LUIS NIEVES FALCÓN

EDITORIALUNIVERSITARIA

ocTOR LuisNievesFalcón,aprofoundresearcherinthefieldof socio-pedagogicalproblems,wasborn inthetownofBayamón,PuertoRico, onDecember29,1929.

AftergraduatingattheUniversity ofPuertoRico.asaBachelorofSocial Sciences,withanEducationmayor, in1950,hetaughtattheHighSchools ofOrocovis,ComeríoandBayamón. In1956hetookhisMaster'sdegree inSociologyatNewYorkUniversity, andthereuponbecameamemberof thefacultyattheUniversityofPuerto Rico,withtherankofinstructoruntil 1958.ShortyafterhewenttoEngland to prepare his doctorate at the LondonSchoolofEconomicsandPolitical Sciences.

UponhisreturntoPuertoRicoand itsStateUniversity,hewasnamed AssistantDirectoroftheSocialResearch Center,Collegeof Social Sciences,andastudyon"Social ConsecuencesintheSchools"was conductedunderhim.

In1962hewentbacktotheLondon SchoolofEconomicsandPolitical SciencestograduateasaDoctorin PhilosophyatitsFacultyofArts, beingsofartheonlyPuertoRican graduatedatthatinstitution.

Morerecentlyhewasinvitedby theInternationalCouncilofSocial Sciences(Unesco)totakepartinthe InternationalConferenceofComparativeSocialStudiesforDeveloping Countries,whichtookplaceinBuenos Aires,Argentina,inSeptember1964.

AtpresentheisDirectorofthe CenterofPedagogicResearchatthe UniversityofPuertoRico,withthe rankofAssistantProfessor.

Copyright, 1965.

199,O -1960

EDITORIAL UNIVERSITARIA

UNIVERSIDADDEPUERTORICO

RIO PIEDRAS

L965

)(TIS nevereasytotracethesourcesofaman'sthinking.In .J( fact,variousconceptsadoptedinthisstudyhavealreadybecomethestock-in-tradeofthesocialscientist.Moreover,theinception,development,andprogressivemodificationsofthestudy initsseveralphasesmouldnothavebeenquitefeasiblewithout theinitiative,tolerance,expertadvice,andpatientpracticalhelp ofvariouspersons.Tothemtheauthormouldliketomakethis modestgestureofacknowledgment,atthesametimereleasing themfromanyresponsibilityforthefinalformwhichthetext hastaken,particularlytheconclusionsandjudgmentsdrawnto emphwsizethefindings.

ProfessorD.V.Glass,headoftheDepartmentofSociology, LondonSchoolofEconomicsandPoliticalScience,forhissustainedscrutinyofthedataanalysesandforhisstimulatingand instructiveadvice thereon.

Dr.MillardHansen,DirectoroftheSocialScienceResearch Center,UniversityofPuertoRico,forlaunchingtheprojectof whichthisstudyisapart.

DeansOscarE.PorrataandAugustoBobonis,CollegeofEducation,UniversityofPuertoRico,forrecommendingthegrantof atwo-yearstudyleavetoenablethegranteetofurtherworkfor thePh.D.degreeonthebasisofthisstudy.

Dr.AsherTropp,ReaderattheLondonSchoolofEconomics, andhiswife,LynnTropp,forreadingthedraftmanuscriptand providinginsightsandsuggestions.

Dr.JaimeBenítez,Chancellor,UniversityofPuertoRico,for grantingpermissiontouseUniversityrecords.

Dr.EfraínSánchezHidalgo,formerSecretaryofEducation, forpermissiontousepublicsecondaryschoolrecordsandtodistributethehighschoolquestionnaire,alsotouseavailabledata attheOfficeofStatistics.

ThevariousdeansintheUniversityofPuertoRico,RíoPiedrascampus,theRegistrar,andpersonneloftheRepordsOffice andtheStudents'OrientationCenter,forfacilitatingtheuseof theirrecordsfiles,andtheIBMCenterforprovidingfacilitiesfor processingthedata:

Thehighschoolseniorsandfreshmanstudentswhowillingly filledthequestionnaires.

Thefollowingpersonswhoinonewayoranothercontributed tóthepracticalphasesofthestudy:AngelinaRoca,AnaTeresa Fábregas,AdadeJesúsNegrón,CeliaRodríguezPacheco,Angela LópezTorres,AlejandroRodríguezFortyz,MiltónBaigésChapel, PaquitaLimardo,CarmenH.López,CarmenEleonoraAranaCa'stró,ConchitáTorruellas,MaríaC.JiménezdePeña,andMaryTutt:..

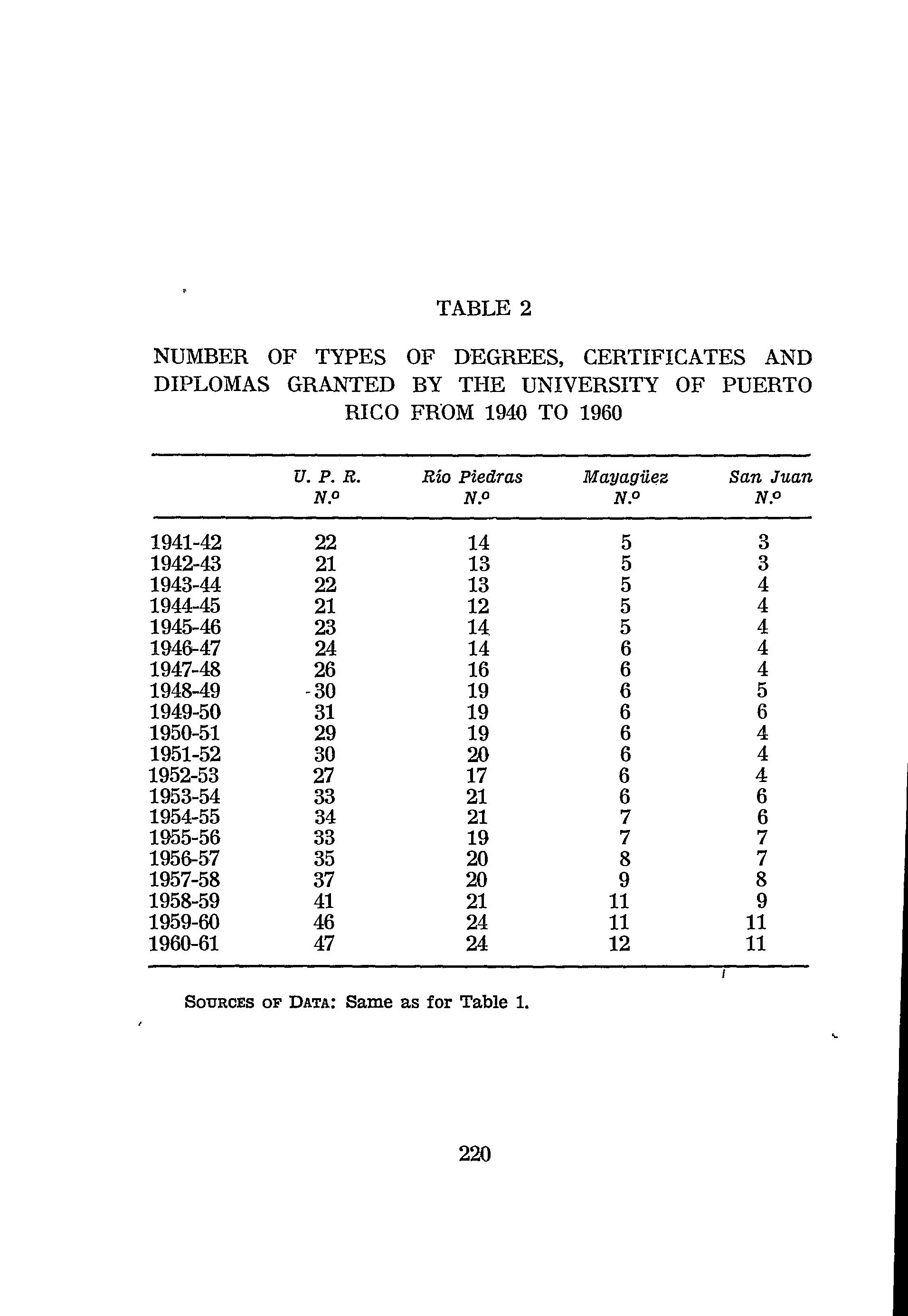

Education in Puerto Rico is graded into the elementary (6years),secondary(3yearsinjuniorhighschooland3insenior high),andcollegiatelevels.Practicallyallschoolsatthefirsttwo stagesarepublic,orstate-supported.Thesepublicschoolstake 92percentofalltheelementaryschoolchildren,92ofthejunior highand86oftheseniorhigh.Universityeducationisalsopredominantlyastateundertaking,althoughtoalessextentnowthan itwasbefore;73percentofallthecollegestudentsinthe.island wereenrolledinthestateuniversityin1960-61,comparedto93at thebeginningofthetwenty-yearperiodselectedforthisstudy.

The publicinstitution which houses three-quarters of the college-studentsintheislandiscalledtheUniversityofPuerto Rico.Ithasexpandedveryrapidlyduringthelasttwodecades. Thetotalenrolmentinallitsthreecampusesincreasedfrom5,869 in1940-41to18,891in1960-61.TheRioPiedrascampus,which isthesubjectofthisstudy,registeredarisefrom5,099to13,532 betweenthosetwoacademicyears.Thecriteriaforadmissionto theUniversityarethehighschoolgraduationindexandacompetitiveentranceexamination.Aconsiderableamountoffinancialassistance,inavarietyofforms,isavailabletostudentswho mayneedit.Theextentofsuchassistancemaybegaugedfrom thefactthatabout47%ofthestudentsinthe1960-61academic yearattheRioPiedrasCampusreceivedsomekindofassistance. Theaverageamountofassistancegivenwas$266,whichrepresents about29%ofthe$922whichUniversityofficialshavecalculated astheaverageyearlyexpensesforauniversitystudent.

Oneofthemainobjectivesofthisstudyistoseetheextentto whichtheopportunitiesforhighereducationinPuertoRicohave changed.Forthispurposethesocialcompositionofthestudentbody

attheUniversityofPuertoRicofromto1940to1960isanalyzed. Recruitmentintermsofsex,rural-urbanresidenceandschoolof originisanotherimportantaspectforconsideration.Thus,this studywillattemptto definethesocialcharacteristicsof those segmentsofthepopulationwhichareavailingthemselves of the newandexpandededucationalfacilitiesofferedattheUniversity. Itwillalsoseektolocatetheshift,ifany,inthesocialstatusof thestudentsthroughouttheperiodchosenfortheinquiry.

