5 minute read

ROSALIE FISH: No More Stolen Sisters

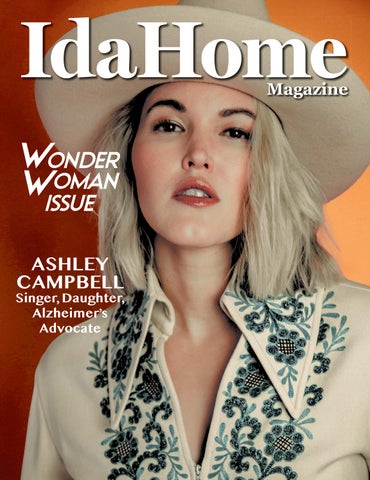

Running in a State Track & Field competition, Rosalie Fish brings attention to Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women. PHOTO COURTESY OF ROSALIE FISH

BY DANA DUGAN

Not every college senior brings to bear quite the gravitas of Rosalie Fish. From Auburn, Washington, she’s a University of Washington social welfare major, already working in her chosen field, and a successful competitor in both the UW’s track and field and cross country programs. A member of the Cowlitz Tribe and a descendant of the Muckleshoot Tribe, Fish dedicates her races to Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW). She gained national attention by painting a red handprint across her face with the letters “MMIW” on her leg during competition inspired by runner Jordan Marie Whetstone.

Native American communities have long struggled with high rates of assault, abduction, and murder of women, and the subsequent lack of acknowledgment of the crimes. Native women have experienced this level of violence for centuries.

This is what drives Fish. “If we really want to combat the crisis, we have to be honest about how we got here,” she said.

“Growing up on a native reservation, where I was accepted and embraced into my culture was super beneficial for my sense of self,” she said. “But our families and our younger siblings are living in this crisis every day. As an Indigenous girl, the minute you turn 12 years old, your rates of violence increase about two and a half times,” Fish explained.

We are one with our nature and with our Earth.

“We’re targeted because of our prominent roles in our community. Women hold a divine and protective role in our communities with our femininity based on the land and Mother Nature and how we are one with our nature and with our Earth. Violence against the land is violence against women. Especially back in colonization. To take control of the land, they tried to take control of the women,” she said.

In her work as an intern for the non-profit organization Mother Nation in Seattle, she’s visited tribal schools, done a TEDxYouth talk, and spoken with young aspiring athletes. Through it all is an urgency. She believes the country has let down Native Americans while shoving the heartbreaking plight of Indigenous women under the rug. Fish said about 70 percent of indigenous people live in urban settings. Washington has 29 federally recognized tribes.

“A lot of us live either in urban areas, or move to and from our reservation,” Fish said in her clear, soft voice. “This means not only are we moving away from our resources, but from protection and restraining orders. So, someone might have a protection order on a reservation, but it might not be acknowledged by, let’s say, the King County Sheriff ’s office. This lack of connection and consistency creates these loopholes in which perpetrators are getting away, basically, with violating protection worse.”

In 2022, Washington State initiated an alert system, like an Amber Alert, for missing Indigenous persons (MIPA). However, many are not aware of the system, resulting in sporadic usage.

“We can only expect so much support from people who have access to the information in the first place,” Fish said. “I think that different organizations and specifically news sources need to go out of their way to bridge those gaps.”

Already, progress is slow but certain. The Yakima Herald assigned a journalist to cover missing and missing or murdered indigenous peoples. And after Fish presented on MMIW for Alaska Airlines, the company placed awareness banners in the Seattle Tacoma International Airport, which you might notice if you’re flying toward family this holiday season.

For Fish, who is grateful for the strong family ties that help fuel her advocacy, the holidays are complicated. Columbus Day, now known more correctly as Indigenous People’s Day, Halloween with its “Injun” outfits, and Thanksgiving.

“I would like to see people redefine what Thanksgiving means to them,” Fish said. “People need to really consider the story of the Dakota 38, basically the biggest mass execution in the U.S. If that was something students were learning in schools around the same time as Thanksgiving, it would have an impact,” she said.

Through her work, Fish urges educators to avoid normalizing or idealizing interactions between colonizers and Native Americans, bringing awareness to the history of colonization, which eroded more than 500 years of tribal sovereignty.

“If we had a little bit more perspective on this, what was actually happening during colonization, people would be able to move about the holiday with a little bit more grace. Native Americans don’t want to end a holiday that brings families together. Of course, it’s not our goal,” she explained. “But we’d like to see a reality check of what happened and what it means. It’s a bitter reminder that our histories are not taught and not valued. We can be more mindful.”