CHAOS IN THE BU RING CHAOS IN THE BU RING

Mayor Elaine O’Neal’s tenure has been marked by acrimony and scandal on the Durham City Council. Ahead of the municipal elections this fall, voters and leaders are grappling with what’s next.

By Matt Hartman, p. 8

By Matt Hartman, p. 8

ALSOINSIDE: PHOTORETROSPEC T I EV P, 91. ALSOINSIDE: PHOTORETROSP E ,EVITC .P 91

PaRT 1:

Raleigh | Durham | Chapel Hill August 9, 2023

Raleigh W Durham W Chapel Hill

VOL. 40 NO. 26

CONTENTS

6 Durham's participatory budgeting process will be finalized this month.

BY JENNA SPINELLE

8 Ahead of the municipal elections this fall, Durham voters and leaders are grappling with a city council tenure marred by two years of chaos and scandal. BY

MATT HARTMAN

12 Orange County has been swept up in the nationwide cultural clashes over education, and Superintendent Monique Felder is the latest casualty.

BY BARRY YEOMAN

19 INDY40: A photo retrospective. BY NICOLE

ARTS & CULTURE

PAJOR MOORE AND JANE PORTER

34 Mockumentary meets musical theater in the indie comedy Theater Camp.

BY GLENN MCDONALD

BY GLENN MCDONALD

36 A garden tucked behind Chapel Hill's Lantern Restaurant has become a space for small businesses to grow and connect with customers.

BY HANNAH KAUFMAN

38 Artists Derrick Beasley and Pierce Freelon discuss growing up and making art in a gentrifying Durham. BY

MARCELLA CAMARA

40 Cara Hagan's American Dance Festival commission channels chaos at the Nasher Museum of Art. BY

LAUREN WINGENROTH

W E M A D E T H I S

PUBLISHER

John Hurld

EDITORIAL

Editor in Chief

Jane Porter

Culture Editor

Sarah Edwards

Staff Writers

Jasmine Gallup

Lena Geller

Thomasi McDonald

Contributors

Spencer Griffith, Carr Harkrader, Matt Hartman, Brian Howe, Kyesha Jennings, Jordan Lawrence, Glenn McDonald, Nick McGregor, Gabi Mendick, Shelbi Polk, Dan Ruccia, Harris Wheless, Byron Woods, Barry Yeoman

