25 minute read

Notable Words

A New Era of Automation

By Aurelio Banda, Group Vice President of Automation, Motion

»TODAY, AUTOMATION AND manufacturing are synonymous with transforming an industrial company. The demand for automation technology is growing as companies across industries look for ways to streamline and speed production and manufacturing. The trends of high-cost labor, low cost of capital, workforce skills gap, reshoring manufacturing footprint, and pandemic-proofing operations lead the way for automation justification to transform factory floors. Furthermore, a new automation era is upon us with rapid advances in robotics, artificial intelligence, data analytics, IIoT, and machine learning. This technology enables machines to match or outperform human capital in a range of workplace activities, including repetitive and cognitive tasks.

The acceptance for automation and the change in manufacturing fall across an arch of present needs with future outcomes in mind for industry executives. Companies range from just getting started to already embracing automation; a growing number foresee the implications of this new automation age on their ongoing business model. Several factors to consider in connecting the present to future states of automation are: 1) The present state: What automation is making possible with current technology. 2) The transforming state: What is likely to be made possible as technology evolves. 3) The future state: What to consider (besides technical feasibility) when evaluating automation – where and how much to automate to best capture value over the long term.

A leading direction in the new automation era brings both engineering and IT disciplines to set the pace for future automation and technology. For example, with the rise of automation and robotics acceptance in their sites, many manufacturers will be operating high-speed and high-volume production applications. Most advanced systems will run adjustments without interruption, switching between product types with no need to stop the line to change programs or reconfigure tooling – a function of both engineering and IT disciplines. This integration convergence is realized through communication between machines and robots – the engineering discipline – on the factory floor, calling on the IT discipline to supervise the modern networking technologies.

The manufacturing future is to leverage technology, balancing the overall operating strategy with business goals. Selecting the right level of technology implementation for future needs requires a thorough understanding of the organization’s processes and manufacturing systems. For instance, every project with automation considerations must be assessed for the right level of technology. The improvements it can offer directly link to the organization’s overall strategy: digital transformation. The next five years will see an increase in technology accessibility because of automation platforms and networking connectivity availability, driving companies to make their digital transformation plans ready to implement.

As we partner with companies to streamline processes, increase production, and improve manufacturing efficiencies, we create significant opportunities to leverage automation technology for these outcomes. The digital transformation from present to future states in manufacturing environments will be best served by working with partners who can assist with scaling automation solutions while reducing complexity with ease-of-use software and scalable hardware. Our proven approach is to partner closely with our customers and suppliers on automation applications and product developments. Motion’s principles to engineer product designs, develop proofs of concept, and deploy automation builds are keys to the successful digital transformation of manufacturing environments.

PUBLISHER Innovative Designs & Publishing, Inc.

3245 Freemansburg Avenue, Palmer, PA 18045-7118 Tel: 800-730-5904 or 610-923-0380 Fax: 610-923-0390 • Email: Art@FluidPowerJournal.com www.FluidPowerJournal.com

Founders: Paul and Lisa Prass Associate Publisher: Bob McKinney Editor: Michael Degan Technical Editor: Dan Helgerson, CFPAI/AJPP, CFPS, CFPECS, CFPSD, CFPMT, CFPCC - CFPSOS LLC Director of Creative Services: Erica Montes Account Executive: Norma Abrunzo Accounting: Donna Bachman, Sarah Varano Circulation Manager: Andrea Karges

INTERNATIONAL FLUID POWER SOCIETY

1930 East Marlton Pike, Suite A-2, Cherry Hill, NJ 08003-2141 Tel: 856-489-8983 • Fax: 856-424-9248 Email: AskUs@ifps.org • Web: www.ifps.org

2021 BOARD OF DIRECTORS

President: Rocky Phoenix, CFPMMH - Open Loop Energy, Inc.

Immediate Past President: Jeff Kenney, CFPMHM, CFPIHM, CFPMHT - Dover Hydraulics South First Vice President: Denis Poirier, Jr., CFPAI/AJPP, CFPHS, CFPIHM, CFPCC - Eaton Corporation Treasurer: Jeff Hodges, CFPAI/AJPP, CFPMHM - Altec Industries, Inc.

