43 minute read

Andrew Freedman

Unprecedented heat wave in Pacific Northwest starts roasting the region

Andrew Freedman June 25, 2021

Advertisement

The most severe heat wave on record in the Pacific Northwest and southwestern Canada kicks into high gear Friday and will intensify throughout the weekend and into next week.

Why it matters: Heat waves like this one are significant public health threats, particularly in areas like the Northwest, where many people lack air conditioning.

Extreme heat tends to be the biggest weather-related killer each year in the U.S., outranking even tornadoes and hurricanes.

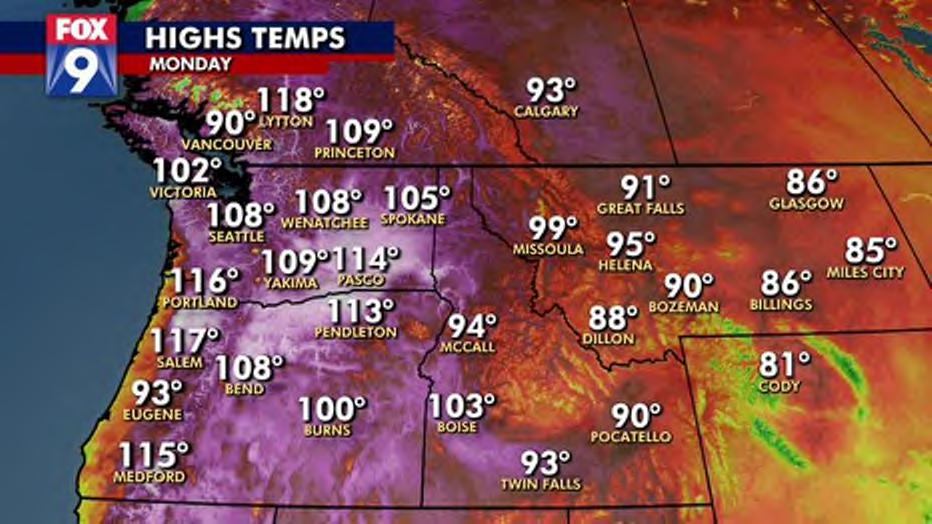

Numerous daily, monthly and all-time high temperature records will be shattered.

More than 13 million residents from Northern California through much of Oregon and Washington, and eastward to Idaho are under excessive heat warnings.

The big picture: Extreme heat events are directly tied to human-caused global warming, with studies showing that severe heat events are now on average about 3°F to 5°F hotter than they would be without emissions of greenhouse gases from fossil fuel burning, deforestation and other activities. Some recent studies have shown that certain extreme heat events could not have occurred without the added boost from human-caused warming.

What they're saying: NWS forecasters in Seattle said Friday they “have never seen Pacific Northwest data like this.”The National Weather Service, which is typically cautious in its word choices with the public, is not holding back in its messaging this time around. The agency's forecast office in Portland, for example, issued a forecast discussion Friday morning stating, "...UNPRECEDENTED HEAT WAVE EXPECTED THIS WEEKEND INTO NEXT WEEK..." Agency social media accounts have also been relaying hot weather safety tips and directing people to cooling shelters.

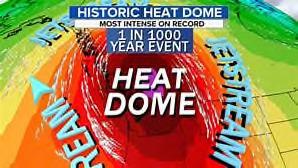

Driving the news: A highly unusual weather pattern is setting up over the Pacific Northwest, with a recordstrong high-pressure area aloft — known as a "heat dome" — settling over the region and intensifying through Monday. Such a heat dome, if it reaches the strength that computer models are projecting, would yield temperature departures from average of between 25 and 45°F across multiple states and British Columbia.

InterpNEWS

Weather balloons launched from NWS offices in the Northwest Friday found the freezing level at or above 18,000 feet in some areas, prompting concerns about meltwater runoff from unusually warm weather affecting mountain snow fields and glaciers.

This heat, combined with a worsening drought, will raise the risk of wildfires across multiple Western states.

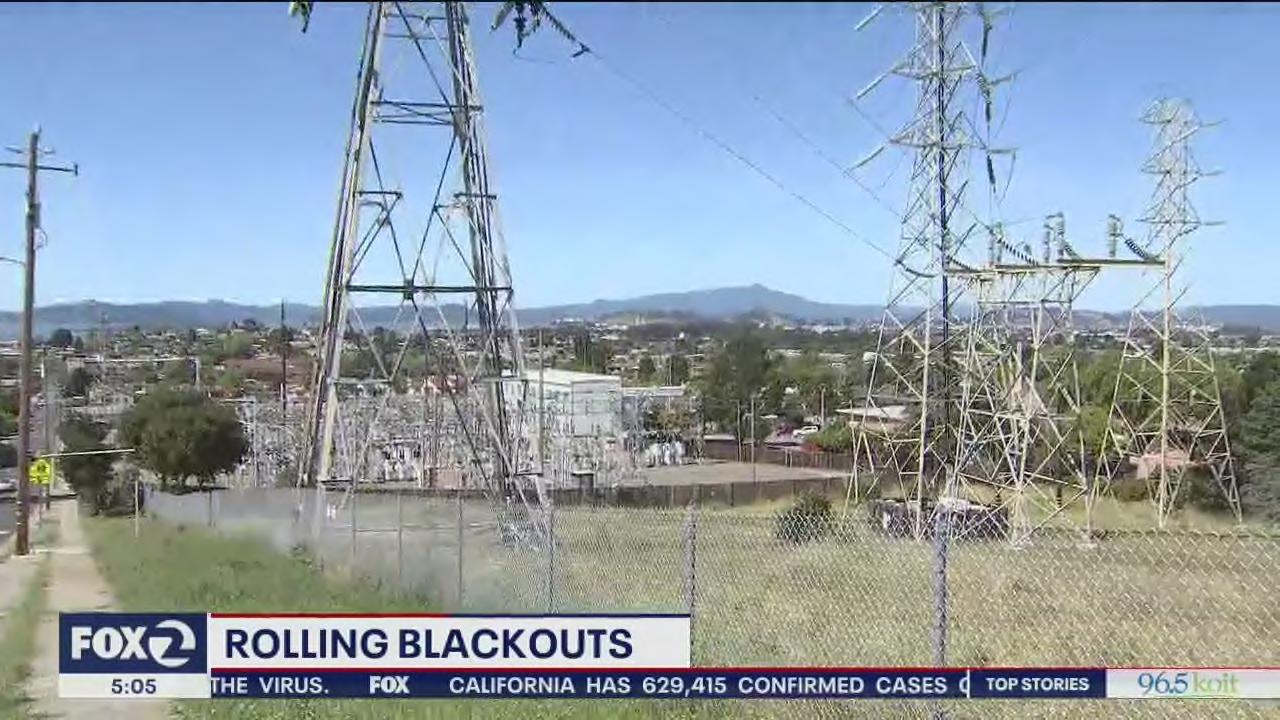

It will also cause power demand to spike.