Copy Editor

Iza Wojciechowska

Interns

Mariana Fabian, Hannah

Kaufman, Iris Miller

CREATIVE

Creative Director

Nicole Pajor Moore

Graphic Designer

Izzel Flores

Staff Photographer

Brett Villena

ADVERTISING

Publisher

John Hurld

Director of Revenue

Mathias Marchington

CIRCULATION

Berry Media Group

MEMBERSHIP/ SUBSCRIPTIONS

John Hurld

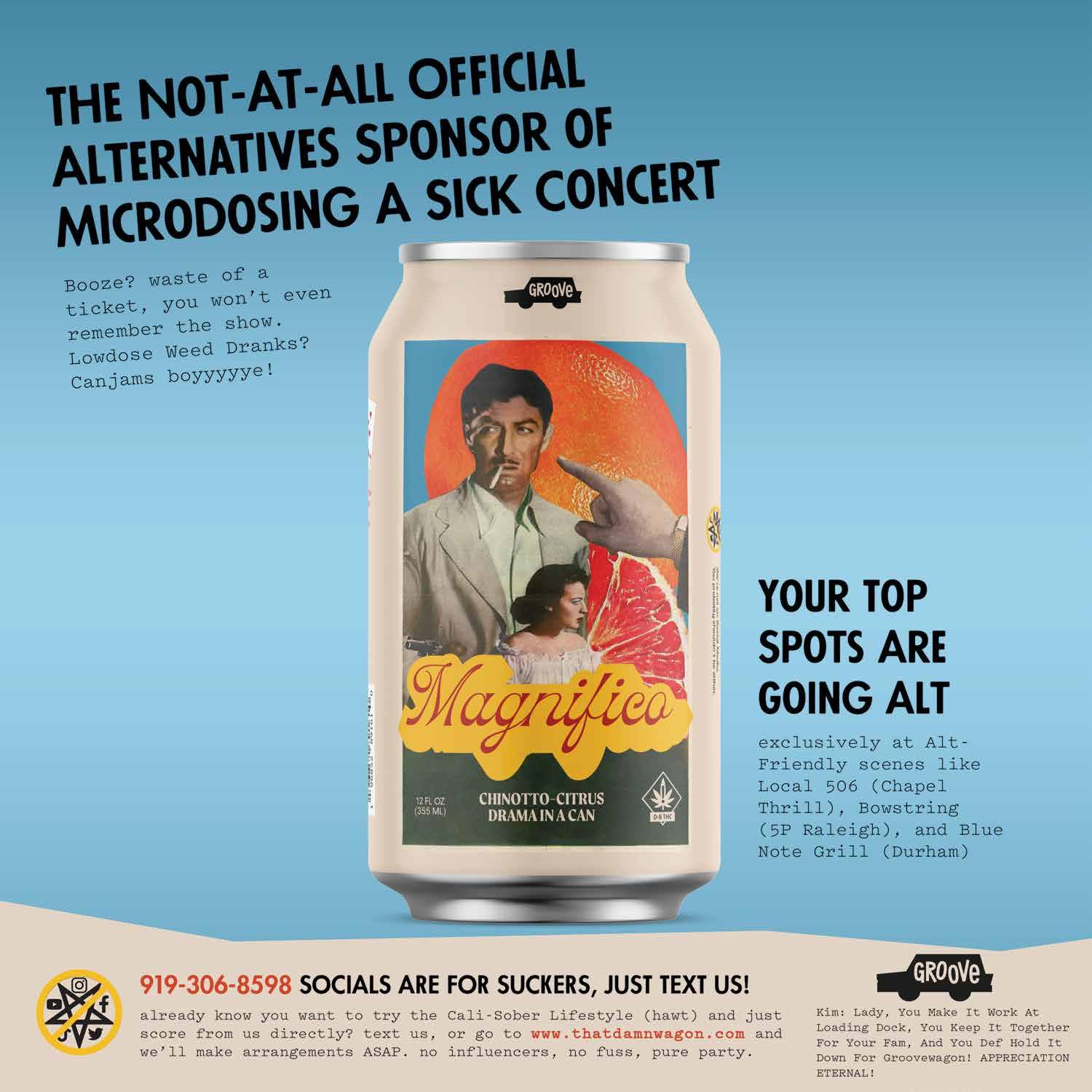

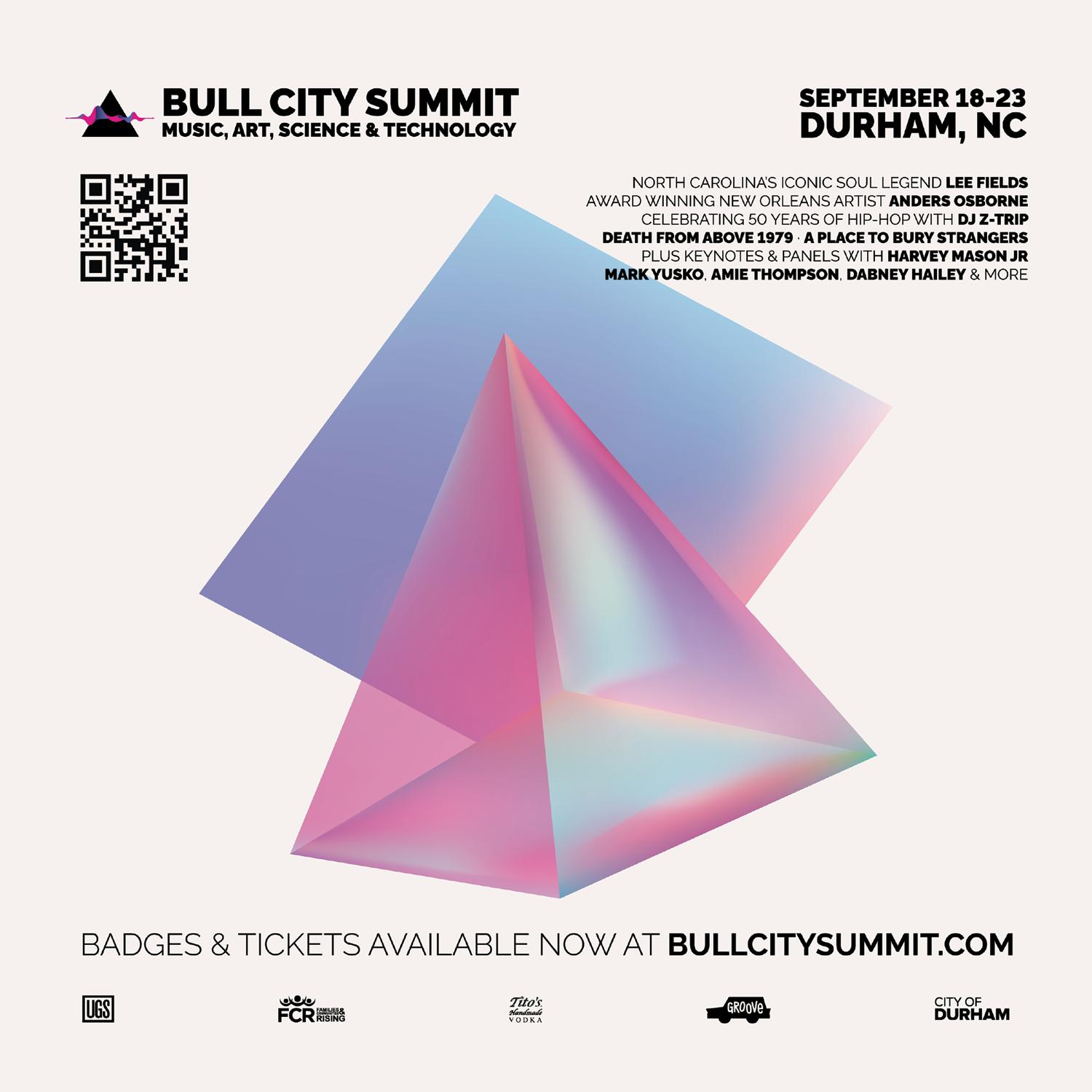

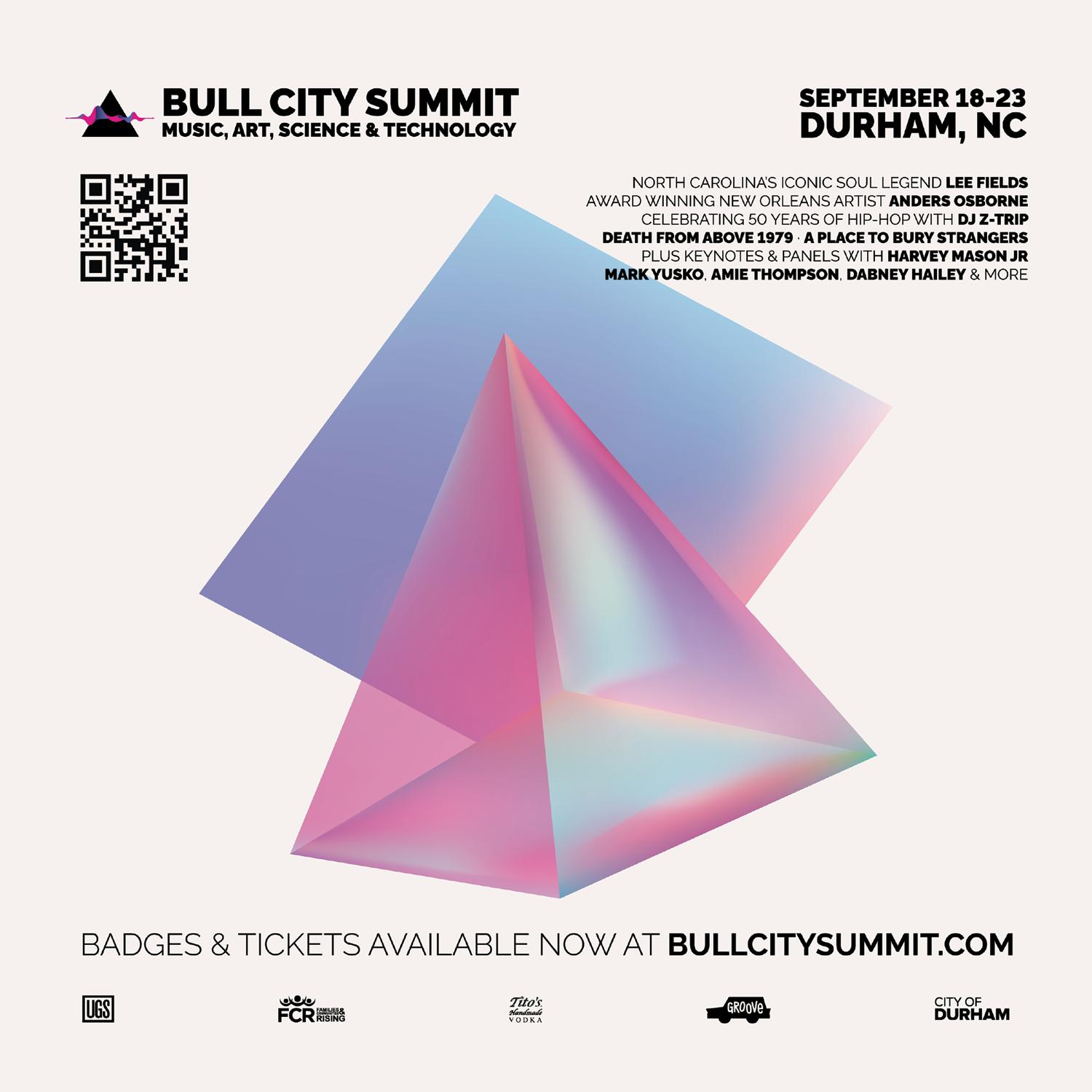

Baylen Levine performs at Lincoln Theatre on Monday, August 14. (See calendar, page 41.)

PHOTO COURTESY OF LINCOLN THEATRE.

COVER PHOTOS COURTESY OF DURHAMNC.GOV OR FROM INDY ARCHIVES. ILLUSTRATION BY NICOLE PAJOR MOORE

INDY Week | indyweek.com P.O. Box 1772 • Durham, N.C. 27702 919-666-7229

EMAIL ADDRESSES first initial[no space]last name@indyweek.com

ADVERTISING SALES advertising@indyweek.com 919-666-7229

Contents © 2023 ZM INDY, LLC All rights reserved. Material may not be reproduced without permission.

2 August 9, 2023 INDYweek.com

NEWS

THE REGULARS 3 Backtalk 4 Op-ed 5 15 minutes 41 Culture calendar

CORRECTION In our Voices column by Thomasi McDonald last week, we incorrectly identified the photographer of his portrait as Brett Villena. In fact, the image was taken by Jade Wilson.

has engulfed Carrboro and Chapel Hill residents and elected officials for more than a decade. We received the following message from Carrboro Town Council candidate JASON MERRILL, who says he is “prodensity and deeply skeptical of developers, especially the large, out-of-state developers that have been plopping garbage buildings all over the Triangle”:

I really appreciated the recent article about the Bolin Creek Greenway because I felt like it was a fair assessment of where we’ve been and where we’re at with a decision that has been surprisingly contentious. Of course, I wouldn’t be writing if I didn’t have a nit to pick so I want to apologize in advance for being “that guy”. :)

I feel that the characterization of the current Carrboro Town Council as “pro-development” is unnecessarily divisive and inaccurate. It would be more accurate to say that they’re actively trying to address the housing affordability crisis, which is a complicated problem that will require a variety of treatments to solve. Part of the solution will be finding ways to increase the supply of naturally occurring affordable housing. Carrboro has been anti-development and anti-density for decades and those attitudes and ordinances have played a major role in the scarcity of high quality affordable housing that we’re dealing with today. The larger question we now must answer is whether we want to slam the door closed in the face of the people behind us who are seeking the same opportunities that we found here, or if we want to hold the door open and make a little more room at the table to share what we love about this place?

Also in our last paper, we bade farewell to staff writer Thomasi McDonald (or McDonald bade farewell to us in his own words in a goodbye column titled “I’m Out, Yo”). Readers told us they will miss McDonald (we all will, too!) as he starts his new job in communications at Duke:

From reader KATHY M.:

Just to say I’ll miss your words. Maybe your old readers will have access to your new words at Duke’s communications office, but if not, maybe the new readers there will provide you with enough time and money to write a book for all of us.

From reader PAM C.:

I’ve read your work at the Indy with much appreciation over the years. Never written a letter, so sorry to learn you’re gone, wish you all good things!

Hope this doesn’t sound rude, but I’m hoping you will write for the chronicle.

From reader BURRELL W.:

I’m a 69 yo mother of 3 adult children! I am proud of my kids but the Mother in me just can’t pass up the opportunity to praise one more! I read, “I’m Out, Yo”. It touched me in a special kinda way!

INDYweek.com August 9, 2023 3 LIMITED TIME OFFER $525 OFF * GET A FREE INSPECTION *Ten percent o any job over $2500 up to a max of $525. Coupon must be presented at time of inspection. O er may not be combined with any other o er. Limit one per customer. Ask inspector for further details. Promo valid through 6/30/2023. HIC#79336 BECAUSE YOUR CRAWL SPACE SMELLS REALLY MUSTY. 877-592-1759 FOUNDATION REPAIR BASEMENT WATERPROOFING CRAWL SPACE REPAIR CONCRETE LIFTING

B A C K T A L K WANT TO SEE YOUR NAME IN BOLD? indyweek.com backtalk@indyweek.com @INDYWeekNC @indyweek

In our paper two weeks ago, writer Cy Neff took a deep dive into the Bolin Creek controversy that

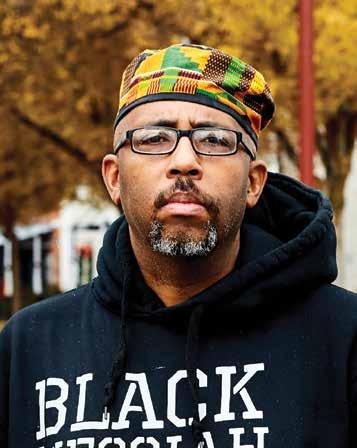

The Glorification of “Gang Life”

BY PAUL SCOTT backtalk@indyweek.com

Professor John Diop Williams, chair of the African American Studies Department of Marcus Garvey University, was in the middle of giving what he thought was a powerful lecture on Black-on-Black violence to a predominantly white middle-class audience when he noticed most of the crowd members were either checking their emails or nodding off. Frustrated, he randomly yelled out, “I’ve never been a stranger to homicide / My city’s full of gangbangers and drive-bys!” From that point on, the suddenly attentive audience hung on every word he spoke until he ended his lecture with an impromptu rendition of “All Eyez on Me.”

While this story is just allegorical (courtesy of watching too many late-night Boondocks episodes), the scenario is familiar to many African American activists working to stop gun violence in our cities.

Back in 1959, there was a tearjerker of a movie called Imitation of Life about a lightskinned Black woman who gained entry into high society by passing for white. However, for the last 30 years, a surefire way to win the attention of middle America, if you are an African American male, is to be an imitator of “thug life,” a term popularized by the late rapper Tupac Shakur.

Recently, I attended a Stop the Violence meeting in Durham and engaged in what I hoped would be a deep conversation with an older white gentleman about a major problem facing our city. As I told him about the books I had read about violence in the African American community from authors such as Amos Wilson and Joyce DeGruy, he wasn’t overly enthused. His only response was, “Yeah, I just finished reading The Hate U Give (T.H.U.G.),” a novel by Angie Thomas.

Like my character Professor Williams, this was not the first time that I have tried to speak to white folk about gun violence only to have my rising crescendo of Black analysis deflated by the condescending question “So what’s it like growing up in the hood?”

