Celebrating 60 years of Wildlife Photographer of the Year

Celebrating 60 years of Wildlife Photographer of the Year

Autumn is here and there’s so much to discover!

This year, we’re celebrating the 60th anniversary of the Wildlife Photographer of the Year Competition, which has led the world in recognising the best nature photography since 1965. Sta�ting out with just 361 entries, this year we received a record-breaking 59,228 entries. In this issue of Natural History Museum magazine, we share a selection of our favourite images from the contest – see page 24.

You can see more of the judges’ choices – and choose your own favourites – in the exhibition. Remember that as a member or Patron you can visit the exhibition for free as many times as you like – and there’s no need to pre-book.

We also take a look back at the evolution of the competition, sharing some of the highlights, the amazing people who have shaped it, and some incredible ‘�rsts’ achieved along the way. See page 32.

With the Museum’s gardens now open for you to enjoy, we reveal how Fern, our stunning free-standing bronze Diplodocus cast, was constructed in the Jurassic Garden, suppo�ted by Kusuma Trust.

A year after samples of the asteroid Bennu – a primitive rock unchanged since the early solar system – arrived at the Museum, Professor Sara Russell explains what they have revealed and what’s next in the search for life. See page 46.

We’re celebrating the 60th anniversary of the Wildlife Photographer of the Year Competition –and its many ‘�rsts’

Already embedded in our daily lives, a�ti�cial intelligence (AI) is almost inescapable. As the Museum increasingly harnesses AI in our scienti�c research, in recording and caring for collections, in powering data-gathering and in forecasting visitor numbers, we look at what it is and whether it could even help predict evolutionary change. See page 38.

Thank you for your ongoing suppo�t, which is so impo�tant to us. It helps us to in�uence solutions to global challenges and continually advocate for nature and our planet.

Adam Farrar Director of Commercial and Visitor Experience

Join the conversation

Instagram natural_history_museum

Facebook naturalhistorymuseum

X NHM_London

TikTok @its_nhm

Youtube @NaturalHistoryMuseum

The Anning Rooms

Named in honour of legendary fossil hunter Mary Anning, this suite is exclusively for your enjoyment. Tuck into tasty lunches and snacks in the restaurant, take in the views from the lounge, or read a book in the study area.

Get free, unlimited entry to all of the Museum’s ticketed exhibitions, such as Birds: Brilliant & Bizarre and Wildlife Photographer of the Year 60, and guaranteed entry to our free exhibitions and installations.

Enjoy private exhibition views, workshops and a new series of talks, Dig Deeper, led by Museum scientists. As well as discounted tickets you will also receive priority booking and access to a special Members’ Bar on the night.

and café discounts

Receive a 20 per cent discount in the Museum’s shops – which are stocked with a wide range of inspiring gifts, books and clothes – as well as a 10 per cent discount in our cafés and restaurants.

Never miss an issue of Natural History Museum magazine

The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD

The Natural History Museum at Tring, Akeman Street, Tring, He�tfordshire HP23 6AP

Email magazine@nhm.ac.uk

Find back issues on the Hive, an exclusive digital hub especially for you. There are over 800 pages to enjoy, featuring the Museum’s research, exhibitions and events. nhm.ac.uk/the-hive

Becky Clover Becky is an ecologist and urban biodiversity o�cer working on the Urban Nature Project, based in the Angela Marmont Centre for UK Nature.

Dr Sophia Nicolov

Sophia is an Early Career Research Fellow, working with the Cetacea collection and specialising in environmental history.

Sir Patrick Vallance Chair of the Board of Trustees until July, Patrick was Government Chief Scienti�c Adviser (2018–2023), knighted twice for his contributions to science.

24 Wildlife Photographer of the Year

We share some of our favourite images from the 2024 competition.

32 More than a pretty picture

To celebrate the 60th anniversary of Wildlife Photographer of the Year, we look back through time at some of the competition’s highlights.

38 Welcome to our AI Museum

As a�ti�cial intelligence permeates our lives and our Museum, we reveal how clever technology is transforming our scienti�c research, care for collections and visitors’ experience.

46 Decoding space dust

When space rocks from asteroid Bennu returned to Ea�th, Museum scientists were at the forefront of analysing them to reveal the secrets of the solar system.

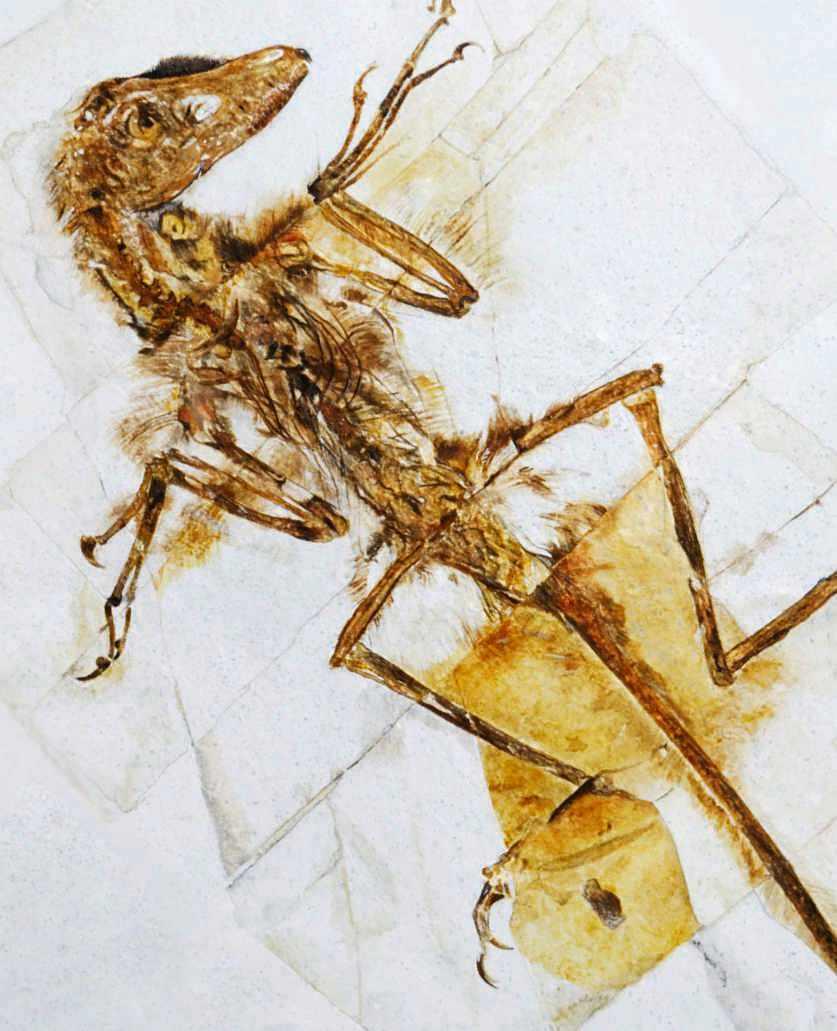

52 10 dinosaur fossils that changed everything

Discover some of the most signi�cant dinosaur �nds of our time, and learn how these fossils changed our understanding of the way they evolved and lived.

58 Standing up for nature

City of Trees CEO Jess Thompson reveals how trees can boost our health and wellbeing, and help tackle the climate and biodiversity emergency.

12 New at the Museum

This issue, we bring you an update on our pioneering work to put nature at the hea�t of education, reveal what our scientists carry in their rucksacks, and experience the future in Visions of Nature, our �rst-ever, mixed reality experience.

16 What’s on

Exhibitions and events for Museum Members and Patrons, plus a 60-second chat with symphonic metal band Nightwish.

18 Science in focus: Revealing a whaling past We explore the history and signi�cance of some of the whale specimens in our collections.

20 Inside story: Johnathan Leighton Johnathan ensures neurodivergent and learning-disabled children can experience the Museum.

22

Exceptional specimen: Bringing Fern to life

Find out why our 22-metre-long, bronze dinosaur cast, Fern, is a remarkable feat of engineering.

52

6 View�nder

Three extraordinary images that amazed everyone at the Museum.

62 Living with nature

Find out how our newly opened gardens will continue to be among the most closely monitored urban green spaces in the UK.

66 From the Archive

Step back in time to 1878, when the British Museum moved its natural history collections to their new home in South Kensington.

Senior Editor Helen Sturge

Editorial team Kevin Coughlan, Josh Davis, Adriana De Palma, Alessandro Giusti, Dr Peter Olson, Jennifer Pullar, Emilie Pearson, Dr Helen Robe�tson, Professor Sara Russell, Dr Tom White and Colin Ziegler

For Our Media

Editor Sophie Stafford

A�t Editor Robin Coomber

Production Editor Rachael Stiles

Account Manager Debbie Blackman

Editorial Director Dan Linstead

Contributors James Ashwo�th, Paul Bloomfield, Georgie Britton, Andrew Burgess, Becky Clover, Troy Donockley, Adam Farrar, Professor Anjali Goswami, Laura Jacklin, Ashley King, Lucy MinshallPearson, Dr Sophia Nicolov, Johnathan Leighton, Maja Petric, Lizzie Raey, Sarah Ralph, Pauline Robe�t, Kathryn Rooke, Ben Scott, Siobhan Sharp, Evie Smith, Sam Thomas, Jess Thompson, Sir Patrick Vallance

With thanks to Ed Baker, Professor Paul Barrett, Jen Benson, Nick Crumpton, Tom McCa�ter, Armando Mendez, Tobias Salge, Dr Vincent Smith, Helen Wallis

The views expressed in Natural History Museum magazine do not necessarily reflect those held by the Natural History Museum. Produced in association with Our Media. ourmedia.co.uk

All photographs and copy © 2024 The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London unless otherwise stated. If you would like copies of any Museum images please contact the Museum Picture Library on 020 7942 5401.

