Haematological Conditions in General Practice

Chair: A/Prof James Morton AM

Director of Haematology

Icon Group

Chair: A/Prof James Morton AM

Director of Haematology

Icon Group

Lymphoma

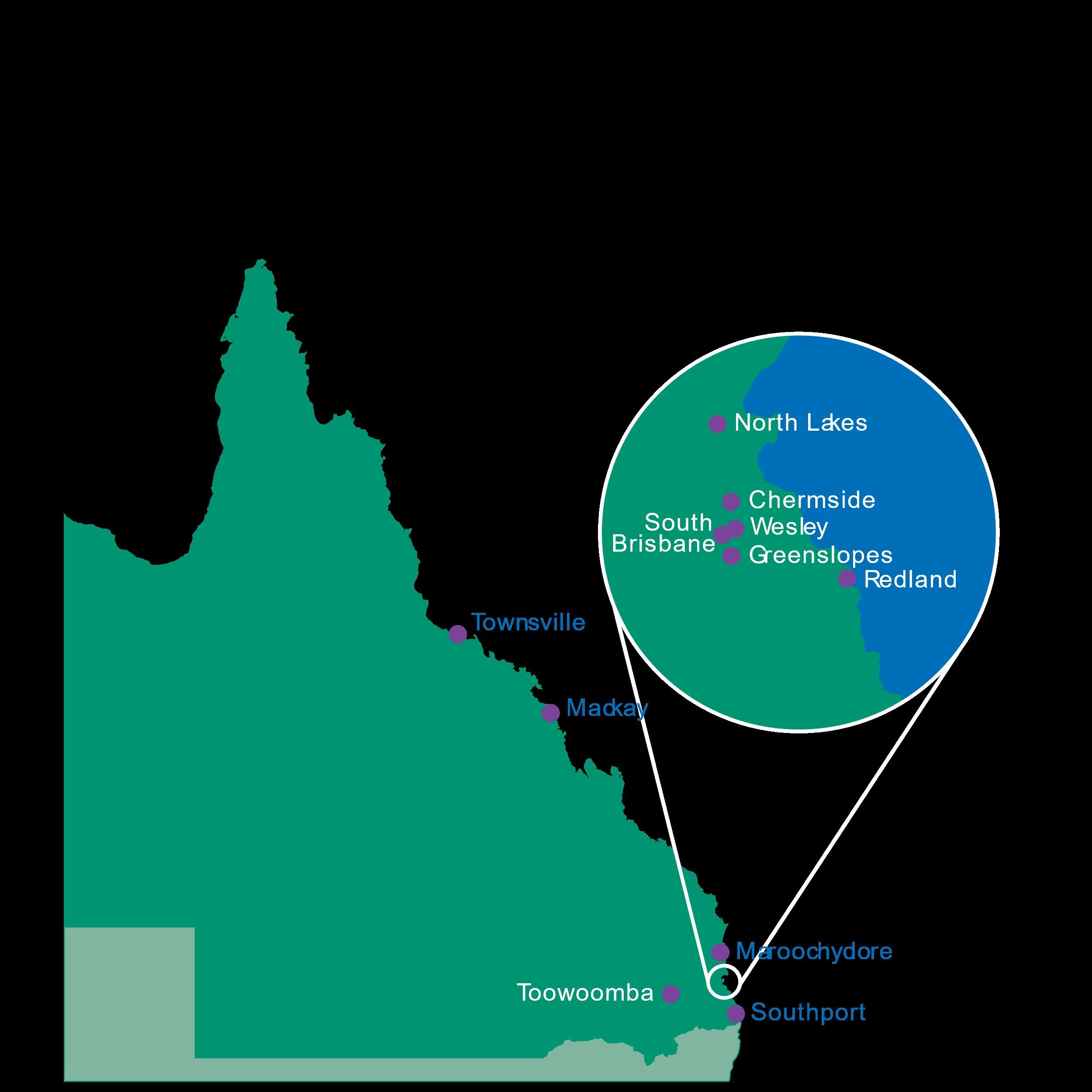

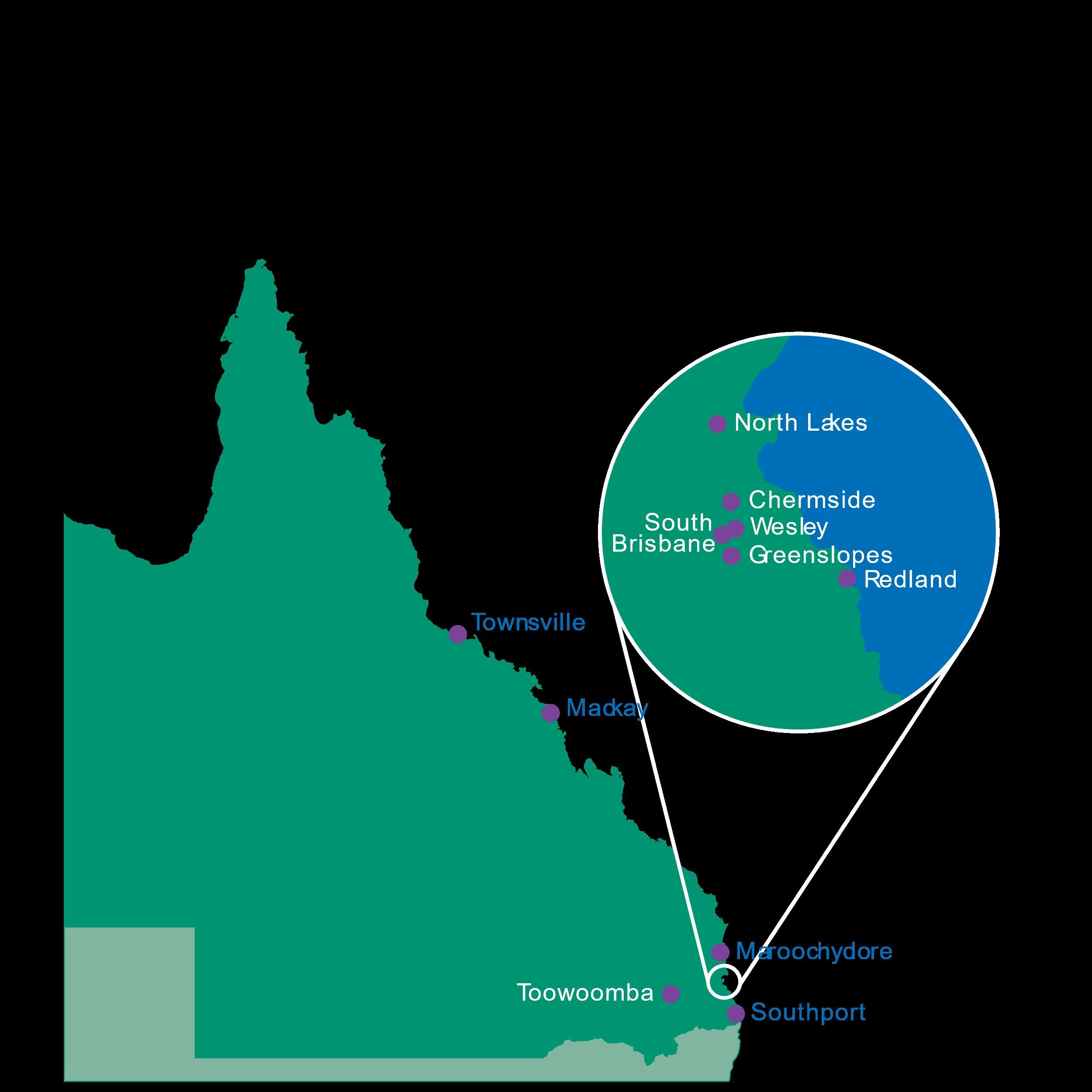

With a network of more than 40 clinical haematologists, day oncology centres across the state, outreach clinics in remote and regional areas and telehealth services, Icon Cancer Centre is committed to delivering the best possible care for all patients in Queensland.

