SALIERI: WAS HE MOZART’S MURDERER?

The myths surrounding the overshadowed Italian opera composer

How he chose the Amadeus music

40 YEARS OF AMADEUS

We tell the story of the greatest classical music film ever made

Marian Anderson

The singer and civil rights symbol 7 must-hear horn works

As chosen by Ben Goldscheider Backstage tours

Secrets of the great concert venues Th h

Also in this issue… Meet Karl Jenkins, choral music’s most popular composer

The best recordings of Mendelssohn’s radiant First Piano Trio

How Thomas Adès’s musical journey began with a wooden spoon…

100 reviews by the world’s finest critics

Recordings & books – see p78

NEVILLE MARRINER

Full April listings inside See p108

The full score

The BBC Music Magazine team’s current favourites...

Charlotte Smith Editor

The announcement of this year’s Oscar nominations was the perfect opportunity to revisit Ludwig Göransson’s score for Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer. Though an excellent film, my one complaint was with its sound mixing.

In each scene, the music’s volume gradually increases so that important dialogue is lost in an epic crescendo – a pattern followed with infuriating consistency throughout. Outside this context, Göransson’s minimalist music is far more subtle and sophisticated.

Jeremy Pound Deputy editor

Not generally the biggest fan of music that spends a lot of time going nowhere, I found myself unexpectedly entranced by Max Richter ’s On the Nature of Daylight while listening idly to Radio 3. Performed by organist Anna Lapwood and the Choir of Pembroke College, Cambridge, its slow-moving, repeated chords and floating voices were the perfect match for looking out into a rain-soaked evening while somehow offering a sense of contemplative calm.

Steve Wright Acting reviews editor

I’ve been finding great peace and serenity in Edmund Rubbra’s symphonies. Rubbra tended to prioritise the melodic line when composing, meaning that many of his themes are very songlike. There’s also a calm solemnity to much of his music – like Bruckner, he was a deeply spiritual man, and his 11 symphonies often remind me of Bruckner’s nine, with their patient symphonic rigour and quiet awe at the universe.

Freya Parr Content producer

When the world is feeling a little bleak (and in a UK winter, when is it not?), I turn to Ichiko Aoba’s live album with 12 Ensemble, recorded at Milton Court. Dawn in the Adan is a favourite, with Aoba’s ethereal voice and Japanese folk lyrics shimmering above her plucked guitar and 12 Ensemble’s delicate strings. It’s a recording that takes you by the hand and doesn’t let go.

REWIND

Great artists talk about their past recordings

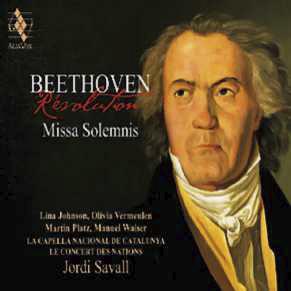

This month: JORDI SAVALL Conductor

MY FINEST MOMENT

Beethoven Missa Solemnis

La Capella Nacional de Catalunya; Le Concert des Nations/Jordi Savall et al Alia Vox AVSA9956 (2023)

This was something I’d been preparing for many years, because it’s a really difficult project, one of the most complex and spiritual of the vocal and orchestral works. I had decided on something very simple first, which was to be well prepared, but also to take the time needed to go deep into the central aspects of the performance. I decided to take the same approach

as I had with the complete Beethoven symphonies, which was to do six days of intensive work in one month, send everybody home and then do another six days of intensive work. This is the only way I can imagine to reach the work’s summit; you have time to experiment, time to discover. There are things that you imagine at home when you’re studying the score, but when you are working with the singers it becomes evident that things have to be done in a certain way. And you can only discover this if you have time; if you are in a hurry and you say, ‘We have to finish this in the next half hour,’ it’s impossible.

I’ve heard many nice performances of the Missa Solemnis with good ensembles,

18 BBC MUSIC MAGAZINE

Voice of comfort: Japanese folk singer Ichiko Aoba

Music to my ears GETTY, ROBERT WORKMAN

but the solo parts are often not properly aligned with the character of the work. I have a really good ensemble of solo singers, which makes me happy about this performance.

MY FONDEST MEMORY

Beethoven Symphony No. 9

La Capella Nacional de Catalunya; Le Concert des Nations/Jordi Savall et al Alia Vox AVSA9946 (2022)

financial support from all the partners – when the French president helps a project it’s much easier to get other people to join! The only problem was Covid, and that made things much more difficult.

I was finishing the Ninth Symphony and preparing to record it in Poland, but during the rehearsal some singers became sick, and then two days later someone else was sick, so we had to cancel the sessions.

The following year we recorded it in Cardona, Catalonia. We had no contact with the world, and we rehearsed and recorded in very beautiful conditions –no travel, no concerts. I think this was one of the most beautiful experiences of my life, because we took the time to look at the manuscripts, to work on the bowing, phrasing, tempos and dynamics, and I think we presented a different way to play this music.

