SAFE SPACE

In urban Costa Rica, locals are welcoming wandering sloths

SEPTEMBER 2023 Issue 10 Vol 41

How to see whales in the UK Gorilla adventure in the Congo Protecting wildlife in the high seas Chough comeback in Kent discoverwildlife.com ENTER OUR PHOTOGRAPHY COMPETITION PAGE 56

What’s happening right now

BBC WILDLIFE September 2023 8

CAT ATTACK

At first, you may think that this category winner from the BigPicture Natural World Photography Competition pictures a mother snow leopard playing with her kitten. But look closer – the kitten is in fact a Pallas’s cat. Both felines share cold, high-altitude mountain habitat in Central Asia – the Tibetan Plateau in this case – though it’s very rare to see a leopard prey upon its diminutive cousin.

DONGLIN ZHOU/BIGPICTURE 2023 discoverwildlife.com BBC WILDLIFE9

A HOOT

As summer shades into autumn and the evenings begin to draw in, tawny owls make their presence felt. Young owls that fledged in spring are now dispersing to find territories, causing major upset among established pairs, including their own parents. The hooting and shrieking usually peaks on clear, bright evenings around a full moon, such as the so-called Harvest Moon.

BBC WILDLIFE September 2023 16

Tweet of the Day: Mike Toms describes his encounters with tawny owls

Listen out for tawny owls during this year’s famous Harvest Moon, which falls on 29th September

WHAT

Venus flytraps capture insects

10 carnivorous plants

Not all carnivores have teeth – some

1 VENUS FLYTRAP

Best-known carnivorous plant; uses a snap trap to capture prey

2 COMMON BLADDERWORT

Belongs to the Utricularia genus, known as bladderworts, which use bladder traps to suck in their food

3 SUNDEWS

Plants that use secretions to ensnare their meals

4 CALIFORNIA PITCHER PLANT

Like all pitcher plants, this species uses a pitfall trap

5 CORKSCREW PLANTS

Genlisea species use a ‘lobster pot trap’ – easy to enter, but hard to leave due to spikey inward-pointing bristles

6 RAINBOW PLANTS

Plants of the Byblis genus secrete a glue-like substance called mucilage

7 NEPENTHES RAJAH

Malaysian pitcher plant species known to trap shrews, frogs and even birds!

8 ALDROVANDA VESICULOSA

Its snap traps are arranged in circles around a central free-floating stem

9 HUMPED BLADDERWORT

An aquatic, mat-forming species, famed for being very genetically efficient

10 BROCCHINIA REDUCTA

A rare carnivorous bromeliad that lures and drowns insects

Dormouse release

Almost 40 rare hazel dormice have been reintroduced into a woodland at the National Trust Calke Abbey estate in Derbyshire in an attempt to halt the disappearance of this endangered species from the UK.

According to the People’s Trust for Endangered Species, the native hazel dormouse is extinct in the area.

years

MEET THE VOLUNTEER

Katty Baird

National Museums Scotland volunteer and author of Meetings with Moths on documenting British Lepidoptera

The entomology collection of National Museums Scotland is held at the National Museum of Scotland’s Collections Centre in Edinburgh. Ecologist Katty Baird works as a volunteer with the British Lepidoptera collection, documenting the number of different specimens onto a database. “This helps the museum know what material they have and where it is housed in the collections centre,” she says. “This makes it much easier for researchers to find the butterflies and moths they are looking for.” Katty also documents the details of some specimens –when and where they were caught – and adds these to the National Moth Recording Scheme.

“I have a particular interest in the moths collected by Alice Blanche Balfour, a naturalist who lived in East Lothian about 100 years ago. She recorded butterflies and moths in the same places that I now record moths. Her specimens and her notebooks are cared for by National Museums Scotland,” explains Katty. “It has been fascinating to compare not only the species she saw, but also the equipment and techniques she used.” Working at the museum has improved Katty’s knowledge of UK moths and she has

also learnt a lot about how entomological collections are cared for.

