Front cover, detail of Clematis Pods, Encaustic, clematis pods, tree pods, sweet pea pods, pistachio shells on wood 24 x 24 in by Lauren Lipinski Eisen

S. Kay Burnett Executive Editor Wax Fusion

Lyn Belisle Vice President

Regina B Quinn President Social Media Director

Michelle Robinson Exhibitions Director

Melissa Lackman Grants Director

Paul Kline Member-at-large

Mary Jo Reutter Treasurer

Rhonda Raulston Secretary Tech Director

Philip Johnston Member-at-large

Melissa Stephens Membership & Chapters Director

Front cover, detail of Clematis Pods, Encaustic, clematis pods, tree pods, sweet pea pods, pistachio shells on wood 24 x 24 in by Lauren Lipinski Eisen

S. Kay Burnett Executive Editor Wax Fusion

Lyn Belisle Vice President

Regina B Quinn President Social Media Director

Michelle Robinson Exhibitions Director

Melissa Lackman Grants Director

Paul Kline Member-at-large

Mary Jo Reutter Treasurer

Rhonda Raulston Secretary Tech Director

Philip Johnston Member-at-large

Melissa Stephens Membership & Chapters Director

As artists, where do we find seeds of inspiration and what do we do with them? Which ones do we keep and nurture and which ones do we discard? Is dormancy also part of the creative process? For this issue we invite artists to share ideas about how they germinate their seeds of inspiration.

Lauren Lipinski Eisen finds inspiration in her garden. She embeds seeds she has harvested and incorporates metal objects into the painting to contrast the delicate organic forms of the seeds and the ethereal quality of the wax medium. Isabelle Gaborit favors the silent, dark days and nights of winter. She closes the doors to her studio and goes to the Burren along the west Clare coastline to wander “boreen” of the beaten tracks in search of inspiration.

Lorraine Glessner uses travel, hiking, and responding to her surroundings as inspiration for her work and provides information on how to organize a selfmade residency, find inspiration, and record your environment. Patricia Rossetti's work exemplifies how found and represented objects symbolize our engagement with nature as we navigate living, loss, aging, and grief and as we imagine what can yet become of them. Melissa Stephens understands how life provides unexpected inspiration. When her sister was diagnosed with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS or Lou Gherig’s Disease), many of her paintings translated into visions of hope, life’s unpredictability, and living in the moment. Alicia Tormey’s guidelines for navigating the seasons of creativity can help artists understand their creative flow and the seasons that dictate the rhythm of their studio practice so that they can capitalize on what each state inherently contributes.

We hope you enjoy reading this Germination issue of Wax Fusion. And, as always, we appreciate your feedback. Please contact us at WaxFusion@InternationalEncaustic-Artists.org with comments, questions, ideas, and suggestions. While this journal exists to serve the needs of IEA members, it is also free and available to the public. You are welcome to share this journal with anyone interested or working in the visual arts, looking for information on encaustics, or beginning to explore the world of encaustics.

S. Kay Burnett Lyn Belisle Paul Kline

As a gardener, I look forward to the process of planting seeds each spring and excitedly await their germination. This annual ritual initiates the reawakening of the garden and begins the seasonal cycle of plant life.

As a backyard hybridizer, harvesting the seeds created by cross-pollinating cultivars carefully selected to pass their blended characteristics on to a new generation of ofspring is, at the culmination of the cycle, an even more ardent expression of hope, wonder, and promise of new creation in the garden.

As an artist, my work is inspired by my fascination with the hybridizing process. Developing new cultivars capable of producing subsequent generations of plants, each with their own distinct combination of characteristics, compels me to continually reflect on the cycle of birth, life, death, and regeneration.

Clematis Pods, Encaustic, clematis pods, tree pods, sweet pea pods, pistachio shells on wood, 24 x 24 in Also featured on the front cover

I embed seeds harvested from the garden as well as seeds packaged as dried food items into the surface of my paintings, using the translucency of encaustic medium to showcase their fragility. This variety of sourced seed material draws reference to a range of the stages of plant life, from embryos to postharvest products processed for mass consumption.

Contrasting the delicate organic forms of the seeds and the ethereal quality of the wax medium with the incorporation of metal objects into the paintings suggests a mechanical/industrial presence infiltrating and isolating the natural landscape.

Clematis Pods was inspired by a species of vining flower that is native to many parts of the world. In the development of recently cultivated varieties of clematis, the size of the flowers has continually increased with successive rounds of hybridization.

The feathery seedheads are very delicate, wispy creatures, light enough to be carried on the wind to eventually plant themselves in a new location. Larger and sturdier pods of trees and sweet peas included in Clematis Pods emphasize the role of encasement, contrasting the fragile, hair-like, easily dispersing clematis seeds with more rigid pod containers armored with pistachio shell caps.

Hybridization/Reversion, Encaustic, metal, paper, grasses, clematis pods, linen on wood, 24 x 24 in

The title of Hybridization/Reversion refers to the continued hybridization of plants producing cultivars that are farther and farther removed from the original species.

Offspring from these hybrid cultivars do not come true from seed, meaning that if a seed from a cultivar is planted, the result will not necessarily resemble the mother plant, but will more likely revert to characteristics from its ancestors.

The composition of Hybridization/Reversion plays with the concept of the family tree, as larger seedheads from more elaborate clematis hybrids revolve around a central, more modest seedhead from a species clematis. Wire-ring halos surround each seedhead, while metal springs wrap around grass-plume branches woven throughout the painting.

In the center of Regeneration, a cluster of dried heliotrope

flowers stands representing the metaphorical Tree of Life, with its reflection mirrored in gold below. Arranged progressively from simple species to more complex hybrid forms, various stages of clematis seedheads are surrounded by DNA-referencing spring coils floating through the sky.

The seeds emerge from the center and cycle upward, outward, and downward, plunging into a blue sea of wire springs and dried plant matter, until they are recycled, regenerated, and eventually released back up into the golden swirling sky.

Emergence and Return reference not only the recurring cycles of plant life, but also our initial entry into and emergence from isolation during the pandemic.

An underlying grid in these works, formed by individual square sections of quilted fabric wrapped around the supporting panel, isolates each individual clematis seedhead into its own compartment.

In Emergence, there is an upward movement created by a pyramid of simple species clematis seedheads, and in Return, an inverted downward movement integrates more complex, tangled, hybridized clematis seedheads as they parachute back to earth.

Like the progression of hybridization and seasonal cycle of plant life, my artmaking process also unfolds in a way that cumulatively melds components from previous works, resulting in new combinations that in turn generate new cycles of creation.

Encaustic, clematis pods, quilted fabric on wood 18 x 18 in

Return, Encaustic, clematis pods, quilted fabric on wood, 18 x 18 in

Lauren received an M.F.A. from Tulane University and a B.F.A from Columbus College of Art and Design. She has shown her work in galleries in London, New York, New Orleans, San Francisco, and Denver. She has participated in exhibitions at The Marin Museum of Contemporary Art, The Butler Institute of American Art, The SUNY Art Museum in Plattsburgh, and The Masur Museum of Art. Lauren’s work has received many honors and awards and is included in several private, corporate, and public collections. She currently teaches painting and drawing at the University of Northern Colorado and has also taught painting and drawing at Denison University and Columbus College of Art and Design.