The reality is, despite what you see in the movies, most Black men’s first experience with gang life comes courtesy of Hollywood or the music industry, not what we grew up seeing outside our front doors everyday. White America became infatuated with the gangsta lifestyle in the early ’90s as the popularity of groups like N.W.A began to capture the imagination of white Americans who vicariously lived the lives of LA gang members through videos on Yo! MTV Raps. In literary circles, books such as Monster by Kody Scott (who writes under the name Sanyika Shakur) and Dr. Michael Eric Dyson’s Between God and Gangsta Rap made hood stories become the bibles of the Black experience.

It’s troubling that places like Durham have turned the gangsta stereotype into public policy, as the idea that in order to reach Black youth you have to have shot somebody in a past life becomes a dream that million-dollar grants are made of.

are us and we are them. As I walk through Durham neighborhoods every evening passing out free Black cultural books and giving impromptu history lectures to young Black men, I don’t see them as gangbangers. I view them as my brothers in the struggle. As the scholar and writer Dr. Dyson once reminded the audience at a lecture he gave at NC Central University many years ago, Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, Tupac Shakur, and the Notorious B.I.G. all suffered the same fate.

“Nobody” —Nas featuring Lauryn Hill

Although well-funded groups like Bull City United and others that use former gang members to help steer young men away from the vicious cycle of street violence may be well intentioned, it gets problematic when they become replacements for community members who could offer an African-centered, scholarly critique of systemic white supremacy as the root cause of the socioeconomic factors that lead to criminal behavior and who do not pander to white liberal guilt. For those of us engaged in Black radical politics, the degree of separation is not wide enough for us to view the “street cats” as the proverbial “others.” They

Durham, of course, has a history of Black middle-class success. Dr. E. Franklin Frazier, in his book Black Bourgeoisie, wrote in 1957 that at one point the Bull City was “regarded as the capital of the black bourgeois.” But a “get this money by any means necessary” attitude has resulted in a phenomenon that could only exist in a town with this kind of economic legacy. In Durham, this economic ideology has led to a gangsta-ized version of the lumpenbourgeoisie, which embraces middle-class money but rejects its traditional code of ethics. What makes members of this class problematic to a race suffering under systemic white supremacy is that they bypass revolutionary or even reformist ideology and, immediately, join the ranks of reactionary politics. Whether via the black market economy or grants from the nonprofit-industrial complex, instead of fighting the powers that be, they become part of them.

Although there is much said about defunding the police, there is relative silence when it comes to defunding the nonprofit-industrial complex. (Read The Revolution

Will Not Be Funded by INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence for arguments for the exception.) Well-intentioned nonprofits bankroll negative stereotypes of Black men as gangstas instead of functioning as deterrents to crime; they aid in portraying that lifestyle as a necessary step to upward socioeconomic and political mobility.

This is most pronounced during election season when gangsta-ism is used for political leverage. What is sold to politicians and suburbanites is a false ideology known as street knowledge, or what Dr. Bobby E. Wright, in his book of essays The Psychopathic Racial Personality, called street sense, which propagates the idea that there is a sacred code of conduct that only gives someone who has spent at least seven years behind bars the street cred to inspire young Black men to turn away from a life of crime. In these scenarios, street knowledge requires no sociopolitical analysis, just a long rap sheet.

We will never stop the gun violence in the community with politicians and their nonprofit-industrial-complex homies promoting the nihilist idea that criminal behavior is some sort of rite of passage for young Black men. Unfortunately, in order to even enter into the marketplace of ideas, you have to play the role of a ’90s wannabe gangsta rapper.

To borrow from the poet Paul Laurence Dunbar, as Black men in 2023, we wear the mask that grimaces and lies. W

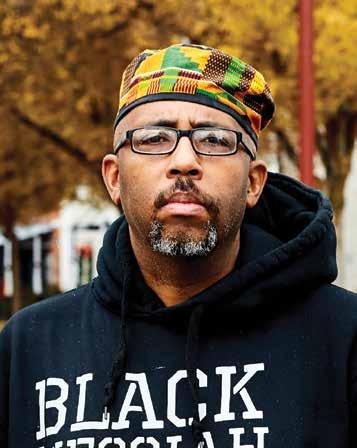

Minister Paul Scott is an activist based in Durham. He can be reached at (919) 9728305, bullcitygriot@gmail.com, or on Twitter at @truthminista.

4 August 9, 2023 INDYweek.com

In Durham, well-meaning residents and leaders are caught up in a narrative that doesn’t fit reality.

O P - E D

“Let me give it to you balanced and with clarity / I don’t need to turn myself into a parody.”

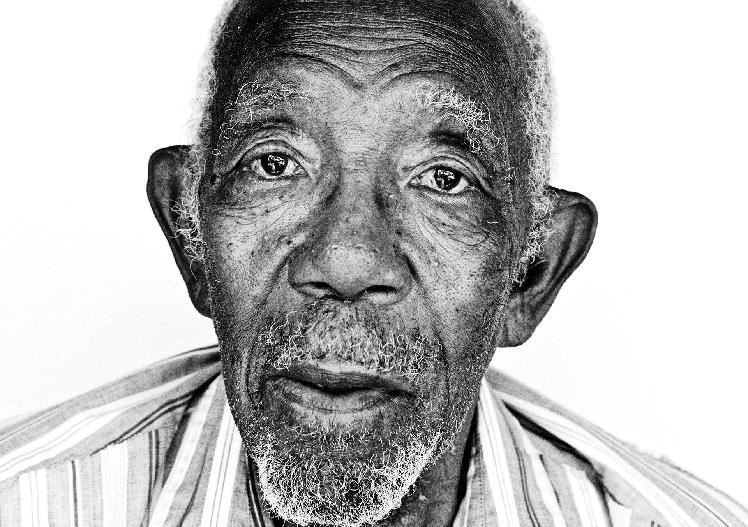

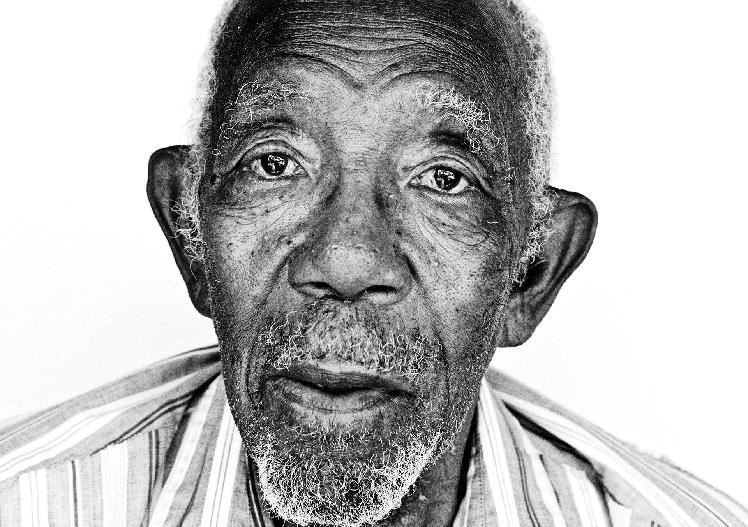

Minister Paul Scott PHOTO BY JADE WILSON

Raleigh

15 MINUTES

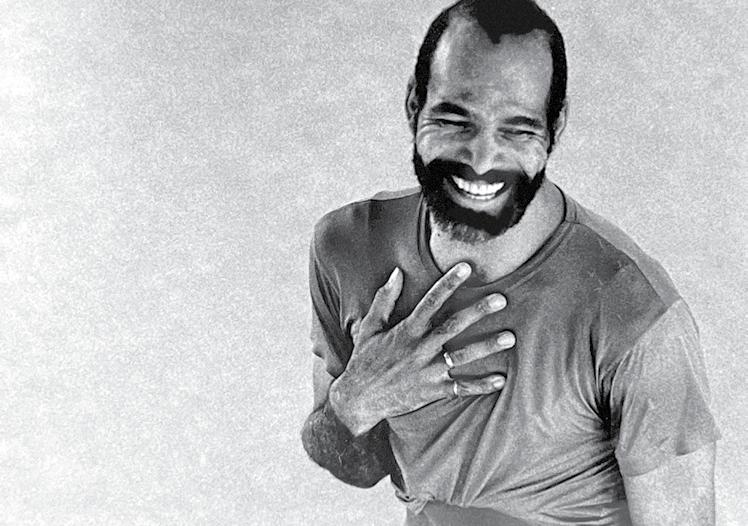

Julius West

Former food truck owner and founder of Sarge’s Sauce

BY IRIS MILLER backtalk@indyweek.com

BY IRIS MILLER backtalk@indyweek.com

How did Sarge’s Shrimp and Grits Sauce come to be?

We’re named in honor of my dad, who was a lifer in the military. We started as a food truck—Sarge’s Chef on Wheels—and our menu was based on all the different places that we’d lived, being a military family. We called our cooking style “down-home cooking, Asian and Caribbean in flair.” We’d lived in Japan, we’d lived in England. My mother’s originally from Charleston. We moved all over the country.

How did you get your start in the professional culinary world?

I grew up cooking with my mother, she loved to cook for people. If you came to our house there was no question: she would not [just] offer you food, she would make it and serve it, put it in front of you. She truly meant for you to enjoy it and she wouldn’t go, “Might you have some?” She made sure that you knew that she meant it was no bother. Living at different bases my mother would run the Noncommissioned Officer’s (NCO) Club. She would run the food service in these different clubs, and so I was

always exposed to that. She taught me that if you work in a restaurant, you can always eat, no matter how broke you are. So I’ve always worked in a restaurant on the side, no matter what my regular job was.

and in 2019 we received our first shipment of our sauce in a jar. We started marketing that from the food truck.

What excites you about the Triangle food scene right now?

It’s just that it’s so vibrant—you do have everything from A to Z, it’s not just a niche of Southern, a niche of this, a niche of that. You have everything from vegetarian to Venezuelan. Certainly tacos, Mexican … but it’s just so wide-ranging. And so well-supported, which is also important.

What is next for Sarge’s?

Did the lessons you learned

working odd

jobs help you with the food truck?