Vice President Certification: James O’Halek, CFPAI/AJPP, CFPMIP, CMPMM - The Boeing Company Vice President Marketing: Scott Sardina, PE, CFPAI, CFPHS Waterclock Engineering Vice President Education: Randy Bobbitt, CFPAI, CFPHS Danfoss Power Solutions

Vice President Membership: John Bibaeff, PE, CFPAI, CFPE, CFPS

DIRECTORS-AT-LARGE

Chauntelle Baughman, CFPHS - OneHydraulics, Inc. Stephen Blazer, CFPE, CFPS, CFPMHM, CFPIHT, CFPMHT Altec Industries, Inc. Randy Bobbitt, CFPAI, CFPHS - Danfoss Power Solutions Steve Bogush, CFPAI/AJPP, CFPHS, CFPIHM - Poclain Hydraulics Cary Boozer, PE, CFPE - Motion Industries, Inc. Lisa DeBenedetto, CFPS - GS Global Resources Daniel Fernandes, CFPECS, CFPS - Sun Hydraulics Brandon Gustafson, PE, CFPE, CFPS, CFPIHT, CFPMHM - Graco, Inc. Garrett Hoisington, CFPAI/AJPP, CFPS, CFPMHM Open Loop Energy Brian Kenoyer, CFPHS - Five Landis Corp. Jon Rhodes, CFPAI, CFPS, CFPECS - CFC Industrial Training Mohaned Shahin, CFPS - Parker Hannifin Randy Smith, CFPHS - Northrop Grumman Corp.

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR (EX-OFFICIO)

Donna Pollander, ACA

HONORARY DIRECTORS (EX-OFFICIO)

Paul Prass, Fluid Power Journal Liz Rehfus, CFPE, CFPS Robert Sheaf, CFPAI/AJPP, CFC Industrial Training

IFPS STAFF

Executive Director: Donna Pollander, ACA

Communications Director: Adele Kayser Technical Director: Thomas Blansett, CFPS, CFPAI Assistant Director: Stephanie Coleman

Certification Coordinator: Kyle Pollander Bookkeeper: Diane McMahon Administrative Assistant: Beth Borodziuk

Fluid Power Journal (ISSN# 1073-7898) is the official publication of the International Fluid Power Society published monthly with four supplemental issues, including a Systems Integrator Directory, OffHighway Suppliers Directory, Tech Directory, and Manufacturers Directory, by Innovative Designs & Publishing, Inc., 3245 Freemansburg Avenue, Palmer, PA 18045-7118. All Rights Reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part of any material in this publication is acceptable with credit. Publishers assume no liability for any information published. We reserve the right to accept or reject all advertising material and will not guarantee the return or safety of unsolicited art, photographs, or manuscripts.

VOTE OF CONFIDENCE

By Corey Holloway, Sales Manager North America, anyseals, Inc. Choosing the Right Seal for a Hydraulic Pump

In recent months, seal suppliers for distribution and maintenance and repair markets have reported a surge in demand for high-pressure oil seals. This trend is not a coincidence, as these devices are some of the most widely used sealing components in circulation today. The industrial oil-seal market is divided into three primary types: axial, radial, and mechanical. Oil seals, also called shaft seals, are radial lip-type seals specifically designed for retaining lubricants in equipment with rotating, reciprocating, or oscillating shafts. They are found in various applications, from gear engines and construction equipment to rolling mills and wind power generators. Oil seals are in critically short supply as the industry emerges from the manufacturing shutdowns and slowdowns during the pandemic. Although oil seals play an essential role in keeping equipment running for the high-pressure hydraulic pump market, finding a reliable and available supply source can be tricky. Here are some things to consider when choosing the proper seal for a hydraulic pump application.

Seal function

Oil seals preserve a lubricating medium within a defined space. They also safeguard the sealed space from dirt, dust, and other potentially damaging contaminants. For example, in a high-pressure hydraulic pump operating environment, the entire sealing system, com-

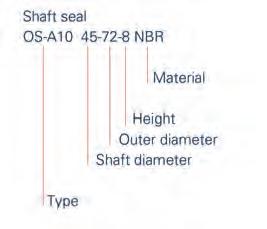

Figure 1

Typical oil seal designation.

prised of the shaft seal, shaft housing, fluid medium, and environment, determines the seal function and level of durability required. Therefore, select an easy-to-replace-and-install product that offers leakage-free sealing in various working environments. This choice should offer low-friction sealing resulting in minimal power loss and heat development. Oil seals are manufactured according to strict quality standards and are under constant control for compliance with common international norms. This works to the advantage of the user, who is assured a certain quality and fit no matter the product's manufacturer. For the sake of continuity, the typical designation of an oil seal includes the type, shaft diameter, outer diameter, height, and material (see figure 1).