Icon Cancer Centre sites

• Townsville

• Mackay

• Maroochydore

• Toowoomba

• North Lakes

• Chermside

• Wesley

• Greenslopes

Satellite and outreach clinics

• Cairns

• Rockhampton

• Bundaberg

• Hervey Bay

• Maryborough

• Warwick

• Tarragindi

• Sunnybank

• Redland

• South Brisbane

• Southport

• Ipswich

• Springfield Central

• Benowa

• Tugun

IconDoctorApp.com is a dedicated secure referral and online education platform created exclusively for GPs and specialists.

Accessible via desktop and mobile, IconDoctorApp.com provides:

• Expedited secure referrals

• Haematology and oncology RACGP accredited and self-directed online learning

• Event registration and CPD records

• Diagnosis and treatment pathways for referral decision making

To learn more about our new online platform and create your account, visit IconDoctorApp.com

Karthik Nath

MBBS (Hons) BSc FRACP FRCPA PhD

Clinical Haematologist

Deputy Director of Cellular Therapy

Icon Cancer Centre South Brisbane

• Overview of CAR T-cell therapy

• Indications for CAR T-cell therapy in blood cancers

• Unique Toxicities of CAR T-cell therapy

• Future Developments – Immune-effector cell (IEC) therapies

Cappell, Kochenderfer,

CD3 “T-cell marker”

PAX-5 “Lymphoma marker”

CD4 “T-cell marker”

CD8 “T-cell marker”

• Overview of CAR T-cell therapy

• Indications for CAR T-cell therapy in blood cancers

• Unique Toxicities of CAR T-cell therapy

• Future Developments – Immune-effector cell (IEC) therapies

CAR T-cell therapy is approved for use in relapsed/refractory blood cancers.

Inpatient (Kite, Gilead)

Inpatient (Kite, Gilead)

Outpatient (Novartis)

Outpatient (BMS)

Inpatient (BMS)

Outpatient (J&J)

• r/r CLL or MCL ≥ 2 prior lines (2024)

MM after ≥ 2 lines of therapy (2024)

MM after ≥ 1 line of therapy (2024)

Cappell, Kochenderfer, Nat Revs Clin Oncol, 2024 (modified)

BCMA-directed CAR T-cell therapy

Trial No. of patients

ORR %

• Overview of CAR T-cell therapy

• Indications for CAR T-cell therapy in blood cancers

• Unique Toxicities of CAR T-cell therapy

• Future Developments – Immune-effector cell (IEC) therapies

• Phase 1. CAR T-cell trafficking to tumor site

• Phase 2. CAR T-cell activation/proliferation; cytokine production; activation of endogenous immune cells

• Phase 3. ↑ cytokines → systemic inflammatory response

• Phase 4. Diffusion of CAR-T, cytokines, activated monocytes into CSF (ICANS)

• Phase 5. Resolution phase

Nature Reviews, 2022

• Overview of CAR T-cell therapy

• Indications for CAR T-cell therapy in blood cancers

• Unique Toxicities of CAR T-cell therapy

• Future Developments – Immune-effector cell (IEC) therapies

Gastric adenocarcinoma Auto CAR T-cell Claudin 18.2

Renal cell carcinoma Allo CAR T-cell CD70

Prostate cancer Auto CAR T-cell PSMA

Gastric adenocarcinoma Allo NK T-cell -

Synovial sarcoma TCR T-cell -

Melanoma TIL -

Melanoma + lung cancer IL15 secreting TIL -

Mesothelioma Auto CAR T-cell Mesothelin

Auto, autologous; allo, allogeneic; TCR, T-cell receptor; TIL, tumor infiltrating lymphocyte

Largest provider of ASCT in Queensland Favorable survival outcomes with ASCT compared to national registry data

ASCT, autologous stem cell transplant

Icon Cancer Centre

Ian Irving

James Morton

Kerry Taylor

Jason Butler

Simon Durrant

Icon Cellular Therapy Lab

Debra Taylor

Icon Cancer Foundation

Leanne Hardymann

Icon Group – Research

Icon Pharmacy

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, NYC

Jae Park

Sham Mailankody

Translational Research Institute

Maher Gandhi

QIMR Berghofer

Steven Lane

Dr. Ross Tomlinson – Hematologist

Icon Cancer Centre Wesley

Icon Cancer Centre Chermside

Outline the differences between plasma cell disorders

Classify plasma cell and platelet disorders through clinical diagnosis Implement evidence-based patient management of plasma cell disorders

Summarise the relationship between monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) and blood cancers or other serious diseases

Progressive fatigue

Constipation

Progressive lower back pain for approximately 3 months

Pre malignant monoclonal gammopathies

• MGUS

Malignant monoclonal gammopathies

• Smouldering multiple myeloma (MM)

• Multiple myeloma/Plasma cell leukaemias

• Solitary plasmacytomas

• Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia

Signs

Unexplained anaemia

Renal impairment

Neuropathy

Restrictive heart failure

Lytic lesions on imaging

Unexplained osteoporosis

Lymphocytosis

Other cytopenias

Symptoms

Fatigue Increasing bone pain (pelvis/hips/lower back)

Weight loss

Fevers Increased infections (e.g. sinus, pneumonia

Surprisingly very little!

Occasionally pts will have hepatosplenomegaly

“Classic signs” of amyloidosis

• Macroglossia

• Periorbital ecchymosis

Serum protein electrophoresis (should include an immunofixation)

• Will detect whole immunoglobulin e.g. an IgG, IgA etc.