By the numbers: Virtually all of Oregon and Washington, plus portions of California, Idaho and Montana, are under excessive heat watches and warnings. This is the case even in downtown Portland and Seattle.

Portland, Oregon, is forecast to reach low triple-digits on Saturday through at least Monday. The city is likely to break its June heat record, its record for most 100-degree days in June, and surpass its all-time high of 107°F, perhaps by a few degrees.

In Seattle, where the average high temperature this time of year is in the low-to-mid 70s, the National Weather Service (NWS) predicts a high of 102°F on Sunday, which would break the record for the city's hottest temperature during the month of June.

Seattle's all-time high temperature record is 103°F, and the city has only seen three 100-degree days in its history.

Medford, Oregon and Spokane, Washington, are also predicted to shatter their all-time high temperature record by a few degrees.

The heat will be most intense in inland areas of Washington and Oregon. There, temperatures are forecast to soar to between 100°F and 115°F on Saturday through Tuesday, and remain extremely hot through much of next week.

Nearly every location along the I-5 corridor from Northern California to Washington is likely to set a monthly or even an all-time high temperature record during this event.

Canada will also see extreme heat, and it's possible the country's all-time high temperature record of 113°F (45°C) will be equaled or eclipsed.

How it works: One of the reasons why the Pacific Northwest will get so hot is that the core of the heat dome will be parked to the north-northeast of the region for several days.

Due to the clockwise flow of air around the high, this will produce surges of air moving from high-to-lower elevation areas in Idaho, Washington and Oregon.

When air sinks, such as when it moves out of mountainous regions and into valleys, it compresses, increasing temperatures and getting drier in the process

How Does a Heat Wave Affect the Human Body?

Some might like it hot, but extreme heat can overpower the human body. An expert from the CDC explains how heat kills and why fans are worthless in the face of truly high temperatures

By Katherine Harmon

Climate change promises to bring with it longer, hotter summers to many places on the planet. This June turned out to be the fourth-hottest month ever recorded—globally—scientists are reporting. With more heat waves on the horizon, and a big one currently sweeping much of the U.S., the risk of heat-related health problems has also been on the rise.

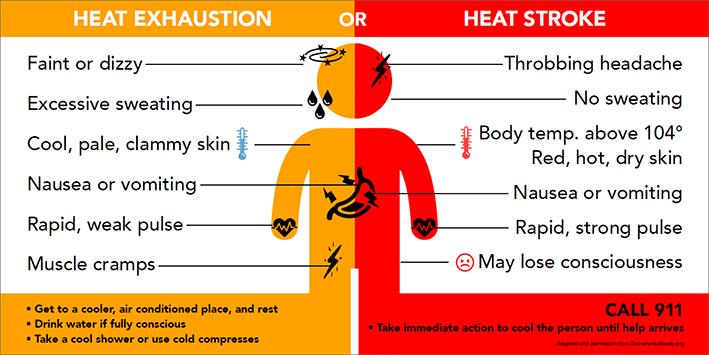

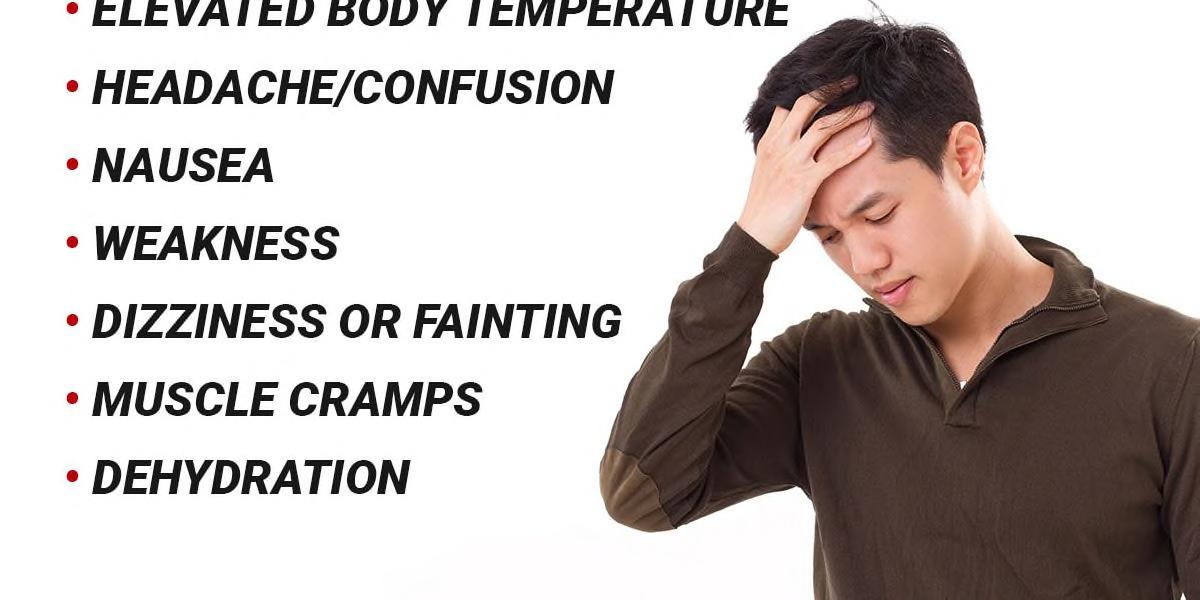

Heat exhaustion is a relatively common reaction to severe heat and can include symptoms such as dizziness, headache and fainting. It can usually be treated with rest, a cool environment and hydration (including refueling of electrolytes, which are necessary for muscle and other body functions). Heat stroke is more severe and requires medical attention—it is often accompanied by dry skin, a body temperature above 103 degrees Fahrenheit, confusion and sometimes unconsciousness.