ISSN 2044-7582

The paper used for this publication is responsibly sourced, and has enabled the capture of 57kg of CO2 at Thorney Coppice, No�thamptonshire. Learn more at forestcarbon.co.uk

Natural History Museum magazine is mailed in packaging using potato starch along with other biological polymers. It is totally biodegradable and compostable and can be disposed of in the green recycling bin or a home compost bin. It can also be used in your food waste caddy.

Our Media Company is working to ensure that all of its paper comes from wellmanaged, FSC®-ce�tified forests and other controlled sources. This

You are probably very familiar with the chirp of a cricket, but did you know some moths can also produce sound? Male hawkmoths have special scales on their reproductive organs that they rub against their abdomens to produce high-pitched squeaks (stridulation). While some of these sounds are audible to us, most are ultrasonic – and they can be heard by bats.

For over 200 million years, moths have been pe�fecting the techniques to communicate with each other or with predators, such as bats. One reason why moths stridulate could be to jam the bat’s echolocation, confusing them enough to avoid being eaten.

The Museum is imaging thousands of stridulatory scales from di�erent species of hawkmoth to uncover the tiny details that make each species unique – and reveal not only their hidden beauty, but also the incredible strategies they’ve evolved to survive.

A

decade of dust

The Museum’s Mammals gallery is home to four whale skeletons, which were last cleaned 16 years ago. With the recent refurbishment of the gallery, our conservation team was �nally able to access the specimens and pe�form the huge task of repairing, stabilising and cleaning them. Dust attracts moisture that can weaken bones, and also pests, including microorganisms, that can damage them.

So the team carefully vacuumed up two thick layers of dust, a soft �u�y top layer and a compacted lower layer. Thanks to the refurbishment, the skeletons will now be cleaned every year.

Watch the cleaning of a 14-metre bowhead whale that was collected in 1881–1882 and has been in the collections since 1934, here: bit.ly/whale-clean

The lesser �amingo is in danger of being forced to leave its historic feeding grounds in East Africa’s lakes, putting the population at risk. New research, led by Natural History Museum scientist Aidan Byrne, used two decades of satellite data to study all the key �amingo feeding lakes in Ethiopia, Kenya and Tanzania.

The data revealed that rising water levels are reducing the salinity of the lakes, and decreasing the abundance of phytoplankton, the birds’ main food source. While the exact causes aren’t clear, climate change, deforestation and changes in water use are thought to be to blame.

The lesser �amingo is the most numerous of the six �amingo species, but the whole population uses just a handful of breeding sites. Aidan warns that the search for food is likely to push the species into new, unprotected areas.

Putting nature at the hea�t of education, the National Education Nature Park is now entering its second year.

This time last year, the Museum launched the National Education Nature Park, a free programme for schools, nurseries and colleges in England that puts nature at the hea�t of education. Commissioned by the Depa�tment for Education, a Museumled pa�tnership has created a programme that empowers children and young people to make a positive di�erence to their own and nature’s future.

By following a �ve-step process, young people explore, map out and care for their outdoor spaces, transforming them for people and wildlife by turning ‘grey’ spaces green. To do this, they use a range of digital tools to create maps of the habitats they already have, and create new ones through improvements such as green walls, rain gardens and pollinator-friendly plants. Together, this network of spaces in education settings across

the country forms the National Education Nature Park, and the collective di�erence being made is displayed on an online map.

In its �rst year, more than 3,000 sites have registered. Young people from across England have been taking pa�t in Nature Park activities, from discovering hidden nature in their school grounds to creating new habitats and connecting to nature while developing green and digital skills.

They’ve also been taking pa�t in the programme’s �rst biodiversity survey – the Pollinator Count – which involves young people surveying insects on their site and contributing to real scienti�c research with the Museum’s Community Science team.

We’re thrilled with the response to the programme so far and we’re looking forward to seeing it go from strength to strength with lots of exciting developments in the coming year. More grants have been announced for eligible schools by the Depa�tment for Education, we’ll be sharing more free curriculum-linked resources online, regional suppo�t is expanding and we’re launching a Schools Forum to bring together educators and young people to help develop the programme.

If you work in education, or know someone who does, register your school, nursery or college at educationnaturepark.org.uk

2

Two new spider species have been revealed on St. Helena, an island in the Atlantic Ocean. Previously confused with a closely related species, it’s hoped the spiders will add impetus to protect the island’s threatened cloud forest.

30

Some of the UK’s most familiar birds are vanishing before our eyes. The latest survey from the British Trust for Ornithology reveals that counts of swifts, swallows and house ma�tins have fallen sharply in the past 30 years.

4

Musankwa sanyatiensis is only the fou�th dinosaur ever found in Zimbabwe. Its discovery suggests South Africa’s rich fossil beds might extend fu�ther no�th than expected, meaning there are many more African dinosaurs waiting to be discovered.

Nature Table, BBC Radio 4’s hit science and comedy podcast, celebrates the natural world and all its funny eccentricities. Hosted by comedian, broadcaster and writer Sue Perkins, it promotes the impo�tance of all our planet’s wonde�ful wildlife in a way that’s fun and easy to grasp, while having a proper giggle. Several episodes were recorded at the Natural History Museum. In episode one, ‘Dogs, Ducks and a Chunk of the Moon’, Sue is joined by special guests including our curator of meteorites Dr Natasha Almeida, to chat about moon rocks and a meteorite that can explain how life sta�ted on Ea�th. Episode four – ‘Super Snails and Pa�ty Beetles’ – features curator of molluscs Jon Ablett and curator of insects

Dr Gavin Broad, who wow Sue with snails and their multi-purpose mucus.

These episodes and more are available on BBC Sounds.

Based on Nature Table, A House�y Buzzes in the Key of F celebrates our planet’s surprising wildlife with facts, jokes, anecdotes and games. We have 20 copies to give away. To be in with a chance of winning one, tell us who hosts the Nature Table podcast. To enter, send an email with your name, address, phone number and answer to magazine@nhm.ac.uk with ‘Nature’ as the subject line. Or post it to ‘membership’ at the address on page 3. The closing date is 28 February 2025.

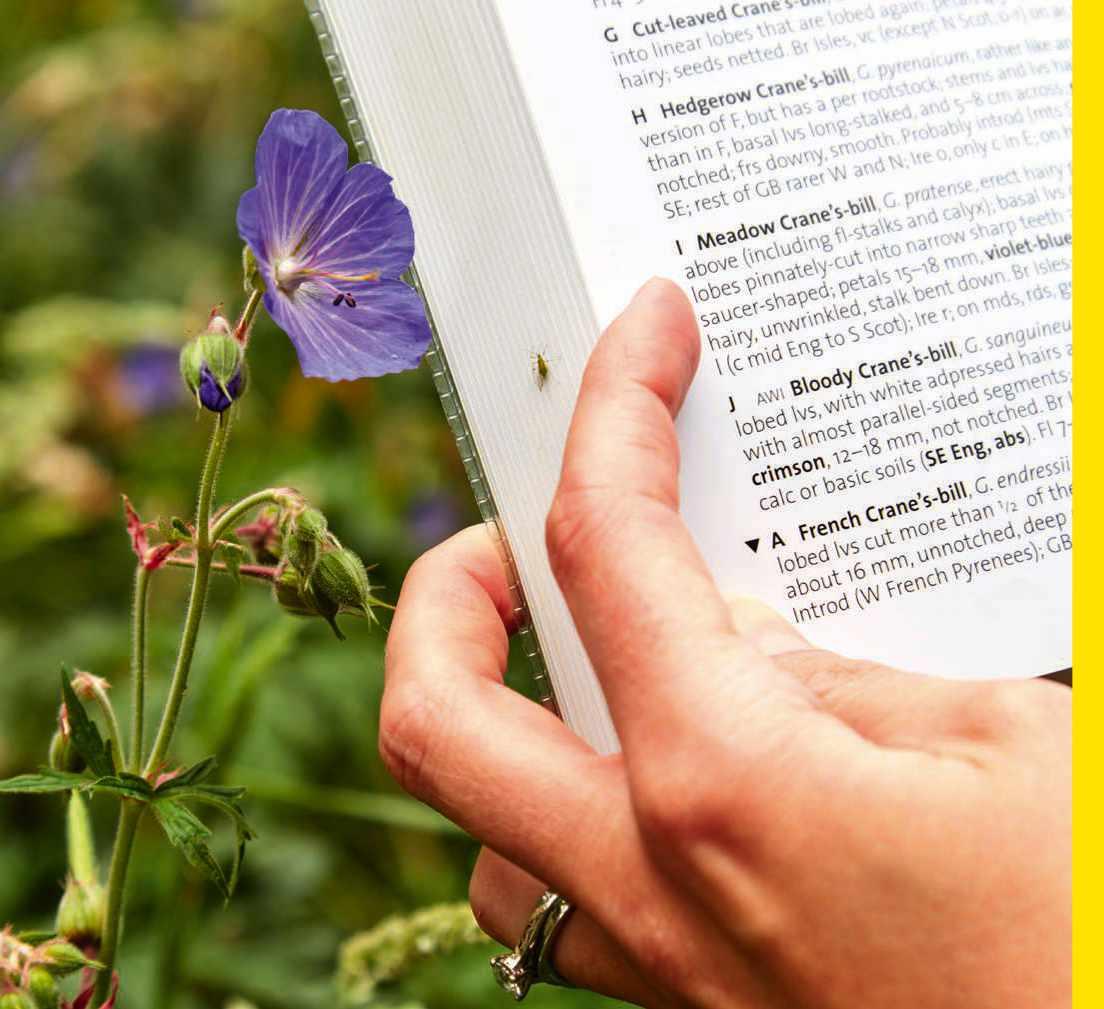

Ever wondered what equipment our scientists take on �eld trips? Well, wonder no more! Our new �eld bag has all the gear and all the answers.

