32 minute read

CBS News

‘Prolonged, dangerous and historic’ heat wave bakes much of ‘Prolonged, dangerous and historic’ heat wave bakes much of western Canada, including western Canada, including two northern Canadian territories, two northern Canadian territories, Yukon and the Northwest Territories. Yukon and the Northwest Territories.

The Canadian Press

Advertisement

High temperatures could extend into into next week for many areas, Environment Canada Canada warns

Environment Canada is warning the extreme extreme heat wave that has settled over much of Western Canada won’t heat wave that has settled over much of Western Canada won’t lift for days, although parts of British Columbia and Yukon could see some relief sooner. lift for days, although parts of British Columbia and Yukon could see some relief sooner. Heat warnings remain posted across B.C. and Alberta, large parts of Saskatchewan, Northwest Terri Heat warnings remain posted across B.C. and Alberta, large parts of Saskatchewan, Northwest Territories and a section of Yukon as the weather office forecasts temperatures reaching 40 C in some areas. and a section of Yukon as the weather office forecasts temperatures reaching 40 C in some areas. Sixty heat records fell on Sunday in B.C B.C., including in the Village of Lytton, where temperatures reached ., including in the Village of Lytton, where temperatures reached 46.6 C — breaking the all-time Canadian high of 45 C time Canadian high of 45 C set in Saskatchewan in 1937. Environment Canada warns the “prolonged, dangerous Environment Canada warns the “prolonged, dangerous and historic heat wave” could ease as early as ve” could ease as early as Tuesday on B.C.’s South Coast and in Yukon, but won’t relent until mid Tuesday on B.C.’s South Coast and in Yukon, but won’t relent until mid-week, or early next week, week, or early next week, elsewhere.

Climate change at play

CBC meteorologist Johanna Wagstaffe CBC meteorologist Johanna Wagstaffe says that record is expected to be shattered again Monday, possibly says that record is expected to be shattered again Monday, possibly in Abbotsford, B.C. “This is absolutely connected to climate change,” she said. “First of all our baseline has shifted. Our new “This is absolutely connected to climate change,” she said. “First of all our baseline has shifted. Our new normals are already one to three degrees warmer across the normals are already one to three degrees warmer across the province, even up to four or five degrees warmer province, even up to four or five degrees warmer through the north.” Wagstaffe says that moving forward, British Columbia is forecast to experience more extreme heat earlier on Wagstaffe says that moving forward, British Columbia is forecast to experience more extreme heat earlier on

Wagstaffe says that moving forward, British Columbia is forecast to experience more extreme heat earlier on in the summer as well as more days with temperatures above 30 degrees. “While you can’t take one event and say it’s directly connected to climate change, this is consistent with what climate change will continue to do to our province.” Alberta is set to be the country’s hot spot Tuesday with temperatures in the high 30s and more all-time provincial records expected to be broken before temperatures come down Friday, says Wagstaffe.

Drink water, avoid sun

Those living in the areas affected by the heat wave are being advised to take certain precautions to avoid heatrelated illnesses, which can sometimes be life-threatening.

Here are some tips to stay safe in extreme heat:

-Avoid the direct sun as much as possible. -Plan to spend time in a cool, or air-conditioned place, like a library, a mall, or even a movie theatre if you can. -Drink a lot of water, even before you feel thirsty. -Avoid strenuous activity and exercise. -Avoid sunburn and wear sunscreen with SPF 30 or higher on exposed skin and an SPF 30 lip balm. -Wear lightweight, light-coloured, loose-fitting clothing and a wide-brimmed hat, or use an umbrella for shade.

In B.C., municipalities and districts have opened cooling centres at public libraries and community centres for those who don’t have air conditioning. Forecasters say humid conditions could make it feel close to 50 C in B.C.’s Fraser Valley, and area raspberry growers say any cooling by Tuesday may come too late for their heat-ravaged crops, with one farm posting on social media that its season is likely over before a single berry has been picked. Flood watches are in place across B.C. for the extreme snow melt that is happening on mountain tops due to the high temperatures.

School districts across the province have cancelled classes for the day rather than hold them in classrooms without air conditioning, and the Fraser Health Authority says it is temporarily juggling appointments and relocating several COVID-19 vaccination clinics to reduce the chance of heat-related illnesses. “All individuals with appointments at affected immunization clinics will be notified to proceed to alternate clinics and all appointments will be honoured,” the health authority said in a statement released Saturday. More information was expected to be released by the end of the day on Monday regarding any extension of the temporary measures, Fraser Health said.

Record-breaking electricity demand

BC Hydro set another new record for the highest summer peak hourly demand — the hour customers use the most electricity — on Sunday night. Electricity use reached 8,106 megawatts — more than 100 megawatts higher than the previous summer record set on Saturday. According to the corporation, Monday’s peak hourly demand is expected to again break the record, possibly exceeding 8,300 megawatts. BC Hydro says localized outages have occurred over the past couple of days which is especially concerning during extreme heat.

Paramedics overwhelmed

The heat wave has created an incredibly challenging situation for the province’s paramedics. Troy Clifford, provincial president of the Ambulance Paramedics of B.C., told CBC’s The Early Edition on Monday that dispatchers received a record-level of calls this weekend. “At times yesterday there was over 100, peaking at 130, calls holding between emergency and nonemergency calls,” said Clifford.