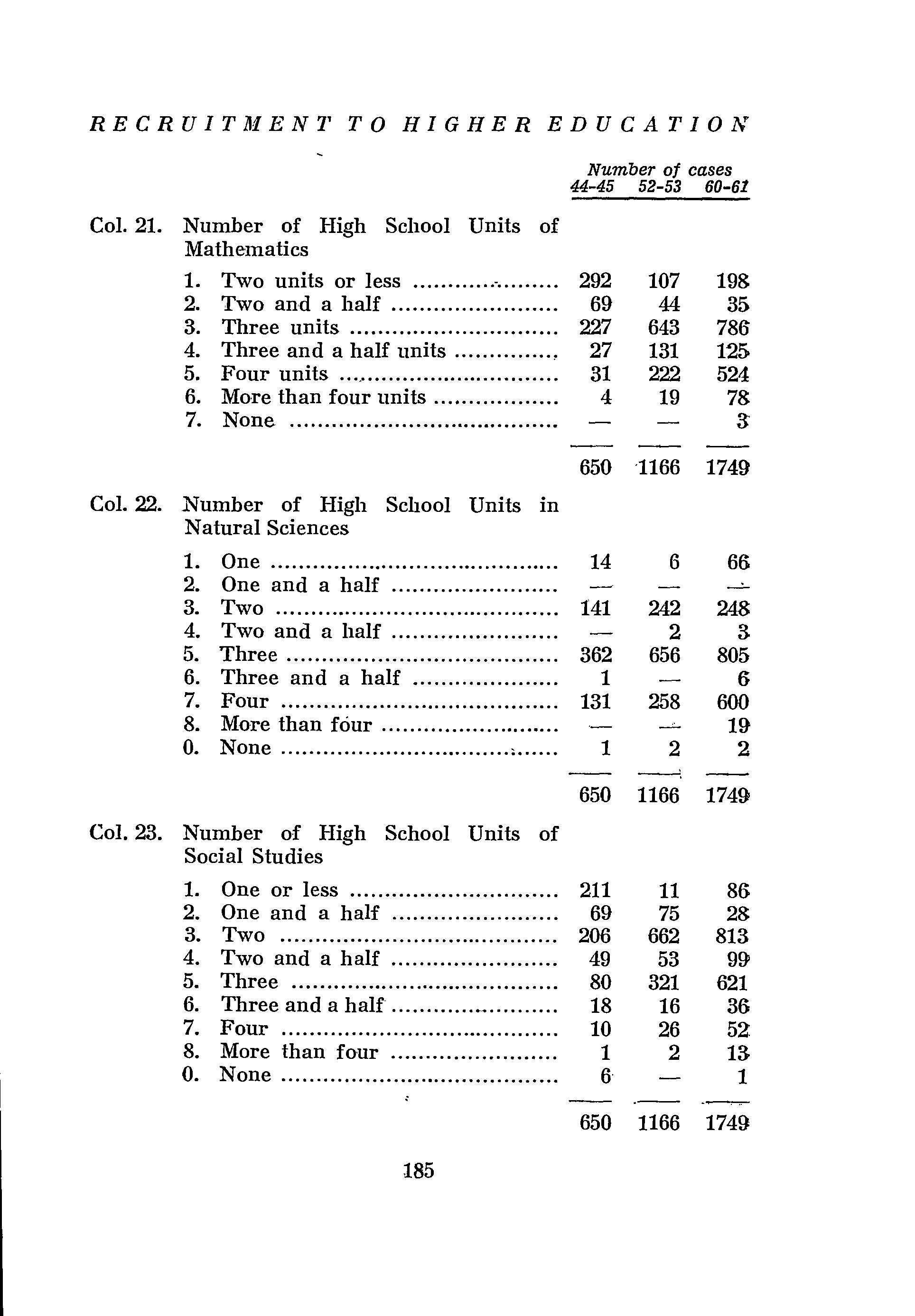

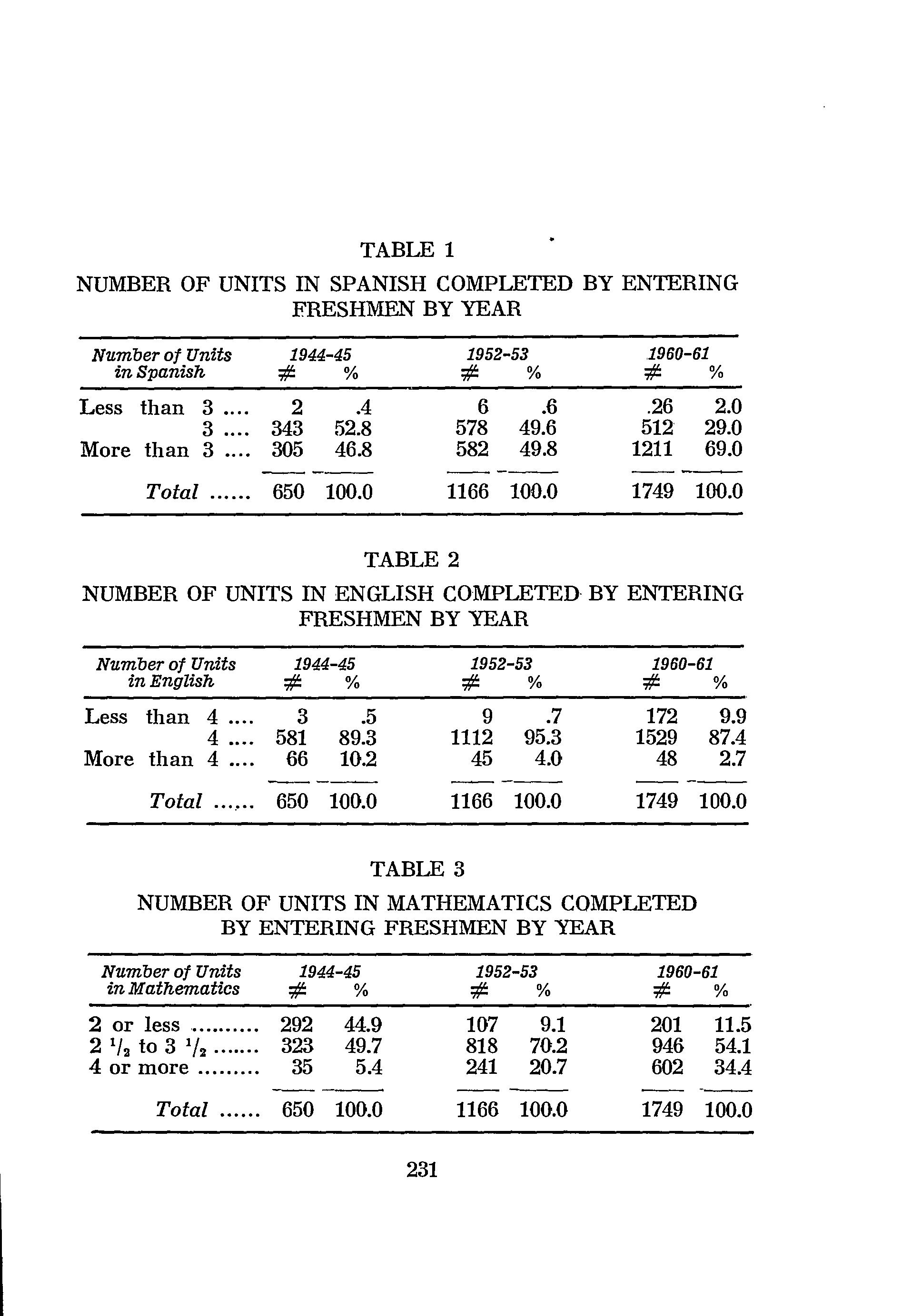

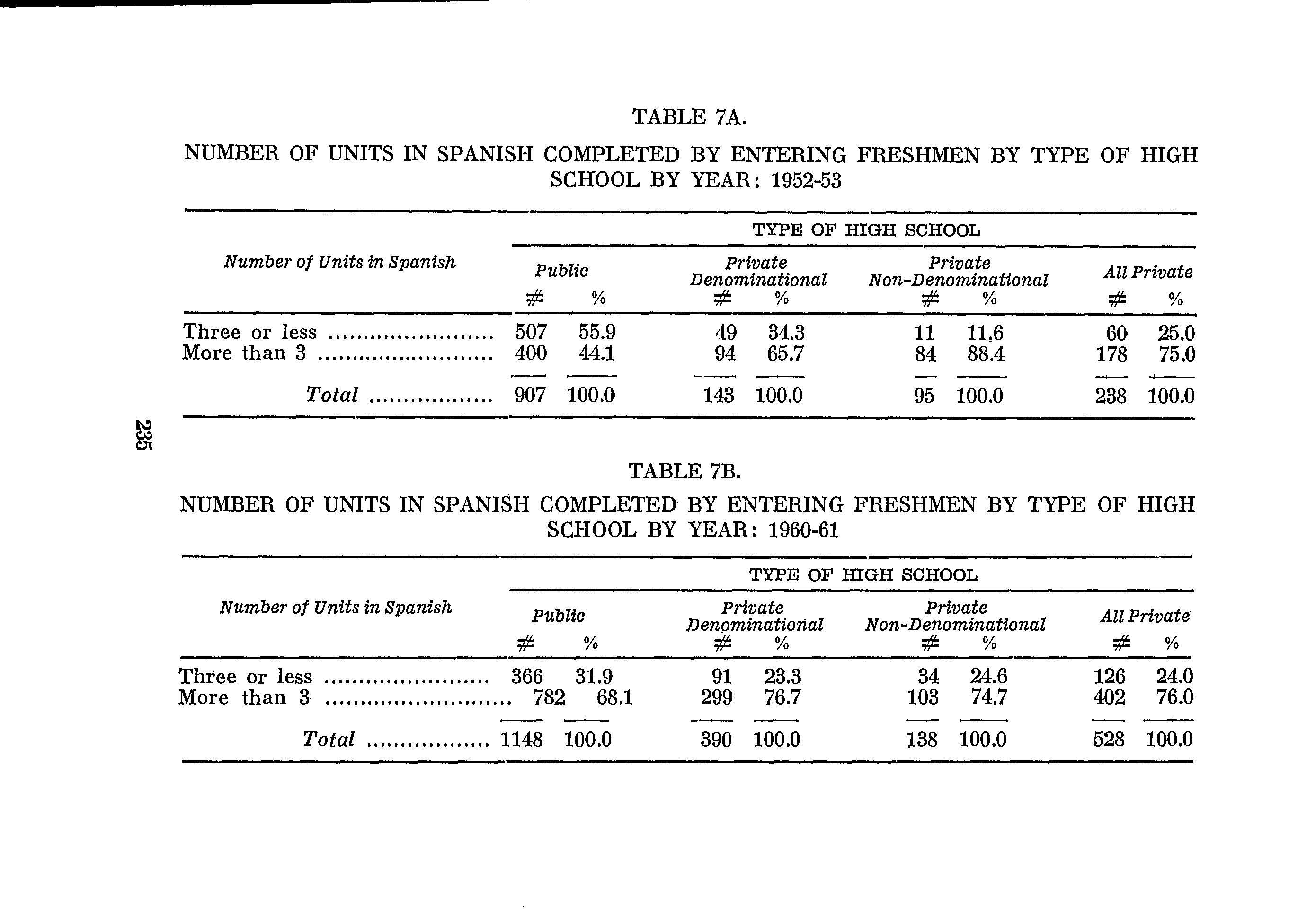

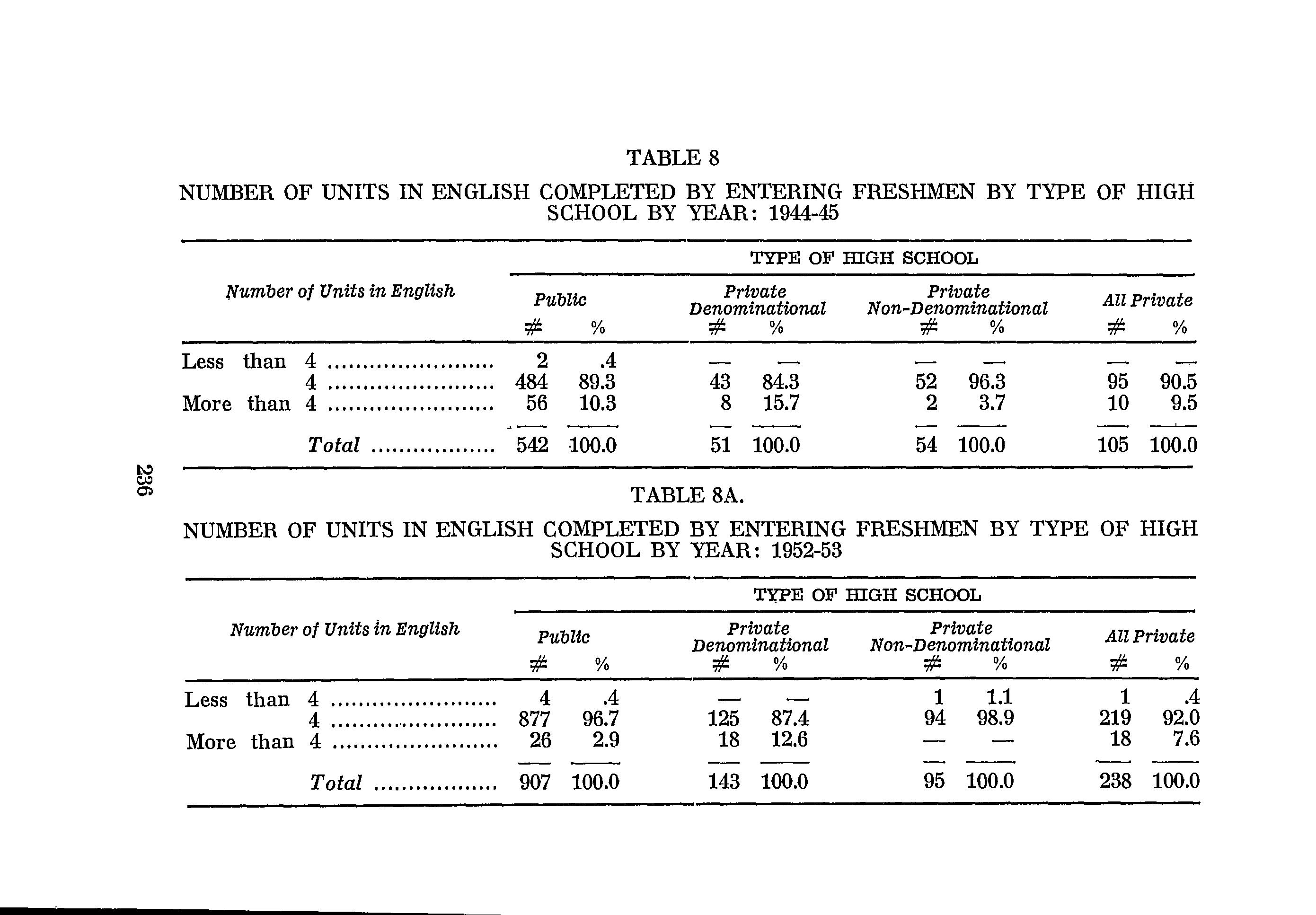

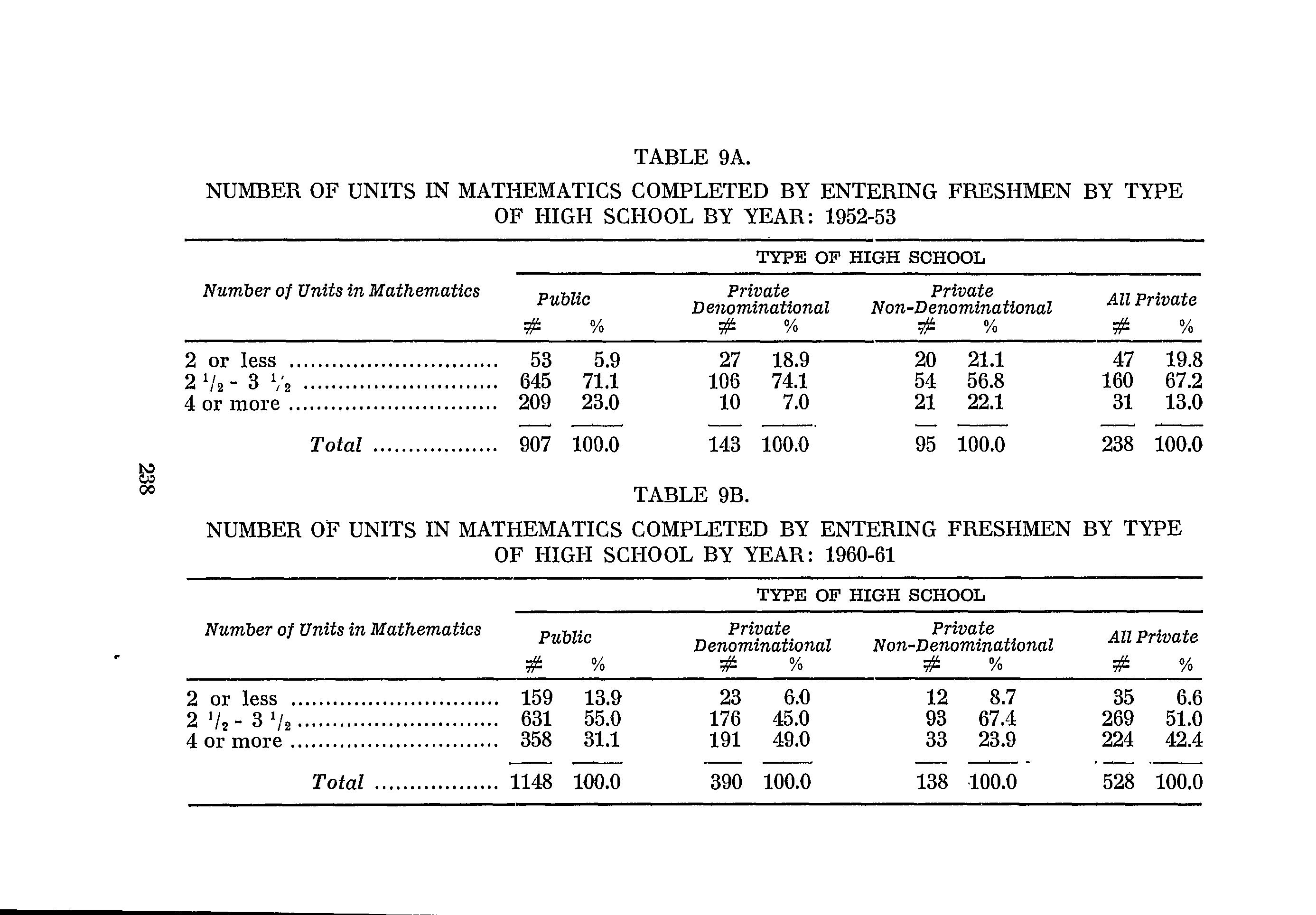

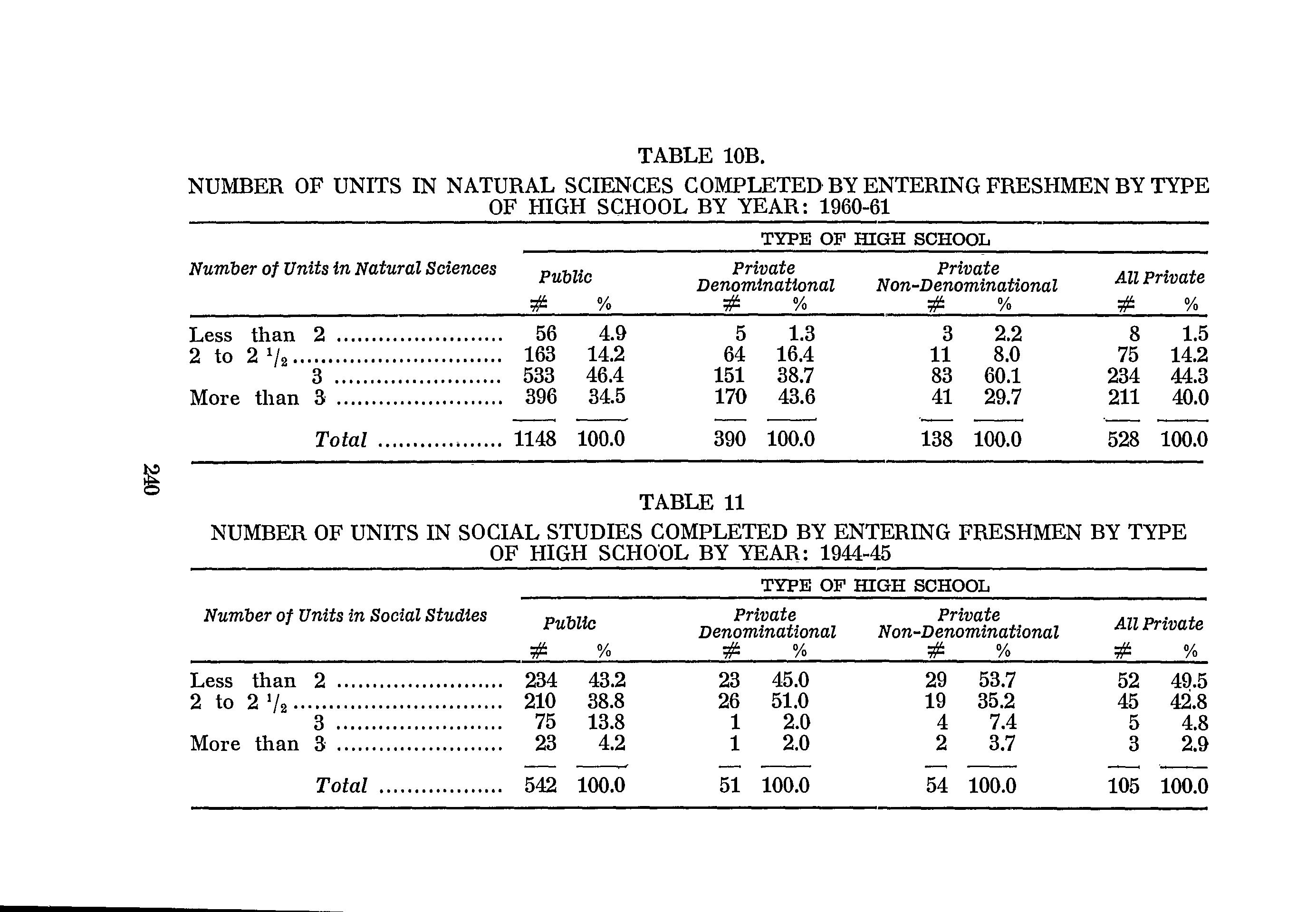

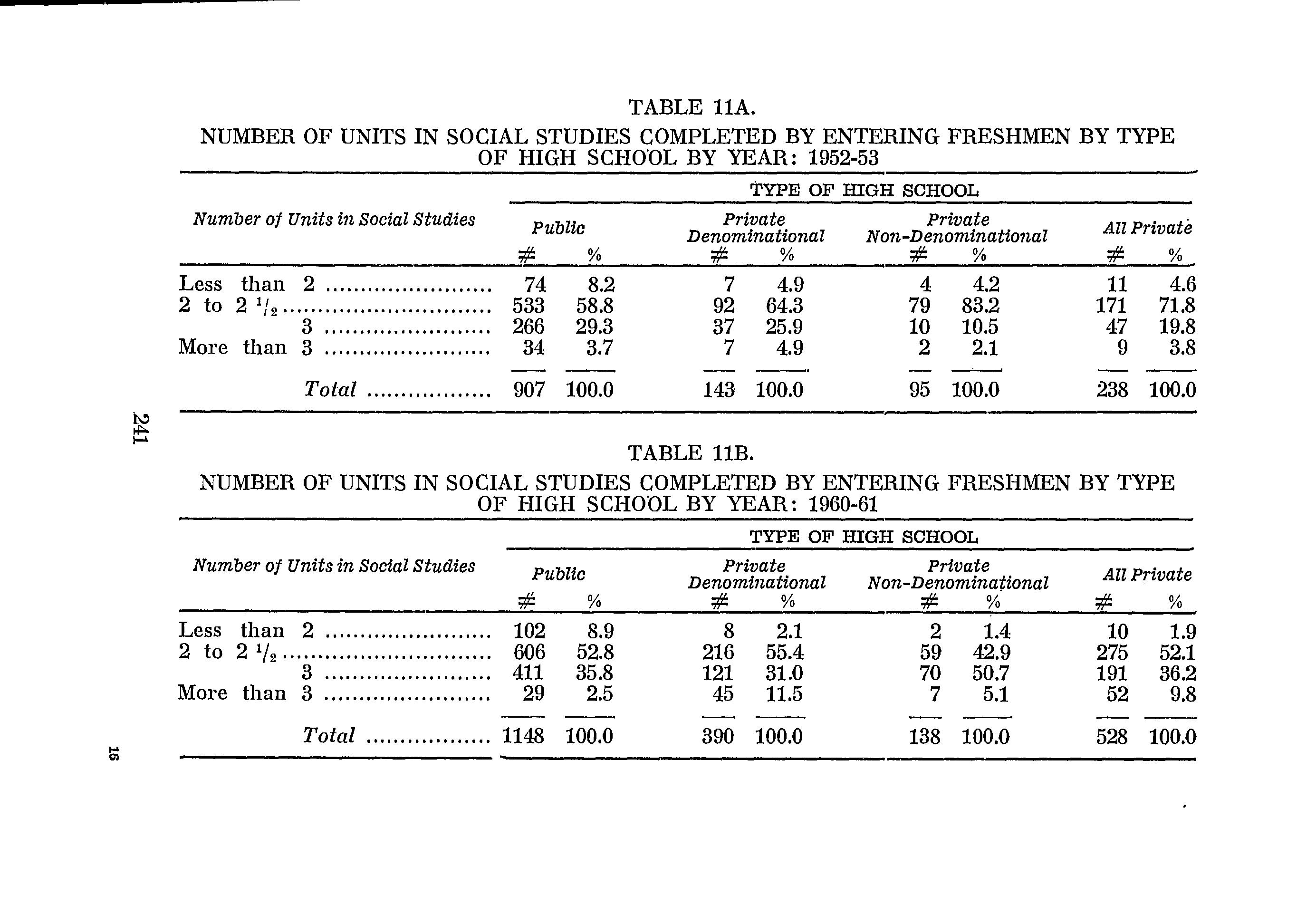

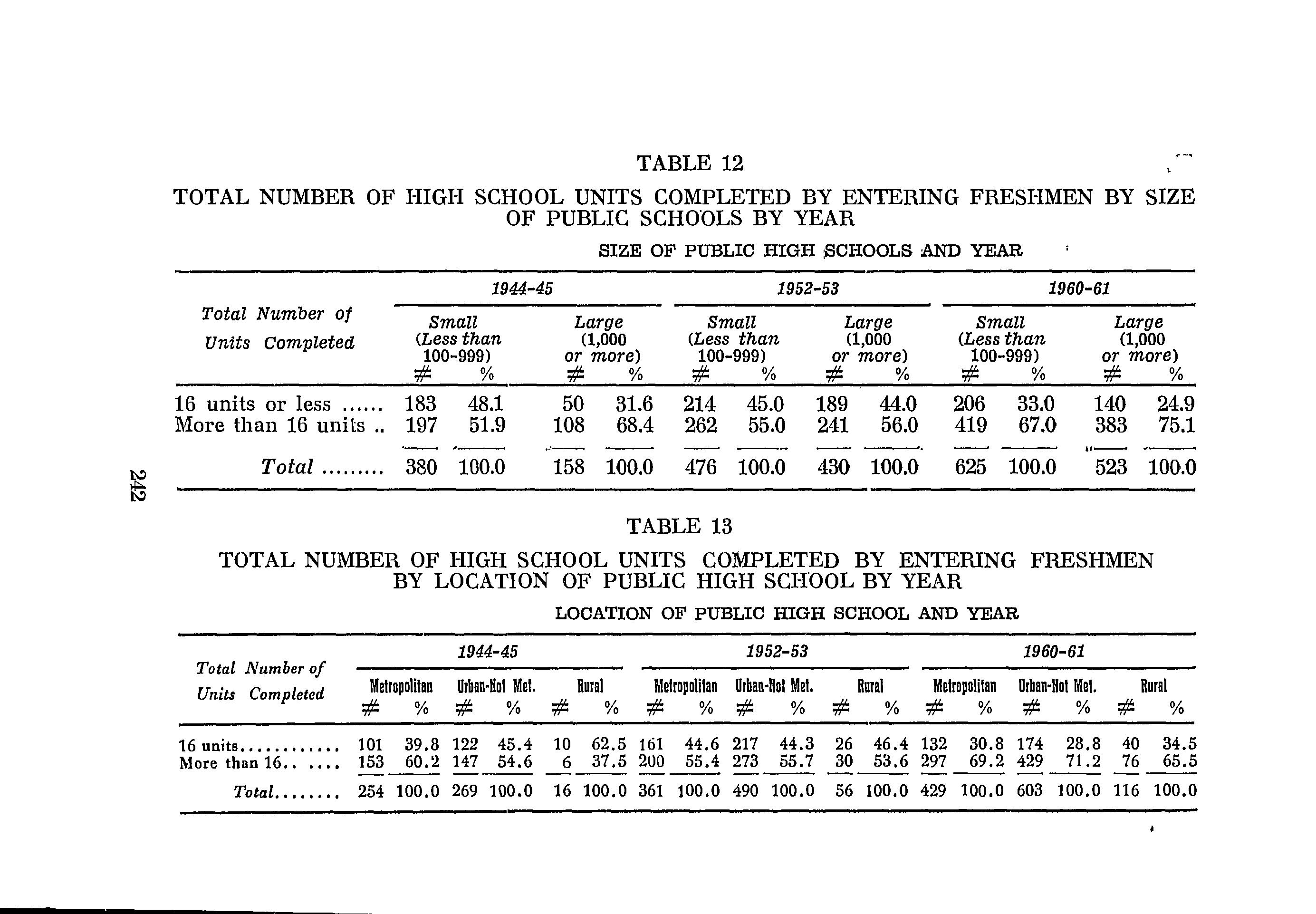

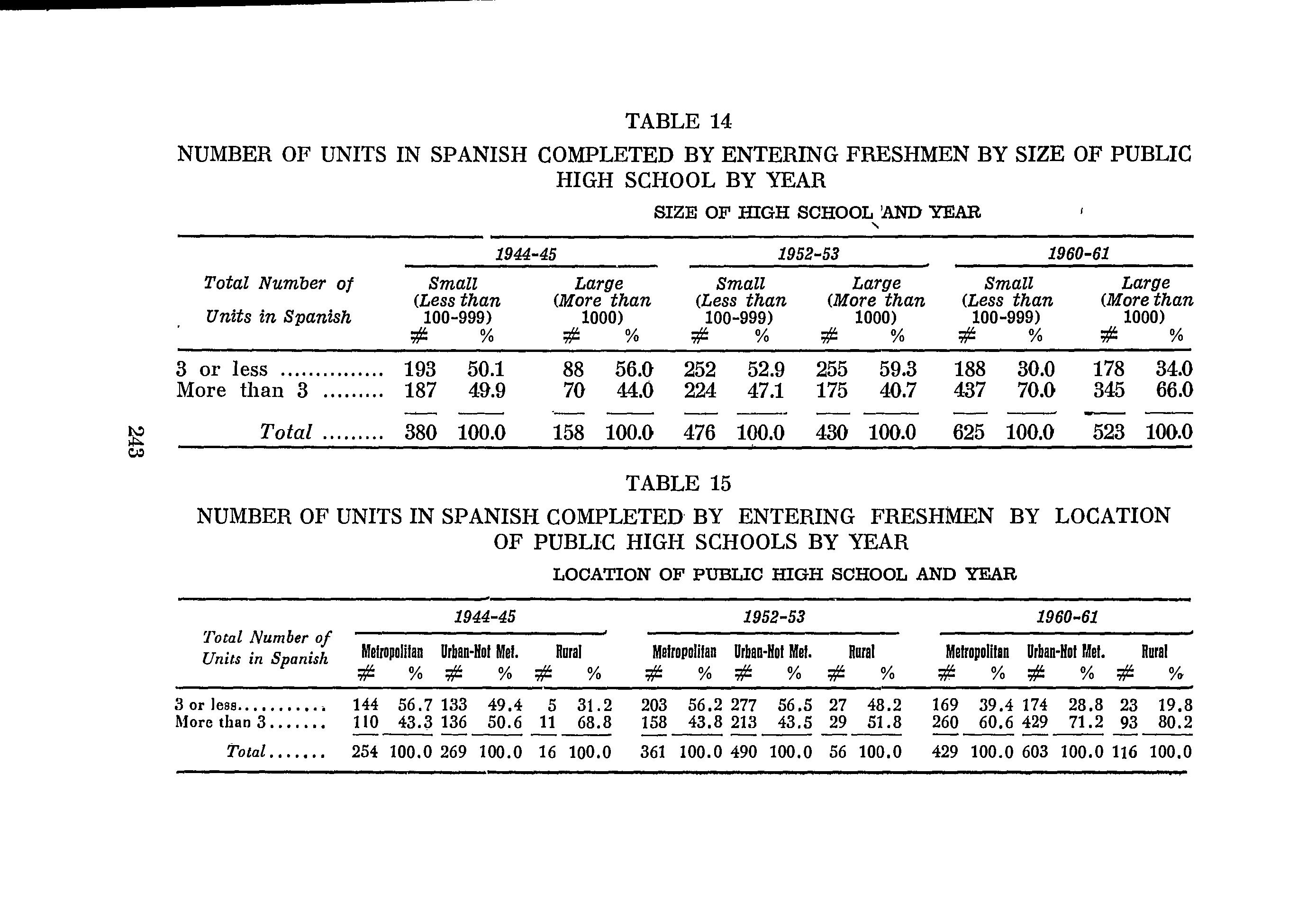

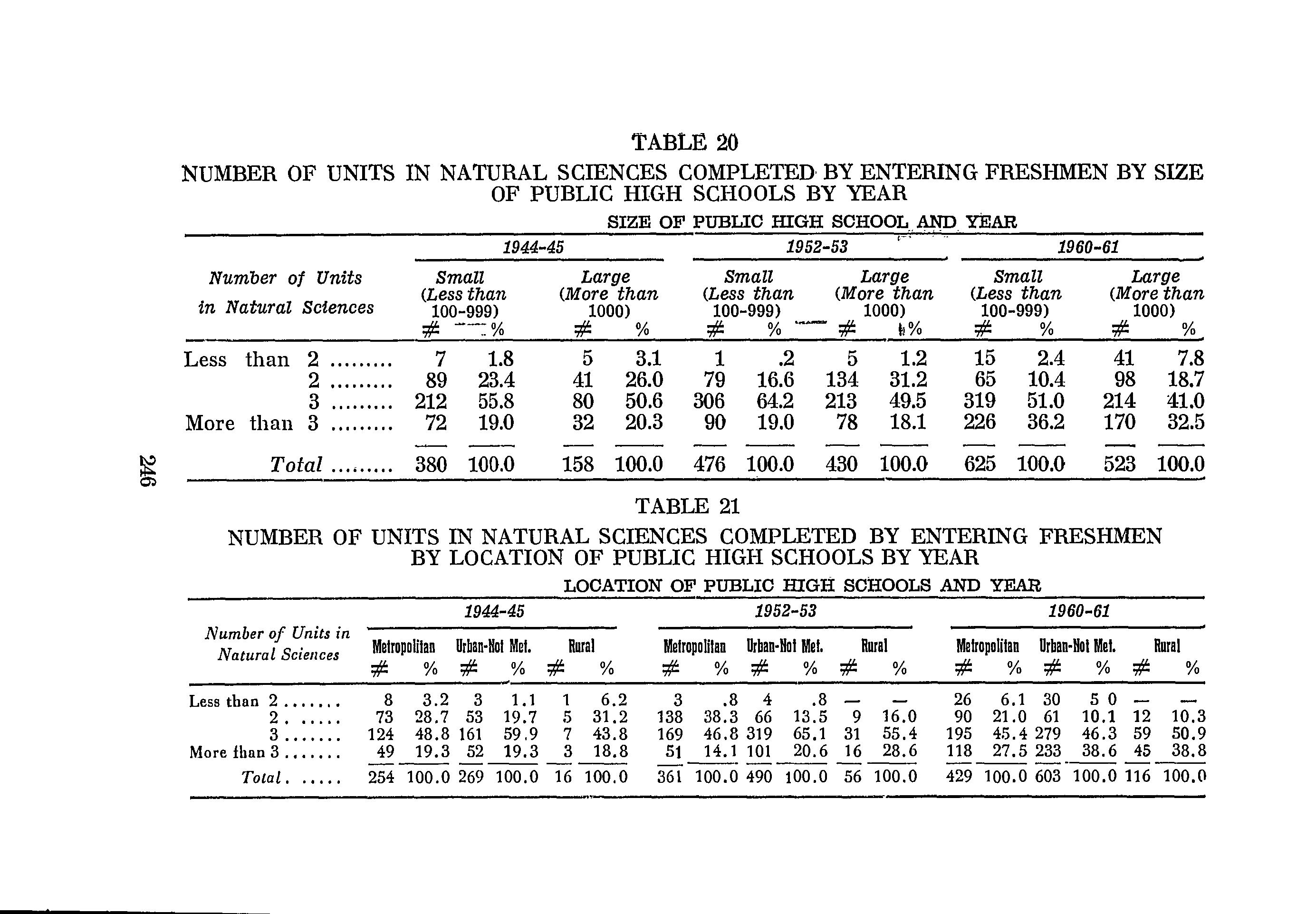

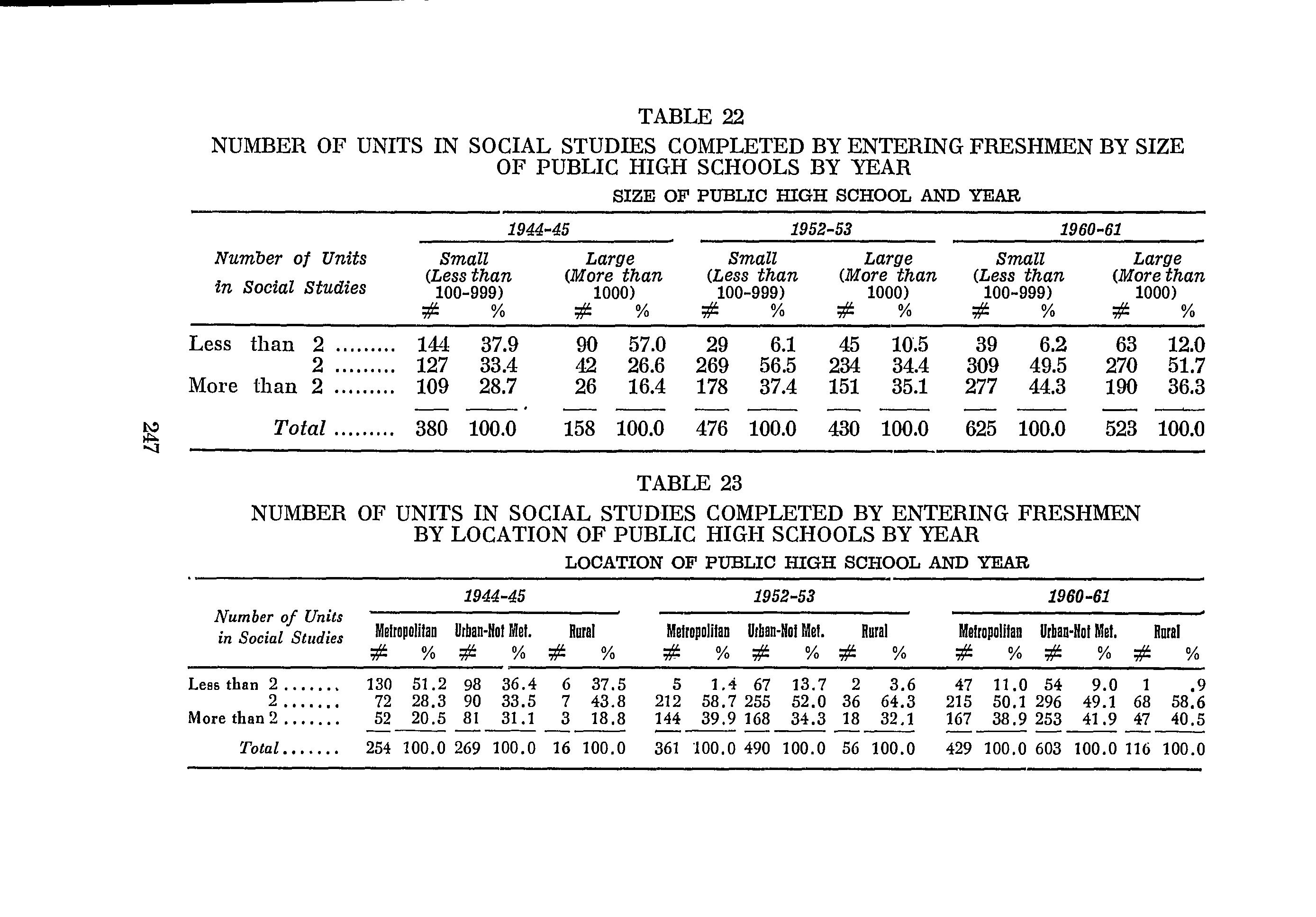

ItisacommonplacethatinPuertoRicothestateuniversity hasalwayshadmoreapplicantsthanitcanadmit.Everyyear aconsiderablenumberareturneddownduetolackoffacilities. Itissignificanttoknownotonlythesocialcharacteristicsofthose admitted,butalsotheiracademiccharacteristics.Thestudywill thusbeconcernedwiththeacademicpreparationofthestudents enteringthefreshmanyear.HowmanyyearsofSpanish,English, mathematics,science,andsocialstudiesdidtheyhaveintheir highschool?Hasthisbasicpreparationdiminishedorincreased?

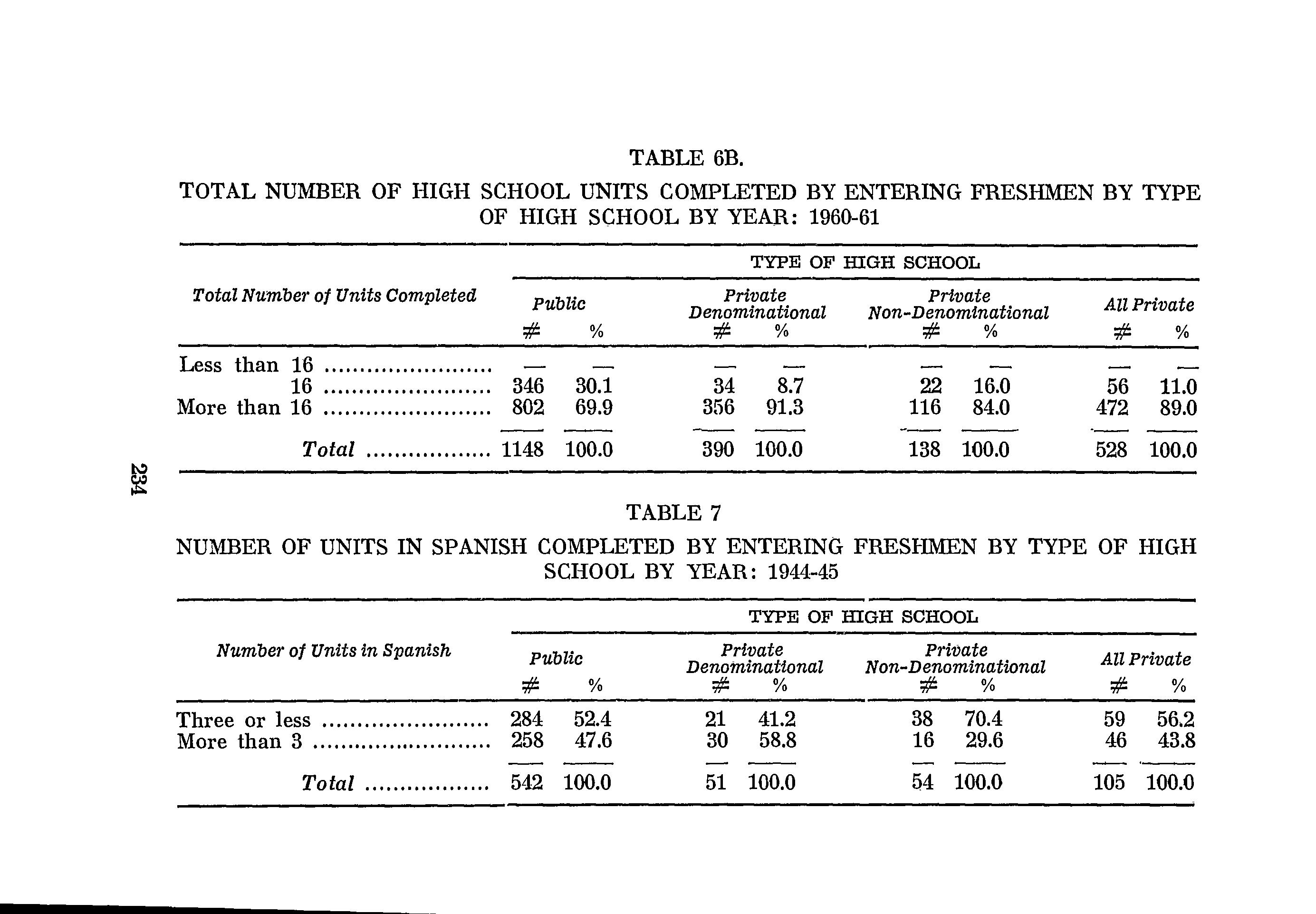

Duringtheearlypartoftheperiodcoveredbythisresearch, theUniversityhadspecificsubjectrequirementsforadmission. However,theseweresubsequentlywaivedin1954;sincethenonly ahighschooldiplomahasbeenrequiredofapplicantswhohave tocomplyonlywiththesubjectrequirementsforhighschoolgraduation.Whateffects,ifany,didthischangeinpolicyhaveon thepreparationofstudentsadmittedintotheUniversity?Ispreparationrelatedtotypeofhighschoolsattended?Isthereany differencebetweenthosefromprivateandpublicschools?Among thosefromschools located in rural,urban, and metropolitan areas?Amongthosefromdifferingsocio-economicstatus?

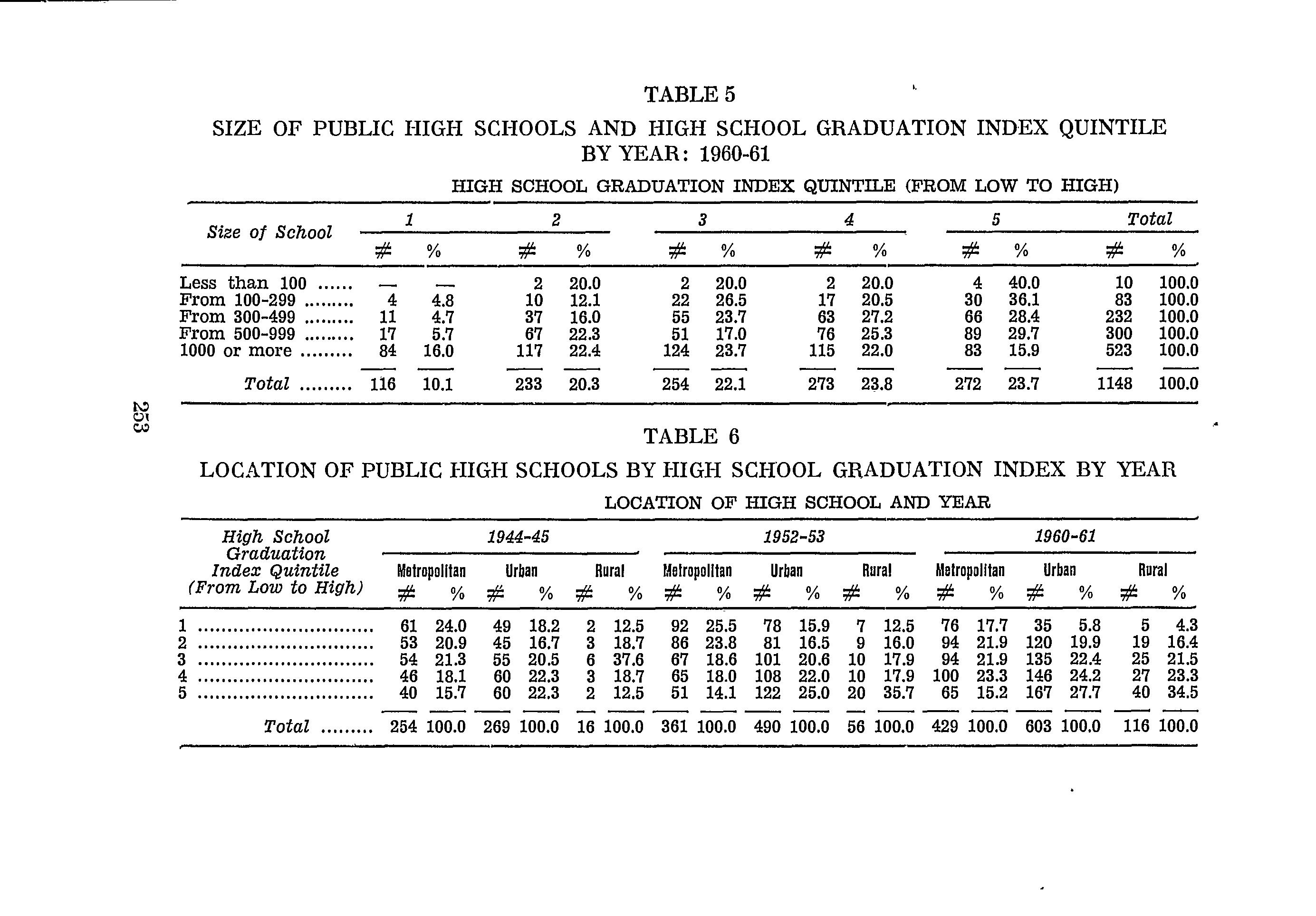

Amongsttheacademiccharacteristicsrelevantinthisstudy aretheperformanceindices.Theseincludethehighschoolgraduationindex(orthenumericalaverageofthegradesobtained inallsubjectstakeninthehighschool),theentranceexamination score(ortherawscoreobtainedinthecompetitiveexamination whichisgivenaspartoftheadmissionrequirementsatthestate university),thefreshmanindex(orthenumericalaverageofall gradesobtainedduringthefirstyearofuniversitystudies),and theuniversitygraduationindex(orthenumericalaverageofthe gradesinallcoursestakenattheUniversity).Occupationalstatus, sex,ruralorurbanbackgrounds,type,size,andlocationofhigh schoolwillbeexaminedinrelationtotheseindicesofachievement.Thefollowingareourguidingquestions:Howdoessocial originrelatetoachievementamongthestudentsinthestudy?