You can view Lauren’s work at www.laureneisenart.com

www.instagram.com/laureneisenart

www.facebook.com/LaurenEisenArt

"You are getting the keys in two weeks."

This sentence, somehow trivial to most sounded like a alarm. A wake up call.

An unwelcomed deafening sound in the middle of the night, while you are warm and comfy, snuggled next to the love of your life, without a care in the world.

In two weeks, I am moving my encaustic studio in Connemara, a wild place located the furthest western part of Ireland. New location. New place. New growth. All that is familiar just dissipated.

Time to wake up girl! Winter slumber is over. Spring out of bed: Time to plant seeds.

For most of us, springtime is all about birds, more light in the morning, snowdrops, and growth.

In Ireland, we call this season “imbolg” which signifies in Irish “In the belly.” In the warm darkness of the womb of the earth, seeds are incubating slowly, waiting to grow and greet the sun.

In this Island, we are welcoming spring with open arms, pregnant with so much potential, but more importantly, we are waking up from the slumber of winter, the necessary incubation time and silence those seeds needed.

Under the earth.

Where life starts.

When most people get their inspiration in the summer, where the sun and our personal energy levels are at their heights, I favour the silent, dark days and nights of winter.

I find comfort in its muffled silence. Its long nights and slower paced days. This is the time when the Muse and I get to know each other, or shall I say, reconnect.

Summer in the Wildfire and Wax studio is bursting with workshops, art retreats, mentoring sessions, and exhibitions. So many faces, so much enthusiasm, so many adventures and discoveries in many venues scattered around Ireland. I welcome them all wholeheartedly.

However, one cannot be active at all times, and just like the cyclical quality of nature herself, I welcome the slower months as a necessary time set apart for me, myself, and I, that is, my body, my mind, and my soul. Three of us reunited and given the opportunity to align once more away from the hustle and bustle of life. This brings balance in my life and in my artistic practice.

Inspiration does not come easy for me; she needs to be fed and the winter offers me the time to wander this Island and uncover her gems. There is no better place for me to go and find myself than the Burren along the west Clare coastline. Unapologetically wild, raw, and bare to the bones.

I close the door of the studio; my paints, pigments, and boards can wait. Now is the time to fill my cup.

Traveling to that special place resembles a pilgrimage, of when I drive through the layers of my personal history which are imprinted into the ancient landscape: a face, an event, a word, a song, a story, an emotion. Each of these memories remain there for me to reveal and savor them once more, one at the time.

My car knows the way and within 1 hour or so, I am wandering “boreen” off the beaten tracks, where nobody wanders, almost unwelcoming, yet curious. Yet, if you decide to push on, these places lead you to the most exquisite wells and ruins, haunted by the voices of the winds.

This land dwells in my blood and bones.

It is otherworldly and the light shines from within for those with the eyes to see. Let’s strip it back

Then you may ask… what happens next?

Having travelled regularly to this unique landscape has shaped the way I approach my own artwork with encaustic painting and my creative process. Once I am back in the studio can be the polar opposite to my meanderings in the wilderness.

Akin to the job of a gardener, my job is to make sure that those “seeds of inspiration” gathered during my meanderings via pictures and quick sketches of color swabs will receive the right amount of selection, care, and attention. This process requires no compromises and my approach to studio work tends to be very methodical and disciplined.

Not all seeds will grow. Not all seeds should grow and choices do need to be made to prepare the garden and tend the soil.

One of the recurring queries I get during my workshops and something which also applies to me and so may artists out there is how to select a colour palette. We all know that encaustic paints can be very seducing, and one can easily turn their artwork into an explosive colour bomb.

The way I have been selecting colors for years can seem unconventional, but has worked miracles for me and has become a little ritual I indulge into each time I start a new series.

The day I decide to work on a new series, I set half an hour to browse through gathered images and make note of the colours which appeal the most. I personally love browsing through Pinterest and selecting in a folder the artwork I like the most (based on colors, textures, and tones). I try not to think too much during this selective process and use it as a meditative tool.

After 30 minutes or so after this selective activity, I open my folder and look at the images selected and search for the recurring colours or tones. The “golden thread” as I call it. Ten times out of ten, these will reflect my likes of the moment. I do trust this part of me, call it unconscious or instinctual, and I do try to build my color scheme around my likes.

This little exercise can also be done while I go for walks or during my meanderings in the Burren. I take hundreds of images, not really thinking about it and apply the same process when I am back in the studio.

You may also discover with this simple process that your taste in colour will change according to your mood or emotions.

I once was more attracted to the flow of water, as I am now more attracted by the textures of the rocks and the geology of the area in a more monochromatic palette.

Estuary, Encaustic on birch cradled board, 8 x 8 in Featured on the Content pages

My experience of the natural forces and the cyclical nature of the land around me has also shaped my creative process and the physicality of art making.

I am particularly interested in the geological processes that have built up layers overtime, layers of the past that the harsh weather is slowly breaking down and revealing overtime. I think of my art process very much akin to those geological processes.

Like the natural forces that shape this unique and unwelcoming landscape, I approach each of my new work as a cyclical process. Each painting goes through numerous stages of building up, construction, destruction, growth, and decay.

As the paintings go through the physicality of what could be akin to an archaeological process, layers of pigmented beeswax are built up, scrapped back while cooled, scored, and shaped, creating highly tactile surfaces. The way I stand, the way I hold my brush, the way I use my whole body to make marks is also a huge conscious part of my process.

As the clouds and rain batter this coastline and shape it to their powerful willful force, remnants of what has come before are left as a new landscape unfolds.

And the cycle keeps on going.

Sharing my experience of art making has been an integral part of my creative practice. Even though teaching encaustic painting requires the sharing and understanding of a particular and practical set of rules, techniques, and safety issues, a massive part of my role as a teacher or mentor is to give my students the time and the space to be inspired, to know how to “gather seeds,” and be confident and free enough to explore their creativity with focus and clarity.

I have been thinking a lot about the various teachers and mentors I have had the honour to meet along the way, and those who have made a lasting impression are those who have given me the time and space to be me. The real me. Our mundane lives are so busy and distracting, one of the best gifts one can give to oneself is self-care, the sacred time put aside when one can be oneself, without interruption or distraction.

One of my students who comes each week for a two-hour session, once stopped in her tracks while painting. She looked at me and said.

“This. This is what I was looking for.”

“Can you explain?” I asked.

“The fact that I have not had a thought in a while,” she replied.

I understood what she meant. She had found her bliss, her flow and was at one with herself and her creativity, away from the hustle and bustle of life, and she was riding that beautiful wave where all that matters is our connection to something that is higher than ourselves, a place of plenitude and peace, a beautiful garden, full of potential.

Neither Here Nor There, Encaustic on birch cradled board, 11.8 x 11.8 in

Isabelle is a professional visual artist who was born in La Rochelle in the southwest of France, but currently resides in Ireland. As a student she gained a foundation in sculpture, drawing, and painting at l’Ecole des Beaux Arts in Poitiers, France, and graduated in 2006 with an honours degree in fine arts in Ireland.