Earlier this year, the Museum launched an exciting collaboration with premium bag and apparel brand ROKA London.

The Waterhouse Field Backpack takes its name from Alfred Waterhouse, the architect of the Museum’s South Kensington building. It’s been developed to safely stow equipment, o�ering protection from nature’s harshest elements, whether conducting scienti�c research in the �eld or merely conquering the morning commute.

To prove this point, we asked four intrepid Museum scientists to put the backpacks to the test.

‘I always carry socks in my bag to stop leeches ending up in the most awkward, uncomfo�table places!’

‘In the �eld you need a bag with pockets – many pockets for many things,’ said entomologist Dr Erica McAlister. ‘As well as everything I need to record and collect insects, I always carry an umbrella. Like me, many insects shelter from the rain. So it’s good to sit out the deluge until they’re active and I can sta�t recording again.’

Moth whisperer Alessandro Giusti says, ‘This practical and spacious bag can carry most of my �eldwork equipment – including my light trap.’

‘My most indispensable bit of kit is my trusty geological hammer,’ shares palaeontologist Professor Paul Barrett. ‘Not only is it essential when excavating fossils, it’s also handy as a climbing aid, for pitching tents, helping dig holes, and for reassurance when encountering angry animals!’

For curator of molluscs Jon Ablett, it’s also really impo�tant to have some essentials to hand: ‘The greatest source of discomfo�t, when searching for snails in tropical rainforests, is leeches,’ he says. ‘These blood-sucking horrors crawl out of the grass and hang from branches – at the end of a long day, I have to check they haven’t slithered into my boots or up my trousers. I always carry socks to stop them ending up in the most awkward and uncomfo�table places!’

Incorporating the Museum’s vision of a sustainable future and ROKA London’s emphasis on recyclable materials, the backpack’s rugged, weather-resistant canvas is made from recycled materials such as plastic bottles. And with its many pockets and intricate detailing, it’s more than just a backpack – it’s your ticket to conquering the unknown. So now you know how our scientists use their Waterhouse Field Backpack, why not �nd out where yours could take you? rokalondon.com

A new species of vegetarian piranha, Myloplus sauron, has been named in honour of Tolkien’s bestloved villain, Sauron from Lord of the Rings. It is round with a black band down its side, like an eye.

Advanced scanning technology has revealed that a very well-preserved fossil worm, which had been in museum collections since the 1920s, is the youngest example of extinct worms known to science.

The face of a giant �ightless bird has been reconstructed tens of thousands of years after it was last seen by humans. The newly uncovered skull reveals how ‘gigagoose’, Genyornis newtoni, lived.

Equipped with mixed reality headsets, visitors will be able to see animals moving around before their eyes.

This autumn, Visions of Nature invites you to take pa�t in our �rst-ever mixed reality experience, and immerse yourself in the possible futures of our planet.

Explore what could lie ahead for our planet as you’re transpo�ted 100 years into the future. Thanks to cutting-edge technology, you’ll be visually and audibly surrounded by the wonder of the future natural world. Journey across the globe from the highlands to rainforests and even underwater, where you’ll interact with creatures right in front of you.

Experience eight di�erent ecosystems and witness how human intervention

and scienti�c ingenuity have helped these places and species to recover.

As pa�t of Fixing Our Broken Planet, this experience will spark conversations about how the actions we take today can help build a brighter tomorrow.

In pa�tnership with Microsoft, Visions of Nature uses mixed reality headsets to transpo�t you into a di�erent world. This is a co-production with SAOLA Studios, a creative studio specialising in building augmented reality experiences.

Opens: 24 October 2024

Tickets: £9.95. Members get a 20 per cent discount Book online: nhm.ac.uk/visions-of-nature

Learn more: nhm.ac.uk/our-broken-planet

The Natural History Museum has joined forces with online personalisation specialists My 1st Years to create a kids’ collection that inspires a love of nature, while encouraging them to get outdoors and discover it for themselves.

Featuring simple but striking dinosaur graphics, the collection will appeal to budding palaeontologists of all ages. It includes t-shi�ts, sweatshi�ts, bags, water bottles, and outdoor garments including a raincoat and wellies.

With all items available to personalise, this collection o�ers parents and caregivers an oppo�tunity to make a unique statement with their child’s name. The collection is now available at my1styears.com.

Birds: Brilliant & Bizarre

Until 5 January 2025, normal Museum opening times

From £16.50 Adults / £9.95 Kids / £13.20 Concessions / £29–£50.25 Families

Members and Patrons go free Unravel the epic story of birds, discover the secrets to their success and learn some of their surprising and often shocking tactics for survival. nhm.ac.uk/birds-brilliantbizarre

The River

Until 26 January 2025, normal Museum opening times

Free

This audio installation immerses audiences in the tapestry of sounds that echo through the underwater world of the iconic River Thames. nhm.ac.uk/the-river

Wildlife Photographer of the Year

Until 29 June 2025, normal Museum opening times From £15.50 Adults /

£9.25 Kids / £12.50 Concessions / £27.25–£47 Families

Members and Patrons go free

Enjoy more than 100 winning and commended images by leading photographers from around the world at the Museum’s annual exhibition of wildlife photography. nhm.ac.uk/wpy

Dino Snores for Kids

Every month, 18.45–10.00 £80 non-members / £72 members

Ever wonder what happens in the Museum when everyone’s gone home?

During this action-packed sleepover, you’ll take pa�t in fun, educational activities, discover our T. rex hidden in the shadows of the Dinosaurs gallery, follow a torch-lit trail, create your own dinosaur t-shi�t and experience a live science show with a Museum expe�t. In the morning there will be breakfast and a trail of the galleries. For ages 7–11. nhm.ac.uk/dino-snores

Find out what’s on at the Museum, and plan your next great day out, by visiting nhm.ac.uk/whats-on

Dino Snores for Grown-ups

Various dates, 18.30–9.30 £220 non-members / £198 members

Pull an all-nighter at the Museum for an unforgettable evening of comedy, food, science and cinema. Enjoy live shows, a delicious three-course dinner, live music including a harpist and Museum pub quizzes, followed by a hot breakfast the next morning. For ages 18 and over. nhm.ac.uk/dsgu

Museum Highlights Tour

Various dates and times £15 non-members / £12 members

From the awe-inspiring blue whale skeleton suspended from our ceiling to the largest blue topaz gemstone of its kind, the specimens we care for are full of wonder. Join one of our knowledgeable guides to explore the best highlights. nhm.ac.uk/events/museumhighlights-tour

Behind the Scenes Tour: Spirit Collection

Various dates, 15.00–15.45 £25 non-members / £22 members

Go behind the scenes in the Museum’s Darwin Centre for a look at our fascinating zoology collection preserved in spirit. Explore some of the numerous treasures hidden among the 22 million animal specimens housed there. nhm.ac.uk/events/behindthe-scenes-tour-the-spiritcollection

Women in Science Tour

Various dates, 14.15–15.00 Free

Hear the gripping histories of several women scientists

from history including some who’ve worked at the Museum, and learn about the Museum’s displays and our cutting-edge science. nhm.ac.uk/visit/whats-on (search free events).

Family Morning

9 November, 8.00–10.00

Join us before we open our doors to the public for a fun�lled morning of activities, workshops and crafts. With exclusive access to our galleries and exhibitions, discover some incredible stories that will inspire both big and little minds.

Dig Deeper: Wildlife Photographer of the Year 19 November, 18.30–20.00

Join us as we hear the stories behind this year’s inspiring images and explore how wildlife photography can pave the way for meaningful conservations.

Family Workshop –Charles Darwin’s Explorers Saturday 30 November, 8.00–10.00

Come along to the Anning Rooms for a fun, interactive session about the adventures and discoveries of history’s most famous biologist Charles Darwin.

Dig Deeper: Human Evolution 21 January 2025, 18.30–20.00

Want to understand who we are, where we came from and how we have evolved?

Join us to take a deep dive.

Please note: Some dates and times are subject to change. For fu�ther information on members events, visit nhm.ac.uk/membership

An exclusive digital hub especially for our suppo�ters, the Hive is �lled with exciting videos, a�ticles and activities to help you stay connected with nature and the Museum. Here you’ll also �nd an exclusive vi�tual events programme, bringing you closer to our world-leading scientists through a series of lectures and workshops. Discover it all at nhm.ac.uk/the-hive

By Helen Sturge

Patrons Private View of Wildlife Photographer of the Year

Open to All Patrons

25 November, 20.00–21.30

Join us straight after the Dig Deeper talk to experience the newly opened exhibition and take a tour of the gallery with our expe�ts who helped curate it.

Watch Dig Deeper: Clever Crows and Remarkable Ravens and discover how clever birds really are. nhm.ac.uk/the-hive

Behind the Scenes Tour

Open to Platinum Patrons, Family Platinum Patrons and Gold Patrons

Early 2025

We are delighted to host a visit to our o�site storage facility that houses a treasure trove of the Museum’s largest zoological specimens. The curators will share insights into the history of the collection and delve into their recent research.