Necessary companion tests

• Serum free light chains

• Immunoglobulins

⚬ Will allow the measuring of normal/residual globulins (can be helpful if associated hypogammaglobulinemia)

GP Driven investigations

• FBC, chem20, coagulation studies

• SPEP, SFLC, immunoglobulins

• Urine not essential unless thinking about amyloidosis (e.g. weight loss, fluid retention, cardiac sx)

Haematologist driven investigations

Skeletal imaging:

• Low dose whole body CT scan OR whole body MRI OR CT/PET

BMAT:

• useful for quantifying plasma cells/detection of amyloidosis

Mr. AM

MSKCC – Multiple Myeloma information

What is the significance of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance? Catherine Atkin, Alex Richter, Elizabeth Sapey Clinical Medicine Oct 2018, 18 (5) 391-396; DOI: 10.7861/clinmedicine.18-5-391

Approx 5% over the age of 60

Increases as age increases ~10% over age 85

Can be found incidentally Needs risk stratification and appropriate referral May need further/companion tests (e.g. BMAT, imaging)

Rajkumar SV et. al. Serum free light chain ratio is an independent risk factor for progression in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Blood. 2005 Aug 1;106(3):812-7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1038. Epub 2005 Apr 26. PMID: 15855274; PMCID: PMC1895159.

B symptoms

• fevers, night sweats, weight loss

Significant bone pain

Peripheral neuropathy

Amyloidosis related sx:

• Sx of cardiac failure (e.g. lower limb oedema, decreasing exercise tolerance, easy bruising)

IgG paraproteins

• if <10g/L – I will generally observe and NOT BMAT or skeletal image

• if >10g/L – I will BMAT and skeletal image

IgM paraproteins

• more often associated with lymphomas, than myelomas

• BMATs are informative –will pick up a B cell lymphoma

• PET scan often better to image for adenopathy/liver/splenomegaly

IgA PP

• I will always image and BMAT as level poorly correlates with disease burden

Stern S et al. the Haemato-Oncology Task Force of the British Society for Haematology and the UK Myeloma Forum. Investigation and management of the monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Br J Haematol 2023; 202(4): 734–744. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.18866

At the start I check q3-4 months to get a feel for its tempo

If after 1 year its stable – can go to checking it q6-12/12

Frequency of monitoring can change if there is a change in protein (e.g. more frequently if paraprotein increases)

Any concern re: development of symptoms should trigger a review by Haematologist

Malignant condition

Significant plasma cell burden but no SLIM-CRAB criteria

Requires closer observation than MGUS

Approx 0.5% of adults >40

Prevalence increases with age

• 1.08% over age 70

• 1.59% over age 80

Hughes D et. al. Diagnosis and management of smouldering myeloma: A British Society for Haematology Good Practice Paper. Br J Haematol. 2024 Apr;204(4):1193-1206. doi: 10.1111/bjh.19333. Epub 2024 Feb 23. PMID: 38393718.

FBC, chem20, SPEP, SFLC, immunoglobulins

Skeletal imaging

• Low dose whole body CT, MRI, or CT-PET

Bone marrow aspirate and trephine

• Accompanied cytogenetic evaluation and flow cytometry

Multiple risk scores available

• Mayo 20-2-20

• IWMG 20-2-20 with FISH

Risk is generally based on plasma cell burden, size of paraprotein, and FLC assay results

Consideration given to reevaluating patients over time

Skeletal imaging repeated for monitoring

These patients require ongoing haematologist follow up

Increasing age of population

Pts with myeloma are living longer

Average life expectancy gone from 3 years >10 years

Same workup for previous states

Extra components are prognostic (e.g. cytogenetics)

Treatment should be aimed at

• Maximizing depth and duration of response/remission

• Minimizing toxicity

• Improving QoL and lengthen overall survival

• Alleviate symptoms

• Prevent further organ damage

Sive J et. al. British Society of Haematology. Guidelines on the diagnosis, investigation and initial treatment of myeloma: a British Society for Haematology/UK Myeloma Forum Guideline. Br J Haematol. 2021 Apr;193(2):245-268. doi: 10.1111/bjh.17410. Epub 2021 Mar 21. PMID: 33748957.

Adjustment for frailty/frailty assessment

• Disease of the elderly

• Myeloma therapy doses can, and should, be adjusted depending on age/frailty scores

Transplant eligibility

• Recommended for younger, fitter pts

• Selected pts >70 can be considered for autologous transplantation

Patient and clinician preference

• Variability and breadth of choice for oral therapies, subcutaneous and IV therapy based on line of therapy/stage of disease

Treatment paradigms

• 2 drugs better than 1, 3 drugs better than 2

• Always looking to combine therapies

• First remission is always the longest, with then diminishing returns

Fit patients

• Velcade based chemotherapy (VRD)

• Stem cell transplantation

• Maintenance lenalidomide

Frail/Less fit pts

• Velcade based treatment (e.g. VRD-lite, VCD) or Imid based therapy

Choose the right therapy for the right patients – very individualised care.

Generally progress through available options depending on patient risk, disease presentation, comorbidities etc.

Options:

• Proteosome inhibitors (Bortezomib, Carfilzomib)

• Immunomodulatory medications (e.g. Lenalidomide, Pomalidomide)

• Monoclonal antibodies (e.g. Daratumumab, Elotuzumab)

Future of myeloma is bright – but not cured yet

• bacteria, viruses etc.

Prophylactic antibiotics for PCP (resprim) and shingles (Valtrex)

Monthly IVIG for hypogammaglobulinemia

Secondary cancers skin cancers, breast, bowel, colon etc.

Bone health

1-3 monthly zometa

Metabolic complications

Sive J et. al. British Society of Haematology. Guidelines on the diagnosis, investigation and initial treatment of myeloma: a British Society for Haematology/UK Myeloma Forum Guideline. Br J Haematol. 2021 Apr;193(2):245-268. doi: 10.1111/bjh.17410. Epub 2021 Mar 21. PMID: 33748957.

Vaccinations – COVID-19, pneumococcal, shingles, influenza

Mgmt of chronic comorbidities

Skin checks

Survivorship – depression/anxiety

Metabolic issues – obesity, T2DM, cholesterol, etc

Can call anytime to discuss cases

Prof Morie Gertz –Mayo Clinic Rochester

Amyloidosis is a group of diseases caused by abnormal deposition in the body of amyloid fibrils, made up of misfolded proteins

Amyloid is derived from the word ‘amylon’ in Greek or ‘amylum’ in Latin, means cellulose or “starch like”

Our genes and our DNA code for the manufacture of small molecules called proteins

Proteins help life’s biological processes antibodies as part of our immune responses to infection hormones that regulate our body’s growth, regulation and organ function

Once produced, proteins naturally fold into a particular shape - The way a protein folds allows for its specific function

When proteins are folded properly, they work as they should - and we enjoy good health

When proteins “kink” or misfold, they may be able to make amyloid fibrils

As we age, protein stability can start to falter

Proteins may kink more easily

If we inherit genetic variation, some proteins mis-fold more easily

If we have inflammation for many years, some proteins mis-fold more easily

Usually our bodies can identify & remove abnormally folded proteins

But sometimes…. we produce too much abnormal protein for our body to handle or we are not able to break down and clean up the abnormal protein at all

Amyloidosis is a protein folding disorder

The misfolded protein (amyloid) takes on a shape that makes it difficult for the body to break down

These amyloid proteins link together to form rigid, linear “fibrils”

- accumulate in organs and tissues

- causing damage and organ failure with time

Fragments

Normal TTR Tetramer

TTR circulates as a “4 leaf clover” or a “flower”

