INTRODUCTION

On 26 June 1970 it was just getting dark when the night-time stillness was rent by a deafening explosion. Fifteen-year-old John McCool was in the family sitting room at the time: ‘I just heard “boom”. I heard screams and I saw a flash coming out, it was like a fireball.’1 John’s mother, Josie, somehow managed to get him, his brother Kieran and sister Sinead out of the house. ‘I remember my mother grabbing Sinead and us all running out into the street. The smoke was billowing out of the house.’

John looked back and saw his home going up like a torch. In a moment of total panic, he realised his little sisters – nine-yearold Bernadette and three-year-old Carol – were still inside, tucked up in bed upstairs. ‘Neighbours had to pull me away because I was trying to get in to reach them. They had to sit on me to hold me down.’

In truth, there was nothing he could have done. Bernadette was already gone. Carol would die in hospital the next day, even as the doctors and nurses fought to save her young life. An eyewitness told a reporter from The Irish Times that the house was ‘gutted within three minutes of the start of the fire’. Firemen found the body of their father, Tommy, in the kitchen, along with that of his pal Joe Coyle. Coyle was still breathing –just – and was rushed to accident and emergency, only to pass away within a few hours. A third man – family friend Tommy

Carlin – had been blown into a neighbouring garden. He was badly burned but alive.

The McCools lived in Derry city’s Dunree Gardens, on the close-knit Creggan estate, up on the hill overlooking the equally Catholic Bogside, and while the city had been convulsed by unprecedented violence since the previous summer, the horror in Dunree Gardens was at an altogether different level. It could only have been a terrible accident, perhaps a gas leak.

Three days later Tommy McCool was buried. To the surprise of some – though not many – the married forty-yearold father of five was given a paramilitary-style funeral by the organisation that claimed him as one of its own – the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA). There had been no gas leak, no innocent but tragic house fire. The inquest into the deaths was told that a mass of bomb-making material was recovered in the smouldering ruins. That Friday night, Tommy McCool, Joe Coyle and Tommy Carlin were gathered round the McCool kitchen table constructing an incendiary device from homemade explosives. But something had gone terribly wrong, and the bomb had prematurely gone off, killing all three – the bespectacled Carlin would die on 8 July – as well as Bernadette and Carol. Tragically, the two girls weren’t the first children to die in what the world would come to know as ‘the Troubles’.

The three bombmakers were long-time republicans, who had been active in the IRA’s failed Border Campaign of 1956 to 1962, with Tommy Carlin convicted in 1957 of gun possession and sentenced to eight years. By 1970 all three men were among the most senior IRA volunteers in the city, notwithstanding the fact that the organisation itself was rent by division, with a breakaway group storming off the previous December and declaring itself the true inheritors of the republican tradition that stretched all the way back to the Easter Rising of 1916. The

breakaways called themselves the ‘Provisional IRA’ – PIRA –and their core belief was that armed struggle was the only way to achieve a united Ireland and force the British out once and for all.

Initially Belfast-centric, it wasn’t until February 1970 that the Provisionals formally announced that Counties Londonderry and Donegal would come under a new ‘North-West executive’. McCool, Carlin and Coyle were some of the very first Derry men to jump ship to the Provisionals, joining the likes of Seán Keenan and Liam McDaid in the infant organisation. Now, the explosion at Dunree Gardens had given the trio the wholly unwanted title of being the first IRA casualties of this new phase of the republican struggle in Derry. Their deaths transformed the fledgling Provos there, opening the door for a startlingly young group of volunteers – mostly still teenagers – to leapfrog the old guard of the ‘Official IRA’.

The campaign this new generation would launch was first and foremost an economic one, seeking to reduce the centre of Derry and surrounding towns to smoking rubble, and inflict economic damage on such a scale as to precipitate a crisis in government that would lead to a British withdrawal. Standing in their way were what republicans termed the ‘Crown forces’: the British Army and the mainly Protestant members of the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) and the locally raised Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR). For the Provos in the city –operating from their heartlands in the Bogside, Gobnascale, Shantallow and the Creggan – the main enemy in the streets and back alleys would be the regular British Army, while out in the surrounding county of Londonderry, the Provisionals’ South Derry units would predominantly target the RUC and the UDR – often when they were off duty. That campaign –fought out across the county’s fields and townlands – would be

horrifyingly similar to the concurrent slaughter in Fermanagh and Tyrone, setting neighbour against neighbour and leaving a legacy of bitterness and hatred that still exists today. Leading the way for the IRA in south Derry would be three young men pictured on a WANTED poster: Francis Hughes, Ian Milne and Dominic McGlinchey. The trio would wreak havoc for several years, transforming much of the county into a battleground until their capture in the late 1970s – a blow from which the South Derry PIRA never fully recovered.