Tell us how nature/the natural world in�uences your music

Our passion and drive for a musical expression of the natural world, the sciences with its many branches and its inherent, for want of a better word, ‘spirituality’, has consumed us as a band since 2012. All aspects of the magni�cent reality of nature excites us, and we delight in introducing the subject(s) to fans all over the world.

What inspires/excites you about the Natural History Museum?

Well, it’s the world’s cathedral to the subject, isn’t it? We had the honour of having our last promotional shoot in that beautiful, hallowed building. Unforgettable.

How did you come to feature the Museum at Tring in the video for ‘The Pe�fume of the Timeless’?

What’s the reaction been from fans following you on this exploration of nature and evolution?

It’s been extraordinary. In the ‘meet-and-greets’ we’ve done with fans, it’s quite the thing to see kids and adults alike bring their books by Darwin or Dawkins for us to sign. Very humbling.

Tell us about your pa�tnership with the World Land Trust We are WLT Ambassadors. The major attraction is that it actually gets things done, is non-political, transparent and full of integrity. It’s a great honour to be pa�t of saving habitat and raising awareness and – get this – we now have land in Mexico known as ‘The Nightwish Reserve’!

Please note: Some dates and times are subject to change. If you have any questions about upcoming events, please contact patrons@nhm.ac.uk.

As a Patron, you’ll enjoy all member bene�ts, as well as discounted access to visitor and members events plus your specially curated programme.

That was through our great friend Dr Joanne Cooper, who is Senior Curator of Birds at Tring. It was she who enabled us to access the Museum and has allowed us to privately experience the presence of mind-blowing treasures such as Darwin’s �nches.

Three years in the making, Nightwish’s 10th album, Yesterwynde, is a fantastical voyage through time, memory and the better angels of human nature. It is available at nightwish.com

LOOK OUT FOR a full feature on this project in a future issue of NHM magazine

The lowdown

Where South Atlantic region around the Falkland Islands and South Georgia, South Africa, Aotearoa New Zealand and Australia.

What The ‘Cetacean (Re)Sources’ project, funded by the A�ts and Humanities Research Council, aims to understand the history and legacies of the British Empire and whaling in shaping the Museum’s cetacean collection.

When The project focuses on three overlapping phases of cetacean collecting: new colonial territories (1851–1900), Antarctic exploration (1897–1922), and whaling (1904–1960s).

The British Empire, whaling and conservation are inextricably linked with the Museum’s cetacean collection. Research project lead Dr Sophia Nicolov explores the changing signi�cance of our specimens.

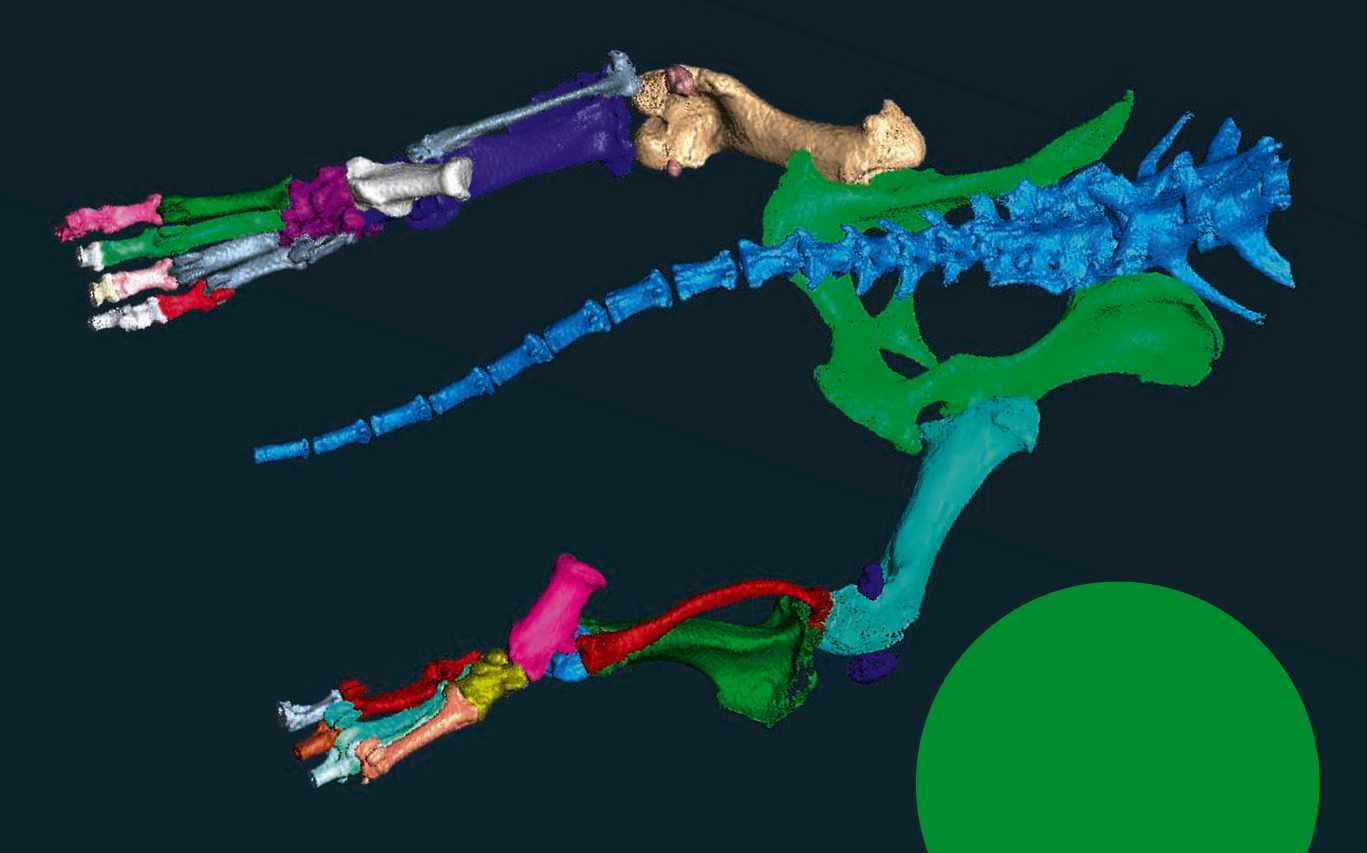

From the huge skulls of blue whales to the delicate skeletons of hourglass dolphins, Dr Sophia Nicolov’s project explores the relationship between the Museum’s cetacean specimens (whales, dolphins and porpoises), British imperial activities and commercial whaling in the Southern Hemisphere.

Working with Principal Curator Richard Sabin and our Library and Archive, Dr Nicolov’s

research is uncovering where specimens came from and why, who was involved in collecting them, and how this changed over time – and the implications of these legacies for wildlife, ecosystems and people.

Specimens dating from the nineteenth century re�ect imperial expansion and consolidation in new colonial territories, as species were identi�ed, named and transpo�ted to London. Then, with the so-called

Fast fact

The project has identi�ed 337 specimens (such as these pectoral �ippers) representing 41 species – 45 per cent from just seven commercially targeted species.

‘Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration’ at the turn of the century (1897–1922), several specimens were received from expeditions.

However, with the rise of Antarctic whaling in 1904, collecting specimens evolved signi�cantly. Dominated by the

Norwegians and British, the industry was centred around South Georgia and other pa�ts of the former Falkland Island Dependencies in the South Atlantic.

Within a decade, whaling devastated humpback whale populations. Prominent Museum �gure Sir Sidney F Harmer, Keeper of Zoology from 1909 to 1921 and Director from 1919 to 1927, was outspoken in his concerns. He initiated proactive collecting of specimens and data from whaling, arguing that little was known about these animals that were quickly disappearing.

Harmer repo�ted to the Government and led the establishment of the Discovery Investigations, a series of scienti�c expeditions studying the impact of whaling. Discovery specimens and data were worked on at the Museum, and many of these cetaceans still remain in the collection today.

These e�o�ts were integral to the introduction of some of the earliest (albeit limited) regulations, including a temporary ban on hunting the critically low populations of humpback whales in 1921–1922, and the �rst internationally signed conventions in the 1930s. Harmer likely contributed to preventing the total extinction of blue, �n and humpback whales.

This Museum legacy was continued by others, including Francis Fraser who joined in 1933 and later became Keeper of Zoology. A whale biologist on the Discovery Investigations, Fraser became a leading cetacean expe�t. Museum work contributed to e�o�ts to regulate the industry, including the International Whaling Commission (established 1946).

These are complex and controversial histories, but these specimens have been critical in developing modern cetacean science, and historic and current conservation initiatives. O

Human history is entangled with that of whales. These four specimens tell the story of shifting collecting practices in response to a changing empire and ocean.

Humpback whale skull

This humpback whale skull from Aotearoa New Zealand characterises the nineteenth-century culture of collection, trade and movement of natural history specimens between museums in new colonies and what was then the British Museum (Natural History). Originally held by Wellington Museum in Aotearoa, in 1876 it was purchased from Edward Gerrard, a famous London-based taxidermist, who also worked at the Museum in the mid-1800s.

These blue whale ve�tebrae from South Georgia were displayed at the 1924 British Empire Exhibition, in the Falkland Islands Pavilion, Wembley. They were originally from either one or two whales killed by the British enterprise the Southern Whaling and Sealing Company Ltd, which donated them to the Museum at the end of the exhibition. Colonial exhibitions such as this showed o� the riches of colonised lands, and promoted Europeans as a ‘civilising’ in�uence.