Individual proteins misfold

“Leaves” fall off the flower as we age “Leaves” mis fold or kink

Quintas et al. J Biol Chem 2001;Johnson et al. JMB 2012; Marcoux et al. EMBO Mol Med 2015; Bulawa et al. PNAS 2012

Stick together Aggregate abnormally

Misfolding allows the leaves to stick together

Then they arrange into very hard amyloid fibrils that deposit between cells and tissues abnormally

“Rare” condition

~300 Australians are estimated to develop AL each year

Up to 3000 Australians are thought to have TTR

We have been under diagnosing

New tools (modern echo with strain imagining) and cardiololgist awareness

2023: QLD Amyloidosis Centre are getting 400+ referrals of confirmed Amyloidosis

Number of TTR referrals to VTAS since mid-2014

Production of excessive amount of immune light chains

eg. MGUS or Multiple myeloma – AL

Family history of amyloidosis

ie. genes produce proteins that more easily misfold – Hereditary

Chronic infection/inflammatory disease

eg. Crohn’s disease, recurrent infections – AA

Ageing - TTR

Lousada et al. Adv Ther. 2015;32(10):920-8.

Common sites include

Bladder

Airway (trachea, lungs)

Eye

Gastrointestinal tract

Skin

Breast

Localised amyloid deposits are usually made up of light chains

Similar to systemic AL amyloidosis

However the abnormal light chains are only in the affected tissue, not the bone marrow

Typically an excellent prognosis – no treatment needed in most cases!

Diagnosed ONLY after thoroughly excluding systemic disease

DOES NOT require chemotherapy / transplant

Accounts for ~20-30% of new diagnoses

Begins in the bone marrow the “blood factory” of haematopoiesis

Plasma cells normally produces “antibodies” that protect us from infection

These antibody proteins are made up of light chains and heavy chains

In AL, too many mis-folded light chains are being made

These ‘free light chains’ cannot be broken down efficiently

They bind together to form amyloid fibrils that build up in organs and tissues

Organs involved can be: Kidneys, heart, liver, nerves, intestines, skin, tongue and blood vessels

Requires plasma cell directed therapy:

Daratumumab, Bortezomib, Cyclophosphamide, Dexamethasone

6 cycles / months of therapy

Autologous Bone Marrow transplantation

Must not have significant cardiac involvement and be eligible for transplant

Amyloid resorption antibodies in clinical trials (CAEL101)

Most critical is to support the organs effected:

AVOID B-blockers and ACE inhibitors / ARB

VTE prophylaxis

Nutrition and IV albumin

Immunosuppression prophylaxis: antibiotics (Doxycycline and Ig replacement)

The amyloid-forming protein is “transthyretin” (TTR)

TTR is a produced by the liver

TTR helps to transport thyroid hormone and vitamin A around the body

TTR Amyloidosis can be…

Acquired - 90%

Usually >70 years

Much more common in men

Usually carpal tunnels involved ~10-15 years before the heart is involved

Hereditary - 10% (aka variant-TTR)

Affects men and women equally

>100 known mutations of TTR gene can produce more unstable variant TTR proteins

More easily misfold and aggregats into amyloid fibrils

Carpal tunnels, nerves and heart are usually affected

Much more common than previously recognized

Up to 30% of patients with heart failure despite normal pumping of the heart

Diflunisal (off label anti-inflammatory agent)

Requires normal renal function and surveillance for NSAID complications

Useful for TTR neuropathy

ECGC green tea extract

Yes it actually works – but has a modest benefit

Tafamidis for cardiac TTR has been recommended for PBS – listing expected very soon

Oral

Patiseran - snRNA inhibitors for hereditary TTR with neuropathy

Knocks down TTR protein production and therefore TTR amyloid production

IV medication 3 weekly infusion

Cost >$400000/y - Patiseran pending PBS approval

Symptoms often are non-specific and easily missed -> can mimic other more common conditions

Common vague symptoms at presentation:

New dyspea or pedal ankles

Neuropathy: Numbness/pain in fingers and toes

Autonomic neuropathy: Diarrhea/bloating

Postural hypotension: Light headedness when standing up

Loss of appetite and/or weight loss

Proteinuria in the urine

Screening Echo with “Thickened heart”

New atrial fibrillation

Take a biopsy

“Gold standard” is to detect positive Congo red amyloid staining on a biopsy

Biopsies usually taken from the organ in question, eg. kidney

Blood and urine tests

To measure if there is abnormal production of serum free light chains

Can identify >98% of patients with AL amyloidosis

Bone marrow biopsy

To help confirm the AL type and to access medications

PYP Cardiac “bone” scan

Genetic tests

To exclude hereditary disease

Bone scan showing amyloid in the heart

Use a multidisciplinary team with experience treating amyloidosis

Co-ordinating amyloidosis canter / specialist

Local Haematologist, Cardiologist, Nephrologist, Neurologist, Gastroenterologist, Nursing staff…

Goal

Eliminate the supply of amyloid protein to improve organ function and survival

Manage symptoms to promote patient’s well being and quality of life

General treatment approaches

Decrease production of the amyloid-forming protein

Stabilise the normal structure of the amyloid-forming protein - thus preventing it from misfolding into amyloid

Target amyloid deposits directly destabilizing the amyloid fibrils if possible

Support the organs affected by amyloid deposits

Dr Michelle Spanevello | Haematologist

Bphty(Hons), MBBS(Hons), FRACP, FRCPA Icon Cancer Centre Chermside

Case reports in 1950s linking long-haul flights to thrombosis

Jacques mentions phlebitis first in 3 reports from 1951

Attributed to Homans 1954 reporting DVT in a doctor after a long-haul flight

Homans cases not confined to air travel

2 long-haul flights, 2 long ‘automobile’ trips, 1 crossed leg sitting at theatre

Homans links prolonged dependency stasis to DVT

Reports of PE during the London ‘Blitz’ (air raid shelters) in 1940s

Causality not able to be established

Czuprynska et al, BJH 2020

Cannegieter et al, Travel Medicine Chpt 52 2019

Appears in literature in 1977

Ongoing reports of events with air and overland travel through 1980s and 1990s

Commercial aircraft more regular undertaking

Cramped seating conditions

Variety of modes of travel

Czuprynska et al, BJH 2020 Cannegieter et al, Travel Medicine Chpt 52 2019

One a month dies from DVT at Heath row | Daily Mail On line

British Travel Health Association reports 2500 flying related PE per year

House of Lords Science and Technology Committee inquiry 5th report

2000, funded by Department of Transport

Travel documented as a risk factor for VTE in 2000

Cohort studies, RCTs, Cross-sectional studies

Not without controversy according to correspondence in the Lancet 2004

2001 Giangrande encourages this encompassing terminology

Kestevan, Thorax 2000, Giangrande, J Trav Med 2000

Correspondence, Lancet 2004

Ansari et al, J Trav Med 2005, Czuprynska et al, BJH 2020

Cannegieter et al, Travel

Immobility is a key factor

Risk of VTE doubles after long-haul flight > 4h

This occurs for other forms of travel with seated

immobility

Longer trip / multiple trips increases risk

Risk is accentuated by presence other VTE risk factors

Risk is accentuated in obesity, extremes of height, COCP and thrombophilia

Absolute risk is 1 in 6000

Some flight specific factors may exist

Study results released on travel and blood clots (who.int)