After a decade of bloodshed, the Troubles changed, entering a new phase marked by an increased professionalism on both sides that made the war in the 1980s something colder and more ruthless. What the Derry IRA didn’t know, however, was that by then it had been infiltrated to its very core by agents and informers working for any one of the many agencies ranged against it. Those agencies – MI5/MI6, Army Intelligence, and most of all RUC Special Branch (SB) – were now in the driving seat of Britain’s war against the paramilitaries and would rip the very heart out of the Derry IRA. Never huge in number, the city’s volunteers would be whittled down, the brigade’s capabilities lessening even as its ranks were haemorrhaging. By the beginning of the 1990s, the Derry PIRA was still active but had subsided into an almost ‘occasional campaign’ that seemed – perhaps – to breathe a sigh of relief when the ceasefire of 1994 finally ushered in an exhausted peace.

For almost the entire war, the Derry Brigade was unique amidst the IRA in being dominated – and commanded for much of its life – by a single individual. Every other IRA unit of any significance had multiple leaders, who came and went as death, prison or retirement took them off the stage, but not so the Derry Provisionals. But then, no one else was Martin McGuinness. In an organisation that had to exist in

the shadows to survive, McGuinness never shied away from the spotlight. The paramilitary career of the teenaged assistant from Doherty’s Butchers, by the Rossville Flats, would take him from throwing rocks at soldiers during his lunch break, to the full-time role of commanding the IRA’s war as its chief of staff. But throughout his decades-long life in the IRA, the constant was Derry, and his total control of the Provisionals in the city and county he called home. McGuinness himself died in 2017, but for the republican Movement, while he was alive Martin McGuinness was Derry, and Derry was Martin McGuinness.

‘STROKE CITY …’

‘… that the said city or town of Derry, forever hereafter be and shall be named and called the city of Londonderry.’

Royal Charter granted by King James I of England and Ireland (previously King James VI of Scotland) to The Honourable The Irish Society, 1613

It speaks volumes of a place that even its name is a cause of dispute. Not only that, but in the occasionally topsy-turvy world of Northern Ireland, whichever moniker someone opts for defines who they are and what tribe they’re from. Derry/ Londonderry, nationalist/unionist – take your pick – the dividing line in Northern Ireland is epitomised by the very name of its second city. It is a struggle that hit the headlines again in 1984 when the nationalist-majority council formally requested that its name be changed from ‘Londonderry City Council’ to ‘Derry City Council’. Loudly condemned at the time by Willie Ross, MP for East Londonderry, as ‘an anti-British move by the most extreme Republican movements in Londonderry and

the rest of Northern Ireland’, a seemingly unconcerned British government in Westminster nodded the change through and the brass plaques proclaiming ‘Londonderry City Council’ were unscrewed and put away. Later, in reference to the habit of some saying ‘Derry/Londonderry’, people began – halfjokingly, half-seriously – to refer to it as ‘Stroke City’.

The city’s original name was Derry, from the Irish Daire or Doire meaning ‘oak grove’, which is why the oak leaf is still its symbol today. The settlement itself was reputedly founded in the sixth century by one of Ireland’s three patron saints: Saint Colmcille (anglicised as Columba), an Irish missionary from Tír Chonaill, the old name for almost all of modern Donegal, of which the west bank of the River Foyle was a part before 1610. It stayed a monastic centre for centuries, only becoming a town of any real significance during the reign of the English Tudor queen Elizabeth I, and it would be Elizabeth, and her successors the Stuarts, who would irrevocably change the course of Irish –and British – history in these islands.