Oh, absolutely. The food business is a people business. I jokingly say I used to sell everything from chicken to lamb. I started in a chicken restaurant when I was real young. Many people have a dream of starting a restaurant based on having a good food product, which you have to have, but we had a good food product and we had a good understanding of how to operate. We were lucky we opened our food truck in 2012, operated for seven and a half years. The menu was based on the different places we’d lived. We had shrimp and grits as our signature dish; hot Italian sausage; a New York dish; cheesesteaks; Northeast; Caribbean jerk chicken; black bean veggie burgers; jerk turkey. And shrimp and grits was our number one dish. People were always asking us how to make it; they couldn’t seem to make the sauce as well. My wife came up with the idea that we should package our sauce so people could enjoy it at home. We did that,

[In addition to our] Shrimp and Grits Sauce, we have our own grits, our own seafood seasoning. We’re working on a couple more products. We like to provide gourmet, restaurant-quality food you can make at home, so we make ways of making it easier for you. We’ll release a lump crab cake mix. Home cooks always want to go to restaurants because they [cook] so well. [It’s] not that the home cook can’t do it, but the restaurant does it all day, every day. Instead of making a recipe once, we may have made it 5,000 times. So we’re better at it, we like to take the edge of that kind of experience and make it easy for the home cook to duplicate.

Do you have any advice for parents that want their children to have a passion for cooking?

My mother’s favorite saying was “If one eats, one oughta know how to cook.” It’s as simple as that. We’ve always been family-oriented. I’ve gone through some trials and tribulations, my wife has always hung in there with me. We’re coming up on our 44th year of marriage. We’ve been through a lot, but we’ve always stayed together and we keep at it one step at a time. W

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

INDYweek.com August 9, 2023 5

Julius West PHOTO COURTESY OF PUBLICITY FOR GOOD

Power to the People

Durham’s third cycle of participatory budgeting will be finalized this month.

BY JENNA SPINELLE backtalk@indyweek.com

When parents from Book Harvest stood behind tables at the Child Care for NC event at the North Carolina General Assembly in April, they were there in part because of funding that came from their fellow residents in Durham.

Book Harvest, a Durham-based children’s literacy organization, was chosen for funding as part of Durham’s participatory budgeting program. The city began using participatory budgeting in 2018 and has since awarded nearly $3.5 million in city funds to projects chosen by residents. A third cycle that will allocate $2.4 million is currently under way, with funding decisions expected in August.

Book Harvest received $40,184 from Durham’s second participatory budgeting cycle in 2021. Amy Franks, the organization’s associate director of school and family engagement, says the funds were used to hire parents to work as ambassadors. Parents set up tables at neighborhood events, built a parent-to-parent network, and held events that allowed parents to connect with one another.

“We wanted to shift the power and decision-making to parents and have them at the table from the beginning, rather than decisions being made for them,” Franks says. “We were at grocery stores and laundromats and parks and bus stations so that we could make sure the parents were aware of things that we were doing and to bring them to the table so that ultimately

they are leading the charge.”

In many ways, what Franks articulates about Book Harvest’s use of participatory budgeting funds is similar to the overall goal of participatory budgeting—to shift the power of the purse away from a small group of elected officials and city staff and to the residents. As organizers in Durham and Greensboro have learned over the past decade, it’s a goal that’s sometimes easier said than done.

What is participatory budgeting?

Participatory budgeting, often referred to as “PB,” began in Brazil in 1989. Since then, it’s been adopted by thousands of cities, school boards, and other institutions striving to give stakeholders a direct say in funding decisions. PB is part of a larger set of reforms known as direct democracy that aim to give greater decision-making power to people who are not elected officials.

The PB process typically involves residents forming a steering committee to create the rules and an engagement plan to develop ideas for projects that the community wants to fund. Volunteer budget delegates from across the city turn those ideas into concrete proposals that residents vote on. The city government then funds the winning projects from the overall pool of PB-allocated money.

Hollie Russon Gilman, a fellow in politi-

cal reform at the New America think tank and author of Democracy Reinvented: Participatory Budgeting and Civic Innovation in America, studies participatory budgeting and its impacts. She says PB’s impacts extend beyond the immediate funding decisions of individual projects and lead to a greater appreciation for how local government operates.

“People are signing up to become budget delegates, which is my favorite part of the process because you get to really see how this sausage is made,” Russon Gilman says. “And then those proposals get turned back to a wider group of residents for a vote. One of the great things about participatory budgeting is that it’s more inclusive than traditional elections. So non-citizens, young people … we’re seeing some places as young as 11 or 12 are eligible to vote.”

Greensboro: PB comes to North Carolina

Greensboro was the first city in North Carolina—and in the South—to implement participatory budgeting, which it did in the 2015–16 budget cycle. Conversations about bringing PB to the city began in 2011 and were led by the Fund for Democratic Communities, a progressive local organization.

Audrey Berlowitz, a teacher and doctoral candidate at the University of North Carolina Greensboro, joined the movement

that brought PB to Greensboro through her friend Marnie Thompson, who founded the Fund for Democratic Communities with her husband, Ed Whitfield.

Berlowitz visited Chicago to see PB at work and was inspired by what it could mean for more democratic city politics. PB has the potential to reduce the influence from what she describes as the “technocrats and bureaucrats” on the city’s council and staff.

“It seemed like a very open-ended, fluid thing,” Berlowitz says. “And then it became interesting to discover people here wanted that. We also had to work to understand what kind of projects we could get through PB that would be approved by the city staff.”

After years of lobbying from Thompson, Whitfield, Berlowitz, and others involved in the Fund for Democratic Communities, the Greensboro City Council approved PB in 2014. It passed with a 5-4 vote. Those who opposed it cited overlap with existing neighborhood assemblies and unnecessary spending to bring in the Participatory Budgeting Project from New York City to act as consultants for the first round.

The steering committee report from that first year called the PB implementation a success at generating ideas and involving all parts of the community, but it noted communication breakdowns between the steering committee and city staff over vetting project ideas before putting them up

6 August 9, 2023 INDYweek.com N E W S Durham

Book Harvest associate director of school and family engagement Amy Franks (center) at a Book Harvest event.

PHOTO COURTESY OF BOOK HARVEST

for a vote, as well as difficulty reaching young people and non-English-speaking communities.

Greensboro PB ran three additional cycles, in the 2018–19, 2020–21, and 2022–23 budget cycles. Projects funded included the Hopper Trolley, a free transit service that operates Thursday through Sunday in downtown Greensboro.

Durham: Focus on equity and inclusion

Durham began its own journey with PB when the city’s former manager learned about what was happening in Greensboro. Today, Andrew Holland, Durham’s assistant director for strategy and performance, is part of the team that leads PB in the city’s Office of Performance and Innovation.

“Our former city manager had communicated to us that he wanted the PB program to be a true reflection of Durham,” Holland says. “And with our city council, especially during that time and even now, there’s a focus on equity. Everything that we do as a city, it needs to be equity focused. So how we went about designing our outreach and communications plan, it was targeted to those underserved neighborhoods.”

Holland says Durham’s PB team and volunteers knocked on doors and visited bus stations to engage underrepresented groups. They also made voting available on paper and iPads to accommodate varying comfort levels with technology.

One advantage of PB, advocates say, is that it gives residents a chance to present ideas that might seem trivial but have a large impact on day-to-day life, like which plants and shrubs should be part of their neighborhood’s landscape or what kind of equipment a playground should have. Holland says this is exactly what happened with the city’s Belmont Park and Drew/Granby Park.

“It was a very interactive exercise in which we wanted to make sure that the people who voted for the project had the opportunity to weigh in on what the park should look like,” Holland says. “We wanted the project to be a true reflection of that community.”

PB also caught the eye of Durham City Council member Jillian Johnson. She made implementing PB one of her priorities and served on the PB steering committee.

“I’ve always believed that having more people’s voices at the table is really critical. No one should worry about not having enough experience in politics,” Johnson, who will retire from the council at the end of this year, told Elle magazine in 2017. “I didn’t have any experience in elected politics, and I did it. I’ve learned that many

different kinds of life experience translate well into what you need to know to be in an elected office.”

Former Durham mayor Steve Schewel learned about PB from Johnson. He says he was skeptical at first but came around once he saw the process in action.

“I was a big believer in Jillian and had a huge amount of trust in her, and she convinced me to give it a whirl,” Schewel says.

“I’m very glad that happened, and it’s proven to be a good decision.”

Schewel says he knew that staffing would be essential to making PB work and committed additional funds to add staff to the budget office, including the position Holland now holds.

Schewel says some of the projects completed as a result of PB—including park enhancements and other public works projects—likely would have happened anyway but it was important to have community buy-in.

“It was gratifying to me that we got the increased democratic participation and

“What’s great about it is all of these organizations, whether they get voted for or not, are having a platform to share what they do. So even the process itself, by informing the community about these various organizations and initiatives, it’s already doing great work.”

What the future holds for PB

Voting for Durham’s third PB cycle will begin in September. The process, however, appears to be on hold in Greensboro. On July 11, the city sent an email to its PB supporters saying the 2023–24 budget did not include funding for the projects approved in the most recent PB cycle, and the program will be reevaluated before it continues.

At the same time, North Carolina’s legislature continues to make changes that impact voting rights and civil rights.

“Democracy is getting smaller in North Carolina,” Schewel says. “We have to do everything we can at the local level to ensure access and participation. PB has been a great tool for democratizing the budget process, which is the most important thing we do in local government.”

The Participatory Budgeting Project continues to work on PB processes in Seattle, New York City, Cleveland, and other cities across the country. But at a time when the political stakes feel so high—especially in North Carolina—is pursuing PB worth the time and energy?

Berlowitz says she thinks about this a lot, both in her efforts to bring PB to Greensboro and her current work to unionize faculty at UNC Greensboro.

opened up access to our budgeting process,” Schewel says.

Book Harvest’s Franks, a Durham resident, voted in Durham PB and says she saw equity at the forefront of the process.

“I put this question to a colleague and I agree wholeheartedly with what she said …. Participatory budgeting is about equity and justice,” Franks says. “It’s by the people, for the people.”

Benay Hicks, Book Harvest’s associate director of communications and marketing, says the organization is often asked to participate in fundraising challenges or competitions that pit nonprofits against one another as people vote on which organizations to fund. She says Durham PB had a markedly different tone that she observed felt true to the goal of gauging what the community truly wants rather than which organizations put on the splashiest marketing campaigns.

