Raleigh | Durham | Chapel Hill

June 26, 2024

Revisiting Southern Noir, p. 16

Reading silently, together, p. 32

Reviews of books, neighbors, monsters, p. 14 ...and more!

Raleigh | Durham | Chapel Hill

June 26, 2024

Revisiting Southern Noir, p. 16

Reading silently, together, p. 32

Reviews of books, neighbors, monsters, p. 14 ...and more!

5 Durham's teachers' union scored a big funding win in the county budget, but another fight with the school district is just heating up. BY JUSTIN LAIDLAW

8 Two LGBT-owned businesses are fostering community in a growing downtown Raleigh. BY NATION HAHN AND DAVID BLAIR

10 A Durham planning commissioner resigned from his position in protest. BY LENA GELLER

Book Reviews: Neighbors and Other Stories, Monsters We Have Made, and Shae BY GABRIEL BUMP, VERONICA KAVASS, AND KATIE MGONGLWA

16 Carrboro author Joanna Pearson's new novel follows the long aftershocks of a college campus murder. BY SARAH EDWARDS

32 Silent Book Clubs serve as a low-key way to come together and experience the joy of literature. BY AVERY SLOAN

34 Talking with Raleigh author Stephanie Clare Smith about her heart-wrenching new memoir, Everywhere the Undrowned BY FRED WASSER

36 An interview with Scott Ellsworth about The Secret Game, 80 years after the groundbreaking Duke v. NCCU college basketball game. BY JUSTIN LAIDLAW

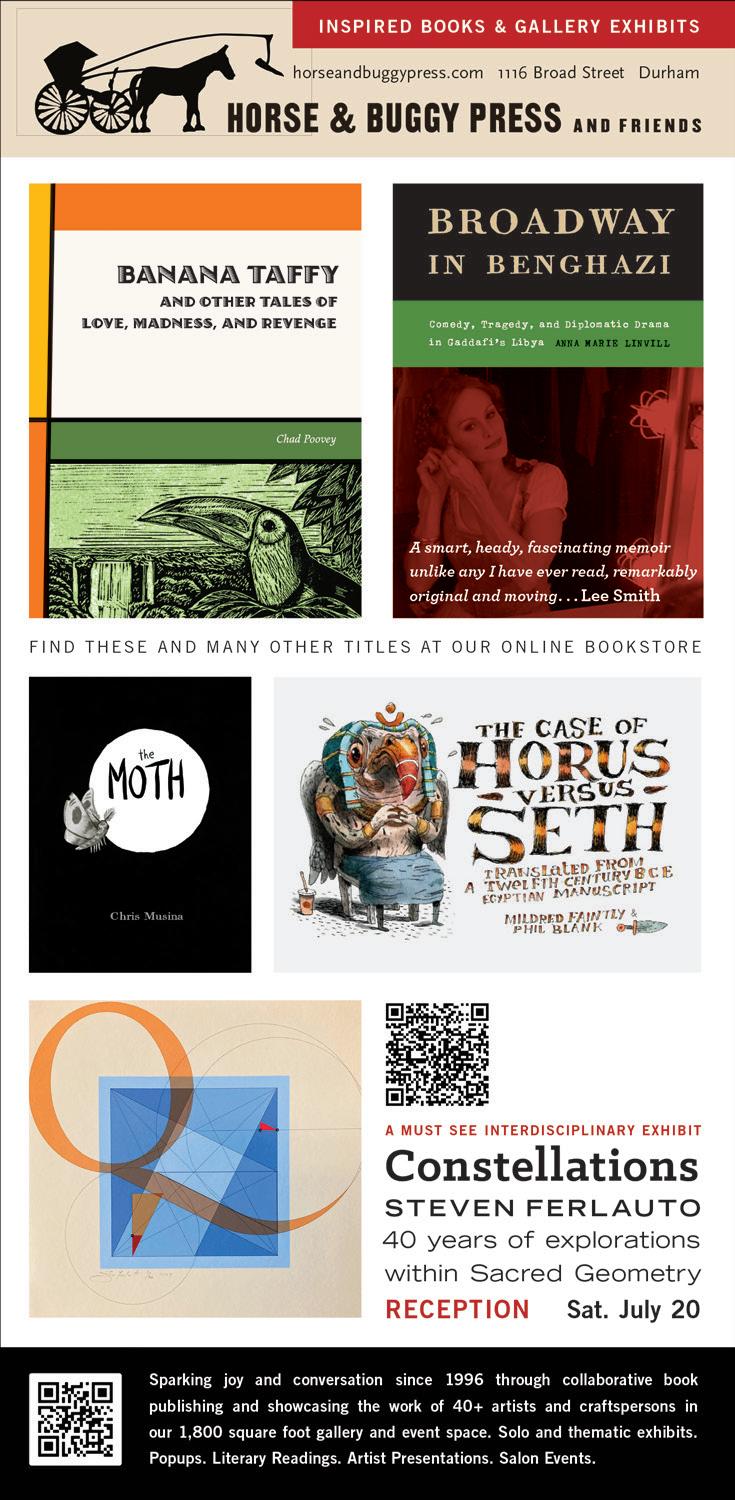

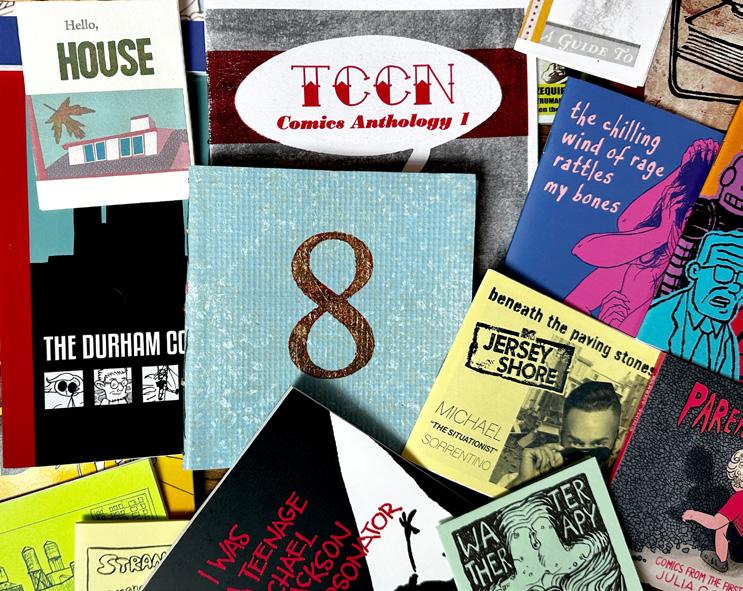

38 Comic Connections: Patrick Holt breaks down his online local store, Triangular Comics & Zines. BY JUSTIN LAIDLAW

BEACH PHOTOS VIA UNSPLASH AND PEXELS

W E M A D E T H I S

Publisher John Hurld

Editorial

Editor-in-Chief

Jane Porter

Culture Editor

Sarah Edwards

Staff Writer Lena Geller

Reporters

Justin Laidlaw

Chase Pellegrini de Paur

Contributors

Mariana Fabian, Desmera Gatewood, Spencer Griffith, Carr Harkrader, Matt Hartman, Tasso Hartzog, Brian Howe, Kyesha Jennings, Hannah Kaufman, Jordan Lawrence, Elim Lee, Glenn McDonald, Nick McGregor, Gabi Mendick, Cy Neff, Shelbi Polk, Byron Woods, Barry Yeoman, Sam Overton

Copy Editor

Iza Wojciechowska Interns

Matthew Junkroski

Mila Mascenik Avery Sloan

Creative

Creative Director Nicole Pajor Moore

Graphic Designer Ann Salman

Staff Photographer

Angelica Edwards

Advertising

Publisher John Hurld

Director of Revenue

Mathias Marchington

Director of Operations

Chelsey Koch

Circulation

Berry Media Group

Membership/subscriptions

John Hurld

INDY | indyweek.com

P.O. Box 1772 • Durham, N.C. 27702 919-666-7229 support@indyweek.com to email staff directly: first initial[no space]last name@indyweek.com

Advertising sales sales@indyweek.com 919-666-7229

Contents ©2024 ZM INDY, LLC All rights reserved. Material may not be reproduced without permission.

For our paper two weeks ago, contributing writer Andrea Richards wrote a fascinating, in-depth piece about Locals Seafood, one of the few seafood companies in North Carolina that keeps its products truly local from state fish purveyors through a sprawling statewide seafood distribution trajectory. We got some messages from our readers about the story.

From reader DEDE REID, via email:

Hallelujah Locals Seafood is back!

I’m from Washington DC where the wharf was our main source to go for any kind of seafood you’d ever imagined! The wharf in the 50’s and 60’s was the Afro American place to purchase, have your fish cleaned at the fish house which the workers worked off of the tips they made and then when the Asians settled in the DC area they where able to get the barrels of fish heads, etc. free! Everything thing has changed. No wharf, no more fresh, different flavors of seafood, no more community or melting pot of different nationalities to meetup and share stories or recipes in one place.