Extreme heat is only blamed for an average of 688 deaths each year in the U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). But when sustained heat waves hit a region, the other health ramifications can be serious, including sunstroke and even major organ damage due to heat. The Chicago heat wave in the summer of 1995 killed an estimated 692 people and sent at least 3,300 people to the emergency room. An observational study of some of those patients revealed that 28 percent who were diagnosed at the time with severe heat stroke had died within a year of being admitted to the hospital, and most who initially survived the high temperatures had "permanent loss of independent function," according to a 1998 study of the heat wave, published in Archives of Internal Medicine.

As temperatures linger above our bodies' own healthy internal temperature for longer periods of time, will we humans be able to take the heat? We spoke with Mike McGeehin, director of the CDC's Environmental Hazards and Health Effects Program, to find out just why—and how—a warm, sunny summer day can do us in.

How do humans cope with hot, hot weather?

The two ways we cope with heat are by perspiring and breathing.

So is it the heat or humidity that is the real killer?

The humidity is a huge factor. If you have tremendously high temperatures and high humidity, a person will be sweating but the sweat won't be drying on the skin. That’s why it's not just heat but the combination of heat and humidity that matters. That combination results in a number called the apparent temperature or "how it feels".

Obviously there are thresholds for both temperature and humidity above which we see an increase in death, and it's going to be a different temperature in Phoenix than it's going to be in Chicago.

The other major factor in terms of temperature that causes both mortality and morbidity is the temperature that it falls to in the evening. If the temperature remains elevated overnight, that's when we see the increase in deaths. The body becomes overwhelmed because it doesn't get the respite that it needs.

What kind of impact does extreme, sustained heat have on the human body?

The systems in the human body that enable it to adapt to heat become overwhelmed. When a person is exposed to heat for a very long time, the first thing that shuts down is the ability to sweat. We know that when perspiration is dried by the air there is a cooling effect on the body. Once a person stops perspiring, in very short order a person can move from heat exhaustion to heat stroke.

What happens in the transition from heat exhaustion to heat stroke?

It begins with perspiring profusely, and when that shuts down, the body becomes very hot. Eventually that begins to affect the brain, and that's when people begin to get confused and can lose consciousness.

The analogy we use is if you're driving a car and you notice that the temperature light comes on, what's happening is the cooling system of the car is becoming overwhelmed. If you turn off the car and let it cool eventually you can start driving again. But if you continue to drive the car, the problem goes beyond the cooling system to affect the engine, and eventually the car will stop.

What other areas of the body does this extreme overheating affect?

As the body temperature increases very rapidly, the central nervous system and circulatory system are impacted.

In places where there have been prolonged heat exposures, there is probably a broad impact on many organ systems. From heat waves that have been studied, like in Chicago, there are increases in emergency department visits and hospital stays for medical crises that are not normally associated with heat, such as kidney problems.

But it really hasn't been studied very much. One of the reasons for that is the main focus of the studies has been on mortality from heat waves, and there hasn't been that much focus on morbidity. That would take looking at people who are hospitalized from heat exhaustion or heat stroke and following them into the future.

Before someone gets full-blow heat stroke, what are the body's early reactions to excessive heat?

Heat rash and muscle cramps are early signs of people being overwhelmed by heat. If those aren't dealt with, it can lead to more severe symptoms.

Cramping of muscles can be for a number of different issues, including electrolytes not getting to the muscles.

People should be aware that their skin turning red and dry are indicators that heat is impacting them.

Who is the most vulnerable to extended high temperatures?

We know the risk factors for dying from heat are urban dwellers who are elderly, isolated and don't have access to air conditioning. Obese people are at increased risk as are people on certain medications. And people who are exercising or working in the heat, who don't meet those criteria, can be at risk.

What medications can make the body more susceptible to extreme heat?

In the study from the 1995 Chicago heat wave, we found that diuretics for high blood pressure were some that did, and beta blockers—a number of studies showed that people taking them could be at increased risk.

There are some studies that have shown that certain mental health medications may impact a person's ability to deal with the heat. But that's a difficult one to get at. When you look at the number of people who die in a heat wave and the number of people who are taking those medications, the numbers can get pretty small pretty quickly.

What's the hottest temperature a healthy human can tolerate?

We don't know that—no one knows that. There are different humans, different humidities, different types of temperature.

Have we not evolved to cope with super hot weather?

Certainly society has evolved in dealing with the heat—and that has been in the development of air conditioners. The number-one factor that ameliorates death from heat is access to air conditioning.

And I've read that fans don't work to prevent overheating in really hot temperatures…

Not only does it not work, it actually makes it worse. We compare it to a convection oven. By blowing hot air on a person, it heats them up rather than cools them down.

Are modern humans neglecting to do something our ancestors did to survive the heat?

I think it's always been a problem. There's history over hundreds of years of people dying of heat. Philadelphia in 1776 had a major heat wave that caused deaths.

We're also living to older ages, and we're more urban now than we have been in the history of the human species. That intense crowding can combine with the heat island effect in big cities. Our elderly people are also more isolated than they have been in the past, so those factors can play a part, too.

The IPCC, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the thing that they are most comfortable in predicting, that the science is most solid for, is the increase in many parts of the world in the duration and intensity of heat waves.

Heat Waves and Climate Change. Heat Waves and Climate Change.