“My main interest is in moths. I spend a lot of time recording them in the field and send my records to the National Moth Recording scheme where they contribute to understanding moth distributions in the UK,” she states. “But there is also masses of data held in museum collections about moths that were around decades ago. Adding this information to our modern databases enhances our understanding about changing moth distributions and means the efforts of past recorders are made to count.”

“While volunteering I have raised the profile of a talented Scottish entomologist from the past – I am honoured to be able to make Alice Balfour and her collection better known and the enormous amount of data she collected available. I like to think I am following in her footsteps – I hope she would be proud! As well as adding her specimen data to the National Moth Recording Scheme I hope this project also celebrates the role of biological recorders, both now and in the past – and inspires recorders of the future.” Jo Price

discoverwildlife.com BBC WILDLIFE17

species lure their prey into a deadly trap

IN BRIEF OWL: DANNY GREEN; DORMOUSE: ZSL; VENUS FLYTRAP: GETTY; MOTH: NATIONAL MUSEUMS SCOTLAND

Katty Baird has been volunteering for National Museums Scotland for four

Garden tiger moth collected by Alice Balfour

GIMME SHELTER

Photos by SUZI ESZTERHAS

Shocking situation

The plight of this Hoffmann’s twofingered sloth – one of two sloth species in Costa Rica – in the small town of Puerto Viejo is emblematic of the threats facing these slow-moving mammals. After its home tree was felled, it clambered along these power lines as it would use vines in a tropical forest – but had nowhere to go. Fortunately, Rebecca Cliffe, founder of the Sloth Conservation Foundation (SloCo), relocated it to a safer wooded area. Others are not so lucky: hundreds of sloths are electrocuted each year on poorly insulated cables.

BBC WILDLIFE September 2023 40

In Costa Rica, a pioneering charity is helping vulnerable sloths that have lost their homes due to deforestation

PORTFOLIO

discoverwildlife.com BBC WILDLIFE41

PHO O

O O

WILDSHOTS OUTREACH BBC WILDLIFE September 2023 50

Shots Outreach is sparking a passion for wildlife in young people by teaching photography skills

By SARAH MCPHERSON

By SARAH MCPHERSON

An initiative in South Africa is using cameras to nurture the conservationists of tomorrow

PHOTOGRAPHY ●

Wild

TOTALLYCHOUGHED

September 2023 2

A captive-bred chough (pronounced ‘chuff’) take its first steps on the White Cliffs of Dover

After a 200-year absence, the rare red-billed chough has been returned to its ancient Kent homeland

Words and photos by R HAR TAY OR-JON S

discoverwildlife com i coverwildlife co

Choughs

featured on The One Show on 26th July. Catch up on iPlayer.

Why don’t birds have teeth?

You just need to glance at a 150-million-year-old fossilised Archaeopteryx to see that birds’ ancestors were not toothless. And yet avian dentition is now as rare as proverbial hens’ teeth. So what exactly happened between then and now?

Biologists aren’t quite sure. What they do know is that, about 100 million years ago, genetic mutations emerged that prevent tooth development

by blocking enamel and dentine production. These can be reactivated artificially to induce chicken embryos to produce peg-like reptilian teeth.

More mysterious is why they lost them. One possibility is that replacing teeth with a horny beak reduces the payload, making flight more efficient.

Beaks are certainly highly versatile tools that can be wielded to sip nectar from flowers, tear flesh from bones, crack nuts, filter food from water and

pluck insects from the air. Compared to teeth, though, they are less useful for chewing and grinding food. The gizzard, a muscular section of the gut often filled with swallowed stones, can help there, but sometimes, only teeth –or something very like them – will do. Sawbill ducks such as goosanders and mergansers have developed tooth-like serrations along the edge of their bills to help them hold onto their slippery fish prey.