Now living here in North Carolina we can’t find a decent fish house to purchase seasonal seafoods, melting pot of different nationalities to meetup and share their experiences or recipes Again HALLELUJAH LOCALS SEAFOOD!!!

I truly hope you read this or pass this on so we can get back some of our lost cultures.

Because we need something to celebrate and give us hope in this upside down world

And from reader TAMMY PEARSALL-JONES:

This was a great story. I grew up with Ricky and visit Salt Box often. I even have a T-shirt. I’m glad to see that I can get good seafood at Locals. I’ll be visiting the site at the Farmer’s Market this weekend! I’ve caught a huge sheepshead before but we gave it away at the pier because I’d never eaten it before. Obviously we missed some good eating. Lol!

For the web, and to happily coincide with Pride month, Chase Pellegrini de Paur wrote about Katelyn MacDonald, who went viral for her rendition of Chappell Roan’s “Hot to Go” played on the bells at Duke Memorial Church.

Reader BILL LOVELL sent us this note via email:

My wife and I were married at Duke Memorial UMC in 1961. We are so proud to see this marvelous caring congregation lead the way in affirming God’s love for all of us.

For more Pride month content, see our story on p. 8 about the LGBTQowned businesses in downtown Raleigh that are fostering community in a growing city all year round.

Donald Trump shuttered Durham’s Black-owned businesses. Under President Biden, we’re thriving.

BY LEONARDO WILLIAMS backtalk@indyweek.com

Earlier this month marked the launch of “Black Voters for Biden-Harris,” a national organizing program highlighting how President Biden has continued to deliver for Black families. I’m proud to be a member of this coalition, because I saw firsthand the damage Trump did to our communities and I know we can’t go back. I’m a small business owner, and any business owner will tell you that Trump was a disaster—especially if you’re not a big corporation, and especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic disproportionately impacted Durham’s Black community, permanently closing an estimated 25 percent of the city’s Blackowned businesses. Trump’s failed leadership during the pandemic and his botched Paycheck Protection Program (PPP)— which was marred with racial inequities— are largely to blame.

“Locally, our economy is thriving. The unemployment rate in the Durham-Chapel Hill metro area is now under 3 percent, labor force participation is increasing, and the economy is growing. All of this was accomplished under President Biden.”

A July 2021 report from Duke University painted a stark picture of this racial divide facing our community’s businesses. Using hand-collected data on the race of small business owners in Durham, they found that choosing not to disclose one’s race led to better outcomes for borrowers.

On average, Durham small businesses owned by Black entrepreneurs who chose not to disclose their race received 42 percent more PPP loan funding than those who did disclose their race. By contrast, there was not a statistically significant difference for white borrowers based on the disclosure of their race.

As a small business owner myself, this study confirmed what I was seeing on the ground: the Trump administration was leaving Black small business owners out in the cold to fend for ourselves.

This looming crisis compelled me to convene peers and establish the Durham Small Business Coalition and organize $3 million to support the local entrepre-

neurs who were unable to access pandemic relief.

In 2020, Joe Biden campaigned on promises to Black voters, and as president, he has the receipts to show he’s kept them.

Since taking office, President Biden has worked to fix these inequities, improving the Small Business Administration’s loan programs to expand the availability of capital to underserved communities. The result? President Biden has overseen the fastest increase in Black-owned business creation in more than 30 years—and more than doubled the share of Black business owners from 2019 to 2022.

But that’s not all. President Biden’s Investing in America agenda has prioritized ensuring that funds from his signature legislative accomplishments—the American Rescue Plan, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, the CHIPS and Science Act, and the Inflation Reduction Act—are all flowing to Black communities, breaking a decades-

long cycle of disinvestment.

The results of President Biden’s economic vision are now clear as day: Black unemployment is at a record low and Black wealth is now up by 60 percent compared to pre-pandemic levels.

And locally, our economy is thriving. The unemployment rate in the Durham–Chapel Hill metro area is now under 3 percent, labor force participation is increasing, and the economy is growing. All of this was accomplished under President Biden, whose administration has made historic progress to bring our country back from the pandemic and build an economy from the bottom up and the middle out.

I’m a proud member of the “Black Voters for Biden-Harris” coalition, because I’ve seen what’s at stake for working families in our community. During the Trump administration, not all businesses or business owners were treated equally. As president, Trump was so focused on gaining power for himself and giving handouts to the wealthy, he failed to provide relief when folks in Durham needed it most— needlessly shutting down businesses and causing unemployment to skyrocket.

Meanwhile, President Biden didn’t just lead us out of this crisis—he created an economic miracle on the way, and made sure that Black folks shared in the benefits. We’ve come a long way since the pandemic, and we can’t afford to give Trump the chance to reverse our hard-fought progress. W

Durham mayor Leonardo Williams owns two restaurants in the Bull City with his wife, Zweli.

The Durham Association of Educators scored a big win for workers’ pay in the new county budget, but the fight for a “meet-and-confer” policy is just getting started.

BY JUSTIN LAIDLAW jlaidlaw@indyweek.com

The mass of red-shirt wearers inside the Durham County meeting hall was abuzz with excitement.

Symone Kiddoo, president of the Durham Association of Educators (DAE) teachers union, ushered members into the long wooden pews that faced the front of the hall where county staff and the board of county commissioners waited to deliberate over the 2024–25 fiscal year budget one final time.

The commissioners were expected to vote that evening, June 10, in favor of the school board’s historic $27 million ask for local funding after the county finance director, Keith Lane, had laid out the math for how to fully fund the board’s request during a budget hearing.

But Kiddoo had been in this fight long enough to know not to let her guard down. She held a modest smile as the meeting proceeded. Even if Kiddoo and her allies scored a big win after a long, drawn-out battle, another struggle with the district was already under way. The DAE was going to the mat with the school board over a “meet-and-confer” policy, which would create a framework for the union to engage more meaningfully with Durham Public Schools (DPS) administrators and give voice to worker concerns.

“[It’s] recognizing the union does not disrespect the workers that have not joined the union yet,” Kiddoo says of the DAE’s goal. “Rather, it affirms workers’ rights and shows all workers that the district respects our right to organize.”

Six months earlier, a payroll crisis set off a firestorm throughout DPS. DAE capitalized on the moment, organizing educators from across the district to push the school board and county commissioners for stronger commu-

nication and better resources. Union membership grew exponentially.

Now, DAE wants a seat at the table to ensure its members are adequately represented in future negotiations and to prevent further deterioration of trust between educators, the school board, and county leadership.

But as negotiations have stalled, the union continues to apply pressure to get a policy on the books.

In January, turmoil ripped through the local education community after DPS administrators determined the district could not afford the pay raises it had allocated last fall.

Realizing its mistake, the district tried to rescind the raises. More than 1,300 classified workers—nurses, cafeteria workers, instructional assistants, maintenance staff, and others—were affected. Frustration over the mishandling of the issue, which the school board and district administrators were addressing mostly in closed sessions, led to weeks of sick-outs, where teachers and other employees called out of work in protest, spending days marching through Durham streets and holding rallies with hundreds of community members.

Ultimately, the district’s chief financial officer Paul LeSieur and superintendent Pascal Mubenga resigned over the scandal.

“There was obviously a lot of frustration, anger, and a sense that things are getting worse or things are not going to change,” says Carlos Perez, a Jordan High School history teacher and member of the DAE executive board.

As funding for North Carolina public schools has dwindled over the last decade, teachers are asked to do more with less, leading to burnout. DPS’s teacher attrition rate is up from 8.3 percent in 2021 to 12.9 percent in 2023, according to the NC Department of Public Instruction.

Supplemental positions such as instructional assistants and exceptional children (EC) educators have also been cut, placing a heavier burden on remaining school staff. Educators and staff felt that their voices were unheard, their demands unmet. DAE took the opportunity to bring those workers together under the banner of the union.

“The pay debacle was a spark or a catalyst, but by the time that popped off, we had already generated a petition with clear demands that came out of talking to workers across the district about what their real needs are,” Perez says. “We had already been scaling up the union.”

DAE members deployed various tactics—taking days off work to talk to colleagues at other schools, waking up early to visit school bus lots, tabling before and after school to talk to people as they came and went—all in service of building up the union’s membership.

“That’s what made us prepared to seize the moment in the way that we did,” Perez says. “But also part of what allowed us to position ourselves is a widespread recognition that public education is under attack and in a state of crisis. Anyone who’s worked a day in public schools, either here in Durham or elsewhere, knows that.”

DAE now had ample leverage to organize members in service of its cause.

“There was a sense of hope and solidarity and inspira-

tion that people were on the move and on the move for each other,” Perez says. “And that was palpable, definitely at my building.”