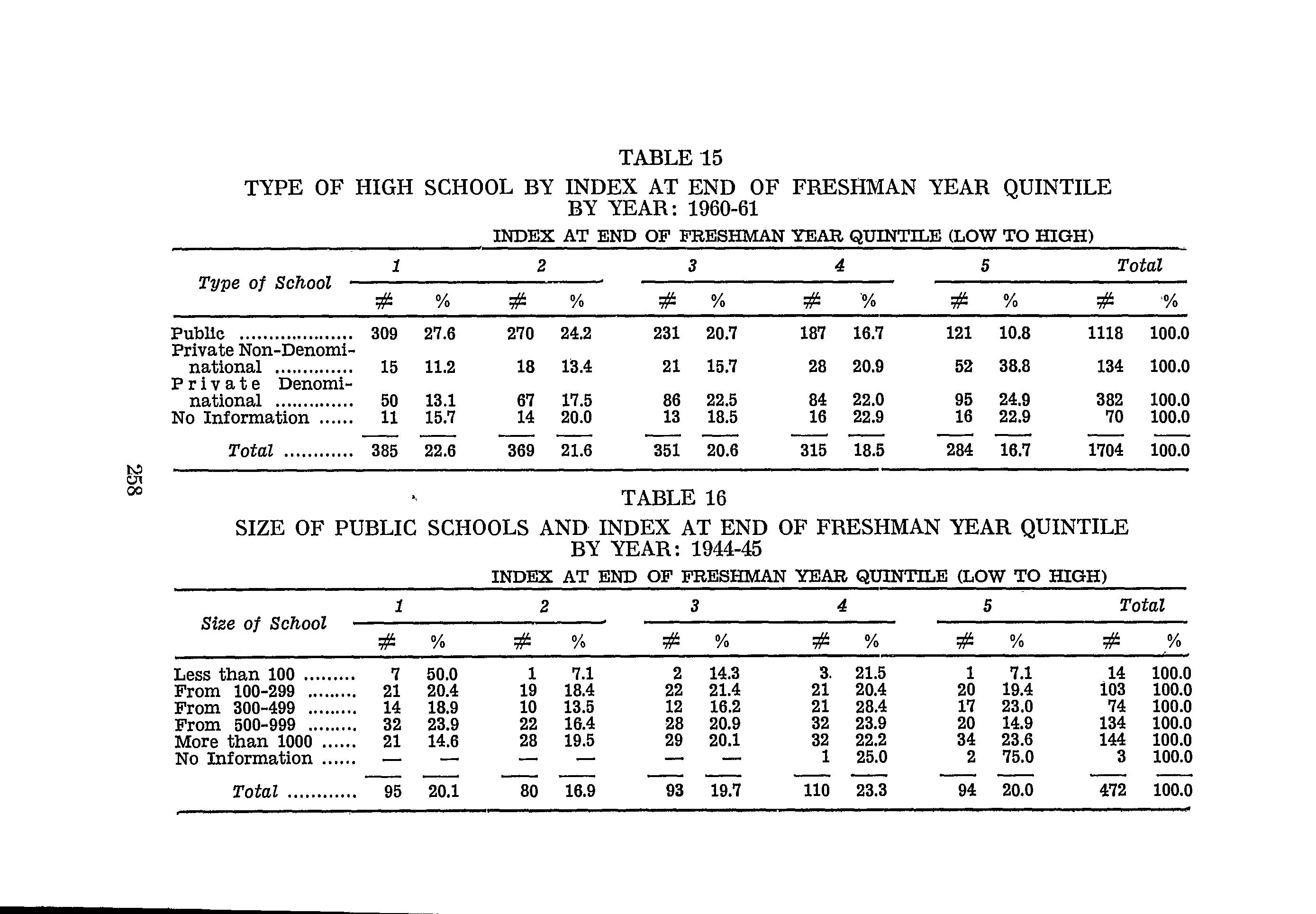

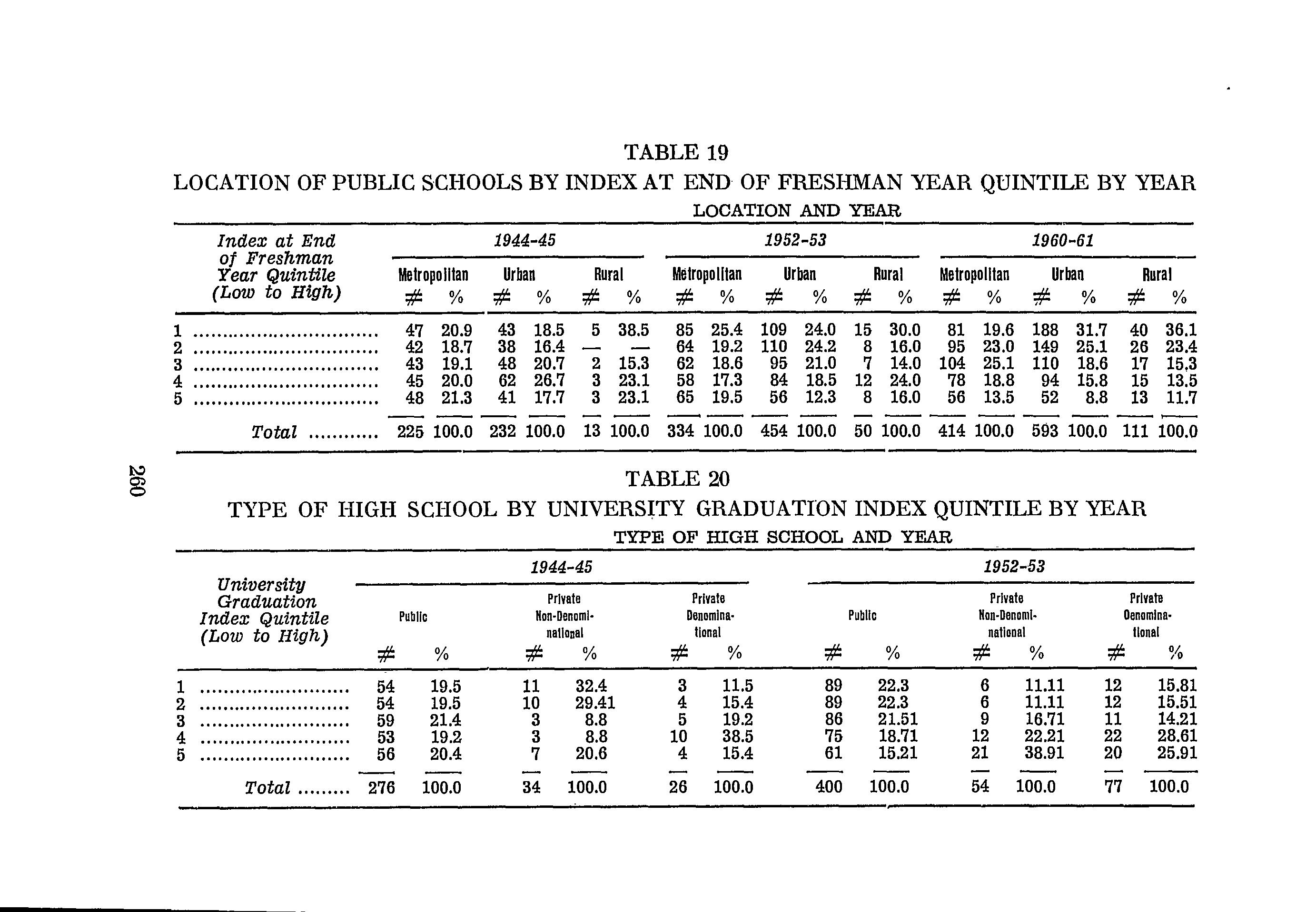

Doprivateschoolstudentsperformbetterthanthosefromthe publicschools?Whatarethecharacteristicsofpublicschoolstudentswhoseperformanceishigh?Dotheycomefromlargeor smallschools?Fromrural,urban,or metropolitanschools?Is thereanyrelationshipbetweenhighschoolpreparationanduniversityperformance?Whatarethecharacteristicsofstudentswho drop out? Of those who take more than fouryears tofinish aBachelor'sDegree?Hastherebeenanychangeduringtheperiod1940-60?

Alsoofinterestinthisstudyarethecharacteristicsofthe studentswhogointothevariousexistingcollegesintheUniversity,sincethosewillbearonthequalitiesofthedifferentprofessionalgroupsreceivingtrainingintheinstitutionwhichsupplies thebulkof civilservants andprivate enterprisemanagement personnel.

TheUniversityofPuertoRicoconsistsofacollegeofGeneral Studies,wherethestudentsspendthefreshmanyearandpart ofthesophomoreyear,andfiveothercollegesinwhichtheycompletetheprescribedfour-yearcurriculumleadingtothebachelor'sdegree.Inthecollegeof GeneralStudies,thestudentsgo throughageneraleducationprogram,afterwhichtheymoveto thecollegesoftheirownchoicetospecializeaccordingtothe areasofinterest.ThesearethecollegesofHumanities,Natural Sciences,SocialSciences,BusinessAdministration,Pedagogyand Pharmacy.

Weshalltrytofindtheanswerstothefollowingquestionsin ouranalysisofthecompositionofthestudentbodyofthevarious colleges.Whatarethecharacteristicsofthestudentswhogointo eachcollege?Arethereanydifferencesinsocialcompositionbetweenthecolleges?Inhighschoolpreparationoftheirstudents? Doesstudentperformancevaryfromonecollegetoanother?These questionsalsobearontherecruitmentpatternoftheprofessions intheisland.

Theperiodwithwhichweareconcernedinthisstudyisthat between1940and1960.Thisperiodwaschosenfortworeasons. First,in1940,thePopularDemocraticPartycametopower.Its platformhasstressedsocialandeconomicreformswhosepractical applicationhashadastronginfluenceinstimulatingtherateof socialchangethattheislandisundergoing.Duringthisperiod, anewadministrationtookoverintheUniversitywhichentered onaperiodofrapidexpansionalsonoticedatallothereduca-

tionallevels.Secondly,documentsandrecordsaremorereadily availableforthisperiodthanforanyother.

TnPuertoRicotherearethreeprivateuniversities(theCatholicUniversityinPonce,theInteramericanUniversityinSan Germán,andtheSacredHeartCollegeforWomeninSanturce), onejuniorcollege(PuertoRicoJuniorCollegeinRioPiedras),and thestateuniversity(UniversityofPuertoRico).Thelastonehas threemaincampuses.Thesubjectofourstudyconsistsofallthe studentsmatriculatedinthebachelor'sprogramattheRioPiedrascampusoftheUniversityofPuertoRicofortheacademic years1944-45,1952-53,and1960-61.TheSanJuancampus,where graduateworkinmedicineanddentistryiscarriedout,wasnot included,northecampusofMayagüezwhichincludesmainlythe engineeringandagriculturalartsprogram.

TheUniversityofPuertoRicowaschosenbecauseitisapublicinstitutioninwhich equalityof opportunityisan official objective.Theavailabilityofmaterialstherealsoinfluencedour choice.Lastly,thelimitedfacilitiesatourdisposalconfineusto onlyoneinstitution,andtothemostaccessibleone.TheRioPiedrasCampuswasselectedbecauseithasthelargestundergraduate enrolmentintheentireinstitution.

The presentation of thestudy will consist of four parts. Thefirstdealswithtrendsinthelowerlevelsoftheeducational systeminPuertoRicoduringtheperiodselectedforthisresearch. Thisisfollowedbyanhistoricalaccountof theUniversityof PuertoRico.Thesecondpartisasurveyoftrendsinthesocial andacademiccharacteristicsofcollegestudentsasrepresented bythefreshmanbody.Partthreeundertakesafurthercorrelationoffactorsandvariablestoilluminateorconfirmthepoints madeinprevioussections,againwithspecialreferencetohistoricaltrendsinthe"quality"offreshmanstudents.Onabroader planeitseekstolocateclassinfluenceswhichmightbeoperating inthesystem,particularlyinthelightofmeasuredacademicperformance.Acentralpointofinterestistherelationshipbetween highschoolgradesandtheacademicindicesusedintheUniversity.Thus,thewholeproblemofperformancewillbeplaced withintheperspectiveofsocio-economicstatus,schoolcharacteristics,andsecondarypreparation.Thelast partof thiswork recapitulates the majorfindings on social and academic characteristicsbyrelatingthemtothevariousundergraduatecolleges intheUniversity.Finally,thereisasectionembodyingcertain

broadgeneralizationsandpersonalcommentsbytheauthorrelativetothemainfindingsoftheentirestudy.

ThesectionsoneducationaltrendsandtheUniversityof PuertoRicorepresentanefforttoappraisethefundamental changesundergonebyasystemwhosephilosophyhasostensibly shiftedfromoneofcateringtoanélitetoanotherofproviding masseducation.Thedataforthesetwochapterswerecollected bytheauthorfromthevoluminousfilesoftheDepartmentof EducationandtheUniversityofPuertoRico.Theworkinvolved ascrutinyofreportsandmanuscripts,someofwhichwereconfidential.Fromthissearchithasbeenpossibletopiecetogether scatteredinformationabouttheschoolsystemandtopresent forthefirsttimeanoverallpictureofthelasttwodecades.The purposeofthetwochaptersisnotonlytocollectandsynthesize existingdatabuttogivethemasociologicalmeaning.Further availableinformationwasusedtoplacetheminacross-cultural frameofreference,whilesupplementarymaterialswerereconstructedfromprintedsourcesandprivateconversationswith UniversityteachersandpersonnelofthecentralofficeoftheDepartmentofEducation.

Theprincipalsourceofinformationforthesecondpart,on trendsinthesocialandacademiccharacteristicsofcollegestudents,istheRegistrar'sOfficeoftheUniversityofPuertoRico. Thedocumentsmainlydrawnuponaretheindividualapplicationsforadmissionandtheacademicrecords.ConfidentialdocumentsfromtheScholarshipandVeteran'sDivisionswerealso examined.

Thissecondphaseofthestudystartedwithasurveyof existingrecordsfrom1940to1964withtheobjectofdetermining theacademicyearsforwhichinformationwasmorecomplete. Weproceededbystudyingthehundredthcaseineveryyear.The wholeprocedureprovedlaboriousandtime-consumingowingto thevarietyofapplicationformsusedfromyeartoyearandthe consequentvarietyofinformationfoundinthem.Forsomeofthe years,differentapplicationblanksweredistributedsimultaneously.Theoutcomeofthesearchisthechoiceofthethreeacademicyears1944-45,1952-53,and1960-61ashavingrelatively completerecordsforthetypeofinformationdesired.Moreover, thespanoftimeallowsanhistoricaltrendanalysisofthefindings. Actualgatheringofdatahadtowaitfurtherandcouldnotbe starteduntilafterthefreshmanstudentshadbeenseparated fromalltheothers(sophomores,juniors,seniors,graduates,two-

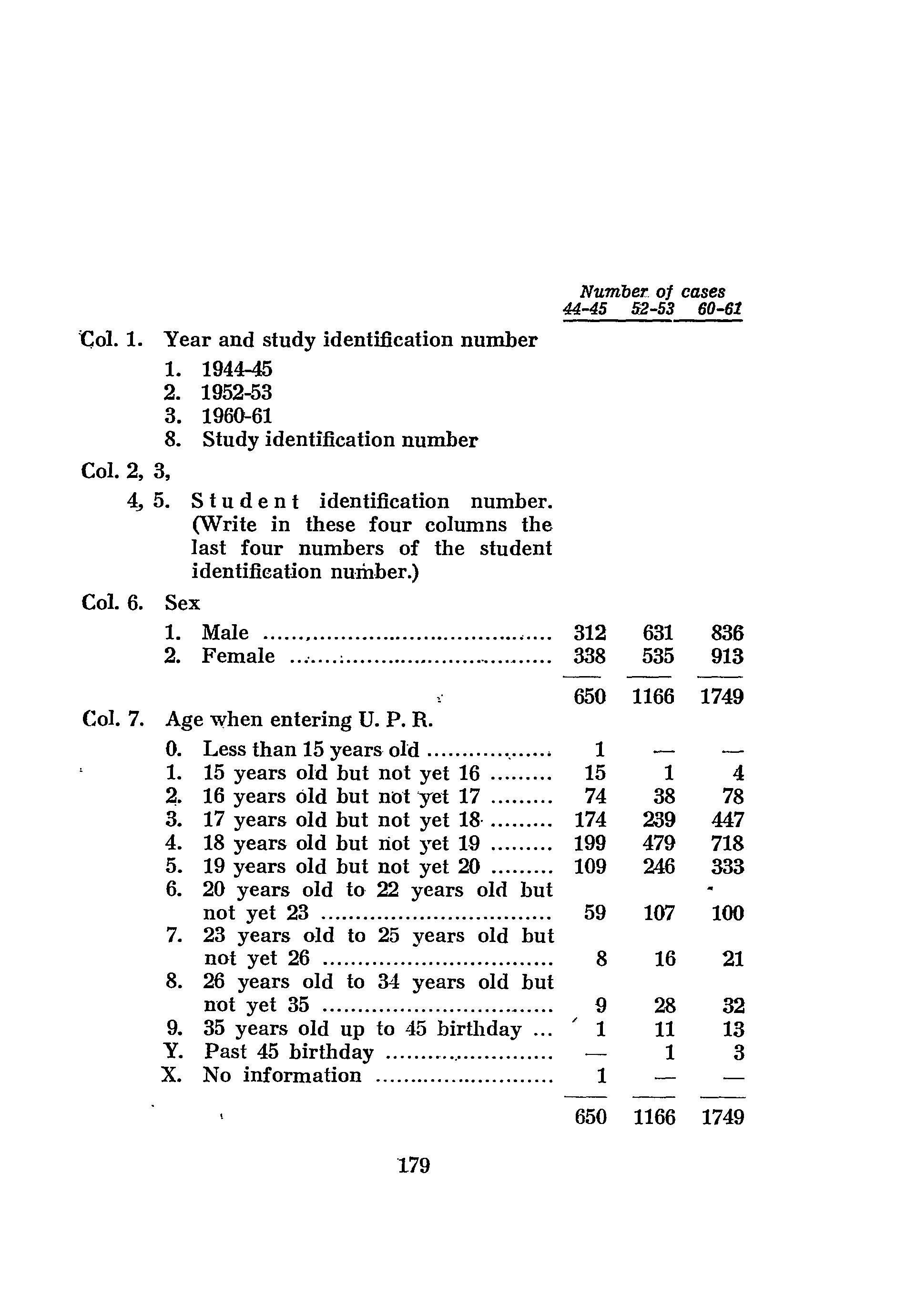

yearstudents,extra-mural,irregular,andvisitors) 1. Theentire freshmanclasseswhichprovidethesubjectofthisstudynumbered650in1944-45,1,166in1952-53,and1,749in1960-61.

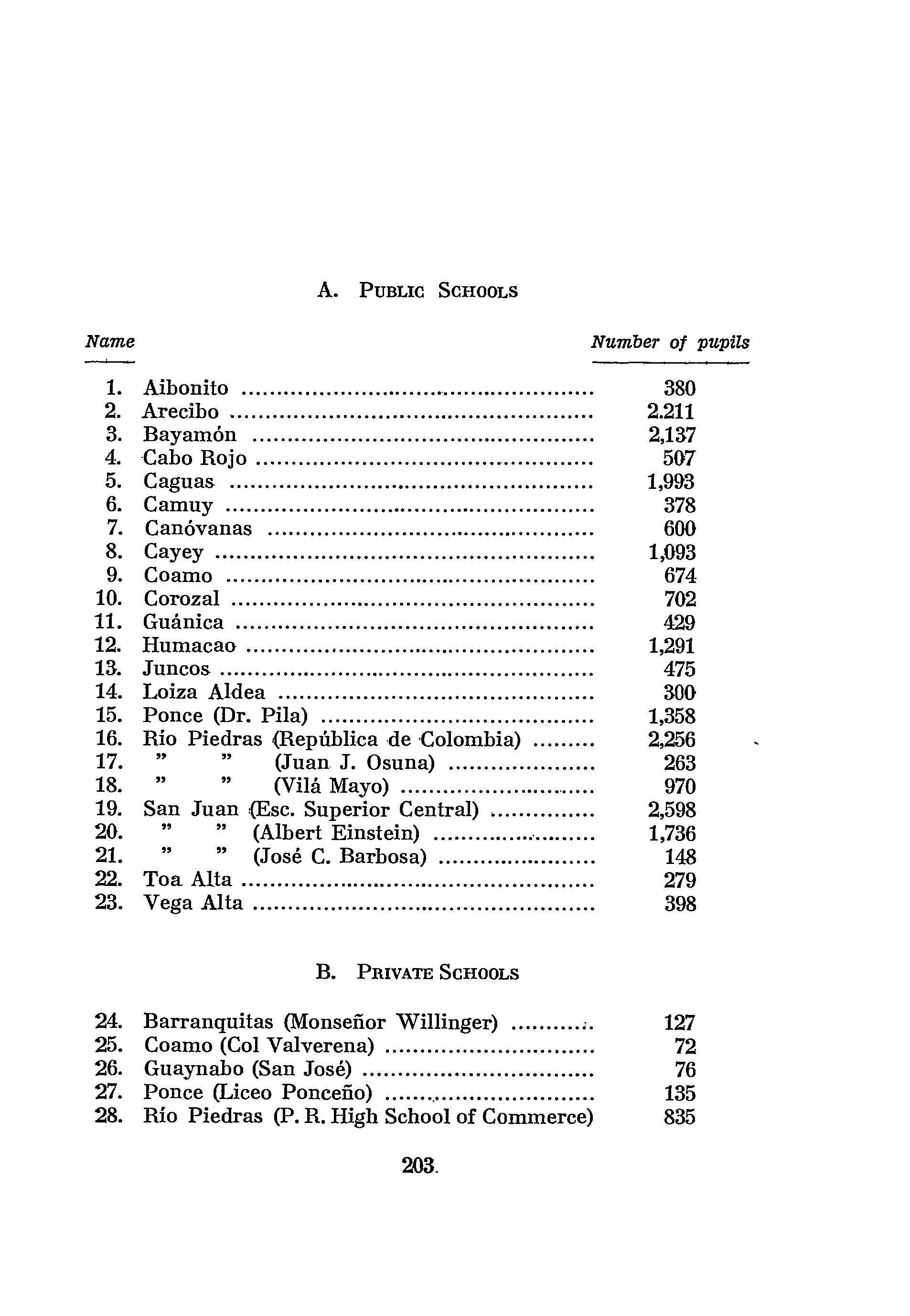

Thedatacollected.fromtheRegistrar'sOfficeweresupplementedbyotherformsofinquiry.First,aninformationsheet wasdistributedamongstthefreshmanstudentsofthe1960class toobtaintheirfathers'occupations.Thissheetwasfilledinby freshmenintheirvariousclasssectionsunderthesupervision oftheauthorandhistwoassistants.Topreventduplication,only theSpanishsectionswerevisited.Secondly,anindividualfollowúpwasdoneforallcasesabsentfromclassonthedaytheinformationsheetwasdistributed.Thirdly,casesforwhominformationonfather'soccupationwasstillmissingwithrespect tothethreeacademicyearsselectedforinvestigationweretraced tothehighschoolsfromwhichtheygraduatedsoastoreduce toaminimumtheno-informationcases.Thiswasdonebycorrespondenceorpersonally,thesourceschieflyrelieduponbeing thestudents'cumulativerecordsandthevocationalcounsellor's fileskeptinthevarioushighschoolsoftheisland.Fourthly,data onthesocialcompositionofhighschoolseniorswereobtained throughapaper-and-pencilquestionnairewhichwasadministered originallytoarepresentativesampleofhighschoolseniorsin theislandforanotherstudybeingundertakenintheSocial ScienceResearchCenteroftheUniversityofPuertoRico.Asto thedatathuscollectedforthisstudy,theauthorundertookthe administering,coding,machineoperationsandanalysis.Lastly, visitsweremadepersonallybythewriterto35publicandprivate highschoolsscatteredovertheisland.

Thevisitslastedforaminimumperiodofoneschoolday ineachschool.Thechiefobjectofthesevisitswastoassess

1. Datawerecodedbyresearchassistantswhoreceivedatwo-week intensivetrainingonthevariousphases of coding.Threemethodswere establishedtoinsurecodingreliability.First,alltheresearchassistants codedthefirstonehundredcasesanddiscussedthem.Secondly,every tenthcase of thosewhicheachresearchassistanthadcodedwasalso codedindependentlybytheauthorsothatdisagreementscouldberesolved whencaseswerecompared.Thirdly,,everytwentiethcase,codedbyeach researchassistantwasinturncodedbytheothers.Foreach of these proceduresitwasagreedthatanydoubtemerginginthecodingprocess wouldbebroughttotheattention of allthecoders. By discussingand counterchecking,discrepanciesincodingwerereducedtoaminimum. Thecodingerrorwas 0.2%.

existingconditionsandtosoundoutteachersandotherpersonnel actuallyinthesystem.Thesetalksdidnotfollowastructured interviewpattern,butwereratherinformal,allowingscopefor teachers and principals to pose their own queries concerning workingconditionsintheirparticularschools,especiallyasregardsfacilities.Theschoolsvisitedwereselectedfromsmalland largepublicschools,urbanandrural,anddenominationaland non-denominationalprivateschools.Theirsizesvaryfromunder 100toover2,000pupils.Someofthebuildingsarenew,others decrepit.Someareprovidedwithmodernfacilities,otherswith thebarestminimum.Someareofrecentorigin,othersoflong standinginthecommunity.Aschoolvisitincludedatalkwith theprincipalandalsowiththeteachers(from1to10ofthem), andatouraroundtheschoolpremises.

Thesecondpartofthisstudyistheresultof thefirstinvestigationsofarundertakenintosocialselectionattheuniversitylevelinPuertoRico,intothechangesinthisselectiveprocess overthetwodecadescoveredbythestudy,andtherelationship ofthisprocesswiththatinthelowerschoollevels.Italsogives forthefirsttimetheacademicbackgroundoffreshmanstudents whoentertheUniversity,thevariationduringthetwenty-year period,andtheconnectionwithsociologicalfactors.Asinthe previoussection,cross-culturaldatawerebroughtintothepicture whenevertheywerecomparabletoourowndata.

Thedataforpartthree,onacademicperformance,werealso constructed from information collected from the Registrar's recordsfor individualstudents.With these data, it has been possibletomakeforthefirsttimeanappraisalofthesocialrelevanceoftheacademicindicesappliedinthehighschoolsandin theUniversity.Previousresearch undertaken by theSuperior EducationalCouncilontwowidelyseparatedyearswithinour period,although excludingsocialconsiderations,permitsusto drawcomparisonswithsomeofourfindings.Supplementarydata forthispartofthestudywereobtainedfromofficialpublications and participantobservation.Thelatterwas conducted bythe authorwhileofferingatwo-semestercourse,duringtheacademic year1960-61, to freshmen in the College of General Studies, meetingthreehoursaweek.Thisphaseoftheinquirygavethe writersomeinsight intothebureaucraticstructurewithin the Universitywithrespecttostudentgrading.

Thelast part of thisstudy,which dealswith curriculum choiceandperformancebycollegeinthestateuniversity,isalso

basedondatacollectedfromindividualrecordsfiledintheRegistrar'sOffice.Itmakesaninitialefforttodefinethedistributionofsocialclassesandmeasuredabilityamongstthevarious colleges.Itssignificanceliesinthe evidenceof arelationship betweencollegecharacteristicsandrecruitmentintotheprofessionsandparticularlyasregardstherecruitmentoftheteaching profession.

Thisstudyformspartofamoreextensiveresearchonthe socialconsequencesoftheschoolsinPuertoRico,undertakenat theSocialScienceResearchCenterofthestateuniversity.The researchprojectasawholeisrelatedtotheprogrammeoneducationalsociologybeingdevelopedatthatCenter.Astothisstudy, thewholephaseofdatacollectionandmachineoperationslasted foraperiodoftwoandahalfyearsandwasundertakeneither bythewriterhimselfaloneorunderhisdirectsupervision.

Theperiod1940-1960sawthedistillationofideaswhichhad beeninfermentforalongtimeinthePuertoRicanconsciousness, accompaniedbytheemergenceofadistinctpolitico-economicand educationalstructure.Therewasatfirstanavowedwithdrawal fromanydefinitivedeterminationofthepoliticalstatusofthe island,andontheheelsofthisoutwardlynon-committalposition evolved thepolitico-psychological compromisecalled the CommonwealthofPuertoRico.Itreflectstheconscienceofapeople unwillingtomakeanyspecificpoliticalcommitmentwhichmight prejudicethe"vestedinterests",butanxioustohavetheirpositionappearasrespectableaspossibleintheeyesoftheLatinAmericanrepublicswhichhadbeenopenly,veryoftenscathingly, criticaloftheisland's"indifferent"politicalsituation.TheCommonwealthstatus,asrecognizedbytheUnitedNations,isanoncolonial one; and by extending the scope of self-government withoutstrainingthefederaltiewiththemainland,ithadperformedtheusefulserviceofcoolingoffhotheadsoverthequestion ofindependenceversusstatehood.Itsstayinginfluence,however, seemstobewearingoff,asdemonstratedbytherecentoutbursts fromdissatisfiedcamps.The"Independentistas"arereorganizing, whilethe"Nacionalistas"areagainpreachinghell-fire.The"Estadistas",ontheotherhand,areencouragedbytheannexation ofAlaskaandHawaiitotheUnitedStates,whichtheoretically removedtheobstaclesof non-adjacencyanddifferingcultural backgroundsfromthepathtostatehood.Meanwhile,thePopular DemocraticPartyishardputtopreserveitsunityamidstthe

demandsfromwithinitsownhouseformoreautonomyinlocal andforeignmatters1.

Asfarassettingupeducationalgoalsisconcerned,the presentstatushasbeeninveighedagainstasbeingadeterrent. Itisbelievedbysegmentsoftheintelligentsiathatthelackofa well-definedpoliticalobjectivepreventsthedevelopmentofan educationalsystemgearedtothesocio-economicrealitiesand needsoftheisland.ItisheldfurtherthattheCommonwealth perpetuatesacolonialphilosophyoflifebyfosteringthefeeling ofpoliticalandeconomicinsecuritycharacteristicofearlier periods.

Ontheeconomicside,theperiodhasbeencharacterizedby asystematicefforttodiversifytheisland'sagriculturalsubsistence economyonascientificlevel,topromoteindustrialization,encouragefamilyplanningandeffectamoreequitabledistribution ofwealth.Theseeconomicaimsaretobecarriedoutthrough thelegalrestrictionofland-holdingto500acres,theexpropriation offoreignlatifundia,resettlementoffarmers,statecontrolof basicpublicservices,stateinitiativeinindustrialenterprises,and anall-out"OperationBoot-strap",asthelarge-scaleindustrializationschemeiscalled.

Toassistinthisneweconomicorientation,educationhas beencalledupontoperformspecifictasks.Theseareoutlined byHarveyS.Perloff,andhavebeenincorporatedbysuccessive secretariesofeducationintheirrespectiveprogrammes.Theyare thefollowing:

"1.Tohelpdeveloptheeconomic,social,andpsychological factorsthatconducetoanindustrialclimate.

2.Totrainskilledworkersforthenewlyestablishedindustries.

3.Toexpandfacilitiesamongsttheschoolagepopulation,

1. InPuerto Rico therearethreeofficialparties:the"Independentistas"whoaspiretoachievepoliticalindependencethroughtheexisting electoralprocess,the"Estadistas"whoseultimateaimistheannexationof theislandasastateoftheNorthAmericanunion,andthePopularDemocraticParty,supporterofthepresentstatusofCommonwealth.Other politicalorganizationswhichdonotenjoylegalstatusarethe"Nacionalistas",whoaspiretoachieveindependencebyarmedrebellionandforce, theCommunistPartyandaCatholicPartyofrecentorganization.

therebytoraisetheeducationallevelandimprovethe potentialresourcesfortherecruitmentofworkers, technicians,andindustrialmanagers.

4.Tohelpfostertheimprovementofagriculture,industry, andothersourcesofproduction,andtheconservation andsoundexploitationofnaturalresources.