26 172 enrolled as of May 2009

2% developed VTE in association with recent travel

Travellers with VTE were Younger

Previous VTE

BMI slightly higher (28 vs 27)

Using hormonal contraception

Positive thrombophilia test

Tsoran et al, Throm Res 2010

Large population-based case-control study extension of MEGA

1906 patients with index VTE (<70 yo) matched to controls

12% (233) had > 4 h travel in preceding 8 weeks compared to 9.5%

Travel associated VTE OR 2.1

Similar for travel by car, bus, train but more pronounced with air travel

Risk highest in first week after travel

Increased risk with additional risk factors

Kuipers et al, Blood 2009

Czuprynska et al, BJH 2020

Data for arrivals of international flights 1981-1999

Over that time, 4.8M Australian and 4.6M non-Australian citizen arrivals –main analysis on Australian travellers

5408 out of 16205 patients admitted to WA hospital with VTE could be linked to a record of international flight arrival

153 Australian citizens and 438 non-Australian cases of VTE within 100 days of arrival of international flight

Incidence rate highest in first 2w of arrival (“hazard period”)

Keman et al, BMJ 2003

Prospective study, average flight duration 12.4h (10-15h)

355 Low Risk travellers

Exclusions: artificial valves, PPM, chronic conditions, mothers travelling with children less than 2, surgery within 6m, severely obese, previous DVT, coagulation disorders, immobility, neoplastic disease within 2y, large varicose veins

389 High Risk travellers

USS done at 24h on disembarkation

Incidence of 1.4% Asymptomatic DVT only in high risk travellers

Greatest frequency of VTE in non-aisle seats (18 of 19 thromboses, 94.7%)

Belcaro et al, Angiology 2001

Prospective, public advertisement – volunteers with > 10h flight exposure

917 eligible, excluded high risk travellers (previous VTE, on anticoagulation, recent surgery)

Preflight D dimer and then serial up to 3m (excluded those with abnormal preflight D dimer)

112 suspected cases of VTE went onto USS / CTPA / V/Q scan

9 confirmed, 7 had additional risk factors

Frequency of VTE was 1% (compression stockings used in about 1 in 6)

Concluding a positive association between multiple long-distance flights and VTE

Absolute risk per flight > 4h is 1 in 4500-4600 (1 in 6000 in low risk)

Incidence of PE in air travel low 0.4 per million flyers

Incidence PE increases with distance travelled and longer flight

duration

4.8 cases per million for > 10 000km

0.01 cases per million < 5 000km

Consistent increase in risk with additional risk factors such as prior VTE

Lapostolle et al, 2001, Kuipers et al, 2007

Kahn et al, CHEST 2012, Czuprynska et al, BJH 2020

McKerrow Johnson et al, Wild Env Med 2022

Annual incidence of all cause VTE is 1 in 1000

1 in 100 for elderly, 1 in 10 000 for younger population

Slow and steady increase over recent decades

Up to threefold increase with long haul flights (weak)

Incidence 4.0/1000 persons per year compared with 1.2/1000 per year in non-exposed time (retrospective cohort)

Incidence of symptomatic VTE 0.3%

Firkin et al, Aus Prescr 2009, Ringwald et al, Trav Med ID 2014,

Cannegieter et al, Travel Medicine Chpt 52 2019, Czuprynska et al, BJH 2020

Heterogenous studies

Range of outcome measures – some of uncertain clinical significance

Case-control studies suggest a causative association – some do not

Volunteer bias

Recall bias

Survivor bias

Healthy Traveller Effect

Ansari et al, J Trav Med 2005

Czuprynska et al, BJH 2020

Cannegieter et al, Travel Medicine Chpt 52 2019

October 1821 – 5 September 1902

German physician, anthropologist, pathologist, prehistorian, biologist, writer, editor, and politician

Known as "the father of modern pathology“, the founder of social medicine, and to his colleagues, the "Pope of medicine“

Rudolf Virchow – Wikipedia, accessed 17/9/24

Described and named disease processes such as leukaemia, embolism and thrombosis

Developed the first systematic method of autopsy

Introduced hair analysis in forensic investigation

…But perhaps not the Pope of Medicine

Plagiaristic work in Cellular Pathology (1858), third dictum in cell theory: Omnis cellula e cellula (“All cells come from cells”)

Opposed the germ theory of disease

Anti-Darwinist describing Neanderthal man as a deformed human

Various eponymous syndromes attributed to him such as Virchow’s node, Virchow-Robin spaces, Virchow-Seckel Syndrome and Virchow’s triad

Virchow described mechanisms of thrombosis but not a triad

He published on the pathology of pulmonary embolism in 1856 He did not include endothelial injury

Consensus and mention of this terminology appeared in the 1950s Modern understanding is similar to the description from Virchow

Postulated Venous Stressors of Travel

• Immobility

• Cramped Seat Position

• Dehydration

• Hypobaric hypoxia (air)

Immobility: Duration of Travel is Important

Risk increases with increasing duration of flight (4h+)

Risk also increases with several flights in a short time frame

Frequency of severe PE if air travel > 6h is 150 times higher if <6h

Peak risk travel > 8h

Sandor et al, Pathophysiology 2008

Silverman et al, Lancet 2009

Cannegieter et al, Travel Medicine Chpt 52 2019

Firkin et al, Aust Prescr 2009

Pitch in Economy

1980s Boeing 747: 81.3cm (32in)

2000s BA 78.75cm (31in), AA 86.4cm (34in), QANTAS 81.3cm (32in)

Current QANTAS/UA 78.7cm-81.3cm (31-32in), Singapore/Cathay/Emirates 81.3cm (32in), Delta 78.7cm (31in), JAL 83.8cm, Jetstar 76.2cm (30in)

Civil Aviation Authority recommends minimum seat-pitch 71.6cm (28.2in)

Anthropometric growth over time

Silverman et al, Lancet 2009

Best economy seats on international flights out of Australia (smh.com.au) Long-haul Economy Class Comparison Charti - SeatGuru

LONFLIT showed greatest frequency of VTE in non-aisle seats

MEGA study showed associations with extremes of height and obesity

Height > 1.9m after any travel OR 4.7

Height < 1.6 after air travel only OR 4.9

Obese BMI > 30 increased risk

BEST study 2003: No difference between Business and Economy Class

Rage / Knee Defenders / Pre-reclined seats

Jacobson et al, S Afr Med J 2003, Belcaro et al, Angiology 2001, Kuipers et al, Blood 2009, Mendoza, Int J Healthcare M 2018

Limited information on seat pitch Oedema develops in 4 hours sitting Twofold increase in long distance travel by any mode OR 2.7 any travel vs OR 3.0 air travel

Travel thrombosis more frequent after car and bus travel (70%) then air flights (30%)