“It felt like we were all on one page. Nobody was bashing anybody, and nobody was being obnoxious about it,” Hicks says.

“Our supermajority Republican legislature is introducing really draconian laws, culture war laws,” Berlowitz says. “We need some power to push back against it, and we’ve got to figure out how to organize for power.”

Russon Gilman also hears this question a lot in her work studying PB. She says a common theme across cities that implement PB is that people feel more connected to their communities, which can be the first step toward building political power and a way to combat America’s loneliness epidemic.

“What’s the alternative? Is the status quo going so well? Are there a lot of people who still think America is a beacon on a hill and our democracy is thriving?” she says. “You don’t need to be a political scientist to think that we have some problems. If you ask people, across both sides of the aisle, they’re very disaffected with their institutions.” W

For more information about Durham PB, visit pbdurham.org. For more information about Greensboro PB, visit pbgreensboro.com.

INDYweek.com August 9, 2023 7 Wka e up withus Local news, events and more— in your inbox every weekday morning Sign up: INDY DAILY SIGN UP FOR THE

“Participatory budgeting is about equity. It’s by the people, for the people.”

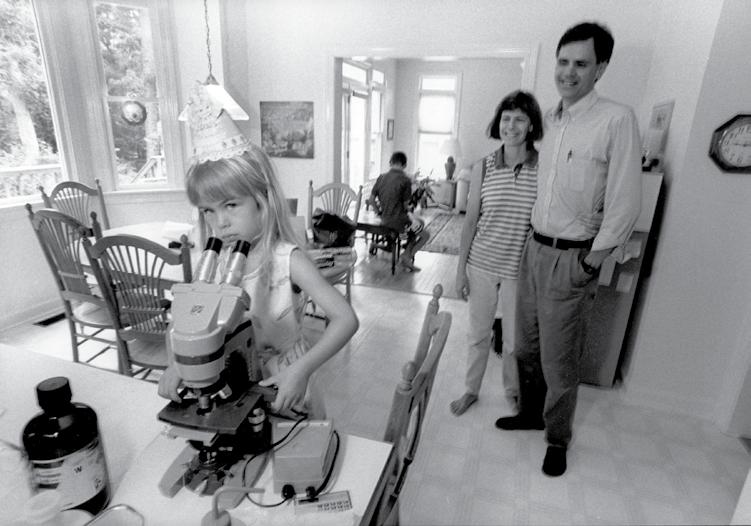

Chaos in the Bullring

Mayor Elaine O’Neal’s tenure has been marked by acrimony and scandal on the Durham City Council. Ahead of the municipal elections this fall, voters and leaders are grappling with what’s next.

BY MATT HARTMAN backtalk@indyweek.com

Leo Williams leaned back in his chair, a hand over his eyes. Jillian Johnson, his colleague on the Durham City Council, had just introduced a resolution to censure their council colleague Monique Holsey-Hyman over allegations that she improperly used city staff’s time to work on her fall election campaign.

“We didn’t really discuss who was going to introduce it, so I will step up and do it,” Johnson said near the end of a contentious March 23 work session. The move came after Mayor Elaine O’Neal read a letter revealing allegations of corruption against an unnamed council member (identified also as Holsey-Hyman, four days later) at the beginning of the meeting.

All of the council members seemed tired.

Maybe they were worn down following the shooting of three teenagers the day before. Maybe it was the brewing debate over the controversial SCAD proposal. But no one, current mayoral candidate Williams included, was having an easy time.

“As you disrespect us, we have a right to come up here and disrespect you as well,” James Chavis, a public speaker, said to the council from the chamber’s floor. It wasn’t the only public comment in that vein.

Holsey-Hyman, on the verge of tears, defended her record. Williams said he was confused about whether they were debating the facts of the case against Holsey-Hyman or just the resolution to censure her. O’Neal spoke like a stern parent, chastising an unnamed council member for allegedly using her signature without permission—a reference to Johnson that foreshadowed a preoccupation from the mayor that would reemerge in the summer. (Johnson said later that she had merely included a blank line for O’Neal to sign if the resolution passed.)

Council member DeDreana Freeman, also a mayoral candidate, and mayor pro tem Mark-Anthony Middleton exchanged barbs, with Freeman saying she was “angry and

disgusted.” She blamed sexism for the way her colleagues dismissed Holsey-Hyman’s explanations.

“As one of the two men on this board: What? What does that even mean,” Middleton retorted, giving Freeman an exaggerated side-eye.

“Stop being a bully,” Freeman replied off mic.

Then came the real fireworks.

WRAL cameras caught audio of Freeman launching a profanity-laced verbal tirade at Middleton after the meeting adjourned. Two eyewitnesses told the INDY that Freeman also took a swing at him, missed, and hit Williams and O’Neal, though a local pastor said no punches were thrown.

The day’s embarrassing events are the most dramatic evidence of the tension, conflict, personal disdain, and conspiracy theories that have been roiling Durham politics for at least the past four years.

Amid a world historic pandemic and a national racial reckoning, O’Neal, Williams, Middleton, and Freeman won their elections in 2021 with broad public support to shift Durham’s response to a spike in murders and an ever-deepening housing crisis.

Less than two years later, community trust is in tatters and confidence in the council is flailing.

Despite marquee achievements like expanding an unarmed first response team and introducing a $10 million fund to improve Fayetteville Street, this council’s tenure is best known for scandal.

Durham politics has become a morass of bitterness and resentment. Policy discussions are rancorous, government staff are often left confused, and much of the voting public seems disoriented and dispirited. Many worry the results will harm the city’s reputation, give investors second thoughts, and scare away potential public servants.

“You couldn’t pay me enough to run for office right now,” former council member Charlie Reece tweeted about the environment in March.

“I’m going to go public about seeking therapy, because I saw what it did to me as a person,” Williams tells the INDY “I saw what it did to me and my family.”

As the city heads into municipal election this fall, the INDY is launching a four-part investigation into what brought Durham to this point, how it’s impacting local government responses to the pressing issues of crime and gentrification, and what comes next.

How it began

O’Neal’s late-2020 announcement that she would run for mayor was meant to be a unifier in an increasingly fractured Bull City. “Durham for Everyone. United. Not Divided. Grab hands and let’s move forward into a bold and bright future for all of us,” went one campaign slogan.

So long the maligned bronze medalist of the Triangle, Durham spent decades trying to attract new capital and investment. For much of former mayor Bill Bell’s long tenure, the city’s urban center was the focus.

“We had to build up confidence in the community,” Bell says in the conference room of UDI Community Development Corporation, the nonprofit he still runs. Sepia-toned photos of the company’s long history cover the walls, and a tube TV plays the news from its mounted place in the corner of the room.

“We could do something in a positive way, and the biggest showcase, for me, was ‘What could you do in downtown?’” he says.

By the time Bell stepped down in 2017, the effort had largely succeeded. The foundations for Durham’s tallest building, One City Center, were being laid. When it opened in 2018, construction cranes simply moved across the skyline to new projects.

But for many in the predominantly Black and brown

8 August 9, 2023 INDYweek.com

NEWS Durham

PHOTO ILLUSTRATION BY NICOLE PAJOR MOORE

neighborhoods surrounding downtown, the changes were more threat than success. The pandemic decimated jobs and support networks; violent crime rose, incomes fell, and many wondered if they would still have a place in the new Durham.

“There’s quite a few people in city government that really want the problem to disappear, which is the materially poor Black and brown people that are embarrassing them and making their lives difficult,” says Camryn Smith, cofounder and executive director of Old East Durham’s Communities in Partnership.

Though the downtown-centric approach started under the moderate Bell, who is Black, its success became particularly visible under the progressive councils that succeeded him, starting in 2017 and led by Mayor Steve Schewel, who is white.

Many critics placed the blame squarely on the progressives. Smith points to research by former NC Central University business professor and current U.S. Department of Energy official Henry McKoy showing that racial disparities are higher in blue counties than red ones.

“Right now, Durham is nothing close to what it says it is in terms of a city that thinks highly progressively, where we want a lot of diversity, a lot of different ways of being, a lot of different thoughts,” Smith says. “I don’t think that’s who we are, to be honest with you.”

The racial divide began to sour local politics as the city went into the 2019 election. Javiera Caballero became the first Hispanic council member in Durham’s history when she was appointed the year before, but the Durham Committee on the Affairs of Black People (DCABP), one of the city’s oldest political organizations, objected to the fact that Schewel had “expressed a preference for the appointment of a Hispanic or Latino applicant.”

Caballero solidified a progressive council majority alongside Schewel, Johnson, and Reece, who often voted together for their shared priorities. But many of Durham’s most prominent Black activists—often, though not exclusively, moderates connected with the DCABP—saw their votes not as a democratically endorsed mandate from voters but as an elitist bloc that cut out the people already excluded from Durham’s prosperity.

When Caballero, Johnson, and Reece ran together in 2019 as the Bull City Together slate, opposition intensified. Johnson became a particular target of criticism.

“When we went through that whole crisis, we never saw Jillian,” says Ashley Canady, a tenant leader at McDougald Terrace, referring to the time in 2019 when the Durham Housing Authority complex was evacuated due to carbon monoxide poisoning. “She has not been around, she has not been seen. That is my biggest issue with her: she is not in

community at all.”

Johnson, in response, says no matter what one does as a public official, it’s impossible to avoid criticism from opponents.

“If you show up, they call you an opportunist,” she says. “If you don’t, they say you’re disconnected from the community.”

Still, there’s plenty of criticism to go around.

“When this bloc came together, the unfortunate part about it—in my belief, from the people I talk to—is that they were only going to be accommodating of a certain segment of the population of Durham,” says former council member Jackie Wagstaff. “And that would most likely be people that agreed with them. The other people: you’re on your own.”

The distrust grew so large that the year’s now infamous People’s Alliance (PA) endorsement meeting launched a fight about whether someone used a Nazi slogan. (The People’s Alliance, a four-decades-old grassroots political organization, is also one of the city’s most influential PACs.) In the end, the progressives won the endorsements and the election, completing a decade in which only a single municipal candidate endorsed by the historically white PA lost.

