12 minute read

Chapter Two: Hospital typology and its influences

Chapter Two

Hospital typology and its influences

Advertisement

Introduction

Within the architectural landscape, the typology of hospitals has changed dramatically over the years (Verderber et al., 2000; Kisacky, 2005, 2013, 2019; Adams, 2008; Burpee, 2008; Tesler, 2018). Typically, these changes to the typology have been scientific and government-led. Contemporarily, the influence of architectural thinking has seen a rise of human-centred design. Architects are starting to design for greater and more diverse human needs beyond the physical, thus creating spaces that reduce mental stress. This chapter explores these influences that led to hospital design changes throughout American history. The influences discussed within the chapter originated in America and these ideas have been internationally adopted. Photographs of historical and modern hospitals are used throughout this chapter to illustrate the ideas explained. Throughout this chapter, it is evident there is a rise and fall of biophilia within architecture. As biophilic spaces beneficially impact the users’ mental state it is important that architects critically engage with, and challenge, the current way of think and lead a strong movement into human-led design.

2.1 Scientific influences

As early as the third millennium BC (Tesler, 2018, p. 1), religious orders looked after the infirmed in hospitals, while the sick were looked after in their homes (Kisacky, 2017) and this was the case until the nineteenth century (Tesler, 2018, p. 3). According to Nancy Tomes (1998) in the late 1700s, the transmission of disease was due to bad air ventilation – Miasma Theory. It was thought that by creating a clean and pure environment within the wards the mortality rate of patients would improve (Burpee, 2008, p. 1; Kisacky, 2013, p. 84). As a result, hospitals were designed around the patient, natural light and the most important factor maximising the fresh air flow through the building to reduce miasma –bad air that carried airborne disease (Kisacky, 2013, p. 86). In the early 1870s views on disease prevention were based on the worry of airborne diseases floating on dust – Germ Theory (Kisacky, 2013, p. 86). These views resulted in hygienic design (Burpee, 2008, p. 1) – a space that is easily disinfected (Kisacky, 2013, p. 90).

Florence Nightingale (1820 – 1910), American founder of modern nursing (Burpee, 2008, p. 1), developed the pavilion hospital design that was centred around the masima and germ theories (Nightingale, 1863). The pavilion plan consisted of a centralised corridor with the wards (pavilions) running perpendicular to the corridor (Burpee, 2008, p. 1). Each pavilion housed 30 to 40 patients in one large single room (Adams, 2008, p.10) and became its own small hospital.

In Nightingale's book, Notes on Hospitals (1863), she meticulously details what needs to be done by architects and designers to achieve a hygienic hospital. Such headings seen within her book are; the type and care of linen, the number of beds to a single-window and water supply. According to Nightingale (1863, p. 67), ‘one window at least should be allotted for every two beds; the window to be not less than 4 feet 8 inches (1.42 meters) wide, the sill within 2 feet (61 centimetres) or three feet (91 centimetres) off the floor, so that the patient can see out, and up to within a foot (30 centimetres) off the ceiling’. She further details the position of windows in the ward to be opposite each other, the material and colour the window frame should be and the particular glass that should be specified (Nightingale, 1863, p. 67). High ceilings were preferred as it facilitated an increase in airflow (Nightingale, 1863, p. 152)

Nightingale (1863, p. 68) also mentions that diseased airborne organisms could cling to surfaces. According to her, the walls and ceiling should be covered in a durable white material that can withstand being polished and frequently washed with water and soap (Nightingale, 1863, p. 68). The woodwork must be ‘polished or varnished wainscot oak’, as it is durable and uniform in colour (Nightingale, 1863, p. 68). As wood is a porous material polish or varnish was to be used to eliminate the absorption of germs. Polish and varnish also meant a surface was able to be easily cleaned (Nightingale, 1863, p. 68). Wood was also used for the floors; oak wood or pine wood was preferred; however, tiles were also acceptable (Nightingale, 1863, p. 69). Light colours were selected for all materials as it meant they ‘looked clean’ (Kisacky, 2013, p. 85). The furniture used within the wards were specified as oak furniture (Nightingale, 1863, p. 79). All finishes needed to be plain, joints seamless, details smooth and corners rounded to create a space that can be easily cleaned and disinfected. It was clear to John Maynard Woodworth, the first American general surgeon, that the wards ‘should be free from all unnecessary angles and ornamentation upon which dust would be liable to lodge’ (Kisacky, 2013, p. 85)

