grateful for, but I had run the sweater game into the ground, and found myself needing to find a different way to expand and progress my embroidery. I had been wanting to experiment with canvas works for a while, so around that time I embroidered and stretched my first canvas. My mentor Kelley told me to pick up a paint brush, and paint around the embroidery. This was an essential development in my career, and to this day, is the foundation of the art that I make.

65 ISSUE NO. 32

66

67 ISSUE NO. 32

68

YOU’VE NOTED THAT YOU DO NOT CONSIDER YOURSELF A “PSYCHEDELIC ARTIST,” DESPITE REFERENCING LSD AND MUSHROOMS IN YOUR WORK. HOW WOULD YOU DESCRIBE YOUR ART’S RELATIONSHIP WITH PSYCHEDELIA AND DRUG CULTURE?

My first art show was called Bicycle Day, in celebration of Albert Hoffman and the first LSD trip. Essentially, I reproduced ten of my favorite examples of blotter art on a large scale. It was a simple concept that I could relate to, having seen many examples growing up. Blotter art functions as a means for street chemists and dealers to differentiate various LSD batches.

Blotter art is undeniably psychedelic art. It inspired me to explore my creativity on canvas, and teach myself to combine painting and embroidery. I would later re-reference and experiment with these motifs, but not as directly. For example, I'd find blotter art that looked like a floor tile, and paint that as the ground or wallpaper of an image.

I also loved how some cartoons have psychedelic undertones. There's a Disney short, Pink Elephants on Parade, which seems like something out of a bad trip. The imagery is dark and unsettling. It’s wild to me that this was made by an animation studio, and incorporated into a popular children's movie. I loved it, though, so I had a period early in my career where I would reference the elephants for my figures. My current work is just ripping old animation and cartoons. I don't think about psychedelics or drug culture when I make something. I'm just thinking about exploring the relationship between an embroidered figure and a painted background.

HOW DO YOU DECIDE WHICH POP CULTURE IMAGERY TO REFERENCE IN YOUR WORK, WHETHER VINTAGE ANIMATION AND COMICS, OR STILLS FROM CULT FILMS?

Image sourcing is essential to my work. I've discovered that much of my work reminds me of old animation cels, so I began using them for inspiration at one point. I like how there's a cel-style dynamic involved when I place an embroidered figure against a painted background. With embroidery, I’m limited to animated subject matter because that’s what I think looks the best. Embroidery is great for strong solid colors, but difficult when blending various colors. I’m also limited to a palette of 80 or so tones that my thread maker can supply me with. There are no good flesh tone-colored threads. Flesh has undertones and textures that I’m unable to achieve with embroidery. For that reason, I generally choose animated subject matter. The goal in the future is to be less and less referential, but the time will come when I'm ready.

WE TALKED ABOUT HOW YOU STRIVE TO FIND A BALANCE BETWEEN EMBROIDERY AND PAINTING IN YOUR WORKS, ALMOST IN A WAY WHERE THE LINE BETWEEN THE TWO BLURS. CAN YOU EXPAND ON THIS?

I like exploring the dynamic between the embroidery and the paint; playing with that relationship is the foundation of my art. Generally, the figures in the foreground are embroidered so the embroidery comes forward. The texture and colors are very prominent and pop off the canvas. There are instances when, from afar, it’s indistinguishable to tell where the painting and embroidery start, end, or merge. I’ve found that this is what most people like about the things I make.

When I work on a large canvas, I can do so much more than when I designed clothes, especially when I combine the embroidery process with painting. This is what makes my work unique to me. My work is instantly recognizable to people who are aware of what I do. Francis Bacon said to really push the art game, one has to do something that is really different to be any good. One has to develop their own techniques, which is what I believe I’ve done.