I’D LIKE ANOTHER GO AT…

JS Bach St Matthew Passion

La Capella Nacional de Catalunya; Le Concert des Nations/Jordi Savall et al Alia Vox (Unreleased)

MyHero

My first Beethoven recording (the ‘Eroica’ Symphony in 1994) was possible because I had made the soundtrack for the film Tous les matins du monde in 1991. I received a royalty for sales of the CDs, and from 1991-93 I received a lot of money every month – it sold more than two million copies! But in approaching the later complete symphonies project, I asked President Macron if he would help; he was very interested and he helped me with the first subvention. With this I obtained

I recorded the St Matthew Passion some years ago. We recorded in the Palau de la Música, which is a very beautiful hall in Barcelona from the time of the Art Nouveau; however, the acoustic is not ideal for a religious work, as it’s too dry. We made the recording and I listened to it, but I was not happy with the sound and I was not 100 per cent happy with some of the singers’ performances. So I decided not to release it. It’s a work that already exists in so many versions, and if you take it on, you have to do it in the most beautiful way. The circumstances back then were not ideal and there was no time to do corrections. This is the difficulty of live performing; it has to be really good, and so I prefer to wait.

I would perhaps like to do it again next season or in 2026, and I think I would record it in Cardona, where we recorded the Beethoven. It’s a Germanic church, but it’s very special because it’s all stone – but stone which is not polished. The sound is incredible: it’s rich, deep and has radical harmonics, but it’s clear. It’s a very special acoustic.

Jordi Savall’s latest album ‘Vivaldi at the Ospedale della Pietà’ is released on Alia Vox in April.

