12 minute read

Chapter Two: The Humanistic influence of Asplund and Aalto

Chapter 2: The Humanistic influence of Asplund and Aalto

This chapter will look at key works from architects Gunnar Asplund and Alvar Aalto. Catalysts in the modernist movement throughout Scandinavia, their works demonstrate the interior architecture qualities and techniques that cater to the human experience of an individual and apply them to the masses within their public architecture. It is vital to acknowledge how the architectural style of modernism was a tool used by architects such as Asplund and Aalto to improve the everyday lives of as many people as they could through rationality and a scientific approach to human behaviour (Levine 2018: 13). However, the efforts of Asplund and Aalto went beyond the universal requirements associated with functionalism. Asplund and Aalto acted as architects focusing on the notions of place, memory and experience within modernism (Miller 1990: 12). Shortly after the Stockholm Exhibition in 1930, Asplund together with Paulsson, Markelius and Åhrén released their manifesto titled Acceptera – Swedish for accept – pushing their egalitarian agenda and pleading with the public to embrace this new architectural style and bring it into their homes. Acceptera focused on social transformation through the idea of home and transforming the standard of living for the public (Levine 2018). It was the Stockholm Exhibition which launched this connection between architecture and ideology, as functionalism was propelled into the mainstream. The political initiative of Folkhemmet attached itself to the style, using it as a technique to solve the welfare issue of housing (Levine 2018: 13).

Advertisement

Before the Stockholm Exhibition, Gunnar Asplund was a central figure in the Nordic Neo-Classical architectural style which dominated Scandinavian Architecture between 1910 and 1930 (Blundell Jones 2002: 41). This distinctive period can be seen as bridging between the ornate classicism of the 19th century and the functionalist modernism which dominated from the mid 20th century onwards. The façade of Asplund's 1918 Snellman House in Djursholm, Stockholm (Figure 2.01) provides evidence of his new interest in simplicity and restraint with the precise disposition of fenestration. Especially when viewed in conjunction with Asplund's Villa Callin (Figure 2.02) completed only three years prior in 1915, featuring a much more ornate traditional façade. The façades indicate the first change as Asplund moves towards modernism, this chapter will analyse the effects of this change on the interiors of Asplund's Stockholm Public Library, completed in 1928.

Figure 2.01: Gunnar Asplund, Snellman House 1918, Sweden, illustrating Asplund’s departure from the ornate classical facades of his earlier neo-classical style

Figure 2.02: Gunnar Asplund, Villa Callin 1915, Sweden showcasing the traditional style through the embellished façade and curved lines

The political and social climate addressed in the first chapter, provide the necessary foundation to understand how interior devices were developed and used to galvanise the social aims of Asplund in his desire to construct an egalitarian Sweden. Analysing the public library gives shape to the process Asplund undertook as he transitioned from Neo-Classical architecture toward more humanistic modernism. Asplund saw the role of public buildings as having an immense obligation to celebrate their communities and perform its purpose successfully (Blundell Jones 2002: 125). Due to its programme, the library presented a remarkable opportunity to give the people of Stockholm a worthy public building Offering for the first time to the general public the chance to take books off the shelves and borrow them, providing education to the modernising Swede. Due to public involvement in the process of lending the space needed to be designed in a way as not to alienate those who had never taken part in such an activity (Bergström 2009).

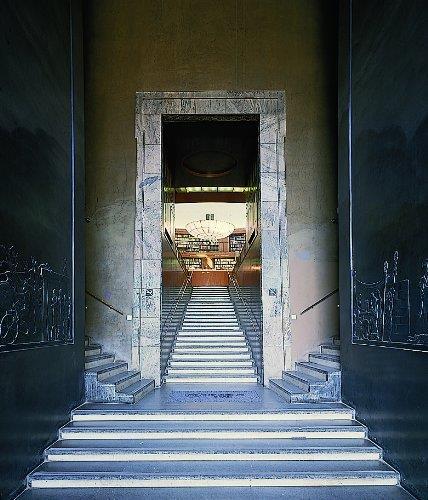

Scale and the organisation of space will be addressed first, followed by the use of light and its reaction with materiality. The principal notion for the spatial arrangement was that upon entry through the grand ascending staircase (figure 2.03) the library would open up into a vast circular lending hall with books stacked in three tiers around the periphery (figure 2.04), the tiers ensuring ease of retrieval without a ladder. In the centre of the hall was a control point for librarians which gave them total visual authority, inspired by principles from Jeremy Bentham's 18th-century Panopticon (Blundell Jones 2002: 113). In figures 2.05 and 2.06 depicting the ground and first floor plans the central hall is seen encased by the side wings which housed quiet reading rooms, the children's library, storage, and the librarian's offices. In order to check out a book, visitors would need to ascend a central flight of stairs to reach the control point. The axial staircase bisectedevery level, grand architectural staircases such as this, would become synonymous with Asplund's style in the years to follow (Blundell Jones 2002). Asplund developed a spatial narrative using counterpoint; the axial entry ascends away from the main entry stair through a tall, exciting shaft of space which gently curves around the central drum (Wilson 1988: 90). The linear direction works in unity with the circular form, passing through vestibules and a series of thresholds before finally arriving at the magnificent beauty of the central drum once again "signifying initiation into a new world of knowledge" (Blundell Jones 2002: 113). The same focus on central stairwells and maximisation of natural light is evident in Asplund's later regeneration of the Gothenburg Law Courts seen in figure 2.07 illustrating the central connection point from the ground floor and figure 2.08 which shows an overall shot of the foyer.