The Tudors had long seen Ireland as a back door through which their continental Catholic enemies could attack England. To see off this threat, their solution was as novel as it was ruthless – dispossess the native people and their Gaelic aristocracy and settle large parts of the island with ‘loyal’ Protestant English and Scottish colonists. This strategy – and the danger it was designed to nullify – has dominated the relationship between Britain and Ireland ever since. From the 1500s, incomers –predominantly English peasants – had been shipped to the east and south of Ireland, establishing ‘the Pale’ – the settlement extending outwards from Dublin and encompassing large tracts of today’s counties of Meath, Offaly, Laois and Kildare. However, the end of the Nine Years’ War, and the subsequent Flight of the Earls in 1607, spurred on an even more ambitious

royal plan: the Plantation of Ulster. Ulster, the northern-most region of Ireland, had long been the part of the country most resistant to English control. The Anglo-Scottish King James I planned to change this by seizing half a million acres of land and redistributing it to English and Scottish lords and other interested parties, the most important of which was the newly established The Honourable The Irish Society.

Created to take advantage of James’s plan, the society was a consortium of the Great Twelve Livery Companies of the City of London: the Mercers (general merchants), Grocers, Drapers, Fishmongers, Goldsmiths, Skinners, Merchant Tailors, Haberdashers, Salters, Ironmongers, Vintners and Clothworkers. With no time to waste, the society’s agents travelled to Ulster to assess the project’s potential, and their favourable report encouraged the guilds to accept a Royal Charter from James, gifting them both the town of Derry and huge tracts of land around it. James, however, wasn’t known for his generosity, and this extraordinary policy was something of a double-edged sword for the guilds, as in return they were expected to spend a great deal of money building a fortified citadel on the existing site of Derry, as well as settling their newly gifted lands with imported Protestants from Scotland and England. To seal the deal, the ‘new’ city would henceforth be known as ‘Londonderry’, in tribute to those paying for the privilege. From then on, to call the city Derry was to proclaim your ancestry as being native Irish and Catholic, while using its official name was equally to mark you out as a descendant of the Protestant incomers.

Fulfilling their end of the bargain, the Irish Society raised some £60,000 – an enormous sum at the time – to greatly expand and fortify the city of Londonderry and settle much of the surrounding territory, hitherto called County Coleraine

but now renamed County Londonderry in their honour. The county was divided into twelve ‘proportions’ and distributed amongst the respective guilds by the drawing of lots. Each guild then set about developing their new landholdings, such as the Salters, who had drawn Magherafelt and its surrounding district, and the Worshipful Company of Vintners, who built a village some five miles to the northeast of Magherafelt, which they named Bellaghy, from the Irish Baile Eachaidh (Eachaidh’s town). Soon, Bellaghy had a church, a cornmill and a dozen homes, all protected by a fortified house built on the site of an ancient Gaelic ringfort.

The biggest transformation, however, was in Londonderry itself, where the Irish Society had undertaken to build nothing less than a new city. That city would be walled and designed to be the cornerstone of British control of Ireland’s far northwest. Between 1614 and 1618 the mile-long ramparts, which still enclose the city centre on the River Foyle’s western bank, were completed at enormous expense, fuelling Londonderry’s growth.

As important as its establishment as a walled city was, arguably the defining event in Londonderry’s early history occurred in December 1688, when thirteen local Protestant apprentice boys barred the city gates to a 1,200-strong contingent of soldiers sent to seize the fortress by the English Catholic king, James II. This marked the beginning of the Siege of Derry. With James’s Catholic army camped outside, the city’s staunchly Protestant citizenry shouted their defiance from the walls, with ringing cries of ‘No Surrender!’ As in so many sieges, hunger was the key, and the inhabitants were forced to eat dogs and rats to survive until they were relieved on 28 July 1689 by two armed merchant ships. Alas, the ships came too late for half the city’s population, who had already died mostly from

starvation and disease. Its walls unbreached and its honour intact, Londonderry was nicknamed the ‘Maiden City’, and ever since then the city’s Protestants have commemorated their victory with parades and celebrations, one of which would eventually act as the starting gun to mass civil disturbance almost three centuries later in 1969.