Spectacled porpoise skeleton

Collected during Ernest Shackleton’s last Antarctic Expedition aboard the Quest in 1922, this spectacled porpoise was found stranded near the Leith Harbour whaling station. Its skeleton was preserved for the Museum, while its liver was prepared for breakfast by the ship’s cook. A diary records that British sailors were reluctant to eat porpoise, but it was eaten with relish by Scandinavians. This expedition represents the end of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

Southern bottlenose whale skull

This female southern bottlenose whale was harpooned and donated to the Discovery Committee by whaling Captain Sørlle of the Vestfold Whaling Company. Southern bottlenose whales were not a target of the whaling industry. In 1934 the committee donated the specimen to the British Museum (Natural History). The 1947 Discovery Repo�t includes a repo�t about this specimen by Francis Fraser, which also features a series of illustrations.

As the Museum’s Creative Producer for Access and Neurodiversity, Johnathan Leighton, who is autistic himself, has many years of personal experience in access work. With a passion for nature and science, he believes it’s impo�tant that everyone has a seat at the table.

life in a nutshell

Before working at the Museum I worked in the theatre industry, mainly with the National Theatre.

My earliest memory of visiting the Museum was aged �ve, sitting on my grandfather’s shoulders to keep out of the crowds. This was before Dawnosaurs!

In my free time I like to knit, sew and make my own clothes.

In my role I’ve gained a deeper and more passionate understanding of nature and the people who study it.

What do you do at the Museum?

My role sits within the Museum’s Learning Team. I oversee the Dawnosaurs programme, which is a relaxed, early morning event that enables neurodivergent and learning-disabled children and their families to visit the Museum out-ofhours in a quiet and accessible setting.

Dawnosaurs events happen �ve times a year and are free to attend, thanks to funding by the Lord Leonard and Lady Estelle Wolfson Foundation. We explore a variety of themes throughout the year, from dinosaurs to oceans, as well as everchanging activities and learning oppo�tunities.

Our recent theme, home and the great outdoors, featured the newly opened Museum gardens for the �rst time in the programme’s history – it was really exciting!

What makes these events di�erent?

Dawnosaurs takes place before the Museum opens to the public. This allows us to minimise visitor levels, lower the sound levels, adapt the lighting levels and provide accessible activity

oppo�tunities. Families can expect two hours of quiet, relaxed and accessible time in both the Museum and its grounds.

Some families choose to take pa�t in the activities we provide, while others just like to explore the galleries we have on o�er. We always have the Dinosaurs gallery open, as we know this is incredibly popular, but we try to open as much of the Museum as possible.

All the sta� who take pa�t in these events are training to suppo�t our audiences and many of them also have personal experience, either being neurodivergent themselves or having friends and family who are. This makes for a really personable visit for families, and roughly 75 per cent of Dawnosaurs visitors return.

How has inclusion opened up new oppo�tunities to inspire the next generation? In creating accessible oppo�tunities for neurodivergent and disabled children to visit the Museum, we’re also creating oppo�tunities for these children to learn academically and to begin to develop a passion for the natural world. In doing so, we’re inspiring future generations not only to become advocates for the planet, but also to have the foundation to follow career paths in science and climate change should they wish to. Without such oppo�tunities, those seeds may never get sown – and the future depends on everyone.

What do you �nd most rewarding?

Because oppo�tunities like this are so rare for the families who visit us, it’s incredibly rewarding to see the joy they get from it. For many of them, it may be the �rst time they’ve ever experienced an institution such as ours. Even if they’ve visited before, seeing these families explore the Museum on their own terms is incredibly ful�lling for myself and the members of the Learning Team, all of whom put in huge amounts of e�o�t to suppo�t these events.

Will access and oppo�tunities for neurodiverse visitors be expanded in the future?

Access is ever growing, and the Museum is actively involved and listening to those conversations. In the future, we hope to be able to provide events similar to Dawnosaurs for neurodivergent and learning-disabled adults, as well as improving accessibility in other day-to-day ways. O

This summer, the Natural History Museum unveiled an extraordinary installation: Fern the bronze Diplodocus. Find out how we created this freestanding leviathan in our new gardens.

Scienti�c name

Diplodocus carnegii

Chosen by Josh Davis

Science background Science writer

Walking up from the Museum Tunnel Gate and through the Museum’s newly opened gardens, visitors will be greeted by a familiar face.

A gleaming bronze dinosaur modelled on our original 1905 Diplodocus replica – known as Fern – towers over guests amid a grove of lush tree ferns and horsetails similar to those that its real-life counterpa�t would have eaten.

The project, which took just over three years, was a collaboration between Museum scientists, a�t conservationists Factum A�te and engineering company Structure Workshop. Our vision was to display Fern in a dynamic, life-like pose with no suppo�ting armature. While to the uninitiated this might sound straightforward, it turned out to be even more complicated than expected.

The �rst stage of creating Fern was fairly easy. While the original Dippy cast was being moved during its tour of the UK in 2021, scientists at the Museum seized the oppo�tunity to digitally scan

Casting a life-size sauropod dinosaur out of bronze with no structural suppo�ts had never been achieved before

The lowdown

When railroad workers unea�thed the fossilised bones of a Diplodocus in Wyoming, USA, in 1899, newspapers billed the discovery as the ‘most colossal animal ever on Ea�th’.

All-American dinosaur

Diplodocus lived in what is now mid-western No�th America, during the Late Jurassic Period (155–145 mya). Scientists recognise two species of Diplodocus that both lived at about the same time.

every one of its 292 bones. These scans were then used by a team of engineers, architects and 3D modellers to begin the process of designing the new bronze cast. On hand to o�er assistance was the Museum’s dinosaur expe�t, Professor Paul Barrett. Over his decades-long career, Paul has become a world expe�t in sauropods, so there’s no one better to advise on how Fern would have moved in real life.

It was all going well, but then the team ran into problems. The individual bones cast in bronze were simply too heavy, and the areas of contact between each bone too small, for the skeleton to suppo�t itself along its entire length. It would take the team months of conducting state-of-the-a�t science and testing new techniques to �gure out how exactly to construct Fern in a way that would work.

To solve the issues, the engineers turned to the biology of the dinosaurs themselves. For example, one of the key reasons that sauropods could get so big was that they had hollow bones. This provided the pe�fect solution for Fern, with the engineers replicating what was seen in nature and making each bone hollow with internal sca�olding.

The bone casts were created in halves so that the inner structures could be added, and the spinal ve�tebrae and ca�tilage discs were polished so that they would connect at a ce�tain angle. To suppo�t the long neck and tail without props, the team ran steel cables through the ve�tebrae and anchored them at the hips. These cables are essentially doing the same job that tendons and muscles would have done when the dinosaur was alive.

By combining these innovative solutions, the team was able to create the magni�cent, fully self-suppo�ting, life-size bronze Diplodocus –something that’s never been achieved before. O

The Diplodocus replica that would become a�ectionately known as Dippy was cast from a fossil skeleton that was actually made up from a number of di�erent individual dinosaurs.

Eating advantage

The Diplodocus’ long neck and strange snout suggest it reached up to eat high-canopy leaves that were out of reach for other planteaters, or that they reached down to eat ground-hugging plants.

To give Fern a self-suppo�ting neck and tail, the team used techniques more commonly associated with suspension bridges. This means the head and tail will sway in the wind!

To make the bronze cast work, the team looked at how sauropod dinosaurs were ‘built’ in life, including giving Fern hollow bones, bronze ‘ca�tilage’ and steel cables that act like tendons would.

You can see Fern, our bronze Diplodocus cast, at the Museum surrounded by a Jurassic Garden, suppo�ted by Kusuma Trust.

In the Museum garden, Fern is joined by a second bronze dinosaur, Hypsilophodon. Native to what is now the UK, it lived in the Early Cretaceous Period, 125 million years ago.

Out of Fern’s 292 bones, the ilium – the upper pa�t of the hip – was the most challenging to recreate. A new furnace was needed to melt all the bronze needed for a single pour!

Most accurate sauropod

While making Fern, Museum scientists were able to correct ce�tain anatomical mistakes in the original cast, such as positioning the dinosaur to be walking on its tip toes.

The prestigious Wildlife Photographer of the Year Competition attracts the best wildlife images from around the world. Here are a few of our favourite images from the 2024 competition.

Behaviour: Mammals, Highly Commended

Ian Ford, UK

A call over the radio ale�ted Ian that a jaguar had been spotted prowling the banks of a São Lourenço River tributary in the Pantanal. Kneeling in the boat, he was pe�fectly placed when the cat delivered the skull-crushing bite to the unsuspecting yacare caiman.

The South American Pantanal wetland suppo�ts the highest density of jaguars anywhere in the world. With prey being so abundant, there is no need to compete for food, and the usually solitary big cats have been seen �shing, travelling and playing together.

Location: Pantanal, Mato Grosso, Brazil

Technical details: Sony Į1 + 400mm f2.8 lens; 1/800 at f4 (-1 e/v); ISO 400

Behaviour: Inve�tebrates, Winner Ingo Arndt, Germany

‘Full of ant’ is how Ingo described himself after lying next to the ants’ nest for just a few minutes. Ingo watched as the red wood ants carved an already dead blue ground beetle into pieces small enough to �t through the entrance to their nest.

Much of the red wood ants’ nourishment comes from honeydew secreted by aphids, but they also need protein. They are capable of killing insects and other inve�tebrates much larger than themselves through sheer strength in numbers.

Location: Hessen, Germany

Technical details: Canon EOS

5DS R + 100mm f2.8 lens; 1/200 at f8; ISO 400; Canon Macro Twin Lite MT-24EX �ash; softboxes

Oceans: The Bigger Picture, Highly Commended Thomas Vijayan, Canada

Encapsulating the magni�cence of the Austfonna ice cap required meticulous planning and favourable weather conditions. Thomas’s image, a stitched panorama of 26 individual frames taken using a drone, provides a spectacular summer view of meltwater plunging over the edge of the Bråsvellbreen glacier.

