Unravel the epic story of birds and discover the secrets of their success in our new exhibition

Did you know that great tits sometimes feed on bat brains, that zebra finches sing to their unborn young, or that vampire finches feed on blood? All these fascinating stories and more can be found in our latest blockbuster exhibition, Birds: Brilliant & Bizarre

Produced in affiliation with the RSPB, it draws on the Museum’s cutting-edge research into birds’ physiology and behaviour, and showcases rare specimens from our unrivalled bird collection, including an egg from the now-extinct great auk and a spectacular Philippine eagle. The exhibition also explores birds’ extraordinary survival story – from outliving the dinosaurs to diversifying into an incredible 11,000 species alive today and the challenges they face in our rapidly changing world.

As well as captivating specimens and hands-on exhibits, we’ve commissioned three spectacular immersive experiences. Lift your senses with the joy of birdsong from around the world, witness the mesmerising motion of a starling murmuration, and – through a reimagined dawn chorus – explore the positive futures we can create for our feathered friends.

Find out more about Birds – Brilliant and bizarre on page 24 and then come and enjoy our exhibition, which is free for members and Patrons (with a 20 per cent discount for RSPB members).

‘Lift your senses with the joy of birdsong and witness the mesmerising motion of a starling murmuration’

We’re also celebrating our Nature Discovery Garden, supported by The Cadogan Charity – one of two outdoor galleries opening this summer – on page 38, and introducing our latest art installation, an immersive experience exploring the soundscapes of the River Thames on page 8. We look forward to welcoming you to the Museum this summer. We hope you’ll enjoy our new experiences and join us in celebrating the incredible biodiversity that surrounds us and reminding ourselves of the continued need to cherish the natural world.

AlexBurch, Director of Public Programmes

The Anning Rooms

Named in honour of legendary fossil hunter Mary Anning, this suite is exclusively for your enjoyment. Tuck into tasty lunches and snacks in the restaurant, take in the views from the lounge, or read a book in the study area.

Get free, unlimited entry to all of the Museum’s ticketed exhibitions, such as Birds: Brilliant and Bizarre, and guaranteed entry to our free exhibitions and installations, including The River. Exclusive events

Enjoy private exhibition views, workshops and a new series of talks, Dig Deeper, led by Museum scientists. As well as discounted tickets you will also receive priority booking and access to a special Members’ Bar on the night.

Shop and café discounts

Receive a 20 per cent discount in the Museum’s shops – which are stocked with a wide range of inspiring gifts, books and clothes – as well as a 10 per cent discount in our cafés and restaurants.

The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD

The Natural History Museum at Tring, Akeman Street, Tring, Hertfordshire HP23 6AP

Join the conversation

Instagram natural_history_museum

Facebook naturalhistorymuseum

Twitter/X NHM_London

TikTok @its_nhm

Youtube @NaturalHistoryMuseum

Email magazine@nhm.ac.uk

Never miss an issue of Natural History Museum magazine

Find back issues on the Hive, an exclusive digital hub especially for you. Starting from the February 2020 issue there are over 800 pages to enjoy, featuring the Museum’s research, exhibitions and events. nhm.ac.uk/the-hive

Emilie Pearson Emilie is a Collection Moves Assistant on the NHM Unlocked project, working to survey and prepare the collections moving to our new site.

Josh Davis Digital News Editor for the Museum’s website, Josh writes, edits and publishes stories about the research being done by our scientists.

Victoria Thomson Communications Manager for the Urban Nature Project, Victoria aims to inspire and empower people to make a difference for nature close to home.

24

Birds – Brilliant and bizarre

Discover why we’re getting all aflutter about our new exhibition, which reveals how birds have survived for millions of years thanks to their surprising abilities and extraordinary behaviours

32 Our ever-changing story

Find out how new dating techniques are transforming our understanding of how Homo sapiens and our relatives evolved, and updating timescales that reveal how we came into existence

38 Explore the Museum’s new gardens

Discover what awaits you in the Museum’s new gardens when they open this summer. Travel through geological time, explore our nature-friendly planting, and discover our living green laboratory

46 Here be monsters

Roaming the grounds at Crystal Palace Park are extinct beasts. Fabulously inaccurate in many ways, Karolyn Shindler explains why these magnificent sculptures offer a snapshot of the cutting-edge science of their time

52 Standing up for nature

Naturalist and conservationist Lucy Hodson AKA Lucy Lapwing (below) tells us how nature aided her recovery from illness and why she wants everyone to tell their stories about local wildlife

56 The eternal quest for answers

From unlocking the past to decoding life on Earth, we explore why the Museum’s work is focused on answering some of the most critical questions facing humanity and the planet

12

New at the Museum

Learn about how we’re cleaning the Museum’s terracotta facade, glimpse the future in our Images of Nature gallery, and more

16 What’s on

Find out about all the Members and Patrons events, plus a 60-second chat with Pauline Robert

18

Science in focus: New pterosaur discovered Middle Jurassic pterosaurs were more diverse than previously thought

20 Inside story: Alex Waters

Our Retail Assistant Buyer develops unique sustainable products and gifts for the Museum’s shops

22

Exceptional specimens: Urial sheep skull Sheep might be the first known animal to have genuinely gay individuals

6 Viewfinder

See. Learn. Be amazed by three extraordinary images that inspired everyone at the Museum

62 Winged beauties

52

Take a closer look at the butterflies and day-flying moths that brighten our outdoor spaces

66 Book reviews

Our experts consider the latest and greatest natural history titles that are available to buy now

69 In our shop

Make the most of your 20 per cent discount with a range of beautiful items from our shops

70 From the Archive

How the Children’s Centre shaped future visits to museums for children everywhere

Senior Editor Helen Sturge

Editorial team Kevin Coughlan, Ollie Crimmen, Josh Davis, Adriana De Palma, Alessandro Giusti, Dr Peter Olson, Jennifer Pullar, Emilie Pearson, Dr Helen Robertson, Professor Sara Russell, Dr Tom White and Colin Ziegler

For Our Media

Editor Sophie Stafford

Art Editor Robin Coomber

Production Editor Rachael Stiles

Account Manager Debbie Blackman

Editorial Director Dan Linstead

Contributors Lu Allington-Jones, James Ashworth, Professor Paul Barrett, Jennifer Benson, Dr Alex Bond, Georgie Britton, Alex Burch, Paolo Cocco, Dr Joanne Cooper, Noelia Galan, Andrea Hart, Lucy Hodson, Elle Kaye, Paul Kenrick, Dr Liz Martin-Silverstone, Giulia Masci, Tom McCarter, Lizzie Reay, Pauline Robert, Kathryn Rooke, Karolyn Shindler, Professor Chris Stringer, Evie Smith, Natalie Tacq, Victoria Thomson, Marita Tsagkaraki, Helen Wallis, Alex Waters, Chrissy Williams

With thanks to Professor Ian Barnes, Matt Clark, Ella Davies, Kate Franklin, Dr Adrian Glover, Lucie Goodayle, Gerry Hey, Susan Holmes, Dr Ellinor Michel, Joe Millard, Joseph Morrin, Dr Ken Norris, Dr Paola Ricciardi, Vince Smith, Christine Strullu-Derrien, Kate Whittington

The views expressed in Natural History Museum magazine do not necessarily reflect those held by the Natural History Museum. Produced in association with Our Media. ourmedia.co.uk

All photographs and copy © 2024 The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London unless otherwise stated. If you would like copies of any Museum images please contact the Museum Picture Library on 020 7942 5401.

2044-7582

History Museum magazine is mailed in packaging using potato starch along with other biological polymers. It

‘The mystery surrounding snow leopards always fascinated me,’ says photographer Sascha Fonseca. ‘They are some of the most difficult large cats to photograph in the wild.’ Undeterred, Sascha followed this elusive feline into its icy mountain home on his quest for the perfect portrait.

All of the photographers in Remembering Leopards have demonstrated equal determination, commitment and fortitude in creating the breathtaking images in its pages. Their photos

reveal the many faces and landscapes of these adaptable species – the book features all eight subspecies as well as snow and clouded leopards – and transport the reader around the world from the cloud forests of Malaysia to the dry plains of Africa.

The Remembering Wildlife book series raises awareness and funds for conservation projects around the world. Every page reminds us of what’s at stake – but it’s not too late to save them.

Find out more at rememberingwildlife.com

Dive deep into the heart of the River Thames in the middle of the Museum. Our upcoming audio installation, by sound artist Jana Winderen in collaboration with spatial sound specialist Tony Myatt, immerses audiences in the rich tapestry of sounds that echo through this iconic waterway, from its source to its sprawling estuary amid the din of urban activity.

Noise pollution threatens all freshwater ecosystems and affects aquatic wildlife. Jana’s work captures the river’s essence using hydrophones,

providing a unique perspective from a fish’s point of view. She weaves a sonic journey that explores the river’s history and inhabitants – from the wildlife living under the surface to the people who live, work and play on its waterfront.

