8 minute read

Africa’s Policies Hold Key to

AFRICA’S POLICIES HOLD KEY TO LGBT RIGHTS Here’s how

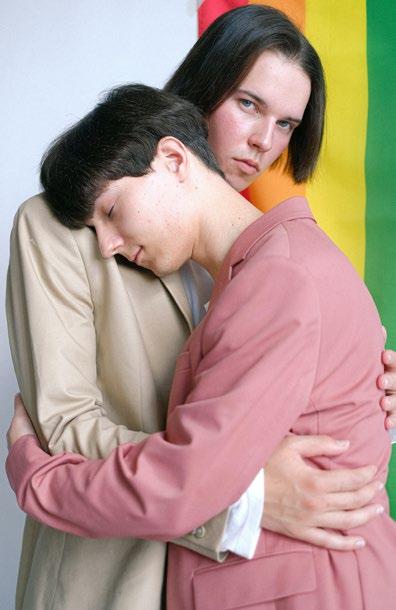

QUESTIONS of sexual orientation and gender identity and expression have continued to divide opinion across the globe.

Advertisement

This is primarily driven by legal, cultural and religious beliefs and interpretations.

In Africa, colonial-heritage laws have been applied to proscribe and criminalise same-sex relationships, behaviours and expressions.

These laws stipulate penalties for same-sex relationships ranging from 10 years to life imprisonment and the death penalty.

Some countries, including Uganda, Nigeria and Togo, have passed these kinds of punitive laws. Others, like South Africa, have reviewed their constitutions to permit homosexuality.

Mainstream public sentiment remains largely anti-homosexual and overshadows constitutionally guaranteed rights in Africa. This is to blame for several instances of civil harassment, killing and mistreatment of people who identify as or are suspected to be lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender (LGBT), among other varieties of sexual and gender minorities.

Yet African governments have signed onto regional commitments and agreements to guarantee the human rights and inclusion of all people. One of the most important legal instruments is the “The African Charter”, which was adopted in 1981 and ratified by all African countries except Sudan.

The Charter grants rights to everyone without exception, with its Article 2 stating that:

“every individual shall be entitled to the rights and freedoms recognised and guaranteed in the Charter without distinction of any kind.”

In Article 4, the Charter asserts that:

“every human being shall be entitled to respect for his life and the integrity of his person. No one may be arbitrarily deprived of this right.”

Regional policy documents such as this offer African countries that don’t protect LGBT rights the basis to draft domestic legislation as the first step to protection to all.

AMBITIOUS ASPIRATIONS

The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights is charged with ensuring that African Union member states protect the rights of all. The commission has several instruments that set out to ensure this happens. Frameworks include key terms such as “all” and “everyone”, among others, and reflect the commitment to “leaving no one behind” as espoused in the Sustainable Development Agendas.

Some of the frameworks this principle is

enshrined in include: Agenda 2063: the Africa we want; the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights; the Common African Position Post 2015 Development Agenda; and the Africa Charter on Democracy.

Even in the face of conservatism, these frameworks set out ambitious aspirations of inclusion that, if read with the liberal intentions of the drafters, highlight the rights of LGBT members of society. They lay the foundation for reasonable social action and progress because they advocate for inclusion in

economic opportunities, justice, equality, repudiation of discrimination, and freedom from arbitrary and unjust treatment. They therefore envisage that all members of society should enjoy this wide array of freedoms.

Notwithstanding the broad and liberal tones of these instruments, they fail to clearly and explicitly mention or recognise LGBT people as a minority group that deserves protection. Not mentioning LGBT people, unlike women, girls, the disabled, people living with HIV, youths, etc., leaves ample room for the discrimination of this group and their continued maltreatment.

But national governments need to step up to the plate. Those that don’t protect LGBT rights must put these guarantees into their domestic laws. They must also then show a commitment to interpreting existing supportive regional instruments broadly and in sweeping terms. A narrow interpretation of the regional policy documents runs the risk of excluding LGBT communities because they aren’t explicitly named in the frameworks.

PRACTICAL CHANGES

State policies, laws and public attitudes have subjected LGBT individuals to exclusion, discrimination and fear. They are daily targets of threats; they face sexual harassment and are prosecuted and persecuted. They are also denied sexual and reproductive healthcare and are seldom protected by state laws and security apparatuses.

In a number of African countries, several legal guarantees sought by LGBT individuals and groups have been adjudicated on the basis of the African Charter. These include the case of Attorney-General of Botswana v. Thuto Rammoge and 19 others. The High Court of Botswana last year ruled that private consensual sex between adults of the same sex is no longer criminal.

