CAPTURING THE SURREAL: DISPARATE DIMENSIONS

By Jemma Salisbury

Capturing the Surreal, a recent exhibit on view at InLiquid Gallery, manifested alternate realities as artists created vibrant dreamscapes using photography, virtual reality, claymation, and 3D animation. Three artists – Charmaine Caire, Kelli S. Williams and Eva Wu – molded the gallery, so that reality became more augmented and virtual as one moved through the space. Capturing the Surreal aimed for viewers to confront their relationship with – and their influence on – the reality around them.

Fabrication and distortion is a tool used by all artists in their work, not only in theme but in practice. Charmaine Caire staged miniature realities to photograph, allowing

Exhibition view, InLiquid Gallery

the viewer a window into an illusory realm. Her methods included chromogenic prints, Cibachrome prints, handpainted, and hand-printed pigment ink prints. While photographing, she used hotlights and gels to manipulate the atmosphere and color of her work. Chromogenic prints involved film with several layers of silver halide emulsion. Cibachrome was a chemical process, which reproduced film onto photographic paper. This printing technique ensured lasting color and vibrancy, evident in her work Barbie Amongst The Flowers.

Caire’s work welcomed viewers into the exhibition, placed along the wall leading to the gallery’s entrance. Though the works themselves spanned from 1997 to 2018, they seemed timeless in their beauty and affect. The scenes created, from a Barbie in a painted frame of flowers, to a drive-in movie with plastic flies as attendees, all have a dreamlike quality to them. A self-proclaimed world-builder, Caire’s pieces often inhabit the realities/fantasies one creates in childhood. Nicknamed by her friends as the “surreal juxtaposer,” inspired by folk art and the likes of Duchamp and Jean Arp, Caire used found objects, each one a symbol that called out to her. Often from the 50’s and 60’s and reminiscent of her own childhood, she manipulated the objects into a scene to achieve the “appropriation of images in order to make something else completely different.”