Figure 2.03: Gunnar Asplund, 1928, grand entry staircase to the Stockholm public library opening up to the vast circular interior façade

Figure 2.04: Gunnar Asplund, 1928, interior lending hall of Stockholm public library, displaying books on tiered levels and dappled plaster texture reflecting natural light to create a sense of the ceiling as sky (Adams 2014: 112)

Figure 2.07: Gunnar Asplund Gothenburg Law Courts central staircase depicting the Asplund’s signature central staircase and propensity for clean sleek lines

Figure 2.08: Gunnar Asplund Gothenburg Law Courts supplementary staircase and view of the foyer showcasing the developments of Asplund’s modernist style and utilisation of natural light

A key proponent of the functionalist movement was the use of natural light and the way it yielded a sense of spatiality. Based on studies done on the conditions of daylight in varying building conditions, there was a scientific methodology applied to the shaping and positioning of windows to let light in (Levine 2018: 14). Asplund's consideration of the temperamental Swedish sky and understanding of Nordic light qualities saw him opt for a flat cylindrical drum ceiling (seen in figure 2.04), in favour of the initially proposed glazed dome (Schwartz 2015: 1). The white plaster clad walls of the drum provided significantly more surface to diffuse the light which was better suited to the low angle sun. The vertical arrangement of the windows on the exterior cylinder walls allowed for direct bright light to enter the library, yet the verticality of the windows ensured they were far enough away as not to affect the books and patrons with direct sunlight (Schwartz 2015: 1). The cylindrical form created a complete lack of shadows on the ceiling, combined with the mottled texture of the plaster gave the effect of infinite space above the library. The vast white space diffused light below and the ridges in the plaster give the effect of little clouds. Architectural author Nicole Adams invokes the notion of the "ceiling-as-sky" (2014: 112). The library is an internationally renowned symbol of Swedish neoclassical and modernist beauty which combines environmental sensibility with the instruments of Asplund's classical technique, demonstrating the progression of Asplund's style into the modernist era.

The relationship between Asplund and Aalto progressed form friend, to mentor to a colleague as they both adopted their versions of functionalism, developing a comparable examination into a sophisticated modern vernacular (Ray 2005: 18). Asplund embraced modernist principles with great tenacity, choosing to apply a layer of environmental specificity and human predisposition to his spaces. Similarly, Aalto implemented a specific response to the landscape and a deep humanistic sensitivity, in opposition to the dogma of functionalism. Aalto's 1948 Sänynätsalo Town Hall in Finland was constructed with the topography it was to sit upon at the forefront of the design. The result, a refined and tasteful gathering place for the small town of 3000, constructed from conventional local materials. Aalto was able to embody the community and celebrate its values and ideas (Nerdinger 1999:15). The building consists of civic functions such as council offices, meeting rooms and a council chamber as well as public functions such as the library, sauna, boiler room and a central raised courtyard. The grass clad courtyard pictured in Figure 2.07 makes use of the sloped topography sitting a full story-higher than street level with a slightly rotated axis relative to true north to achieve optimal sun orientation (Ray 1999:107). Surrounding the courtyard is the library, reading rooms and administration laid out to form