Since then she has been exhibiting her work extensively nationally and internationally, in the US, Northern Ireland, China, and France.

In 2022, her essay entitled Living in a liminal world, was part of a new anthology The Art of Place: People and Landscape of County Clare, which placed a particular emphasis on the role of landscape and environs, bringing together 30 captivating personal stories by some of the most creative people in Ireland, who all live in or come from County Clare.

Isabelle has extensive and active knowledge in facilitating art workshops, gained from over 20-years experience and is accomplished in conducting group workshops and demonstrations live and online, while mentoring artists during private one-to-one sessions in her own studio.

You can view Isabelle’s work and learn more about her workshops and art retreats at isabellegaborit.com isabellegaborit.com/category/workshop/

www.facebook.com/isabellegaboritencausticartist www.instagram.com/isabellegaboritencaustics/ www.pinterest.ie/isabellegaborit/

I have been organizing self-made residencies annually since 2019. After many dollars and hours spent applying for and being rejected from numerous traditional artist residency programs, I decided to save application fees and spend them on a residency that I made myself. I’ve also had “mini” residencies at home during COVID, during workshop travels, and during the past two summers, while teaching my encaustic retreats in Vermont. The best thing to realize about organizing a self-made residency is that there is an alternative to traditional residency programs, you don’t have to rely on them exclusively. Further, you don’t have to rely on having a studio, an awesome place or even inspiration (whatever that means to you) in order to make art. You can make art anywhere and gather your inspiration from just taking a walk in your immediate surroundings. In this article, I share with you how I use travel, hiking, and responding to my surroundings as inspiration for my work in the hopes that you will also be inspired to create art anytime, anywhere.

During my first self-made residency, I discovered hiking/walking as an art practice. It’s been said that Beethoven always walked with a notebook, as the act of walking helped him to work out his themes.

In the book Mapping: The Intelligence of Artistic Work by Anne West, she writes, “Somewhere I read ‘where the feet walk centers poetry.’ This is another way of saying that by placing the mind and body in movement it is possible to approach the heart of things from another direction. Walking helps to ignite the senses and to open self to external stimuli. To walk is to cultivate a wandering intelligence where we are placed in fresh relationship with the world and happenstance. When walking, thoughts are allowed to be free. We entrust ourselves to chance. Anywhere, anytime the unpredictable may appear. All we need to do is stay open to it.” 1

My work is rooted in landscape and the body, so inserting my body and intentionally experiencing the landscape with it is a goal. During my residencies, I literally walk five to seven miles a day, always in a diferent place with various terrain. Beach, forest, swamp, stormy, sunny, hot, cool, hills, flat… Northern Florida in January has it all. Navigating weather, wild animals, and sometimes rough terrain helps me to become more connected to the place, my thoughts, and myself. Hiking and photography have always been a part of my work. The act of focusing on a subject and taking a photo somehow records it in my head, and it becomes a part of me. Taking many photos of the same subject really burns it into my head. It’s like the beginnings of a plein air sketch.

Additional inspiration images taken on hikes during my 2019-2021 Florida self-made residencies.

1 West, Anne. Mapping: The Intelligence of Artistic Work. (Maine: Moth Press, 2011), p#89

One thing that photographs help me do is focus on the small things, to notice little things in the landscape that otherwise would go unnoticed. (top left and right)

I also notice and collect little treasures… (middle left and bottom left and right)

Sometimes I keep them and other times I arrange them on the trail. I’m no Andy Goldsworthy,2 but I have fun finding little things and arranging them. Like the photos, I see these simple installations as drawings or plein air sketches that better help me to know the place and for the place to know me.

2 Andy Goldsworthy is a contemporary English sculptor, photographer, and environmentalist, who produces site-specific sculptures and land art situated in natural and urban settings. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Everywhere I hike I sit, sometimes in several places. Once I find a place I always meditate, then I write, and then I paint. During my first Florida residency, I first began making plein air watercolors, but this became a bit overwhelming. Just by doodling in my sketchbook, I came up with two simple exercises that helped to map these places — horizon contour drawings and palette paintings.

The contour drawings started a few years earlier while I was in Utah teaching a workshop. We made plant brushes, dipped them in ink, and traced the contour of the landscape.

The idea was to create images of landscape using actual parts of the landscape. Using the structure of the initial contour lines, I connected them — like walking through the drawings but with lines. I then added patterns from the landscape and strangely enough, the drawings actually took on the overall rhythm and carved look of the terrain.

So believe it or not, these drawings were actually done a year before this photograph was taken, but the similarities are uncanny. I don’t look at the hiking photos while I paint. In fact, I rarely look at them again after I take them. It always amazes me how my photographs and paintings intertwine in my head.

Contour drawings of Florida and photograph of the Florida landscape taken two years after the drawings were made.

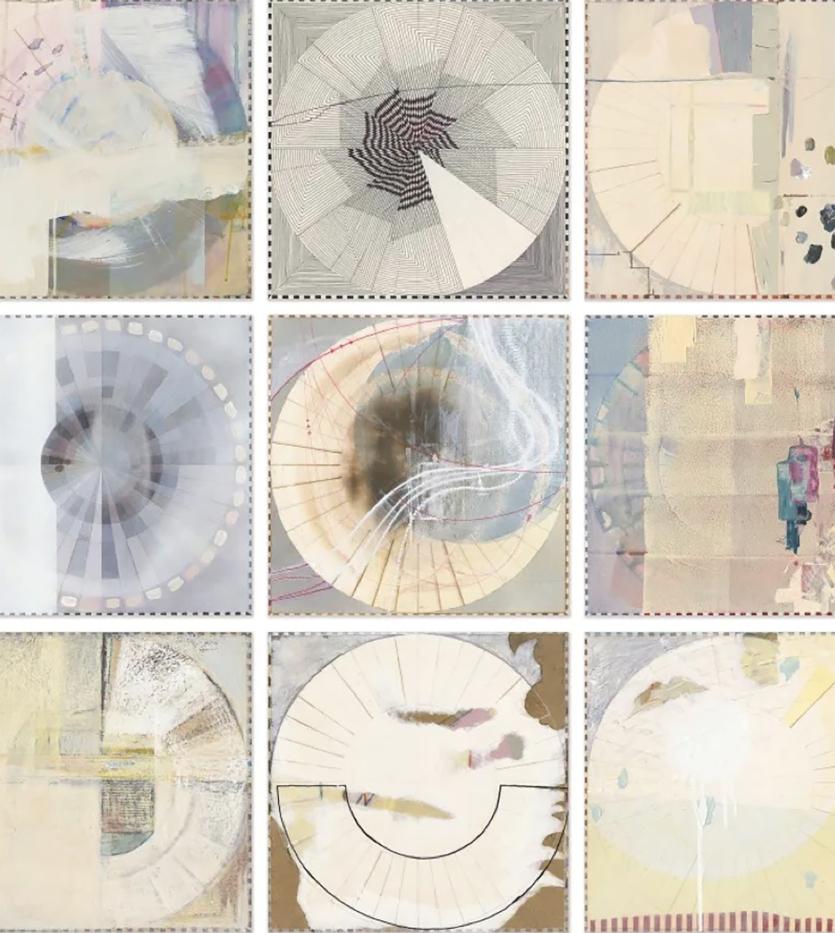

The palette paintings came about as a way for me to record the landscape without actually painting landscape. I had been really inspired by Ellen Heck’s Color Wheels series.3 Heck is actually a printmaker and narrative figurative painter. She created the wheels as “both a visual journal and a systems based color study,” and for her, they grew into an ongoing series of abstract works.