Clifford said in some emergency situations, people were waiting up to two hours for an ambulance. “Paramedics and dispatchers are absolutely, I don’t know what to say, at wit’s end,” said Clifford. He estimated 25 per cent of calls over the weekend were directly due to the heat and said people need to know their limitations, especially when engaging in recreational activities like hiking where rescue missions are complex and a strain on already limited resources.

-With files from CBC News, The Early Edition

Finland's Arctic Lapland area swelters in record heatwave.

The Associated Press

HELSINKI -- Finland’s northernmost Arctic Lapland region has recorded its hottest temperature for more than a century at 33.6 degrees Celsius (92.5 Fahrenheit), during a heatwave that's been afflicting the entire Nordic country for weeks.

The temperature was measured Monday at Finland's northernmost Utsjoki-Kevo weather station near the border with Norway by the Finnish Meteorological Institute.

The institute said there was only one higher historical measurement reported in Lapland — 34.7 C in the Inari Thule area, in July 1914.

The beginning of July has been exceptionally warm in Lapland, one of Europe's last remaining wildernesses known for its extremely cold winters that attracts domestic and international nature lovers in both summer and winter. The region, Finland's largest by surface, host records for the coldest temperatures in the nation of 5.5 million.

“It is exceptional in Lapland to record temperatures" of over 32 C, Jari Tuovinen, a meteorologist at the Finnish Meteorological Institute, told the Finnish public broadcaster YLE.

InterpNEWS

So hot in Rovaniemi (Finnish Lapland) that the reindeer head for the beaches.

He said the current heat wave in Lapland is a result of prevailing high pressure causing warm air in the area. In addition, "warm air has been brought in from Central Europe to the north through the Norwegian Sea,” Tuovinen told YLE.

Nordic neighbors Norway and Sweden have also recently recorded high temperatures in the north, where the Norwegian municipality of Saltdal recorded 34 C this week.

Finland's all-time high temperature of 37.2 C was measured in the eastern city of Joensuu in 2010, YLE reported.

InterpNEWS

The state of the climate in 2021

By Isabelle Gerretsen10th January 2021

BBC

The state of the climate in 2021 - BBC Future

After the turbulent year of 2020, BBC Future takes stock on the state of the climate at the beginning of 2021.

From unprecedented wildfires across the US to the extraordinary heat of Siberia, the impacts of climate change were felt in every corner of the world in 2020. We have come to a "moment of truth", United Nations Secretary General Antonio Guterres said in his State of the Planet speech in December. "Covid and climate have brought us to a threshold." BBC Future brings you our round-up of where we are on climate change at the start of 2021, according to five crucial measures of climate health.

1. CO2 levels

The amount of CO2 in the atmosphere reached record levels in 2020, hitting 417 parts per million in May. The last time CO2 levels exceeded 400 parts per million was around four million years ago, during the Pliocene era, when global temperatures were 2-4C warmer and sea levels were 10-25 metres (33-82 feet) higher than they are now. "We are seeing record levels every year," says Ralph Keeling, head of the CO2 programme at the Scripps

InterpNEWS

"We are seeing record levels every year," says Ralph Keeling, head of the CO2 programme at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, which has been tracking CO2 concentrations from the Mauna Loa observatory in Hawaii since 1958. "We saw record levels again this year despite Covid."

The effect of lockdowns on concentrations of CO2 in the atmosphere was so small that it registers as a "blip", hardly distinguishable from the year-to-year fluctuations of the carbon cycle, according to the World Meteorological Organization, and has had a negligible impact on the overall curve of rising CO2 levels.

"We have put 100ppm of CO2 in the atmosphere in the last 60 years," says Martin Siegert, co-director of the Grantham Institute for climate change and the environment at Imperial College London. That is 100 times faster than previous natural increases, such as those that occurred towards the end of the last ice age more than 10,000 years ago. "If we keep tracking the worst-case scenario, by the end of this century levels of CO2 will be 800ppm. We haven't had that for 55 million years. There was no ice on the planet then and it was 12C warmer," says Siegert.

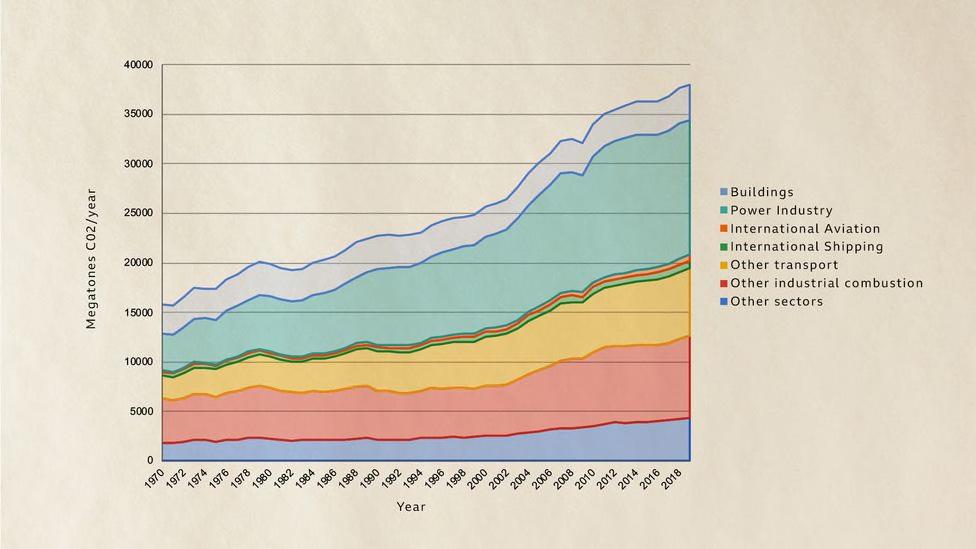

CO2 emissions have risen rapidly since the 1970s (Credit: European Commission JRC EDGAR/Crippa et al. 2020/BBC)

