The Nature Vision renovation in the Northern Pacific Business Center created a new office, service center, and warehouse distribution facility. Incorporating Nature Vision’s contemporary design with the building’s existing architecture made this new space not only functional, but completely original. This local business’ expansion brings new opportunities to the historicrailroad center and the surrounding community. MN

National

Hamdi

“Our

•

•

•

•

•

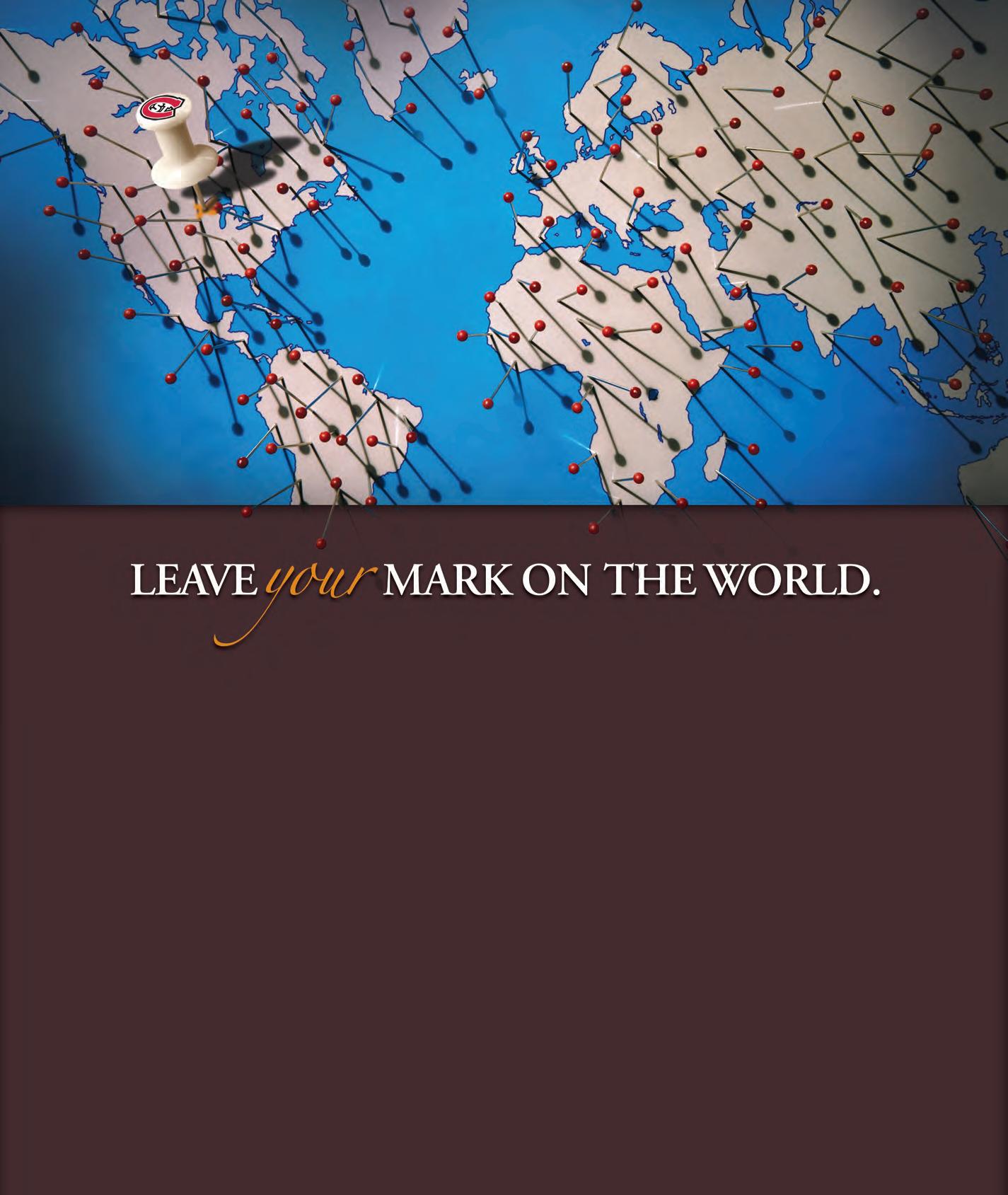

St. Cloud State University might be right here in Minnesota, but we’re leaving our mark all over the world. St. Cloud State is home to nearly 1,000 international students from more than 80 countries. Each year, hundreds of St. Cloud State students study abroad in 20 countries—from England to South Africa— while earning credits they can use to complete their degrees. We have nationally and internationally known faculty teaching in our highly accredited undergraduate and graduate degree programs. St. Cloud State—a smart investment in a global education.

www.stcloudstate.edu • 877.654.SCSU

attention aren't what you'd normally associate with financial planning providers, it's time to discover DeGraaf.

We're experienced, easy to talk to, and

how

With each heavy step across the weathered gangplank, Jan Bakker moved farther away from all he knew. What if America wasn’t as good as the stories?

Jan’s father sold yeast to the Castricum, Holland bakers, but it wasn’t enough. His mother died of tuberculosis. He collected prescription bottles to resell to apothecaries, but only at a penny per hundred. There must be more to life than this.

With ship-learned English and little money, Jan touched Ellis Island in 1904. America afforded boundless opportunity to those who weren’t afraid of hard work, but it also demanded sacrifice. Immigrants were the lowest of the low. For much of his adult life, Jan endured despair and discrimination on his way to establishing a foothold that secured future generations.

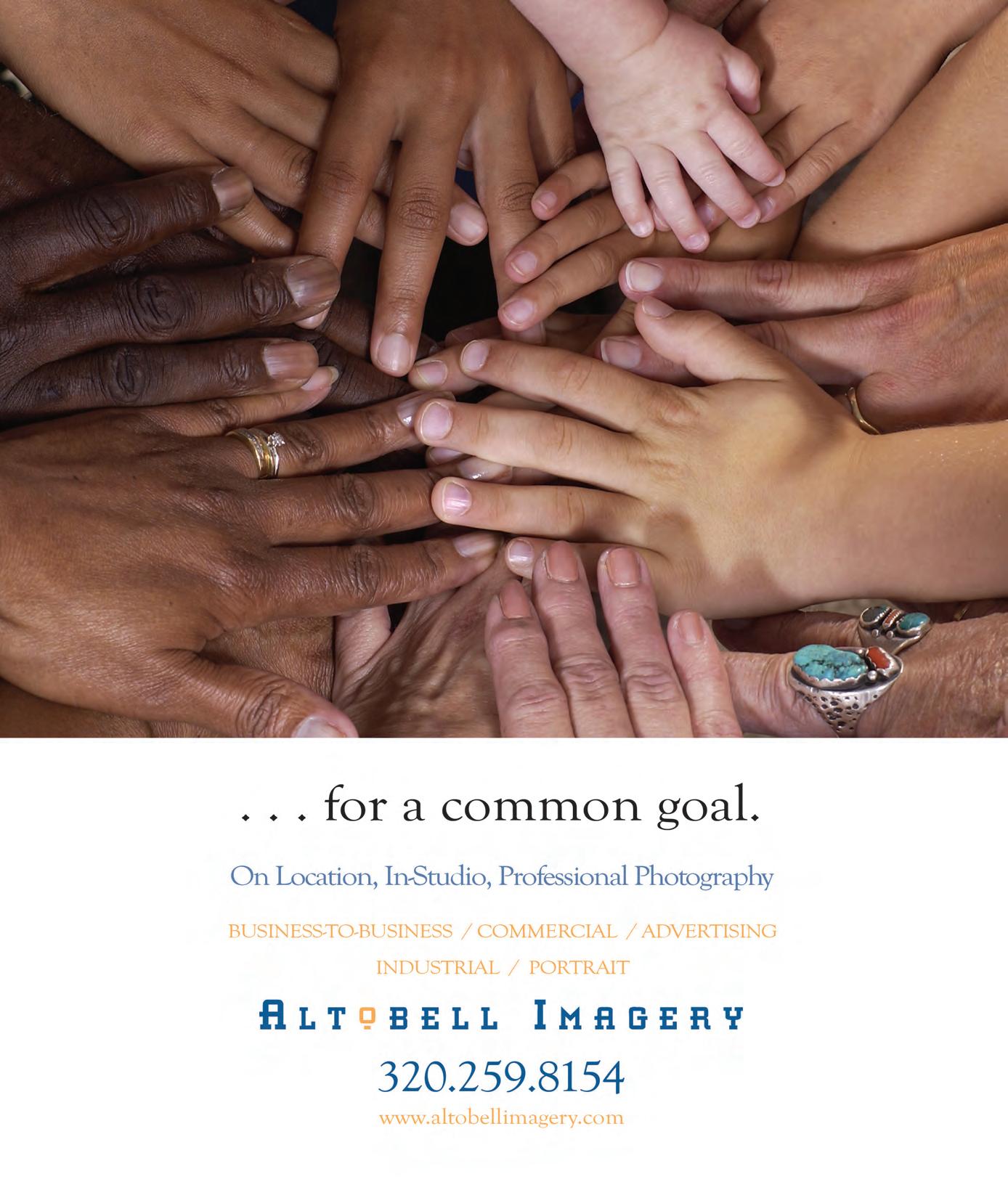

So goes the story of my grandfather as told by my mother, Pat Kasperson. My family’s American ascent is a source of great pride for me and for countless others in our nation of immigrants. The ethnic diversity is much more colorful today, but somehow the stories of poverty, prejudice, and perseverance continue.

With this issue of IQ Magazine, we hope to introduce you to our newcomers, reintroduce you to our established residents, and replace myth with truth. We hope to denounce racism and inspire forethought on central Minnesota’s demographic changes. Above all else, we challenge you to remember your own family story and consider what all of us have in common.

You’ll notice that I have replaced my photo with one of my mother. As she battles terminal illness, Mom and I are spending precious time together, reflecting on her life. I am blessed to have a mother who passes on her history, faith, and values while encouraging her children to follow her father’s footsteps to a better world. I couldn’t ask for a greater mentor and friend.

Enjoy the magazine.

Kathy Gaalswyk, President Initiative Foundation

P.S. Sincere thanks and recognition are due our magazine sponsors, who have proven their courage and leadership in support of this special issue on cultural diversity and immigration. Please see pages 11-13 for silhouettes of Brainerd Medical Center, St. Joseph’s Medical Center, Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe, and Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe.