Holding out against the Catholic James in favour of the Protestant William of Orange had a somewhat unexpected effect on the city, when the newly crowned William III – as the Dutchman now became – signed a royal decree allowing Irish linen to be imported to England free of excise duty. William also encouraged Protestant French Huguenots – exiled from their overwhelmingly Catholic homeland – to settle in Ulster and utilise their expertise in advanced linen production to the good of the burgeoning local industry. There followed an explosion in linen manufacture across the north, especially in the city and county of Londonderry, which partly made up for decades of economic restrictions and neglect that had left much of the north of Ireland outside Belfast struggling and impoverished. As the linen industry grew and fashions evolved, Londonderry began to specialise in shirt production, with factory after factory built to satisfy the insatiable demand. Large numbers of workers were needed for these factories, and the relatively decent wages on offer acted as a powerful magnet to draw labour into the city. Many of the workers were native Catholics who, traditionally excluded from living inside the city’s walls, found themselves forced to live in squalor on marshland to the west, nicknamed ‘the Bogside’. Eventually, conditions were improved in the nineteenth century with the building of rows of Victorian terraces and tenements to accommodate the population, but while the establishment of the Bogside on a surer footing was welcome to its residents,

it also reinforced a growing sectarian divide in the city, with Protestants overwhelmingly living on the east bank of the Foyle and Catholics on the west, a position that remains much the same today.

This Protestant vs Catholic divide, which festers at the very heart of life in Northern Ireland and infects so much of its turbulent history, was brought into sharp focus in the run-up to the First World War. The recurring issue of Home Rule for Ireland had once again come to the fore, eliciting a fervid response from the Dublin-born Protestant barrister Sir Edward Carson, whose signing of Ulster’s Solemn League and Covenant in late 1912 promising to resist Home Rule by any and ‘all means necessary’ was the inspiration for the creation of the paramilitary Ulster Volunteers (UVs) the same year. The fervour exhibited for this new force among many of the north’s Protestants was not mirrored in Londonderry, either in the city or the county, with the Royal Irish Constabulary’s County Inspector – the Galway Protestant George Carey – declaring to a friend that there was little sign that local loyalists would ‘really resort to open force’. His view was supported by the lacklustre response to local UV recruitment drives, with only around 700 volunteers coming forward from the city and as few as 300 from across the rest of the county.

Londonderry’s placid approach to the growing crisis was, however, blown apart by Carson’s summer tour of Ulster in 1913 to mark the first anniversary of the Covenant. His firebrand speeches led to riots breaking out in the city on 12 August that went on for three straight nights and left a local Protestant man – Francis Armstrong – dead, fatally wounded by a gunshot in the loyalist enclave of the Fountain on the city’s west bank. In the aftermath, shocked members of both communities flocked to their respective armed militia, with

over 7,000 Derry Catholics joining the Irish Volunteers after its establishment in November that year, and Londonderry’s UVF – Ulster Volunteer Force, as the UVs became known after a reorganisation – expanding more than nine-fold by the end of September. Both sides brought in smuggled guns from Imperial Germany, with the UVF’s Larne shipments ensuring over a third of the men in its Londonderry ranks had a rifle, in stark contrast to their Catholic foes who had fewer than one rifle for every ten men.

Civil war loomed but was unceremoniously shunted off the agenda by something even bloodier – the Kaiser’s invasion of Belgium and France. As Europe’s complex and interlocking web of agreements and alliances set the Continent alight, the two sides figuratively laid down their arms in common cause and Home Rule was postponed until the war’s end. Some Irish Catholics thought the war in Europe had little to do with them, but, as long as conscription was not imposed on Ireland, the majority of the populace firmly supported the struggle. Indeed, in Londonderry one commentator went as far as saying that relations in the city between Catholic nationalists and Protestant unionists ‘appear to be, and are, more friendly since the outbreak of war’, although he also noted that ‘under the surface the old party bitterness is still strong’.1

Whatever the truth, the war hit the city hard, as the collapse in the importation of Belgian flax caused the linen trade to crash. Mass unemployment, and the poverty and hunger that came with it, was seen by the local populace as far more pressing than independence, hence the Easter Rising of 1916 was something of a non-event in Londonderry. However, the vengefulness of Britain’s response to the Rising – with the execution by firing squad of most of its surviving leaders – was a grave misjudgement, turning rebels into martyrs and breathing

new life into the republican cause. Home Rule now seemed thin gruel, and across Ireland agitation grew for something more. Sinn Féin’s victory in the 1918 general election led to them establishing a separate Irish parliament on 21 January 1919 – Dáil Éireann – which promptly declared the foundation of an independent Republic of Ireland, to be defended by its own armed force: the Irish Republican Army (IRA).