69 ISSUE NO. 32

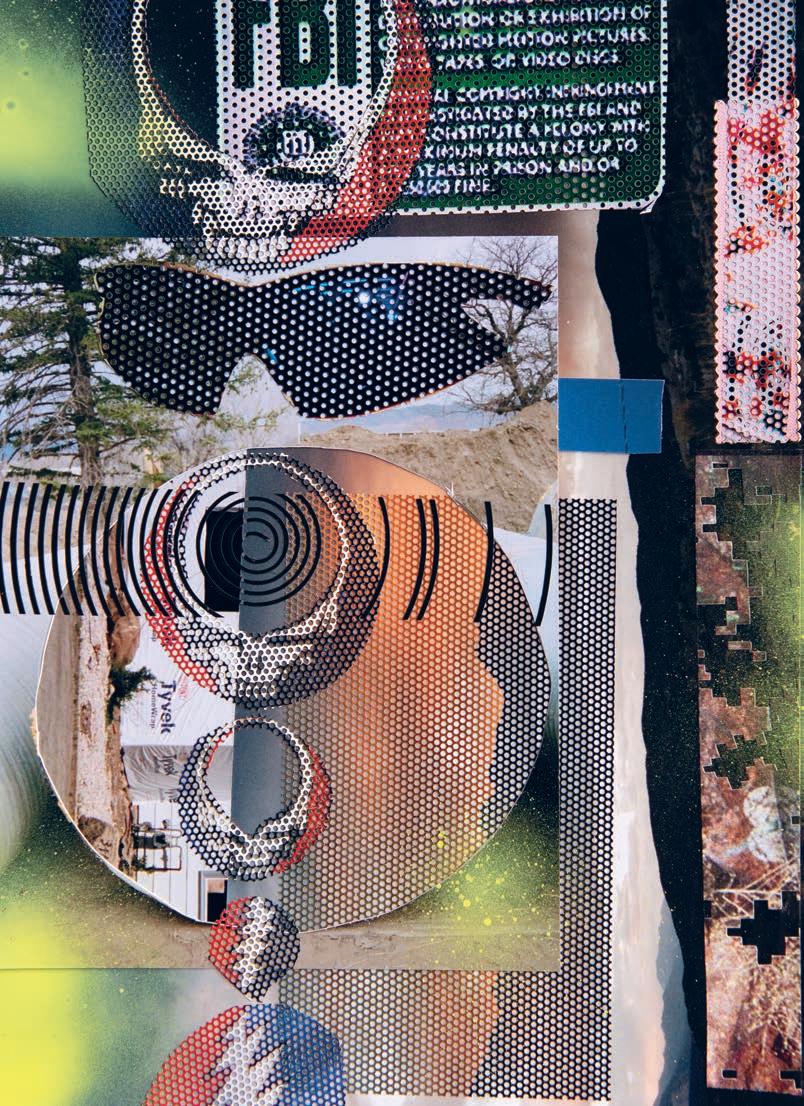

THE ZEN TRIPPER

THE LONGTIME CULT-FAVORITE ARTIST PETER SUTHERLAND MOVED TO RURAL COLORADO DURING THE PANDEMIC. NOW, HIS PRACTICE FEELS REFRESHED AND THE MIXED MEDIA MAESTRO IS TRYING TO IMBUE HIS WORK WITH A PURE, CHILDLIKE ENERGY.

WORDS BY ZACH SOKOL

ARTWORK BY PETER SUTHERLAND

70

71 ISSUE NO. 31

Peter Sutherland was the godfather of downtown New York for over 20 years. The mixed media artist cut his teeth in the late ‘90s and early ‘00s as a photographer and cinematographer with a knack for turning his lens towards skaters, musicians, and artists on the precipice of blowing up. He released a number of zines and limited edition books, such as Autograf (2004), a seminal survey of New York graffiti writers, and Pedal (2006), a photo and video document of bike messengers, while also collaborating with cult fashion brands like Bape and Colette (RIP).

As Sutherland grew older, his practice evolved into sculpture, painting, and collage works, often fused with imagery he shot over the years. And while he’s participated in dozens of solo and group exhibitions, Sutherland may be best known as a galvanizer of community and big brother figure to younger creatives, with his Instagram regularly featuring candid sidewalk pics of his diverse range of friends and peers alongside the tag #StreetLordz.

Sutherland’s art practice has consistently explored “things that illustrate a boundary between nature and civilization,” exemplified in his photobook Buck Shots (2007), which showcased deer in both pastoral and suburban settings until the line blurred between the two. He says he liked to make imagery in natural settings and bring it back to urban ones. During the pandemic, however, he and his family relocated to Salida, Colorado, leaving a salient gap in the social fabric of the East Village, but also reinvigorating his approach to art-making in the process.

“I was hardcore in the mix in New York for over 20 years, just going for it. But living in Colorado has been interesting,” the 47-yearold says. “Out here I can be a ‘real artist’ in a way, not splitting my time with socializing and the constant pressure to generate income. It’s been cool to see how this lane works.” Plus, he notes that “any sort of momentum for having a ‘career’ has been able to continue here,” such as recently getting tapped to design skate decks for GX-1000. “Maybe being out of sight makes ‘em want you more.”