In a dimly lit gallery, this three-dimensional sound experience reveals the diverse soundscape of an underwater world that’s teeming with life, as well as the noise pollution that threatens it.

The River opens at the Museum this summer in the Jerwood gallery.

Pufferfish have an iconic defence mechanism. They inflate themselves by sucking water into their incredibly elastic stomachs. Thanks to specially modified gill muscles and a lack of ribs, they can swell to an almost spherical shape, three or four times their usual size. However, inflation comes at a cost. Scientists have found that it takes a lot of energy for the fish to inflate, that swimming while puffed up is more difficult, and that staying inflated

uses five times more oxygen than when resting. So while it’s a useful strategy to avoid being eaten – as demonstrated here by a guineafowl pufferfish in Hawaii – it’s not in their best interests to stay inflated for long. Most quickly return to normal size once the danger has passed.

Find out more about these famous inflatable fish at nhm.ac.uk/discover/ pufferfish-underwater-balloon-of-death.

In February, we began work to clean and conserve the beautiful facades of the historic Waterhouse building.

The Waterhouse building is the historic heart of the Museum, designed by Alfred Waterhouse and built at the end of the nineteenth century to house the British Museum’s growing natural history collections. Its first director, Professor Richard Owen, called it a ‘cathedral to nature’.

Waterhouse’s architecture mixed Gothic Revival and twelfth-century Romanesque styles.

Above and above right

The Waterhouse building as it looks today, with terracotta animals, both real and mythical.

It was enriched, both internally and externally, with sculptural ornaments inspired by the natural world that added aesthetic variety and interest and helped educate visitors.

Waterhouse’s designs were based on the most up-to-date anatomical knowledge of species available at the time. To achieve his design, Waterhouse used terracotta in an innovative way. Previously, the use of terracotta had been limited to decorative elements, but the Natural History Museum is the first building where terracotta was used as a construction material for the entire main facade and the interiors. The reasons for his choice were practical – producing sculpted or moulded elements with terracotta was cheaper and quicker than using stone, and terracotta was less affected by the polluted air of Victorian London.

More than 140 years later, the building and its decorations still stand, a testament to the validity of Waterhouse’s choices, but they’re in need of

‘It’s the first time the facade will be fully conserved, including all the terracotta and the cast-iron windows’

some TLC. At over 200 metres long and 60 metres high at its pinnacles, this is an ambitious project. It’s the first time the facade will be fully conserved – including all the terracotta, the cast-iron windows and the conduits that channel rainwater from the roof.

Previously, only ad hoc repairs have taken place on various different elements of the building, including a full clean, almost 50 years ago, carried out using an acid solution that left permanent streaks that are still visible. Our approach today will be much gentler, using steam to remove dirt and pollution.

The project is expected to take 14 months, until late March 2025, and will use an innovative, free-standing, rolling scaffolding that is not fixed onto the structure and is concealed by a life-size print of the building. It forms part of a programme of works to ensure the Museum is looking at its best for our upcoming 150th anniversary in 2031.

10

This year the Museum is celebrating 10 years of digitisation. With nearly six million specimens digitised, including over two million insects and a million plants, it will help scientists around the world understand how biodiversity is changing.

16

6

It took conservators six weeks to spruce up the four whale skeletons hanging from the ceiling of the Museum’s whale hall. The last time the skeletons were cleaned was 16 years ago, in 2008.

100

The Perseid meteor shower is expected to feature 100 meteors per hour at its peak. One of the best celestial events of the year to watch, it takes place from 17 July to 24 August as Earth passes through the trail left by the comet Swift-Tuttle.

The 60-year history of the Wildlife Photographer of the Year Competition has inspired a new display in the Museum’s Images of Nature gallery. From stunning cyanotype prints (above) to a 3D-printed cardboard head of Dippy – the Museum’s iconic dinosaur – the new display will trace the history and use of photography in natural history and explore the development of modern-day imaging techniques used in science and storytelling.

The new display also explores the close ties between science, photography and art, showcasing how the Wildlife Photographer of the Year Competition reveals the beauty and vulnerability of the natural world while advancing scientific knowledge.

See how artists and scientists view the natural world through more than 100 images from the Museum’s collection in the Images of Nature gallery (Blue Zone) from 12 July.

Winner of ‘Hero Toys for 2024’ London

The Museum has teamed up with Galt Toys to develop a new range of inspiring activity kits. The ‘Let’s Learn’ range combines richly detailed illustrations with scientific accuracy to engage younger children in science, technology, engineering, arts and mathematics. Each sustainable kit includes six projects designed to inspire future scientists. The first two kits –Dinosaurs and Tiny Creatures – are available now. Let’s Learn Animals will follow later this year.

A new touring exhibition is exploring how and why collections of Sir Hans Sloane were created, and offer new perspectives on entangled collecting histories and their legacies.

Sir Hans Sloane was one of the most influential men of early eighteenth-century London. He amassed one of the greatest private collections of plants, animals, antiquities, coins and other curiosities. These items became the founding core of the British Museum and later the Natural History Museum, and the British Library. But Sloane did not work alone in the assembly of these collections – more than 300 named contributors were recorded in the Herbarium and there were many others that were not named. Enslaved and Indigenous

Above and right Items in the exhibition from the Museum’s collection of Sloane’s Vegetable Substances, including the pod, seeds and fine, silky hairs of the Jamaican climbing plant, and a pressed cake of tea leaves, known as a Tuo-cha.

People contributed valuable knowledge, but were rarely recorded or acknowledged.

Akosua Paries-Osei, a researcher at Royal Holloway, is working on specimens in the Sloane Herbarium. ‘I use botanicals to bring to life the hidden world of enslaved women’s botanical knowledge,’ she says. For example, gossypol is a compound found in cotton that acts as a contraceptive and, in high-enough doses, as an abortive agent. With cotton a staple of the slave trade, the slaves who tended these plants used their indigenous knowledge of cotton to manage and control their fertility.

‘Enslaved women were valued for their ability to produce and reproduce,’ says Akosua. ‘By restricting their reproductive capacities, enslaved women directly resisted slavery as they impeded the ability of slave owners to profit from their reproductive capacities and increase their human stock.’

As slave owners learned about the anti-fertility properties of cotton, the act of reproductive resistance risked severe violence, with the plant black haw utilised to counter the abortive effects of cotton. But this did not stop the enslaved women. While slavers came to recognise the properties of cotton, other plants such as okra, which also contained gossypol, continued to be used.

Histories of science and natural history are intimately entwined within histories of enslavement and resistance. But enslaved women were not passive recipients of enslavement. They were active agents who used their skills and knowledge not only for subsistence, but also to disrupt and dismantle slavery.

The exhibition will explore these narratives with museums across the UK and is on tour until 7 September. Find out more at britishmuseum. org/ exhibitions/ curious-andinterested

Big-headed ants are changing the food chains of the savannah. These little but fierce insects have led to the loss of cover for lions from which to ambush zebra, forcing them to target buffalo instead.

Fossils found in Peru of a new species of early whale might be the heaviest animal that’s ever lived. Possibly weighing as much as 340 tonnes, its unusual bones suggest it was no ordinary cetacean.

New research reveals water levels in as many as a third of the world’s aquifers are declining faster now than they did 40 years ago, as we take water out of the ground faster than it can be replaced.

Have you ever wondered where a snake’s head ends, and its tail begins? What the deep-sea floor looks and feels like? Or how we know the age of meteorites?

From discovering new species of dinosaur and revealing the origins of the Solar System to tracking diseases and countering the biodiversity crisis, the more than 350 scientists working at the Natural History Museum are at the forefront of contemporary natural science.

Dive deeper into the natural world with our new online learning platform, Naturally Curious, and find answers to these questions.

In late 2023, The Royal Mint’s Tales of the Earth series returned for its third season. An ongoing collaboration with the Natural History Museum, this series of collectable coins celebrates the groundbreaking discovery of some iconic specimens that lay buried in the earth for millions of years.

These pre-recorded courses on topics ranging from the biology of snakes to the future of the green economy are led by our world-leading experts and supported with detailed course notes.

New courses are released monthly with exciting topics coming soon, sign up to be the first in the know. Listen to the introduction of any course for free or dive deeper into a topic of your interest.

Use the discount code MEMBERS10, to get 10 pent cent off any of the courses and indulge your natural curiosity today at naturallycurious.nhm.ac.uk.

This latest collection pays homage to some of the bestloved dinos from the Museum, Tyrannosaurus, Stegosaurus and Diplodocus. The series was designed by palaeoartist Robert Nicholls, with the guidance of Museum expert Professor Paul Barrett.

To be in with a chance of winning one of three sets of the coins, simply tell us where The Royal Mint is currently located. To enter, email your name, address, phone number and answer to magazine@nhm.ac.uk and put ‘Coins’ in the subject line. Or post your answer to ‘Membership’ at the address on page 3.