Elevating workers’ voices is a major selling point for DAE. Employees, especially classified staff, have found a vehicle for their frustrations, Perez says.

Quentin Headen, an instructional assistant at Riverside High School, quickly became a fixture at DAE rallies after he was recruited last year and spoke on behalf of the many classified staff members, who he says are overworked, underpaid, and underappreciated.

“If you mess with the classified staff, you mess with the 90th percentile of your school,” Headen said as he stood on a picnic table and addressed a cheering crowd through a megaphone at a rally on January 31. “We wanted a seat at the table. That message has now changed. We demand a seat at the table.”

Headen and others have become leaders at their schools and in their community after joining DAE’s ranks. Should another issue like the payroll crisis arise in the future, Perez says, more folks will have the muscle memory to act with confidence.

“Look at the number of people who have stepped up across the district in every school, in every job category, whether it’s cafeteria workers, janitors, EC, instructional assistants, teachers,” says Perez, who has been a DAE member since he moved to Durham in 2017 and started working in the district. “I’ve never seen this scale of activity or this level of participation and involvement in the union. It’s a beautiful thing to see.”

Membership in the NC Association of Educators (NCAE), the statewide parent organization of DAE, stalled in the mid-2010s after Republicans gained power in the state legislature and changed how the organization was allowed to operate. North Carolina is a right-to-work state, making union membership across industries some of the lowest in the country.

Toward the end of the decade, a new class of NCAE leaders rejuvenated the organization’s membership and fundraising efforts and bolstered the foundations of its local chapters. Momentum was already on DAE’s side when the union voted to elect its new president, Kiddoo, in the summer of 2023, leading the charge toward the union’s efforts to secure adequate pay and other worker rights.

Kiddoo, a Durham native and graduate of Jordan High School, knows the district intimately. She began working as a DPS school social worker in 2015, helping families access the resources they needed to succeed in the school system. Not long after Kiddoo started, Donald Trump was elected president and state Republicans continued to dry up resources for public schools. This put a particular strain on Latin American families in the district, Kiddoo says.

“I was now facing this very real issue of kids’ fears of their parents being deported,” Kiddoo says. “I can teach them about coping skills for anxiety. But that’s a legitimate fear. I can’t cognitive-behavioral-therapy their way out of that fear when the president-elect gets on the news and says he wants to deport their parents.”

In 2016, Wildin Acosta, a Riverside High School student was facing deportation two years after fleeing to the United States to avoid gang violence in Honduras. Members of the community, including folks from DAE, worked diligently to keep Acosta in Durham. Kiddoo says this showed her a

blueprint for how to make a deeper impact.

“To me, the social worker who was trying, and what felt like failing, to address this major issue for students, I was now presented with ‘Oh, these folks are not just applying a Band-Aid. This is not just about let’s talk about your anxiety of your parents getting deported. They [DAE] are stopping deportations,’” she says. “And I was like, ‘Well, that’s the thing that I want to do.’”

Kiddoo served as a DAE district organizer, supporting building leaders in different schools, before being elected president. Colleagues attribute her success to her background as a social worker, her skills as a listener, and her willingness to make space for others to be recognized while giving them tools to be successful.

“I’ve known Symone for years, and worked very closely with her, particularly during this campaign,” Perez says. “She’s a humble person who’s not in it to make a name for herself.”

In the year since she took over, DAE membership has quadrupled to over 2,600 employees across the district, according to Kiddoo and others. The union now represents a majority of DPS workers across the district and is taking its power in numbers back to the school board to fight for a meet-and-confer policy.

After the fallout from the pay issue, the school board organized an ad hoc committee to discuss ways to prevent future miscommunication and other challenges between the school board and workers. The process, intended to be a negotiation between DAE, the school board, and DPS administrators, broadened when district administrators included non-union workers, frustrating DAE leadership. Four DAE members representing the union in the ad hoc committee walked out in protest at the start of a meeting on May 20.

Although there is overlap between the goals of the union and those of individual workers, Kiddoo says the ad hoc committee has stalled progress on enacting a meaningful policy.

“The board has created a narrative that the idea of meet-and-confer with union recognition is somehow excluding other workers,” Kiddoo says. “We understand our job, as an employee representative organization, to have the broadest representation of voices possible. We recognize that there is a clear mistrust and gap of communication between individual workers and management. That is still true. That was

apparent through the classified pay issue.

“It has been conflated into the same issue, and it’s not,” Kiddoo continues. “A possible path is that they could bifurcate the process. We should deepen the policy that exists for individual workers to be able to have better communication about their working conditions between management. But that is different from an organization of workers being able to sit down with management and negotiate on working and learning conditions.”

The school board and DAE have been in “deep partnership” for years, says Bettina Umstead, chair of the Durham school board. She says she hopes that, despite the recent dissolution of trust, the two organizations can continue to collaborate on what’s best for public schools going forward.

“We know they have a growing membership that is touching these buildings across Durham Public Schools and connecting folks, with the ability to connect with each other and help us grow and be better as a district,” says Umstead. “That’s a vital partnership and relationship that we have, and we want to make sure we keep and strengthen it. And then, how do we also make sure that we are looking at something everyone feels they have some connection to?”

But the trust that once existed between the board and DAE is seriously frayed. Natalie Beyer, a longtime school board member, is clear-eyed about the damage the payroll

crisis did to the relationship between DPS leadership and the district’s rank and file.

“Mistakes with people’s checks are unforgivable,” Beyer says. “It was worse to govern through than the pandemic for me. Because there was no easy way to fix it. And there was no clarity about what money we had to fix it with. And we had no CFO. It was a nightmare that kept going. And we felt responsible for all of them and the mistakes that were made by our staff.”

Meeting the DAE’s request for a meet-and-confer policy is one way DPS leaders could begin to repair relationships in the aftermath of that nightmare, but, after five meetings so far, the union and school board still have yet to agree on the terms of such a policy.

“We often hear our leaders say that Durham is a union town. This moment tests that proposition,” Kiddoo said at a rally in front of the Durham County administrative building on May 28. “We call upon the school district and the Board of Education to stand on the right side of history and recognize our union as a legitimate employee representative organization with a meet-and-confer policy.”

DAE could have more allies in leadership come this fall. Wendell Tabb, a longtime drama teacher at DPS’s Hillside High School who retired in 2022, and Joy Harrell, an educator and art instructor whose husband, Malcolm Goff, previously served in DAE leadership, will join the school board. Former DAE president Michelle Burton and former school board chair Mike Lee will join the board of county commissioners.

And DPS is searching for a new superintendent. Whoever fills the position will face the tough task of building back burned bridges and realigning DPS, DAE, the school board, and the county commissioners as a united front facing a common adversary, the Republican-led General Assembly, which last year passed legislation to route more

than $4 billion away from public schools and into private schools via vouchers over the next decade.

“There’s a public school and public institution issue of being underfunded, and then having people in leadership positions who don’t have the resources they need to be good leaders,” Kiddoo says. She acknowledges that administrators such as Mubenga and LeSieur made mistakes— but that it’s “hard to be the superintendent and the CFO of a public school district in North Carolina with massive underfunding and deeply impacted schools.

“The underfunding problem from the state for public education has been a very deliberate attack for a long time,” Kiddoo says.

On June 10, the budget vote was the last item on the county commissioners’ agenda.

Lane, the finance director, stepped to the podium to explain that, between the county’s contributions and funds remaining from the American Rescue Plan Act, the school board was getting its $27 million.

Durham county commissioner Heidi Carter, who served on the school board for 12 years before she was elected to the county commission in 2016, and who is serving her final term, said the budget reached 98 percent of the school board’s request.

The vote was not yet official, but the writing was on the wall. Months of advocacy from teachers, staff, parents, and others had succeeded.

The audience in the county meeting chambers erupted in applause.

But not everyone in the chamber was celebrating. When it came time to vote, veteran commissioner Brenda Howerton was the lone dissenter. She expressed concerns about the long-term sustainability of an increasing amount of the county’s budget going to education, and keeping DPS

financially accountable after recent mismanagement.

Howerton said her duty as a commissioner meant she had to consider the impact of a 4.65¢ tax increase on all county citizens, not just those in the education system.

“As a commissioner, I’ve learned to force tough conversations regarding systems accountability,” said Howerton, who is in her last term after losing her reelection in March.

“This proposed increase on top of the increase during the previous years deserves more reasonable discussion related to accountability,” Howerton said. “The honoring and support of teachers, administrators, and classified workers is worthy of that kind of consideration. It is also worth noting the impact of tax increases on the most vulnerable citizens. It is my contention that property tax increases by both the city and the county during the same period—it’s too much to ask our citizens.”

Howerton’s comments received applause, even from DAE members. She was right. The challenges facing the county and the public school system were far from over. Without a clear source to increase revenues, the current method of supplementing DPS’s budget with county funding at this scale is not a viable plan year after year.