Ireland was in crisis, and this time Londonderry wasn’t immune. The municipal elections of January 1920 were conducted in a febrile atmosphere of rising tension, and when the results gave nationalists control of the city for the very first time, everyone waited with bated breath to see what would happen. Intercommunal rioting grew into a plague, with shots fired by both sides. On Friday 18 June unionist snipers began firing into the nationalist Long Tower district, and the local IRA fired back, leading to a violent unionist backlash. Dorothy Macardle’s book The Irish Republic, published not long after the events it concerned, described what happened that fateful summer:

On that night [19 June] armed mobs rushed upon the Catholic quarter of the city, setting fire to houses, shooting, looting and wrecking shops; they carried the Union Jack and the military didn’t intervene. During the four nights and days the street fighting went on, over 50 persons were wounded and 19 were killed. At last the military intervened, but only to fire upon members of the IRA who had undertaken to protect property and were standing on guard.2

Fighting was now widespread across Ireland in what became the Irish War of Independence – or the ‘Tan War’ as most

republicans call it – as a war-weary Britain struggled to maintain control. Both sides indulged in horror in a war marked by viciousness and atrocity, but, throughout, the northwest of the island was relatively quiet, thankfully spared the level of violence experienced in the south and west of the country.

The Protestant majority in Counties Londonderry, Armagh, Antrim, Down, Fermanagh and Tyrone were determined not to break the link with Britain and to remain in the Empire, even if that meant casting adrift their Protestant brethren in the other three of Ulster’s original nine counties. As Charles Craig, the Unionist MP for County Antrim, remarked in a speech to Westminster’s House of Commons on the subject: ‘The three excluded counties [Cavan, Donegal and Monaghan] contain some 70,000 unionists and 260,000 Sinn Féiners and Nationalists, and the addition of that large block of Sinn Féiners and Nationalists would reduce our [Unionist] majority to such a level that no sane man would undertake to carry on a Parliament with it.’3 In the end the British imposed the 1920 Government of Ireland Act, which created two self-governing entities: the six-county statelet of ‘Northern Ireland’ and the twenty-six-county ‘Southern Ireland’.

Uproar ensued across Ireland and the fighting continued, with the IRA determined to achieve a republic that included the newly partitioned six counties. In July 1921 a truce was declared and negotiations started in London between David Lloyd George’s government and an Irish delegation which included the charismatic Michael Collins. These dragged on from October to December, leading to an unhappy compromise and a treaty that has been a massive source of controversy ever since. Collins – instrumental in the whole process – mused to himself on what he knew would be a very bitter pill to swallow, wondering in a letter to a friend, ‘what have I got for Ireland?

Something which she has wanted these past 700 years? Will anyone be satisfied at the bargain?’

It seemed the answer was ‘no’, with the IRA splitting into proand anti-Treaty factions as a bloody civil war broke out. Derry city’s own IRA battalion was anti-Treaty, viewing partition as a cleaving of the city’s historic relationship with neighbouring Donegal, but, unlike in other parts of Ireland, there was relatively little fighting and a general belief that a proposed Boundary Commission outlined in the Treaty would come to a more favourable solution for nationalists. As preparation for the commission to start its work ground on, a number of suggestions were made as to the possible approaches it might take, the most important being the use of ‘county votes’ for the border regions of Fermanagh, Tyrone and Londonderry. The proposal was anathema to Derry’s nationalists, whose Church and community leaders met in St Columb’s Hall on 14 June 1922 to debate the matter. The issue was clear: the city had a narrow nationalist majority, but Protestants outnumbered Catholics in the county as a whole, so a county-wide vote would keep the city inside Northern Ireland. The meeting broke up after agreeing that if Westminster opted for the county vote proposal, Derry city’s nationalist leadership would insist on going its own way and joining with Donegal in the new Irish Free State.