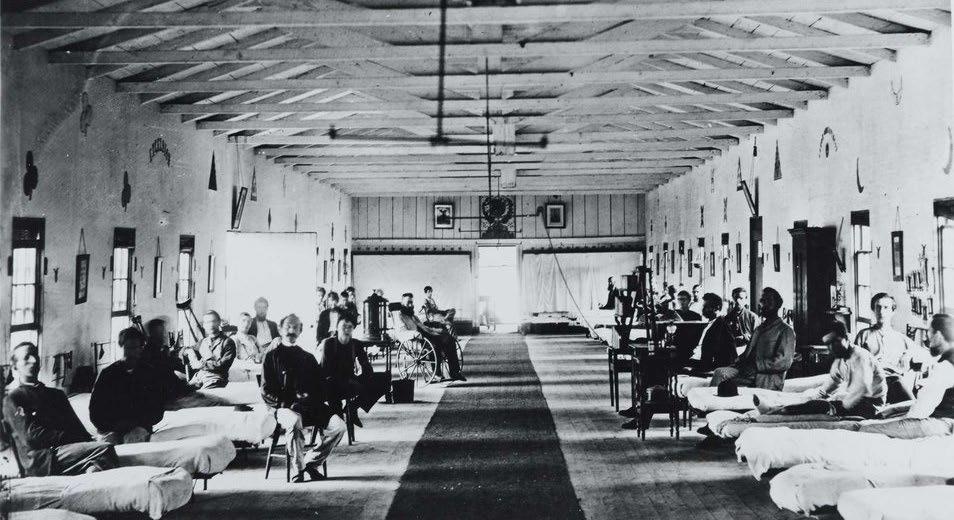

These architectural qualities have been illustrated in [5, Fig. 5]. It is evident there is a strong link to biophilic experience mentioned in chapter one. Although these experiences have been used for other reasons, for example hygienic design, they still provided biophilic benefits that might not have been understood at the time, such as the inclusion of natural materials, a view to the landscape and natural air flow and light.

Figure 5: Interior of Ward K of Armory Square Hospital, Washington, DC in 1865

2.2 Political influences

Nightingale’s pavilion hospital plan became internationally adopted by the late nineteenth century (Kisacky, 2019, p. 9), however the growth of medical knowledge and the introduction of new medical technologies meant that the pavilion plan no longer suited the needs of staff and patients (Kisacky, 2013, p. 86). Medical care moved from the home and into hospitals, which catered for all who needed medical attention as a way to bring medical attention to all. Hospitals became a place where people were sent to get better and live, in contrast to the historical practice where they were considered a place where people were sent to die (Kisacky, 2019, p. 288). The poor were placed in large wards whereas the wealthy were placed in private rooms (Kisacky, 2019, p. 290).

At the beginning of the twentieth century the introduction of new technology and medical care lead to pavilions becoming dependent on each other (Kisacky, 2013, p. 86). This communication between pavilions was difficult as it compromised the isolation of disease (Kisacky, 2013, p. 86). Thus, it was thought that high-rise hospitals would be a perfect balance of communication between the pavilions whilst still isolating patients (Kisacky, 2013, p. 87). This shift in design was called aseptic design. According to Jeanne Kisacky (2013, p. 90), aseptic design ‘added the need to control the movement and interaction of goods, people and air. Aseptic materials and details facilitated decontamination; proper placement of walls, barriers and decontamination fixtures prevented germs migrating from the infected areas of the hospitals to the clean’.

Aseptic design meant that all details and joins must be seamless and flush (Kisacky, 2013, p. 90). This meant that there was no ornamentation - walls had to meet flush to the floor and ceiling and door and window trims had to be placed into the walls (Kisacky, 2013, p. 90). Aseptic materials consisted of plaster walls covered in a hard-white enamel paint and a flooring material that was non porous, would

not crack, consistent in colour, easily cleaned and most importantly ‘germ proof’ (Kisacky, 2013, p. 90). Glass was considered the ‘king of aseptic materials’ as it was seamless, resilient and allowed light in that made the dirt immediately visible ( Kisacky, 2013, p. 90). Furnishings were to be plain and made of iron (Kisacky, 2013, p. 90) as they could be easily wiped down.

After World War II there was an increase in hospital construction as there were many communities without access to medical services (Kisacky, 2017, p. 1). The urgent need for hospitals meant that there was little time to rethink the hospital layout. The Hill Bruton Act was introduced to set a standardisation of hospitals across America. This act meant that hospitals had to be designed according to the pre-war designs. If an architect or client desired a more innovative design the government would not fund it. Accordingly, many out of date hospitals were built (Kisacky, 2017, p. 4).

Scientific influences impacted political views of the time, thus both influences became intertwined. The introduction of antibiotics meant that patients were no longer dying from infections (Kisacky, 2017, p.1). This led to design choices that artificially provided comfort and a controlled environment, such as the introduction of air conditioning, small windows that could not be opened and ultraviolet lighting (Kisacky, 2017, p. 3). According to Kisacky (2017, p. 3), the introduction of antibiotics ‘provided an effective treatment rather than an effective prevention’.

These types of hospitals were known as deep plan hospitals. This design moved away from the patients' health and comfort and focused on efficiency (Burpee, 2008, p. 2). These buildings have become larger and taller over time, which limits access to natural views, air, and light. According to Heather Burpee (2008, p. 2), architects ‘are still building hospitals with very deep floor plates and subterranean spaces with little or no relationship to the outside environment’. These hospital designs have become internationally employed.