But that was a problem for another day. That night, once the vote became official, the folks who had worked tirelessly to advocate for stability within Durham’s public schools were overjoyed.

Kiddoo couldn’t contain her jubilation, even as she prepared herself for the next fight.

“The union work we’ve done together this year has already transformed Durham for the better,” Kiddoo said at a press conference the next day following the successful 4–1 budget vote. “This is only the beginning. This victory will serve as an example for years to come, not just in Durham but all over North Carolina and the South. We did this.” W

During Pride Month and the rest of the year, LGBT-owned Libations 317 and the Green Monkey show that downtown Raleigh needs its small businesses to foster community and inclusivity as the city grows.

BY NATION HAHN AND DAVID BLAIR backtalk@indyweek.com

Two small business owners who grew up in rural North Carolina have taken similar journeys that led them to open businesses in downtown Raleigh in recent years. Both emphasize creating inclusive spaces that provide a sense of community for all, including the LGBTQ community.

“I wanted a space for people like me. People who might not always feel like they fit in everywhere,” says chef Gregory Hamm, owner of Libations 317.

“I wanted a place where you could be yourself and shop,” says Rusty Sutton, co-owner of the Green Monkey.

Hamm opened Libations 317 at 317 West Morgan Street three years ago this month. Sutton and his husband, Drew Temple, opened the Green Monkey at 215 South Wilmington Street one year ago. Both businesses have worked hard to create a sense of community mere blocks from one another.

Both spaces aim to be places where everyone feels welcome.

“I want Libations 317 to be a place where everyone feels at home,” Hamm says. “I want it to be welcoming to people like me who might not fit in everywhere.”

Inclusive spaces aren’t just for Pride Month or the LGBTQ community, both owners say—they’re for everyone, all the time.

The location of Libations is a nod to Hamm’s journey. The original tenant for the West Morgan Street space was the Borough, a neighborhood bar and restaurant. Chef Hamm is “happy to serve every-

one,” but he warmly welcomes the LGBTQ community as Borough owner Liz Masnik did throughout her tenure running the beloved local business that shuttered in 2016. To pay homage to the Borough, Hamm continues the tradition of one of its most popular drinks, the Q, which is “Vodka + Vodka + Vodka + Vodka + Vodka + splash of Magic Juice’’ to start your night off with a bang. Hamm has recreated a Borough atmosphere, with local dive bar vibes, while also embracing newcomers.

Hamm’s culinary journey began in high school with guidance from his teacher Patricia Werth. With her support, he enrolled in Johnson and Wales University to study the culinary arts. After graduating, he moved to Raleigh to work with Werth to develop a culinary curriculum, then relocated to Lee County to begin teaching. Hamm credits Werth’s support, love, and inspiration for his career, as she helped him unlock his love for food and his talent.

Hamm chose Sanford for his first restaurant, Cafe 121, which opened 16 years ago. Since then, he has opened a series of businesses, including Libations 139 in Sanford and now Libations 317 in Raleigh. Hamm’s consistent focus throughout the growth of his restaurants has remained the same: “I want to know the source of the food, for our guests to know what is in the dish, and for every guest to know who cooked it.”

One of Hamm’s seasonal favorites is a collard-and-pork egg roll, a very popular

offering around the New Year. His jalapeño-pimento cheese will keep you coming back to his takeaway pantry. He has a trained baker, who also worked with him in the community college system as a culinary instructor, crafting his cakes, baked goods, and biscuits. If you want a biscuit and gravy that tastes like something your country-Southern grandmother would make, Libations will satisfy your cravings for something a little more traditional for Sunday brunch.

Hamm has always enjoyed cooking international foods, so on Saturday and Sunday, his menu is Asian inspired with dishes like beef and broccoli and crispy sesame chicken. His primary cook in Raleigh has Mexican roots, so many of “Robert’s Favorites” provide some Mexican flavors on other nights. Hamm has created a menu that varies throughout the week to serve what he’s dubbed “a community of regulars,” who can eat there multiple times a week and try something new each visit. And if you don’t have time to stick around and eat in, his takeaway pantry fridge is great for tailgates, family gatherings, and nights in.

The summer menu for Libations will include an array of dishes that Hamm believes will resonate with guests in the hotter months, including several new salads (like the Crispy Asian), wraps (such as

the Carolina Chicken with hoop cheese), and customer favorites like the jala-pimento cheese.

Hamm notes that the summer “glam and grub” dinner series of drag shows is a new endeavor, marking the first time Libations is hosting evening dinner shows. Although Libations staff are experienced with drag shows, the format of a monthly dinner show throughout the summer is new. They plan to continue these shows in the future based on audience demand. A six p.m. show allows you to come in, have a bite to eat, a few cocktails, and plenty of laughs, and then continue your night elsewhere.

“I want Libations to be a place where people can start their night,” Hamm says.

A few blocks away on Wilmington Street, you will find a funky gift shop meets bar meets event space. Sutton shared the early vision behind the Green Monkey, which began at an area flea market, during a recent visit.

“We were the only flea market vendor selling pride merchandise in June of 2007,” Sutton recalls with a laugh.

Sutton’s journey to the flea market began in Wilson, just east of Raleigh. The career path for many of his friends and family led to farms, manufacturing, or truck driving. However, his sister was an accountant, and

he thought business sounded like a great way to make a living. He was also motivated by those who doubted him.

“People said I couldn’t do certain things or that I would never amount to anything. And I believed in myself,” he says.

Determined not to stay at the flea market forever, Sutton enrolled in a business plan course at Wake Tech to develop a strategy for a full-fledged store. He sought advice from local mentors, including Rose Schwetz, who owned the iconic dive bar and music venue Sadlack’s. Schwetz promised to help Sutton find a venue once he had a business plan. She led him to the onetime Royal Mart, a dingy, dark place on Hillsborough Street, which Sutton initially rejected. But Schwetz persisted, and in 2013, she convinced him to transform the Royal Mart into his vision.

Several friends helped ensure the Green Monkey survived its challenging first year. A beer rep offered a deal on a keg, a friend built a custom bar that debuted in 2015, and another made a business investment. These efforts, combined with Sutton and Temple’s hospitality, turned first-time visitors into repeat customers, giving the Green Monkey real momentum.

The momentum continued until the pandemic disrupted retail and social spaces, but loyal customers helped keep the Green Monkey afloat. A change in landlords led them to need a new home for their business, and this eventually led them to 215 South Wilmington Street. The space had sat vacant for decades but was once home to the Raleigh Sandwich Shop. Sutton and

Temple both fell in love with the space and its potential for downtown Raleigh.

Today at the Green Monkey, customers can expect a warm welcome (Sutton promises you’ll hear “Welcome to the Green Monkey, y’all” when you walk in), a gift for first-time visitors that changes annually, unique merchandise (much of it designed by Sutton), a full bar, grab-and-go food options, and events like trivia nights, drag performances, and more.

Both Hamm and Sutton are dedicated to ensuring their welcoming spaces remain part of Raleigh’s evolving downtown. And spaces like Libations and the Green Monkey show that, as the city grows, it still needs spaces to foster community and inclusivity in downtown Raleigh. These businesses are more than just places to spend money and drink, according to their owners. They believe these are spaces where you can meet new friends, be among like-minded people, and feel a genuine sense of welcome not only during Pride Month but year-round.

Sutton says he is optimistic about both the future of downtown Raleigh and his store.

“I know what I am supposed to be doing,” he says. “We’ll be here as long as people support us.”

Hamm feels similarly.

“The happiest moments for me are when I bring guests to the table and share culinary stories and food culture with them,” he says. “When scratch-made foods evoke memories of life, travel, childhood, and heritage, I know I’ve done my part.” W

A Durham planning commissioner resigned in protest with a year left in his term.

BY LENA GELLER lgeller@indyweek.com

ADurham planning commissioner has resigned in protest of the way in which some Durham City Council members have, in his words, “dismissed, at times ignored,” and “even denigrated” the work and expertise of the planning commission.

Anthony Sease, a civil engineer and adjunct assistant professor at Duke’s Nicholas School of the Environment, was appointed to the planning commission in 2021. He submitted his resignation letter to the city council via email earlier this month, a day after announcing his imminent exit at a planning commission meeting. (“This is going to be my last meeting,” Sease said at the planning commission meeting on June 11.)

Sease’s second term on the commission was set to expire in 2025. In response to a request for comment from the INDY, Sease shared his resignation letter but declined to

comment further on the matter.

The planning commission serves as an advisory board to the city council on land use and development cases. Durham City Council members and county commissioners appoint planning commission members to weigh in on rezoning and annexation proposals before those cases come before council. The planning commission can approve or oppose proposals and leave comments on them, but it doesn’t have real voting power.

In remarks Sease made during the commission meeting Tuesday night, which closely resemble the contents of his resignation letter, Sease stressed that his discontent is not related to the commission’s lack of a final say in land use cases: “It’s perfectly fine if the council opts not to adhere to our recommendations,” Sease said. “There will be a lot of cases where they shouldn’t; where things change before

they get to the final vote.”