Lately, Sutherland’s been going in on large-scale collages that layer scraps of photos, found imagery, and “intentionally juvenile” mark-making reminiscent of both graffiti and the paint pen writing you might see on grip tape. He describes the confluence of material as “upcycling my work, me on my journey to make a painting that feels resolved,” a word he comes back to more than once. “All those collages and paintings are me chipping away and messing with the imagery until it pops or feels resolved.” Recurring visuals include Grateful Dead “stealie” skulls, tagged cars, spirals, digital clocks, and patterns made by weather phenomena, as well as depictions of subcultures like acid house and skating as they originally appeared during the Gen-X era.

“Even though those things are throwbacks, they're still kind of relevant,” he explains. “All youth culture movements eventually become similar. They're just different groups, different factions, pushing their own aesthetic to a point that is exciting”—and bigger than the sum of their parts.

While he’s not currently in the thick of that youth culture like he was during his NYC halcyon days, Sutherland says his goal is to make art with a “childlike energy mixed with an older head energy.” He describes watching his son paint and hoping to incorporate the same “carefree, see-what-happens, there’s-no-plan” attitude into his own work—a pure methodology that comes from the id. “That’s what I want outta my stuff; I’m always trying to get back to that early energy.”

72

“WHEN I WATCH MY SON PAINT AND SEE HOW FREESTYLE IT IS, I WANT THAT ENERGY—THAT CAREFREE, SEE-WHATHAPPENS, THERE’S-NO-PLAN APPROACH.”

73 ISSUE NO. 31

74

“I WAS HARDCORE IN THE MIX IN NEW YORK FOR OVER 20 YEARS, JUST GOING FOR IT. IT’S BEEN KIND OF COOL TO SEE HOW THIS OTHER LANE WORKS, TOO.”

76

77 ISSUE NO. 31

80

WORDS BY ZACH SOKOL

WORDS BY ZACH SOKOL

82

PHOTOGRAPHY BY CHRISTIAN FILARDO

THE NYC BRAND, KNOWN FOR ONE-OF-ONE GARMENTS WITH CUSTOM ILLUSTRATIONS, IS MOVING INTO THE WHOLESALE SPACE. WILL ITS FOUNDING SPIRIT BE KEPT ALIVE AS IT CONTINUES TO LEVEL UP?

83 ISSUE NO. 32

n another life, Nick Williams and Phil Ayers could have been renowned tattoo artists. The duo behind NYC-based clothing brand Small Talk Studio built its name making one-of-one garments embossed with hand-drawn illustrations and embroidered graphics. They’d drop a 24-hour custom order window on their Instagram, and the lucky few who nabbed a ticket would send the boys a list of visuals and personal reference points. Ayers and Williams would then mix and match the customer’s picks with a medley of “old faithful” images—essentially their version of tattoo flash sheets—that they’d painstakingly draw on denim pants, button-downs, and trucker jackets.

The illustrations form a constellation on a given garment, akin to someone who’s spent years getting inked until they have full sleeves and backpieces. And like tattoos, Small Talk drawings are bold statement pieces chock-full of imperfections that reveal the human hand, ensuring that each order is truly intimate and inimitable. Their visual vernacular ranges from timeless iconography like cupids, pin-up girls, botanical images, and baby devils, to niche cuts like vintage Tang logos, bootleg Bart Simpsons, and the 1996 Montreal Jazz Festival poster. The designs “almost turn into an I Spy composition,” says Ayers. The throughline amongst the disparate imagery is the customer’s personal interests (and Small Talk’s signature touch).

There’s an “element of trust between the customer and us,” the duo says. “They don’t know what we’re actually gonna draw on their garments, so it’s a big leap of faith,” one that results in a cherished piece that no one else in the world has.

Small Talk’s approach has led to a true-blue fanbase, including repeat customers, as well as a commission from Virgil Abloh before his tragic passing. Their reputation also catalyzed collaborations with brands like Adish, Karu Research, Carhartt WIP, and Gitman Vintage, where they were offered free reign to take the established labels’ garments and “freak ‘em” in their own style.

After a few years of focusing on customs, Williams and Ayers opened a studio on the 14th floor of a pre-war building, smack-dab in the heart of Manhattan’s Garment District. The space is cozy, well-lit, and adorned with Small Talk’s own illustrations on the walls and furniture. It’s also where they keep the designs for their first two cut and sew collections, one for Fall/ Winter 2023 and the other for Spring/Summer 2024.

Both collections include around two dozen unisex designs with few illustrations but lots of secondary treatment to the fabrics, such as dyes and embroideries. The fall release features a silk mohair jacket and wool pintuck trousers that Williams describes as a “psychedelic Western vibe,” whereas the spring collection was inspired by “arbor-glyphs,” or markings on trees, which manifests in garments like pants made out of crinkled gauze fabric that resembles the texture of bark. Small Talk still plans to continue its bespoke business, but the goal with the wholesale items is to “find a visual language that bridges the gap between the all-over super graphic customs and [the designs] that are a lot quieter and more understated.”