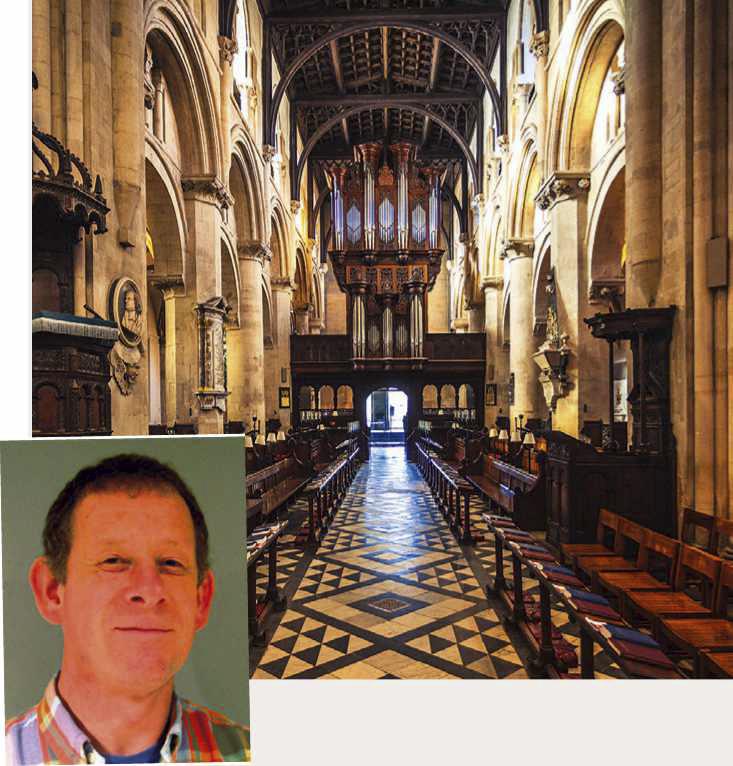

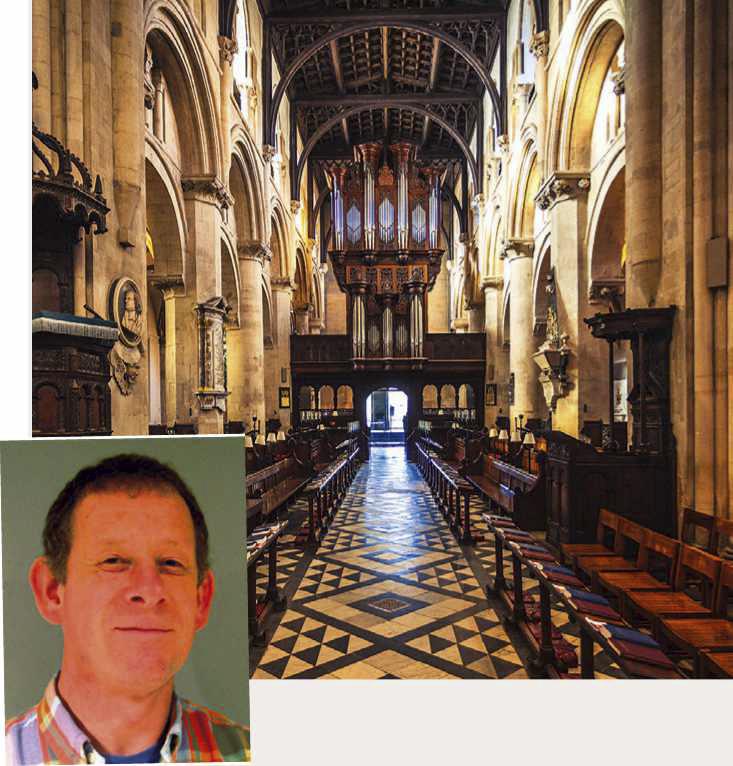

Like many musicians, I had a strong sense that I wanted to be a performer while growing up. I sang at school and in my local church choir and having started on piano, as soon as my feet could touch the pedals, the organ beckoned. At 18, I won an organ scholarship to Christ Church, Oxford.

If I’m honest, I’d given a lot more thought to performing than I had to the degree, so it was with great trepidation that I approached the first seminar of term. I needn’t have worried as I was about to meet one of the kindest and most profound influences on my musical life.

Dr John Milsom welcomed us undergraduates as equals and, from the moment he spoke, my view of music shifted. He asked questions I’m still striving to answer: ‘Where is the music? On the page? In the air? In the listener’s head?’; ‘Can we recreate the past?’; ‘What is the difference between noise and sound?’

John opened my ears to contemporary music and encouraged my burgeoning passion for early music, guiding me through the philosophical issues surrounding historical performance practice as well as lighting fires under my musical passions. He exhorted me to make my own editions from original manuscripts and to plan eclectic concert programmes.

John is an authority on medieval and Renaissance music, but his interests do not stop there. He generously shares all his vast knowledge with grace and his inimitable twinkle. I shall forever cherish his encouragement, sage advice and humour. Laurence Cummings is currently enjoying his 25th and final year as music director of London Handel Festival (to 20 April).

The full score

Harpsichordist and conductor Laurence Cummings on the lasting influence of his music tutor John Milsom

All in good time: Jordi Savall conducts Le Concert des Nations and La Capella Reial de Catalunya, Barcelona, 2022