>VOLUME 5, SUMMER 2007

INITIATIVE FOUNDATION

Executive Editor & Director of Communications /MATT KILIAN

Communications Associate / ANITA HOLLENHORST

PUBLISHERS

Evergreen Press / CHIP & JEAN BORKENHAGEN

EDITORIAL

Editorial Director / JODI SCHWEN

Assistant Editor / TENLEE LUND

ART

Art Director / ANDREA BAUMANN

Graphic Designer / BRAD RAYMOND

Senior Graphic Designer / BOB WALLENIUS

Production Manager / BRYAN PETERSEN

Lead Photographer / JIM ALTOBELL

ADVERTISING / SUBSCRIPTIONS

Business & Advertising Director / BRIAN LEHMAN

Advertiser Services / MARY SAVAGE

Subscriber Services / MARYANN LINDELL

IQ EDITORIAL BOARD

Initiative Foundation President / KATHY GAALSWYK

Centro Legal / GLORIA CONTRERAS EDIN (TRUSTEE)

Initiative Foundation / DAN FRANK

Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe / CHAIRMAN GEORGE GOGGLEYE

Bush Foundation / JOSE GONZALEZ

Initiative Foundation / CURT HANSON

Initiative Foundation / CATHY HARTLE

Initiative Foundation / DON HICKMAN

Maple Hill Garden/La Voz Libre / TIM KING

Minneapolis Foundation / VALERIE LEE

St. Cloud State University / DEBRA LEIGH

City of St. Cloud / BABA ODUKALE

Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe / MARY SAM (TRUSTEE)

Melrose Community Liaison / ANA SANTANA

St. Cloud School District / BRUCE WATKINS

Initiative Foundation 405 First Street SE Little Falls, MN 56345 320.632.9255 www.ifound.org

IQ is published by the Initiative Foundation in partnership with Evergreen Press of Brainerd, Minnesota. www.evergreenpress.net

For advertising opportunities, contact:

Lois Head 320.252.7348, lmhead@stcloudstate.edu

Brian Lehman 218.828.6424 ext. 25, brian@evergreenpress.net

Kristin Rothstein 320.251.5875, kristin@cpionline.com

◗

St.Cloud, Minnesota

(320) 255-3236

www.resourcetraining.com

WWhen nervous white people asked James Addington’s late wife (an African-American) what she prefered to be called, she revealed a calm smile and simply said, “You can call me Nadine.”

“If you don’t have to refer to someone by their race, color, or religion, don’t,” advises James Addington, training and organizational consultant with the Minnesota Collaborative Anti-Racism Initiative.

Many well-intentioned Minnesotans have become culturally hyper-sensitive to the point of paralysis. They avoid the subject altogether. According to Debra Leigh, a professor at St. Cloud State University and leader of the university’s Community Anti-Racism Education Initiative (CARE), this new reluctance to talk openly about race is standing in the way of cross-cultural conversation and discovery of common ground.

“White people stop dead in their tracks if they think they’re going to be identified as racist,” says Leigh. “One of the first things we did was to provide people with the language to talk about our experiences and about racism, without it being uncomfortable.”

It’s not just white people who feel uncomfortable.

“I was at a seminar on multiculturalism,” says John Lewis, the African-American president of the St. Cloud Chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), “where I learned that the term American Indian was preferred over Native American, which was the term I had been using.”

“Growing up in San Antonio we always referred to ourselves as Hispanic,” says Rogelio Munoz, executive director of the Minnesota Chicano Latino Affairs Council. “When I moved to Minnesota, I discovered that the preferred term here was Latino.”

As far as Addington is concerned, it’s not about being “politically correct”—it’s really a matter of being willing to live in a place of discomfort. “There are no sets of words that are always going to be appropriate,” says Addington. “The best advice is to see the person and not the color. On a personal level, if you’re not sure what words to use or what to call someone, the best thing is simply to ask them.”

React at IQMAG.ORG

Hispanic, Chicano or Latino?

If you answered Latino, give yourself a point. “Hispanic” was created by the United States government for census purposes. Mexican-Americans coined “Chicano” to describe themselves. Latino refers to any person coming from a country where a Latin language is spoken.

Bottom Line: Latino is the more general term and thus, the safest. In many regions of the country, it’s also the term most often used.

American Indian or Native American?

Believe it or not, the point goes to those who said American Indian. In 1970s school questionnaires, many white Minnesota kids checked “Native American.” Since they were born in America, they assume the term applied to them. To avoid further mix-ups, the Minnesota Indian Affairs Council voted to officially adopt “American Indian.”

Bottom Line: Neither term is particularly offensive, but American Indian is preferred, especially in formal communications.

African-American or Black?

Trick question—they’re both right—sort of. The United States Census Bureau uses both terms to include Americans of African ancestry as well as black immigrants from African and European nations and predominantly black, non-Hispanic Caribbean countries, such as Jamaica.

Bottom Line: Confused? Consider this: If you’re black, you can call yourself black (or whatever else you choose, for that matter). If you’re not, try using African-American as a more formal and respectful acknowledgment.

Asian-American or Oriental?

If you said “Oriental,” subtract all of your points and immediately dump it from your vocabulary. The U.S. Census Bureau uses the broad term, “Asian,” to refer to people who hail from no less than thirty countries. It also encompasses ethnic terms, such as Hmong.

Bottom Line: Unless you’re buying a rug, always use AsianAmerican. In the past, “Oriental” was often slung as a derogatory insult. For many, it’s still offensive. Hispanic or Latino? Even Rogelio Muñoz wasn’t sure.

BY BRITTA REQUE-DRAGICEVIC

BY BRITTA REQUE-DRAGICEVIC

T The recent “immigration debate” is nothing new, even though most of us are the descendants of immigrants ourselves. We still honor ethnic traditions. We pass down family histories of struggle and triumph with a sense of pride.

Throughout the 230-year history of the United States, citizens have often felt threatened when newcomers arrive.

Today, the subject of immigration elicits nearly as strong a reaction as abortion or capital punishment. Nearly everyone has an opinion, but snap-judgments are often influenced by media sound bites, isolated personal experiences and hearsay. We gathered up the blanket-statements that define conventional “wisdom,” and then we asked Juan Moreno, diversity and inclusion specialist at the University of Minnesota Extension, to help us set the record straight.

Are you sure you know what you think you know?

Conventional Wisdom: Most immigrants and refugees are here “illegally.”

Reality-Check: Don’t believe everything you hear. According to Moreno, the United States Immigration Service reports that about 800,000 immigrants and refugees legally enter the United States each year. Refugees are granted federal status due to persecution in their home countries.

Another 300,000 are here “illegally,” or without documents. The majority of these undocumented immigrants—six out of ten— cross our borders legally with student, tourist, or business visas. Their status changes to “illegal” only if they overstay their visas. Why use undocumented vs. illegal? Because immigrants are not criminals. United States residence without valid documentation is a civil offense.

Conventional Wisdom: Immigrants and refugees don’t pay taxes and they get everything free.

Reality-Check: “An estimated eleven million immigrants are working and paying—as a family—$2,500 a year more in taxes than

the average native-born family,” says Moreno, citing a study by Minnesota Advocates for Human Rights (MAHR).

According to a separate study by the American Immigration Lawyers Association, immigrants and refugees pay $70.3 billion each year in taxes and receive only $42.9 billion in public services. The Urban Institute reports that less than 5 percent of immigrants receive “welfare,” such as Supplementary Security Income (SSI). In the Midwest, only 3.3 percent of immigrants receive public assistance compared to 4.5 percent of the native-born population.

Conventional Wisdom: Immigrants and refugees don’t want to learn English.

Reality-Check: Although the 2000 United States Census indicated that 18 percent of Americans speak a language other than English at home, immigrants and refugees know that learning English is important for their safety, social network, job advancement, and cultural

survival. More immigrants than ever are enrolled in English Language Learner (ELL) classes, and many are put on waiting lists for months.

Conventional Wisdom: Immigrants and refugees drain the economy and take good jobs away from United States citizens.

Reality-Check: That depends on if your career aspirations include entrylevel meat-processing or manufacturing assembly. Many of central Minnesota’s large employers, such as Gold’n Plump Poultry, Jennie-O Turkey Stores, Electrolux, and Stearns, Inc. depend on immigrants and refugees to fill unskilled and labor-intensive workforce needs. Without willing workers, would these companies be forced to relocate? How would such a scenario impact the regional economy?

According to another MAHR study, immigrants and refugees actually create jobs by adding buying power to the local economy. Immigrants are also three times more likely than native-born Americans to save earnings and start new businesses, which account for 80 percent of all new jobs in the United States.

“Immigrant communities are revitalizing dying neighborhoods in cities and older suburbs, which would otherwise be suffering from middle-class flight and a shrinking tax-base,” adds Moreno. React at IQMAG.ORG

The news in the Brainerd Lakes region is good. We’re booming. In fact, our area is growing at twice the state and national rate. And, in order to offer our growing region the breadth and depth of health care service they deserve right here at home, St. Joseph’s Medical Center and Brainerd Medical Center have joined forces creating a nonprofit parent organization called the Brainerd Lakes Integrated Health System.

OUR PARTNERSHIP ALLOWS US TO:

• Share services, avoiding duplication and competition

• Expand our range of services, including a new interventional cardiology program

• Invest in new technologies

• Add up to 40 new physicians over the next 5 years

• Introduce new care models, including a hospitalist program

Our shared vision allows us to serve this area as an integrated health system that is highly responsive to your health care needs, offers an increasing range of services, provides stewardship to this community’s health resources, and continues to improve your health care experience, as well as the quality of our health care delivery.

The formation of Brainerd Lakes Integrated Health System, along with St. Joseph’s Medical Center and Brainerd Medical Center’s recent expansion projects, are just a few of the many ways we’re preparing for the future and keeping pace with our growing region.

The Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe is a sovereign, self-governing American Indian nation. Our reservation embraces four townships along the southern and southwestern shores of Mille Lacs Lake and includes other districts near Hinckley and McGregor. The Mille Lacs Band has more than 3,800 members, including nearly 2,100 members who live on the reservation.

The philosophy of sharing is vital to our culture. We share with other Indian communities through many initiatives, including the Minnesota Tribal Government Foundation (MTGF), which the Band cofounded. In 2005 and 2006, the MTGF awarded nearly $900,000 in economic development grants to northern Minnesota tribes and tribal priorities.

Last November, the Band sponsored the Northern Minnesota Reservation Economic Development Summit, modeled after the Mille Lacs Band’s successful regional economic development summits. For nearly a year, Band staff assisted the Red Lake Nation and the Leech Lake and White Earth bands of Chippewa Indians in planning this historic summit. More than 400 participants strategized how to create more economic development opportunities for rural, northern Minnesota tribes.

In addition to employing approximately 3,000 employees (of whom about 92 percent are non-Indian), the Band shares with non-Indian communities and neighbors in many ways. The Band recently constructed a $20 million, state-of-the-art wastewater treatment facility, providing clean water to more than 8,800 people in the region. Not only does the plant ensure that Band businesses and area residents do not pollute Mille Lacs Lake, but it prevented residents in the small town of Garrison (pop. 300) from receiving substantial fines due to failing septic tanks that were leaking sewage into the lake.

