6 minute read

Gartnavel Hospital Maggie’s Centre

Figure 12: Private patient room at Haraldsplass Hospital new main building (2018), Bergen, Norway, designed by C.F. Møller Architects

3.2 Case study two: Glasgow, Gartnavel Hospital: OMA

Advertisement

Maggie’s Centres are cancer centres where patients can recover from cancer treatment and also is also a place where their families and friends can meet and discuss the future. The foundation was founded by Maggie Keswick Jenks and her husband Charles Jenks. According to Edwin Heathcote, it is a space where cancer patients start to ‘help themselves … [and] take control of their own circumstances’ (Heathcote, 2006, p. 1304). To help patients achieve this state of mind Maggie’s Centres are designed with a strong consideration of nature through the use of biophilic experiences stated in chapter one. According to Charles Jenks (Jenks, 2017, p. 69) the connection to nature is vital because ‘when you are faced with cancer, a life-threatening disease based on rogue-life, you are likely to orient yourself to nature’. One Maggie’s Centre that achieves the biophilic experiences discussed in chapter one, is the

Gartnavel Hospital Maggie’s Centre [13, Fig. 13] located in Glasgow, Scotland (OMA, 2013). This building was designed by OMA with its completion in 2011 (OMA, 2013).

Figure 13: Gartnavel Hospital Maggie’s Centre (2011), Glasgow, Scotland, designed by OMA

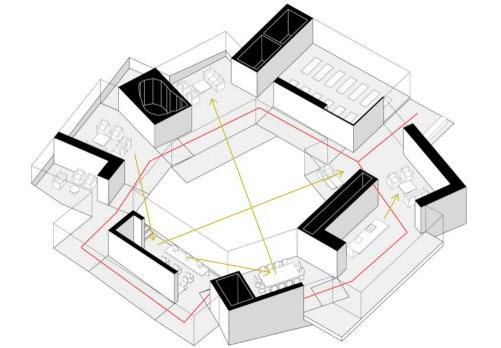

As seen in [14, Fig. 14], the Gartnavel Maggie’s Centre layout is in the shape of a ring. This centripedal design is intended to create a sense of unity within the space through the way patients and visitors interact with the built form and surrounding environment (Hollendonner, et al., 2012, p. 6). By using this layout at a small scale, the patients and visitors are able to walk in and out of rooms as they wish, whilst always being connected to nature. These open rooms are linked to other rooms not only by circulation but also by sight lines illustrated in [14, Fig. 14]. Prospect and refuge – a biophilic experienced noted in chapter one – is used here to create spaces that feel non-threatening.

Figure 14: Diagram illustrating circulation and line of sight at Gartnavel Hospital Maggie’s Centre (2011), Glasgow, Scotland, designed by OMA

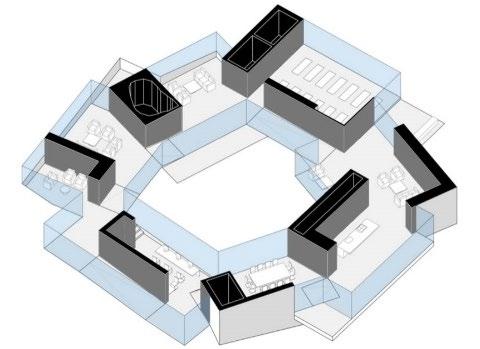

The external sides of the ring are clad in glass with the internal walls being solid structural walls as illustrated in [15, Fig. 15]. The glass windows provide high levels of prospect by offering clear linear lines of the surrounding environment, whilst the ridged structural walls provide refuge by delivering a sense of concealment and protection from the elements. The kitchen, seen in [16, Fig. 16], is the first room patients and visitors are led into when they first arrive at the centre. Here the occupants are protected by a semi-opaque wall [16, Fig. 16] which provides them with concealment from the large floor to ceiling windows providing the user with uninterrupted views of the outside world. By viewing the surrounding landscape through these large windows patients are able to put their mind to rest and focus on healing and getting better.