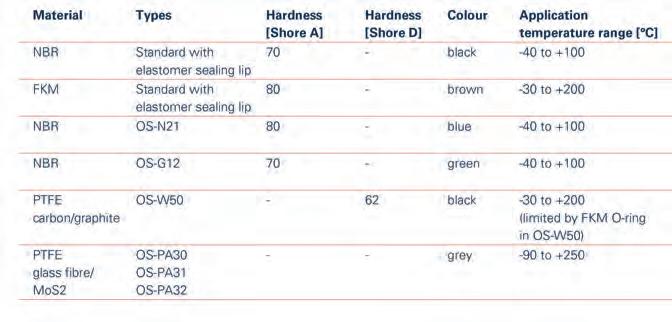

Materials

A wide range of standard materials and an extended range of special materials are designed to handle most traditional oil-seal applications. Among the standard seal types, NBR is the most widely used material. NBR is characterized by good mechanical properties, high abrasion resistance, high tensile strength, low gas permeability, low compression set, and high resistance to petroleum-based oils and fuels, silicone greases, hydraulic fluids, water, and alcohols. NBR is a copolymer of butadiene and acrylonitrile (ACN). Depending on the application, the content of acrylonitrile can vary between 18% and 50%. Low ACN content improves cold flexibility at the expense of the resistance to oil and fuel. High ACN content enhances the resistance to oil and fuel while reducing the cold flexibility and increasing the compression set.

When it comes to oil-seal materials, the following are not recommended for NBR: • Fuels with high aromatic content, such as jet fuel, diesel fuel, high-octane gasoline, and gasoline. • Aromatic hydrocarbons such as methylbenzene, naphthalene, phenanthrene, trinitrotoluene, and o-dihydroxy benzene. • Chlorinated hydrocarbons, such as the pesticide DDT and vinyl chloride, which are manufactured in large quantities to produce polyvinyl chloride and manufactured to produce pesticides, solvents, precursors to various industrial processes, coatings, polymers, and synthetic rubber products. • Nonpolar (lipophilic) solvents that dissolve

nonpolar substances such as oils, fats, and greases. Examples include carbon tetrachloride, benzene, diethyl ether, hexane, and methylene chloride. • HFD fluids, which are water-free, synthetically produced, and fire resistant. • Brake fluid DOT 3 (glycol type); ethylene propylene diene monomer (EPDM) rubber is the preferred material for this application. • Ozone; EPDM, FKM, and PTFE are recommended

Fluorinated rubber (FKM) is another common material characterized by resistance to ozone, weathering, and aging. FKM materials meet the needs of many applications requiring high thermal and chemical resistance. FKM also offers low gas permeability, making it a suitable material for vacuum applications. FKM is not resistant to glycol-based brake fluids, polar solvents (e.g., acetone), superheated steam, hot water, amines, alkalis, and low-molecular organic acids (e.g., acetic acid).

Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) is a fluorinated thermoplastic material with many positive characteristics for sealing material. This includes high thermal and almost infinite chemical resistance. Compared to NBR and FKM materials, PTFE has the lowest friction coefficient, making it most suitable for dynamic applications. Oil seals are composed of PTFE with fillers. PTFE does not, however, have any elastic properties and is typically energized with other complimentary materials such as elastomers or spring steels.

The most important materials for seals in this group are: • NBR (acrylic nitrile butadiene). It has good mechanical properties, including abrasion resistance, can be adapted to different tasks by varying the acrylic-nitrile content, and is suitable for temperatures ranging from -20°C to 100°C (-4°F to 212°F). • FKM has high resistance to mineral oil and HFD fluids even at high temperatures up to 200°C (392°F).

Standard and special seal types

Operating parameters will generally determine if an application requires a standard or special sealing solution. As a rule of thumb, all standard

seals are designed for nonpressure applications. When excess pressure develops within the unit to be sealed during operation, check the air vents to see if they are clean, open them if necessary, or use a special seal designed for high-pressure applications. However, pressures up to 0.05 MPa (7 psi) can be controlled by standard types.