As Northern Ireland’s second city, and traditional home to so much of Protestant Ireland’s historic heritage and identity, this was never a realistic option. Indeed, for one of the Boundary Commission’s own members – attorney and newspaper editor Joseph Fisher – the reverse idea was selfevident: ‘Ulster can never be complete without Donegal.’ Fisher wasn’t alone. Many unionists felt the same, including Charles Craig’s brother and fellow MP, James Craig, who pointedly declared that ‘Donegal belongs to Derry and Derry Donegal’,

which both acknowledged how strong the ties were between the two as well as laying claim to Ireland’s most northern county. But, just as there was never any chance unionists would hand the city over to the Free State, there was equally no way nationalists would agree to Donegal being incorporated into Northern Ireland. In the end, the sweeping changes to the map that nationalists had hoped for were left unfulfilled, and the border remained as originally drawn. Partition resulted in 730,000 Protestants suspiciously eyeing 420,000 Catholics in Northern Ireland, while in the south 2.8 million Catholics totally dominated 327,000 Protestants. Both sides felt the loss, and both minorities were united in feeling abandoned by their co-religionists across the new border.

As it turned out, the confirmation of partition didn’t beget a return to war, and neither did it presage the economic collapse in the northwest that many had predicted when Londonderry was cut off from Donegal. In fact, a follow-up study in 1925 to gauge the economic impact reported that far more damage had been done to the city and county by the Free State’s decision to impose duties on goods from Derry and to import coal and export potatoes from Letterkenny and Ramelton in Donegal instead.

The outbreak of the Second World War saw Éamon de Valera’s Éire – as the Irish Free State had now become known – declare its neutrality, while Northern Ireland played its role in fighting to rid the world of Nazism, partly by acting as a transit point for the increasingly important British–American cross-Atlantic shipping. The IRA – which had never gone away – launched a desultory campaign to try to take advantage of the war and achieve Irish unification but was stymied by the introduction of internment without trial both north and south of the border. The Derry IRA’s 150 members were quickly reduced to impotence by the RUC, and especially the Stormont

government’s use of the Ulster Special Constabulary (USC) – the ‘B-Men’, or ‘B-Specials’, so detested by republicans. Internees on both sides of the border were often treated brutally – four died of medical neglect in prison – and when peace duly arrived in 1945 many IRA men quit the Movement.

Even worse for the republican cause were the different postwar economic trajectories of Northern Ireland and the Republic. As part of Great Britain, the North benefited from the largesse of America’s Marshall Plan to rebuild post-war Europe, whereas Dublin’s neutrality meant no American dollars flowed to the south. The result was a boom in Northern Ireland’s economy and a nasty recession in the Irish Republic. Coupled with Britain’s creation of the Welfare State, with a taxpayer-funded National Health Service and a social safety net, many northern Catholics were convinced that unification with the south would deliver nothing more than unemployment and poverty.

By the mid-1950s Irish republicanism looked a lost cause. The unionist government in Stormont was deeply entrenched, and Northern Ireland seemed to have moved on from partition and accepted its place in the United Kingdom. In Londonderry a burgeoning economy meant big demographic changes, with the city’s Protestants outgrowing the walled city and expanding into new territory east of the River Foyle in the aptly named Waterside district. Derry’s Catholic population had also increased and were accommodated in the new Creggan and Shantallow estates on the west bank. There was some mixing, with Catholics living in Gobnascale, centred on the Old Strabane Road in Waterside, while Protestants clung on in the Fountain enclave near the Bogside, but in practical terms the river continued to act as a barrier between the two communities, allowing them to be born, grow up and die while remaining ignorant of one another.

The IRA, however, had not given up on its avowed mission, and remained determined to unify the country by force. Its next attempt to achieve that goal began in the sleet and snow of the night of Wednesday, 12 December 1956. At around 11.30 p.m. a car pulled up outside the BBC’s radio transmitter site near Northland Drive in Rosemount, on the city’s western side. There were five men inside. Two got out, jumped over the low wall surrounding the main building, smashed a window on the ground floor and threw what the police later described as ‘a sticky device’ into what was the main control room. The duo ran back to the car and it sped away into the night. Minutes later the device exploded, badly damaging the transmitter and blowing out windows in nearby houses.