Sease’s issue, he said, is that “there’s been a bit of a tendency for the work of this commission to be diminished, and not only that, but just flat-out called into question and attacked” by members of the city council.

For example, a council member recently called the expertise of the planning commission into question, saying it is the role of elected officials to “be the experts” and that planning commissioners “are not experts,” Sease said.

Sease is likely referring to a comment mayor pro tem Mark-Anthony Middleton made at a city council meeting on April 15. At the meeting, council member Chelsea Cook referred to planning commissioners as “appointed experts,” and Middleton responded that while he has “high regards for the planning commission’s” work, “all of our boards and commissions are volunteers, and when we put them on, they’re not all necessarily experts.

“Our boards and commissions can allow you to become an expert. You can get on the planning commission, and if you apply yourself and read all the stuff, you can become an expert. Oftentimes these planning commissions and boards allow people who just want to volunteer to get expertise and experience in areas that they have none in. We don’t ask for experts in planning to go on the planning commission. Some of them are. Some of them are not.”

“They are certainly not 100 percent all experts,” Middleton added.

Sease refuted these assertions in his remarks at the meeting and in his resignation letter.

“Expertise is not required to serve, yet everyone on the Planning Commission is an expert at something,” Sease wrote in his letter, noting that the commission is currently made up of people with expertise in city and regional planning, residential real estate sales, commercial real estate brokerage and development, corporate finance, civil engineering, engineering project management, site planning, and law.

Sitting members include a PhD “whose dissertation research was planning and development practices in Durham,” Sease wrote, as well as an executive leader who manages “hundreds of millions of dollars of real estate for one of our state’s public institutions” and a site planner who has helped “implement thousands of housing units across a dozen states, and hundreds of affordable units in North Carolina.”

In an emailed statement to the INDY, Middleton reiterated that planning commissioners are volunteers and that through their service on the commission, they can become

experts in land use.

“Commissioner Sease seems to be attempting to manufacture a controversy out of a demonstrably non-controversial statement,” Middleton wrote. “In the context of a land use discussion, asserting that ‘everyone is an expert at something’ is a non-sequitir [sic]. We’re not talking about some things, we’re specifically talking about land use. My comments had nothing to do with any commissioner’s general base of knowledge.”

As another example of disregard for the planning commission’s expertise, Sease cited the way in which some city council members explained their votes during a recent annexation hearing.

The case involved a proposed development of more than 500 single-family homes on a 200-acre parcel along Virgil Road in Southeast Durham. The planning commission’s 10 members unanimously opposed the proposal in January, with nearly every commissioner citing the development’s projected environmental impact, especially on the water quality of Falls Lake, as a reason for their dissent.

The proposal and associated proffers— community benefits that developers tack on to make projects more amenable—that came before the city council on May 20, and that the council approved in a 4–3 vote, “did not substantively change” from the one that the planning commission had opposed unanimously, according to Sease.

Sease wrote that the Virgil Road development will be in an “area carrying the heaviest burden at present in terms of rampant suburban-style, disaggregated, environmentally degrading, almost exclusively residential, auto-dependent development.”

“Those words are not jargon,” Sease wrote. “They are qualitative and technical descriptors—choices—choices being endorsed favorably by Council.”

Middleton, mayor Leonardo Williams, and council members Carl Rist and Javiera Caballero voted yes on the proposed development.

In explaining his vote, Rist said nutrient pollution and algal blooms are a “serious issue for Falls Lake” and seemed to suggest that clear-cutting hundreds of acres of trees and vegetation would alleviate the issue.

“Fifty-six percent of nitrogen that gets into Falls Lake comes from forest and agriculture,” Rist said at the May 20 meeting. He cited data from a study that a board member from the Upper Neuse River Basin Association (UNRBA) presented to council members during a work session on May 9.

“[But only] 1 percent of nitrogen comes from stream bank erosion,” Rist, who is the

council delegate to the UNRBA, continued.

“For phosphorus, the other nutrient we measure closely, 54 percent comes from forest and agriculture. Fourteen percent comes from stream bank erosion. So we have to be clear about what the impacts are in Falls Lake, and the data shows that there is some erosion that happens, but that much more is coming from forested land and agriculture.”

Sound Rivers, an environmental conservation group that monitors the Neuse and Tar-Pamlico River watersheds, debunked Rist’s argument in a Facebook post.

“Unfortunately, councilman Rist left out one key part of the picture,” Sound Rivers wrote. “Forests perform a key role in water filtration. In fact, according to the University of North Carolina’s Falls Lake study, forests are responsible for filtering out 81% of nutrients that would otherwise make their way into the lake. The science agrees that one of the most effective strategies for protecting water quality and drinking water use of Falls Lake is to protect the remaining forest areas in the watershed.”

In a statement to the INDY, Rist doubled down on the assertion that “the largest source of nutrients in the lake (ie, nitrogen and phosphorus) comes from unmanaged lands and ag,” but he emphasized that he “at no point” suggested that “getting rid of natural forests and natural areas would somehow make the lake better.” He noted that UNRBA staff expressed its own

issues with Sound Rivers’ post and directed the INDY to a presentation that said, in UNRBA’s opinion, that the post provided incomplete context about how development affects Falls Lake.

Rist said his comments during the debate were misrepresented in the Facebook post, adding that “the same group of opponents” that opposes development in southeast Durham opposed the Virgil Road case in suggesting that development in that part of town is destroying Falls Lake.

Sound Rivers also posted a response to a remark Mayor Williams made while discussing the Virgil Road annexation at the May 20 meeting. In explaining his yes vote in the wake of pushback from environmental activists, Williams said, “Falls Lake is a man-made lake. It was made, what, back in 1981? And it was jacked up when it was created. If it was made then, it will be made again. I don’t think the lake is going anywhere.”

“Mr. Mayor,” Sound Rivers wrote on Facebook, “Falls Lake is the drinking water supply for half a million people. It is not ‘jacked up,’ and it is not your dumping ground.”

In a phone call with the INDY, Williams, who acknowledged his remarks at the May 20 meeting “could have been a little bit animated,” said they were in response to council member DeDreana Freeman’s comment that Falls Lake is “disappear[ing]” in part due to the impacts of overdevelopment.

“The lake is not going to disappear, it’s

not going anywhere,” Williams says. “There are a lot of claims that the development is the cause of Falls Lake being the way it is, and my point was, no, it is not the only cause. Falls Lake has been an issue for decades.”

He says Sound Rivers “found it to be quite convenient to only take a segment of what I said and put it in one of those scary political videos.”

Regarding Sease’s resignation, Williams says, “It’s unfortunate, but I think it’s a misunderstanding.

“We have to take [the planning commission’s] information and let it inform us, but it does not dictate our decisions. That is also fact. And facts cannot be offensive.”

Williams says that, ultimately, developers will build on properties they own whether the council approves a proposal or not.

“You’re gonna either build by-right, or we’re going to approve the zoning request and we’re going to build for what they requested,” Williams says. “But there will be building. There seems to be this misperception that if the council says no, then the [developer] can’t build. No. It just means that they’re going to build less.”

Williams says in his prior term as a city council member, he called a meeting between the city council and the planning commission due to a “lack of communication between the two bodies.”

“I need to do it again,” Williams says. “I’m going to do it again.” W

It’s the season of vacation reads, of frothy paperbacks by the Eno and overambitious nonfiction tomes weighing down tote bags. The Triangle has no shortage of talented writers, and we’ve been hoping to do a special reading issue for some time now—what better time than summer?

As fate would have it, though, the books that happened to come across our desks belie the beach-read feel of this issue’s cover: shadows supplant sunny skies, and within these author profiles, interviews, and book reviews, there’s deep childhood trauma, a few cults, and a good bit of murder in the mix. If breezy reads are what you’re looking for, I can’t promise that this particular issue will deliver them. But if you’re open to swampy Southern noir—and to be honest, a pretty on-the-nose reflection of the political uncertainty and existential angst of the times we’re living in—then I hope you’ll spend some time with the local talent in these pages.

From the deft character studies of Carrboro writer Joanna Pearson, a psychiatrist by day, to the wrenching memoir of writer Stephanie Clare Smith, a Raleigh poet and social worker, the writers featured in this issue demonstrate how effectively, in good art, light and dark can undulate off one another. Not to be too cliché, but the genre makes for an appropriate time to reference Flannery O’Connor, who once wrote: “Fiction is about everything human and we are made out of dust, and if you scorn getting yourself dusty, then you shouldn’t try to write fiction.”

To balance out the mix, you’ll also find stories about the redemptive role of basketball, the value of supporting comics and zines, and how reading together (even silently!) can foster community.