5.Todevelopaproperunderstandingofthepsychological changes—changesincustoms,beliefs,habitsandways oflife—whicharethenecessaryconcomitantsofindustrialization,withaviewtoreducetoaminimum conflictsandmaladjustments" Z

Aswecansee,thetaskssetupfortheschoolsysteminvolve psychologicalorientationtoaneo-industrialsociety,withlittle regardtotheeconomicrealitiesintheislandandthecultural needsofitspeople.Ineducation,themostpalpableoftheserealitiesisarateofgrowthoftheschoolpopulationcontinuously outstrippingavailablefacilities.Moreover,theresponsibilityfor thenewsocialorderisplacedsquarelyononesingleinstitution whichitselfhasyettoachievesufficientfreedomtotaketherequiredinitiative.TheSecretaryofEducationisresponsibletothe partyinpower,ordirectlytothegovernorwhoappointshim, ratherthandirectlytotheelectorate.Inotherwords,wheretheinterestofthepartymightbeinconflictwiththatofthepeople,the SecretaryofEducationisboundtofollowthepartyline.This situationdiffersfromthatofthelateSpanishandearlyAmericanperiodduringwhichelectedmunicipalschoolboards,in chargeofeducationalfinances,servedasacheckonthecentral authority.Italsodiffersfromexistingconditionsinmostofthe UnitedStates,wheretheBoardsofEducationareelectedand togetherwithcertaincivicorganizationsinfluenceeducational decisions.WiththeconsolidationofAmericanpoliticalrulein PuertoRico,localparticipationineducationalmatterswasabolishedandeducationalauthorityconcentratedinaSecretaryof Education,whowasapoliticalappointeeoftheUnitedStates Presidentandvestedwithextraordinarypowersoverbothpublic andprivateschools.Thelegalstructurehasremainedunchanged, andtheSecretaryofEducation,whoisnowresponsibletothe

2.AnnualReportoftheSecretaryofEducation;1952-53,p.56-57.

Governoroftheislandandthepoliticalpartyinpower,enjoys thesamepowersashispredecessors.

Thattheinterestsofthepartyandthecommunityneednot coincidewasshownin1957,whenthenewlyappointedSecretary ofEducationorganizedapublicevaluationoftheschoolsystem. Atthesametimehegavethetop-leveleducatorstounderstand thatthefindingsofthatenquirywerenottobebindingonthe SecretaryofEducationinanyway.Morerecently,theEducation Commissionoftheisland'sLegislatureorderedanevaluative studyoftheeducationalsystem,andagainitwasexplicitlyindicatedthatthecabinetmemberforeducationwasnottobebound bytheresults.Thissituationismadepossiblebythefactthatthere arenoadequatechannelsofpubliccontrolwhichcanpreventthe legislatorsfrompassinglawscontrarytothenationalinterest orpressthemintopassingfavourableones.Organizedopinionis stillundeveloped;thustherearevirtuallyno"pressuregroups" tobearinfluenceonthegovernment.Infact,thepoliticalsituationintheislandisgearedtothepreservationofthisstateof affairs.

InPuertoRico,electionsareheldeveryfouryears.Allthe politicalpositions,fromthegovernorandresidentcommissioner intheUnitedStatesCongressdowntothemunicipalcouncillors arefilledbythoseelections.Nominationstothesepositionsrest onthepartyleaderwhoisalsoheadofthegovernment.Indeed, aspirantsdependonthepersonalinfluenceofthepartyleaderfor successatthepolls.Thepopulaceidentifythemselvesratherwith theleaderofthepartythanwiththepartyitself;thustheyare "muflocistas",insteadof"populares".Atthepollingboxes,the majorityoftheelectoratehardlymakeuseofthe"splitticket" andmerelycasta"blockvote"forthepartyoftheirleader.Elected officialsthereforefeelthemselvesboundnottotheelectoratebut tothepartyleadertowhomtheyowetheirelection.Between electionstheysubmittostrictpartydiscipline.Deviationistsare likelytolosepartynominationinthenextcampaign,thereby forfeitingtheirchancesofcontinuingapoliticalcareer.Sofar nocandidateshaveeverbeenelectedonanindependentticket inPuertoRico.

Partydisciplineisespeciallyfeltinthenationallegislature; infact,itissostrongthat"itpreventstheLegislativePowerfrom exercisingadequatefiscalizationoftheExecutiveBranch" 3 When

3.Comitédelgobernadorparaelestudiodelosderechosciviles,

conflict ariseswith regard toalegislativemeasure,interested partiesdonotlobbylegislators.Theyprotestpersonallytothe governor,"thesupremesourceofauthority".Intheirimageof him,hecanhavelegislationpassed,stoppedorabrogated,and theyarenotfarfromtheactualtruth.

Inthispoliticalclimate,itisthe"paternalauthority"notthe citizenrywhichdetermineswhatisbestineducationalmatters. Educationalplanningisperforcethechildofpartypolitics,and inthelasttwodecadesithasmainlytakentheformofexpanded educationalfacilities.

Thischapterisconcernedwithtrendsineducationalplanning andorganizationduringtheperiod1940-1960whichbeganwith theaccessiontopowerofthePopularDemocraticParty.Itscampaignplatformpromisedimprovementofsocialconditionsinthe islandandafreshapproachtoeducation.Theeducationalprogrammewasstartedoff bysettlingthelanguageproblem.So farinstructionatalllevelsofeducationhadbeenconductedchiefly inEnglish,withSpanishasasupplementarymedium.Thiswas inaccordwiththeUnitedStatespolicyof"americanization"of theisland.Thenativelegislature,underthecontrolofthePopular Party,nowdecreedthatSpanishwastotakeprecedenceover Englishinallthepublicschools 4 OppositionfromthePresident oftheUnitedStatesandhisappointee,theGovernorofPuerto Rico,sparkedoffaparliamentaryandlegaldebate,theoutcome ofwhichwasanadministrativeresolutionconfirmingthelegislativemeasure,reducingEnglishtoacompulsorysecondlanguage forallpublicelementary,secondaryanduniversityinstruction intheisland 5

ThedissociationofPuertoRicaneducationfromofficialpolicyinthemainlandwasanotherfeatureofthenewregime.It startedin1947,whenthepopularlyelectedgovernorwasgiven thepowertoappointtheSecretaryofEducation.In1952,with

InformealhonorablegobernadordelEstadoLibreAsociado(SanJuan, PuertoRico:ColegiodeAbogados,1959),pp.61-78,passim.Seealsoreport forthissameCommitteeonCivilRightsbyMiltonPabon,RobertW.Anderson,and.VíctorJ.Rivera,"Losderechospolíticosylospartidospolíticos"(mimeographed),1958.

4.SenateBill,Number51,1946.

5.Thelocaladministrationgotaroundthepresidentialvetoby treatingthematterasanacademiconeandthereforewithinitsjurisdiction.Withthisasprecedent,itispossibleinthefutureforthemedium ofinstructiontoreverttoEnglishbyasimilaradministrativedispensation.

thecreation of the Commonwealth, educationalmatters came under thefull jurisdiction of local authorities.But the legal machineryof theearly"American"periodwasretained.The chief educationalpolicy-makerremainedacreatureof theappointingauthorityandassuchwasboundfirstto"playpolitics" withintheeducationalsystemintheinterestoftheregime 6.

Withinthispoliticalcontext,sincethenativeregimetook over,whathasbeentheeducationalexperienceofthepopulation whichthesystemisdesignedtoserve?Theimplicationsofeducationonoccupation,income,andfertilityratesinPuertoRico havebeenthesubjectofcompetentresearchandstudyandmake anappropriatestartingpointforthepresentanalysis.Fromhere, weshallproceedtotracethegrowthoftheschoolsystemandits impact,usingthefollowingasindices:—expendituresperstudent, studentsperclassroom,student—teacherratio,andteacherpreparation.Finally,growthwillberelatedtoschool-agepopulation, sex,andrural-urbanresidence.

Thefirstbasicingredientofeducationalexperienceisliteracy, ortheabilitytoreadandwrite.InPuertoRico,theproportionof illiterates,amongstpersonsoftenyearsofageandover,declined progressively throughout the period 1940-1960: 31.5 per cent intheearlieryearand17inthelatter.Illiteracyappearstobeless amongstthemalesthanamongstthefemales.Butwhenweconsider residentialorigin,asomewhatdifferentpictureemerges. Urbanfemales,thoughlessliteratethantheurbanmales,are moreliteratethantheruralmales.Thusresidence,notsex,isthe determiningfactorinliteracy.Further,althoughbothgroupsdecreasedtheirproportionateshareofilliterates,therateofdecrease hadbeengreateramongstthefemalegroup'.

Wefindsimilarresultsifweuseasacriterionthemedian

6.TheobviousexampleofpartypoliticsintheDepartmentofEducationisthepublicationbythedivisionofthenewspaper"Semana".This weeklywasdefinedbytheCommitteeoftheGovernorfortheStudyof CivilRightsas"anorganofpoliticalpropaganda"infavouroftheparty inpower.Itisentirelyfinancedanddistributedwithpublicfundsallocated toeducation.Despitefrequentcriticisms,thepresentarrangementstill persists.SeeComitedelgobernadorparaelestudiodelosderechosciviles,op.cit.,p.55.

7.U.S.BureauoftheCensus,U.S.CensusofPopulation;1940.CharacteristicsoftheyPopulation:PuertoRico,BulletinnP2,p.22;Id.,1950, Part.53,ChapterB,p.33;Id.,1960,GeneralandEconomicCharacteristics, p.121.

yearsofschoolingattainedamongsttheadultpopulationof25 yearsandover.In1950,theurbanadultswere1.9gradesabove therural,andin1960,thisdifferencehadincreasedto3.1.Between theurbanandruralmales,thedifferencein1950was2.4infavourofthefirst;in1960,3.7.Thedifferenceamongstthefemales wasalsoinfavouroftheurban,althoughnotasgreatasthat amongst the males. Again, the urban advantage was evident betweenmalesandfemales:themalestendedtosurpassfemales inbothruralandurbanareas,butmalesfromruralsorroundings werebelowurbanfemaleresidentsa.

Theobviousfruitsofliteracyandschoolinghavebeenincome. Thus a man with no schooling received in 1959 a medium incomeof$472;anotherwithoneortwoyearsof elementary education,$690;witheightyears,$1,593;withhighschool,$2,299; andwithacollegedegree,$5,510.Theexperienceofwomenhas beenthesame,althoughtheirmediumincomeshavebeensmaller thanthoseofthemen 9 Inaddition,unemploymentandunderemploymentarelessfrequentamongbettereducatedpeoplelo.

EducationinPuertoRicohasalsobeenshowntobethegatewaytotheoccupationalhierarchy,withitsstatussymbolsand powerresources11. Inotherwords,educationintheisland,as inmanyothercountriesoftheworld,hadtendedtobeaprincipalescalatorforupwardmobility.Thisacquiresgreaterimpetus inasocietylikePuertoRico's,wheretheoldformsofascribed statusaregivingway,underthepressureofsocialandeconomic change,tomore"democratic"methodsofstatus-seeking;where the"certifiedtitles"thateducationconfers"aremorehighlyregardedthaninmostUnitedStatescommunities"12; whereacademicdegreesarethebasicstock-in-tradeoftechnicians,administrators, government officials and top-ranking civil servants;

8.Id.,1960,DetailedCharacteristics,p.249.

9.Id.,1950,Part53,ChapterB,p.174;Id.,1960,DetailedCharacteristics,p.287.SEEALSOMELVINM.TUMIN,SocialClassandSocialChange inPuertoRico(NewJersey:PrincetonUniversityPress,1961),p.62-65.

10.A.J.JAVFE,People,JobsandEconomicDevelopment(Glencoe, Illinois:TheFreePress,1959),p.204-205.

11.Aseriesofstudiesintheruralsub-culturesandtheupperclass, conductedunderJulianH.Steward,pointinthisdirectionandsupport thisassumption.Morerecently,wehaveTumin'sstudyonsocialclassand socialchangetosubstantiateit.Op.cit.,pp.66,69and72.

12.C.WRIanuMILLS,CLARENCESENIORANDROSEK.GOLDSEN,The PuertoRicanJourney(NewYork:HarperandBrothers,1950),p.10.

andwheretheabsenceofanapprenticeshipsystemunderlinesthe educationalneedsofanindustrializingsociety.

Theeffectsofeducationhavealsobeendemonstratedwith regardtofertilityrates.Ontheaverage,"womenwithnoschooling hadthemostchildreneverborn".Thosewithoneortwoyears ofgradeschoolwere"lessfertile"thantheunschooled."Beginningwithwomenwho hadcompletedfour tosevenyearsof gradeschool,fertilityratesdroppedoffsharplyamongstsuccessivelyhigher levels of education,in every age and residence group."Finally,women,whohadgonethroughonétothreeyears ofhighschool,hadratesofchildrengenerally"lessthanhalfas thoseamongwomenwithnoschooling"13_

InclosingthisshortintroductorysectiononthesocialimplicationsofeducationinPuertoRico,weshouldpointoutthe centralideainthegovernment'spolicyofeconomicdevelopment, whichis,"thattheproductivityofthelaborforceisrelatedto theamountandcharacterofitseducation",andfurtherthatthe lackofaneducatedandtrainedlaborforceisanobstacletoeconomicgrowth 1a

Thefoundationof educationaldevelopmentinPuertoRico duringtheperiod1940-1960isthestate'sassumptionofresponsibilityforprovidingeducationtoitscitizens,thelegalsanction forwhichdatesbacktothecomingoftheAmericans.TheSchool Law,asithasalwaysstood,definestheschoolageasthatbetween 5and18yearsandprescribescompulsoryattendancebetween theagesof8and1415.In1952,thiswasreinforcedbyaconstitutionalpledgeonthepartoftheCommonwealthtoassumethe responsibilityforeducation.ThenewConstitutionrecognizesthe rightofallcitizenstoafreeprimaryandsecondaryeducation. However,forallpracticalpurposes,throughtheadditionofan escapeclause,thenewregimewouldhaveprimaryschoolattendancecompulsoryonly"totheextentthattheeconomicresources

13.U.S.BureauoftheCensus,Fertilitybysocialandeconomicstatus forPuertoRico,1950.Washington,D.C.:U.S.GovernmentPrintingOffice, 1954,p.2.Foryear1960see:Id.,U.S.CensusofPopulation:1960,Detailed Characteristics,PuertoRico,p.277.

14.See"Planningforbalancedeconomicandsocialdevelopmentin PuertoRico".(E/CN.5/346/Add.2.)

15.TheSchoolLawsofPuertoRico.(CompiledandrevisedbyA.AndinoLopez),"TheCodifiedSchoolLaw,GeneralProvisions",Section2,p.7.

of thestateshould permit"16. In retrospect,this cautionwas necessary.Throughlackoffacilitiesthegovernmenthasnotbeen abletocopewiththerapidlyexpandingschoolpopulation.Itis thereforenotstrangethatithasbeendisinclinedtogivelegal enforcementtothecompulsoryschoolageattendance(8to14), although thisis thelowest compulsoryschool agewithin the UnitedStatesandherterritories17.

Nevertheless,themostimpressivefactintheeducationaldevelopmentofPuertoRicoduringthetwenty-yearperiodisthe rapidincreaseofschoolenrolmentatalllevels.In1940-41,both publicandprivateschoolsenrolledatotalof293,183students; in1959-60,thetotalfigurewas627,158.Ofthese,4percentwere inprivateschoolsin1940-41,and9percentin1959-60,arate ofincreasegreaterthaninthepublicschools(atwo-foldincrease inthepublicandfourfoldintheprivate).Asaresultof this expansion,PuertoRicoranksaheadofallLatinAmericancountriesandother"underdeveloped"regionsoftheworldinprimary andsecondaryenrolment.Infact,itspatternofdevelopmentis closertothatoftheU.S.A.andother"developed"countriesin EuropethantowhatiscommonlyfoundinLatin America 18.

Thepublicschool expansion no doubtwasmadepossible bytheconstantandsubstantialincreasesinthebudgetaryallocationsfor education, one-third of thestate'sbudget,placing PuertoRicoasthecountrywiththehighestpercapitaschool expenditureinallLatinAmerica($107.34,althoughthelowest inNorthAmerica) 19, andthecountrywiththehighestpercentage of thenationalincomedevotedtopublicexpenditureon education 20. Thegrowthoftheprivateschools,ontheotherhand, maybeduetothelackoffacilitiesinthepublicschools,the

16.ConstitucióndelEstadoLibreAsociadodePuertoRico,1952,ArticuloII,Sec.5.

17.U.S.DepartmentofHealth,Education,andWelfare,Officeof Education,CurriculumResponsibilitiesofState,Washington,D.C.:GovernmentPrintingOffice,1955,p.6-7.

18.UnitedNations,DepartmentofEconomicandSocialAffairs,ReportontheWorldSocialSituation(NewYork:UnitedNations,1961), p.48-49.

19.Vide,BERESFORDHAYWARD,TheFutureofEducationinPuerto Rico-It'sPlanning(HatoRey,DepartmentofEducation,1961),p.6.

20.U.N.E.S.C.O.,BasicFactsandFigures:InternationalStatistics RelatingtoEducation,CultureandMassCommunication(Paris:1962), p.72-79.

failureofpublicinstructiontosatisfytheneedsforhighersocial andacademicstandards,oreventhepolicyofGovernmentitself. AspointedoutbyBeresford_Hayward,aplanningconsultantto theDepartmentofEducation,thereexistsinPuertoRico"aprocedureforbuildingpublicschoolswhichlocatesthemyearsafter anurbanizationhasbeenbuiltandoccupied,thusvirtuallyforcingpeopleinnewurbanizedareasintoprivateschools" 21.

Comparisonofthetotalschoolenrolmentbylevels,thatis, elementary,juniorhigh(7thto9thgrade),andseniorhighschools, showsfurtherdisparityinenrolmentincreases.Whilealllevels expandedintermsof absolutenumbers,theelementaryalone decreaseditsproportioninthetotalenrolment,from83percent in1940-41to68in1959-60.Meanwhile,thejuniorhighenrolment trebledandtheseniorhighquintupled,theresultofwhichhad beenasixfoldincreaseinthenumberofsecondaryschoolgraduates.At theselevels,facilitieshadbeen rapidlyexpanding, apparentlytomeetthedemandsformorehighlyskilledlabor. Theelementary,ontheotherhand,hadalreadyreachedsaturationpoint.Theenforcementofsomekindofuniversalelementary educationin1952hadput90percentormoreofthecorrespondingage-groupinschool.Thedecreaseintheproportionateenrolmentintheelementarymayalsobeduetothemovementof childrenofthisagetotheUnitedStates.Forexample,in1959-60, ofthechildrentransferredtoNewYorkCityandotherplaces onthecontinent,67percent(5,107outof7,677)wereoftheelementaryschool agegroup 22. Finally,the expansion of school facilitieshadnotbeenabletokeeppacewiththerapidgrowth oftheelementaryschoolagepopulation.

Thesamegeneraltrendswithrespecttototalenrolmentare evident if wetakethe private and publicschoolsseparately, althoughtheproportionatedecreaseintheelementarywasless andtherateofincreaseinthejuniorhighgreaterintheprivate schools.

Thischapter is mainly concerned with the public school system,inwhichfrom96to91percentoftheschoolchildren wereenrolledbetween1940and1960,andwhereGovernmenthad sunkagooddealofmoney.Thenumericalexpansionofpublic

21.B. HAYwnnD, op. cit.,p.16. 22.DepartmentofEducation,StatisticalAnnualReportoftheSecretaryofEducation,1959-60(HatoRey,PuertoRico:DepartmentofEducation,1960),p.154.

schoolenrolmentduringthetwenty-yearperiodhadbeenmost impressive,butthisleadsustoaskwhethersuchgrowthhad affectedthe"quality"ofinstructioninthesystem.Thefollowing indiceswillbeusedinouranalysisofthesituation:numberof studentsperclassroom,student-teacherratio,teacherpreparation,andstudentperformance.

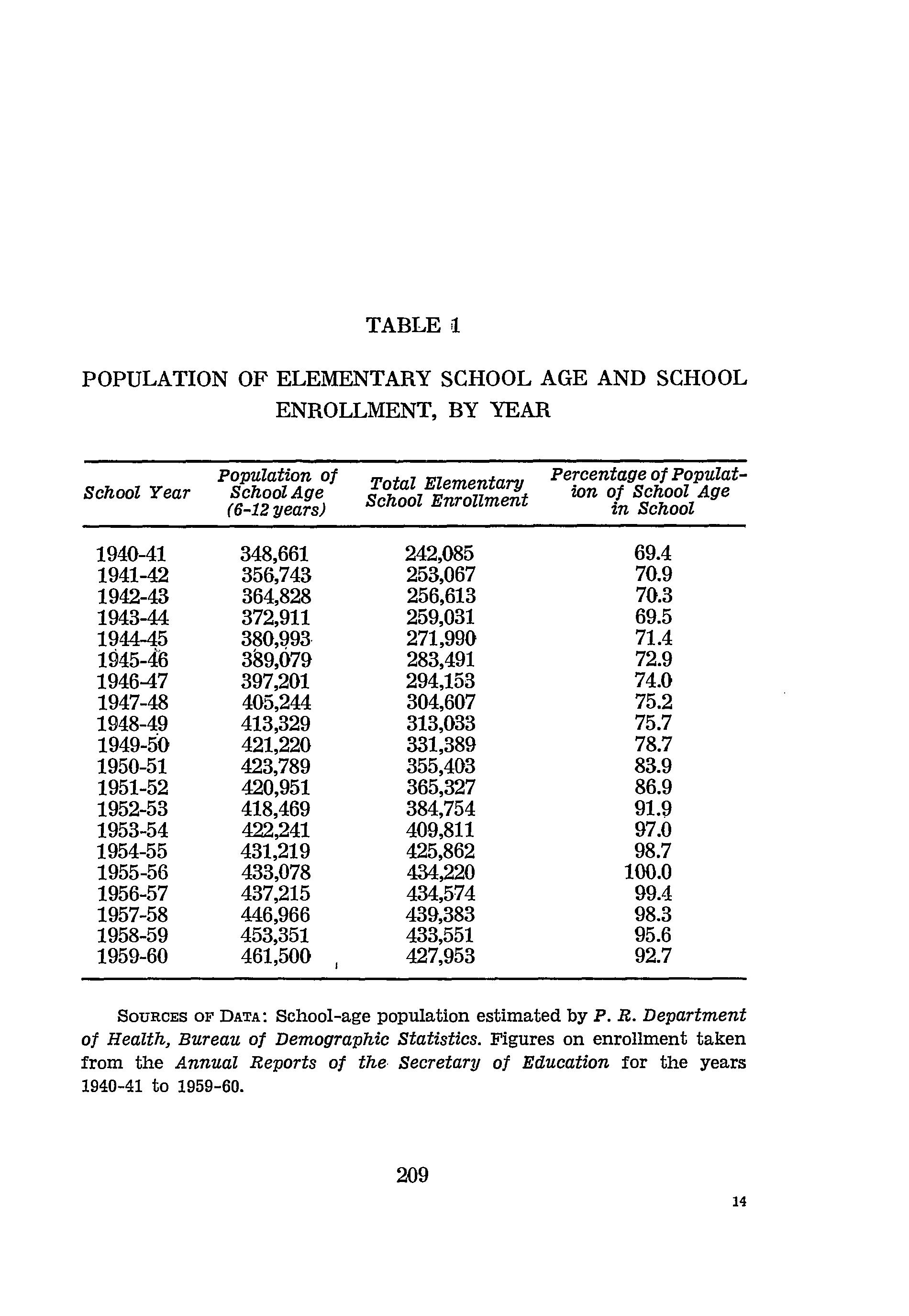

Table1showsthatenrolmentexpansionhadresultedina morethantwo-foldincreaseinthenumberofclassroomsduring

(*)Informationnotavailable.

SouxcEs:AnnualReportsoftheSecretaryofEducation:1940-41to 1959-60.

ourperiod.However,classroomexpansion,thoughprogressive throughout,didnotreducethestudent-classroomratiountil 1958-59.Beforethattime,noteventhe1940markwasmaintained, whilethe1959-60ratio(48.2studentstoaclassroom)wasstill shortofthegoal(40toaclassroom)setforthesystem.Specific databyschoollevelsarenotavailable,butpartialinformation seemstoindicatethatovercrowdinghadbeenmostacuteinthe elementary 23.

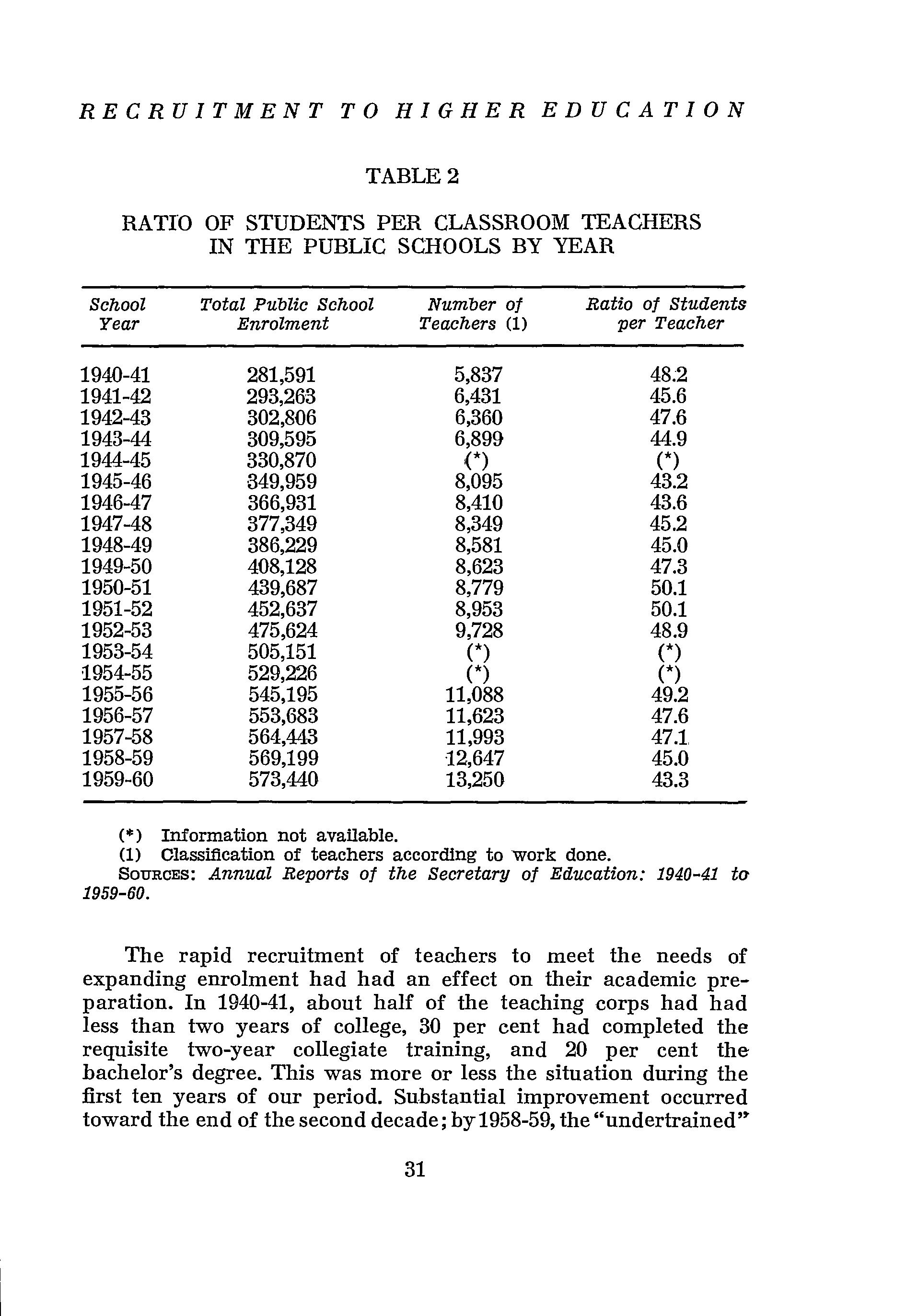

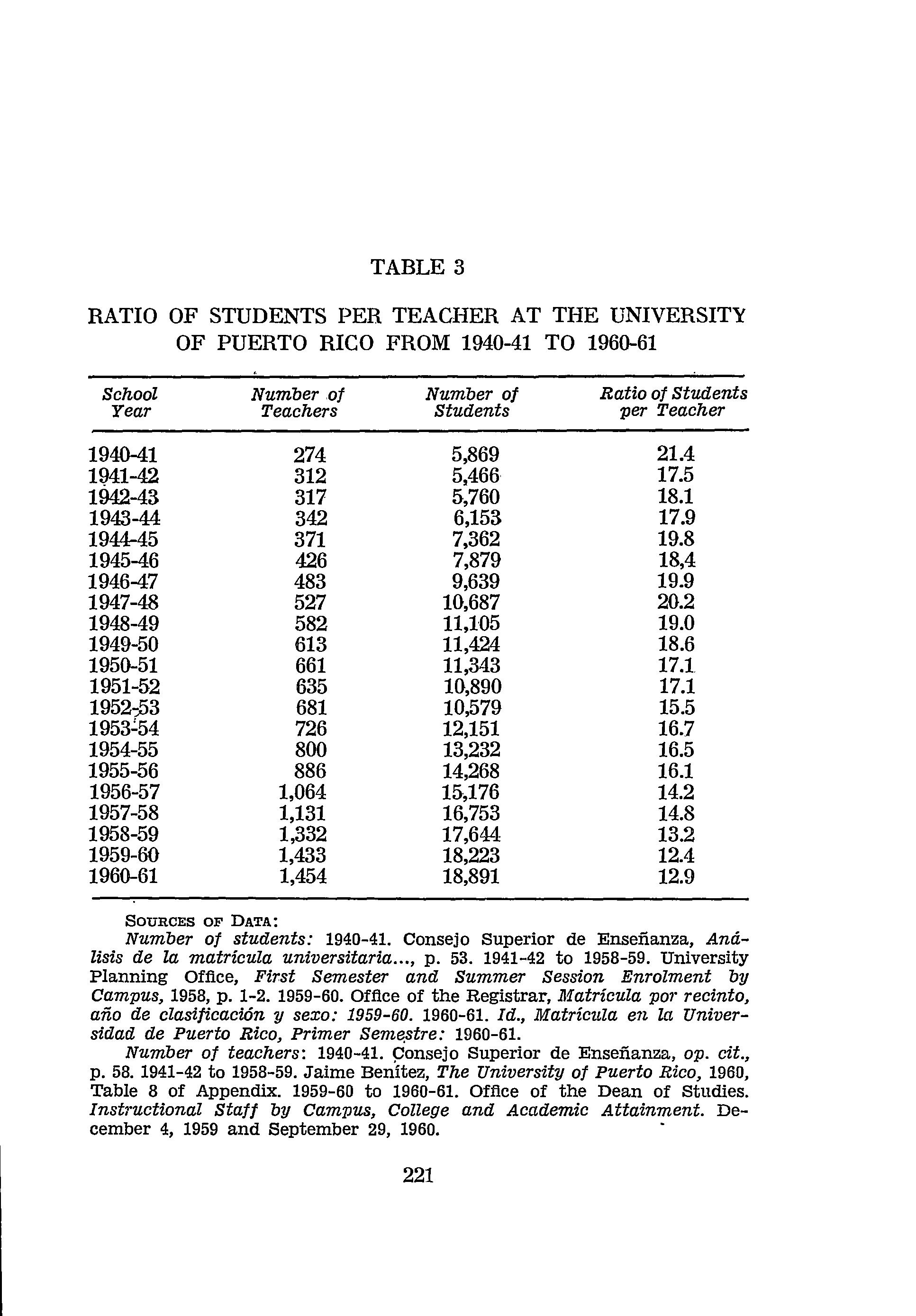

Table2showsthevariationsinthenumberofstudentsper teacher.Wemustcaution,however,thatthefiguresmaybean overestimateoftheactualsituation.Theclassification,"teachers accordingtoworkdone",asusedintheannualreportsofthe DepartmentofEducation,mayverywellincludethosewhodo notactuallyteachbutworkinthesystem.Thetrendsobserved withregardtothestudent-classroomratioarealsonoticedhere. Thepublicschoolsystemhadmorethandoubleditsnumberof teachersduringthesameperiodbutachievedonlyslightreductionsintheratioofstudents,perteacher.Thus,in1959-60, therewere43.3studentstoateacher,comparedto48.2in1940-41, oranimprovementof4.9.ByNorthAmericanstandards,the1959 ratiowasstillveryhighbyatleast10 24. Attheelementarylevel, theoverloadingoftheteacherwasevengreater.Heretheaverage numberofstudentsperteacherhadalwaysbeeninexcessof50, whileinsomemunicipalities,65andmorehadbeenreported 25. Thispupil-teacherratiointheelementaryschoolsoftheisland ismuchhigherthanthatfoundinLatinAmericancountries (excepttheDominicanRepublic),inEurope,Oceania,andmostof thecountriesinAfricaandAsia 26. Inthejuniorandseniorhigh schoolswheretheteachershadbeenmuchlessloaded,thetendencyhoweverhadbeenoneofincreasingtheirloadofstudents (intheformerthefiguresare27.8for1940-41and33.3for1958; inthelattertheyare34.7and37respectively).