BBC WILDLIFE September 2023 82

Email your questions to wildquestions@immediate.co.uk

With Stuart Blackman

How and why do bees make honey?

Honey is a simple pleasure. It’s easy to forget, while enjoying its luxurious fragrant sweetness on a slice of buttered toast, that it is the end-product of a sophisticated production line involving state-ofthe-art biological machinery and thousands of skilled workers.

Honey starts out as nectar, a rather dilute solution of various sugars that flowering plants produce to attract pollinating insects. Most of these visitors drink it down on the spot as sustenance for themselves. A foraging worker bee, though, does things differently.

After sucking it out of the flower with its straw-like proboscis, the bee deposits the nectar in its proventriculus or honey stomach. This can hold a lot of nectar – up to almost half the bee’s unloaded body mass – and filling it may require a thousand flower visits. The transformation of nectar into honey begins while the bee is still on the wing, as the proventriculus produces enzymes that break down the larger, complex sugar molecules into smaller ones.

On arrival back at the hive, the forager unloads its cargo by regurgitating the sugary solution to other workers, who pass it back and forth between each other, adding more enzymes each time and frothing it up with their mouthparts to encourage the evaporation of water.

Once it is sufficiently sticky and viscous, the concoction is laid down in the beeswax

cells of the honeycomb and the workers continue the drying process by fanning it with their wings. Only when the water content has been reduced to about 18 per cent (from about 75 per cent in the original nectar), do they seal the cells with beeswax lids. At this point, it is well and truly honey.

While pollen provides the colony with most of its protein and nutrient needs, honey is its primary source of sugar. Crucially, the stored honey serves as a stockpile to see it through the unproductive winter months. Unlike wasp and bumblebee colonies, which die off at the end of the summer, honeybees overwinter within the hive. Honey is an ideal longterm store of energy because it has an exceptionally long shelf-life. Pots from ancient Egyptian tombs have been found to contain honey that is supposedly perfectly edible. The high concentrations of sugar make for a hostile environment for yeasts and bacteria that might cause it to spoil. Its life span is extended further by one of the enzymes produced by the proventriculus, which generates hydrogen peroxide and gluconic acid, both of which are toxic to microbes.

An average hive produces about 11kg of honey in a season, which requires the foragers to fly over 1.5 million kilometres between them. A standard jar of honey requires about 80,000km. The sheer effort that has gone into making honey is worth remembering when spreading it onto toast –it can surely only add to the pleasure.

discoverwildlife.com BBC WILDLIFE83 GOOSANDER: ALAMY; BEE: SOLVIN ZANKL/NATUREPL.COM

“Honey serves as a stockpile to see bees through the winter”

Technically this goosander doesn’t have teeth; they’re tooth-like serrations

A honeybee drinks honey inside the hive

Go oWILD!