BBC MUSIC MAGAZINE 19

Profound influence: Christ Church Cathedral; (left) John Milsom

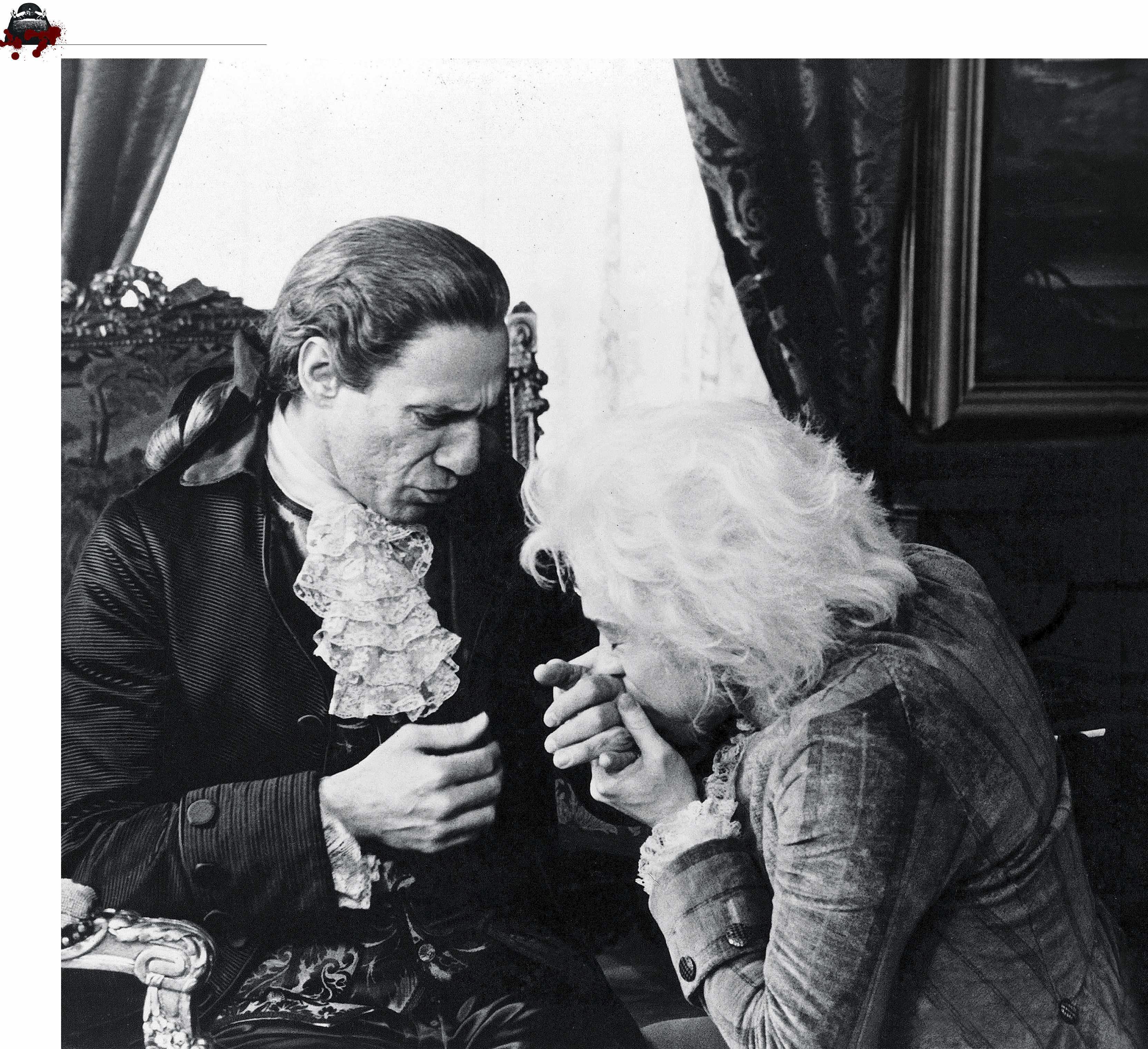

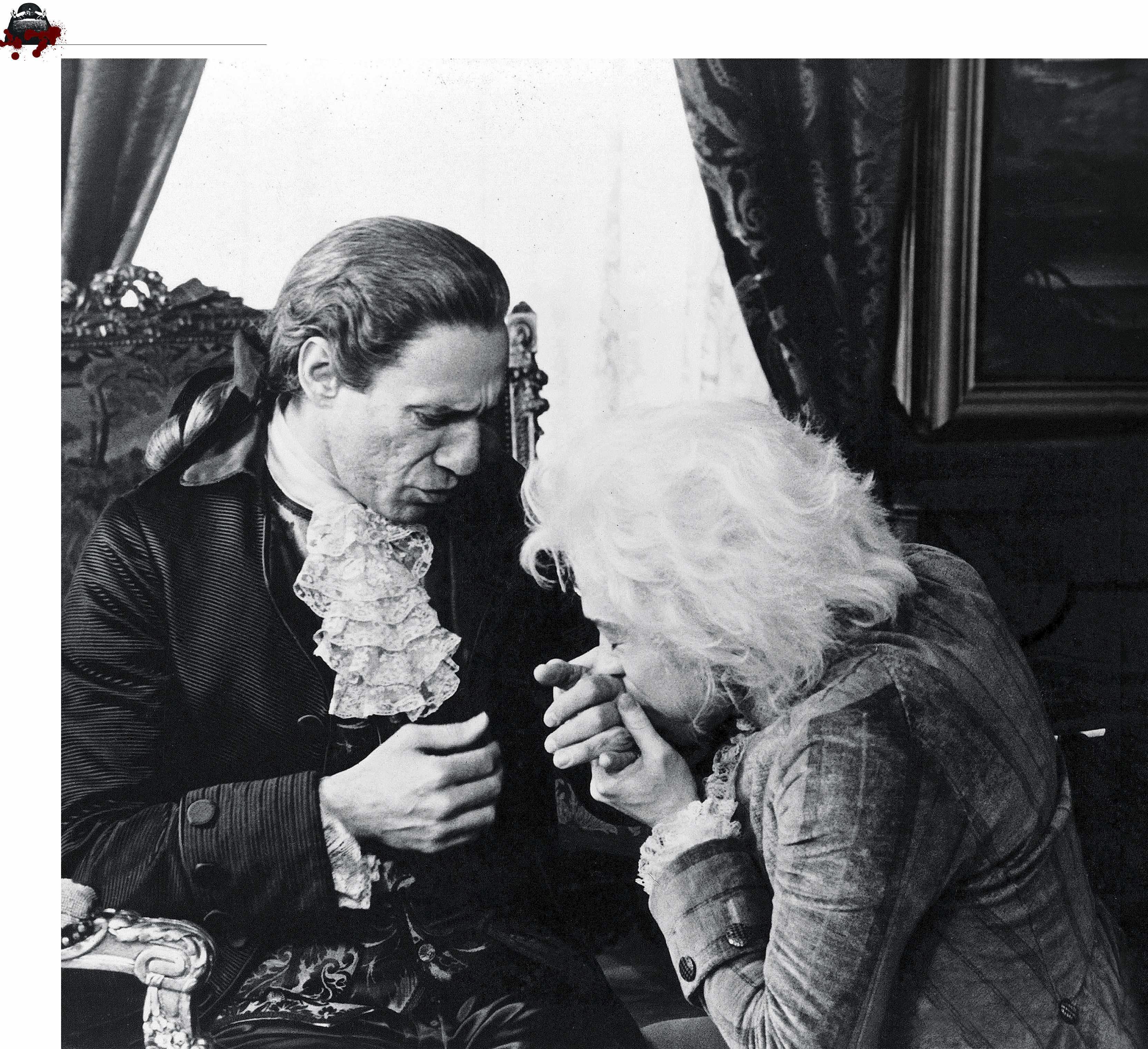

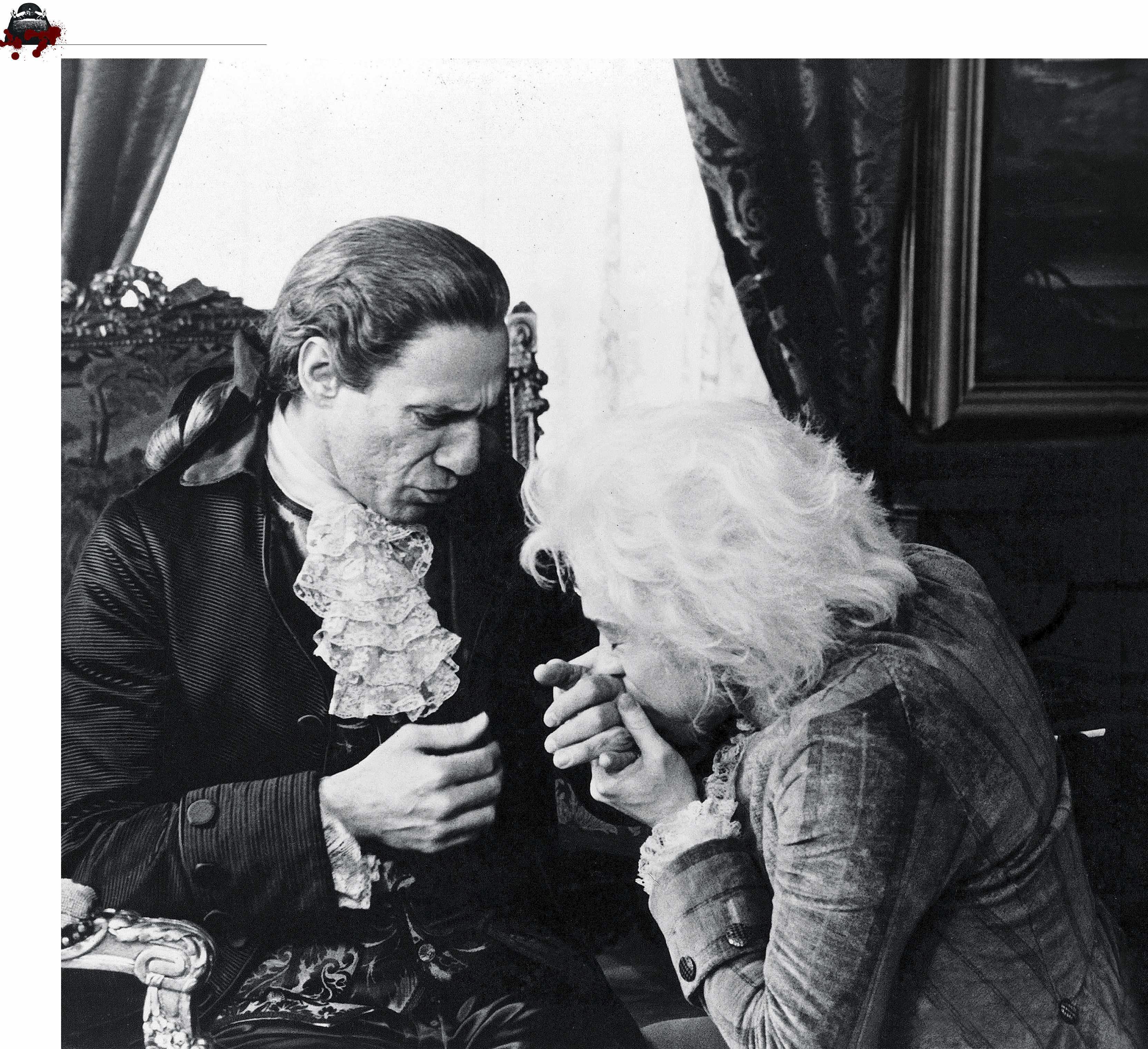

40 YEARS OF AMADEUS 28 BBC MUSIC MAGAZINE GETTY

M S C

MALICE & MURDER

‘Everything you’ve heard is true,’ proclaimed the posters for Miloš Forman’s Amadeus – a cinematic tale of genius and envy, based on Peter Shaffer’s acclaimed stage play about Mozart and Salieri’s bitter rivalry.