Russel Vose,

Across the globe, hot days are getting hotter and more frequent, while we’re experiencing fewer cold days. Across the globe, hot days are getting hotter and more frequent, while we’re experiencing fewer cold days. Over the past decade, daily record high temperatures have occurred twice as often as record lows daily record high temperatures have occurred twice as often as record lows continental United States, up from a near 1:1 ratio in the 1950s. continental United States, up from a near 1:1 ratio in the 1950s. Heat waves are becoming more common intense heatwaves are more frequent in the U.S. West, although in many parts of the country the 1930s still are more frequent in the U.S. West, although in many parts of the country the 1930s still holds the record for number of heat waves (caused by the Dust Bowl and other factors). holds the record for number of heat waves (caused by the Dust Bowl and other factors). By midcentury, if greenhouse gas emissions are not significantly curtailed, th By midcentury, if greenhouse gas emissions are not significantly curtailed, the coldest and warmest daily temperatures are expected to increase by at least 5 degrees F in most areas by mid by at least 5 degrees F in most areas by mid-century rising to 10 degrees F by late century. The National Climate Assessment est degrees F by late century. The National Climate Assessment estimates 20-30 more days over 90 degrees F in most areas by mid-century. A recent study projects that the century. A recent study projects that the annual number of days with a heat index above 100 degrees F will double, and days with a heat index above 105 degrees F will triple, nationwide, when , and days with a heat index above 105 degrees F will triple, nationwide, when compared to the end of the 20th century. century. across the Heat waves are becoming more common, and coldest and warmest daily century rising to 10 30 more days over 90 degrees F in annual number of days with a heat index above

NOTES

Projected changes in the number of days per year with a maximum temperature above 90°F and a minimum Projected changes in the number of days per year with a maximum temperature above 90°F and a minimum temperature below 32°F in the contiguous United States. temperature below 32°F in the contiguous United States. Changes are the difference between the average for Changes are the difference between the average for mid-century (2036–2065) and the average for near 2065) and the average for near-present (1976–2005) under the higher scenario 2005) under the higher scenario (RCP8.5). This map depicts a weighted multi This map depicts a weighted multi-modal mean of 32 climate model projections. modal mean of 32 climate model projections.

SOURCE

CICS-NC and NOAA NCEI by Russel Vose, available in AA NCEI by Russel Vose, available in Climate Science Special Report Climate Science Special Report. Extreme heat can increase the risk of other types of disasters. Heat can exacerbate drought drought, and hot dry conditions can in turn create wildfire conditions. In cities, buildings roads and infrastructure can be heated than the air while natural surfaces remain closer to air temperatures. The heat island effect is most intense during the day, but the slow release of heat from the infrastructure overnight (or an keep cities much hotter than surrounding areas. Rising temperatures across the country poses a threat to people, ecosystems and the economy.

Threats Posed by Extreme Heat

Extreme heat can increase the risk of other types of disasters. Heat can exacerbate conditions can in turn create wildfire conditions. In cities, buildings roads and infrastructure can be heated to 50 to 90 degrees hotter than the air while natural surfaces remain closer to air temperatures. The heat island effect is most intense during the day, but the slow release of heat from the infrastructure overnight (or an atmospheric heat island) can keep cities much hotter than surrounding areas. Rising temperatures across the country poses a threat to people, ecosystems and the economy.

Human Health

Extreme heat is one of the leading causes of weather-related deaths in the United States, killing an average of more than 600 per year from 1999-2009, more than all other impacts (except hurricanes) combined. The Billion Dollar Weather Disasters database compiled by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration lists heat waves as four of the top 10 deadliest U.S. disasters since 1980.

Heat stress occurs in humans when the body is unable to cool itself effectively. Normally, the body can cool itself through sweating, but when humidity is high, sweat will not evaporate as quickly, potentially leading to heat stroke. High humidity and elevated nighttime temperatures are likely key ingredients in causing heatrelated illness and mortality. When there’s no break from the heat at night, it can cause discomfort and lead to health problems, especially for those who are low income or elderly, if access to cooling is limited.

Hot days are also associated with increases in heat-related illnesses including cardiovascular and respiratory complications, kidney disease, and can be especially harmful to outdoor workers, children, the elderly, and low-income households.

In extreme temperatures, air quality is also affected. Hot and sunny days can increase ozone levels, which in turn affects NOX levels. In addition, greater use of heating and cooling of indoor spaces requires more electricity and, depending on the electricity source, can emit more of other types of pollution, including particulates. These increases in ozone and particulate matter can pose serious risks to people, particularly the same vulnerable groups directly impacted by heat mentioned above.

Agriculture

High temperatures at night can be particularly damaging to agriculture. Some crops require cool night temperatures, and heat stress for livestock rises when animals are unable to cool off at night. Heat-stressed cattle can experience declines in milk production, slower growth, and reduced conception rates.

Energy

While higher summer temperatures increase electricity demand for cooling, at the same time, it also can lower the ability of transmission lines to carry power, possibly leading to electricity reliability issues during heat waves. Although warmer winters will reduce the need for heating, modeling suggests that total U.S. energy use will increase in a warmer future. In addition, as rivers and lakes warm, their capacity for absorbing waste heat from power plants declines. This can reduce the thermal efficiency of power production, which makes it difficult for power plants to comply with environmental regulations regarding their cooling water.

How to Build Resilience

A set of strategies to build resilience to extreme heat are laid out in our publication, “Resilience Strategies for Extreme Heat.” Some strategies include: - Creating heat preparedness plans, identifying vulnerable populations, and opening cooling centers during extreme heat. - Installing cool and green roofs and cool pavement to reduce the urban heat island effect.

- Planting trees to provide shade and evapotranspiration cools the air around trees.

- Pursuing energy efficiency to reduce demand on the electricity grid, especially during heat waves.

China could face deadly heat waves due to climate change

One of the world’s most densely populated regions may push the boundaries of habitability by the end of this century, study finds.

David L. Chandler | MIT News Office

Caption: “This spot is just going to be the hottest spot for deadly heat waves in the future, especially under climate change,” says Professor Elfatih Eltahir.

A region that holds one of the biggest concentrations of people on Earth could be pushing against the boundaries of habitability by the latter part of this century, a new study shows.