23.BERESFORDHAYWARD,TowardComprehensiveEducationalPlanning inPuertoRico(HatoRey,PuertoRico,DepartmentofEducation,1958), p.31-34.

24.Ibid.,p.13.

25.ConsejoSuperiordeEnseñanza,FacilidadesEducativasdelEstado LibreAsociadodePuertoRico(RíoPiedras,P.R.:UniversidaddePuerto Rico,1957),p.218-219.

26.U.N.E.S.C.O.,op.cit.,p.32-37.

(*)Informationnotavailable.

(1)Classificationofteachersaccordingtoworkdone. SouxcEs:AnnualReportsoftheSecretaryofEducation:1940-41to 1959-60.

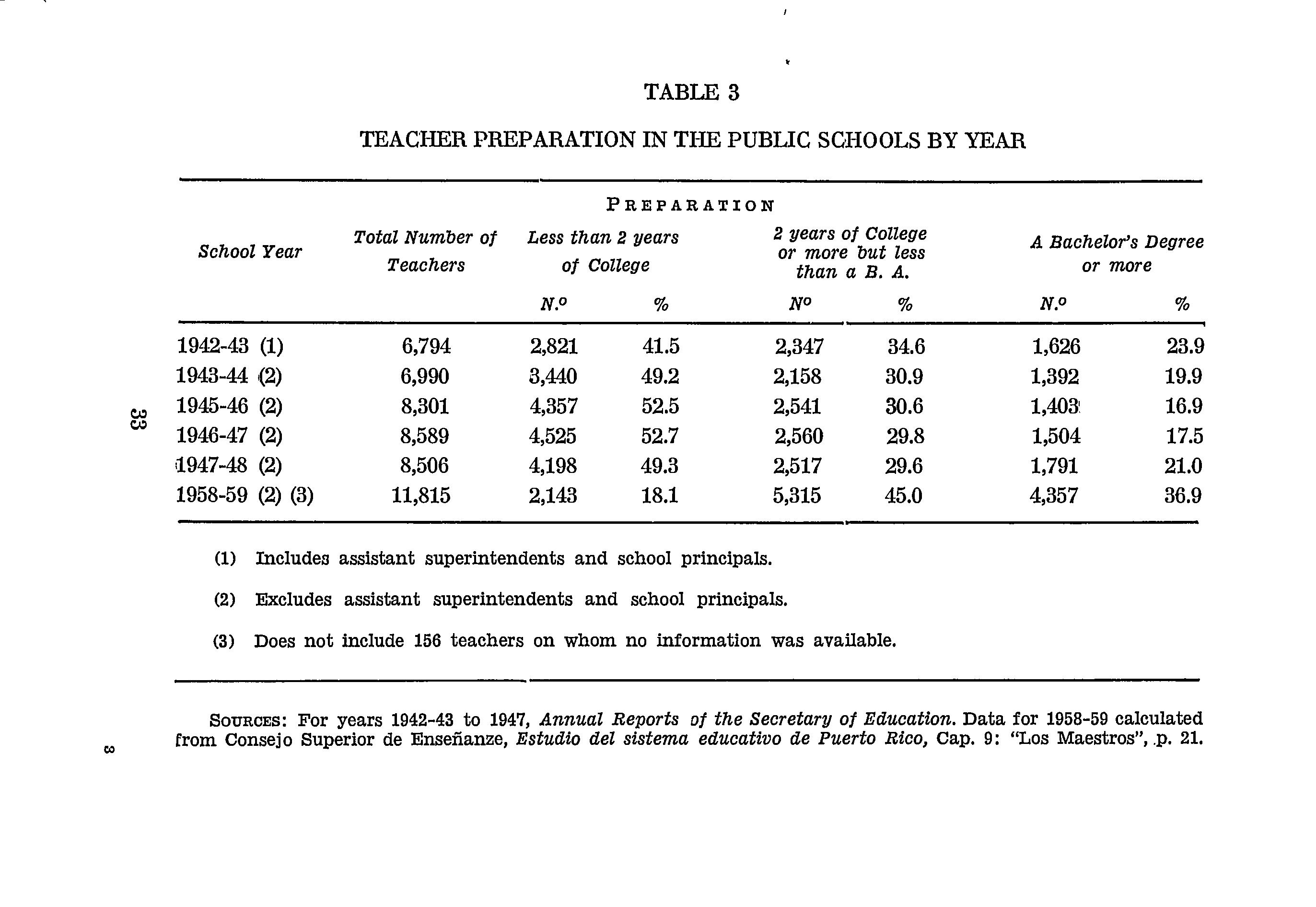

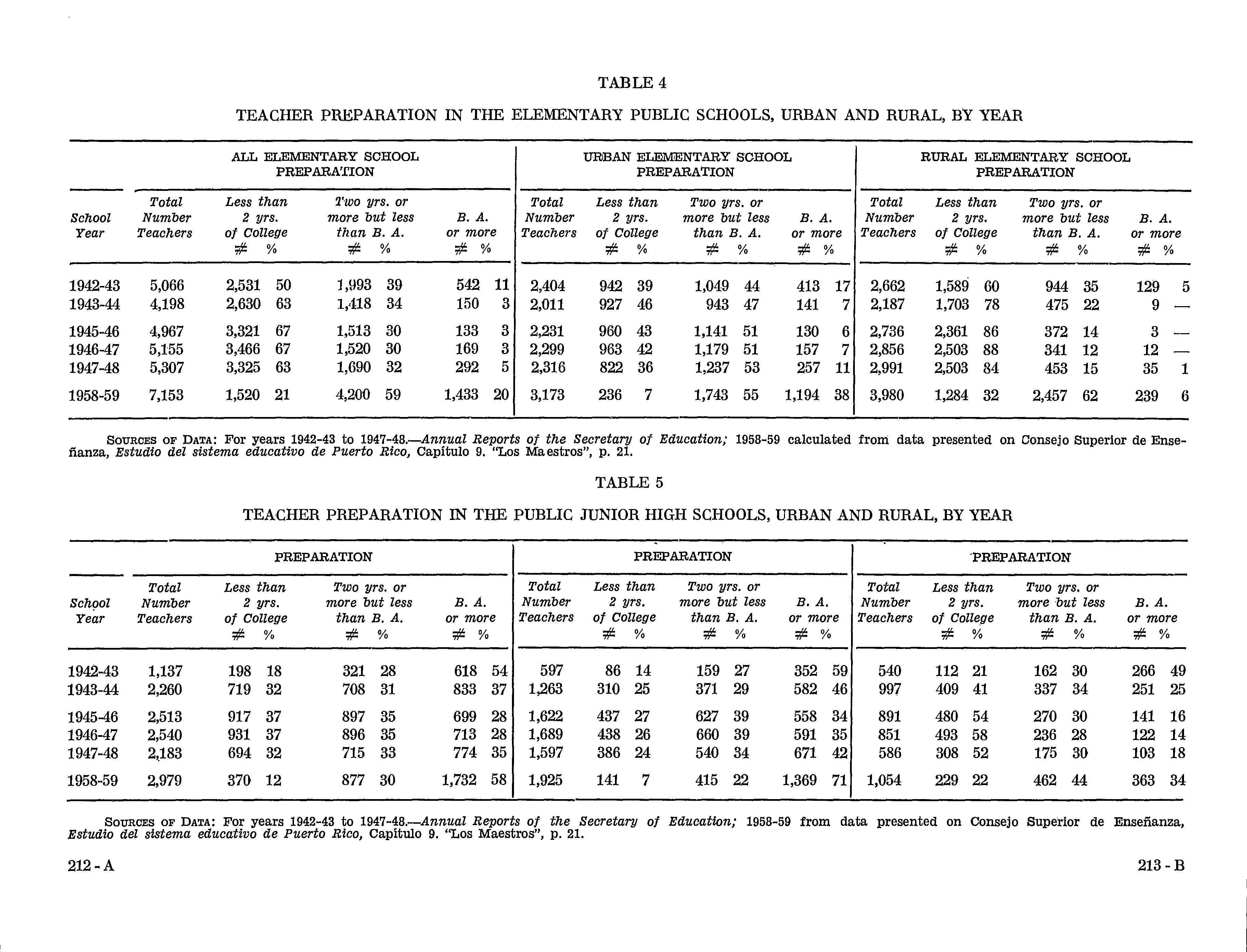

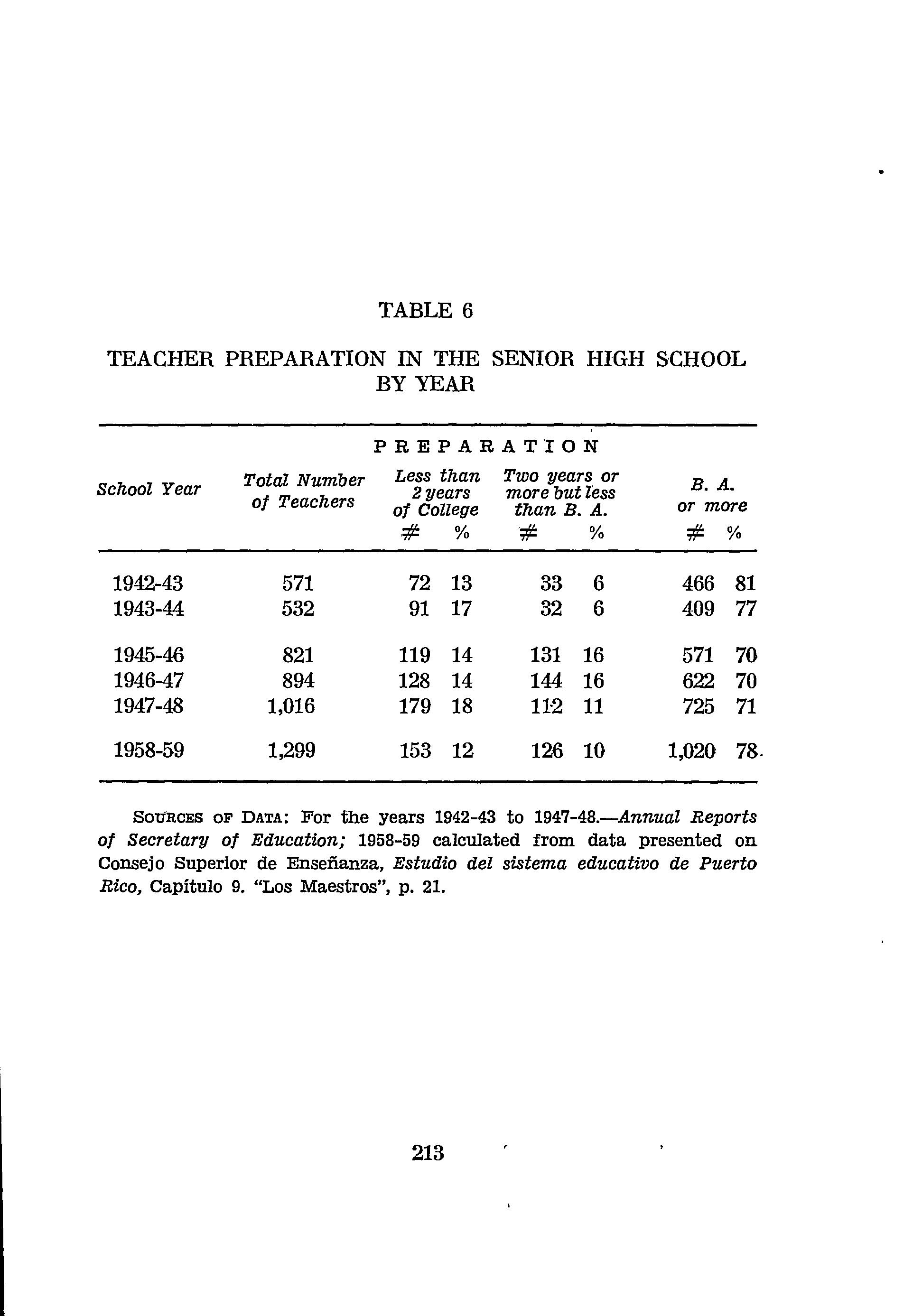

The rapid recruitment of teachers to meet the needs of expandingenrolmenthadhadaneffectontheiracademicpreparation.In1940-41,abouthalfoftheteachingcorpshadhad lessthantwoyearsof college,30percenthadcompletedthe requisite two-year collegiate training, and 20 per cent the bachelor'sdegree.Thiswasmoreorlessthesituationduringthe firsttenyearsofourperiod.Substantialimprovementoccurred towardtheendoftheseconddecade;by1958-59,the"undertrained"

teachershad been reduced to18per cent,while the number of certificateholders and bachelor's degreegraduateshadincreasedto45and37percentrespectively.Teacherpreparation alsovariedfromoneleveltothenext;thehigherthelevelthe highertheacademicattainmentoftheteachingstaff.Butbythe standardssetbytheDepartmentofEducationforthelicensing ofteachers,thatis,aminimumoftwoyearsinateacher-training collegefortheelementaryandabachelor'sdegreeforbothjunior andseniorhighschoolteaching,alllevelswerestillsuffering fromundertrainedteachers 27. In1958-59,21percentoftheelementaryschoolteacherswereunqualified,42ofthejuniorhigh, and22ofthesenior.Viewedfromanotherangle,theproblemin thesecondarylevelsassumesamoreseriousaspect.

Hayward evaluatedthe qualifications of secondaryschool teachersforteachingtheirsubjectsonthebasisofaminimum of18credithoursin thecórrespondingcollegesubjects 28. He foundthat54percentoftheteachingpositions(2,584outof4, 693)werefilledbyunqualifiedpersons:79.6percentamongst teachersteachingmathematics,78.5inSpanish,63.5inEnglish, and57.6innaturalsciences 29. Thisstateofaffairswasconfirmed byotherreportswhichmaintainedthattaechersintheelementaryschoolsdidnothavesufficientmasteryofthecontentand techniquesofteaching 30. Contributingtothissituationisthefact that"manywhoaretrainedasteachers,particularlyforsecondary teaching,donotentertheschools...,andmanyteachersbegin teachingonlytoleaveduringthebeginningoftheschoolyear"31, thelatteraccountingforanetlossofqualifiedteacherstothe systematarateof7to10percentayear.

Inanefforttogetrounditseconomic-educationaldilemma,the systemhashadtoresorttosupposedlytemporarymeasures,one ofwhichdeservesspecialattention.Thisistheso-calledalterna-

27.CertifyingrequirementslaiddownintheDepartamentodeInstrucciónPública.Reglamentosobrecertificacióndemaestrosparalasescuelas públicas,yescuelasprivadasacreditadasdePuertoRico,p.5-6.

28.Onecollegecredithourcorrespondstooneweeklyhourofclass duringasemester.

29.BERESFORDHAYWARD,TheFutureofEducationinPuertoRico: ItsPlanning,p.39-40.

30.OSCARLOUBRIEL,TelevisionforTeachersinService(RioPiedras,P.R.:UniversityofPuertoRico,1961),p.8-11.

31.BERESFORDHAYWARD,TowardComprehensiveEducationalPlanning inPuertoRico,p.11,36.

SchoolYear

(1)Includesassistantsuperintendentsandschoolprincipals.

(2)Excludesassistantsuperintendentsandschoolprincipals.

(3)Doesnotinclude156teachersonwhomnoinformationwasavailable.

SOURCES:Foryears1942-43to1947,AnnualReportsoftheSecretaryofEducation.Datafor1958-59calculated fromConsejoSuperiordeEnseñante,EstudiodelsistemaeducativodePuertoRico,Cap.9:"LosMaestros",.p.21.

tiveenrolmentplan,whichiseitherthe"double"orthe"interlocking".Up to1944-45,theplan of enrolmenthad been the "single", in which the students received five hours of daily classroominstruction,exclusiveofotherschoolactivities.Inthe "double"enrolment,ateacherhandledonegroupofstudentsin themorningandanotherintheafternoon,thelatterreceiving approximatelythreehoursofinstruction.Thishadtheobvious advantageofdoublingtheeducationalopportunitieswiththesame number of teachers and classrooms, but the disadvantage of cuttingbyalmosthalfthe"learning"periodofthestudents.Inthe "interlocking",ateacherworkedinthemorningwithagroupof students and in the afternoon, another teacher worked with anothergroupofstudents,butinthesameclassroom.Herethe studentsreceivedasmanyhoursofclassroomteachingasinthe "single"enrolment.Itsmain disadvantagelayinthefactthat itdidnotprovideabreakwithinthefive-hourperiod,foreither theteacherorstudent,andalsothatitlimitededucationalactivitiesoutsidetheclassroom.

Between1945-46and1956-57,morethantwo-thirdsof the totalschoolenrolmentintheislandwereunderthetwoalternativeplans.Therewasaslightdecreaseinthisproportionin1957-58 andinsubsequentacademicyears,butin1959-60,theplansstill coveredthesubstantialproportionof58percent.Inotherwords, whatwasinstitutedasatemporaryexpedienthadbecomepart andparcelofthesystem.

Theadoptionof thealternativeplanshadvarying effects onthethreeschoollevels.The"double"plan,withitslimited threehoursofinstruction,hadbeenappliedtoelementarygroups only,accountingfor75.3percentofthetotalenrolmentatthis levelin1951-52and61.2in1959-60,whichisnearlytheproportion for1945-46.Ofthetwoupperlevels,thejuniorhighhadhigher proportionsofitsenrolmentinthe"interlocking"thanthesenior high,althoughthetendencyinbothhadbeentoreducethese proportionsandincreasethoseinthe"single"enrolmentplan.

Thequalityofpublicschoolinstructionmayhavealsobeen affectedbythe"promotionpolicy"laiddownbytheDepartment of Education.Thiswas an adaptationtotheNorthAmerican assumptionthatfailureshaveagenerallydetrimentaleffecton thechild 32. Infact,inPuertoRico,schoolfailureshadcometo

32.DivisióndeInvestigacionesPedagógicasyEstadísticas, Estudio

meanadditional economicburdensonthestatebudget,which hadtobereducedtothebarestminimumsoasnottoprejudice otherstudentsseekingadmissiontotheschools 33.

Up to1950, there hadbeen a minimum of requirements prescribedforeachgradelevel,whichwasthebasisofpromotionfromonegradetothenext.Theabilitytoreadwasthefirst requisite,particularlyforpromotionfromfirsttosecondgrade. In1950, the minimum grade requirements, including that of reading,wereabolished,andin1954,thefollowingdirectiveswere issuedregulatingfailures.Nopupilshouldbefailedatthefirst andsecondgrades.Knowledgeofacademicmattershouldnotbe theonlycriterionindecidingapupil'spromotionbutalsothe advantageswhichthechangewouldbringtohisgeneralgrowth anddevelopment.Theteachershouldtakeintoconsiderationall pertinentfactorsphysical,intellectual,emotional,pedagogical, andenvironmental—beforedecidingthefateofapupil.Ifafter dueconsiderationofalltheprinciplesinvolved,theteachershould stillfinditnecessarytofailapupil(afterthethirdgrade),such apupilshouldnotbekeptinthesamegradeformorethantwo consecutiveyears 34 In1957,itwasfurther prescribedthatin instanceswhereteacherswereindoubtastothepromotionof achild,theyweretomakeadecisioninconsultationwiththeimmediatesupervisor,inwhichcasethemainpointtoconsiderwas whatwouldbemost"convenient"forthechild 3s.

sobrelosfracasosenprimergradoenZasescuelaspúblicasdePuertoRico (SanJuan,PuertoRico:DepartamentodeInstrucción,1950),p.7-8.Also: CharlesO.Hamill,"Establishingbasesforasoundpromotionalpolicyin theelementaryschool",HatoRey,PuertoRico:DepartamentodeInstrucción,1961,p.17.

33.DivisióndeInvestigacionesPedagógicasyEstadísticas,Estudio sobrelosfracasosenprimergrado,p.8-9.Also:AnnualReportofthe Commissioner of Education:1947-48,p.75;PabloRoca,"Unfactoreconómicoenlaenseñanzadelalectura",Lalecturaenlaescuelayenlavida: MemoriadelCongresodelaLectura,UniversidaddePuertoRico,1940, p.157-161;ConsejoSuperiordeEnseñanza,Problemasdeeducaciónen PuertoRico(RíoPiedras,PuertoRico:UniversidaddePuertoRico,1947), p.34-44;Id.,FacilidadeseducativasdelEstadoLibreAsociadodePuerto Rico,p.203-214;Id.,EstudiodelsistemaeducativodePuertoRico,cap.11, "Losalumnos",p.81-82.

34.DepartamentodeInstrucciónPública,LaescuelapúblicaenPuertoRico:normasdesupervisiónyadministraciónescolar(HatoRey,Puerto Rico:DepartamentodeInstrucción,1954),p.26-27.

35.ConsejoSuperiordeEnseñanza,Estudiosdelsistemaeducativo dePuertoRico,cap.11,"Losalumnos",p.73.

(1)Figuresonschoolorganizationtakenattheendofthefirstmonthofthesecondsemester. SouRczs:AnnualReportsoftheSecretaryofEducation:1957-58to1959-60.

Atthesecondarylevel,therehadalsobeenatendencyto discouragefailures.Teachershadhadtoshowevidencethatall opportunitieshadbeengiventothepupilwhofailed,thatfrequentandsufficientnotificationhadbeensenttotheparentsof theunsatisfactorystateoftheirchild'sworkandthattheimmediatesupervisoragreedwiththeteacher'sdecision.

In1958,thesystemmadeacompleteturn-aboutonthepolicy ofpromotion.Theminimumacademicrequirementswererestored andfailuresinthefirsttwoprimarygradeswereagainsanctioned.

Anotherpolicywhichhasabearingontheproblemof"quality"inpublicschooleducationisthatofreplacingEnglishwith thevernacularastheprincipalmediumofinstruction.Thelegal operationofthispolicyreactedvisiblyonbookfacilities.Spanish textbookstosubstituteforthoseinEnglishwerenon-existentand yetprescribed.RatherthanfollowtheexampleofmanyLatin Americancountries,whichhadbeenproducingtextsinSpanish, theDepartmentofEducationinPuertoRicostartedoffbytranslatingEnglishtextsandsuggestingalternativeonesinSpanishfor studentstoprovidethemselveswithontheirown 36. Theprocedureinvolvedinthefirstprovedlong-drawnandexpensive,withoutmakingthenecessaryconceptualadjustmentsfromonesocial contexttoanotherwhichisthefirstlogicalreasonforanyswitch inthemediumofinstruction.Thenatureoftheproblemisclearly reflectedintheSchoolLawof1952whichboundtheGovernment, withitsdemonstrablylimitedresources,toprovidebooksfreeof costintheelementary, junior andseniorhighschools 37 The progressmadealongthislineattheelementarylevelbetween 1944-45and1955-56appearsinadequate.Inthesecondacademic year,firstandsecondgradersreceivedpracticallythesamenumberofbooksasinthefirst,orone-thirdofthe"required"number assetbytheDepartmentofEducationitself.Inthehighergrades, wheretheimprovementhadbeengreater,thefiguresfor1955-56 wereasfarshortofthemarkasthoseofthelowergrades,i.e., thirdandfourthgradesreceivedhalf oftheestimatednumber

36.Itseemsthatthisdecisionwastaken,first,toavoidanyimpressionthatthenewregimewasgetting"tooclose"toLatinAmericaand thusnearertoindependenceasasolutiontotheproblemofpoliticalstatus, andsecondly,duetopressureofprintinginterestsintheUnitedStates whowereafraidoflosingpublicationcontractstoforeignconcernsin LatinAmericaorSpain.

37.LeyesdePuertoRico(SesionesExtraordinarias,1952),p.7-9.

andfifthandsixthgradesonethird.Inthesecondarylevels,where therateofimprovementwasstillgreater,thegapbetweenactual (1955-56)andtheoreticalnumbersremainedwide.Intheseventh andeighthgrades,bookfacilitieswerestillonlyone-halfofthe prescribedamount;inthetwelfth,thebestsuppliedofall,the proportionwasfive-sevenths.

Our inquiry now takes us to the subjectof actual academicperformanceinthe publicschools.Wearehandicapped bytheabsenceofspecificdataonthismatterandcanonlyintroduce relevantinformation from scattered sources. In1958, fourthandfifth-gradeteachersreportedtotheSecretaryofEducationwhatappearedtobea"seriousdeficiencyinthereading of students".Theyrevealed the inability of fourth and fifthgraderstoreadevenfirstgradebooks;over10percentinsome districtswere non-readers.And in someschools,"ashigh as one-thirdofthestudentsintheupperelementarygrades"were foundunabletoread"38.

Thatpubliceducation,asreflectedinstudentperformance, seemsalsotohavedeterioratedwasdemonstratedbytheSuperior EducationalCouncil,whichadministeredthesamesetoftestsin Spanishreadingcomprehensionin1956and1959.Itwasfound thatwiththeexceptionofthefourthgrade,allelementarylevels gaveresultsin1959"inferior"tothoseobtainedin195639 The Councilalsoadministeredin1959abatteryofteststomeasure comprehensionandlinguisticabilityinbothSpanishandEnglish andalsothepowerofmathematicalreasoning.Thesetestswere given to a representativesample of fourth, sixth, ninth, and twelfthgraders,whichtotalled32,942,frombothpublicandprivateschools.Fromtheresults,itwasconcludedthat"onthewhole, thestudentsmatriculatedinprivateschoMshavegreaterindices of performance than those matriculatedin public schools"40, InformationontheentranceexaminationfortheUniversityof PuertoRicoconfirmstheCouncil'sfindings,asweshallseein asubsequentchapter.Theprivateschoolexamineesdidbetter

38.See:BERESFoRDHAYWARD,TowardComprehensiveEducational PlanninginPuertoRico,p.5;andEverettReimer,"ImplicationsofEconomicDevelopmentforEducation",SanJuan,P.R.:CommitteeonHuman Resources,p.10.

39.ConsejoSuperiordeEnseñanza,Estudiodelsistemaeducativode PuertoRico,cap.15,"Resultadosdelosexámenesadministradosenalgunas áreasynivelesdelsistemaescolar",p.178.

40.Ibid.,p.90-94,170.

notonlyintheoverallresultsbutinthoseobtainedontheseparate partsoftheexamination.Thegapascomparedwiththepublic schoolswillbeshownfurthertohavewidenedthroughtheyears. PerformancewithintheUniversityitselfwillalsobeseentobe increasinglyinfavouroftheprivateschoolgraduates.Another typeofevidencecollectedattheRegistrar'sOfficeofthatUniversity,moreover,showsthatin193-54,86.9percentofallnew studentssuspendedforacademicreasonswerefrompublicschools (99outof114),atendencywhichpersistedinsubsequentyears 41, Havingthusdweltatlengthontheimpactoftheexpansion oftheschoolpopulation,especiallyasitbearsonthe"quality" ofpublicschooleducation,weshallproceedtoinquireintothe effectsofsuchexpansiononthedifferentlevelsoftheschool-age populationandthedistributionbysexandrural-urbanresidence intheschoolpopulation.

Weshouldnotefirstofallthattherateofincreaseinthe schoolpopulationoverthetwenty-yearperiodwas.2.1,whilethat oftheschool-agepopulationwas1.3.Thus,astable5shows,while in1940-41aboutfiveoutof10studentsofschoolagewereenrolled, in1959-60theratiohadincreasedtoeightoutofevery10.The proportionateincreaseswereprogressiveatfirst,until1955-59 whenthefiguresrepresentedaplateau.In1959-60aslightdecline wasinevidence.Theabsenceofprogressinthelastfiveyearsmay beareflectionoftheeconomicstressesoftheeducationalsystem orthelimitsbeyondwhichthesystemcouldnotpossiblyexpand.

Theexpansionofschoolenrolmenthaddifferentmeanings forthevariousage-groupswithintheschool-agepopulation.We mayhavetolooktothepolicyoftheGovernmentfortheunderlyingcauses.Thestrategyofeducationaldevelopmentin PuertoRicoappearstohavebeenoneofabsorbingtheentiree1e-

41. See:OfficeoftheRegistrar, Informesobreelexamendeingreso, U.P.R.1952-53;Informesobreelexamendematemáticasparacandidatos aingresoenZaU.P.R.,1955;Informesobreelexamendeingreso,1954; ReportsontheEntranceExamination:1955to1960. Fordataonfreshman grades,seeappendixtablesofthisstudyandConsejoSuperiordeEnseñanza,op. cit.,p.24,60-69;Id.,Astudyofthehighschoolacademicindices as acriterionforcollegeadmission,p.8-36 and 77 to 78C. Forsuspensionsattheendofthefreshmanyear,see:Officeofthe Registrar, Estudiantesnuevossuspendidosporinstitucióndeorigen 1954-1960.

Forperformancethroughoutthefourcollegeyearsseedatainour appendicesandConsejoSuperiordeEnseñanza, Recursoshumanoscon preparaciónuniversitaria(Río Piedras, P. R.: U.P. R., 1958),p.27-52.

SOURCESOFDATA: SchoolagepopulationestimatedbyP.R.Department ofHealthBureauofDemographicStatistics.

FiguresonenrolmentfromAnnualReportsoftheSecretaryofEducation:1940-41to1959-60.

mentaryschool-agepopulation(6to12years),andofexpanding facilitiesfortheupperlevelsaccordingto availableresources. Thusby1960almost everychildof theelementaryagegroup wasinschool,theproportionsfallingattheupperlevels:seven outof10atthejuniorhighschoollevel(13to15yearsofage) andfouroutof10atthesenior(16to18years).However,therate ofincreaseattheelementarylevelwassmallerthanthatofthe highschool.

