7 minute read

DESIGNWIRE

On January 1, 2021, the world collectively turned the page, hoping to leave the hardships of 2020 behind. To symbolize forward momentum, New Year’s Day was also when the Moynihan Train Hall in New York was unveiled. The monumental civic project has been decades in the making; it was 1998 when Skidmore, Owings & Merrill began on it with a goal to evoke the Beaux-Arts majesty of the original Pennsylvania Station across the street. The hall, named after late New York senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who proposed the project in the ’90’s, occupies 225,000 square feet in the landmarked James A. Farley Post Office Building (where Facebook has leased office space). Among its glorious features is a vaulted skylight, akin to what had capped Penn Station, composed of 500 glass and steel panels that traverse the entire space. Perhaps equal in breathtaking qualities is the art program: three permanent site-specific installations, one each by Stan Douglas, Elmgreen & Dragset, and Kehinde Wiley. The latter’s is a celestial stained-glass triptych fusing Renaissance painting and 18th-century ceiling-fresco styles with Black women and men breakdancing. It crowns the nearly 30-foot ceiling at a main entryway. “Unlike the mythological figures of Renaissance ceilings,” Public Art Fund director and chief curator Nicholas Baume says, “Kehinde’s subjects have the athletic skill to defy gravity, celebrating the joyous expression of Black bodies in motion.”

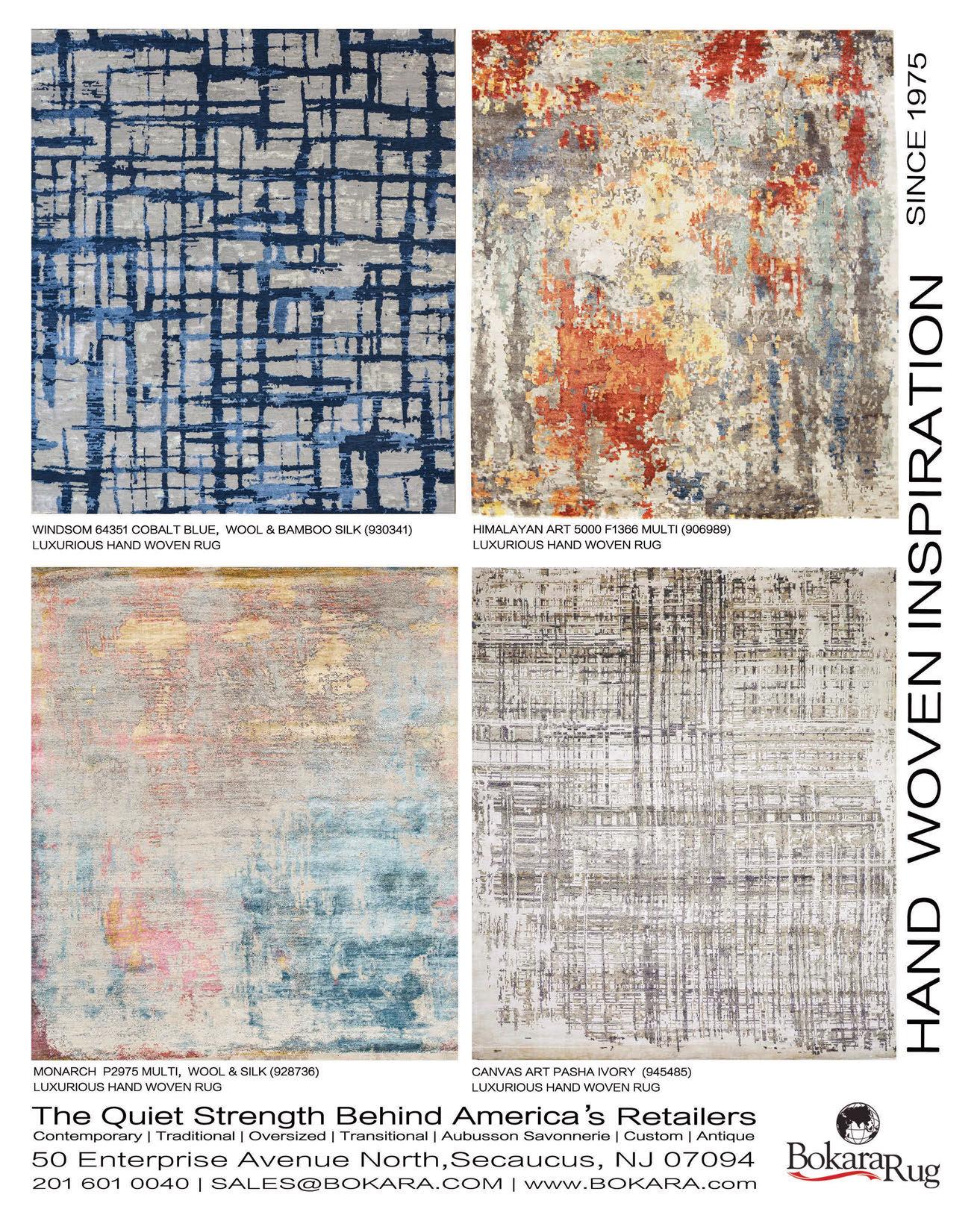

Go, Kehinde Wiley’s 55-foot-wide triptych in hand-painted stained glass and aluminum, surrounded by decorative gypsum molding, and backlit by an LED panel, was commissioned by Empire State Development and Public Art Fund for the 33rd Street midblock entry to New York’s Moynihan

Train Hall by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, with areas by Rockwell Group, FX Collaborative, and Elkus Manfredi Architects. upward and onward