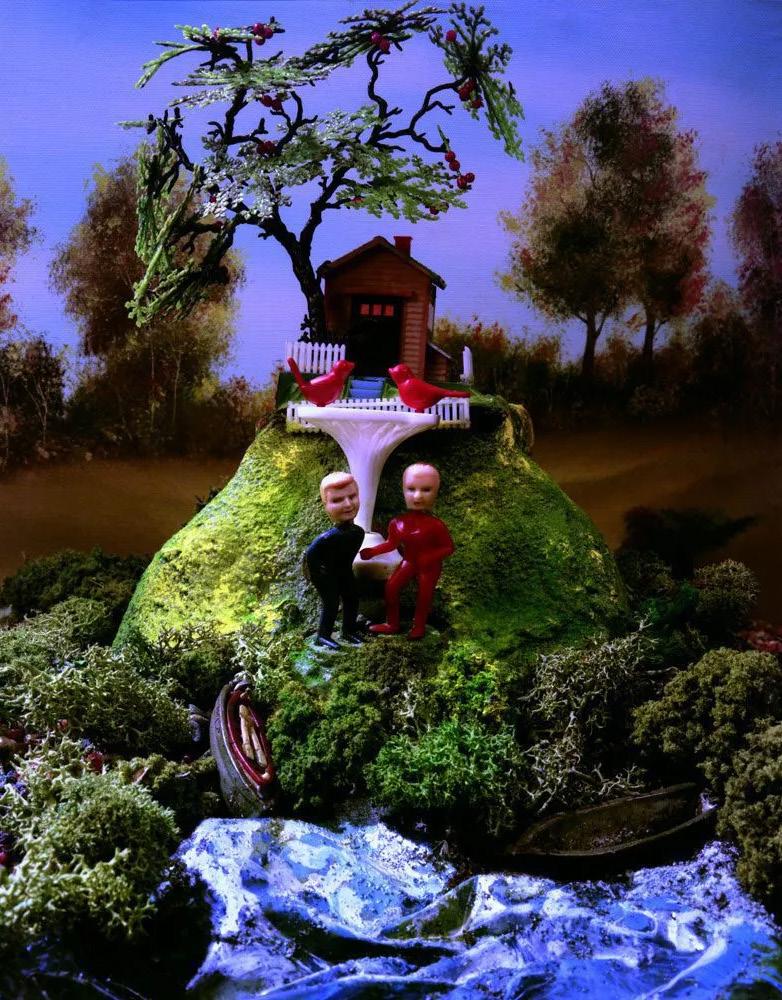

A personal favorite of this writer is Jack and Jill (1999). Caire photographed the scene using a large format film camera. She then enhanced and changed the colors by using a 20x24 enlarger which projected the prints onto the floor. In this piece, the classic childhood fable is not brought to life, but to another reality. In front of a fuzzy, yellowtinged landscape, a small house perches atop a hill with a plasticine tree bearing red berries. In the foreground, our Jack and Jill stand in front of a busy bird bath. They have

pale heads, dark eyes and mouths, and monochromatic plastic bodies, in red and blue respectively. At their feet, on the base of the hill lies two discarded boats. They rest on the bank of a river made of blue patterned cloth.

The colors are organized so that familiar greens and yellows surround the unnatural reds and blues of the central composition: leading the viewer away from the familiar and towards the dreamscape. The contrasting dark and bright colors and the silence of the still frame emphasizes that the viewer is outside their realm of understanding. At the same time, the playful and familiar subject invites further exploration. Here, the surreal inhabits the space between the viewer and the artwork, where, out of the corner of their eye, one can swear they see the river move and the birds fly. The narrative blends with the viewer’s imagination to inspire a new reality. It is an apt example of the technique Caire uses in most of her works

Charmaine Caire, Jack and Jill (detail)

which she calls the “Stop and Think” method: Her goal is to create scenes that give the viewer “jumping off points to finish the story” using their mind’s eye. She further applied this method by giving her works open-ended titles — and signing each on the verso — after their completion, aiming to give the viewer another spark of familiarity or inspiration.

Kelli S. Williams opens the door further through her work in augmented reality. She created movement in her pieces using claymation, which involves photographing her figurines after moving them in miniscule increments countless times. Although her work looks like static portraits and group photos at first glance, their subjects move when viewed through the app Artivive. By filming the art through the lens of a phone, the app allows artists to create a visible, digital layer on top of a physical piece of artwork.

In Williams’ Onlooker series, one claymation doll is reinvented for each of the six portraits. With different hairstyles, make-up, and outfits, Williams created characters inspired by cultural movements like afropunk and black dandyism. The figures move backwards, getting “un-ready” before putting their hair in place and posing for their picture. This logistical choice to create a seamless viewing experience had the effect of highlighting Onlookers’ voyeuristic viewpoint. While observing someone getting ready might have been a private experience two decades ago, it is now another example of the invasive and blurry boundaries of social media’s sphere (evidenced by the “get ready with me” trend of recent years).

The physical process necessary to view the work emphasized its theme of the surreal landscape of social media. Through pictures and videos, users fabricate an online reality, sometimes involving a fictional version of themselves for the world to experience.

This was most evident in Williams’s series Kids in America (2022). Three large, landscape-oriented frames sat on the wall opposite the gallery entrance. The characters in Kids in America live inside the world of social media — something that is “not quite real but also not quite fake.” Four girls in cheerleader and partygoer outfits in neon reds and greens stand before a stark pink background. The floor in each scene is varyingly littered with red solo cups, balloons, and shoes. While claymation brings Williams’ figures out of their faux-candid poses, seeing them move through a screen in short, boomerang-type movements accentuates their manufacture. Williams spent multiple months on each phase of creation,

Exhibition view, InLiquid Gallery

from logistics to set creation. Inspired by the Mean Girls stage play, she used one set and three different set dressings to create scenes inspired by the 2000’s movies Williams grew up on. She explored the influences these movies had on her generation concerning the idea of aging in the age of social media. As If, She Doesn’t Even Go Here, and Send is Paolo are unified through their pink background and iconic soundtrack. “Supermodel” from the movie Clueless plays slower and more distorted with each piece. As If was inspired by the aforementioned movie and the hopeful song “speaks to [its] ... time period.” However, the ending piece (Send is Paolo) speaks most poignantly to transformation. Its clever reference to The Princess Bride expresses the desire to metamorphize. At the same time, this “makeover” expresses how many in the social media age put on a facade or invent an image to achieve this goal.