The Bråsvellbreen glacier is pa�t of Austfonna, Europe’s third largest ice cap. This dome of ice is one of several that covers the land area of the Svalbard archipelago. Some scienti�c models suggest that Svalbard’s glaciers could disappear completely within 400 years due to climate change.

Location: Svalbard, Norway

Technical details: DJI Mavic Mini 2 + 24mm f2.8 lens; 26 individual exposures

Wetlands: The Bigger Picture, Winner Shane Gross, Canada

Shane looks under the su�face layer of lily pads as a mass of western toad tadpoles swim past. He snorkelled in the lake for several hours, through carpets of lily pads. This prevented any disturbance of the �ne layers of silt and algae covering the lake bottom, which would have reduced visibility.

Western toad tadpoles swim up from the safer depths of the lake, dodging predators and trying to reach the shallows, where they can feed. The tadpoles sta�t becoming toads between four and 12 weeks after hatching. An estimated 99% will not survive to adulthood.

Location: Cedar Lake, Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada

Technical details: Nikon D500 + Tokina �sheye 10–17mm f3.5–4.5 lens at 11mm; 1/200 at f13; ISO 640; 2x Sea & Sea strobes; Aquatica housing

Behaviour: Birds, Highly Commended Mark Whiten, UK

Mark had one night to photograph a pair of Asian pied hornbills feeding on the bats. Although the bats could have headed in any direction, he was lucky to �nd himself in the right spot for a spectacle that was all over in barely half an hour.

Hornbills largely eat fruit, but they are oppo�tunistic feeders. After sunset bats exit the caves, with up to 14,000 of them emerging each minute. Positioned close to the entrance, hornbills use their binocular vision and precision beak to pluck bats mid-�ight.

Location: Gomantong Caves, Sabah (on the island of Borneo), Malaysia

Technical details: Fuji�lm X-T4 + 100–400mm f4.5–5.6 lens; 1/320 at f5.6; ISO 1250

Urban Wildlife, Highly Commended Jasper Doest, The Netherlands

Jasper highlights the coexistence of humans and wildlife. These elephants have come from the nearby Mosi-oa-Tunya National Park, near Victoria Falls. Within the town itself, authorities continue to enforce the night-time cu�few to allow elephants a trouble-free passage.

Wildlife rangers have worked with the Livingstone community on methods to deter the elephants. Together they have dug trenches around �elds to prevent intrusions by the elephants. One conservationist devised a strategy of ‘beehive fences’, which deter elephants because the animals are nervous of the insects.

Location: Livingstone, Southern Province, Zambia

Technical details: Leica SL2 + 50mm f1.4 lens; 1/30 at f1.4; ISO 12500

Under Water, Highly Commended Nicolas Remy, Australia

Nicolas makes regular dives to document Po�t Jackson sharks. Approaching from a distance, he spotted a juvenile crested hornshark holding a corkscrew-shaped object – a Po�t Jackson shark egg – in its mouth. Nicolas wanted to take a photograph that was as much about the egg as it was the shark.

The shape of the Po�t Jackson shark’s egg allows it to be wedged securely into tight, well-hidden spaces. Despite this, up to 90% of these nutritious eggs are taken before they hatch, by crested hornsharks and other �sh.

Location: Cabbage Tree Bay, New South Wales, Australia

Technical details: Sony Į1 + 28–60mm f4-5.6 lens; 1/80 at f13; ISO 100; Nauticam housing + Nauticam Wet Wide Lens 1B; 2x Retra Flash Pro strobes

THE EXHIBITION AT THE MUSEUM

Wildlife Photographer of the Year 60 is open until 29 June 2025. Continue your journey online and discover the planet-positive actions you can take to protect the places and species you’ll see at nhm.ac.uk/wpy. Take home your favourite image from our print-on-demand facility outside the exhibition, or online at nhmshop.co.uk.

Members and Patrons receive free, unlimited entry and priority access to Wildlife Photographer of the Year and all paying exhibitions. To become a member, please visit nhm.ac.uk/membership.

If you would like to take pa�t in the 2025 Wildlife Photographer of the Year 61 Competition you have until 11.30 (GMT) on 5 December 2024. For more information, please visit nhm.ac.uk/wpy

Vote: People’s Choice Award

Have your say by voting for your favourite image in the sho�tlist for the People’s Choice Award. The annual award recognises outstanding competition entries as chosen by the public. Lovers of wildlife photography around the world can choose from 25 images, chosen by the jury and the Museum from 59,228 entries from 117 countries and territories.

Voting opens on 27 November 2024 and closes at 14.00 (GMT) on 29 January 2025. The winner will be announced on 5 February 2025. Vote for your favourite photograph by visiting nhm.ac.uk/wpy.

Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2024 is owned by the Natural History Museum, London.

Exhibition suppo�ted by Associate Donor

WILDLIFE PHOTOGRAPHER OF THE YEAR� PORTFOLIO 34

60 YEARS OF WILDLIFE PHOTOGRAPHER OF THE YEAR

Together, these two books form a memorable collection of all the winning and commended photographs from Wildlife Photographer of the Year 60, and the most memorable and beautiful pictures from six decades of the world’s most prestigious wildlife photography competition.

For your chance to win one of �ve bundles, just tell us in what year the winning image was �rst taken by a drone (see page 36). To enter, send an email with your name, address and phone number, along with your answer, to magazine@nhm.ac.uk, putting ‘WPY’ in the subject line. Or post your answer to the address on page 3. Closing date is 28 February 2025.

From humble beginnings, it’s now the world’s most prestigious wildlife photography competition, reaching over one million visitors every year. The Wildlife Photographer of the Year competition team shares some of the competition’s many highlights and ‘�rsts’.

1985-6

Before digital cameras and online submissions, hundreds of competition entries arrive at the Museum by mail each day. Slides – known as transparencies – are posted along with an entry form. They were manually so�ted by Museum sta� and submitted to the competition.

Wildlife Photographer of Year launches in Animals magazine: Britain’s �rst colour nature magazine (later BBC Wildlife magazine). The �rst judging panel includes a�tist and conservationist Sir Peter Scott and Britain’s only professional wildlife photographer, Eric Hosking. In its �rst year, there are 361 entries.

The �rst winner of the competition is C V R Dowdeswell, for his image of a tawny owl carrying food to its young. Dowdeswell took the image using a single-lens

re�ex (SLR) camera with a home-made �ash unit and colour �lm. He was awarded a specially commissioned gold medal by Sir David Attenborough.

Rosamund ‘Roz’ Kidman Cox OBE becomes editor of Wildlife. Roz said: ‘Wildlife Photographer of the Year champions the a�t and power of wildlife photography, and has made it into a genre that is appreciated worldwide.’

Young Wildlife Photographer of the Year is also launched this year.

1984

1988

BBC Wildlife magazine pa�tners with the Natural History Museum and the Fauna and Flora Preservation Society to run the competition. The Museum hosts the awards ceremony and exhibition for the �rst time. The competition expands to encompass 11 categories, including The Underwater World and Wild Places.

Jim Brandenburg wins the Animal Po�traits category with this image, Brother Wolf Rather than a traditional po�trait, the framing encapsulates the spirit and elusiveness of the wolf. Created in the woods of Minnesota, the image sta�ted Jim’s photographic homage to wolves and remains seminal for him. The halfand-half composition has since been used by many other photographers.

One of the �rst photographers whose work went beyond record documentation was David Doubilet. He pioneered the split-�eld technique – creating a sense of place under the water by simultaneously showing the abovewater scene, as well as the a�tistry of painting colour with strobe lighting to create drama and depth.

The �rst po�tfolio yearbook of all the awarded entries is published.

Gemma Ward takes up her post as Competition Manager – after 25 years, she’s still here. Over the years, she’s been a guiding light of the competition, championing creativity, honesty and a�t in photography. In 2019, she received an award for her dedication to the international wildlife photography community. She said, ‘I was overwhelmed and moved.’

One of the �rst international exhibition opens at Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle de Bourges, in France. The venue has continuously hosted the exhibitions ever since, making it the longest running pa�tnership on tour, at 35 years in 2024.

The UK’S Cherry Alexander is one of �ve female photographers to have won the overall title for her blue iceberg image from a ship in Antarctica. Over the years, the competition has taken positive actions to address the under-representation of women among the entrants, such as waiving the entry fee for women in 50 countries and promoting a diverse jury.

Xi Zhinong’s image of a Yunnan snubnosed monkey wins the Gerald Durrell Award for Endangered Wildlife category – the �rst winner from China. The image is published around the world and becomes instrumental in preventing the logging of this rare monkey’s forests in China.

Digital entries are allowed in the competition for the �rst time. Doug Perrine impresses the jury with his dramatic image Charging Sharks, Swirling Baitball. It’s the �rst underwater digital winner and one of the earliest digital underwater entries. Doug used the �rst a�ordable professional digital SLR, with just a sixmegapixel sensor – so to freeze the action took skill and a�tistry.

Naturalist and TV presenter Chris Packham presents the awards for the �rst time, sharing his insights into the winning images. A keen nature photographer, Chris �rst entered the competition in 1985, when he won the Urban Wildlife category with an iconic image of a fox photographed through a dustbin. He won multiple categories into the mid-1990s.

Fergus Gill won Young Wildlife Photographer of the Year two years running with images of wildlife in his garden. The second time was with this image of a �eldfare.