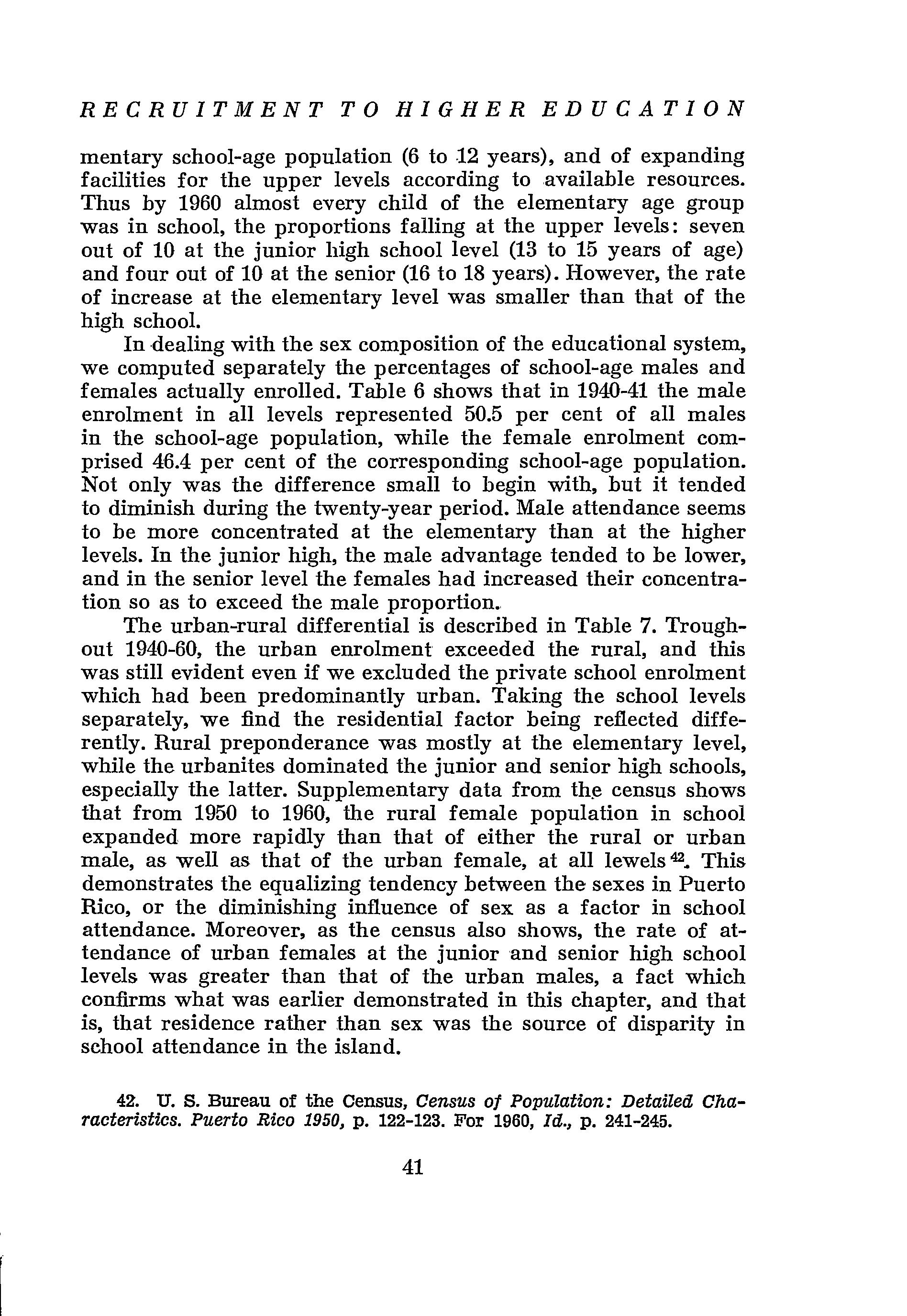

Indealingwiththesexcompositionoftheeducationalsystem, wecomputedseparatelythepercentagesofschool-agemalesand femalesactuallyenrolled.Table6showsthatin1940-41themale enrolmentinalllevelsrepresented50.5per centof allmales intheschool-agepopulation,whilethefemaleenrolmentcomprised46.4percentofthecorrespondingschool-agepopulation. Notonlywasthedifferencesmalltobeginwith,butittended todiminishduringthetwenty-yearperiod.Maleattendanceseems tobemoreconcentratedattheelementarythan atthehigher levels.Inthejuniorhigh,themaleadvantagetendedtobelower, andintheseniorlevelthefemaleshadincreasedtheirconcentrationsoastoexceedthemaleproportion..

Theurban-ruraldifferentialisdescribedinTable7.Troughout1940-60,theurban enrolmentexceeded therural,andthis wasstillevidentevenifweexcludedtheprivateschoolenrolment whichhadbeenpredominantlyurban.Takingtheschoollevels separately,wefind theresidentialfactorbeingreflecteddifferently.Ruralpreponderancewasmostlyattheelementarylevel, whiletheurbanitesdominatedthejuniorandseniorhighschools, especiallythelatter.Supplementarydatafromthecensusshows thatfrom1950 to1960,theruralfemalepopulationinschool expandedmorerapidlythanthatof eithertheruralorurban male,aswellasthatoftheurbanfemale,atalllewels 12 This demonstratestheequalizingtendencybetweenthesexesinPuerto Rico,orthediminishinginfluenceofsexasafactorinschool attendance.Moreover,asthecensusalsoshows,therateofattendanceofurbanfemalesatthejuniorandseniorhighschool levelswasgreaterthanthatoftheurbanmales,afactwhich confirmswhatwasearlierdemonstratedinthischapter,andthat is,thatresidenceratherthansexwasthesourceofdisparityin schoolattendanceintheisland.

42. U.S.BureauoftheCensus, CensusofPopulation:DetailedCharacteristics.PuertoRico1950,p.122-123. For 1960,Id.,p.241-245.

(*)informationnotavailable.

SOURCESOFDATA:School-agepopulationbysexestimatedbyP.R.DepartmentofHealth,BureauofDemographicStatistics.

EnrolmentbySexfromAnnualReportoftheSecretaryofEducation: 1940-41to1959-60.

(1) FiguresonenrolmentasattheendoftheSchoolYear.

SOURCES of DATA:AnnualReportsoftheSecretaryofEducation1940-41 to 1959-60.

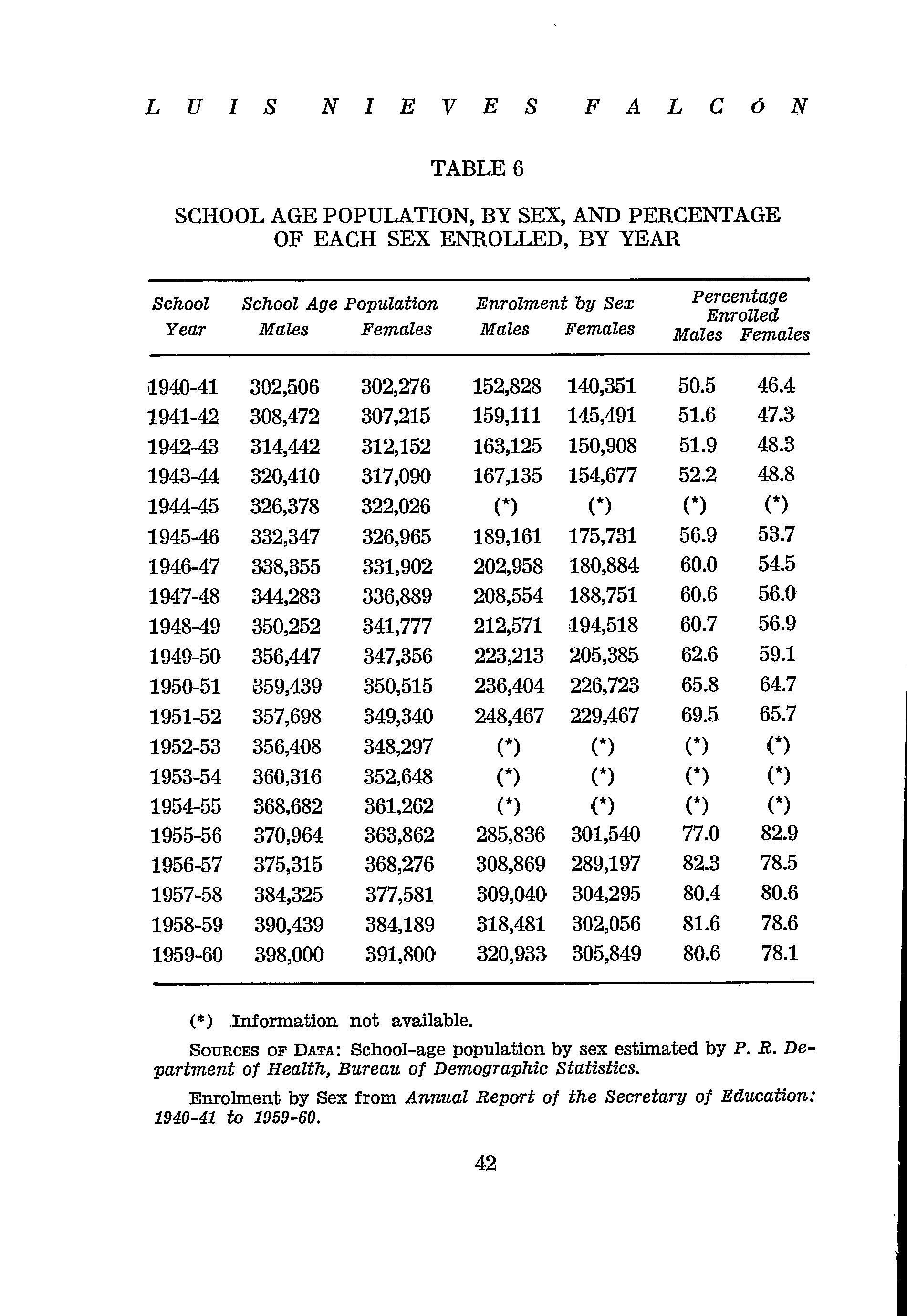

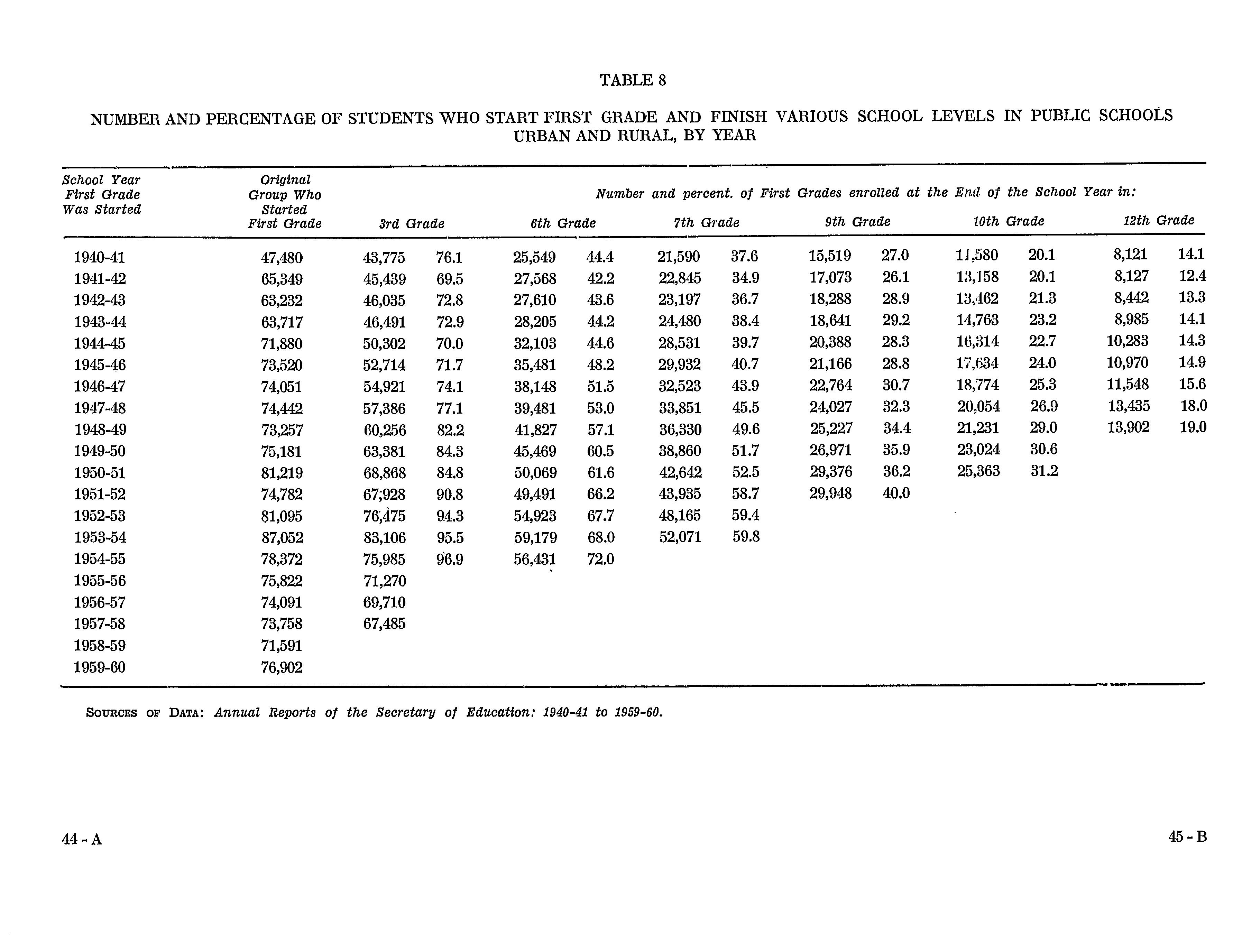

Wehavethusshownthesomewhatinsignificantdifferential betweenmaleandfemaleschoolchildren,andthemajor one betweenruralandurbanresidents.Ournexttaskistoevaluate the"holdingpower"oftheentireeducationalsystem,asreflected inthecompletionornon-completionofthevariousgradelevels. InPuertoRico,theSchoolLawdefinestheageof compulsory school attendance as that between 8 and14 years, covering roughlythetimerequiredtofinishjuniorhighschool.Thusit maybeassumedthatthegreatertheproportionwhichpassesthis level,thegreatertheholdingpowerofthesystemorits"effectiveness".

Table8showstheoriginalgroup ofstudentswhostarted firstgradeineachacademicyearcoveredbythisstudy,andthe proportionwhichwentintoandpassedasucceedinggradelevel. Oftheelementarygrades,onlythethirdandsixthareexamined, beingthemidandfinalpointsoftheelementaryschooling.Similarly,theseventhandninth,andthetenthandtwelfthrepresentthecrucialstagesinjuniorandseniorhighschooleducationinPuertoRico.Itwillbenoticed thatthroughout our period,therewasamarked"strengthening"oftheholdingpower ofthepublicschoolsystem,asevidencedbytheprogressively increasingproportionsofthosepassingateachgradelevel.Thegap betweenfirstgradeentrantsandthirdgradepassers,inparticular,hadnarrowedconsiderablyastoshowamere3.1percent ofleaversoutofthe1954-55group.However,theproportionin thesameyearof thosewhofinishedthewholeof elementary schoolingwasgreatlyreducedafterthethirdgrade,leavingmore thanaquarterofthefirstgradegroupamongstthedrop-outs. Ifwerecallthefactthatmostoftheschoolsattheelementary levelwereonthedoubleenrolmentplanwithitsthreehoursof dailyinstructioninsteadoftheusualfiveinthehigherlevels, wegetthepictureofacorrespondinglyhugenumberofchildren supposedly finishing the elementary stage but whose actual schoolingwasequivalenttothreeschoolyears,thebarestminimumrequiredtoattainliteracy.

Aftertheelementary,thepropórtionsofthosewhocontinued inschooldiminishedprogressivelyastheyreachedthehigher grades.Moreover,ifwelookatthedifferencebetweenthepercentageofthe1940-41groupwhichfinishedthesixthgradeand enteredtheseventh,andcompareitwiththatforthe1953-54 group,wenoticethattheproportionofsixth-gradeleavershad grownovertheyears.Thus,ofthe1940-41groupoffirst-graders,

NUMBERANDPERCENTAGEOFSTUDENTSWHOSTARTFIRSTGRADEANDFINISHVARIOUSSCHOOLLEVELSINPUBLICSCHOOLS URBANANDRURAL,BYYEAR

SOURCESOFDATA: AnnualReportsoftheSecretaryofEducation:1940-41to1959-60.

44.4percentfinishedsixthgradeand37.6continuedtoseventh, ora differenceof 6.8per centof drop-outsbetweenthe two grades.Forthe1953-54group,theproportionswere68.0and59.8 respectively,andthedifference8.2.Theselectivenessatthebeginningofthejuniorhighschoolincreasedinintensityfromone academicyeartothenext.Also,theproportionofpupilswho startedthislevelandleftbeforefinishingincreased.

Afterthecompletionofthejuniorhighschool,furtherselection continued, though to a lesser degree.Thechances for continuingtotheend of thesecondaryeducationwerefairly goodforthosewhohadreachedninthgrade.Butaswiththe junior highlevel, theproportion of thosewho, havingbegun seniorhigh,leftinthemiddle,increasedbetweenthe1940-41 and1948-49groups.

Applyingthesamekindofanalysistotheurbanandrural elementaryschools(theonlylevelforwhichthistypeof data wasavailable),wefindthatwhile96outofevery100children intheurbanschoolsreachedtheendoftheirelementaryschooling, only 58 out of 100 did so in the rural zones. The rate of withdrawalsamongstthelatterwasasgreatbetweenfirstand thirdgradesasitwasbetweenfifthandsixth.Itseemsthatit wasintheruralregionsthattheschoolsystemwasfacedwith the difficult problem of ensuring aminimal education to the rapidlyexpandingschoolpopulation.

This urban-rural dichotomyhad been perpetuatedby the existenceoftwotypesofschoolfacilitiesintheisland,onefor the"privileged"urbanites,andtheotherforthe"underprivileged"ruralites.Theruralschoolsgenerallylackedcertainminimumfacilities.Moreoftenthantheurban-locatedschools,"they lacklighting,watersupply,adequatesanitaryservices,andrecreationalplaces" 43 Therewasmuchtobedesiredintermsof rural"buildings, equipment,books, and teachingmaterials"'. Janitorialserviceswere usually non-existent and teacher and pupilalikewerecalledupontoperformthem.Atthebeginning of theschoolyear,aroutinesightattheofficeof theschool superintendent was the distribution of materials to the rural

43.RamónA.Cruz,"Elfuturodelaescuelapuertorriqueña:suplaniflcación",HatoRey,P.R.:DepartamentodeInstrucciónPública,1961,p.5.

44.JesúsMaurasPovertud,"Laescuelaelementalpuertorriqueña", HatoRey,P.R.:DepartamentodeInstrucción,1961,p.22.

teachersandamongstthefirsttobehandedoutwereabroom, cleaningrags,apailandsomesoap.

Notonlywerephysicalfacilitiesinaworseshapeinthe ruralschools,butalsotheteachingloadoftheteachersherewas greaterthanthatoftheurbanteachers.Theaveragenumber ofstudentsperteacherintheruralschoolswas61in1949-50, 61.3in1955-56,and53in1958-59.Intheurbanschoolsthefigures were57,58and52respectively ¢5. Nearlyallthemunicipalities (95percent)hadmorethan50studentstoateacherintherural areas;somehadasmanyas86.Addtothisthefactthatunder thedoubleenrolmentplan,whichwastheruleamongstthe elementaryschools,teachersusuallytaughtmorethanonegrade ofstudents.Theeducationalsurveyof1959showsthat54per centoftheelementaryruralteacherstaughttwoormoregrades, against11.7percentintheurbanzones.Intheruraljuniorhigh schools,8percentoftheteacherswereengagedinelementary teachingaspartoftheirteachingload 4s,

Underthedepartmentalizedsubjectcurriculumsuchas PuertoRicohas,teachingmeanseightsubjectareaspergrade andthecorrespondingnumberofelaboratedailylessonplans. Someelementaryschoolteachersinfacthavetomakefrom10to 16detaileddailyprogrammestosatisfysupervisorydemands,not tomentionthecorrectionandmarkingofpapers,andattendance atprofessionalandparent-teachermeetings.

Otherformsofbiasagainsttheruralareasandruralchildren existed.Theteachersweregenerallylessfullytrainedthanthose intheurbanzone;60percentofthoseteachingintheelementary schoolsin1942-43hadhadlessthantwoyearsofcollegetraining comparedto39percentamongsturbanteachers.In1958=59,the proportionofuntrainedteachersintheurbanareashadbeen reducedto7percent,whiletheruralproportionwasstillashigh as32.Moreover,amongsttheprovisionalteachersthosewithless trainingwereplacedinruralschools Infactaslongasthe selectionofteachersisregulatedinthepresentmanner,the

45.Forsourcesonstudentsperteacherinruraláreassee:Consejo SuperiordeEnseñanza,FacilidadeseducativasdelEstadoLibreAsociado dePuertoRico,p.217-238;andDivisiondeEstadísticas,Informesobrela matrículaymaestrosdesalóndeclasesalterminarelsextomesescolar: 1958-59,tables2and3oftheappendix.

46.ConsejoSuperiordeEnseñanza,Estudiodelsistemaeducativode PuertoRico, 9,"Losmaestros",p.61-62. 47.Id.,p.64.

discrimination against rural teachingwill persist.Positions at thebottomoftheregisterofeligibleswereusuallyassignedto ruralschoolsandwerenaturallyheld by thelessqualified 48. Ruralteacherswerenotonlylessacademicallyprepared,they werealsolessexperienced and receivedlesssupervision.The directsupervisiónofruralelementaryteachersisinthehands ofanassistantsuperintendent,whosupervises38teachersonthe averagecomparedtothe15undertheurbanelementaryschool principal 4s,

Ruralgradeofferingsweregenerallyattheelementarylevel, withahighconcentrationinthefirstthreegrades,"sinceagreat numberof ruralschoolsdonotofferstudentsthefacilitiesto finishtheelementaryschool" 50. Mostofthoseelementaryschools wereonthedoubleenrolmentplan,74.3•percentin1959-64comparedto44amongsttheurbanelementary.

Socialandhealthserviceswerealsofewerorlessaccessible totheruralchild.Vocationalcounsellingwaspracticallybeyond hisreach.Hislibraryfacilitieswerealsolessadequate.Hischances of getting government scholarships were limited; in 1954-55, 35percentofhiskindreceivedsuchboonsandin1958-59,this proportionwasreducedto28.1percent 51,

The apparent,systematic discrimination against the rural zonesforeducationalpurposeswasreflectedfirstofallinthe ruralchild'sreadingperformance,whichwasfoundtobegenerallylowerthanthatofhisurbancounterpart.Thisdisadvantage wasbornebytheruralchildrenallthroughtheirschoolingand wasmostpalpableinarithmeticalreasoning,readingcomprehensionofEnglishandSpanish,andotherlinguisticabilityperformances.It alsofollowsthat theproportion of schoolfailures amongst themwould begreater thantheirshareinthe total enrolment.Furthermore,thedisproportionaterepresentation of ruralstudentsamongsttheschoolfailurestendedtoincreaseover thetwenty-yearperiod.

Fromtheevidence•analyzedabove,wecandrawthefollowing

48. RAMÓN A. CRUZ, O. cit.,p.5.

49.Thissituationlededucationalofficialsthemselvestoconcludethat supervisionintheruraláreaswas"limited,sporadic,andlackinginefficiency".J.M. PovERxun, op.cit.,p.21.

50.Ibid.,p.20.

51.ConsejoSuperiordeEnseñanza,Estudiodelsistemaeducativode PuertoRico,Cap.11,"Losalumnos",p.99.

generalconclusions.Thegrowth of the educationalsystemin PuertoRicohadvaryingeffectsonthepublicandprivateschools. In spite of the increasing government budgetary allocations, publicschoolfacilitieshadnotkeptpacewiththerapidlyexpandingenrohnent.Thequalityofinstructionandofstudentperformancehaddeterioratedinthepublicschoolsbutimprovedinthe private.Thiswillbemoreamplydemonstratedinsubsequent chapters.Thedilemmaofpubliceducationisparticularlyreflected intherural-urbansituationattheelementarylevels.Hereinlies thekeytotheeducationaldifferentialoperatingintheisland. Itisatthoselevelsthattheselectionprocessbeginsandimpedes aconsiderablenumberofruralchildrennotonlyfromcontinuing tothesecondarylevelbutevenfromfinishingtheirelementary schooling.Limitedfacilitiesanddiscriminatorypracticesinfact hadhadanincreasinglynegativeeffectontheeducationaldevelopmentoftheruralchild.Itisuthereforedebatablewhether• thepresentgovernmentishonoringtheconstitutional,guarantee to"everyperson...therighttoaneducationgearedtowardsthe strengtheningofrespectforhumanrightsandthefundamental liberties" 52.

Inpurelyeconomicterms,unlesssomethingdrasticisdone toreversethesituationintheruralschools,theislandwillcontinuetobefloodedbyasuperfluityofmanpowerinadequately preparedtocarryouttheeconomicgoalssetbytheir"politicos". OntheproblemofpopulationgrowthinPuertoRico,education alsoseemstohaveadirectbearing.Inacountryinwhichthe officialencouragementofcontraceptivemethodshassofarproducedlittleresults,butwhereitcanbeshownthatwomenwith sixyearsormoreofschoolinghavelowerfertilityratesthan thosewithlessschooling,educationmayprovideamoreeffective checktopopulationgrowth.

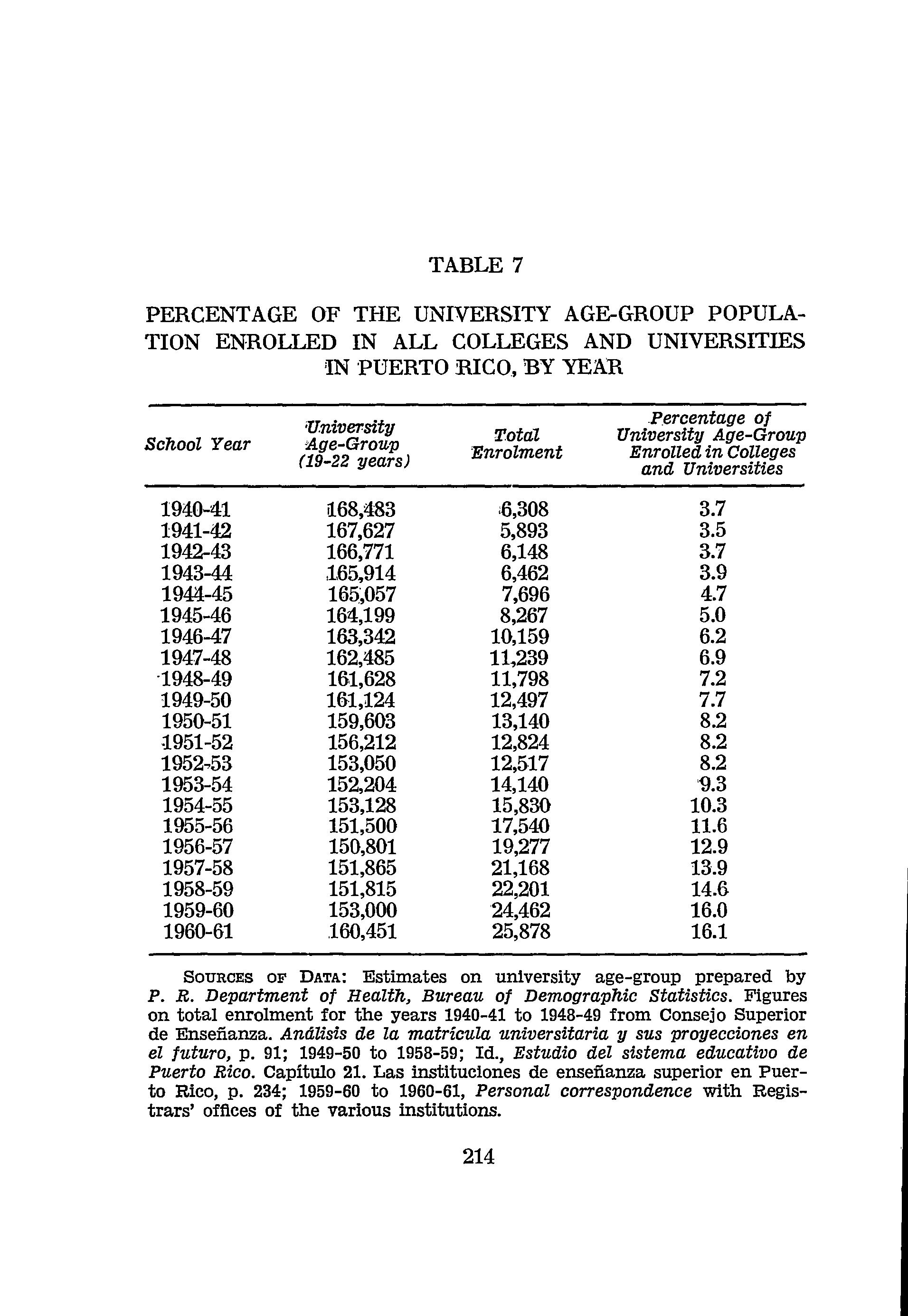

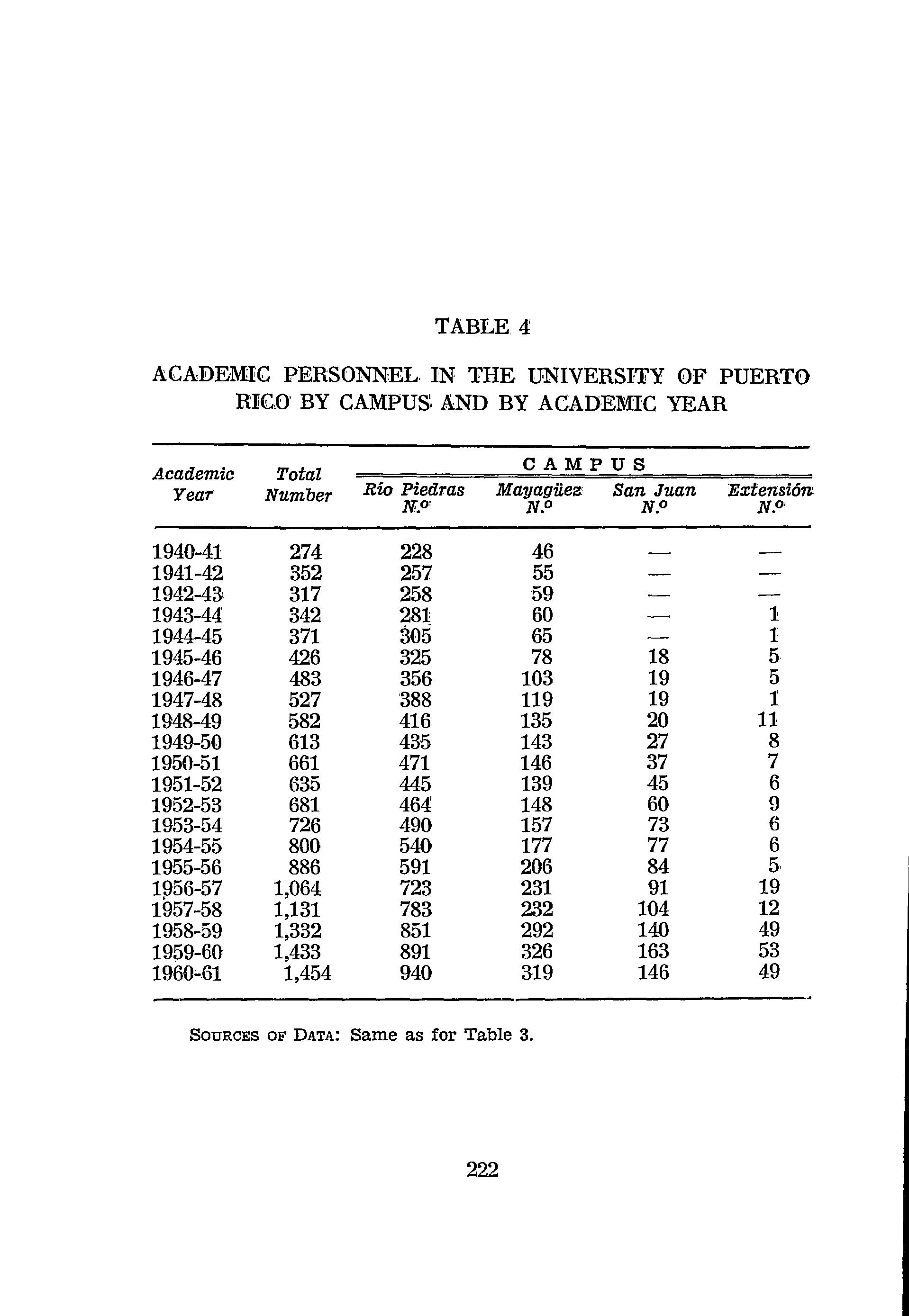

Inhighereducation,theinfluenceof populationgrowthat thelowerschoollevels,thequalityofpubliceducationandthe ruraldiscriminationwasparticularlyfelt.Thisisthesubjectof detailedconsiderationinsubsequentchaptersandforthepresent weneedconcernourselvesonlywiththenatureoftheexpansion attheuniversitylevel.Duringthetwenty-yearperiodunderstudy, enrolmentattheuniversitylevelexpandedmorethanfourtimes; from6,308enrolleesin1940-41to25,878in1960-61.Basedonthe

52.ConstitucióndelEstadoLibreAsociadodePuertoRico,1952,ArticuloII,Section 5.

school-agepopulation,collegeattendancein1960-61represented 16percentoftheeligibleage-group,oranincreaseoffourtimes overthatoftheacademicyear1940-41.Itwillberecalledthat thehighschoolgraduatepopulationhadincreasedsixtimesover thesameperiod.Tomeetthisrapidlygrowingsecondaryoutput, theUniversityofPuertoRicohadexpandeditsfresmanintake fivetimes,althoughitsoverallexpansionhadbeenonlythree-fold. In1960-61,about43.5percentofdayhighschoolgraduateswere distributedamongstallthecollegesanduniversitiesintheisland, comparedto39.7in1950-51.Itisexpectedthatwiththerecent organization of a programme of juniorcollegescovering the wholeofPuertoRicotherewillbeadefiniteimprovementinthe accommodationofsecondarygraduates.Meanwhile,theproportionofintendingstudentsrejectedbythestateuniversityhadbeen increasing,andin1959-60amountedto54percentofallapplicants(5,417refusalsoutof10,021applications).However,college attendancebysexconfirmswhathasalreadybeenindicatedearlier inthischapter,namely,theequalizingtendencybetweenmales andfemalesinthepursuitofeducation.In1960-61,50.6percent ofuniversitystudentsweremalesand49.4percentfemales,or 17and15percentoftherespectiveage-groups.