Birds: Brilliant & Bizarre

Until 5 January 2025, normal Museum opening times

From £16.50 Adults / £9.95 Kids / £13.20 Concessions / £29–£50.25 Families

Members and Patrons go free Unravel the epic story of birds, discover the secrets to their success and learn some of their surprising and often shocking tactics for survival. nhm.ac.uk/birds-brilliantbizarre

The River

Coming soon, normal Museum opening times Free

This upcoming audio installation immerses audiences in the tapestry of sounds that echo through the underwater world of the iconic River Thames. nhm.ac.uk/the-river

activities

Dino Snores for Kids

Every month, 18.45–10.00

£80 non-members / £72 members

Ever wonder what happens in the Museum when everyone’s gone home?

During this action-packed sleepover, you’ll take part in fun, educational activities, discover our T. rex hidden in the shadows of the Dinosaurs gallery, follow a torch-lit trail, create your own dinosaur T-shirt and experience a live science show with a Museum expert. In the morning there will be breakfast and a live animal show. For ages 7–11. nhm.ac.uk/dino-snores

Dino Snores for Grown-ups

Various dates, 18.30–9.30

£220 non-members / £198 members

Pull an all-nighter at the Museum and experience an unforgettable evening of comedy, food, science and cinema. You’ll enjoy live shows, a delicious threecourse dinner, live music, an eye mask decorating activity and a monster movie marathon, followed by a hot breakfast the next morning. For ages 18 and over. nhm.ac.uk/dsgu

Find out what’s on at the Museum, and plan your next great day out, by visiting nhm.ac.uk/whats-on

Museum Highlights Tour

Various dates and times

£15 non-members / £12 members

From the awe-inspiring blue whale skeleton suspended from our ceiling to the largest blue topaz gemstone of its kind, the specimens we care for are full of wonder. Join one of our knowledgeable guides to explore the best highlights. nhm.ac.uk/events/museumhighlights-tour

Behind the Scenes Tour: Spirit Collection

Various dates and times £25 non-members / £20 members

Go behind the scenes in the Museum’s Darwin Centre for a look at our fascinating zoology collection preserved in spirit. Explore some of the numerous treasures among the 22 million specimens. nhm.ac.uk/events/behindthe-scenes-tour-the-spiritcollection

Women in Science Tour

Various dates and times Free

Hear the gripping histories of several women scientists from history including some who’ve worked at the Museum, and learn about the Museum’s displays and our cutting-edge science. nhm.ac.uk/visit/whats-on (search free events).

Dig Deeper: Clever Crows and Remarkable Ravens 2 July 18.30–20.00

Join Dr Joanne Cooper, Senior Curator of Birds, and Professor Nicky Clayton from the University of Cambridge as they discuss corvids and their remarkable intelligence.

Anning Room Session:

Charles Darwin

13 July, 11.00, 12.15, 14.00, 15.15

Bring the kids along to our Anning Rooms workshop to learn about Charles Darwin’s adventures on board HMS Beagle and the incredible discoveries he made along the way about the creatures we share the planet with.

Dig Deeper: Deep Sea 25 September, 18.30–20.00 Ever wondered what mysteries lie at the bottom of the sea? Join Dr Adrian Glover, deep-sea ocean scientist, as he takes us to the Pacific Ocean’s floor for a glimpse into his latest expedition, which chartered new territory and aimed to protect the biodiversity of the seabed.

Anning Room Session: Mary Anning 28 September, 11.00, 12.15, 14.00, 15.15

Bring the kids along to our Anning Room workshop to learn all about Mary Anning’s fossil hunting adventures.

Member Preview Evening: Wildlife Photographer of the Year 60 11 October, 18.30–20.00

Please note: Some dates and times are subject to change. For further information on members events, visit nhm.ac.uk/membership

An exclusive digital hub especially for our supporters, the Hive is filled with exciting videos, articles and activities to help you stay connected with nature and the Museum. Here you’ll also find an exclusive virtual events programme, bringing you closer to our world-leading scientists through a series of lectures and workshops. Discover it all at nhm.ac.uk/the-hive

Private View of Birds:

Brilliant and Bizarre

Open to All Patrons

2 July, 20.00–21.30

Join us straight after the Dig Deeper Talk to experience the newly opened exhibition and take a tour with our experts who helped curate it.

Urban Nature Project: Private Tour and Coffee Morning

Open to All Patrons

18 July, 8.30–10.00

Be one of the first supporters to explore the gardens in full bloom with a private tour, followed by coffee and cake in our new Garden Café.

Patrons Night at the Museum

Open to All Patrons

2 September, 19.00–22.00

Ever wondered what goes on behind the scenes to keep the Museum running?

Don’t miss Experts uncover the marvels of science on Earth and beyond at Dig Deeper: Scientific Surprises and Accidental Discoveries. Catch up on the Hive.

Back for a second year, join us as night falls to see just what it takes.

Wildlife Photographer of the Year 60 Awards Ceremony

Open to Platinum Patrons

8 October, 19.00–01.00

Experience dinner in Hintze Hall where the winners of the Wildlife Photographer of the Year 60 competition will be announced.

Wildlife Photographer of the Year 60 Launch

Open to Platinum and Gold Patrons

9 October, 19.00–21.30

Enjoy a glamorous drinks reception in Hintze Hall and explore the exhibition before it opens to the public.

Please note: Some dates and times are subject to change. If you have any questions about upcoming events, please contact patrons@nhm.ac.uk.

As a Patron, you’ll enjoy all member benefits, as well as discounted access to visitor and members events plus your specially curated programme.

What do you do?

I’m the Head of the Wildlife Photographer of the Year (WPY) programme. I drive the strategy and reach of the annual competition, exhibition and related global activities.

Tell us about 60 years of WPY

We are celebrating 60 years of excellence in wildlife photography and environmental storytelling. Photography has advanced dramatically over this time, from film to digital, black-andwhite to colour and new technologies such as drones and camera traps.

WPY and our global community has grown exponentially too. The awarded images reach millions of people around the world every year, inspiring awe and sparking action to protect the natural world. This year, a new Impact Award will encourage and recognise hopeful stories and conservation successes.

How has the number of entries changed?

In its first year it had 361 entries. Now we receive nearly 60,000 from more than 110 countries and territories. Our ambition is to keep growing and encourage entries from

regions the competition has historically received fewer entries from. This year we increased the number of countries benefiting from the entry fee waiver across Africa, southeast Asia and Central and South America.

How difficult is judging?

The jury has a huge task of selecting only 100 images from so many stunning photographs. The process takes weeks and culminates with the vote for the category winners, then Grand Title winners. Thanks to a great diversity of nationalities, expertise and interests among the jury members, conversations remain fascinating and lively.

Favourite image?

I love a surprising one that pulls you in and draws your attention to different elements. So I find the young Grand Title winner from our fifty-ninth competition incredibly unique and powerful.

Don’t miss your chance to see the Wildlife Photographer of the Year 60 exhibition before it opens to the public at our preview evening. Details to the left.

The lowdown

Where Near Elgol, on the southwest coast of the Isle of Skye, in Scotland.

What A new species of pterosaur, Ceoptera evansae, has been discovered. This species would have been alive around 165 million years ago.

Why This discovery has shown that advanced Middle Jurassic pterosaurs were more diverse than previously realised.

When The fossil was discovered in 2006.

A paper describing the new species was published in early 2024.

A new species of Jurassic pterosaur has been described from the Isle of Skye. Still inside a rock, the remarkable specimen can only be studied by CT-scanning, reveals Collection Moves Assistant Emilie Pearson.

Awell-preserved fossil uncovered back in 2006 on the Isle of Skye in Scotland has been revealed as a new species of pterosaur, Ceoptera evansae.

The Museum’s Professor Paul Barrett was the leader of the expedition that resulted in the discovery, and is co-author of the paper describing the new species.

‘This new species is the first of its particular group to have been found in Scotland,

and is only the second flying reptile to be named from the country,’ Paul says. ‘It reveals that these animals were much more widespread than would otherwise be expected from their generally patchy fossil record, and it dates important events in pterosaur history to an earlier time.

‘Pterosaurs have a very poor fossil record in general, as their bones are quite fragile. As flying animals, they didn’t spend as much time on the ground near

Pterosaurs were flying reptiles and some of the earliest vertebrates known to have evolved powered flight.

the rivers and lakes where fossils usually form. Most of what we know about pterosaurs, especially in the Early and Middle Jurassic, comes from a handful of sites known as Lagerstätten, where fossil preservation is exceptional. Almost everything we know about pterosaur biology and evolution comes

‘CT scans revealed a bony shoulder flange that set this pterosaur apart from others’

from only eight or nine of these key areas around the world.’

The area where the fossil was found is a Site of Special Scientific Interest, so the expedition team could only collect specimens from rocks that had fallen naturally onto the beach. It was while crawling over these fallen boulders that the team noticed some bones sticking out. They collected the top of the boulder so that it could be brought back to the Natural History Museum and stabilised for further study.