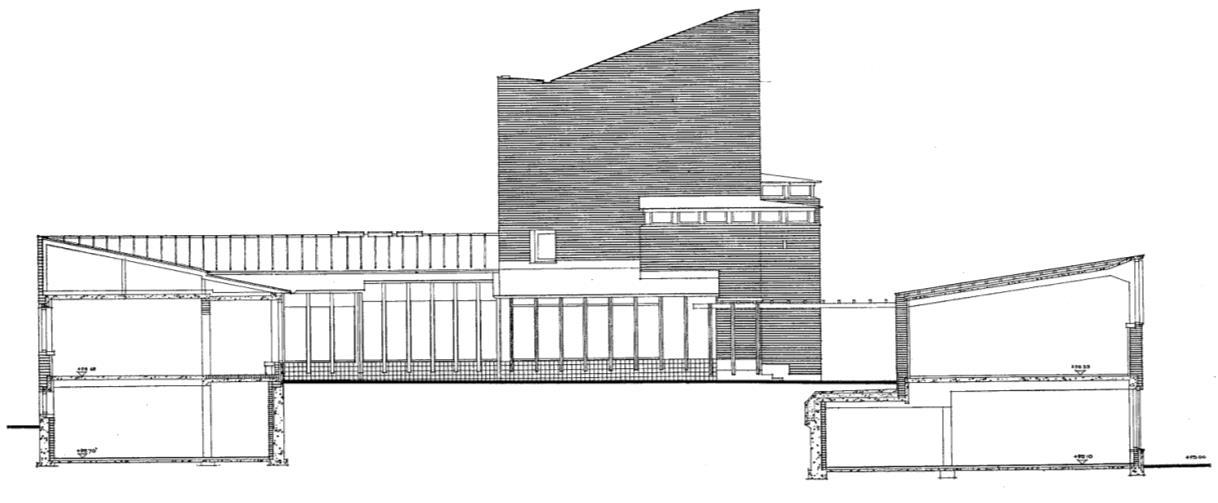

a hub of cultural activity for the citizens whom host social events and partake in leisure activities establishing the heart of the town hall (Nerdinger 1999:25). Figure 2.08 illustrates a North-South section through the offices, store and raised courtyard. The imposing mass of the council chamber is seen in elevation. The projected stair wrapping around the chamber is an ode to the wrapped staircase Asplund used in the Public Library, which Aalto saw under construction while on a visit to Sweden in 1926 (Ray 1999). The council chamber is raised one story above the courtyard and other spaces, literally elevating the function of the space, signifying the salience of the symbol of government. Further exaggerated through the inwardly sloping low pitched roofs throughout the rest of the building (seen in figure 2.07), sloping towards the council chamber, respecting its importance while ensuring maximum penetration of shallow-angled sunlight (Ray 1999:108).

Figure 2.07: Alvar Aalto 1948 Sänynätsalo Town Hall, Finland, showcasing the glass clad central courtyard and pool, the greenery is juxtaposed against the deep red of the brick

Figure 2.08: North south section of Alvar Aalto’s Sänynätsalo Town Hall cutting through the officer, courtyard, and store; showcasing the scale of the council chambers and the inward slope of rooms in the direction of the council chambers signifying the salience of the chambers

The spatial qualities of the hall are considered down to the minutia as part of Aalto's detail-oriented design approach. Examples of this include the custom-designed stair balustrades, and the brickwork laid purposefully misaligned to subvert mechanical perfectness in favour of a more natural-looking surface (Nerdinger 1999:26). Aalto undertook an iterative process of refining the interior details to determine the most suitable sequence of spaces, as well as designing furniture following the forms and curves of nature. All things he understood as separate from the architecture, "but rather as an act of protecting the people who would spend their time in them" (Nerdinger 1999: 26). The complex implementation of natural light, sunlight and ventilation was considered by Aalto and supplemented with specially designed light fittings and window placement. Evident in the Council Chambers whereby the primary source of natural light is the large north-facing gridded and timber-louvred window pictured in figure 2.10 supplemented by the clerestory windows (figure 2.11) and skylights in the public gallery (seen in figure 2.10) (Hawkes 2001:79). Artificial lighting designed by Aalto is utilised with restraint, installed on the ceiling. Eight ceiling lamps arranged to ascend towards the chairman's seat, reinforce the direction of the gaze and compliment the slope of the roof (Hawkes 2001:79). The dark brickwork casing every wall surface absorbs almost all light and renders the room mysteriously dim, an unusual decision for a symbol of government. Pallasmaa writes in Hawkes, (2008:80) "the dark womb of the council chamber recreates a mystical and mythological sense of community; darkness strengthens the power of the spoken word". In contrast with the brilliant radiance omnipresent throughout the rest of the building, e.g. the interior passageway (figure 2.12) and public meeting room (figure 2.13), there is

a deliberate lack of external nature in the council chambers subsequently emphasising the execution of local democracy (Hawkes 2001:80).

Figure: 2.09: council chambers in Alvar Aalto’s Sänynätsalo Town Hall highlighting the large north facing window and skylights in public gallery as the two major natural light sources

Figure: 2.10: thoroughfare in Alvar Aalto’s Sänynätsalo Town Hall, the light filled hallway is a stark contrast to the dark ambience of the council chamber

Figure: 2.11: meeting room in Alvar Aalto’s Sänynätsalo Town Hall, the large windows flood the room with natural light and provide a connection between the outdoors and indoors, drawing nature in, emphasised by the earthy hue of materials

Aalto’s elaborate surface details, considered layouts and intrinsic links to nature craft spaces which are grounded in a sensory realism imbuing intimacy and warmth to reconcile the needs of the people with the buildings he erects. The version of modernism spearheaded by Aalto and Asplund balanced functionalism tenets with regional traditions in an attempt to bring modern concepts into a local context. When propelling functionalism throughout Sweden, Asplund championed a focus on universal technique by using regional norms of expression and craft, which worked to solve the housing crisis and transport Scandinavia into the realm of modernity (Miller 1990: 4). Subverting of the "form follows function" dogma synonymous with functionalism, Aalto focused on reasserting the critical principal of place, both physically and culturally. Employing a sensitive version of modernism which was tailored more to the inhabitants of the space and responded to the land on which it sat (Miller 1990). Author Winfred Nerdinger says about Aalto "The humane quality of Aalto's Modernism lies in the fact that the fulfilment of human functions is not subject to formal, economic or construction constraints" (1999:15).