At the northern-most border of Mille Lacs County, the Band employs the largest law enforcement agency in the region, with 19 full-time, postcertified tribal police officers, providing for cooperative law enforcement

www.millelacsojibwe.org

between the Mille Lacs County and Pine County Sheriff’s departments and the Tribal Police Department. Previously, area residents would often wait nearly 45 minutes for response times. Today, help for Indians and our non-Indian neighbors is only minutes away.

The Band’s good neighbor policy is realized in many ways, including employment, economic development, environmental stewardship, and contributions to important causes that serve our area. We are proud of our home in East Central Minnesota and look forward to making a difference for generations to come.

The Leech Lake tribal government oversees the financing and operation of over 25 programs and divisions that serve and assist the Band and community members. There are many examples of how the Tribal Council is working to address issues surrounding cultural diversity within their programs and divisions as well as in the larger community.

Leech Lake Reservation was recently acknowledged when it was the first tribe to have their reservation flag hanging in the State District Court. “Having the Leech Lake flag in my courtroom will be a daily reminder of the sovereign status of the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe,” remarked the Honorable John P. Smith, Cass County District Court Judge.

Leech Lake operates three gaming operations: Northern Lights Casino, Hotel & Event Center in Walker, the Palace Casino-Hotel in Cass Lake and White Oak Casino in Deer River. These businesses currently employ people of Native American, Caucasian, Hispanic and Asian descent. With this diverse workforce it’s an ongoing process to train, teach, respect and educate staff on the attributes of the various cultures. The casino’s training departments have a train-

ing module for managers titled “Dealing with a Diverse Workforce” while the Leech Lake Tribal College offers an “Intro to Anishinaabe Studies” class which teaches diversity and history.

The casinos are great partners in helping further the area’s business climate as a portion of their revenues are invested back into the communities. All three take pride in the fact that their sponsorships & donations have assisted in the success of many events and organizations. White Oak Casino has helped to improve the annual Wild Rice Days by securing nationally-recognized entertainment. This has not only helped increase the popularity of the event, but has had positive economic effects on many area businesses.

In April, Northern Lights Casino was named “Business of the Year” by the Leech Lake Area Chamber of Commerce Community Champions. This award was based on the substantial contributions they have made in order to benefit many community organiza-

tions and increase economic opportunities in the Walker area. In recent years, the casino has been signing “big name” entertainment which has attracted more people outside of their primary market. The additional influx of people has helped to increase awareness that there are excellent and numerous recreational and business opportunities in the area.

www.llojibwe.com

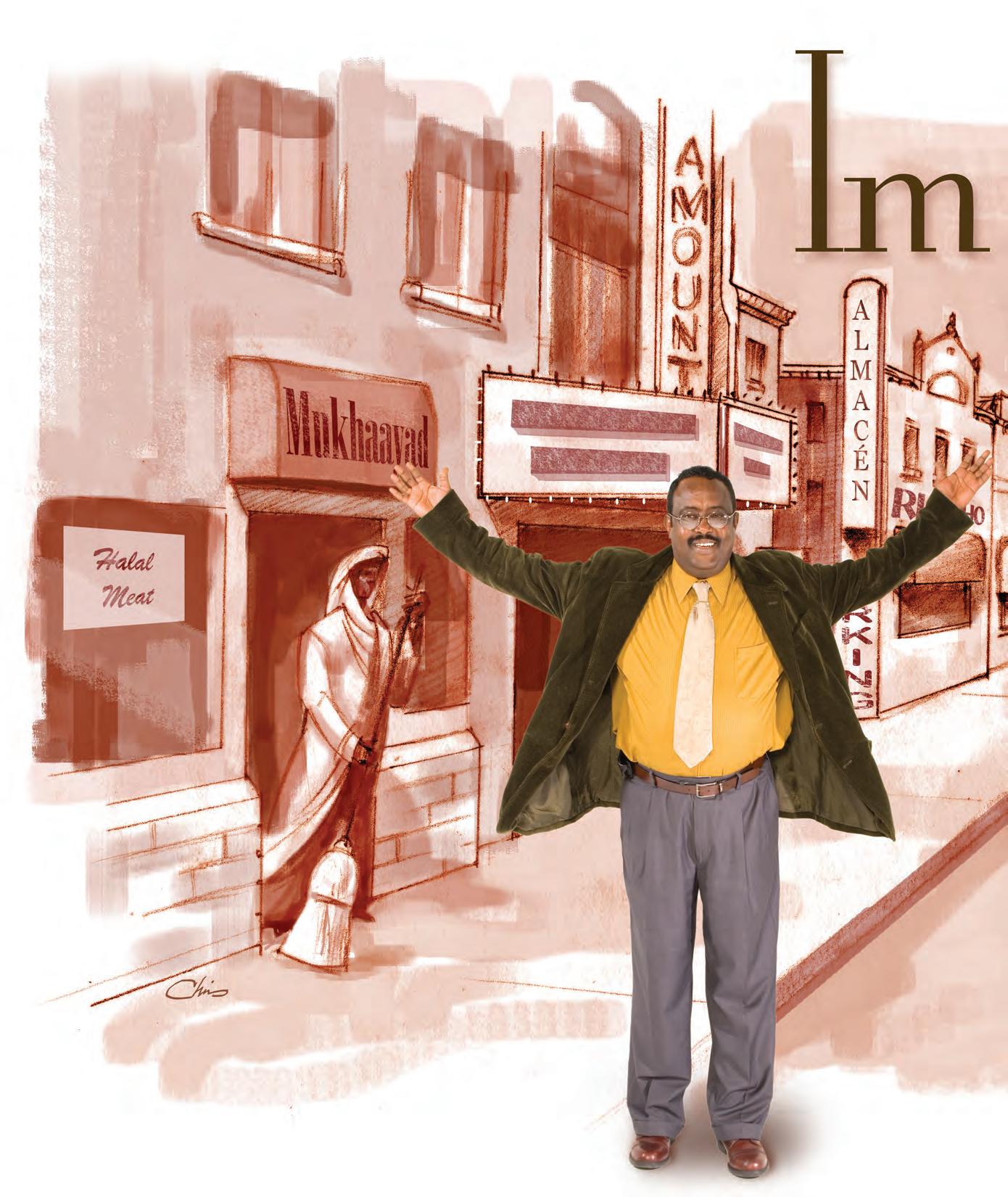

Hot summer winds drift through the open door and tickle bells at Halal Meat and Grocery. Nassir Yusuf smiles from behind the counter while Ali Badal chatters on the phone in a Somali dialect. By noon, the store has already sold out of anjeero, a traditional flatbread. They can hardly keep up with the demand for goat meat. Toward the back of the store, a stunning rack of shalwar clothing attracts curious shoppers. Welcome to central Minnesota.

Fast-forward to the year 2020— leaders of rural communities forecast increasing integration of races and cultures. Rather than just pass along the demographic numbers, we asked them to muse about the future. What will our communities look like? How will life be different? The following creative depictions of rural Minnesota life are based on real trends in the communities of St. Cloud and Willmar. Now, close your eyes and brace yourself. It’s 2020.

Although minorities comprise just 12 percent of Minnesota’s population, the number of foreign-born immigrants and refugees increased 130 percent between 1990 and 2000—mainly due to family reunification and jobs. By 2020,

Minnesota’s minority population is projected at 16 percent. Behind Christianity, the second most predominant religion in the state will be Muslim.

Around 2:45 P M., a clear male voice rings out in the downtown streets of St. Cloud. It is the adhan, the Islamic call to prayer. The streets are bustling, customers ducking in from a light rain to look over home-listings at Gonzalez Real Estate. Some seek treatment at the Tasi Wellness Center. A café owner excuses himself to find his prayer rug.

Posters advertise a stepping contest promoted by the St. Cloud Youth Commission. It was a huge hit last year, bringing in nearly one thousand teens to show off their African-inspired dancing talents and choreographed call-andresponse chants. The groups are judged

on their positive messages for youth.

The local quilting shop has a sale on paisleys—the material used for Muslim head-coverings. Several women can be seen just inside the shop windows pulling a large quilt taut on a frame. The smell of cinnamon rolls wafts from the open doorway.

A few blocks away, the St. Cloud Public Library is gearing up for a book sale; the electronic display outside advertises in both English and Spanish.

From the businesses and organizations to the Hmong reed-pipe performances at the Paramount Theatre, downtown St. Cloud has retained a vibrancy that defies an aging population. The Downtown Council is especially proud of its historic character.

By 2020, it is projected that 22 percent of Minnesota children under age fourteen will be nonwhite. In 2006, St. Cloud Schools reflected that demographic, with 21 percent minority students — over 10 percent African-American.

Between classes at Apollo High School, locker doors slam and students greet each

other as they rush through the morning. The overriding language is English, but greetings like Que pasa and Subah wanaagsan are called out in the hallway.

Signs on some of the lockers wish Abdi, KaYing Yang and Madison good luck in the upcoming cross-country meet. Most classrooms have more than one student named Mohammed or Diego.

Success in building an integrated and welcoming school atmosphere can be seen not only with students, but also the diversity among teachers, a student art exhibit of self-portraits, and a bulletin board welcoming guests in English, Spanish, Hmong, and Arabic.

Immigrant parents not only learn how to enroll children in school, but they also receive such information as where to get a doctor’s appointment, how to access city services, and the location of grocery stores near their home.

In 2010, the school district was instrumental in developing a volunteer network that guides families through the process of settling in central Minnesota. Newcomer information can now be accessed online, by phone, or at any of fifty organizations around the city.

The superintendent also notes the importance of state funding for new teacher development among retirees and bilingual citizens that helped reverse a desperate teacher shortage in 2015.

With thirty to forty languages spoken in the St. Cloud area, language is one barrier that has created gaps in student achievement, home ownership, and employment, notes Hedy Tripp, staff member for Create CommUNITY, a research and advocacy group in St. Cloud.

As eager immigrants graduated from schools and ESL classes, language isn’t such a barrier anymore.

An early sign of change in the workforce began in banking. Bilingual lending agents and tellers have transformed the banking experience for many newcomers. The same has occurred in clinics and hospitals. It’s not unusual to see business cards printed in several languages and allowances given for religious practice during the workday.

Among the thousands of Somali, Sudanese, and West African refugees and immi-

grants who now call St. Cloud home, there are professors, doctors, pilots, lawyers, engineers, politicians, accountants, and teachers. They couldn’t practice in the city when they arrived due to language barriers and incompatible certifications. Instead, they took jobs in manufacturing or meat-processing.

Now, they are finally moving back into their former professions, says Mohamoud Mohamed, founder and executive director of the St. Cloud Area Somali Salvation Organization (SASSO). “We are looking forward to paying this nation back and the best way to pay is to serve,” says Mohamoud.

