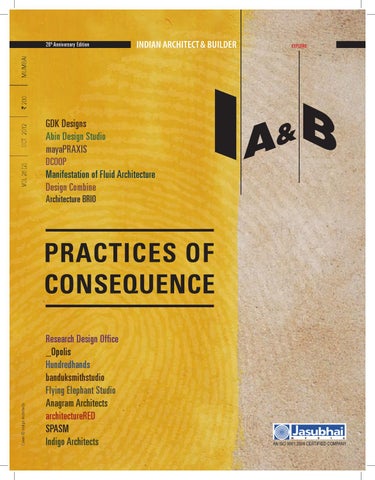

INDIAN ARCHITECT & BUILDER

VOL 26 (2)

OCT 2012

` 200

MUMBAI

26 th Anniversary Edition

GDK Designs Abin Design Studio mayaPRAXIS DCOOP

Manifestation of Fluid Architecture Design Combine Architecture BRIO

Cover Š Indigo Architects

PRACTICES OF CONSEQUENCE Research Design Office _Opolis Hundredhands banduksmithstudio Flying Elephant Studio Anagram Architects architectureRED SPASM Indigo Architects

EXPLORE