TheUniversityofPuertoRicowascreatedbyanactofthe InsularLegislaturepassedonMarch12,1903,"toprovidetheinhabitants,assoonaspossible,withthemeansof acquiring a thoroughknowledgeofthevariousbranchesofliterature,science, and useful arts"i.Thelawfurtherspecified the departments whichshouldcompriseit,tobeorganized"assoonasthenecessaryallocationswereavailable" Z, andalsoprovidedforsuch others,"germanetoawell-equippeduniversity,astheboardof trusteesmayfromtimetotimebeabletoestablish" 3

Thefirstofthedepartmentstobeorganizedwasthenormal school,offeringatwo-yeartrainingcourseforteachers.Thiswas followedbytheAgriculturalDepartmentin1904,theLiberalArts Collegein1910,LawandPharmacyin1913,TropicalMedicine in1924,BusinessAdministrationin1926, andSpanishStudies in1927.

Fromtheirinceptionto1940,these academicdepartments underwentfundamentaladministrativeandcurriculumchanges whichweshalldescribehere,althoughonlybriefly,bywayof introducingtheperiodunderstudy.

ThenormalschoolwastransformedintoaCollegeofEducation,offeringabachelor'sdegreeinadditiontothetwo-yearnormalcertificate.IntimeotherbranchesbecameattachedtotheCollege,suchastheSchoolofSocialWork,theInstituteofPsycho-

1.AnnualReportoftheCommissioner of Education:1903,p.251. 2.Ibid.,252. 3.Ibid.

logy,theSummerSchool,theExtra-muralandExtensionCourses Division,andvocationalandlaboratoryschools,bothofwhich werenon-collegiate.

TheCollegeofArtsandSciencesstartedwithatwo-year curriculumwhichwasintendedtoleadtoabachelor'sdegreeby anadditionaltwoyearsinUnitedStatesinstitutions,theideabeing thatthestudentswouldthusbeabletocombine"theadvantages ofareasonablecostofeducationwiththeadvancedcultureof theolderuniversitiesinthecontinent" 4 Theplan,however,was misconceived,andafour-yearcourseleadingtoeitherB.S.orB.A. wasdesigned.TheCollegetookforitsprovincehumanities,naturalsciences,andsomesocialsciences.Tothisdegreecurriculum, pre-medicalandpre-lawcourses,andM.A.studiesinbiology andSpanishweresubsequentlyadded.

TheCollegeofPharmacyinitiallyofferedacourseoftwo yearsgearedtotherequirementslaiddownbytheInsularBoard ofPharmacyforthelicensingofpharmacistsintheisland.In1917, theadditionofathirdyeartothecourseofstudyhadabad reception,andin1919boththetwo-yearandthree-yearcourses weresimultaneouslyoffered,theformerleadingtothetitleof GraduatePharmacistandthelattertoPharmaceuticalChemist. In1928,thestudycurriculumwasstandardizedtofouryears, withaB.S.forcompletion.

TheCollegeofBusinessAdministrationwaslaunchedwith afive-yearcourseleadingtoaB.A.andalsodiplomacoursesin secretarialstudies,businessadministration,andaccounting.In 1936thebachelor'scurriculumwasreducedtofouryears.

TheCollegeofLawstartedwithathree-yearcoursedesigned onthebasisoftherequirementsprescribedbytheSupremeCourt fortheadmissionoflawyerstothebar.In1917,thestudyperiod wasincreasedtofouryears,againreducedtothreein1936,but ontopofthethree-year,pre-legalcourseofferedintheCollege ofArtsandSciences,thusraisingthetotalcollegiateworkinlaw tosixyears.In1938,thepre-lawrequirementwasreplacedbya bachelor'sdegreefromeithertheUniversityorany"accredited institution",therebyexpandingthestudyforthelawdegreeto sevenyears.

TheCollegeofAgricultureandMechanicalArtscommenced withapurelyagriculturalcurriculum,intimeincludedinits

4.Idem.,1910,p.39.

offerings,besidesthetwo-yeardiplomacoursesinagricultureand polytechnicscience,degreestudiesinagriculture,sugarchemistry, engineering,andgeneralscience.TheCollegewasoriginallyorganizedinthecampusatRioPiedras,butin1911,itwasmovedto Mayagüez,inthewesternpartoftheisland.

Otherpartsof theUniversityinthepre-1940periodwere theAgriculturalExperimentStation,devotedtostudyandresearch inconnectionwiththesugarindustry;theAgriculturalExtension Service,forfosteringcooperativefarmwork;andtheInstituteof TropicalAgriculture.

ItwillbenotedthatmuchofthetrainingofferedintheUniversityintheinitialstagesofdevelopmentofitsvariousdepartmentswasofanon-collegiatesort.Thiswasinaccordwiththe factthatapplicantswithonlyeightyearsofpreviousschooling wereaccepted.Withtheexpansionofthevariouscurricula,entrancerequirementswereraisedandin1919,ahighschooldiplomashowingatleast12yearsofschoolingwasprescribedfor allintendinguniversitystudents.

Ingeneral,therefore,thetrendintheUniversityhadbeen toeliminatethesub-collegiateformsofinstruction.Allbutthree ofthedepartmentsmentionedintheUniversityLawof1903had beenestablished,e.g.,medicine,architecture,andahospital.

BehindtheadministrativeandacademicchangesintheUniversityofPuertoRicopriortotheperiodselectedforthisstudy, wenoticetwolevelsofinfluence,theeffectsofwhichhavebeen felttothepresentday.Oneisthe"generaleducation"ideawhich wouldguaranteeaminimumofculturalpreparationcommonto allgraduatesoftheUniversity.Theotheristheneedfeltfora freshexaminationandstatementoftheUniversity'seducativerole. Theseweremanifestedintwoseparateinstances.Thefirstwas in1926,followingthecreationoftheofficeof"deanofinstruction", whenitwasdecreedthathenceforthallfirstyearstudentsin theCollegeofLiberalArtsandEducationshouldtakegeneral coursesincontemporarycivilization,integratedscience,Spanish, English,musicandartappreciation.Adecadeafterwards,Dr.Juan B.Soto,ChancelloroftheUniversityfrom1936to1941,enunciatedhisobjectivesfortheUniversitywhichinphilosophicalterms identifieditsroleinauniversal,humanisticcontext.Incommon withotherinstitutionsofhigherlearning,itssightsmustbedirectedto"theeducatedman"withanunderstandingofhisplace insocietybothascitizenandman.Itshouldcultivatethestatesman, the legislator, the judge onwhom"public prosperity

andindividualhappinessaresomuchtodepend" 5. Itshouldbe "inapositiontoassistthegovernmentoftheislandinstudying andsolvingthedifferentproblemswhichitiscalleduponto confront"s.Thusbesidessubjectsofapurelyculturalnature,the Universityshouldoffercoursesinpoliticalandsocialscience.