When Nassir Yusuf came to St. Cloud in 2000, he didn’t know the language and recalls the difficulty of finding an apartment. “People would sleep in their cars outside of work until the employers helped to gain the landlords’ trust,” he says. He worked full-time and attended St. Cloud Technical College for surgical technology. He now talks proudly about his job at the local clinic and the home he just bought for his family in Sartell.

Minnesota State Demographer Tom Gillaspy said that if you want to know what Minnesota will look like in 2020, look at Willmar. In 1990, the United States census showed that Willmar’s minority population was 2 to 3 percent. In 2007, the minority population had grown to about 25 to 27 percent.

It was a significant shift that led leaders to develop a new language around immigration,

notes Les Heitke, the retired mayor of Willmar. Today, Mayor Camila Rodriguez leads a diverse city council.

“It took many small steps,” says Heitke. He recalls the year he walked into the Holiday Inn where a Ramadan festival was taking place. Among almost three thousand people he was one of a few whites. “I introduced myself and I felt very welcomed. I learned a lot from that.”

“There was a common apprehension that immigrants and refugees were problematic and they used up resources,” says Heitke. “But we chose to talk about opportunities and assets. Immigration has stabilized our school system, it has provided a needed labor force, and offers a strong political voice.”

At the Zion Lutheran Church in Willmar, members have invited local Catholics for a bilingual service of fellowship and song. Bienvenidos! A banner stretches across the chapel to welcome guests. There are several churches in Willmar populated by minorities, including a Somali mosque opened in 2010. A new soccer complex funded partly by the Jennie-O turkey plant opened in the summer of 2007 to sup-

port an emerging soccer program for youth and adults.

West Central Immigration Collaborative executive director Charly Leuze speaks with enthusiasm about the Willmar Area Multicultural Market. Instead of depending on low-wage jobs, minorities, and new immigrants have evolved into entrepreneurs within a centralized mercado where training and commerce live in harmony. Early in the century, the city of 19,000 had thirty-three minorityowned businesses.

As to why the community has led the way on embracing minorities, Heitke responds with another question: “What community doesn’t want thirty-three new businesses?” React at IQMAG.ORG

“If you want to know what Minnesota will look like in 2020, look at Willmar.”

—Tom Gillaspy, State Demographer

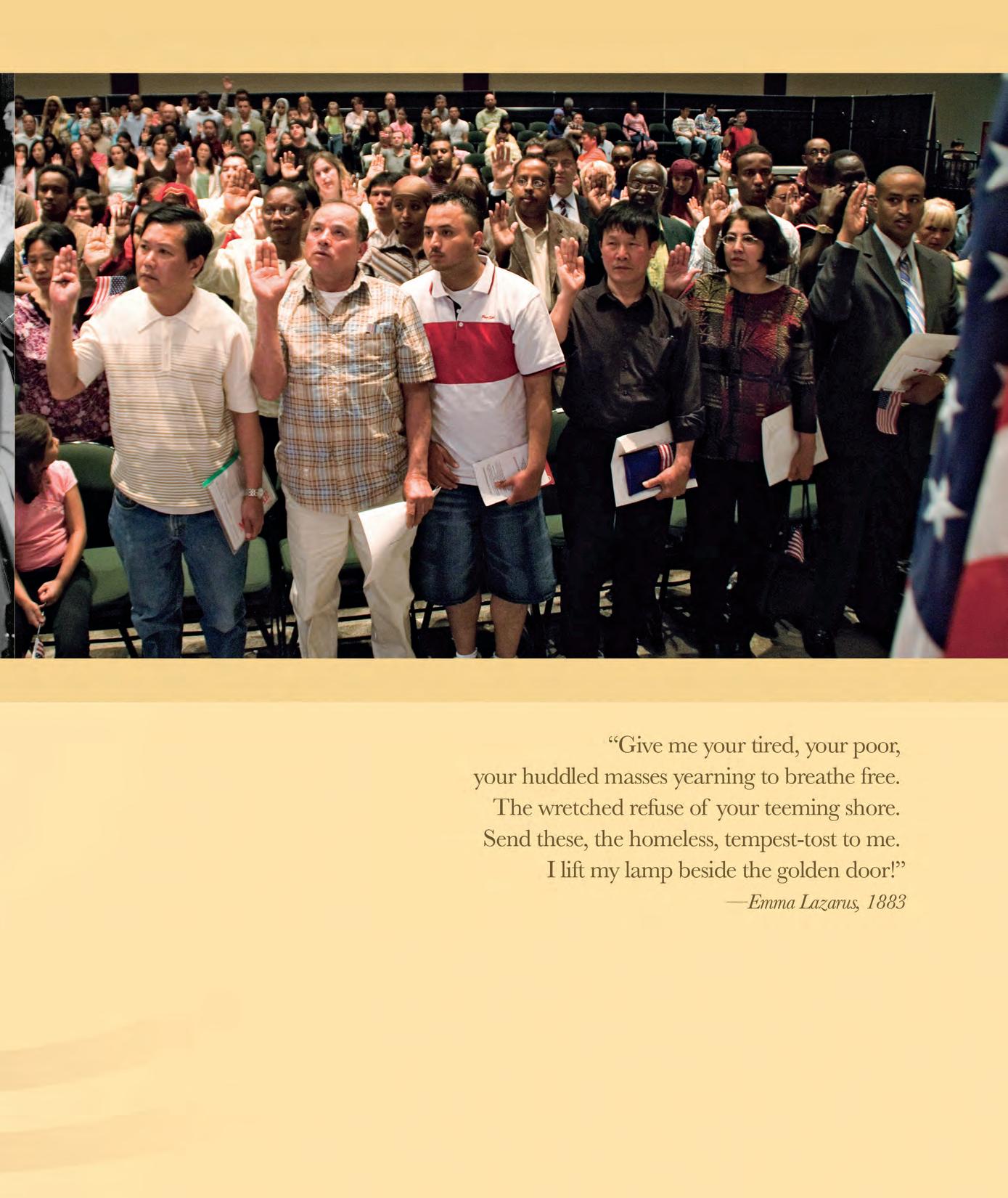

The words of poet, Emma Lazarus, are etched on an antique-bronze plate at the foundation of America’s most enduring symbol of liberty. They capture the essence of United States citizenship and hope for those thousands who desire freedom, safety, and opportunity. From its rich heritage of German and Scandinavian immigrants to the current influx of Hmong, Latino, Sudanese, and Somali, the more things change, the more things remain the same in Minnesota.

First, there are the definitions. The titles of immigrant and refugee, while often interchanged, are decidedly different. An immigrant is a person who is lawfully admitted to a country where he or

she intends to settle permanently. Those who are not lawfully admitted or whose permission has lapsed are referred to as undocumented. A refugee is a person who cannot return to his or her native country because of persecution.

From 2000 to 2005, nearly seventy thousand immigrants and refugees found their way to Minnesota, ranking it twenty-first in the nation. In 2005 alone, more newcomers arrived in the state than in the previous twenty-five years combined. Minnesota is second only to California in receiving those displaced by war, persecution, and natural disaster.

“Minnesota is quite exceptional,” says Tom Gillaspy, Minnesota’s state demographer. “The federal government has determined that Minnesota has a much higher capacity—good economy, social programs, and organizations— than most states for taking in refugees.”

With the exception of American Indians and some African-Americans whose ancestors disembarked from slave-ships, most Minnesotans are the descendants of waves of nineteenth- and twentieth-century immigrants. At its peak in 1900, more than 550,000 Minnesota immigrants comprised 29 percent of the population, compared to 260,000 immigrants at about 6 percent today. One hundred years ago, the top countries of origin were Austria, Canada, Finland, England, Germany, Ireland, Norway, Poland, Russia, and Sweden.

“They come because of the good job opportunities,

In the St. Cloud area alone, leaders estimate as many as 10,000 foreign-born residents.

In 2000, only two countries remain the same among the top ten: Canada and Germany. Rounding out the most recent list are China, India, Korea, Laos, Mexico, Somalia, Thailand, and Vietnam.

So why do immigrants and refugees want to live in Minnesota?

“It’s for the same reasons that Minnesotans want to live in Minnesota,” says Gloria Contreras Edin, Initiative Foundation trustee and executive director of Centro Legal, a St. Paul-based nonprofit law firm that assists Latinos. “They come because of the good job opportunities, good schools, affordable housing, and families that are already here. Sound familiar?”

According to The McKnight Foundation, many newcomers have also heard of high crime

rates in larger populated areas of Los Angeles, Chicago, and New York. They don’t want that for their families. Despite its landlocked geography and cold climate, Minnesota also has a tradition of helping new communities.

But “Minnesota Nice” only extends so far. Overt acts of racism are too common and many immigrants and refugees say they feel like problems to be “solved.” In 2002, vandals spraypainted a Somali market, mosque, and cultural center with the message, “Get out of St. Cloud, niggers.” Later, perpetrators set fire to a nearby storage shed.

“Unfortunately, African refugees never knew they were black before they came to America,” says Geneva Cole, a former leader of the St. Cloud Area Somali Salvation Organization (SASSO). “In Somalia, they were

good schools, affordable housing, and families that are already here. Sound familiar?”

one culture, one language, and one religion. They never experienced somebody judging them by the color of their skin and some still don’t complain because they are so grateful to get a second chance at life.”

Misinformation also persists that undocumented immigrants are a knee-buckling burden on the state’s economy and taxpayer dollars. In 2005, the Minnesota Department of Administration issued a report to Governor Tim Pawlenty estimating more than eighty thousand “illegal” immigrants drained $176 to $188 million annually due to public education, health care, and incarceration costs.

In 2006, the Minnesota Office of the Legislative Auditor published a rebuttal that suggested the estimates were incomplete, partially because they didn’t factor in offsetting tax revenues. It also cited economists’ conclusions that immigration’s longterm economic benefits outweigh its shortterm impacts.

A report by the Hispanic Advocacy and Community Empowerment through Research (HACER) estimated that undocumented labor is worth at least $1.56 billion to the Minnesota economy and if it were suddenly removed, Minnesota’s economic growth would decline by 40 percent.

“To get a foothold here, newer immigrants are filling labor-intensive workforce needs, such as in manufacturing and meatprocessing, where they can get by while they learn the English language,” adds Edin. “This workforce is essential to central Minnesota’s economy. Immigrant entrepreneurs are helping revitalize downtowns in Long Prairie and Melrose.”

Immigrants and refugees also possess surprising economic buying power. According to census-based research by Concordia University’s Dr. Bruce P. Corrie, diverse cultures added more than $99 million to the economy in the St. Cloud metro area. In the Todd County cities of Long Prairie and Staples, Latinos presumably contributed more than $8 million.