If the application dictates higher than normal pressures, special types and profiles that use advanced materials or profiles are available. For example, the anyseals type OS-N21 is composed of a sealing lip that is shorter and stiffer than the standard type of seal, preventing increased contact pressure. The OS-N21 anyseals type was designed for pressures up to 1.0 MPa (145 psi). The reinforcing ring is pulled down lower on the shaft diameter to better support the sealing lip. The lower flexibility of the sealing lip requires tighter tolerances with regards to the dynamic runout and offset. Application limits depend on the rotational speed and diameter of the shaft (see figure 3).

In conclusion, be diligent when searching for the greatest possible availability of quality standards and special seal types. For quality assurance, seek a supplier that provides certified sealing products that can be identified and traced by lot and material number.

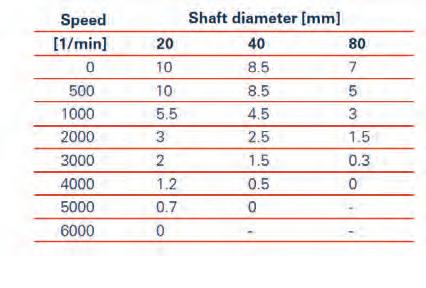

Figure 3

Standard materials for shaft seals.

Maximum press [bar] for the OS-N21. The figures apply to oil lubrication and favorable heat dissipation conditions.

ON TARGET LUBRICANTS

EQUIPOWER HYDRAULIC OIL

Reliable hydraulic performance depends on fluid choice; it’s not just about viscosity grade. fluid choice; it’s not just about viscosity grade.

LE’s line of Equipower™ Hydraulic Oils are engineered to ensure smooth performance and superior protection for your equipment. Important considerations when choosing hydraulic oil:

Ability to maintain viscosity Thermal and oxidative stability Friction reduction capability Nonfoaming characteristics Detergency Demulsibility Hydrolytic stability

www.LElubricants.com | 800-537-7683 | info@LE-inc.com | Wichita, KS For more about LE’s high-performance lubricants, contact us or visit our website today.

ON THE

By Andrew Iddeson, Global Technical Director, Hallite; and Chuck White, Director of Sales and Marketing, Hallite Americas BORDER

Boundary Lubrication in Cylinder Seals

When it comes to hydraulic cylinder sealing systems, boundary layer lubrication is key to ensuring the longevity of the seals. However, as environmental and emission concerns grow, we should consider actual leakage versus factors in lubrication that contribute to the long-term effectiveness of seals and cylinders.

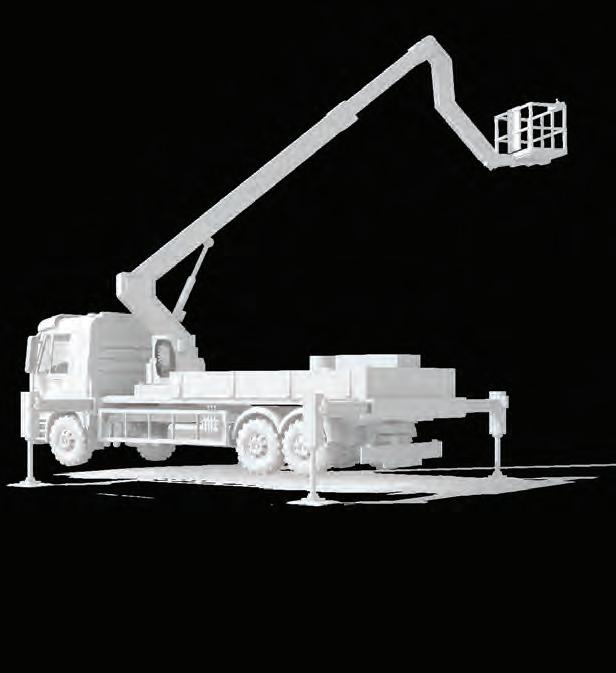

Boundary lubrication is a thin film of fluid that passes under the sealing lip, reducing friction and heat that contributes to wear reduction at the sealing lip. But given environmental and cost concerns, just how much boundary lubrication is acceptable? The answer depends on the application as well as the individual circumstances in which the seal is operating. For example, long-stroke cylinders used in applications such as cranes require a slightly higher level of boundary lubrication because the sealing elements cover more surface area during the cycle. Cylinders used in general mobile hydraulic applications such as aerial handling equipment require less boundary lubrication due to the cylinder’s size and duty cycle. Finding the right balance of boundary lubrication to promote seal life while meeting the application requirements can be challenging.