To honor Black History Month, we’ve devoted this section to projects, exhibitions, and awards won by Black architects, artists, and designers

JONATHAN MOODY, CURT MOODY

towering success

Moody Nolan—the nation’s largest African-American owned and operated design firm, with more than 230 staff members in 11 offices across the U.S.—has received the 2021 AIA Architecture Firm Award, the highest honor the organization bestows. Founded

From top: Ohio’s Columbus Metropolitan Library Martin Luther King Branch is a 2018 project by Moody Nolan, recipient of the 2021 AIA Architecture Firm Award. The firm’s Miamisburg, Ohio, headquarters for the Connor Group, a real estate investment firm, completed in 2014.

in 1982 by Curt Moody, FAIA, NOMA, and the late engineer Howard E. Nolan, the firm exemplifies the belief that diverse perspectives foster creativity and more responsive solutions. The wisdom of that ethos is revealed in a multisector portfolio of distinguished projects that combine an astute awareness of cultural sensitivities with a subtle understanding of the impact its work has on individuals and communities. Outstanding examples include the 18,700square-foot Columbus Metropolitan Library Martin Luther King Branch in Ohio and the 300,000-square-footCenturyLink Technology Center of Excellence in Monroe, Louisiana. Beyond compelling buildings, Moody Nolan sees its mission as fostering architecture careers in diverse communities and extending its legacy. Fitting, then, that Moody’s architect son Jonathan is the firm’s CEO.—Peter Webster

by Rachel & Nicholas Cope for KnollTextiles

From top: In the public spaces of the new Manhattan headquarters of 1199SEIU United Healthcare Workers East by Adjaye Associates, a 1930’s mosaic by Anton Refregier at the union’s old headquarters was recreated by artist Stephen Miotto, after moving it proved impossible. The Martin Luther King Jr. mural, created by transferring a photograph from the union’s archive onto tile. Under a barrel-vaulted GFRG ceiling, Stephen Alcorn’s 1990’s image of abolitionist Frederick Douglass printed on tile and fronted with bronzed-aluminum letters.

designwire

The 400,000 membersof 1199SEIU United Healthcare Workers East, the country’s largest healthcareworkers union, founded in 1932, have not had an easy year. But the completion of the public spaces in its new Manhattan headquarters was a high point. Sir David Adjaye, the Ghanaian-British architect, designed the project’s 16,500 square feet of lounges, galleries, meeting rooms, circulation routes, and library as a permanent celebration of the union’s 90-year fight for social justice and quality healthcare for all. The Adjaye Associates founder, renowned for his Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, recently moved to Accra, Ghana, in part to be near several important projects, including a vast national cathedral there as well as a museum in Benin City, Nigeria. But the union headquarters was hardly an afterthought. A trip to Mexico reminded him of the power of public murals and introduced him to a technique of transferring images onto tile by Cerámica Suro so exacting that even the amount of grout used is considered. “This is the first time I’ve used murals like this,” Adjaye says. But it won’t be the last; he says he’s working such “supergraphics” into other projects. One of several such murals at the 1199 facility is a soaring portrait ofMartin Luther King Jr., who called SEIU the “authentic conscience of the labor movement.” Another is a likeness of abolitionist Frederick Douglass, bearing his timely quote: “If there is no struggle, there is no progress.”—Fred A. Bernstein

The Cherner Chair Company

this girl is on fire

Talk about a shooting star.Gio Swaby, a Bahamian multimedia textile artist, earned her BFA in 2016. The very next year, she mounted a solo show at UNIT/PITT Society for Art & Critical Awareness in Vancouver, BC, where Swaby now lives. The 29-year-old is kicking off 2021 with similar brilliance: “Love Letters” is her exhibition of over a dozen new works at Claire Oliver Gallery in New York. “Medium is one of the last things I think about,” the artist, who studied painting, drawing, and ceramics as well as film and video, recently said. For her Pretty Pretty series, the medium is thread and cotton. “They reference female-centered activities like sewing, plus the concept of tradition, which is echoed in the theme of Black women passing down hair-care traditions for generations.” Swaby’s creations are, as noted in the exhibit’s title, a love letter to Black women’s style, strength, beauty, individuality, and humanity—and underscore joy and resilience overall.

Clockwise from top: Pretty Pretty 1, 3, 4, and 2, all in thread and cotton fabric on muslin and over 6 feet tall, are among the new works by Gio Swaby in her solo show at Claire Oliver Gallery in Harlem, New York, opening February 27.

GIO SWABY

designwire

a cut above

The Seattle Art Museum is giving its first solo exhibition of hometown artist Barbara Earl Thomas, who is also a former director of the city’s Northwest African American Museum. “The Geography of Innocence” is a poetic distillation of Thomas’s longtime concerns: light and shadow, perception and knowledge, Black lives and experiences, and the nature of empathy. The show comprises two parts: an immersive, single-room installation and an adjoining galleryof portraits. In the former, three walls are sheathed in backlit, intricately cut Tyvek panels, creating a lanternlike glow. Each wall includes a central “altar” in the form of a glass portrait and candlestick. Similar panels cut with detailed imagery form a 12-foot-tall luminaria in the center of the room. Hanging in the neighboring hallway, 10 portraits—in cut black paper with hand-colored backgrounds—depict people involved in the artist’s life. “My goal is to disarm,” says Thomas, who trained as a painter and printmaker at the University of Washington, where she earned her MFA. “It’s a portal into a place where you are surrounded by beauty and pause to take in the complexity of the stories being told.”—Peter Webster

designwire

BARBARA EARL THOMAS