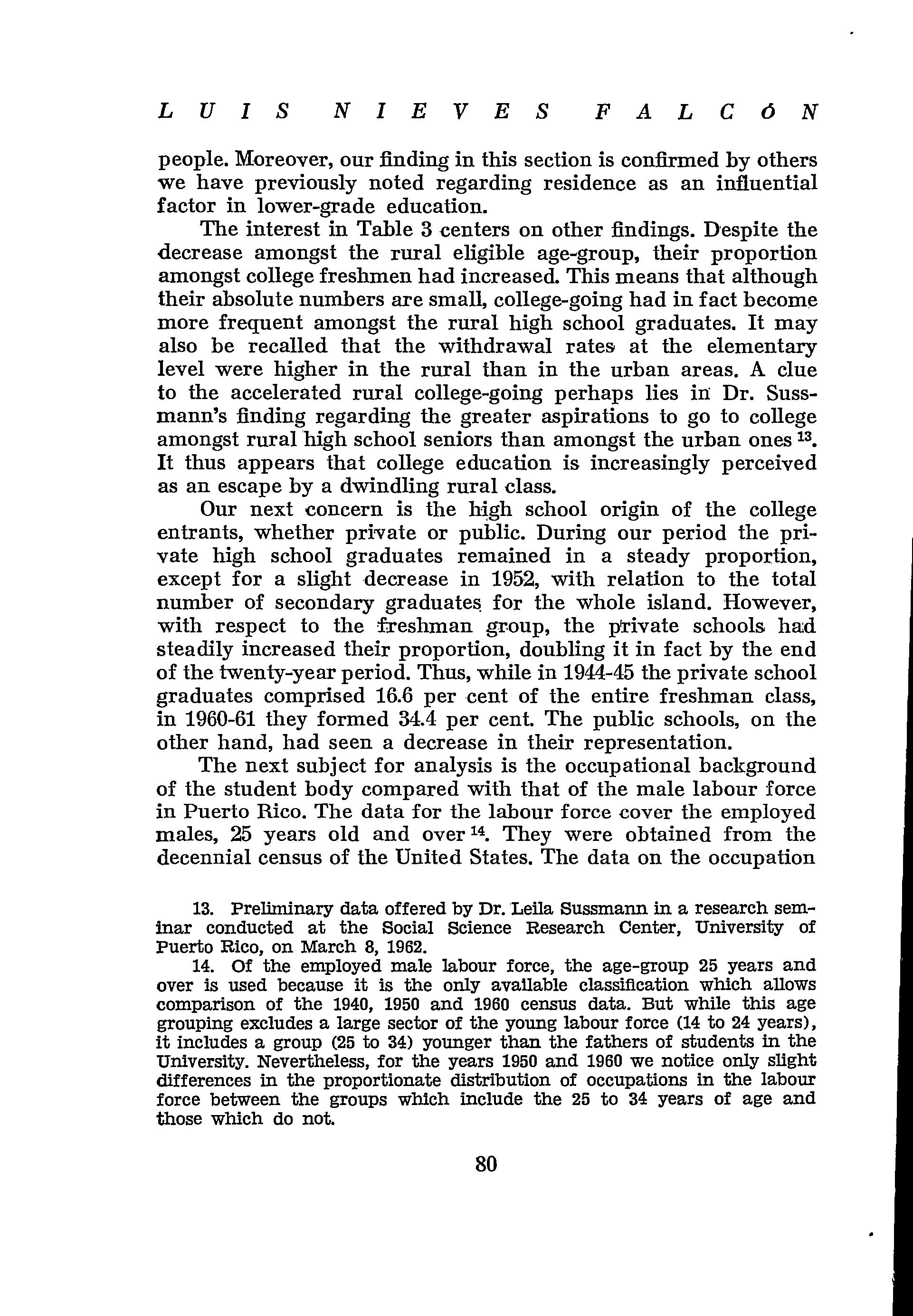

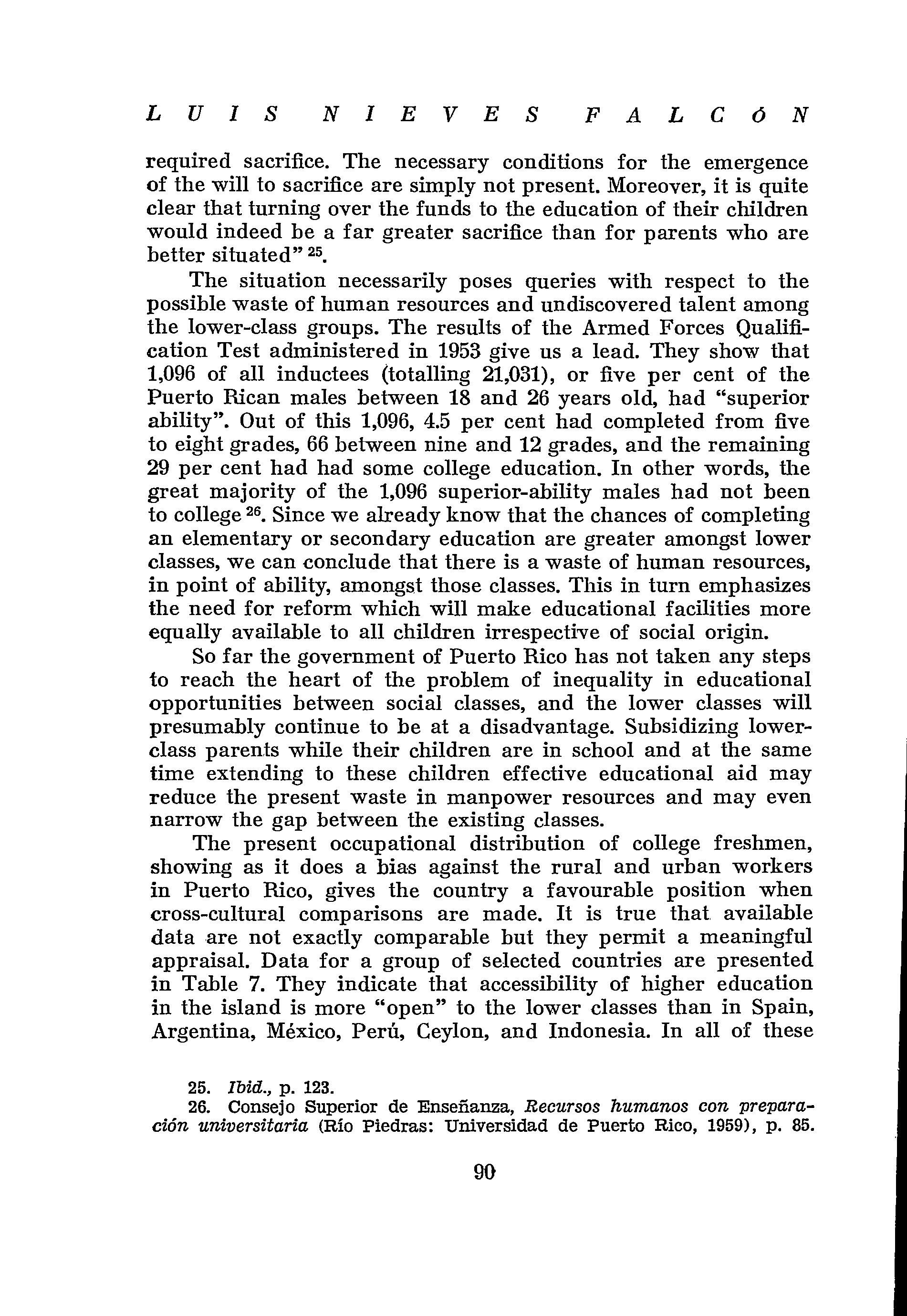

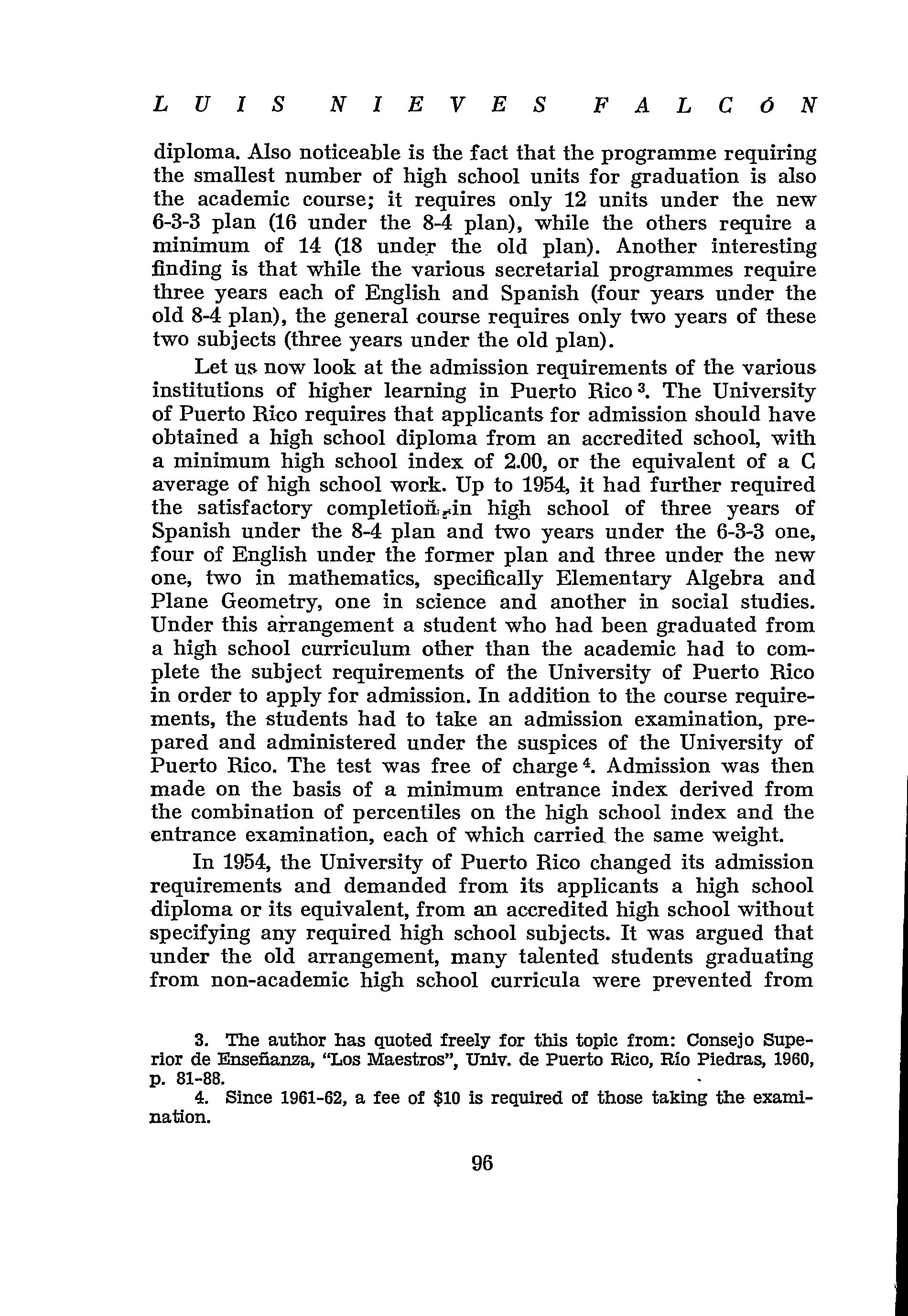

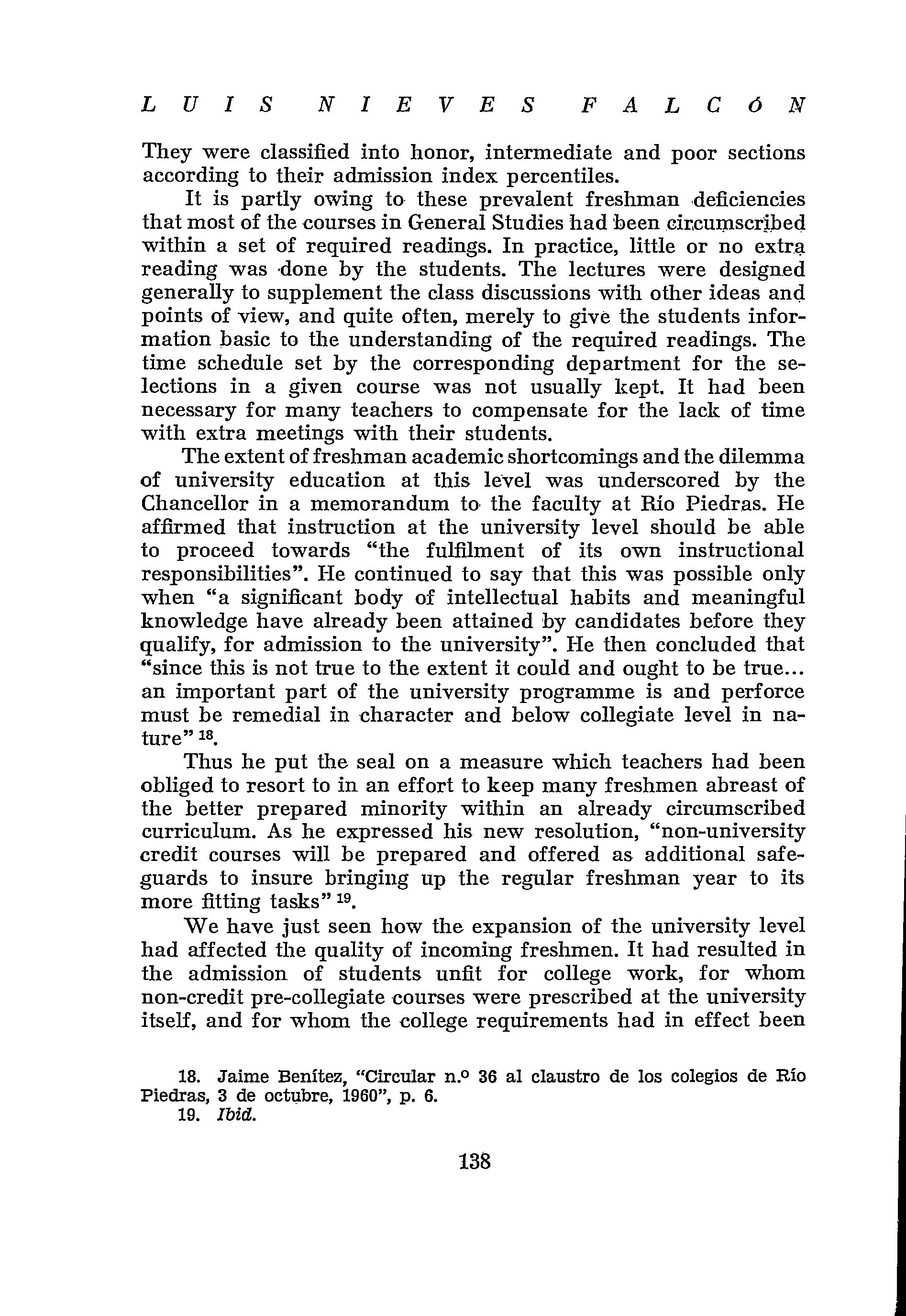

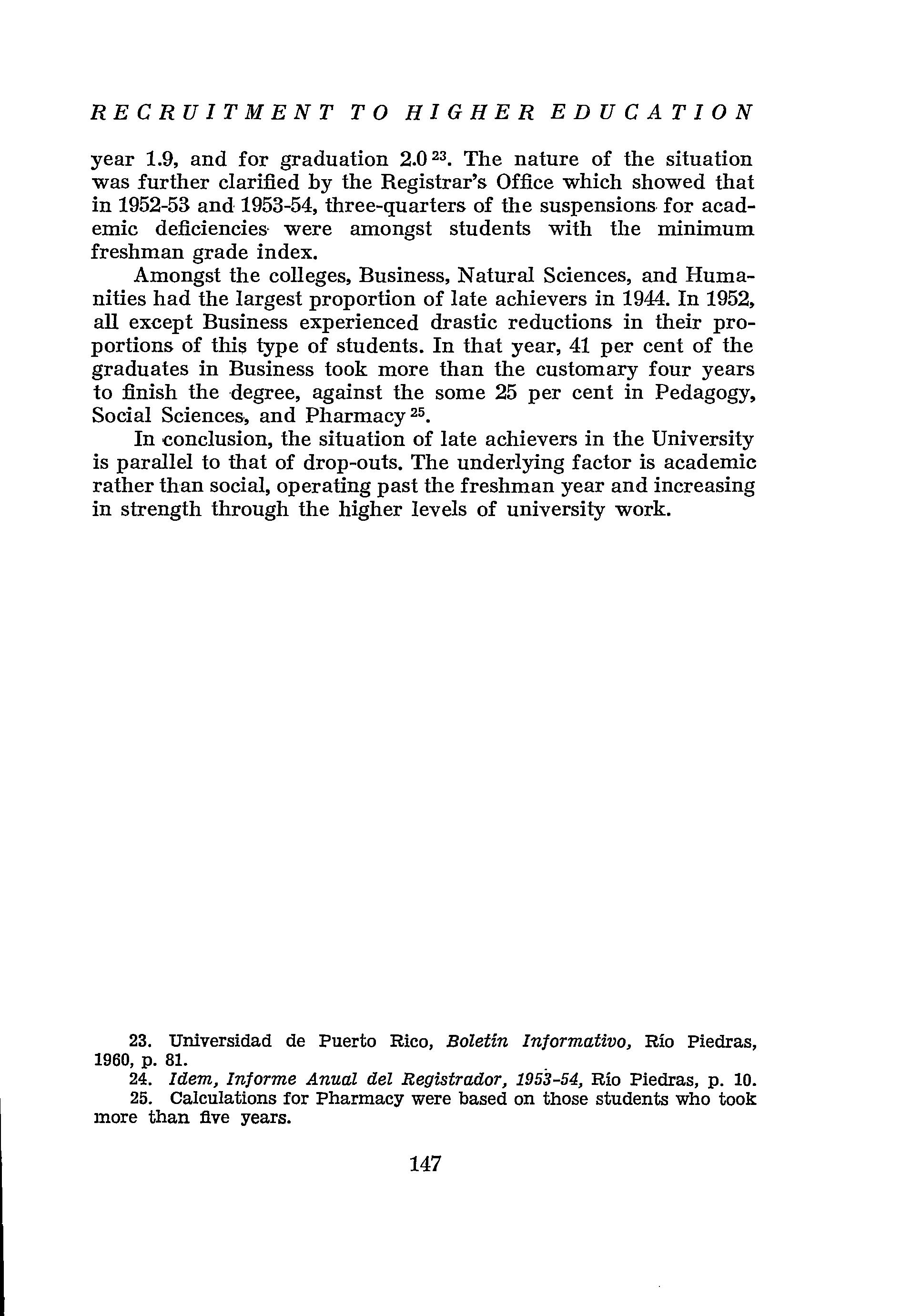

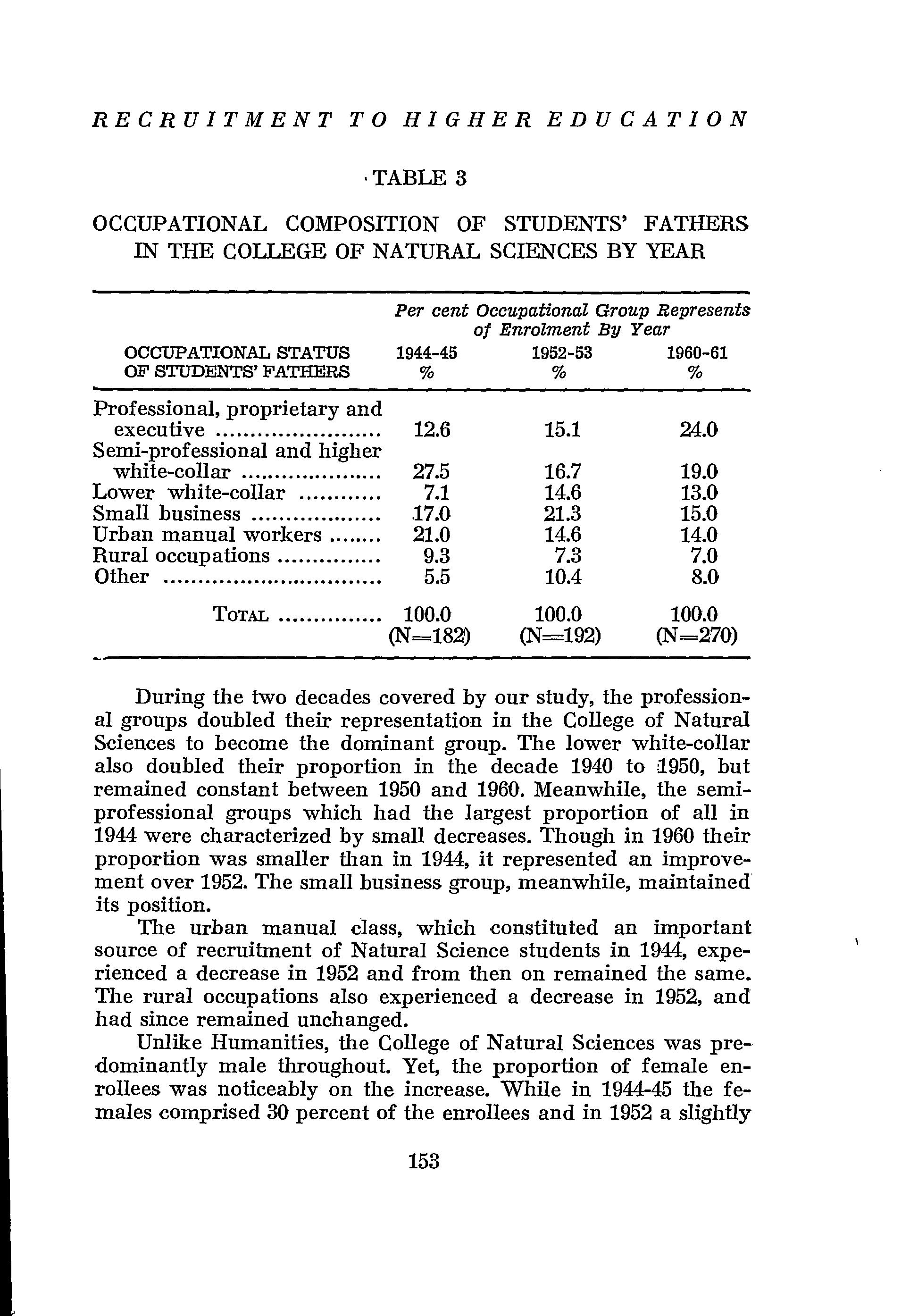

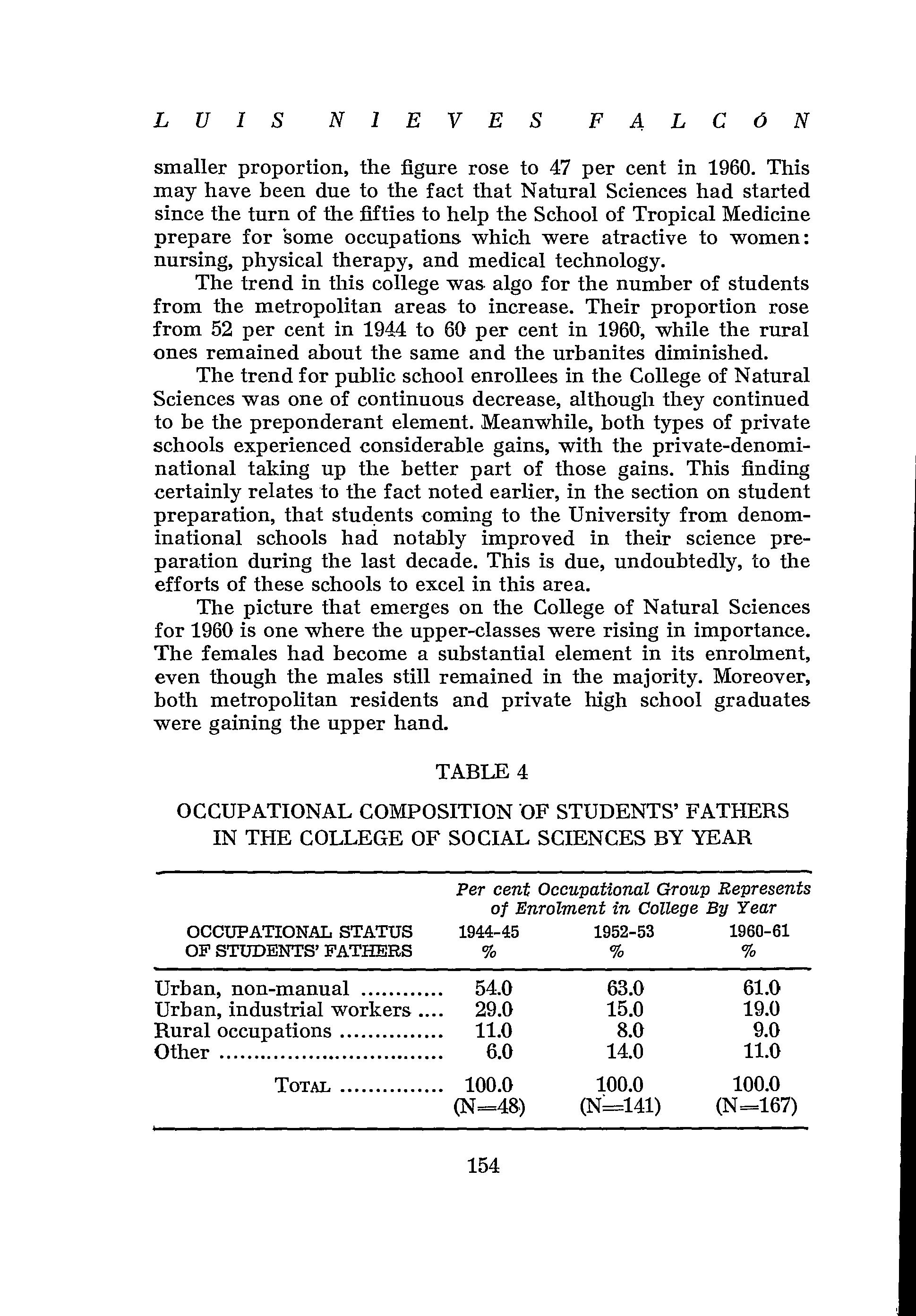

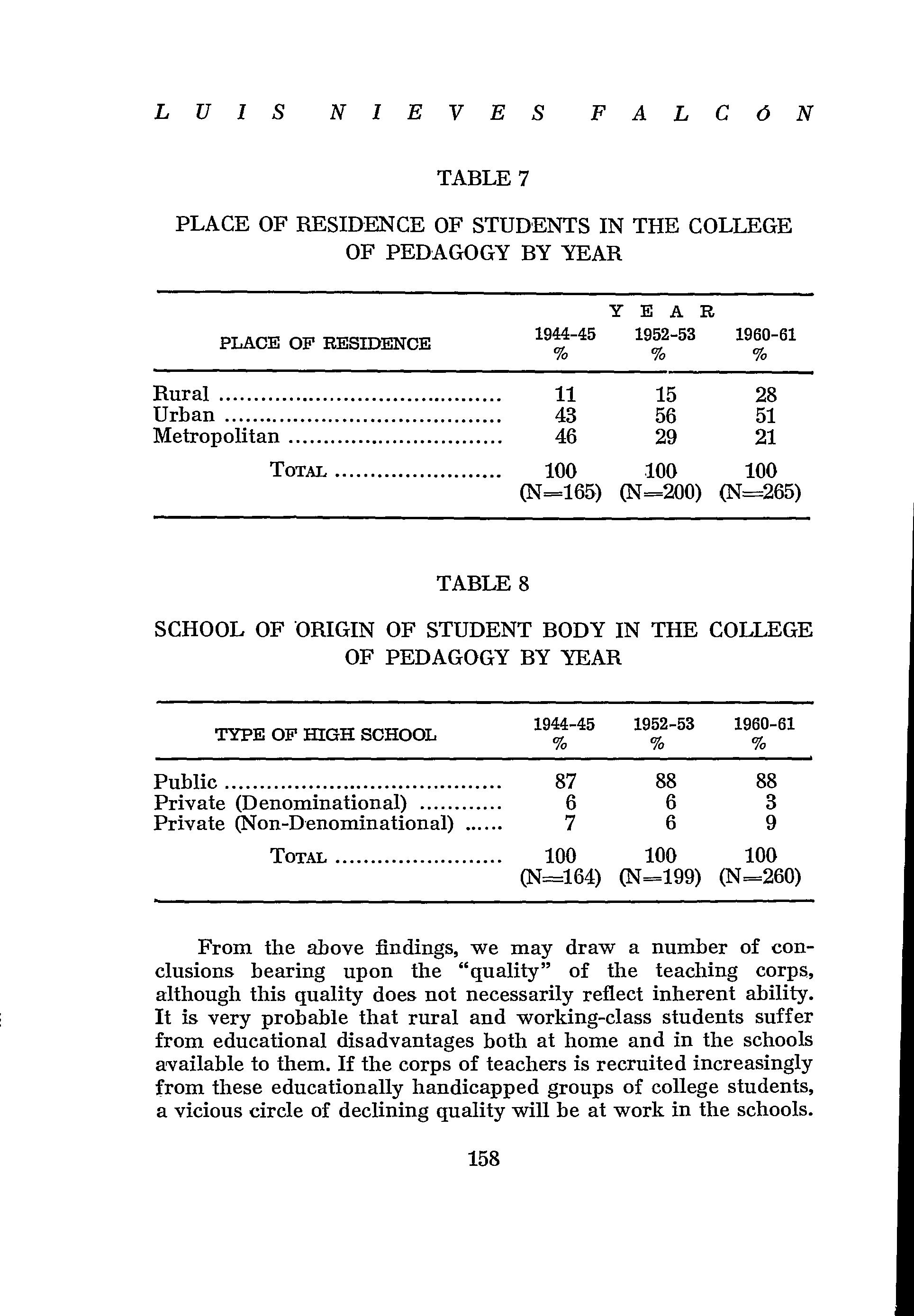

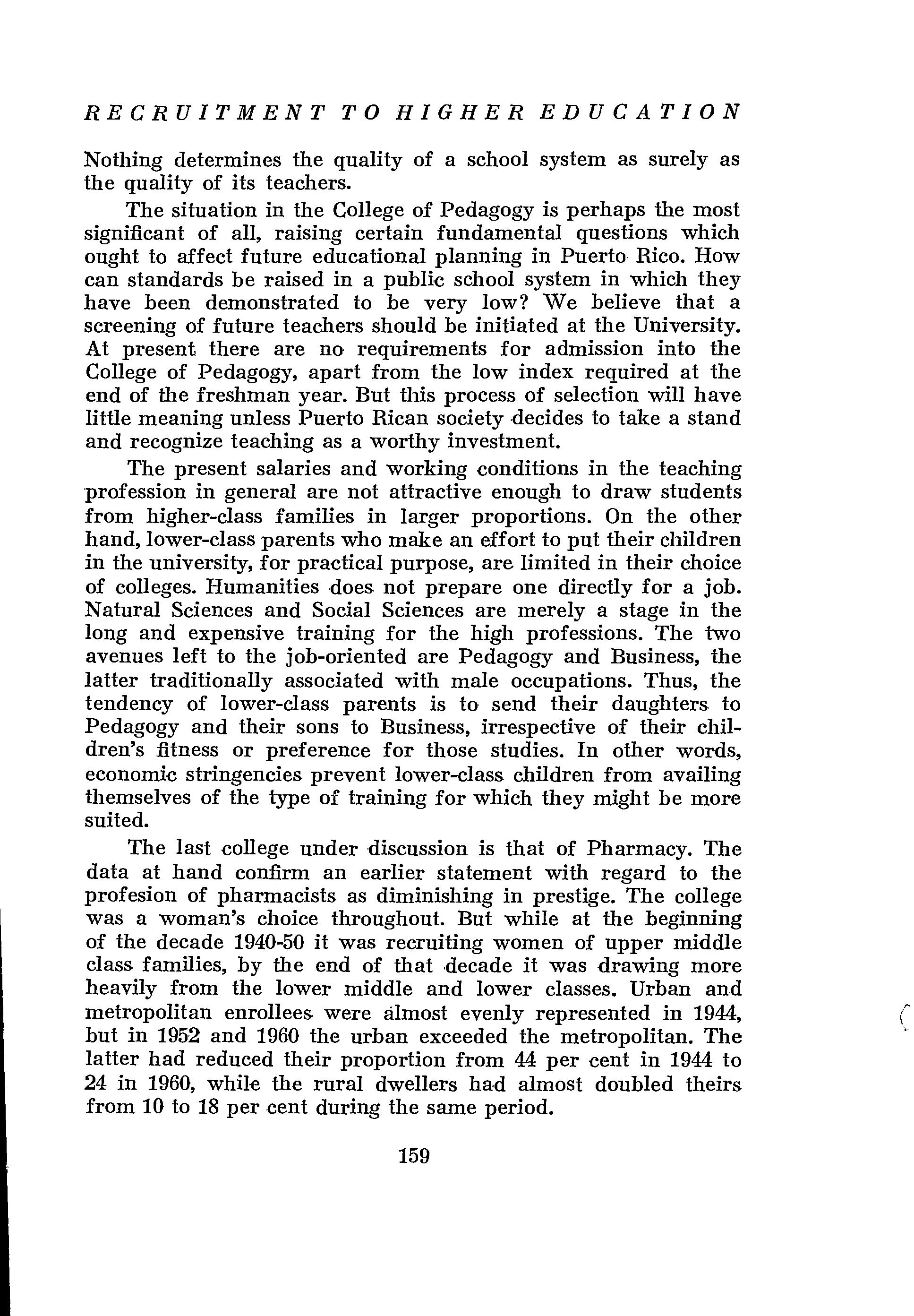

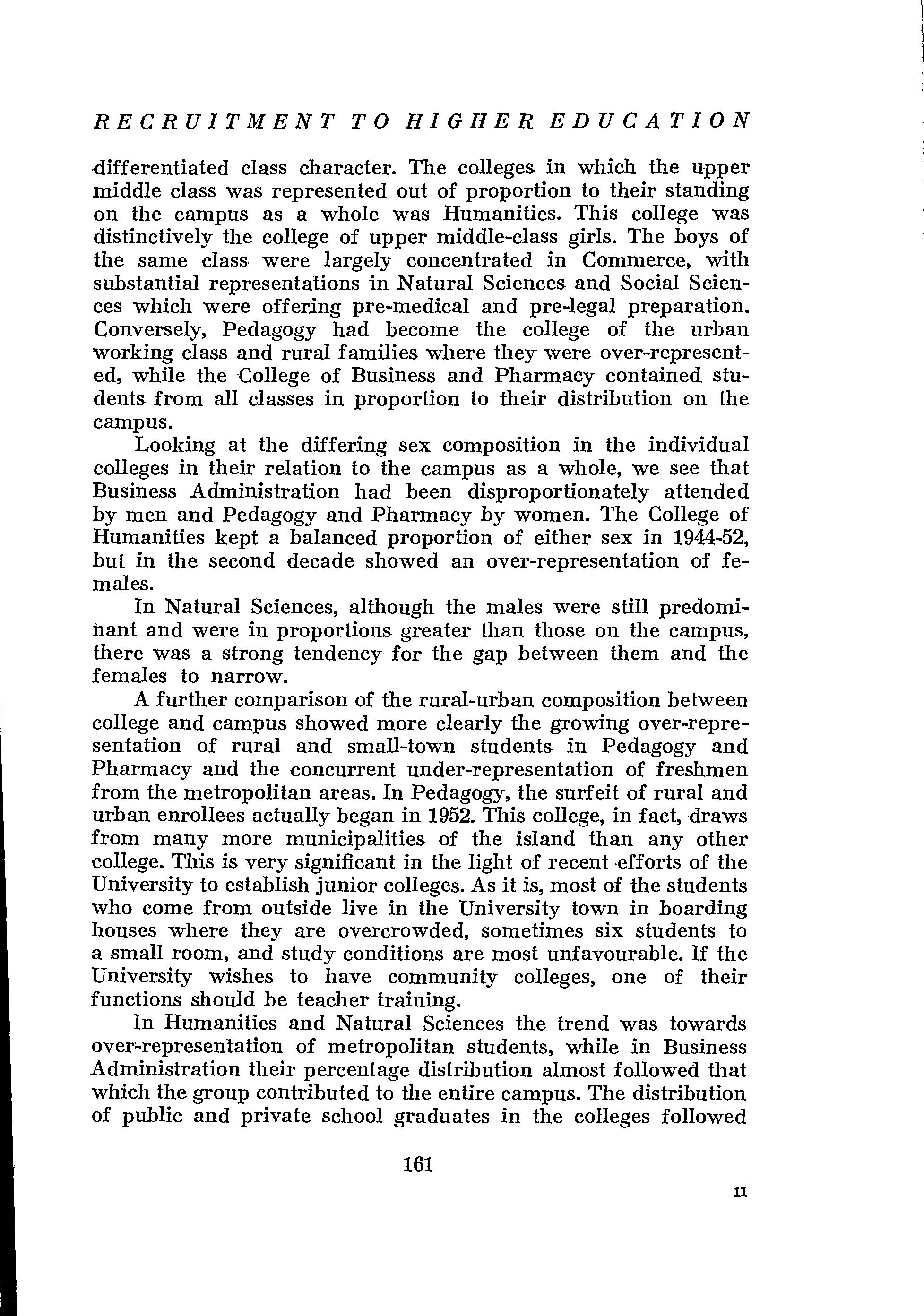

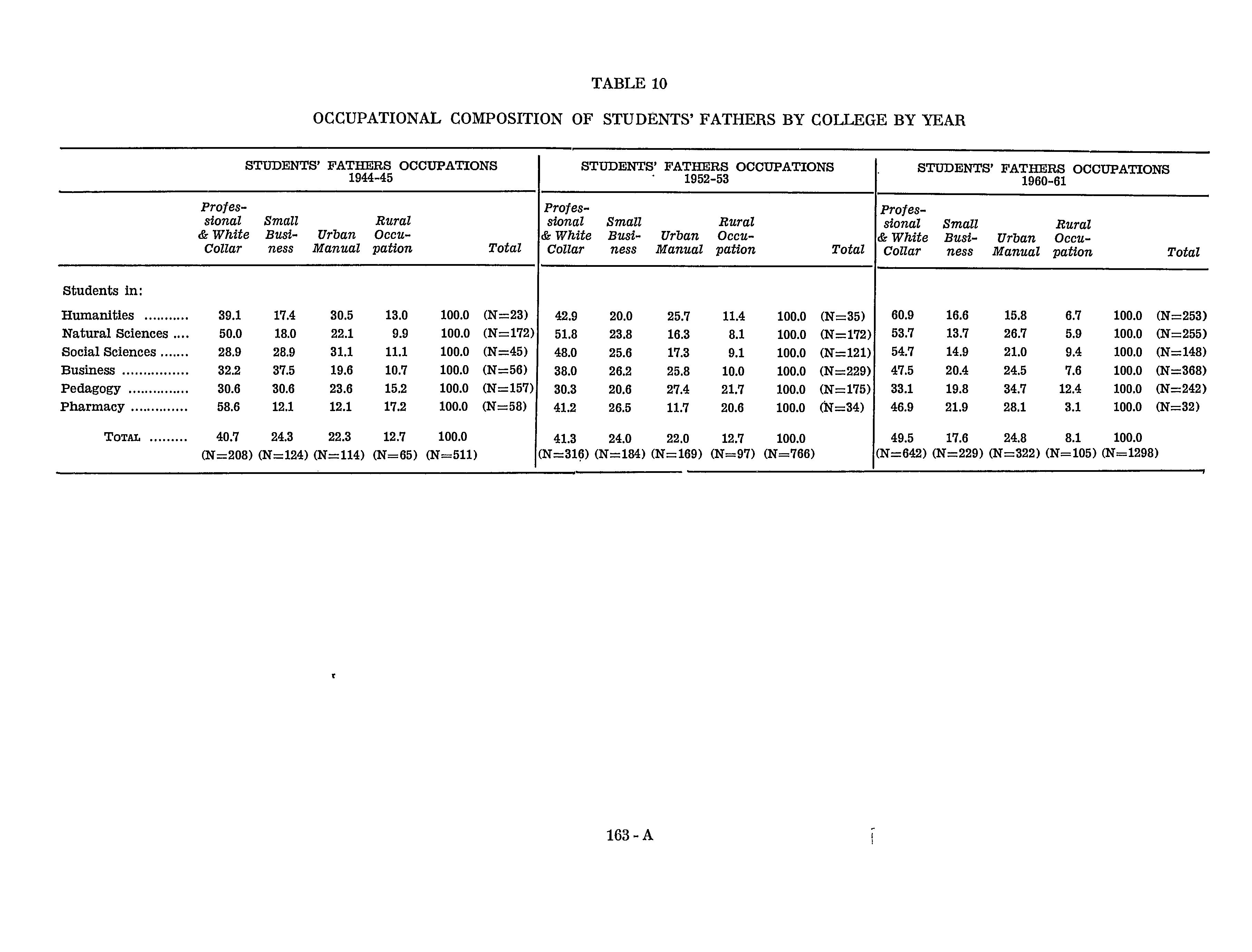

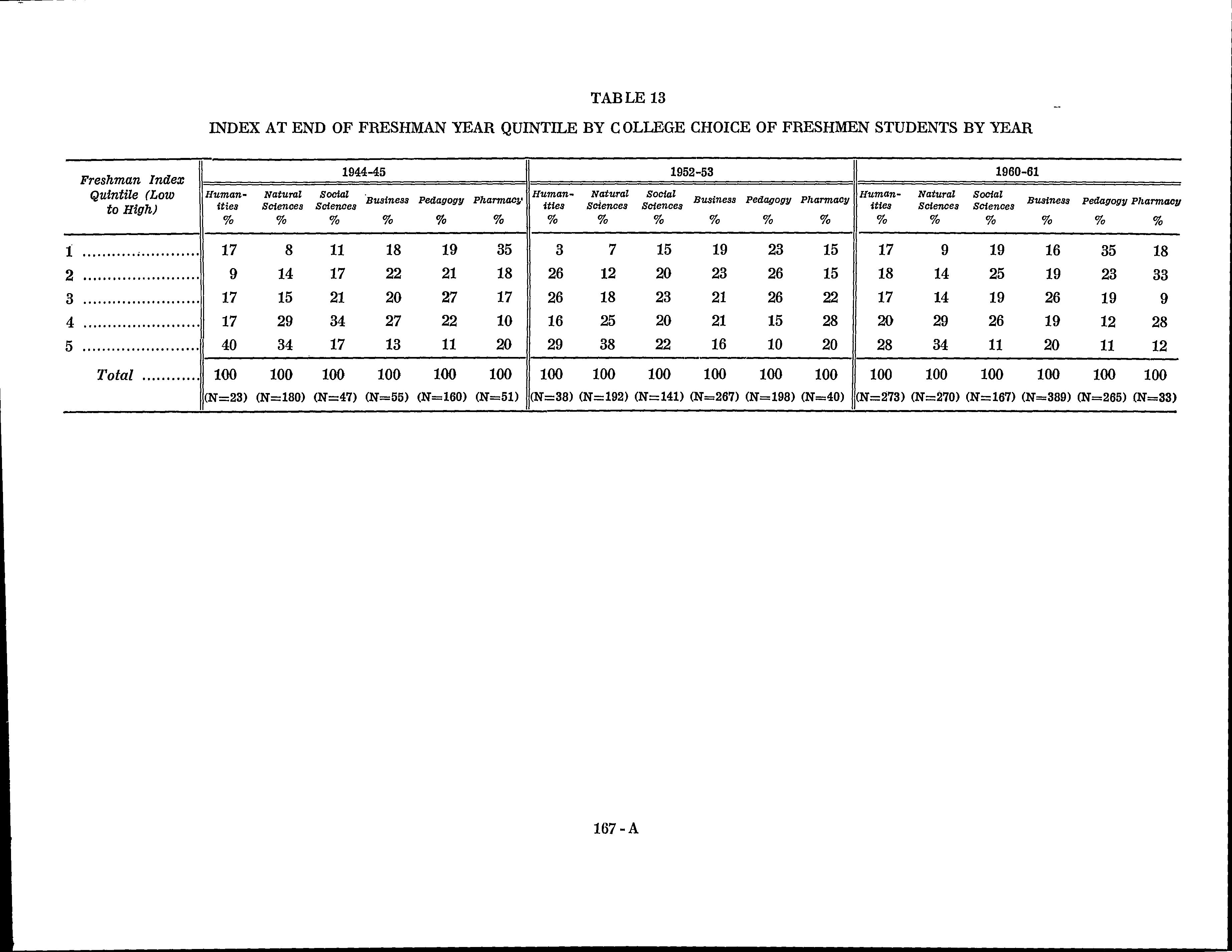

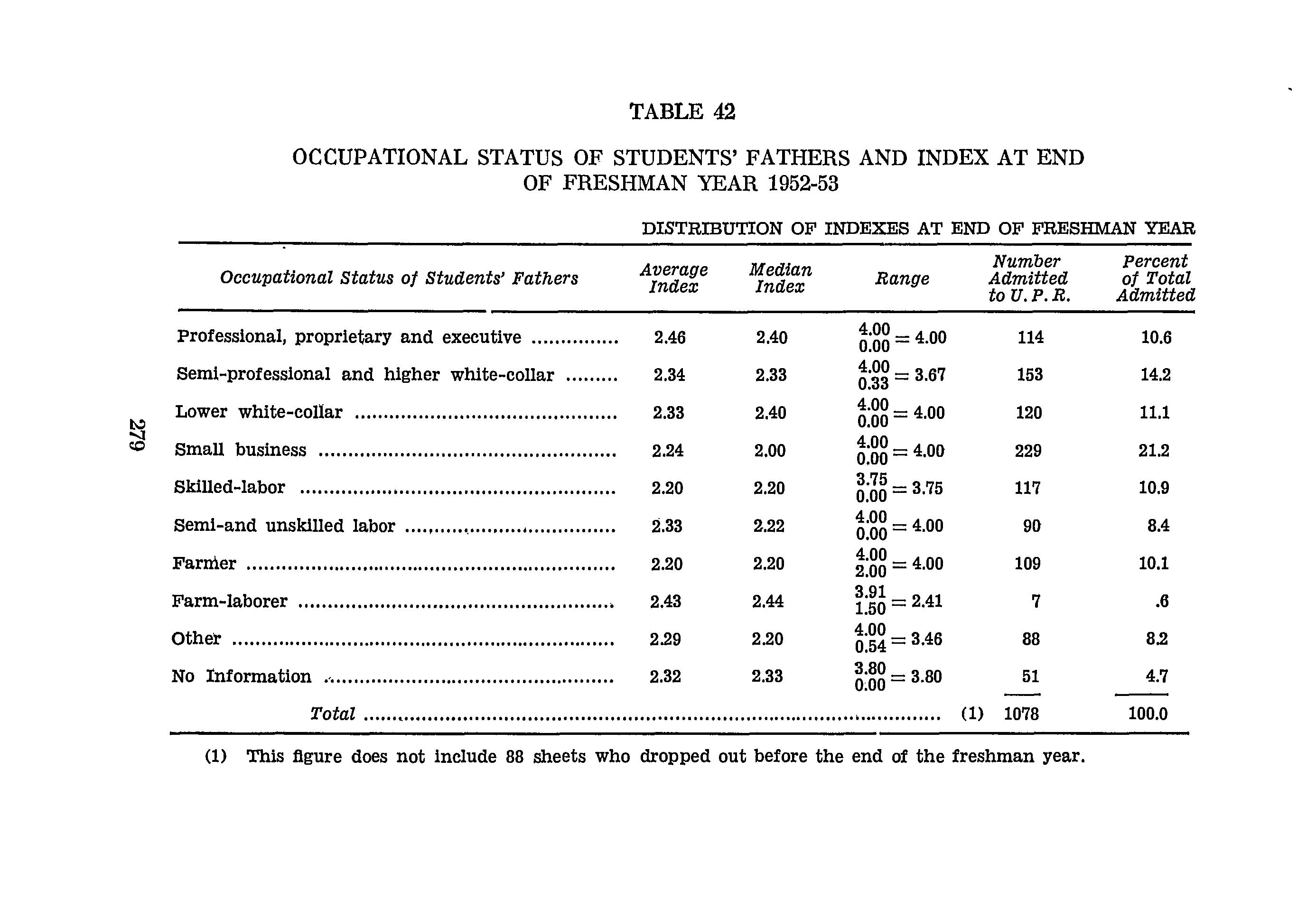

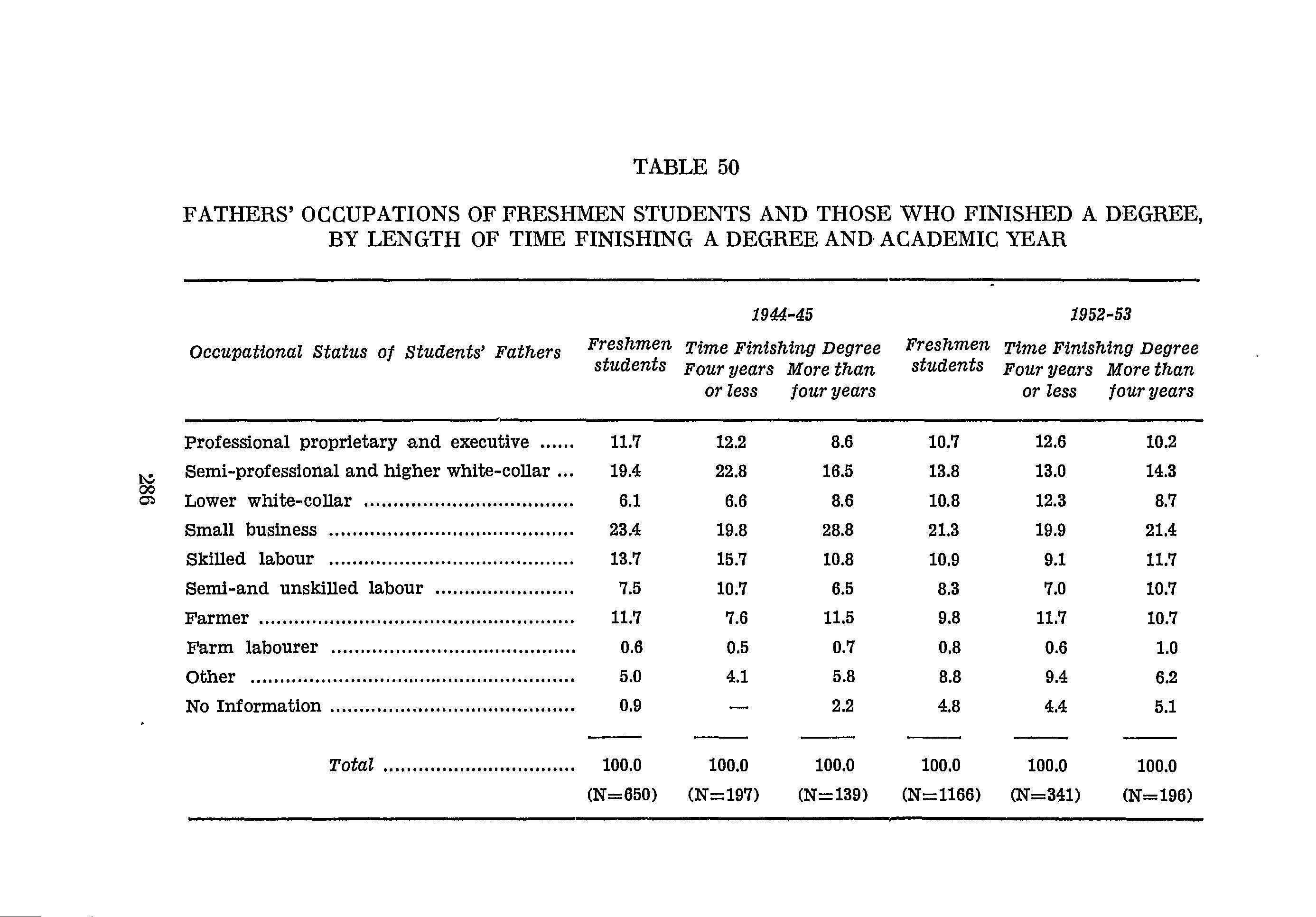

Theyear1946wasmarkedbytheadventtopowerofthe PopularDemocraticParty,committedtoexpandeducationalfacilitiesatalllevelsandtoprovideallsegmentsofthepopulation, especiallythe"lessprivileged",withequalopportunitiesforobtainingeducation.TheproductofthispolicywasanewUniversityLaw,commonlyknownastheReformLawof1942.Ithassince remainedthecharterofthestateuniversity,unalteredthrough theyears.