This task fell to Senior Conservator Lu Allington-Jones, who went on to spend over a year working on the specimen, using a variety of techniques to expose the bones for study. In order to study bones too fragile to be removed from the rock matrix, CT scans were carried out. This process helped to reveal features such as a bony flange on the shoulder, which set the specimen apart from other pterosaurs.

Dr Liz Martin-Silverstone, a palaeobiologist from the University of Bristol and lead author on the new paper, says, ‘The fossil is from one of the most important time periods in pterosaur evolution, so it was already a significant find. To later discover that there were more bones embedded within the rock made it even better than initially thought. It brings us one step closer to understanding where and when the more advanced pterosaurs evolved.’ ●

Revealing the mystery in the matrix

Due to the fragility and fragmentary nature of the pterosaur bones, combined with the density and hardness of the rock matrix, a combination of techniques was used to get the specimen to a state where it could be studied further by the team.

Blast off the barnacles

When removed from the beach, the rocks were covered in a crust of barnacles. They were rinsed with methylated spirit to remove dust and other debris, and the surfaces were cleaned using abrasive air techniques to remove carbonate deposits. A protective plaster jacket was made for the lime mudstone block to protect the underside and then it was immersed in acetic acid, a weak organic acid often used in fossil preparation.

Scanned and modelled

To visualise the preserved remains, including those still encased in the rock, the specimen was CT-scanned at the Museum’s Computed Tomography Facility. Later scans, which enabled scientists to describe the specimen, were carried out at the University of Bristol. The different elements of the specimen were then grouped into vertebrae, forelimb, hind limb, metatarsal/ metacarpal, unknown fragments, and identified bone groups.

Rinse and repeat

After being immersed in acid, the rocks were rinsed in running water for six days to remove any excess acid and calcium salts. The softened layer was then removed with a brush and lowpressure water jet. The blocks were dried in an oven for five hours at 50°C to limit crystal growth. When dry, they were photographed and exposed bones were treated with acid-resistant resin to protect them. This whole process was repeated 29 times over a period of 12 months.

4

Next, we created a phylogenetic tree for the specimen, a branching diagram that shows the evolutionary relationships between different species with a common ancestor. In this study, we drew on information about 69 species (including 67 pterosaurs and two nonpterosaurs – the reptile Euparkeria and a reptile-hipped dinosaur Herrerasaurus) and used 136 skeletal characters to infer the relationship between our specimen and other known species. 1 3

Exploring the family tree

As one of the Museum’s Assistant Buyers, Alex Waters is responsible for keeping our shops stocked with interesting, sustainable and unique gifts. He reveals what it takes to create and curate a world-class retail range for a world-class Museum.

My life in a nutshell

I’ve always worked in retail. Before the Museum, I was in the homeware- and accessories-buying team at a high-street department store.

Like a lot of people at the Museum, I’m a big fan of spending time in nature.

I love working at the Museum at dusk. Being the only one standing under Hope the whale, experiencing my very own Night at the Museum, is incredible.

What do you do at the Museum?

As an Assistant Buyer in the Retail Team, I typically select and develop products for our Museum shops across our core and seasonal ranges. This includes taking inspiration from our exhibitions, the building and big calendar moments such as Christmas, Eid, Easter and so on.

From books and merchandise to replicas and prints, everybody has their favourite area to work in – mine are the adult gifting and Christmas ranges. Most of our products are developed entirely from scratch and can be bought nowhere else! A huge part of my job is talking to Museum scientists to ensure our products are scientifically accurate. I started the job with no real knowledge of dinosaurs, but after three years of working with the palaeontologists, I’ve learnt a lot.

What’s your favourite part of your work?

I love that when we’re developing a new range, we can search for suppliers who share our values in sustainability and responsibility – and, in turn, make a big difference to their business. To create a recent range inspired by Hope the whale, we partnered with a small company in India that supports amazing local artisans to make fairtrade jewellery.

Not only do we champion independent creators, but our customers can enjoy knowing that the profits from their ethical purchases support the Museum’s work to find solutions from nature for nature. I’m proud that the Museum is leading the way in more sustainable and responsible gifting.

How do you keep up with trends in retail?

Most of the time we have our finger on the pulse, watching social media to get ahead of the next big thing. But trends sometimes take us by surprise! Our dinosaur hood is hugely popular at the moment, so there are lots of human T. rexes roaming around the Museum. When stocking our shops, we’re often guided by upcoming exhibitions and other things going on at the Museum. By the time you read this, you might have spotted some new products inspired by the addition to our gardens.

How do you work with the Museum’s scientists?

There is a whole range of replicas in our shops that are based on real specimens. First, we think about what is most likely to inspire visitors to the Museum, then we work with scientists to dig around in our vast collections and make a shortlist of specimens – there are 80 million options, so it’s not easy. Our amazing Imaging and Analysis Team then make meticulous 3D scans and print out the models, which are sent off to our suppliers who create and paint the replicas for us. A short while later, the product appears in the shop.

What’s the best thing you work on?

I enjoy working on the print range. Few people know the Museum has more art in our Archives than most art galleries. Being able to explore the Libraries and Archives and look through all the old adverts for the Museum, ticket stubs and vintage designs is always a source of inspiration for our next range. But my most favourite is definitely the Christmas jumper. It’s not often you get to develop a product that’s so highly anticipated by our customers and part of an annual tradition. Plus, it’s another great example of the Museum supporting a UK-based, sustainable business.

What inspires you most about the Museum?

There’s a lot of inspiration in the Museum – the architecture alone is awe inspiring, there’s nowhere like it in London. Our history is interesting but so is the groundbreaking science happening behind the scenes. In the face of the planetary emergency, the Museum is more important today than ever before. ●

Could domestic sheep be the first known animal, apart from humans, that can be genuinely gay?

And if so, what about their wild cousins?

Scientific name

Urial, Ovis vignei Chosen Josh Davisby

Science Background Science writer

The urial is a species of wild sheep usually found grazing across the high, grassy plains of central Asia. Also known as the arkar, it typically lives in herds segregated by sex, with males forming bachelor groups. Within these groups there’s a social hierarchy in which older rams – which sport the bigger, more impressive curling horns – are usually at the top.

But, as with other species of wild sheep, the males in these groups frequently engage in homosexual behaviour, including courting, mounting and penetrating each other. Their behaviour raises an interesting question: can animals be gay?

When talking about the queerness of animals, scientists frequently refer to an animal displaying homosexual ‘behaviour’ or gay ‘activity’. This is because it’s impossible to ask an animal about their sexuality and difficult to follow a single individual for its entire life to observe its mating habits. This makes it exceedingly hard to know if an animal

‘When male sheep have the option to mate with a female in heat or another ram, eight per cent prefer other rams’

The lowdown

The domestic sheep is most likely descended from the mouflon, Ovis gmelini, which lives wild throughout central and southwest Asia. They were domesticated around 10,000 years ago.

is truly gay or not. If we were to use human definitions for animals, then most would not be classified as gay or lesbian but something more akin to bisexual. But even this becomes problematic when trying to assign sexuality to an individual animal. The domestic sheep, Ovis aries, however, offers us a unique opportunity.

Studies have found that when rams are presented with the option to mate with a ewe in heat or another ram, roughly eight per cent of all males show a consistent preference for other rams over time. This suggests that sheep may be the first known animal, apart from humans, in which genuinely homosexual individuals have been identified – though it’s important to note we can still never be 100 per cent certain.

Intriguingly, the gay behaviour of sheep is not limited to domesticated animals. Research has found that their wilder cousins are also incredibly queer, including the urial shown here.

Another wild species, the bighorn sheep Ovis canadensis, has even been described as living in ‘homosexual societies’. The rams in these herds regularly engage in homosexual courtships and sexual activity. The rams bow their heads, rub their horns against each other’s bodies, and taste their partner’s urine in a behaviour known as ‘flehmen’, which is usually thought to be a way for males to detect if a female is on heat. This is often done while the ram is fully erect, before it mounts and penetrates the younger animal.

Whether, like their domestic cousins, some of these rams are what we would consider gay, with a continual preference for other males, is still tricky to answer. Nonetheless, the parallels between the wild and domestic species are notable. ●

Today sheep are one of the most numerous vertebrates on the planet, with around 1.24 billion animals. The most sheep are in China, followed by India, Australia, Nigeria and Iran.

In domestic sheep the presence of horns is variable, but in wild animals both male and females have them. Horns are often bigger in males, which will use them to fight for dominance.

In some species of sheep, such as the urial and bighorn sheep, the males’ horns can get truly massive. One bighorn sheep had horns weighing 14kg – as heavy as all its other bones put together!

Sheep are intelligent animals with great memories. Research shows they can recognise up to 50 other sheep faces and remember them for two years. They can even recognise human faces!

The outer horn layer is made of keratin, the same protein as your fingernails. The keratin growth is not even on all sides. The outer edge of the horn grows faster, so it creates a curve as it grows.

