3 minute read

The Currency of Greenwashing

Written by Catherine Bixler

Greenwashing may sound like a painting technique you do to prepare a canvas. It does share some symbolism with the act of covering something up. The term has gained popularity in recent years thanks to the rise in climate change coverage and consumer-generated branding faux pas call outs on social media, both spurred by calls for change and transparency.

Advertisement

That being said, how does the term relate to those things? Greenwashing is, by a conglomerate of definitions, the act of companies marketing their products as helping the environment when the business strategies and impact of the products are actually not eco-friendly at all. The consumer, you, is entranced with green packaging or cute little leaf iconography, and you think you’re doing Mother Nature a solid. It’s a mind game to fool you into buying more stuff, which in essence is the opposite of living a more sustainable lifestyle.

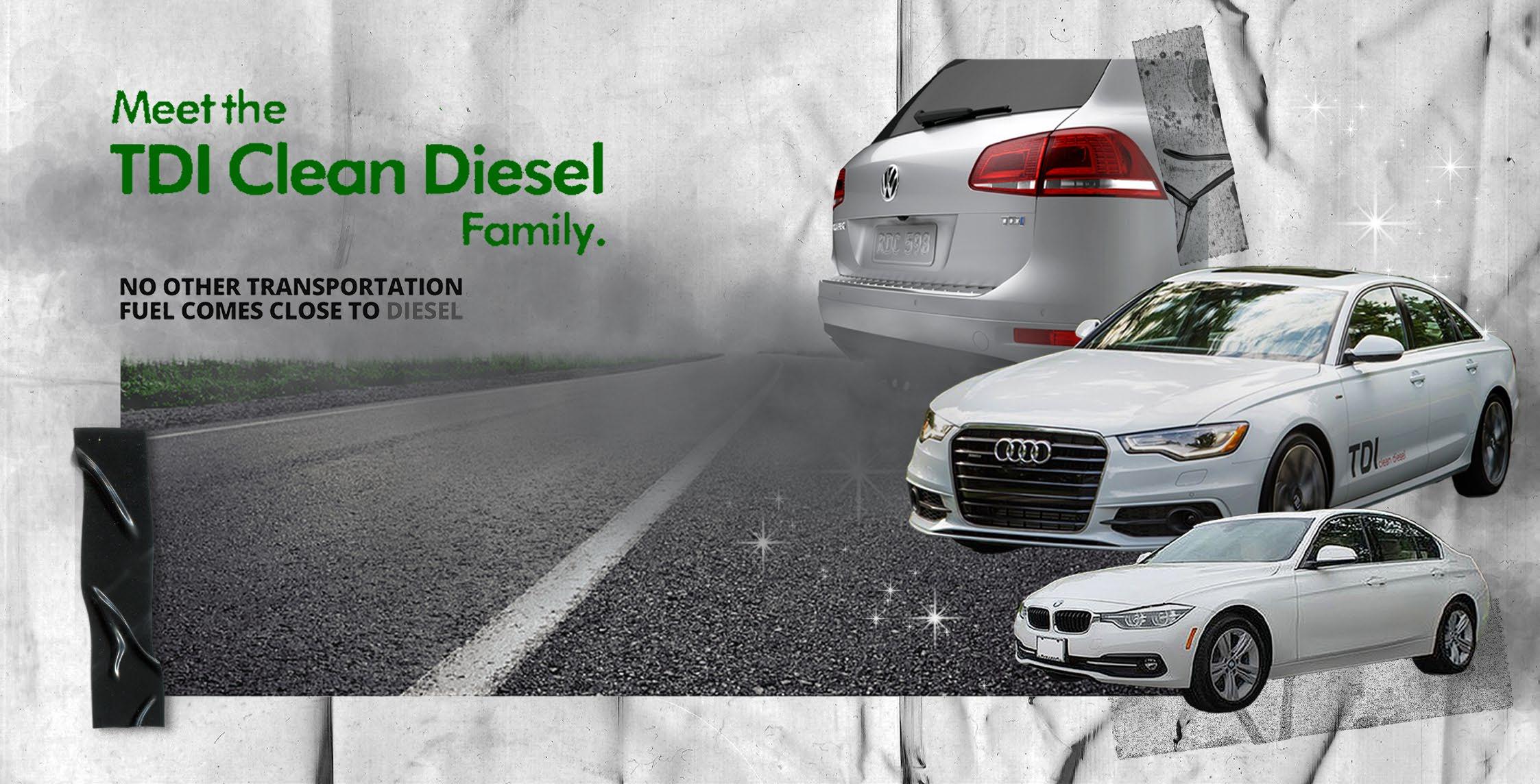

Several industries are guilty of this type of green marketing - a term for strategy behind an 'ecofriendly' product. One such company was the cheating emissions scandal of Volkswagen in 2015. Software in over 500,000 vehicles gave false readings to emissions tests, breaking the Clean Air Act in America. They knowingly did this.