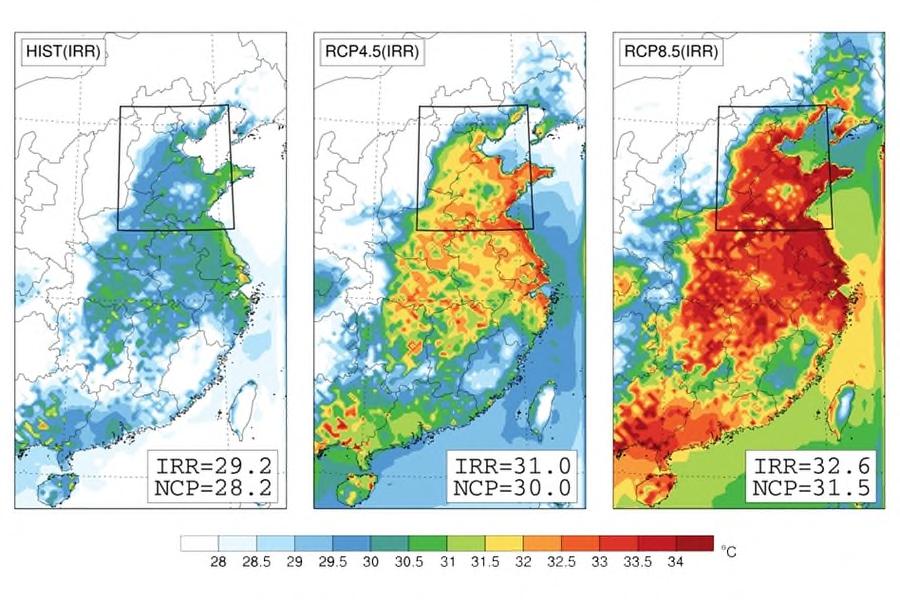

Research has shown that beyond a certain threshold of temperature and humidity, a person cannot survive unprotected in the open for extended periods — as, for example, farmers must do. Now, a new MIT study shows that unless drastic measures are taken to limit climate-changing emissions, China’s most populous and agriculturally important region could face such deadly conditions repeatedly, suffering the most damaging heat effects, at least as far as human life is concerned, of any place on the planet.

The study shows that the risk of deadly heat waves is significantly increased because of intensive irrigation in this relatively dry but highly fertile region, known as the North China Plain — a region whose role in that country is comparable to that of the Midwest in the U.S. That increased vulnerability to heat arises because the irrigation exposes more water to evaporation, leading to higher humidity in the air than would otherwise be present and exacerbating the physiological stresses of the temperature.

The new findings, by Elfatih Eltahir at MIT and Suchul Kang at the Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology, are reported in the journal Nature Communications. The study is the third in a set; the previous two projected increases of deadly heat waves in the Persian Gulf area and in South Asia. While the earlier studies found serious looming risks, the new findings show that the North China Plain, or NCP, faces the greatest risks to human life from rising temperatures, of any location on Earth.

“The response is significantly larger than the corresponsing response in the other two regions,” says Eltahir, who is the the Breene M. Kerr Professor of Hydrology and Climate and Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering. The three regions the researchers studied were picked because past records indicate that combined temperature and humidity levels reached greater extremes there than on any other land masses. Although some risk factors are clear — low-lying valleys and proximity to warm seas or oceans — “we don’t have a general quantitative theory through which we could have predicted” the location of these global hotspots, he explains. When looking empirically at past climate data, “Asia is what stands out,” he says.

Although the Persian Gulf study found some even greater temperature extremes, those were confined to the area over the water of the Gulf itself, not over the land. In the case of the North China Plain, “This is where people live,” Eltahir says.

The key index for determining survivability in hot weather, Eltahir explains, involves the combination of heat and humidity, as determined by a measurement called the wet-bulb temperature. It is measured by literally wrapping wet cloth around the bulb (or sensor) of a thermometer, so that evaporation of the water can cool the bulb. At 100 percent humidity, with no evaporation possible, the wet-bulb temperature equals the actual temperature.

People sleeping in a subway station floor to escape the heat

This measurement reflects the effect of temperature extremes on a person in the open, which depends on the body’s ability to shed heat through the evaporation of sweat from the skin. At a wet-bulb temperature of 35 degrees Celsius (95 F), a healthy person may not be able to survive outdoors for more than six hours, research has shown. The new study shows that under business-as-usual scenarios for greenhouse gas emissions, that threshold will be reached several times in the NCP region between 2070 and 2100.

“This spot is just going to be the hottest spot for deadly heat waves in the future, especially under climate change,” Eltahir says. And signs of that future have already begun: There has been a substantial increase in extreme heat waves in the NCP already in the last 50 years, the study shows. Warming in this region over that period has been nearly double the global average — 0.24 degrees Celsius per decade versus 0.13. In 2013, extreme heat waves in the region persisted for up to 50 days, and maximum temperatures topped 38 C in places. Major heat waves occurred in 2006 and 2013, breaking records. Shanghai, East China’s largest city, broke a 141-year temperature record in 2013, and dozens died.

To arrive at their projections, Eltahir and Kang ran detailed climate model simulations of the NCP area — which covers about 4,000 square kilometers — for the past 30 years. They then selected only the models that did the best job of matching the actual observed conditions of the past period, and used those models to project the future climate over 30 years at the end of this century. They used two different future scenarios: business as usual, with no new efforts to reduce emissions; and moderate reductions in emissions, using standard scenarios developed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Each version was run two different ways: one including the effects of irrigation, and one with no irrigation.

One of the surprising findings was the significant contribution by irrigation to the problem — on average, adding about a half-degree Celsius to the overall warming in the region that would occur otherwise. That’s because, even though extra moisture in the air produces some local cooling effect at ground level, this is more than offset by the added physiological stress imposed by the higher humidity, and by the fact that extra water vapor — itself a powerful greenhouse gas — contributes to an overall warming of the air mass.

“Irrigation exacerbates the impact of climate change,” Eltahir says. In fact, the researchers report, the combined effect, as projected by the models, is a bit greater the sum of the individual impacts of irrigation or climate change alone, for reasons that will require further research.

The bottom line, as the researchers write in the paper, is the importance of reducing greenhouse gas emissions in order to reduce the likelihood of such extreme conditions. They conclude, “China is currently the largest contributor to the emissions of greenhouse gases, with potentially serious implications to its own population: Continuation of the current pattern of global emissions may limit habitability of the most populous region of the most populous country on Earth.”

“This is a solid piece of research, extending and refining some of the previous studies on man-made climate change and its role on heat waves,” says Christoph Schauer, a professor of atmospheric and climate science at ETH Zurich, who was involved in the work. “This is a very useful study. It highlights some of the potentially serious challenges that will emerge with unabated climate change. … These are important and timely results, as they may lead to adequate adaptation measures before potentially serious climate conditions will emerge.”

Schauer adds that “While there is overwhelming evidence that climate change has started to affect the frequency and intensity of heat waves, century-scale climate projections imply considerable uncertainties” that will require further study. However, he says, “Regarding the health impact of high wet-bulb temperatures, the applied health threshold (wet-bulb temperatures near the human body temperature) is very solid and it actually derives from fundamental physical principles.”