2. Record heat

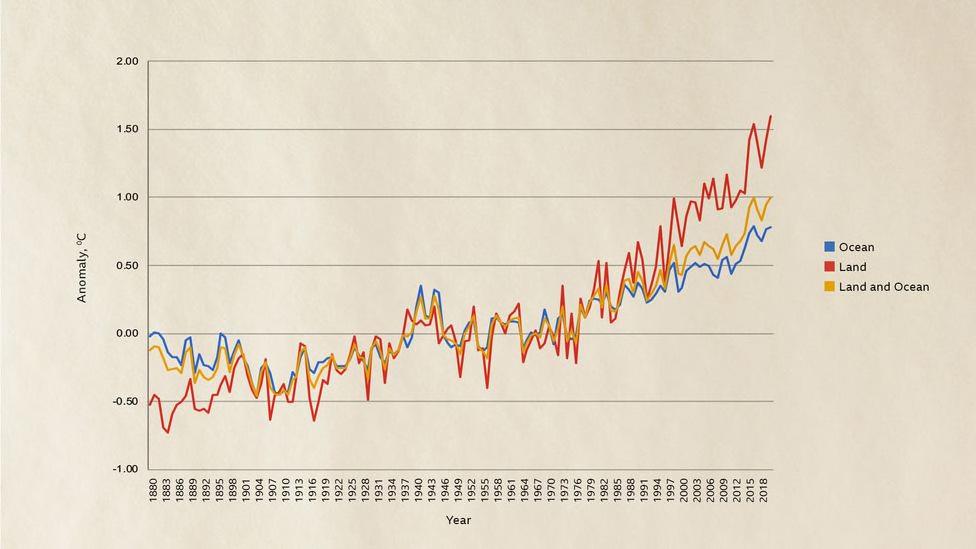

The past decade was the hottest on record. The year 2020 was more than 1.2C hotter than the average year in the 19th Century. In Europe it was the hottest year ever, while globally 2020 tied with 2016 as the warmest.

Record temperatures, including 2016, usually coincide with an El Niño event (a large band of warm water that forms in the Pacific Ocean every few years), which results in large-scale warming of ocean surface temperatures. But 2020 was unusual because the world experienced a La Niña event (the reverse of El Niño, with a cooler band of water forming). In other words, without La Niña bringing global temperatures down, 2020 would have been even hotter.

The exceptionally warm temperatures triggered the largest wildfires ever recorded in the US states of California and Colorado, and the "black summer" of fires in eastern Australia. "The intensity of those fires and number of people being killed is truly significant," says Siegert.

High temperature anomalies have become greater and more frequent in recent years on land, air and sea (Credit: NOAA/BBC)

3. Arctic ice

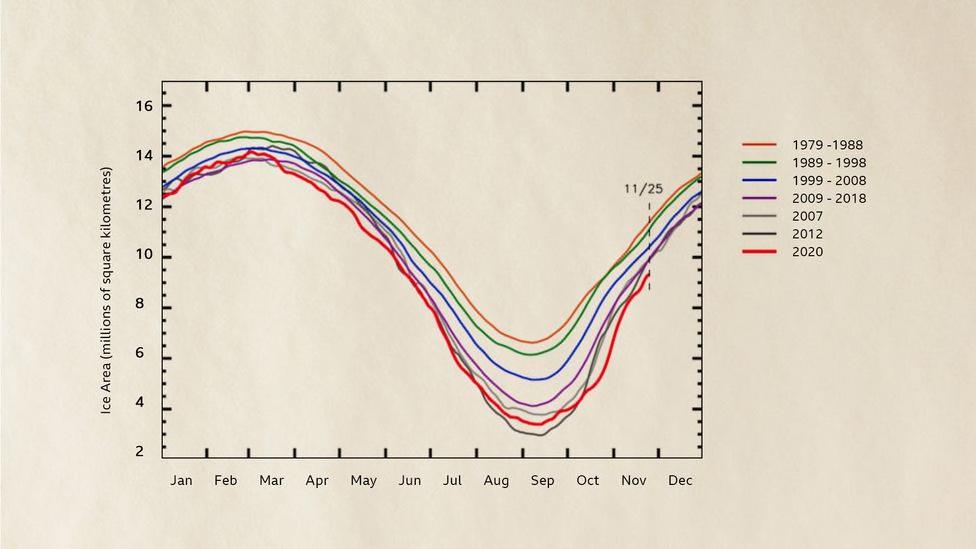

Nowhere is that increase in heat more keenly felt than in the Arctic. In June 2020, the temperature reached 38C in eastern Siberia, the hottest ever recorded within the Arctic Circle. The heatwave accelerated the melting of sea ice in the East Siberian and Laptev seas and delayed the usual Arctic freeze by almost two months.