I hadn’t really planned to do anything like this, but I did remember the series out on the trail. I made circles with my bottle cap and ovals from some packaging I had, and there was my structure. To paint my palette, I simply choose a small section (sometimes as small as a square inch) of the landscape and paint all the colors I see in it, rather than painting the whole of what’s in front of me.

Please enjoy these palette painting examples and read on for instructions on how to glean inspiration out on the trail.

3 “The Color Wheels project is both a visual journal and systems-based color study. I have used the wheels as a foundation for creating large, sometimes serial, seemingly-abstract works, many of which are multiple-panel compositions. The wheels for each grouping are intaglio printed from the same plate, and serve as both a sub-structure and not-so-blank slate. I begin by considering one wheel at a time, often finding a particular theme for a panel and behaving as if it were a stand-alone piece. The wheel lends itself to organizing information, and I have used panels to chart the color of the surface of the San Francisco Bay over time, break apart master works to examine their components, and document a series of self-assigned systems that are often a chimerical mix of process and play.”

ellenheck.com/portfolio/color-wheels

By Permission of the Artist By Permission of the Artist

By Permission of the Artist

Palette Painting done in plein air while hiking, watercolor, gouache on paper

1. Take a walk, experience it with all of your senses. Take photos as you go - anything that catches your eye. You may never use these images or even refer to them again, but looking, framing, and focusing with the camera, pressing the shutter - all of these actions actually work together to create a recording that informs your creative mind.

2. When you feel the time is right, settle in a spot and experience it through all of your senses. Listening, breathing, looking, touching, tasting, smelling for 10 minutes as a form of meditation. Try to time your breathing to the wind, water, and sounds in the environment.

3. After 10 minutes of quiet meditation, spend 10 minutes freely writing and creating a narrative of this environment. Pay particular attention to the rhythms, patterns, repetitious sounds, sights, smells and what kinds of emotions they evoke in you.

4. Horizon Contour Drawing:

a. Stare at the horizon line and from as far left as you can see, follow it with your eyes to as far right as you can see, repeat a few times.

b. Now, with your finger in the air, trace that same horizon line from left to right. Do this three times.

c. Now with any sketching material, trace this horizon contour in your sketchbook. Draw it multiple times on the same page, allowing the rhythms of the place to direct the rhythm of your drawing.

d. Begin adding in other rhythmic details such as sounds, objects, tactile qualities — use symbols, marks, text, and color.

e. Draw for 20-30 continuous minutes, creating as many drawings as you like.

f. Make a note on the drawing: where you are, date and time of day.

5. Palette Paintings of the Environment:

a. Trace around a bottle cap or a quarter, something small that you can carry in your backpack. Make 10 circles or squares of the same size in your sketchbook. Choose an area in your environment (as small as an inch square or as large as several square feet).

b. Map all of the colors you see in your chosen area using watercolor, gouache, or watercolor pencils.

6. Combine a Contour Drawing with a Palette Painting to further inspire your mapping and recording of a place.

7. Take these recordings back to the studio and work back into them with further painting, collage, drawing or use them as a basis for a painting series.

Want to make art on the go with me and three other encaustic instructors? Join me this summer in June, July, or August for my Vermont Encaustic Retreats. Visit this link for descriptions and registration. www.lorraineglessner.net/workshop-intro

Digital Catalog for exhibition, With Wax: Materiality & Mixed Media in Encaustic, curated by Lorraine Glessner and held at the Chester County Art Association, September, 2022.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q8TYC6_joPY&t=96s

A tour of one of my self-made artist residencies in Florida, January, 2021.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uUnXDdXHG10

Next page left, Winter Light Series 8, Encaustic monotype, 13 x 9.5 in R&F Brown Pink Residency, 2022

Next page right, Winter Light Series 5, Encaustic monotype, 13 x 9.5 in R&F Brown Pink Residency, 2022

Lorraine is a former Assistant Professor at Tyler School of Art, a workshop instructor, and an award-winning artist. Lorraine’s love of surface, pattern, mark making, and image has led her to combine disparate materials and processes in her work such as silk, wood, wax, pyrography, and rust. Recent professional achievements include curating With Wax: Materiality & Mixed Media in Encaustic at Chester County Art Association in West Chester, PA; a Grand Prize Award from the show (re)Building, Atlantic Gallery, New York, NY; and a recently appointed position as a Tier Artist at R&F Paints. Her work is exhibited locally and nationally in galleries, museums, craft centers, universities, fine art shows, and more. Lorraine brings to her teaching a strong interdisciplinary approach, mixed with a balance of concept, process, experimentation, and discovery.

You can view Lorraine’s work at www.lorraineglessner.net www.facebook.com/lorraine.glessner.3 www.instagram.com/lorraineglessner1

My work has always been about what is invisible or often missed by the world. My own space (house, yard, parks, studio), nature, and the “World Wood Web” are constant sources of inspiration. I watch the light change, pass over objects, and transform them into something else. I see magic in the juxtaposition of shapes and in composition. I move around objects to change and shift perspective. This noticing is my daily practice to inform what I see, and how I feel the world to be.

I do not need to travel afar to find magic (although I LOVE travel). Truth be told, when I travel I often do not photograph any diferently than when at home, looking for the walked over, the silent beauty, the alchemical magic, and the invisible pieces of a culture. You may not know where I was in some of my travel images; I like that timeless and ubiquitous quality.

Joy – Once you experience it, that sensation occurs over and over again. When I don’t feel it, I find myself actively looking for and noticing it: an incredibly simple complex moment.

A simplicity of form and shape found in the decaying aspects of nature continually intrigues and inspires and draws me in.

While tempted to draw, paint, and make marks around an object, I often sit back and just admire the form within the, what I refer to as, the Elvis-velvet-black field that I create when making a scanogram or photograph an object.

Textures, forms, and shapes build my compositions.

Dancers Dance, pigment print on Murakumo Kozo paper, cold wax, 24 x 24 in

I have always loved the notion of taking a found object and creating something else by placing it on a flatbed scanner. I feel as if I’m working with a large format view camera. The image is reversed and upside down. The challenge is to examine the object, position it on the scanner bed, and tweak (via prescans) until I feel it is correct. A majority of times, I do not alter the original composition; I simply remove the imperfections that the scanner makes, recognizing that objects can metaphorically hold their meaning and beauty.

My early imaging life focused on portraits, dancers, and theater. In the last two decades, my work shifted to found objects in nature. I view them as portrait subjects, captured movement, gestures of life, and examples of the beauty of aging, disintegration, transformation, decay, and what may become joyous marks.