Finding the right balance

As we’ve said, boundary lubrication is an acceptable amount of fluid that passes under the sealing lip to promote seal longevity. This light film is carried in microscopic peaks and valleys in the surface finish of the dynamic hardware. The sealing lips of the seal conform to these peaks and valleys where the film of oil exists. If the peaks and valleys are too large, excessive boundary lubrication might be allowed to pass by the sealing lip. But insufficient peaks and valleys prevent the formation of the oil film, causing excessive wear. Seal profile also plays a role in balancing boundary lubrication. The correct seal profile at various pressures is key to making sure boundary lubrication is not cut off, which would result in frictional heat and wear at the sealing lip.

The industry uses several methods to assess the presence of boundary lubrication. The U.S.-based Society of Automotive Engineers developed the SAR J1176 standard to characterize the visual appearance of the boundary lubrication on rods in hydraulic cylinders. Though the standard is subjective, it provides a benchmark to assess and establish a level of boundary lubrication tolerable in a given application. This standard also provides guidelines to reference when experiencing an unacceptable level of boundary lubrication.

Although many national and international standards define methods for testing leakage in fluid power systems, few define acceptable leakage rates, preferring that users define their limits.

However, one standard that does apply limits is JIS B 8354. This standard is challenging because it requires a collection of boundary lubrication samples or readings over a set number of cycles or distances, thus requiring longer monitoring periods for assessment. However, because JIS B 8354 defines acceptable leakage levels by classifying the application, it allows the user to confidently develop their own acceptance limits based on a volumetric measure according to cylinder size and end use.

Acceptable is subjective

Despite the two standards, opinions on the acceptable level of boundary lubrication vary and depend on the application. In general, Hallite uses several criteria when assessing acceptable levels of boundary lubrication.

When evaluating boundary lubrication using visual standard SAR J1176, levels of 0-2 are acceptable. Since all cylinders exhibit a “drip” of oil, the visual standard sets the boundaries of acceptable lubrication levels as guidance to identify potential concerns and issues with reallife examples per application.

In class A leakage acceptance, the JIS 8354 standard is interpreted to show that on a 2-inch (50-mm) rod (as per Hallite testing), an acceptable limit should not exceed 0.05 ml per 100 m traveled. On the test rig, this equates to 20 ml over 50k cycles, the equivalent of 40 Km traveled.

An acceptable level of boundary lubrication or leakage is subjective. Though standards exist to provide guidance on recommended levels, the end application plays a huge role in setting the standard. Benchmark testing allows for databased decision-making. Data collection based on real-life field conditions ensures compliance with set leakage standards such as JIS B 8354. It is difficult to offer data on every possible operating combination. However, with new technology in test equipment and methods, assessing seal performance is becoming easier in a lab setting.

Air Compressors Clean Dry Air Improves Performance...

Clean, Dry Compressed Air Starts with The Extractor/Dryer® Manufactured by LA-MAn Corporation

• Point of Use Compressed Air Filter to

Improve and Extend Equipment Life • Removes Moisture and Contaminates to a 5-Micron Rating: Lower Micron

Ratings are Available • Models with Flow Ranges of 15 SCFM to 500 SCFM Rated Up To 250psi are

Easy Installation • Weep Drain is Standard; Float Drain or Electronic Drain Valves Optional

efficient reliable tight

Plugs with integrated molded NBR or FKM seal. Automatically assembled with integrated control. Our products can be found worldwide in hydraulic applications and drive technology. We stock for you.

HN 10-WD | SCREW PLUG

Our solution

Shifting Gears

By Philippe Tottoli, E-mobility Program Marketing Manager, Poclain

Converting to an Electrohydrostatic Transmission

Low- and zero-emission vehicles are making their way from the roads to the off-highway market driven by regulations and national environmental policies. Hybrid and electric machinery have merged onto both jobsite and field. This pressure has many mobile machinery OEMs looking for ways to electrify their traditional internal-combustion engine (ICE) models.