"You definitely saw the impact of those warm temperatures," says Julienne Stroeve, a polar scientist from University College London. On the Eurasian side of the Arctic Circle, the ice did not freeze until the end of October, which is unusually late. The summer of 2020 saw sea ice area at its second lowest on record, and sea ice extent (a larger measure, which includes ocean areas where at least 15% ice appears) also at its second lowest.

As well as being a symptom of climate change, the loss of ice is also a driver of it. Bright white sea ice plays an important role in reflecting heat from the Sun back out into space, a bit like a reflective jacket. But the Arctic is heating twice as quickly as the rest of the world – and as less ice makes it through the warm summer months, we lose its reflective protection. In its place, large areas of open dark water absorb more heat, fueling global warming further.

Multi-year ice is also thicker and more reflective than the thin, dark seasonal ice that is increasingly taking its place. Between 1979-2018, the proportion of Arctic sea ice that is at least five years old declined from 30% to 2%, according to the IPCC. "White ice reflects a lot of energy from the Sun and helps slow the rate of global warming," says Michael Meredith, a polar researcher at the British Antarctic Survey. "We are accelerating global warming by reducing the amount of Arctic sea ice." The loss of ice is believed to be disrupting weather patterns around the world already. According to the Grantham Institute, it is possible – though not conclusively shown – that 2018 Arctic conditions provoked the "Beast from the East" winter storm in Europe in 2018 by altering the jet stream, a current of air high in the atmosphere. "Temperature difference between the equator and poles drives a lot of our large-scale weather systems, including the jet stream," says Stroeve. And because the Arctic is warming faster than lower latitudes, there is a weakening of the jet stream. "Everything is interconnected. If one part of the climate system changes, the rest of the system will respond," says Stroeve.

The Arctic sea ice has been diminishing rapidly since detailed records began in the 1970s, in a feedback cycle of warming and melting (Credit: NSIDC/BBC)

4. Permafrost

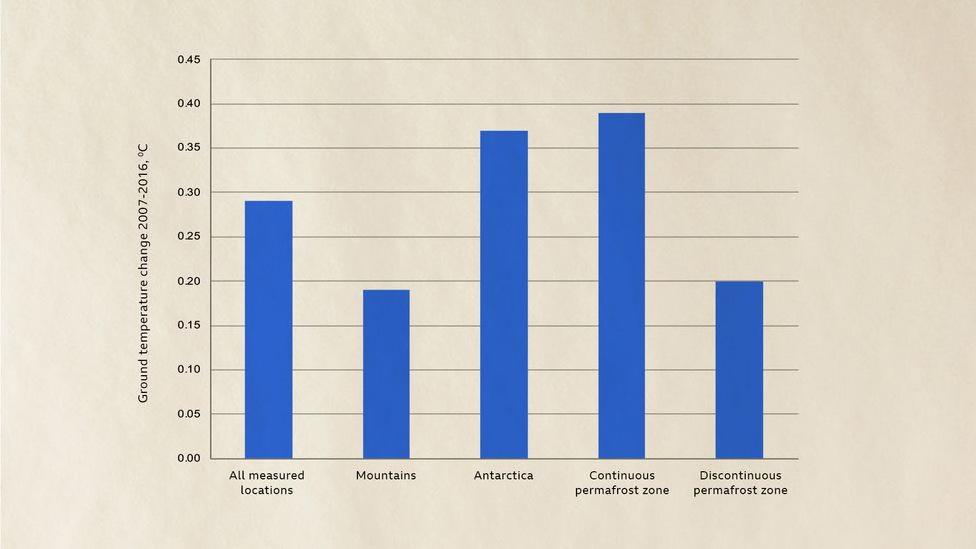

Across the northern hemisphere, permafrost – the ground that remains frozen year-round for two or more years – is warming rapidly. When air temperatures reached 38C (100F) in Siberia in the summer of 2020, land temperatures in several parts of the Arctic Circle hit a record 45C (113F), accelerating the thawing of permafrost in the region. Both continuous permafrost (long, uninterrupted stretches of permafrost) and discontinuous (a more fragmented kind) are in decline.

InterpNEWS

Permafrost is thawing – releasing CO2.

Permafrost contains a huge amount of greenhouse gases, including CO2 and methane, which are released into the atmosphere as it thaws. Soils in the permafrost region, which spans around 23 million square kilometres (8.9 million square miles) across Siberia, Greenland, Canada and the Arctic, hold twice as much carbon as the atmosphere does – almost 1,600 billion tonnes. Much of that carbon is stored in the form of methane, a potent greenhouse gas with a global warming impact 84 times higher than CO2. "Permafrost is doing us a big favour by keeping that carbon locked away from the atmosphere," says Meredith.

Thawing permafrost also damages existing infrastructure and destroys the livelihoods of the indigenous communities who rely on the frozen ground to move around and hunt. It is thought to have contributed to the collapse of a huge fuel tank in the Russian Arctic in May, which leaked 20,000 tonnes of diesel into a river.