Ageing population will compound deadly effects of heatwaves caused by climate change

A combination of global warming and population growth means more people will be exposed to extreme weather systems, with an ageing population particularly at risk from heatwaves, says Royal Society (UK)

Heatwaves are particularly dangerous for people over 65. An increase in their regularity due to climate change and a rising elderly population means more people will be at risk from their effects, say Royal Society. Photograph: Valery Hache/AFP/Getty Images

The double whammy of global warming and a growing, ageing population will mean peoples’ exposure to deadly heatwaves will multiply tenfold this century, according to a new report from the Royal Society.

The researchers from the UK’s science academy warn the world is not prepared for the extreme weather which is already being exacerbated by climate change today.

The world’s population is expected to swell from 7bn today to a peak of 10bn by mid-century, and the new analysis examines for the first time how this boom will affect the number of people hit by extreme weather, if the relentless rise in carbon emissions is not reversed.

The combination of population growth and climate change means the impacts of flooding around the world will be increased fourfold and drought impact will be trebled. The report also warns that failure to prepare for more extreme weather would cause huge economic damage, meaning entire nations having their credit ratings downgraded and major companies going bust.

Heatwaves are the climate impact most exacerbated by population changes, because they are particularly dangerous for people over 65 and the global population is ageing quickly.

The greying populations of UK and western Europe mean the region is particularly affected by this multiplication affect. In 2003, a 20-day heatwave killed 52,000 people across Europe but. Without action on climate change, once-rare heatwaves will happen every other year by 2100.

The US, China and north Africa will also be among those suffering from the magnified impact of heatwaves. The combined climate-population damage from flooding and droughts will be felt heavily in western Europe, while India and sub-Saharan Africa will be struck by all three types of extreme weather.

“Extreme weather has a huge impact on society and globally we are not resilient even now,” said Professor Georgina Mace, from University College London and who led the group of 24 physical, social and economic scientists. “This is why we have seen these horrible events [like typhoon Haiyan and hurricane Sandy] in the past few years, with many people affected. If we continue on our current trajectory the problem is likely to get much worse as our climate and population change.”

The damages are severe in both harm to people and property, the report stated. Extreme-weather damage cost $1.4 trillion (£0.9 trillion) from 1980-2004, of which only a quarter was insured. People in the poorest nations make up just 11% of those exposed to hazards but suffered over half the deaths from disasters.

Douglas said it was also vital that the cost of extreme weather damage is built into the world’s economic and financial systems, to ensure that long-term protection measures are seen as good value for money. He said the insurance industry had already been forced to change.

“What was an existential risk to the insurance sector is now, at the least, a material risk for the financial wellbeing of the wider economy,” Douglas said. “The credit rating agencies are seriously exploring extending techniques used to stress test insurance companies against extreme weather and disaster risk to corporates and potentially nations. They recognise there is a risk now that needs to be properly managed.”

Asked if countries or companies could have their credit ratings downgraded because they were not properly managing the risk of extreme weather to their economies or solvency, Douglas said: “Absolutely yes.”

Prof Andrew Watkinson, at the University of East Anglia and not part of the research team, said: “This timely report reminds us that extreme weather events affect us all, that we are not as resilient to current extreme events as we could be, and that the nature of extreme events is likely to change in the future. At a time when deep cuts are being made in public spending it is essential that government does not lose sight of its key role in enabling resilience.”

Deadly Degrees: Why Heat Waves Kill So Quickly

Stephanie Pappas LiveScience

Heat exhaustion can be reversed if a person experiencing heat-illness symptoms cools off, say by pouring cool water on their body. (Image credit: Jim David / Shutterstock.com)

An intense heat wave that sent temperatures in Phoenix to 118 degrees Fahrenheit (47.7 degrees Celsius) this weekend has killed four people — and the heat could be worse today.

Those killed so far were all hiking or biking outdoors, but heat waves can kill close to home, too. In 2003, during a major European heat wave, 14,802 people died of hyperthermia in France alone. Most were elderly people living alone in apartment buildings without air conditioning, according to Richard Keller, a University of Wisconsin-Madison professor of medical history and bioethics and author of "Fatal Isolation: The Devastating Paris Heat Wave of 2003" (University of Chicago Press, 2015).

So how does heat kill? When core body temperature rises too high, everything breaks down: The gut leaks toxins into the body, cells begin to die, and a devastating inflammatory response can occur. [7 Common Summer Health Concerns]

Part of the insidiousness of heat-related deaths is how quickly they can happen. According to ABC15 News, a mountain biker who died near Phoenix was a fit 28-year-old who had consumed plenty of water and was biking with two doctors. Her pulse stopped at around 9 a.m. on Sunday (June 19). Despite immediate resuscitation efforts, she could not be saved.

Sudden death

The deaths so far in Arizona aren't typical heat deaths, Keller told Live Science. Rather, they're "like shots across the bow telling you that something is coming," he said. Outdoorsy types and outdoor workers like roofers might suffer first, but it's the elderly and the mentally ill who make up the majority of deaths.

The medical term for excessive body heat is hyperthermia. The first phase is heat exhaustion, a condition marked by heavy sweat, nausea, vomiting and even fainting. The pulse races, and the skin goes clammy. Muscle cramping can be an early sign of heat exhaustion, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Heat exhaustion can be reversed by moving to a cool location, loosening clothing and applying cool, wet washcloths to the body. But when people with heat exhaustion can't find relief, they can quickly advance to heat stroke. This condition happens when a person's core body temperature rises above 104 degrees F (40 degrees C). (This number is something of an estimate; there are a few degrees' variability among people as to how much internal heat they can tolerate.)

In heat stroke, sweating stops and the skin becomes dry and flushed. The pulse is rapid. The person becomes delirious and may pass out. When trying to compensate for extreme heat, the body dilates the blood vessels in the skin in an attempt to cool the blood. To do this, the body has to constrict the blood vessels in the gut. The reduced blood flow to the gut increases the permeability between the cells that normally keep gut contents in, and toxins can leak into the blood, according to a book chapter in the textbook Wilderness Medicine (Mosby, 2011).