At the same time, a twelve-man team wearing stolen RUC uniforms tried and failed to destroy the British Territorial Army drill hall in Magherafelt, some forty miles to the southeast of Londonderry. Their commander, a seventeen-year-old from County Wicklow called Séamus Costello, nicknamed ‘the Boy General’ on account of his youth, decided to switch to their secondary target, the town’s courthouse. Banging on the door brought out the building’s caretaker, who was told to get his family and clear out. The IRA team then poured a mixture of petrol, paraffin and creosote over the floor and furniture and set it alight.

Other planned attacks – to destroy Derry city’s customs stations and tax office, to seize the police station in Dungiven and put the Lisahally Oil Refinery out of operation – all failed to materialise. A fear of being betrayed to the RUC had led the offensive’s organisers to only give the Derry IRA twelve hours’ notice of the start of what they termed ‘Operation Harvest’, which became popularly known as the Border Campaign. It was intended that Derry would be a focal point for the new

offensive’s first phase, effectively cutting the city off from County Antrim to the northeast and separating it from south Derry. The second phase would see the fighting spread all along the border to encompass Tyrone, Fermanagh, south Armagh and south Down. It was an ambitious plan and one for which the IRA of the time was wholly unequipped and untrained to deliver. The opening attacks in County Londonderry proved the point. Magherafelt’s courthouse was indeed badly burnt, but it was salvageable and reopened to cases the day after the Costello raid. As for the Rosemount radio station, the BBC shipped in two mobile transmitters and a host of engineers from Lisburn to get it up and running again. A BBC spokesman issued a statement to the press saying that the blast had caused a lot of damage but that the recovery team ‘have worked like blacks all day and all night and will continue non-stop tomorrow’.4 It is impossible to imagine such a statement being made today. As for the transmitter, it was working perfectly within twenty-four hours.

The Derry IRA tried to maintain some sort of impetus in the campaign, but operations were sporadic at best. On 22 January 1957 a South Derry unit attacked a police hut in the village of Claudy, while another damaged a bridge in the Glenshane Pass. Neither action was of great significance. The South Derry IRA was then dealt a major blow when Séamus Costello was badly injured in a safe house by another volunteer accidentally setting off a hand grenade. Costello lost a finger and was evacuated back to Wicklow to recover. Alerted to his arrival, the gardaí arrested the Boy General and he was sentenced to six months in Mountjoy Prison. On his release he was immediately rearrested and interned at the Curragh camp for a further two years.

In Derry city the IRA commander – a railway clerk called Eamon Timoney – was forced to go on the run (OTR) when

the city was swamped by the ever-present B-Specials. The RUC caught up with Timoney on 30 March 1957, and he spent the rest of the Border Campaign in Crumlin Road Gaol in Belfast, after being sentenced to ten years. In his absence the Derry IRA was all but destroyed, its leading lights arrested, convicted and imprisoned alongside their former leader.

The failure of the Derry IRA was mirrored across Northern Ireland, as Dublin and Stormont jointly used internment without trial to choke off the Border Campaign at source. Over 300 republicans were imprisoned North and South, and in a fit of despair, in February 1962, the IRA dumped arms and called off the offensive. It was a chastening defeat for republicans, and one which seemed on the face of it to sound the death knell of their struggle.

Stained glass window in Londonderry’s Guildhall depicting agents surveying the county for The Honorable The Irish Society in 1609. The inscription reads: ‘The four citizens from London viewing the site of the proposed colony.’ (Author’s collection)

Memorial stone to Francis McCloskey set in the pavement of Main Street, Dungiven. (Author’s collection)