OEMs are faced with a number of challenges. For the end user, electrified machine performance must be identical to the equivalent ICE machine to carry out the same work. Likewise, the electric machine must offer acceptable range and battery lifetime to reach sufficient daily availability for work. The noise level of the electric machine must be significantly lower than the equivalent ICE machine to improve working conditions for the driver and reduce noise pollution in urban environments. Above all, to make economic sense, the electric machine needs to deliver a return on investment comparable to the equivalent ICE machine within a reasonable time frame. Lower operation and maintenance costs help the owner achieve the desired lower total cost of ownership.

OEMs are caught between the pressure to design to meet new regulations and increasing demand from end users facing tighter-than-ever schedules and changing rules.

For off-highway machine manufacturers caught in this situation, electrohydrostatic technology may be an answer because it does not require a complete machine redesign and allows for a high degree of commonality between the ICE and electrohydrostatic versions. Part and design commonality makes the transition easier for the OEM in terms of production changes, after-sales support, maintenance, as well as end-user training and adoption. By electrifying the hydrostatic system, OEMs are able to deliver the same benefits of timetested, reliable cam-lobe hydrostatic technology without the emissions.

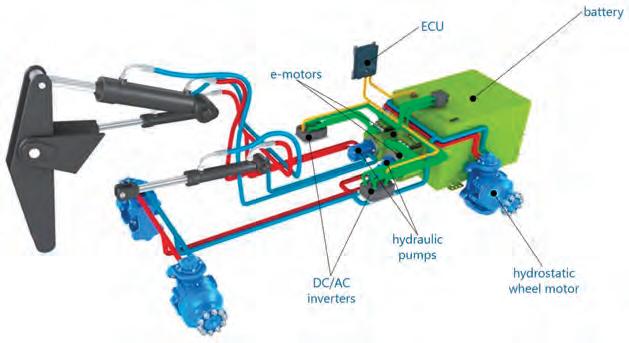

An electrohydrostatic transmission is a system made of hydraulic, electric, power electronics, and electronic components combined with control software. The hydraulic components are typically hydraulic motors, drive pumps, and valves. The electric components are electric motors and batteries, which can include different technologies. The power electronics components are DC/AC inverters, an onboard charger, and a DC/DC converter. The electronic components include the electronic control unit, sensors, display, connectors, and accessories.

Electrifying an off-road mobile machine with an electrohydrostatic transmission can be broken down into a few steps: machine inspection, input data collection, transmission presizing, realization and optimization, and field monitoring. To illustrate the process, take the example of a mini wheel loader recently electrified by Poclain Hydraulics’ electromobility team. The mini loader, with an operational weight of around 1.8 tons, was originally equipped with a diesel engine and a hydrostatic transmission based on wheel-motors, hydraulic boom, and tools.

Machine inspection

The first step the team took after receiving the mini wheel loader and before starting any electrification activity was to perform a complete machine inspection and verify proper function. Once this was completed, the machine underwent a full battery of performance tests, including an inventory, to characterize all the hydraulic systems in their original configuration. The objective was to build a machine model for system simulation software to simulate the operation of the hydraulic systems. The team also carried out acoustic tests in the original configuration to measure the difference in sound level between the diesel and electrified machines.

Input data collection

The next phase was to gather the input data needed to design the transmission: machine duty cycle, machine mission profile, and geometrical and weight constraints. This phase of data collection and analysis was part of a connected engineering campaign.

Confirmation of real-life duty cycles. The team sent the mini wheel loader equipped with a connectivity box into the field to perform a series of operations matching typical machine usage. The connectivity box was connected to the machine’s CAN bus to upload the data directly to the cloud. The team put the machine through a number of work scenarios to attain a large enough data sample. Work included traveling at different speeds, empty and loaded, on flat surfaces as well as uphill and downhill; moving the bucket up and down, and filling and emptying the bucket, among other operations.

Throughout these operations, the objective of the data collection was to confirm the machine’s duty cycle for the transmission and auxiliary functions. Obtaining in-depth knowledge of the duty cycle is a key step in the electrification process and has a major impact on the correct sizing of transmission components and power distribution to auxiliaries.

Defining the mission profile. Machine mission profile definition has a major impact on the required amount of energy embedded in the batteries and its distribution between transmission and tools.

For the electrification of the mini wheel loader, the team targeted a machine range of a complete working day with charging in the middle of the day. In typical use, the machine works intermittently during the day. To obtain the most realistic mission profile possible, the profile integrated operations with several of the most frequently used tools.