Many immigrants and refugees, however, share monumental challenges to learn English as well as the homesickness and depression that can set in from being in unfa-

miliar surroundings. They can also experience unrelenting pressure to adapt, find work, and navigate a new social structure. Many newcomers, who have narrowly escaped traumatic violence and starvation, have again become targets as divisive debates rage on.

Mohamoud Mohammed, a Somali refugee and SASSO’s executive director, spent five years in a Kenyan refugee camp competing with 100,000 people for humanitarian rations. He witnessed daily death from starvation and diseases such as meningitis.

“The children died quickly,” he remembers. “Nothing is worse than starvation. It’s worse than hell, I think. I don’t believe that anybody who dies of starvation will go to hell.”

Mohammed’s only way out was by obtaining a visa to anywhere, filling out dozens of international applications in a process that had the logic of a lottery. If one family member was fortunate enough to get one, he or she departed immediately and began their mission to reunite in a new country. In 1999, when Mohammed finally acquired a visa to the United States—eventually St. Cloud—he left his wife and five sons behind. His wife perished in 2002.

According to Holly Ziemer, communications director for the Center for Victims of Torture, many refugees suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder, physical pain, nightmares, anxiety, depression, and thoughts of suicide. They might limit their exposure to news, avoid police or people in positions of authority, or isolate themselves from the public or unpredictable situations.

“The result is that they might have difficulty concentrating, making it harder to learn a new language or a new job,” says Ziemer. “By definition, refugees are resilient. They possess strengths, internal resources, and abilities that enable them to survive life-threatening situations we can hardly imagine.”

“We left our country with empty hands,” says Mohammed. “I felt empty, like I had a good dream that I could not let go, and I did not know where I was going. Now, I support the course of America, and I will sacrifice everything I have for my second homeland.” React at IQMAG.ORG

This includes mass media, microwave ovens, health insurance, credit scores—everything we take for granted. They often distrust government or anything that resembles government. Language is an enormous barrier.

American consumerism—our “want-wantwant/buy-buy-buy” culture is foreign. Former professionals or skilled workers rarely find employment that matches their past wages or training. Wages are low.

Many come from homogeneous cultures. They are not prepared to become part of a highly integrated, mixed culture where they are in the minority. Racism can be a surprising reality of life.

American individualism is foreign. Many come from extended family cultures, living together, pooling resources, and supporting relatives abroad. School children soon know more about their new surroundings than their parents, so they are less inclined to follow rules and family customs.

Refugees are often the victims of war, torture, starvation, and persecution. They have left everything they have ever known behind, including loved ones. Dealing with the aftermath makes their transition even more difficult.

Source: The McKnight Foundation— Immigrant Gateway: Framing the Issue

“If I fail at something, Americans might think that all Mexicans are failures.”

—Ulises Ayala

When he was just twelve, Ulises’ parents and three sisters made a heartrending decision to pursue their dreams north of the Mexican border. They exchanged tight embraces, and then left him behind to finish the sixth grade. If all went according to plan, the Ayalas would be reunited after the school year. If things went terribly wrong—well, those thoughts were unbearable.

The school year ended and Ulises had no word. Then it came. Scared and alone, he boarded a bus to another city. His aunt paid a “coyote,” a human smuggler who would take him to California. He endured the perilous journey for a month—crammed in the concealed floor of a car, swimming a sewer canal, and a week alone in a strange apartment. Ulises found his family, but what he found shocked him. They were living in one room, barely surviving in the American Paradise.

Ulises toiled through high school classes and collected aluminum cans to help out. Without legal status, he was not eligible for college aid, but still managed to complete two years. He married and moved to join his wife’s relatives in St. Cloud, processing chickens for a local poultry company. He worked his way up to management, joined the Minnesota National Guard, and is pursuing a degree in child psychology. He will finally become a United States citizen in summer 2007.

Mexico, Central and South American countries including Cuba, Colombia, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Puerto Rico. Primary language is Spanish. Most are Roman Catholic.

More than 187,000 Latinos reside in Minnesota. 60 percent are native-born United States citizens. Latinos are the fastest growing ethnic group, with a nearly 29 percent increase from 2000 to 2005. One in three is under age eighteen.

Latino populations are growing in Long Prairie, Melrose, St. Cloud, and Sauk Centre, among other cities. Many seek a way out of poverty and crime-infected communities. Like immigrant generations before them, they simply want employment opportunities and a chance to establish a better life for their families.

In Minnesota, Latino buying-power rose to $3.1 billion in 2003. More than one thousand Mexican-American businesses operate in Minnesota. Many are surfacing in rural communities to serve other immigrants and revitalize downtown areas. Cornerstone poultry and meat-processing companies like Jennie-O and Gold’n Plump rely on Latinos to help fill vital workforce needs.

In spite of their economic contributions, 18,000 to 45,000 undocumented Latino workers live in Minnesota’s shadows, with many unable to obtain healthcare, basic social services, or licenses. Many must overcome low wages, hard-tonavigate systems, civil-rights abuses, limited affordable housing, and childcare shortages.

“There are lots of stereotypes. We don’t just eat tortillas and beans and do manual labor. People think we don’t go to college or believe in God. They’re not used to seeing us, so they feel uncomfortable. We’re just like you. We want an opportunity to make a better life for ourselves.”

Sources: The Minneapolis Foundation, Minnesota State Demographic Center, Chicanos Latinos Unidos En Servicio

“Our people are tired of war. We hope Americans will learn to accept us as people.” —Mohamed Yusuf

Mohamed Yusuf was just seventeen when war found his village and shattered his life. Mohamed fled south to a refugee camp in bordering Kenya. With no word from his parents or thirteen younger siblings, he spent the next eleven years in a canvas tent, enduring relentless heat, starvation, and boredom. Every two weeks, he welcomed a small packet of flour, oil, sugar, corn, and charcoal—no meat.

In 2000, the United States accepted his refugee application; destination, Minnesota. Reunited with his wife and her parents, Mohamed tried hopelessly to trace his parents through the American Red Cross. Like thousands of others, he was put on a waiting list. His prayers were answered when the phone finally rang in 2006. His father, four brothers, and one sister arrived in Minnesota from another Kenyan refugee camp the same year.

Earning United States citizenship in February 2007, Mohamed now works as a refugee program manager for Lutheran Social Services in St. Cloud. He supports his wife, five children, and siblings. His mother and remaining brothers and sisters are still waiting.

Somalia, a coastal country on the northeastern “horn” of Africa. The primary language is Somali. The vast majority are Sunni Muslims.

At more than 25,000 and growing, Minnesota has the largest population of Somali refugees in the United States. More than 3,500 live in the St. Cloud area. About one-third came directly from refugee camps. Somalis are divided into close-knit clans such as the Darod, Dir, Isaq, and Digil.

Most Somali refugees wish to find new homes and reunite with their families somewhere in the world. Entry-level employment opportunities, welcoming neighbors, and the presence of other Somalis are all factors in choosing central Minnesota. Returning to Somalia is impossible due to natural disasters and civil war between sixteen rival factions.

Many Somalis feel deep patriotism and appreciation for United States generosity and seek ways to give back. Islamic practices include giving 2.5 percent of one’s annual income in cash or in-kind to charity. Somali workers fill critical labor force needs in meat processing and manufacturing that don’t require English proficiency.

Many Somalis have found it difficult to practice Islam and still integrate into American life. This requires praying five times per day and not charging or paying interest on loans. Women must wear the hijab head-covering. Former Somali professionals often accept unskilled positions, which means their training and experience doesn’t benefit Minnesotans. Language barriers and culture-shock has multiplied the need for translation and liaison services.

“In Somalia, the more children you have, the more you are respected. We had no work or no school in refugee camps. Somalis like to work overtime, we work holidays and we don’t take vacations. We must be allowed to pray. Somalis will quit their jobs over that, no matter how much they need the money. We ask for more help with language and more patience.”

Sources: The Minneapolis Foundation, Minnesota State Demographic Center

“We are all the same. We all want a chance to pursue happiness.”

—David Thao

David Thao, a Minnesota-born citizen, never experienced the horrors of America’s “secret war” against communists in Laos. His mother did, and at times, she reminds him of their family’s terrifying escape. She recalls a wealthy life in Laos until communist soldiers arrived and forced one of her older sons to join them. The entire village set off on foot toward the safety and freedom of Thailand. It took more than a month.

Families were separated. Children died. Mothers were forced to drug their babies to keep them from alerting enemy soldiers. Gangs of soldiers raped women. Many Hmong refugees drowned while crossing the Mekong River into Thailand.

Thai officials ushered them to Camp Nong Khai, a refugee camp where they earned passage to the United States, a place where David’s family felt they could finally regain peace and pursue happiness. David carries this history and feels pressure to honor his family by succeeding as a student at St. Cloud State University.

Hmong is a general term that refers to people from mountainous regions in southeast Asia—Burma, Laos, Thailand, Vietnam, and parts of China. Hmong belong to one of eighteen clans. Primary languages are White and Green Hmong, dialects similar to British and American English. About 70 percent practice shamanism; 30 percent are Christian.

More than sixty-thousand Hmong residents live in Minnesota, the second largest population in the United States (California). In central Minnesota, Hmong populations are growing in communities such as Buffalo, Elk River, St. Cloud, and Taylors Falls.

Probably for the same reasons you live here—great neighborhoods and schools, quality job opportunities, pristine natural resources, and progressive attitudes.

Through networking and formal associations, Hmong people have been among Minnesota’s most successful entrepreneurs. More than four hundred Hmong-owned businesses now exist in the Twin Cities area, which have helped to revitalize downtown areas of St. Paul.

Several Hmong are second- or third-generation citizens, although they are often treated as new immigrants. For many, language is no longer a barrier. However, intergenerational conflicts often occur as children learn English and develop fondness for American culture while elders seek to preserve traditional language and customs.

“Large families are the most integral part of our society. We share success and help each other. Previous generations did a lot of manufacturing and labor jobs; now many of us are moving into more prominent positions. Today, most Hmong can speak English just as well as any American, but there still is a lot of miscommunication between the whites and Hmong. We want to exchange ideas, culture, and understanding of one another.”

Sources: The Minneapolis Foundation, Minnesota State Demographic Center, Hmong Cultural and Resource Center

“I love America. Here, I don’t worry. Here, I am safe. It is very good life here.”

—James Puotyual

Gazing down with gentle eyes, James Puotyual is a striking giant. When he arrived in Minnesota as a refugee of Sudan, he weighed only ninety-five pounds. James knows too well the civil war, famine and massive human suffering that have marred his nation’s existence since 1956, most recently in the western region of Darfur. It was civil war that forced him and thousands of Sudanese to flee villages to neighboring Kenya.

James survived for a year in a refugee camp. Life in the camps was only survival—scarce food, no school, and no work. More than a decade later, he cannot forget the wailing, the hollow pains of starvation, and the dead bodies on the ground. On those rare days when there was no tragedy, there was scorching heat and endless boredom.