It is akin to a conversation, where the work becomes the lived experience: the continuum – digital to analog to digital to analog and round and round.

There are the pieces that are printed, charcoal, paint, other lines, and marks added to the substrate. Then I photograph this piece and bring it into the digital world of layers, color, marks, and masks. I often extract the image further into patterns, outlines, and color fields that can be applied to the piece or used in another. These layers can be continually morphed, warped, or skewed into another form and blended with the original object via masks and layers.

When satisfied I print to a substrate. My go to surfaces are Awagami inkjet papers, primarily Murakumo Kozo or Bamboo or inkjet ready silk, linen, or cotton.

Depending on the purpose, installation, or destination for the image, I either add cold or hot wax to the surface and frequently add hand embroidery.

Finished pieces are then prepped for hanging by making pockets at the top and bottom of the piece with selected paper or fabric (often hot waxed to add texture and stability). Then rods are added to both ends for hanging.

Marking Matters in Time is a collaboratively written piece (myself and my friend, Dr. Timothy Engstrom) for a solo exhibition in 2017, which continues to drive my process.

Perhaps creating something is nothing but an act of profound remembrance.

R. M. RilkeIt is also an act of possibility. I come to see things through stories. A work asks how I remember, but also how I produce these recollections: what senses, what materials, what acts of gathering, cutting, lifting, and collecting that anchor memories or stage their decaying beauty into a transition for new ones.

The object or the memory, which came first? I embed memory in physical remnants of my life in the hope that I never forget, or might be allowed a selective and elemental remembering, or in the hope that if I do forget, but from an imagined future that isn’t yet made, for an imagined person who hasn’t yet noticed.

Found and represented objects symbolize our engagement with nature as I navigate living, loss, aging, and grief, and I imagine what can yet become of them. Like the elements of nature, beings and their oferings are vulnerable to invisibility, to the melancholy beauties of decay, which are here afrmed and ritualistically intoned.

What’s unseen are the flows of time; the walks that made their way to these things; the hands that grasped them; the curious intimacy of the iPhone that helped recollect them; the tonal and digital processing that made its way back to the hand made and vulnerable. Things in transition have a beauty in their decomposition. They aren’t done becoming something else.

Pigment print on

From the series Marking Matters in Time

Which ones do we keep and nurture and which ones do we discard?

Hmmmm… I know that I collect images just like I collect found objects. I create them when it feels right or because they are fragile and their life span is brief in the current state. Doing this allows me to “sit with” the objects and elements. Through the process of photographing or scanning, I realize that either they need to be worked on immediately, fit within an on-going project, or need to remain in a folder until I am ready to make them into something more.

Anthea Revealed Pigment print, cold wax 30 x 24 in

Sometimes I start with a sense of how I want an image to look. Other times, I play and discover, based on experiments, letting things linger, marinate to be used later. At other times I shop my folders and discover really cool stuf that I had made and stored! For me, discard occurs as a step within the bigger process of building the image. I play with the object to see what it can become and use it or not. I might add to the original and realize that impulse did not work, and then I discard that piece and repeat the process again and again.

In general, I think it depends on the space you are taking up, residing in, and recognizing that what may have worked in the past will regularly change.

BUT, I do believe in maintaining, practicing, and setting priorities as described below.

• A daily practice – Regardless of what is going on, I have some kind of daily ritual with making. It is very important for me. Keeps me aligned and helps me to remember that no matter what, I am a maker, artist, and explorer. I may not even be aware that I am doing it. It becomes second nature and almost requires no thought. Just happens, and then I say, “Oh yeah, now I remember.”

• Quieting the internal critic – It can be very hard to keep moving and not want to discard anything because of that internal dialogue.

• Creating an open mind and heart – This works in every way and keeps possibilities open.

• Allowing time to nurture the work, shift into what it is meant to be. At times, I find this frustrating, but a critical part of my process.

• Accepting that it is all information – Choose to use it or go through the same discomfort again.

Yes, dormancy is a necessary component that is difcult to allow the time to happen. Our culture does not encourage or support the “art of doing nothing” or even doing something diferent to change the energy flow. This is a skill set each person needs to develop to stay energized.

Sometimes busy work and play are required before anything of “true value” appears.

I know I am a maker. The process of making is significant for me. Making is a process and requires many aspects that allow me to be me.

Projects remain unfinished until they are ready to be completed, or not. Some projects are akin to “friends of the road.” They serve a wonderful purpose, and then just like that, they have moved on.

Over the years I have read (and experienced) a lot about the energy of ideas. Where do they come from, how do they ride the ether of the world? Why do (and historically have) similar things occur at the same time in diferent venues around the globe? My take away is that ideas float and move and travel until someone picks them up and acts on them. This allows ideas to morph into yet another realm to be picked up by the next person bringing them to life and worked out in their style.

Books, podcasts, Ted Talks. There are so many venues ofering advice (dogmas, rules, breathing techniques, how to be, etc.) and thoughts on being creative. The books listed here are some of my favorites that illustrate examples of discovering and maintaining creativity and energy for the muse.

• The Creative Act: A Way of Being by Rick Rubin

• The Creative Habit: Learn It and Use It for Life by Twyla Tharp

• Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear by Elizabeth Gilbert

• The War of Art: Break Through the Blocks and Win Your Inner Creative Battles by Steven Pressfield

• Art & Fear: Observations on the Perils (and Rewards) of Artmaking by David Bayles and Ted Orland

• The Art of Noticing by Rob Walker

Pigment print on Murakumo Kozo paper, cold wax, 36 x 21 in From the series Marking Matters in Time Also featured on the back cover

• Listen. By really paying attention, being present with an open mind and heart.

• Document what is being said and return their words in a written form. No interpretations, just their words. I have found this to be a powerful tool when people get into the flow of expressing themselves. They are almost always surprised at their own eloquence and expression.

• Recognize and speak to their subject matter or content. Help them recognize their own content by looking at what they create. Point to their content, which they might not even realize themselves but becomes clearer as they work and trust the process.

• Unearth and make visible the things alluded to, but are not immediately forthright. This works with the two items above –listen and document. Give them an opportunity to tweak, restate, make more work, and reflect again. Then go through the process until it is time to move on. This also provides an opportunity for the teacher to make suggestions, to engage in a meaningful dialogue, and hopefully assist the artist in culling the most important parts of their intentions, thoughts, and work.

• Sometimes it is important to say, “This is just not working, switch it up, or try a diferent approach. What you say and think is out of sync with the work I am seeing.”

• Suggest a diferent approach with media and style, or suggest taking a break and do nothing for a while.

• Discuss what the artist is reading, watching, and listening to.

• Support is such a simple word, but it is often difcult to find true support. Depending on the artist, the teacher may simply sit back and hear what is said and view what is made. Other times, it becomes necessary to ask questions and pull out the rationale, intention, motivation for the work. Often, a round of questions can yield a context for the work.

• Encourage and change, not only in their work, but also push through the blocks. Encourage them to learn from the world and diferent teachers or mentors. The needs of an artist evolve, which may suggest a change in teacher or mentor at that time. This can create another way to look at what is known, or hearing the same thing in a diferent set of words can be impactful.