The clothes will be offered in stores like Blue in Green, Colbo, and Cueva in New York, Super A Market, Hollywood Ranch Market, and Domicile in Japan, as well as boutiques in Los Angeles, Philadelphia, and Melbourne. Williams and Ayers want to establish “long-lasting relationships with more independent retailers, rather than immediately going for the big fish.”

Ultimately, the duo strives to make clothes that are “too personal to give away,” heirloom fits that are versatile and can be dressed up or down. And like a good tattoo artist, the source of each design should be immediately recognizable: a Small Talk Studio joint.

84

85 ISSUE NO. 32

86

RIOR TO STARTING SMALL TALK STUDIO, DID EITHER OF YOU HAVE DESIGN OR FASHION EXPERIENCE?

Phil Ayers Not traditionally. I worked at Pilgrim Surf + Supply for about three years and was doing freelance illustration with a few different clothing brands. But before that, I worked in a totally different field and was just doing painting and illustration on the side. Both of us come at Small Talk from an art background, and that informs our approach to apparel design.

Nick Williams We have a bit of an outsider perspective since we’re not traditionally educated in garment design. That flips the equation a little bit. When I moved to New York, I was working for a housing nonprofit and teaching art to adults at this supportive housing facility in Brownsville. For about eight months, I would go there three days a week and teach, and then work on Small Talk on my off days. Eventually, Small Talk got to the point where I could do it full-time.

WHAT LED TO SMALL TALK BEING SUCCESSFUL ENOUGH TO FOCUS ON IT EXCLUSIVELY?

NW The transition from part-time to full-time happened really fast. It was basically a combination of good press—like an interview with Blackbird Spyplane and then a profile alongside a couple other designers in the Wall Street Journal and also getting commissioned to make a custom piece for Virgil Abloh. This all happened in the summer of 2020 and it brought a lot more attention to the operation.

I basically spent the summer trying to keep up with the orders that were coming in for custom garments. That fall, I felt that there was enough demand for the two of us to do this together full-time. We officially started as a duo in January 2021, and from seeing Phil’s work, I already trusted that we’d be able to collaborate together well.

HOW DID THINGS CHANGE ONCE IT BECAME A PARTNERSHIP?

NW It took about three months for us to really merge our styles. Phil’s style is a lot cleaner, with a little more saturated color, and he also has a heavier hand. I have a brushier style, and use lighter shading. We started experimenting on pieces together while talking about how to make the style a little more cohesive—not to the point where you couldn’t tell who did what, but just so that it felt like one piece coming from two sets of hands.

PA I brought in an old t-shirt that I practiced a couple drawings on. Then we just jumped right into passing custom pieces back and forth across the table to one another. I think it’s nice because even if there are apparent differences in the style of one drawing to the next, there’s so much going on in any given piece that when you just step back and look at the whole composition, it feels cohesive.

DOES ONE OF YOU EXCEL MORE AT ILLUSTRATING CERTAIN KINDS OF IMAGERY?

NW We’ve been doing it together long enough now that we internally know who should do what. At this point, we both can do whatever comes our way. There are just certain things that one of us likes to do more than the other.

PA I think the big one that we joke about is that we get asked to do a lot of pet portraits. And I always tell Nick that’s on him. A lot of people want their dogs drawn on our jackets or pants.

SOMETHING I FIND INTERESTING ABOUT SMALL TALK IS THAT THERE’S A LOT OF DIVERSE IMAGERY USED, BUT IT ALL FEELS LIKE IT’S PART OF THE SAME CONSTELLATION.

HOW WOULD YOU DESCRIBE THE VISUALS THAT THE BRAND GRAVITATES TOWARDS?

PA It differs between the custom stuff and what we do for cutand-sew. It should be noted that for every custom piece we do that’s a one-of-one, we have a dialogue with each customer and we ask them to send us a stream-of-consciousness list of references and images that are meaningful or significant to them. That’s the jumping off point for researching and sourcing all the images for a garment. At this point, we’ve built up a library of images, so maybe 60-75% of the illustrations are unique to that person, and then there are old faithful images that we like to draw and know will work well. It almost turns into an “I Spy” composition or something—a bunch of disparate objects that don’t necessarily have anything to do with each other, but you put ‘em all together on an individual customer’s piece and the thread that connects them is that person’s interests.

