9 minute read

Chapter Three: Contemporary applications of Folkhemmet

Chapter 3: Contemporary Applications of Folkhemmet

Chapter 3 will outline the influence of Asplund and Aalto on contemporary public spaces in Scandinavian interior architecture, beginning by tracing the journey of Folkhemmet to the co-living movement in the early 1930s spearheaded by Sven Markelius (Vestbro 2008). Followed by how the democratic ideology of home impacted the design of two contemporary case studies. Sweden is built upon a socio-political foundation concerned with the wellbeing of its people and an understanding of the importance of adequate housing for everyone. Widespread improved living circumstances for all members of the public resulted in a distinct lack of social class disputes creating a favourable climate for the perpetuation of Folkhemmet (Czarny 2018: 199). As a proponent of the Folkhemmet movement functionalist architect Sven Markelius wanted to construct housing that could affect people's way of life and create more fulfilled citizens (Vestbro 2008). Markelius' 1935 co-living apartment block, John Ericsonsgatan 6, was the first modernist co-living space, whose effects can be seen in co-living spaces today. Following his involvement in the Stockholm exhibition, Sven Markelius went on to apply functionalist principles to his social housing projects (Lindvall 1992:73). Concerned with rationally organising society, and maximising productivity Markelius erected the first modernist collective house in 1935, a mode of living based on the Swedish model of Kollectivhus – housing with common spaces and shared facilities (Vestbro, 2010) – together with social scientist Alva Myrdal (Vestbro 2008). In the book Acceptera, it was forecasted that the future of housing would see, large percentages of household duties organised collectively. As stated by Myrdal in the 1932 magazine Tiden,

Advertisement

"Urban housing, where twenty families each in their own apartment cook their own meatballs, where a lot of young children are shut in, each in his or her own little room – doesn't this cry for an overall planning, for a collective solution?"

The utopian vision of Markelius and Myrdal saw residents of the collective house improving their mental and physical health with increased socialisation and participation in sports, study circles and political meetings. The size of private apartments would be minimised in favour of larger common and outdoor areas (Vestbro 2008). A further catalyst for the collective house was to divide and simplify housekeeping, freeing women from the duties of home, allowing them to contribute to the business and public sectors (Blomberg & Kärnekull 2019).

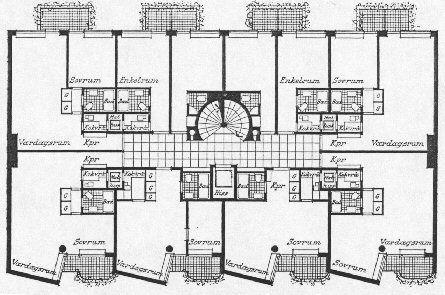

John Ericsonsgatan 6, Stockholm contains 57 apartments ranging from one bedroom to four all equipped with a kitchenette to prepare smaller meals. The larger, central kitchen located at the heart of the building on the ground floor. Figure 3.01 depicts the ground floor, the communal kitchen, dining areas, living spaces, daycare, laundry and milk bar. Figure 3.02 shows the first floor, a mixture of studio and one-bedroom apartments. Markelius himself lived at John Ericsonsgatan 6 for several years after its completion, fine-tuning the services and layouts which would go on to inspire other architects, developers and government officials to build another fifteen collective houses in Sweden from 1935 to 1956 (Blomberg & Kärnekull 2019). Further iterations of the collective home were conceived throughout the country over the decades, with some focusing on the utilisation of paid services such as cooking and cleaning, and others adopting a more collaborative division of labour between residents (Vestbro 2008). Today, the common thread amongst collective houses is the sense of community and network of support these types of living situations can offer tenants who want to "take responsibility for their lives in cooperation with their neighbours, based on mutual support, self-governance and active participation" (Blomberg & Kärnekull). Contemporary Examples of co-living are K9, Stockholm and the cohousing project in Uppsala Rudbeckia opening in 2022 both creating affordability through shared economies.

Figure 3.01: Ground floorplan of Sven Markelius’ Figure 3.02: first floorplan of Sven Markelius’ 1935 co 1935 co housing unit, the communal kitchen, dining, housing unit, configuration of 1 bedroom and studio lounge and cleaning facilities apartments with kitchenette and small bathroom

The adapted version of modernism that Asplund and Aalto developed together towards the end of the 1930s saw the functionalist, principles of modernity realised following a deep-seated Scandinavian affinity for social values and a time-honoured practise of craftsmanship. This afforded their projects a humanistic sensitivity and attention to detail that was previously lacking from some modern interiors (Carter 1993:54). Bjarke Ingels' Stockholm architecture studio BIG completed 79&Park, a modular set of 140 apartments located on the edge of Gärdet national park in Stockholm in 2018. Arranged around a central communal courtyard the scheme is constructed of square prefabricated modules, clad in cedar arranged in a stepped design reaching 35 meters at the highest point (BIG Studio). Constructed to blend with the surrounding landscape seamlessly, the local materials and overall geometry of the residential housing block appears like a human-made verdant hillside (Dezeen 2018). They created interiors of peace and tranquillity with a strong sense of community (Dezeen 2018). The importance of community is emphasised as each apartment has a wood and glass panelled roof terrace, creating lines of sight between apartments and interaction amongst neighbours (Figure 3.03). Strategically the orientation of the windows affords internal privacy. Furthermore, the porosity of the structure activates the shared courtyard as three public passageways bisect the building (Figure 3.04). The courtyard is the social core of the community; all the terraces contain windows facing on to it, creating visual connection and inclusion. Figure 3.05 depicts the ground floor plan, showing the commercial spaces opening onto the courtyard, and the public passageways, creating an ideal setting for a dynamic community hub. The first floor in figure 3.06 shows the arrangement of the residential units situated to maximise sunlight exposure and views of the park.