As ground temperatures rise even fractionally, permafrost around the world begins to thaw and release greenhouse gases (Credit: Biskaborn et al. 2019/Nature Communications/BBC)

InterpNEWS

5. Forests

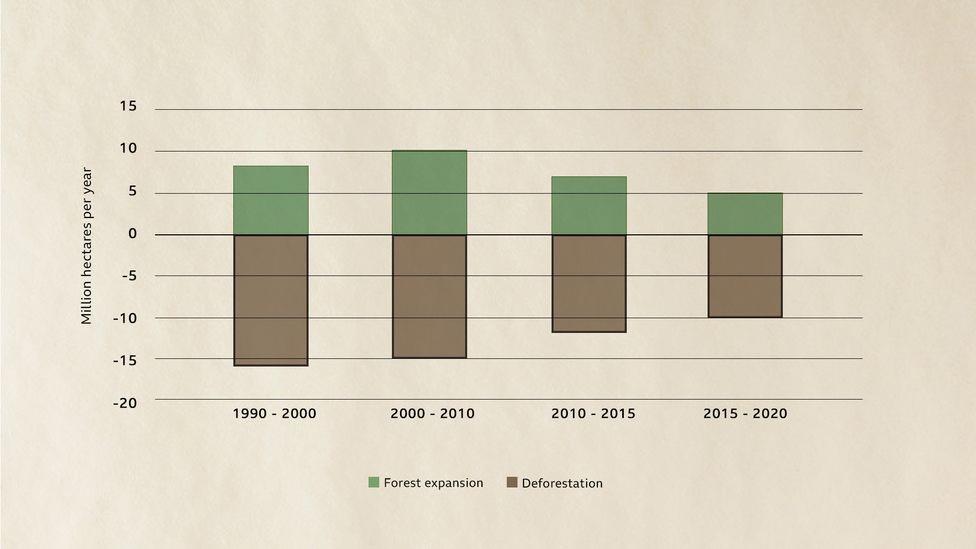

Since 1990 the world has lost 178 million hectares of forest (690,000 square miles) – an area the size of Libya. Over the past three decades, the rate of deforestation has slowed but experts say it isn't fast enough, given the vital role forests play in curbing global warming. In 2015-20 the annual deforestation rate was 10 million hectares (39,000 square miles, or about the size of Iceland), compared to 12 million hectares (46,000 square miles) in the previous five years. "Globally forest areas continue to decline," says Bonnie Waring, senior lecturer at the Grantham Institute, noting that there are big regional differences. "We are losing a lot of tropical forests in South America and Africa [and] regaining temperate forests through tree planting or natural regeneration in Europe and Asia." Brazil, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Indonesia are the countries losing forest cover most rapidly. In 2020, deforestation of the Amazon rainforest surged to a 12-year high.

An estimated 45% of all carbon on land is stored in trees and forest soil. "Soils globally contain more carbon than all plants and atmosphere put together," says Waring. When forests are cut down or burned, the soil is disturbed and carbon dioxide is released.

Read more on the solutions:

The revolutionary plan to save the Congo Basin The vast rewilding of the Kazakh steppe

The World Economic Forum launched a campaign this year to plant one trillion trees to absorb carbon. While planting trees might help cancel out the last 10 years of CO2 emissions, it cannot solve the climate crisis on its own, according to Waring. "Protecting existing forests is even more important than planting new ones. Every time an ecosystem is disturbed, you see carbon lost," she says. Allowing forests to regrow naturally and rewilding huge areas of land, a process known as natural regeneration, is the most cost-effective and productive way to capture CO2 and boost overall biodiversity, according to Waring.

World deforestation rates are slowing slowly overall, but in some of the world's most pristine forests it is still rapid (Credit: FAO/BBC)

As well as showing how much the climate has changed already, these five climate indicators also point the way to the solutions that can curb global warming to safer levels by the end of the century. As Guterres noted in his December State of the Planet speech, "Let's be clear: Human activities are at the root of our descent towards chaos. But that means human action can help solve it."

Published at the Yale School of the Environment

Melt pools atop sea ice in the Arctic Ocean in August 2009. P AB LO CLEMENTE -COLON / NAT IONAL I CE CE NTE R

Alien Waters: Neighboring Seas Are Flowing into a Warming Arctic Ocean

The “Atlantification” and “Pacification” of the Arctic has begun. As warmer waters stream into an increasingly ice-free Arctic Ocean, new species — from phytoplankton to whales — have the potential to upend this sensitive polar environment.

Cheryl Katz

Email Facebook

Above Scandinavia, on the Atlantic side of the Arctic Ocean, mackerel, cod, and other fish native to the European coast are migrating through increasingly ice-free waters, heading deeper into the Arctic Basin toward Siberia. Thousands of miles to the west, above Alaska, kittiwakes and other polar seabirds are being supplanted by southern birds following warm waters streaming north through the Bering Strait. And midway between, above Canada, sea ice-avoiding killer whales from the Atlantic are increasingly making themselves at home in a thawing Arctic.