Though the progressives passed major pieces of ambitious, popular legislation aiming to combat the inequalities plaguing Durham—including shepherding a $95 million housing bond, at the time the largest housing bond in North Carolina history, through a public referendum in 2019 and launching the Department of Community Safety two years later—the racial battle lines became entrenched.

“Something was lost in that election cycle that took a long time to build,” says the Latino filmmaker and activist Rodrigo Dorfman, who played a central role in the endorsement meeting brouhaha.

Some criticisms of Johnson and other progressive Black figures also veered into claims that they weren’t “really” Black, say many PA supporters.

“Durham has been treading dangerous territory in terms of questioning the Blackness of our Black leaders like [Johnson] based on notions that themselves are deeply rooted in white supremacy,” says Nana Asante-Smith, chair of the PA PAC.

That was the Durham O’Neal was elected to unify—one in which accusations of racism abounded as murder rates rose, income inequality grew, and housing costs soared.

After Schewel announced he wouldn’t seek a third term, O’Neal swept into office with nearly 85 percent of the vote, facing only a last-minute challenge from Caballero, who suspended her campaign after the primary.

Freeman, Middleton, and Williams all won DCABP endorsements, and only Middleton had also received the PA’s support. Their ultimate victories were a clear statement that Durham voters wanted a change.

Though much of the campaign focused on debates over moderate and progressive approaches to police reform, O’Neal’s popularity had less to do with any policy position than with her relationships—particularly with the people who felt shut out by the progressive majority.

“It’s her history with the community that made people trust her,” says Wagstaff. “She’s always been that type of person that you can have confidence in. People knew her and trusted her, and that’s what we wanted to see up there.”

What they’ve done

After a scandal-plagued two years, the people who most wanted a change find themselves deeply disappointed.

“The Black community in particular had high hopes in the leadership, given that you were electing the first African American female mayor,” says Bell. “And it turns out six out of the seven council people were African American. I just think it was felt there was going to be more cordiality among the council members in terms of getting things done. At a minimum, people thought the mayor and the mayor pro tem [Middleton] would be on the same page.”

The disappointment doesn’t mean O’Neal’s backers blame her, however. One of the new divides in Durham politics is about whom to blame for the divides on council.

According to O’Neal’s staunchest supporters, she and her allies Freeman and Holsey-Hyman were undermined and made to look weak and ineffective by an oppositional majority composed of the other four.

But the obvious fact is that a majority vote in an elected body is not a nefarious plot. It’s the way democracy is supposed to work.

The majority isn’t actually a majority, either. There are also divisions between the progressives, such as Caballero and Johnson, and the moderates, such as Williams and Middleton.

“The four of us who vote to approve housing developments do it for somewhat different reasons,” Johnson says. “It’s not like a pro-business ethic that gets me there, where for other folks it might be. So what looks like a voting bloc is actually people coming together across difference.”

The allegations against Holsey-Hyman suggest that such political differences are only partial explanations, though. Simply, some council members just don’t like each other.

Most troublesome for DCABP activists and others who cheered the 2021 election returns is that the most vicious fights haven’t been between the moderates and the progressives, but among the moderates. Freeman yelled at Middleton, after all, not at Johnson.

The explanations for the acrimony quickly devolve into conspiracy theories that wouldn’t be worth considering if they weren’t amplifying the hostility among elected officials.

The theories range from mundane political ambition (that Middleton hoped to be mayor), to baseless allegations of corruption (that Williams is being paid by developers), to outlandish and convoluted setups (that Middleton manufactured the claims against Holsey-Hyman as punishment for not voting with him).

The source for most of them—by her own admission—is Wagstaff.

INDYweek.com August 9, 2023 9

“Right now, Durham is nothing close to what it says it is in terms of a city that thinks highly progressively.”

“The Black community in particular had high hopes in the leadership, given that you were electing the first African American female mayor.”

“I believe that Mark-Anthony Middleton orchestrated this,” she says. “If he were standing here looking at me, I would tell him that. I’m not one of those people that’s going to sit around and throw a rock and hide.”

An effective organizer with deep ties to various Black communities across Durham, Wagstaff also has a history of controversy over her long political career, including being censured and suspended by the DCABP in 2013 for being “insubordinate, uncollaborative, and extremely impolite.”

But she remains a close and prominent ally of O’Neal, Freeman, and Holsey-Hyman.

“It’s just nonsense,” Middleton says. “And unfortunately, some of it is being driven from the dais, which should be the paragon of sensibility and rationality and the chief brand ambassadors of our city.”

Middleton even wrote an email to his council colleagues in March alleging that “one or more members of the city council” shared a claim that “meets the legal standard of slander” with “prominent members of the Durham community.”

If O’Neal, Freeman, and Holsey-Hyman have retained support, it’s largely among those who believe the unflattering media reports and allegations are untrue. Instead, those supporters believe they are just another example of the long-running sexist and racist status quo.

“It bothers me that everybody is so quick to pathologize a Black woman, but then they want to have Black Lives Matter signs in their yard, and then they want to say #TrustBlackWomen,” says Smith, the East Durham activist and a Freeman ally.

“There’s a lot of people that know DeDreana in this community,” she adds, pointing to the conflicting accounts of Freeman’s altercation with Middleton. “We’ve never seen her hit or do that, so why did you believe that so quickly? Because of the trope of the angry Black woman.”

“What folks try to label as toxic,” Freeman says, “is the discomfort they feel when people challenge their racism, their sexism, all of those -isms.”

Because Middleton, in particular, has grated on his political opponents, the response has found purchase in some parts of Durham.

A dominant force on council—he received more votes in the 2021 election than anyone else—Middleton is prone to long speeches and sharp rebukes such as the eight-minute explanation he gave at the March 23 work session of what a censure is and isn’t and the need for moral rectitude on council.

Opponents have found such rhetoric more fitting for the church he pastors than for council chambers, and Freeman was not the first to call him a bully.

“There’s that saying, ‘Everyone can’t tell the same lie,’” says Whitney Maxey, executive director of the progressive group Durham for All. (Disclosure: I was formerly a volunteer member-leader with the group.)

Middleton, for his part, thinks he’s just doing his job by asking “pointed” questions. “Some of those meetings where I’ve been accused of talking down or putting people on trial? I think that was due diligence,” he says. “I think it would have been malpractice for me not to ask.”

With three divided blocs, allegations of federal crimes, and a populace growing desperate, the council was in clear need of a leader—someone who could unite the various factions, or at least keep the conflict behind closed doors.

O’Neal proved incapable of the task.

Sources inside city hall report that members from each

bloc barely speak to the others outside of public meetings. While past mayors Schewel and Bell would act as facilitators for the everyday work of governing, O’Neal doesn’t hold regular one-on-one meetings with most council members. Instead, she approaches the work the same way she approached her time as a judge and law school dean: by trying to build community relationships.

Other council members were left in the dark about key efforts, like her attempt to negotiate a truce among gang members.

“I have no idea,” Johnson says about it. “She did all that on her own.”

The approach allowed divisions to deepen and conflicts to fester. Then they’d explode into public view, like with the clear confusion over whether the council would censure Holsey-Hyman, whether they were voting on the resolution at all, and who had approved the draft language, or with this summer’s surprise vote on additional raises for firefighters and police officers at the start of a heated budget meeting.

That siloed, suspicious environment helps explain the quixotic quest against Wikipedia that O’Neal, Freeman, and Holsey-Hyman launched to reveal who was adding unflattering details—or a simple signature, in O’Neal’s case—to

itics are undergoing a generational shift that such segregated networks can’t manage.

For decades, the city’s two most influential political organizations—the progressive, historically white People’s Alliance and the moderate Committee on the Affairs of Black People—negotiated political power along Black-white racial lines.

“In the old days,” Johnson explains, “they would meet up for fried chicken and decide who were going to be the city council members.”

Today, a cohort of younger activists—including Black and Latino activists—are diversifying the PA and pushing it in even more progressive directions.

But the PA still has prominent skeptics who believe the organization’s many leaders of color are little more than figureheads. The membership, they believe, represents a subsection of Durhamites who are wealthier and whiter than the city as a whole.

“It would be really nice to see them shift,” Freeman says. “Equity is more than tokenism. It’s not just the loudest voice in the room. It should actually be something of substance. The identity-politics era needs to go.”

For those PA leaders, though, such criticisms amount to complaints from those who didn’t get the PA’s influential backing.

“The reality is PA—supported statistically and with data—has truly evolved in its membership as it pertains to age, race, and engagement, to name a few characteristics,” says Asante-Smith, the PA PAC chair.

But even if the PA is replacing a largely white old guard with a more diverse group of young members, it still represents a particular social group—as does the DCABP. Half of the PA’s current leadership are alumni or employees of Duke, and only one has ties to NCCU. The ratios are nearly perfectly inverted in the Committee’s leadership. Working-class people are often left out of both.

“The history of Black Durham is highly stratified by class, by color, by education, and by which family you came from,” says Smith.

their biographies. The broken trust is undeniable.

Only Williams was able to maintain cordial relationships across all three council blocs for any length of time, often acting as the point of contact between them. Holsey-Hyman even noted that he was the only council member to call her before the March 23 work session (though she missed the call).

What comes next

Now, O’Neal is leaving office after a single term. The long-serving Johnson is leaving too. Holsey-Hyman is running to retain her council seat but with an ongoing State Bureau of Investigation probe hanging over her. Freeman and Williams are rivals in the mayoral race, and, whatever happens this fall, they’ll still have to work together on the next council.

In the midst of such chaos, all sides are relying more heavily on the network of people they already know. Who better to trust than the people you already work with, who talk like you, went to the same school you did, live in the same neighborhood?

But the fundamental issue is that Durham’s racial pol-

The tragedy of it all is that nearly every person involved in Durham politics agrees that nothing can be solved by Durham’s government alone. No amount of power the PA or the DCABP can gain will be enough to meet their agendas, which require organizing for state-level policies as well. And all the recent controversy, toxicity, and scandal risk a crisis of confidence that undermines efforts to build toward larger political change.

“In an institution of public trust, maintaining that public trust is the most important thing,” Johnson says. “If someone does something that violates the public trust—regardless of who they are—a transparent and robust response is necessary or you risk the integrity of the entire institution.”