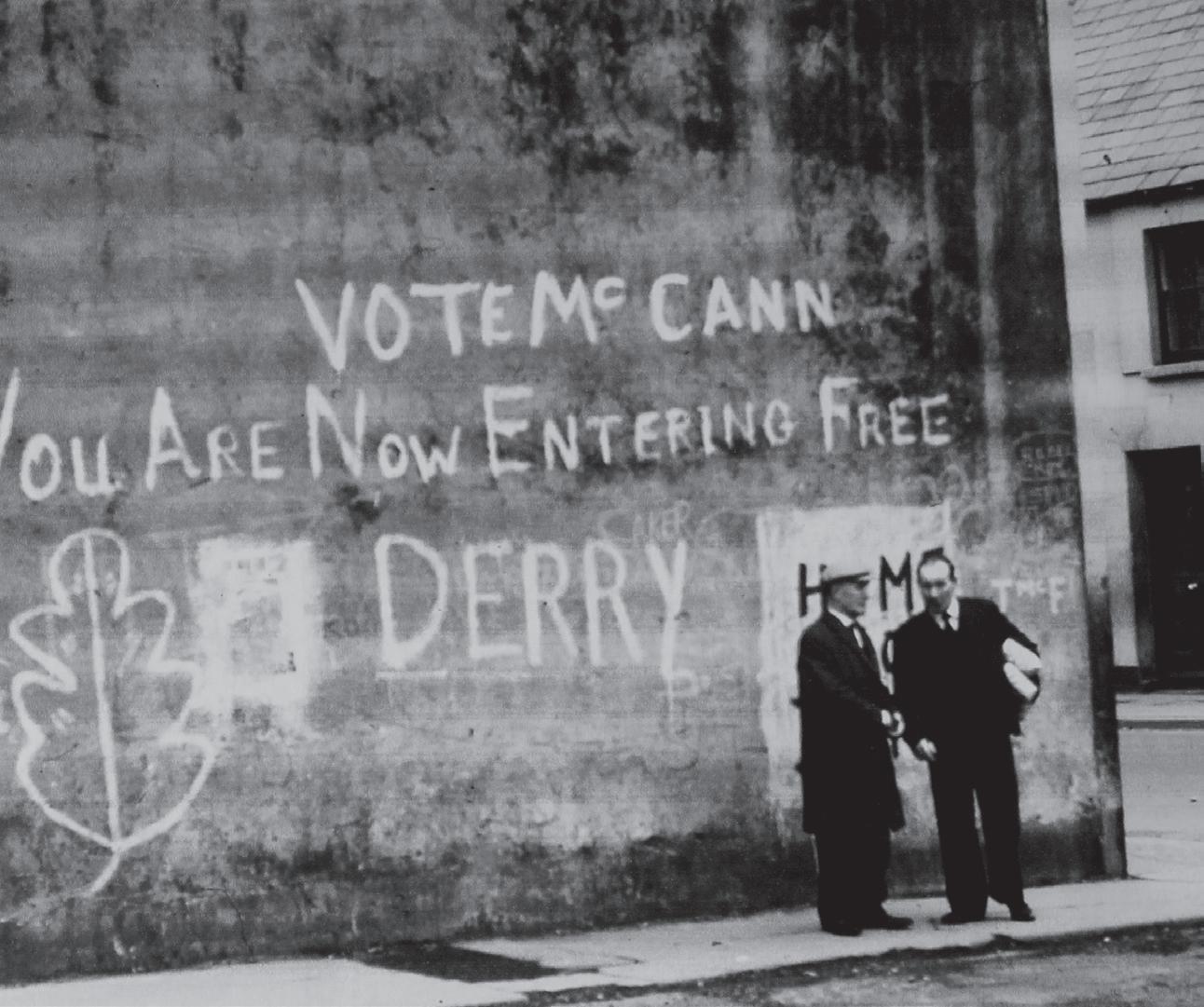

Supposedly the first time ‘You are now entering Free Derry’ was painted on a wall at the corner of Lecky Road and Fahan Street in the Bogside, January 1969. (Courtesy of Jim Davies)

The arrival of the British Army on the streets of the city was a profound shock for soldiers and civilians alike. (Author’s collection)

‘Friendly’ rioting on the streets of the city in 1971. (Author’s collection)

Four masked volunteers from the Derry Brigade fire a volley over the grave of their comrade Eamonn Lafferty on 25 August 1971. (Author’s collection)

Above: Nineteen-year-old Marta Doherty from the Bogside; right: Marta after being tarred and feathered and tied to a lamppost by a crowd screaming ‘Soldier lover!’

(Author’s collection)

Mural in the Bogside depicting the horror of Bloody Sunday. (Author’s collection)