Sarah Edwards INDY Culture Editor

by Diane Oliver

The tragedy is obvious. Twenty-twoyear-old Diane Oliver, from Charlotte, educated at the North Carolina Women’s College (UNC-Greensboro), a prodigious talent at the famed University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop, killed in a motorcycle accident in 1966, just days before her graduation.

Her posthumous short-story collection, Neighbors and Other Stories, released this past February by Grove Press, is an extended eulogy. Tayari Jones, award-winning novelist and current grande dame of Black Southern literature, laments, in the collection’s introduction, that she didn’t know Oliver’s work before receiving a simple advanced copy, “printed on plain paper, no intriguing cover, no laudatory blurbs from great writers.”

Jones was knocked down immediately.

Part of Diane Oliver’s tragedy, yes, is the promise of unfulfilled talent. She only published a handful of stories in her lifetime, in Sewanee Review and Negro Digest. She wasn’t a fallen star. She was an incredibly gifted writer on the path to greatness.

The titular story in Neighbors, an intimate look at the integration of an elementary school, won an O. Henry Award in 1967, the same year Joyce Carol Oates won the award’s First Prize for the story “In the Region of Ice.” John Updike won First Prize the year before; Flannery O’Connor, the year before that; John Cheever in 1964. Imagine what Oliver would have produced if she lived, at least, as long as O’Connor’s too-short brilliance. Imagine her exchanging wit with Joyce Carol Oates on social media.

Although the realistic “Neighbors” is her well-known effort, Oliver’s skill is most evident when she leans into surreality. The stories “The Closet on the Top Floor” and “Mint Juleps Not Served Here” read

like fables. In the former, the first Black student at a college undergoes a mental break, shrinks from the world, and ends up living in her closet, as fellow white students view the strange behavior as proof that “colored people aren’t like us.” The latter is a spooky tale about a family living deep in a forest preserve, off the grid. “The best story, however—the one where Oliver forces you to understand her potential as a generational stylist—is “Frozen Voices,” an experimental, musical story about death, love, and betrayal in Michigan. Here, she writes with real maturity, pulling off sentences and refrains more seasoned writers would stumble on or avoid entirely. Sentences run like poetry, such as, when one character dies and another searches for the parents: “Searching back, remembering old faces, lost, seasons, but shivering in the winter, the echoing fragments of time

now frozen solid in the earth. I could do nothing.”

We’re never really grounded, the way we are in her other stories. The bravery is close to music and painting. It’s thrilling.

One can easily imagine an alternate universe where Oliver miraculously survives the motorcycle crash or decides, at the last minute, to catch a ride with someone else. We can see her continuing to thrive at Iowa, getting slowed down after graduation by real life. Money. Needing it. Losing it. Family, maybe, intruding on her writing time. Cruel societal expectations curbing her focus, as happened with many talented woman writers of her generation. Or perhaps we might imagine her in the current generation of MFA graduates—a few short stories in the New Yorker, Paris Review, a six-figure two-book deal, short-story collection followed by a novel, prizes and longlists, optioned for film by a commercially viable director, all culminating in a light-workload tenured job at an MFA program.

These permutations do a tremendous disservice to Oliver. The 14 stories collected in Neighbors are excellent enough to exist without tragedy. Their moral clarity is proof that young people can already possess a true vision of the world. Take “Frozen Voices.” We can easily imagine a world where an editor, agent, professor, or mentor discourages Oliver from experimenting. To return to the success of “Neighbors,” to write the same story with slight variations over and over, to write a novel that expands on the world and style of her traditional stories.

We shouldn’t solely mourn the lost future. We should celebrate the purity. The joy of a young voice ripping across the page, undaunted. —Gabriel Bump

Lindsay Starck

In Gravity and Grace, a posthumous collection of Simone Weil’s philosophical reflections, she observes, “Imaginary evil is romantic and varied. Real evil is gloomy, dull, and boring. Imaginary good is boring; real good is always new, marvelous, intoxicating.”

Is this still the case today? Or has the internet killed the romantic appeal of so-called evil monsters? This question is posed in Lindsay Starck’s new novel, Monsters We Have Made. Starck, who is now based in Minnesota, graduated from UNC-Chapel Hill and is the author of Noah’s Wife

The novel begins in 2008 with hikers calling 911 after finding a teenage babysitter stabbed by two nine-year-old girls in Durham’s Eno River State Park. This haunting incident serves as a portal, propelling readers into the intricate web of emotions between Sylvia and Jack, two soulmates turned estranged by their nineyear-old daughter Faye’s puzzling descent into violence.

The true villain in this story is the Kingman: a faceless figure who lures children into the forest toward his kingdom in the North Woods of Minnesota. He haunts, as Starck writes, “the dreams of parents flung across the country, the monster who emerged from the Fertile Crescent and stalked through shadows of the centuries, sliding through civilization after civilization, story after story, until he found us.”In the present day, the Kingman—who is based on Slender Man and Susan Cooper’s “boggart”—can be found in numerous rabbit holes and chat forums. Following this fictional Eno River State Park tragedy, more children attempt to murder adults who get in their way of their search for the Kingman.

The narrative airlifts in and out of the

stabbing’s aftermath and a new development, 10 years later, when four-year-old Amelia is abandoned in a parked car in a Durham grocery store. Her parents are nowhere to be found, so the police take Amelia to her next of kin—Sylvia.

In literary telenovela fashion, Sylvia and Jack are reunited to take care of Amelia and locate the little girl’s mother—their distant daughter, Faye, who is again on a quest to find the Kingman.

While this may sound borderline nightmarish, Monsters We Have Made is actually, somehow, a feel-good story. Even though the characters encounter difficult experiences in North Carolina, they also zoom around the state—from coast to mountains—in such a dreamy

way. Sunny flashbacks among butterfly migrations and coppices reveal how sweet Sylvia’s and Jack’s lives were before the stabbing incident. Furthermore, Sylvia is a gentle bibliophile and hardcore romantic.

In the second half of Monsters We Have Made, the narrative begins to feel as if the author is withholding information about Sylvia when her loved ones— namely her Minnesota-based sister— abandon Sylvia during the hardest passage of her life following her daughter’s juvenile indictment, an abandonment that is portrayed as justified. Is there something other characters are seeing about Sylvia that is obfuscated from the reader? Then again, sometimes sisters just suck.

Starck’s deep love of language is evident: the characters choose their words carefully and etymological breakdowns are seamlessly woven into the narrative. The role of stories is explored through free-standing references to historical and literary snapshots depicting “vanishing children” throughout time. The investigation into what makes a monster scary is explored in equal measure to what makes love scary.

In fact, characters often choose to spend their time looking for a monster instead of rebuilding bonds with their loved ones.

The darkest territory of the book is the shifting landscape of online manipulation. Monsters We Have Made has hit the bookshelves within months of the US surgeon general’s call for warning labels on social media sites. Imaginary monsters may be romantic, but the online ones are a different story.

—Veronica Kavass

by Mesha Maren Algonquin Books | May 21

Fear, identity, love, and addiction are some of the visceral elements readers will explore in Mesha Maren’s novel Shae, published last month by Algonquin, in which the namesake narrator experiences a teen pregnancy with a trans partner. If that plot sounds unique, the novel’s strength is rooted in its utter relatability in the face of dramatic circumstances. At the end of the day, this is a poignant coming-of-age tale that explores falling in love, experiencing heartache, and making hard decisions when you’re young.

This is the third novel by Maren, an associate professor of the practice of English at Duke University and a former Kenan Visiting Writer at the UNC-CH. Maren grew up outside Alderson, West Virginia, in an Appalachian community much like the one we find in the narrator’s hometown.

Shae, which follows 2019’s Sugar Run and 2022’s Perpetual West, is Maren’s latest in a run of Southern noir novels. Maren has mastered writing flawed characters who wrestle with big questions; the powerful storytelling seen in this novel wonders, “Who am I? What do I want?”

The novel’s namesake narrator, Shae, is a West Virginia 16-year-old who doesn’t have it easy: a teen pregnancy derails her life, and she takes on unsavory pursuits that stem, in some part, from a blooming opioid addiction that she got from post-birth pain medication. It’s a compassionate lens into addiction, where pills are dispensed freely to Shae.

“That first time, there in the hospital, was the best Oxy I ever had, and since then I’ve always been trying to get back,” Shae says at one point. As a reader you ache for the teenager, as Maren artfully weaves together the many complicated parts of her young life. You don’t have to relate to her exact experiences to understand what

it’s like to be a 16-year-old dealing with fear, heartache, and an uncertain future. Her partner, Cam, meanwhile, explores what being trans in the rural South looks like. Both teenagers struggle with questions about belonging and their place in their family and community. The novel explores the nuances of coming out (and having loved ones come out), with Shae fretting, “Cam was transitioning right under her nose and Mom pretended like nothing was happening …. And I didn’t say a goddamn thing.” She juggles early motherhood while trying to understand how to support her partner, with Cam stating plainly at one point, “I’m not me when I’m here.” Cam, meanwhile, has firsthand experience with addiction and her own fears: she knows better than anyone that addiction has consequences.