After roughly 40 minutes of bickering, hectoring, and occasionally speaking to the issues at hand, O’Neal brought the March 23 work session to a close.

“These are the people you elected, Durham, and it’s up to you to hold everybody accountable,” she said. “We should be ready for that, whatever that looks like.

“I don’t know where Durham is poised and where it is going, but I do hope that Durham city is paying attention to all of us.” W

This is the first story in a four-part series covering Durham’s upcoming municipal election

10 August 9, 2023 INDYweek.com

“In an institution of public trust, maintaining that public trust is the most important thing.”

INDYweek.com August 9, 2023 11

Schoolyard Brawl

Orange County has been swept up in the nationwide cultural clashes over education, and Superintendent Monique Felder is the latest casualty.

BY BARRY YEOMAN backtalk@indyweek.com

BY BARRY YEOMAN backtalk@indyweek.com

Monique Felder peered through the tall windows, studying the dozens of demonstrators outside A.L. Stanback Middle School in Hillsborough. Even though their voices were muffled by the glass, she could hear their agitation.

She considered whether they might rush the building, where the Orange County Board of Education was discussing the rise of white nationalism. She hoped the police could contain them if they did. She wondered if she, the school district’s superintendent, was safe.

It was October 2021: a tense time for a district in the maw of the culture war. The previous month, a group that included the Proud Boys, an organization linked to the Capitol insurrection, had assembled with flags and a bullhorn near the entrance to an Orange High School football game. They called for an end to COVID-19 vaccine mandates for students (though none existed) and masking rules, and for the deaths of those who disagreed.

Lt. Gov. Mark Robinson’s office, meanwhile, had singled out Hillsborough’s Cedar Ridge High School library for carrying Maia Kobabe’s memoir Gender Queer. The book, written in graphic-novel format, chronicles the author’s coming out as nonbinary and contains panels depicting adult sex.

“There’s no reason anybody, anywhere in America, should be telling any child about transgenderism, homosexuality, any of that filth,” Robinson, a Republican, had said.

Now, protesters had descended on the board meeting. Several signed up to comment on the math curriculum but instead used the microphone to claim the board was promoting antiwhite “racism” or seeking to destroy America. Gretchen Schmid, chair of the local Moms for Liberty chapter, signed up to discuss masking policy, then accused the board of working alongside its “antifa allies” to silence students and parents who opposed mask mandates. “This, folks, is a manifestation of critical race theory,” she said before officers led her away for veering off-topic.

Felder wasn’t worried about the speeches, the audience outbursts, or even the members of the Proud Boys sitting inside wearing gaiters to cover their faces. “There was plenty of law enforcement within that auditorium,” she said. “You’d at least have time to duck and run.”

But the gathering outside, billed as a “Rally Against Filth,” felt different. “It’s as if hell was unleashed,” Felder said. “They were loud. Belligerent.”

Several carried enlargements of the most explicit Gender Queer illustrations. They

demanded the schools “quit trying to sexualize” children. They called for Felder’s resignation. And they whooped as a local Proud Boy emerged from the building and made a speech tying the board’s leader to the “Marxist” Black Lives Matter movement.

As Felder took in the scene from inside, someone in the crowd spotted her and pointed. “I’m not a person who frightens easily,” the superintendent said. “But I was afraid. And I was afraid for my life.”

The educational battles that have swept across America have taken deep root in Hillsborough, a county seat better known for its colonial-era architecture and literary vibe. Three separate factions—a Venn diagram of overlapping interests and conflicts—have been sparring over what the public schools should deliver and how a board of education should govern.

They have faced off at the podium, on social media, within the bureaucracy, at the polls, and at the barricades. They have met in public spectacles and behind closed doors. They have spoken in both blunt and coded words.

At stake is the success of 7,000 students attending seven elementary and six secondary schools.

Some of the battle in Orange County fol-

lows a national script, with an emboldened conservative movement organizing around themes like critical race theory. “The issues the public brings to school boards are increasingly refracted through the lens of national political discourse,” reported Education Week, a nonprofit news organization. The controversies “are now as much about political identity as they are about keeping students safe and engaged.”

It’s not just school board members feeling the heat nationally. Superintendents, too, have become increasingly targeted. In North Carolina, the Republican-sponsored Senate Bill 90 would give parents a tool to force out superintendents who repeatedly violate the “fundamental right to parent.”

The tension in Orange County doesn’t stop with the classic culture war. Board members and their supporters have also split into camps that call themselves “progressive” and “moderate.” Their central dispute is over how aggressively the board should prioritize the dismantling of systemic discrimination. But that doesn’t begin to describe the hostility between those two sides.

Orange County may seem like an unlikely setting for such a skirmish. But look at an electoral map of the school district and the polarization makes more sense.

12 August 9, 2023 INDYweek.com N E W S Orange County

Monique Felder PHOTO BY JULIA WALL

Hillsborough, with its riverwalk and rainbow flags, has grown as a progressive hub since the 2000s, when rising home prices in Chapel Hill established it as a relatively affordable alternative. But it is a blue hole at the center of an expansive red donut, including rural precincts that voted for President Trump by margins of three- and four-to-one. (Chapel Hill and Carrboro, also blue, form their own adjacent school district.) What appears, on the surface, like a liberal dominion is actually a place of stark contrasts.

Orange County Schools have undergone their own demographic change. A student body that was 65 percent white in 2012 is now less than 50 percent white. Students speak 40 languages at home. More than one in four is Hispanic. The number receiving free and reduced-price meals has climbed to almost half. LGBTQ+ kids are more visible.

To understand what this new diversity has meant politically, it’s worth detouring back a few years, to a moment when America’s capacity for coexistence hit rock bottom.

During the months surrounding President Trump’s 2016 election, Orange County Schools mirrored the divided nation. Anti-Semitic, anti-Muslim, and white supremacist graffiti appeared in school restrooms. A student told a Black teacher that “Black lives don’t matter.” Others chanted “build a wall” and taunted classmates with claims that Trump would

deport Black and Latino students.

Amid this, a parent named LaTarndra Strong was dropping off her daughter at Orange High School when she passed a white pickup truck waving a large Confederate flag.

Strong’s heart sped up as she flashed back to her Florida childhood. Hers was the first Black family in their suburban neighborhood, she said, and drivers with similar flags yelled the N-word through their windows as she walked to the park. “I would be afraid that truck was going to come around and hurt me,” she said.

Strong was a Republican in 2016 but not particularly political. She believed that if she alerted school authorities to this “blind spot,” they’d surely order Confederate flags—along with T-shirts, belts, and hats, which she said students wore—off campus.

She didn’t get the response she expected. “When you start banning symbols, you start attacking freedom of speech,” then Board of Education chair Stephen Halkiotis, a former Orange High School principal, said at the time. “You ban one flag, you’re going to have to ban every flag.”

Strong wrote to other parents. “I can’t do it alone,” she told them in an email. “I need your help.” They began turning out for school board meetings in December 2016, calling for an immediate ban on Confederate emblems.

Their numbers grew in the new year. Among them was Hillary MacKenzie, a white stay-at-home parent. She had been jolted into action after hearing the lan-

guage that fueled Trump’s election, a racism more overt than the hushed bigotry she had heard as a child in Orange County. “It made me realize, as a young mother, it was not the time to sit on the sidelines,” she said. MacKenzie met Strong and her daughter at a political gathering, listened to their story, and decided to join the effort. “Students should be able to go to school without hate symbols around them,” she said.

Halkiotis wanted to proceed slowly, with advice from legal experts about how to balance racial-climate and free-speech concerns. “Unilateral decisions can be made quickly,” he said. “A good, solid decision involving many people takes time.” Critics called him cowardly and tone-deaf for demanding patience in the face of white supremacy.

“It was my time on the cross,” he said. “I’m serious.”

In August 2017, the board came around. It voted to ban Confederate flags, swastikas, and Klan symbols. “I respect a flag that is held up as part of one’s heritage,” Halkiotis told a reporter, explaining his change of heart, “but not when it’s been co-opted by a militant racist group.”

Strong and her allies celebrated. They also noted that the board had waited until two days after a neo-Nazi struck and killed Heather Heyer during the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. “One of the things that became apparent,” MacKenzie said, “was that we needed a new school board, because it took them nine months to do this.”

MacKenzie ran in 2018 on a racial justice platform. She placed third in a field of eight, enough to secure a seat on the board.

The Confederate flag victory offered a tailwind to those eager to confront the obstacles faced by students of color. In 2019 the board acknowledged the “persistent racial intolerance, inequities, and academic disparities in our district.” That was the preamble to a new equity policy crafted by a task force that included Strong.

The policy called for recruiting a diverse workforce, improving training, and ferreting out barriers that keep certain students from learning. Halkiotis originally opposed it, saying the preamble’s mea culpa “puts us on shaky legal ground.” But the final vote was unanimous.

The board also hired Felder as superintendent in 2019. She had been working in Nashville and was impressed by how Orange’s equity policy acknowledged the district’s own shortcomings. “To me, here’s a board and a community saying, ‘We’re not trying to sweep anything under the rug,’” she said. “This was a district that had what I call teeth and muscle by way of a policy.”

Felder catapulted into the work, and her impact has been significant. The percentage of Black high school students in Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate classes increased from 18 percent to 30 percent over a year. The faculty looks more like the student body. Families who speak limited English at home or don’t use email have better access to school

INDYweek.com August 9, 2023 13

“This was a district that had what I call teeth and muscle by way of a policy.”

L to R: Gretchen Schmid’s laptop, LaTarndra Strong PHOTOS BY JULIA WALL

communications.

Wide demographic gaps persist, and on standardized test scores, only 48 percent of students achieved grade-level proficiency in 2021-22 (statewide, it’s 51 percent). But Orange ranked no. 1 among North Carolina’s 115 districts in terms of how many schools exceeded the state’s academic growth targets. And data released in June showed sizable gains in early-elementary literacy skills, with Black students outpacing the average.

MacKenzie and her allies remained a minority on the board until 2020, when a progressive electoral wave created a 5-2 majority with her as the new chair. The other two members were moderates.