Dutch pilot study 2014: 2630 Male pilots, 20 420 person years, no difference with general population

Ferrari et al, Chest 1999, Sandor et al, Pathophysiology 2008, Firkin et al, Aus Presc 2009, Kuipers et al, J Thom Haemost 2014

Planes, Trains & Automobiles (1987) - IMDb

No thrombophilia

Random exposure to hypobaric hypoxia and normobaric normoxia

No significant changes in TAT, PT fragment, D dimer and ETP

No evidence of platelet activation

No evidence of endothelial activation

No significant differences in RCC, WCC, Plt, Hct

High responders: Fvl + COCP

Comparison 8h flight, 8h movie marathon, 8h usual daily activities

TAT increased by 30% with flight

D dimer rose to 216ug/L flight, 180ug/L movies

Toff et al, JAMA 2006 Schreijer et al, Lancet 2006

Quiet sitting

Rise in Hct

Rise in protein concentrations

Simulated 8h flight

Reduced humidity

Increased mean plasma osmolality

Increased mean urine osmolality

May reduce fibrinolytic activity

Mendis et al, Bulletin of WHO 2002

Flow:

Lower limb linear blood velocity reduced by ⅔ in sitting, ½ standing cf recumbency

Stasis due to pressure or position eg crossed legs

Window seating and relative immobility / inertia

Hypobaric hypoxia and vessel wall relaxation

Release of nitric oxide, low oxygen pressure

Endothelial wall:

Position / kinking of popliteal veins (tall, short, elderly, obese)

Transverse folds and rings form and fix with age

Localised fibrosis and sclerosis of the intima and media

Hypobaric hypoxia and vessel wall relaxation

Release of nitric oxide, low oxygen pressure

Hypercoagulability:

Low humidity and dehydration, haemoconcentration, hyperviscosity

Activation of coagulation and reduced fibrinolysis present prior to travel (inconsistent)

Additional risk factors

Cramped positions, Relative immobility, ?Hypobaric hypoxia

Direct pressure

?Hypobaric hypoxia

Localised fibrosis / sclerosis

Age

Endothelium

Flow

?Dehydration

?Hypobaric hypoxia

?Low humidity

?Fibrinolysis/?Activation

Additional RF

Coagulability

3-4 minutes every hour

Avoid dehydration

Avoid alcohol

Avoid caffeine

Avoid immobility

Exercise legs regularly (Homans 1954, indirect)

Avoid sedatives

Czuprynska et al, BJH 2020

Watson et al, BJH 2010

Silverman et al, Lancet 2009

Firkin et al, Aus Prescr 2009

Cochrane database 2021

12 RCTs combined (8 LONFLIT)

Below knee to hip, 10-30mmHg

Asymptomatic clots reduced if wearing GCS

CCL I, OR 0.10

Extrapolated benefit

Low risk

4.5 fewer symptomatic DVT per 10 000, 24 fewer

PE per 1 000 000

High risk

16.2 fewer symptomatic DVT per 10 000, 87 fewer

PE per 1 000 000

Czuprynska et al, BJH 2020, Clarke et al, CD 2016 and 2021, Kahn et al, CHEST 2012

Asymptomatic DVT rates in 249 ‘high-risk’ subjects

Clexane 1mg/kg 2-4h before travel, ASA 400mg daily for 3 days commencing 12h prior, no prophylaxis

LMWH 0% vs Aspirin 3.6% vs no prophylaxis 4.8%

et al, Angiology 2002

Silverman et al, Lancet 2009

Kahn et al, CHEST 2012

Czuprynska et al, BJH 2020

If chemoprophylaxis is considered appropriate, anticoagulants should be used over anti-platelet drugs

Silverman et al, Lancet 2009

Watson et al, BJH 2010

Kahn et al, CHEST 2012

Cannegieter et al, Travel Medicine Chpt 52 2019

Czuprynska et al, BJH 2020

https://www.janssenscience.com/products/xarelto/medical-content/use-ofxarelto-in-vte-prevention-for-long-distance-travel , accessed 22/9/2024 Ringwald et al, Trav

Survey of delegates of the XXth ISTH Congress, the 15th ISDB Congress and the 13th Cochrane Colloquium

All taking place in Australia 2005

2089 responses

80% had used preventative measures

ISTH delegates used LMWH and VKA

Medical doctors used more pharmacological prophylaxis than research and non-clinical attendees

High usage in those with no risk factors (77%, 90% in high risk group)

Kuipers et al, J Thromb Haemost 2006

Avoid the window seat

Don’t be too tall or too short or too obese

(No studies address utility of exercises / mobilising)

(No strong recommendation on alcohol)

(No strong evidence for chemoprophylaxis)

(Stockings could reduce oedema/asymptomatic DVT)

Czuprynska et al, BJH 2020 Sandor, Pathophysiology 2008

Travel is a weak provoking risk factor for thrombosis

More relevant in those with additional risk factors

Association is with duration of travel more than mode

Limited evidence for any prophylactic intervention

Assess risk for / benefit of compression / chemoprophylaxis on an individual basis

May benefit from GCS or short period of LMWH

Firkin et al, Aus Prescr 2009

Czuprynska et al, BJH 2020

A/Prof James Morton AM Icon Group Director of Haematology & Clinical Haematologist

Cumulative Full Blood Examination

Cumulative Iron Studies

• Cellular storage iron

• Minute quantities released blood

o Mostly apoferritin

o Proportional to stored iron

• Increased

o 10% iron overload: each 1ug/l = 10mg stored iron

o 90% non iron overload

o NB: alcohol - especially beer (>2/day)

Increased demand

• Rapid growth

• Pregnancy, breast feeding (total 1000mg iron)

• EPO treatment

Increased loss

• Bleeding: Gastrointestinal (GI), renal, menstrual, telangiectasia

• Blood donor

• Venesection: HFE, PRV

Reduced absorption

• Dietary deficiency

• Malabsorption disease: CD, IBD, autoimmune gastritis, PPI

• Malabsorption surgery: Gastrectomy, gastric bypass

*Note:

TIBC: Total Iron Binding Capacity

TF Satn: Transferrin Saturation

sTfR: Soluble Transferrin Receptor

Iron Supplement

• Ferric Citrate

• Ferric maltol

• Ferrous fumurate

• Ferrous gluconate

• Ferrous sulphate

• Ferrograd + C

• Maltofer

• Enteric costed or SR

1gm = 210mg elemental iron

30mg = 30mg elemental iron

325mg = 106mg elemental iron

325mg = 36mg elemental iron

325mg = 65mg elemental iron

Vit C 500mg, elemental iron 105mg

100mg elemental iron

Poor absorption due to iron release beyond upper jejenum (DMT1 duodenum and upper jejenum)