A female urial in estrous will be claimed by the dominant male. After mating, he guards her from other males until she’s no longer receptive, then he leaves in search of another female.

Discover more exceptional specimens in A Little Gay Natural History. Pick up a copy, priced £9.99, from the Museum Shop or online at nhmshop.co.uk.

Both rams and ewes use their horns as tools for eating and fighting. The horns help absorb the impact during head butting and reduce the risk of brain injury.

Male urials engage in a range of homosexual behaviours similar to how bighorn sheep rub each other with their horns during courtship before mounting. One species is said to live in ‘homosexual societies’.

There are seven species of wild sheep in the world. They can be found across much of the northern hemisphere from North America through Russia and Asia down into the Middle East.

Unravel the epic story of birds, discover the secrets to their success and learn some of their surprising and often shocking tactics for survival in the Museum’s exciting new exhibition.

Birds are everywhere; from grassy steppes to humid jungles, baking deserts to icy ones, open oceans to town centres; from half a kilometre deep in the ocean to over 11 kilometres up in the sky. Globally, nearly 11,000 species of bird live across all continents and countries, all finding ways to survive with an astonishing array of senses, skills and behaviours.

Their ubiquity means that most of us probably encounter birds regularly, but they’re often just part of the background to our busy lives. During the lockdowns triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic, the presence of birds took on a new

MUSEUM EXPERT Dr Joanne Cooper

Senior Curator of the avian anatomical collections at the Natural History Museum, Joanne works across both the avian osteological and spirit collections, this includes some 35,000 specimens in total.

significance for many people. Being able to watch them became a vital connection to nature. The awareness of our bird neighbours was heightened further by the sudden loudness of their songs, as the usual din created by humans was dampened. Even though we value birds, living alongside us is taking its toll on them. Almost half of bird species worldwide are declining, with one in eight globally threatened. Our connection with nature is more crucial today than ever, as conservation organisations engage people to reverse declines.

In 1861, the discovery of the 150-millionyear-old Archaeopteryx lithographica in a German quarry stunned palaeontologists. Its combination of a small reptilian skeleton surrounded by the imprint of feathered, birdlike wings and a long, plumed tail was the first evidence of a link between birds and dinosaurs. Intensely researched, it held a pre-eminent position as the earliest bird for well over a century.

Over the past few decades, our understanding of the evolution of birds has advanced rapidly, underpinned by an expanding trove of Jurassic

Above Archaeopteryx shows evolution in action: the transition between dinosaurs and birds.

and Cretaceous fossil birds, especially from northeast China where many finds include wellpreserved plumage. Discoveries in dinosaurs have also been crucial, particularly of feathered dinosaurs from the same Chinese fossil horizons. The now thoroughly tested conclusion is that birds are dinosaurs, sharing features such as feathers, warm-bloodedness, bipedalism, laying eggs and wishbones that place them in the theropod group with Tyrannosaurus. Archaeopteryx has been joined by several other long-tailed and winged species and is now recognised as being closer to dinosaurs

With their long tail and similar body size, reconstructions of Archaeopteryx often resemble a Eurasian magpie. Analysis of a wing feather has revealed it did have black plumage, but the pattern is unknown.

– l r l i f the ancestor of birds, but not a direct ancestor itself.

a close t ve of he an sto f irds, ut no direc ncesto t lf.

oothless, beak d b rd bout ago

Toothless, beaked birds appear about 131 million years ago, with some sporting tail feathers longer than their bodies. The first bird group known to have gone global were the successful Enantiornithines. With some internal features marking them apart from true modern birds, they would look familiar – until you saw their teeth, which some birds had until about 66 million years ago. By this time, hundreds of species had evolved. Flitting through forests, swimming in seas, birds were thriving alongside dinosaurs and the flying reptilian pterosaurs. Then, about 66 million years ago, an asteroid collision triggered changes in the global environment and a resulting mass extinction of over 70 per cent of species on the planet. Non-bird dinosaurs and pterosaurs were wiped out, along with most birds. But some did survive – small, ground-dwelling species that could weather the devastating loss of forests.

The species that survived the asteroid collision were highly specialised, shaped already by the demands of their high metabolisms and flight. They all shared hollow bones, highly efficient breathing systems, feathers, toothless beaks and relatively large brains. Despite all the apparent diversity in today’s birds, their basic body plans are remarkably similar, a reminder of the evolutionary bottleneck they passed through.

Nevertheless, in the first few millions of years after the strike, birds evolved rapidly through innovative adaptations to take advantage of new ecological opportunities. The huge range of external shapes, sizes, behaviour, plumage and colour we see today is the result of millions of years of subsequent refinement of this initial explosion. The fossil record provides the physical remains of ancient birds and evidence of their appearance and lifestyles, but to fully appreciate birds’ extraordinary abilities, we must look at their modern descendants.

Wherever they live, birds share a need to find food and mates, raise young and for those young to stay alive long enough to launch a next generation of their own. Every species has its own unique set of adaptations and strategies, some of which we appreciate when we watch birds, such as flight and complex courtship displays, or listen to songs and calls. However, much of the world of birds lies outside our comprehension.

For example, birds can see four channels of primary colour (humans see three) and many birds can also see into the ultraviolet spectrum, adding another layer of brilliant colour perception. One way in which birds exploit this ability is with UV reflective areas of plumage that send signals about their health to prospective mates.

‘After the asteroid strike, birds evolved rapidly to take advantage of new ecological opportunities’

For most birds that don’t make a significant seasonal migration, they may need their wits to survive a tough winter, using their intelligence to solve problems or remember their way to food. Birds have tightly packed brain neurons, meaning that despite their overall small size, bird brains can be brilliant brains.

Flight brings different sight needs. Birds can not only resolve rapid movement, distinguishing detail when flying that would be a blur to humans, but can also detect slow movements, such as the track of star constellations at night or the sun by day, which they use to navigate. It’s even possible that birds can ‘see’ the earth’s magnetic fields with a specialised form of light receptor cell, which gives another way to navigate, helping them build up sensory maps. Such super-senses allow migratory birds to follow seasonal changes, seeking breeding ground or food when local sources decline.

Above Birds are a hugely diverse group, ranging from a 2.5 gram bee hummingbird to the 150kg common ostrich. The Philippine eagle (left) is one of the world’s largest eagles, while the Sri Lankan jungle fowl is from one of the earliest known modern bird groups.

Some members of the crow family have overall intelligence measuring close to great apes. Common ravens can deceive each other and plan their way through a challenge to a food reward; Eurasian jays can remember where thousands of acorns are hidden in autumn to retrieve them in winter. Even small birds can surprise us with the capacity for smart innovation. In especially harsh conditions, a population of great tits in Hungary has learnt the gruesome habit of pecking out the brains of bats hibernating in a cave, a trick being passed along through their social networks.

FOCUS ON: Blue bird-of-paradise

Male birds-of-paradise sport an extraordinary range of colours, plumage, displays and calls to attract females. Research shows that species with the most complex colours, such as the blue bird-of-paradise, also have the most complex vocal performances.

FOCUS ON: Kaua’i ‘Akialoa

This is an extinct species of honeycreeper from Hawaii, distinguished by its long bill for probing for insects. Since humans arrived, 30 out of 50 honeycreeper species have become extinct, wiped out by habitat loss, invasive species and the diseases carried by introduced mosquitoes.

Studying the diversity in the shapes and sizes of bird beaks helps us understand evolution, but has often focused on a relatively few species at a time. Using the collections at the Museum, a team of researchers from the University of Sheffield analysed beaks from over 8,500 species across 200 bird families, using high-resolution 3D scanners to create virtual models.

With such a huge number of scans to process, the team turned to citizen scientists online to help landmark the models, highlighting key features on the beak such as the tip and edges, which allowed all beaks to then be measured and compared. Using this unprecedented dataset, the team is exploring the timing and rate of evolution in modern birds. One study compared beak shapes to a DNA-based evolutionary tree, revealing rapid diversification after the dinosaurs died out, followed by slower rates as evolution became more about fine tuning.

FOCUS ON: Common swifts

For hundreds of years, swifts have nested harmlessly in the roofs of old buildings. In our modern world, they are kept out of new buildings, and lose old sites to refurbishment or demolition, contributing to their ongoing decline. Swift bricks built into new developments are a simple solution to offer new nest sites. Steps like this are conscious actions we can take to help birds live alongside us.

The greater adjutant stork is poisoned by rubbish dumps, where pollutants are disposed of with food.

Puffins rely on small, proteinpacked sandeels to feed their chicks. But the decline in sandeels due to rising sea temperatures is causing chicks to starve.

Despite their long history and accumulated amazing survival strategies, most birds are struggling to cope with human impacts, with more than 1,400 species threatened with extinction and many more declining. With many extinct species known from millions of years of fossil record, why does this matter?

