3 minute read

Listen Up: The Duality of Choice

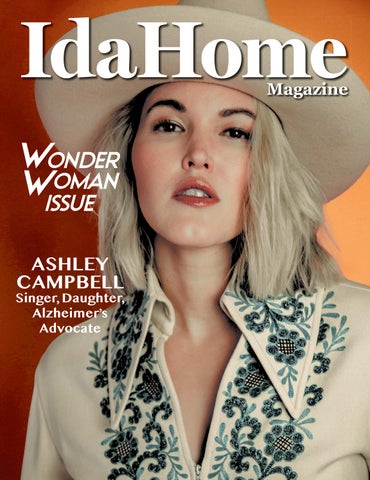

Katherine Goble Johnson (Taraji P. Henson), Dorothy Vaughan (Octavia Spencer), and Mary Jackson (Janelle Monáe) played critical roles at NASA during the Space Race.

BY CHERIE BUCKNER-WEBB

Recently, I gave the keynote speech at a corporate leadership conference.

“I stand before you today, a seasoned woman with broad and diverse experience in a breadth of environments. I am a woman who has maneuvered through generations in the workplace,” I shared.

It’s true—I’ve shared space with Baby Boomers (born 1946-1964), Generation X (born 1965-1979), Generation Y (born 1980-1994), Generation Z (born 19952009), and Generation Alpha (born 2010-2024). I’ve faced the ever-changing challenges for women.

Far too many women, wherever they are in the life of their career, have experienced feelings of invisibility, being undervalued, judged, discounted, and/ or overlooked. With great regularity, women are confronted with a plethora of mixed messages in the workplace, both professional and personal. And we devote way too much time struggling to interpret their meanings.

The 2016 film Hidden Figures is based on the professional lives of three accomplished African American mathematicians (Katherine Goble Johnson, Dorothy Vaughan, and Mary Jackson), who were critical to NASA winning the Space Race and relegated to second class status. Their names, accomplishments, and contributions were omitted from official documents during their employment at NASA. They were prohibited access to onsite facilities during that time, though they were crucial to putting Americans on the moon.

Still today, women remain overwhelmingly faced with no-win situations and a tremendous amount of judgment in the workplace. Often, female intention is misinterpreted. Negotiating for a salary is seen as opportunistic self promotion, and assertiveness is misconstrued as aggression. Alternatively, women who are warm and compassionate may be viewed as too soft. It seems that women are expected to be all things. Nice, kind, and compassionate, not too young or too old. A woman in a leadership role must make tough decisions, visibly take charge, and lead the workforce by personal example. Is it a problem to solve or polarity to manage? If a problem, then whose?

Social scientists term these situations “ambivalent sexism.” When women face ambivalent sexism, they’re compelled to choose between being liked but not respected, or respected but not liked. Men seldom face such a dynamic. When ambivalent sexism exists in an organization, women who adhere to stereotypical feminine roles meet with benign approval, but are not seen as drivers. Women who don’t follow traditional scripts may be respected for outcomes, but not particularly appreciated.

The same behaviors can be judged quite differently based on the gender of the person exhibiting them. It takes excessive amounts of energy for women to stay in the game, and we lose talent when we diminish and exhaust women by offering two irreconcilable demands, which drains productivity, stifles development, and suffocates creativity.

At 71, I’m a proud woman who is still standing. I’ve learned from personal experience, and from a cadre of phenomenal women leaders with whom I’ve engaged. I will be ever grateful for their advice and example: being congruent, seeking good counsel, engaging authentically, and “speaking the truth and shaming the devil.”

We know better. Let’s do better.