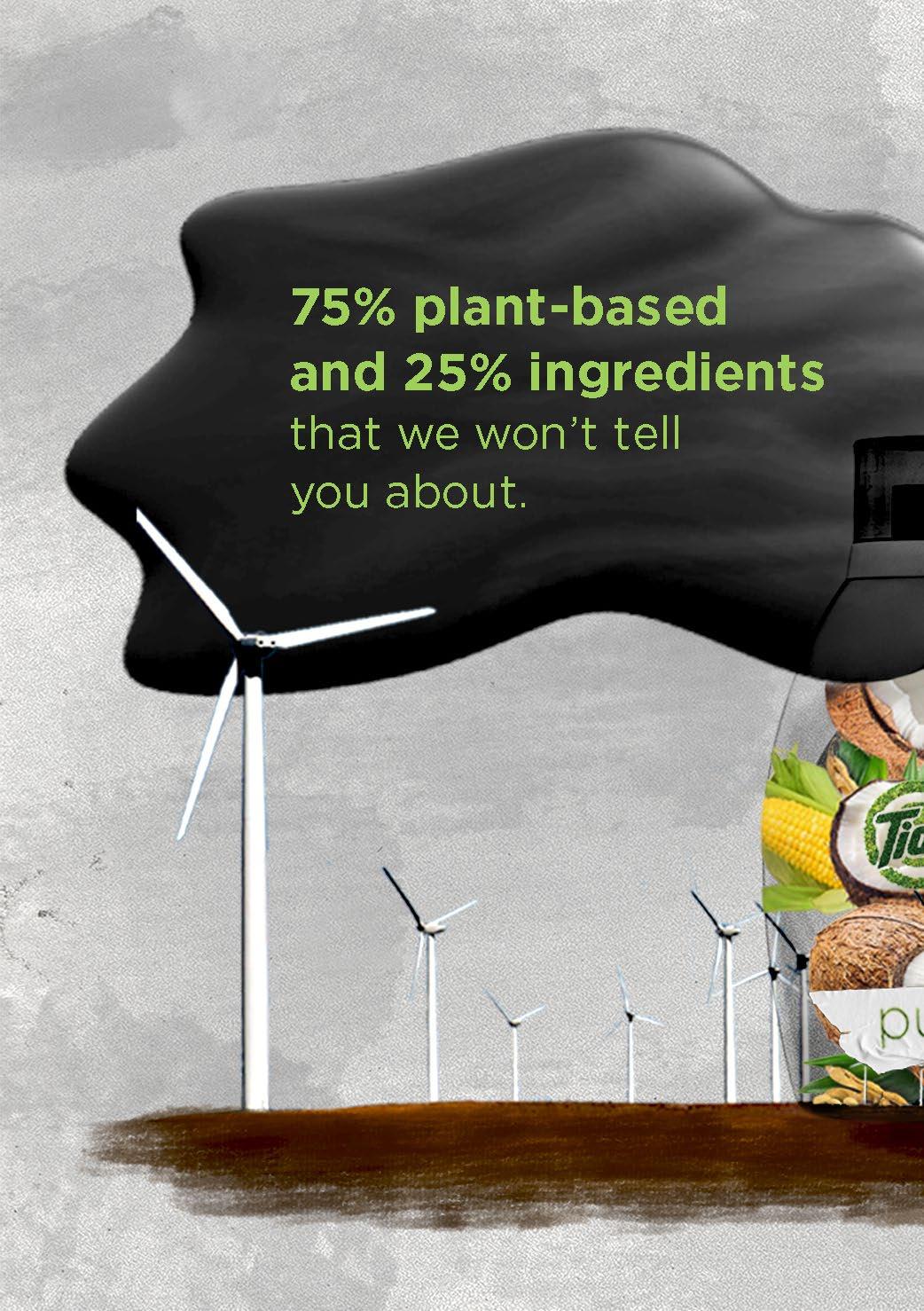

Tide purClean laundry detergent, with its light and airy colored packaging, had initially claimed their formula was elusively plant-based and assumed consumers wouldn’t add up exactly what was the formula. The NAD (National Advertising Division) strongly recommended it tell its customers that it was only 75% plant-based while the rest is made from petroleum-based products. It is important to add that you have to visit their Canadian website to even read the full ingredients list of their purClean products.