When James finally was processed as a refugee in 1994, he arrived in Minnesota with two goals: reestablish his life, and return to Sudan to help his people. He serves as a lay-pastor and aspiring missionary at Bethlehem Lutheran Church in St. Cloud. Every month, he sends $500 to support his family in the refugee camps.

Sudan is Africa’s largest country in its northeast region, which borders Egypt and Ethiopia. The largest number of United States refugees are from southern Sudan, representing at least ten different ethnic groups. Several languages are spoken, including Arabic, English and tribal dialects. About 70 percent are Sunni Muslims, although many central Minnesota Sudanese are Christian.

An estimated five thousand Sudanese refugees reside in Minnesota. About 350 live in St. Cloud, according to Puotyual. Mankato and Anoka County are also home to Sudanese families. In the late 1990s, Minnesota’s Sudanese population may have peaked at six thousand, but many moved to Iowa and Nebraska for meat-packing jobs and affordable housing.

Like Somalis, most Sudanese refugees wish to find new homes and reunite with their families somewhere in the world. Entry-level employment opportunities, welcoming neighbors, and presence of other Sudanese are all factors in choosing central Minnesota. Many, like Puotyual, would eventually like to return to Sudan.

As a relatively new immigrant group similar to those from Somalia, workers fill critical labor force needs in meat processing and manufacturing that don’t require English proficiency. As they gain a stronger foothold in the United States, their economic contributions and buying power will increase.

Language and culture-shock are major barriers. Puotyual says that many Sudanese women don’t speak English or learn common skills such as driving a car. Like the younger Hmong generations, Sudanese children often prefer American culture to Sudanese, which leads to intergenerational conflicts over identity and morality.

“I miss my country very much—the celebrations, the running, the river. We are very close to our families. Sometimes eight to ten families are living together. We wish for Americans to reach out, to make relationships with us. Come to church with us and sing together!”

Sources: James Puotyal, CIA World Factbook, Minnesota State DemographicCenter

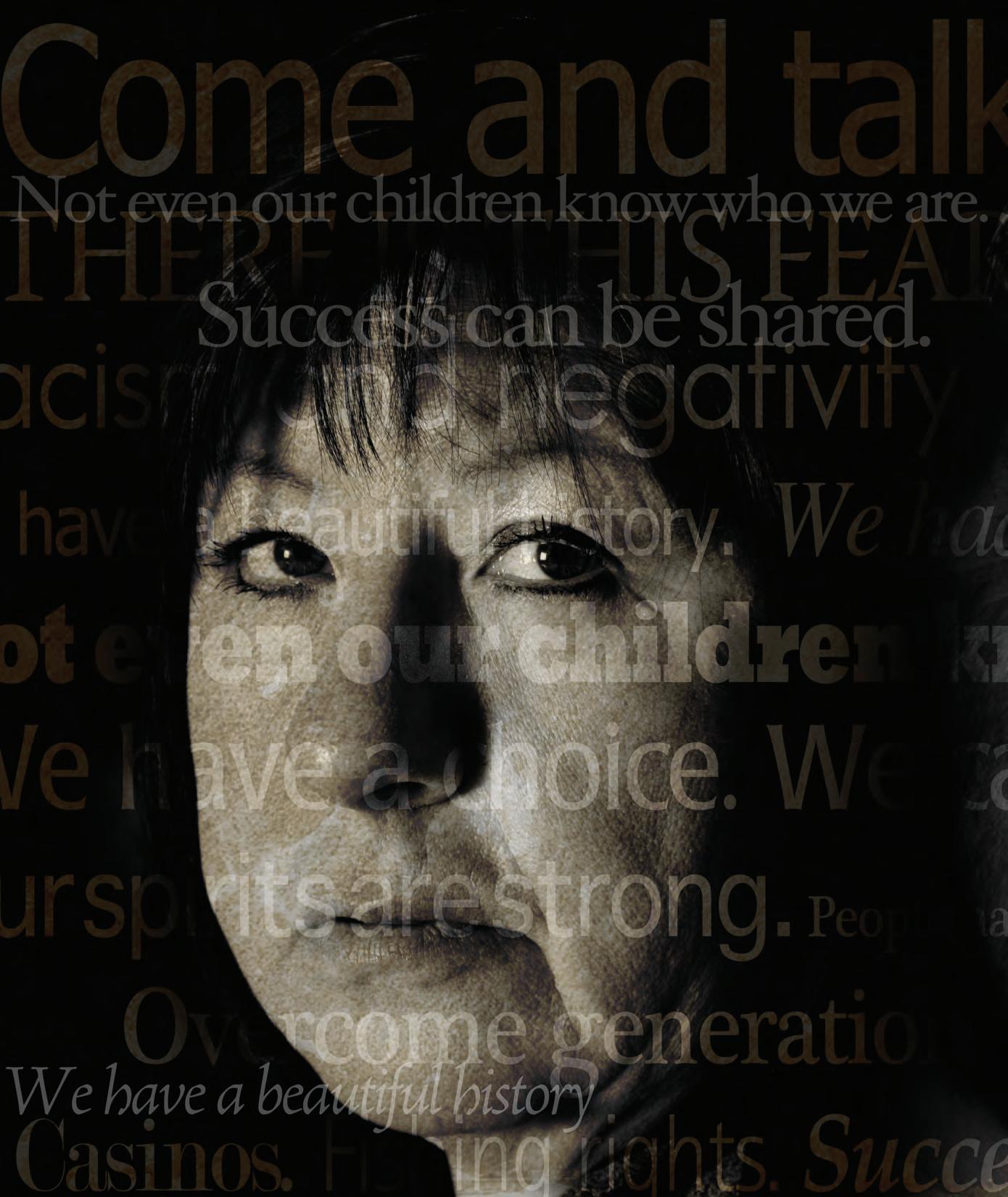

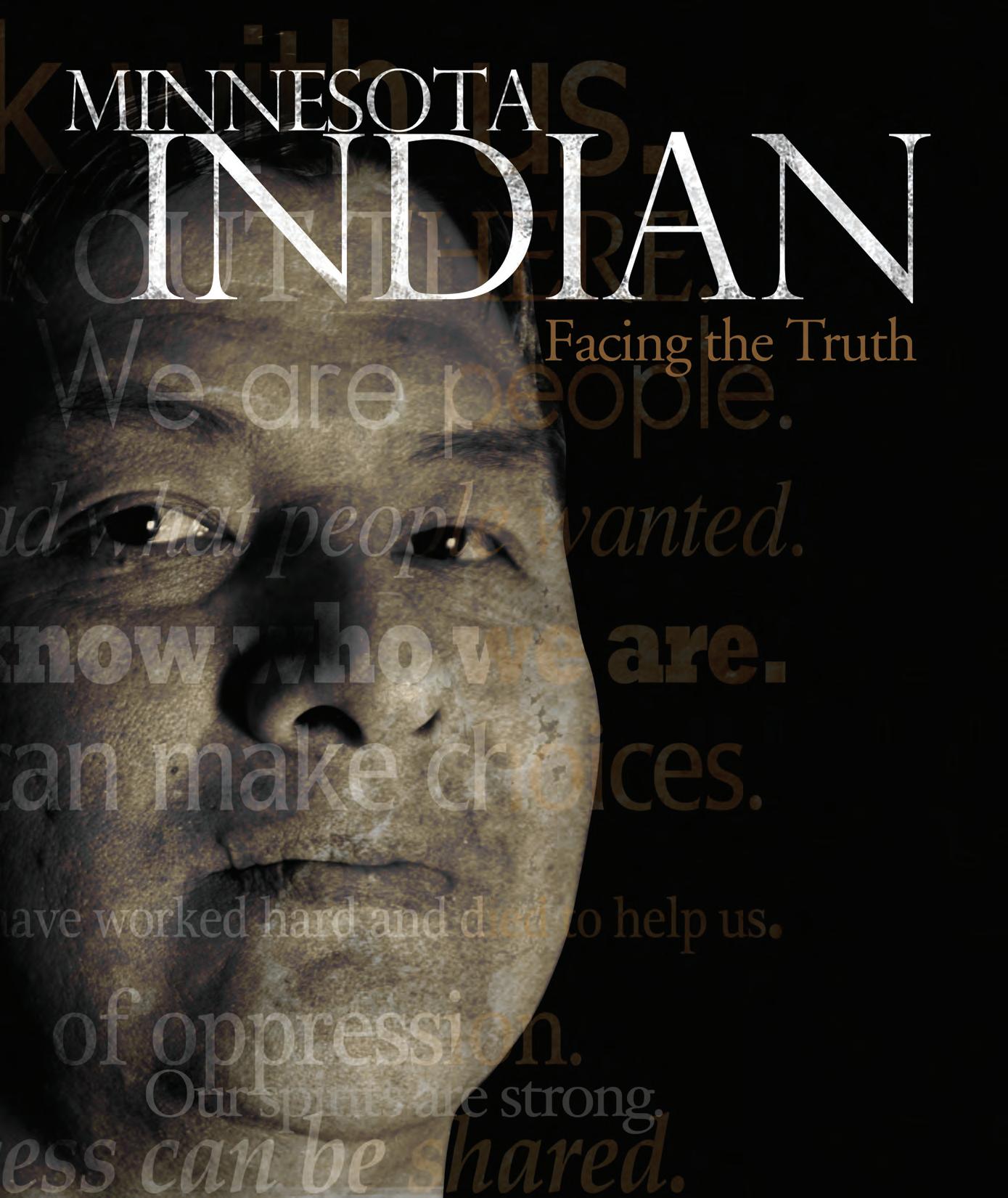

As a small boy, George Goggleye, Jr. climbed high into the oak trees that lined the shores of Leech Lake. With a pounding heart, he watched as the canoes pushed off and sliced the water toward the rice harvest. It was a stirring panorama, an Ojibwe legacy that someday would be his to hold and bequeath to others. In our world of crooked lines drawn somewhere between race and the scars of history, native and white Minnesotans have instead shared a voyage into shadowy waters. The truth is the way out.

Some whites no longer remember the acts of their ancestors, nor claim responsibility for them. Generations of American Indians bear shame and hatred for simply being who they are. Both no longer know why the racism and fear continue. According to Ojibwe leaders, not knowing could be the deepest problem.

“I wish people weren’t afraid to come and talk with us,” says Goggleye, Jr., now the chairman of the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe. “There is a fear out there that exists and that prevents them from learning who we are. People hide behind racism and negativity. Not until they meet us will they know that we are people.”

“We have such a beautiful history,” whispers Melanie Benjamin, chief executive of the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe. “We had what people wanted—lakes and timber—then it was taken away. Now, we are at a place where not

even our children know who we are.”