While the augmented reality brought Williams’ claymation to life, it also more starkly revealed her subjects’ separation from reality. The figures only exist “alive” through a viewers’ screen, emphasizing the modern-day reliance someone has on social media to give them a feeling of validation and livelihood. As the figures’ realities are distorted from stationary to enlivened, the viewer’s reality is distorted as they are transported into a vibrant, hand-made world. Looking at William’s work makes one feel like both the observer, and the observed, posing the question of which reality — the viewers’, or the claymation figures’ — is in fact more surreal.

Finally, Eva Wu’s work fully immersed the viewer into another reality. Her series, An Extension of Eva’s World (2024), is a 3-channel 3D animation, or a video split between three screens placed vertically next to one another. Using online 3D modeling and taking inspiration from virtual reality and game design, Eva’s World presented a wholly constructed, alien environment to the viewer. 3D

animation involves modeling digital objects and fabricating their three dimensional movement in what is really a two dimensional screen. Wu used the application Autodesk Maya, building the world “piece by piece” before bringing in camera movements to guide viewers through the landscape. Like Caire and Williams, Wu’s work blurs the boundaries of what a reality or dimension is, not only in her artwork, but also in her creative process.

The landscapes on the three screens easily connect and diverge, much like the reasoning of dreams. The use of three screens gives the impression of three doorways into the same world (or are they?). Three main forms in the piece — the sky, mountains, and ground — shuffle their colors on each screen. Adding to the otherworldly character of the piece, Wu defies the laws of our nature by rotating these planes, adjusting the shapes and textures so each “portal,” though slightly different, would form one cohesive piece.

At the end of the work, the slow moving landscape is obstructed by the sharp, angular forms of a crystal portal before the video loops back to the beginning. The scene depicted was actually taken from a longer film of Wu’s. For this exhibit, Wu extracted one scene from a longer work that originally included characters. They chose this scene for its elaborate camera movement which enlivens the environment. This, combined with the absence of humanoid figures in the scene, invites the viewer in to walk through and inhabit this new world for themselves. Going through Wu’s crystal portal could “be an opportunity for the entire environment to change.”

The obvious divergence from reality is not unsettling but compelling, even pleasing, giving the viewers a chance to look into a utopia of color. Bright pinks, oranges, greens, and a white background with Chinese characters meld together to create something so far from the viewers’

reality that it appears beautiful.

The bright colors were fabricated to look unnatural and vivid. 3D modeling softwares are usually engineered to depict “colors that exist in our real lives,” and so creating the colors in this work, especially the saturated pink, was a challenge. However, Wu made it clear that their work is meant to exist in “the fantastical world,” and therefore the colors they use are not meant to look realistic.

Exhibition view, InLiquid Gallery

The neverending landscape, forever moving, implies an absence of time, a constraint that often defines the limits of one’s day to day reality. The piece provides an opportunity to revel in the surrealty of bearing witness to a world so divergent from one’s own. The characters mentioned above form a poem the artist wrote for their mother. “A meditation on gratitude,” it expresses Wu’s desire to fulfill and exceed their mother’s “deepest wishes” for her, to be happy and live a life free of shame.

When envisioning a utopia, Wu pictured a world in which everyone experiences freedom, love, and community. Through peering into this world, viewers are given the gift to be temporarily transported to a new realm, full of unexplored curiosity. When looking in, perhaps viewers can picture a utopia of their own.

Through exploring different mediums, colors, and subjects free of the constraint of logic, the artists of Capturing the Surreal have created worlds made of dreams. Their work asked viewers to open their minds to the possibilities reflected in the worlds living just on the edge of ours. Using a variety of traditional and new-age techniques, the exhibit guided viewers through time, space and dimension, shining a light on the constraints and blinders of our everyday realities by revealing the dimensions beyond the naked eye. Their work acts as a gateway into those dimensions through imagination and contemplation.

Exhibition view, InLiquid Gallery