These leaky toxins trigger a massive inflammatory response in the body, so massive that the attempt to fight off the toxins damages the body's own tissues and organs. It can be hard to tell what damage is caused directly by heat and what is caused by the secondary effects of toxins, according to Wilderness Medicine. Muscle cells break down, spilling their contents into the bloodstream and overloading the kidneys, which in turn start to fail, a condition called rhabdomyolysis. [Roasting? 7 Scientific Ways to Beat the Heat]

Proteins in the spleen start to clump as a direct result of heat; they're essentially cooked. The blood-brain barrier that normally keeps pathogens out of the brain becomes more permeable, allowing dangerous substances into the brain. Autopsies of people killed by heat stroke often reveal microhemorrhages (tiny strokes) and swelling, and 30 percent of heat stroke survivors experience permanent damage in brain function, according to Wilderness Medicine.

Far from help

As many as 10 percent of people who experience heat stroke die, according to the American Association of Family Physicians (AAFP). Heat exhaustion requires immediate medical treatment and rapid cooling. In the case of a hiker on a trail, there may not be time to get to a spot that's cool enough to reverse the damage. Similarly, people who live in urban areas and lack air conditioning may end up disabled in their own homes, unable to get help before they die from heat stroke.

The elderly and those with chronic medical conditions have more difficulty regulating their body temperatures than those in midlife, Keller said, and medications for some chronic diseases can make the problem worse. Likewise, the signals between body and brain that make people feel thirsty may not function as well in old age. (Babies and young children also have more difficulty regulating their temperature than people in the prime of life.)

The elderly, neurologically disabled and mentally ill also tend to be more socially isolated than their younger, healthier counterparts.

"They tend to find themselves socially isolated," Keller said. "And that's really, far and away, the biggest risk factor for dying during a heat wave."

In France in 2003, the heat hit in August, when many Europeans go on vacation. Elderly people found themselves in mostly empty apartment buildings when the heat crisis reached them. Some were found dead with their doors ajar, Keller said, suggesting that they were trying to get out and get help when they collapsed.

Others were functionally trapped, he said. An 80-year-old in a seventh-floor walkup who recently had hip surgery can't get down the stairs by themselves.

"They had no way to seek help," Keller said.

Finally, some may not have realized the severity of the situation. A 2013 analysis by the New York Department of Health and Mental Hygiene found that people who died of heat stroke in that city were not necessarily more likely to live alone than people who survived, in contrast to the 2003 European heat wave. However, the people who died in New York might not have been aware of the warning signs of heat stroke, the researchers wrote. Some people during the European heat wave probably thought they were going through an uncomfortable time and didn't recognize how precarious their survival was, Keller said. Phoenix, Tucson and other cities hit by the current heat wave are built for extreme temperatures, Keller said, so they're unlikely to see high levels of mortality. Most at-risk are low-income people or those living in marginal housing, such as mobile homes, he said.

Arizona's Department of Health Services has shared the following tips for preventing heat illness: Drink at least 2 liters (about a half-gallon) of water per day if you are mostly indoors and 1 to 2 additional liters for every hour of outdoor time. Drink before you feel thirsty, and avoid alcohol and caffeine. Wear lightweight, light-colored clothing and use a sun hat or an umbrella to deflect the sun's rays. Eat smaller, more frequent meals instead of large ones.

Avoid strenuous activity.

Stay indoors as much as possible.

Take regular breaks if you must exert yourself on warm days.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science. She covers the world of human and animal behavior, as well as paleontology and other science topics.

How Much Do Heat Waves Cost Us? How Much Do Heat Waves Cost Us?

Kimberly Amadeo Updated January 30, 2021 Heat Waves and Their Effect on the Economy (thebalance.com) Heat Waves and Their Effect on the Economy (thebalance.com)

A heat wave is a period of unusually hot weather lasting two or more days. The temperature is hotter than average for the region. In an extreme heat wave, temperatures break records. The frequency, severity, and length of heat waves are increasing.1 Heat and humidity already kill an average of 600 people 20 days affect 30% of the earth’s population. That could increase to 74% by 2100 if global warming isn’t stopped.3 period of unusually hot weather lasting two or more days. The temperature is hotter than average for the region. In an extreme heat wave, temperatures break records. The frequency, severity, and kill an average of 600 people in the U.S. each year.2 Deadly heat waves of at least 20 days affect 30% of the earth’s population. That could increase to 74% by 2100 if global warming isn’t

Deadly heat waves of at least Heat Index reaches a certain level within the next 12 to 24 hours. day heat wave. A heat advisory

National Weather Service Warnings National Weather Service Warnings

The U.S. National Weather Service notifies residents of upcoming heat waves. It uses a National Weather Service notifies residents of upcoming heat waves. It uses a Value also called the apparent temperature. It factors in humidity with the air temperature in degrees also called the apparent temperature. It factors in humidity with the air temperature in degrees Fahrenheit.4 The NWS issues a Heat Advisory when the heat index The NWS issues a Heat Advisory when the heat index reaches a certain level within the next 12 to 24 hours. The trigger point depends on average temperatures and is different for each locality. The advisory may be The trigger point depends on average temperatures and is different for each locality. The advisory may be issued for lower temperatures if it is early in the season or during a multi issued for lower temperatures if it is early in the season or during a multi-day heat wave. A means that people could be affected by heat. It warns them to take precautions. It also triggers public safety means that people could be affected by heat. It warns them to take precautions. It also triggers public safety regulations. These can include a ban on evictions and electricity shutoffs. regulations. These can include a ban on evictions and electricity shutoffs.

InterpNEWS

The NWS issues an Excessive Heat Warning when higher heat levels are expected within the next 12 to 24 hours. At those temperatures, some people can be seriously affected or die if they don't take precautions. The warning alerts hospitals to prepare for an increase in emergency calls. It activates programs that check on the home-bound. Some cities will open public air-conditioned centers. It also triggers the same public safety regulations as a heat advisory.

An Excessive Heat Watch is a warning issued one to two days in advance of the heat wave.5

Heat Wave 2019

The World Meteorological Organization called July 2019 the hottest month in history. It beat the previous record in July 2016. That's without the El Nino warming effect that boosted temperatures in 2016. Cities across Europe hit record temperature, including Paris at 108.7 F. Greenland experienced one of the most significant melt events ever recorded.6 It poured 197 billion tons of water into the North Atlantic, enough to raise the global sea level by 0.02 inches.7 Wildfires scorched Alaska and Siberia

OnMemorial Day weekend 2019, a heat wave hit the Southeastern United States. Six cities tied or set record temperatures. A wobbly jet stream pulled hot air from the south. At the same time, it pushed cold air from the north onto the Southwest, sending temperatures down into the 70s.88

Heat Wave 2018

In July 2018, heat waves set new temperature records all over the world. Death Valley had the hottest month ever recorded on Earth. The average temperature was 108 F.9 Caribou, Maine, reported that July was its warmest month ever.10 So did 22 counties and cities in China.