Figure 3.03: Arial shot of BIG’s 79&Park, 2018, exhibiting the sloped geometry of the building and roof terraces

Figure 3.04: Ground floor plan of BIG’s 79&Park, 2018 highlighting the public passageways intersecting the communal courtyard

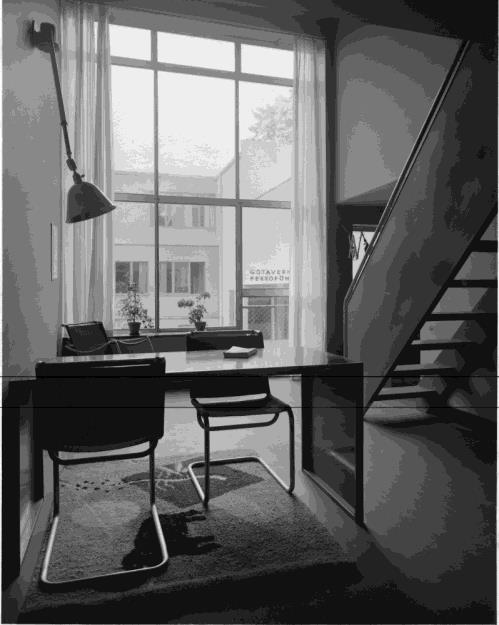

The interior materials palette utilises a mixture of concrete, local wood and glass, working in unity with the composition, form, proportion and light. The internal experience of the apartments is tranquil and spacious; examples of this is seen in figures 3.05 and 3.06. The installation of floor to ceiling windows, use of transparency and porosity throughout the building ensures natural sunlight to be drawn deep into each space, exposing residents to available light and heat — a technique utilised by Markelius at the Stockholm Exhibition. In fact, his model apartment strikes a remarkable resemblance to the interior of 79&Park (Figure 3.07 & 3.08). However, in this contemporary context, the kitchen has been moved from the back of the apartment to the front — a sign of the evolution of gender roles and female liberation (Vestbro 2008). The use of natural light modulates the rooms through shadow extending the language of modernism and imbuing it with considerations of place and history. 79&Park houses Aalto's practical concerns of sensitively responding to the local site, providing tailored spatial arrangements, and utilising natural textured materials in combination with dappled ambient daylight (Tyrrell 2018). 79&Park responds expertly to its topography, creating a seamless edge between building and nature with the low profile of the southwest point closest to Gärdet national park (Dezeen 2018). Furthermore, the pillar of community living is an undeniable example of Swedish humanistic functionalism.

Figure 3.05: Interior view of BIG’s 79&Park, the living room is flooded with natural light reflected softly on the materials

Figure 3.06: Kitchen/dining BIG’s 79&Park displaying the positioning of the kitchen directly next to a natural light source

Figure 3.07 & 3.08: comparison of 79&Park lounge area (left) and Sven Markelius 1930 model apartment (right)

Stockholm based architecture office Tham & Videgård were commissioned to design the Stockholm School of Architecture at the Royal Institute of Technology in 2015. The driving concept for the building was to encourage and facilitate circulation throughout and around the site. The school was to function as an anchor point, integrating the building within the site (Tham & Videgård). With an emphasis on visual symmetry over linear orientation the curved walls of the exterior and interior delineate programme and circulation paths. The refinement of design intention also informs the surface finishes, as the deep red Corten steel (figure 3.09) is informed by the dark red brick of the surrounding buildings, and juxtaposed against the soft hue of timber-clad interior walls (figure 3.10). Once inside the building, the legibility of the programme is realised immediately, through the use of organic insertions with window cut-outs (Figure 3.10). Users can identify the activities taking place, animating the space and giving a sense of purpose and activity. Within the rooms smooth curved walls with no cornices or mouldings can be found, the response to function addressed with light-weight movable furniture and adjustable lights. Creating a sense of openness and flexibility, catering to the changing needs and processes of design students. The truthfulness regarding structure and materials, and championing of simplicity can be related to the design ideology presented by Asplund, Markelius, and Aalto (Ashby 2017:140).

The internal courtyard on the ground floor seen in figure 3.11 is a semiotic device, orienting users within site and providing a visual connection from within the studio to the outdoors. The ideology of functionalism was grounded in two fundamental concepts; understanding of the function of a space to inform dimensions and layout, and the optimal efficiency in the production process of materials and construction (Marklund & Stadius 2010: 624). Tham & Videgård's building is clad entirely in steel and utilises unfinished concrete surfaces together with tiling and wood panelling on the interior, which made for efficient construction as well as long term durability. Furthermore, the adaptability of the threemeter high studio spaces on levels two, three and four are robust and flexible. An open play layout and 360-degree views make subdivision of space efficiently implemented if necessary (ArchDaily 2015). The layering of space throughout the building employs dual height ceilings and internal windows to create a refined combination of exposure, privacy and connection between levels. Furthermore, the large external windows framed by extended sheets of Corten permit floods of light to wash over the interior significantly influencing the atmosphere and defining visual axes that help delineate the hierarchy of space (Leydecker 2013:220). The influence of Aalto's humanistic sensitivity is seen in the elegant surface details and considered layout imbuing intimacy and warmth into space (Nerdinger 1999), while the use of natural light as a way of yielding a sense of spatiality, is a recurring theme seen in Asplund's body of work.

Figure 3.09: curved Corten steel exterior, in relation to the red brick neighbouring buildings

Figure 3.10: curved interior, timber clad walls with window cut-outs for wayfinding and light permeation

Figure 3.11: internal courtyard of Tham & Videgård’s school of architecture, 2015, highlighting the connection between interior and exterior and circulation function of the courtyard