Forty years on, Charlotte Smith looks back at a very special production

and don’t make up: F Murray Abraham as Salieri and Tom Hulce as Mozart in Amadeus BBC MUSIC MAGAZINE 29 Amadeus 40th anniversary

Kiss

A cast of thousands

From its unlikely conception in a pub, The Really Big Chorus has become a cultural phenomenon, offering amateur singers the opportunity to take part in vast performances, writes Andrew Green

The mix makes it so exciting. Everyone is a small cog in a large machine and they’re swept along in this extraordinary sound

ADecember night at the Royal Albert Hall. Conductor Brian Kay coaxes from the English Festival Orchestra the familiar sounds, full of promise, of the opening to Messiah… then ‘Comfort Ye’ and ‘Ev’ry Valley’ from the solo tenor. Finally, massed banks of altos herald the arrival of the 2,500-strong chorus with ‘And the glory of the Lord’. And you can’t help breaking into a broad smile. As Kay observes, ‘That wall of sound knocks me off my perch every single time.’

This year sees the 50th anniversary of the launch (although not under this name) of The Really Big Chorus (TRBC), celebrated with events throughout 2024. There have been TRBC renderings of other choral favourites in the Albert Hall or on summer forays abroad, but the winter Messiahs (always chorally unrehearsed) are still the heart and soul of the choir’s activities.

Broadcaster and The Times columnist Libby Purves has been contributing her alto to TRBC Albert Hall Messiahs for many years. ‘I could never join a choir because of shift work and freelancing,’ she says. ‘So, when I heard about TRBC and its openness to us unskilled types who can’t really sightread, I got my hands on the Choraline alto parts via the internet. It was a marvellous revelation. The joy is finding yourself singing alongside really good people from real choirs! We learn from them.’

Singers arrive each year from around the globe. Norwegian Tor Hagir recalls approaching

his first TRBC Messiahs ‘with a bit of scepticism because of the sheer number of singers involved. Surely this Messiah couldn’t be done precisely. In fact, it went far better than I’d expected. I enjoyed it so much I’ve kept coming back. One great pleasure is meeting people from Australia, the USA and all around Europe.’

This international dimension to the chorus also pervades TRBC performances of other repertoire. Brian Kay – TRBC’s longstanding principal conductor – recalls an Australian soprano ‘who sang the Verdi Requiem one evening in Sydney, jumped on a plane and sang it the next night with us in the Albert Hall!’

So how come the Albert Hall performances work so well, with little or (in the case of Messiah) no choral rehearsal? ‘Some singers arrive knowing the music extremely well,’ Kay observes. ‘A good few more think they do. Others don’t know it at all well. But that mix is what makes it so exciting. Everyone is a small cog in this large machine, and they’re swept along in

60 BBC MUSIC MAGAZINE The Really Big Chorus

the extraordinary sound. Life is ever more busy and many amateur singers can’t commit to 35 rehearsals a year with a choir. So, TRBC is ideal.’

Like many another brainchild, this one was conceived in a pub – to be precise, The Queen’s Arms in London’s Kensington district. Over lunch there one 1974 day, Imperial College scientists Don Monro (a clarinettist) and David Burgess (a trumpeter) were reflecting on a successful – if barely rehearsed – Messiah performance in which they had recently taken part. Somehow, the proposition was sparked (alcohol-propelled? I couldn’t say…) that they should straightaway, that very moment, pop round the corner to the Albert Hall and try booking it for an unrehearsed amateur performance of Handel’s masterpiece. After an amount of fast-talking the pair emerged, triumphant, with their 5 December 1974 date.

Other musical members of staff at Imperial College were roped in to support this embryonic venture, run initially by ‘The Tuesday

BBC MUSIC MAGAZINE 61

Largely Handel: The Really Big Chorus performs ‘Messiah from Scratch’ at the Royal Albert Hall; (below) conductor Brian Kay feels the power; (opposite) the Messiah programme from 1974

CHRIS CHRISTODOULOU

Composer of the month

Composer of the Week is broadcast on Radio 3 at 4pm, Monday to Friday. Programmes in April 2024 are:

1-5 April WA Mozart

8-12 April Brahms

15-19 April Grieg

22-26 April Marianna Martines

29 April – 3 May Debussy

Salieri’s style

Looking forward

From his very earliest works, Salieri began to take on board the novel operatic reforms pioneered by Gluck (left), using accompanied rather than secco recitative and avoiding the da capo aria format that held up the dramatic action, preferring instead to write simpler two-part arias.

Overtures Salieri is credited with having reformed the operatic overture. Previously, most overtures consisted of multi-partite orchestral works that bore no relation to the opera they prefaced, but Salieri attempted to evoke the character, moods and situations of the drama to come.

Big occasions Salieri’s works were generally written for specific occasions and thus part of the event-centred musical culture that prevailed before the 19th century. An example of such an ‘occasion piece’ was Prima la musica e poi le parole, written for an imperial function and performed at the Orangery at the Schönbrunn Palace in a double bill with Mozart’s Der Schauspieldirektor

Multi-tasking Like most jobbing composers of his era, Salieri was required to provide music for a variety of different civic and sacred purposes and his output was not confined to opera. His Requiem – one of his final works, sung at his own funeral – is deeply expressive, of considerable melodic interest and worthy of the attention of present-day choirs.