Y

BBC WILDLIFE September 2023 88

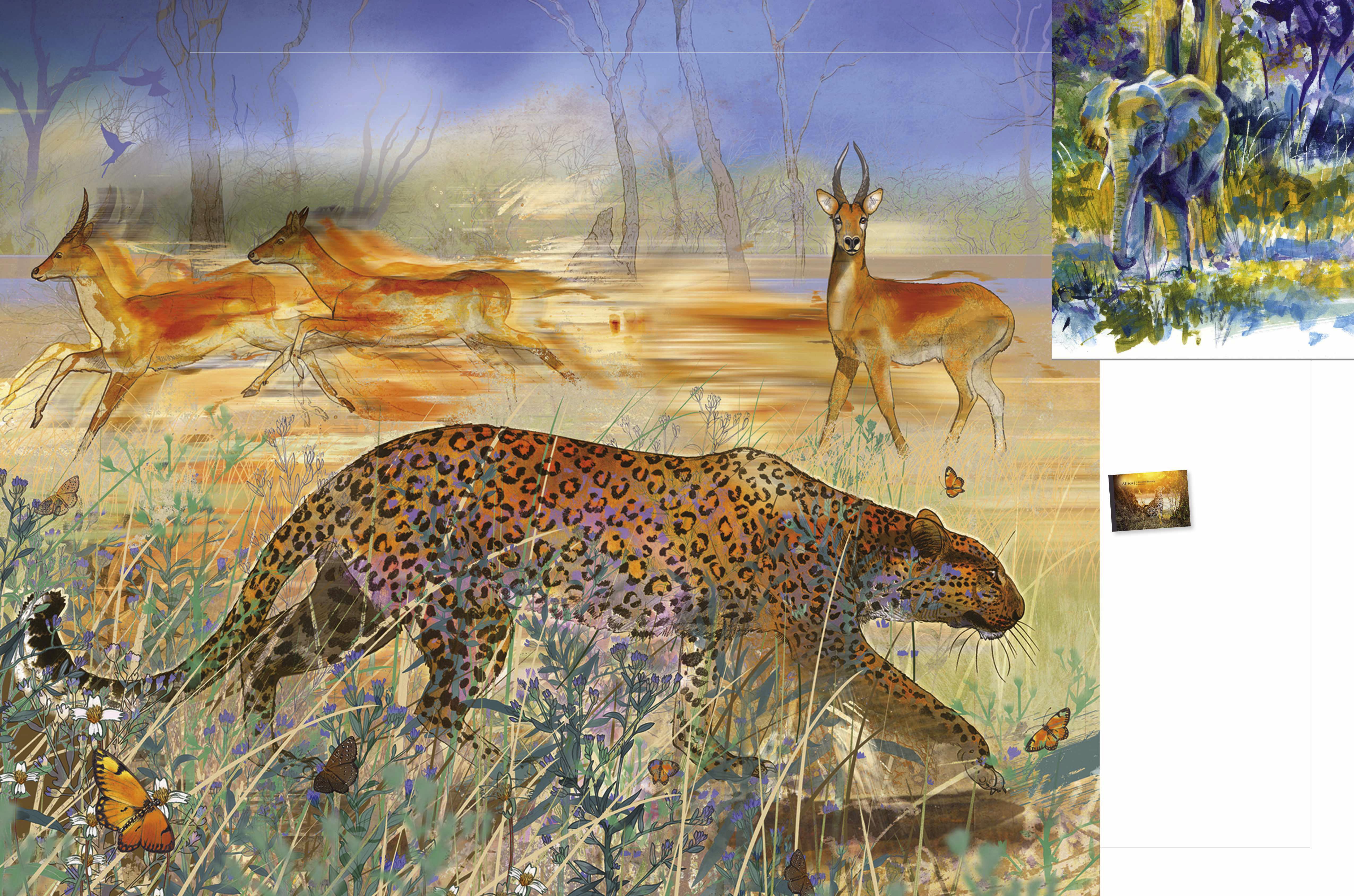

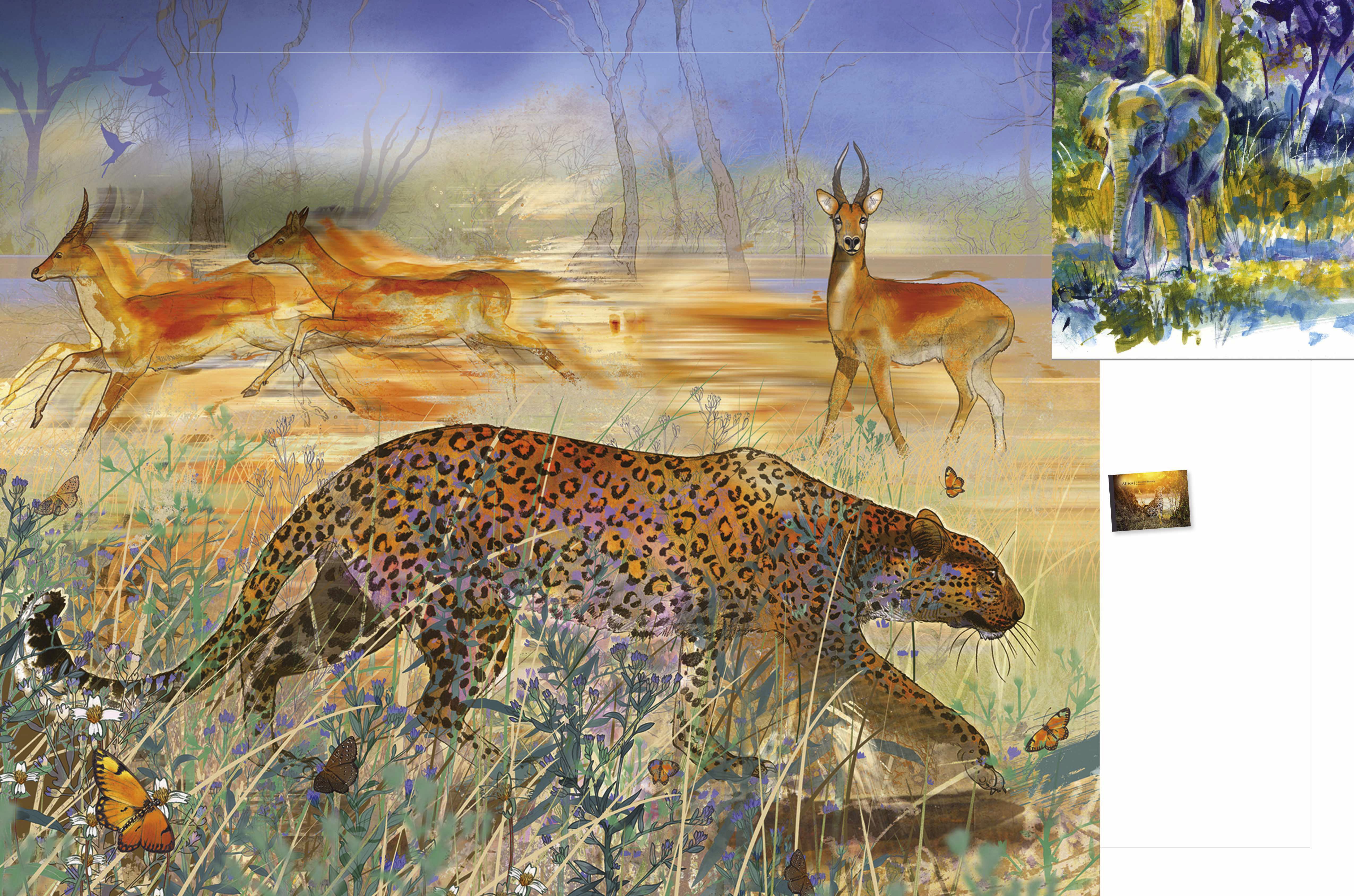

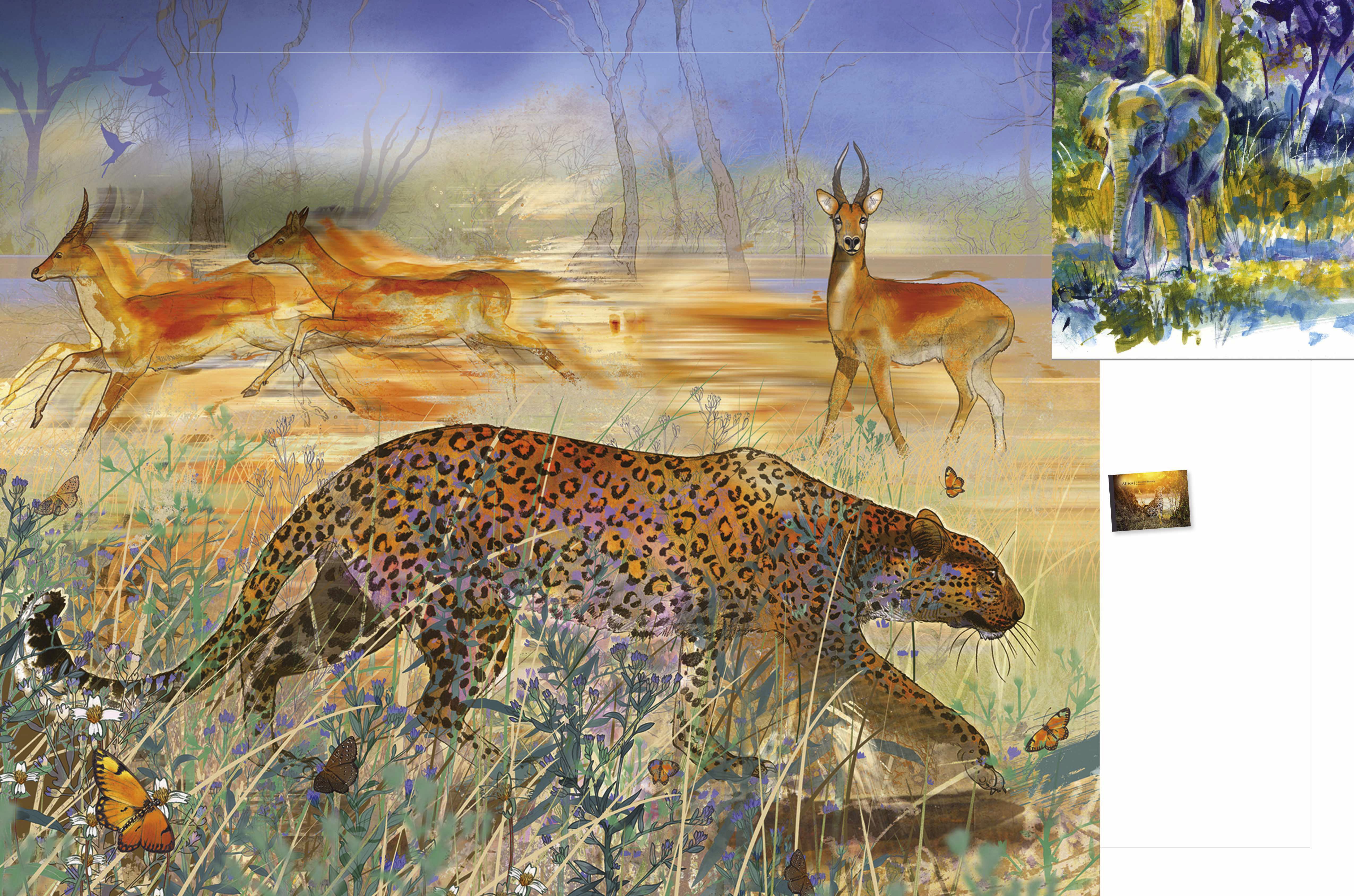

n frican odyssey

f i C i J y

W shellyperkins.co.uk, £35

Wildlife artist Shelly Perkins documents her travels through Africa, sketchbook and camera in hand, in her engrossing new book. Lions, zebra, wild dogs and elephants all star, and Shelly recounts her personal experience of sketching them in the field.

Shelly is no stranger to BBC Wildlife – her illustrations have graced our pages many times over the years in both features and columns. Here, though, we see the full breadth of her talents, from pencil and watercolour field-sketches through to her vibrant, multi-layered studio works and photography as well.

Africa’s varied wildlife and landscapes are brought vividly to life, with the text offering insights into the behaviour of the subjects and the artistic techniques used.

This is a beautiful book for anyone interested in Africa’s flora and fauna or wildlife art in general.

discoverwildlife.com BBC WILDLIFE89 SHELLY PERKINS

BOOK OF THE MONTH A p f om ’ c oo o wo of op o p ow

By SARAH MCPHERSON

By SARAH MCPHERSON