Another case came before the Appeal Court in Kenya in 2018. The court ruled against forced anal examinations for gay persons, citing Article 5 of the Charter.

There have also been favourable rulings for LGBT people using the African Charter in Zimbabwe and Namibia.

These rulings also provide the basis for countries developing and implementing policies and programmes that protect LGBT people.

The AU also needs to strengthen the commission’s monitoring mechanisms.

In countries with homophobic laws, the next level of engagement is to translate constitutional and policy stipulations into practical changes for LGBT people to protect them from public and summary punishment by mobs, among others.

Countries with constitutional protection for LGBT people must also ensure that the guarantees actually translate to protection in practice. | The Conversation

COMMUNITY & QUEERPHOBIA

QUEERPHOBIA is everywhere, be it in the most conservative of countries or the most progressive, because people do not understand queerness. There may be spaces or small communities of acceptance but largely we live in an intolerant world.

South Africa is often held up as the exception to the rest of the continent of Africa. We have a progressive Constitution and laws. But those do not keep us safe if they are not implemented or if the people who are there to protect us allow their prejudice to prevent them from keeping us safe.

Queerphobia is a hatred, intolerance, or fear of queer people, much like homophobia and transphobia are the hatred, intolerance, or fear of homosexual and transgender people, respectively. We use queerphobia to be all encompassing of the range of prejudice and discrimination of queer people – which includes lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, asexual, queer and every other person that is outside of the exceptionally narrow cisgender and heterosexual definition of “normal”.

Queerphobia manifests in a number of ways from the language of “you people” or avoiding eye contact to the extreme manifested violence of hate crimes which we have seen continue to grow in South Africa. While I would like to focus on this aspect of queerphobia I believe it is important that we address what is happening within our LGBTQIA+ community.

Queerphobia is not removed from the LGBTQIA+ community, it is within our community. Cisgender lesbian

NYX MCLEAN

and gay people can be biphobic, transphobic and queerphobic. This is often rooted in their need to convince the cisgender heterosexual mainstream that they are “just like them”. We call this assimilationist behaviour or values that ask LGBTQIA+ people to behave and not upset the status quo. To be good gays.

This violence is one that I believe can be the most harmful to all people – cisgender heterosexual, and cisgender and transgender queer people alike. The other forms of queerphobia that manifest are often pinned to this assimilationist value.

Assimilation simply put asks that people present themselves as same and not as different – and if they are different, they are asked to mask, deny, or outright hide and repress that difference. It creates a lot of pressure to conform and to deny a very critical part of oneself – the expression of one’s sexuality and/

or gender identity. Assimilationist values are also rooted in sexism, racism, classism, ableism, and many other forms of prejudice and discrimination. It is a toxic way of seeing the world, and we need to address this urgently.

We need to address this aspect within our LGBTQIA+ community to strengthen our community, and to

understand that we cannot deny people who they are. When we get there, if we get there, we will be better able to do the critical and necessary work of confronting the cissexism and heterosexism that makes queerphobia-based violence possible such as hate crimes.

I suggest this as the way to begin addressing queerphobia in our communities and society because we need a sense of place, of belonging in a world that is incredibly violent towards LGBTQIA+ people. If we create a community that is safe for those within it to express themselves, and to know that they are welcome, we create a space for people to rest and to heal from the trauma of what they experience in their everyday lives outside of the community.

It is important in building a safer LGBTQIA+ community that we ask the community what they need, and to open up organising to include as many people as possible. Often, we see, as is the case with Joburg Pride and Cape Town Pride for instance, that the organising is limited to a few very people who do not represent the needs of the full LGBTQIA+ community. People want to be included and will be there to do the work if they know they are welcome, and they are safe. Building community is not easy work, it needs us to ask the difficult questions, to listen, and to unlearn toxic conditioning. It is not a once-off event, a bringing together of people and declaring it a community, the work needs to be ongoing, and welcoming of new voices and identities as they emerge.

The world we want is possible, but the struggle is long and will take place over decades, as it has before now. We need to find a way to create space for people to rest, to regroup, and to keep on resisting. Building an LGBTQIA+ community that is open and respectful and based on care for all members of the LGBTQIA+ community is integral to this struggle.

Dr Nyx McLean is a transgender non-binary queer researcher who specialises in LGBTQIA+ identities and communities. Nyx holds a PhD in history and wrote their doctoral thesis on Joburg Pride seen through a critical anti-racist queer feminist lens. Pronouns: They/Them.