In the 1800s, as European settlers moved west and north into Minnesota, they encroached on five thousand years of Ojibwe and Dakota history. A multitude of factors played into the assumption that the land was there to be taken. Ojibwe culture was foreign. Their language was strange. Their ways were “uncivilized.” Their skin was dark. They were not Christian.

The fear, hatred, and suspicion of today are well-rooted in the earliest beginnings of the United States. Conquering the land was part of being a pioneer.

“There is this fear out there that exists and that prevents them from learning who we are. People hide behind racism and negativity. Not until they meet us will they know that we are people.”

—Chairman George Goggleye, Jr.

Most everyone knows something of the crimes. The Ojibwe people were killed, threatened, and forced to march hundreds of miles from all they knew. Children were abducted, sent to boarding schools, and forbidden to know their language or culture. Identities were lost in time.

As recently as the twentieth century— October, 1901— the outspoken S.M. Brosius penned this excerpt from an Indian Rights Association article titled, “The Urgent Case of the Mille Lacs Indians”: “It is stated that about 100 Mille Lacs

Indians were ejected from their homes . . . by the sheriff of Mille Lacs County, and their dwellings and property burned or otherwise destroyed, owing to white settlers having some semblance of title to the lands occupied by the Indians for generations.”

While history must be remembered, Goggleye, Jr. encourages tribe members not to dwell on it. “Yes, we have been an oppressed people,” he says, “but that is not totally responsible for the social problems that exist. I try to teach my children about the challenges of existing in both worlds—honoring our heritage and being a part ofthe community. Today, we have a choice and we can make choices.”

Finally, there are signs of progress for the Ojibwe: youth programs, retirement plans, burial insurance, and tribal-owned colleges, to name a few. The Bands have steadily moved forward, often with immense resistance, to build a brighter future. “Our spirits are strong,” says Benjamin. “A lot of people have worked hard and died to help us progress.”

In the early 1970s, United States courts recognized Ojibwe treaty rights to regulate their own hunting and fishing. In a state brimming with outdoor sports enthusiasts, this decision fueled a venomous controversy that remains a raw source of racial tension today.

“The general fear was that the tribes would deplete the natural resources by commercial harvesting. This was especially a concern with netting,” says Paul Swenson, tribal liaison offi-

cer for the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (DNR). “Essentially, the Bands gave up their netting rights in exchange for managing natural resources on their reservations without state regulation.”

Today, tribal conservation codes strictly enforce the amount of fish and game their members may harvest. Contrary to conventional wisdom, Ojibwe members cannot fish, hunt, or gather without limit. In fact, both Goggleye, Jr. and Benjamin cite natural resource preservation as among their highest priorities.

“It’s worked out well,” says Richard Robinson, director of the Natural Resource Department of the Leech Lake band. “Our conservation code is similar to the state’s regulations and we have a very good working relationship with the DNR. Both the tribal and DNR game wardens have been cross-deputized, so we can enforce each other’s natural resource laws.”

The 1988 legalization of Indian gaming by the State of Minnesota provided the Bands with an economic engine that propelled them decades closer to financial independence. It also provided access to the inner circles of political and business leadership. Although gambling abuse poses ongoing challenges, the economic benefits have transformed the reservations as well as neighboring communities.

The Leech Lake and Mille Lacs Bands both own and operate financially successful casinos, restaurants, hotels, event centers, gift shops, and gas/convenience stores. Mille Lacs also owns banks, travel agencies, and cinemas. The gaming industry alone brings $100 million to the

Leech Lake area and $429 million to the Lake Mille Lacs area, according to Band reports.

“Gaming has allowed us to operate on less government money,” adds Goggleye, Jr. “The revenue allows us to be more productive in a more positive manner. During the last three years, we’ve even been able to establish an investment portfolio for the tribe.”

The 2005 University of Minnesota Indian Gaming Study estimated that the tribal gaming industry has created nearly thirteen thousand jobs, mostly in low-income rural areas. The Leech Lake Band is the largest employer in Cass County with 1,455 employees. Goggleye, Jr. estimates that half are non-Indians. The Mille Lacs Band employs 2,900 at its Grand Casinos in Mille Lacs and Hinckley, which comprises 12 to 13 percent of the workforce in Pine and Mille Lacs Counties. Ninety-two percent of these workers are non-Indian.

“We tax our gaming facilities and that money is used for funding our government and social programs,” says Benjamin.

The stereotype of the wealthy Minnesota Indian who collects a fat check every month couldn’t be farther from the truth. Of the 224 United States tribes that operate gaming facilities, only seventy-three provide per capita money to their members. These do not include the Mille Lacs nor the Leech Lake Band.

“Most of our profits go right back into our payroll and operating capital,” says Leech Lake gaming director Daniel Erickson. “The tribe has budgeted $10.5 million annually to go back to the tribal government; the rest is reinvested into the casinos.”

Despite the economic success, American Indian families are working to overcome higher per-capita rates of poverty, drop-outs, substance abuse, depression, and domestic violence. In central Minnesota, the Leech Lake and Mille Lacs Bands are taking a longer-term approach to addressing social challenges, by investing in children and youth.

“We love our kids. We are working to make sure they have a strong knowledge and identity,” says Benjamin. “Oftentimes, oppression leads to depression, which in turn leads to social ills and poverty. We are working to provide education, to assist them in overcoming generations of oppression.”

Another looming challenge remains a lack of sovereign government recognition.

“We’re working toward more governmentto-government relationships with Minnesota,” says Goggleye, Jr. “I’m very optimistic with how the state is responding. The treaties are starting to be honored now.”

“When I look back and see what we have accomplished,” adds Benjamin, “I see successes that have benefited many communities. I’ve always wondered why some people fight us so hard when success can be shared.”

React at IQMAG.ORG

Chief Executive Melanie Benjamin: “We love our kids. We are working to make sure they have a strong knowledge and identity.”

By Tim King and Britta Reque-Dragicevic Photography by Jim Altobell

By Tim King and Britta Reque-Dragicevic Photography by Jim Altobell

Marching bands blared, kids chased candy on the hot asphalt, and proud Ojibwe veterans waved from their red, white, and blue float. The 2006 Isle Days parade was a day to remember. And a day to forget. The float rolled past a local bar. “Go home!” someone shouted. “We don’t want you here!” A lump formed in the throat of Allen Weyaus, a Desert Storm veteran. Was this really happening? He swallowed his fury and humiliation. His Uncle Kenny, who fought in World War II, stared straight ahead, expressionless. “Get the (expletive) out of here!” rose another faceless voice.

Then,

Allen barely had time to duck. A dark object shattered the windshield of the truck that towed the float. David Sam screeched the brakes. The parade stopped. No suspects. No apologies. No doubt that racism still breathes in Minnesota.

Weyaus had hoped 2006 might be different at the Isle Days Parade. Different than their first year or their second. He could still hear the parade announcer laughing as their float had passed the first year.

“You’d think the Indians could afford a better float with all the money they get from the casino,” the announcer had said in the loudspeaker. Despite it, the veterans had come back the second year only to face the sound of war whoops and cackles. Undaunted, they were not going to let a handful of people dishonor their military service.

“We take our float to Garrison, Brainerd, Aitkin, Onamia, and Isle each summer,” says Weyaus. “Most communities have treated us with respect.”

Weyaus, thirty-seven, is a member of the American Veterans Association Post 53, which is comprised of Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe and non-Indian members. Weyaus served with the United States Navy during Operation Desert Storm in the early 1990s. He is part of a legacy of thousands of American Indians who have served in the United States military. “We are veterans. We did our job and we are proud of that. With our float we want to honor all veterans.”

Unfortunately, for a state known for its “Minnesota Nice” attitude, the reality for many Minnesotans of color is far from it. And for military service, which is usually a

source of community pride, at the Isle Days Parade it was obliterated by the power of racial prejudice. It is individual prejudice that sculpts racism.

What is racism, exactly? James Addington of the Minnesota Collaborative Anti-Racism Initiative (MCARI) defines it as race prejudice supported by systems and institutions that serve white people advantageously. In other words, the misuse of power in relation to race.

“The United States systems and laws were originally designed to serve one group of folks—at that time, a white population,” explains Addington. “You might liken racism to the default settings in software. It’s what we keep going back to unless we make a conscious effort to change the settings in ourselves and our society.”

Addington works as an anti-racism trainer and consultant for institutions and organizations across Minnesota. Born to parents of Choctaw Indian heritage, he first became aware of racism when he learned that in his native state of Arizona it was illegal for white people to marry anyone of Choctaw descent. His parents had married anyway. Later, he became impassioned by the civil rights movement of the 1960s and eventually married his late wife, Nadine, an African-American woman.

“We soon learned as a couple, that we would have to help people understand how

racism operates.” Jim and his wife were founders of MCARI in the early 1990s.

Racism takes its form in many shapes and sizes across America and no community is immune to it. Central Minnesota continues to struggle with it. Communities such as Isle, where much of the population is outraged at how a handful of people could overshadow their own anti-racist beliefs, must face the reality that racism is a deeply rooted reality. It permeates the fabric of our country and, while rock-throwing may be a shocking wake-up call to some, it’s the hidden aspects of racism that are the hardest to overcome.

Martha Noyola-Corralejo has learned that lesson well. Of Mexican descent, NoyolaCorralejo first experienced blatant prejudice growing up in Mississippi when a white woman accused the then seven-year-old of having lice because she was Mexican. NoyolaCorralejo watched as her parents endured humiliation by white field-bosses as they eked out a living to give their daughter a better life. When she was thirteen, her family moved to California where unions gave her parents more protection and helped Martha and her family finally win respect for their hard work.

A college graduate, Noyola-Corralejo moved to St. Cloud as an adult and was shocked to find out that the respect she had won simply disappeared. While shopping in a major discount store, Noyola-Corralejo

walked up to an employee to ask where to find an item. The woman glanced at her and ignored her.

“I was very nice and asked her again very politely,” says Noyola-Corralejo. “The woman snapped at me and said, ‘I’m busy!’” NoyolaCorralejo asked to speak to a supervisor, who made the employee apologize.

“It’s a tough thing to speak out,” says Noyola-Corralejo. “It makes you very vulnerable. But I’m very sensitive to this issue nowadays, so I’m aggressive.”

“One of the most glaring problems Minnesotans have is their tendency to minimize cultural differences,” says Juan Moreno, who travels Minnesota as the diversity and inclusion specialist for the University of Minnesota Extension department. He trains university staff on diversity and anti-racism issues.

“Minnesotans like to think that we are all alike, that we’re all pretty much the same,” says Moreno. “And while fundamentally we are all alike as humans, we are also fundamentally and profoundly different.”

It’s getting white Minnesotans to recognize this and to realize that what they often take for granted as how things work in Minnesota, is not what Minnesotans of color experience.