• Haem Iron

50% absorbed; minimal GI: very expensive: supplement rather than replacement

1. Daily or alternate day

• No role bd: hepcidin induction and reduced absorption

2. Optimal empty stomach

• Especially avoid milk, tea, coffee, eggs, fiber, cereals

• Impact meat vs. non-meat protein

3. Vitamin C improves absorption

• NB: Little benefit above 80mg

4. Maximum absorbed per day 25mg

Control 21%, 80mg vit C 27%, 500mg VitC 31%, Coffee 10%, Breakfast 7%

absorbed

Elderly: 15 v 50 v 150 mg elemental iron: No difference rise ferritin or Hb but increased GI

Gastrointestinal (GI) Side Effects

• Metallic taste, nausea, wind, constipation or diarrhea

• Reduce with alternate day and reduced dose of elemental iron

Response

• Pagophagia 24hr, Restless Legs 72hr, sense wellbeing 72hr

• 5 days ↑ retics, 2 weeks ↑ Haemoglobin (Hb) 1g/dl (dependent severity anaemia):

Failure: ↑ Hb 1g/dl at 4 weeks

• Papillation tongue: 4 weeks

Duration

• 3 months after normalisation of Hb

Ferric

- 15%

– 50%

Improvements

- 5%

– 20%

Prolonged Release (Ferrograd) Polymaltose (Maltofer)

*In general: Ferrous S better absorbed and more rapid increase Haemoglobin (Hb),

Ferric Polymaltose better tolerated.

Iron Infusion

• Ferric Carboxymaltose (Ferinject, Ferrosig)

• Ferric Derisomaltose (Monofer)

• Iron Sucrose (Venofer)

Intravenous (IV) Iron dosing

• Ganzoni

o Dose (mg) = wt x (target – current Hb) x 0.24 + 500mg

• Simplified Hb Wt

• Oral iron: compliance / patience / intolerance / failure

• Blood loss exceeds capacity oral iron to meet needs

• Co-existing inflammatory state (Hepcidin block)

• Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD)

• Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)

• Heart Failure

• Athletes

• Pregnancy

• Dose: See Ganzoni

• Site: Forearm, Gravity Feed

• Pre-meds: No*

o *Inflammatory arthritis: Methyl pred 125mg pre, Prednisone 1mg/kg x 4 days post

• Ferinject (FCM): 1gm: 15min, repeat dose 7 days

• Monofer: 1500mg, 30 mins

• Reactions

o Non-Allergic: 1/200: Fishbane reaction: CARPA: labile free iron

• Stop until settled: restart

• Fails to settle 30min: hydrocortisone: restart 30min after settled

o Allergic: serious: 1/200000

• Hypophosphatemia:

o At risk: low Pi (IBD, bariatric surgery, EtOH, Diabetes Mellitus)

o Severe / symptomatic: 11%: 4-14 days: Fatigue, Myalgia

o FCM 50% overall, perists at 5 weeks 30%: Monofer 8%, mild

o Risk Osteomalacia

• Prevalence: 30% stable and 50% unstable patients

• Mechanism: nutrition, malabsorption (hepcidin, mucosal oedema)

• Impact; not Hb mediated (EPO studies): ? myocardial muscle iron

• Treat: Ferritin < 100 or Ferritin < 300 and Tsat < 20%

• Meta-analysis Ferric carboxymaltose (FCM)

o N = 839 (mostly FAIR-HF and CONFIRM-HF studies)

• Improved PS and NYHA score, reduced hospitalisation and all-cause mortality (HR 0.60)

• Benefit limited those with Tsat < 20% and especially < 13%

• TDI: TSAT > 70% ROS: cardiac toxicity

Eur J Heart Failure, 2018:20: 125-133

• Serology Coeliac Disease negative

• G/Colon: Crohns Disease

• Ferinject 1gm: well-tolerated

Dr Ian Irving Haematologist, Icon Cancer Centre Wesley Chief Medical Officer, Icon Group

• 65 year-old woman

• Works in Real Estate

• History of Hypothyroidism

- On thyroxine

• FBC as part of monitoring thyroid replacement therapy

• 65 year-old woman

• Works in Real Estate

• History of Hypothyroidism

- On thyroxine

• Infection – especially viral infections

• Splenomegaly / Hypersplenism

• Autoimmune disease

• Nutritional deficiencies

• Drugs / Medications

• Bone marrow pathology

• Other – including benign and chronic idiopathic neutropenia

• Often the only abnormality on the FBC

• Note reference range differences between labs

• Benign neutropenia often transitory

• Chronic idiopathic neutropenia often a diagnosis of exclusion

• History of infection important in planning management

• Note Benign Ethnic Neutropenia

• 25 year-old woman

• Psychologist

• No significant medical history

• No regular medications

• Examination – no splenomegaly, BMI 32

• 25 year-old woman

Psychologist • No PMHx • No regular medications

• 25 year-old woman

Psychologist • No PMHx • No regular medications

Relatively common finding on FBC

• Generally reactive (especially in absence of other abnormalities)

Wide differential diagnosis

• Inflammatory states, infections

• Role of obesity, smoking

• Rarely primary haematological malignancy

• Can often be observed

88 year old man

Retired property developer

Presentation with Cough

Mild fatigue

No fever or sweats

88 yo man

Retired developer

Presentation with Cough

Mild fatigue

No fever or sweats

88 yo man

Retired developer

Presentation with Cough

Mild fatigue

No fever or sweats

• B12 / Folate deficiency

• Medications

• Alcohol excess / Chronic Liver Disease

• Hypothyroidism

• Reticulocytosis

• Bone Marrow disorders

88 yo man

Retired developer

Presentation with Cough

Mild fatigue

No fever or sweats

• Pre – leukaemia

• Is a continuum to Acute Myeloid Leukaemia (AML)

• Disease of aging in particular

• Myelodysplastic Syndrome vs Myeloproliferative Neoplasms (MPN)

• Mutations now described and pre-MDS state of Clonal Haematopoiesis (CH)

• Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) panels now available

Hypertension - perindopril

Diabetes Mellitus - diet

Reflux oesophagitis

Well

Routine annual FBC

Hypertension - perindopril

Diabetes Mellitus - diet

Reflux oesophagitis

Well

Routine annual FBC

• Artefactual

• Infections - eg. viral, sepsis, DIC

• Medications – drug induced immune thrombocytopenia, alcohol, chemotherapy

• ITP

• Hypersplenism

• B12 / Folate deficiency

• BM disorders

• Familial thrombocytopenia / Other eg. TTP, HUS

• Bleeding history is important

• Isolated thrombocytopenia vs abnormal FBC

• Clinical examination findings

• Level of thrombocytopenia

• Observation and repeat testing

Felt quite well

Elevated WCC

Felt quite well

Elevated WCC

Felt quite well

Elevated WCC

Felt quite well

Elevated WCC

• Basophilia

• Leuco-Erythroblastic blood film Vs

• Isolated neutrophilia

Dr Jason Restall | Haematologist

Icon Cancer Centre Wesley

Icon Cancer Centre Chermside

Icon Cancer Centre North Lakes

Normal range: 0.8 to 4.0

Lymphocytosis may be due to a rise in

-Lymphoblasts

-B lymphocytes

-T lymphocytes

-NK cell

-Or a combination of the above

1. Clonal

2. Non-Clonal

Infection e.g. CMV, EBV, cat scratch disease, HIV, HCV, HBV

Inflammation e.g. autoimmune disease

Hypothyroidism

Smoking

Medications

Hypo/asplenism

Physical stress

Lymphocyte subsets

-Lymphocyte subsets will give a breakdown of the different types of lymphocytes, it does not look for clonality