Extinction rates and risk are difficult to measure, but researchers agree that modern birds face an unprecedented extinction threat, with some suggesting that current rates of extinction are over a thousand times greater than natural background rates. Since about 126,000 years ago, 1,300–1,500 bird species have gone extinct, almost all human-caused, driven by habitat loss, introductions of non-native species and overexploitation. Already, we have pushed more than one in nine bird species to extinction, most recently the Alagoas foliage-gleaner of eastern Brazil, last seen in 2011.

‘Most birds are struggling to cope with human impacts’

FOCUS ON:

Albatross chick

Chicks of the largest albatrosses are left for days at a time while their parents forage over thousands of kilometres of ocean. At sea, albatrosses are threatened by entanglement in commercial fishing gear. Since 2005, the Albatross Task Force has been working globally with fisheries to prevent albatross deaths through education and switching to bird-safe practices, reducing the death tolls in some fisheries by 95 per cent.

Birds provide vital ecosystem services, helping create and balance functioning habitats with their activities, such as fertilising forests and coral reefs, dispersing seeds, pollinating plants and disposing of carcasses. Birds are also a ‘barometer for planetary health’ – indicators for the overall state of the natural world. Losing birds not only contributes to the unravelling of the interconnecting webs needed in fully functioning ecosystems, but also acts as a warning of the damage being done –which impacts us as well. The connection humans have had with birds for millennia goes deep.

An award-winning bird taxidermist, Elle concentrates on naturalistic taxidermy. Her pieces fill homes across the world and she fulfils requests for film sets, interior designers and museums.

Taxidermy allows us intimate insights into birds’ unique physical adaptations, while serving as an educational resource and taxonomic record.

Unusually for the Museum, new taxidermy was commissioned for Birds: Brilliant and Bizarre, including nine specimens – a rose-ringed parakeet, three common swifts, a red kite, a house sparrow, a grey squirrel, and two white-tailed sea eagles.

The white-tailed eagles dominate both in size and in labour. Processing the eagles begins with the removal of the skin from the carcass, a delicate and time-consuming craft of unravelling the skin like a jacket from the body. The skin is peppered with organic material: sinews, fascia, fats and meat, which all needs to be carefully removed by hand – aided by a de-fatting machine –to allow optimal results. As the dermis becomes cleaner and more fragile, we move to preservation. Long soaks in concoctions of non-toxic chemical compounds and treatments are needed for such big

skins. I aim to change the skin’s properties from organic, which can rot, to something more stable, closer to a material or fabric. Dirt is scrubbed out of the feet, and the skull is flushed clean.

Now it’s time to start rebuilding the bird’s impressive stature. Using the carcass as a reference and callipers to check measurements – such as length of the femur, the width of the eye sclera and so on – I build an anatomically accurate representation of its internal architecture from balsa wood, pine inserts, wooden dowel and threaded bars.

Next, I unite the body with the preserved, washed skin, complete with fluffedup feathers, colour and shine restored. Using photos, I set the eyes in a way that communicates an expression, the brow forward and intense, the head feathers alert and dynamic. Manoeuvring a bird of this size and weight, with a wingspan of almost three metres, demands a lot of physicality and strength. The bird now undergoes a period of ‘drying’, allowing

all the mechanics to set in place under a skin that encases it like a shell. Only then will this great bird be ready for display. It’s a privilege to work on such remarkable specimens, knowing they will be placed in the Museum’s collections after the exhibition and become part of a unique legacy.

‘Birds face their greatest challenges today. But actions great and small are making a difference’

Birds offer not just warning, but also hope. Given a chance, their resilience can be remarkable. Birdof-paradise populations recovered after industrialscale exploitation for their plumage was stopped in the 1920s. The tiny black robin or karure of Rēkohu Chatham Islands was down to one breeding female in the early 1980s, but now there are more than 300 in its island reserves. On the former intensively farmed Knepp estate in West Sussex, critically endangered turtle doves and nightingales breed successfully, while other birds thrive in its rewilded scrubland at densities not recorded anywhere else in the UK. With resources and will, actions can be taken to prevent extinctions and and reverse declines. While

Below Habitat loss and fragmentation from timber cutting and hunting for food and casque ivory are the greatest threats to Asia’s forest

organisations such as the RSPB and BirdLife International co-ordinate efforts on a large scale, the determination of individuals or small groups to buck the trend can also be decisive. Two examples are the Hargila Army movement in Assam, initiated by Dr Purnima Devi Barman to protect the nesting and roosting sites of the greater adjutant stork, or the pioneering efforts of Roy Dennis in reintroducing red kites and white-tailed eagles to the UK.

Birds have survived through 150 million years, but face their greatest challenges today. With human impacts unchecked, some species will adapt and cope, but they will represent a fraction of their dazzling diversity. Their loss will be our loss in so many ways. But all over the world, actions great and small are making a positive difference. There are ways for birds and humans to thrive together far in the future; it’s up to us, from governments to individuals, to choose to make them happen. ●

With over one million specimens representing 95 per cent of bird species, the Natural History Museum houses one of the largest and most comprehensive bird collections globally.

It includes study skins (specimens preserved using a style of taxidermy that differs to the poses you normally see), mounts, skeletons, spirit specimens (preserved in fluid and stored in glass jars), eggs and nests. They span the history of the Museum, from rarities over 270 years old, to specimens being cleaned in our beetle colonies today.

The collections hold many historically important, extinct and endangered taxa, many of which are rare or even unique in museums. Since the early 1970s,

the bird collections have been located at Tring, Hertfordshire. Looking after them, creating records and digitising all of them ensures they’re all available for research, outreach and exhibitions.

Nearly 200 visitors a year from around the world use the collections in person, while staff help many more researchers with loans and enquiries. Our team of curators, researchers and scientific associates also carry out wide-ranging research, not only on birds across the whole planet, but also across thousands of years.

The bird collections are used for all sorts of studies including taxonomy, comparative anatomy, zoogeography, genomics, archaeology evolution, ecology, palaeontology and art.

FOCUS ON:

White stork

In 1822, a white stork shot in Klütz, Germany, was carrying a 75cm long arrow in its neck. The arrow revealed it had flown 2,000 miles from Africa after surviving the injury. It was the first evidence of how birds moved with the seasons on migration. Two hundred years later, white storks from the Knepp Estate are tracked on their journeys to Morocco using GPS tags.

Birds: Brilliant & Bizarre

Until 5 January 2025

Explore the incredible story of birds – from how they have used brilliant and fascinating techniques to adapt to a changing world, to how we can help them in the future. nhm.ac.uk/birds-brilliant-bizarre

Members and Patrons get free, unlimited entry, do not need to book and have priority access.

Birds: Brilliant & Bizarre reveals how birds have survived for millions of years and describes their surprising and sometimes extraordinary behaviours, such as zebra finches that sing to regulate the temperature of their eggs.

Priced £9.99, Birds: Brilliant & Bizarre is available from the Museum’s Shops and online at nhmshop.co.uk. Members and Patrons receive a 20 per cent discount.

In the past 20 years, the puzzle of human evolution has become ever more complicated. To work out how new species, unknown migrations and ancient tools fit together, it’s not only a question of space – but also of time.

WORDS: JAMES ASHWORTH

Imagine trying to finish a jigsaw without a clue what the finished puzzle should look like. There are no edges to guide you and many pieces are missing or damaged. Now, replace these jigsaw pieces with fossils. This is the challenge faced by experts in human evolution, or palaeoanthropologists, as they try to work out where our species comes from.

Fortunately, the broader picture is starting to become clearer, thanks to the development of dating technology. Recent advances are providing an unprecedented insight into the origins of Homo sapiens and our relatives, revealing that they are much more complex than first thought.

Before the first dating technologies were developed, studying the past was a matter of

MUSEUM EXPERT

Professor Chris StringerResearch Leader for our Centre for Human Evolution Research at the Museum, generously supported by The Calleva Foundation, Chris has spent his career investigating Homo sapiens and close relatives to find out how humans spread around the globe.