Antonio Salieri

Forget the hate-filled murderer of Mozart, says Alexandra Wilson; the real Salieri was an opera composer of considerable standing

ILLUSTRATION: MATT HERRING

Remembered almost exclusively as a supporting role in someone else’s biopic, Antonio Salieri really deserves a film in his own right. A workaday composer, living in the shadow of a genius; a dull establishment figure to Mozart’s bohemian freelancer – these are the clichés that film and fiction have passed down to posterity.

In fact, Salieri was an orphaned teenager who was ‘saved’ by the kindness of others, and who would ultimately find himself working for royalty, being courted by theatres all over Europe and associating with the most celebrated artistic figures of the era. Though the music textbooks

chamber composer to Emperor Joseph II of Austria, Florian Gassmann, who visited Venice regularly to write operas for the Carnival. Gassmann agreed to take the boy on as a pupil and musical apprentice, taking him back with him to Vienna.

Salieri soon became a recognised composer in his own right, composing six operas in the space of two years. Particularly popular and noteworthy was his Armida, based on Torquato Tasso’s libretto which, full of magic and romance in the time of the Crusades, would also inspire works by Lully, Handel, Gluck and, later, Rossini and Dvořák. Following Gassmann’s death in 1774, Salieri

By the 1780s, still in his 30s, he was the most important musician in the Austrian Empire

have chosen to forget the fact, he was a composer of considerable historic significance, both through his own artistic reforms and through the influence he had on many of the major composers and singers of the early-19th century.

Salieri was born in 1750 in Legnago, a small town on the border between two Italian states, the Kingdom of Venice and the Duchy of Mantua. Details of his childhood are scant, but it is clear he grew up in a household where music was encouraged and that he showed early promise. It was fortunate indeed that when he lost his parents he was taken under the wing of a wealthy family acquaintance: one Giovanni Mocenigo, who took him to Venice – then an exceptionally vibrant and important operatic centre – for musical training. This led in turn to an even luckier break in the form of an introduction to the

succeeded his teacher as court chamber composer and was also appointed director of the Italian Opera at the Nationaltheater.

Italian opera was something of a lingua franca in the late-18th century, an art form enjoyed and patronised by the aristocracy all over Europe. To have an Italian opera composer in his personal employ would have been a mark of prestige for a patron such as Joseph II, even if Salieri had left the Italian peninsula at a very young age, been influenced by a variety of national trends and wholeheartedly embraced Austrian musical life.

Salieri rose through the ranks at the Viennese court, taking on a succession of progressively more responsible roles. By the 1780s, still in his 30s, he was the most important musician in the Austrian Empire and held one of the top musical jobs in the world (Hofkapellmeister),

GETTY 68 BBC MUSIC MAGAZINE

BBC MUSIC MAGAZINE 69 COMPOSER OF THE MONTH

Reviews

Recordings and books

rated by expert critics

Welcome

We’ve been revelling in some little-known classics this month.

Songs by the visionary French composer Rita Strohl, the colourful orchestral music of Dorothy Howell and a brace of piano concertos by Norway’s Chopin student Thomas Tellefsen are among the less familiar gems that have delighted our reviewers. Of course, we’ve also plenty of more recognisable repertoire in dazzling new performances. Highlights include a new Má vlast for the ages; Lang Lang, colourful and incisive in Saint-Saëns; and a revelatory new take on Vivaldi’s Stabat Mater from Andreas Scholl and the Accademia Bizantina. Ear-opening performances abound, too, with Solomon’s Knot, I Fagiolini (see opposite), Beatrice Rana and the Neave Trio among the musicians in sublime form.

Steve Wright Acting reviews editor

This month’s critics

John Allison, Nicholas Anderson, Michael Beek, Terry Blain, Kate Bolton-Porciatti, Geoff Brown, Michael Church, Christopher Cook, Martin Cotton, Christopher Dingle, Misha Donat, Jessica Duchen, Rebecca Franks, George Hall, Malcolm Hayes, Claire Jackson, Stephen Johnson, Berta Joncus, John-Pierre Joyce, Nicholas Kenyon, Ashutosh Khandekar, Erik Levi, Andrew McGregor, David Nice, Roger Nichols, Ingrid Pearson, Steph Power, Paul Riley, Anne Templer, Roger Thomas, Sarah Urwin Jones, Kate Wakeling, Alexandra Wilson

KEY TO STAR RATINGS

HHHHH Outstanding

HHHH Excellent

HHH Good

HH Disappointing H Poor

RECORDING OF THE MONTH

A rediscovered gem of the ‘Colossal Baroque’

Kate Bolton-Porciatti thrills to the latest album from I Fagiolini, which casts vivid light on a 17th-century choral masterpiece

Benevoli

Missa Tu es Petrus et al I Fagiolini, The City Musick/ Robert Hollingworth CORO COR16201 58:00 mins

This revelatory project unveils the shadowy Franco-Italian composer Orazio Benevoli –born in 1605 in Rome, the son of a French baker, he became choirmaster of the celebrated Cappella Giulia of St Peter’s in the mid-17th century. As this world premiere recording of his Mass Tu es Petrus amply demonstrates, Benevoli was a vital figure in forging the so-called ‘Colossal Baroque’ style, developed to fill the vast spaces of Roman basilicas with resplendent sound.