As the Arctic heats up faster than any other region on the planet, once-distinct boundaries between the frigid polar ocean and its warmer, neighboring oceans are beginning to blur, opening the gates to southern waters bearing foreign species, from phytoplankton to whales. The “Atlantification” and “Pacification” of the Arctic Ocean are now rapidly advancing. A new paper by University of Washington oceanographer Rebecca Woodgate, for example, finds that the volume of Pacific Ocean water flowing north into the Arctic Ocean through the Bering Strait surged up to 70 percent over the past decade and now equals 50 times the annual flow of the Mississippi River. And over on the Atlantic flank of the Arctic, another recent report concludes that the Arctic Ocean’s cold layering system that blocks Atlantic inflows is breaking down, allowing a deluge of warmer, denser water to flood into the Arctic Basin.

Because the oceanographic conditions in the Atlantic and Pacific sectors of the Arctic are distinct, the physical mechanisms behind these widespread changes differ. But scientists say that the growing intrusions on both sides of the Arctic Ocean are driving heat, nutrients, and temperate species to new polar latitudes — with profound impacts on Arctic Ocean dynamics, marine food webs, and longstanding predator-prey relationships.

The Arctic Ocean, and its connections to the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. Y A L E E N V I R O N M E N T 3 6 0 / G O O G L E E A R T H

You’re really changing the system in terms of its capacity for production with the loss of sea ice, influx of nutrients, and also this ‘highway of prey,’” says Sue Moore, a biological oceanographer with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries Office of Science and Technology who studies marine ecosystems in the Pacific Arctic. “It’s a whole resetting of the table.”

Striking ecosystem effects are becoming evident across the high north. Some species appear to be gaining new habitat, while others seem to be rapidly losing ground.

InterpNEWS

On the Pacific side, humpback whales, a sub-Arctic species, have been observed in recent years as far north as Utqiaġvik (formerly called Barrow), off Alaska’s North Slope, where they had not been reported before. Moore thinks the whales are feasting on pulses of Pacific krill and other food streaming into the Arctic. Reduction in sea ice also allows whales to arrive earlier and stay later, giving them more time to feed and reproduce.

And this past winter, when sea ice in the Alaskan Arctic formed up to three months late and disappeared at the earliest date on record, “We had bowhead whales in the Chukchi Sea pretty much overwinter —we have never seen that before now,” says Moore, who is co-leader of the Synthesis of Arctic Research project, an international collaboration of polar experts looking at the effects of a changing Pacific Arctic on marine life.

Along the Arctic coast of western Canada, indigenous fishermen report salmon venturing unusually far north, says Carolina Behe, the indigenous knowledge science advisor for the Inuit Circumpolar Council-Alaska. And scientists conducting an Arctic ecosystem survey in 2008 were surprised to find walleye pollock and Pacific cod in the Beaufort Sea, said Elizabeth Logerwell, an ecologist with the NOAA Alaska Fisheries Science Center who co-led the survey. If these more southern species extend their range north, they could potentially supplant native Arctic fish. She cautioned, however, that the region lacks long-term historical fish survey data, making it hard to know for certain whether these were actually new arrivals or just being scientifically observed for the first time.

Scientists do say that the intrusion of Pacific waters is taking a toll on seabirds in the Alaskan Arctic. Traditional summer denizens in the Chukchi Sea — such as black-legged kittiwakes, thick-billed murres, and glaucous gulls — are now being supplanted by least and crested auklets, northern fulmars, and short-tailed shearwaters, which had not previously ventured so far north. The shift reflects a change in the birds’ prey, with new prey species being swept north through the Bering Strait. The change is causing an overall decline in seabird numbers, a recent paper concludes.

Signs of ecosystem shifts are even more dramatic on the Atlantic side of the Arctic, where Atlantic Ocean inflows overall are far warmer, larger, and saltier. Moore likens the incursion across the long boundary zone above Iceland and Scandinavia to a “firehose,” compared to a “garden hose” on the Pacific side, where incoming waters are constrained by the relatively narrow Bering Strait.

“When I came to Norway in 1974, the northern border for mackerel was western Norway,” says Paul Wassmann, a professor of marine ecology at the Arctic University of Norway in Tromsø and an expert on ice-edge ecosystems. “Now you can see [mackerel] in Svalbard fjords,” he says, referring to a group of Norwegian Arctic islands that lie nearly 600 miles above the mainland as far as 81 degrees North. Buoyed by Atlantic intrusions, warm water species are spreading northeast into the Arctic Ocean, and resident cold–adapted species, such as Arctic cod, are attempting to retreat further north. In the past half-decade, says Wassmann, “There has been (Atlantic) cod in fishable amounts north of Svalbard, which had not been observed before.”

In the Barents Sea, fish species typically found in the Atlantic Ocean, such as cod, beaked redfish, and long rough dab, have moved north and displaced Arctic fishes. N O A A C L I M A T E . G O V

One of the most striking trends is a rapid poleward spread of phytoplankton, the microalgae at the base of the marine food chain. A new study finds that Emiliania huxleyi, a phytoplankton native to more temperate, Atlantic seas, are blooming 5 degrees latitude, or roughly 350 miles, farther north in the European Arctic today than in 1989.

The northward spread of Atlantic phytoplankton could have a drastic effect on the Arctic marine ecosystem, says co-author Laurent Oziel, a polar oceanographer at Laval University in Quebec City. In the Arctic, the zooplankton that consume phytoplankton are specialized to store large reservoirs of fat to withstand harsh winter conditions. This makes them especially rich food sources for the fish that eat them, the seals that eat the fish, and on up to the top predators, such as polar bears. But the influx of southern phytoplankton is bringing in new types of zooplankton that are leaner and provide less nutrition for local species, Oziel says.