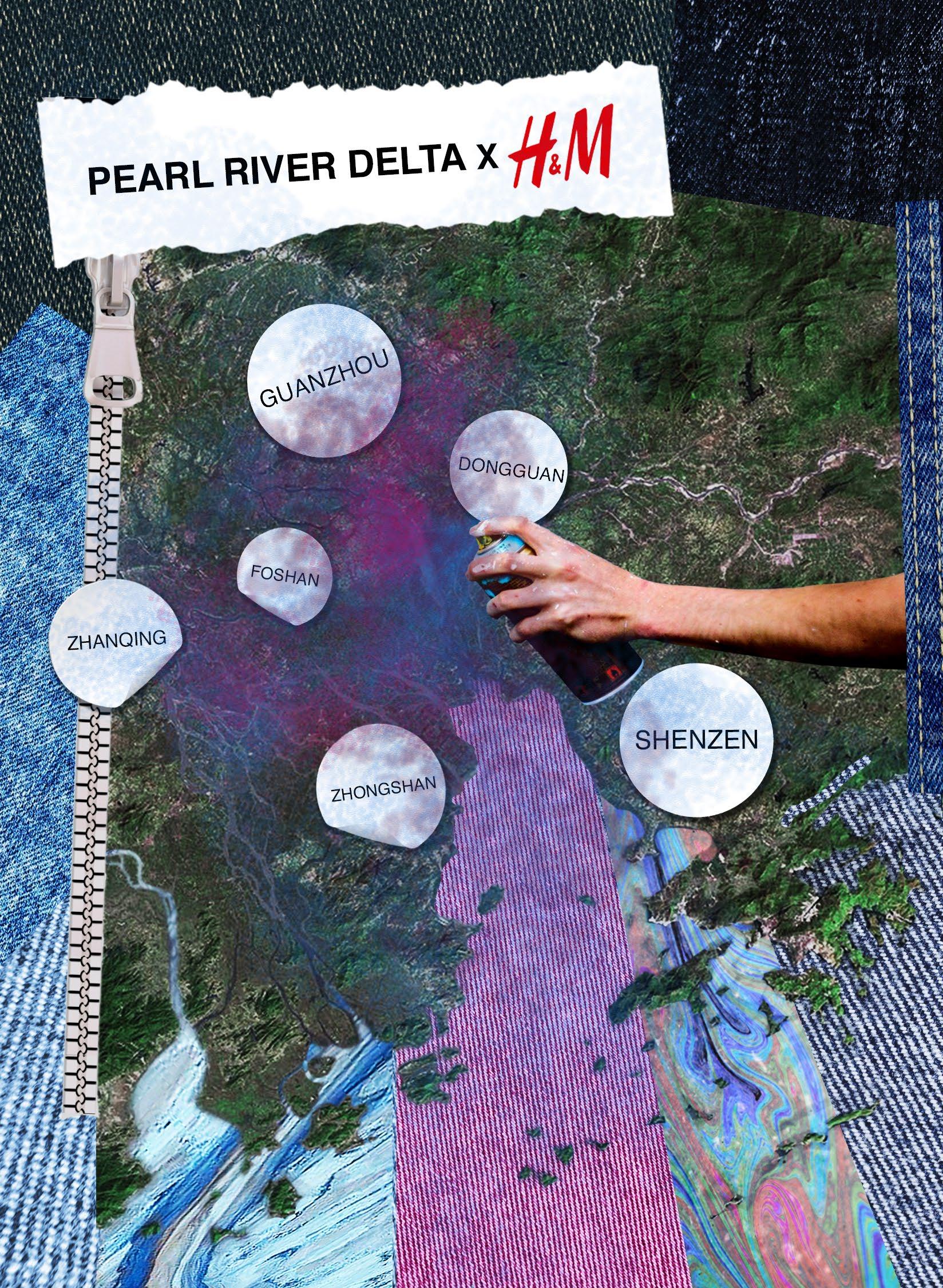

Whilst it is easy to point fingers when companies sell questionable products, it is hard to recognize when the workers in the supply chain aren’t part of the easily sellable ‘green’ image. We have read for years how poor working conditions can be in other countries. One such industry: fast fashion. H&M, Zara, and other international brands have created sustainable goals and initiatives. However, in places like the Pearl River Delta, wastewater from factories making jeans and the like are contaminating the growing urban region. There are multiple industries moving to the Delta, now dubbed a megaregion, due to cheap land and labor, and close proximity to Hong Kong.

I acknowledge it’s hard to protest something so big, expansive, and almost untouchable. We have been fighting the waste of fast fashion for decades. As for products, we have the FDA and NDA to keep companies in check. And if we’re lucky, companies like Volkswagen, and most recently Ford (in the middle of their own diesel emissions scandal) will be held accountable. However, even if all these companies get called out, it usually ends with dishing out millions of dollars to effected consumers and turning a blind eye to the stain on their name instead of cleaning up and improving themselves. What if they saw the money in improving our planet, instead of a cash grab?

Don’t get me wrong; greenwashing is bad. On the other hand, there is a significant rise in green companies doing well because people find them exciting. They want to be involved in something that will improve the planet. Investors see the moneymaking effect of being a genuine, transparent company. It’s important that we see greenwashing for what it is and try to correct it by putting our money where our mouth is. Invest in your choices. Raise your consumer voice. Keep an eye on environmental policy for the years to come. Like there is in government, there should be a checks and balances system between people and brands. ▪