NW We like to find some balance between imagery that comes from the natural world and commercial imagery. I think some of that has to do with our own lifestyles. Our studio is in Midtown near Times Square, so we’re constantly bombarded with all kinds of commercial and artificial graphics. It’s really fun to recontextualize that those visuals. Plus, both of us just love the outdoors in general. Phil’s a big surfer. I love to climb. We both like to hike, camp, swim in lakes and rivers—all that shit. I feel like the juxtapositions come from our city mouse, country mouse lifestyle.

87 ISSUE NO. 32

88

89 ISSUE NO. 31

ALSO REMEMBER YOU TELLING ME

ABOUT A BINDER FULL OF IMAGE REFERENCES AND EPHEMERA YOU’VE COLLECTED, ALMOST LIKE A TATTOO FLASH BOOK.

NW We have a few binders and a lot of that stuff has been scanned. Due to the pace of everything we’re making these days, a lot of our references come from digital sourcing, going back into the archive, and pulling stuff that fits. But then when we get a project like the one we just did with Karu Research and MR PORTER, where they gave us free reign to do whatever, we really dive into some weird shit. A lot of the imagery for that collaboration came from this old book called From India to the Planet Mars, which chronicles the life and work of this artist Hélène Smith. She held seances where she intended to communicate with a whole world of Martian beings and made automatic drawings in the process. I originally found the book on a public domain archive.

PA Similarly, when we did a capsule for Carhartt WIP last summer, we had a couple months to source imagery and we definitely got a lot of stuff from The Whole Earth Catalog. We also got a lot of references from our friend Kiyo, who has this massive, impressive collection of vintage outdoor gear called Monroe Garden. He has a permanent showroom in his apartment, and he showed us all these crazy old climbing and mountaineering catalogs from the ‘60s and ‘70s. We pulled a lot of images from those and incorporated them into those garments.

WHAT’S THE PROCESS LIKE WHEN DOING THE ILLUSTRATIONS FOR A CUSTOM PIECE? DO YOU HAVE AN IDEA OF WHAT THE FINISHED PRODUCT WILL LOOK LIKE FROM THE JUMP?

NW We never really plan out the design of an entire garment at once. We usually start with one big image that feels like a good anchoring piece and then work out from there. Luckily, we’ve never had a situation where we’ve started that organic process and gotten to a point where it doesn’t work.

PA I think another cool part of the whole process is the element of trust between the customer and us. With most garments, especially expensive garments, you know exactly what you’re getting. Here, though, there’s an element of surprise. People are sending us references, but it’s a very vague, amorphous list of things. They don’t know what we’re actually gonna draw on their garments, so it’s a big leap of faith. There’s always a surprise, but fortunately, all our customers seem to be pretty happy with the final product.

IT DOES REMIND ME OF TATTOO CULTURE IN THE SENSE THAT FLAWED OR IMPERFECT TATTOOS ARE ACTUALLY BETTER, IN A WAY. AN ARTIST’S INDIVIDUAL TOUCH SHOULD SHOW ITSELF.

PA Yeah, it almost looks better and is more meaningful when you can see a small element of the human hand and human flaw in a particular drawing. You can tell it’s not mass-produced. I think people appreciate and respond to that.

90

91 ISSUE NO. 32

AN YOU TALK ABOUT THE MATERIALS AND DESIGN APPROACH FOR THE CUT-AND-SEW COLLECTION?

NW It helps to be able to put together a full collection where there’s 20-30 pieces that all play off of each other, kind of like putting together a body of paintings or sculptures where one thing doesn’t have to fully represent the brand by itself. We find something to nerd out on and get really deep into it. This past spring collection, it was a book of tree carvings—arbor glyphs. We’d collected a bunch of images, which made me think about leaving your mark on nature—mark-making and mark-taking. That was combined with really trippy depictions of the natural world, like medieval horticultural manuscripts and these hand-drawn QSL radio calling cards that truckers used to make and distribute. The latter doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with the natural world, but the calling cards had wild images that resonated with us, and the way the images were made and shared had a lot in common with the tree carvings.

Those are turned into a very loose aesthetic guide for sourcing fabrics, coming up with images to embroider, and creating treatments, which, in turn, inform everything from drawings on garments to embroidered motifs—and even the fabrics and material. For example, there’s a pant in the spring collection that has a bark-like texture to it, a crinkled gauze fabric. And for the 2023 fall collection, we went for a psychedelic Western vibe with pieces like a fuzzy silk mohair jacket. It all emerges from the same place that our custom garments would, but it’s just translated in a different way. Plus, people like to see the hand-drawn stuff sideby-side with the cut and sew items and how they inform and play off one another.