Southern zooplankton may not be able to survive the cold northern conditions. But Wassmann says that thinning and disappearing sea ice is allowing more light to penetrate the Arctic Ocean’s depths, stimulating algae growth that could allow fish and organisms to become established in places that previously lacked sufficient nutrients.

Atlantic influences are also being felt along the Canadian section of the Arctic Ocean. “In Hudson Bay we’ve seen a huge climatic shift in what we call subarctic species,” says Jennifer Provencher, a postdoctoral fellow in northern research at Acadia University in Nova Scotia. “We have documented that shifting occurring from cold-water species to the warmer water Atlantic species. In our case, it’s going from Arctic cod to much more capelin and sand lance.”

InterpNEWS

Another species appearing with increasing regularity in the Canadian Arctic is Orcinus Orca — the killer whale. These large, carnivorous members of the dolphin family used to be rare in the normally ice-covered waters, which orcas avoided because of their tall dorsal fins. But as sea ice retreats and their prey moves north, killer whales are now showing up more frequently in parts of the Canadian Arctic, where they pose a threat to narwhals, Beluga, and bowhead whales. As Nature Canada blogger Rebecca Kennedy puts it, “Killer whales are poised to become a major Arctic predator.”

Scientists are trying to better understand what’s driving the growing invasions from the Arctic Ocean’s neighboring waters. Historically, the northward flow through the Bering Strait is driven by a height difference — the Bering Sea is higher than the Chukchi Sea on the north side of the Bering Strait, causing the Pacific waters to run “downhill” into the Arctic, explains Robert Pickart, a physical oceanographer with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts who studies Pacific Arctic circulation. Prevailing northerly winds normally oppose the flow, especially in winter, when they retard Pacific water from crossing into the Arctic. Woodgate’s research finds that the increased Pacific flux is not due to a change in local winds, however. Instead, it appears linked to increased atmospheric pressure deep in the Arctic Basin, Pickart says.

“You have all this warm Pacific water coming into the Arctic and what is that going to mean?” says Pickart. “Not only is there more water going through, but there’s an increase in the amount of heat going through.” Adding more heat, he says, is “going to change the composition of the water and its likelihood to melt sea ice.”

To study the influx of warm Atlantic water into the Arctic Ocean, researchers recovered datacollecting buoys north of Severnaya Zemlya, a Russian archipelago, in 2015. I L O N A G O S Z C Z K O

In addition, waters from the Atlantic that have long entered the Arctic Ocean and circled down deep are being driven higher onto shallow sea shelves north of Alaska by increasingly intense storms. (The Arctic’s extensive sea ice cover used to tamp down storms.) “What we see at the Chukchi slope in the last few years are these pulses of Atlantic water, which is dreadfully warm, above zero degrees (Celsius), and salty,” says Phyllis Stabeno, a physical oceanographer at the NOAA Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory and a codirector of the Synthesis of Arctic Research.

On the other side of the Arctic Ocean, between Scandinavia and Russia, a strong layering system that normally prevents warm, Atlantic water from mixing upwards is weakening. Called the halocline, this thick band of cold Arctic water overlies deeper circulating Atlantic water and blocks its heat from reaching the surface of the Arctic Ocean.

InterpNEWS

But the halocline is losing its strength, according to Igor Polyakov, a University of Alaska Fairbanks oceanographer. He is lead author of a recent study finding that the Arctic Ocean is becoming more like the Atlantic, as reduced Arctic stratification lets more Atlantic water mix in and prevents sea ice from forming in the winter.

“The halocline has grown much weaker in recent years,” Polyakov says, “allowing the Atlantic water heat to penetrate upward and reach the bottom of sea ice.” The phenomenon, which began near Svalbard in the late 1990s, is now accelerating and spreading east into Arctic waters above Siberia.

Researchers point out that data from the remote Arctic Ocean are sparse and long-term observations are lacking, making it hard to pinpoint exact times and rates of change in polar marine ecosystems. The satellite record is only 39 years old and ship-based surveys have been infrequent, so scientists can’t always say for certain how much a population is increasing or extending its range.

“You need a time series in places where we don’t have a time series,” says Wassmann.

All signs are, however, that the Atlantification and Pacification of the Arctic Ocean will only intensify in the coming decades as the world continues to warm and the Arctic becomes increasingly ice-free. Arctic temperatures this past February soared to more than 45 degrees Fahrenheit above normal and hovered well above average all season. Winter sea ice was the second-lowest on record across the Arctic Ocean as a whole. And summer ice cover in the Arctic Ocean has declined by about 40 percent since satellite monitoring began. “It’s all linked,” says Moore. “Sea ice is such an important component of the system that once it is radically changed, you’re going to have other changes following that.”

Cheryl Katz is a Northern California-based freelance science writer covering climate change, earth sciences, natural resources, and energy. Her articles have appeared in National Geographic, Scientific American, Eos and Hakai Magazine, among other publications.