-It may be useful to determine which subgroups are elevated

-Often if multiple subgroups are elevated it is more likely to reflect reactive lymphocytosis

Surface marker studies are designed to look for clonality

They determine the presence of different markers on the surface of the lymphocytes

This allows a quantitative estimation of the abnormal lymphocytes

The pattern (immunophenotype) of the clonal population may also help in diagnosis of the subtype of leukaemia/lymphoma present

Three populations were analysed:

1. Lymphocytes comprise 71%.

T–cells 14% CD4/CD8: 1.3

B–cells 83% kappa/lambda: >100

NK–cells 2%

A monoclonal B–cell population comprises 83% of lymphocytes The phenotype is: CD5 +ve

CD10 –ve CD19 +ve CD20 +ve (weak) CD23 +ve CD79b weak CD200 +ve CD43 weak SMIg Kappa (weak)

2. Myeloid cells: Neutrophil lineage comprise 25% Monocyte lineage comprise 2%

3. Blasts (CD34+) comprise <0.1%

The majority of clonal mature lymphocytosis will be B- cell Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma, usually with an indolent presentation

Types include:

- B-CLL

- Mantle cell lymphoma

- Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma

- Splenic marginal zone lymphoma

- Marginal zone lymphoma

- Hairy cell leukaemia

More aggressive B-Cell Non-Hodgkin lymphoma may be detected in the peripheral blood, however it is less common

Types include:

- DLBCL - Follicular lymphoma

- Burkitts lymphoma

NB – Hodgkins lymphoma is not usually detected in the peripheral blood and negative surface marker studies do not exclude a diagnosis

Often low grade B-NHL may be monitored

Recommended baseline testing includes -FBC

Looking for the presence of lymphocytosis and cytopenias

Cytopenias may be due to marrow infiltration, sequestration, or autoimmunity e.g.

AIHA/ITP -ELFTs

In particular for elevated LDH, hypercalcemia, or evidence of hepatic or renal dysfunction

Surface marker studies to aid categorisation and to confirm clonality

Protein studies – serum EPP with immunofixation, serum FLC, immunoglobulins

Biopsy – core biopsy or nodal excision is preferred; FNA only confirms the presence of NHL, it does not allow subtyping and would need to proceed to core or excision

CT n/c/ap +/- PET

-Used more for staging rather than for diagnosis

-Can be used to aid prognostication/guide treatment with availability of cytogenetic and FISH studies

Newer testing

- Next generation sequencing panels

Newer therapies are becoming available for treatment of lymphoma

BCL2 inhibitors – venetoclax

BTK inhibitors – ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, Zanubrutinib

Monoclonal antibodies – rituximab, Obinutuzumab

Bispecific antibodies – epcoritamab, glofitamab

Venetoclax

-Approved for usage in B-CLL (also used in AML)

-Recently approved in combination with ibrutinib as an all oral regimen for treatment of previously untreated B-CLL

Predominant issues:

-Tumour lysis at commencement of therapy

-Nausea

-Neutropenia

Approved for usage in B-CLL, mantle cell NHL, Waldenstroms

Macroglobulinemia

-Include ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, Zanubrutinib

Issues include:

-Nausea

-Chest infection

-Atrial fibrillation

-Strong antiplatelet effect – need to be withheld prior to procedures (often as strong/stronger effect than clopidogrel)

Dr Jacquie Taylor |Clinical Haematologist

Icon Cancer Centre South Brisbane

Icon Cancer Centre Redland

39yr lady – referred for opinion regarding recurrent iron deficiency

Ferinject 2015, 2017

Mirena inserted 2018

FOBT negative

Coeliac screen negative

Normal diet, intolerant of oral iron

“debilitating fatigue” , affecting her mood

GP organised another ferinject in the interim.

Differential diagnosis

iron deficiency

bleeding inflammation/infection

Myeloproliferative disorder

? ET/PV/PMF/CML

Polycythaemia vera - PV

Essential thrombocythaemia - ET

Primary myelofibrosis - PMF

Kiladjian JJ. Hematology 2012;2012:561–566

Polycythaemia Vera – features

Increased red cell production

Virtually all have JAK2 V617F mutation +/- leucocytosis and thrombocytosis

JAK2 Exon 12 mutation often isolated erythrocytosis

Can be masked by iron deficiency In 20% of cases presentation is at the time of unexpected vascular event

Venous – DVT/PE, Sagittal vein thrombosis, especially portal vein, mesenteric, splenic vein

Arterial MI, CVA

Major criteria

Elevated Hb or HCT

Men Hb > 165, HCT > 49%

Women Hb > 160, HCT >48%

Bone marrow biopsy morphology

hypercellularity with panmyelosis, including prominent erythroid, granulocytic, and megakaryocytic proliferation with pleomorphic, mature megakaryocytes

Presence of JAK2 p.V617F or JAK2 exon 12 mutation

Minor criteria

Subnormal EPO level

Diagnosis of PV requires all 3 major criteria or the first 2 major + minor criterion

Most common

Fatigue

Pruritus (frequently aquagenic and worsened by bathing)

Night sweats

Other

Driven by high red blood cell mass

headaches (including migraines)

difficulties with concentration less commonly bone pain or splenomegaly-related symptoms.

Physical signs – plethora, splenomegaly, rarely hepatomegaly

Thrombotic events are the leading cause of preventable death in PV

1. Control of red cell mass = phlebotomy and/or cytoreductive therapy

Venesections

Hydroxyurea – Hydrea – Hydroxycarbamide – oral tablets

Peginterferon – Pegasys – Weekly subcut injection

Target HCT <0.45

2. Symptom relief – aspirin, and/or cytoreductive therapy

3. Prevent cardiovascular complications of PV – aspirin, quit smoking, treat diabetes and HTN.

Polycythaemia Vera

LOW risk

Age < 60 and NO prior history of thrombosis

HIGH risk

Age > 60 OR a prior thrombosis

Indolent disease

Does impact negatively on survival compared with age/sex matched population

20% of PV patients evolve to post-PV-myelofibrosis over time

Leukaemic transformation occurs in 2.3-14.4 % of patients with PV within 10yrs and 5.5-18.7% within 15 years.

Risk factors for leukaemic transformation include age, leucocytosis, cytogenetic abnormalities and some mutations.

Initially venesection + hydrea + aspirin

Hydrea + aspirin alone for last 1 yr

If there are unexplained elevations in plts/WCC/Hb – may be a myeloproliferative neoplasm

PV or MF or very rarely CML can present with thrombocytosis not just ET

Iron deficiency is often required to control polycythaemia vera

Do not supplement iron in PV patients

Patients with MPNs are at increased risk of thrombosis

If there is an unexpected or unusual site VTE consider JAK2 testing