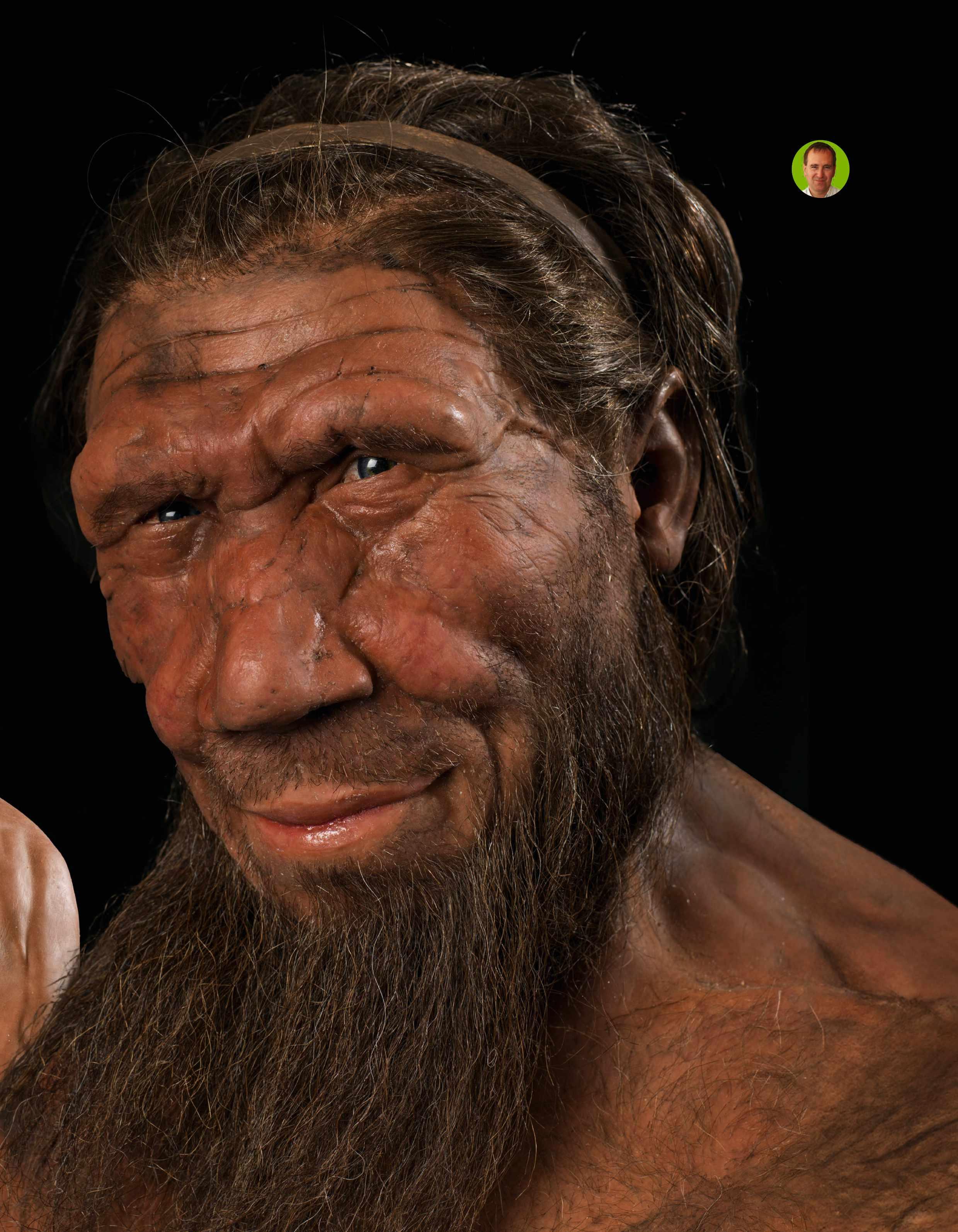

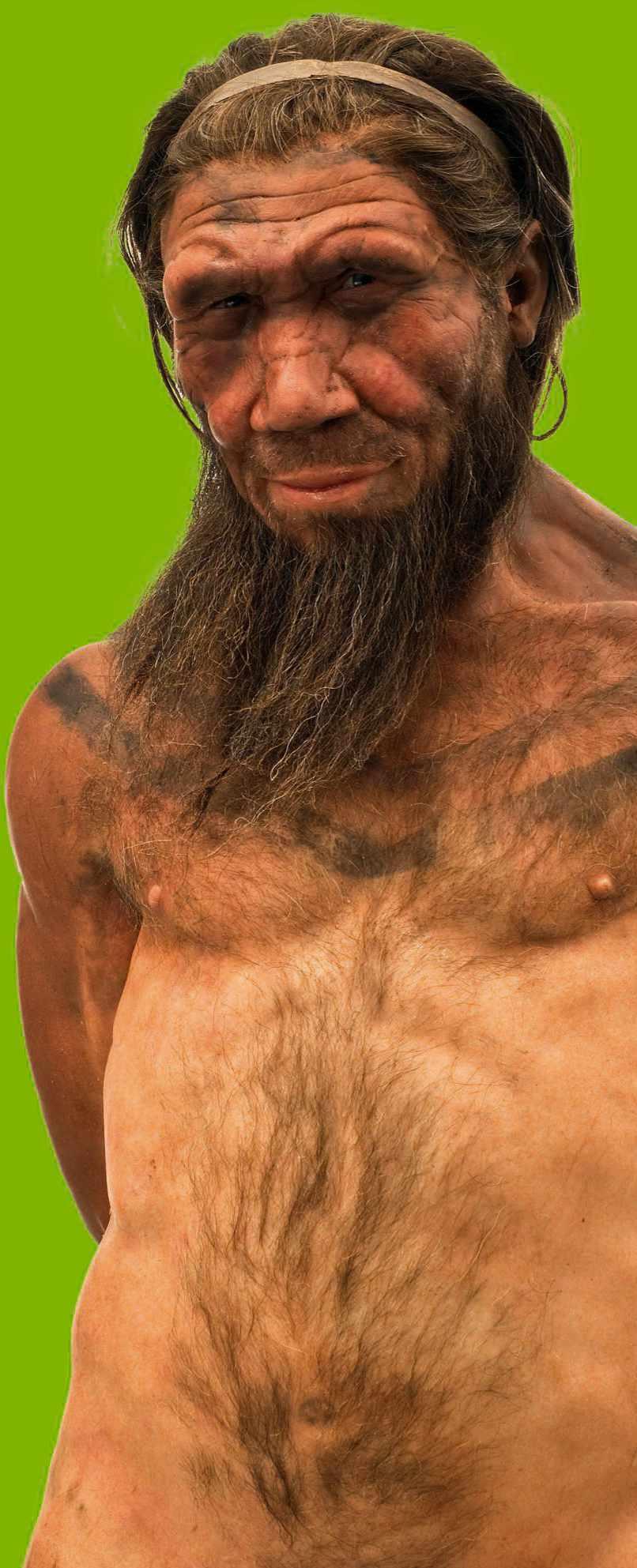

Neanderthals were humans like us, but they were a distinct species called Homo neanderthalensis. They ‘overlapped’ with modern humans (left) for over 10,000 years.

educated guesswork. While finds from the recent past might be able to be dated by archaeological remains or written records, the age of early humans was much harder to infer. When the first Neanderthals were uncovered in the 1800s, for instance, geologists had to rely on comparing the sequence of rocks to work out what was older. The lower the layer, the greater the age.

It would take around a century before fossils could be dated more precisely. In the 1940s, scientist Willard Libby finally hit upon a reliable way to date the remains of once living things. Professor Chris Stringer explains: ‘Libby realised that living things stop taking up carbon-14 when they die, and that this decays at a set rate. This means that the amount of carbon-14 left in fossils can be used to calculate their age.’

Unfortunately, radiocarbon dating, as the process is called, only works on organic materials from the past 50,000 years or so. Beyond this point, there’s so little carbon-14 left in a sample that it’s virtually impossible to date. Fortunately, life has another unique property that can be used to date it – the direction of its molecules.

‘While an organism is alive, all of its amino acids are oriented in one direction,’ Chris explains. ‘After death, the amino acids gradually begin to flip the other way, and eventually stabilise with equal amounts pointing in either direction. The proportion facing in each direction can, in principle, be used to work out how old a fossil is.’

This process, which can be used to date shells associated with human artefacts or fossils, has some differences to radiocarbon dating. One of the most important is that carbon-14 decays at the same rate, no matter the conditions, but higher temperatures can cause the amino-acid flipping to speed up, while cooler conditions slow it down. This makes it difficult to make direct comparisons between the dates for fossils found in warmer continents like Africa to those found in cooler Europe. Fortunately, scientists have other dating techniques in their arsenal.

With the drawbacks of biological dating methods, researchers also rely on inorganic tests like U-series dating to work out the age of fossils. Uranium is naturally found in small amounts in water, and once it gets into the body it tends to end up in the bones. As this radioactive element’s half-life is much longer than that of carbon-14, U-series dating can be used on fossils that are older, up to hundreds of thousands of years old. However, just as uranium can get into bones during life, it can also enter after death and this can pose issues for getting an accurate date.

‘When there’s movement of water, any uranium that is in a fossil may be washed out, or more may be added to it,’ Chris says. ‘To date these bones,

Homo naledi

Homo naledi is currently dated to between 335,000 to 236,000 years ago. Narrowing or extending this range would reveal what species H. naledi lived alongside, and provide context to controversial claims on its culture.

Homo luzonensis

The best-known Neanderthals lived between about 130,000 and 40,000 years ago, after which all physical evidence of them vanishes.

Originally dated to around 65,000 years old, Professor Rainer Grün’s recent dating doubles this to about 130,000. This makes it less likely Homo luzonensis lived alongside our species, though more fossils could change this conclusion.