Maren reminds us that growing up is hard and confusing. This compelling novel manages to wrap itself in myriad important themes, including death, motherhood, incarceration, shame, and addiction, but is never heavy-handed. Shae learns that the high doesn’t last forever: After all, what (and who) is left when the dust clears? Facing this question, situated in a coming-ofage story about first love, allows the novel to offer both an important queer voice and a strong Southern voice. It is a novel that carries its numerous identities well.

The prose is gritty and flows so easily that Shae is hard to put down. It may be a powerful coming-of-age exploration, but it’s a story for everyone. —Katie Mgonglwa W

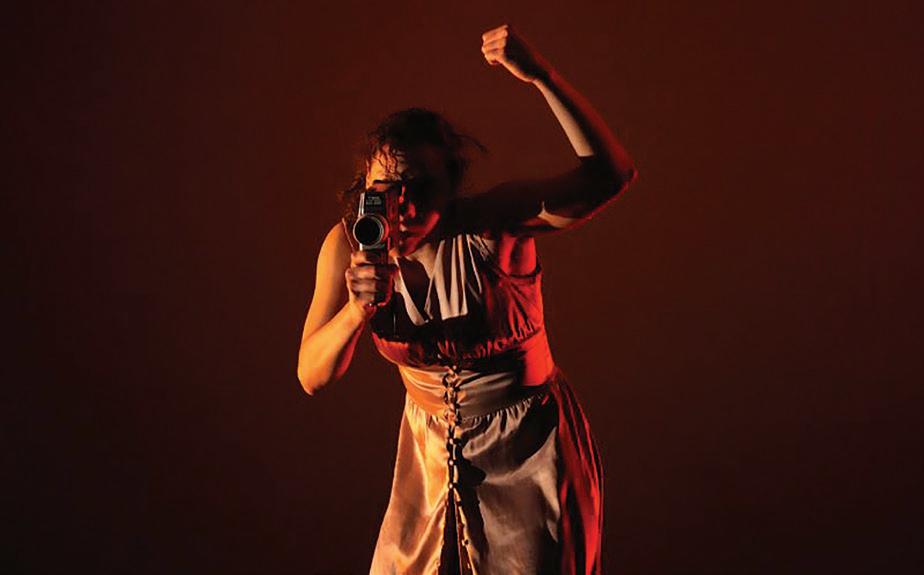

Carrboro author Joanna Pearson’s debut novel deals with the long, haunting aftershocks of a college campus murder.

BY SARAH EDWARDS sedwards@indyweek.com

Much has changed in Chapel Hill and its centerpiece public university, over the years, but it can still feel frozen in time.

Cresting Franklin Street on my way to meet the writer Joanna Pearson, one recent morning, I spot an older woman kneeling by a row of sorority houses, trimming rose bushes; a block or so away, students with backpacks slung low over Carolina blue T-shirts mill in front of Sutton’s Drug Store. Farther still down the road, a man with dreads bound up in a red bandana crosses the street to Carrburritos.

The indelible feel of a college town is captured in Pearson’s debut novel, Bright and Tender Dark, a dense, variegated literary thriller about the Y2K-era murder of Karlie Richards, a college student who seems to dazzle everyone around her. The book begins from the perspective of Karlie’s freshman-year roommate, Joy, who recalls, in the

opening paragraph, Karlie’s instructions for how to fend off an attacker: “Fall to the ground, froth at the mouth, growl, fling your arms, spout gibberish.”

This is a real conversation that Pearson, who grew up in Western North Carolina and graduated in 2002, remembers from her time at UNC-Chapel Hill.

“Even at this idealistic flagship university, girls were still trading tips like this,” Pearson recounts over coffee at Carrboro’s Weaver Street Market. The memory served as a starting point for Bright and Tender Dark, which was released this month by Bloomsbury Publishing.

It’s Pearson’s first novel, but she’s been writing steadily since her undergraduate creative writing days: After graduating UNC, she went on to pursue an MD from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, adding in a poetry MFA from Johns Hopkins along the way. Since then, she’s shifted from poetry to short fiction, authoring two

award-winning short-story collections: Every Human Love (2019) and Now You Know It All (2021). Some of her stories have appeared in anthologies, including 2023’s Best American Short Stories; recently, she was awarded a grant from South Arts as part of its inaugural class of State Fellows for Literary Arts.

This novel is another excursion—this time into something longer—though, as Pearson puts it, “you can see the short story DNA in this book,” and that’s true. The writing is taut and self-contained, the energy of each scene spinning tightly on its own axis. Some chapters read as if they could stand on their own.

Set at UNC, Bright and Tender Dark deals with the long aftershocks of a campus murder. It begins in 2019, 20 years after the crime, when Joy discovers an unopened letter from Karlie that throws the murder (and subsequent conviction and imprisonment of a mentally disabled local man) into question. Other things, what Pearson calls “textual artifacts”—emails, true-crime Reddit forums, college papers—break up the narrative, which moves between the perspectives of numerous (too numerous, perhaps) other characters, seesawing between 1999 and 2019.

There’s Maggie, a real estate agent and the new wife of Joy’s ex-husband; KC, who works as the night shift manager at the off-campus building where the murder occurred; and Jacob Hendrix, the religious studies professor who was close—too close—with Karlie before her death. All are haunted, in one way or another: by the loss of Karlie, by religious repression, by the loss of the life they expected to live.

“I set out thinking this is gonna be a story about storytelling,” says Pearson. “I knew I wanted it to be polyvocal, a story about how we tell stories.”

Before falling under the spell of the philandering religious studies professor and entering a rebellion, Karlie begins her time at UNC a bright and dewy-eyed believer. She “collected lip glosses flavored like pineapple soda and endorsed books that argued godly young women

should refrain from kissing anyone until their wedding day.” (This, as anyone familiar with early-aughts evangelical culture knows, is a reference to Joshua Harris’s popular courtship manual, I Kissed Dating Goodbye.)

In life Karlie is magnetic; in death, even more so. There’s nuance to the magnetism—she bears “an undeniable avarice,” “the great, gaping imperative that she be liked, preferred”—but it’s apparent how readily the conditions around her death turn her into something reified, like Twin Peaks’ Laura Palmer, haunting the generations after her.

In her 2018 essay collection Dead Girls: Essays On Surviving an American Obsession, the writer Alice Bolin tracks a dark genre that spans media from Pretty Little Liars to The Lovely Bones, and an obsession with murdered, silenced women. It’s a genre distinctly shaped by racism and misogyny (both fictional Dead Girls and their reallife counterparts that receive attention are pretty much always thin, white, and cisgender), with Bolin noting that these stories are driven by a “haunted, semi-sexual obsession” with “the highest sacrifice, the virgin martyr.” They’re forms as one-dimensional as a cheerful woman in a mid-aughts Old Navy ad. Once you learn about Dead Girls, you’ll see them everywhere.

This framework is helpful for evaluating true-crime fiction (and how or whether it’s done responsibly), of course, though the mitigating factor here is that sometimes the crimes are true. The trope often offers space for dark topics that don’t always see the light of day: power, predation, domestic abuse. Dead Girls are real, violence against women endemic, the metal grip of a key between knuckles familiar.

And UNC-CH is haunted by its own campus tragedies. To name just a few: There’s the unsolved murder of Suellen Evans, a student taking summer classes at UNC who was stabbed in Coker Arboretum in 1965 as she fought off a rapist. In 1970, James Cates, a young Black Chapel Hill resident, was stabbed to death in the UNC Pit by members of a white motorcycle gang when he attended a dance marathon event—a crime that’s largely been whitewashed from UNC history.

In 2008, student body president Eve Carson was murdered, followed just four years later by the 2012 murder of UNC sophomore Faith Hedgepeth, a member of the Haliwa-Saponi Tribe. My own years at UNC were bookended by the tragic murders of Carson and Hedgepeth and the tension from the tragedies was palpable. The ripple effects of the fictional murder in Bright and Tender Dark feel authen-

tic to those kinds of community-wide experiences, though Pearson is quick to note that she didn’t base the book on any real incidents.

Marya Spence, Pearson’s agent at Janklow & Nesbit Associates, wrote in an email that she appreciates the book for its “obsessive, spiraling exploration of predation” and “the anxiety of public identity; and our ultimate complicity in continuously feeding the spectacle of tragedy.”

By day, Pearson is a psychiatrist, and that’s maybe the most helpful detail for capturing what works so well about her writing. In an interview with UNC’s English and Comparative Literature, she spoke about the kinship between writing and psychiatry: “I also thought a lot about character [at UNC]—what people want, what motivates them, why they do what they do, their backstory—and language as a tool, both of which have turned out to be awfully relevant now to me as a psychiatrist.”