From the moment she took the gavel, MacKenzie understood the clock was ticking. “I didn’t know how long I would be chair,” she said. “So I was going to make decisions to get as much done as we possibly could in a short period of time.”

Much of the board’s energy went into COVID-19 policy, which leaned toward caution in health matters. But board members also pushed on equity. They renamed two schools, one that had been named for a slaveholder and the other for a segregation-era school official. This cost the progressives some political capital; even supporters wondered about the timing.

“When Hillary first shared that she was going to move forward with renaming, I said, ‘Not now,’” said Strong. “Yes, we should do it. But not now, because the pandemic was still under way.”

The board also passed detailed guidelines to protect students and employees who are transgender or transitioning. This reflected a recognition that LGBTQ+ students in Orange County, as elsewhere, face considerable hostility. Teachers told The Assembly about students who tear down GayStraight Alliance posters or belittle their trans classmates with barbs like “I’m feeling like a sheep today.” One high school English teacher described a student who was trying to write about what made him proud of his trans identity and coming up dry. All he could focus on were the hardships.

The most contentious of the guidelines notes that some trans students feel endangered or unwelcome at home if they come out. “The school principal or their designee should speak with the student first,” the policy says, to decide “how to involve the student’s parents, if at all.”

Mental health professionals said the discretionary language would protect students’ safety. MacKenzie, who helped write the guidelines, said that was her intention. “I am in the business of keeping children alive,” she said.

Some voters, though, considered the language an encroachment on parents’ rights. One of them was a Colorado transplant who soon became the face of the conservative opposition.

It was affordable land that brought Gretchen Schmid to Orange County. Back in Colorado, her four children had attended private Waldorf schools, which emphasize

arts and the outdoors and limit technology. But after they relocated in 2020, one of her sons wanted a traditional high school experience with competitive sports. Schmid and her husband enrolled him in the ninth grade at Orange High School.

At the Waldorf schools, Schmid said, she met monthly with her children’s teachers. They explained what the students were reading and how those stories supported them at their developmental stage.

Schmid still wanted to know what her son would be studying. As she looked online for the curriculum, she stumbled on conservative websites from other states, where parents had scoured their children’s reading lists. “They identified the themes that kept coming up,” Schmid recalled. “And they were cannibalism, church is bad, family is bad, scary white people.”

Schmid’s alarm mounted the following year, when she learned her son’s English class was reading Like Water for Chocolate aloud. Laura Esquivel’s novel follows a Mexican woman whose cooking transmits powerful emotions, including sadness and lust. The tale has magical realism, political metaphor, evocative food writing, and extramarital sex.

“A totally inappropriate book,” Schmid said. “We teach our family about the importance of family and that we follow God’s plan for the family—and that is a very sacred emphasis on the power of procreation.” This means celibacy until marriage, and Schmid felt the book was at odds with that teaching. “We don’t need extra kindling

to put on what’s already really strong for a teenager,” she said.

Schmid considered this “grooming” and one example of public school overreach. She also disapproved of mandatory COVID19 testing and on-field masking for unvaccinated student-athletes. (Waldorf schools tend to draw vaccine-averse families like hers.) And she considered the transgender guidelines antifamily because they give schools leeway about notifying parents.

Schmid had already started organizing a chapter of Moms for Liberty, a self-described “parental rights” group that originated in Florida. The organization, known for its confrontational tactics, grew rapidly during the pandemic.

She set out to spread the word. Facebook reached a limited audience, so Schmid began approaching parents as they waited to pick up their children after school. One afternoon, she put on a purple T-shirt from a charity race, then walked the car line at an elementary school that serves many immigrant families. She handed out a QR code for a conservative website, promising parents they’d learn about library and classroom materials, test scores, and teacher attrition.

MacKenzie was there picking up her child. She spotted Schmid—“looking like a nice white lady, looking like a teacher,” she said. “And something about it just made me so angry.”

The board member jumped out of the car, leaving her husband to wait for the child. She followed close behind the Moms for

14 August 9, 2023 INDYweek.com

L to R: Hillary MacKenzie, Gretchen Schmid PHOTOS BY JULIA WALL

Liberty chair. “It’s propaganda,” she shouted to the drivers. “Call the school board if you have questions.”

MacKenzie threatened to call the police if Schmid held up the line. “How does it feel to spread lies, Gretchen?” she asked. “Why are you so against gay kids?”

“Why do you want to sexualize children?” Schmid shot back.

“Why are you a fascist, Gretchen?” the board member later asked, in a part of the exchange that Schmid recorded and conservative activists shared online.

In retrospect, MacKenzie said, she probably should have walked away. But she said she stands by her choice of words. “She is alt-right conservative and spreading misinformation,” MacKenzie said. “To me, that falls pretty closely in the line of fascism.”

Schmid’s Moms for Liberty chapter joined a matrix of groups organizing around district policies, including the Orange County Republican Party, which urged the board’s opponents to “sign up for public comments to push back on their equity agenda.” They already had. At a September 2021 meeting, parents called board members dictators and compared mask mandates to the Trail of Tears. They chastised the board for displaying a “terrorist”—meaning Black Lives Matter—flag. One paraphrased the book of Matthew, telling members to “tie millstones around your neck and throw yourself into the sea before you mess with these kids.”

Conservatives were also active online, describing the transgender guidelines as “parental subversion” and suggesting that next teachers will help students get secret piercings and change their religions. The Apex-based Education First Alliance, which sponsored the “Rally Against Filth,” claimed in a video that antifa was “informing the school board” and that MacKenzie supported “indoctrinating kids in gender fluidity.”

When Orange County’s schools announced an “affinity space” where Black employees could meet and support one another following some traumatic national headlines, the Virginia-based Parents Defending Education filed a civil rights complaint with the U.S. Department of Education. The 2021 complaint, which the department did not take up, alleged the district was promoting “explicit racial segregation.”

Both MacKenzie and vice chair Brenda Stephens said they received threats to their safety—and in MacKenzie’s case, death threats. This fits what the U.S. Department of Justice described in 2021 as “a disturbing spike in harassment, intimidation, and threats of violence” against school board members and school personnel nationally.

MacKenzie bought a home security system. Stephens, a Black retired librarian who served 20 years on the board, obtained weapons training and a concealed-carry permit.

“I remember someone saying, ‘I know where you live,’” said Stephens. “I said pub-

licly, ‘You step foot on my property, and you might meet your maker.’ Because I’m not going to be harassed or intimidated. This is not the ’40s, ’50s, and ’60s. They’ve been doing it to Black people for years.”

Three days before the “Rally Against Filth,” in October 2021, a parent named Jacquie Barker filed a complaint seeking the removal of Gender Queer and two other books from the Cedar Ridge High School library. Barker, who had a child at Cedar Ridge, said she had watched a video of a school board meeting from another district, where Gender Queer was discussed. It was the most challenged book in a year that such challenges increased fourfold, according to the American Library Association. The book contains several references to masturbation and five pages depicting frontal nudity or sex. On the most explicit page, the author and a partner, both young adults, awkwardly try to use a dildo for oral sex before abandoning the effort.

Barker said she wanted to see if the parents’ concerns were legitimate, so she borrowed the book from the public library. The LGBTQ+ characters didn’t bother her, she said, but the graphic content did. “These types of stories are over sexualizing our youth and indoctrinating them with grotesque sexual encounters,” she wrote in her complaint. She also found the author’s support for pediatric gender-affirming care, including medications to delay puberty, offensive.

Barker found sympathy within Cedar Ridge. In a conversation she recorded, then principal Carlos Ramirez told Barker that he had not read all of Gender Queer, but the pages he viewed online surprised him. “Our mouths kind of fell open,” he told her. “How is it that a national library association— where librarians across the country, really across the globe, buy books from their recommendation list—how did they not put a warning asterisk or something?”

Ramirez said the comment reflected his opinion rather than school policy. Two review committees, one of which included Ramirez, later read the full book and recommended keeping it. So did Felder, the superintendent.

The school board made the final call during a Zoom meeting in January 2022. Members described Gender Queer as more complex than opponents depicted: the sexual sequences were a small slice of the author’s journey from confusion to self-respect. “I was also deeply touched by the loving and supportive family and community that helped Maia Kobabe,” said Carrie Doyle, MacKenzie’s successor as chair and another progressive. “My hope is for [our] community to be equally supportive of our LGBTQ+ students, staff, and families.”

MacKenzie noted the high suicide rate among transgender and nonbinary youth. Her motion to retain the book, indefinitely and district-wide, passed 7-0.

The board then voted to keep the two other books that were contested for their

INDYweek.com August 9, 2023 15

L to R: Cedar Ridge hallway, Cedar Ridge library shelf PHOTOS BY JULIA WALL

descriptions of sex and abuse: Jonathan Evison’s Lawn Boy, about a young landscaper trying to break out of poverty, and Ashley Hope Pérez’s Out of Darkness, about an interracial romance during the lead-up to a fatal school explosion in 1930s Texas.

Each vote was unanimous: a display of common ground by a politically divided board. “My mother was an Auschwitz survivor,” member Bonnie Hauser, a moderate, told The Assembly. “So book banning has real meaning.”

By then, the 2022 elections were approaching, and the next skirmish was brewing—over issues more mundane but no less contentious.

Orange County still had to deal with runof-the-mill school concerns, including a nationwide teacher shortage. The district pays smaller salary supplements than nearby Chapel Hill–Carrboro, Durham, and Wake, which have more students. It relies on the county government for the local share of its budget, as it can’t independently levy taxes to pay teachers more.

This has consequences in the classroom. Seventh graders at Gravelly Hill Middle School in Efland went a year without their own math teacher. Instead, they logged into North Carolina Virtual Public School and communicated with remote teachers by email, text, and instant messaging while other educators provided in-classroom support. At least twice, a substitute-teacher shortage meant that multiple

classes had to gather in the auditorium. The state’s Department of Public Instruction gave Gravelly Hill a failing grade last year based on student test scores and academic growth.

Parents across the district felt frustrated by issues at their own kids’ schools. Some blamed the Board of Education for misplaced priorities. “We have all of these issues in the school district,” said Polly Dornette, whose son attends Gravelly Hill.