Ward 8A and 8B of the Mater Hospital in Brisbane [6, Fig. 6], designed by Formula Interiors, is a dementia ward that has been designed with the focus on bettering infection control and improving the wellbeing of the nursing staff (Formula Interiors, 2018). As seen in [6, Fig. 6] there is a lack of all biophilic experiences mentioned in chapter one. One biophilic experience that is known to benefit patients’ with dementia is the use of natural light within the space as it helps them to remember the time of day (Linebaugh, 2013, p. 16). Views of natural scenery also helps patients’ with dementia to remember the time of year (Rappe and Lindén, 2004, p. 80). By incorporating these two biophilic elements within a space, the patient is mentally relaxed as they are able to gain some control over their own memory. As illustrated in [6, Fig. 6] there are two small windows located at one end of a long room that caters to four patients. This design is also very different from what Nightingale (1863, p. 67) stated within her book where each patient must have access to a window that provides natural light and views.

Figure 6: Ward 8A and 8B of the Mater Hospital in Brisbane, designed by Formula Interiors

2.3 Human-centred design

It is the architect’s responsibility to design spaces that are beneficial to the user (Ellis, 1986; Wasserman, Sullivan and Palermo, 2000; Di Cintio, 2014; Cuff and Murry, 2017), thus the architects’ role is to design spaces that give consideration to human ethics. According to Barry Wasserman, et al. (2000, p. 17), architecture and ethics are linked as it is ‘the processes of designing and constructing our habitat, with the presumed intention of improving the quality of life, implicitly require a judgment of the “right” thing to do’. In this role, architects have taken on the ethical responsibility to serve all members of the community (Wasserman, Sullivan and Palermo, 2000, p. 78). Thus, it is important for architects to become activists and demonstrate the path that needs to be followed in order to created stress-reducing environments but responding to emerging research concerning the benefits of biophilia, within the hospital typology (Di Cintio, 2014, p. 2).

As evident within [6, Fig 6] architecture has moved away from benefiting the users' mental state of mind. To return to human- centred design that benefits every aspect of human wellbeing, a change must occur. According to many (Di Cintio, 2014; Salingaros, 2015; Cuff and Murry, 2017), this change must start with the institutions that are teaching our future architects. It is important that these institutions provide new ways to practice and learn. Students have been taught how to satisfy the clients' needs, for example through designs that generate cash flow and further the client’s agenda. Whilst it is important to consider the client’s needs, it is also vitally important to consider the users' needs as well. According to Salingaros (2015, p. 14), by ‘bringing … living qualities back into architecture’s toolbox, we can

better incorporate healing strategies’ within future designs. According to Dana Cuff(2017), architecture students must ‘take the opportunity to act with conviction ... toward creating the world we want to live in. Students are the architects of the future; thus, they must have an understanding of the current world issues that need design solutions. As mentioned by Cuff (2017), students must design to the needs of the user, thus providing better quality of life, ‘that’s exactly what it means to … act like an architect’ . Students' learning needs to adapt to current issues to achieve a positive change to produce ethical architecture (Di Cintio, 2014, p. 2).

Biophilic experiences within designs have been filtered out of hospital design for many reasons as discussed previously in this chapter. However, one main reason that hospitals today lack these biophilic experiences, is due to the emotional distance the architect holds to the project. One way architects are hindering this connection to the environment being created is the use of computer-aided design software (Salingaros, 2015, p. 14). According to Salingaros (2015, p. 14), such software ‘have sidelined the traditional roles of immediate feeling and mutually adaptive response in generating architecture’.

As hospitals require high sanitary levels, which may be affected by biophilic experiences, architects have resorted to designing healing care centres which encompass biophilic design. These healing care centres have been designed separately to the main buildings of the hospital. This allows architects to design biophilic environments without sanitary constraints. The Maggie’s Centres are an example of such biophilic architecture and will be further analysed within chapter three. Although these centres are affiliated with a hospital their design is very different to traditional hospital facilities so as to include the mental healing process of patients.

Conclusion

This chapter has analysed the ideas that have influenced hospital design within America since the eighteenth Century – scientific influences, political influences, and human influences. From this chapter it is evident that modern hospitals have been designed for doctors instead of patients. According to Annmarie Adams (2008, p. xx) , ‘doctors played an active role in the development of twentieth-century architecture’. Thus, these influences have tendered to change hospital typology towards the needs of health care professionals and away from patients. Contemporary recognition of the adverse conditions this creates for patients’ has reinforced the importance of biophilic experiences which are now

beginning to be implemented within hospital design. Some major architectural firms that focus on designing biophilic environments are C.F. Møller Architects, Hassell, Herzog & de Meuron, Hopkins Architects, OMA and nbbj. Glasgow, Gartnavel Hospital Maggie’s Centre designed by OMA and the Haraldsplass Hospital new main building designed by C.F. Møller Architects will be further explored in chapter three.