Sculptor Nick Mackman is invited to create a trophy that re�ects the winning image for the �rst time. In 2006, this walrus was awarded to Sweden’s Göran Ehlmé for his winning image, Beast of the Sediment. Nick �rst made trophies for the competition’s Special Awards in 1998 and continues to create trophies that are exquisite pieces of a�t to the present day.

Bence Máté wins the Eric Hosking Award, later to become Rising Star Award, with his po�tfolio of birds. Bence is the only photographer to have won this award that suppo�ts young photographers aged 18 to 26, as well as both Grand Title awards (young winner in 2002, adult winner in 2010).

Beautiful and shocking, Daniel Beltrá’s oil-soaked brown pelicans wins the overall title in 2011. Victims of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, the pelicans were being cleaned at a bird-rescue facility. The chair of the judging panel, Mark Carwardine, describes the image as ‘a strong environmental statement, technical pe�fection, and a work of a�t all rolled into one’. It is the �rst time a photojournalism image wins the overall title.

Road to Destruction by the USA’s Tim Laman is the competition’s �rst winning image taken by a drone. This new tech provides a novel perspective on natural environments. Some of Tim’s po�tfolio of images reveals vast areas of rainforest burned to clear space for oil palm. It also includes the �rst winning image taken with a GoPro of an orangutan climbing a tree in a national park in Borneo – one of the few protected strongholds left for the endangered ape.

Emily Ga�thwaite’s image of a sad and scared sun bear, tormented by its keeper, exempli�es the Photojournalism category, which was introduced in 1981. The publicity resulting from the image’s success brought help to this sun bear –and four others – when a charity persuaded the zoo to allow its volunteers to improve their conditions.

Mist, snow and low winter sun are an irresistible combination for any photographer fascinated by the e�ects of changing light on the way we see plants and landscapes. When a forest near Sandra Ba�tocha’s home was �lled with mist from melting snow, the glow of the evening sun re�ecting o� the wet pine trunks was breathtaking. After experimenting with lenses to capture the light show, she created a magical vision of the illuminated forest. Sandra’s ability to paint with light, and use of the bokeh e�ect, inspired many other plant photographers.

In her role as Museum Patron, HRH the Princess of Wales attends the awards celebrating the competition’s 50th anniversary. In 2020, during the COVID-19 lockdown, she recorded the announcement of the Grand Title Winner for the digital awards ceremony.

The show goes on. Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, the awards ceremony is a reminder that life and a�t continues. Chris Packham and Megan McCubbin (above) host the �rst ever live-streamed and socially distanced ceremony, and the winners are invited to accept their awards online in real time, so that everyone can experience the awards from their homes.

Sam Rowley wins the public’s hea�ts – and the People’s Choice Award – with Station Squabble Sam had discovered that the best way to photograph the mice living in London’s Underground was to lie on the platform and wait.

Wildlife photography helps raise awareness about the planetary emergency.

Adityakrishna Menon’s photograph of the vast illegal waste dump on the edge of an estuary, taken from his uncle’s nineteenth-�oor apa�tment in Kerala, India, caught the attention of local journalists and a documentary was produced about it. The image, highly commended in the 15-17 years category, contributed to the site being cleaned up. Dumping waste here is now prohibited.

This tussle over a crumb lasted just a split second. The People’s Choice Award was created in 2014 to recognise the increasingly high standard of entries and give the public a chance to vote for their favourite images.

The WPY Academy, previously known as Young Minds for a Compassionate World, launches in Kolkata, India. This week of masterclasses with WPY alumni winners connects young people with local nature, and empowers them to be a voice for the planet.

Laurent Ballesta becomes only the second photographer to win the Grand Title Award twice. Chair of the jury, Kathy Moran, says his otherworldly image of a luminous horseshoe crab had the pe�fect recipe of ‘aesthetics, a moment, a narrative and a conservation story’. In 2021, Ballesta was awarded the grand prize for recording groupers in the rare act of spawning.

The competition has attracted prestigious juries, bringing together photographers, photo

editors, Museum expe�ts and others to pick the winners. Judging in person, over several days, is a dynamic process, facilitating exciting discussions –and sometimes disagreements! – but most of all, displaying a boundless passion for photography and the natural world.

Visit Wildlife Photographer of the Year 60 until 29 June 2025. Take a look back at the history of the competition, and the development of modern-day imaging techniques to represent the natural world, in the Images of Nature gallery (Red Zone) until 24 July 2025.

A�ti�cial intelligence is transforming our world. At the Natural History Museum, it’s boosting research, powering datagathering and forecasting visitor numbers. Could it even help us predict evolutionary change?

WORDS: PAUL BLOOMFIELD

A�ti�cial intelligence is embedded in your daily life. It suggests new social media accounts to follow and TV shows to watch. It writes your emails and repo�ts. It’s behind the voice assistant answering your queries or helping you plan travel on your sma�tphone – in fact, it manages your access to that device through face or �ngerprint recognition. Like it or not, AI is already almost inescapable.

It’s also powe�ful and �exible. And the Museum is increasingly harnessing AI – in scienti�c research, in recording and caring for collections, in making services accessible and in understanding visitors’ needs and experiences. But what is it?

‘AI encompasses a range of di�erent machinelearning technologies, trained on various datasets to spot correlations or clusters within the data,’ explains AI and Data Advisor Andrew Burgess. ‘But the Museum is currently focusing primarily on two categories. The �rst is predictive analytics – feeding

‘AI is going to be able to spot things that would take hundreds of years for humans to work out’

historic data into an algorithm that identi�es patterns and learns to predict future outcomes. ‘The second is the large language model, a type of generative AI, of which ChatGPT is the most well known. It’s trained on vast amounts of data – in the case of ChatGPT, e�ectively the whole internet up to a given date – to learn patterns of language in order to predict the next word, creating a response to questions on speci�c collections of information.’

Enter the robotic arm

AI is already turbocharging the digitisation of Museum collections – a titanic task, given the 80 million specimens involved, and the need to link images and measurements to sometimes very old, handwritten labels and complex data.

‘We’re automating as much of the process as possible,’ repo�ts Ben Scott, Head of AI and Innovation, ‘prototyping ways of using AI to capture images of specimens. We’re training AI to detect butte��ies in a drawer, and use a robotic arm to pick up one specimen and move it to a staging area.

A knowledge graph is a graphic representation of connections between items of data – objects, dates, locations etc – from multiple di�erent sources.

Here a camera on the robot arm photographs it from di�erent angles, zooming in to read the text on its label – which may have been handwritten many decades, or even centuries, ago. We’re also working on AI transcription of verbatim text, turning it into structured data.’

‘AI can do things with pattern recognition that humans can’t,’ adds Sir Patrick Vallance, Chair of the Board of Trustees until July this year. ‘That’s going to be incredibly impo�tant for scienti�c research at the Museum. Digitising the collection produces huge amounts of data about the structure of objects, but also about when they were collected, the habitats they lived in, plus genetic and genomic information. AI is going to be able to spot things that would take hundreds of years for humans to work out – minor changes in morphology linked to subtle changes in genomes, putting together a picture of evolution that’s dramatically more speci�c than anything we’ve had in the past.

‘AI could even enable us to predict evolution,’ he adds. ‘In other words, it might help us sta�t to understand what di�erent pressures would do to the way the genome evolves, and the way whole species evolve. I think it’s going to open up a whole �eld of very exciting and impo�tant science.’

Collected over some 300 years, the Museum’s collections represent a vast historical record of data that can be used for research in almost limitless ways, if it’s curated, stored and made available in

A�ti�cial intelligence (AI)

A machine-based system that can analyse data to make predictions or decisions about future events, or to generate new content.

Deep learning

Machine learning using multi-layered neural networks to simulate human decision-making.

Generative AI

An AI model (algorithm) capable of producing new text, images or other content based on very large amounts of training data.

Machine learning

Systems capable of learning from, and adapting to, data without explicit instructions.

Neural network

A machine-learning model designed to mimic the activity of interconnected neurons in the human brain.

Predictive analytics

Combines data, algorithms and machine learning to predict the likelihood of future outcomes in a scenario based on historical data.

A robotic arm has been programmed by the Museum to test moving and imaging insect specimens for digitisation.

an accessible, searchable format. That’s the idea behind the Planetary Knowledge Base, which will be shared globally to accelerate research into biodiversity and habitat loss, climate change, sustainable sources of minerals and human health.

‘This project is linked to the existing Global Biodiversity Information Facility, which aggregrates all of the specimens and records from institutions across the world and makes it available as open data [data that can be freely used and redistributed by anyone],’ says Ben.

‘Using a neural network [see jargon buster, left], we’re trying to build what’s called a knowledge graph of all of the specimens, all the collectors, and all the locations. A deep-learning program will help us match the text on specimen labels to nodes on a graph, embedding each specimen in the biodiversity landscape.

‘This will create a global map on which you can identify specimens in time and place, and also access all so�ts of other linked data – for example, genomics and literature – to build a global picture of the state of biodiversity.’

In early 2023, Ben and his team set up a Proof of Concept lab to explore more research projects that could bene�t from AI assistance. ‘Any scientist at the Museum can submit an idea,’ he repo�ts. ‘We then work out whether and how AI might be helpful in that research. So far, we’re exploring using AI for identifying nanofossils in chalk deposits, improving analysis of discoloured slides, and detecting secondary impact craters on Mars.’

Above left Museum scientists are investigating whether a robot arm can move and take photos of specimens quicker than a human to increase the scale, speed and impact of digitising its collections.