Here is a personal example to share. I do boxing classes. I have taken classes at the same gym from three diferent teachers. I learn so much, as well as diferent techniques from each one. All are good, but the voice and individual emphasis is diferent. A huge impact can happen to one’s performance and subsequent results from hearing the same information slightly diferently.

• Find a way to help students discover their own fascination, how to render it, and how to create the work.

• Whether you are an educator, teacher, instructor, or student, it all requires an open mind and heart. Perhaps creativity cannot be taught; however, resources and tools can be ofered to build a reserve of ideas and concepts, a repertoire of techniques, and a platform to play safely in without judgment.

My goal is to build an image in hopes of it becoming “the world of this thing I noticed.” The digital to analog to digital to analog to digital continuum begins.

I am and have been a huge believer in using technology to help experiment, tweak, and express my work. I use technology to grow and expand concepts, artwork, and general processes.

Digital photographic processes have provided so many options and desires possible for artists like me. Each upgrade, advancement with input and output choices happily expands my repertoire. I consider the digital to analog continuum to test ideas and use digital tools a collaborative process.

The image may begin as an iPhone shot, a DSLR shot, or (as in the example below) a scanogram (using a flatbed scanner as camera). Frequently, I combine all of the above in the process and then add more analog and digital marks.

The following example started as a scanogram.

Then I edit the image in Adobe Camera Raw© to process, followed by opening the file in Adobe Photoshop©.

Early in the process, I make a working print on paper that I find interesting. For me, seeing the image printed to a substrate, begins to bring it to life. Then I can decide how I want to proceed and what I want to play with.

I simply tape the working print to a board, photograph the print, and then play.

For this piece, I used colored charcoal to mark all over the print. This marked and drawn print is photographed again. I decided it was too much, then wiped and rubbed the marks on the print, and for the third time, I photographed the print.

The cycle of marking, drawing, altering, photographing may continue a few times until I feel something is working as a base.

When ready to continue playing digitally, I follow these steps.

• I export the image from Photos at full size;

• Return it to Adobe Camera Raw© to process the image;

• Then I open it in Adobe Photoshop©;

• I make multiple layers to create background efects, color, marks, edge efects, texture, etc.;

• Then I make a pigment-based (inkjet) print of this new digital file, on which I mark and draw with paint;

• With my phone I photograph and reopen the image in Adobe Camera Raw© and Adobe Photoshop© to experiment with additional mark making, color, and texture;

• Sometimes I take one of the layers I made in Adobe Photoshop© and print that image onto a film transfer, which I transfer on to a waxed piece.

Sound confusing? Everything feels like that until you actually go through the process several times, and the process becomes part of your practice.

This kind of process feels like being in a conversation. The work can be an answer to the process, the collaboration between concept, analog, and digital and then a lived experience.

Adobe Photoshop© allows me to easily make selections, change a specific area’s color or tone, and move image elements and marks around the image to make compositional decisions.

The images below show how I changed the background as well as the indigo pods themselves by adding layers, selections, and changing blending modes of each layer. Curious results, but I know how I want the image to feel and read.

The next group of images show the addition of individual layers, making shapes, and altering those shapes by moving them around the image until I feel the image works.

Each component is on a separate layer, which allows me to make the smallest of movements or use tools like warp and skew to change the shapes, as well as the transparency of each mark.

I change and shift colors and tones to see what I think works best, as well as the substrate I plan to work on, or if I make a film transfer to a favorite surface or substrate or make it part of a larger image.

A file may look like the illustration below. There may be individual layers or notes attached to the file reminding me of what I want to do to the next iteration or to the final print — perhaps sew, embroider, or add some hand coloring.

Another test print is made to see if the composition and colors work for the selected substrate. In this case, I made a print on Awagami inkjet Bamboo paper, inkjet prepped linen and cotton percale. Based on the tests, I altered the image and labeled and grouped the layers for the final prints.

This process is so much fun! Once you get over the feeling of awkwardness, as one usually does with anything new, the possibilities and streams of energy are amazing. Experimenting with the digital to analog to digital to analog continuum opens the door to finding magic and to the invisible pieces of culture in your world.

Artist, explorer, maker and educator, Patricia Russotti’s current work is focused on entropy, negentropy, nature, and the small things she stumbles upon within the existing world. She is passionate about the examinations of nature and the alchemical magic that occurs within natural phenomena and the creative process.

Patti’s work has been consistently showcased in solo, group, and juried exhibitions, as well as in international private and corporate collections. Her practice reflects a breadth and depth of experience and skill in image-making (including analog, digital, alternative, and historic processes) and workflow, as well as digital output to a variety of substrates, such as fabric and washi.

She has been training and presenting on Adobe Photoshop© and Adobe Lightroom© since the first versions of the applications and employs these tools in the creation of her work.

Bevier Gallery, Rochester, NY

Encaustic monoprint, pigment print with encaustic monoprint and thread, three totems — gourds, found objects, and film transfers on gourds

Currently, she is creating and ofering workshops online and in-person to provide emerging and established artists with acquiring digital tools to expand their art practice and to clarify their intent. Patti believes in creating a continuum of working digital to analog to digital to analog and the impact that has on one’s practice.

Her evolving methodology is continually featured at national and international imaging and education conferences, and she has been a regular presenter since the 1980s.

She is the co-author of Digital Photography Best Practices and Workflow Handbook; A Guide to Staying Ahead of the Workflow Curve © 2010, published by Focal Press.

Patti holds M.S. and Ed.S. degrees from Indiana University and spent four decades as a professor at Rochester Institute of Technology – most recently in the School of Photographic Arts and Sciences.

You can view Patti’s work at www.pattirussotti.com www.instagram.com/patti.russotti patti-invisiblematter.blogspot.com

You can view Marking Matters in Time at www.pattirussotti.com/marking-matters-in-time

When a seed is planted it may thrive or it may sit dormant in the ground until something in its environment changes. New life sprouts upward under the watchful eye of the sun, and roots embed themselves deep into the earth to provide food and stability. Depending on the type, one seed may promote growth for multiple plants.

The germination of creativity works much the same way. When inspiration strikes, my mind and heart are altered from their original spheres. I may leap of my chair and run to my studio. Or more likely, I will sit with a new idea for days, weeks, or months. I create lists and draw quick sketches.

Like the seed that rests below the ground waiting for nourishment or warmth, I take my time to fully explore and sift out the true essence of what I’ve experienced, heard, or seen. Sometimes a concept requires research. Sometimes I have a strong opinion that needs voicing, or I will lean into an emotional response. I can also recount times that I’ve ruminated so long that I start dreaming about the subject matter. Once I’ve thought it through and searched my heart, I begin to realize visual cues and carefully consider content and color.

Finally, I begin transcribing it into something visual.

A Bit of Cheer, Encaustic, metallic pigments diptych on cradled board, 12 x 12 x 1 in

It is a rare moment that I first begin painting on my intended substrate. My encaustic students are aware of this because we always loosen up with small boards before getting to the big stuf. I encourage them to “just play,” like I do.