“First of all, it’s important to realize that all people have prejudices. Whites and people

‘‘You might liken RACISM to the default settings in software. It’s what we keep going back to unless we make a conscious effort to change the settings in ourselves and our society.

—James Addington, Minnesota Collaborative Anti-Racism Initiative

of color,” says Addington. “And because we have so many different social identities, most people will experience some form of discrimination in their lifetime. However, racism has always trumped other forms of oppression. And it will not change unless individuals intentionally embark on a learning journey.

“When individuals become aware of racism, that’s when we can start moving toward changing it within our systems and institutions,” he continues.

MCARI works by going on-site to an organization and establishing a leadership team made up of representatives from every aspect of the organization. This team then undergoes two years of training, during which the team completes in-depth research on policies and procedures to identify racist tendencies. The leadership team then makes recommendations for change and continues the process long-term.

“There is no quick fix. Institutions have to create and work out strategies from the inside. It comes down to embedding new core values in an organization and only people on the inside can do that,” says Addington.

According to Addington, history indicates that it takes ten years to institutionalize change.

Debra Leigh, professor at St. Cloud State University and leader of Community AntiRacism Education Initiative, says CARE workshops provide a context to talk about racism on the campus and address institutional practices and policies.

“It is the intent of the team to have a powerful, effective, and lasting impact on the campus,” says Leigh. “Our mission is to build a lasting anti-racist community. Employees, students, and community members have honest discussions about their

perceptions of race. Participants are then given some specific tools that can be used in their everyday decision-making to help transform our institution’s identity.”

“Even with all the amazing inputs from the Minnesota State Colleges and Universities System and SCSU administration, organizing change is not instantaneous,” she adds. “In three years, we’ve come a long way but we’re still scratching the surface.”

The costs of racism are high. It results in disparities found in education gaps, income levels, incarceration rates, inadequate healthcare, and in various forms across the board. But while it’s easy to look at statistics on disparities, Addington cautions that doing so without having a larger discussion on racism results in a tendency to start asking, “What’s wrong with these people?” instead of looking at the institutions that are embedded with racist principles.

For David Sam, who was driving the truck struck by the rock, the pain caused by racist individuals in Isle is just another reminder of how far central Minnesota has to go.

Sam is not inclined to return to Isle in 2007. Weyaus will be there. He is a warrior and a veteran, he says. Not attending the Isle parade because of cowardly racist acts is not really an option.

“Racism will be part of our area for a long time,” says Weyaus.

It will be, but how long depends on each of us. React at IQMAG.ORG

“Not me,” you say. After all, your bluecollar parents treaded barely above the poverty line. You paid your way through college and worked hard to get where you are today. But sociologists assert that our “invisible systems” offer advantages that most white people don’t even know they have. Still not convinced? Imagine you’re any color but white. Could you say the following?

• I don’t have to protect my children from people who might not like them because of our race.

• At meetings or in public, I seldom feel isolated, out-of-place, outnumbered, unheard or feared.

• I have no difficulty finding neighborhoods where people approve of our household.

• I can take a job or enroll in a college without my peers assuming I got in because of my race.

• Ican easily buy books, greeting cards, dolls, and toys featuring people of my race.

• I am never called “a credit to my race” or asked to speak for all of the people of my racial group.

eronica Botello’s father desperately wanted to bring his family to the United States. For ten years, he worked at a turkey-processing plant in Pelican Rapids while his wife raised their children in Mexico.

“The green cards aren’t given that easily, so we had to wait until 1995,” recalls Veronica, now twenty-eight. She was fifteen and had just completed the ninth grade in Mexico. “It was hard, leaving all my friends and coming here.” But she respected her parents’ wishes, learned English, and excelled in school.

Central Minnesota’s progressive, workerstarved industries are a magnetizing force behind the region’s demographic transformation. Immigrants and refugees have filled critical workforce needs, especially in the manufacturing and meat-processing industries.

“We had to analyze our hiring process,” says Loretta Trulson, human resources director of Stearns, Inc., a national manufacturer of personal floatation devices with facilities in Sauk Rapids and Grey Eagle. “What did we need to do differently in order to attract a diverse workforce?”

Language is the primary stumbling block for both immigrants and their employers. To meet their workforce needs, employers must identify which jobs can accommodate nonEnglish-speaking workers, and then tailor their hiring and training accordingly.

Stearns, Inc. continues to host onsite job fairs, complete with interview interpreters to accommodate job candidates from Vietnam, China, Laos, Bosnia, and Somalia. The company also verifies legal work status for every new hire.

“Historically, immigrants came into agriculture, manufacturing, food-processing, or cleaning-service kinds of jobs,” says Kathy Zavala, executive director of the StearnsBenton Employment and Training Council in

St. Cloud. “What’s changing today are the skill demands. We can’t wait two or three generations for people to master English and get formal training.”

Area employers, such as Stearns, Inc., work with the council to assess issues faced by businesses and their immigrant workers. She says that some workers have declined health insurance coverage because they do not understand the programs. Others are not familiar with vacation time or retirement plans. Trulson recommends getting translations and employee orientation directly from benefit-plan vendors.

Trulson, who has been with Stearns, Inc. for seventeen years, says the company is richer for its diverse workforce. Immigrant workers, “bring different ways of doing things, different ways of looking at things,” she says.

Mike Helgeson is chief executive officer of Gold’n Plump Poultry, a family owned, 1,500-person-company founded by his Scandinavian grandfather in 1926. Today, it employs workers from such countries as Mexico, Somalia, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, and Sudan.

“Every day, we transform a diversity of ideas, perspectives, experiences, cultures, and ethnicities into a cohesive team,” says Helgeson. “We apply the same creativity and leadership to our employee programs.”

The company offers onsite English classes and reimbursement for continuing education. “Communication is crucial,” says Peggy Brown, Gold’n Plump human resources director. We also work to broaden cultural understanding because cultural differences can create obstacles.” Thus, company potluck dinners become opportunities to experience ethnic foods and activities.

Veronica Botello is a shining example of immigrant triumph over cultural and economic barriers. She now works as a bilin-

gual receptionist at the CentraCare Clinic in St. Cloud.

“I have worked hard to be where I am,” says Botello, “struggling with the language— trying every day to do better. I feel like everything is good, as long as we’re all together.” React at IQMAG.ORG

• Arrange a “box-lunch forum” on topics of diverse cultural and social interest.

• Examine diversity at all levels of the workplace. Are there barriers that make it harder for people of color to succeed?

• Fight “just like me” bias, the tendency to favor those who are similar to oneself.

• Avoid singling out employees of a particular race or ethnicity to “handle” diversity issues on behalf of everyone else.

• Start a mentoring program that pairs veteran employees with newcomers.

• Establish an internal procedure for employees to report incidents of harassment or discrimination. Publicize it.

Source: Southern Poverty Law Center, www.tolerance.org

IIlike math a lot,” says Hamdi Abdi, her big brown eyes dancing, “and reading.” It was July 2005 when Hamdi, her mother, three sisters, and two brothers arrived in the United States. After civil war violence drove them from Somalia, Hamdi and her family survived in a small refugee town in Kakuma, Kenya for fifteen years. After first arriving in New Orleans, the family moved to Minnesota to join friends and an established Somali community.

According to Gary Loch, the St. Cloud School District’s diversity coordinator, the Somali student population has been growing steadily for the past eight years and makes up the largest group of diverse students at St. Cloud Technical High School.

After arriving in St. Cloud, Hamdi was placed in tenth grade. She participated in the English Language Learners (ELL) program for a year and a half, is now fully integrated into the classroom, and will complete four years of high school in three years. She even tutors other students in math and science.

But Hamdi is the exception. In 2006, the Minnesota Minority Education Partnership issued its State of Students of Color Report that documented the upsurges in school diversity and drew attention to stark differences in student achievement levels. From 2000 to 2005, students of color scored significantly lower in the Third-Grade Minnesota Comprehensive Assessment (math and reading) as well as the Minnesota Basic Skills Test, a high-school exit exam. Graduation rates are also markedly lower.

According to English as a Second Language (ESL) teacher, Mary Walker, unlike Hamdi, many of St. Cloud’s immigrant and refugee children know very little English. “Some have never been in a formal school,” says Walker.

With thirty spoken languages and nearly one thousand ELL students, the school district has taken purposeful strides to educate teachers and students on issues of language, racism, and building community. From mixing student seating in the cafeteria to a fourth-grade buddy system, the district is finding ways to encourage communication between cultures.

“We knew that in order to help the ELL students with their education, we needed help from the community to meet the housing, clothing, food, and medical needs,” says St. Cloud Superintendent Bruce Watkins.

Watkins and Loch convened a series of community meetings. The goal was to understand and connect resources so that teachers could refer students and their families to the help they needed.

“Kids can’t learn if they’re hungry or if they don’t know where they’re going to sleep at night,” says Initiative Foundation president Kathy Gaalswyk, who attended the meetings. “St. Cloud is providing an excellent example of how entire communities can rally together and connect the dots for the sake of our children.”

Isle High School has also experienced a steady increase of diversity, especially American Indian students, as well as the resulting racial

tensions. “The whole area is aware that there is not a positive attitude about race relations,” says Jeff Searles, Isle High School’s dean of students. “The philosophy is, maybe if we can get our children to play nice together when they are young, they will play nice together when they are older.”

Several recreation centers and outside funding have helped to promote cultural dialogue and understanding of mutual challenges and feelings.

According to education leaders, the greatest challenge that remains is securing funds to serve growing populations. While the federal No Child Left Behind Act promises funding, both school districts report that there are no new funds, just a reallocation from their other programs. In the meantime, they are applying for grants and leaning on communities for help.

React at IQMAG.ORG

IIt’s a common joke. You get a prescription from your doctor and it looks to be written in a different language. Apparently some combination of those loops, scribbles, and dots is supposed to be an English word or phrase. You study it for a while, assume it’s correct, and pass it on to the pharmacist.

“Now imagine trying to navigate in a new land, not knowing the language, being handed papers not in your language,” says Paul Knutson, Mission Development Specialist for CentraCare Health System in St. Cloud. “It definitely adds to a lot of the anxiety.”

As more and more immigrants and refugees settle in central Minnesota, area healthcare providers are faced with ever-changing challenges. From healthcare coverage and access, to cultural and linguistic barriers, the course can be a daunting one for both parties.

The application to apply for public assistance in Minnesota is long and complex—the instructions alone make up eleven pages of the thirty-six page document. And whether private or public—just one large hospitalization bill clearly demonstrates the need to have some sort of coverage.

“If they don’t have individual or employer coverage,” says Knutson, “we ask everyone to sign up for state care.”

Differing languages and cultural beliefs can also be barriers.

“There are basically three languages,” says Knutson. “The provider’s language, which is usually English, the patient’s native language, and the medical language. Some concepts are not always transferable so we end up putting a lot of faith and trust in our interpreters.”