Neanderthal, Krapina

These remains are currently dated to around 130,000 years old. But unpublished work by Stringer and Grün, and similarities to much older remains found elsewhere, suggest these fossils could be over 100,000 years older.

Omo-Kibish 2

Ethiopia’s Omo-Kibish 1 is about 200,000 years old, making it one of the oldest fossils to look recognisably like we do today. Omo-Kibish 2, found nearby, is often assumed to be the same age, but could be older.

Homo longi

Uncovered in China, this species, dubbed ‘Dragon Man’ is thought to be at least 146,000 years old. But further work on this discovery is needed to provide a more accurate estimate of its age.

More than 100 Homo floresiensis fossils have been unearthed from at least 14 individuals in Liang Bua Cave on the island of Flores, Indonesia.

Neanderthal, Tabun

A skeleton discovered in this Israeli cave is one of the most complete ever found, but its age isn’t well established. Rainer and Chris’ research suggests it might be around 170,000 years old, but this needs further confirmation.

Apidima 1 and 2

A ~210,000-year-old Homo sapiens skull was found alongside a ~170,000-yearold Neanderthal skull in the eponymous Greek cave. It reveals that our species was leaving Africa long before the major migration out of the continent.

Sima de los Huesos

Deep in a Spanish cave, dubbed Pit of Bones, 29 fossil hominins, thought to be early Neanderthals, were found. Age estimates range from 250,000600,000 years old, and further direct dating would help to confirm a more precise figure.

you have to take multiple samples from different layers of the bone and model the way the uranium has been taken up. By studying how much uranium has decayed, you can estimate the age of the fossil.’

However, U-series dating can only provide a minimum estimate of how old a fossil is. So it’s often accompanied by other techniques, such as electron spin resonance (ESR) dating. This process, which is mostly used on fossil teeth, relies on natural radiation from the surrounding environment bombarding the atoms inside a fossil tooth. This displaces the electrons in tooth enamel, where they get trapped. The more that are trapped, the longer the process has gone on. After estimating the previous radiation dose from the sediment surrounding the fossil, researchers can put an age to the sample.

The holy grail of dating

With their ability to help date fossils many hundreds of thousands of years old, ESR and U-series dating have become popular among palaeoanthropologists. But the gold standard of this field is a process known as argon-argon dating, which calculates an age for an object using the decay of a radioactive form of potassium to the gas argon. The technique is able to estimate the age of items millions, or even billions, of years old, allowing it to date not just fossils, but also Moon rocks and other ancient geological specimens. There’s just one catch – you need a volcano for the process to work. ‘After volcanos erupt, the argon in the lava is dispersed,’ Chris explains. ‘As the rocks cool, the argon starts to reaccumulate

Facial modification was one of the first steps in the evolution of the Neanderthal lineage, pointing to a mosaic pattern of evolution, with different anatomical and functional modules evolving at different rates.

at a constant rate, providing us with a long-running clock to put a date onto fossils. Important sites like Olduvai Gorge, in Tanzania, experienced eruptions that allow us to date some of its fossils with great precision. Unfortunately, many of our fossil human sites in places such as Europe and China just don’t have the necessary volcanic activity.’

Together, these dating methods have enabled experts to firm up the ages of fossils from around the world, confirming when and where important events took place. Researchers aren’t resting on their laurels, though, as they continue to refine and improve these processes.

One big advance has actually been quite the opposite – miniaturising the process. While precious human fossils once had to be sectioned or drilled into with large tools in order to take samples, today’s lasers can make tiny pinpricks that work just as well for dating.

In 2019, a groundbreaking discovery was announced – the unearthing of Homo luzonensis. Found in a cave in the Philippines, this diminutive species is one of our most recently discovered relatives.

Its discovery was important for many reasons, not least of which is because it’s a new species from southeast Asia –a region of the world which, historically, has not been well explored for human fossils.

It’s not just southeast Asia, either. While Europe, Siberia and eastern and southern Africa often attract attention in the search for our ancient relatives, other parts of the world tend to be overlooked. Studying these areas could lead to the discovery of more fossils, and even new species.

Professor Chris Stringer believes western and central Africa might be a promising place to start. ‘Not many people

A small-bodied hominin – identified from seven teeth and six small bones – lived on the island of Luzon at least 50,000 to 67,000 years ago.

have looked for human fossils in these heavily vegetated and hard-to-access regions,’ he says.

‘However, the discovery of stone tools suggests that humans were living in western and central Africa hundreds of thousands of years ago. Promising sites might be found near lakes and rivers, as the water can help to expose fossils buried in the ground.’

Scientists are also expanding the range of materials they can date. ‘Amino-acid dating has mostly been used on molluscs, as their remains are often found alongside human fossils,’ explains Chris. ‘A team at the University of York are now working to create methods that would allow the teeth of mammals such as mammoths to be dated. This would help put an age to important sites in Africa and Europe where these remains are a common find.’

As more and more fossils have been dated, they’ve built up an unexpected picture of our evolution. It seems that, before migrating out of Africa all in one go, small groups of pioneering Homo sapiens made multiple forays out of the continent. One of the most exciting finds is in Apidima Cave, in Greece, where two supposed Neanderthal skulls were found close to each other. However, later studies showed that one of them was actually the rear part of a Homo sapiens cranium.

While it was assumed the Neanderthal population came first, and was later replaced by our species, U-series dating reveals this wasn’t the case. ‘The Homo sapiens fossil is at least 210,000 years old, which makes it the oldest-known member of our species outside Africa,’ Chris says. ‘Not only that, but it’s probably 40,000 years older than the Neanderthal fossil found nearby.’

This finding was controversial, and not without good reason. While dating techniques can provide accurate ages for fossils, researchers have to be certain what exactly they’re measuring. ‘You have to assess how a fossil has been deposited, as this can affect attempts to date it,’ says Chris. ‘If a fossil has been redeposited in a different layer of sediment, either naturally or by human burial, its age could be completely different to its surroundings.’ Differently aged sediments can also sometimes end up in other layers, a factor that affected the discovery of Homo floresiensis. Initially thought to be less than 20,000 years old, it turned out that much younger sediment had been deposited near the fossil, which is now thought to be around three times older.

In the case of Apidima, Chris’s colleague Professor Rainer Grün recently redated the bones and their surroundings to confirm their findings. ‘While it had already been suggested that the skulls had different ages, we confirmed they were buried at different times,’ Chris says. ‘It was only around 150,000 years ago that they were cemented together in the rock, many thousands of years after their separate deaths and deposition.’

With more careful dating, the future seems bright for the study of human evolution. As scientists continue to narrow down where and when our ancient relatives were living, we’ll get closer to understanding how our species first came into existence. ●

In the early 1920s, miners made a startling discovery – an ancient human skull and fragments of bone – in the Broken Hill mine in what is now Kabwe, Zambia. The importance of these fossils was quickly appreciated, and they were donated by the mine’s owners to what was then the British Museum, but is now the Natural History Museum. Here, they were studied by Arthur Smith Woodward, the Keeper of Geology, who declared the bones to be from a new species - Homo rhodesiensis. Since then, other scientists have classed the bones as belonging to Homo heidelbergensis. Comparisons with other sites in Europe and Africa suggested that the fossils were likely around 500,000 years old, but the bones had never been formally dated.

One of the main reasons for this is because nothing of the original mine now remains, leaving little for scientists to date. Instead, Chris and the team of researchers working on the dating used a combination of U-series and ESR dating to narrow down the skull’s age.

‘As the surrounding site had been quarried away, we had to look for other ways to get samples,’ Chris says. ‘We used small parts of the cranium, sediment scraped off it, as well as animal fossils taken from the mine, to date the skull to around 299,000 years old – much younger than expected.’

Instead of linear evolution, human species such as ‘Rhodesian Man’ and early Homo sapiens probably lived side-by-side in Africa.

The skull’s new age changed our outlook on human evolution. When it was dated to 500,000 years ago, Homo heidelbergensis became a likely candidate for being a direct ancestor of not just our species, but also of the Neanderthals. But after the reassessment, Homo heidelbergensis became a less likely ancestor for our species, something that is backed up by new studies examining the species’ distinctive anatomy.

An age of around 300,000 years means it was co-existing with early Homo sapiens-like humans in the continent, as well as Homo naledi in southern Africa.

At the same time, Neanderthals and Denisovans were also evolving elsewhere in the world, making it difficult to pin down how exactly the species are related.

This shatters historic views of human evolution, which saw Homo sapiens and our ancestors as a series of discrete species who gave way to their successors over time. Instead, different species went in their own evolutionary directions, occasionally interacting and interbreeding.

Redating other important specimens like the Kabwe skull would give researchers further insights into the evolution of our ancestors, and how our species came to be.

Since the 1970s, the Zambian Government has asked for the Broken Hill skull to be returned. In 2018, it was agreed that Zambia and the UK would pursue bilateral discussion, which has been started. The Museum is committed to constructive participation in this ongoing dialogue.