It’s important to allow yourself time to explore color, content, lines, textures, and (perhaps) some new techniques.

Carving, scraping, and mark making are analogies for my emotional expression. I work on 3 to 6 boards at once to let the ideas flow out of me, into my brush and onto the surface.

Boundless, Encaustic on board, 13 x 3 x .5 in

Boundless is an example of expressive lines. This was a playful warm-up painting.

There are no rules while cultivating inspired ideas - rules stifle growth. I let my hands grab what they like and push my medium to do as it’s told.

My encaustic painting students will attest that I will never tell them what to paint; I help them navigate their painting journey. One result that I love during the process of play is how multiple interpretations can result from one spark of the imagination. This is the best time to let them all speak in order to decipher which ideas are the best. My students often surprise themselves when they discover that their intended painting is not their best painting, but the precursor for the more subliminal grand plan. It’s pure magic!

My life, in its small and big moments, delivers plenty of sustenance for my artwork. Personal experiences keep me quite busy in my studio, but I double up my eforts by listening to National Public Radio shows like: “Snap Judgment,” “Science Friday” and “The Moth Radio Hour.”

For example, in 2016, I heard Director Lulu Wang tell her story about a Chinese tradition called Chongxi on “This American Life.” The literal meaning is to “wash away misfortune with joy.” Unable to stop thinking about it, I did my research and got busy painting. In the course of several years, I created a series of artwork based on her story and others like it.

Sometimes germination can inspire ideas that promote creative growth in other ways. When my sister was diagnosed with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS or Lou Gherig’s Disease) in 2020, many of my paintings translated into visions of hope, life’s unpredictability, and living in the moment.

My desire to do more led me to start a Little Art Gallery on my website that helps fund ALS research. In May 2022, my growth as an artist branched out in new ways, when I curated the first annual exhibition, Hope Lives: Art for ALS. Now planning my second exhibition in May of this year, it is clear to me how each idea and action grew in an authentic and natural way until it bloomed.

Developing new content for my artwork means looking and listening closely. I remain open to new ideas and immerse myself in how an experience or situation feels. I latch onto what is important to me and nurture these ideas into visible representations to share as an artist, educator, and curator. My way is not the only way. How do you explore what inspires you? I hope that these seedling ideas help to nurture your creative expression.

Melissa Stephens is an encaustic painter, photographer, and printmaker, who has spent 15 years educating children and adults in the arts. She received a B.A. in Art from Cornell College, Mt. Vernon, IA, and continues her arts education through specialized instruction. Her encaustic paintings explore themes of healing and hope. She is an encaustic painting instructor and advocate for the arts in Walnut Creek, CA. Her artwork shows in galleries throughout California and collections across the United States. In 2022, she co-founded the NorCAL Wax Chapter and curated an annual exhibition Hope Lives: Art for ALS.

You can view Melissa’s work at www.mascreations.com

www.instagram.com/melissa_stephens1016

www.facebook.com/melissastephens1016

www.youtube.com/@TheEncausticEdge

https://www.bluelinearts.org/hot-and-cold

The 2nd Annual Hope Lives: Art for ALS

San Francisco Women Artists Gallery May 2 - 26, 2023

www.hopelivesartforals.com

Next to Near

Encaustic mixed media with Mexican bark paper on cradled board 36 x 24 x 2 in

As artists, we must learn to recognize our natural rhythms and nurture our wide range of creative energies if we are to produce our best work and avoid burnout.

This means tuning into our unique creative seasons. While our inner seasons don’t always align with the timing of the calendar, creative seasons do align with the characteristics of winter, spring, summer, and autumn.

If our creative inspiration is truly to flourish, then it requires the following:

Space to enter - WINTER

Time to germinate - SPRING

Energy to create - SUMMER

Reward to thrive - AUTUMN

Alicia working in her studio

Alicia working in her studio

Creative Winter is a time of rest and creating space for new ideas to flow. This is the time to reflect and plan. During Creative Winter you may feel called away from your art practice by other interests or feel a lack of motivation and low energy. Many artists struggle during this season because they feel that this may be a permanent state or that they should be producing more artwork. Have faith that your Creative Spring will follow and give yourself permission to rest and reset during this period of dormancy.

Creative Spring

Creative Spring is a time for germination. A time to nurture the seeds of inspiration.

During Creative Spring new ideas will form and inspiration will come easily for you. This is the time to set goals, dream big, and collect the abundance of ideas as they begin to flow. Be sure to capture your inspirations in a notebook or record them.

During Creative Spring you may also find yourself experimenting more in the studio, trying out new techniques, or having the desire to take a class.

Encaustic, shellac, ink on panel 48 x 24 in

Creative Summer is the time we execute our ideas. You will have more energy and are naturally more productive during this season. Artists often create some of their best work during this time. You may see an increase in your creative output and find it easier to assimilate your flow state. It is not uncommon to have multiple creative projects going at once during your Creative Summer. Lean into this season and enjoy your process. Just be careful not to take on too much during this phase.

Charm School, Encaustic with mixed media, 10 x 10 in

Creative Autumn

Creative Autumn is the time to harvest the fruits of your creative labors, share your work with your audience, and capitalize on your creative eforts. You may find yourself working on promotions for an art event and sharing more of your artwork on social media during your Creative Autumn. We feel more naturally inclined to want to focus on the business aspects of our studio practice during this season.

Some creative seasons are short, lasting only a few days or weeks, while others can last a year or more. Every artist is unique, and the way you move through your creative seasons will be singular to you. You may enjoy long stretches of productivity followed by a short season of dormancy or vice versa.

For most artists, each season comes bearing gifts. Understanding your creative flow and the seasons that dictate the rhythm of your studio practice can help you capitalize on what each state inherently contributes to your workflow and output.

For instance, resting during your winter season will keep you from getting run down or losing interest in your work and will also help you avoid burning out. It takes longer to recover from burnout than to start up again after a much-needed break. New concepts need time to germinate, and when you give your brain some time to relax, it can start to make new associations and connections that often result in fresh perspectives. This is what your Creative Winter is all about.

Another example is recognizing the onset of your Creative Spring. This puts you in a position to prepare yourself to capture the flood of new ideas that will inevitably start to pour in. Documenting your new concepts will come in handy when you later enter into your productive summer season and provide you with a library of inspired ideas as a source of reference.

In anticipation of your summer season of high energy and increased productivity, you may want to restock your studio supplies ahead of time to ensure your creative work goes uninterrupted when things begin to ramp up for you.

Knowing that your Creative Autumn season will be a time to show your work and take a victory lap, you may want to order new business cards in advance, update your website, or tidy up your social media profile beforehand. Don’t forget... it’s okay to toot your own horn and celebrate all of your hard work.

An important part of every artist’s journey is learning to identify, navigate, and capitalize on our creative rhythms. When we allow ourselves to fully embrace each season, we can move through our creative practice with more ease, focus, productivity, and self-compassion.

Alicia Tormey is an internationally-recognized artist known for her unrestrained botanical paintings, ethereal abstract landscapes, and her pioneering encaustic techniques.