Figure 15: Diagram illustrating floor to ceiling windows and solid internal walls at Gartnavel Hospital Maggie’s Centre (2011), Glasgow, Scotland, designed by OMA

Figure 16: Kitchen at Gartnavel Hospital Maggie’s Centre (2011), Glasgow, Scotland, designed by OMA

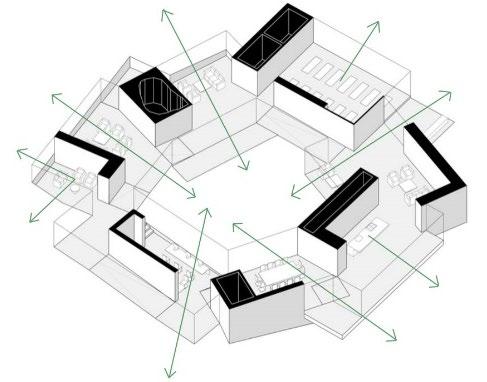

The same experience is found in the internal courtyard and the surrounding natural landscape. This connection is achieved through considered placement of large floor to ceiling glass windows and doors. As illustrated in [17, Fig. 17] one is able to view the internal courtyard and surrounding natural landscape from every room. These uninterrupted and circulating views of the surrounding natural landscape means the viewer is able to mentally relax. Through the use of reflective materials on structural walls the surrounding landscape encloses and comforts the viewer from all angles (as seen in [18, Fig. 18]), creating a sense of being enveloped and cradled by nature.

Figure 17: Diagram illustrating visual connection to surrounding landscape at Gartnavel Hospital Maggie’s Centre (2011), Glasgow, Scotland, designed by OMA

Figure 18: Meeting space at Gartnavel Hospital Maggie’s Centre (2011), Glasgow, Scotland, designed by OMA

There is only one room within this design that does not have glass walls. This is one of the small counselling rooms available as seen in [19, Fig. 19]. It provides a relaxing and comfortable space that promotes confidentiality and privacy through the use of many biophilic experiences. The user is enclosed in a continuous organic wall. The soft natural shapes reduce mental stress as there is no uncertainty within the space – no sharp edges or places of unknown creating a cave-like experience. Through the oculus, the users are provided with an abstract view of the ever-moving and always changing sky through fallen autumn leaves on the roof. The oculus allows for warm rays of sunshine to fall onto the users below warming their skin as they discuss the future. As mentioned in chapter one, natural light is important in the process of mental healing as it enhances morale and improves mood.

The organic undulating walls are clad in timber strips that have been moulded to the curving surface. The pattern created by the horizontal repetition of the thin strips of wood mimics the natural grain of the timber, causing the viewers to shift their attention to the details on the wall. These details allow the patients eyes to wander as they reflect and think, and as suggested by Salingaros (2015, p. 28), these details provide order within the space that reduced mental stress.

Figure 19: Small counselling room at Gartnavel Hospital Maggie’s Centre (2011), Glasgow, Scotland, designed by OMA

Conclusion

This third chapter has explored in depth the biophilic experience described in chapter one within two existing buildings - the Haraldsplass Hospital new main building designed by C.F. Møller Architects and

the Gartnavel Hospital Maggie’s Centre designed by OMA. Through this analysis, it is evident that by considering biophilic experience within design a successful space can be created that benefits the users' psychological state of mind, as well as their physical wellbeing.

All biophilic approaches demonstrated in chapter three could be scaled up and used in the design of larger hospitals in the future. Both these examples, the Haraldsplass Hospital new main building and the Gartnavel Hospital Maggie’s Centre, are situated within the natural landscape, however as cities expand natural light and views become harder to obtain. Therefore, the biophilic experiences mentioned in chapter one must be applied in a different manner. For example, a hospital that is surrounded by buildings can boast a vibrant and lush internal courtyard for patients to sit and relax within. All patient rooms that surround the internal courtyard could have views of the lush green canopy that is brought into the space through the considered use of natural materials. The courtyard and patient rooms could have access to the natural light streaming through the open ceiling of the courtyard that also draws fresh air into the centre of the hospital. Smaller, enclosed spaces can provide a sense of comfort through the considered geometry of the space, ornamentation and natural materials. Hospitals that wish to provide a space within the natural environment might wish to adopt the use of healing centres that can be located away from the hustle and bustle of the city, just like the Maggie’s Centres. As is demonstrated in chapter three there is a need for architects to think beyond the simple solutions stated in chapter one to achieve biophilic design that beneficially impacts the patients psychological state of mind.