The Missa Tu es Petrus is a tour de force of the Catholic revival, sumptuously scored for

four choirs and intended to be performed in the new basilica of St Peter. The latter had been recently completed, hence the Mass’s dedication to the apostle Peter – the foundation ‘stone’ (‘petrus’) of both the musical and the architectural edifices. While much has been made of the polychoral tradition in Baroque Venice, Benevoli’s work shows that Rome, too, boasted a similarly extravagant tradition of sacred music that exploits the contrasts and combinations of multiple choirs of voices and instruments, creating colossal blocks of sound.

The composer’s idiom looks both backwards and forwards, as sober stile antico polyphony (recalling Palestrina) gives way to ornate soloistic writing. Above all, the Tu es Petrus Mass is a highly expressive work, with its evocative word painting, ‘angelic’ vocal lines and rhythmic vitality and variety. Recorded here in the round, with a battery of instruments enriching the vocal ensembles, the work engulfs the senses just as it must

78 BBC MUSIC MAGAZINE

MATT BRODIE, RICCARDO CAVALLARI

CHOICE

Recording of the Month Reviews

have done in Benevoli’s day in the echoing spaces of St Peter’s.

I Fagiolini and the instrumentalists of The City Musick produce a multi-hued tapestry of sound, colouring each of the four choirs with different instrumental timbres: choir one is a cappella, the other three are fleshed out, respectively, with cornett/ trombone, violin/bass violin and recorder/dulcian, so highlighting the four different choirs with textural contrasts and a distinctly Roman chiaroscuro. Ever responsive to the words and their liturgical context, director Robert Hollingworth and his singers find just the right equilibrium between balanced ensemble singing and a more highly charged

soloistic delivery. Using one or two voices to a part (as seems to have been Roman practice in Benevoli’s day) ensures that the polychoral sound remains clean and transparent – yet it never lacks opulence. The instrumental playing,

The polychoral sound is clean and transparent – yet it never lacks opulence

expertly led by William Lyons, is controlled, stylish and beautifully integrated into the vocal ensemble.

Benevoli’s Mass is based on Palestrina’s venerable six-voice motet Tu es Petrus, a radiant and liquid performance of which opens the recording.

Extravagant sounds: I Fagiolini and Robert Hollingworth turn deserved attention to an overlooked master

Performer’s notes Robert Hollingworth

How did you come to record this little-known music?

In the public awareness, I think there’s a hole in music history when it comes to the mid-17th century – whether in England, France, Germany or Italy. Hugh Keyte (who has worked with Andrew Parrott and others) put me on to Benevoli and I got very excited. There are eight four-choir masses: my job was to choose the best of them and to get editing. What about Tu es Petrus made it such a perfect fit for I Fagiolini?

The Mass movements are then interspersed and contrasted with works by Benevoli’s contemporary Bonifazio Graziani: four intimate motets scored variously for three to six solo voices and accompanied by a delicate continuo ensemble. Again in world premiere recordings, we hear Domine, ne in furore tuo, a sensuous confection redolent of Monteverdi, and Venite gentes, whose florid vocal melismas are exquisitely sung by the five soloists. The honeyed Ad mensam dulcissimi and the fervent, six-part Justus ut palma bring this glorious disc to an ecstatic conclusion.

PERFORMANCE HHHHH

RECORDING HHHHH

I hope we’ve fitted around it by moulding how we sing to its idiosyncrasies. A specific example: ‘alto’ at this time seems generally to have implied ‘high tenor’ rather than countertenor, and this means getting four guys to sing higher than usual in their range but still with Italian élan and that crucial ear for balance and style. But more generally, I feel that the best performances of polyphony require more character and energy at the level of the individual line than has become fashionable. The aural sheen of polyphony is a siren-like sound that draws in listeners and reviewers alike, but the music is in the part-writing, the play between the parts – and the text!

What made this work such a rewarding discovery?

Various things, including the gorgeous geography of having four choirs – and the doubling-up of those four choirs to eight. But really, it’s the sheer quality and invention of the piece. Just take the second half of the Credo, which is constantly refreshing the texture – and then pulls a blinder in the final Amen with a section of such joyous, mental virtuosity that I can’t quite believe the score.

BBC MUSIC MAGAZINE 79