Alicia’s work has adorned the cover of Professional Artist Magazine and has been featured in the Boston Globe, Encaustic Arts Magazine, and many others. Her paintings have been displayed in public and private collections around the world, including two U.S. embassies, and her artworks have been the subject of more than 20 solo exhibitions throughout her career.

In addition to painting, Alicia also teaches and mentors artists across the globe through her online courses, live encaustic workshops, and coaching programs.

Alicia’s art is heavily influenced by the Pacific Northwest region of the United States, where she has lived since 1981. She currently maintains a studio in the mountains near Sun Valley, Idaho.

You can view Alicia’s work at www.aliciatormey.com

www.instagram.com/alicia.tormey

www.facebook.com/alicia.tormey

www.youtube.com/c/AliciaTormey/featured

www.pinterest.com/aliciatormey

“Here's the thing about wildflowers they take root wherever they are grow strong through the wind, rain, pain, sunshine, blue skies and starless nights they dance, even when it seems there is nothing worth dancing for they bloom with or without you.”

The IEA Annual Juried Exhibition that opens on June 11 at the San Antonio Art League & Museum is a fascinating fusion of past and present. The theme, Wax and Wildflowers, is a nod to the Davis Wildflower Competition presented by the very same organization in 1927. According to art historian William Reaves, the Davis Wildflower Competition at the San Antonio Art League literally blossomed into the state’s first true art extravaganza, presenting sensational art “happenings” that served to synergize nascent and far-flung arts communities across the state and catapult Texas art into the national spotlight.

Edgar B. Davis, visionary and eccentric, was a rancher, wildcatter, and philanthropist, who organized the international call to artists for the exhibit. He loved wildflowers and believed that bluebonnets brought him luck when he drilled his first oil well in a bluebonnet field.

Interestingly, the First Prize winner of the 1927 wildflower competition was a British-born impressionist painter, Dawson Dawson-Watson, whose prize-winning work celebrated the lowly prickly pear cactus. Women were also among the prize winners. This wonderful painting, Wild Poppies, was done by Isabel Bronson Cartwright from Pennsylvania.

The IEA Jurors, William and Linda Reaves, compliment this IEA/ San Antonio Art League wildflower collaboration. Gallerist, historian, and author William Reaves literally wrote the book on this important 1927 event titled Texas Art and a Wildcatter's Dream: Edgar B. Davis and the San Antonio Art League.

The Davis Competition paintings were done in 1927 by artists who were tasked with representing the beauty of wildflowers in classic compositions on canvas. Almost a century later, artists who submitted to IEA’s Wax and Wildflowers at the San Antonio Art League & Museum in 2023 have been invited to widen the lens by representing the wildflower concept in unrestricted, untraditional ways with wax as the only common bond and to celebrate the enduring wildflowers in a new creative conversation.

Celtic ConVergence — Wax Across the Water is co-hosted by International Encaustic Artists (IEA), Mulranny Arts in Mulranny, Ireland, and IEA's European Encaustic Chapter.

October 12 - 17, 2023

Pre-Retreat Workshops: Wednesday and Thursday, October 11-12

Post-Retreat Workshops: Tuesday and Wednesday, October 17-18

Our first IEA ConVergence in the spring of 2022 on the coast of California was a remarkable event for those who attended. We experienced deep community, explored revolutionary ideas in our art form, and generally rejoiced in being together in person at the end of the land and the edge of the water.

Appropriately enough, our theme for this issue of Wax Fusion is germination, and in California there were ideas germinating about gathering again, but this time on another coast – the wild, remote coast of Western Ireland. Apparently, the stars aligned, because we are indeed converging together again in October at the dramatic western edge of Ireland on Clew Bay, the end boundary of Europe. The convergent parallels are amazing.

As you think about whether to join us for our Celtic Convergence, remember that “convergence” is about coming to conclusions, making decisive decisions, choosing between tradeofs, and prioritizing what is essential versus what is “nice to have.” You are purposefully narrowing the range of possibilities you are considering, so that you can converge on a final outcome, one that is deeply satisfying.

This is sheep country. Below the mountain lies the salt marsh. Here, the sheep patiently wait for the waters to recede so they can continue to graze on the salty grass. The rhythm of life is dominated by these tides, flowing over the white sand beaches and then leaving in hasty withdrawal to the vast Atlantic Ocean. At the Convergence, there will also be time for exploring with our fabulous Tour Guide Colum, who will regale you with stories (some of them, true!) about the area, or you may wish to avail yourself of the open-studio time at one of our gorgeous encaustic studios.

The retreat and exhibition will be held at Mulranny Arts Campus, the workshops will be at the EOM campus and the Mulranny Arts Campus, and all retreat accommodations will be close by.

Transportation will be provided for meals out and our sightseeing days.

The art we make and the conversations we share will be forever inspired by this place and these rhythms, and you will come back charged with inspiration and changed by your experience.

Pre-retreat workshop-only attendees are invited to join the retreat attendees at the Welcome Dinner. Post-retreat workshoponly attendees are invited to attend a fun social event on the last night of the retreat. And everyone is welcome to attend the IEA Juried Exhibition and artists’ reception located at Mulranny Arts.

To learn about Celtic ConVergence or register for the retreat and/ or one of multiple workshops being ofered pre-retreat and postretreat, go to www.international-encaustic-artists.org/2023Converence-WaxAcrosstheWater.

We take great joy in shining a spotlight on IEA members’ work through our active and vibrant presence on Instagram, Facebook, and Pinterest.

Our goals are to:

• highlight and celebrate the work and accomplishments of IEA members;

• announce new opportunities;

• engage and educate people about encaustic arts; and

• foster a sense of community among encaustic artists.

Have you shared your current social media handles with us? We suggest that you log into your IEA profile to check that your social media information is up-to-date. We also ask members to grant us permission to share their work by signing a terms of usage permission form.

Through our @iea_encaustic account, we regularly share work of artists who have granted us their permission. With more than 3,500 followers, our posts receive lots of attention and interaction.

We also invite members to tag us in their posts. Use these two hashtags whenever you post:

#iea_encaustic

#internationalencausticartists

You can also follow these hashtags to see lots of inspirational posts by other artists working in wax.

As an all-volunteer organization, it takes a team to create and sustain our social media presence.

We feel privileged to have a truly international social media team coordinated by Social Media Director, Regina Quinn, with members from across Canada, Europe, and the United States, including:

Emma Ashby

Peter Blackmore

Joe Celli

Cindy Clark

Alison Fullerton

Sally Hootnick

JuliAnne Jonker

Deni Karpowich

Birgit Kentrat

Gina Louthian-Stanley

Ursi Lysser

Megan MacDonald

Judy Pickett

Caryl St. Ama

Melissa Stephens

Trudie Wolking

IEA supports the growth and advancement of artists at all stages of their careers and provides opportunities and resources within a global community. This past year, IEA provided 12 conference scholarships, 1 artist residency, 4 Emerging Artist grants, 4 Project grants, 5 Art Heals grants, and exhibition opportunities. Artists at all levels are welcome to join www.international-encaustic-artists.org/JoinIEA.

The history of the world begins with a seed. The seed is the kernel of what you are, but it is also the promise of what you can become.

Kate Elliott