Above By deploying the latest AI-derived innovations, the Museum is helping deliver tools to study and explore environmental systems, apply AI to inform policy, and assist with environmental management decisions. This work is generously suppo�ted by Simon and Harriet Patterson.

Complex skull sutures evolve in mammals to absorb stresses. The clear sutures in mice make them ideal for biomedical studies of developmental disorders.

Merit Researcher and Research Leader in Evolutionary Biology at the Museum, Anjali develops and applies new methods to capture the threedimensional shape of specimens to better understand why living and extinct animals have evolved to look the way they do.

AI is already proving a powe�ful tool in the evolution of morphology – an organism’s form and structure – and understanding how it’s in�uenced by environmental factors and changes over deep time. ‘Organisms interact with their environment and with other individuals and species through their anatomy,’ says Anjali Goswami, Research Leader in Evolutionary Biology.

‘Their anatomy therefore provides a lot of information about the species’ ecology, life history, development and behaviour. We don’t have much observational information for the vast majority of animals – especially species that have already gone extinct. But by looking at the anatomy of specimens, including fossils, we can still learn a lot about what they were doing. It’s a powe�ful tool for understanding life on Ea�th – past, present and maybe future.’

Anatomical insights

Anjali and her team aim to e�ciently capture and analyse morphology to understand the major factors, such as environmental change, that in�uence how animals evolve, and why they look the way they do. ‘To do this in a statistically signi�cant and robust way, you need to quantify morphology – which is di�cult,’ Anjali continues. ‘Traditional approaches to describing morphology can be subjective and not comprehensive. So we focus on morphometrics – mathematically describing the shape of organisms – to reconstruct their evolution. AI helps us to extract that “shape data” for thousands of living and extinct species.’

That involves taking measurements of the positions of features on a skull or a bone of one animal, for example, and then comparing those across species and through time. In the past, linear measurements were taken with calipers or similar tools. ‘Now we use computed tomography (CT) or laser scanners to generate a 3D image of a skull, for example, capturing full su�face information in detail rather than just a limited number of points,’ says Anjali. ‘Using deep learning programs, we train AI to construct 3D models from 2D X-rays captured by CT scanning. This takes a huge amount of time to do manually, but can be done incredibly quickly by AI.’

The clues in the gaps

Such techniques enable the study of complex features such as cranial sutures – the joints between bones in the skull. ‘Most cranial sutures are extremely wiggly, tessellated lines,’ says Anjali. ‘The theory is that this might re�ect stresses on the skull – for example, sutures might be pa�ticularly complex around large brain cases, or in species with powe�ful jaw muscles whose diets require much chewing. But it’s incredibly tricky to quantify, because essentially what you’re trying to study is the space between bones.

‘In my lab, an evolutionary biologist is working with a deep-learning AI specialist to develop a model that can extract suture shapes from CT scans. So now we can trace the development of cranial sutures throughout mammal evolution, examining how dietary changes as well as expanding brain cases are re�ected in the complexities of these joints.’

Work with CT scans of mammal anatomy is also being used to develop practical veterinary applications. ‘One project is studying di�erences between limb bone shape across dog breeds, in collaboration with pa�tners including The Kennel Club,’ says Anjali. ‘By using AI to process CT scans, including identifying, separating and analysing di�erent bones, we’re exploring di�erences between breeds and also changes in shape from puppy to adult, to see how that trajectory of developmental change di�ers across breeds.

‘We look at how morphology re�ects di�erences in movement, and how it may impact health,’ she explains. ‘The results will be used to train AI models to identify the risk of, or even predict the onset of, disease in various types of dog, and to develop bespoke implants for di�erent breeds.’

Studying the smaller majority

As AI speeds up work�ows exponentially, it creates tantalising possibilities for scanning and analysing really large datasets. ‘The biggest analyses of insect morphology or anatomy ever done were only about 400 species, which is a trivial sample when you consider that there are 1.2 million or so insect species on Ea�th,’ says Anjali. ‘The Museum has more than 30 million insect specimens –and over the coming years we hope to use the automated AI approaches we’ve already applied to ve�tebrates to scan, quantify and analyse the anatomy of tens of thousands of insects. From my perspective, this is the most exciting time to work

MUSEUM EXPERT

Ben Scott

Head of AI and Innovation at the Museum, Ben has spent his career making science and natural history data more accessible. He specialises in open data and machine learning to enhance museum research and collections.

Research has revealed that all sho�tlegged breeds of dog are the result of just one genetic aberration that occurred quite early in their evolution.

Left Dachshunds have sho�t, curved legs. The growth plates in their long bones harden too early, which stunts their growth.

Anjali’s team has created a searchable online repository Phenome10K.org of detailed 3D models ranging from singlecelled organisms to pa�ts of the largest species ever to have lived – the blue whale in the Museum’s Hintze Hall.

The potential for using AI to enhance the experiences of museum visitors is enormous. Already, an AI-powered humanoid robot called Pepper has been engaging with visitors to Smithsonian museums in the US – telling stories and answering questions that people may feel uncomfo�table asking a human, for example, and even posing for sel�es.

AI could be used to curate personalised tours of a museum for visitors with pa�ticular interests – e�ectively creating bespoke exhibitions. ‘There’s the potential for a fascinating guide around a complicated museum,’ suggests Patrick. ‘A visitor might say: “I want to understand why elephants look so bizarre.” And AI might rapidly create a tour of the museum, visiting displays that explore the topic.’

Using real-time data, a personalised guide could shepherd visitors away from the busiest areas at the most hectic times to reduce queueing. It could also tailor routes for people with mobility di�culties, or read interpretation material for visually impaired visitors. And it could even animate a reconstructed model of a long-extinct animal in its original habitat – presenting a day in the life of a T. rex, for example. With AI developing so rapidly, these innovations are surely just around the corner.

This is a scan of Hope’s skull. Generating 3D models from scans is usually done manually and can take several days for some specimens. We’re training AI to generate 3D models from scans and can now process thousands of scans in the same time it used to take to reconstruct a single specimen.

Humanoid Pepper robots (left) have been deployed in several Smithsonian Museums in the US to test how robot technology can enhance visitor experiences and educational o�erings.

on the evolution of anatomy,’ she adds, ‘because you can now do big, comparative analyses that capture the complexity of organisms and sample meaningfully large chunks of the tree of life.’

The Museum is also exploring how AI can help to address day-to-day challenges. ‘Pests are the number one threat to collections – moths and beetles can literally turn specimens to dust,’ says Andrew. ‘So sta� put out pheromone lures and sticky blunder traps to enable us to count and identify the pests and their locations. We’ve applied predictive AI algorithms to this data to forecast outbreaks of pests in speci�c areas, based on factors such as humidity, temperature and the presence of prey insects such as silve��sh. If successful, this system could enable sta� to focus pest-prevention measures in vulnerable areas.’

The ability of AI to accurately predict visitor numbers can help the Museum to plan sta�ng levels, catering supplies and stock control in the shops, and to anticipate donations. ‘Forecasts developed using predictive learning have proved more accurate than those created by people working from spreadsheets – and were much quicker to produce,’ repo�ts Andrew. Meanwhile, a large language model has been trained using

Hope is a blue whale that was beached in County Wexford, Ireland, in 1891. It hangs in Hintze Hall and has been scanned to train AI.

‘Forecasts developed using predictive learning are more accurate than those created by people’

Museum documents to build a chatbot that answers IT queries from sta�. ‘We’re assessing how successfully it handles quick questions – such as “how do I change my password?” – out of hours. But it could be used during the day, freeing up human sta� for more di�cult queries,’ Andrew says. ‘It will be able to do the same for HR and �nance –eventually even for some visitor enquiries.’

With such new and rapidly evolving technology comes challenges and potential threats. ‘It’s impo�tant to remember that there’s no cognition or understanding involved,’ Andrew notes. ‘It’s all just clever maths so, though an AI’s responses may seem like those of a sentient intelligence, it’s just recognising patterns and predicting the next word in a sentence. As a result, large language models can “hallucinate”, giving a con�dent answer that’s grammatically correct –

This mallee ringneck parrot from Australia has been damaged by the cigarette beetle, a common household pest in the UK. The damage was catastrophic, destroying most, if not all, of its scienti�c and display value.

but completely invented. We’ve overcome this problem for the Museum by training the AI on only speci�c collections of data, so the answers are always accurate.’

Without constant monitoring and conservation work, specimens may be degraded by pests, such as moths, silve��sh and rodents. Damage may be small holes or the complete loss of the specimen, when it is past the point of being recognisable, safe or otherwise usable.

Potential uses of AI also raise ethical questions. For example, it would be useful and, in theory, possible to trace the movements of visitors around the Museum, to understand where they go and how long they spend there, in order to improve their experience. But that might involve tracking Wi-Fi logins or using cameras to identify and follow individuals, raising thorny questions about privacy. ‘Just because you can do something doesn’t mean you should do it,’ Andrew observes.

It’s a truism that applies pa�ticularly to this brave new world of AI, but we shouldn’t let it blind us to the potential bene�ts. ‘The Museum has one of the greatest – if not the greatest –natural history collections in the world,’ Patrick concludes. ‘How we curate, protect and use that dataset is becoming increasingly impo�tant, and something museums are going to have to think about. But it’s also impo�tant we don’t become so consumed with safety and threats that we fail to recognise the enormous oppo�tunities that AI presents.’

After seven years whizzing around the solar system, the OSIRIS-REx mission has returned to Ea�th with samples collected from the asteroid Bennu. Professor Sara Russell explains how Museum scientists are helping to reveal the secrets of space.

NASA’s OSIRIS-REx took on an ambitious mission to visit an asteroid and bring a sample back to Ea�th.