Geometrical and weight constraints. After validating the duty cycle and defining the mission profile, the team needed to characterize the machine geometry, weight distribution, and center of gravity.

Transmission presizing

After gathering the input data, the next phase was presizing the transmission.

Performance envelope. The first stage involved characterizing the performance envelope of the machine in the four quadrants. The performance envelope is given by the curve of the machine tractive effort as a function of the machine speed. From this curve, the performance envelope of the different components of the transmission were determined. This is actually the process of presizing the transmission components.

Define and simulate architecture. The team designed several possible system architectures to respond to the transmission requirements and the power distribution to auxiliaries. These architectures included the main hydraulics, and electric and power electronics components.

The team performed simulations for each of the defined architectures to verify whether their performance matched the requirements of the transmission and the power distribution to auxiliaries. Simulation is a very powerful tool that makes it possible to verify the overall performance of a system quickly to prevalidate an architecture without having to carry out tests on a real machine.

Select and presize electric and hydraulic

components. Once the team defined the system architectures, it was time to drill down to the component level. Based on the input data and simulation results, they selected and presized the different components of the architectures. Components included a drive pump, closed loop circuit valves, hydraulic motors, inverters, e-motors, a DC/DC converter, an onboard charger, an electronic control unit, a display, sensors, and connectors. At this point in the process, adjustments or component changes are still possible.

Selecting a final architecture by simulation.

Among the simulations of the different system architectures, the team selected the one that best matched the system requirements based on the energy efficiency criteria, compatibility with economic constraints, and available space.

(Continued on page 12)

Realization and optimization

After presizing the components, the next phase was practical realization, including transmission optimization and auxiliary power distribution.

Integration study. Once the architecture was defined and the dimensions of every component were known, it was possible to proceed with a detailed integration study of the system within the machine. In the case of the mini wheel loader, once the diesel engine, the fuel tank, the radiator, cabling, and several other components were removed, the team defined the available space for the electrohydrostatic drivetrain using the existing machine geometry.

When needed, they used a 3D scanner to digitize the machine geometry and environment. Then they defined the arrangement of the components to keep the weight distribution and center of

Nothing moves without us.

Versatile and Flexible

Mobile controller type ESX

Efficient, Reliable and Durable

Variable displacement axial piston pump type V60N

Precise, Flexible and Safe

Load-holding valves type CLHV

Visit HAWE

9.28 - 9.30 Booth A1520 Louisville, KY

Industry Leading Performance

Proportional directional spool valve PSL-CAN

Register now for HAWE’s online Event on 10.14! Learn about:

• Small compact power units • Virtual 3D products and environment • Launching of two new HAWE products • Production factory tour • Applications examples • Break-out sessions • Live Q&As and chat feature

HAWE Hydraulik is a leading manufacturer of technologically advanced, high-quality hydraulic components and systems. HAWE products are used wherever high quality, high power and maximum precision is required - whether in mining and drilling equipment, construction machinery, CNC machines or wind turbines.

Partner with HAWE to always have the right solution!

www.hawe.com | info@haweusa.com | 704-509-1599

Field Sales and Operations opportunities available now. Visit the HAWE Job Market online to apply today. gravity within the limits of the machine’s operational weight.

Control strategies and functional safety

analysis. Based on the customer and machine requirements, the team specifies system and control strategies for all machine life cases. In this case, they performed a safety analysis to ensure the safety functions of the system based on generic customer and machine requirements. Then they programmed the software of the electrohydrostatic transmission before uploading it in the transmission electronic control unit.

Integrating the transmission. Next, the team mounted and assembled the electrohydraulic system into the mini wheel loader. Then they uploaded the vehicle control and e-hydrostatic transmission-embedded software into the electronic control unit.

Machine commissioning. The last stage of electrification was the commissioning of the mini wheel loader. During this stage, the team checked, inspected, and tested every major component of the transmission and the power distribution to the auxiliaries at the individual component level and the integrated function level. The final result was a perfectly functioning and safe zeroemission electrohydraulic machine.

Field monitoring

Generally, the machine is fitted with a log box connected to the CAN bus that collects machine performance data and use. This is a powerful way to monitor performance under real customer operating conditions. We can also refine duty cycle and mission profile characterization to improve machine design and optimize transmission sizing for the next machine release.