Death toll from record from record-breaking heat wave hits 116 in Oregon breaking heat wave hits 116 in Oregon

July 8, 2021,

PORTLAND, Ore. (AP) — Oregon’s death toll from last weekend’s record Oregon’s death toll from last weekend’s record-smashing Pacific Northwest heat wave has risen to 116. The state medical examiner Wednesday released an updated list o The state medical examiner Wednesday released an updated list of fatalities from the heat wave that added nine additional deaths. Of the 116 deaths recorded, the youngest victim was 37 and the oldest was 97. In Portland’s Multnomah Of the 116 deaths recorded, the youngest victim was 37 and the oldest was 97. In Portland’s Multnomah County, where most of the deaths occurred, officials said many victims had no air con County, where most of the deaths occurred, officials said many victims had no air con died alone. Gov. Kate Brown, a Democrat, on Tuesday directed agencies to study how Oregon can improve its Gov. Kate Brown, a Democrat, on Tuesday directed agencies to study how Oregon can improve its response to heat emergencies and enacted emergency rules to protect workers from extreme heat after a response to heat emergencies and enacted emergency rules to protect workers from extreme heat after a farm laborer collapsed and died June 26 at a nursery in rural St. Paul, Oregon. collapsed and died June 26 at a nursery in rural St. Paul, Oregon. Temperatures shattered previous all-time records during the three time records during the three-day heat wave that engulfed Oregon, Washington and British Columbia, Canada. Authorities say hundreds of deaths may ultim Washington and British Columbia, Canada. Authorities say hundreds of deaths may ultim attributed to the heat throughout the region. attributed to the heat throughout the region. The heat wave was caused by what meteorologists described as a dome of high pressure over the The heat wave was caused by what meteorologists described as a dome of high pressure over the Northwest and worsened by human-caused climate change, which is making such extreme weather events caused climate change, which is making such extreme weather events more likely and more intense. Seattle, Portland and many other cities broke all Seattle, Portland and many other cities broke all-time heat records, with temperatures in some places reaching above 115 degrees Fahrenheit (46 Celsius). reaching above 115 degrees Fahrenheit (46 Celsius). smashing Pacific Northwest f fatalities from the heat wave that added ditioners or fans and day heat wave that engulfed Oregon, ately be time heat records, with temperatures in some places

InterpNEWS Market Place

More Heritage Interpretation Climate Crisis Course Resources - three of our Climate Change resource publications.

Our Interpreting Climate Crisis Issues resources for our interpreting climate crisis newly updated course (Interpreting the climate crisis for your visitors).

Climate Change Interpretation Course. (heritageinterp.com) jvainterp@aol.com

The Heritage Interpretation Training Center offers 44 college level courses in heritage interpretation, from introductory courses for new interpretive staff, docents and volunteers, to advanced courses for seasoned interpretive professionals. Courses can be offered/presented on site at your facility or location, or through our e-LIVE on-line self-paced interpretive courses.

Some of our on-line courses are listed below. You can start the course at any time and complete the course at your own pace:

Introduction to Heritage Interpretation Course. 14 Units - 2 CEU credits. $150.00

http://www.heritageinterp.com/introduction_to_heritage_interpretation_cou rse.html

Planning/Designing Interpretive Panels e-LIVE Course - 10 Units awarding 1.5 CEU Credits $125.00

http://www.heritageinterp.com/interpretive_panels_course.html

Planning Interpretive Trails e-LIVE Course - 13 Units - 2.5 CEU Credits $200.00

http://www.heritageinterp.com/interpretive_trails_course.html

Interpretive Writing e-LIVE Course - 8 Units and 2 CEU Credits $200.00

http://www.heritageinterp.com/interpretive_writing_course.html

Training for Interpretive Trainers e-LIVE Course - 11 Units and 2 CEU Credits. $200.00

http://www.heritageinterp.com/training_for_interp_trainers.html

The Interpretive Exhibit Planners Tool Box e-LIVE course - 11 Units and 2 CEU Credits. $200.00

http://www.heritageinterp.com/interpretive_exhibits_course.html

Interpretive Master Planning - e-LIVE. 13 Units, 3 CEU Credits. $275.00

http://www.heritageinterp.com/interpretive_master_planning_course.html

A supervisors guide to Critiquing and Coaching Your Interpretive Staff, Eleven Units, 1.6 CEU Credits. $175.00

http://www.heritageinterp.com/critiquing_and_coaching_interpretive_staff.h tml

The Heritage Interpretation Training Center/John Veverka & Associates. jvainterp@aol.com – www.twitter.com/jvainterp - Skype: jvainterp

InterpNEWS

Interpretive Planning, Training and Design Consulting Experts in Climate Change/Global Warming Interpretation.

Post CV 19, JVA is pleased to offer a new and wide ranging package of interpretive planning and consultation services in the area of National and International Climate Change impacts, mitigations interpretation to site visitors and interpretive media/services planning. - Climate Crisis Interpretive Training Seminars/Courses for interpretive staff. - Climate crisis local/regional assessments for interpretation. - Climate crisis local and regional interpretive planning for communities. - Climate crisis individual mitigation activities (for interpretive programs/exhibits). - Interpretive panels and wayside exhibits. - Climate crisis traveling exhibits. - Climate related museum/nature center exhibits. - Climate crisis interpretive publications – web site content planning. - Zoom climate crisis/drought seminars for staff/community activists.

Prof. John Veverka jvainterp@aol.com