Several towns reached new highs, including Los Angeles at 111 F, Amsterdam at 94.6 F, and London at 95 F. On July 5, 2018, Ouargla, Algeria, reported 124.34 F, the highest temperature reliably recorded in Africa. Climate scientists were shocked by the sudden onset of these extreme events. The urban heat island effect makes city daytime temperatures 1-7 F hotter and nighttime temperatures 2-5 F hotter.11

Causes A heat wave is caused by a high-pressure system that hovers over an area. It traps heat beneath it like an oven. High-pressure systems force air downward. Hot air on the ground cannot escape into higher levels. Without rising air, there are no rain or clouds. The sun just bakes the area until a new pressure system is strong enough to push the high-pressure system away.

Climate change increases heat waves by increasing the Earth's average temperature. How much has it warmed? Since the 1880s, the earth’s average temperature has risen a little more than two degrees Fahrenheit or one degree Celsius. Global warming is occurring at a faster rate than at any other time in the Earth's history.12

In the northern hemisphere, global warming is changing the jet stream. That’s a river of wind formed when cold Arctic air meets warm southern air. But the Arctic is warming faster than the south. The jet stream slows down and becomes wavy. That allows heat waves to linger.13

Effects

Over the past 30 years, heat waves have killed more people than all other weather-related natural disasters combined.14 Heat waves kill in four ways:

1. Heat stress causes dehydration and loss of body salt. That throws off the chemistry of the body. 2. As the body tries to ol, it taxes the heart. That can lead to failure in people with heart conditions15 3. When the core body temperature rises beyond 104 F, organs fail. The gut leaks toxins into the body, creating a deadly inflammatory response called heat stroke16 4. People drown while trying to cool off in lakes and rivers.

Heat waves are most likely to affect people who work or live outdoors. The Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that half of all U.S. workers have jobs that require them to be outdoors. Of those, 6.1 million are in construction, 4.6 million are in logistics, and 2.1 million are in agriculture.17 In July 2018, a United States Postal Service worker died on the job when the temperature hit 117 F.

Also at risk are those without air conditioning. Worker productivity declines by 2% for every degree Celsius above normal room temperature.18

The elderly, injured, and children are most threatened. People on certain medications that curb their ability to sweat are also at risk. Alcoholic consumption worsens the effect of heat waves.

Heat waves contributed to the record wildfire season in the American West. The heat dried out vegetation, creating tinder for fires. Scientists were surprised that the heat was enough to overcome soil that was still moist from a wetter than normal winter. Wildfires are driven more by the temperature and moisture content in the air than by the moisture content in the soil.

Heat waves contributed to the record wildfire season in the American West. The heat dried out vegetation, creating tinder for fires. Scientists were surprised that the heat was enough to overcome soil that was still moist from a wetter than normal winter. Wildfires are driven more by the temperature and moisture content in the air than by the moisture content in the soil.

Heat waves could be the reason behind the 45 to 75% decline in worldwide insect populations. Warmer temperatures make males less fertile by reducing sperm count, according to research by the University of East Anglia. It only took a 9 to 12 degree F spike over a five-day period to cut sperm count in half. A second spike almost sterilized the insects.19

Costs

From 2002 through 2009, the health-related costs of heat waves was $5.3 billion.20 In 2019, health care costs were $3.8 trillion. That's 18% of the U.S. economy. That's up substantially from 1960 when costs were only $27.2 billion, or just 5% of gross domestic product.21

Heat waves also lower food production. Between 1964 and 2007, drought and heat waves destroyed onetenth of the world's cereal production.22

Forecast

Heat waves will increase in the West, Midwest, and Great Lakes areas of the United States by the mid2020s.23 Montana and Wyoming will have almost 30 days of heat waves in 2030, compared to 10 in 2000.24 Michigan will have 35 and Nebraska will experience almost 40 days of heat waves.2526

The climate impact map shows you how much hotter your state or country will be during the next 10 to 100 years.

By 2028, heat waves and other climate change effects will add $360 billion per year. Much of this is due to health costs.27

By 2030, heat waves will lead to a $2 trillion loss in labor productivity.28 It will kill five times as many people in the U.S.29

By 2100, climate change could cost the U.S. government $112 billion per year.30 Heat waves alone will lower workforce productivity by 1.2 billion hours, costing $170 billion.31

ARTICLE SOURCES

(visit the site for all references).

Heat Waves and Their Effect on the Economy (thebalance.com)

How heat waves can scorch the U.S. economy

Rachel Layne

C B S N E W S

UPDATED ON: JU NE 29, 2021 / 10:00 PM / MONEYWATCH

The triple-digit temperatures roasting the Pacific Northwest under a lingering heat dome are also starting to hurt the region's economy.

In Portland, Oregon, temperatures forced the city's streetcar system to shut down as power cables melted and the heat strained the power grid. Near Seattle, roads cracked along stretches of a major interstate and a public pool shut because air quality was dangerous. Some restaurants closed to protect kitchen staff in a region where fewer than half of homes have air conditioning.

Avista, a utility that serves parts of Washington and Idaho, instituted rolling outages Tuesday as surging electricity demand because of the extreme temperatures strained power grids.

"We know that human-driven climate change is increasing global temperatures, and extreme heat waves disrupt a bunch of the conditions that we think are normal," said Costa Samaras, a Carnegie Mellon associate professor of civil environmental engineering who focuses on energy and climate change.

Last year, some 22 extreme events — from cyclones and hurricanes to drought — cost the U.S. a combined $95 billion, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Since 1980, overall damage from some 285 weather and climate disasters cost at least $1 billion each, or a total of $1.9 trillion, according to NOAA.

"Taxpayers are on the hook for rebuilding all that," Samaras said. "So we all are paying additional taxes to fix infrastructure that gets degraded or destroyed because of extreme weather."