Pearson’s previous story collections, which largely circumnavigate the lives of North Carolina women, tread dark psychological water—menacing encounters, fundamentalist extremities, postpartum psychosis—and her professional expertise shines through in these sharp psychological portraits.

“I’m not a true-crime girlie,” Pearson says. “I have an appetite for mystery but not necessarily a capacity.”

Bright and Tender Dark isn’t a Tana French novel, and if you’re looking for a traditional thriller, you won’t find many such Gone Girl or Sharp Knives twists. Nevertheless, it’s a gripping read and Pearson’s observations—particularly about girlhood, social anxiety, and millennium-era evangelical culture—will stay with you for a long time, adhesive like sticky summer residue.

Bright and Tender Dark begins with the perspective of Joy, the freshman-year roommate whose disposition belies her name, and whose mind anchors the story. She’s not a protagonist you encounter very often—she’s middle-aged, divorced, and obsessive to the point of self-destruction, as she tries to reopen the case and tumbles into the online true-crime community—but Pearson’s insight into her character is keen and assured. Somehow, Joy pulls you forward.

That assurance makes the encounters with hope and insight all the more rewarding—as when Maggie, the real estate agent, finds a moment of reprieve.

“The shape in the darkness is, for the time being, gone,” Maggie narrates. The light “shoots from her fingertips and toes and onto everyone, onto the whole, lost world.” W

Seeking community and structure, more and more people are attending the ultimate “happy hours for introverts”—Silent Book Clubs.

BY AVERY SLOAN arts@indyweek.com

On a recent evening in Durham, on the second floor of Letters Bookshop, the room is hushed. Two people sit reading; neither is talking or reading the same book, but they are there together—sort of.

It’s the second Tuesday of the month, one of the two evenings that Letters hosts a chapter of the Silent Book Club hour (the other evening is the fourth Thursday of the month). Described as a “happy hour for introverts” on its website, the Silent Book Club (SBC) has over 1,000 chapters in 50 countries. The event, as its name implies, provides a quiet place for people to come together and independently read.

When it comes to the books landscape, things are mixed: There were 2,599 independent bookstore locations in the United States, for instance, as of 2023, according to a survey by the American Booksellers Association done by Statista, a number that’s been steadily increasing since 2009 when only 1,651 independent bookstore locations were recorded.

But the picture is also more complicated. According to the same survey, with the convenience of online stores, fewer people are buying books in stores. Overall, bookstore sales have also decreased—in 2022 sales amounted to less than $9 billion, whereas a decade earlier sales were over $12 billion. However, community efforts like book clubs seem to be growing. According to

ticketing platform Eventbrite, book club event listings grew by 24 percent in the United States from 2022 to 2023, and the platform Meetup saw a 10 percent increase in book club listings.

At Letters, the reading hour is split in two: It begins with a nonsilent time for socializing, in which readers can start the book club by chatting about what they’re reading and what kinds of books they’re interested in, before phasing into an independent reading time.

An activity like a silent book club—with contradiction implied in its name—is an intriguing proposition. We’re living in an increasingly atomized era where things come right to our doorsteps and our phones. Why leave the comfort of home to participate in a solitary activity, of all things? But perhaps living in a less social world is exactly why people want to join a silent club.

On June 10, the two participants who showed up to Letters, William Page and Tierra Flowers, both happen to be fans of fantasy and science fiction. Flowers came for the first time to try a new low-stakes activity. She’s reading Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life, a novel she found through TikTok. Before attending an SBC, she says that social media was the closest space she’s had to a community of book lovers. She’s enjoying A Little Life, she says, and is

about halfway through, an admirable dent in a 700-page book.

“I just love the escapism of it,” Flowers says. “I can definitely get lost in a good book.”

Flowers says she’s searching for the right book club to join. While her friends enjoy reading, she says, it’s not to the same extent that she does, and she wants to find other active readers to talk about books with.

The other SBC participant, Page—who is also an employee of Letters—says that he enjoys the opportunity to read communally without being confined to reading a certain book.

“I don’t think reading should be something that anyone is stressed about,” Page says.

Flowers agrees with the sentiment: once she has a deadline and a certain number of pages to read, she says, it takes the fun out.

Blackbird Books and Coffee in Raleigh also has an SBC chapter. Shop co-owners Bre Brunswick and Hannah Brunswick started it because they both felt it was the kind of book club they themselves would want to be a part of, Bre Brunswick wrote in an email to the INDY

Blackbird’s SBC meets twice a month and usually has around 25 or so people show up, Bre Brunswick wrote.

“It was always meant to be a social

event but with a very specific structure,” Bre Brunswick wrote. “I’ve found that most people really thrive when there are super firm expectations—especially when they are trying something new.”

Durham’s Night School Bar found that this similar structure, with space for accountability, can be helpful for students in the form of a writing hour. The organization, which offers classes to adults on a range of topics in the arts and humanities on a sliding scale, has a silent writing hour—similar to SBCs.

The hour began when Night School Bar writing workshop participants expressed an interest in a larger writing community, owner Lindsey Andrews wrote in an email to the INDY—a time for people to come together and focus on individual writing and goals. On the bar, a card catalog contains writing prompts and index cards on which people can outline their goals.

“They can meet other writers, find motivation, or just keep themselves accountable and feel good about making and meeting goals,” Andrews says.

At Letters, the silent reading hour began earlier this year. The number of people ranges, but the activity itself stays the same, Page says. The club’s origin story was simple, he adds: “The people that started this say it just started as—‘Hey, do y’all want to go read somewhere?’” W

Raleigh writer Stephanie Clare Smith’s new memoir contends with the pain, escape, and recovery following a traumatic childhood abduction.

BY FRED WASSER arts@indyweek.com

Ihave at least one thing in common with North Carolina–based writer Stephanie Clare Smith: we share a fascination with Harry Houdini, the great magician, escape artist—and keeper of secrets. “Harry Houdini said that his audience never saw the hours of torturous self-training it took to overcome fear and master the illusion,” Smith writes in her new memoir. “They saw only the miraculous way he held it together.”

The book is set in the summer of 1973 when Smith was a young teenager, alone, and living in New Orleans. Her mother was on a cross-country road trip. “A mile walk to the K&B on the day after the Fourth for a cheeseburger and cola seemed like a small thing I could do,” Smith writes. Instead, the 14-year-old was abducted while she walked along Saint Charles Avenue. The man drove her in his pickup truck to a nearby park and raped her at knifepoint.

“Every escape exacts its own price,” Smith writes in Everywhere the Undrowned: A Memoir of Survival and Imagination, a memoir of trauma, escape, recovery, and the winding, crooked path of secret-keeping. Published earlier this year, Smith’s book is the first in a series of literary nonfiction works to be published by Great Circle Books, an imprint of UNC Press.

INDY: You are a survivor, and I think that’s what you mean by “undrowned.” Not only surviving the assault, but your life.

STEPHANIE CLARE SMITH: I play around with that word. The word “undrowned”—it has a lot of different meanings. One is

how I was able to swallow my feelings and survive this assault. There’s that kind of survival. My memoir is about how sometimes you sink and then swim. And what is that like? There are so many survivors of so many kinds of things. I learn something from every single person’s survival story. And if someone can learn something from mine, great.

What sorts of reactions have you gotten to the book? It is very heavy. To the point where I had to periodically stop and catch my breath. Even though I’ve never gone through what you’ve been through, there are things I could relate it to in my own life.

A lot of people tell me that. I was so focused, when the book launched, on the writing. Is it good enough? Are people going to understand it? I didn’t expect this other thing. I’m 65. If I was younger, it would be impossible for me to have my life so exposed. It’s the complete opposite to how I’ve lived. This was my story. I spent most of my life running from it. But I’ve gotten to a certain place where I feel like I’m looking for a place to land the plane. That’s what makes it possible for me to stand in front of people and talk about it and do readings. Otherwise, it could be really, really challenging. It’s been quite an evolution to go public with it.

When you were a kid, you lived a very internal life. That was something very interesting to me about the book—I was inside

your head. You were neglected as a child, but you felt the need to protect your mom. That’s a common feature of neglected children, right?

Very common.

What’s the psychological mechanism at work there?

Love. We’re wired to love our mother, to love our main caregiver. My young mind would do anything to keep her close and take the blame. We’re wired for connection and we’re wired to survive. As a kid, you’ve got to please your tribe, because you don’t want to be left behind. I didn’t have lots of allies or support. My mother was the most reliable thing. And yet she was incredibly unreliable. Very erratic, but charming. She was like an intellectual Judy Garland. She was a free spirit. People wanted to be around her.

At the end of her life, you were her caretaker. Did you come to a peace with her at the end?

You know, what’s funny—it’s not funny—I had all her undivided time. She had dementia. It was this horrible irony that finally she stopped moving away from

me. What I’ve finally done now is see a much more holistic view of my mother that does involve a lot of compassion. I also have a lot of sadness and frustration at the way I was raised.